Abstract

Background/Objectives: Infertility is a major public health concern, affecting one in six individuals worldwide and nearly one-quarter of couples in France. While a male, female, or combined factor can be identified in approximately 75% of cases, infertility remains unexplained in 10–25%. Genital tract infections account for roughly 15% of male infertility cases and are often asymptomatic, being detected incidentally during routine evaluation prior to assisted reproductive technology (ART). Emerging evidence suggests that the seminal microbiota may contribute to sperm quality and male reproductive health. This systematic review aims to evaluate whether specific microbial profiles are associated with alterations in semen parameters. Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and ScienceDirect, yielding 165 and 1418 records, respectively. In the end, 20 articles were included in this systematic review. Results: Men with normal semen parameters commonly exhibited a higher abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, whereas Prevotella was more frequently observed in individuals with impaired semen quality. Several taxa—such as Gardnerella, Corynebacterium, and Staphylococcus spp.—were detected in both normal and altered semen profiles, suggesting that their impact on sperm quality may depend on reaching a pathogenic threshold. Conclusions: Current evidence supports an association between seminal microbiota composition and sperm quality. However, the heterogeneity of available studies and the lack of standardized methodologies limit the ability to draw firm conclusions. Further well-designed studies are required to clarify causal relationships and to determine the clinical relevance of seminal microbiota assessment in male infertility.

1. Introduction

According to the latest World Health Organization report, published in April 2023, infertility affects approximately one in six individuals worldwide [1]. In France, this condition impacts nearly 3.3 million people, or a quarter of all couples [2]. In roughly 75% of cases, a female, male or mixed etiology is identified. However, in 10% to 25% of cases, infertility remains unexplained [3].

Sperm quality can be affected by a variety of factors, including infections of the urogenital system [4,5] which account for approximately 15% of male infertility. Often asymptomatic, these infections are typically detected only through laboratory testing [6]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the detrimental effects of pathogenic bacteriospermia on sperm production and quality, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate management to limit their impact on male fertility [7].

The microbiota was first observed at the end of the 17th century through the pioneering work of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. The term “microbiota” refers to all microorganisms—primarily bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea—that live in a dynamic balance with their host [8]. Dysbiosis, or disruption of this balance, has been increasingly associated with a wide range of chronic and inflammatory diseases, from metabolic disorders to psychiatric conditions [9]. Understanding the complex mechanisms underlying host–microbiota interactions therefore represent a significant challenge for both preventive and therapeutic medicine. While the role of the gut microbiota in metabolic regulation, immunity, and even mental health is well established [10], the influence of the sperm microbiota remains largely unexplored.

Once considered a sterile fluid under physiological conditions, semen is now recognized to harbor a diverse microbial community, including both potentially beneficial and pathogenic bacteria. Advanced DNA amplification techniques, such as PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) followed by NGS (Next-Generation Sequencing), have enabled the detection of the sperm microbiota, improved our understanding of its role in male reproductive health, and demonstrated that the balance of this microbial ecosystem can directly affect sperm quality [11,12]. Although these findings are promising, the precise mechanisms by which the sperm microbiota influences male fertility remain to be elucidated.

In the context of male infertility, it is crucial to distinguish between seminal infection—typically defined by elevated bacterial counts (bacteriospermia), leukocytospermia, and clinical signs of inflammation—and alterations of the seminal microbiota, which may occur in the absence of overt infection. Indeed, dysbiosis of the seminal microbiome can be primarily qualitative, involving shifts in microbial composition or loss of beneficial taxa, without necessarily exceeding phatogenic thresholds or triggering an inflammatory response. Such subtle microbial imbalances may contribute to impaired sperm function even in men with otherwise unexplained (idiopathic) infertility.

The aim of this systematic review is to examine the influence of the composition and balance of the sperm microbiota on sperm quality. More broadly, it seeks to evaluate the potential impact of the microbiota on male fertility and the resulting clinical implications, particularly in the context of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART).

2. Materials and Methods

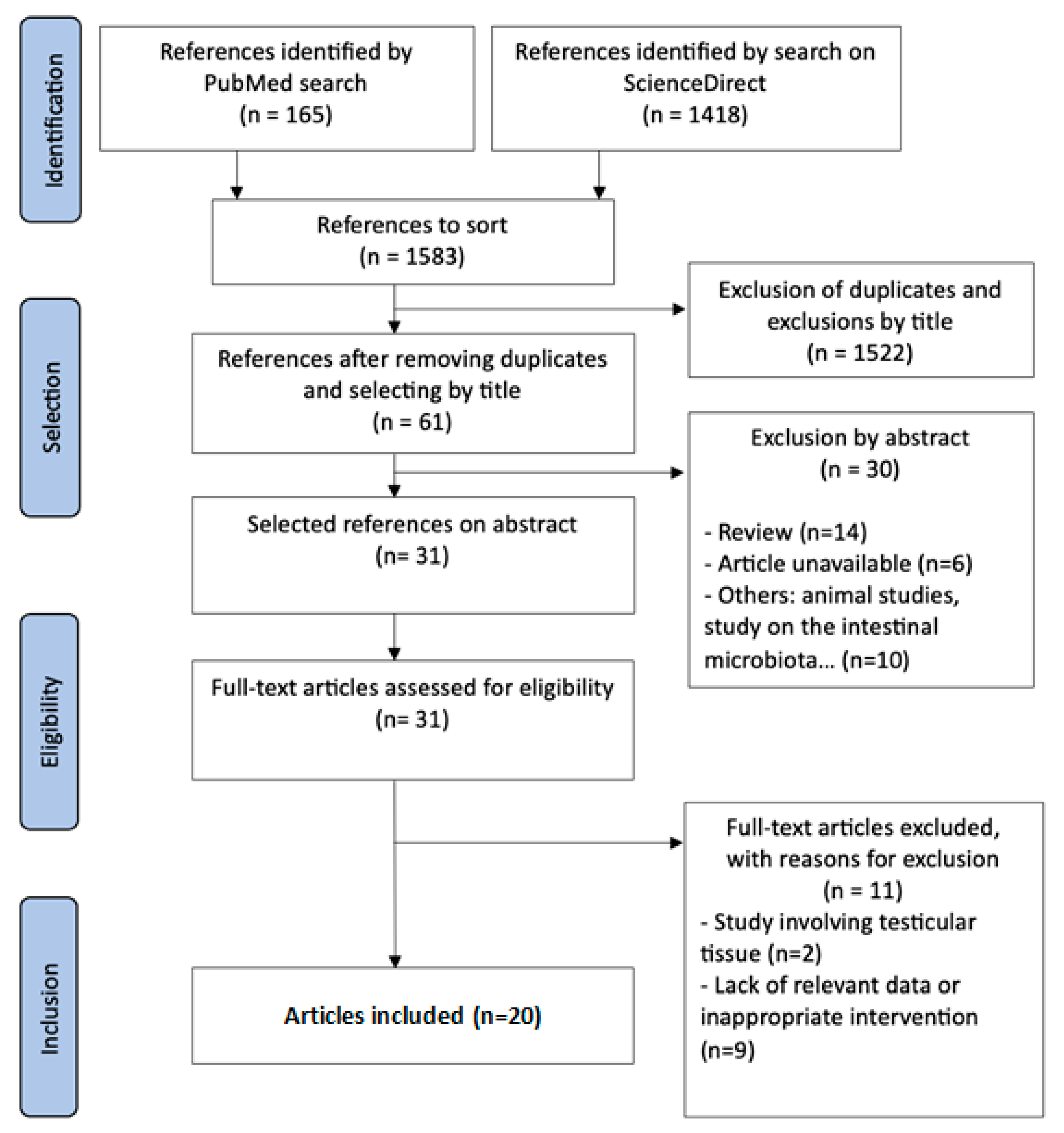

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). A systematic search of the PubMed and ScienceDirect databases was carried out from November 2023 to September 2024 to identify all human experimental published in English or French (Figure 1). To ensure the most comprehensive search possible, the following keywords were used: (seminal OR semen OR sperm OR fertility) AND (microbiota OR microbiome). All articles published in English or French were assessed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for identification and selection of studies.

A total of 1583 articles were identified. After eliminating duplicates and excluding studies whose titles were not relevant to the topic, 1522 articles were excluded. Of the 61 articles selected based on their titles, 30 were excluded after abstract screening. Of the remaining 31 articles, 11 were eliminated following full-text review for various reasons. Ultimately, 20 articles were included in this systematic literature review.

For each included study, the following information was extracted and compiled in tables: authors, year of publication, number of subjects, age, methods of analysis, study outcomes and main conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients Included in the Studies

Among the 20 studies included, the study population ranged from 20 to 1300 participants, with a total of 3065 individuals analyzed. The age of participants generally ranged from 20 to 60 years. The detailed results of each study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients included in the various studies.

3.2. Methods of Measurement

Different methods were used to characterize the microbiota associated with seminal-quality profiles. Standard culture methods and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique were routinely employed to isolate and identify bacteria present in biological samples such as semen. All the samples are fresh sperm.

In parallel, microbiome analysis can be performed using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing, enabled by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology and the corresponding bioinformatics software [13].

16S rRNA gene sequencing, the method of choice for microbiota analysis, was the most commonly used approach (16/20 studies) allowing the identification of a broad spectrum of bacterial taxa. Four studies relied on standard bacterial culture, frequently detecting pathogens such as S. aureus, Ureaplasma, Streptococcus, Enterococcus faecalis and Corynebacterium.

3.3. Sperm Microbiota and Semen Parameters

All studies analyzed the composition of the microbiota in relation to the presence or absence of altered sperm parameters. The detailed results of each study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Microbiota characteristics as a function of semen parameters.

As shown in Table 3, the bacteria most frequently found in normal semen were Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Gardnerella, Prevotella, and Corynebacterium in the majority of studies. However, Gachet et al. (2022) identified Mobiluncus, Finegoldia, Cutibacterium, and Gordonia as the predominant bacteria [23], while Chen et al. (2023) reported that Bifidobacterium was the most abundant bacterium in semen without abnormalities [24].

Table 3.

Pathogenicity thresholds (CFU/mL) for major semen bacteria in ART, based on Boitrelle et al., indicating levels at which antimicrobial treatment is clinically recommended to improve sperm quality and enhance the likelihood of achieving pregnancy through assisted reproductive technology [7].

4. Discussion

The work of Weng et al. (2014) [13], Baud et al. (2019) [16], Gachet et al. (2022) [23], and, more recently, Veneruso et al. (2023) [25] and Cao et al. (2023) [27] identified several bacteria associated with sperm alterations, including Prevotella according to Baud et al. (2019) [16], and Pseudomonas, Haemophilus, and Aggregatibacter according to Weng et al. (2014) [13]. In addition, the study by Veneruso et al. (2023) highlighted other bacteria linked to sperm alterations, including Mannheimia, Escherichia, and Shigella [25].

Certain bacteria, such as Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and Gardnerella, as well as Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Ralstonia, Prevotella, and Serratia, have been associated with oligozoospermia in men [16,19,21,25,26,28,29]. In addition, other bacteria, including Prevotella, Staphylococcus, Haemophilus, Corynebacterium, Ureaplasma, Sneathia, and Aerococcus, have been identified in men with oligozoospermia, asthenozoospermia, teratozoospermia, or combinations of these conditions [12,14,17,18,19,26,30].

In the study by Chen et al. (2023), a comparison between a control group and a group of men with idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia revealed that Bifidobacterium was specifically associated with the control group, while Bacteroides, Prevotella, Lactobacillus, Escherichia, and Shigella were characteristic of the case group [24].

Two studies examined the sperm DNA fragmentation index and found that bacteria associated with a high fragmentation index included Escherichia, Shigella, Lactobacillus spp., particularly Lactobacillus iners, as well as Acinetobacter spp., and Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae. In contrast, the presence of Peptostreptococcales-Tissierellales, Finegoldia spp., and Corynebacterium spp. was linked to a low DNA fragmentation index [19,28].

Okwelogu et al. (2021) [20] further investigated the relationship between sperm microbiota and clinical outcomes in ART, notably by comparing pregnancy outcomes and live birth rates after in vitro fertilization (IVF). Reduced microbial diversity, as well as the presence of Lactobacillus jensenii and Faecalibacterium in sperm, was associated with improved IVF outcomes. Conversely, a significant presence of Proteobacteria, Prevotella, and Bacteroides correlated with poorer results.

This review examined 20 studies to explore the association between the presence of various bacteria detected in semen, their impact on sperm quality (motility, concentration, and morphology), and their overall effects on male fertility, including implications for Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) management.

Certain bacteria have long been associated with impaired male fertility and are clinically treated when their concentrations exceed a defined threshold. Adverse effects typically manifest only above this threshold (see Table 2). The most prevalent bacteria include Escherichia coli, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Corynebacterium seminale. Bacteriospermia, particularly when accompanied by leukospermia (defined as more than one million leukocytes per milliliter of semen), has been linked to detrimental effects on sperm quality, including reduced motility, decreased concentration, and abnormal morphology [7].

Studies have advanced our understanding of the mechanisms by which certain bacteria can disrupt the biological processes involved in sperm production and function. Asymptomatic bacteriospermia, observed in a significant proportion of infertile men, triggers local inflammatory processes, increases production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and induces mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby impairing sperm quality [32]. Oxidative stress caused by the bacteria can lead to DNA damage, reduce motility, and disrupt sperm structure. Some bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, also promote sperm agglutination, rendering sperm immobile. Furthermore, leukospermia, by enhancing the release of free radicals and pro-inflammatory cytokines, intensifies oxidative stress and exacerbates these alterations, further compromising male fertility [33].

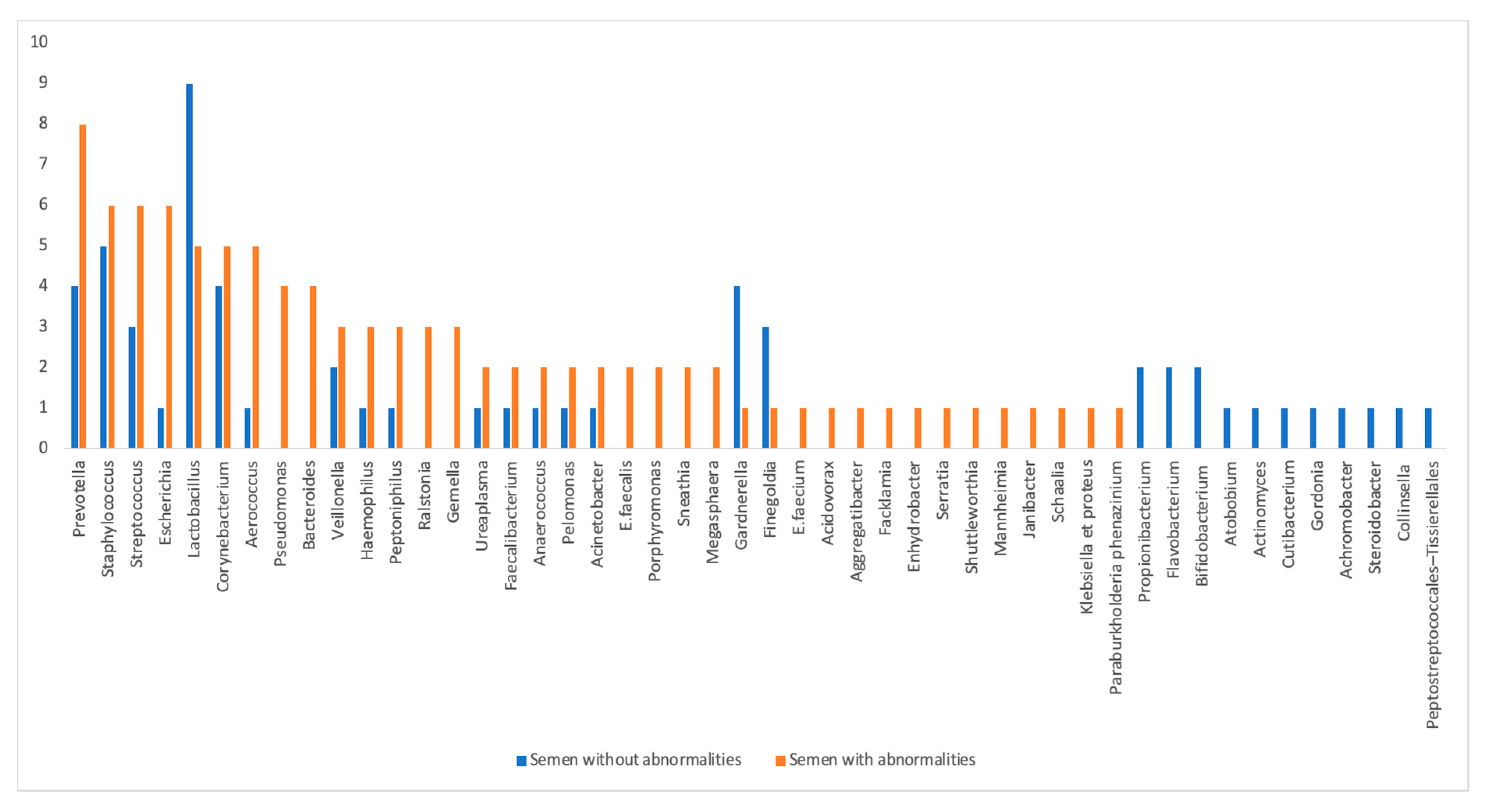

The distribution of the various bacteria identified in the studies according to their frequency of occurrence in the control group with “normal sperm parameters” and in the case group “with one or more sperm alterations” is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of identified bacteria by frequency of citation in the different groups: “normal semen parameters” (in blue) and “altered semen parameters” (in red).

4.1. Bacteria Associated with Normal Sperm Parameters

In our review, the bacteria most commonly found in the semen of men without abnormalities are Lactobacillus spp., well recognized for their beneficial role in human and animal health. These Gram-positive bacilli possess lactate-producing and anti-inflammatory properties. The lactate they produce serves as an essential intermediate metabolite in the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by the intestinal microbiota. These SCFAs play a fundamental role in numerous biological processes, including those related to reproductive health and fertility [34]. Furthermore, lactobacilli exhibit strong anti-inflammatory effects by modulating the JAK/STAT and NF-κB pathways, thereby reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β [35]. A recent study evaluated the effect of postbiotics derived from the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus PB01 on various sperm parameters, including progressive and total motility, viability, morphology, oxidative stress levels, and antioxidant enzyme activity. The results demonstrated that these postbiotics exert protective effects on sperm quality by reducing oxidative stress [36].

Bifidobacterium is another Gram-positive bacillus frequently identified as potentially beneficial for male fertility. Renowned for its probiotic properties, it is distinguished by its ability to produce lactate and butyrate. Butyrate plays a key role in modulating the immune response, limiting abnormal cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis, and regulating gene expression via epigenetic mechanisms. In addition, it helps reduce inflammation, notably by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion and stimulating anti-inflammatory cytokines [37,38]. Butyrate thus protects testicular cells against pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death usually triggered by infection or cellular stress, while maintaining their optimal function [38,39].

Like Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium spp. is recognized for its beneficial effects on intestinal health, notably through its role in restoring and maintaining microbiological balance. These bacteria also contribute to the production of organic acids, which inhibit the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms. By promoting an environment that reduces inflammation, improves digestive function and nutrient absorption, and enhanced local immune defenses, this bacterium could positively influence spermatogenesis [40].

Other bacteria, such as Peptostreptococcales-Tissierellales, Achromobacter spp., Cutibacterium spp., Mobiluncus spp., Gordonia spp., and Flavobacterium spp., have been identified in semen samples without abnormalities, but this observation was reported in only a single study. The available data remain insufficient to clarify their mechanisms of action, roles and potential impact on male fertility.

4.2. Bacteria Associated with Impaired Sperm Parameters

Prevotella was frequently identified in studies, both in control groups and in patients with impaired sperm quality. In women of childbearing age, Prevotella species may induce local inflammation and contribute to the development of bacterial vaginosis [41]. Although less well studied, the presence of Prevotella in sperm could play a role in male infertility by negatively affecting sperm quality, notably through a reduction in sperm concentration and motility. This bacterium could also be associated with negative results during in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempts, as suggested by the work of Okwelogu et al. (2021) [20].

Escherichia coli is also one of the primary microorganisms detected in semen, and when its presence exceeds a certain threshold, it can negatively affect sperm quality. Eliminating this bacterium not only improves sperm quality but also increases the likelihood of success in ART [7]. This bacterium reduces sperm motility, viability, and concentration by inducing damage to sperm DNA and compromising genetic integrity. These effects are due result from the production of toxins and enzymes that disrupt sperm cell functions, as well as from local inflammation that generates oxidative stress, damaging both the sperm membrane and genetic material. Moreover, E. coli produces lipopolysaccharides (LPS), major components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, which trigger a local immune response leading to a systemic inflammatory state implicated in numerous metabolic disorders [42].

Similarly, when detected above a certain threshold, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus spp., two Gram-negative bacteria that produce LPS, are associated with alterations in sperm quality, including reduced sperm concentration and motility as well as increased sperm DNA fragmentation [7,19].

In contrast, Streptococcus is a bacterium that can colonize various parts of the human body, including seminal fluid, potentially causing different types of infections. It adversely affects sperm quality when its concentration exceeds 5 × 103 CFU/mL, leading to oligo-asthenozoospermia and teratozoospermia [7,43]. Furthermore, excessive lactate production by certain Streptococcus strains can acidify the local environment, creating conditions toxic to sperm and potentially detrimental to male fertility [44,45].

In four of the reviewed studies, the presence of Pseudomonas was correlated with sperm alterations, including reduced sperm motility and concentration. Animal studies have demonstrated that exposure to Pseudomonas aeruginosa markedly reduces sperm motility and viability, even at moderate bacterial concentrations. At higher concentrations, the effects are amplified, causing visible damage to plasma membrane integrity and morphological abnormalities. These changes are attributed to toxins secreted by the bacterium and its enzymatic activities, which induce oxidative stress and negatively impact spermatozoa [46,47].

Another bacterium identified in seminal fluid that can negatively affect sperm parameters is Enterococcus spp. Contrary to the common belief that Enterococcus spp., specifically E. faecalis, remains confined to the intestinal flora, recent studies have shown that it can invade host cells, disseminate to various organs, and cause severe infections. This cellular invasion is facilitated by several virulence factors, including adhesion proteins, lytic enzymes, and cytolytic toxins [47,48]. The presence of E. faecalis in semen is often associated with genitourinary infections, such as prostatitis or epididymitis [49], which can impair sperm quality, as demonstrated by Volz et al. (2022) [22].

Another bacterium detected in cases of reduced sperm concentration and motility through 16S RNA sequencing is Ralstonia [50]. This bacterium can colonize the male reproductive system, inducing local inflammation. In response, immune cells trigger abnormal phagocytosis of spermatozoa, leading to their extensive destruction via cytolysosomal mechanisms [51].

Although rarely pathogenic, some Aerococcus species, such as Aerococcus urinae or Aerococcus sanguinicola, have been implicated in opportunistic infections, particularly in the urogenital tract. This bacterium has been identified in several studies included in this review and shown to cause significant alterations in sperm parameters, notably reductions in sperm motility and concentration, and increased proportion of atypical forms [52].

Among the bacteria identified in the studies analyzed, researchers also noted the presence of Ureaplasma spp., a member of the Mycoplasma genus. Although its presence is often asymptomatic, it can be associated with sperm abnormalities and ART failure. In the study by Yang et al. (2020) [17], this bacterium was significantly linked to reduced sperm motility, while Okwelogu et al. (2021) [20] reported its involvement in azoospermia cases. The underlying mechanisms include local inflammatory processes, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and sperm DNA fragmentation [53].

Bacteroides is a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium primarily found in the human intestinal flora [54]. Certain strains can produce toxins or promote chronic inflammation, particularly when they proliferate excessively or migrate outside the gut. A recent study in China highlighted a potential link between gut microbiota imbalance and reduced sperm motility [55].

Gemella is a commensal bacterium that naturally colonizes the oral cavity [56,57,58]. In fertility research, only two studies, by Hou et al. (2013) [12] and Monteiro et al. (2018) [14], reported an association between Gemella and sperm alterations, including oligozoospermia, asthenozoospermia, and teratozoospermia. Although this bacterium is not commonly linked to fertility problems, its presence in the female or male urogenital microbiota could negatively impact sperm quality and the vaginal environment [58,59].

Another Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium found in seminal fluid is Sneathia spp., frequently detected in women with bacterial vaginosis, contributing to local inflammation through lipopolysaccharides (LPS) production and biofilm formation resistant to treatments [60].

Other bacteria, such as Haemophilus, Collinsella spp., Acinetobacter, Facklamia spp., Serratia spp., Pelomonas, and others, have been identified in various studies. Although these bacteria are not considered primary pathogens in male fertility disorders, some may indirectly influence sperm quality. However, current knowledge remains limited [30,61,62].

4.3. Bacteria Associated with Sperm with and Without Abnormalities

Although Lactobacillus is recognized for its probiotic properties linked to lactate production, this bacterium has also been identified in five studies as being associated with impaired sperm quality. Excessive lactate production, resulting from an imbalance in the microbial flora, can lead to accumulation of lactic acid, causing acidification of the environment and thereby impairing male fertility. This is particularly true for Lactobacillus iners, which can produce the L-isomer of lactic acid, inducing a local pro-inflammatory environment that significantly alters sperm motility. In women, an association has even been shown between Lactobacillus iners and pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably TNF-α [63].

Three studies included in this review revealed the presence of Gardnerella in semen, mainly in individuals with normal sperm parameters. In the study by García-Segura et al. (2022) [26], a decrease in Gardnerella was observed in groups with teratozoospermia and asthenozoospermia. Furthermore, Okwelogu et al. (2021) [20] concluded that there is a shared microbial equilibrium between the vagina and semen, highlighting that Gardnerella is among the bacteria common to both genital mucosae. This suggests that a healthy or dysbiotic vaginal environment can influence the partner’s seminal microbiota, and vice versa [20]. In fact, sialidases, enzymes produced by Gardnerella vaginalis, induce structural alterations in the sperm glycocalyx, disrupting its essential physiological properties. This degradation compromises several key functions, including reduced motility, increased vulnerability to external stressors, and impaired oocyte recognition, ultimately hindering fertilization [64]. Other mechanisms have also been identified, such as environmental changes, including increased pH, which create conditions unfavorable to sperm survival and motility [20]. However, the direct effect of Gardnerella on male fertility remains poorly understood and requires further research.

Staphylococcus is frequently cited in studies as a bacterium found in sperm from patients with no abnormalities. Like other commensal bacteria, it can be present under non-pathological conditions without affecting male fertility. Its pathogenicity depends primarily on concentration. According to Boitrelle et al. and the REMIC (Référentiel en microbiologie médicale), it should be considered pathogenic above 5 × 103 CFU/mL [65,66]. In eleven studies, a link was established between Staphylococcus and reduced sperm quality. This bacterium is known to impair sperm through induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage. Specifically, Staphylococcus aureus has demonstrated these effects at concentrations exceeding 104 CFU/mL, contributing to male infertility via reduced motility, decreased sperm survival, and increased DNA fragmentation [65]. These alterations directly undermine fertilizing potential and may compromise embryo development [66,67].

Similarly, Corynebacterium has been identified in seminal fluid, notably in healthy donors in the study by Hou et al. (2013) [12], as well as in the control groups of Monteiro et al. (2018) [14], Yang et al. (2020) [17], and Okwelogu et al. (2021) [20]. This Gram-positive bacillus is generally considered commensal but may become pathogenic above a certain threshold. Research shows that Corynebacterium is associated with reduced sperm concentration and motility. It has been detected in high abundance in cases of azoospermia (Hou et al., 2013 [12]; Okwelogu et al., 2021 [20]), necrozoospermia (Hannachi et al., 2018 [15]), and a low sperm DNA fragmentation index (He et al., 2024 [28]). Its mechanism involves local inflammation, increased ROS production, and sperm DNA damage. This discrepancy across studies likely reflects variations in bacterial load, as Corynebacterium may affect sperm only when present in excess. Although frequently identified in seminal microbiota, it remains understudied [68].

Another bacterium, less frequently isolated in semen, is Finegoldia, a Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium generally found in control groups with normal sperm parameters. However, as the study by Hou et al. (2013) [12] revealed, it has also been identified in individuals with oligozoospermia or asthenozoospermia. Finegoldia is part of the normal human microbial flora of the genital mucosa, upper respiratory tract, and digestive tract. Although primarily commensal, it can become an opportunistic pathogen, particularly in situations of microbiota imbalance or immune deficiency [69].

Veillonella, although rarely isolated in semen, has been detected both in control groups and in individuals with altered sperm parameters. This strictly anaerobic bacterium is part of the normal urogenital flora. The species Veillonella seminalis has been specifically found in semen, suggesting a possible role in urogenital infections or seminal microbiota composition [70]. Although its presence has been associated with fertility disorders such as oligozoospermia or even azoospermia in certain studies, it has also been found in individuals with no apparent pathology, as noted in the Hou et al. (2013) control group [12].

Acinetobacter was also reported both in control groups and in groups with altered sperm parameters. In seminal fluid, its mechanisms of action and impact on sperm remain largely unknown, and further research is needed to understand its potential role in male fertility.

4.4. Limitations

In four of the included studies, the authors used standard bacterial culture, a method commonly employed in laboratories to detect infections present in seminal fluid. Boitrelle et al. mentioned guidelines for the management of a positive sperm culture in ART, establishing pathogenicity thresholds beyond which a bacterium is considered clinically significant and must be treated [7]. From there, one major limitation of these studies lies in the fact that they rely mainly on bacterial identification without specifying the associated concentrations, which can cloud the interpretation of the results. Only qualitative criteria are reported—namely, the presence or absence of these bacteria. This likely explains why the same bacteria are found both in patients with altered sperm parameters and in those with normal semen profiles.

Standard bacterial culture has significant limitations in the identification of bacteria, as it may overlook those that require specific growth conditions or that are present in low concentrations. According to some studies, up to 50% of bacteria in certain environments remain unculturable with current techniques, reducing the ability of this method to provide a comprehensive representation of the microbiome [71].

The majority of studies used 16S rRNA gene sequencing, an approach based on the amplification and analysis of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. This region is both highly conserved among bacterial species and contains variable segments that enable their specific identification. 16S rRNA sequencing therefore offers a more comprehensive view of the microbiome, making this technique essential for studying complex microbial communities, particularly due to its ability to detect bacteria that are unculturable or difficult to isolate [72]. In addition, one of the factors that may limit the validity of the included studies is the choice of hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA that were sequenced. There are nine such regions (V1 to V9). The V3–V4 region has been shown to offer the best compromise between accuracy, coverage, and cost for taxonomic profiling of the vaginal microbiota using NGS technology. However, each hypervariable region offers different taxonomic resolution, which may influence the results obtained [73]. In the included studies, not all hypervariable regions were consistently explored, which may introduce comparative bias between studies.

Additionally, one of the main limitations of these studies is their limited sample size. The small number of patients included in most investigations reduces statistical power and compromises the ability to draw robust conclusions. This also increases the risk of biased or non-representative results.

Furthermore, biological samples such as semen are particularly sensitive to environmental contamination or contamination during laboratory handling, which can introduce bacteria unrelated to the seminal microbiome, complicating data interpretation. However, sample collection procedures were not always clearly described, introducing uncontrolled variability that may affect the reliability of the findings.

Notably, the included studies did not systematically report or adjust for key potential confounding factors, such as the female partner’s microbiota, prior antibiotic exposure, or variations in semen collection and processing techniques. The absence of these data limits our ability to fully interpret associations between seminal bacteria and sperm quality or ART outcomes.

Finally, among the limitations of this review, it is important to highlight the lack of studies in which the primary outcome is the rate of natural fertility, which remains a key goal for most patients undergoing fertility evaluation.

5. Opening and Conclusions

Providing probiotics to men with abnormal sperm parameters and a seminal microbiota containing potentially pathogenic bacteria appears to offer promising benefits. This raises two key questions: Can oral probiotics influence the composition of the sperm microbiota? Is there a functional link between the intestinal and seminal microbiota that would justify using oral probiotics to modulate seminal flora? By helping restore microbial balance and reducing oxidative stress, probiotics may contribute to normalizing sperm parameters in infertile men [74]. To date, however, no dietary supplement specifically aimed at improving male fertility includes probiotics or postbiotics.

Beyond bacteria, other microorganisms—viruses and fungi—may also influence male fertility, although these aspects remain insufficiently explored. Research on the virome (the ensemble of viruses within an ecosystem) and fertility is still limited. Available data suggest that a diverse, balanced virome may be associated with a higher chance of IVF success, whereas the presence of pathogenic viruses (such as HPV, HSV, or Polyomavirus) could reduce reproductive outcomes. In particular, HPV infection appears to be a potentially harmful factor for male fertility, negatively affecting both sperm quality and assisted reproduction results [75,76].

Similarly, the impact of the mycobiome—the fungal component of semen—on sperm quality remains largely unexplored. Few studies have investigated its role in male fertility. For example, in vitro exposure to Candida spp. has been shown to significantly reduce sperm motility and induce sperm DNA damage. Its presence also triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, potentially worsening local inflammation within the male genital tract [77].

Altogether, these findings underscore the need for a more comprehensive understanding of how the microbiome, virome, and mycobiome interact with male reproductive function. Further research is essential to clarify these complex relationships and their impact on fertility. Currently, the causes of male infertility often remain elusive, and therapeutic options are limited. The widespread use of ICSI to overcome sperm abnormalities has overshadowed alternative approaches, and microbiota analysis is still not part of standard diagnostic protocols.

Adopting a holistic approach that integrates all three components—microbiome, virome, and mycobiome—could pave the way for innovative strategies, including probiotics, sperm decontamination methods for IVF, HPV vaccination, and phage-based therapies aimed at modulating the microbiota.

This literature review highlights the influence of the seminal microbiota on infertility—an area that has long been overlooked but holds considerable promise. The discoveries already made, along with future advances, offer encouraging prospects for managing sperm abnormalities and improving the care of infertile couples undergoing assisted reproduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y. and A.J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Y. and A.J.F., writing—review and editing, R.Y., A.J.F., C.A.-V., A.L., E.S.; supervision, A.J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| CFU/mL | Colony-Forming Units per Milliliter |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ERO | Espècesréactives de l’oxygène |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex virus |

| ICSI | Intra Cytoplasmic Sperm Injection |

| IGAM | Infection of the Male Accessory Glands |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| rDNA | Ribosomal DeoxyriboNucleic |

| REMIC | Référentiel en microbiologie médicale |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SCFAs | Short Chain Fatty Acids |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Infertilité. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Hamamah, S.; Berlioux, S. Rapport sur les Causes D’infertilité—Vers une Stratégie Nationale de Lutte Contre L’infertilité,” Ministère de la Santé et de L’accès Aux Soins. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/ministere/documentation-et-publications-officielles/rapports/sante/article/rapport-sur-les-causes-d-infertilite-vers-une-strategie-nationale-de-lutte (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- “Infertilité·Inserm, La Science Pour la Santé,” Inserm. Available online: https://www.inserm.fr/dossier/infertilite/ (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Agarwal, A.; Baskaran, S.; Parekh, N.; Cho, C.-L.; Henkel, R.; Vij, S.; Arafa, M.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Shah, R. Male infertility. Lancet 2021, 397, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauduit, C.; Florin, A.; Amara, S.; Bozec, A.; Siddeek, B.; Cunha, S.; Meunier, L.; Selva, J.; Albert, M.; Vialard, F.; et al. Effets à long terme des perturbateurs endocriniens environnementaux sur la fertilité masculine. Gynécol. Obstet. Fertil. 2006, 34, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppe, H.-C.; Pilatz, A.; Hossain, H.; Diemer, T.; Wagenlehner, F.; Weidner, W. Urogenital Infection as a Risk Factor for Male Infertility. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitrelle, F.; Robin, G.; Lefebvre, C.; Bailly, M.; Selva, J.; Courcol, R.; Lornage, J.; Albert, M. Les bactériospermies en AMP: Comment réaliser et interpréter une spermoculture? Qui traiter? Pourquoi? Comment? Gynécol. Obstet. Fertil. 2012, 40, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Kitano, S.; Puah, G.R.Y.; Kittelmann, S.; Hwang, I.Y.; Chang, M.W. Microbiome and Human Health: Current Understanding, Engineering, and Enabling Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 31–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanachi, M.; Manichanh, C.; Latour, E.; Levenez, F.; Cournède, N.; Doré, J.; Melchior, J.-C. Une dysbiose du microbiote intestinal comme facteur explicatif des troubles fonctionnels digestifs observés chez les patients dénutris sévères atteints d’anorexie mentale sous assistance nutritionnelle par voie entérale. Nutr. Clin. Métabolisme 2017, 31, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Argenio, V.; Salvatore, F. The role of the gut microbiome in the healthy adult status. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 451, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvi, K.; Lacroix, J.-M.; Jain, A.; Dumitru, I.; Heritz, D.; Mittelman, M.W. Polymerase chain reaction-based detection of bacteria in semen*. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 66, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, X.; Settles, M.L.; Herring, J.; Wang, L.; Abdo, Z.; Forney, L.J.; Xu, C. Microbiota of the seminal fluid from healthy and infertile men. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 1261–1269.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, S.-L.; Chiu, C.-M.; Lin, F.-M.; Huang, W.-C.; Liang, C.; Yang, T.; Yang, T.-L.; Liu, C.-Y.; Wu, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.-A.; et al. Bacterial communities in semen from men of infertile couples: Metagenomic sequencing reveals relationships of seminal microbiota to semen quality. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.; Marques, P.I.; Cavadas, B.; Damião, I.; Almeida, V.; Barros, N.; Barros, A.; Carvalho, F.; Gomes, S.; Seixas, S. Characterization of microbiota in male infertility cases uncovers differences in seminal hyperviscosity and oligoasthenoteratozoospermia possibly correlated with increased prevalence of infectious bacteria. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 79, e12838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, H.; Elloumi, H.; Hamdoun, M.; Kacem, K.; Zhioua, A.; Bahri, O. La bactériospermie: Effets sur les paramètres spermatiques. Gynécol. Obstet. Fertil. Sénologie 2018, 46, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, D.; Pattaroni, C.; Vulliemoz, N.; Castella, V.; Marsland, B.J.; Stojanov, M. Sperm Microbiota and Its Impact on Semen Parameters. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Z.; Zhao, C.; Lei, L.; Wen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L. Potential Pathogenic Bacteria in Seminal Microbiota of Patients with Different Types of Dysspermatism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, M.; Kubera, N.S.; Singh, R. Association of Semen Bacteriological Profile with Infertility:—A Cross-Sectional Study in a Tertiary Care Center. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eini, F.; Kutenaei, M.A.; Zareei, F.; Dastjerdi, Z.S.; Shirzeyli, M.H.; Salehi, E. Effect of bacterial infection on sperm quality and DNA fragmentation in subfertile men with Leukocytospermia. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwelogu, S.I.; Ikechebelu, J.I.; Agbakoba, N.R.; Anukam, K.C. Microbiome Compositions from Infertile Couples Seeking In Vitro Fertilization, Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Methods: Any Correlation to Clinical Outcomes? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 709372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Qiu, X.-J.; Wang, D.-S.; Luo, J.-K.; Tang, T.; Li, Y.-H.; Zhang, C.-H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, L.-L. Semen microbiota in normal and leukocytospermic males. Asian J. Androl. 2021, 24, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, Y.; Ebner, B.; Pfitzinger, P.; Berg, E.; Lellig, E.; Marcon, J.; Trottmann, M.; Becker, A.; Stief, C.G.; Magistro, G. Asymptomatic bacteriospermia and infertility—What is the connection? Infection 2022, 50, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachet, C.; Prat, M.; Burucoa, C.; Grivard, P.; Pichon, M. Spermatic Microbiome Characteristics in Infertile Patients: Impact on Sperm Count, Mobility, and Morphology. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ma, M.; Chen, H.; He, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, G.; Yang, X. Interaction between Host and Microbes in the Semen of Patients with Idiopathic Nonobstructive Azoospermia. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04365-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneruso, I.; Cariati, F.; Alviggi, C.; Pastore, L.; Tomaiuolo, R.; D’Argenio, V. Metagenomics Reveals Specific Microbial Features in Males with Semen Alterations. Genes 2023, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, S.; Del Rey, J.; Closa, L.; Garcia-Martínez, I.; Hobeich, C.; Castel, A.B.; Vidal, F.; Benet, J.; Ribas-Maynou, J.; Oliver-Bonet, M. Seminal Microbiota of Idiopathic Infertile Patients and Its Relationship with Sperm DNA Integrity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 937157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wang, S.; Pan, Y.; Guo, F.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Xing, Q.; Liu, X. Characterization of the semen, gut, and urine microbiota in patients with different semen abnormalities. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1182320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ma, M.; Xu, Z.; Guo, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, P.; Liu, G. Association between semen microbiome disorder and sperm DNA damage. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00759-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osadchiy, V.; Belarmino, A.; Kianian, R.; Sigalos, J.T.; Ancira, J.S.; Kanie, T.; Mangum, S.F.; Tipton, C.D.; Hsieh, T.-C.M.; Mills, J.N.; et al. Semen microbiota are dramatically altered in men with abnormal sperm parameters. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqawasmeh, O.A.M.; Jiang, X.-T.; Cong, L.; Wu, W.; Leung, M.B.W.; Chung, J.P.W.; Yim, H.C.H.; Fok, E.K.L.; Chan, D.Y.L. Vertical transmission of microbiomes into embryo culture media and its association with assisted reproductive outcomes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2024, 49, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajpeyee, M.; Tiwari, S.; Yadav, L.B. Characterization of seminal microbiome associated with semen parameters using next-generation sequencing. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2024, 29, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvrdá, E.; Ďuračka, M.; Benko, F.; Lukáč, N. Bacteriospermia—A formidable player in male subfertility. Open Life Sci. 2022, 17, 1001–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domes, T.; Lo, K.C.; Grober, E.D.; Mullen, J.B.M.; Mazzulli, T.; Jarvi, K. The incidence and effect of bacteriospermia and elevated seminal leukocytes on semen parameters. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S.; von Wright, A. (Eds.) Lactic Acid Bacteria: Microbiological and Functional Aspects, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-429-14644-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aghamohammad, S.; Sepehr, A.; Miri, S.T.; Najafi, S.; Pourshafie, M.R.; Rohani, M. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Lactobacillus spp. as a preservative and therapeutic agent for IBD control. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Alipour, H.; Zachar, V.; Kesmodel, U.S.; Dardmeh, F. Effect of Postbiotics Derived from Lactobacillus rhamnosus PB01 (DSM 14870) on Sperm Quality: A Prospective in Vitro Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Lau, R.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, M.-H. Lactate cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium species and Megasphaera indica contributes to butyrate formation in the human colonic environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 90, e01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Yang, C. Butyrate as a Potential Modulator in Gynecological Disease Progression. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Luo, H.; Fan, B.; Xiang, Q.; Nie, Z.; Feng, S.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, R.; et al. Fluoride induces pyroptosis via IL-17A-mediated caspase-1/11-dependent pathways and Bifidobacterium intervention in testis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 172036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyshlyuk, L.S.; Milentyeva, I.S.; Asyakina, L.K.; Ostroumov, L.A.; Osintsev, A.M.; Pozdnyakova, A.V. Using bifidobacterium and propionibacterium strains in probiotic consortia to normalize the gastrointestinal tract. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 84, e256945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.D.; Van Gerwen, O.T.; Dong, C.; Sousa, L.G.V.; Cerca, N.; Elnaggar, J.H.; Taylor, C.M.; Muzny, C.A. The Role of Prevotella Species in Female Genital Tract Infections. Pathogens 2024, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Pathogenesis of Sepsis: Factors That Modulate the Response to Gram-Negative Bacterial Infection—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272523105703087?via%3Dihub (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Askienazy-Elbhar, M. Infection du tractus génital masculin: Le point de vue du bactériologiste. Gynécol. Obstet. Fertil. 2005, 33, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loesche, W.J. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 1986, 50, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L.; Bussalleu, E.; Yeste, M.; Bonet, S. Effects of different concentrations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on boar sperm quality. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 150, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berktas, M.; Aydin, S.; Yilmaz, Y.; Cecen, K.; Bozkurt, H. Sperm motility changes after coincubation with various uropathogenic microorganisms: An in vitro experimental study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2008, 40, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambaud, C.; Nunez, N.; da Silva, R.A.G.; Kline, K.A.; Serror, P. Enterococcus faecalis: An overlooked cell invader. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e0006924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Lee, G. Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern in Enterococcus faecalis Strains Isolated from Expressed Prostatic Secretions of Patients with Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis. Korean J. Urol. 2013, 54, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyaert, S.; Peeters, C.; Wieme, A.D.; Muyldermans, A.; Vandoorslaer, K.; Spilker, T.; Wybo, I.; Piérard, D.; LiPuma, J.J.; Vandamme, P. Novel Ralstonia species from human infections: Improved matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry-based identification and analysis of antimicrobial resistance patterns. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0402123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrell, D.T.; Emery, B.R.; Hamilton, B. Seminal infection with Ralstonia picketti and cytolysosomal spermophagy in a previously fertile man. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 79, 1665–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M. Aerococcus: An increasingly acknowledged human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sweih, N.A.; Al-Fadli, A.H.; Omu, A.E.; Rotimi, V.O. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Ureaplasma urealyticum infections and seminal quality in infertile and fertile men in Kuwait. J. Androl. 2012, 33, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, H.; Saier, M.H. Gut Bacteroides species in health and disease. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. Characteristics of gut microbiota in patients with asthenozoospermia: A Chinese pilot study. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Arroyo, B.; Cendejas Bueno, E.; Romero-Gómez, M.P. Gemella haemolysans meningitis. Med. Clin. 2021, 157, e347–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, H.; El Gharib, K.; Assaad, M.; Kassem, A.; Mobarakai, N. Gemella endocarditis. IDCases 2022, 29, e01597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, T.S.; Walia, M.; Wilson, H.A.; Marshall, R.W.; Andrade, A.J.; Iyer, S. Gemella haemolysans spondylodiscitis: A report of two cases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2012, 94, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valint, D.J.; Fiedler, T.L.; Liu, C.; Srinivasan, S.; Fredricks, D.N. Effect of Metronidazole on Concentrations of Vaginal Bacteria Associated with Risk of HIV Acquisition. Res. Sq. 2024, 15, e0111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, K.R.; Florova, V.; Romero, R.; Borisov, A.B.; Winters, A.D.; Galaz, J.; Gomez-Lopez, N. Sneathia: An emerging pathogen in female reproductive disease and adverse perinatal outcomes. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gendy, M.M.A.A.; Abdel-Wahhab, K.G.; Hassan, N.S.; El-Bondkly, E.A.; Farghaly, A.A.; Ali, H.F.; Ali, S.A.; El-Bondkly, A.M.A. Evaluation of carcinogenic activities and sperm abnormalities of Gram-negative bacterial metabolites isolated from cancer patients after subcutaneous injection in albino rats. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2021, 114, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, N.M.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Sola-Leyva, A.; Vargas, E.; Mendoza-Tesarik, R.; Galán-Lázaro, M.; Mendoza-Ladrón de Guevara, N.; Tesarik, J.; Altmäe, S. Assessing the testicular sperm microbiome: A low-biomass site with abundant contamination. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 43, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dai, J.; Chen, T. Role of Lactobacillus in Female Infertility Via Modulating Sperm Agglutination and Immobilization. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 620529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohadwala, S.; Shah, P.; Farrell, M.; Politch, J.; Marathe, J.; Costello, C.E.; Anderson, D.J. Sialidases derived from Gardnerella vaginalis remodel the sperm glycocalyx and impair sperm function. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.02.01.636076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, F.; Esmaeilnezhad, S.; Mehdipour Moghaddam, M.J. Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Escherichia coli: Tracking from sperm fertility potential to assisted reproductive outcomes. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2021, 48, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P.; Izuka, E.; Menuba, I.; Jegasothy, R.; Nwagha, U. Staphylococcal infections and infertility: Mechanisms and management. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 474, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Prabha, V. Human Sperm Interaction with Staphylococcus aureus: A Molecular Approach. J. Pathog. 2012, 2012, 816536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meštrović, T.; Bedenić, B.; Wilson, J.; Ljubin-Sternak, S.; Sviben, M.; Neuberg, M.; Ribić, R.; Kozina, G.; Profozić, Z. The impact of Corynebacterium glucuronolyticum on semen parameters: A prospective pre-post-treatment study. Andrology 2018, 6, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyanova, L.; Markovska, R.; Mitov, I. Virulence arsenal of the most pathogenic species among the Gram-positive anaerobic cocci, Finegoldia magna. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aujoulat, F.; Bouvet, P.; Jumas-Bilak, E.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Marchandin, H. Veillonella seminalis sp. nov., a novel anaerobic Gram-stain-negative coccus from human clinical samples, and emended description of the genus Veillonella. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3526–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaie, A.M.; Saddik, B.; Alsaegh, M.A.; Soliman, S.S.M.; Hamoudi, R.; Samaranayake, L.P. Prevalence of unculturable bacteria in the periapical abscess: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, G.; Zoetendal, A.D.L.A. The Host Genotype Affects the Bacterial Community in the Human Gastronintestinal Tract. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2001, 13, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirichoat, A.; Sankuntaw, N.; Engchanil, C.; Buppasiri, P.; Faksri, K.; Namwat, W.; Chantratita, W.; Lulitanond, V. Comparison of different hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA for taxonomic profiling of vaginal microbiota using next-generation sequencing. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Oliveira, L.C.S.; Costa, E.C.; Martins, F.D.G.; da Rocha, A.S.; Brasil, G.A. Probiotics supplementation in the treatment of male infertility: A Systematic Review. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2024, 28, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresta, C.; Noventa, M.; De Toni, L.; Gizzo, S.; Garolla, A. HPV-DNA sperm infection and infertility: From a systematic literature review to a possible clinical management proposal. Andrology 2015, 3, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, L.-F.; Liu, L.-P.; Wan, J.-X.; Duan, Q.-T.; Dian, Z.-Q.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Dong, Y.-H. Impact of human papillomavirus and coinfection with other sexually transmitted pathogens on male infertility. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 27, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrillón-Duque, E.X.; Puerta Suárez, J.; Cardona Maya, W.D. Yeast and Fertility: Effects of in Vitro Activity of Candida spp. on Sperm Quality. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2018, 19, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.