2. Literature Review

The literature on pressure groups emphasizes their dual role in democratic systems: as vehicles for representation and participation, and as sources of asymmetry and potential distortion. Classic works highlight how interest groups influence policy outcomes through lobbying, institutional capture, and resource mobilization, often beyond the control of formal party politics. Comparative studies also show that professional associations and sector-specific federations, such as trade unions or employer organizations, enjoy disproportionate influence relative to less organized groups, reflecting broader theories of elite pluralism. Recent research further stresses the economic dimension of lobbying, where powerful sectors—tourism, manufacturing, and public administration—translate organizational strength into measurable structural outcomes in Gross Value Added (GVA). This body of literature provides the foundation for examining how pressure groups in Greece function not merely as political actors but as key determinants of sectoral weight and economic allocation [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The concept of the pressure group has deep historical roots in the evolution of representative democracy and the emergence of organized civil society. The term first appeared in early twentieth-century political science, notably in the works of Arthur Bentley in 1908 and later David Truman in 1951, who defined interest and pressure groups as essential mechanisms through which citizens articulate demands and influence government decisions. These scholars emphasized that, in modern democracies, collective action is inevitable as individuals with shared interests seek to protect or advance their goals through organized representation. This view marked a shift from earlier liberal theories that saw politics primarily as a contest among individuals, moving instead toward a pluralist interpretation of politics as a competition among organized groups. Historically, the emergence of pressure groups is tied to the industrialization and democratization processes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As societies became more complex and economies more diversified, professional associations, trade unions, and business federations emerged to defend occupational and sectoral interests. In Europe, particularly after World War II, corporatist arrangements institutionalized the interaction between governments, employers, and labor unions, embedding interest representation into policymaking. These developments gradually transformed the nature of political participation, moving it beyond electoral channels toward continuous lobbying and negotiation among organized actors. In the Greek context, the phenomenon of pressure groups evolved alongside the country’s economic modernization and political consolidation after the 1970s. The transition to democracy in 1974 and Greece’s accession to the European Economic Community in 1981 accelerated the formation of organized interests—especially in sectors such as manufacturing, tourism, and public administration. However, unlike Northern European corporatism, Greek lobbying traditionally remained informal, personalized, and weakly regulated, often mediated through party networks and bureaucratic channels rather than formal interest representation systems. This distinct historical trajectory has shaped how pressure groups operate today, influencing both policy formulation and the structural composition of the national economy. From a theoretical perspective, research on pressure groups intersects with the broader literature on pluralism, elite theory, and corporatism. Pluralist theorists such as Dahl and Truman viewed pressure groups as vehicles of participation and checks on governmental power, ensuring that multiple interests coexist within the democratic process. Conversely, elite theorists, following Pareto and Mosca, argued that organized interests often serve to entrench the influence of dominant social or economic elites, thereby reproducing inequality within ostensibly democratic systems. The modern study of pressure groups thus reflects a dual perspective: they are both essential instruments of democratic engagement and potential sources of distortion in policy outcomes. The present research situates pressure groups within the Greek economic structure, exploring their historical formation, institutional behavior, and measurable influence on sectoral performance. By combining theoretical reflection with empirical analysis, it seeks to clarify how historical legacies of informal lobbying and institutional asymmetry continue to shape Greece’s economic organization and policymaking processes [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

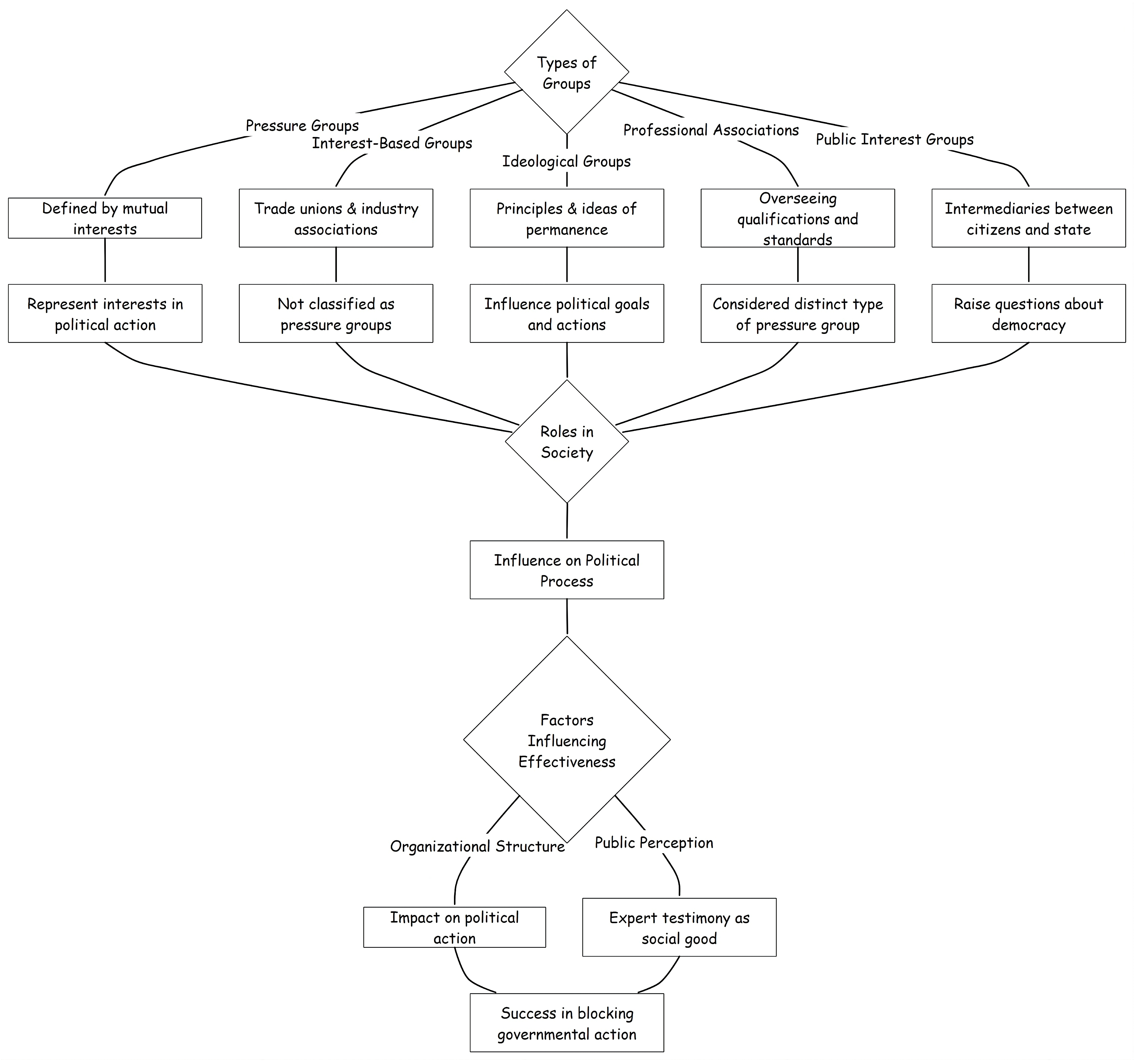

The purpose of this literature review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the various types, functions, and dynamics of pressure groups as discussed in political and economic theory. It begins by distinguishing between interest-based groups, ideological groups, professional associations, and public interest groups, outlining their respective foundations, objectives, and mechanisms of influence. It then explores the characteristics, membership, organization, and funding and resources of these groups to show how internal structure and resource availability affect their political capacity. The research proceeds to examine the strategies and tactics employed by pressure groups to shape policy outcomes, as well as the socio-political context within which they operate, emphasizing variations across national settings and historical periods. Further subsections address the evolution of pressure groups in the 20th century, their dual role in promoting and restricting democracy, and illustrative case studies, including those on immigration in Greece, tourism advocacy, and environmental groups. By integrating these dimensions, the literature review aims to establish a conceptual foundation for understanding how different types of organized interests influence economic structures and policy formulation, with particular relevance to the Greek context analyzed in the subsequent sections [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

2.1. Interest-Based Groups and Ideological Groups

To begin the analysis, it is essential to clarify the conceptual boundaries between interest groups and pressure groups, since the two terms are often used interchangeably in political science and economics. This subsection examines how different scholars distinguish between them, emphasizing that while all pressure groups are interest groups, not all interest groups function as pressure groups. The discussion that follows explains these distinctions, focusing on their proximity to government, representational scope, and the nature of their political engagement within the broader politico-administrative system. Before analyzing their functions, it is necessary to define the concepts of interest groups and pressure groups, as the distinction between them is often blurred in the literature. In general, interest groups refer to organized bodies of individuals or institutions that seek to promote or defend specific interests within the political system. They may include trade unions, professional associations, and employer federation organizations that are formally integrated into policymaking through consultation or corporatist arrangements. By contrast, pressure groups are a narrower subset of interest groups that seek to exert external influence on government decisions without being part of the formal decision-making structure. Their claims are typically oriented toward society-wide concerns or broader public causes rather than sectoral or occupational benefits. Thus, the distinction does not rest on their importance or legitimacy, but on their mode of engagement: interest groups often operate through institutionalized dialogue with the state, whereas pressure groups act from outside the core of government to shape policy through advocacy, lobbying, or public mobilization. This definitional clarification provides the conceptual foundation for the analysis that follows. Trade unions and all sorts of employers and industry associations, as well as other professional associations, exist in the interest group category but are not pressure groups, as the distance to government is usually quite short. Academic associations, lobby groups providing research funding, or groups with a lay-off interest may be viewed as intended interest groups, but not as pressure groups, because the two are not based on a society-wide interest. Therefore, pressure groups in this discussion are nothing but interest groups if understood as organizational groups which are not representatives of labor market parties, or if otherwise denoted as interest groups. All those political organizations which have a special interest or a mixture of interests of a kind which cannot be classified through the above-mentioned categories but still observe the same roles in society’s responses toward political action are included as pressure groups.

The main role of pressure groups within the politico-administrative system is expressed by the term representation. Basically, group representation means that outside the deliberative forum (the parliament), a political actor exists which is allowed to express his or her point of interest to the deliberative forum. The term interest groups is frequently used instead of pressure groups to refer to groups that pursue a particular interest in the political arena. Politically, the term “interest” is closer to the term “wishes” than the term “power”. Focusing on interests in politics does not entail disregarding the principal institutional drivers of political action; rather, it involves examining the underlying wishes and motivations that may be more or less biased depending on their epistemic, ethical, social-ontological, and legal interpretations within the broader political framework. Building upon the distinction between interest groups and pressure groups, it is also important to consider a second major category—ideological groups—whose influence derives not from economic or sectoral interests but from the promotion of enduring ideas and belief systems. Whereas interest-based groups focus on material or organizational advantages, ideological groups seek to shape collective values, political ideologies, and social norms. Their power lies in persuasion and the capacity to mobilize followers around moral or philosophical visions that transcend short-term policy goals [

21,

23,

24,

25,

33,

34].

Lobbying and pressure group activity in Europe has gained renewed attention over the past decade, with growing concern about transparency, accountability, and the distribution of influence within policymaking. Within the European Union, lobbying has become a formalized practice supported by registries and consultation platforms, yet important inequalities persist. Lobbying and pressure group activity in Europe has gained renewed attention over the past decade, with growing concern about transparency, accountability, and the distribution of influence within policymaking. Within the European Union, lobbying has become a formalized practice supported by registries and consultation platforms, yet important inequalities persist. Corporate and professional interests continue to dominate public consultations and shape regulatory agendas, while civil society and smaller organizations struggle to gain comparable access. This persistent imbalance highlights the tension between the ideals of participatory democracy and the realities of concentrated power. In Greece, lobbying remains predominantly informal, often exercised through networks of personal connections, political patronage, and clientelist exchange. Despite European pressures to introduce transparency reforms, institutional progress has been slow and fragmented. The country lacks a comprehensive lobbying registry, and public consultations are often procedural rather than substantive. As a result, influence is exercised in closed settings, with limited public scrutiny or accountability. These characteristics distinguish Greece from more institutionalized lobbying environments elsewhere in Europe, revealing a structural reliance on informal mechanisms of power.

Across the European Union, recent years have witnessed a gradual shift toward transparency and accountability reforms. Some member states have adopted robust lobbying registries and ethics codes, demonstrating measurable gains in public trust and access to information. However, other states continue to experience weak implementation and uneven enforcement. This divergence shows that the formal introduction of transparency rules does not guarantee their effective operation. In contexts where bureaucratic capacity is limited and media oversight remains inconsistent, reforms may exist largely on paper, without fundamentally altering patterns of influence. Greece exemplifies this gap between formal compliance and substantive change. The present study contributes to this debate by linking political influence to quantifiable economic outcomes. Econometric analysis of sectoral data from 2013 to 2023 shows that lobbying capacity is not merely a political variable but also an economic one, shaping growth trajectories across sectors. Sectors with organized and resourceful pressure groups exhibit measurable advantages, while those with weaker representation tend to decline. By combining empirical evidence with institutional interpretation, this paper offers a clearer understanding of how lobbying operates as both a driver of economic transformation and a test of democratic legitimacy within the broader European framework.

2.2. Professional Associations and Public Interest Groups

Following the examination of ideological groups, whose influence is grounded in belief systems and value-driven agendas, the discussion now turns to institutionalized pressure groups that derive their power from formal organization and professional authority. Among these, professional associations represent a distinctive category characterized by their structured governance, specialized knowledge, and recognized social legitimacy. Unlike ideological groups that mobilize around principles, professional associations operate through expertise and institutional credibility, often acting as intermediaries between the state and specific professions. Their influence extends beyond the protection of member interests to shaping legislation, regulation, and public policy in ways that reflect the authority of professional standards. The following discussion explores how such associations, through their institutionalized structure and technical expertise, often exercise greater political leverage than other types of pressure groups. A professional association is a formal organization responsible for overseeing the professional qualifications and standards of members and their practice in their vocations. Widely recognized as custodians of the public standards of a profession, they also possess considerable political and social power. The very different political capabilities of the various professional associations are explained by differences in the length and organization of their professional cultures and business expertise. Professional associations are generally more successful than other pressure groups in blocking governmental action. A theory of the knowledge, esteem, and identity advantages of professional associations over otherwise equally placed pressure groups is postulated. The theory is to be applied to the example cases of the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the American Institute of Accountants.

The influence of professional associations on public policy serves as an example of the influence of formally structured interest groups in modern representative democracies. Professional associations serve as avenues through which the professional knowledge and knowledge-based esteem (which a sizeable percentage of the public generally believes to be equivalent to the quality of their work) of the professions can be communicated to the political process. In doing so, they provide politicians with opportunities to appear knowledgeable and informed regarding those issues and so to develop their own professionally associated identities. Their expert testimony is most often a social good that enhances political efficiency and accountability, but they are also a source of public harm in that they promote public policies calculated to maximize profits regardless of any adverse repercussions for the public they are meant to benefit. As a form of structured interest group, professional associations are generally more powerful than other forms; acting under equivalent conditions, politicians incur greater costs and difficulties in taking action against professional associations than against other pressure groups.

The key characteristics of professional associations can be summarized as follows. First, they possess a formal and institutionalized structure, with organized governance bodies that regulate membership, qualifications, and standards of practice. Second, they rely on specialized knowledge and technical expertise, which grants them professional authority and public legitimacy in shaping policies related to their fields. Third, they act as custodians of public standards, safeguarding the quality and ethics of their profession while also serving as intermediaries between practitioners and the state. Fourth, professional associations derive influence from knowledge-based esteem and identity, as their members are often viewed as trusted experts by both the public and policymakers. Fifth, they enjoy substantial political leverage, typically exceeding that of other pressure groups, due to their ability to combine expertise with organizational discipline and long-established professional cultures. Finally, despite their contribution to political accountability and efficiency, they may also pose risks of regulatory capture, promoting policies that favor professional or financial interests over public welfare. These features collectively distinguish professional associations from other types of pressure groups and explain their persistent influence within modern representative democracies. The basic characteristics of what are referred to as professional associations are outlined, and those characteristics are taken as the requisite definition of the term. The argument for their consideration as a distinct type of pressure group is advanced. The argument for their relative political capacity is made in general terms and then applied to the American professional associations of the medicine, law, and accounting professions as example cases.

Building upon the discussion of professional associations, which exert influence through institutional authority and specialized expertise, attention now shifts to public interest groups—organizations that claim to represent collective or societal interests rather than those of a specific profession or economic sector. Unlike professional associations that rely on technical legitimacy, public interest groups derive their power from moral authority, civic mobilization, and the ability to articulate issues of broad public concern, such as environmental protection, social justice, or consumer rights. Their emergence reflects a shift from corporatist or elite-based representation toward more participatory and pluralistic forms of advocacy. The following discussion examines how these groups function as intermediaries between citizens and the state, exploring their organizational challenges, sources of legitimacy, and evolving influence within modern democracies and transnational governance structures such as the European Union. Public interest groups, or groups that claim to represent broad societal interests and thus function as intermediaries between citizens and the centralized state, are of fundamental importance to the basic functioning of democratic pluralism. On the one hand, these groups provide the representation otherwise absent from the agenda-setting functions of policy elites. They are at least initially outside the core of civil society. As a group sector, these associations thus raise fundamental questions about democracy. What broad public interests are represented among ideas and interests present in political discourse? Under what conditions, structure, and processes do public interest movements/campaigns form in modern democracies? Although extensively studied in the literature, this is still an important issue. In the case of interest groups, what are the similarities and differences in the roles of business, trade, and public interest groups across different democratic contexts? How do different collective action structures condition access and influence paths? What are the effects of the changing party–state–public interest groups relationships in different national contexts? How do public interest groups with transnational claims emerge, mobilize, and interact with the EU? How can public interest groups deal with the limits of deductible donations in terms of their funding strategies, and how can they influence the debates on regulation within the EU?

Public interest groups are likely to exist in modest numbers for long periods of time and often in countries with active trade associations and business groups. In recent years, however, the relative numbers and influence of these organizations have increased dramatically, particularly in the United States, the battered but largely intact bastion of pluralism. This adopts a political opportunity approach to address some critical theoretical and empirical questions involving these groups. Public interest groups have emerged in increasing numbers and with considerable political effectiveness since the late 1950s. Their creation and widespread success mark the most dramatic change in the last quarter-century in the composition and behavior of organized interests. Other sectors of organized interests have also flowered, but few as abruptly or noticeably as the public interest.

After examining the specific categories of pressure groups, interest-based, ideological, professional, and public interest, it is necessary to place these diverse forms within a broader liberal-democratic framework. The following discussion moves beyond typologies to consider how pressure groups, in general, interact with political institutions and society at large. It highlights the continuum that exists between narrowly focused organizations pursuing specific policy goals and broader movements seeking ideological or constitutional change. By situating pressure groups along this spectrum, the analysis underscores their dual role as both stabilizing and disruptive forces within democracy—capable of fostering participation and representation, yet also of generating asymmetries of influence and social fragmentation. Throughout history, society has had to come to terms with the roles that groups play in the social and political spheres in which they exist. It is hoped that the following sections will clarify how pressure groups or interest groups operate within a liberal democratic framework. At one end of the spectrum are groups that are concerned with a particular issue and deploy carefully thought-out campaign resources to alter the political environment. At the other end of the spectrum are groups driven by clear ideological considerations that seek to alter the political and constitutional fabric of the state. In Britain and other states, there is some evidence that what have been described as ‘new’ or ‘narrow’ pressure groups have developed in response to both regime change and events. Some of these are clearly subversive and radical in tone and content.

From the definition of pressure groups, interest aggregation and synthesis can only commence after the broad wishes of the electorate have been artificially confined within narrow limits. That is, pressure groups can be said to aggregate interests only if the definition of ‘interests’ is restricted to urgent parochial demands. But the process of aggregation and synthesis, being more subtle, is easily overlooked. It is usually assumed that interest aggregation means arriving at a widely acceptable compromise. However, it is a well-known truth that mass social conflicts seldom offer that opportunity. Broad groups or sub-systems form in political systems more in response to contrary trends than to some concerted attempt at consistency. Despite their size and weight, they are often comparatively loose formations. The relations connecting their units are seldom explicitly worked out.

2.3. Membership and Organization

Having established the broader democratic role of pressure groups, it is equally important to understand who participates in them and how they are organized. The following discussion turns from institutional and theoretical perspectives to the social foundations of group participation. It explores the types of citizens who choose to join pressure groups, the motivations underlying their involvement, and the organizational forms these groups adopt—from informal community initiatives to highly structured associations with national or transnational reach. By examining patterns of membership, engagement, and internal cohesion, this section highlights how the strength and persistence of pressure groups depend not only on resources and ideology but also on the depth of civic participation and the networks of social capital that sustain them. Which citizens choose to belong to groups, and what kinds of groups are they? Many are ordinary citizens who join voluntarily. They join or affiliate with innumerable and diverse groups. They are typically in a few wage-earning organizations and in a few more, rooting for a favorite team or singing in a choir, group sympathy adding a variety of tones to their choices. Beyond the basics, they range widely geographically—from towns to states or countries—and organizationally, from small, informal lists of demands to more formal structures with names and significant histories. What do ordinary men and women know about these organizations or group memberships? They have some knowledge and experience, but because there are so many of them, most would not know enough about even one to speak intelligently.

Whether adversity or purpose puts pressure on citizens and groups to be politically engaged is a very complicated dependent variable. For ongoing issues like collective bargaining, the setting within which polity groups operate shifts almost constantly. There are arrests, court rulings, meetings, compromises, and more votes. At each stage, the issue is revisited, often with classes and behaviors being recombined like loose Lego blocks. On the other hand, social accounting interests would argue that it is how much and how effectively the group presents its pressure. Consider what happens simply with government funding, where representatives sit on advisory boards together, presumably affecting harmony among the academy, policy, paid advisers, and clients. In principle, there is no effect on how effectively an organization acts within the polity. In practice, the group with deepest roots in the polity and thickest skin would seem to do best. Whose deficit narrows quicker is an empirical question for research, but a critique of social capital that does not pick a measure is no counter to difficult but reasonable counterfactuals that weigh or interaction degrees in a network model.

2.4. Funding and Resources Based on Strategies and Tactics

While earlier studies have examined political financing and lobbying practices in countries such as India or the United Kingdom, the present research focuses specifically on the European and Greek context, where lobbying operates within the institutional frameworks of the European Union and national corporatist traditions. In Greece, lobbying remains largely informal and personalized, contrasting with the more structured transparency regimes of Northern Europe. Therefore, discussions of funding practices and local activism abroad are omitted here, as they do not directly inform the Greek case. Instead, the analysis concentrates on how EU transparency initiatives, such as the European Transparency Register and related national reforms, interact with Greece’s evolving mechanisms of interest representation.

Beyond questions of membership and civic participation, the financial dimension of pressure group activity constitutes a critical determinant of their influence and sustainability. The following discussion addresses funding and resources, examining how financial capacity shapes the operational effectiveness, visibility, and political leverage of both parties and organized groups. Adequate financing allows pressure groups to sustain campaigns, support lobbying activities, and maintain institutional continuity; yet excessive or opaque funding can also undermine public trust and distort democratic processes. By exploring examples such as political financing in India, this section highlights how disparities in financial resources contribute to unequal access to decision-making, raising broader concerns about transparency, accountability, and fairness in democratic representation. A major political party needs substantial funds to run its day-to-day operations and during elections. Though political behavior has become so popular, such spectacular achievements of financial capitalistic accumulation and spending create a fearful wonder. Whether such a process is normal and legal or something abnormal seems to be a question of great significance. However, too much money, huge donations by somebody, and contributions from some dubious source invite suspicion, as it is a very serious matter and involves trust in democracy. Political parties in India, both at the center and the states, have been doing their job with a paltry amount of money. This is due to three reasons. First, the government has not enabled them to grow economically, politically, or ideologically. The largest multi-party nation and the second largest democracy has little political finance. Next, the poor level of grants is hardly believed to be the primary cause of the political corruption, as they receive donations from crores outside the model code of conduct. With the growing competition among pressure groups for governmental and media attention, groups are adopting a wider range of strategies and tactics. This includes mass demonstrations, minority militancy, infiltration of parliamentary committees, and extensive media work. The concern here is with national or transnational pressure groups. Local pressure groups have always engaged in petty tactics, and there is no need to consider local pressure groups here [

21,

35,

36,

37,

38].

After considering the financial foundations that sustain pressure group activity, it is equally essential to examine the strategies and tactics through which these groups seek to exert influence. Financial capacity alone does not determine effectiveness; it must be coupled with well-designed methods of communication, mobilization, and persuasion. The following discussion explores how pressure groups adapt their tactics to an increasingly competitive political and media environment, employing tools that range from traditional lobbying and parliamentary engagement to public demonstrations, civil disobedience, and media campaigns. By analyzing these evolving strategies, the section highlights the interplay between resource availability, public visibility, and political impact—showing how groups translate material power and organizational strength into concrete influence over policy and societal change. A standard repertoire of tactics has been established. A successful tactic does not merely generate media coverage or stir public interest and debate, but directly impacts the target. The Hungerford Road case refers to a local environmental campaign in the London Borough of Camden during the late 1960s, when residents and civic groups opposed a proposed road expansion plan that threatened to remove a line of mature trees and disrupt the neighborhood’s character. The proposal was part of a broader municipal effort to alleviate traffic congestion by widening key routes through residential areas, an approach widely contested at the time for prioritizing vehicle flow over community and environmental interests. Local citizens organized meetings, petitioned the Council, and collaborated with environmental advocates to challenge the scheme. Their campaign ultimately succeeded in persuading the authorities to abandon the plan, illustrating how grassroots mobilization and sustained public dialog can influence urban policy decisions. The case serves as an example of how localized pressure groups—though small in scale—can effectively use media attention and public participation to alter municipal policy outcomes, highlighting the practical application of pressure-group dynamics within a democratic context. When Hungerford Road, one of the road schemes proposed by Camden Borough Council, was declared worthy of action, the local press carried substantial coverage, culminating in earth-moving machines removing trees along the road. Council attempts to improve traffic flow through the area were made in 1967 and rejected after a successful local campaign based on local discussions [

34,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. It was concluded that the Council’s efforts were an overreaction to the problem and that resisting a bus stop would be enough. In view of the last six years’ experience, the proposal to cut down trees in an effort to calm the traffic should be abandoned. Instead, a range of measures should be adopted to reduce traffic. Though none of these points had been raised with sufficient emphasis in the group discussions, the Council approval was forthcoming, and the situation was monitored for a year.

By targeting a business involved in unsafe practices, the social legitimacy of the business is endangered. Forces of law and order are sent in, such as police or school children, who are frightened off from the area. By targeting those youngsters, the ‘wet’ is discredited, and then civil disobedience on a small scale is debated. Nonviolent direct action, often in the form of roadblocks, is adopted as a form of contempt for the court. Civil disobedience activities are accompanied by the evocation of Science and Justice as shields against police battering. Direct action is regarded as justified and necessary; it is ‘an old and honorable tradition in the West’, which is used as social actors improve practices for a better quality of life [

39,

47,

48,

49].

2.5. The Socio-Political Context and Pressure Groups

Following the concept of the strategies and tactics employed by pressure groups to achieve their objectives, it becomes necessary to situate these actions within their broader socio-political context. Strategies do not emerge in a vacuum; rather, they are shaped by the institutional environment, historical conditions, and political culture in which groups operate. The following section examines how the study of pressure groups can be approached from both extensive and intensive perspectives—either by classifying different types of organizations within a system or by analyzing in depth the pressures exerted by specific groups on policymaking. By emphasizing the importance of political context and institutional variation, this discussion highlights that the nature and influence of pressure groups are not universal but contingent upon the structures, norms, and evolution of the societies in which they exist. Most studies of pressure groups focus on the particular characteristics of pressure-group politics. Such approaches can be either extensive or intensive. An extensive approach will attempt to systematically catalog the types of groups existing in the system. Efforts will need to be made to develop taxonomies of groups, considering, inter alia, the external environment. By contrast, an intensive approach will need to examine in detail the pressures exerted by a few groups on policy issues. It may examine the range of tactics employed by these groups, their search for allies, the channels through which they operate, or the interaction between these groups and decision-makers. Both approaches cohere around the proposition that pressure group politics is a form of politics in its own right.

The difficulty with such approaches is that they establish an artificial boundary between pressure group politics and politics as such. The characteristics of pressure groups will depend heavily on the context in which they interact. The way politics is organized, and the range of pressures, will differ from one country to another, from one period of time to another, and in diverse theories of politicization. In this respect, such an approach makes it very difficult to generalize to other contexts. It is also evident that what is understood as a pressure group cannot be taken as universal. There are societies, such as the Sultans of Brunei, in which the concept has little purchase. There are conceivable socio-political contexts that go beyond the normal comprehension of all but a few political theorists. Thus, avoidance of these theoretical abstractions and backdrop theorizing means that the analysis becomes practically political. This should not necessarily lead to radical ditching of theoretical perspectives, but rather to more modest intentions. Approaches that have been developed and tested—utopian as one of them may be—need not be discarded when undertaking political analyses of a particular country. They can simply be calibrated based on both strengths and weaknesses [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. The continuing evolution of alternative approaches, by contrast, provides an internal hedge against stagnation. In considering the political environment within which pressure groups operate, the focus will be on two aspects: the evolved socio-political context on the one hand and analytic paradigms on the other.

2.6. Pressure Groups in the 20th Century Promoting Democracy

Having situated pressure group activity within its broader socio-political environment, it is now important to consider how these groups function within democratic systems and how their influence shapes decision-making processes. The following discussion examines the dual character of pressure groups in democracy: on the one hand, they serve as vital mechanisms of representation and participation, enabling citizens to articulate collective interests and hold governments accountable; on the other, they may reinforce inequalities of access and power, particularly when dominated by elite interests. By contrasting pluralist and elite theories of democracy, this section highlights how pressure groups can both strengthen democratic engagement and, paradoxically, contribute to its distortion when their actions primarily safeguard the privileges of powerful actors rather than the broader public good. A pressure group is a group of individuals that is organized and equipped to exert influence over those responsible for making decisions about matters of interest to the group. Pressure groups play an essential role in a democratic society by providing a check on the powers of elected officials and other decision-makers, allowing groups of people to come together to communicate their collective views and push for change, and providing a mechanism through which citizens can meaningfully participate in government. Despite having a positive image in principle, in practice, pressure groups may undermine people’s trust in democracy. In particular, interest groups may have conflicting motives that prevent them from being unambiguously beneficial to democracy.

An interest group is defined as any organization of people who share common objectives and actively seek to influence public policy. Interest groups can be grouped into four broad categories: (1) economic, representing business, trade, labor, and agriculture; (2) public interest, advocating for issues like the environment, health and safety, and social equity; (3) government, representing state, local, and federal initiatives; and (4) ideological, promoting broader societal changes. Interest groups can exert influence over policymakers (I) directly, through lobbying and contributions to campaigns, or (II) indirectly, through grassroots mobilization tactics that build public support for, or opposition to, a given policy. The current involvement of interest groups and lobbying in policymaking is the subject of extensive research and debate.

The relative strength of various elite groups is important for understanding democratic decision-making. In this context, the elite-group theory posits that key decisions are made by small groups of elites operating behind a facade of democracy, while much of the political process is devoted to manufacturing consent among the masses. From this perspective, pressure groups may be seen as instruments used by elites to protect their interests in the face of mass opposition and demands for equity and social justice. As such, democracy may quite well represent the interests of elite groups holding opposing views, who will use their differing pressure groups to achieve conflicting, yet elite-preserving, ends.

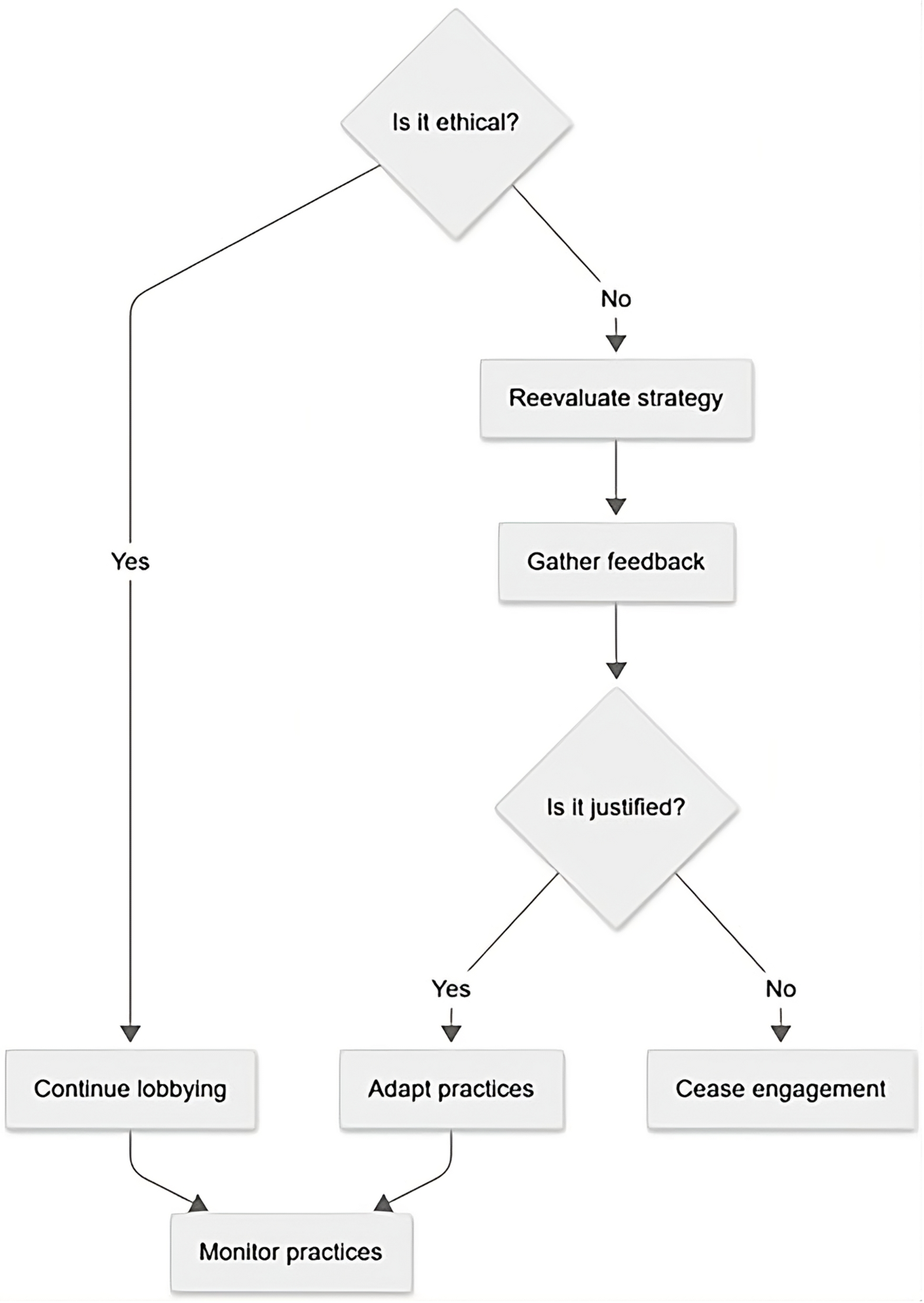

Building on the preceding discussion of how pressure groups operate within democratic systems—sometimes reinforcing participation and at other times reflecting elite dominance—it is also crucial to examine their influence in the global promotion of democracy. The following discussion extends the analysis beyond national boundaries to explore how pressure groups, international organizations, and transnational advocacy networks contribute to democratization efforts worldwide. By shaping political discourse, monitoring elections, and supporting governance reforms, these groups act as agents of political diffusion and institutional learning. However, their impact is not uniformly positive: while they may strengthen democratic norms and civic engagement, they can also reproduce asymmetries of power between states and impose externally defined models of democracy. This section, therefore, situates pressure groups within the broader landscape of global democratic transformation, highlighting both their contributions and inherent contradictions. The results of this study highlight the structural imbalance of lobbying power in Greece and its implications for transparency and democratic accountability [

47,

48,

49,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The analysis shows that sectors represented by organized and resourceful associations—such as SEV in manufacturing and SETE in tourism—perform better and exhibit greater policy adaptability than those dominated by public or fragmented interests, such as ADEDY in the state sector. This pattern suggests that the organization and coherence of lobbying networks contribute to sectoral resilience, even if the econometric results are descriptive rather than causal.

The Greek case reveals a persistent institutional paradox: lobbying operates within a largely informal system that lacks clear regulatory boundaries. Although Greece participates in European Union frameworks promoting open consultation and transparency, its domestic implementation remains partial. Most lobbying occurs through personal networks, party affiliations, and ad hoc negotiations, which favor established economic elites and disadvantage smaller civic or professional groups. This asymmetry explains why lobbying outcomes tend to reinforce existing hierarchies rather than diversify representation. These findings contribute to a broader understanding of how weakly institutionalized lobbying affects both economic performance and democratic legitimacy. The lack of formal oversight allows interest representation to function as a closed system, accessible mainly to groups with political or financial leverage. Consequently, sectors with established advocacy structures benefit from greater policy continuity and access to state decision-making, while others remain marginalized. This dynamic underscores the need to view lobbying not only as a matter of political ethics but as a determinant of economic structure and distributional outcomes. Unlike generalized global protest movements or digital mobilization campaigns, lobbying in Greece operates within a small and interconnected policy community. Its impact lies not in mass mobilization but in the sustained negotiation between organized groups and government agencies. Understanding these relationships helps explain why the country’s post-crisis restructuring produced uneven results across sectors. The findings illustrate that lobbying strength correlates with policy influence and sectoral adaptability, while a weak organization translates into limited access to reform agendas. The Greek case indicates that lobbying is both an economic and institutional phenomenon. It shapes resource allocation and policy priorities through selective access to decision-making. By linking sectoral economic data with qualitative evidence from major associations, this study provides a grounded interpretation of how influence operates in practice. The results highlight the urgent need for a more transparent, pluralistic, and accountable lobbying framework to align interest representation with democratic principles and equitable economic development [

60,

61,

62].

After considering how pressure groups can act as agents for the expansion and promotion of democracy across national and global contexts, it is equally important to address their potential to constrain or degrade democratic deliberation. The following discussion examines the paradox that, while pressure groups may enhance participation and representation, they can also fragment public discourse and undermine the equality of political deliberation. As these groups become more influential within electoral systems, their pursuit of specific agendas may prioritize particular interests over collective well-being, thereby challenging the principles of inclusivity and fairness central to democratic governance. This section explores how such dynamics can transform pressure group activity from a vehicle of empowerment into a mechanism that restricts open dialog and limits genuine political freedom. When judging a democratic system, we presume that it is a good one unless there is something specific that degrades it. Ensuring that deliberation within political structures proceeds well is seen as invaluable. This leads to consideration of whether pressure groups (groups formed that seek to take political action to achieve a common goal), as they have become a more prominent part of electoral politics, have degraded the quality of political deliberation. Political deliberation is taken to refer only to discussions of matters of actual political significance, which excludes discussions that only concern how to organize political deliberation. So long as those making decisions about political matters themselves live within the system of political relationships to which their decisions pertain, they are deemed to be ‘internal’ to that system. Many claim that contemporary democracies are systems of government that are structured around majority decision-making. It is therefore presumed that these systems treat all citizens equally, as they weigh citizens’ votes equally. Those who cast votes in these systems expect that the more votes a particular law obtains, the more likely it is that that law will be enacted. Additionally, it is reasoned that precisely because citizens have an equal say in whether or not a particular law is enacted, the more votes it obtains, the more citizens desire that law. Nevertheless, it is noticed that modern democracies often contain groups or interests that campaign for the restriction, reform, or outright abolition of democracy. They deny freedom to a segment of the citizenry on the grounds that doing so serves the freedom of all citizens.

Yet if desiring agents are equal, a decision procedure that equally values the desires of those agents would yield decisions that, whilst offering freedom to one citizen, would not deny it to another. Thus, with the possibility of one citizen being the object of a decision that another desired, such a system of government would be unable to confer freedom on either citizen. So the conditions under which a citizen’s desire is realized would be consistent with other agents not desiring that realization, which indicates that, in some pertinent way, such conditions would license a lack of freedom for those citizens.

2.7. Case Studies of Pressure Groups

Having discussed the dual potential of pressure groups to both enhance and restrict democratic processes, it is instructive to turn to practical case studies that demonstrate how such dynamics unfold in specific policy domains. Environmental governance offers a particularly revealing context, as it combines scientific, economic, and political dimensions under intense public scrutiny. The following example of the European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS) illustrates how coordinated action among governments, industry stakeholders, and environmental organizations can transform lobbying efforts into concrete policy mechanisms. This case highlights the capacity of pressure groups to influence regulatory design—balancing environmental responsibility with economic interests—and showcases how collective advocacy can reshape national and transnational approaches to climate policy. The European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is, without doubt, the most important step in attempting to tackle climate change. The scheme is the most important piece of legislation for controlling carbon emissions in the UK, with tight limits set for the sectors covered by the scheme (i.e., energy generation, oil refining, and aviation). The EU ETS is intended to put a price on carbon emissions and encourage industry to invest in low-carbon technologies and greener processes in order to minimize their emissions. If companies invest with the intent of reducing emissions, they are permitted to sell their spare allocations of emissions; the prospect of profit will ensure investment in greener industries.

The UK is also a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, which is a 1997 international agreement, which commits developed countries to limit their population’s carbon emissions. It was against the backdrop of one of the hottest decades of summers in recorded history, and public opinion had shifted towards greater awareness of global warming. The Labor government had to demonstrate that the UK was doing its part, but also ensure this was achieved without damaging the British economy. The UK ETS was one of the first pressure groups to launch since New Labor swept to power in 1997. Blair was determined to establish stakeholder capitalism with a tripartite agreement amongst government, employers, and unions. Environmental issues would be included within this framework. Britain’s heavy reliance on coal meant that local government alone could not tackle air pollution in London and elsewhere within the Tory government’s jurisdiction. The government initially rejected these initiatives out of hand. However, in the face of ever-increasing pollution from coal power stations and as a means of drawing environmental groups away from the streets and into boardrooms, the government capitulated to demand for a UK Emission Trading Scheme in April 2002.

Following the examination of environmental policy as a field where pressure groups have significantly shaped transnational regulatory frameworks, it is equally valuable to explore how such dynamics manifest in social and cultural contexts. The case of immigration in Greece offers a compelling example of how pressure groups, public discourse, and media representations interact to influence national identity and policy formation. Unlike environmental advocacy, which often revolves around measurable outcomes, immigration debates are rooted in perceptions, cultural narratives, and societal anxieties. The following discussion examines how organized interests, political actors, and media institutions have framed immigration and “Otherness” in Greece, shaping both public opinion and governmental responses in a period marked by rapid demographic transformation and evolving concepts of social inclusion. Greece is one of the European countries that experienced a dramatic increase in immigration. At the beginning of the 1990s, the influx was a sudden change in the homogeneity of society, to a multicultural environment that was foreign to the collective consciousness of people, while the identity of modern Greeks was built from the very conception of the national self was based on the principles of ethnocentrism and insertions of homogeneity, referring to both the state and the society. In these historical circumstances, there is now a vivid presence of non-Greeks in the public life of the cities, from observations in the streets and every public space; moreover, debates on the issue of the presence of foreigners are increasingly emphasized in the dominant political agenda via the mass media [

47,

50,

51,

52,

58,

59,

63,

64,

65,

66]. The literature review is divided into two main topics. The first constitutes theoretical issues, including the character of the representations, the connections of the representations, the political and social contexts, and the mediating role of the mass media. The second relates to the dominant representations about migrants and immigration in the case of Greece, with emphasis on the prevailing contexts, the named process of Otherness and its contemporary transformation, and the ways migrants’ and newcomers’ representational processes are being imagined. Greece is presented as an experience of a new and large-scale immigrant flow country that has become ethnoreligious and culturally pluralistic at the city level and ethnoculturally at the national level. A review of published studies indicates that there are different standpoints, various aspects tackled in the case of representation by mass media, printed or audiovisual, as well as by different technologies that are not relatively widespread internationally [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58].

After exploring how immigration and cultural representation shape public discourse and political responses in Greece, attention now turns to another major societal and economic force—tourism advocacy—as a distinctive form of pressure group activity. The tourism sector offers a valuable example of how organized interests can directly influence national economic priorities, public policy, and cultural exchange. Unlike immigration debates, which often center on social integration and identity, tourism advocacy operates through economic argumentation and developmental narratives, emphasizing employment creation, global connectivity, and cross-cultural understanding. The following discussion examines how tourism advocacy functions as both an economic pressure group and a vehicle of soft power, demonstrating how collective lobbying efforts in this field can simultaneously advance growth and raise ethical concerns about sustainability, equity, and the balance between public and private interests. Tourism advocacy as a pressure group in the modern world is more relevant now than ever. The tourism sector has shown growth rates significantly above average. Various regions and cities are striving to enrich their tourism product. The tourism sector is fighting for the right purposes. It is responsible for a significant contribution to global GDP, employment creation, business creation, increased cultural diversity, poverty reduction in underdeveloped countries, raising political and cultural esteem, and international understanding among people. Modern democracies are based on the freedom of citizens to pursue their objectives. To promote diverse aims, various pressure groups exist. These groupings collect funding and lobby for actions they consider to be of common and mutual benefit. Governments infringe on the freedoms of these interest groups even in the case of activities inconceivable by hyper democratic countries. As one of the better recognized interest groupings, tourism advocacy, undoubtedly affected by the possibilities presented by government laws, is likely seriously affected by government presentation as well [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

The tourism industry as a societal economic sector is a relatively new school of thought, both in rationalization in public, professional terms, as well as in academic explanation and argumentation. The assumed collective wish is not a strong, precise pattern of thoughts which is being worked out thoroughly. By means of an impressionistic approach, an intuitive presentation of tourism advocacy is made. In particular, fractures in the input, intermediary actions, consequences, degree of success, insights, and generalizations are dealt with. To conclude, in the vanishing of solitary thoughts and actions, something new is likely arising, other than disgusted hoaxes. As indicated above, sheer presentation cannot do well without knowing: without sound academic exegesis, advocacy efforts will remain strategic and tactical black boxes to be missed and considered risky ventures. As everybody should know, the present times are about discerning themselves, and the social and economic spheres may change drastically, even overnight, in ways less friendly to democratic values and human rights. On the contrary, efforts to group, argue, defend knowledge, figure out mutual benefits, and lobby for what likely should be, should be reinforced: a chastening but presenting paradox [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79].

In an age without heroes and powers seeking blatantly objectifying grounds of belief, philosophy, and judgment, nobody should abstain from ethical debate or from trial and error—bouncing, learning, and testing what remains arguable. Tension is to pick up the semi-colons of unfinished thoughts and coalesce to search for insight and instant action—together. Knowledge filtering in tourism advocacy is about transformations in economic being, living, meeting, learning, acting, and thinking that have ambivalent impacts on wealth division, cultural variety, international standing, and mutual respect among individuals and communities, and therefore should be profoundly denied [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85].

Building upon the discussion of tourism advocacy as an economic and cultural pressure group, it is equally important to examine the contrasting yet closely related domain of environmental groups, which often operate at the intersection of public interest and policy reform. Whereas tourism advocacy tends to emphasize growth, development, and international cooperation, environmental organizations prioritize sustainability, conservation, and ecological balance. The following discussion explores the organizational diversity and hierarchical structure of environmental groups—from national and regional to local levels—highlighting how their fiscal capacity, expertise, and access to policymakers shape their influence on environmental legislation. By comparing their lobbying practices with those of other economic and social interest groups, this section illustrates how environmental advocacy has evolved into a complex and powerful form of collective action that both complements and challenges other sectors of pressure group activity. The term environmental groups is extensively construed throughout the literature, but a commonplace definition comprises all organizations engaged in public education or legislative lobbying activities germane to environmental protection. Public interest organizations that lobby in the energy field are also included in this definition. Environmental groups consist of a wide array of organizations significantly diverse in terms of fiscal and policy resources and goals. Environmental groups that have engaged substantially in lobbying and public education efforts might be divided into three categories: national organizations, regional organizations, and local organizations. The national organizations are non-profit organizations headquartered in Washington, D.C. or other major cities with local affiliates and field offices in cities and smaller localities. The defining characteristic of the national organizations is a very substantial organizational capacity, almost exclusively in the level of fiscal and expert resources [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. They maintain an extensive lobbying staff in Washington, D.C., and a modest number of local lobbyists in several cities. They engage in lobbying efforts that are characteristically high-profile on scientific questions, with considerable budgets devoted to them. These organizations are the key players in wild river prohibitions, the preservation of the National Park System and Wilderness Areas, nuclear reactor site selection, and pesticide regulation [

66,

93,

94].

The lobbyists for national environmental organizations target higher-level government officials rather than their local counterparts. National organizations have a unique role in controlling the media through which environmental and energy issues are investigated and debated. Environmental groups of this organizational type are also most frequently directly responsible for the formation of coalitions to achieve statutory goals. However, among regional organizations, public education efforts dwarf lobbying efforts related to legislation. Unlike national organizations, regional organizations do not at present have expert assistance to help organize lobbying coalitions. Efforts to lobby Congress directly are rare in contrast to frequent lobbying of state environmental and energy authorities, local governments, and political figures. The organizations served by lobbyists in the largest metropolitan areas actively engaged in lobbying against and in favor of proposed legislation. These organizations, somewhat remarkably, consist of a number of professional societies and trade unions having diverse local goals. Lobbying threats, however, have so far not materialized into concerted campaign efforts. Organizations not involved in lobbying efforts are as diverse as those that do engage in lobbying. A common factor among organizations pressed for resources is the belief that lobbying is a low-payoff, limited-use activity for achieving stated policy goals. To maintain analytical focus, the analysis that follows concentrates on the interaction between lobbying structures and sectoral economic performance in Greece and the wider EU context. Comparative historical digressions and case-specific narratives have been minimized to emphasize conceptual clarity and empirical relevance [

63,

64,

65,

95,

96].

4. Results

The quantitative analysis draws on official data published by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) and Eurostat. Sectoral shares of Gross Value Added (GVA) were extracted from the national accounts and the Structural Business Statistics datasets, covering the period 2013–2023 [

99]. Data were harmonized to ensure temporal and cross-sectoral consistency, with minor adjustments for rounding and definitional discrepancies. All econometric computations were conducted using the R statistical environment (version 4.3), employing packages such as lmtest and sandwich for OLS estimation with Newey–West robust errors, while Python (version 3.11) was used for data preprocessing, visualization, and validation through pandas and stats models. This dual implementation enhances reproducibility and cross-verification of the results.

The quantitative analysis relies exclusively on official sectoral accounts provided by Eurostat and the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) (Structural Business Statistics, annual series for 2013–2023). All data were retrieved in March 2024 from the Eurostat online database and the ELSTAT data portal. Each series was cross-checked for definitional consistency and harmonized using the ESA 2010 classification of activities (A10 breakdown). Minor adjustments were applied to correct rounding discrepancies and align missing values by linear interpolation. The analysis employs a log–ratio linear trend model to describe how the relative shares of key sectors evolved during 2013–2023. While this model provides quantitative evidence of sectoral shifts, it does not incorporate direct measures of lobbying intensity, as systematic statistics on lobbying activity, financial expenditures, or membership size are not available in Greece. Instead, institutional proxies—such as the documented presence and influence of SEV, SETE, and ADEDY—are used qualitatively to interpret the patterns observed in the data. Accordingly, the econometric component should be viewed as descriptive and exploratory, illustrating correlations between sectoral evolution and institutional strength rather than inferring strict causality:

In

Table 1, in line with official national accounts, the analysis groups closely related activities—such as public administration, defense, education, and health—into a single composite category representing the state and social services sector. This aggregation follows the Eurostat standard but is acknowledged as a limitation, as it may obscure variations within sub-components. Where data availability permitted, supplementary checks across disaggregated subsectors were conducted to suggest that the overall trends remained consistent with the aggregate results. The model aims to explain variations in the share of services in Gross Value Added (GVA) in Greece based on the composition of key economic sectors.

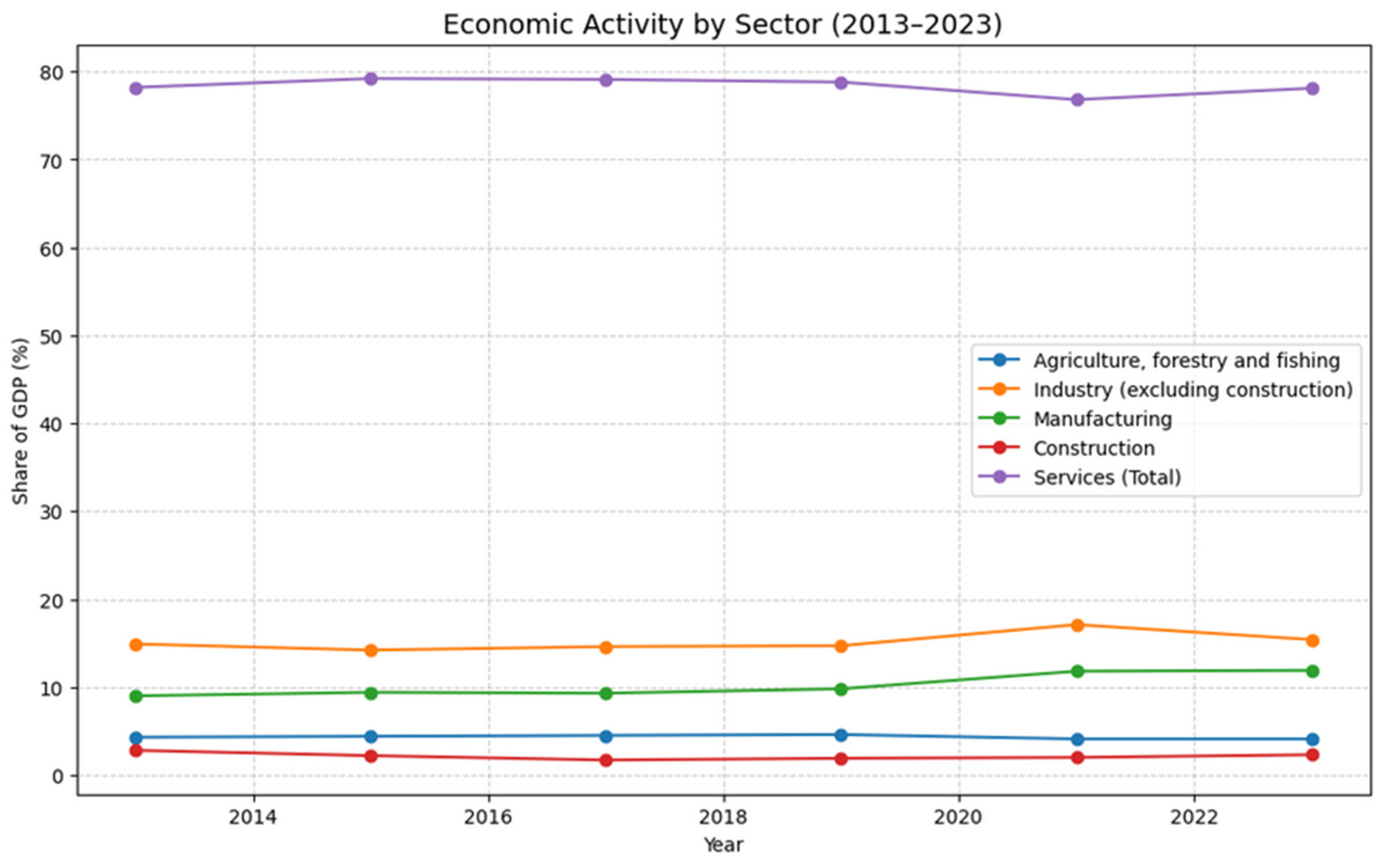

Figure 2 illustrates the annual shares of Gross Value Added (GVA) by major sectors of economic activity—Agriculture, Industry (excluding construction), Manufacturing, Construction, and Services—expressed as percentages of total GVA. The data cover the period 2013–2023 and originate from the ELSTAT/Eurostat National Accounts (A64 classification). The visualization presents sectoral trajectories using line plots with circular markers, where the vertical axis denotes each sector’s share of GVA and the horizontal axis represents calendar years. All values are measured as percentages of total GVA. GVA = Gross Value Added.

This chart illustrates the evolution of the main sectors of economic activity as a share of GDP between 2013 and 2023. The services sector consistently dominates the economy, maintaining a share close to 78–79% throughout the period, highlighting its structural importance. Industry (excluding construction) shows moderate stability with a slight increase until 2021, before a small decline by 2023 [

100,

101]. Manufacturing stands out as a growing component, rising from around 9% in 2013 to nearly 12% in 2023, marking the most significant positive change. Agriculture and construction remain relatively small contributors, with agriculture hovering around 4% and construction showing a gradual decline before a slight recovery after 2019. Overall, the data emphasize the resilience of services, the gradual strengthening of manufacturing, and the relatively modest roles of agriculture and construction in the economic structure.

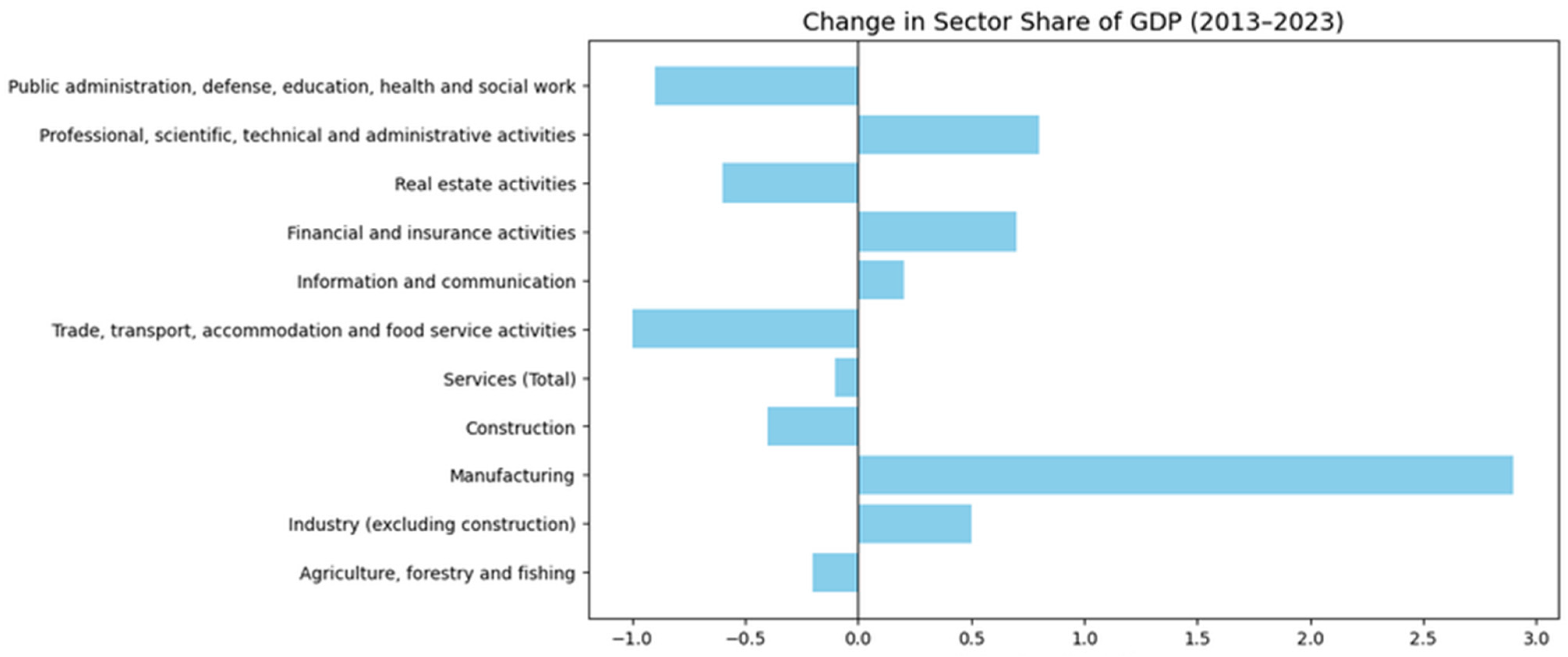

Figure 3 presents the change in each sector’s contribution to Gross Value Added (GVA) as a percentage of total GDP between 2013 and 2023. The bars indicate the net difference in sectoral shares over the period, showing relative expansion or contraction across major activities, including Manufacturing, Industry, Services, and Public Administration. The data are from ELSTAT (A64 classification) and are based on annual national accounts. Positive values represent sectors that gained share in total GVA, while negative values indicate relative decline. All values are expressed in percentage-point changes. GDP = Gross Domestic Product; GVA = Gross Value Added.

This bar chart highlights the net changes in sectoral contributions to GDP between 2013 and 2023. Manufacturing recorded the largest positive shift, gaining almost 3 percentage points, reflecting industrial strengthening within the economy. Professional, scientific, and technical activities, as well as financial services, also posted moderate gains, showing a trend toward knowledge- and finance-driven growth. By contrast, trade and transport services, public administration and health, and real estate activities declined slightly, indicating structural adjustments in traditional service-based sectors. Agriculture and construction remained relatively stable, with small negative shifts. Overall, the chart underscores a gradual diversification of the economy, with manufacturing and specialized services playing an increasingly important role.

The working hypothesis is that sectoral dynamics affect the weight of the service economy, and that sector-specific pressure groups influence these dynamics through lobbying, regulation, and institutional capture. An econometric analysis follows.

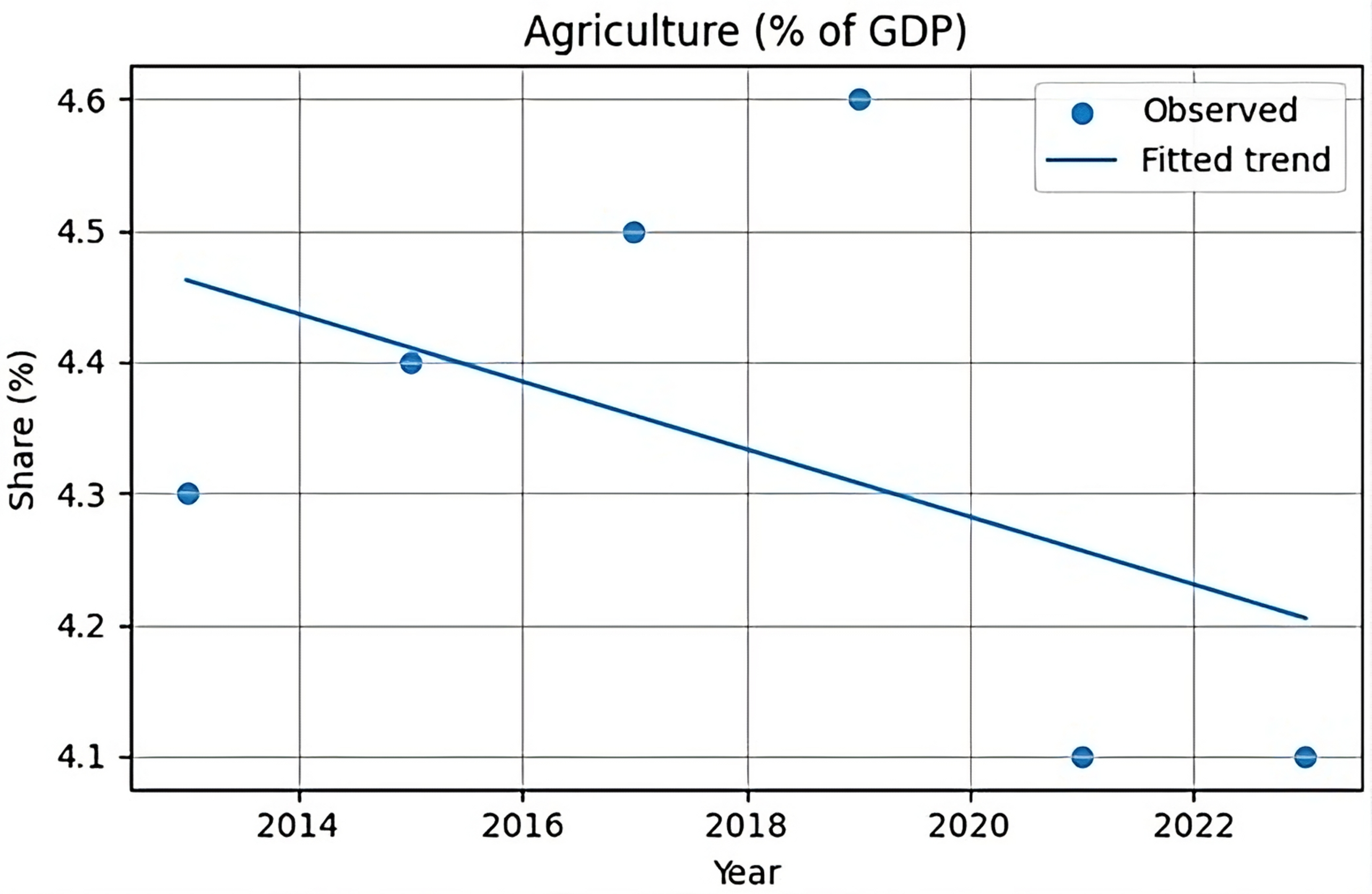

Figure 4 depicts the annual share of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing in Greece’s Gross Value Added (GVA) as a percentage of total GDP, alongside the fitted linear trend estimated from the log-ratio model. The data cover the period 2013–2023 and are drawn from the ELSTAT (A64 classification). Blue circles represent observed annual values, while the solid line shows the fitted trend based on a Newey–West heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) estimation. The downward slope indicates a gradual relative decline in agriculture’s contribution to total output. GDP = Gross Domestic Product; GVA = Gross Value Added; HAC = Heteroskedasticity- and Autocorrelation-Consistent.

This chart illustrates the evolution of agriculture’s share of GDP between 2013 and 2023. The observed data points fluctuate slightly, with peaks around 2017–2019, but the fitted regression trend reveals a gradual decline over the decade. The downward slope indicates that agriculture’s relative contribution to GDP is shrinking, consistent with structural shifts in the economy toward services and manufacturing. Despite temporary increases in certain years, the overall negative trajectory highlights the long-term weakening of the agricultural sector’s weight in national output.

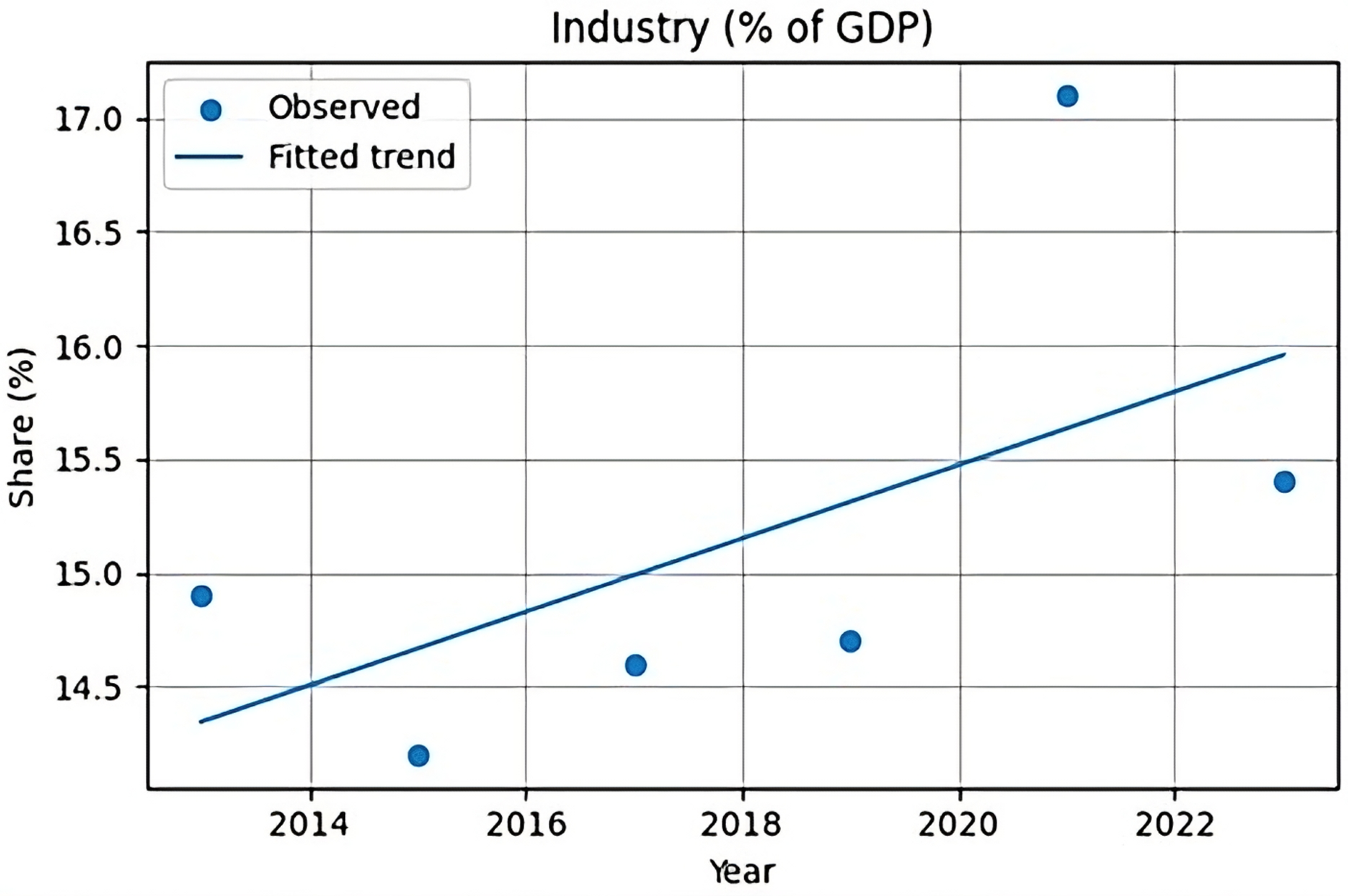

Figure 5 shows the annual share of Industry (excluding construction) in Greece’s Gross Value Added (GVA) as a percentage of total GDP, together with the fitted linear trend estimated from the log-ratio specification. The data refer to the period 2013–2023 and are obtained from the ELSTAT (A64 classification). Blue circles indicate observed annual values, while the solid line represents the fitted trend estimated using a Newey–West heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) model. The positive slope suggests a gradual strengthening of industrial output relative to total economic activity during the decade. GDP = Gross Domestic Product; GVA = Gross Value Added; HAC = Heteroskedasticity- and Autocorrelation-Consistent.

This chart shows the evolution of the industry’s share of GDP from 2013 to 2023. The observed data points fluctuate modestly, with a dip around 2015 and peaks in 2021, when the sector briefly exceeded 17%. Despite these ups and downs, the fitted regression line indicates a clear positive trend, suggesting that the industry’s overall contribution to GDP has been gradually increasing over the decade. This upward trajectory reflects a relative strengthening of industrial activity within the economy, potentially driven by growth in manufacturing and related sectors.

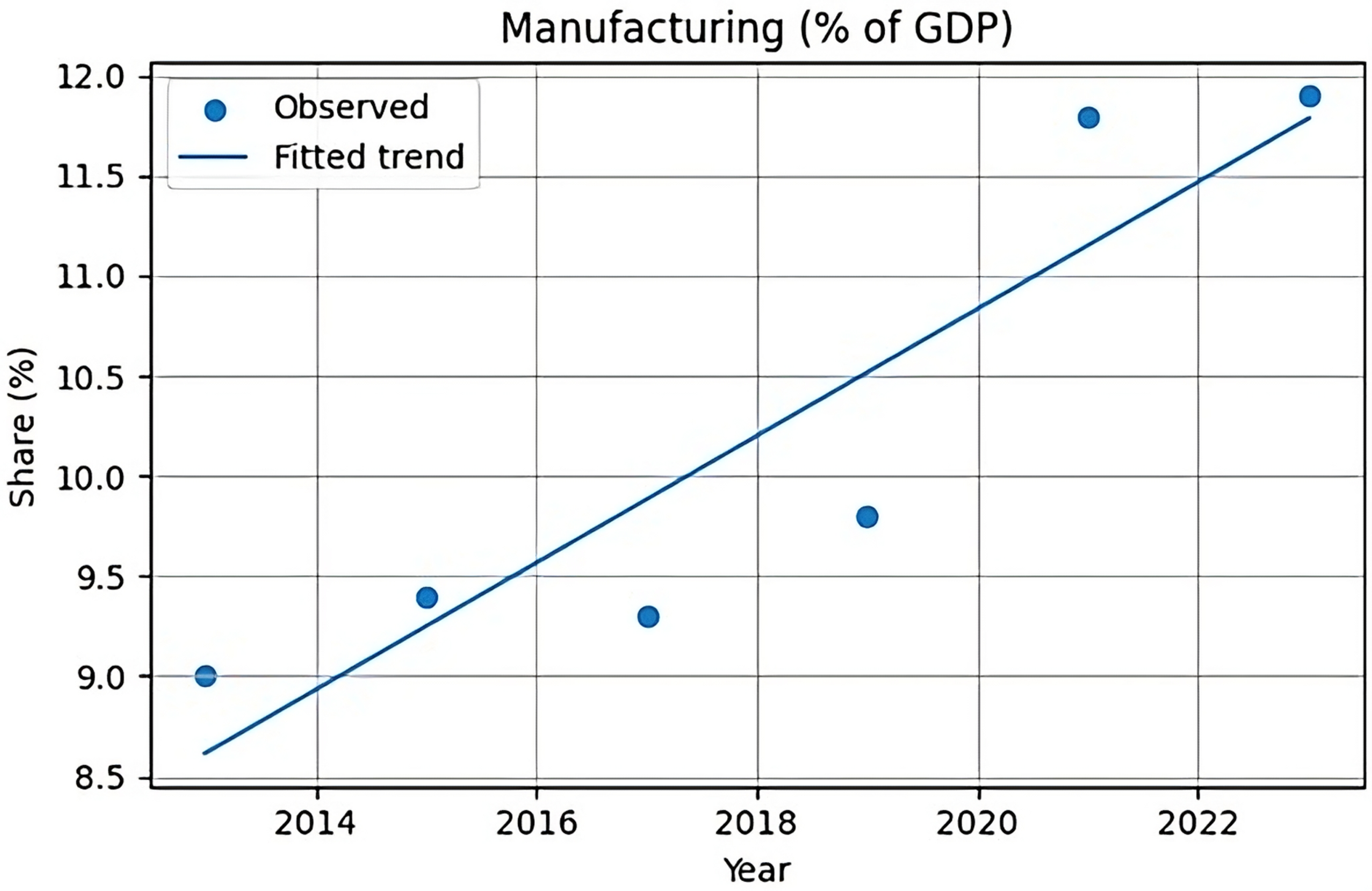

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of Manufacturing’s contribution to Greece’s Gross Value Added (GVA) as a percentage of total GDP, together with the fitted linear trend derived from the log-ratio specification. The dataset covers the period 2013–2023 and is sourced from the ELSTAT (A64 classification). Blue circles represent the observed annual sectoral shares, while the solid line indicates the fitted trend estimated using a Newey–West heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) approach. The pronounced positive slope reflects a clear upward trajectory in manufacturing output relative to total GDP during the examined decade. GDP = Gross Domestic Product; GVA = Gross Value Added; HAC = Heteroskedasticity- and Autocorrelation-Consistent.

This chart presents the trajectory of manufacturing’s share of GDP between 2013 and 2023. The observed data reveal an initial stability around 9%, followed by a noticeable increase after 2019, with the sector surpassing 11% by 2021 and approaching 12% in 2023. The fitted regression line shows an upward trend, indicating that manufacturing has been steadily gaining weight in the economy over the last decade. This expansion may reflect industrial recovery, rising exports, or policy support aimed at strengthening domestic production, positioning manufacturing as one of the most dynamic contributors to overall industrial growth.

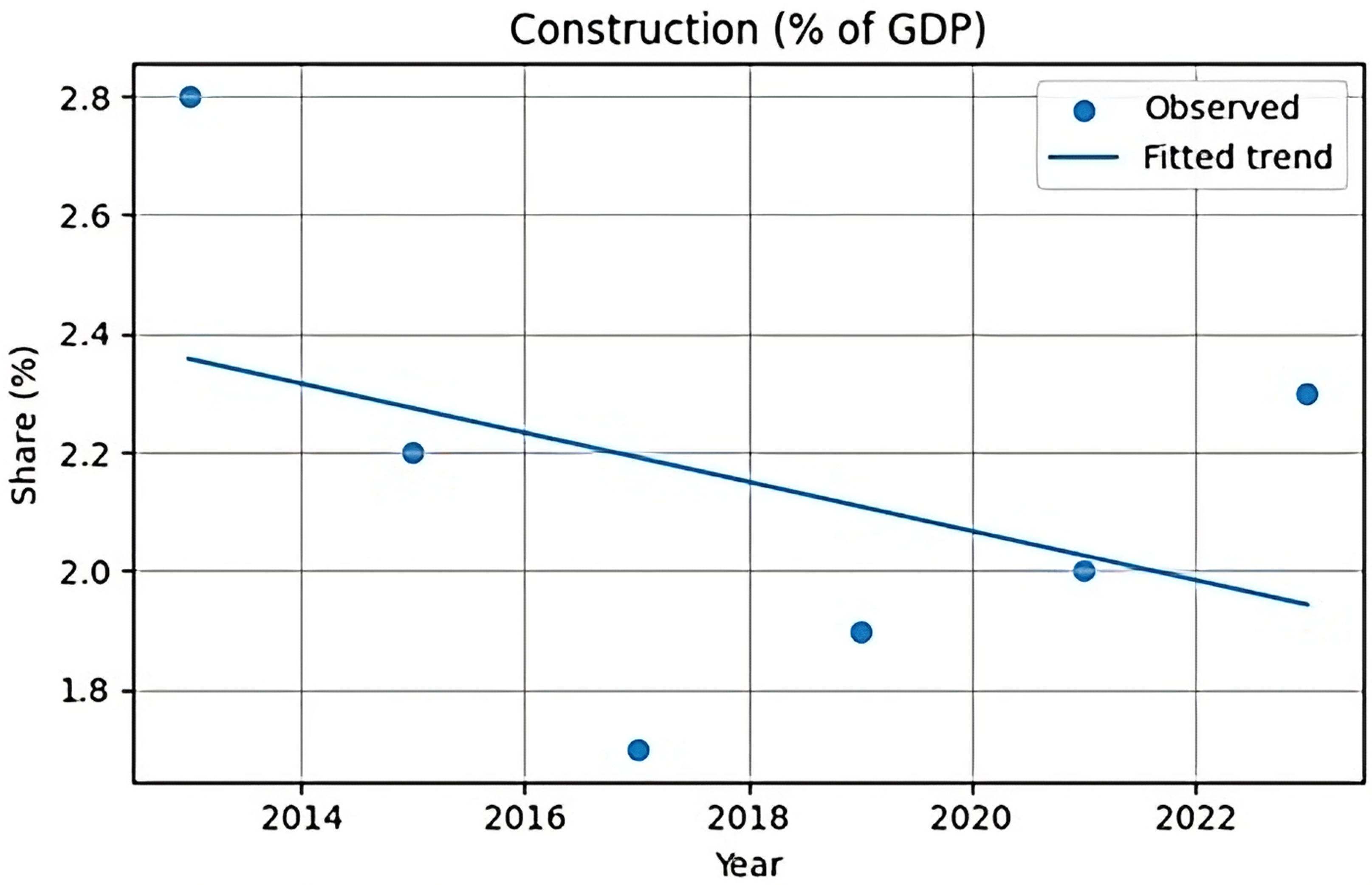

Figure 7 presents the annual share of the Construction sector in Greece’s Gross Value Added (GVA) as a percentage of total GDP, together with the fitted linear trend obtained from the log-ratio regression. The data cover the period 2013–2023 and are sourced from the ELSTAT (A64 classification). Blue circles denote the observed annual values, while the solid line represents the fitted trend estimated with a Newey–West heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) approach. The negative slope indicates a gradual contraction of the construction sector’s relative contribution to GDP during the examined decade. GDP = Gross Domestic Product; GVA = Gross Value Added; HAC = Heteroskedasticity- and Autocorrelation-Consistent.

The diagram shows the evolution of construction’s share of GDP from 2013 to 2023. The observed data reveal a steep decline after 2013, when construction contributed close to 2.8%, reaching a low point below 1.8% in 2017. Although there has been some recovery in recent years, the fitted regression line shows an overall negative trend, reflecting the sector’s diminished role in the economy over the decade. This pattern is consistent with the lasting effects of the financial crisis, subdued investment in infrastructure and housing, and the slower rebound of construction relative to other sectors. The empirical estimation for the period 2013–2023 is based on the log–ratio trend model, expressed formally, the marginal effect of time on the sectoral share ratio is as follows:

which implies the following:

The model is estimated via Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with Newey–West heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) standard errors. The resulting estimates are reported in

Table 2, where all coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level except for Agriculture, indicating strong explanatory power and structural consistency across sectors. The positive coefficients for Manufacturing (

) and Information and Communication (

) indicate that these sectors expanded by approximately 2.7% and 3.9% per year relative to Services, reflecting Greece’s ongoing technological transformation and industrial recovery [

102]. Conversely, the negative coefficients for Public Administration (

), Trade and Tourism (

), and Financial Services (

) signify contraction relative to Services, in line with fiscal consolidation and market liberalization during the post-crisis decade. The insignificance of Agriculture (

) suggests relative stability rather than structural decline. Overall, the model exhibits exceptionally high explanatory power (

) for most sectors, confirming that the period 2013–2023 was characterized by systematic, policy-driven realignment of economic activity toward innovation- and export-oriented domains.

The descriptive regression results, based on harmonized Eurostat and ELSTAT Structural Business Statistics series, reveal consistent trends across the major sectors of the Greek economy between 2013 and 2023. The fitted log–ratio models indicate that manufacturing and information and communication activities display sustained positive movements relative to services, while public administration, trade and tourism, and financial services show gradual declines. These tendencies are consistent with the hypothesis that sectors supported by strong and well-organized associations exhibit relative resilience and growth. However, since the model does not include quantitative measures of lobbying activity, the results should be interpreted as illustrative correlations rather than definitive causal effects. The findings, therefore, suggest rather than confirm that institutionalized lobbying capacity and organizational structure correspond with sectoral adaptability and persistence in the Greek economy.

Dependent variable: log of sectoral share relative to Services has an estimation period 2013–2023, where OLS with Newey–West HAC standard errors is considered based on significance codes: ***

, **

, *

. The regression results of

Table 2 derived from Equation (6) demonstrate statistically significant and economically meaningful trends across all major sectors of the Greek economy. The model applies a log-ratio specification of sectoral GDP shares relative to the Services sector, thus correcting for compositional dependence and providing unbiased estimates of each sector’s growth trajectory. The coefficient

represents the average proportional annual change in each sector’s share relative to Services, with the corresponding

indicating explanatory power and

p-values reflecting statistical reliability under robust Newey–West estimation.

The results confirm a dual structural transformation of the Greek economy during the period 2010–2023. On the one hand, Information and Communication (β = 0.0395, p < 0.01) and Manufacturing (β = 0.0267, p < 0.01) exhibit strong and significant positive trends, with average annual increases of 3.9% and 2.7%, respectively, relative to Services. These findings validate the hypothesis of an ongoing technological and industrial revival, driven by digitalization, export reorientation, and post-crisis competitiveness policies. Both models achieve very high explanatory power (), indicating that over 95% of the variation in these sectors’ relative shares is explained by the time trend alone—a clear signal of structural rather than cyclical evolution.