Navigating the Future of Education: A Review on Telecommunications and AI Technologies, Ethical Implications, and Equity Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives of This Review

- Map the growth of AIEd and the facilitating telecommunication technologies of 5G/6G, IoT, MEC, edge cloud computing, and smart campus network architecture from 2022 to 2025, as well as the role of network-level attributes of latency, bandwidth, and device density.

- Report on the impact of AI on educational practices, engagement, teaching workloads, and efficiency.

- Critically appraise risks and governance-data privacy, algorithmic bias, equity, and integration constraints.

- Derive evidence-based recommendations for future research and policy to enable transparent, fair, and inclusive AIEd adoption.

1.2. Research Questions

- What are the most significant AIEd applications (published since 2022), what are their enabling telecom infrastructures (5G/6G, IoT, MEC), and how are these implemented across educational levels and contexts?

- What are the measured effects of AIEd on teaching and learning outcomes—namely, student engagement and performance, teacher workload, and administrative efficiency?

- What ethical, privacy, security, and bias challenges arise in AIEd deployments, and which governance controls are reported as effective?

- What trends and research gaps does the contemporary literature report (methods, metrics, datasets, and reporting standards), and what designs are most needed to strengthen external validity (e.g., longitudinal, multi-site RCTs)?

- What role can the community of practitioners play in developing effective AIEd strategies and adapting AI solutions to address challenges of access experienced in underserved regions?

1.3. Significance of This Study

1.4. Structure of This Review

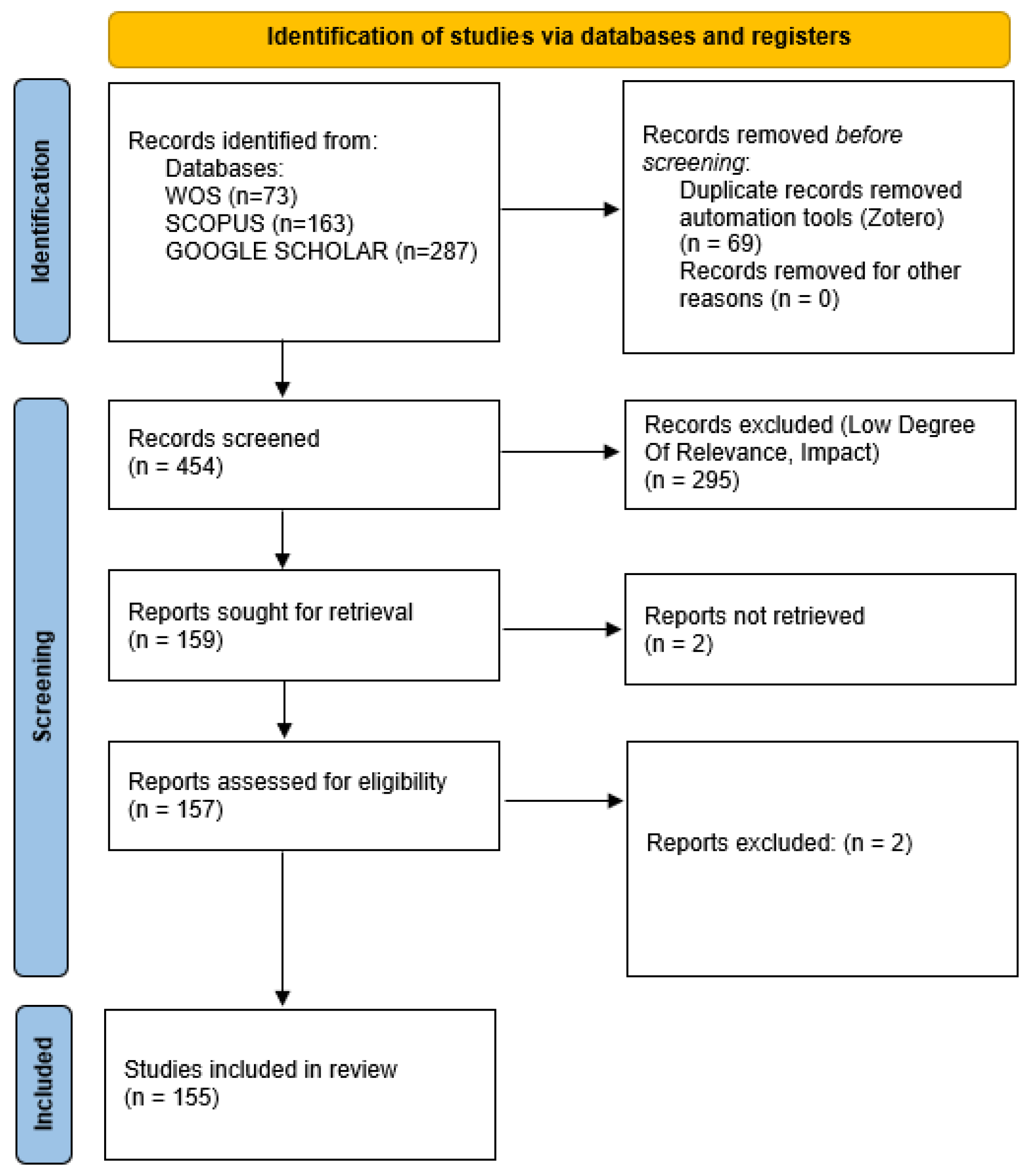

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Procedure

2.2. Study Quality Assessment

2.3. Integration of Telecommunications and Educational Evidence

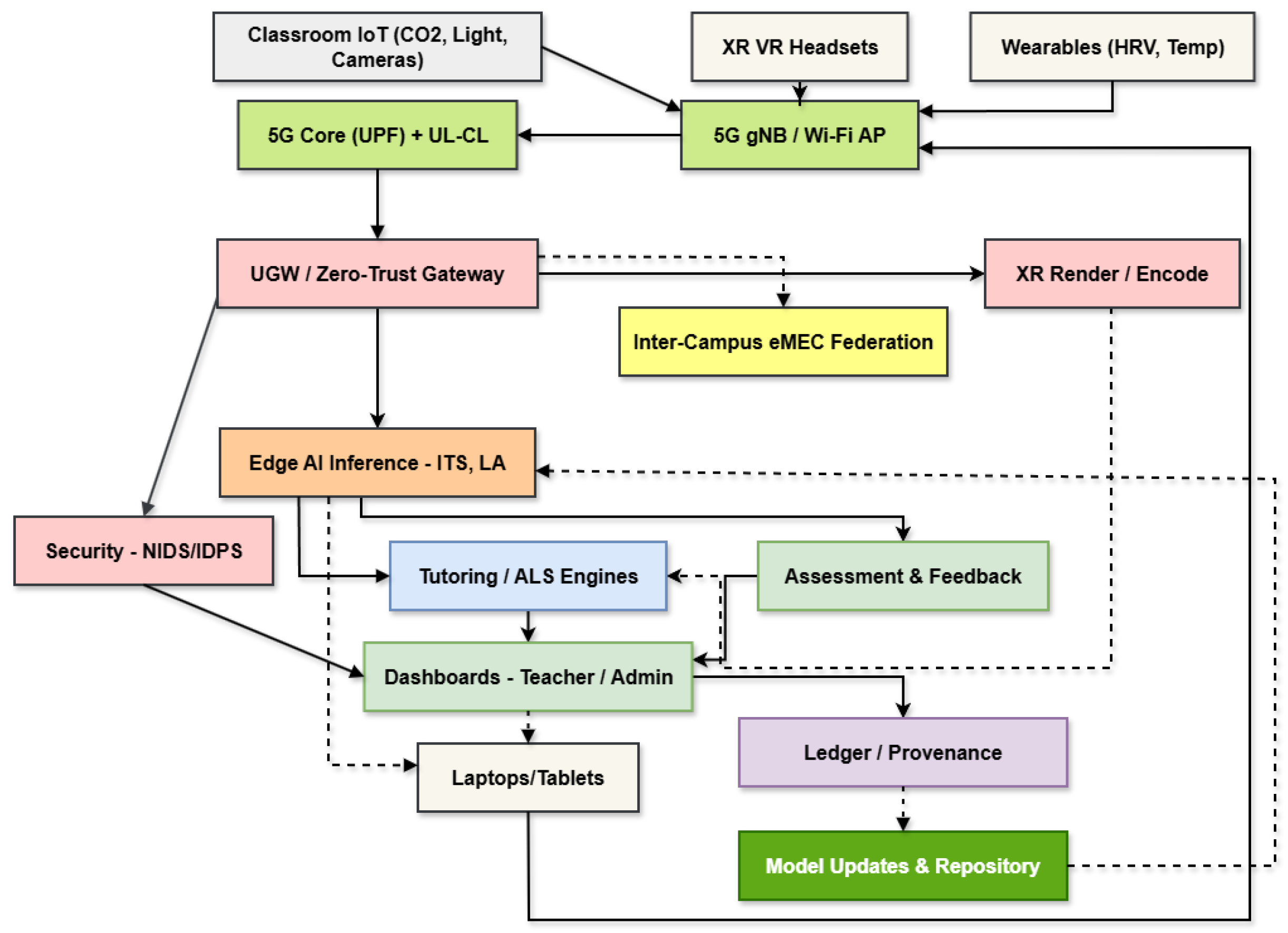

3. Telecommunications Infrastructure for AI-Driven Education

3.1. Fifth-Generation (5G) Networks Enabling Immersive, Interactive Learning

- XR/VR teaching modules with real-time instructor intervention and multi-party collaboration. A dedicated 5G private network powering a metaverse training platform supported CNC, acetylene welding, and forklift operation in VR, improving safety (no physical risk), operational efficiency, and student engagement while maintaining synchronous control/video feedback [13].

- Interactive classrooms (holographic telepresence, speech recognition, live translation) where 5G bandwidth and low jitter maintain continuity of AI-mediated activities [13]. Syntheses of XR in education report improved engagement, knowledge/skill gains, and inclusivity when networks sustained low-latency media plus AI guidance [14,27,28]. Recent metaverse research shows that XR and Internet-of-Everything pipelines can sustain feedback-driven, experiential modules that bridge theory and hands-on practice while preserving real-time instructor intervention; the same work highlights deployment constraints—data privacy, inclusivity, and scalability—and calls for compact XR clients for low-power devices and improved graphical/UI fidelity to broaden access [29].

3.2. IoT Backbones for Sensor-Rich, AI-Adaptive Classrooms

- Remote/Hybrid labs. An IoT-powered electronics lab (ESP8266, sensors/actuators, smartphone control via Blynk) enabled six physical experiments to be completed entirely online; >70% of students preferred it over simulation-only labs, with only two non-completions in the cohort, demonstrating feasibility of authentic hands-on practice feeding AI dashboards even at a distance [38].

- Heterogeneous IoT networking. At scale, low-power protocols (e.g., LoRaWAN, ZigBee, 6LoWPAN) interface with 5G/Wi-Fi backhaul through an edge gateway, enabling real-time MQTT/CoAP telemetry to local AI services while keeping constrained devices efficient [4]. This pattern supports dense, mixed fleets (wearables, lab instruments, cameras) without saturating core links.

- AIoT pilots for “greening” SLEs. Across three case studies, AI&IoT dashboards and plant biosensors supported the following: (i) primary education activities via a smart plant dashboard; (ii) university classrooms where CO2, illumination, and temperature drove personalised environmental recommendations; and (iii) inference of human presence/activity from plant electrophysiology. These factors demonstrate the privacy-aware, analytics-guided optimisation of learning spaces [39].

- Security implication. A recent survey of ML-based intrusion detection for IoT underscores that campus-scale IoT (wearables, labs, cameras) requires edge-resident NIDS trained under severe class imbalance; effective pipelines combine rebalancing (over-/under-sampling, synthetic generation), lightweight DL, and, increasingly, few-shot/self-supervised schemes to generalise across verticals (medical/industrial/edge IoT, ITS, smart home). This review argues for coupling IDS placement with MEC and zero-trust gateways so that telemetry never leaves the local fabric unvetted [40].

- Physiological sensing and on-the-fly personalisation with secure data governance. Xie et al. introduced SHARP, which couples wearable WSNs (e.g., HRV, temperature, stress markers) with a DNN for state recognition and a reinforcement-learning policy to adapt instruction in real time; integrity and access are anchored by a Proof-of-Authority blockchain [41]. In simulation-driven evaluation, SHARP reports an F1-score of for affect/physiology classification, a packet-delivery ratio, and a reduction in WSN energy consumption versus baselines; the smart contract layer also detects all tampering attempts in their tests. Beyond sensing, the RL agent reduces intervention latency and—when enabled—yields large gains in short formative assessments relative to control conditions, demonstrating the coupling of sensing, analytics, and trusted logging for classroom adaptivity [41].

3.3. MEC: Placing AI Inference and Orchestration at the Campus Edge

- Edge AI for rapid feedback. A 5G and edge-enabled teaching–evaluation platform reduced response time by 11.45% over a cloud-only baseline, enabling within-session feedback loops (e.g., engagement signals from multimodal classroom data) [45]. A cloud-edge evaluation for autism spectrum disorder proposes edge-deployed facial analysis (AlexNet, 224 × 224 input; 60:20:20 train/val/test on ∼3000 images) with SoftMax classification, reporting ≈92% accuracy (K-fold robustness checks). The authors argue edge placement balances latency, cost, and privacy constraints in educational settings, while supporting early, school-based screening workflows [46].

- Privacy-aware analytics. In terms of campus patterns, edge nodes perform on-site vision/NLP analytics (engagement, at-risk detection) and stream only de-identified summaries to the cloud. The same edge tier also hosts AI-driven intrusion detection to protect sensitive IoT/biometric flows in real time. Ref. [4] reports that zero-trust architectures coupled with AI-driven IDPS can mitigate the enlarged 5G/IoT attack surface, though adoption remains bounded by budget, teacher training, and regulatory compliance constraints. Pushing pre-processing and inference to fog/edge nodes reduces exposure of personally identifiable data in transit and at rest, enables decentralised storage with lower latency, and supports privacy-preserving computation (e.g., on-node anonymisation, secure multi-party aggregation, and fine-grained cryptographic access control for LA dashboards). Ref. [47] also notes the need for standards and operational guidance to address technical and ethical tradeoffs when migrating LA from cloud-only to edge-first pipelines.

3.4. Towards Future Network Directions

3.5. Case Snapshots and Outcomes

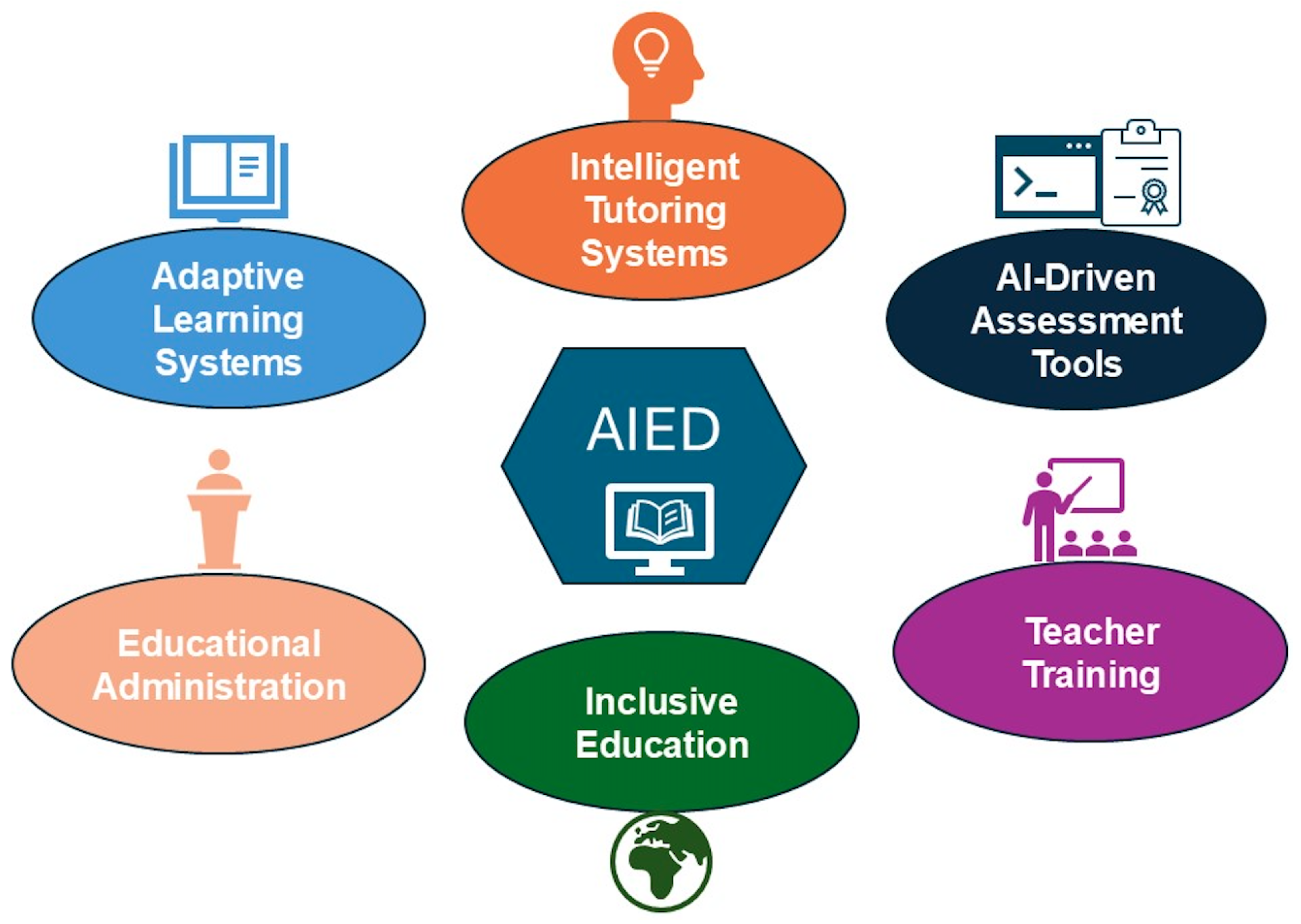

4. Applications

4.1. Adaptive Learning Systems

4.2. ITS

4.3. AI-Driven Assessment Tools—Academic Performance

4.4. AIEd Administration

4.5. Inclusive Education and Teachers’ Training Using AI/ITS

Teacher Training

4.6. Cross-Cutting Patterns and Tensions Across AIEd Applications

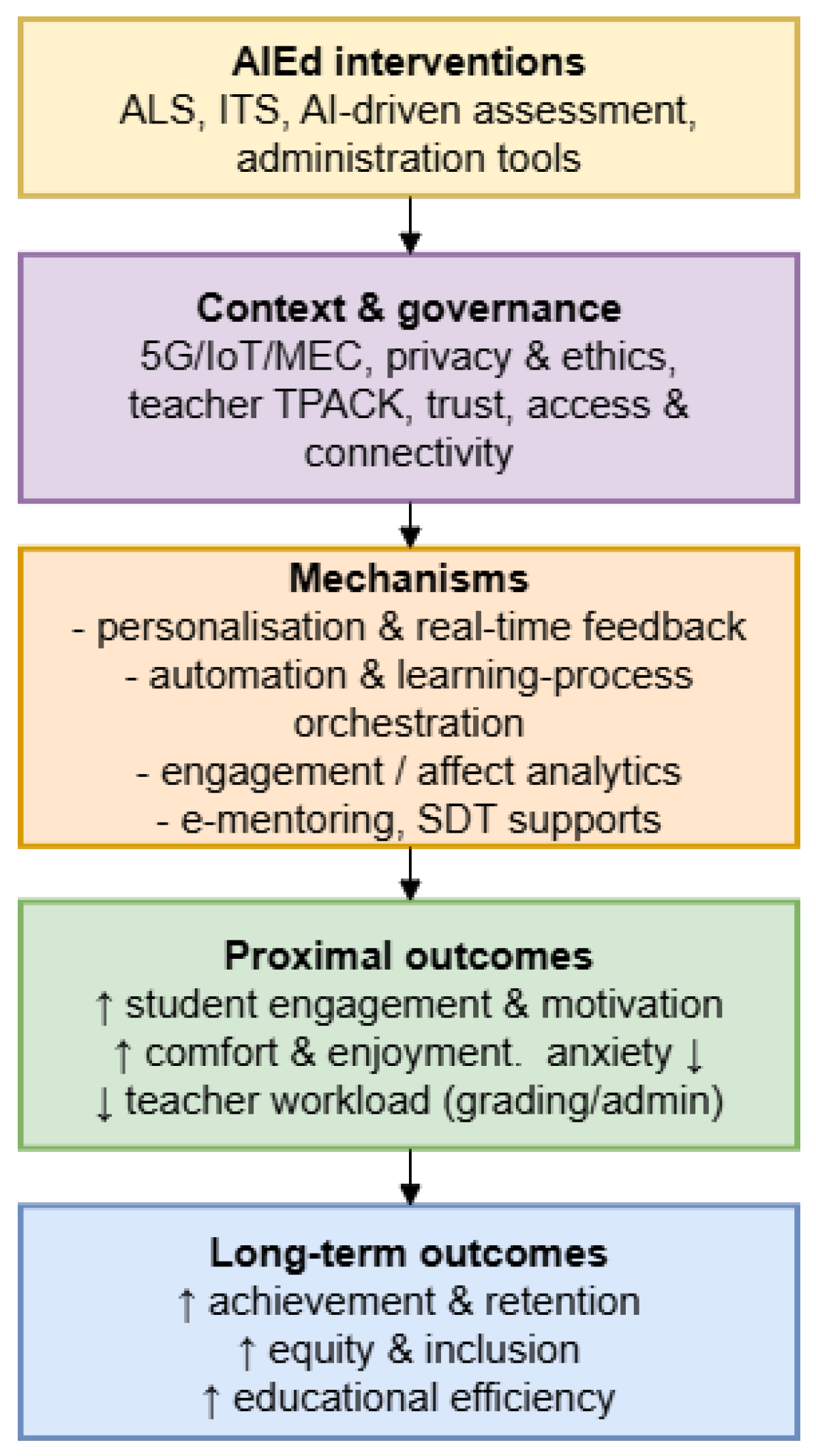

5. Impact of AI on Educational Outcomes

5.1. Student Engagement

5.2. Teacher Workload

5.3. Limitations of the Current Outcome Evidence

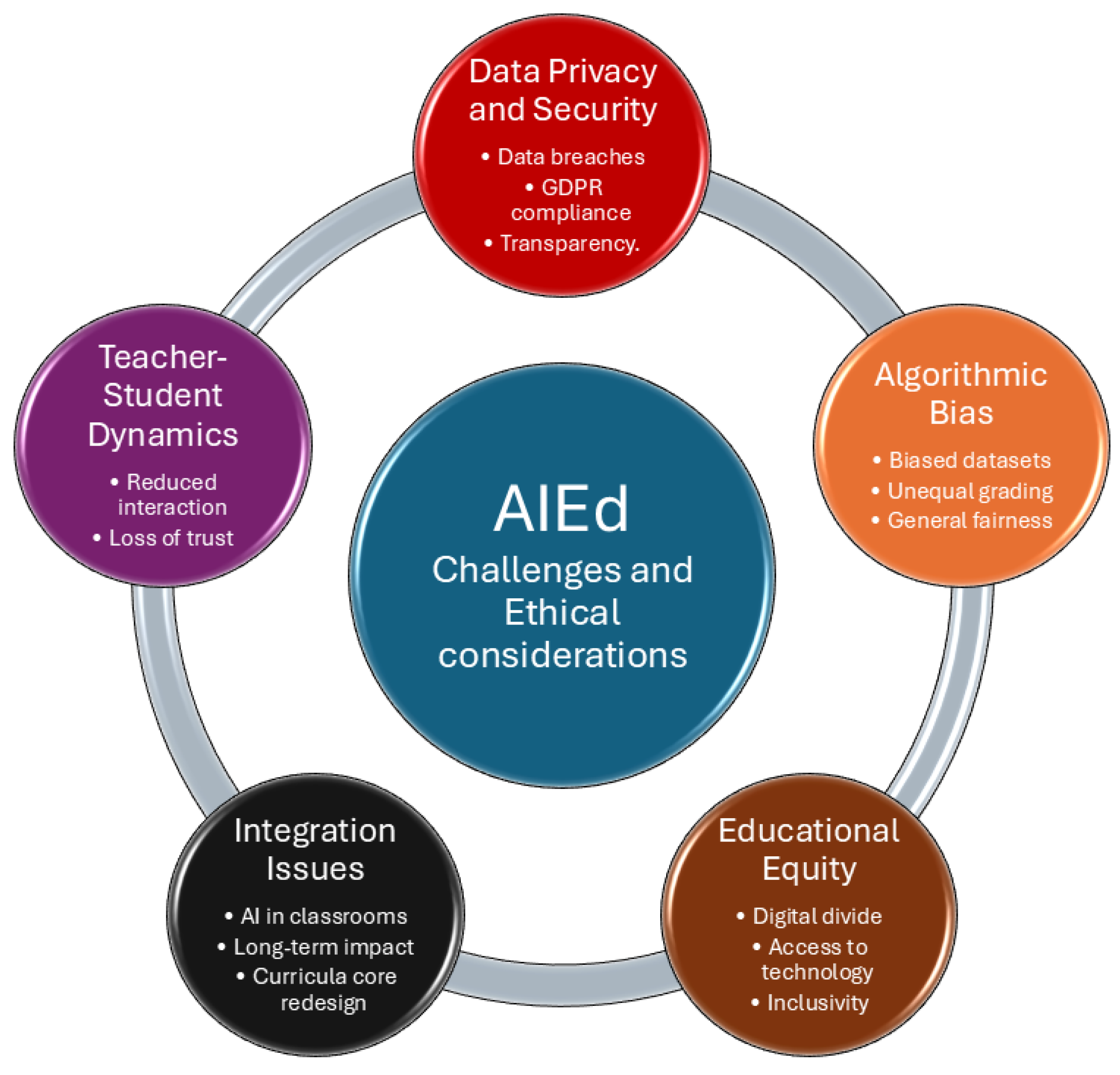

6. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

6.1. Data Privacy and Security

6.2. Algorithmic Bias

6.3. Educational Equity

6.4. Integration Issues

7. Key Factors for Transforming AITE

7.1. Emerging AI Technologies

7.2. Infrastructure as a Cross-Cutting Determinant

7.3. Immersive Learning with AR, VR, and Robotics

7.4. AI-Driven Learning Analytics and Virtual Assistants

7.5. Adaptive Learning and ML

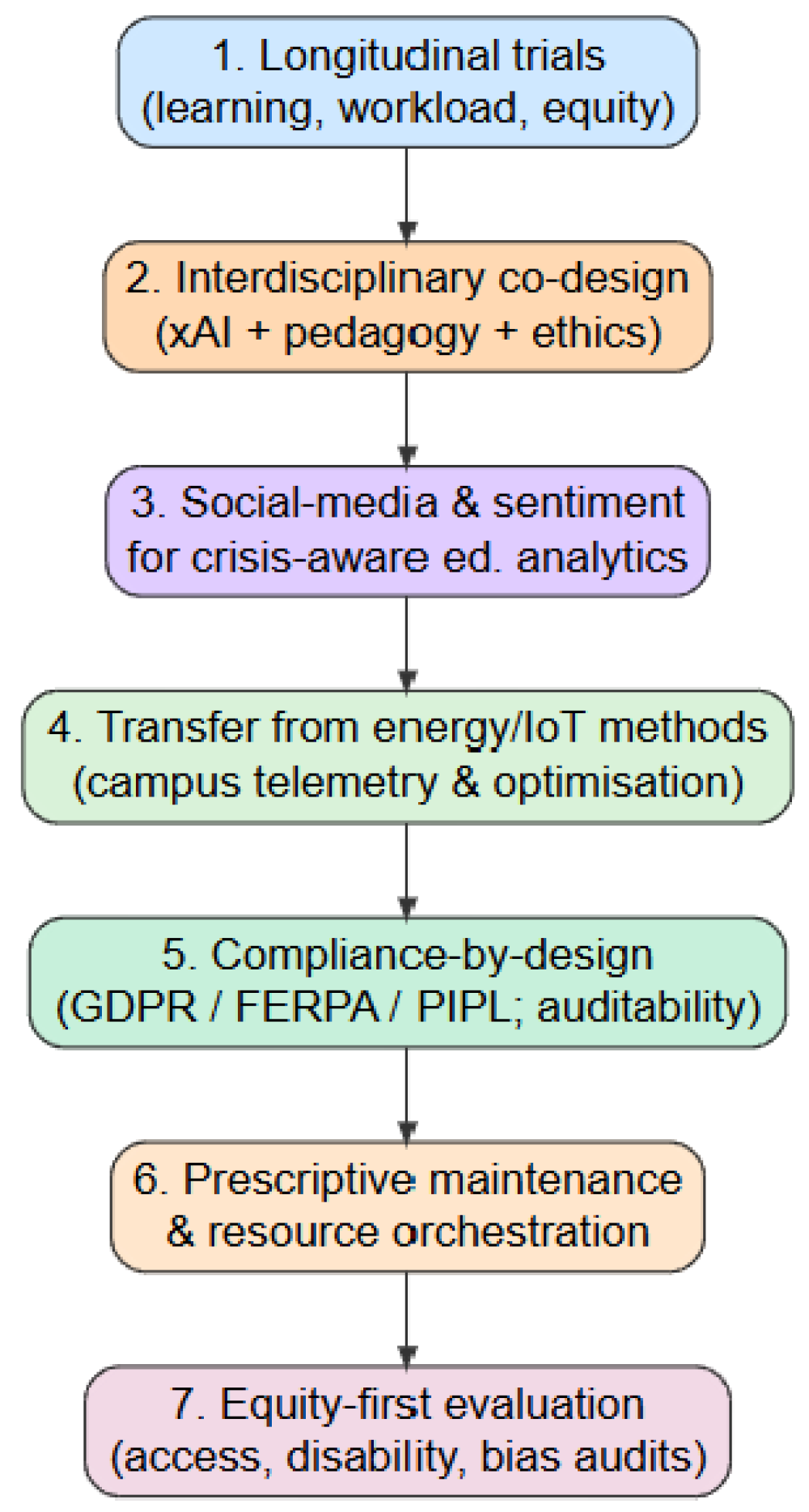

8. Recommendations for Future Research

- Longitudinal studies will be critical in tracking AI’s impact on learning outcomes and will have to record network metrics such as latency, bandwidth variance, and edge usage to examine the impact of telecom performance on student performance.

- To make AI more in line with excellent pedagogy and ethics, AI research work can focus on model logic and network function. xAI can work on prioritisation in MEC models, and recommendations can highlight AI supporting teachers in data-driven pedagogy with preserved autonomy, increasing trust in these solutions.

- The impact of social media on education and healthcare requires continuous, accurate tracking to balance both biased and objective perspectives [102]. During emergencies, sentiment analysis in educational systems can assist teachers in understanding reactions to health messages among students and can aid in developing an engaged learning environment. Combining Quality-of-Experience (QoE) analysis with sentiment analysis can relate student emotions to network stability and delay variance.

- In addition to AIEd, existing mature predictive application domains, such as energy, have methods with good transferability. A mixed-methodology mapping of sustainable AI in energy shows how application domains include sustainable buildings, AI-driven DSS for water in cities, climate AI, Agriculture 4.0, convergence of IoT, AI assessment of renewables, smart campuses, and education-oriented optimisation. Application domains in education include learning analytics at a scale suitable for campuses, optimised lab/resource allocation, and solid xAI baselines for safety-critical considerations [78,79,80,154].

- AIEd in ITS operating on educational data for adaptive learning must abide by guidelines like GDPR, FERPA, or Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) [101,155]. In addition, working to remove bias in AI systems, which can be problematic in forecasting academic performance or college admission, is important in AITE [18,135]. For AITE, research work must incorporate traceability and cyber resilience in accordance with guidelines from the AI Act in the EU.

- Prescriptive maintenance with AI in education can potentially improve efficiency and resource utilisation, assisting in fast fault identification and time-efficient building maintenance. Such models can also examine how interlinked data networks improve learning personalisation and efficiency [104,156,157].

9. Discussion

9.1. Findings by Research Question

9.2. Limitations

9.3. Research Pathways

9.4. Practical Implications for Institutions and Practitioners

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | Third-Generation Partnership Project |

| 4IR | Fourth Industrial Revolution |

| 5IR | Fifth Industrial Revolution |

| 5G | Fifth-Generation Mobile Networks |

| 6G | Sixth-Generation Mobile Networks |

| AES | Automated Essay Scoring |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIEd | Artificial Intelligence in Education |

| AITE | AI-Enabled Telecommunication-Based Education |

| AIoT | Artificial Intelligence of Things |

| ALP | Adaptive Learning Platforms |

| ALS | Adaptive Learning Systems |

| ANLS | Adaptive Neuro-Learning System |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CKT | Conjunctive Knowledge Tracing |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CoAP | Constrained Application Protocol |

| C-PSO | Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimisation |

| CRDNN | Convolutional Recurrent Deep Neural Network |

| CT | Computational Thinking |

| DESI | Digital Economy and Society Index |

| DiLi | Digital Literacy |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| DTree | Decision Tree |

| E2E | End-to-End |

| EAIEd | Ethical AI in Education |

| EDM | Expert Decision-Making |

| eMBB | Enhanced Mobile Broadband |

| eMEC | Educational Multi-Access Edge Computing |

| eMEP | Educational MEC Platform |

| ENA | Epistemic Network Analysis |

| FATE | Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, and Ethics |

| FERPA | Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GAIL | Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| HCAI | Human-Centred AI |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| IaaS | Infrastructure as a Service |

| IDEE | Intelligent Digital Education Environment |

| IDPS | Intrusion Detection and Prevention System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IPFS | InterPlanetary File System |

| IRS | Information Retrieval Systems |

| ITS | Intelligent Tutoring Systems |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbour |

| LA | Learning Analytics |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| LMS | Learning Management Systems |

| LoRaWAN | Long Range Wide Area Network |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| MEC | Multi-Access Edge Computing |

| MOOCs | Massive Open Online Courses |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MWPs | Math Word Problems |

| NIDS | Network Intrusion Detection System |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| ODeL | Open Distance e-Learning |

| OER | Open Educational Resources |

| O-RAN | Open Radio Access Network |

| P-AIEd | Positive Artificial Intelligence in Education |

| PIPL | Personal Information Protection Law |

| PISA | Programme for International Student Assessment |

| PPM | Push–Pull–Mooring |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SAG | Short-Answer Grading |

| SBERT | Sentence-BERT |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| SLE | Smart Learning Environment(s) |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SRL | Self-Regulated Learning |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TinyML | Tiny Machine Learning |

| TPACK | Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge |

| UGW | Universal Gateway |

| UL-CL | Uplink Classifier |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation |

| UPF | User Plane Function |

| URLLC | Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communications |

| USE-DAN | Universal Sentence Encoder—Deep Averaging Network |

| USE-T | Universal Sentence Encoder—Transformer |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| WAP | Wireless Access Point |

| Wi-Fi 6 | Wi-Fi 6 (IEEE 802.11ax) |

| WOS | Web of Science |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

| xAI | Explainable AI |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| ZPD | Zone of Proximal Development |

References

- Bellas, F.; Guerreiro-Santalla, S.; Naya, M.; Duro, R.J. AI Curriculum for European High Schools: An Embedded Intelligence Approach. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lee, I.; Ali, S.; DiPaola, D.; Cheng, Y.; Breazeal, C. Integrating Ethics and Career Futures with Technical Learning to Promote AI Literacy for Middle School Students: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 290–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Fu, L.; Wei, Y. Educational 5G Edge Computing: Framework and Experimental Study. Electronics 2022, 11, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukaras, C.; Koukaras, P.; Ioannidis, D.; Stavrinides, S.G. AI-Driven Telecommunications for Smart Classrooms: Transforming Education Through Personalized Learning and Secure Networks. Telecom 2025, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggag, M.; Oulefki, A.; Amira, A.; Kurugollu, F.; Mushtaha, E.S.; Soudan, B.; Hamad, K.; Foufou, S. Integrating advanced technologies for sustainable Smart Campus development: A comprehensive survey of recent studies. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 66, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Iqbal, W.; El-Hassan, A.; Qadir, J.; Benhaddou, D.; Ayyash, M.; Al-Fuqaha, A. Data-Driven Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemani, S. Evaluating the impact of artificial intelligence on reducing administrative burden and enhancing instructional efficiency in middle schools. Curr. Perspect. Educ. Res. 2025, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposato, M. Artificial intelligence in educational leadership: A comprehensive taxonomy and future directions. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2025, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gunjan, V.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, R.K.; Nawaz, N. SeisTutor: A Custom-Tailored Intelligent Tutoring System and Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Sayed, N.; Singh, J.; Shafi, J.; Khan, S.; Ali, F. AI student success predictor: Enhancing personalized learning in campus management systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iFlyTek. iFLYTEK Supports Sichuan Province’s High-Quality Education Through Artificial Intelligence. 2024. Available online: https://www.iflytek.com/en/news-events/news/41.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Dhananjaya, G.; Goudar, R.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Rathod, V.N.; Hukkeri, G.S. A Digital Recommendation System for Personalized Learning to Enhance Online Education: A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 34019–34041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.E.; Chang, L.W.; Chin, H.H. 5G Metaverse in Education. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2024, 29, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G. Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Intelligent Tutoring Systems in Education and Training: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Olmo-Munoz, J.; Antonio Gonzalez-Calero, J.; Diago, P.D.; Arnau, D.; Arevalillo-Herraez, M. Intelligent tutoring systems for word problem solving in COVID-19 days: Could they have been (part of) the solution? ZDM-Math. Educ. 2023, 55, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, A.; Mishra, D.; Nachenahalli Bhuthegowda, B. NAO vs. Pepper: Speech Recognition Performance Assessment. In Human–Computer Interaction; Kurosu, M., Hashizume, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 156–167. ISBN 978-3-031-60412-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.; Ngo, H.N.; Hong, Y.; Dang, B.; Nguyen, B.P.T. Ethical principles for artificial intelligence in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4221–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaus, M.; Sailer, M. Closing the loop—The human role in artificial intelligence for education. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 956798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, S.T.H.; Sampson, P.M. The development of artificial intelligence in education: A review in context. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1408–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S.; Tawil, S.; Miao, F.; Holmes, W. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, B.; Emerson, L.; Van Luyn, A.; Dyson, B.; Bjork, C.; Thomas, S.E. A scholarly dialogue: Writing scholarship, authorship, academic integrity and the challenges of AI. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B. AI must be kept in check at school: The use of artificial intelligence in education needs to be subject to supervision and independent evaluations. UNESCO Cour. 2023, 2023, 6–9. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000387030_eng (accessed on 30 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Tran, T.; Du, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameras, P.; Arnab, S. Power to the Teachers: An Exploratory Review on Artificial Intelligence in Education. Information 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierres, O.; Christen, M.; Schmitt-Koopmann, F.M.; Darvishy, A. Could the Use of AI in Higher Education Hinder Students With Disabilities? A Scoping Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 27810–27828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crogman, H.T.; Cano, V.D.; Pacheco, E.; Sonawane, R.B.; Boroon, R. Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and Mixed Reality in Experiential Learning: Transforming Educational Paradigms. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X. Application and effect analysis of virtual reality technology in vocational education practical training. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 9755–9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamola, V.; Peelam, M.S.; Mittal, U.; Hassija, V.; Singh, A.; Pareek, R.; Mangal, P.; Sangwan, D.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C.; Mahmud, M.; et al. Metaverse for Education: Developments, Challenges, and Future Direction. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2025, 33, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, R.; Nashiroh, P.K. Analysis of the Readiness of Students in Automotive Engineering Education at Universitas Negeri Semarang to Engage in Learning with Generative AI. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2025, 7, e2025528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboderin, O.S.; Pietersen, D.; Langeveldt, D. Exploring the Promotion of Skills Development in an ODeL Space Vis-À-Vis 4IR Technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiz-Ibanez, H.; Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; Carus Candas, J.L. The metaverse: Privacy and information security risks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2025, 5, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wu, S.; Peng, B.; Wang, X. An Artificial Intelligence–Enhanced Coaching Mode. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 6469–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiu, P.; Nitti, M.; Pilloni, V.; Cadoni, M.; Grosso, E.; Fadda, M. Metaverse & Human Digital Twin: Digital Identity, Biometrics, and Privacy in the Future Virtual Worlds. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijitha, S.; Anandan, R. Metaverse Technology to Empower Students Literacy Rate Using Modern Educational Resources in Kanchipuram District. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. B 2025, 0, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.A.A. In the Metaverse We (Mis)trust? Third-Level Digital (In)equality, Social Phobia, Neo-Luddism, and Blockchain/Cryptocurrency Transparency in the Artificial Intelligence-Powered Metaverse. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2024, 27, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsipianitis, D.; Misirli, A.; Lavidas, K.; Komis, V. IoT Devices and Their Impact on Learning: A Systematic Review of Technological and Educational Affordances. IoT 2025, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, F.V.; Hayashi, V.T.; Arakaki, R.; Midorikawa, E.; de Mello Canovas, S.; Cugnasca, P.S.; Corrêa, P.L.P. Teaching Digital Electronics during the COVID-19 Pandemic via a Remote Lab. Sensors 2022, 22, 6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuenca, B.; Uche-Soria, M.; Greller, W.; Hernández-Leo, D.; Balcells-Falgueras, P.; Gloor, P.; Garbajosa, J. Greening smart learning environments with Artificial Intelligence of Things. Internet Things 2024, 25, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, D. Recent endeavors in machine learning-powered intrusion detection systems for the Internet of Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 229, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, X. SHARP: Blockchain-Powered WSNs for Real-Time Student Health Monitoring and Personalized Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. The Convergence of Intelligent Tutoring, Robotics, and IoT in Smart Education for the Transition from Industry 4.0 to 5.0. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 325–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Jawwad, A.K.; Turab, N.; Al-Mahadin, G.; Abu Owida, H.; Al-Nabulsi, J. A perspective on smart universities as being downsized smart cities: A technological view of internet of thing and big data. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2024, 35, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. TinyML Based Edge Intelligent English Classroom Quality Assessment Scheme. Internet Technol. Lett. 2025, 8, e70072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, C. Artificial intelligence and edge computing for teaching quality evaluation based on 5G-enabled wireless communication technology. J. Cloud Comput. Adv. Syst. Appl. 2023, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Foroughi, A. Evaluation of AI tools for healthcare networks at the cloud-edge interaction to diagnose autism in educational environments. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Filva, D.; Fonseca, D.; García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Forment, M.A.; Casany Guerrero, M.J.; Godoy, G. Exploring the landscape of learning analytics privacy in fog and edge computing: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulova, N.; Mavlonova, M.; Khudaykulov, A.; Bakaeva, F.; Allaberganov, O.; Saidov, K.; Sapaev, I.B.; Yoqubov, D. Designing Energy-Efficient Wireless Language Learning Platforms for Remote Education. J. Wirel. Mob. Netw. Ubiquitous Comput. Dependable Appl. 2025, 16, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.O.; Toston, D.M. ChatGPT and Digital Transformation: A Narrative Review of Its Role in Health, Education, and the Economy. Digital 2025, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohanean, D.I.; Vulpe, A.M.; Mijaica, R.; Alexe, D.I. Embedding Digital Technologies (AI and ICT) into Physical Education: A Systematic Review of Innovations, Pedagogical Impact, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, L.O.; Okebanama, U.F.; Mba, G.U. Enhancing entrepreneurial skills through experiential learning in IoT, AI, and cybersecurity. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Christensen, C.; Cui, W.; Tong, R.; Yarnall, L.; Shear, L.; Feng, M. When adaptive learning is effective learning: Comparison of an adaptive learning system to teacher-led instruction. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrino, M.F.; Reyes-Millán, M.; Vâzquez-Villegas, P.; Membrillo-Hernández, J. Using an adaptive learning tool to improve student performance and satisfaction in online and face-to-face education for a more personalized approach. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenório, K.; Dermeval, D.; Monteiro, M.; Peixoto, A.; Silva, A.P.d. Exploring Design Concepts to Enable Teachers to Monitor and Adapt Gamification in Adaptive Learning Systems: A Qualitative Research Approach. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 867–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuskovych-Zhukovska, V.; Poplavska, T.; Diachenko, O.; Mishenina, T.; Topolnyk, Y.; Gurevych, R. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Problems and Opportunities for Sustainable Development. BRAIN. Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 339–356. Available online: https://www.edusoft.ro/brain/index.php/brain/article/view/1272. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Kong, Y.; Cheng, W.; Hao, C.; Lin, Q. Data-Driven Personalized Learning Path Planning Based on Cognitive Diagnostic Assessments in MOOCs. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chae, Y.; Kim, S.; Im, C.H. Development of a Computer-Aided Education System Inspired by Face-to-Face Learning by Incorporating EEG-Based Neurofeedback Into Online Video Lectures. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2023, 16, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglington, L.G.; Pavlik, P.I., Jr. How to Optimize Student Learning Using Student Models That Adapt Rapidly to Individual Differences. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahza, H.; Khosravi, H.; Demartini, G. Analytics of learning tactics and strategies in an online learnersourcing environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2023, 39, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Lajoie, S.P. Temporal Structures and Sequential Patterns of Self-regulated Learning Behaviors in Problem Solving with an Intelligent Tutoring System. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2022, 25, 1–14. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48695977 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lan, M.; Zhou, X. A qualitative systematic review on ai empowered self-regulated learning in higher education. npj Sci. Learn. 2025, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Z. Design and Evaluation of Trustworthy Knowledge Tracing Model for Intelligent Tutoring System. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1701–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, C.G.; Doroudi, S. Three Algorithms for Grouping Students: A Bridge Between Personalized Tutoring System Data and Classroom Pedagogy. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 843–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Ch, W.; Buenano-Fernandez, D.; Navarro, A.M.; Mera-Navarrete, A. Adaptive intelligent tutoring systems for STEM education: Analysis of the learning impact and effectiveness of personalized feedback. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Olmo-Muñoz, J.; González-Calero, J.A.; Diago, P.D.; Arnau, D.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M. Using intra-task flexibility on an intelligent tutoring system to promote arithmetic problem-solving proficiency. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 1976–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. Teaching Mathematics Integrating Intelligent Tutoring Systems: Investigating Prospective Teachers’ Concerns and TPACK. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2022, 20, 1659–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, J.; Cristea, A.I.; Zhou, Y. Sim-GAIL: A generative adversarial imitation learning approach of student modelling for intelligent tutoring systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 24369–24388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, J. The Design of Guiding and Adaptive Prompts for Intelligent Tutoring Systems and Its Effect on Students’ Mathematics Learning. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, G.; Miller, K.; Klales, A.; Milbourne, T.; Ponti, G. Ai tutoring outperforms in-class active learning: An rct introducing a novel research-based design in an authentic educational setting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Lippert, A.; Cai, Z.; Chen, S.; Frijters, J.C.; Greenberg, D.; Graesser, A.C. Patterns of Adults with Low Literacy Skills Interacting with an Intelligent Tutoring System. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Morch, A.I.; Litherland, K.T. Collaborative learning with block-based programming: Investigating human-centered artificial intelligence in education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1830–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Brusilovsky, P.; Guerra, J.; Koedinger, K.; Schunn, C. Supporting skill integration in an intelligent tutoring system for code tracing. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2023, 39, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsche, C.E.; Kongsomjit, P.; Milson, C.; Wang, W.; Ngan, C.K. Incorporating an Intelligent Tutoring System into the DiscoverOChem Learning Platform. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 3081–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Rau, M.A.; Van Veen, B.D. Development of an Intelligent Tutoring System That Assesses Internal Visualization Skills in Engineering Using Multimodal Triangulation. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau-González, P.; Serrano-Mamolar, A.; Katsigiannis, S.; Althobaiti, T.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M. Toward Automatic Tutoring of Math Word Problems in Intelligent Tutoring Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 67030–67039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Pan, Z.; Lajoie, S.P. Exploring the co-occurrence of students’ learning behaviours and reasoning processes in an intelligent tutoring system: An epistemic network analysis. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2023, 39, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, D.A.; Sonnenfeld, N.A.; Wiedbusch, M.D.; Schmorrow, S.G.; Amon, M.J.; Azevedo, R. A complex systems approach to analyzing pedagogical agents’ scaffolding of self-regulated learning within an intelligent tutoring system. Metacognition Learn. 2023, 18, 659–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Koukaras, P.; Tsalikidis, N.; Ioannidis, D.; Tjortjis, C. Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques and Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Ntozi, E.; Afentoulis, K.; Koukaras, P.; Giannopoulos, G.; Bezas, N.; Gkaidatzis, P.A.; Ioannidis, D.; Tjortjis, C.; Tzovaras, D. One Step Ahead Energy Load Forecasting: A Multi-model approach utilizing Machine and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 57th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Istanbul, Turkey, 30 August–2 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikidis, N.; Mystakidis, A.; Tjortjis, C.; Koukaras, P.; Ioannidis, D. Energy load forecasting: One-step ahead hybrid model utilizing ensembling. Computing 2024, 106, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Haq, I.; Pifarre, M.; Fraca, E. Novelty Evaluation using Sentence Embedding Models in Open-ended Cocreative Problem-solving. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 34, 1599–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Mendez, G.; Huerta-Pacheco, N.S.; Baker, R.S.; du Boulay, B. Meta-Affective Behaviour within an Intelligent Tutoring System for Mathematics. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Khosravi, H.; Laat, M.d.; Bergdahl, N.; Negrea, V.; Oxley, E.; Pham, P.; Chong, S.W.; Siemens, G. A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Stede, M. A Survey of Current Machine Learning Approaches to Student Free-Text Evaluation for Intelligent Tutoring. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 992–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Lin, X.; Zhang, X.; Ginns, P. The Personalized Learning by Interest Effect on Interest, Cognitive Load, Retention, and Transfer: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essahraui, S.; Lamaakal, I.; Maleh, Y.; El Makkaoui, K.; Filali Bouami, M.; Ouahbi, I.; Abd El-Latif, A.A.; Almousa, M.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Human Behavior Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey on Techniques, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 128379–128419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, M.; Yang, R.; Chen, J. From surface to deep learning approaches with Generative AI in higher education: An analytical framework of student agency. Stud. High. Educ. 2024, 49, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzilek, J.; Zdrahal, Z.; Vaclavek, J.; Fuglik, V.; Skocilas, J.; Wolff, A. First-Year Engineering Students’ Strategies for Taking Exams. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 583–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameni, J.S.H.; Batchakui, B.; Nkambou, R. Optimization of Information Retrieval Systems for Learning Contexts. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lv, Z. Construction of personalized learning and knowledge system of chemistry specialty via the internet of things and clustering algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 10997–11014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceddu, A.C.; Pugliese, L.; Sini, J.; Espinosa, G.R.; Amel Solouki, M.; Chiavassa, P.; Giusto, E.; Montrucchio, B.; Violante, M.; De Pace, F. A Novel Redundant Validation IoT System for Affective Learning Based on Facial Expressions and Biological Signals. Sensors 2022, 22, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, P.; Tang, X.; Xia, D.; Huang, H. NAGNet: A novel framework for real-time students’ sentiment analysis in the wisdom classroom. Concurr. Comput.-Pract. Exp. 2023, 35, e7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pado, U.; Eryilmaz, Y.; Kirschner, L. Short-Answer Grading for German: Addressing the Challenges. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 34, 1321–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, K.; Cohn, C.; Hastings, P.; Tomuro, N.; Hughes, S. Using BERT to Identify Causal Structure in Students’ Scientific Explanations. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 34, 1248–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, B.; Curry, J.H. Can ChatGPT Pass Graduate-Level Instructional Design assignments? Potential Implications of Artificial Intelligence in Education and a Call to Action. TechTrends 2024, 68, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, A.; Khosravi, H.; Sadiq, S.; Gašević, D. Incorporating AI and learning analytics to build trustworthy peer assessment systems. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 844–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Perry, A.; Lee, I. Developing and Validating the Artificial Intelligence Literacy Concept Inventory: An Instrument to Assess Artificial Intelligence Literacy among Middle School Students. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 398–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.C.; Huang, H.L.; Hwang, G.J.; Chen, M.S. Effects of Incorporating an Expert Decision-making Mechanism into Chatbots on Students? Achievement, Enjoyment, and Anxiety. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2023, 26, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkavi, R.; Karthikeyan, P.; Sheik Abdullah, A. Enhancing personalized learning with explainable AI: A chaotic particle swarm optimization based decision support system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 156, 111451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Lester, J. K-12 Education in the Age of AI: A Call to Action for K-12 AI Literacy. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, N.; Ardissono, L.; Cena, F.; Scarpinati, L.; Torta, G. An Intelligent Support System to Help Teachers Plan Field Trips. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 34, 793–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukaras, P.; Rousidis, D.; Tjortjis, C. Forecasting and Prevention Mechanisms Using Social Media in Health Care. In Advanced Computational Intelligence in Healthcare-7: Biomedical Informatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoteli, E.; Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C. Social Media Sentiment Analysis Related to COVID-19 Vaccines: Case Studies in English and Greek Language. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Maglogiannis, I., Iliadis, L., Macintyre, J., Cortez, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukaras, P.; Dimara, A.; Herrera, S.; Zangrando, N.; Krinidis, S.; Ioannidis, D.; Fraternali, P.; Tjortjis, C.; Anagnostopoulos, C.N.; Tzovaras, D. Proactive Buildings: A Prescriptive Maintenance Approach. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. AIAI 2022 IFIP WG 12.5 International Workshops; Maglogiannis, I., Iliadis, L., Macintyre, J., Cortez, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikstein, P.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, K.Z. Ceci n’est pas une école: Discourses of artificial intelligence in education through the lens of semiotic analytics. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochmar, E.; Vu, D.D.; Belfer, R.; Gupta, V.; Serban, I.V.; Pineau, J. Automated Data-Driven Generation of Personalized Pedagogical Interventions in Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ping, B. Research on Physical Education Teaching Management Based on “Internet+” Platform. Int. J. Healthc. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2025, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimdiwala, A.; Neri, R.C.; Gomez, L.M. Advancing the Design and Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Education through Continuous Improvement. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 756–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, A.; Mohammed, P.S.; Skerrit, P. Inclusive Deaf Education Enabled by Artificial Intelligence: The Path to a Solution. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 96–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.; Glazewski, K.; Jeon, M.; Jantaraweragul, K.; Hmelo-Silver, C.E.; Scribner, A.; Lee, S.; Mott, B.; Lester, J. Lessons Learned for AI Education with Elementary Students and Teachers. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunjungbiru, A.D.; Pranggono, B.; Sari, R.F.; Sanchez-Velazquez, E.; Purnamasari, P.D.; Liliana, D.Y.; Andryani, N.A.C. AI Literacy and Gender Bias: Comparative Perspectives from the UK and Indonesia. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Jiang, C.; Fang, J.; Li, Y. Understanding undergraduates’ computational thinking processes: Evidence from an integrated analysis of discourse in pair programming. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 19367–19399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copur-Gencturk, Y.; Li, J.; Atabas, S. Improving Teaching at Scale: Can AI Be Incorporated Into Professional Development to Create Interactive, Personalized Learning for Teachers? Am. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 61, 767–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Wan, X.; Daley, M.; Bai, Z. ML4STEM Professional Development Program: Enriching K-12 STEM Teaching with Machine Learning. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 185–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Wang, Q. Factors influencing pre-service special education teachers’ intention toward AI in education: Digital literacy, teacher self-efficacy, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, S.; Gaudioso, E.; de la Paz, F. Toward Embedding Robotics in Learning Environments With Support to Teachers: The IDEE Experience. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weegar, R.; Idestam-Almquist, P. Reducing Workload in Short Answer Grading Using Machine Learning. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 34, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, J.C. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education and Its Implications for Assessment. TechTrends 2024, 68, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, U.A.; Sayeed, M.S.; Fatimah Abdul Razak, S.; Yogarayan, S.; Sneesl, R. Decision-Making Framework for the Utilization of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Case Study of ChatGPT. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95368–95389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, N. Factors affecting English language high school teachers switching intention to ChatGPT: A Push-Pull-Mooring theory perspective. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 33, 1367–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.; Pauli, C.; Stebler, R.; Reusser, K.; Petko, D. Implementation of technology-supported personalized learning—Its impact on instructional quality. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 115, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnavsky, A. The Three-Stage Hierarchical Logistic Model Controlling Personalized Playback of Audio Information for Intelligent Tutoring Systems. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 2005–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouman, N.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Wasi, S. A Novel Personalized Learning Framework With Interactive e-Mentoring. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10428–10458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Liu, H.; Li, K.C.; Jia, J. For Educational Inclusiveness: Design and Implementation of an Intelligent Tutoring System for Student-Athletes Based on Self-Determination Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.K.; Raghuram, J.N.V. Gen-AI integration in higher education: Predicting intentions using SEM-ANN approach. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 17169–17209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Lima, D.A.; Oliveira, W.; Bittencourt, I.I.; Dermeval, D.; Reimers, F.; Isotani, S. Exploring Brazilian Teachers’ Perceptions and a priori Needs to Design Smart Classrooms. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 914–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez-Ayres, I.; Callejo, P.; Hombrados-Herrera, M.A.; Alario-Hoyos, C.; Delgado Kloos, C. Evaluation of LLM Tools for Feedback Generation in a Course on Concurrent Programming. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, M.; Cangelosi, A.; Weinberger, A.; Mazzoni, E.; Benassi, M.; Barbaresi, M.; Orsoni, M. Artificial intelligence and human behavioral development: A perspective on new skills and competences acquisition for the educational context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schoors, R.; Elen, J.; Raes, A.; Vanbecelaere, S.; Depaepe, F. The Charm or Chasm of Digital Personalized Learning in Education: Teachers’ Reported Use, Perceptions and Expectations. TechTrends 2023, 67, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Kang, D. Challenges and Future Directions of Medicine with Artificial Intelligence. Chin. J. Clin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2025, 32, 244–251, (In Chinese; English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Gurrib, I. New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Towards a Sustainable Multifaceted Revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aler Tubella, A.; Mora-Cantallops, M.; Nieves, J.C. How to teach responsible AI in Higher Education: Challenges and opportunities. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasseropoulos, D.P.; Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C. Exploiting Textual Information for Fake News Detection. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2022, 32, 2250058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, I.I.; Chalco, G.; Santos, J.; Fernandes, S.; Silva, J.; Batista, N.; Hutz, C.; Isotani, S. Positive Artificial Intelligence in Education (P-AIED): A Roadmap. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 34, 732–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaj, M. Ethical artificial intelligence for teaching-learning in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 17145–17167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard-Frost, B.; Brandusescu, A.; Lyons, K. The governance of artificial intelligence in Canada: Findings and opportunities from a review of 84 AI governance initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Ali, S.; Devasia, N.; DiPaola, D.; Hong, J.; Kaputsos, S.P.; Jordan, B.; Breazeal, C. AI plus Ethics Curricula for Middle School Youth: Lessons Learned from Three Project-Based Curricula. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2023, 33, 325–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowmiya, B.; Poovammal, E. A Heuristic K-Anonymity Based Privacy Preserving for Student Management Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 127, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Song, H.; Guo, L.; Li, B.; Lin, Z.; Gao, Y.; Ge, W. Phone-to-EDU: A Smart Contract-Based Framework for Comprehensive Management of GAI-Assisted Programming Courses. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 35261–35277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.M.; Hamjaya, H.S.; Shiralizade, H.; Singh, V.; Inam, R. Large Language Models’ Trustworthiness in the Light of the EU AI Act—A Systematic Mapping Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetade, K.; Zuva, T. Advancing Equitable Education with Inclusive AI to Mitigate Bias and Enhance Teacher Literacy. Educ. Process. Int. J. 2025, 14, e2025087. [Google Scholar]

- Almagharbeh, W.T.; Alharrasi, M.; Rony, M.K.K.; Kabir, S.; Ahmed, S.K.; Alrazeeni, D.M. Ethical and Institutional Readiness for Artificial Intelligence in Nursing: An Umbrella Review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulibdeh, A.; Zaidan, E.; Abulibdeh, R. Navigating the confluence of artificial intelligence and education for sustainable development in the era of industry 4.0: Challenges, opportunities, and ethical dimensions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Raimundo, R.J.G. AI, Optimization, and Human Values: Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Industry 4.0 to 5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, R.; Kuleto, V.; Gudei, S.C.D.; Lianu, C.; Lianu, C.; Ilić, M.P.; Păun, D. Artificial Intelligence Potential in Higher Education Institutions Enhanced Learning Environment in Romania and Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourqoniah, F.; Aransyah, M.F.; Riani, L.P. Thematic synthesis and future outlook in digital entrepreneurial education. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2025, 23, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.M.M.; Abdalmotalib, M.M.; Elbadawi, M.H.; Mohammed, G.T.F.; Mohamed, W.M.I.; Mohammed, F.S.B.; Salih, H.S.; Mohamed, H.O.Y. Shaping the future of medical education: A cross-sectional study on ChatGPT attitude and usage among medical students in Sudan. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, O.; Vijayalekshmi, S.; Vinoth Kumar, D. Integrating 4IR Technologies into Higher Education in South Africa: Opportunities, Challenges, and Strategies. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampasidou, M.; Goldgaber, D.; Gentimis, T.; Mandalika, A. Overcoming ‘Digital Divides’: Leveraging higher education to develop next generation digital agriculture professionals. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedi, A.; Mardiana, D.; Umiarso, U. Digital Transformation Model of Islamic Religious Education in the AI Era: A Case Study of Madrasah Aliyah in East Java, Indonesia. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 842–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, C.; Jiang, S.; Rose, C.P.; Chao, J. Exploring Teachers’ Views and Confidence in the Integration of an Artificial Intelligence Curriculum into Their Classrooms: A Case Study of Curricular Co-Design Program. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 35, 702–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigun, G.O.; Ajani, Y.A.; Enakrire, R.T. The Intelligent Libraries: Innovation for a Sustainable Knowledge System in the Fifth (5th) Industrial Revolution. Libri 2024, 74, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Ching, Y.H. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education, Part One: The Dynamic Frontier. TechTrends 2023, 67, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheb, T.; Dehghani, M.; Saheb, T. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Energy: A Contextual Topic Modeling and Content Analysis. Sustain. Comput. Informatics Syst. 2022, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Citizens’ Data Privacy in China: The State of the Art of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z. Evaluation of university student education management effect based on data augmentation and transfer learning for remote sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukaras, P.; Berberidis, C.; Tjortjis, C. A Semi-supervised Learning Approach for Complex Information Networks. In Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things; Hemanth, J., Bestak, R., Chen, J.I.Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Field | Details |

|---|---|

| Search Query | AB = ((“artificial intelligence” OR “AI” OR “machine learning” OR “intelligent tutoring system *” OR “adaptive learning system *” OR “learning analytic *”) AND (education *) AND (telecommunication * OR “5G” OR “6G” OR “internet of things” OR IoT OR “edge computing” OR “multi-access edge computing” OR MEC OR “smart campus” OR “digital infrastructure”) AND (ethic * OR equity OR fairness OR “digital divide” OR privacy OR “data governance” OR “responsible AI” OR accountability OR transparency)) AND LA = (“English”) |

| Date Range | PY = (2022 OR 2023 OR 2024 OR 2025) |

| Document Type | DT = (“ARTICLE” OR “PROCEEDINGS PAPER” OR “BOOK CHAPTER”) |

| Language | English |

| Field | Details |

|---|---|

| Search Query | ABS ((“artificial intelligence” OR “AI” OR “machine learning” OR “intelligent tutoring system *” OR “adaptive learning system *” OR “learning analytic *” ) AND (education *) AND (telecommunication * OR “5G” OR “6G” OR “internet of things” OR IoT OR “edge computing” OR “multi-access edge computing” OR MEC OR “smart campus” OR “digital infrastructure”) AND (ethic * OR equity OR fairness OR “digital divide” OR privacy OR “data governance” OR “responsible AI” OR accountability OR transparency)) |

| Publication Year Range | PUBYEAR > 2021 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 |

| Keywords | education * AND “artificial intelligence” AND telecommunications AND ethic * |

| Limitations | LIMIT-TO(SRCTYPE, “j”) AND LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ch”) OR LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “cp”)) AND LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE, “English”) AND LIMIT-TO(PUBSTAGE, “final”) AND (LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “COMP”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “SOCI”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “PSYC”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “ARTS“) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “DECI”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “MULT”) OR LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “ENGI”)) |

| RQ | Section | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | Section 3, Section 4 and Section 7 | Field deployments and reviews of 5G/eMEC campuses, IoT-based smart learning environments, XR/metaverse pilots, ALS/ITS platforms, AI-driven assessment and administration, and inclusive/teacher-PD initiatives show that ALS, ITS, AI-driven assessment, XR/VR/AR, administrative analytics, and inclusive/PD tools are the dominant AIEd applications. They depend on low-latency 5G access, IoT telemetry, and MEC/eMEC placement, motivating the AITE reference architecture that couples telecom stacks with pedagogical functions. |

| RQ2 | Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4 and Section 4.5, Section 5.1 and Section 5.2 | Multiple ALS/ITS, GenAI/chatbot, and EDM studies, together with AI-based assessment and campus-management systems, report improved engagement, diagnostic precision, short-term performance, reduced grading, and administrative workload, and in some cases lower anxiety, provided that interventions are aligned with curricular goals and supported by timely feedback and adequate telecom QoS. |

| RQ3 | Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, Section 6.1, Section 6.2, Section 6.3 and Section 6.4 and Section 7.2 | AITE introduces risks around data privacy and security (dense IoT and continuous device–edge streaming), algorithmic bias in ALS/ITS and assessment, academic integrity and over-reliance on GenAI, and integration tensions related to teacher autonomy and institutional capacity. Effective controls emphasise privacy-by-design (local/edge processing, data minimisation, encryption), zero-trust gateways, explainable and trustworthy models, ethics and AI literacy curricula, and alignment with evolving regulatory frameworks. |

| RQ4 | Section 4.6, Section 5.3, Section 6.4, Section 7, Section 8 and Section 9.3 | The evidence base is dominated by short-term, single-site pilots and quasi-experiments with heterogeneous performance metrics and limited co-recording of telecom KPIs. This constrains external validity and cross-study comparability. This review identifies the need for longitudinal and multi-site, network-aware evaluations, standardised outcome and network reporting, cross-layer explainability (from models to MEC orchestration), and compliance-by-design for privacy, security, and auditability. |

| RQ5 | Section 3.1, Section 3.5, Section 4.4 and Section 4.5, Section Teacher Training, Section 6.3, Section 7 and Section 8 | Teachers, administrators, and local stakeholders emerge as co-designers and stewards of AIEd. AI-augmented administration, ITS, and PD programmes can relieve routine burden and widen inclusion when educators retain goal-setting and interpretive authority, when PD builds AI/data/ethics literacies, and when policies and infrastructure explicitly target connectivity, affordability, device access, and cultural relevance in underserved regions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Koukaras, C.; Stavrinides, S.G.; Hatzikraniotis, E.; Mitsiaki, M.; Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C. Navigating the Future of Education: A Review on Telecommunications and AI Technologies, Ethical Implications, and Equity Challenges. Telecom 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010002

Koukaras C, Stavrinides SG, Hatzikraniotis E, Mitsiaki M, Koukaras P, Tjortjis C. Navigating the Future of Education: A Review on Telecommunications and AI Technologies, Ethical Implications, and Equity Challenges. Telecom. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoukaras, Christos, Stavros G. Stavrinides, Euripides Hatzikraniotis, Maria Mitsiaki, Paraskevas Koukaras, and Christos Tjortjis. 2026. "Navigating the Future of Education: A Review on Telecommunications and AI Technologies, Ethical Implications, and Equity Challenges" Telecom 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010002

APA StyleKoukaras, C., Stavrinides, S. G., Hatzikraniotis, E., Mitsiaki, M., Koukaras, P., & Tjortjis, C. (2026). Navigating the Future of Education: A Review on Telecommunications and AI Technologies, Ethical Implications, and Equity Challenges. Telecom, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom7010002