Abstract

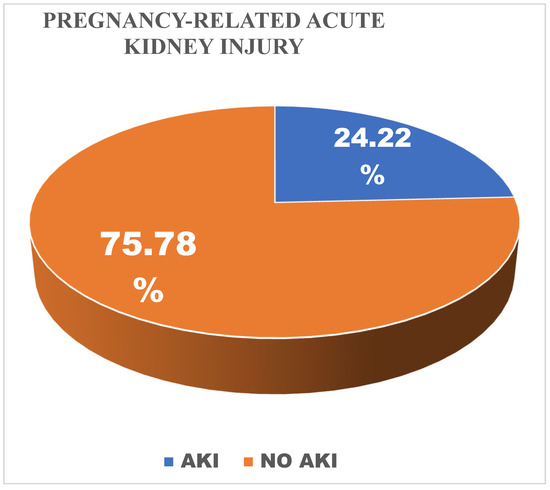

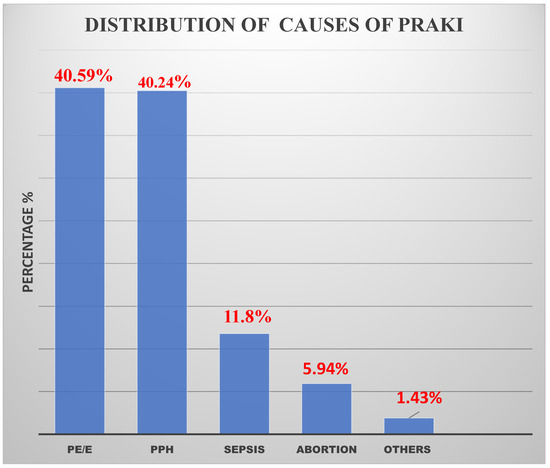

Background/Objective: Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI) remains a serious complication, with high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality, particularly in developing countries where delayed diagnosis and treatment are common. This study aimed to determine the proportion, associated risk factors, and maternal outcomes among pregnant and postpartum women at high risk of developing AKI. Methods: This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania, from May 2023 to February 2024, targeting high-risk obstetric patients. Results: Out of 4588 admissions, 420 patients were identified as being at risk of developing PRAKI. Among them, 101 (24.22%) were diagnosed with PRAKI, while 316 (75.78%) did not develop the condition. The leading associated risk factors were pre-eclampsia (40.59%) and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (40.24%), followed by sepsis (11.8%) and abortion-related complications (5.94%). Multivariate analysis revealed that living in rural areas and having a lower level of education were significantly associated with PRAKI. Patients from rural areas had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 5.37 (p < 0.001), while those with informal or primary education had an AOR of 4.21 (p = 0.048). Conclusions: The study also found that maternal mortality was significantly higher among patients with PRAKI, particularly those affected by PPH. These findings highlight the urgent need for improved management of obstetric emergencies to reduce PRAKI incidence and improve maternal outcomes in high-risk populations.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI) is a severe, life-threatening condition characterized by a sudden decline in kidney function during pregnancy or the postpartum period, leading to increased maternal morbidity, mortality, and risk of progressing to end-stage kidney disease [1,2,3,4]. Being pregnant is believed to increase the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) by 51% [4]. Despite global improvements in obstetric care and a decline in septic abortions, PRAKI continues to be a major concern in developing countries, including many parts of Africa. In these settings, PRAKI is often underreported and insufficiently studied, despite having a significantly higher prevalence than in developed nations [1,5,6,7]. In developed countries, the prevalence of PRAKI is between 1.0 and 2.8%, while in developing regions, it ranges from 4% to as high as 26% [7,8]. This high rate is largely due to inadequate perinatal care and the poor management of pregnancy-related complications such as obstetric hemorrhage, sepsis, pre-eclampsia, and septic abortion [2,9]. In Africa, obstetric causes are the second leading cause of acute kidney injury, with obstetric AKI accounting for 5–27% of PRAKI cases, up to 100 times more frequently than in wealthier nations [10]. In Tanzania, previous studies have shown a PRAKI prevalence of 8.6% at Muhimbili National Hospital [3], with 10.5% and 54.7% of cases at Bugando Medical Centre linked to pre-eclampsia [5,11], and in Dodoma, the prevalence was so low that about 1.27% of all pregnant female patients who attended for delivery over four years had PRAKI [12]. Although certain risk factors for PRAKI in Tanzanian women are known, data on the actual burden and maternal outcomes of the condition remain limited. This has led to a need for targeted research, such as the current study at Bugando Medical Centre, which aims to assess the prevalence, contributing factors, and outcomes associated with PRAKI. Such studies are crucial in informing policy and improving clinical practices, especially in resource-limited settings where maternal health systems are strained. Ultimately, understanding the burden of PRAKI is essential in reducing preventable maternal deaths and enhancing healthcare interventions for high-risk obstetric populations.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design, Sample Size, and Study Area

This was a prospective cohort study involving 420 pregnant and postpartum women at risk of developing acute kidney injury (AKI). The study was conducted at Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania, over nine months.

2.2. Study Population

The study population comprised patients in whom obstetrical complications occurred during pregnancy, delivery, or puerperium. In this study, we included women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, severe anemia, hemorrhages, HELLP syndrome, and infections.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Participants with obstetric complications were selected using convenience sampling as they met the inclusion criteria until the required sample size of 420 was achieved.

Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI) was diagnosed based on the KDIGO Criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

KDIGO criteria.

All women had their serum creatinine levels tested; those with elevated levels (>82 µmol/L) were further assessed and managed by obstetricians and nephrologists.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Data were gathered using a questionnaire and analyzed using STATA version 15. Chi-square tests were used to identify significant associations (p < 0.05), and multivariate logistic regression was applied to evaluate the strength of those associations.

3. Results

3.1. Social Demographic Characteristics of Patients

A total of 420 patients were enrolled in this study. The majority were aged 25–34 (50%). The mean age of the patients was 29.8 ± SD6.6. Most of these patients were admitted to the general ward (56.2%). The majority were residing in a town (69.8%). Over fifty per cent had secondary and college education (57.7%). Ninety-four per cent were married. About two thirds had more than two parities (63.5%). A total of 43.1% delivered through Caesarean sections (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

3.2. Distribution of PRAKI and Stages Among Women Who Developed Acute Kidney Injury

Among 420 patients identified as being at risk of developing PRAKI during the study period, 101 (24.22%) had PRAKI, while 316 (75.78%) had no PRAKI (Figure 1). About 23% had AKI stage I, 15.84% had AKI stage II, and 60.40% had AKI stage III (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Pregnancy Related Acute Kidney Injury.

Figure 2.

Pregnancy Related Acute Kidney Injury stages.

3.3. Distribution of Causes of Pregnancy-Related Acute Kidney Injury

In terms of contribution to PRAKI risk, pre-eclampsia and PPH had the greatest proportion, 40.59% and 40.24%, respectively, followed by sepsis at 11.8% and abortion at 5.94%, and less than 1.43% of risk was due to other issues (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution on causes of Pregnancy –Related Acute Kidney Injury.

3.4. Maternal Outcomes of Patients Who Developed PRAKI

Among the patients who developed pregnancy-related acute kidney injury, 78 out of 101 (77.22%) made a complete recovery either with or without dialysis, 32 (41.03%) recovered with dialysis, and 46 (59.97%) made a complete recovery without dialysis, while 5 out of 101 (4.95%) developed chronic kidney disease (CKD) and remained dialysis-dependent, and 19 out of 101 with PRAKI (18.13%) died during the study period (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Maternal outcomes of patients who developed PRAKI.

3.5. Factors Associated with the Development of Acute Kidney Injury Among High-Risk Women

Bivariate analysis revealed that residence, education level, marital status, parity, and the ward of admission were associated with PRAKI. However, in the multivariate analysis, only residence, education, and ward of admission remained significantly associated with PRAKI. Specifically, patients living in rural areas had a significantly higher risk of developing PRAKI compared to those in urban areas (AOR = 3.09; 95% CI: 1.65–5.81; p < 0.0001). Individuals with only a primary education were at a higher risk of developing AKI than those with a college education (AOR = 4.2; 95% CI: 0.05–0.98; p = 0.048). Additionally, patients admitted to the HDU or ICU were more likely to experience severe complications compared to those in general wards, with adjusted odds ratios of 3.66 (95% CI: 2.04–6.56; p < 0.0001) and 10.5 (95% CI: 4.07–27.12; p < 0.0001), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the development of acute kidney injury among high-risk patients.

4. Discussion

This study investigated prevalence, outcomes, and associated factors in pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI) among obstetric patients at Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), a major referral hospital in Tanzania. Out of 4588 obstetric admissions during the study period, 420 patients presented with obstetric complications. Among these, the prevalence of PRAKI was found to be 24.22%, which is significantly higher than figures reported in comparable regional and international studies.

The PRAKI prevalence at Bugando Medical Centre (24.22%) exceeds that reported in other African studies, such as one from Malawi, which found an 8.1% prevalence [13]. Several factors may explain this disparity. Firstly, BMC serves as a tertiary referral centre, receiving complex and severe cases from eight regions—Mwanza, Shinyanga, Geita, Kagera, Kigoma, Mara, Simiyu, and Tabora. Approximately 49.28% of the PRAKI patients were referrals, and 60.4% of cases were already in stage 3 of AKI on arrival. Secondly, most patients came from rural areas where the health infrastructure is limited, referral systems are delayed, and access to timely medical care is poor. These elements likely contributed to the higher number and severity of PRAKI cases observed. However, the prevalence was lower compared with a previous study that was performed at Bugando Medical Centre among pre-eclamptic–eclamptic patients, which was 54.7% [11]. The difference may be explained by the study population; in our study, we included all patients with obstetrics complications, while the previous study included only patients with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.

The leading causes of PRAKI in the study were hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (40.59%) and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (40.24%). Sepsis (11.8%) and abortion (5.94%) were other contributing factors. These findings are in alignment with previous studies conducted in Egypt, Malawi, and Nigeria, which also identified hypertensive disorders and hemorrhage as leading causes [2,13,14,15]. At Muhimbili National Hospital, pre-eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and postpartum hemorrhage were common causes of PRAKI [3].

The study recorded mixed outcomes for patients diagnosed with PRAKI. A substantial portion, 77.22%, fully recovered, either through dialysis or conservative management. This high recovery rate is attributed to early and collaborative intervention by gynecologists and nephrologists. Notably, patients who could not afford dialysis were granted exemptions for the first three sessions, facilitating timely treatment.

Despite these successes, 4.95% of patients developed chronic kidney disease (CKD) by the end of the follow-up period, and overall, 11.9% transitioned to CKD regardless of the number of dialysis sessions. This study underscores the importance of early dialysis initiation in improving recovery outcomes.

These maternal outcomes are supported by different reports; a review study indicated recovery rates between 53.1 and 90%, CKD progression in 4–9%, and maternal mortality ranging from 0 to 34% [7]. In a study in Egypt, about 62.5% of patients fully recovered, 37.5% developed CKD, and 22.5% died [2]. In a study in Nigeria, 72.5% recovery and 17.5% mortality were recorded [15], while in Malawi, a study recorded a full recovery for 84.6%, no CKD, and no maternal deaths [13].

PRAKI is an important cause of maternal mortality among younger women in countries with limited resources [16].

Interestingly, while pre-eclampsia was the most common cause, the highest number of maternal deaths in the study occurred in patients whose AKI was triggered by PPH, unlike in the study performed in Nigeria, where 50.1% of maternal mortality was due to pre-eclampsia [17]. This aligns with the unpredictable and emergent nature of PPH compared to pre-eclampsia, which can often be monitored and managed more proactively. The maternal mortality among patients with PRAKI in Africa is alarmingly higher; in a systematic review, the maternal mortality ranged between 0 and 34.4% [7]. Higher mortality rates may be explained by the severity of the disease, with late intervention, especially delays in receiving haemodialysis on time, a lack of ICU space, and other comorbidities.

Other contributing factors to mortality included severe obstetric complications leading to ICU admissions, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), shock, and eclamptic stroke.

This study identified three major factors associated with an increased risk of PRAKI:

Rural Residence: Patients from rural areas had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 5.37 (95% CI 0.13–6.93, p < 0.001). These individuals often face challenges such as poor infrastructure, delayed referrals, and limited access to quality healthcare. These conditions increase the likelihood of developing PRAKI due to delayed diagnosis and treatment. The same observation was reported in Egypt, where the majority of patients with PRAKI were from rural areas [2]. There is a need for early intervention during the antenatal period, especially in rural areas, to prevent obstetric complications like pre-eclampsia that can lead to PRAKI. It is essential that a creatinine test be performed on every visit to detect early renal changes [18]. Low Education Level: Patients with informal or only primary education had an AOR of 4.21 (95% CI 0.93–18.94, p = 0.048). Limited education correlates with low health literacy and a reduced likelihood of seeking timely medical care, which can result in complications like AKI going unnoticed until they become severe. A similar observation in a study conducted in Muhimbili was that many patients who had obstetric complications and later developed PRAKI had a low level of education [3]. ICU Admission: Patients who were admitted to the ICU had an AOR of 10.5 (95% CI 4.07–27.12, p = 0.001), indicating a strong correlation between critical illness and the likelihood of developing PRAKI. These patients generally presented with multiple, severe obstetric complications. These findings are consistent with other research; a study carried out in Somaliland showed that about 26% of patients with PRAKI needed ICU admissions [19]. Likewise, a study conducted in India showed that many patients with PRAKI had multi-organ failure and needed ICU admission, with an average stay of 8 days [20].

4.1. Conclusions and Implications

The study at BMC presents crucial insights into prevalence, outcomes, and associated factors in PRAKI in a tertiary referral setting. With a prevalence rate significantly higher than in other African and global studies, the findings underscore the need for systemic improvements in maternal care. The disproportionately high mortality in the PPH group emphasizes the urgency of enhancing emergency obstetric response capabilities, especially in lower-level health facilities.

This study highlights the effectiveness of early dialysis intervention in improving recovery, as well as the critical role of multidisciplinary collaboration in managing PRAKI. Additionally, it brings to light socio-demographic and healthcare access disparities that influence PRAKI risk, pointing to the necessity for targeted public health interventions in rural and undereducated populations.

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first of its kind in Tanzania and East Africa to evaluate long-term maternal outcomes following pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI), incorporating a 3-month follow-up period. A key strength is its pioneering nature in the regional context and its longitudinal approach to assessing outcomes.

However, the study faced limitations. Notably, it was difficult to determine participants’ pre-pregnancy kidney function due to the absence of baseline serum creatinine measurements, which are not part of standard antenatal care in the region. Additionally, since the research was conducted at a single tertiary referral centre, its findings may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings or regions.

Author Contributions

K.B., F.M. and L.R. developed the concept and proposal of this research; K.B. and L.R. participated in data collection and the management of the patients; D.M., R.K. and E.N. participated in data analysis and manuscript review; and K.B. and F.M. participated in manuscript writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the study was partly covered by the lead researcher. Patients requiring dialysis were expected to manage the remaining treatment costs. However, the first three dialysis sessions were provided free of charge to those unable to afford them, with additional support facilitated through social welfare applications.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research received ethical approval from the CUHAS/BMC Research Ethics and Review Committee under certificate number CREC/693/2023 (2023-07-20). Institutional permission was obtained from BMC, and all participants signed a documented consent form ensuring confidentiality and voluntary participation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data used and analyzed in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed with unwavering support and guidance from various contributors and institutions. The author expresses deep gratitude to God for spiritual strength and to the supervisors, Fridolin Mujuni and Ladislaus Ludovick of the Catholic University School of Medicine, for their consistent supervision, direction, and encouragement throughout the research process. Additional appreciation goes to Frank Francisca M. Muumbe, Mathias Njau, and Benson Kidenya for their expert insights that significantly contributed to the study’s development.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no competing interests declared by the authors, ensuring objectivity and transparency in the presentation of this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| BMC | Bugando Medical Centre |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| HELLP | Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and Low Platelets |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| PPH | Postpartum hemorrhage |

| PRAKI | Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury |

References

- Cerdá, J.; Bagga, A.; Kher, V.; Chakravarthi, R.M. The contrasting characteristics of acute kidney injury in developed and developing countries. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2008, 4, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaber, T.Z.; Shemies, R.S.; Baiomy, A.A.; Aladle, D.A.; Mosbah, A.; Abdel-hady, E.S.; Sayed-Ahmed, N.; Sobh, M. Acute kidney injury during pregnancy and puerperium: An Egyptian hospital-based study. J. Nephrol. 2021, 34, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggajo, P.; Appollo, E.; Bramania, P.; Basil, T.; Furia, F.; Mngumi, J. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Short-term Outcomes of Acute Kidney Injury in Women with Obstetric Complications in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Tanzan. Med. J. 2022, 33, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; He, W.; Li, Y.; Xiong, M.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Jia, L.; Yuan, S.; Nie, S. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in hospitalized pregnant women in China. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndaboine, E.M.; Kihunrwa, A.; Rumanyika, R.; Im, H.B.; Massinde, A.N. Maternal and perinatal outcomes among eclamptic patients admitted to Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2012, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prakash, J.; Ganiger, V. Acute kidney injury in pregnancy-specific disorders. Indian J. Nephrol. 2017, 27, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, A.S.; Shemies, R.S. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury in the African continent: Where do we stand? A systematic review. J. Nephrol. 2022, 35, 2175–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrand, A.M.; Liu, K.; Shariff, S.Z.; Ray, J.G.; Sontrop, J.M.; Clark, W.F.; Hladunewich, M.A.; Garg, A.X. Characteristics and outcomes of AKI treated with dialysis during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 3085–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X.; Yan, T. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, J.; Kumar, H.; Sinha, D.; Kedalaya, P.; Pandey, L.; Srivastava, P.; Raja, R.; Usha. Acute renal failure in pregnancy in a developing country: Twenty years of experience. Ren. Fail. 2006, 28, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njau, M.; Mujuni, F.; Matovelo, D.; Ndaboine, E.; Kiritta, R.; Rudovick, L. Acute Kidney Injury: Magnitude and Predictors of Maternal Outcomes among Pre-Eclamptic and Eclamptic Women in Mwanza, Tanzania. East Afr. Health Res. J. 2025, 8, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Shija, K.; Ibrahim, H.; Jumbe, S.; Lugoba, B.; Kibusi, S.M.; Chandika, A. Clinical Presentation and Treatment Outcomes of Pregnancy-Related Acute Kidney Injury among Pregnant Women Admitted at the Benjamin Mkapa Hospital in Tanzania. Open J. Nephrol. 2024, 14, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, W.R.; Hemmilä, U.K.; Craik, A.L.; Mandula, C.J.; Mvula, P.; Msusa, A.; Dreyer, G.; Evans, R. Incidence, aetiology and outcomes of obstetric-related acute kidney injury in Malawi: A prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, K.S.; Warda, O.; Elshamy, M.; Abdelhafez, M.S. Pregnancy Related Acute Kidney Injury: A Single Tertiary Care Center Experience. Evid. Based Women’s Health J. 2024, 14, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awowole, I.O.; Omitinde, O.S.; Arogundade, F.A.; Bola-Oyebamiji, S.B.; Adeniyi, O.A. Pregnancy-related acute kidney injury requiring dialysis as an indicator of severe adverse maternal morbidity at a tertiary center in Southwest Nigeria. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 225, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillén, A.O.; Shemies, R.S.; Ankawi, G.A.; Jesudason, S.; Piccoli, G.B. Women should not die of pregnancy-related acute kidney injury (PRAKI): Revealing the underwater iceberg of maternal health. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waziri, B.; Umar, I.A.; Magaji, A.; Umelo, C.C.; Nalado, A.M.; Wester, C.W.; Aliyu, M.H. Risk factors and outcomes associated with pregnancy-related acute kidney injury in a high-risk cohort of women in Nigeria. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccoli, G.B.; Chatrenet, A.; Cataldo, M.; Torreggiani, M.; Attini, R.; Masturzo, B.; Cabiddu, G.; Versino, E.; Kidney and Pregnancy Study Group of the Italian Society of Nephrology. Adding creatinine to routine pregnancy tests: A decision tree for calculating the cost of identifying patients with CKD in pregnancy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rage, H.I.; Jha, P.K.; Hashi, H.A.; Abdillahi, N.I. Pregnancy-Related AKI: A Tertiary Care Hospital Experience in Somaliland. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Trivedi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Sharma, A.; Sinha, T.; Boipai, P.; Kumari, S. Study on Incidence of Pregnancy-related Acute Kidney Injury and Its Associated Risk Factors and Outcomes: In Preponderant Tribal State of India. Ann. Afr. Med. 2025, 24, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).