Abstract

This study aims to examine the loss and damage experienced by coastal regions from the perspective of adaptation. It also seeks to evaluate the adaptation techniques employed when migration is utilized as a significant approach to mitigate the effects of loss and damage on coastal communities. This study evaluates the extent of loss and damage caused by constraints on adaptation. Two districts, Khulna and Satkhira, in the Khulna division of Bangladesh, were chosen for the study. In these districts, a total of twenty-four detailed interviews and one focus group discussion (FGD) were conducted with individuals living in rural areas whom climate-related effects and disasters have impacted. Additionally, seven interviews were conducted with climate migrants residing in informal settlements within the words of Khulna City Corporation. The process of identifying appropriate interview candidates involves utilizing a combination of specific criteria and snowball sampling techniques. The study employed NVivo 14 software to conduct theme analysis on textual data obtained from interviews. In the coding procedure, we sequentially employed semantic coding, latent coding, categorization, pattern exploration, and theme creation, all of which were in line with the research aim. The study indicates that most affected persons utilize seasonal and temporary movement as an adaptive strategy to deal with the slow effects of climate change, such as increasing temperatures and salinity in rural regions, and when they encounter limitations in their ability to adapt. Conversely, they opted for permanent migration in response to stringent constraints imposed by severe climate events like cyclones and river erosion, leaving them with no alternative but to move to urban regions. Social networks are crucial in influencing migration choices, as several families depend on information provided by urban relatives and rural neighbors to inform their relocation decisions. Nevertheless, not all individuals impacted by the situation express a desire to relocate; others opt to remain in rural areas due to their sentimental attachment to their birthplaces and a sense of dedication to their ancestral territory. Due to the exorbitant cost of urban life, they believe that opting not to migrate is a more practical option for addressing the repercussions of climate-induced loss and damage. The study’s findings aid policymakers in determining migration strategies and policies to address the adverse effects of coastal population displacement in Bangladesh. Additionally, it aids in determining strategies to address the challenges faced by climate migrants in both urban and rural environments.

1. Introduction

The concept of loss and damage has recently gained recognition and official status within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This occurred after the adoption of the Cancún Adaptation Framework (CAF) during the 16th session of the Conference of Parties in 2010. The CAF prioritizes and maintains the importance of global collaboration among the involved parties to recognize and mitigate the negative consequences caused by climate-induced catastrophes [1]. CAF subsequently emerged as a prominent contributor in developing a functional program on Loss and Damage through the subsidiary implementation body. Ultimately, the CAF successfully concluded a comprehensive procedure during COP 19 in Warsaw, referred to as the ‘Warsaw international mechanism for loss and damage’ [2]. Two additional noteworthy announcements have been made since COP 26 in Glasgow, leading up to COP 27. The first is the introduction of ‘The Glasgow Climate Pact’, which includes the initial announcement of financial support for Loss and Damage. The second announcement was made during COP 27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, where a commitment was made to establish a fund for Loss and Damage specifically for developing countries. Additionally, discussions were held regarding Loss and Damage in relation to vulnerability [3,4].

Loss and Damage, as defined by the UNFCC, refers to the negative consequences on social systems that are often caused by the harmful effects of climate change on natural systems. The literature frequently discusses L&D as the negative consequences of climate change on human civilization, including their fundamental rights and basic needs. These consequences are generated by severe and slow-onset catastrophes that cannot be effectively handled by existing adaptation and mitigation efforts [5,6,7,8]. When discussing Loss and Damage, two specific aspects are commonly addressed. The technical dimension encompasses the instruments and techniques used to address, evaluate, monitor, and control the Loss and Damage. On the other hand, the political dimension focuses on the limits of climate adaptation, compensation, and fairness. The definition of Loss and Damage establishes the legal parameters and interpretation of the consequences and responsibility for the impact of climate change. This aids in the negotiation of climate funding by explaining the causes and liabilities associated with climate change [1,9]. Nevertheless, the majority of the research categorizes L&D into four typologies: Adaptation and Mitigation, Risk Management, Limits to Adaptation, and Existential [5,10]. The Adaptation and Mitigation perspective primarily centers on the current initiatives and mechanisms established by UNFCCC, which are adequate for tackling Loss and Damage (L&D). The Risk Management approach focuses on pre-emptive strategies to mitigate disaster risks, as well as methods of retaining and transferring those risks. These measures can be categorized within the scope of com-prehensive risk management. Loss and Damage are a consequence of Limits to Adaptation, wherein the current abilities to adapt and cope with climate change are no longer sufficient to mitigate its adverse impacts. From an Existential standpoint, L&D can be understood as enduring and lasting transformations and unavoidable damages, such as post-traumatic stress caused by extreme events and loss of identity and feeling of belongingness [10].

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change defines adaptation in human systems as the process of adjusting to the present or predicted climate and its impacts to mitigate harm or take advantage of advantageous opportunities [11]. In order to lessen the adverse effects and the loss and damage, it is necessary to reinforce the current adaptation measures due to the increasing scope of climate risk [12,13]. The increasing level of climate risk makes it more difficult for climate specialists to determine the point at which nature and humans can no longer tolerate the risk in order to protect their most important goals—health, well-being, or livelihood—by taking adaptive measures [13,14,15,16,17]. The limit of adaptation is at this point. As a result, the boundaries of adaptation are the points at which unacceptable risks materialize, causing both concrete and intangible losses as well as damage that cannot be adequately mitigated or adjusted for [10,17]. According to the literature, there are two different kinds of limits: the ‘Soft Limit’, which occurs when a human system’s adaptation reaches its maximum level due to a lack of specific options that could either avoid the intolerable risk or make it tolerable, and the “Hard Limit”, which occurs when a particular natural system loses its ability to avoid intolerable risk through its adaptive action [17].

Interestingly, ‘migration’ appears as one of the keywords under the ‘limits to adaptation’ perspective of Loss and Damage [10] when explaining the four perspectives of L&D through some keywords that represent its underlying perspective. These keywords include limits to adaptation, adaptation limits, adaptation constraints, physical limits, social limits, beyond adaptation, residual loss and damage, residual impacts, migration, saline intrusion, agriculture, non-economic losses, climate-related stressors, community-based values, livelihoods, resilience, vulnerable, poor and marginalized, developing countries, and micro insurance. The phrase ‘limits to adaptation’ is often used in conjunction with the term ‘migration’, which is not surprising given that migration is seen in literature as an adaptation [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Wiederkehr et al. conducted a meta-analysis on adaptation in Sub-Saharan African dryland, analyzing 63 research including over 6700 rural families. The findings indicate that 25% of rural households employ migration as a method for adaptation [24].

The International Organization for Migration was the first to integrate the idea of ‘migration as adaptation’ into numerous practice-oriented discourses [25]. This notion gives migrants a more favorable image than the contentious narratives of ‘climate refugees’. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other actors took notice of this reinterpretation of migration as a potential adaptation strategy. It is reflected in various strategic frameworks and documents, including the Cancún Adaptation Framework [26], the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction [27], and the Global Compact for Migration [28]. Households often evaluate all of the adaptation options that are available to handle threats and select the best ones depending on the situation, which may include making the deliberate decision to migrate if the chance arises [29,30,31,32]. Migration’s capacity for adapting frequently leads to money-making, livelihood diversification, risk-sharing, and social or financial remittances [33]. The idea of migration as adaptation frequently highlights the proactive nature of migration decisions and implies a positive relationship between migration and adaptation processes, which is a type of proactive planning. However, a number of factors, such as household capacities and settings, influence the decision to migrate [23]. In actuality, migration frequently occurs as a result of transient coping mechanisms as opposed to anticipatory adaptation. In actuality, migration does not always seem to be the primary adaptation option—especially when a family is involved [23]. As a result, there are several varieties, such as forced and voluntary migration. While it is preferable to view migration as a choice for adaptation [20], there are numerous situations in which moving elsewhere to escape a dangerous environment is the only alternative [23]. Migration, particularly when planned for over a longer time horizon, might worsen the already existing vulnerability of the migrants by failing to secure livelihoods, even while the term adaptation favors households’ success in moderating environmental hazards. This unsuccessful form of migration is referred to as erosive or maladaptation in the literature [34]. According to numerous Southeast Asian studies, there has been no improvement in household wealth or food security despite a high level of migration [35]. Eventually, a lot of relocations seem to have favorable effects in the short term but ultimately prove to be maladaptive in other facets of life [36,37,38]. However, when a new site allows migrants to practice new livelihood skills, relocations can enhance adaptive capacity [39]. In addition to all of the above, migration may also pose problems for non-economic factors like mental and emotional health, traditional livelihoods, and cultural heritage. Furthermore, scholars contend that migration cannot be considered effective until it prevents harm to people’s identities, customs, knowledge, social structures, and material cultures [40]. In order to allow individuals to remain in their native areas, development initiatives should concentrate on reducing migration pressures [23]. Migration as adaptation seems to be the result of a governance vacuum in many circumstances. Communities employ remittances to fill funding gaps for activities to reduce climate change resilience due to inadequate coverage of national and international support [41]. Thus, the figure distinguishes between two types of migration: proactive migration, which involves assessing risks in advance and making the decision to migrate, and survival migration, which happens as a reaction to an environmental shock [42]. In the latter case, survival migration seems to be more common following rapid-onset hazards, like disasters, which pose an immediate threat and force populations to relocate [23].

This study centers on involuntary migration, which is deemed undesirable for individuals who depart from their country of origin due to the disruptive effects it has on traditions, economies, social order, cultural identity, and knowledge [14]. Destructive forces have been exacerbated by the impacts of climate change for an extended period. Rapid urbanization is an additional consequence of this effect, which has led to human displacement as one of its main effects. However, this unsustainable expansion exacerbates the precarious situation of urban climate migrants [22,43]. As a consequence of the detrimental effects of climate change, households that are impacted frequently are compelled to relocate to urban areas in close proximity as a means of economic survival [22,44]. Hence, it can be asserted that the recent surge in climate migrants’ inclination serves as confirmation that the native inhabitants have already endured devastation and loss [45]. Therefore, climate change vulnerability, climate-induced migration as a strategy for adaptation to climate-induced disasters, and loss and damage as consequences of climate change have emerged as significant areas of concern for climate practitioners and researchers [22,44]. In addition to the concept of “Migration as Adaptation,” current research is also examining resilience and vulnerability to climate-related risks, coping mechanisms, and adaptive capacity. However, these pertain primarily to the realm of theory [30,46,47].

Our research focuses on the littoral region of southwestern Bangladesh. Proximity, livelihood, climate change vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation, as well as poverty, have been the subject of numerous studies which indicate that climate risk exists in this region of Bangladesh. Due to its frequent exposure to climate-induced catastrophes (e.g., floods and cyclones), the southwestern littoral region of Bangladesh may be regarded as a potential nadir for climate migrants. Consequently, one of the primary destinations for these individuals is identified as Khulna City Corporation, the third most expansive city in Bangladesh, which serves as the closest territorial center [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. The purpose of the study is to investigate the loss and damage of coastal regions from the standpoint of adaptation, as well as to determine when migration becomes a crucial strategy for mitigating L&D effects. Concurrently, this study assesses harm and loss caused by adaptation constraints. This paper begins by elucidating how climate-induced calamities exacerbate pre-existing vulnerabilities, thereby causing detrimental consequences such as damage and loss of livelihood for marginalized communities residing along the southwestern coast of Bangladesh. Additionally, the paper endeavors to elucidate the critical juncture at which victims of climate change are unable to avert this devastation and loss. Put simply, their capacity to adapt is exhausted, and as a result, they are unable to persist in their original habitat while enduring the detrimental consequences of climate change. As a result, they employ migration as a means of adaptation. It is critical to establish clear criteria for identifying the victims of climate change and determining which individuals warrant special attention in order to assist them in escaping the predicament they have created for themselves, having it be a reward for them rather than a direct consequence of their actions. Consequently, this paper will contribute to the pertinent field for the following reasons: (i) The majority of L&D research has been conducted in developed nations, with institutions in Europe and North America contributing to over 70% of L&D studies. Hence, it is imperative to conduct further research emanating from developing nations such as Bangladesh [5], (ii) it is challenging to ascertain the boundaries of adaptation due to the multitude of possible measurements [55], (iii) our current comprehension of migration as adaptation appears to be limited in terms of intangible and non-material dimensions, (iv) it is uncommon to establish connections between the places of origin and destination when examining migration as adaptation [17,56], and (v) subjective research addressing loss and damage from a limit to adaptation perspective is scarce.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

Vulnerability comprises both external and internal dimensions. The external facet is linked to risks, shocks, and stresses that individuals may face. In contrast, the internal facet is associated with a lack of capacity to cope without incurring damaging losses [57]. Predictable risks, such as seasonal deficits, can be considered stresses, while more unpredictable and unexpected events are regarded as shocks [58,59]. The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) defines adverse events originating externally, like natural hazards (e.g., earthquakes), as shocks. At the same time, risks arising from within households, such as disability or sudden illness, are termed stresses. Stress is, therefore, more predictable, internal, and inherent to households [60]. Repeated shocks can ultimately amplify stress for the vulnerable poor [60]. In the context of climate change literature, vulnerability is commonly classified into two categories. The first pertains to the potential damage caused by a specific climate-induced event or hazard (e.g., floods, cyclones, saline intrusion) [61,62,63]. This category encompasses both slow-onset events occurring over extended time frames (e.g., years to decades), like sea level rise, coastal erosion, and temperature changes, and rapid-onset events taking place over shorter durations (e.g., hours, days, or weeks) like floods, cyclones, and wildfires [64]. The second category of vulnerability involves the state that exists within a system before encountering a hazard event [65,66,67]. Socio-economic vulnerability is an example constructed by the socio-demographic, economic, and physical infrastructure profile of a household or community, excluding biophysical parameters. It encompasses attributes such as density, education, well-being, race, age, social class, employment, ethnicity, elderly population, and the quality of the built environment [51]. When a hazard affects this socially and socioeconomically vulnerable population, it transforms into a disaster for the affected households and communities [60]. Following a disaster, attention turns to adaptation strategies, encompassing both physical responses to mitigate or avoid hazards and socially determined, economic, and political measures for vulnerability reduction. Adaptation strategies also explore a range of asset-based preparedness measures that poor households and communities deploy during and after disasters [60].

Adaptation reaches its limit, which may be hard or soft [10,17], when the alternatives at its disposal are inadequate for both contending with the consequences of hazards and adaptation. In the event that a household or individual decides to migrate at this particular moment, it is classified as involuntary or coerced migration [23]. The ‘cascade effect’—a series of consequences initiated by a system-affecting action—includes migration, environmental degradation, increased urbanization, and diminished human security [68]. Migration is identified as one of the three manifestations of climate change’s influence on the urban poor. According to the findings of Roy et al. [69], the 2009 Sidr and Aila cyclones in Bangladesh caused the displacement of tens of thousands of individuals from coastal villages to urban areas. Additionally, 70% of the slum dwellers in Dhaka had encountered some form of environmental shock, according to the IOM report. Cascading toward a safer and more favorable existence, urban squalor residents who migrate due to climate change do so in the end. The predominance of their slums in environmentally hazardous, low-lying areas and their lack of access to essential amenities, including food, shelter, sanitary conditions, and medical care, may exacerbate their predicaments. Households impacted by climate migration might encounter obstacles in leveraging urban expansion as a result of their limited human capital [60].

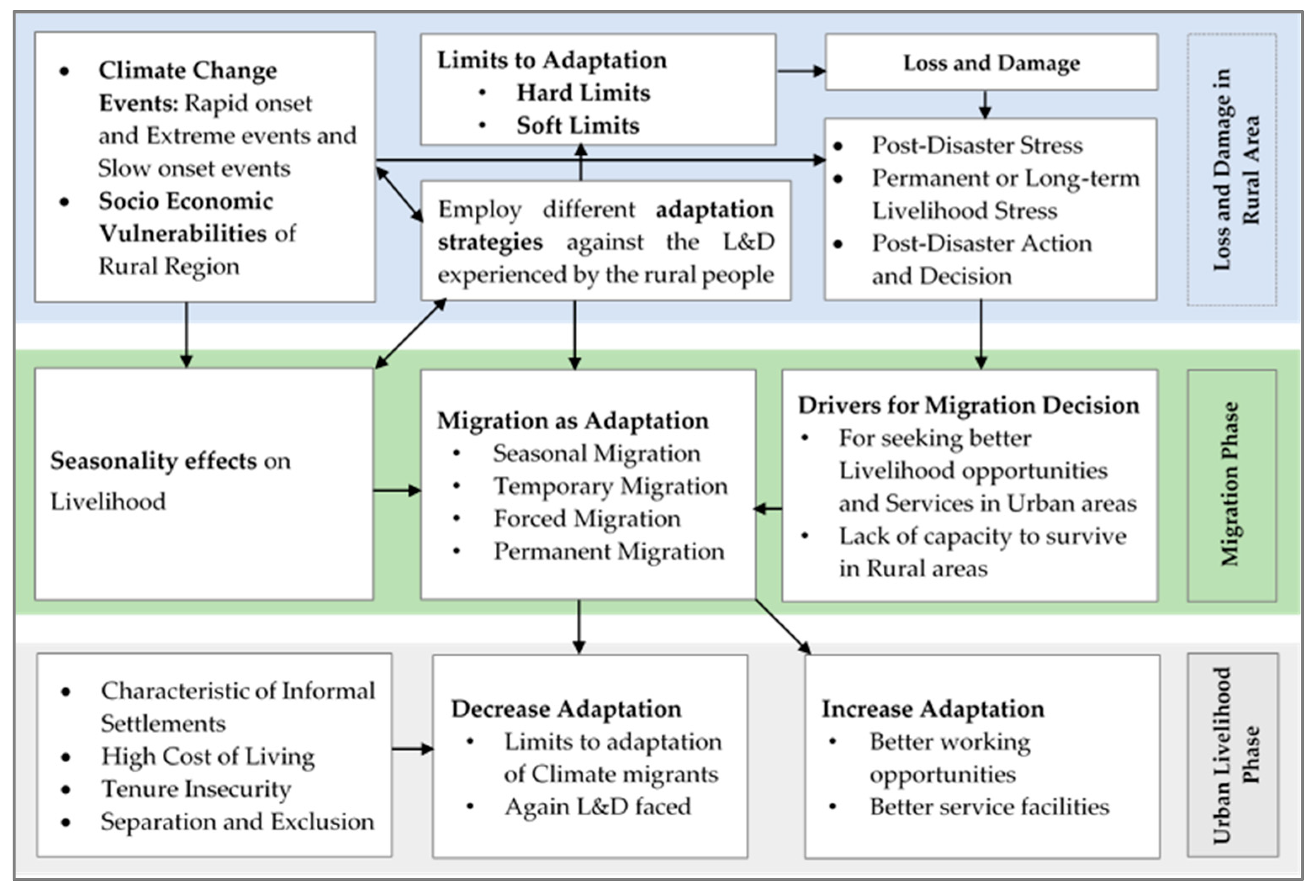

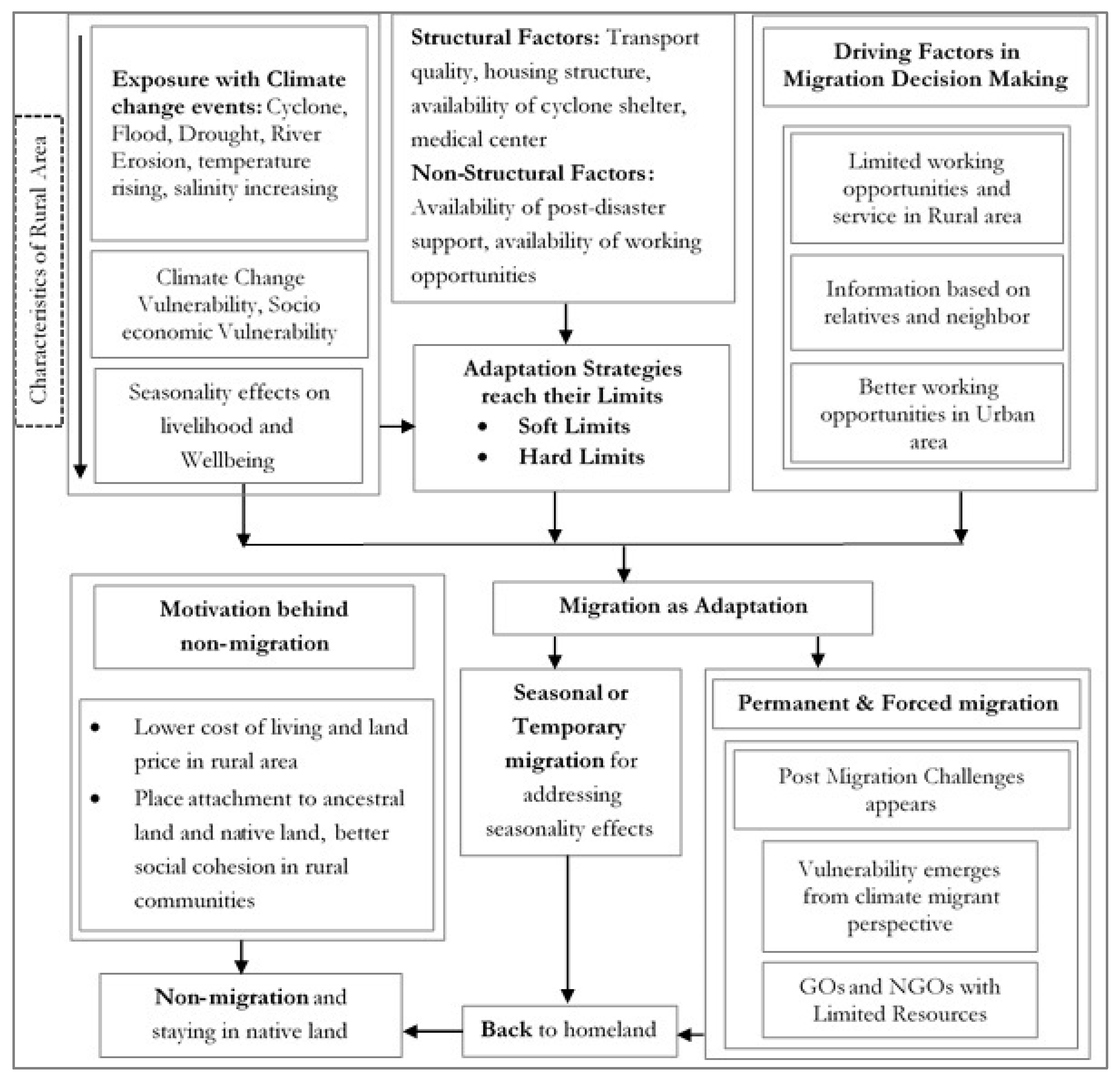

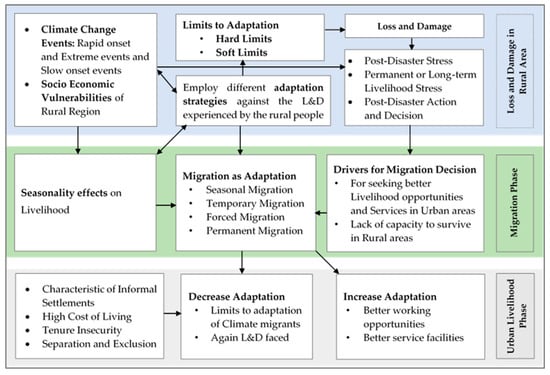

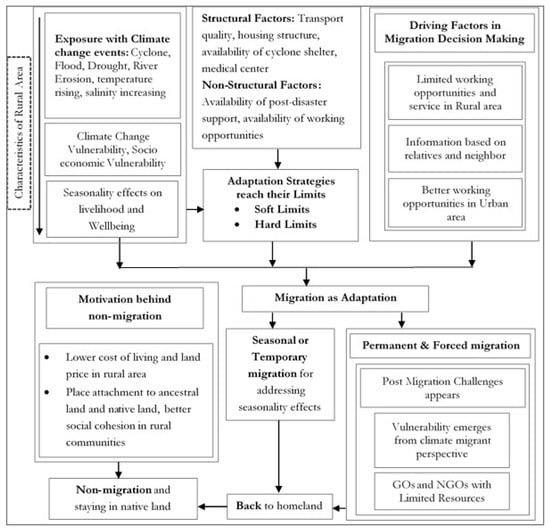

We conceptualize loss and damage in our research from the standpoint of adaptation (see Figure 1 for details). As an illustration, loss and injury result from adaptation limitations. In order to conceptualize L&D from an adaptation standpoint, we establish connections between various concepts, including climate change events, adaptation strategies, adaptation capacity, adaptation limits, migration as adaptation, and post-migration conditions. Adaptation in rural regions, the migration phase, and adaptation in urban regions subsequent to migration constitute the three main phases of this framework. Due to climate-induced disasters and occurrences, the afflicted population encountered two types of adaptation limits (hard limit and soft limit) during the initial phase. In general, rural inhabitants encounter numerous challenges that impact their standard of living and overall welfare. One such significant influence on their means of subsistence is seasonality. Rural inhabitants need more employment prospects. To achieve this, they implement a variety of adaptation strategies. Once more, the rural families are confronted with enduring consequences of the catastrophe on their means of subsistence and overall welfare. Deterioration and loss induce them to consider migration options. Migration decisions are influenced during the migration phase by post-disaster challenges and seasonal effects. In this region, individuals employ various migration patterns in accordance with the magnitude of destruction and loss. During the third phase, climate migrants encounters distinct post-migration obstacles in urban areas as a result of slum settlement characteristics, exclusion, and lack of access to necessities and services. Additionally, this condition negatively affects their wellbeing and means of subsistence.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework on loss and damage from an adaptation perspective.

2.2. Study Area

The research is being carried out in two specific districts, Khulna and Satkhira, which are located in the Khulna division of Bangladesh. The Khulna Division spans around 21,643.30 square kilometers and is situated between latitudes 21°60′ and 24°13′ north. Rajshahi, Pabna, and Natore border the district to the northeast and Faridpur, Pirojpur, Gopalganj, Rajbari, and Barguna to the east. Additionally, it encompasses the Sundarbans. The area includes the extensive floodplains of the Ganges, a portion of the lower Meghna Rivers, and both established and recently formed parts of the Ganges curve basin.

Both Khulna and Satkhira are located in an expansive coastal area that regularly experiences climate-induced disasters, including tropical cyclones, tidal surges, flash floods, river erosion, and erratic rainfall. The districts are susceptible to a diverse array of recurrent and consistently present climate-related dangers. Floods and tidal surges are frequent and recurring climatic phenomena, whereas cyclones occur occasionally with lower frequency but greater intensity [51].

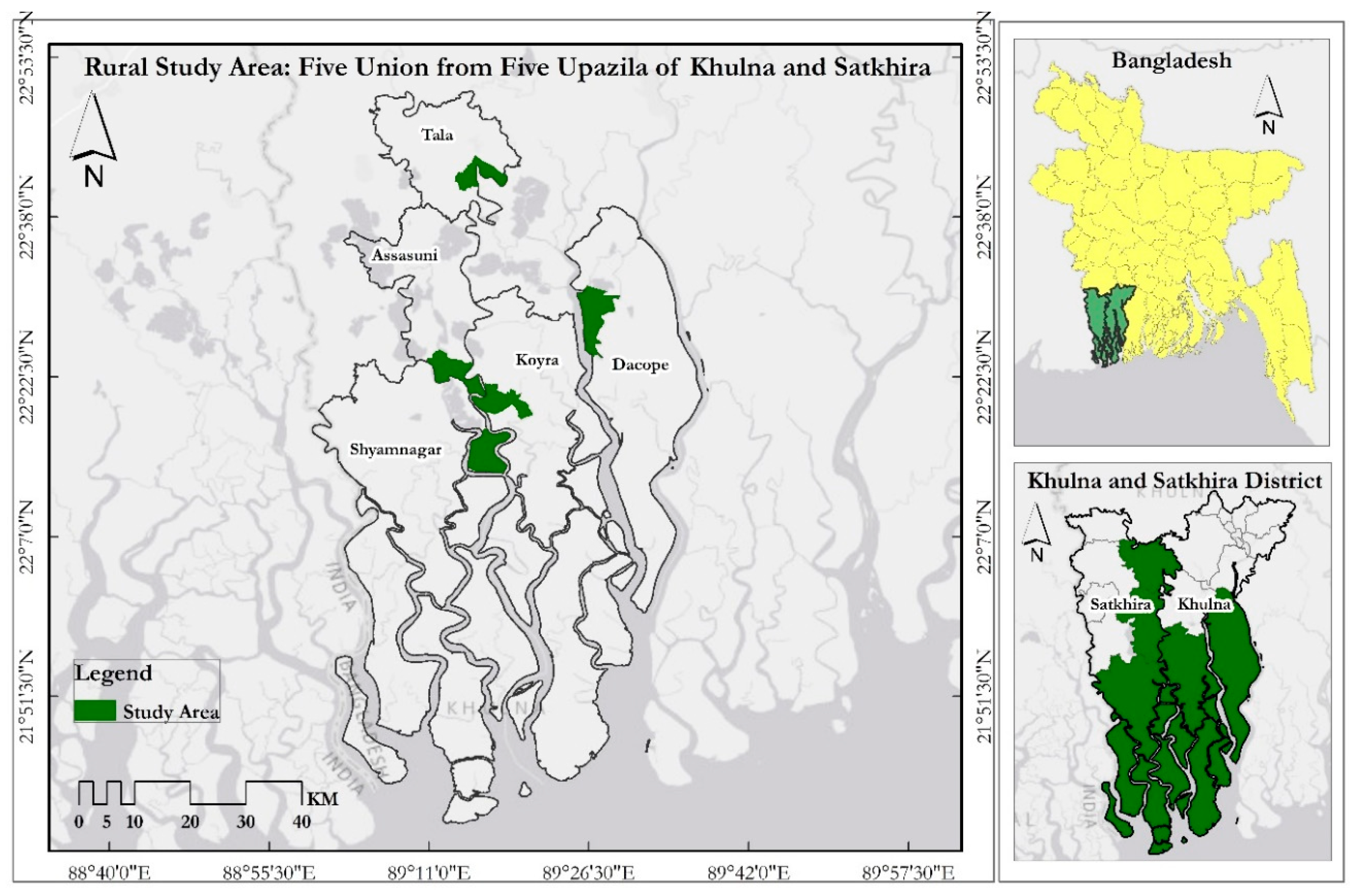

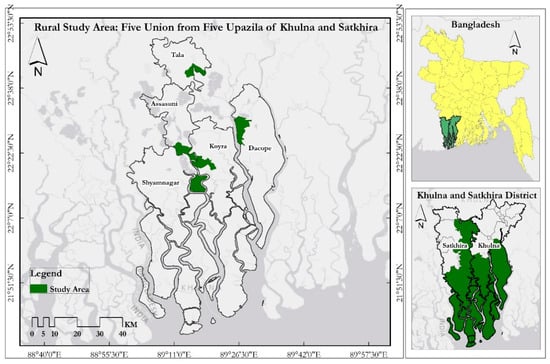

The indicated districts offer a setting where the interplay between vulnerable rural communities and the negative consequences of climate change is intricate. Additionally, the metropolitan areas in these districts, which see a significant influx of climate migrants, provide an ideal context for this study. The study focused on two unions in Khulna district, Sutrakhali union in Dacope upazila and Koyra union in Koyra upazila, as well as three unions in Satkhira district: Pratapnagar union in Assasuni upazila, Gabura union in Shyamnagar upazila, and Jalalpur union in Tala upazila, in order to examine rural populations (see rural locations in Figure 2). These places are located in the most vulnerable zone to severe climate events.

Figure 2.

Place of origin of climate-induced migration.

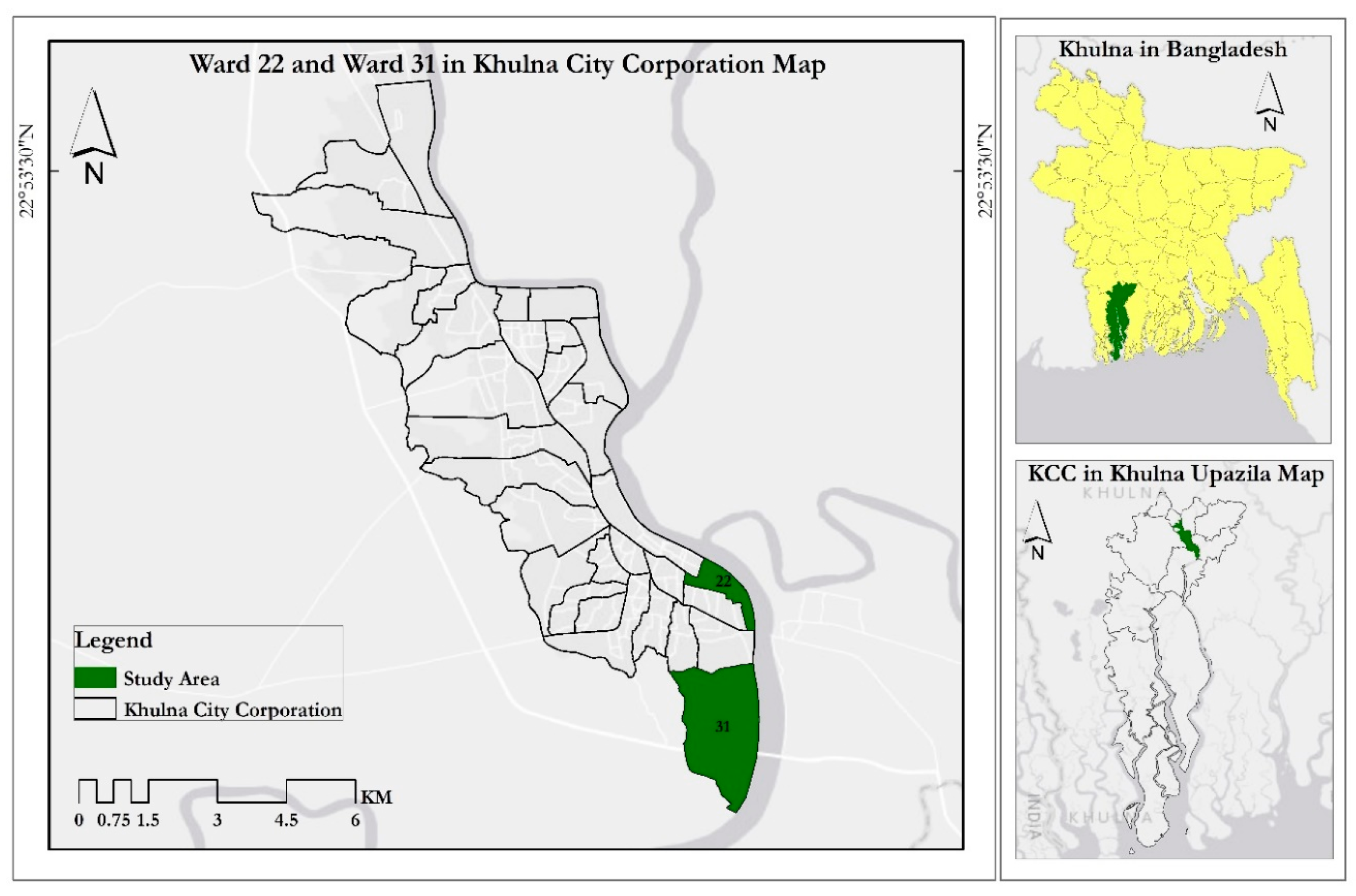

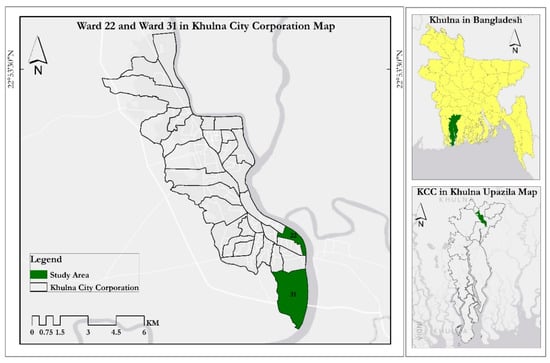

In order to determine the appropriate study area, we conducted an analysis of existing literature pertaining to climate change occurrences in the southern coastal region of Bangladesh. The study area was selected by identifying the region most susceptible to climate change events, as delineated in prior studies. The unions in southern coastal Bangladesh were classified as regions with high to extremely high socio-economic vulnerability [51]. Furthermore, these unions are significantly impacted by climate-induced disasters and are acknowledged as locations with a high susceptibility to such events [70]. In order to comprehend the effects of climate change on the urban climate migrants from southwest coastal Bangladesh, we also looked into the literature. The research leads us to choose the informal settlements from Khulna City Corporation’s Wards 22 (Notun Bazar, Rupsha Slum) and 31 (Matha Vanga, Lobon Chora) as our study area (see urban locations from Figure 3) based on the concentration of climate migrants [71,72].

Figure 3.

Place of destination of climate migrants.

2.3. Sampling Technique

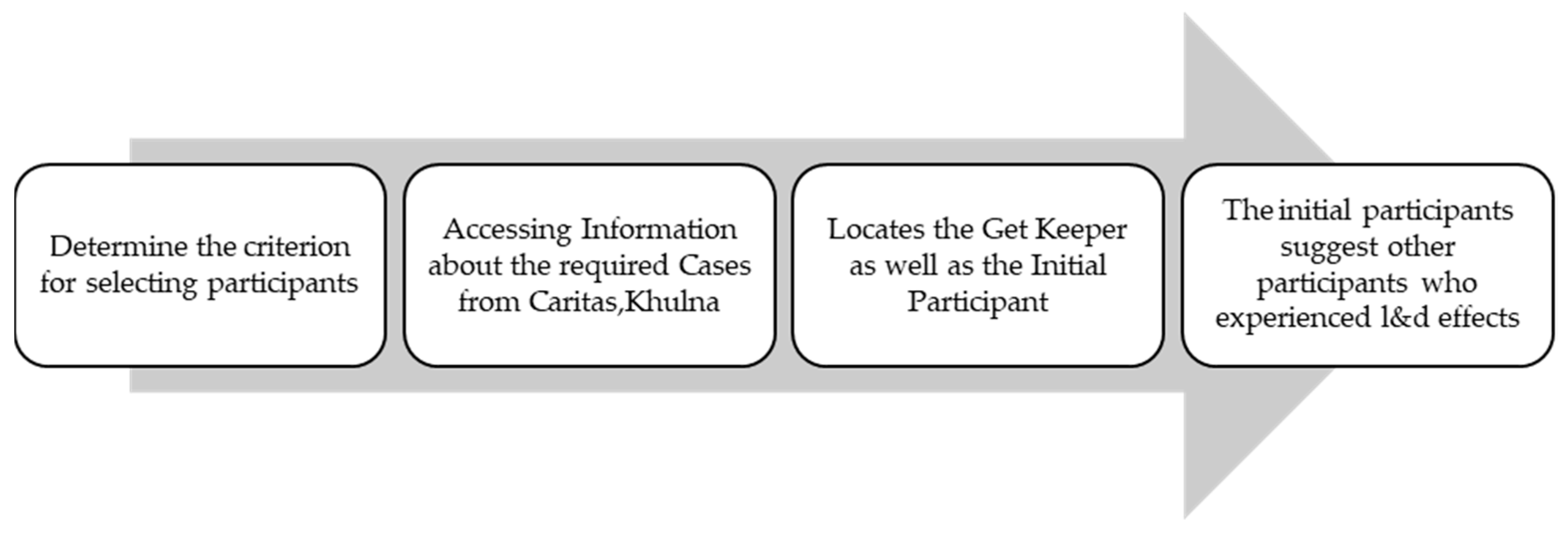

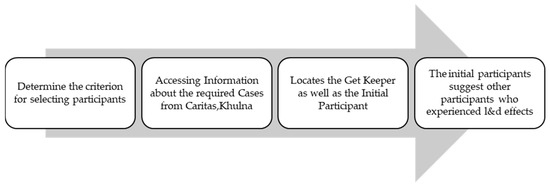

The study utilizes a purposive sample method that is in line with the research goals. A criterion sampling approach is utilized to identify participants in the selected study locations. Criterion sampling involves the selection of all examples that satisfy a preestablished relevance criterion [73] (see Figure 4 for details). This study selects individuals residing in rural areas located in the coastal communities of Khulna and Satkhira districts (see Table 1 for details). These places are prone to frequent extreme climatic occurrences as a result of their geographical positioning.

Figure 4.

The procedure of choosing urban migrants via purposive sampling.

Table 1.

Sample allocation in the place of origin of the climate migrants (rural region).

On the other hand, people living in cities are individuals who experience different climate change events, which makes it difficult for them to deal with the adverse effects (see Table 2 for details). As a result, they are forced to move temporarily or permanently from their original places to metropolitan regions. The urban area of the study is delineated based on data provided by local non-governmental organizations that have previously engaged in impoverished urban communities. The process involves identifying first participants or key informants from certain informal urban groups by utilizing existing databases. The study utilizes a snowball sampling approach to identify supplementary participants who are deemed relevant. This involves primary data sources suggesting other prospective primary data sources for the research [74].

Table 2.

Sample allocation in the place of destination of the climate migrants (urban region).

2.4. Data Collection

The researchers conducted comprehensive interviews using a predefined checklist in both the location where the climate migrants originated and their destination. This is a technique used for qualitative research. The study’s objectives and the significance of the findings were initially communicated to the participants. The interviews were recorded with the subject’s explicit consent. Prior to doing our research, we familiarized ourselves with the environment and established a connection with the participants. This was done in order to establish trust and gather accurate information pertinent to our study.

Prior to venturing into the field, a checklist was meticulously devised by incorporating insights from experts and thoroughly examining relevant literature. The checklist comprises essential open-ended questions that were maintained during the interview to prompt the interviewer to monitor the achievement of study objectives and prevent superfluous talk. To investigate the impacts of climate-induced migration on metropolitan areas, a set of open-ended questions was designed to examine the consequences of loss and harm experienced by individuals before and after their relocation. The IDI conducted in rural areas with the affected individuals included a checklist comprising open-ended inquiries pertaining to their socio-economic status, stress levels, and exposure to climate-induced hazards. The checklist also explored their methods of coping and adapting to these hazards, the extent of institutional support available to them, and their social network in dealing with the stress caused by climatic events.

In order to select participants from rural areas, we previously gathered quantitative data to examine the vulnerability of households to climate-induced disasters. By quantifying this data, we were able to identify homes that were significantly impacted. We made an effort to contact these households and picked our respondents from among them. However, this study did not derive any conclusions from the quantitative data: it was solely utilized for sample selection. To choose respondents from the metropolitan area, we initially conducted surveys in multiple slums to identify climate migrants. However, we discovered that there are several slums where we did not encounter any climate migrants. Following this, we visited NGO offices with prior experience in assisting climate migrants in Khulna City. The objective was to review the list of slums identified by a higher concentration of climate migrants. Based on their recommendations, we visited these locations and aimed to investigate individuals who have been affected by climate-induced events. These individuals had migrated from rural areas to urban centers in the last decade due to the impact of climate-related occurrences. We identified climate migrants based on the preset criteria in two informal settlements within Khulna City: Matha Vanga and Lobonchora in Ward 31 and Notun Bazar and Rupsha in Ward 22. In addition to the rural area, we have also conducted a quantitative questionnaire study and obtained data from climate migrants. Although we did not utilize these quantitative data in our study, we collected this data to obtain participants’ phone numbers and engage in contacting with them to determine their availability and preferred time for an interview. As previously stated, they are primarily occupied with their everyday employment to generate income and manage domestic responsibilities. Occasionally, the respondent needed more willingness to allocate a substantial amount of time to provide information and abruptly departed for their occupation without concluding the interview. To effectively manage the respondents’ time and gather accurate information, it was necessary to conduct multiple meetings with them.

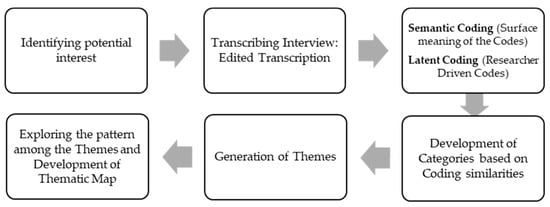

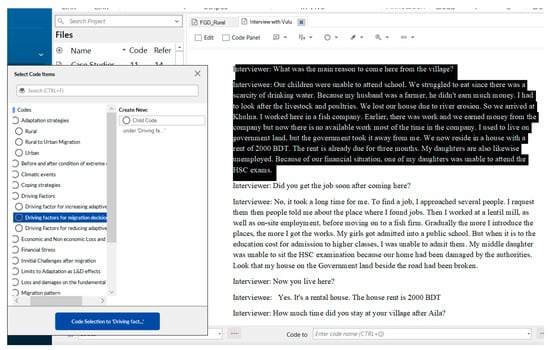

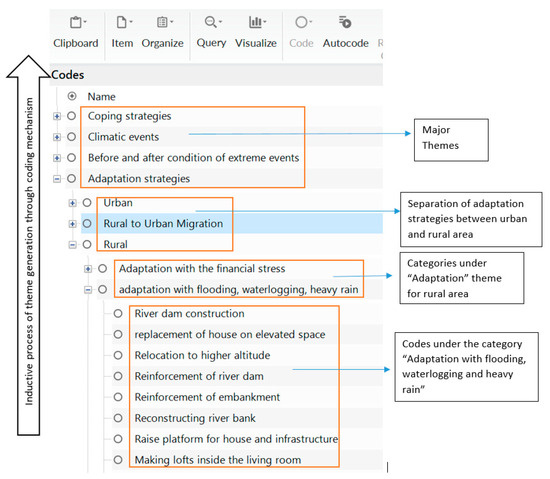

2.5. Data Analysis

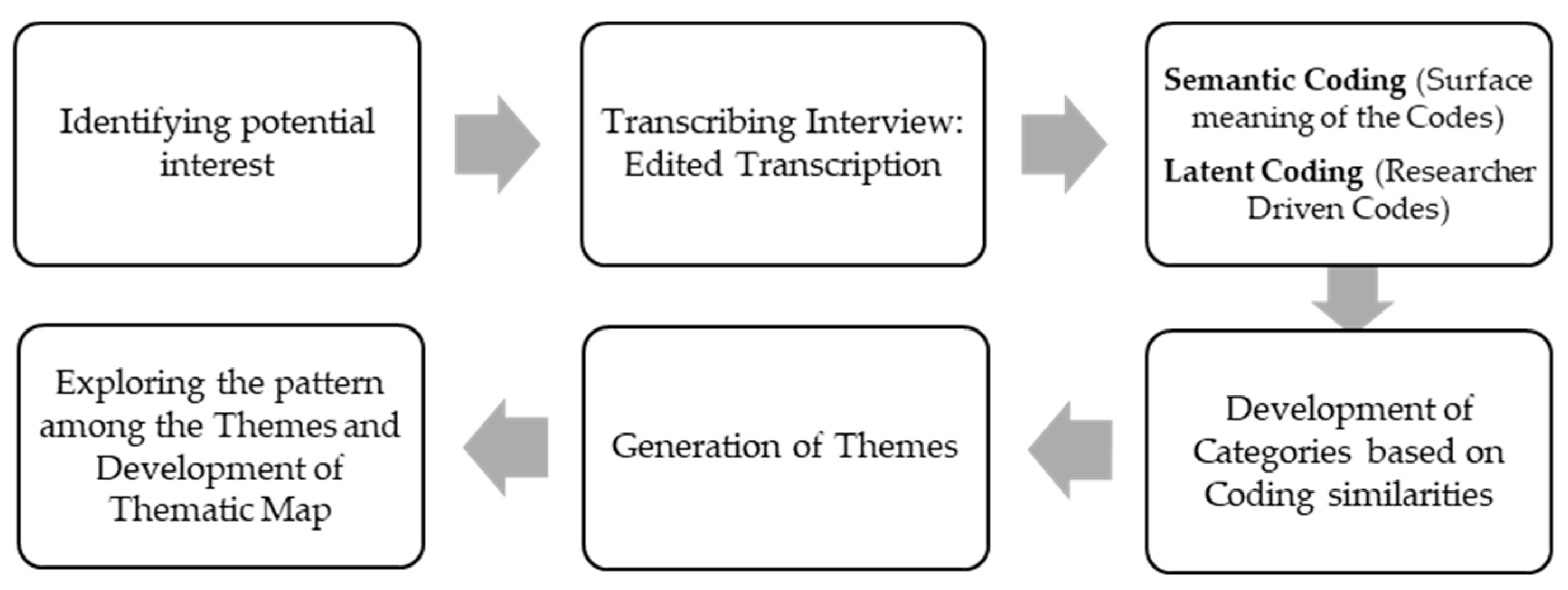

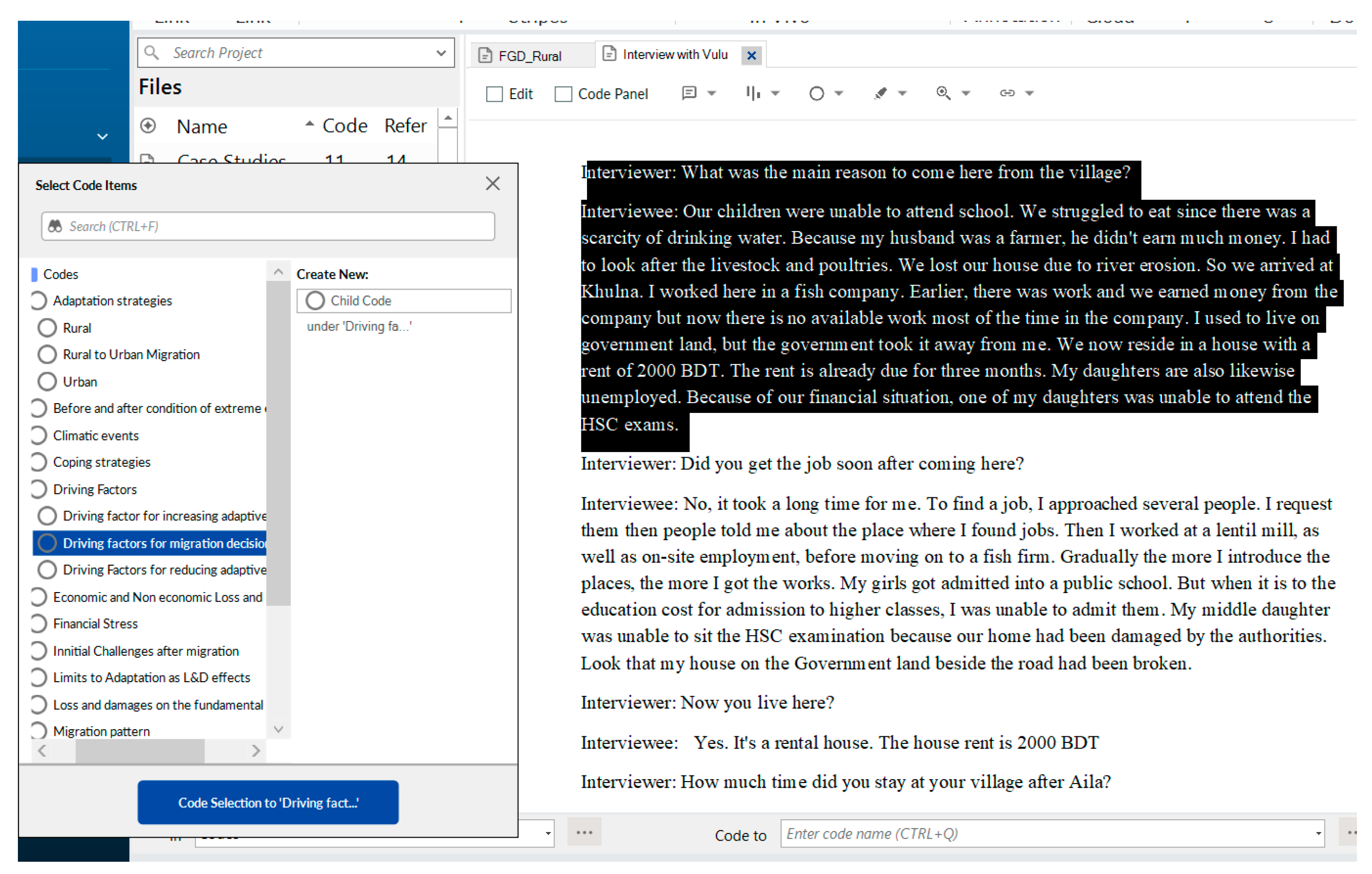

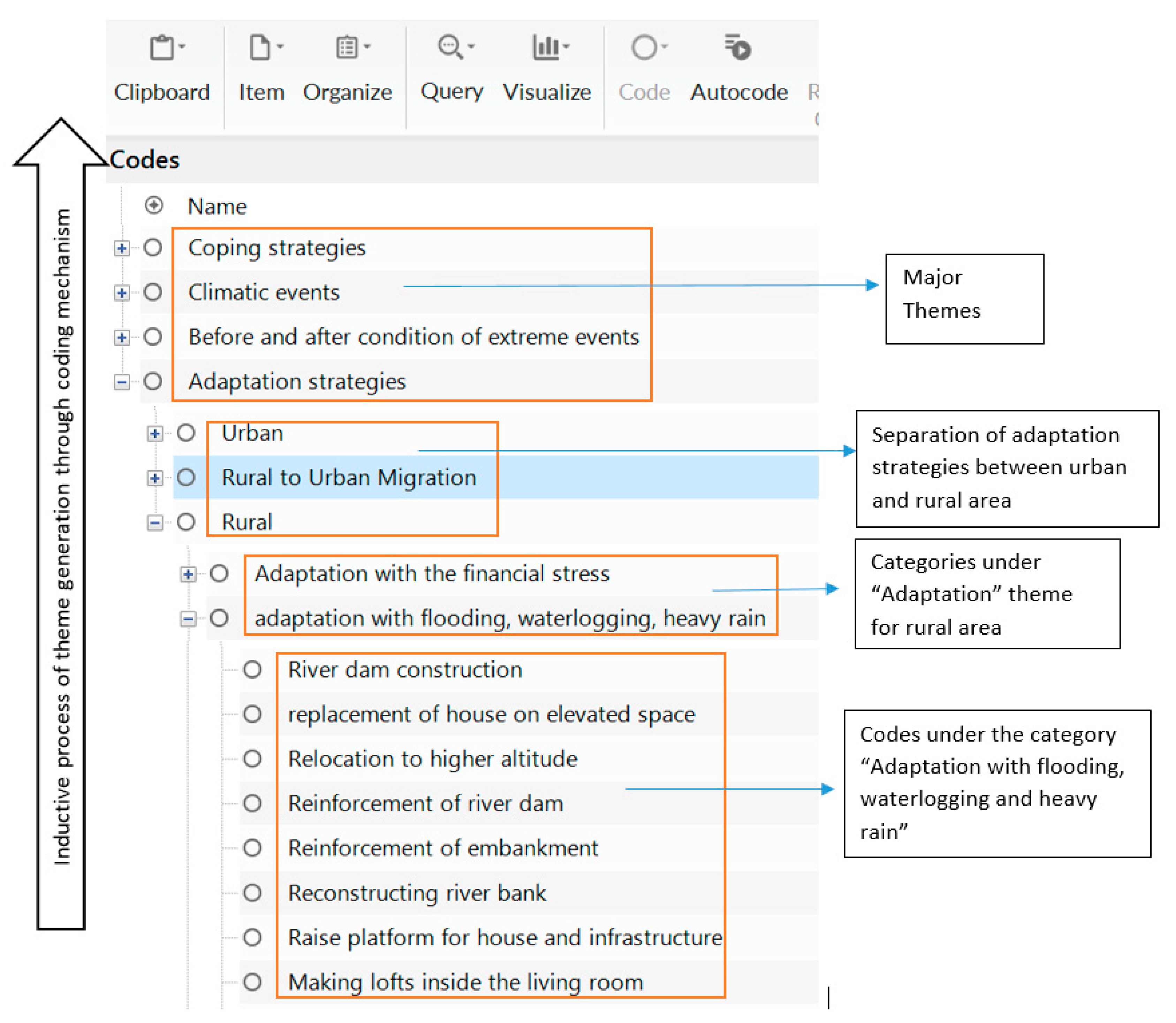

This study included thematic analysis approaches. Thematic analysis aims to identify noteworthy or intriguing patterns in the data, known as themes, which can be used to discuss the research or convey a certain point [75] (see Figure 5 for details). Prior to commencing the theme analysis, the researchers identified the potential segments of the interviews in order to gather the pertinent pieces of material that are of interest to the study. The interviews were transcribed from the audio recordings using the process of modified transcription. The purpose of this transcribing option is to streamline the documents by eliminating superfluous words or utterances. The study utilized NVivo 14 for coding purposes (see Figure 6 and Figure 7 for details). Prior to commencing the coding process, we initially identified our specific area of focus for this study and ensured that our coding remained consistent with the research objectives throughout the duration of the investigation. We produce revised transcriptions from every interview recording. We extract semantic codes by analyzing the literal meaning of the text. The purpose of these semantic codes is to produce latent codes, which are primarily researcher-driven codes that enhance the significance and relevance of the coding process to our research. Subsequently, we identified coding commonalities and proceeded to create clusters, which were then categorized and labelled. For instance, we have identified two distinct categories of driving variables (structural and structural) that impact the adaptive capacity of rural individuals. We have identified a grand total of six groups falling within the overarching theme of ‘adaptation strategies’. Subsequently, we examined the pattern and correlation between the topics in order to produce a thematic map.

Figure 5.

Steps of the coding process for this study.

Figure 6.

Text coding in NVivo 14: extracting insights from interview transcriptions.

Figure 7.

Hierarchy of coding process for this study developed by using NVivo 14.

3. Results

The result section examines the impact of extreme events and slow-onset events on hazards, vulnerability, and adaptation in coastal regions. It also explores the factors influencing adaptive capacity in rural regions and the limitations to adaptation due to loss and damage. Additionally, it investigates the drivers of migration decisions and patterns, as well as the initial challenges faced by affected individuals after migration in the context of coastal Bangladesh. Lastly, it considers the perspective of climate migrants in urban areas regarding loss and damage.

3.1. Climate Changes Hazards and Vulnerability in Coastal Region

3.1.1. Extreme Events Impact

The coastal regions in Bangladesh are exceedingly susceptible to the impacts of climate change, including both acute climate events and gradual changes over time. Our investigation revealed that the regions of Asasuni, Sutarkhali, Gabura, and Tala are susceptible to a range of severe and exceptional disasters. Vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, young children, and pregnant women, are especially susceptible to harm during hazardous events. This area is prone to regular occurrences of cyclones, river erosion, and floods. These dangers have detrimental impacts on agricultural output, human existence, and general welfare. The vulnerabilities are further exacerbated by insufficient preparedness, inadequate infrastructure, and restricted prospects for livelihood. River erosion is a recurring phenomenon that happens on a yearly basis, and in certain cases, it might occur twice within a year. It results in substantial harm to individuals’ means of living and housing and results in forced relocation. The region has already experienced the catastrophic cyclones, Sidr and Aila, in 2007 and 2009, respectively. Over the past several years, there has been an increase in the occurrence of cyclones, such as Bulbul in 2019 and Amphan in 2020. These cyclones have caused significant destruction and loss, affecting both individual households (including damage to structures and loss of animals) and the wider community (including disruptions to connection) (see Table 3 for details). The communities are facing increased hazards due to the inadequate quality and capacity of cyclone shelters, as well as the insufficient distance from and connectivity with these shelters. The frequent incidence of cyclones frequently results in extensive flooding, which in turn leads to the destruction of agricultural yields, hence causing a decline in the livelihoods of subsistence farmers and a reduction in agricultural output. Furthermore, the assistance previously offered by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government entities has been shown to be inadequate and insufficient.

Table 3.

Rapid-onset and extreme events effects on livelihood and wellbeing of coastal people.

3.1.2. Slow-Onset Events Impact

The local population is being impacted by a number of slow-onset events, including rising temperatures and increased salinity (see Table 4 for details). High temperatures have the potential to cause crop failures, decreased agricultural yields, and lower-quality agricultural output. The direct effects of rising temperatures also harm people who depend on fishing for a living, changing freshwater fish habitats and water temperatures. Extreme heat waves and temperatures can be harmful to one’s health, especially for older adults and young children who are more susceptible. In addition, the provision of clean drinking water is challenged by the saline water intrusion and the groundwater table’s decline, which has become a major problem for coastal settlements in recent decades. The community has experienced a number of negative consequences as a result of the area’s increasing salinity. The population of freshwater fish has decreased as a result, which has an effect on the livelihoods of individuals who depend on fishing. A major agricultural activity in the area, rice output has decreased as a result of the rising salinity, causing significant financial losses for the community. Furthermore, the population now has to rely on rainwater because the increased salinity has impacted the supply of drinking water. The length of the rainy season has decreased, nonetheless, from previous years. The present shorter rainy season, which used to run longer than two months from the month of ‘Jaishtha’ to the month of ‘Shrabon’, has a direct impact on the region’s agricultural and way of life.

Table 4.

Slow-onset events effects on livelihood and wellbeing of coastal people.

3.2. Loss and Damage Perspective in Rural Region

3.2.1. Adaptation and Coping Strategies Shaped by Loss and Damage

In the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh, where floods, cyclones, tidal surges, and river erosion have become frequent extreme weather events, and saline intrusion, rising temperatures, humidity, and sea level rise are becoming steady and slow-onset events, coastal people use various coping mechanisms in their daily lives to adjust to these weather events. Different adaptation and coping techniques were discovered through the qualitative study based on interviews as a course of action against the stress and shocks that occurred from the occurrences above. For instance, they build river dams and rebuild riverbank embankments as structural methods to address flooding and waterlogging at the community level. In addition, earth filling must be carried out on a regular basis at the household level in order to improve the elevation of the home and courtyard. They also set up preparations for disaster readiness, such as stockpiling water and dry food for the pre-disaster period. People are observed utilizing boats as a form of transportation during floods because the roads are frequently discovered to be unpaved and suffer significant damage as a result. Aside from this, people construct makeshift bamboo latrines, transport cattle to the closest high ground, and take up temporary residences aboard boats. People utilize techniques including collecting rainwater, setting up rainwater harvesting systems, filtering salty water, and using ponds and saltwater for sanitation to manage issues with salinity and water scarcity at the home level. People whose livelihoods are dependent on the environment and agriculture are most affected by salt and water scarcity, which affects their incomes. At the local level, a number of strategies are put into practice to address these issues, such as building embankments to withstand salinized water in cropland and agriculture, using gher farming, and raising crops that can withstand salinity. In order to adapt to cyclones and tidal surges, structural interventions are also seen, such as building river dams and strengthening embankments. At the domestic level, people take various actions to strengthen the buildings in their homes. In addition, during cyclones, they take shelter in the closest elementary school or shelter. When dwellings are found to be destroyed or damaged after a typhoon, people erect makeshift shelters on their own. To deal with the seasonal effects, livelihood stress, and other climate change events that directly affect their livelihoods and general well-being, different adaptation measures (as listed in Table 5) are used.

Table 5.

Adaptation and coping strategies for addressing L&D effects in the coastal region.

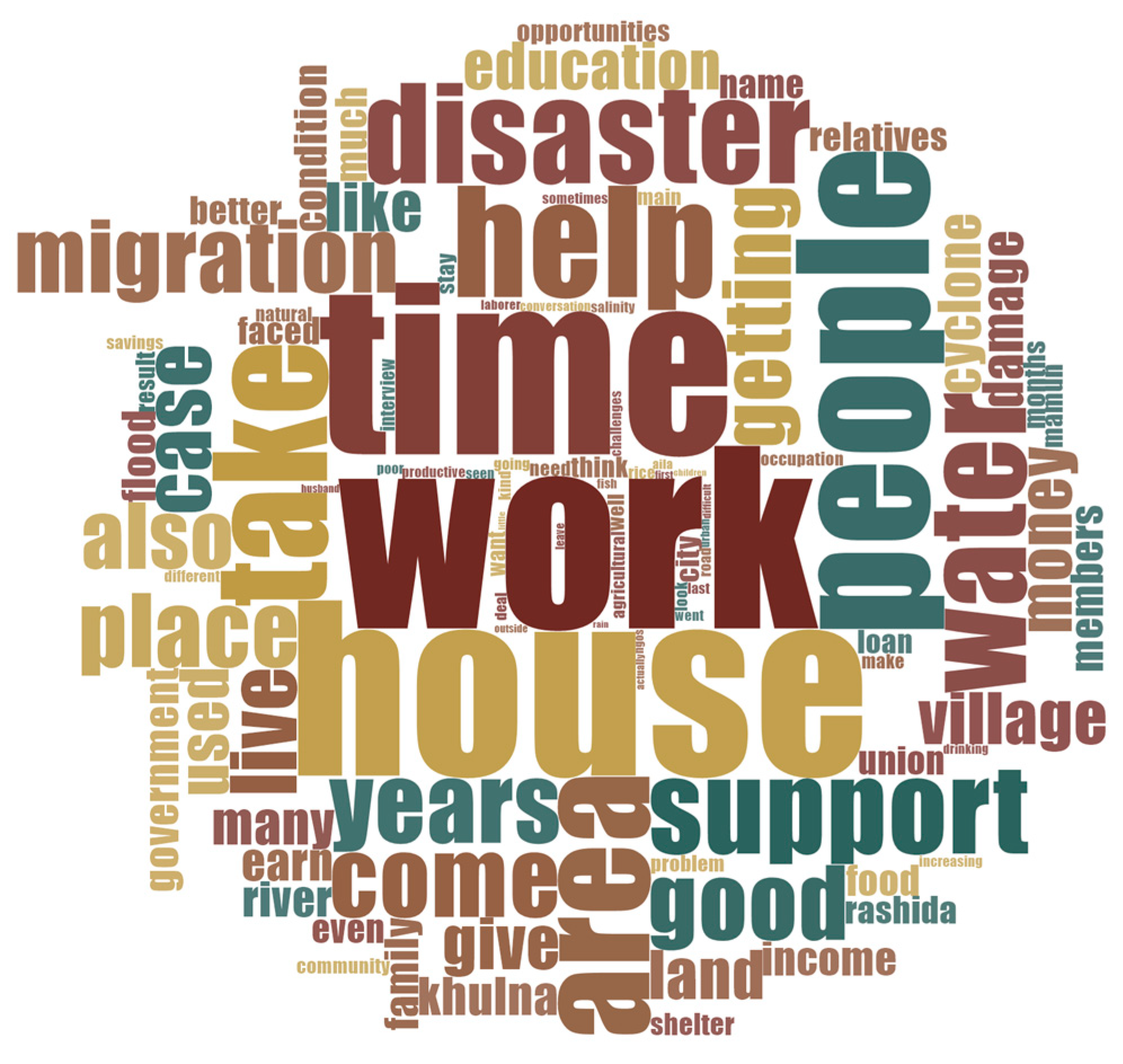

Farmers make up the bulk of the region’s population. In addition to farming, the locals operate brick kilns, go fishing, and drive vans. Most of the time, tidal surges, cyclones, and floods have a direct impact on people’s livelihoods. They encounter severe financial difficulties and a lack of employment options during the off-season or post-disaster period. It is at this point in their lives that they decide to move to the closest town or territorial center. It has been observed that migration is increasingly occurring as a means for people to cope with shocks and stress related to their livelihood. In this case, migration is a crucial adaptation tactic. Both catastrophic disaster occurrences and seasonality pose a risk to their means of subsistence. For instance, throughout the summer, they must spend longer hours in the field because of the intense heat and humidity. In this case, the amount of health risk they assume is disproportionate to the profit they make. Once more, the effects of the drought cause them to face a shortage of water during the summer. This results in poorer crop production, which directly impacts their means of subsistence. Because of this water limitation, they are forced to wait until even the rainy season to produce rice. Therefore, seasonal migration occurs in the quest for jobs throughout the summer months, primarily as day labor, to the closest upazila, district town, or regional or territorial hub. Figure 8 represents the words most frequently uttered by the interviewers concerning the adaptation and coping strategies to address the loss and damage.

Figure 8.

Word cloud generated from interviews.

3.2.2. Driving Factors behind the Adaptive Capacity in Rural Regions

Our research takes a look at coding and categorization processes to identify some structural and non-structural aspects that influence rural people’s ability to adjust to the coastal region (see Table 6 for details). Enhancing adaptive capacity requires both structural and non-structural components. It entails a mix of community involvement, education, capacity-building, and infrastructure development to foster resilience in the face of problems brought on by climate change. The presence and condition of river dams and embankments, the standard of roads and transit, and the design of housing all affect an infrastructure factor’s ability to respond to stress. Additional structural elements, including the standard and accessibility of cyclone shelters, the caliber of medical and educational facilities, and the availability of services, influence the ability of coastal populations to adapt. Lack of cyclone shelters might result in insufficient safety during severe weather, endangering lives. How fast and safely individuals can seek shelter during a disaster depends on how far away cyclone shelters are. Great distances may delay evacuation operations. When disasters strike, the movement of products and services, evacuation, and access to medical care are all hampered by inadequate road networks and transportation infrastructure. When severe weather strikes, poorly built homes are more likely to sustain damage and leave individuals without a place to stay. The risk of flooding during periods of high rainfall and storm surges is increased when one is too close to a river. When it comes to non-structural solutions, the majority of the codes have strong ties to social capital and social networks, which help to increase the adaptive ability to handle pressures brought on by climate change. To obtain the resources, knowledge, and help, one must rely heavily on social aspects, including communication, networking with institutions and other community members, and post-disaster support.

Table 6.

Drivers behind adaptive capacity of coastal people in rural region.

3.2.3. Limits to Adaptation as a Result of Loss and Damage

This study’s other main focus is on the limitations of adaptation brought on by loss and harm. This study uses coding to classify limits to adaptation brought on by damage and loss into two main categories: hard limits to adaptation and soft limits to adaptation (see Table 7 for details). A soft limit is reached when there are not enough adaptation options available right now or, when necessary, items are not readily available but can be handled in future adaptation techniques. Conversely, a hard limit results from unacceptable risk when no additional adaptive strategies are viable to mitigate the repercussions of loss and damage. More codes under soft constraints to adaptability were discovered in this study. People who live in coastal areas suffer soft boundaries when they lose their homes, their possessions, their means of subsistence, challenges in agriculture, adverse effects on food, health, and education, and infrastructure damage. According to the literature, intense and quick-onset events induce adaptation to approach its limit more quickly than delayed-onset occurrences. On the other hand, individuals mostly encounter harsh constraints when they are permanently uprooted from their shelter and lose their homes and homeland as a result of river erosion. They experience persistent post-disaster stress that has an impact on their way of life. They no longer have any chance to survive in their home country, which leads to forced migration. A respondent shared accounts of significant loss and damage caused by Cyclone Aila on 25 June 2023, in Gabura Union, Shyamnagar, Satkhira. This underscores the impactful and devastating consequences experienced by the community due to the cyclone’s effects.

Table 7.

Limits to adaptation as a result of loss and damage in coastal areas.

“We are highly susceptible to river erosion in our community. The dam in front of my house was damaged in the preceding cyclone, leading to extensive destruction. The impact was particularly severe during Cyclone Aila, causing widespread devastation to numerous houses. Tragically, many families experienced the heartbreaking loss of their children. My family and I were personally devastated as the floodwaters inundated our residence. We had to endure for approximately 15 days, relying solely on dry food and limited water. Additionally, both of my boats were destroyed by Cyclone Aila. The aftermath of Aila witnessed the destruction of countless lives in our area. As we continue to grapple with the aftermath, the process of rebuilding and recovering remains ongoing.”

3.3. Migration as an Adaptation in Coastal Bangladesh

3.3.1. Drivers behind Migration Decision and Pattern of Migration

Bangladesh’s coastal regions frequently see seasonal migration. Many individuals relocate for work during particular seasons; for example, many people work in brick kilns during the winter (see Table 8 for details). Most migrants only stay for a few months before going back to their own homes. Furthermore, some individuals sell their residences in order to relocate permanently to another district. The majority of people who sell their properties and relocate permanently to Khulna, Bagerhat, and other regions do so under duress since they have already lost their land and possessions to river erosion and are unable to return to their native country. In order to deal with the circumstances that followed the disaster and to pursue economic opportunities in the cities, many families moved there. In our circumstances, a large number of people from the study region move to other cities in search of work, mostly to the brickfields. As a result, seasonal migration is now commonplace in search of better job prospects. However, their financial limitations and emotional ties to their origin keep them from moving permanently, and occasionally they even encourage non-migration. Nonetheless, we classify our codes according to the commonalities between two categories of factors: “pull factors” and “push factors” that influence migration decisions (see Table 9 for details). The bulk of decisions are made as a result of the dearth of employment options in rural areas, particularly during the recovery period. Conversely, pull factors include the availability of jobs, improved living and working circumstances, access to services in urban regions, and better healthcare and educational options. Neighbors and relatives who have already relocated to metropolitan regions have an impact on potential climate migrants from rural areas.

Table 8.

Characterizing different pattern of migrations of coastal people.

Table 9.

Factors that trigger migration decision of coastal people.

“When faced with a shortage of employment opportunities, the residents of Pratapnagar devised a different strategy. The working population predominantly opts for seasonal migration to major cities in search of employment. In reality, individuals often engage in various roles as day laborers, brickfield workers, rice harvesters, and the like. What makes this seasonal migration particularly interesting is its prevalence during the winter season. While people used to migrate to different locations due to calamities in the past, today, they migrate regularly in pursuit of better job prospects. Owing to the harsh reality of persistent challenges in this area, many families have permanently relocated to other regions.” [Reflection from Kalu Mollik (pseudonym), 9 July 2023 at Praptanogor union, Asasuni, Satkhira]

3.3.2. Initial Difficulties Faced by Affected People after Migration

Climate migrants face difficulties in effectively managing their work in a new location. They encounter labor market rivalry, and their inability to possess the necessary skills or qualifications can impede their chances of obtaining stable and secure employment opportunities within their local area. Upon relocating to a different location, individuals frequently encounter an identity crisis and difficulties assimilating into the new community. They encounter adversity in their quest to generate a feeling of inclusion and frequently encounter prejudice or ostracism. Women migrants are mainly regarded as susceptible to many forms of violence, notably gender-based violence. Furthermore, there is a heightened likelihood of being taken advantage of and facing prejudice in their unfamiliar surroundings. In addition, relocation can result in the erosion of social support systems, including community networks and interpersonal connections. This might lead to feelings of seclusion and challenges in obtaining support and aid in an unfamiliar area. It has a substantial impact on their socioeconomic welfare and stability, as they frequently lose their livelihoods and sources of income. In addition to these factors, migrants may encounter disputes with the host community, which might worsen their challenges owing to the diversity in several aspects of social life or the perceived competition for employment and services. Nurjahan (pseudonym) reflected on her experiences during the post-Aila phase, sharing insights into the initial challenges she faced in the urban area after migrating. The interview took place on 20 June 2023, at Notun Bazar, Rupsha slum, Ward 22, KCC, Khulna.

“We were poor to the extent that we lacked even the basic necessity of clothing. I possessed only a single sharee, which was in a state of disrepair. The entirety of my children’s garments was depleted and tattered. I arrived here donning a tattered saree and a tattered blouse. Having endured significant hardship, we subsequently arrived at this location. Recalling past recollections can evoke negative emotions. Previously, we were accustomed to wearing tattered garments. During that period, we possessed only a single pitcher, a single pot, a single skillet, and four plates to sustain our household. Upon our arrival in Khulna, we brought along only these items. Aside from this, we incurred the loss of our remaining assets after the flood. The water caused our properties to be destroyed. A young woman, employed as a domestic servant, graciously offered us accommodation in her residence for a little period.”

3.4. Loss and Damage Perspective of Climate Migrants in Urban Areas

Climate migrants frequently encounter the effects of climate change in metropolitan areas, such as reduced employment prospects during rainy seasons, destruction of physical assets during high tides and floods, and heightened health hazards during flooding (see Table 10 for details). Nevertheless, they utilize diverse adaptive mechanisms to deal with the problems they encounter effectively (see Table 11 for details). To cope with seasonal variations, they employ ripped blankets during winter and modify their dietary habits, limiting food intake during the rainy season due to financial constraints. To manage hot and humid temperatures, it is necessary to utilize shared energy lines and find respite outside in the event of a power outage. Due to high tides and flooding, it is necessary to relocate furniture, temporarily reside on roads, or rent alternative lodging. Climate migrants also depend on social networks and contacts with neighbors to secure employment and obtain institutional support. Urban job possibilities, access to services, strong social networks, and skill development programs are factors that contribute to their adaptive capacity. However, their ability to adapt is weakened by factors such as job instability, financial difficulties, uncertainty about their housing situation, deficiencies in institutional support, lack of affordable service facilities, climate-related risks, and unfavorable environmental conditions in urban slums (see Table 12 for details). It is essential to tackle these intricacies in order to improve the ability of climate migrants in urban regions to withstand challenges and decrease their susceptibilities.

Table 10.

Loss and damage effect experience by the climate migrants in the urban area.

Table 11.

Adaptation and coping strategies to address loss and damage effect in the experience by the climate migrants in the urban area.

Table 12.

Drivers behind the adaptive capacity to address loss and damage effect experienced by the climate migrants in the urban area.

4. Discussion

In general, rural people experience several challenges in their livelihood and well-being as a result of climate-induced disasters and consequences. Rural populations commonly face several hardships in their livelihoods and overall welfare due to climate-induced disasters and their repercussions. The individuals residing in the coastal region of Bangladesh mostly encounter two types of adaptation constraints, namely soft limits and hard limits, due to climate-induced disasters and calamities. Climate-induced events have a significant impact on the livelihood, well-being, and assets of coastal communities. Seasonality also exerts a substantial impact on their livelihood and well-being. They experience a dearth of employment due to the impact of seasonal factors on their means of making a living. To address this, they employ a diverse array of adaptive mechanisms. Rural households endure enduring consequences on their means of living and overall welfare in the aftermath of severe weather occurrences. The significant consequences of loss and destruction frequently compel individuals to make a decision to relocate. Hence, the factors of seasonality and post-disaster problems seem to play a crucial role in influencing migratory choices.

This study discovered that individuals residing in coastal regions encounter vulnerabilities related to climate change that directly affect their means of subsistence. Migration emerges as a crucial strategy for these individuals to both cope with and adapt to the consequences of climate change. For example, individuals residing in the Sutarkhali Union primarily participate in agricultural endeavors during the rainy season, while the remainder of the year is dedicated to non-agricultural pursuits. Additionally, they engage in seasonal migration to urban areas in search of employment possibilities. The agricultural industry is susceptible to heightened salinity in the soil, scarcity of freshwater, and rising temperatures. Rural areas engage in various non-agricultural activities such as mud cutting, motorbike riding, van transportation, and fishing. Furthermore, residents in coastal regions engage in the cultivation of crops and the rearing of livestock, which serve as sources of revenue and are occasionally involved in the cultivation of plants. Even though, these non-agricultural endeavors are dependent on the accessibility of resources and favorable conditions, such as abundant water for fishing and cultivating plants to feed cattle, as well as well-suited transportation routes. Nevertheless, the limited availability of clean water, high levels of salt in the soil, insufficient water supply, and extreme weather conditions have adverse impacts on these sources of income as well. These income-generating activities need to be increased for the coastal residents to support their families. In order to adjust to this situation, numerous residents in coastal areas choose seasonal migration in order to pursue more lucrative employment prospects in urban areas. This study examines the manner in which individuals afflicted by certain circumstances utilize migration as a means of adapting to their situation (see Figure 9). Migration often occurs when the capacity reaches its maximum in most instances. The existing employment and financial prospects prove inadequate in mitigating the loss and damage caused by climate catastrophes, thereby prompting the decision to migrate. For instance, the pressures on the means of subsistence experienced by coastal communities due to seasonal variations and gradual changes in climate typically impose constraints on the ability of these communities to adapt. Individuals opted for alternative employment and temporarily relocated to oversee their means of subsistence for a specific duration. Therefore, individuals of this nature possess the capability to restore these specific boundaries of adjustment by means of seasonal migration. Furthermore, the gradual occurrence of events and their seasonal nature not only impact individuals’ means of making a living but also have an adverse effect on their overall welfare, including the availability of food, access to healthcare, and educational opportunities in rural regions. For instance, the immediate impact of rising salinity and dwindling freshwater availability adversely affects the well-being and food stability of coastal populations. Furthermore, these occurrences contribute to the decline in income from the existing livelihood opportunities in rural areas. In response to the financial strain, there was a rise in the number of youngsters dropping out of school, and they were compelled to engage in child labor in order to augment their family’s income in the coastal area.

Figure 9.

Exploring patterns in loss and damage, migration decisions, adaptation, and post-migration challenges.

In addition to the typical consequences of gradual events, the inhabitants of coastal areas in Bangladesh also encounter infrequent but highly intense extreme climate events, including cyclones, floods, and river erosion (see Figure 9). This study discovered that this particular type of experience produces both flexible and rigid boundaries of adaptation. The primary factors contributing to the imposition of strict limitations are the significant impact of the two giant cyclones, Aila and Sidr, which compelled individuals to abandon their villages and permanently relocate to urban areas. The rural coastal region saw catastrophic events like cyclones Aila and Sidr, resulting in substantial destruction, mainly from flooding and erosion. After the disaster, immediate assistance was offered by both governmental and non-governmental organizations, which included providing shelter and food to the impacted communities. Based on the contemplation of urban climate migrants, most of them experienced irreversible loss and harm that cannot be restored, ultimately reaching insurmountable thresholds that compelled them to migrate to Khulna permanently. For example, as per the accounts of urban climate migrants, they relocated to the city in 2009 following the destruction of their house by Cyclone Aila. Their land and properties were entirely lost due to river erosion, compelling them to relocate to the city permanently. The populace’s recognition of the enhanced economic opportunities in urban areas was an additional catalyst for their permanent relocation. Prior to permanently moving to urban areas, numerous migrants initially engaged in seasonal travel, sometimes motivated by observing the enhanced living conditions of their relatives.

In summary, the study revealed that rural inhabitants in coastal areas typically engage in two types of migration: seasonal and permanent (see Figure 9). They often engage in seasonal and temporary movement to adapt to the impacts of seasonality on their livelihood. Alternatively, people opt for permanent migration as a means of adapting to adverse circumstances, often as a response to significant loss and damage caused by extreme climate events such as river erosion, cyclones, and floods. Permanent migration is often involuntary, occurring when individuals have no other viable means of survival in their area of origin. Individuals who are impacted by river erosion experience a loss of their identity and sense of belonging, leading them to relocate to urban regions permanently. A significant discovery from the study is that individuals who are affected resort to seasonal movement as an adaptive measure to mitigate the constraints imposed by seasonal impacts. For instance, as a result of inadequate income-generating prospects during the non-farming season in rural areas, they opted for temporary migration. The non-agricultural seasons are particularly susceptible to gradual events such as temperature and salinity increases, which are caused by insufficient rainfall and scarcity of fresh water. Conversely, permanent migration decisions are made as a means of adapting to extreme climate occurrences such as cyclones and river erosion when they reach their maximum capacity. In addition to these factors, social networks also exert a significant influence on the decision to migrate. Many individuals living in rural areas choose to permanently relocate due to the presence of extensive social connections with their relatives in metropolitan areas and neighbors in rural areas. This social network also facilitates users in gaining knowledge about superior employment prospects and improved service amenities in urban areas, hence motivating individuals to undertake permanent relocation. Nevertheless, some individuals who are impacted do not embrace migration as a viable approach for adaptation. Several factors serve as catalysts for non-migration. The profound emotional connection to their native land and the strong sense of belonging to their ancestral homeland serve as powerful incentives for people to refrain from migrating under any circumstances. Moreover, the financial burden of residing in metropolitan regions is an additional worry for individuals who do not migrate.

Our findings also investigate the migration strategies that inadequately manage the adverse impacts of climate migrants. The nature of informal settlements in metropolitan settings might exacerbate the risks to the livelihood and well-being of migrants. Following their migration, the migrants encounter numerous challenges in securing employment. They are only able to recuperate if they fully secure stable employment in urban regions. A need for more literacy or the necessary skills exacerbates this first post-migration issue. These migrants do not come from a high socio-economic background. Frequently, they experience conflicts with the host communities. Social networks play a significant role in job acquisition. The characteristics and amenities provided by the slum and squatter communities in metropolitan settings, along with the uncertainty of tenure, increased expense of living, and the risk of eviction, once again demonstrate the constraints on adaptation in urban regions.

This article proposes several strategies to mitigate the constraints faced by coastal communities and minimize the likelihood of migration. The study proposes the implementation of income-generating options during non-farming seasons in order to mitigate the seasonal impact on livelihoods in rural Bangladesh. This can be achieved through the provision of government and non-government services, such as vocational training and skill development programs, targeted towards the rural population. To mitigate salinity, we propose promoting the cultivation of crops that are resilient to climate conditions and tolerant to high salt levels. In addition to this, it is imperative for the local authority to assume responsibility for ensuring a minimum standard of education for all individuals and to prioritize the improvement of educational and healthcare infrastructure. This study identifies several structural and non-structural components that directly contribute to enhancing the adaptive capacity of individuals in addressing loss and damage. For instance, in terms of the structure factor, the government should enhance transportation systems, improve road infrastructure, establish disability-inclusive cyclone shelters, and develop a more efficient transportation network. Additionally, it is essential to integrate health centers, schools, markets, and cyclone shelters into this network to ensure unimpeded movement during emergencies. If there are non-structural factors involved, the local authority, government, and non-government organizations need to enhance their services and support during the pre-disaster, disaster, and post-disaster periods. They should establish a more robust network with the affected individuals to enhance their social capital. Additionally, there should be a focus on improving education for both genders and empowering women in the decision-making process. Implementing both structural and non-structural interventions can enhance the adaptive ability of coastal communities, effectively addressing both flexible and rigid constraints and reducing the likelihood of migration. This study also provides a method for enhancing the well-being of urban climate migrants. It promotes the creation of a higher-quality environment in slum settlements and motivates the government to establish a proactive strategy for relocating settlement facilities after a disaster. This plan will assist migrants in coping with the stress and limitations of adapting to the post-disaster situation. This study proposes identifying the specific locations and sectors where seasonal migrants typically seek employment in order to determine the most common destinations and industries for earning income. It is recommended that the working conditions in these sectors be made accessible and free from obstacles in order to reduce the likelihood of exploitation and hardships for these laborers.

5. Conclusions

This study seeks to investigate the loss and damage experienced by coastal regions from the perspective of adaptation. Additionally, it attempts to examine the adaptation mechanisms employed when migration plays a significant role in addressing loss and damage. This study assesses the occurrence of Loss and Damage due to constraints on adaption perspectives. The Khulna and Satkhira districts, situated in the Khulna division of Bangladesh, were the locations chosen for conducting twenty-four in-depth interviews and one focus group discussion (FGD) with individuals affected by climate-induced disasters in rural areas. Additionally, seven interviews were conducted with climate migrants residing in informal settlements within the Khulna City Corporation. The criteria and snowball procedures are utilized to identify possible interview participants. This study utilizes theme analysis to analyze textual data obtained from transcribed interviews, employing the software NVivo 14.

In the coding process, we follow a sequential approach that involves semantic coding, latent coding, categorizing, pattern exploration, and theme development. This approach is aligned with the research objectives. The study demonstrates that individuals who are affected by climate change utilize seasonal and temporary movement as a strategic response to deal with the slow effects of climate change, such as increasing temperatures and salinity in rural areas. However, their ability to adapt reaches its limitations. On the other hand, individuals choose permanent migration when they reach the maximum level of adaptation due to severe climate events such as cyclones and river erosion, which force them to relocate. The social network plays a vital role in this context, as individuals often depend on the information provided by urban relatives and rural neighbors to make informed decisions on migration. Nevertheless, a portion of the impacted population opts not to migrate, instead opting to stay in rural regions as a result of sentimental connections to their local communities and a strong allegiance to their inherited territories. They suggest that the exorbitant metropolitan cost of living renders non-migration a more feasible alternative for mitigating the repercussions of climate-induced loss and harm. The study’s findings can assist policymakers in prioritizing the development of migration policies aimed at mitigating the adverse impacts experienced by the coastal population of Bangladesh. Additionally, it can aid in making decisions to tackle the issues encountered by climate migrants in both urban and rural regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology S.N., T.I.H., M.Z.H., K.R.R. and N.M.H.-M.; data collection, interview transcription, and data analysis S.N., T.I.H., T.R., S.I., S.B.N., S.T.I., M.M.H., M.Z.H., K.R.R. and N.M.H.-M.; writing draft S.N., T.I.H., T.R., S.I., S.B.N., S.T.I., M.M.H., M.Z.H., K.R.R. and N.M.H.-M.; final editing S.N., T.I.H., T.R., S.I., S.B.N., S.T.I., M.M.H., M.Z.H., K.R.R. and N.M.H.-M.; supervision, M.Z.H., K.R.R. and N.M.H.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Clearance Committee of Khulna University (Reference Number: KUECC-2024-01-04).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were comprehensively briefed on the assurance of their anonymity, the purpose behind the research, and the potential utilization of the data in case of publication. As is standard in all research involving human subjects, ethical approval from the relevant ethics committee was secured.

Data Availability Statement

The study’s data can be obtained upon request from the the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Surminski, S.; Lopez, A. Concept of loss and damage of climate change—A new challenge for climate decision-making? A climate science perspective. Clim. Dev. 2015, 7, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Climate Change. COP 19. Available online: https://unfccc.int/event/cop-19 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- United Nations Climate Change. COP 26. Available online: https://unfccc.int/event/cop-26 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- United Nations Climate Change. COP 27. Available online: https://unfccc.int/event/cop-27 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- McNamara, K.E.; Jackson, G. Loss and damage: A review of the literature and directions for future research. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.A.; Heyward, C. Compensating for Climate Change Loss and Damage. Political Stud. 2017, 65, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Pelling, M. Loss and damage: An opportunity for transformation? Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, P.; Martínez Blanco, A. A human rights-based approach to loss and damage under the climate change regime. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R.U.; Walter, J. The greenhouse effect: Damages, costs and abatement. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1991, 1, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.; James, R.A.; Jones, R.G.; Young, H.R.; Otto, F.E.L. A typology of loss and damage perspectives. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.R.; Dokken, D.J.; Mach, K.J.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Bilir, T.E.; Chatterjee, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Estrada, Y.O.; Genova, R.C.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC, 2014: Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Magnan, A.K.; Schipper EL, F.; Duvat VK, E. Frontiers in Climate Change Adaptation Science: Advancing Guidelines to Design Adaptation Pathways. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 2020, 6, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechler, R.; Singh, C.; Ebi, K.; Djalante, R.; Thomas, A.; James, R.; Tschakert, P.; Wewerinke-Singh, M.; Schinko, T.; Ley, D.; et al. Loss and Damage and limits to adaptation: Recent IPCC insights and implications for climate science and policy. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Dessai, S.; Goulden, M.; Hulme, M.; Lorenzoni, I.; Nelson, D.R.; Naess, L.O.; Wolf, J.; Wreford, A. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim. Chang. 2009, 93, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, K.; Berkhout, F.; Preston, B.L.; Klein RJ, T.; Midgley, G.; Shaw, M.R. Limits to adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Nalau, J. (Eds.) Limits to Climate Change Adaptation; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdapolrak, P.; Borderon, M.; Sterly, H. The limits of migration as adaptation. A conceptual approach towards the role of immobility, disconnectedness and simultaneous exposure in translocal livelihoods systems. Clim. Dev. 2023, 16, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, G. Climate migration as an adaption strategy: De-securitizing climate-induced migration or making the unruly governable? Crit. Stud. Secur. 2014, 2, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, E. Research on climate change and migration where are we and where are we going? Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemenne, F.; Blocher, J. How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeman, R.; Wrathall, D.; Gilmore, E.; Thornton, P.; Adams, H.; Gemenne, F. Conceptual framing to link climate risk assessments and climate-migration scholarship. Clim. Chang. 2021, 165, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.M.P.; Ilina, I.N. Climate change and migration impacts on cities: Lessons from Bangladesh. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, K.; Bergmann, J.; Blocher, J.; Upadhyay, H.; Hoffmann, R. Migration as Adaptation? Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederkehr, C.; Beckmann, M.; Hermans, K. Environmental change, adaptation strategies and the relevance of migration in Sub-Saharan drylands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felli, R. Managing Climate Insecurity by Ensuring Continuous Capital Accumulation: “Climate Refugees” and “Climate Migrants.”. New Political Econ. 2013, 18, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010: Decision 1/CP.16 The Cancun Agreements. 2010. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 19 December 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_73_195.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Bilsborrow, R. Rural Poverty, Migration, and the Environment in Developing Countries: Three Case Studies; Policy Research Working Paper Series; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McLeman, R.; Smit, B. Migration as an Adaptation to Climate Change. Clim. Chang. 2006, 76, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Bennett SR, G.; Thomas, S.M.; Beddington, J.R. Migration as adaptation. Nature 2011, 478, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeman, R. Conclusion: Migration as Adaptation: Conceptual Origins, Recent Developments, and Future Directions. In Migration, Risk Management and Climate Change: Evidence and Policy Responses; Milan, A., Schraven, B., Warner, K., Cascone, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, K.; Sakdapolrak, P. How do social practices shape policy? Analysing the field of ‘migration as adaptation’ with Bourdieu’s ‘Theory of Practice’. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.; Afifi, T. Where the rain falls: Evidence from 8 countries on how vulnerable households use migration to manage the risk of rainfall variability and food insecurity. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.; Crevello, S.; Chea, C.; Jarihani, B. When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change? Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]