Abstract

Background/Objectives: Incisional hernia (IH) is a frequent complication after kidney transplantation, with its risk influenced by both patient-related factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and smoking, and procedure-related factors including surgical technique and immunosuppressive therapy. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with IH and to evaluate the impact of suture type used for fascial closure in kidney transplant recipients. Methods: We performed a single-center retrospective case–control study including adult kidney transplant recipients who underwent transplantation between January 2014 and January 2024. Patients who developed an IH were identified and matched 1:6 with controls according to year of transplantation. Demographic variables, patient comorbidities, dialysis modality, and type of fascial closure suture were analyzed. Patients were subsequently compared according to the type of fascial closure used, either absorbable barbed polydioxanone sutures or absorbable monofilament polyglyconate loop sutures. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify independent predictors of IH. Results: Among 1586 kidney transplant recipients, 39 patients developed an IH, corresponding to an incidence of 2.5% after a median follow-up of 36 months. On multivariable analysis, age was independently associated with IH development (OR 1.04; p = 0.01), as was obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2; OR 2.55; p = 0.01). The overall incidence of IH did not differ significantly between suture types, with rates of 11.4% (10/88) for absorbable barbed polydioxanone sutures versus 15.6% (29/186) for absorbable monofilament polyglyconate loop sutures (p = 0.35). In obese recipients, however, fascial closure with barbed polydioxanone sutures was associated with a significantly lower incidence of IH, at 9.1% (2/22) versus 36.4% (12/33) for loop sutures (p = 0.02). Conclusions: Obesity and older age were the main independent predictors of IH after kidney transplantation in this cohort. In obese recipients, fascial closure using absorbable barbed polydioxanone sutures was associated with a substantially lower IH rate. These findings warrant confirmation in prospective, randomized studies.

1. Introduction

Incisional hernia (IH) is among the most frequent complications following abdominal wall surgery. The overall incidence of IH has been estimated to range between 4% and 20%, depending on surgery type and duration of follow-up [1]. IH has been associated with multiple negative consequences affecting patients’ health and quality of life, including impaired body image, prolonged hospital stays, postoperative morbidity, and increased rates of reintervention [2,3]. Risk factors for IH in the general surgical population have been widely studied and are known to include obesity, male sex, diabetes mellitus, postoperative wound infection, smoking, and the use of immunosuppressive therapy [1,4,5,6]. Because renal transplant recipients are systematically exposed to chronic immunosuppression and often present multiple metabolic comorbidities, it has been traditionally assumed that they would be at higher risk of developing IH. Their management is often challenging due to altered tissue healing, the presence of the graft and vascular anastomoses, and the increased risk of infection associated with immunosuppression [6,7].

Multiple studies have evaluated specific risk factors for this population, identifying obesity, peritoneal dialysis (PD), wound infection, and use of mTOR inhibitors as the most consistent contributors to IH formation [5,6,8,9,10,11]. In addition, the type and quality of fascial closure have been increasingly recognized as modifiable determinants of postoperative hernia formation. Recent evidence suggests that suture technique, including suture material, tension distribution, and whether barbed or conventional sutures are used, may influence the integrity of the abdominal wall and the risk of IH in transplanted patients [12,13,14]. The aim of this study was to assess the association between IH incidence and the type of suture material used at our center, and to identify risk factors for IH development in kidney transplant recipients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective case–control study of kidney transplant recipients, assessing the risk of developing an IH and its potential association with the type of fascial closure suture. All data were obtained from a single academic public tertiary-care center. The study included all kidney transplant recipients treated between January 2014 and January 2024.

2.2. Participants

Cases were defined as kidney transplant recipients who developed an IH following transplantation. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age younger than 18 years, combined hepato-renal transplantation, second transplants in the ipsilateral fossa, and inability to complete postoperative follow-up due to death or transfer of care to another institution.

For each case, six controls were randomly selected from the same transplant cohort among recipients who did not develop an IH. To minimize temporal confounding, controls were matched to each case by year of transplantation. Controls were required to meet the same exclusion criteria applied to cases.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Transplant Technique

All patients underwent open kidney transplantation using a pararectal “hockey-stick” incision, beginning longitudinally in the lower lateral abdomen and curving slightly medially above the pubic symphysis. During the study period, fascial closure was standardized as a single-layer running closure of the external oblique aponeurosis. The only common variation in the technique was the use of either an absorbable barbed polydioxanone suture (Stratafix: Ethicon. Somerville, NJ, USA) or an absorbable monofilament polyglyconate loop suture (Maxon Loop: Covidien. Mansfield, MA, USA).

2.3.2. Immunosuppression

After kidney transplantation, all patients received standard triple immunosuppressive therapy consisting of a calcineurin inhibitor, an antiproliferative agent, and corticosteroids. Detailed data on corticosteroid dosage and cumulative immunosuppressive exposure during the follow-up period were difficult to accurately collect and quantify; therefore, these variables were not included in the analysis.

2.3.3. Incisional Hernia Diagnosis

Post-transplant follow-up was routinely performed at least monthly during the first year, every three months during the second year, and annually thereafter. IH was diagnosed through systematic clinical assessment, including physical examination with Valsalva maneuvers. In all cases of clinical suspicion or if findings were inconclusive, imaging studies such as ultrasound or CT scan were used to confirm the diagnosis, ensuring accurate detection of both symptomatic and subtle hernias.

2.4. Variables

Data were extracted from electronic medical records. The following potential risk factors for IH were collected. Recipient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, history of previous transplant(s), etiology of end-stage kidney disease (including polycystic kidney disease), and pretransplant dialysis modality (including peritoneal dialysis). Transplant-related variables: donor type (deceased vs. living), implantation site, type of fascial closure suture (Stratafix vs. Maxon Loop), and immunosuppressive regimen.

2.5. Data Sources and Measurements

Potential risk factors were compared between recipients with IH (cases) and matched recipients without a hernia (controls). Variables were selected according to established evidence and clinical relevance and included in the multivariable logistic regression model to identify independent predictors of IH.

To assess the effect of suture type, the incidence of IH was compared between recipients undergoing fascial closure with Stratafix versus Maxon Loop. Event rates were stratified according to baseline characteristics that demonstrated differences in the initial analysis.

2.6. Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistical methods were applied. For quantitative variables, normally distributed data were summarized using the mean and standard deviation, whereas non-parametric data were reported as the median and interquartile range. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Qualitative variables were reported as absolute frequencies and percentages.

Inferential statistical analyses were performed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. For quantitative variables with non-parametric distributions, comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. Independent risk factors for IH were evaluated through multivariable logistic regression analysis. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JASP version 0.95.3 (Intel).

3. Results

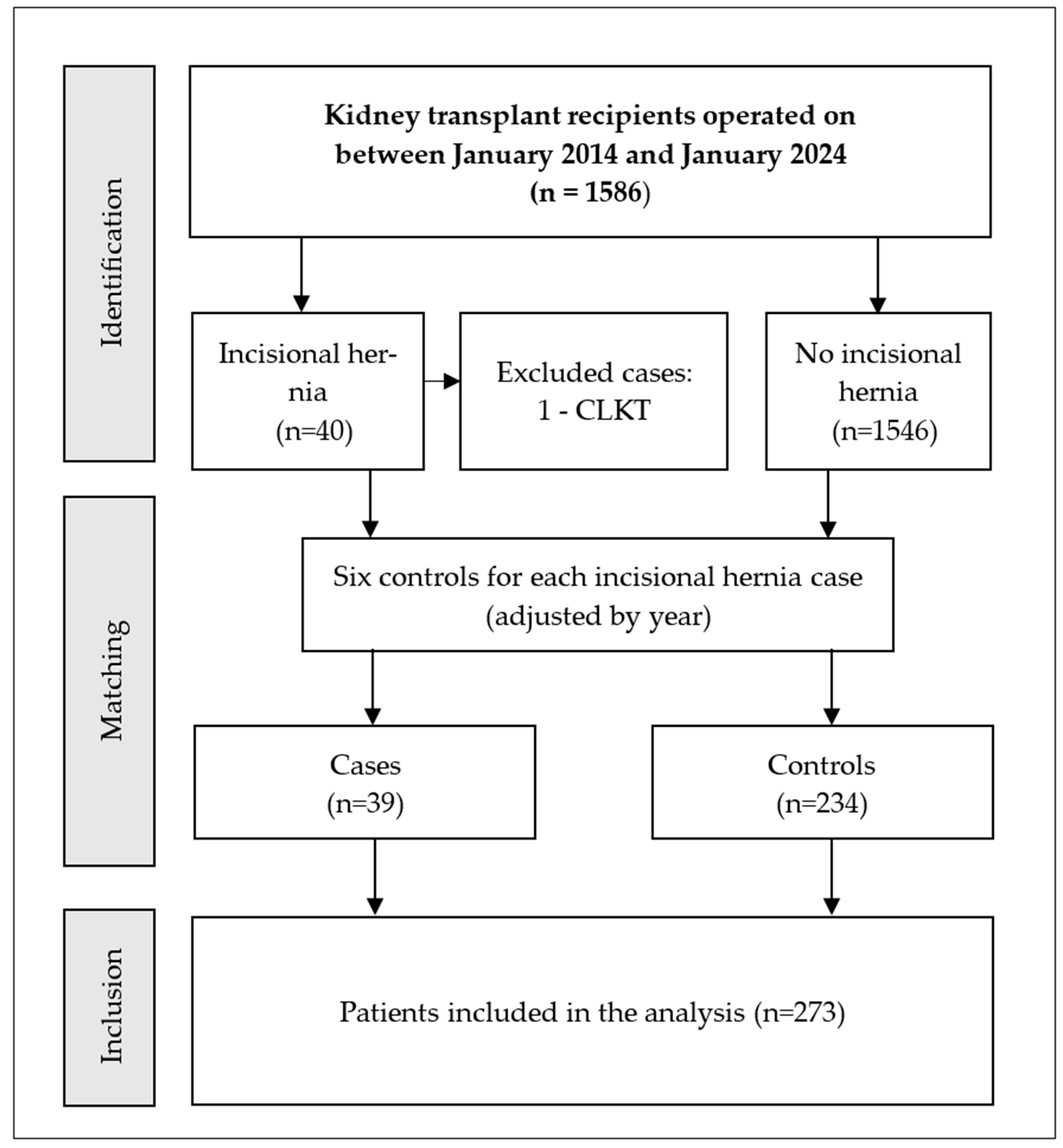

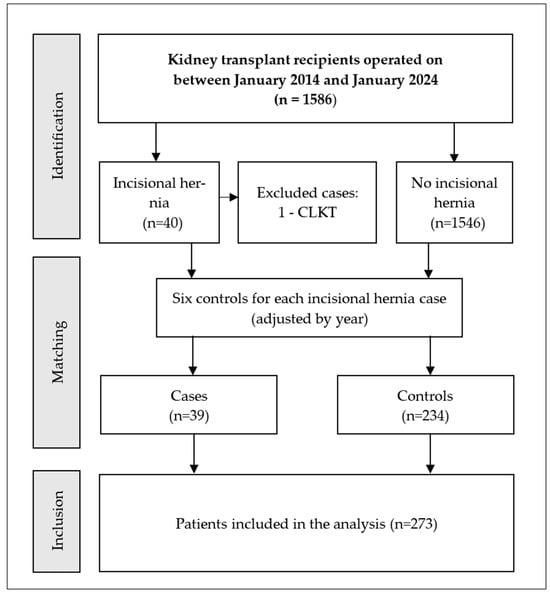

During the study period, a total of 1586 kidney transplants were performed, of which 40 recipients were identified with IH (Figure 1). One recipient was excluded because they underwent a combined liver and kidney transplantation. For the remaining 39 recipients, 234 control recipients were randomly selected. No other patients were excluded for reasons such as age younger than 18 years, second transplants in the ipsilateral fossa, or inability to complete postoperative follow-up due to death or transfer of care to another institution.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection. Abbreviations: CLKT—combined liver and kidney transplantation.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the hernia and control groups showed that the hernia group included a higher proportion of male recipients (76.9% vs. 57.9%, p = 0.02) (Table 1). Median age was also higher in the hernia group (68 [14.0] vs. 59 [19.0] years, p = 0.009). Similarly, body mass index (BMI) was higher among recipients with hernia (28.2 kg/m2 [5.9] vs. 25.3 kg/m2 [5.5], p = 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in renal transplant recipients with and without incisional hernia.

Recipients on PD had a higher incidence of IH compared to those on hemodialysis (17.7% [29/163] vs. 9.0% [10/111]; p = 0.04). In contrast, recipients with polycystic kidney disease (PKD) exhibited a lower rate of hernia (2.5% [1/40] vs. 16.4% [38/231]; p = 0.02).

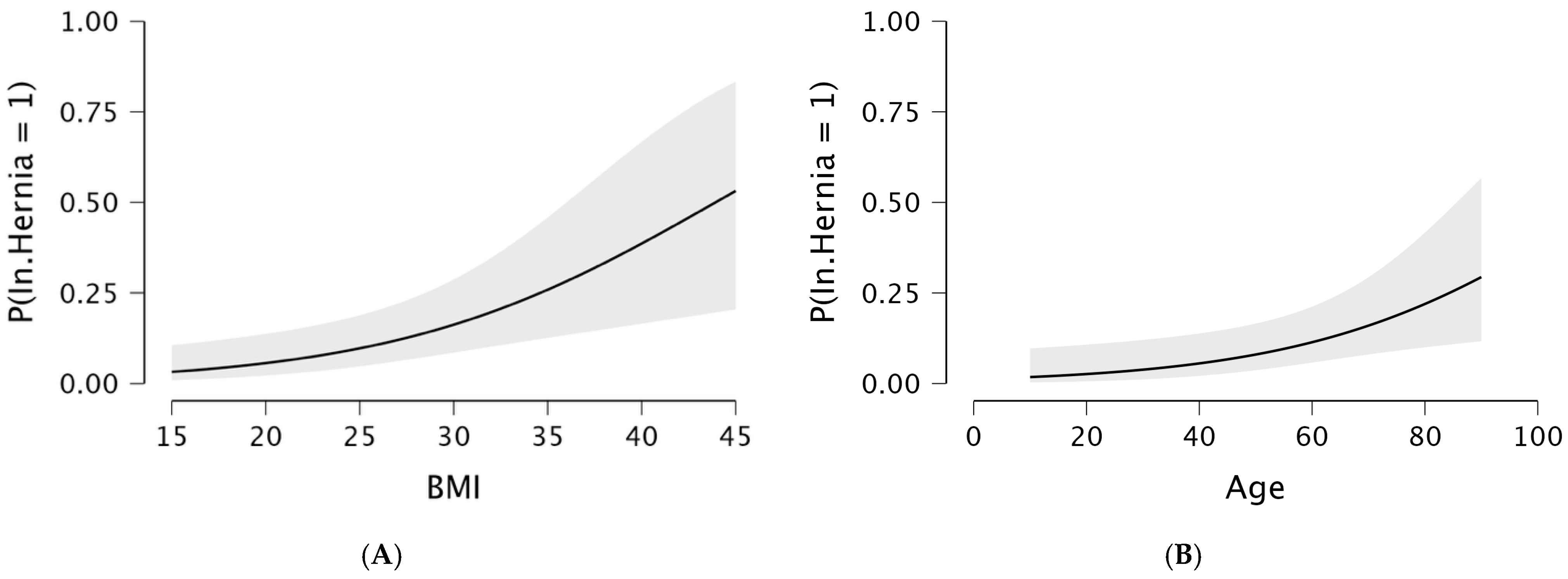

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified only age and BMI as independent risk factors (Table 2, Figure 2). Obese recipients (BMI > 30 kg/m2) had a significantly increased risk of developing IH (OR 2.55, p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of incisional hernia risk in renal transplant recipients.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of incisional hernia following open kidney transplantation by BMI (A) and age (B), estimated using a logistic regression model. The solid line indicates the predicted probability, and the shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval.

Analysis of suture type revealed that surgeons tended to use absorbable barbed polydioxanone sutures for male recipients, obese recipients, and those with a history of previous kidney transplantation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics according to the type of fascial closure suture used in kidney transplantation.

Stratified analysis of incisional hernia rates according to suture type showed that obese recipients (BMI > 30 kg/m2) whose fascia was closed with absorbable barbed polydioxanone had a significantly lower incidence of hernia compared to recipients whose fascia was closed with absorbable monofilament polyglyconate loop sutures, with rates of 9.1% (95% CI, 2.5–27.8%) versus 36.4% (95% CI, 22.2–53.4%), respectively (p = 0.02) (Table 4). Among recipients with lower BMI and other characteristics, no significant differences were observed.

Table 4.

Effect of different fascial closure sutures on incisional hernia incidence in patients stratified by sex, body weight, and history of previous transplantation.

4. Discussion

In this single-center retrospective analysis, the incidence of IH following kidney transplantation was 2.5% after a median follow-up of 36 months. This finding is consistent with previously published series reporting incidences ranging from 1.6% to 3.8%, with follow-up periods of up to 16 months [15,16]. These rates are notably lower than those described for other types of abdominal wall incisions, particularly midline incisions, for which the incidence may reach 20%. This difference is likely explained by the anatomical location of the iliac incision used in kidney transplantation, where the transfascial and transmuscular approach is oriented perpendicular to the dominant abdominal wall tension lines [17]. Moreover, the relatively low incidence of IH in our cohort may be attributable to the use of a pararectal “hockey-stick” incision, which minimizes muscular injury and preserves the integrity of the abdominal wall. This feature may further explain discrepancies with other studies employing different incision types or closure techniques.

Among all variables examined, only age and obesity remained independently associated with IH in the multivariable regression model. In our cohort, recipients with a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 had a 2.55-fold higher risk of developing IH. Obesity is one of the strongest and most consistently reported risk factors for IH in both general surgery and transplantation [18]. Increased intra-abdominal pressure, poor vascularity of adipose tissue, and heightened mechanical tension on the fascial closure likely account for this markedly elevated risk. Similarly, older age has repeatedly been associated with impaired collagen turnover, reduced fascial tensile strength, and delayed wound healing, all of which contribute to decreased resistance of the abdominal wall. Previous studies are in line with our findings. In a study by Mehdavi et al. including 589 kidney transplant recipients, higher BMI and older age were identified as relevant risk factors for postoperative hernia formation [19]. Likewise, Humar et al., in a cohort of 2013 kidney transplant recipients, reported obesity and the use of mycophenolate mofetil as significant contributors to hernia development [20]. In our study, immunosuppressive therapy was not analyzed, as all recipients received a uniform regimen consisting of a calcineurin inhibitor, an antiproliferative agent, and corticosteroids. In future studies, a more detailed assessment of immunosuppressive regimens and dosing could help clarify the potential role of these therapies in the development of incisional hernia.

PD as a risk factor for IH in kidney transplant recipients has been infrequently investigated, with most available evidence focusing on abdominal wall hernias in general rather than IH specifically. Nevertheless, previous studies have consistently identified PD as a potential risk factor for hernia formation [21]. Longstanding evidence suggests that PD increases intra-abdominal pressure due to dialysate infusion, thereby predisposing patients to abdominal wall hernias and dialysate leaks [22]. In our cohort, PD was more prevalent among recipients who developed IH and was associated with a trend toward increased risk in adjusted analyses. These findings support the notion that kidney transplant recipients with a history of PD may represent a higher-risk population for postoperative IH, although further studies are required to confirm this association.

Another noteworthy observation of our study was that PKD emerged as a protective factor in the univariable analysis. This finding contrasts with previous reports in which PKD has been associated with connective tissue abnormalities, potentially predisposing these patients to hernias in general [23,24]. We hypothesize that recipients with PKD at our center tended to be younger, had a lower body mass index, and underwent native nephrectomy in 32% of cases, thereby providing increased intra-abdominal space at the time of graft placement. These factors may reduce tension on the pararectal fascial closure, resulting in a substantially lower risk of IH.

In the stratified analysis, among obese recipients (BMI > 30 kg/m2), the incidence of incisional hernia was significantly lower when fascial closure was performed with absorbable barbed polydioxanone sutures compared with conventional monofilament loop sutures (9.1% vs. 36.4%, p = 0.02). This finding is likely related to the fact that barbed sutures provide more uniform tension distribution and a more secure closure under high-tension conditions, which may explain their superiority in this patient population. Furthermore, unlike conventional interrupted or running sutures that concentrate stress at specific points, barbed sutures distribute tension continuously along the suture line, thereby reducing the risk of tissue tearing and enhancing wound integrity [25]. These findings indicate that barbed sutures may offer a safe and effective option for fascial closure in obese kidney transplant recipients, potentially reducing the risk of incisional hernia in this high-risk population. However, this observation should be interpreted with caution given baseline differences between the suture groups. As barbed sutures were more frequently used in recipients with higher-risk characteristics and in those perceived to be at increased risk of incisional hernia, this selection pattern may underestimate their potential benefit. Nevertheless, these stratified analyses were exploratory in nature, designed to explore potential patterns within clinically relevant subgroups, and no formal adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied due to the limited number of events. Further prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to better delineate the role of suture type in preventing incisional hernia.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged, most of which are related to its retrospective design. First, the choice of suture type was not randomized, which may have introduced selection bias. We observed a higher tendency to use barbed sutures in obese patients and in repeat transplantations, possibly reflecting trends reported in the existing literature. In addition, suture selection may have been surgeon-dependent, a factor not accounted for in our analysis. Future prospective studies should address these aspects to minimize potential bias. Second, factors with a well-established influence on the development of IH, including history of prior abdominal surgery, postoperative wound infection, cumulative exposure to immunosuppressive therapy, corticosteroid dosage, and the use of preventive measures such as abdominal binders, could not be comprehensively evaluated. This is due to the constraints of available data sources and the challenges of consistently extracting and following clinical information. In addition, other potentially relevant variables, such as donor-related characteristics and patients’ nutritional status, could not be reliably collected. The absence of these variables may have introduced residual confounding, potentially attenuated true associations, and limited a comprehensive characterization of risk factors for IH. Another important limitation is the relatively small number of IH events, which may have reduced the statistical power to detect modest associations and increased the risk of imprecise effect estimates. Consequently, non-significant findings, particularly regarding surgical variables, should be interpreted with caution, as true effects may have gone undetected due to limited power. Furthermore, the external validity of our findings may be limited by the single-center nature of the study. Surgical techniques, perioperative management, and patient characteristics may differ across institutions, and therefore, our results may not be fully generalizable. Future multicenter, prospective studies with standardized data collection are warranted to validate these findings and clarify the role of specific risk factors. Finally, the initial identification of IH was based on clinical assessment, with imaging studies performed only when clinically indicated. As a result, small or asymptomatic hernias may have remained undetected, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true incidence of IH in our cohort.

In conclusion, obesity and age were the main independent predictors of IH after kidney transplantation in our cohort. The use of barbed sutures may be associated with a lower incidence of IH among obese recipients. Prospective, multicenter studies with standardized data collection are needed to validate these findings and to further delineate the role of modifiable surgical factors, including suture type, in IH prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.d.l.M., O.B. and J.G.-O.; methodology, J.d.l.M. and O.B.; software, J.d.l.M. and O.B.; formal analysis, O.B.; investigation, J.d.l.M. and O.B.; data curation, J.d.l.M. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.d.l.M. and O.B.; validation, J.G.-O., S.Z., A.L., S.P. and D.L.; supervision, J.G.-O., S.Z. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The requirement for ethical review and approval by the local Institutional Review Board was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of fully anonymized data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent, which includes agreement for the use of patient data for scientific research and publication, was routinely obtained and signed before kidney transplantation for all patients at the study center.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IH | Incisional hernia |

| PKD | Polycystic kidney disease |

| PD | Peritoneal dialysis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CLKT | Combined liver and kidney transplantation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

References

- Nachiappan, S.; Subramanian, A.; Stewart, S.; Oke, T. Prophylactic mesh placement in high-risk patients undergoing elective laparotomy: A systematic review. World J. Surg. 2013, 37, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ramshorst, G.H.; Eker, H.H.; Hop, W.C.; Jeekel, J.; Lange, J.F. Impact of incisional hernia on health-related quality of life and body image: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 204, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goede, B.; Eker, H.H.; Klitsie, P.J.; van Kempen, B.J.; Polak, W.G.; Hop, W.C.; Metselaar, H.J.; Tilanus, H.W.; Lange, J.F.; Kazemier, G. Incisional hernia after liver transplantation: Risk factors and health-related quality of life. Clin. Transplant. 2014, 28, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itatsu, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Sugawara, G.; Kubota, H.; Tojima, Y.; Kurumiya, Y.; Kono, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Ando, M.; Nagino, M. Incidence of and risk factors for incisional hernia after abdominal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røine, E.; Bjørk, I.T.; Øyen, O. Targeting risk factors for impaired wound healing and wound complications after kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, P.H.; Liu, J.M.; Hsieh, M.L.; Kao, W.T.; Yu, K.J.; Pang, S.T.; Lin, P.H. The risk factors of the occurrence of inguinal hernia in ESRD patients receiving dialysis treatment: An observational study using national health insurance research database. Medicine 2022, 101, e31794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzucchi, E.; Nahas, W.C.; Antonopoulos, I.M.; Ianhez, L.E.; Arap, S. Incisional hernia and its repair with polypropylene mesh in renal transplant recipients. J. Urol. 2001, 166, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birolini, C.; Mazzucchi, E.; Utiyama, E.M.; Yoshimura, E.M.; Nahas, W.C.; Rasslan, S. Prosthetic repair of incisional hernia in kidney transplant patients: A technique with onlay polypropylene mesh. Hernia 2001, 5, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooms, L.S.; Verhelst, J.; Jeekel, J.; Ijzermans, J.N.; Lange, J.F.; Terkivatan, T. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of incisional hernia after kidney transplantation: An analysis of 1564 consecutive patients. Surgery 2016, 159, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.T.; Katz, M.G.; Foley, D.; Vandenberg, S.L.; Leverson, G.E.; Mezrich, J.D. Incidence and risk factors of incisional hernia formation following abdominal organ transplantation. Surg. Endosc. 2015, 29, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalti, R.; Mimmo, A.; Rompianesi, G.; Serra, V.; Cautero, N.; Ballarin, R.; De Ruvo, N.; Cunningham, R.; Enrico, G.; Di Benedetto, F. Early use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors is an independent risk factor for incisional hernia development after liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2012, 18, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitfeldt Sola, K.; Brismar, T.; Lorant, T.; Fränneby, U.; Larsson, O.; Genberg, H. Prediction of incisional hernia after kidney transplantation: Analysis of wound closure technique and risk factors. Hernia 2025, 29, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deerenberg, E.B.; Harlaar, J.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Lont, H.E.; van Doorn, H.C.; Heisterkamp, J.; Wijnhoven, B.P.; Schouten, W.R.; Cense, H.A.; Stockmann, H.B.; et al. Small bites versus large bites for closure of abdominal midline incisions (STITCH): A double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtha, A.P.; Kaplan, A.L.; Paglia, M.J.; Mills, B.B.; Feldstein, M.L.; Ruff, G.L. Evaluation of a novel technique for wound closure using a barbed, bidirectional suture. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, M.; Matia, I.; Kucera, M.; Oliverius, M.; Adamec, M. Polypropylene mesh repair of incisional hernia after kidney transplantation: Single-center experience and review of the literature. Ann. Transplant. 2011, 16, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.N.; Silverman, R.P.; Goldberg, N.H. Incisional hernia repair in renal transplantation patients. Hernia 2005, 9, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höer, J.; Lawong, G.; Klinge, U.; Schumpelick, V. Einflussfaktoren der Narbenhernienentstehung. Retrospektive Untersuchung an 2.983 laparotomierten Patienten über einen Zeitraum von 10 Jahren [Factors influencing the development of incisional hernia. A retrospective study of 2,983 laparotomy patients over a period of 10 years]. Chirurg 2002, 73, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, A.D.; Mukherjee, T.; Tashjian, N.; Siu, M.; Fitzgibbons, R., Jr.; Nandipati, K. Staged complex abdominal wall hernia repair in morbidly obese patients. Hernia 2021, 25, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, R.; Mehrabi, M. Incisional hernia after renal transplantation and its repair with propylene mesh. Urol. J. 2004, 1, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Humar, A.; Ramcharan, T.; Denny, R.; Gillingham, K.J.; Payne, W.D.; Matas, A.J. Are wound complications after a kidney transplant more common with modern immunosuppression? Transplantation 2001, 72, 1920–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.F.; Liu, C.J.; Yang, W.C.; Chang, C.F.; Yang, C.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Lin, C.C. The risk factors and the impact of hernia development on technique survival in peritoneal dialysis patients: A population-based cohort study. Perit. Dial. Int. 2015, 35, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, X.B.J.; Bargman, J. Complications of Peritoneal Dialysis Part I: Mechanical Complications. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 19, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pirson, Y. Extrarenal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010, 17, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.B.; Devuyst, O.; Eckardt, K.U.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Harris, T.; Horie, S.; Kasiske, B.L.; Odland, D.; Pei, Y.; Perrone, R.D.; et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): Executive summary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T.; Miyahara, K.; Shirasu, T.; Mochizuki, Y.; Taniguchi, R.; Takayama, T.; Hoshina, K. Risk Factors for Incisional Hernia After Open Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. In Vivo 2023, 37, 2803–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.