Abstract

Space and satellite-based systems have had a monumental impact on providing greater interconnectivity across the world. The usage of space and satellite-based systems has increased the ability to access internet resources even in remote areas. Unfortunately, these systems are subject to malicious and multi-faceted cyberattacks. Therefore, proper threat detection systems must be implemented to safeguard these space systems. In our study, we present our novel intrusion detection framework, SpIDER, a space satellite intrusion detection system using explainable reinforcement learning. SpIDER leverages the benefits offered by reinforcement learning and Shapley additive global explanations to improve both the performance and explainability of space-based intrusion detection. We compare our SpIDER framework to several popular machine learning algorithms using the STIN and NSL-KDD datasets. We observe that our SpIDER framework achieves high performance, with accuracy and G-Mean above 99.98% on the STIN satellite dataset. SpIDER also outperforms other machine learning models on the NSL-KDD local area network dataset, achieving accuracy of 76.71% and a G-Mean of 80.49%. These results demonstrate that our SpIDER explainable deep reinforcement learning framework can perform as well or better than supervised machine learning models on both satellite-style and local area network data.

1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of space satellite communications has allowed for an increase in the ubiquity of the internet. Space technologies have enabled advances in position, navigation, and timing [1], weather and meteorological sensing [2], and more recently, global internet connectivity [3]. These applications typically require close coordination between space-based satellites and terrestrial ground stations. The adoption of satellite technologies has coincided with the inception of the information age. As such, satellite technologies have allowed internet connectivity worldwide to enable greater information transfer. Unfortunately, with the growth of the information age and the internet, these satellite systems have also been subjected to cyberattacks. Both ground stations and space-based systems have been affected by networking attacks which affect internet connectivity globally.

Network intrusion detection systems provide a method to detect and respond to cyber threats. Network intrusion detection systems complement existing cybersecurity controls such as firewalls and router access control lists (ACLs). Firewalls and ACLs commonly operate by determining whether to permit or deny network traffic using a predefined set of rules. As opposed to firewalls and ACLs, which often rely on a static ruleset, network intrusion detection systems have the unique ability to utilize an intelligent algorithm to determine whether to permit or deny access to a computer network.

Many of these intrusion detection systems apply machine learning algorithms to assess whether network traffic is benign or malicious. For intrusion detection systems, machine learning algorithms can be trained on traffic with existing signatures akin to supervised learning or detect anomalies from a baseline akin to unsupervised learning. While both supervised and unsupervised learning have benefits for intrusion detection, the reinforcement learning aspect of machine learning has not been heavily applied in intrusion detection systems. Furthermore, we find little application of reinforcement learning for space satellite intrusion detection.

From a modeling perspective, intrusion detection in satellite and terrestrial networks can be viewed naturally as a sequential decision problem. As network flows or packets arrive over time, the intrusion detection system must repeatedly decide how to classify each observation and can adapt its behavior as the environment changes. Reinforcement learning is specifically designed for this setting, where an intelligent agent interacts with an environment and learns a policy that maximizes long-term reward. In the context of intrusion detection, rewards can be tied to correct detections and penalize false alarms, providing a flexible way to encode operational costs and benefits. However, despite this natural fit, reinforcement learning has rarely been explored for satellite-focused intrusion detection.

A second challenge concerns explainability. Deep learning and other nonparametric models often are described as “black boxes”. Prior methods to provide greater explainability into a model’s classification include SHAP [4] and LIME [5]. These approaches are widely used but primarily provide local explanations for individual predictions. In contrast, operators and system designers for space systems often need global insight into which features consistently drive model performance. These approaches can allow operators to prioritize telemetry fields or design simpler rule-based fallbacks. Shapley Additive Global Importance (SAGE) [6] directly addresses this need by quantifying each feature’s overall contribution to model performance.

Thus, our work aims to further the current field of space-based intrusion detection through the utilization of reinforcement learning algorithms together with global explainability. We present our novel framework, SpIDER: Space satellite Intrusion Detection using Explainable Reinforcement learning. Our work furthers the satellite-based intrusion detection literature through the following contributions:

- We examine the application of space satellite intrusion detection systems by analyzing both space traffic and terrestrial ground station traffic alongside ordinary local area network internet traffic using the STIN and NSL-KDD datasets. This allows us to directly compare satellite-style and traditional LAN intrusion detection performance within a unified framework.

- We implement the popular deep Q-network (DQN) reinforcement learning algorithm to detect cyberattacks on space satellite traffic and classical LAN traffic. We compare our DQN-based SpIDER framework against several well-known machine learning algorithms (support vector machines, naive Bayes, and multilayer perceptron) to assess where reinforcement learning is competitive or advantageous.

- We apply Shapley Additive Global Explanations (SAGE) to assess which dataset features meaningfully contributed to the predictions of our reinforcement learning model used in our framework. This global analysis provides insight into which network features are most important for detecting attacks in satellite versus terrestrial environments and can inform future feature engineering and telemetry design.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to jointly apply a DQN-based reinforcement learning agent and SAGE-based global explainability to the Satellite–Terrestrial Integrated Network (STIN) dataset and to systematically compare this reinforcement learning approach to conventional machine learning baselines across both satellite-style and NSL-KDD local area network traffic. We position our work on SpIDER as a feasibility and benchmarking study that clarifies where a reinforcement learning-based explainable framework can perform as well as or better than traditional approaches.

We discuss our novel SpIDER framework through the various sections in our paper: Section 2 provides related literature for terrestrial and space-based cybersecurity; Section 3 provides our novel framework and our benchmark machine learning models; Section 4 covers results; finally, Section 5 discusses these findings and Section 6 concludes the work.

2. Literature Review

Our work intersects two topics, namely, space anomaly detection using machine learning and reinforcement learning applications for networking cybersecurity. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of our work, we divide our literature review into two primary sections.

2.1. Machine Learning Applications for Space Security and Anomaly Detection

As a direct consequence of utilizing satellite technologies for communications and internet connectivity, these systems are now subject to cyberattacks. Thus, intrusion detection mechanisms must now be utilized to provide for greater security of these satellite communication systems. In the work presented in [7], the authors employed a deep learning-based intrusion detection system for smart satellite networks using recurrent neural networks such as long-short term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent unit (GRU) networks. They observed low false negative rates from their models, but high false positive. Federated learning, a novel paradigm for machine learning emphasizing data privacy initially proposed in [8], also benefits in applications for satellite intrusion detection. In [9], a deep federated learning intrusion detection model was applied for satellite environments and obtained high accuracy while maintaining data privacy. Researchers in [10] also applied a federated learning threat detection algorithm for both satellite and terrestrial systems. Their federated learning model utilized less CPU processing while detecting more attacks compared to traditional intrusion detection systems.

For satellite anomaly detection, Ref. [11] presented two unsupervised methods, namely, a long-short term memory (LSTM) network in conjunction with an isolation forest-based model to detect anomalies in spaceflight. Their unsupervised methods were effective at classifying anomalies even in instances where data were not evenly distributed in time. Additional applications of LSTM networks were presented in [12], here with respect to frequency spectrum data for satellite maneuvers and communications. In [13], the authors applied an LSTM with feature attention in order to detect satellite anomalies in telemetry data. While these models provide promising methods to detect these anomalies, especially with respect to satellite system cyberattacks, there has been a conspicuous absence of applying reinforcement learning algorithms for satellite intrusion detection. Applying reinforcement learning could provide improvements in performance compared to current existing algorithms.

2.2. Intrusion Detection Using Reinforcement Learning Approaches

Several popular network intrusion detection algorithms commonly apply machine learning to determine whether to permit or deny network traffic [14,15]. However, the application of reinforcement learning is still a relatively recent advancement for cyber intrusion detection. Previous works applying reinforcement learning include the algorithms analyzed in [16], where the researchers applied deep reinforcement learning models such as deep Q-network, policy gradient, and actor–critic algorithms on the NSL-KDD [17] and AWID [18] datasets. Similarly, an adversarial environment reinforcement learning agent was added in [19]; adding an adversarial deep Q-network improved the performance of the classifier deep Q-network for intrusion detection. The researchers in [20] further applied the adversarial environment, instead using a deep deterministic policy gradient on IoT telemetry data. Multiple intrusion detection system agents with deep Q-networks proved robust against adversarial attacks in [21], which presented adaptive, robust, and applied ensemble methods for intrusion detection. However, while the aforementioned works all considered applying intrusion detection in cybersecurity contexts, space satellite systems and satellite communications pose unique challenges such as long propagation delays, constrained on-board computation, and non-traditional traffic patterns that are not captured by standard LAN datasets. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first work to jointly apply a DQN-based reinforcement learning agent and SAGE-based global explainability to the Satellite–Terrestrial Integrated Network (STIN) dataset. Prior deep reinforcement learning intrusion detection studies have focused primarily on terrestrial datasets such as NSL-KDD and AWID, and have not considered satellite-style traffic or combined deep RL with model explainability. Likewise, existing satellite security and anomaly detection works have primarily relied on supervised or unsupervised deep learning; when explainability has been considered, they have emphasized local explanation methods such as SHAP or LIME [7,11].

Thus, our work aims to address these issues posed by detecting cyber threats in a space satellite system. Specifically, we leverage the advantages of reinforcement learning, that is, an intelligent agent interacting with a distinct environment, in order to improve our intrusion detection performance. Additionally, most works (excepting [11]) do not provide any explainability for their models; furthermore, Ref. [11] only applied SHAP [4] and LIME [5] for explainability. We apply a more recent method, Shapley Additive Global Importance (SAGE) [6], to determine feature importance. SAGE considers global feature importance and assesses each feature’s contribution to the performance of the model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Datasets

We apply two datasets in our study. In order to determine our framework’s effectiveness at classifying threats for space satellite communications, we apply our models using the STIN dataset as proposed in [10]. Additionally, to compare our framework with other machine learning-based intrusion detection systems, we apply the NSL-KDD dataset as proposed in [17].

3.1.1. STIN Dataset

The Satellite–Terrestrial Integrated Network (STIN) dataset was initially proposed by the researchers in [10] after observing a lack of datasets in satellite communication environments, especially with respect to intrusion detection. The STIN dataset is divided into a satellite dataset and a terrestrial dataset. There are 15 features with over 150,000 observations per dataset. In order to simulate satellite environments, the researchers applied Kernel-based Virtual Machines (KVMs) [22] to create two primary systems: a terrestrial network and a corresponding satellite network. The satellite network emulates satellite systems residing in low-earth orbits (LEO) using delay-tolerant networking via the interplanetary overlay network [23,24]. The terrestrial network is implemented using the common TCP/IP protocol stack, which is common in most terrestrial networks.

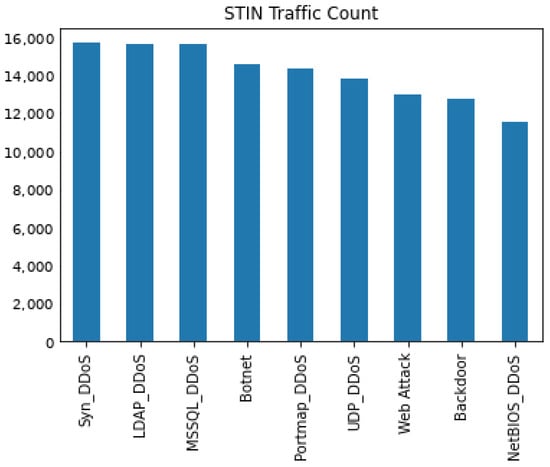

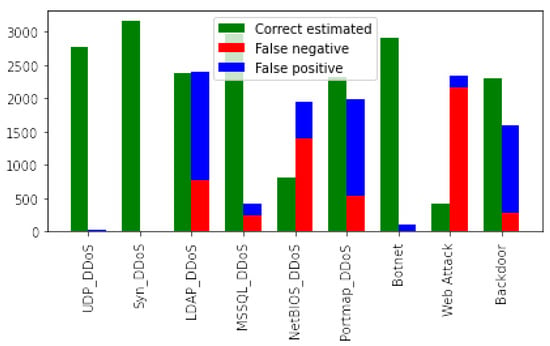

The STIN dataset consists of several attacks affecting aspects of the information security triad of confidentiality, integrity, and availability. There are several attacks affecting the availability of the systems in the dataset; these attacks include several distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks covering software such as LDAP, MSSQL, and NetBIOS protocols along with more generalized DDoS attacks such as portmap, UDP, and TCP Syn DDoS attacks. Attacks covering confidentiality and integrity of systems include botnet, web attacks, and backdoor attacks. Due to the nature of satellite communications as presented in [10], only two availability attacks, UDP and TCP Syn DDoS attacks, are present in the satellite portion of the dataset. The STIN dataset distributions are described in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the attack traffic by count for the STIN satellite intrusion dataset.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the attack traffic by count for the STIN terrestrial intrusion dataset.

3.1.2. NSL-KDD Dataset

The NSL-KDD dataset is a popular intrusion detection dataset that is an improvement upon the previous KDD-Cup 99 dataset proposed by MIT Lincoln Labs and the Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency. The dataset comprises of two datasets, a training and testing set, with four different classes of attacks. These attacks include probe attacks and remote-to-local attacks, which both affect confidentiality of systems, denial of service (DoS) attacks, which affect availability, and user-to-root (U2R) attacks, which affect the integrity of systems.

The NSL-KDD dataset has over 40 features reflective of local area networking traffic. The training dataset has over 125,000 observations, while the testing dataset has over 22,000 observations. Most common attacks in the NSL-KDD dataset are either grouped into DoS or probe attacks; U2R and R2L attacks are less frequent. For our work, we compare our models’ performance on the STIN dataset, both the satellite and terrestrial datasets, along with comparing our models on the standard NSL-KDD dataset to serve as a benchmark for intrusion detection performance [17].

3.2. Deep Q-Networks

Deep Q-networks are a popular reinforcement learning algorithm that implements the popular Q-learning algorithm. In reinforcement learning, an intelligent agent works to optimally select actions to take in an environment in order to maximize its reward. In our context, the agent observes current network traffic features and outputs a classification decision, then is rewarded based on whether this decision is correct.

We formulate our intrusion detection problem as a Markov decision process (MDP). At each time step t, the environment presents a state corresponding to the feature vector of the current observation from either the satellite, terrestrial, or local area network traffic. The agent then selects an action corresponding to the predicted class label (e.g., benign or a particular attack category). After the action is taken, the agent receives a reward that encodes the quality of the decision and transitions to the next state . In our offline experimental setup, we assign a reward of 1 for a correct classification and 0 for an incorrect classification. Episodes are formed by iterating through the examples in the training data, and experience replay buffers allow the DQN to learn from many such transitions.

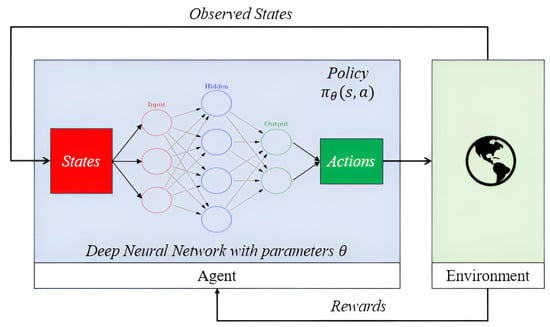

Q-learning is a model-free and off-policy reinforcement learning algorithm that does not require an explicit model of the environment and utilizes experience replay in order to determine the optimal actions to take in response to the provided states, akin to that depicted in Figure 3. The popular Q-learning algorithm for reinforcement learning is implemented by the equation:

where and are the current and next states, is the current action, is the reward at time , is the learning rate, and is the discount factor. A deep Q-network uses a neural network as a function approximator for , taking the state as input and outputting estimated Q-values for each possible action.

Figure 3.

A deep Q-network as an intelligent agent in a reinforcement learning environment. The neural network with parameters works as a function approximator to select actions a to take given states s provided by the environment. Figure adapted from [25].

For our deep Q-network, we set the states as the features provided by either the satellite or terrestrial network traffic, while the actions correspond to the classification of the network traffic. As stated previously, we set our reward to either 1 for correct classification or 0 for incorrect classification. In this offline setting, the reward signal is tightly coupled to the current prediction rather than to delayed predictions. Therefore, we choose hyperparameters that emphasize stable learning and immediate feedback.

We set our learning rate to , which ensures that Q-value updates occur gradually and the agent does not overreact to any single experience. A smaller learning rate also helps to stabilize training when using a neural network function approximator, reducing oscillations in the Q-values. Likewise, we choose a small discount factor of to prioritize immediate rewards. In intrusion detection environments, particularly in our batch-learning setup, the most informative signal is whether the current classification is correct, and there is limited benefit to propagating reward far into the future as would be the case in long-horizon control tasks. Therefore, a small discount factor aligns the optimization objective with per-step classification performance.

In our current formulation, the agent is trained offline on fixed datasets and receives an immediate reward tied only to the correctness of each individual classification. Combined with a small discount factor , this makes the optimization objective closely aligned with that of a standard supervised deep classifier, and the DQN behaves similarly to a multilayer perceptron. This approach allows us to directly compare a DQN-based policy with conventional supervised baselines on canonical intrusion detection datasets. Additionally, this approach serves as a stepping stone toward future work in which the agent interacts with a non-stationary environment and can adapt its policy online as satellite and terrestrial traffic conditions evolve. As such, or approach develops a unified reinforcement learning formulation across STIN and NSL-KDD that is consistent with prior RL-based IDS work while deferring full online adaptation and non-stationary training to future work.

Across all datasets, our DQN uses three hidden fully-connected layers with a softmax output. The DQN is trained with the Adam optimizer with a learning rate and batch size of 256 over 100 epochs. We compare the performance of our DQN in our SpIDER framework against other popular machine learning algorithms, namely, support vector machine (SVM), naive Bayes (NB), and multilayer perceptron (MLP). The SVM operates on standardized features with an RBF kernel, while the NB classifier is implemented as the Gaussian NB. We provide similar hyperparameters for our MLP; our MLP includes three hidden fully-connected layers with a softmax output trained with an Adam optimizer with similar learning rate, batch size, and epochs.

We selected the SVM, NB, and MLP models as benchmarks for two primary reasons. First, these models are widely used in the intrusion detection literature and provide a representative mix of linear-margin (SVM), probabilistic (NB), and deep neural network (MLP) classifiers [14,15]. Second, our choice aligns with prior deep reinforcement learning IDS studies, which commonly compare against SVMs and feedforward neural networks on NSL-KDD and related datasets [16,19]. Thus, using these baselines allows us to situate SpIDER within the existing literature and assess where a DQN-based approach provides advantages over established machine learning methods.

3.3. Shapley Additive Global Importance

While the advent of neural networks and deep learning algorithms has provided for greater accuracy in many computational tasks, neural networks are oftentimes described as “black boxes”. Many nonparametric models, including deep learning algorithms, suffer from diminished explainability compared to other linear methods. Prior methods to provide greater explainability into model classification included both SHAP [4] and LIME [5]. Notably, both SHAP and LIME provide only local interpretability of results; these methods do not consider “global” performance. Unlike both SHAP and LIME, Shapley Additive Global Importance (SAGE) provides a beneficial alternative, instead focusing on each feature’s global contribution to model performance. SAGE values provide a useful means of determining feature importance, and can be calculated through the following equation for random variables X and Y:

where D is the total feature space, d is a single feature from the feature space, S is the subset of features from the total feature space D, and I serves as the mutual information between both X and Y [6,20]. We graphically depict each of the features present in the STIN dataset to better assess which features contribute the most to our DQN’s classification performance.

4. Results

4.1. Performance Metrics

We apply five popular performance metrics to assess the performance and classification effectiveness of cyber attacks on both our satellite and terrestrial network intrusion detection data. These metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and geometric mean (G-mean). These aforementioned metrics comprise true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN).

Accuracy is calculated by . As opposed to accuracy, the precision metric instead focuses performance of positive predicting power; precision increases with a decrease number of false positives and is calculated as . Recall, otherwise known as sensitivity, is calculated as and focuses on reducing the number of false negatives while correctly classifying observations. The F1-score represents a single metric between both recall and precision, and is calculated as . While F1-score is considered a harmonic mean, we also consider the G-mean, calculated as .

To determine the best model, we prioritize the G-mean metric, as it incorporates all four submetrics of true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative. The G-mean metric also serves as a more balanced metric in instances of imbalanced traffic.To assess whether differences between models are statistically significant, we perform hypothesis tests on the scores obtained under 10-fold cross-validation. For each dataset and performance metric, we first identify the model with the highest mean score and then apply paired t-tests (with significance level ) comparing this best-performing model against each alternative. In the result tables, values marked with an asterisk (*) indicate that the corresponding model’s mean performance is significantly higher than that of all other models for that metric and dataset. An Intel i7 processor with 16 GB of RAM was used to obtain the results.

For the DQN, MLP, and SVM models, we standardize the continuous features by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation, using values computed from the training folds only. Our stratified 10-fold cross-validation is implemented so that each fold has similar class proportions to the full dataset. For the neural network models, we set a fixed random seed (with the random seed set to 42) for weight initialization and minibatch shuffling to make the results easier to reproduce.

4.2. Numerical Results

In this section, we provide our numerical results comparing our SpIDER DQN versus our benchmark models on the STIN satellite and terrestrial datasets and the NSL-KDD dataset.

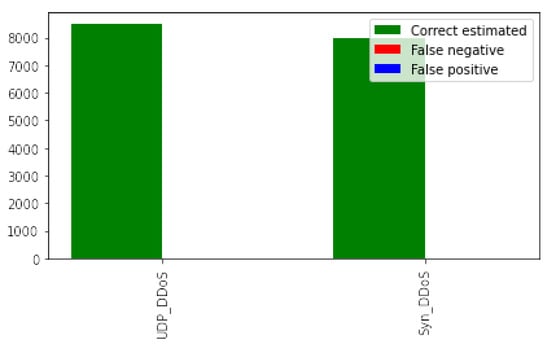

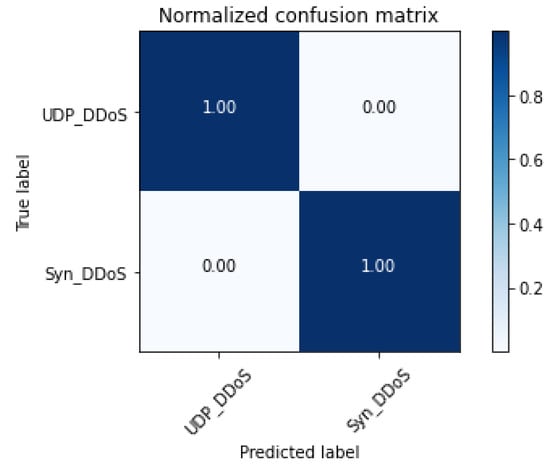

4.2.1. STIN Satellite Dataset

Table 1 provides the results comparing the benchmark machine learning algorithms against our SpIDER DQN on the STIN satellite dataset. We observe superior performance across all models on all metrics; there were no statistically significantly different results across the models. Our models obtained extremely high performance, with metrics at or above 99.98%. Notably, we observe that our SpIDER model had the lowest variance in results, suggesting that our model is a better algorithm as it provides more consistent results compared to other benchmarks. Our graphical results in Figure 4 and Figure 5 also reflect our SpIDER DQN’s superior classification performance on both the UDP DDoS and TCP Syn DDoS attacks.

Table 1.

Results from the models using the STIN satellite dataset. Best results per performance metric are indicated in bold. Statistically significant results are indicated by an asterisk (*).

Figure 4.

Bar chart of results from the STIN satellite dataset.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix of the results from the STIN satellite dataset.

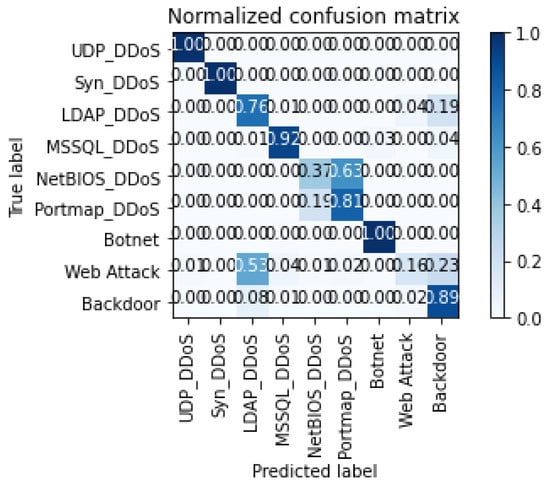

4.2.2. STIN Terrestrial Dataset

Table 2 provides the results comparing the benchmark machine learning algorithms against our SpIDER DQN for the STIN terrestrial dataset. Compared to the previous results observed on the STIN satellite dataset, we observe a drop in performance. Notably, we find that MLP statistically outperformed other models, while our SpIDER DQN managed to slightly outperform the naive Bayes classifier. While our model performed well on classification of UDP DDoS and TCP Syn DDoS, our SpIDER DQN struggled in classification of other DDoS attacks, such as LDAP, NetBIOS, and Portmap attacks. The model also struggled on the classification of webattack and backdoor attacks. The graphical results in Figure 6 and Figure 7 reflect our SpIDER DQN’s classification performance across the attacks present in the STIN terrestrial dataset.

Table 2.

Results from the base models using the STIN terrestrial dataset. Best results per performance metric are indicated in bold. Statistically significant results are indicated by an asterisk (*).

Figure 6.

Bar chart of results from the STIN terrestrial dataset.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of the results from STIN terrestrial dataset.

4.2.3. NSL-KDD Dataset

Table 3 provides the results comparing the benchmark machine learning algorithms against our SpIDER DQN for the NSL-KDD dataset. Compared to the previous STIN terrestrial dataset, we find that our SpIDER DQN statistically outperformed other models on all performance metrics. Interestingly, when compared with the STIN terrestrial dataset, we find that most models except for our SpIDER DQN decreased in performance; our SpIDER DQN had roughly the same performance on both datasets.

Table 3.

Results from the base models using the NSL-KDD dataset. Best results per performance metric are indicated in bold. Statistically significant results are indicated by an asterisk (*).

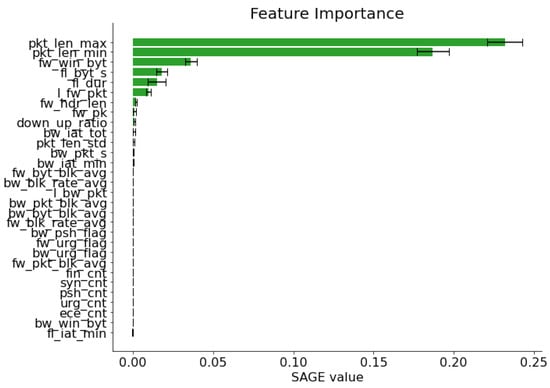

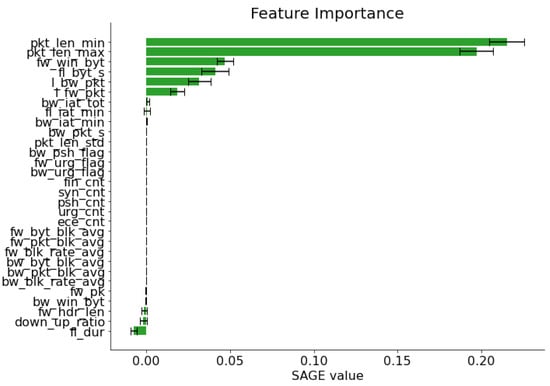

4.3. SAGE Plots

In this subsection, we provide SAGE outputs in order to determine the features that contributed most to our model performance. Figure 8 provides SAGE values for each of the features for the STIN satellite dataset that was present for our DQN classifier. Notably, in the output, we observe that the packet length features pkt_len_max and pkt_len_min had the highest SAGE values compared to all other features present in the dataset. These features also significantly impacted model performance compared to the next highest feature, fw_win_byt. Notably, for the STIN dataset there are only two attacks, UDP DDoS and TCP Syn DDoS; thus, these features contributed the most to accurate discernment of attacks for our DQN agent.

Figure 8.

Feature importance using SAGE values for our DQN model on the satellite STIN dataset.

Figure 9 provides SAGE values for each of the features present in the STIN terrestrial dataset for our DQN classifier. We observe similar SAGE values for our top three features, akin to the results for the previous STIN satellite dataset. Notably, compared to the STIN satellite dataset, on the STIN terrestrial dataset the fl_dur feature did not significantly contribute to the model performance compared to other features. Based upon Figure 9, withholding the fl_dur feature actually benefited model performance, since the SAGE value was negative. For the STIN terrestrial dataset, we note that more than two DoS attacks are present; the STIN terrestrial dataset comprises more attacks that affect more of the information security triad, including integrity and confidentiality attacks as opposed to availability attacks.

Figure 9.

Feature importance using SAGE values for our DQN model on the terrestrial STIN dataset.

5. Discussion

This work assesses the feasibility and performance of our SpIDER framework. The proposed framework consists of the popular DQN reinforcement learning technique in conjunction with model explainability through the application of SAGE values to assess feature importance. We analyzed our SpIDER framework for both satellite and terrestrial networking environments using the STIN dataset and for local area networking traffic using the NSL-KDD dataset. By evaluating the same DQN-based agent alongside conventional machine learning baselines on these different datasets, we can gain a better understanding of the performance of reinforcement learning algorithms compared with traditional models.

Notably, we observe that most of our machine learning benchmark models, including our SpIDER framework, exhibited the best performance on the STIN satellite dataset. The positive results observed on this dataset are likely indicative of the nature of the STIN satellite data. The STIN satellite dataset only consists of two major attacks, either UDP DDoS or TCP Syn DDoS, which are strongly characterized by volumetric behavior and result in highly separable patterns. All models, including our SpIDER DQN, achieved extremely high accuracy and related metrics, and there were no statistically significant differences across models. Our SpIDER DQN did have the lowest spread in results across all models, which indicates more consistent performance compared with the traditional machine learning benchmark models. These results suggest that for simple volumetric attacks in satellite environments, multiple learning algorithms can perform near-perfectly.

Our SpIDER framework did not perform as well as some of the benchmark machine learning models when applied to the STIN terrestrial dataset. On this dataset, the MLP model statistically outperformed the others, while our SpIDER DQN performed slightly better than the naive Bayes classifier but worse than the SVM and MLP models. The STIN terrestrial dataset includes a broader variety of attacks compared to the STIN satellite dataset, including LDAP, MSSQL, Portmap, and NetBIOS DDoS attacks as well as botnet, web, and backdoor attacks. These attacks affect different aspects of the information security triad and exhibit more heterogeneous behavior than the two satellite DDoS attacks. Our results indicate that in this more diverse setting, a carefully tuned supervised neural network (MLP) currently provides stronger performance than our DQN formulation.

A closer inspection of the STIN terrestrial confusion matrices reveals that the DQN particularly struggled on several attack types, including LDAP, NetBIOS, Portmap, web attacks, and backdoor traffic. These classes may exhibit more subtle feature patterns than the volumetric UDP and TCP Syn DDoS attacks that dominate the satellite dataset. In our current formulation, the DQN is trained with a uniform 0/1 reward and no explicit cost-sensitive weighting, which tends to bias learning towards the majority classes. By contrast, the supervised MLP appears better able to fit these minority classes under the same training. This observation suggests that in heterogeneous satellite–terrestrial environments with highly imbalanced attack distributions, reinforcement learning-based IDS may require stronger class reweighting, tailored reward shaping, or architectures that explicitly model temporal dependencies to match or surpass the performance of carefully tuned supervised baselines.

When applied to the NSL-KDD dataset, which is more indicative of local area networking traffic, we find that our SpIDER DQN statistically outperformed the other benchmark machine learning models across all performance metrics. Interestingly, when comparing the STIN terrestrial and NSL-KDD datasets, we observed our SpIDER DQN to maintain roughly similar performance, whereas most of the baseline models exhibited a drop in performance on NSL-KDD. This suggests that the reinforcement learning-based formulation remains robust as the attack mix and dataset characteristics change, and that the DQN model was particularly effective on the NSL-KDD benchmark even if it did not dominate on all satellite-related datasets. Taken together, these findings support viewing SpIDER as a first-step feasibility study. They demonstrate that a DQN-based approach can be competitive on satellite data and clearly advantageous on a widely used LAN intrusion detection benchmark.

The two features across the STIN datasets that contributed most to our model’s performance were pkt_len_min and pkt_len_max; both of these features had significantly higher SAGE values compared to that of other features in the STIN dataset. This aligns with the intuition that volumetric attacks such as UDP and TCP Syn DDoS attacks manifest primarily through packet length and traffic volume characteristics. Interestingly, the fl_dur feature had higher importance on the STIN satellite dataset compared to the STIN terrestrial dataset. When observing the difference in the attacks present in the datasets, we note that the STIN terrestrial dataset includes a greater variety of attacks affecting integrity and confidentiality in addition to availability. For these attacks, other features become relatively more important; in some cases excluding fl_dur is beneficial for performance, as reflected by its negative SAGE value on the terrestrial dataset. These differences are reflected in the SAGE plots, with different features contributing more to model performance when comparing the STIN satellite and terrestrial attack datasets.

From a practical standpoint, the SAGE analysis also provides guidance beyond pure performance numbers. The dominance of packet length features suggests that for satellite networks where on-board computation and downlink bandwidth are limited, it may be possible to design lightweight detectors or telemetry schemes that prioritize a small set of highly informative features. For more complex terrestrial traffic and mixed attack types, the broader set of influential features identified by SAGE can inform which additional flow statistics or header fields should be collected and monitored. In this way, global feature importance plays a role not only in interpreting the learned models but also in shaping future satellite and ground station data collection.

Finally, we briefly discuss deployment considerations. In real-world satellite systems, intrusion detection models must operate under constraints on latency, compute, and memory. While our experiments were conducted offline on conventional hardware, the DQN used in SpIDER is implemented as a compact feed-forward network with an inference cost comparable to that of an MLP with a similar architecture. Such models could be deployed on ground-based systems that process satellite and terrestrial traffic or in reduced form on resource-constrained onboard computers. Reinforcement learning further offers the potential for online adaptation to evolving attack patterns and traffic conditions by updating the policy as new data arrive. These benefits are most likely to be realized when the agent is carefully matched to the traffic characteristics and class distributions of the target environment and when its reward structure reflects realistic operational costs for different attack types, an aspect that is not fully exploited in our current batch-learning study but represents an important direction for future work.

6. Conclusions

Since the advent of space technologies in the 1950s, space systems and space technologies have continued to grow and become an integral part of our daily lives. Satellite systems provide the basis for many societal needs, especially with respect to satellite communications and networking. Unfortunately, due to the proliferation of cyber threats, space satellites have been subject to cyber attacks alongside terrestrial networking systems. These cyber threats prompt a need for robust space security systems.

In this work, we present our novel SpIDER framework, which applies an explainable reinforcement learning approach for space satellite intrusion detection. Our proposed framework comprises an intelligent DQN agent together with global model explainability through SAGE in order to better understand which features drive detection performance. We evaluated SpIDER on both satellite and terrestrial traffic from the STIN dataset and on local area networking traffic using the NSL-KDD intrusion detection dataset, comparing it against several popular machine learning baselines consisting of SVM, naive Bayes, and MLP classifiers.

Our experiments show that all models, including SpIDER, achieve near-perfect performance on the STIN satellite dataset, reflecting the relative separability of the two volumetric DDoS attacks (UDP and TCP Syn) present in the data. On the more diverse STIN terrestrial dataset, which includes a wider range of availability, integrity, and confidentiality attacks, the supervised MLP achieved the strongest overall performance, with our DQN-based SpIDER framework performing competitively but not surpassing the best baseline. In contrast, SpIDER statistically outperformed the other benchmark models across all evaluated metrics on the NSL-KDD dataset, which is widely used for local area network intrusion detection. Taken together, these results suggest that an explainable reinforcement learning-based approach can be competitive on satellite-style data and particularly effective on heterogeneous LAN traffic, but that its advantages are dependent on the dataset and attack mix.

Through our SAGE analysis, we found that the minimum and maximum packet length features pkt_len_min and pkt_len_max contributed the most to our model’s performance on both STIN datasets, aligning with the intuition that volumetric DDoS attacks are largely characterized by traffic volume and packet length patterns. We also observed that certain features such as fl_dur played different roles across the satellite and terrestrial settings, highlighting the sensitivity of feature importance to the underlying attack types and traffic characteristics. These global feature importance results not only provide insight into how the DQN makes decisions but also suggest which features might be prioritized for telemetry and monitoring in future satellite and ground station designs.

Future research directions include the application of actor–critic methods such as the asynchronous advantage actor–critic (A3C) model for satellite intrusion detection, as well as the incorporation of recurrent layers to capture temporal dependencies in network traffic. Evaluating reinforcement learning agents in online or non-stationary settings, where traffic patterns and attack strategies evolve over time, is another important step toward fully leveraging reinforcement learning’s sequential decision-making capabilities. Additional work can also extend the analysis to other data sources, such as satellite telemetry and control data, and further explore how global explainability methods like SAGE can inform feature selection, sensor design, and operational policies. Our work ultimately aims to provide safer and more secure satellite communications worldwide while demonstrating that explainable reinforcement learning is a viable and informative approach for both satellite and terrestrial intrusion detection.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the IEEE DataPort at https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/nsl-kdd-0 (accessed on 15 October 2025) for the NSL-KDD dataset and at Github at https://github.com/kun9717/STIN-data-set (accessed on 3 October 2025) for the STIN dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prol, F.S.; Ferre, R.M.; Saleem, Z.; Välisuo, P.; Pinell, C.; Lohan, E.S.; Elsanhoury, M.; Elmusrati, M.; Islam, S.; Çelikbilek, K.; et al. Position, navigation, and timing (PNT) through low earth orbit (LEO) satellites: A survey on current status, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 83971–84002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.; Levizzani, V.; Bauer, P. A review of satellite meteorology and climatology at the start of the twenty-first century. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2009, 33, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, C. The concept, technical architecture, applications and impacts of satellite internet: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Covert, I.; Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. Understanding global feature contributions with additive importance measures. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17212–17223. [Google Scholar]

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. A new Intelligent Satellite Deep Learning Network Forensic framework for smart satellite networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 99, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, S.; Moustafa, N.; Hassanian, M.; Ormod, D.; Slay, J. Deep-Federated-Learning-Based Threat Detection Model for Extreme Satellite Communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 3853–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, H.; Tu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. Distributed Network Intrusion Detection System in Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks Using Federated Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 214852–214865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheff, S.; Maxwell, E.; Plaks, C.; Simon, M. An Explainable Machine Learning Approach for Anomaly Detection in Satellite Telemetry Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2024; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, L.; Smet, P.; Arbon, E.; McDonnell, M.D. Anomaly detection in satellite communications systems using lstm networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, Australia, 13–15 November 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Jin, G.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, L. Satellite Telemetry Data Anomaly Detection Using Causal Network and Feature-Attention-Based LSTM. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, G.; Kumar, G. Machine learning and deep learning methods for intrusion detection systems: Recent developments and challenges. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 9731–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dina, A.S.; Manivannan, D. Intrusion detection based on machine learning techniques in computer networks. Internet Things 2021, 16, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Martin, M.; Carro, B.; Sanchez-Esguevillas, A. Application of deep reinforcement learning to intrusion detection for supervised problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 141, 112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallaee, M.; Bagheri, E.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A.A. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 8–10 July 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Gritzalis, S. Intrusion detection in 802.11 networks: Empirical evaluation of threats and a public dataset. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 18, 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminero, G.; Lopez-Martin, M.; Carro, B. Adversarial environment reinforcement learning algorithm for intrusion detection. Comput. Netw. 2019, 159, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rookard, C.; Khojandi, A. RRIoT: Recurrent reinforcement learning for cyber threat detection on IoT devices. Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, K.; Sai Rupesh, E.; Kumar, R.; Bera, P.; Venu Madhav, Y. A context-aware robust intrusion detection system: A reinforcement learning-based approach. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2020, 19, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivity, A.; Kamay, Y.; Laor, D.; Lublin, U.; Liguori, A. kvm: The Linux virtual machine monitor. In Proceedings of the Linux Symposium, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 27–30 June 2007; Volume 1, pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhou, H.; Luo, H.; Yu, S. SERvICE: A software defined framework for integrated space-terrestrial satellite communication. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2017, 17, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, N.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y. Enabling efficient service function chaining by integrating NFV and SDN: Architecture, challenges and opportunities. IEEE Netw. 2018, 32, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rookard, C. Cyber Threat Detection using Multifaceted Machine Learning Approaches. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.