Abstract

When operating in the marine environment, floating offshore wind turbines (FOWTs) are subjected to various inflow conditions such as wind, waves, and currents. To investigate the effects of complex inflow conditions on offshore wind farms, an integrated fluid-structure interaction computational and coupled dynamic analysis method for FOWTs is employed. An aero-hydro-servo-elastic coupled analysis model of the NREL 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbine array based on the OC4-DeepCwind platform is established. The study examines the variations in power generation, platform motion, structural loads, and flow field distribution of the FOWT array under different wave incident angles and yaw angles of the first column turbines. The results indicate that the changes in power generation, platform motion, and flow field distribution of the wind farm are significantly influenced by the yaw angle. The maximum tower top yaw bearing torque and the tower base Y-direction bending moment of the wind turbines undergo significant changes with the increase in the angle between wind and wave directions. The study reveals the mechanism of power generation and load variation during yaw control of the FOWT array under misaligned wind and wave conditions, providing a theoretical basis for the future development of offshore floating wind farms.

1. Introduction

Wind-Wave Misalignment (i.e., the inconsistency between wind and wave directions) is a prevalent phenomenon in the marine environment. Traditional marine engineering design often assumes collinear wind and waves by default. However, in actual marine environments, due to differences in atmospheric circulation, topography, and wave propagation characteristics, the phenomenon of non-collinear wind and waves is widespread [1]. Consequently, wind-wave misalignment poses comprehensive technical challenges for offshore wind power, especially for FOWTs advancing into deeper waters, spanning from structural safety and control stability to power generation revenue [2].

In recent years, global studies on FOWTs operating under complex sea conditions scenarios have primarily centered on two key aspects of a single FOWT: the motion behavior of its floating platform and the structural loading on its mooring system. Regarding platform motion response, Lamei et al. [3] proposed an analytical method and numerical solution for the coupled aerodynamic-elastic and hydro-elastic responses of floating offshore wind turbines with arbitrary shapes under combined wind and wave loads. By integrating the finite element method for structural analysis, the obtained results generally align with both laboratory measurements and theoretical predictions. Yu et al. [4] conducted a series of tests on the UMaine VolturnUS-S semi-submersible platform and compared its dynamic responses with those of a scaled model tested in the COAST Laboratory Ocean Basin at the University of Plymouth. Their work particularly highlighted the uncertainties associated with numerical models in simulating complex wave-structure interactions. Aboutalebi et al. [5] designed a substructure for a semi-submersible wind turbine by integrating Oscillating Water Columns into the substructure. This approach can significantly enhance damping effects, thereby effectively reducing the heave, roll, and pitch motions of the floating platform. Liu et al. [6] studied the DTU 10 MW semi-submersible wind turbine, calculating aerodynamic loads and wave loads based on Blade Element Momentum (BEM) theory and random wave theory, respectively. They analyzed the impact of wind-wave misalignment on platform motion under scenarios of fixed wave direction with varying wind direction, and fixed wind direction with varying wave direction. Concerning structural loads of the mooring system, Riefolo et al. [7] conducted time-domain and frequency-domain analyses on a Spar-type wind turbine under a wind-wave misalignment angle of 30°. Their study revealed that the most probable maximum tension in the mooring system is influenced by the wind-wave misalignment angle. Mohammad et al. [8] investigated a more flexible mooring system that allows for self-adjusting configurations. The study shows that such a layout can adapt to changes in wind speed and direction, thereby boosting energy production, though it also increases the structural loads on the mooring system. Li et al. [9] employed a coupled CFD-FEM model to investigate the response characteristics of a floating platform and its mooring system under abnormal wave conditions in a parked state. The results indicate that abnormal waves can significantly amplify both the platform motions and the mooring tensions.

FOWTs are typically deployed in clusters as wind farms to maximize wind energy utilization efficiency [10]. However, downstream turbines within a wind farm are affected by the wake effects of upstream turbines, leading to reduced inflow quality, which not only causes significant power output losses but also increases fatigue loads [11,12,13]. In recent years, scholars have proposed various active control strategies, primarily including cooperative thrust distribution control [14], active yaw control, and rotor plane tilt control [15]. Among these, active yaw control is the most efficient and practical method due to its relatively low engineering implementation difficulty and high wake deflection efficiency. Fleming et al. [16] from NREL conducted field experiments on two turbines in the 150 MW Rudong offshore wind farm in Jiangsu province. They found that with small turbine spacing, active yaw control of the upstream turbine effectively increased the total array power output under most inflow wind directions. Therefore, yaw control is recognized as one of the effective wake steering strategies [17,18]. Wang et al. [19] used OpenFOAM to numerically simulate various yaw control and staggered layout schemes for wind turbine arrays. They discovered that integrating yaw control with a staggered turbine layout is capable of substantially enhancing the wind farm’s total power output. Bai et al. [20] employed the FAST-OrcaFlex program to analyze the influence of yaw operation on the motion response and mooring line loads of a semi-submersible wind turbine. They found that yawing significantly affects the platform surge and pitch motions and has a noticeable impact on mooring loads. Yuan et al. [21] studied the aerodynamic loads and platform motion of a floating wind turbine under dynamic yaw conditions based on a free vortex wake method. They found that there is a positive correlation between the oscillation amplitude of aerodynamic loads and the active yaw frequency. Furthermore, how dynamic yaw influences platform motion can be simplified into additional hydrostatic stiffness and damping. In practice, both wind-wave misalignment and yaw control are factors that need to be considered simultaneously during the operation of FOWTs in the marine environment. However, the aforementioned research often treats wind-wave misalignment and yaw control as independent factors, neglecting their interaction. Furthermore, existing studies are primarily limited to single FOWT, and research on arrays of FOWTs requires further in-depth investigation.

Hence, this study focuses on investigating how active yaw control under misaligned wind-wave conditions impacts a FOWT array. Taking an array of NREL 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbines as the research object, an aero-hydro-servo-elastic coupled analysis model for the array is developed based on BEM theory and potential flow theory. An analysis of the wind farm’s performance under diverse operating conditions then elucidates the mechanisms through which misaligned wind-wave angles and yaw angles affect the FOWT array’s power generation, dynamic behavior, structural loads, and flow field.

2. Numerical Simulation Method

The simulation tool leveraged in this research is FAST.Farm (v4.1.1) [22], an NREL-developed open-source platform for wind farm simulations. Classified as a medium-fidelity multi-physics engineering tool, it focuses on simulating turbine wake interactions in large wind farms and incorporates the physics of atmospheric boundary layer flow and wake advection.

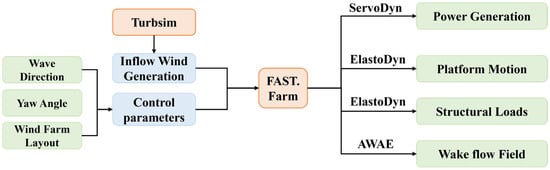

The workflow of this study is illustrated in Figure 1. First, a numerical wind field is generated using Turbsim (v2.00.07a-bjj). Then, the offshore wind farm model under investigation is established within FAST.Farm by inputting various combinations of wave incident angles and the yaw angles of the first column of wind turbines, along with the wind farm layout configuration. The main driver program of FAST.Farm calls submodules from OpenFAST to simulate individual wind turbines. The AeroDyn module calculates the aerodynamic loads on the rotor based on the displacement and velocity of the blade elements’ motion. The HydroDyn module computes the hydrodynamic loads based on the displacement and velocity components of the floating structure. The ServoDyn module provides control commands based on the current structural accelerations and reaction force, finally calculating the generator’s electrical power output. The ElastoDyn module primarily computes the overall structural motions, including displacements, velocities, and accelerations, and calculates the structural loads based on the aerodynamic loads, hydrodynamic loads, and control commands provided by the previous three modules.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the study workflow.

Furthermore, to address other physical effects across the entire wind farm, the Wake Dynamics module within FAST.Farm is employed to handle wake advection, deflection, meandering, deficit, and near-wake correction. The AWAE (Ambient Wind and Array Effects) module processes the ambient wind field and wind turbine array effects, identifying and merging wake deficit regions between different turbines. The theories involved are introduced below.

2.1. Aerodynamic Theory for Numerical Simulation of Wind Turbines

2.1.1. Turbulent Wind Field Generation

Wind is a common natural phenomenon, but its characteristics significantly impact many engineering fields, particularly wind power generation. Due to factors such as terrain and atmospheric conditions, wind propagation exhibits highly stochastic and non-linear characteristics, making accurate prediction of wind behavior extremely challenging. To better describe and simulate the random nature of wind fields, researchers have proposed the concept of wind spectra. A wind spectrum is a mathematical model that describes the distribution of wind speed fluctuation energy across different frequencies, providing an essential quantitative tool for the statistical characteristics of wind fields. Common wind spectrum models include Kaimal, Davenport, Karman, and Panofsky. The Kaimal spectrum [23] not only accurately describes the frequency characteristics of wind speed fluctuations but also accounts for the influence of height on wind speed distribution, giving it distinct advantages. Therefore, this study adopts the Kaimal spectrum for subsequent calculations and analysis. The Kaimal spectrum can be expressed as follows:

where is the power spectral density of velocity component, is the frequency, is the standard deviation of the wind speed, is the turbulent integral length, is the mean wind speed at the hub height.

2.1.2. Aerodynamic Load Calculation

For floating wind turbines, wind loads significantly impact their stability and power output due to the unique marine environment. Therefore, accurately calculating wind loads is crucial for assessing the performance and safety of FOWTs. The BEM Theory [24,25] is the primary method for calculating the aerodynamic loads of wind turbines and is widely used in the load analysis of FOWTs. This theory divides the blade into multiple independent blade elements along the spanwise direction. The total aerodynamic force and moment on the entire blade are obtained by calculating the aerodynamic forces on each blade element and integrating them.

By integrating along the blade span, the total force and total moment on the entire blade can be obtained, calculated using the following formulas:

where is the air density, is the relative wind speed at the blade element section, is the inflow angle, and denote the number of blades and chord length, respectively, is the distance from the blade element to the hub center, and are the lift and drag coefficients, and denotes the radial length of the blade element.

2.1.3. Curled Wake Model

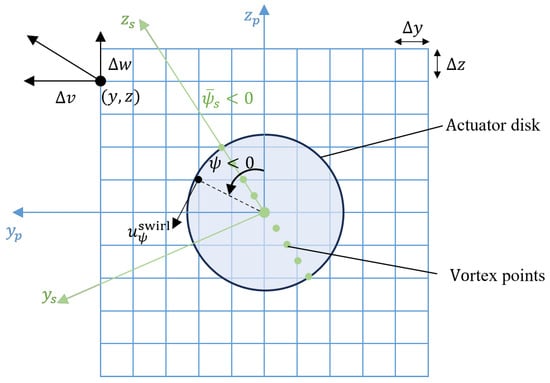

Under yawed or tilted operating conditions of wind turbines, the wake curling effect is crucial for predicting downstream flow field structures and turbine loads. The Curled Wake Model [26] achieves efficient simulation of dynamic wake evolution by improving the mathematical formulation of the original quasi-steady model. The model is fundamentally based on solving the modified Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, incorporating an eddy viscosity closure to account for turbulence effects, and utilizing a Lagrangian-Eulerian hybrid approach to simulate wake convection. Figure 2 shows the schematic of the grid at the actuator disk plane. Although the modified RANS equations may lose some accuracy inherently [27,28], the Curled Wake Model ensures that the calculation results meet engineering requirements, while offering rapidity and broad applicability.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the Cartesian coordinate system for velocity components at the actuator disk plane. (The green color represents the local coordinate system of the infinite vortices tilted based on the azimuthal angle).

In the Curled Wake Model, the wake region below the wind turbine is asymmetric. Each plane consists of regular grid points along the and directions, and the axial flow equations are formulated in a Cartesian coordinate system, as shown below:

where represent the three components of the time-filtered velocity, and is the eddy viscosity coefficient. Under the assumption of the thin shear layer approximation, the gradient terms in the x-direction are neglected.

The eddy viscosity coefficient [29] is considered the sum of contributions from the wake shear layer and the ambient turbulence, calculated as follows:

where is the scaling factor, and denote the eddy viscosity coefficients contributed by the ambient turbulence and wake shear layer, respectively. Besides, a minimum viscosity term is also introduced in the model to represent ambient viscosity.

The initial wake plane is generated at the rotor position, and its deficit is determined based on the time-filtered thrust coefficient , which is calculated from the average azimuthal value of the thrust force over the different blades. The total thrust coefficient is obtained by appropriately radially weighting and integrating the local thrust coefficient The initial wake of the Curled Wake Model includes both axial and cross-flow components. The cross-flow component is a product of the joint action between wake rotation and the induced velocity associated with the curled wake. For low thrust scenarios, specifically when , the initial induced velocity is given by the following expression:

In this equation, refers to the radii along the same streamline at the rotor, is time-filtered relative wind speed averaged across the rotor disk, is a near-wake tuning constant, and denote the radii at the wake region, calculated as follows:

where is the radially dependent induction, .

The lateral and vertical induced velocities of the first wake plane are calculated using the Biot-Savart law:

where is the turbine radius, is the radial length, is the vertical coordinate component based on the azimuthal angle (see Figure 2), , , and is the regularization parameter.

The circulation is computed as

where is the skew angle.

2.2. Wave Theory for Numerical Simulation of Floating Wind Turbines

2.2.1. Random Wave Theory

Waves in the marine environment are typically composed of multiple random linear waves superimposed. To accurately describe these complex wave characteristics, researchers developed the concept of the wave spectrum. The spectral density of a wave spectrum is a function of frequency, reflecting the distribution of wave energy across different frequencies. In marine engineering simulations, regular waves and irregular waves are commonly used to simulate actual sea states, where irregular waves are primarily generated based on various wave spectrum models.

The JONSWAP spectrum [30] originated from systematic observations in the “Joint North Sea Wave Project” and is particularly suitable for describing the process of wind-sea development. It can accurately simulate marine environments characterized by strong winds and irregular waves. It is highly important for the design and assessment of offshore wind farms as it provides a relatively realistic model of ocean waves. Therefore, this paper adopts the JONSWAP spectrum to generate irregular waves. Its expression is as follows:

where and are constants, representing the scale parameter and the acceleration due to gravity, respectively, is the wave angular frequency, is the shape parameter, is the peak wave angular frequency, is peak enhancement factor, and is the spectral width parameter. When , . When , .

2.2.2. Morison Equation

Morison Equation [31] is a key tool for calculating wave loads on small-scale marine structures. This Equation finds particular application in scenarios where the ratio of the structure’s characteristic length (denoted as ) to the incident wavelength () falls below 0.15. In such cases, the viscous effects of waves and the influence of fluid potential flow become significant, rendering traditional potential flow theory inadequate. This equation, proposed by Morison et al., decomposes the wave load into an inertial force component and a drag force component. The inertial force bears a direct relation to the local fluid acceleration, whereas the drag force exhibits proportionality to the square of the fluid velocity. Such a decomposition of forces endows the equation with the capability to comprehensively characterize the wave-structure interaction, as shown below:

where is the inertial force acting on the structure, while is its drag force, denotes the water density, the coefficients , , and correspond to the inertia coefficient, added mass coefficient, and drag coefficient, respectively, (velocity) and (acceleration) are the respective components of the water particle’s motion, (velocity) and (acceleration) represent the structure’s motion components.

2.2.3. Three-Dimensional Potential Flow Theory

When the ratio of the characteristic length of the structure to the incident wavelength exceeds 0.15, the incident wave will produce significant diffraction and reflection phenomena. Hydrodynamic calculations are then performed based on three-dimensional potential flow theory. The wave velocity potential formula under these conditions is as follows:

where , , and are the velocity potential of the incident wave, the diffracted wave, and the radiated wave, respectively. Each wave velocity potential satisfies the following continuity equation and boundary conditions:

where is the wave angular frequency, is the unit outward normal vector on the body surface, and .

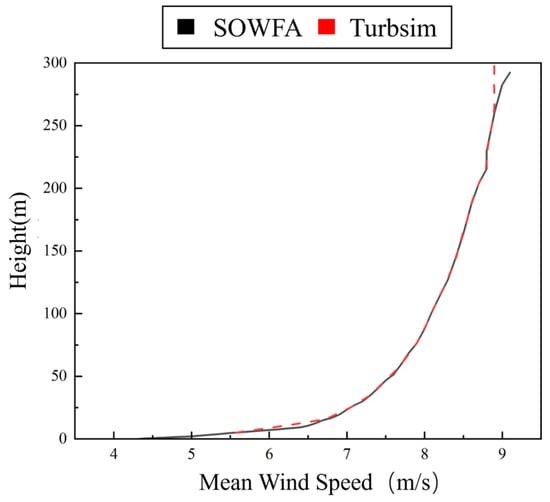

2.3. High-Fidelity Results Validation

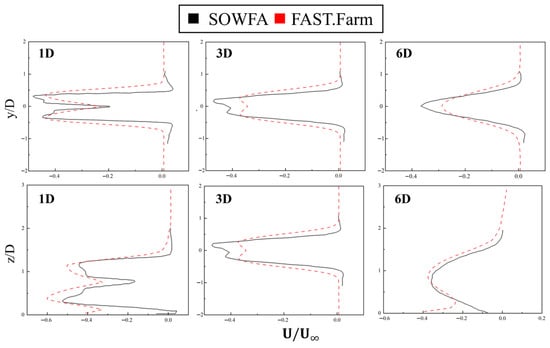

To validate the accuracy of the simulation results, a comparative verification for the wake performance and dynamic response of a FOWT was conducted between the outputs from FAST.Farm and high-fidelity Large Eddy Simulation (LES) data—with the latter generated following the methodology described in Carmo et al. [32]. In their work, Carmo et al. generated the background wind field by simulating the precursor atmospheric boundary layer via SOWFA, which featured an 8 m/s mean wind speed at the hub height. Additionally, the surface roughness height (Z0) was determined using the Charnock model (). For high-fidelity validation, the wake effects of a wind turbine under atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) inflow are modeled by coupling OpenFAST into SOWFA for FOWT simulations. In contrast, the turbulent inflow in FAST.Farm was generated using TurbSim, based on the Kaimal spectrum and the Normal Turbulence Model as specified in the IEC standard. For the comparison of undisturbed wind speed profiles, the result computed by FAST.Farm shows good agreement with that validated by SOWFA, please refer to Figure A1 in Appendix A. As shown in Figure 3, although the thin shear layer assumption and near-wake corrections in FAST.Farm may lead to a reduction in accuracy, as discussed in Section 2.1.3, which inevitably leads to discrepancies compared to the SOWFA results, we find that the overall trend of the wake deficit at the turbine hub height in the far-wake region maintains good agreement. This consistency is precisely the focus of our investigation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the mean velocity deficit between FAST.Farm and literature results at different streamwise distances for the horizontal plane at hub height (top) and vertical cross-section at hub height (bottom).

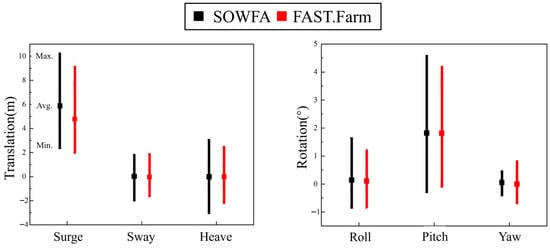

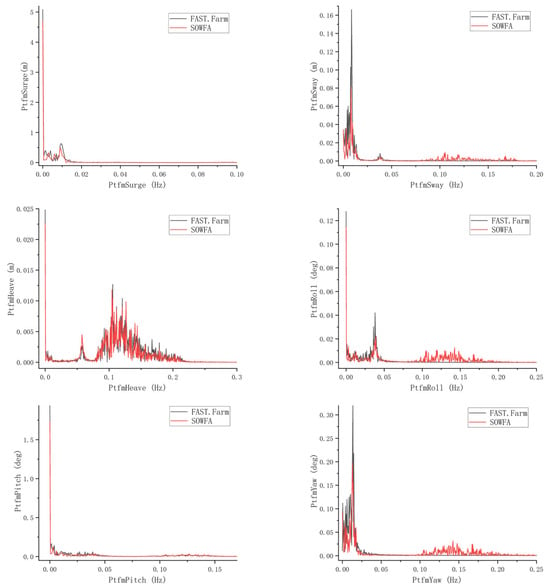

For the validation, the same wave conditions as those in the comparative literature were utilized, specifically irregular waves generated via the JONSWAP spectrum. The significant wave height was set to 8.0 m, the peak period to 14.0 s, and the wave propagation direction was defined as 30° with respect to the wind direction. As shown in Figure 4, the platform motions exhibit good agreement, confirming the accuracy of the numerical simulation method. The spectral comparison of platform motion and structural loads also shows good agreement, as detailed in Figure A2 and Figure A3 of Appendix A.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the platform motion between FAST.Farm and literature results.

3. Case Studies

3.1. NREL 5 MW Semi-Submersible Wind Turbine Array

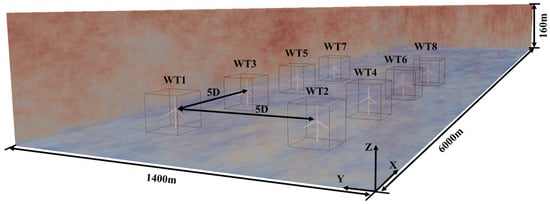

This study utilizes an array of NREL 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbines as the research subject. Figure 5 shows a 3D schematic of the FOWT array. Specifically, for each wind turbine, the upper wind turbine is the 5 MW reference wind turbine developed by NREL, while the lower floating platform is the OC4-DeepCwind platform. Detailed technical parameters are listed in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the floating wind turbine array.

Table 1.

Parameters of NREL 5 MW_Baseline wind turbine.

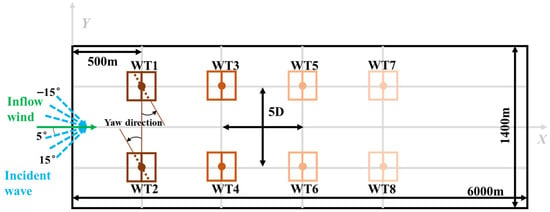

Figure 6 provides the specific schematic of the FOWT array layout. Both the wave incident angle and the yaw angle are defined as positive in the counterclockwise direction. The FOWT array consists of eight NREL 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbines, arranged symmetrically along the centerline of the computational domain. The streamwise and spanwise spacing between the turbines are both 5D. Static yaw control was implemented solely by setting a fixed yaw angle for the first column of wind turbines. Since this study focuses only on operating conditions below the rated wind speed, power generation control was achieved exclusively through the generator-torque controller to maximize energy capture efficiency, with no blade-pitch control applied.

Figure 6.

Floating offshore wind farm layout. (The colored box represents the high-resolution domain, while the black rectangle denotes the low-resolution domain. The inflow wind is indicated by the green arrow, and the wave incidence angle is shown by the blue arrow).

To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, FAST.Farm uses low-resolution domains to simulate wake meandering and merging processes and high-resolution domains for each wind turbine to calculate load and displacement precisely. The low-resolution domain is represented by the black rectangle in the figure, and the high-resolution domains are depicted as colored boxes centered on the wind turbine hubs. The dimensions of the low-resolution domain are ×× = 6000 m × 1400 m × 160 m, with a time resolution of Each high-resolution domain has dimensions of ×× = 170 m × 160 m × 160 m, is positioned 80 m upstream of each respective wind turbine, and has a time resolution of .

3.2. Case Setup

Table 2 presents the relevant parameters for the FOWT array simulation. The mean wind speed of the turbulent wind, together with the corresponding significant wave height and peak period, is set in accordance with the design load conditions for the Gulf of Maine region specified in the LIFES50+ report [33]. In this study, since the total power increase under yawed conditions is more pronounced at low wind speeds [34], the wind speed is set to 7.1 m/s, and the turbulence intensity is set to 0.05. Table 2 also lists the 36 combined operational cases. The simulation time for each case in FAST.Farm is 1200 s. To avoid the influence of transient effects, data reading begins from the time step at 200 s after the simulation starts.

Table 2.

Floating turbine array simulation setup.

According to research by Archer et al. [35], when the incoming wind direction is perfectly aligned with the wind turbine array, at least three wind turbines are required to achieve a statistically significant total power increase when applying yaw control to the wind farm. Therefore, this study opts to arrange four wind turbines in a single row. Furthermore, the spacing between turbines significantly impacts the power generation and lifespan of downstream turbines. Hence, the streamwise and spanwise spacing are both selected as 5 rotor diameters (5D). Generally, an angle exists between wind and waves under any wind speed and sea state, with smaller angles at higher wind speeds and larger angles at lower wind speeds [36]. Analysis of ocean data indicates that when incoming wind and waves propagate from different directions, the misalignment angle between them typically concentrates between 0° and 90°, and the frequency of wind-wave misalignment angles exceeding 60° is less than 5% [37]. Since this study considers both wind-wave misalignment and yaw control simultaneously, and the yaw angle of upstream turbines affects the inflow wind direction for downstream turbines (thus affecting the wind-wave misalignment angle), the range of wave incident angles considered is limited to small variations from 5° to 15°. The range for the active yaw control angles is from 0° to 30°, in increments of 5°.

To quantitatively assess the differences in the wind turbine response results, this paper uses the percentage difference [38] between cases for comparison, calculated using the following formula:

where is the percentage difference of the variable, is the absolute value of the data from the baseline case with aligned wind-wave condition and no yaw, and is the absolute value of the data from the case with misaligned wind-wave conditions and active yaw control, the time-averaged values are used for mean analysis.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Power Generation

After yaw control is applied to the leading wind turbines in an array, the projected frontal area of the rotor is reduced, leading to a decrease in power generation. In reality, the active yaw action itself also consumes power, further increasing the power deficit. However, according to literature [39], the power consumed by dynamic yaw control accounts for only about 1% of the generated power. Therefore, the energy consumption associated with the static yaw control strategy adopted in this study is considered negligible.

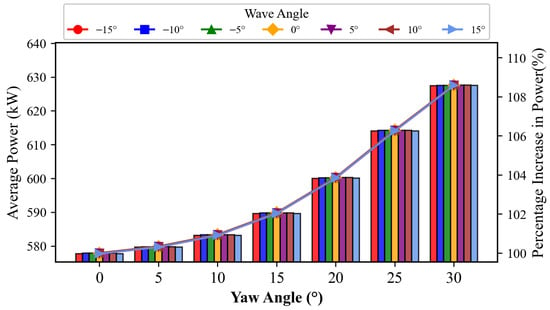

Figure 7 presents a bar chart showing the average power generation of all eight turbines in the array under different operational cases, along with the curve of percentage difference variation. It can be observed from the figure that all the differently colored lines almost overlap. For the same yaw angle, the average power generation of the entire array is nearly identical across different wave incident angles, indicating that the influence of varying wave incident angles on the overall average power output is very weak.

Figure 7.

Average power generation and percentage difference across the entire wind farm under different yaw angles and wave incidence angles.

From an analysis of the global trend, the entire array’s average power generation rises as the yaw angle increases. When the yaw angle reaches 30°, the average increase in power generation is about 8.6%. This is because the increased yaw angle enhances the positive benefit of wake recovery, thereby improving the power output of downstream wind turbines and consequently increasing the total power of the entire array.

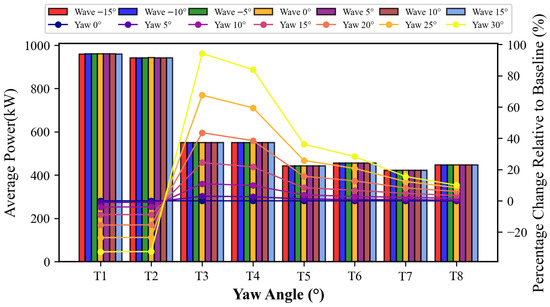

To gain deeper insight into the patterns of change in the average power generation of the entire wind farm, the average power output of each of the eight turbines under different operational cases was analyzed individually. Figure 8 presents bar charts of the average power for each turbine under different cases, along with the corresponding percentage difference curves. It is important to note that these bar charts reflect the average power generation across all yaw cases for a given wave incident angle, while the line graph represents the percentage difference between the average power of the current turbine under the current yaw case (averaged across all wave incident angles) and its average power under the baseline case.

Figure 8.

Average power generation and percentage difference of each wind turbine under different yaw angles and wave incidence angles.

From the bar chart, it can be observed that under the same conditions, the average power of the leading turbine T1 in the first column is slightly higher than that of T2. However, the average power of the downstream turbines following T2 gradually becomes greater compared to those following T1 as the streamwise distance increases. This occurs because when both leading turbines in the first column are yawed counterclockwise simultaneously, and since the two columns are not far apart, T2 is likely situated at the edge of the deflected wake region of T1. With increasing streamwise distance, wake mixing effects downstream of the leading turbines lead to faster wake recovery in the lower flow field. Consequently, the power output of the three downstream turbines in the lower section becomes higher than that of the turbines in the upper section.

From the line graph, it can be seen that as the yaw angle increases, the power of the leading turbines decreases, which aligns with the fundamental principle of yaw control. The skew angle of the wake increases significantly with the yaw angle, thereby steering the wake away from the second column of turbines. This shifts the downstream turbines from a state of full wake overlap to one of partial wake overlap, allowing high-speed flow from the other side to reach the rotors of the downstream turbines and ultimately increasing their power output. Furthermore, as shown in the line graph, when the yaw angle increases, the increase in power output for the three downstream turbines in the upper section is more pronounced than for the three turbines at the same streamwise position in the lower section. This is likely because, compared to the upper turbines, the lower turbines are influenced not only by the wake of their immediate upstream turbine but also by the deflected wake from the upper turbines.

4.2. Platform Motion

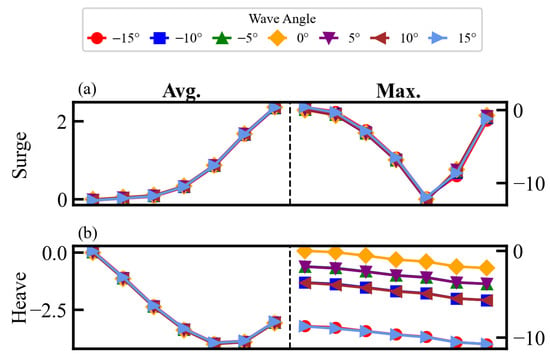

The motion characteristics of the platform play a pivotal role in investigating the stability of FOWTs. Given the variability of wind-wave misalignment, the structural symmetry of the floating platform, and the inherent traits of the wind turbine, the surge, heave, and pitch motions of the floating platform are chosen for detailed analysis. This study investigates the mechanisms of these motions under active yaw control of the first column wind turbine under misaligned wind and wave conditions. Figure 9 shows the average and maximum values of platform motion for the whole wind farm under different operating conditions.

Figure 9.

Percentage difference of average and maximum platform motion for 8 wind turbines under different yaw angles and wave incidence angles. (a) Surge; (b) Heave; (c) Pitch.

From Figure 9a, it can be observed that, regardless of changes in the wave incident angle, the average surge motion increases slightly as the yaw angle increases. At the same time, the maximum surge motion exhibits a U-shaped trend with the increase in yaw angle.

From Figure 9b, it is apparent that the percentage difference in the average heave motion continuously decreases as the yaw angle experiences a small increase from 0°, generally showing a clear U-shaped trend. Specifically, when the yaw angle increases from 5° to 20°, the percentage difference in the average heave motion gradually decreases, with the lowest point approaching −4%. However, the percentage difference in the average heave motion begins to rise again as the yaw angle continues to increase. This is because the increase in the yaw angle leads to both a reduction in the vertical component of the wind load and an increase in the vertical component of the wave load. As the wave incident angle increases, the maximum heave motion gradually decreases, especially when the wave incident angle is 15°, where the maximum heave motion is reduced by approximately 10%. This is because, as the wave incident angle increases, the waves no longer strike the wind turbine head-on but act on it at an angle, leading to a reduction in the vertical component of the wave force and an increase in the lateral component, thereby reducing the amplitude of the heave motion. Since the DeepCwind floating platform is a semi-submersible type, the platform structure is relatively symmetrical, thus the magnitude of heave motion is largely unaffected by the yaw angle. Therefore, the percentage difference in the maximum heave motion changes very little when the yaw angle increases.

From Figure 9c, it can be observed that the average pitch motion of the platform increases with the yaw angle, but the magnitude of change is significantly greater compared to the surge motion, with an increase of up to approximately 4%. Additionally, it can be noted that the variation pattern of pitch motion is similar to that of surge motion, and the wave incident angle has a relatively minor influence on the platform motion in these two directions. However, the extreme value of the maximum pitch motion occurs at a larger yaw angle, indicating that the maximum pitch motion responds more slowly to changes in the yaw angle.

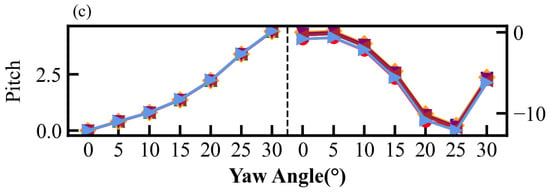

To further investigate the motion patterns of individual wind turbines in the wind farm under different operating conditions, four turbines on the upper side—T1, T3, T5, and T7 were selected for analysis. Since this study only considers scenarios where the first column wind turbines yaw counterclockwise, yaw angles of 10°, 20°, and 30°, along with wave incident angles of −5°, −10°, and −20°, were chosen as the cases with the most significant angular differences. Figure 10 presents scatter plots of the percentage differences between the average and maximum platform motions for the four turbines under these conditions.

Figure 10.

Percentage difference in platform motion: average (left) vs. maximum (right) values across different operating conditions. (a) T1 Surge; (b) T3 Surge; (c) T5 Surge; (d) T7 Surge; (e) T1 Heave; (f) T3 Heave; (g) T5 Heave; (h) T7 Heave; (i) T1 Pitch; (j) T3 Pitch; (k) T5 Pitch; (l) T7 Pitch.

Figure 10a–d show the percentage differences in the average and maximum surge motions of the four turbines under different operating conditions. It is apparent that, when the yaw angle increases, the average surge motion of T1 decreases significantly. This is owing to the rotor’s wind-facing area of T1 gradually reduces with increasing yaw angle, leading to a corresponding decrease in the longitudinal component and thus a reduction in the amplitude of the surge motion. In contrast, the average surge motions of the downstream turbines T3, T5, and T7 increase with the yaw angle, which may be attributed to the faster wake recovery downstream caused by the yawing of the first column turbine. Furthermore, when combined with the observations from Figure 9a, it is evident that the increase in surge motion for the downstream three turbines outweighs the decrease for the first column turbine, resulting in an overall positive correlation between the average surge motion of the entire farm and the yaw angle. Meanwhile, the trend in the maximum surge motion of the upstream turbine generally aligns with that of its average value. For the downstream turbines, however, the influence of the first column turbine’s yaw control on their platform motions diminishes with increasing streamwise distance. At this point, the effect of the wave incident angle becomes more apparent, though its impact magnitude is only about 2%.

Figure 10e–h display the percentage differences in the average and maximum heave motions of the four turbines under different operating conditions. The average heave motion of T1 decreases significantly with increasing yaw angle, while the average heave motions of T3, T5, and T7 fluctuate with changes in the yaw angle, with the amplitude of these fluctuations gradually diminishing as the streamwise distance increases. This is due to the changes in downstream wake velocity and deflection direction caused by the active yawing of the first column turbine. However, due to the symmetric characteristics of the floating platform, the heave motion of the downstream turbines is less affected by the yaw angle. Additionally, it can be noted that the maximum heave motions of all four turbines decrease noticeably as the wave incident angle increases, with a variation magnitude of up to 10%. This finding is generally consistent with the principles analyzed in Figure 9b.

Figure 10i–l illustrate the percentage differences in the average and maximum pitch motions of the four turbines under different operating conditions. The variation pattern of pitch motion is similar to that of surge motion. When combined with the observations from Figure 9c, it is evident that the increase in pitch motion for the downstream three turbines outweighs the decrease for the first column turbine as the yaw angle increases, leading to an overall positive correlation between the average pitch motion of the entire farm and the yaw angle.

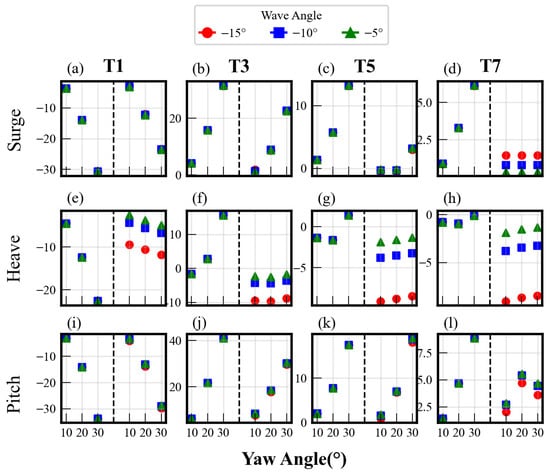

4.3. Structural Loads

The average value of structural loads is related to the structural stability, the maximum value represents the ultimate load the structure can withstand, and the standard deviation reflects the structural fatigue damage, serving as an important indicator for assessing the structural health of wind turbines. Based on this, key loads at three locations—the blade root axial shear force, the tower top yaw bearing torque, and the tower base Y-direction bending moment are analyzed. Since the total wave energy remains constant, increasing the wave incidence angle does not noticeably affect the mean structural loads, the mean values increase mainly with the yaw angle. Therefore, this paper focuses on analyzing the variation patterns of the maximum values and standard deviations. Figure 11 presents the percentage difference curves of the maximum and standard deviation of the blade root axial shear force, tower top yaw bearing torque, and tower base Y-direction bending moment under different yaw angles and wave incident angles.

Figure 11.

Percentage differences in the maximum and standard deviation of structural loads under different yaw angles (horizontal axis) and wave incidence angles (vertical axis). (a) Maximum of blade root axial shear force; (b) Standard deviation of blade root axial shear force; (c) Maximum of yaw bearing moment; (d) Standard deviation of yaw bearing moment; (e) Maximum of tower base Y-direction bending moment; (f) Standard deviation of tower base Y-direction bending moment.

From Figure 11a,b, it can be observed that as the yaw angle increases, the maximum value and standard deviation of the blade root axial shear force are primarily governed by the yaw angle. Moreover, the increase in yaw angle reduces the asymmetric aerodynamic loads acting on the downstream wind turbine blades, leading to an overall decreasing trend in the axial shear force at the blade root. When the wave incident angle varies, the maximum axial shear force at the blade root is only indirectly influenced by changes in platform motion, resulting in slight fluctuations of small magnitude.

From Figure 11c,d, it can be observed that as the yaw angle increases from 0° to 25°, the maximum yaw bearing torque exhibits an approximately steady upward trend, with a maximum increase reaching up to 29.8%. This is because the yaw bearing torque acts to resist yaw motion. Therefore, when the leading wind turbine actively yaws, its yaw bearing torque increases significantly. Moreover, when the yaw angle is relatively small, the influence of the wave incident angle on the yaw bearing torque is most pronounced, with an amplitude of approximately 10%. Since both the wave incident angle and the yaw direction are defined as positive in the counterclockwise direction, when the wave incident angle is negative, the lateral components of the wave load and the wind load partially cancel each other out, resulting in a smaller torque about the vertical axis on the structure. Consequently, both the maximum value and standard deviation of the yaw bearing torque at the tower top under negative wave incident angles remain consistently lower than those under positive wave incident angles.

From Figure 11e,f, it can be observed that as the yaw angle increases, the maximum value of the Y-direction bending moment at the tower base exhibits a fluctuating trend. This phenomenon can be attributed to the changes in the frontal area of the wind turbine caused by variations in the yaw angle. As the yaw angle increases, the distribution of longitudinal aerodynamic loads on the downstream turbine becomes non-uniform, leading to a shift in the longitudinal loads acting on the turbine and thereby intensifying the fluctuation in the Y-direction bending moment at the tower base. As the wave incident angle increases, the distribution of wave forces becomes more dispersed, and their longitudinal components decrease. Consequently, the influence of longitudinal wave loads on the Y-direction bending moment at the tower base gradually weakens, resulting in a progressive reduction in the percentage differences of both the maximum value and standard deviation. In most cases, the peak loads are smaller when the wave incident angle aligns with the yaw misalignment angle. Under the influence of the wave incident angle, the variation amplitude of the maximum tower base Y-direction bending moment can reach approximately 7%.

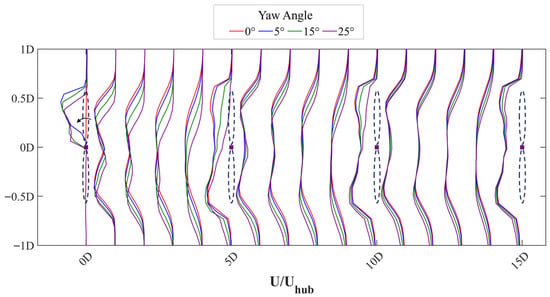

4.4. Flow Field

Figure 12 presents the wind speed profiles at the hub height of T1, T3, T5, and T7, using a wave incident angle of 10° as an example. The vertical axis represents the lateral spacing, with 0D indicating the center position of the wind turbine. The horizontal axis represents both the streamwise spacing and the local relative wind speed. Square markers indicate the rotor center position. It can be seen from the figure that at the first column wind turbine, as the yaw angle increases, the wake velocity of the yaw direction shows a significant decrease, while the downstream wake recovery speed significantly improves compared to the no-yaw condition, with the extent of improvement positively correlated with the yaw angle. The wind speed enhancement effect induced by yaw decays rapidly with increasing streamwise distance, showing only a brief improvement when passing downstream turbines. Meanwhile, yaw control delays the contact of the incoming wind with the blade in the lower section, leading to a slower velocity recovery compared to the no-yaw condition. Considering both the positive gains on the upper side and the negative gains on the lower side, the wake velocity improvement is most pronounced directly downstream of the first column turbines, while the positive wake effects gradually weaken for the second and subsequent columns of turbines.

Figure 12.

Wake deficit at wind turbine hub height under different yaw angles with 10° wave incidence angle. (The dashed line represents the wind turbine rotor, and the arrow indicates the yaw direction).

Figure 13 shows the time-averaged velocity contours of the wind turbine array under different yaw angles at a wave incident angle of 10°. It can be further observed that when the first column turbines are not yawed, the wake deficit is evenly distributed, with the maximum wake width, exhibiting a standard symmetric distribution. As the yaw angle of the first column turbines increases from 5° to 25°, the time-averaged wake gradually deflects toward the yaw direction, forming a large angle between the wake centerline and the incoming flow direction, with the wake concentrated on the yaw direction side. This leads to an aggravated wake deficit of the yaw direction for downstream turbines. Simultaneously, the wake width significantly decreases, meaning the region of wake kinetic energy loss is notably reduced, and the wake recovery speed accelerates. It should be noted that, as this study considers normal sea conditions, the amplitude variation range of the platform’s six-degree-of-freedom motion under different wave incident angles is relatively small. Therefore, the influence of the wave incident angle on the wake effect is not significant.

Figure 13.

Time-averaged velocity contour of the wind turbine array under different yaw angles with 10° wave incidence angle.

To further reveal the mechanism of yaw control’s influence on wake evolution, Figure 14 presents the instantaneous velocity contours at the wind turbine hub height plane under a wave incident angle of 10°. The four charts from left to right represent yaw angles of 0°, 5°, 15°, and 25°, respectively.

Figure 14.

Instantaneous velocity contour of the wind turbine array under different yaw angles with 10° wave incidence angle.

When the first column turbines are not yawed, the wake deficit region is mainly concentrated in the central downstream area, maintaining an approximately symmetric distribution, and the wake width is at its maximum. As the yaw angle of the first column turbines increases, the wake deflection angle gradually increases, the wake centerline progressively deviates from the incoming flow direction, and downstream turbines transit from a state of full wake overlap to partial wake overlap. High-speed airflow from the opposite side flows into the rotors of downstream turbines, increasing their power generation and thereby enhancing the overall farm power output. At the same time, the lateral width of the wake gradually narrows, with its transverse expansion becoming constrained. The wake becomes concentrated on the side of the yaw direction, and the degree of wake meandering gradually intensifies. This exacerbates the wake deficit of the downstream wind turbine on that side, which, while increasing the motion response of the floating platform, simultaneously promotes wake recovery and enhances power generation.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of active yaw control on the response and wake of the FOWT array under misaligned wind-wave conditions. By analyzing power output variations under multiple operational scenarios, the influence of yaw angle and wave incident angle on the power generation of FOWT arrays is revealed. Furthermore, through the analysis of platform motion, structural loads, and flow field under different conditions, the coupled effects of the yaw angle of the first column turbines and the wave incident angle on platform motion, structural loads, and the flow field are elucidated, providing data support and a theoretical basis for optimizing the yaw control strategy of FOWTs. The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

- (1)

- When implementing yaw control on the first column FOWTs under misaligned wind-wave conditions, the change in wind farm power output is significantly influenced by the yaw angle. As the yaw angle increases from 0° to 30°, the power output can be increased by up to 8.6%. Under normal sea conditions, the platform motion amplitude induced by changes in the wave incident angle is relatively small, and the wind-wave misalignment angle does not significantly affect the power output of the FOWT array. In practice, since the wave incident angle has minimal impact on power output under normal sea states, the control system can neglect the effects of wind-wave misalignment when focusing solely on power generation, thereby simplifying the control logic.

- (2)

- When implementing yaw control on the first column FOWTs under misaligned wind-wave conditions, the average motion response of the leading wind turbine always decreases significantly along with the increase of yaw angle. However, because the yawing of the upstream turbines affects the downstream flow field distribution and wind load direction, the average motion responses of the downstream turbines show an increasing trend. A comparative analysis of surge, heave, and pitch motions reveals that the wave incident angle has the most noticeable impact on platform heave, with a maximum variation of up to 10%.

- (3)

- Under wind-wave misalignment conditions, the tower top yaw bearing torque is most significantly affected by the wind-wave misalignment angle. The misalignment causes the lateral components of the wind load and wave load to superimpose, generating a substantial vertical axis torque that is transmitted to the tower top yaw bearing. For the same yaw angle, the torque can increase by up to 10% due to changes in the wind-wave misalignment angle. The variation in the tower base Y-direction bending moment is the next most significant, with a maximum change of approximately 7%. The blade root axial shear force is minimally affected by the wind-wave misalignment angle, and its impact is essentially negligible. Therefore, in practical engineering, when analyzing the loads of FOWTs, wind-wave misalignment is a factor that cannot be neglected due to the superposition effects of wave and wind loads.

- (4)

- Changes in the flow field distribution are primarily influenced by the yaw angle. Yaw control applied to the first column turbines alters the downstream wake velocity and deflection direction, leading to significant changes in the power output, platform motion, and structural loads of the wind turbines. Moreover, since the influence of the wave incident angle is mainly concentrated below the waterline, it does not noticeably affect the flow field.

Current research focuses on the performance of NREL 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbine arrays under normal sea conditions, employing a strategy currently limited to static yaw control. With the trend toward larger and more efficient FOWTs, future work could further evaluate the performance of 15 MW or even 22 MW turbines under different yaw control strategies, thereby providing advanced recommendations for power output enhancement and load optimization in offshore wind farms.

Author Contributions

X.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing-review & editing (equal). Z.Y.: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—review & editing (equal). Z.X.: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing (equal). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaofei Zhang was employed by the company Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FOWT | Floating offshore wind turbine |

| BEM | Blade Element Momentum |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| ABL | Atmospheric boundary layer |

| AWAE | Ambient Wind and Array Effects |

| T | Turbine |

| WT | Wind turbine |

| Nomenclature | |

| Aerodynamic parameters | |

| Power spectral density of velocity component | |

| f | Frequency |

| σ | Standard deviation of the wind speed |

| Turbulent integral length | |

| Mean wind speed at the hub height | |

| Elemental thrust | |

| Elemental torque | |

| Air density | |

| Relative wind speed at the blade element section | |

| Inflow angle | |

| Number of blades | |

| Chord length | |

| Distance from the blade element to the hub center | |

| Lift coefficients, Drag coefficients | |

| Radial length of the blade element | |

| Eddy viscosity coefficient | |

| Local thrust coefficient, Time-filtered thrust coefficient | |

| Time-filtered relative wind speed averaged across the rotor disk | |

| Near-wake tuning constant | |

| Radii at the wake region | |

| Radially dependent induction | |

| Lateral induced velocities | |

| Vertical induced velocities | |

| Circulation | |

| Skew angle. | |

| Freestream velocity | |

| Wind speed at hub height | |

| Hydrodynamic parameters | |

| Power spectral density of wave | |

| Wave angular frequency | |

| Peak wave angular frequency | |

| Peak enhancement factor | |

| Spectral width parameter | |

| Total hydrodynamic force on a structural element | |

| Inertial force acting on the structure element | |

| Drag force acting on the structure element | |

| Inertia coefficient, Added mass coefficient, Drag coefficient | |

| Wave potential | |

| Velocity potential of the incident wave, the diffracted wave, and the radiated wave | |

Appendix A. Additional Plots

Figure A1.

Comparison of undisturbed mean wind speed profiles generated by TurbSim and SOWFA.

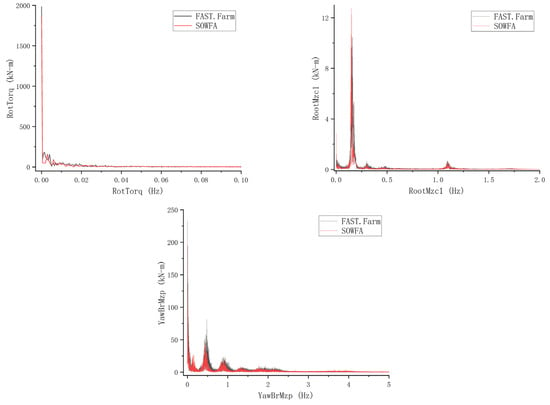

Figure A2.

Comparison of the platform response spectra calculated by FAST.Farm and SOWFA.

Figure A3.

Comparison of structural load spectra calculated by FAST.Farm and SOWFA (From left to right: Rotor torque; Pitching bending moment at the blade root; Yaw bearing torque).

References

- Deng, L.; Wu, S.; Zhong, W.; Song, X. Influence of Wind-wave Intersection Angle Change on the Mooring System of Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chitteth Ramachandran, R.; Desmond, C.; Judge, F.; Serraris, J.; Murphy, J. Floating wind turbines: Marine operations challenges and opportunities. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamei, A.; Hayatdavoodi, M.; Riggs, H. Hydro- and aero-elastic response of floating offshore wind turbines to combined waves and wind in frequency domain. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Ener. 2024, 10, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ransley, E.; Qian, L.; Zhou, Y.; Brown, S.; Greaves, D.; Hann, M.; Holcombe, A.; Edwards, E.; Tosdevin, T.; et al. Modelling the hydrodynamic response of a floating offshore wind turbine—A comparative study. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 155, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, P.; Garrido, A.; Garrido, I.; Nguyen, D.; Gao, Z. Hydrostatic stability and hydrodynamics of a floating wind turbine platform integrated with oscillating water columns: A design study. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, Q.; Li, C.; Ding, Q. Research on dynamic response of super large floating wind turbine under wind-wave misalignment. J. Mech. Strength 2022, 44, 383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Riefolo, L.; del Jesus, F.; Guanche García, R.; Tomasicchio, G.; Pantusa, D. Wind/Wave Misalignment Effects on Mooring Line Tensions for a Spar Buoy Wind Turbine. In Proceedings of the ASME 2018 37th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Madrid, Spain, 17–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz, M.; Cheng, P. Effect of mooring system stiffness on floating offshore wind turbine loads in a passively self-adjusting floating wind farm. Renew. Energy 2025, 238, 121823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qin, H.; Zhang, H.; Long, Q.; Ma, D.; Xu, C. Mooring Evaluation of a Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Platform Under Rogue Wave Conditions Using a Coupled CFD-FEM Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.; Nouri, R.; Vasel-Be-Hagh, A. Wind turbine wake control strategies: A review and concept proposal. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmie, R.; Jensen, L. Evaluation of wind farm efficiency and wind turbine wakes at the Nysted offshore wind farm. Wind Energy 2010, 13, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.; Vasel-Be-Hagh, A.; Yan, C.; Wu, S.; Pan, Y.; Brodie, J.; Maguire, A. Review and evaluation of wake loss models for wind energy applications. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porté-Agel, F.; Bastankhah, M.; Shamsoddin, S. Wind-turbine and wind-farm flows: A review. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2020, 174, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebraad, P.; Wingerden, J. Maximum power-point tracking control for wind farms. Wind Energy 2015, 18, 429–447. [Google Scholar]

- Nanos, E.; Letizia, S.; Clemente, D.; Wang, C.; Rotea, M.; Lungo, V.; Bottasso, C. Vertical wake deflection for offshore floating wind turbines by differential ballast control. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1618, 022047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Annoni, J.; Shah, J.; Wang, L.; Ananthan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hutchings, K.; Wang, P.; Chen, W.; Chen, L. Field test of wake steering at an offshore wind farm. Wind Energy Sci. 2017, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Cheng, P.; Wan, D. Numerical study of wake interaction between two wind turbines operating in different yaw angles. Ocean Eng. 2019, 37, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, X.; Cao, L.; Wan, D. Study of wind farm optimization through yaw control based on analytical wake model. Ocean Eng. 2020, 38, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Liao, W.; Ding, Q.; Hao, W. Study on Control Strategies for Wind Turbine Wakes. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2017, 37, 584–589+596. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Yang, X. Influence of yaw condition on the foundation motion response and mooring load of offshore floating wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2022, 40, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, H.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, G. Study on the active yaw control effect on the coupled system dynamics of rotor and floating platform for floating wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2025, 339, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaler, K.; Jonkman, J. FAST. Farm response to varying wind inflow and discretization. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, J.; Wyngaard, J.; Izumi, Y.; Coté, O. Spectral characteristics of surface-layer turbulence. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1972, 98, 563–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossanyi, E. GH Bladed Theory Manual; Garrad Hassan and Partners Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, P.; Hansen, A. Aerodyn Theory Manual; National Renewable Energy Lab.: Golden, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Branlard, E.; Martínez-Tossas, L.; Jonkman, J. A time-varying formulation of the curled wake model within the FAST. Farm framework. Wind Energy 2023, 26, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Mukhopadhaya, J.; Iaccarino, G.; Alonso, J. Uncertainty Estimation Module for Turbulence Model Predictions in SU2. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhaya, J.; Whitehead, B.; Quindlen, J.; Alonso, J.; Andrew, C. Multi-Fidelity modeling of Probabilistic Aerodynamic Databases for Use in Aerospace Engineering. Int. J. Uncertain. Quantif. 2020, 10, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, J. Calculating the Flowfield in the Wake of Wind Turbines. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerod. 1988, 27, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmann, K.; Barnett, T.; Bouws, E.; Carlson, H.; Cartwright, D.; Enke, K.; Ewing, J.; Gienapp, H.; Hasselmann, D.; Kruseman, P.; et al. Measurements of wind-wave growth and swell decay during the Joint North Sea Wave Project (JONSWAP). Deut. Hydrogr. Z. 1973, 8, 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chujo, T.; Ishida, S.; Minami, Y.; Nimura, T.; Inoue, S. Model experiments on the motion of a spar type floating wind turbine in wind and waves. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 19–24 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, L.; Jonkman, J.; Thedin, R. Investigating the interactions between wakes and floating wind turbines using FAST.Farm. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, A.; Ramachandran, G.; Vita, L.; Gómez Alonso, P.; Berque, J.; Aguirre-Suso, G. LIFES50+ D7.2 Design Basis; DNV-GL: Høvik, Norway, 2015; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318402254_Design_Basis (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Simley, E.; Fleming, P.; Girard, N.; Alloin, L.; Godefroy, E.; Duc, T. Results from a wake-steering experiment at a commercial wind plant: Investigating the wind speed dependence of wake-steering performance. Wind Energy Sci. 2021, 6, 1427–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.; Vasel-Be-Hagh, A. Wake steering via yaw control in multi-turbine wind farms: Recommendations based on large-eddy simulation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 33, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachynski, E.; Kvittem, M.; Luan, C.; Moan, T. Wind-Wave Misalignment Effects on Floating Wind Turbines: Motions and Tower Load Effects. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2014, 136, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Gao, Z.; Vedvik, N. Effects of Wind-Wave Misalignment on a Wind Turbine Blade Mating Process: Impact Velocities, Blade Root Damages and Structural Safety Assessment. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2020, 19, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaler, K.; Jonkman, J. FAST. Farm development and validation of structural load prediction against large eddy simulations. Wind Energy 2021, 24, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Dar, A.; Porté-Age, F. A wind tunnel study on cyclic yaw control: Power performance and wake characteristics. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.