Abstract

Background: Preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic diseases (PGT-P) is a reproductive technology that has made it possible to assign risk scores to embryos for various complex polygenic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, breast cancer, and schizophrenia. Whether there is public interest in utilizing PGT-P and what public opinions are regarding this technology is unknown. Therefore, the objective of our study was to evaluate the opinion of the general United States (US) public regarding PGT-P. Methods: A web-based questionnaire consisting of 25 questions was administered to a nationally representative sample of adult US residents according to age and sex. The survey contained a description of PGT-P, followed by questions with Likert-scale responses ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Results: Of the 715 respondents recruited, 673 (94%) completed the survey. Most respondents agreed that use of PGT-P is ethical (54%), and another 37% were neutral; however, approximately 9% of respondents disagreed and were opposed to the use of PGT-P. Those that opposed PGT-P cited that it was “unethical” (46%) or “not natural” (39%), believed children could be negatively affected (31%), or stated that it went against their religion (15%). The majority of respondents did not know whether PGT-P was safe for embryos (68%) or children (67%) and felt that anyone should be able to utilize it (53%). Conclusions: Participants who were younger, were Atheist, or were Democrats were more likely to agree that “PGT-P is ethical”. This study identified that more than half of respondents supported the use of PGT-P. However, concerns regarding its safety and ethical implications persist.

1. Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic diseases (PGT-P) is a reproductive technology that has made it possible to assign risk scores to embryos for various complex polygenic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, breast cancer, and schizophrenia as well as for traits like height and intelligence [1]. The technology is derived from large-scale genome-wide association studies that have scanned thousands of genomes from individuals and uncovered variants associated with certain conditions [2]. With this technology, polygenic risk scores (PRSs) are applied from the genetic material of an embryo biopsy. Genetic companies offer PRSs to prospective parents for disease and trait selection, although this market is unregulated. Whether embryos should be selected based on their PRS remains an ethical and scientific debate [3,4]. Some argue that due to reproductive liberty and autonomy, the technology should be considered ethical, while others believe that this testing provides patients with an incomplete or misleading risk prediction due to genetic or environmental interactions that may change the risk score over time. Additionally, PRS results may add complex counseling requirements for physicians and genetic counselors while also presenting difficult choices to prospective parents as to which embryo is considered “best”. Other concerns include societal misinterpretation of risk perception (i.e., absolute vs. relative risk) as well as the technology having limited availability for patients of certain ethnicities [1].

To date, there has been limited literature assessing whether there is public interest in utilizing PGT-P and what public opinions are regarding this technology [5,6,7]. The purpose of this study is to assess the opinions and attitudes of the general United States (US) public regarding PGT-P, including its clinical utility and ethical use and the perceived safety of this emerging technology.

2. Methods

A survey (File S1) with an estimated respondent time of 5 min was distributed through SurveyMonkey, a professional online survey company. SurveyMonkey recruits its population from a diverse group who electively complete surveys via an application, rewarding them monetarily or via a donation to a charity of their choice. Inclusion criteria for survey participation were US citizenship and age ≥18 years. A nationally representative sample of individuals was obtained by SurveyMonkey according to US demographic characteristics, including age and sex from 1 March 2022 to 10 March 2022. The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board approved this study (#22-0157; 1 March 2022).

The questionnaire consisted of 25 questions and was developed and tested by the authors who have experience in survey-based studies. The survey was modeled after a similar study assessing the US general public perception of uterine transplantation [8].

The survey began with an explanation of PGT-P, followed by questions with Likert-scale responses ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Perceptions of the safety, efficacy, cost, and utilization of PGT-P were asked, followed by demographic questions. If respondents disagreed with the use of IVF for any reason, the survey concluded, and those responses were not included in the final analysis. If respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with a prompt, a follow-up question was asked to assess the primary reason for disagreement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R v 3.6.3. Counts and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables. The mean ± standard deviation or the median/interquartile range [IQR] was used to summarize the distribution of continuous normal and non-normal variables, respectively. Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the association between the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and perception regarding PGT-P.

3. Results

Of the 715 respondents recruited, 673 (94%) completed the survey. Thirty-eight of those who completed the questionnaire disagreed or strongly disagreed with physicians performing IVF and were excluded from final analysis. Two respondents were excluded due to incomplete answers. Thus, the final sample included 633 (88%) respondents. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

Approximately half of the included respondents felt that anyone should be able to utilize PGT-P, while 15.3% thought that only patients using donor gametes to create embryos should be able to use PGT-P. Approximately one-quarter (22.2%) of the respondents felt that patients with a personal or family history of certain diseases should be able to utilize PGT-P (Table 1). Half of respondents knew at least one person who used infertility treatment, and 60.3% reported that they knew someone who had infertility.

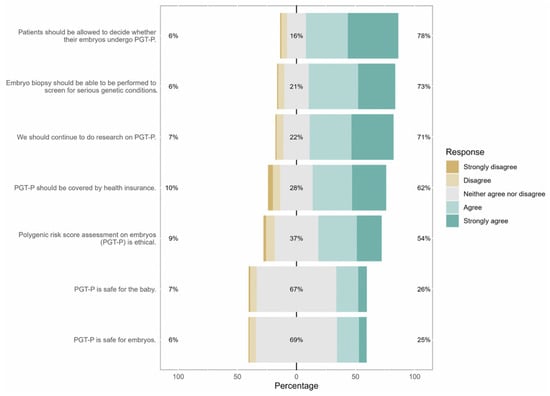

Most respondents (73%) supported and very few (6%) opposed the use of PGT for detection of aneuploidy (PGT-A) or monogenic disorders (PGT-M). Seventy-eight percent of respondents felt that prospective parents should be allowed to decide whether their embryos undergo PGT-P. Most respondents agreed that use of PGT-P is ethical (54%), and another 37% were neutral; however, 9% of respondents disagreed and were opposed to the use of PGT-P (Figure 1). Detailed responses are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Figure 1.

Responses to Likert-scale items. Percentages on the right represent the sum of responses for agree and strongly agree. Percentages on the left represent the sum of responses for disagree and strongly disagree. Percentages in grey represent those that were neutral and responded neither agree nor disagree.

Those who opposed PGT-P cited that it was “unethical” (46%) or “not natural” (39%), believed children could be negatively affected (31%), or cited that it went against their religion (15%). Sixty-two percent of respondents believed PGT-P should be covered by insurance, while 10% did not. The majority of respondents did not know whether PGT-P was safe for embryos (68%) or children (67%). Most respondents (71%) felt that research on PGT-P should continue.

When asked about perceptions regarding the risk of PGT-P, only 3.5% of respondents had no concerns. Those who did report concerns cited potential danger to the embryo (48%) as the most common reason, followed by potential risk to the baby (43%), ethical concerns (23%), and lack of effectiveness (17%). Table 2 lists free response answers to concerns regarding PGT-P.

Table 2.

Free Response Answers to Concerns Regarding PGT-P.

Participants who were younger (age <45 y vs. ≥45 y, OR:0.68, p = 0.04), were Atheist (vs. Christian non-Catholic, OR:1.93, p = 0.006), completed higher education (OR: 1.24, p = 0.0009), or were Democrats (vs. Libertarians, a party that promotes limiting the control of the government), OR: 0.50, p = 0.029) were more likely to agree that “PGT-P is ethical”. A one-grade increase in education was associated with a 25% increase in the odds of choosing a higher score on the Likert scale (OR: 1.24, p = 0.009). Respondents who answered that it is important to have a child free of disease (OR: 2.41, p < 0.001) or believed PGT-P was safe (OR: 7.37, p < 0.001) were more likely to support PGT-P use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ordinal logistic regression for factors associated with the response to “PGT-P is ethical”.

Sixty-two percent of respondents felt that PGT-P should be covered by insurance. Those that identified as females were more likely than males to support insurance coverage for PGT-P (OR: 0.71, p = 0.38), as were Democrats vs. Republicans (OR: 0.25, p < 0.001) or vs. Libertarians (OR: 0.25, p < 0.001). Respondents who were Hindu were approximately four times more likely to agree that insurance should cover the cost of PGT-P compared with Christian non-Catholics (OR: 3.59, p = 0.015), as were those of “Other” religious affiliations (OR:2.07, p = 0.028) (Supplemental Table S2). When asked about cost, 42% of respondents stated that they would be willing to pay USD 200−500/embryo for PGT-P, while 35% reported that they would not pay for it at all.

4. Discussion

This study adds to the literature exploring public perception of those supporting IVF regarding the utilization of PGT-P. Our study found that 54% of respondents believed the use of PGT-P is ethical. Those who disagreed with the use of PGT-P reported concerns regarding safety, technological uncertainty, and ethical use. However, most believed research regarding this technology should continue.

Previous literature on PGT-P has focused on opinions regarding its use from a variety of specialists [3,9,10]. For example, a recent study gathered the collective viewpoints of lawyers, ethicists, geneticists, genetic counselors, and reproductive specialists regarding PRS [10]. They raised numerous concerns regarding PRS utilization, including how it may increase the number of people who seek ART services (i.e., those specifically wanting to utilize PRS for embryo selection), which may in turn increase the number of usable embryos made available. In addition, they noted that physicians could face challenges explaining PRS results effectively to patients. They concluded that professional guidelines for best practice of PGT-P are urgently needed [11].

Previous studies exploring public attitudes towards PGT-P have revealed a complex interplay between optimism, ethical concern, and variable comprehension. Meyer et al. (2023) conducted a nationally representative US survey and found that approximately 48–53% of respondents found PGT-P morally acceptable under certain conditions, though enthusiasm varied depending on the intended use (e.g., health-related vs. trait selection) [5]. This percentage is similar to our findings. Similarly, Furrer et al. (2024) surveyed US adults and reported that while 72% supported PGT-P for reducing the risk of common diseases, only 36% favored its use for non-medical traits such as height or intelligence [7]. Both studies highlight that while public interest is high, understanding of the limitations remains low.

Whether PRS for embryos will become a standard of care tool to enable patients to increase the chance of having a healthy child or whether ethical considerations are, at present, too concerning for this technology to evolve remain unanswered questions. PRS may give parents the potential to lower the chance of their offspring developing certain conditions. However, due to the limited research currently available, its future utilization is uncertain, and longitudinal studies are needed. In addition, whether environmental or lifestyle factors may affect PGT-P results and alter genetic make-up later in life is unknown and may cause the test to be invalid. A recent article by Polyakov et al. reviewed the current studies on PGT-P and concluded that the clinical validity and utility of the test is questionable, and the concordance of results with post-natal evaluation with years of follow-up is warranted [10].

When asked about who should use PGT-P, most respondents (53%) believed anyone should be able to use it, 22% felt that only patients with a personal or family history of conditions should utilize PGT-P, and 15% reported that only patients who utilize donor gametes should access the technology. An ongoing clinical trial is underway for patients undergoing IVF with PGT-A to determine patients’ interest in the utilization of PGT-P (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04528498). Preliminary results from this study have reported that half of patients elected to use PGT-P while simultaneously pursuing PGT-A [12]. This study will undoubtedly aid in determining the reasons why some patients would choose PGT-P and help to delineate an appropriate patient population for counseling. Additionally, a study evaluating public attitudes towards PRS in the medical (personalized medicine) versus non-medical context (employment and insurance settings) found that most believed that health care institutions should be able to utilize PRS to study disease outcomes and reproductive decision making [12]. Respondents rated PRS as most permissible for sperm and egg donor selection, followed by embryo selection. When asked which traits should be applied to predict PRS, support was greatest for disease (schizophrenia and diabetes) and lowest for non-disease physical traits such as height and skin tone [13]. Perhaps PGT-P could be useful for donor-conceived embryos, as federal regulation is not currently mandated for donor background medical checks. Obtaining PRS for embryos in these circumstances may provide reassurance to prospective parents utilizing donor gametes regarding embryo selection prior to transfer to reduce the risk of polygenic conditions to their offspring.

The complicated nature of PRS creates challenges for providers to educate and counsel their patients appropriately. PRS may create difficult decisions for parents in choosing between transferring embryos with a concerning level of PRS or not transferring an embryo at all due to a limited number of usable embryos [10].

Concerns regarding this technology with respect to the safety of the embryo and the fetus were addressed by two thirds of respondents. This is understandable given the uncertainty of an emerging technology. In fact, PGT-P is illegal in the United Kingdom according to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority due to limited clinical validity of the tests. Moreover, a recent study evaluating media coverage on PGT-P also found that the well-being of the future child was an utmost concern in addition to embryo selection for non-medical traits, reproductive liberty, and, most importantly, validity of the test [14]. Forzano et al. (2021) stated that there is no clinical research on PGT-P that has reported its diagnostic effectiveness on embryos, and therefore, it should not be offered to the public [10]. One company published their test’s efficacy, but other companies have yet to do so [15]. Our results found that those who believed it was important to have a child free of disease or believed PGT-P was safe were more likely to support PGT-P use. If and when more studies reflecting the safety and efficacy of PGT-P are published, it is yet to be determined whether public support of this new technology will grow.

Regarding cost, 62% of respondents felt that health insurance should cover the cost of testing. Respondents who were female vs. male, Hindu vs. Christian non-Catholic, and Democrats vs. all other political party affiliations were more likely to support insurance coverage of PGT-P. In addition, the perceived safety of the technology and the desire to have a child free of genetic disease were strong influencers of support of insurance coverage. Participants in favor of insurance coverage may understand the potential value that genetic testing could have on public health and disease prevention.

A foremost ethical concern involves inequitable access to PGT-P and whether this may increase social disparities. Currently, most PRS are validated in individuals of European ancestry, and their accuracy and clinical utility in other ancestral groups remain limited due to underrepresentation in genomic research [16]. Another concern is that PGT-P could be used to diminish what may be considered “undesirable traits” from certain demographic populations. For example, choosing embryos based on skin color, height, or facial features has the potential to exacerbate racial stereotypes [17].

A strength of our study is that it is the first to ascertain the public opinion of those who support IVF regarding emerging PGT-P technology and that the survey respondents represent a wide and diverse national sample of the US population. A limitation is that participation in this study required respondents to be literate in English and have internet access; as such, the findings are likely not generalizable to the entire population who may be illiterate or not have access to SurveyMonkey. We excluded from the analysis those respondents who disagreed with the use of IVF for any indication; this likely eliminated respondents who would have disagreed with the use of PGT-P. We did not evaluate pre-existing knowledge of PGT-P, as ascertaining public opinion was the primary goal of this study. Similarly, it is important to consider that respondents’ understanding of relative vs. absolute risk with regard to PRS score results could not be determined based on this survey study alone. Answers in the survey went from agree to disagree, which may have caused bias as well. It is also important to acknowledge that while a majority answered that they did not know about the safety about PGT-P, a majority of respondents still responded that it was ethical. Future surveys with more information regarding the safety of embryo biopsy is needed. In addition, it may not have been clear from the introduction to the survey that those who would utilize PGT-P would need to use IVF. While the purpose of the study was to understand public’s opinion on PGT-P, our survey asked whether respondents felt the technology was ethical without the authors explicitly raising all potential ethical issues that are involved. While this is a limitation to our study, our goal was for the lay public to formulate their opinions based on the basic information which was provided to them, as the public is not always privy to the complex ethical issues surrounding new technologies. Future studies with more ethical information regarding PGT-P given to the public are warranted to enable the public to understand the issues at hand. In addition, future studies involving respondents with pre-existing knowledge of PGT-P will be helpful.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that more than 50% of the US public who support IVF believed PGT-P is ethical and that anyone should be able to utilize it. Although all ethical issues with this technology were not discussed in the survey introduction, respondents were able to formulate their own opinions based on the basic information that was provided to them regarding PGT-P. However, concerns regarding its safety and ethical implications persist. Prospective parents as well as the public must be properly counseled regarding the risk and limitations of PGT-P in its current state. Continued societal discussion as well as institutional guidelines for the use of this technology is of vital importance. Future work that continues to measure public perception of this emerging technology is essential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/reprodmed6030019/s1. Table S1: Responses to PGT-P Likert scale items; Table S2: Ordinal logistic regression for factors associated with the response to “PGT-P should be covered by health insurance”; File S1: Survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and R.H.G.; methodology, A.P. and R.H.G.; formal analysis, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., C.B. and L.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.H.G.; supervision, R.H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board approved this study (#22-0157; 1 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study were presented at the 2022 American Society for Reproductive Medicine Congress and published in the Fertility and Sterility Abstract Supplement (DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.08.097).

Conflicts of Interest

Alexandra Peyser, Cailey Brogan, Lilli Zimmerman and Randi H. Goldman were employed by Northwell. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Turley, P.; Meyer, M.; Wang, N.; Cesarini, D.; Hammonds, E.; Martin, A.; Neale, B.; Rehm, H.; Wilkins-Haug, L.; Benjamin, D.; et al. Problems with using polygenic scores to select embryos. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treff, N.R.; Savulescu, J.; de Melo-Martín, I.; Shulman, L.P.; Feinberg, E.C. Should preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disease be offered to all-or none? Fertil. Steril. 2022, 117, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, M. The controversial embryo tests that promise a better baby. Nature 2022, 609, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.N.; Tan, T.; Benjamin, D.J.; Laibson, D.; Turley, P. Public views on polygenic screening of embryos. Science 2023, 379, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M.; Siddiqui, N.; Behr, B.; Chandramohan, D.; Zhang, Q.; Suer, F.; Xia, Y.; Podgursky, B. Patient perspectives after receiving simulated preconception polygenic risk scores (Prs) for family planning. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2025, 42, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furrer, R.A.; Barlevy, D.; Pereira, S.; Carmi, S.; Lencz, T.; Lázaro-Muñoz, G. Public attitudes, interests, and concerns regarding polygenic embryo screening. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2410832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariton, E.; Bortoletto, P.; Goldman, R.H.; Farland, L.V.; Ginsburg, E.S.; Gargiulo, A.R. A survey of public opinion in the United States regarding uterine transplantation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forzano, F.; Antonova, O.; Clarke, A.; de Wert, G.; Hentze, S.; Jamshidi, Y. The use of polygenic risk scores in pre-implantation genetic testing: An un- proven, unethical practice. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 30, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyakov, A.; Amor, D.J.; Savulescu, J. Polygenic risk score for embryo selection-not ready for prime time. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.; Carmi, S.; Altarescu, G. Polygenic embryo screening: Four clinical considerations warrant further attention. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J.; Marin, D.; Duffy, L.; Chen, S.H.; Treff, N.R. Rate of patients electing for polygenic risk scores in preimplantation genetic testing. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, e267–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Johnson, R.A.; Novembre, J.; Freeland, E.; Conley, D. Public attitudes toward genetic risk scoring in medicine and beyond. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 274, 113796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnaer, T.; Siermann, M.; Borry, P.; Tšuiko, O. Polygenic risk scoring of human embryos: A qualitative study of media coverage. BMC Med. Ethics 2021, 22, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treff, N.R.; Eccles, J.; Marin, D. Preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disease relative risk reduction: Evaluation of genomic index performance in 11,883 adult sibling pairs. Genes 2020, 11, E648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.R.; Kanai, M.; Kamatani, Y.; Okada, Y.; Neale, B.M.; Daly, M.J. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Munoz, G.; Pereira Carmi, S.; Lencz, T. Screening embryos for polygenic conditions and traits: Ethical considerations for an emerging technology. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).