Abstract

Central compartment atopic disease (CCAD) is a distinct phenotype within chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) with a pathophysiology that bridges the gap between allergy and CRSwNP, an association that was previously ambiguous. Understanding this endotype and its link to allergic disease is crucial for improved CCAD management. Using a systematic search and an independent dual-reviewer evaluation and data extraction process, this scoping review examines the clinical features, management options, and treatment outcomes of CCAD. Central compartment (CC) polypoid changes of the MT predominantly correlate with allergic rhinitis, increased septal inflammation, oblique MT orientation, and decreased nasal cavity opacification and Lund–Mackay scores compared to other CRSwNP subtypes. CCAD patients also exhibit higher rates of asthma, allergen sensitization, and hyposmia or anosmia. Surgical outcomes, including revision rate and SNOT-22 improvement, are favorable in CCAD as well. In conclusion, CCAD primarily affects atopic individuals and is managed using endoscopic sinus surgery combined with treating the underlying allergy. Continued research is needed to further refine understanding and develop optimal treatment strategies of this emerging CRS subtype.

1. Introduction

Central compartment atopic disease (CCAD) is a sinonasal inflammatory process with a unique and strong association with inhalant allergy. Recently described as a distinct subtype of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP), CCAD is defined by polypoid changes in the central compartment (CC) of the nasal cavity, including the middle turbinate (MT), the superior turbinate (ST), and the superior nasal septum (SNS) [1,2,3,4]. The inferior turbinate is oftentimes spared from polypoid changes, potentially due to differences in the underlying tissue and embryonic origins as the MT arises from the ethmoid complex, while the inferior turbinate originates separately from the lateral cartilaginous capsule [5].

The CCAD phenotype was first described in 2014 by White et al., who identified an association between isolated MT polypoid edema/polyps and inhalant allergy [6]. This finding was reinforced in a larger study by Hamizan et al. in 2017, which found a strong correlation between MT polypoid changes and positive allergy status [7]. That same year, Brunner et al. found heightened allergen sensitivities and a stronger link to allergic rhinitis (AR) among patients with isolated MT polyps [8]. DelGaudio et al. further defined this CRS variant by coining the term “CCAD” in recognition that the allergic edema can include more of the CC of the nasal cavity, extending to the ST and SNS [3].

Subsequently, it has been hypothesized that CCAD represents a distinct phenotype along the continuum between allergic disease and nasal polyp disease, with a strong allergy association contrasted by its low asthma prevalence [4,9,10]. Unlike AFRS, which has a similar relationship between nasal polyposis, allergy, and asthma, CCAD presents a more confined polyposis limited to the CC of the nasal cavity, likely due to immunoglobulin-E (IgE)-mediated airway inflammation in the CC, where nasal airflow and allergen deposition are the highest [4,5,9].

Despite the increasing recognition of CCAD as a distinct phenotype of CRS with unique pathophysiologic underpinnings, there remains a substantial opportunity for further understanding of this emerging disease phenotype. Current studies have been largely heterogeneous and retrospective, with inconclusive evidence for an association between CRS and allergy [10]. While CCAD is hypothesized to represent a distinct phenotype along the continuum between allergic disease and nasal polyp disease, uncertainties remain on whether CCAD is a more diffuse presentation of AR rather than a distinct phenotype of CRS [11]. Further understanding of CCAD and its association with allergy is critical in guiding treatment and improving patient outcomes. This scoping review aims to identify, explore, and map the current literature investigating CCAD, focusing on its clinical characteristics, management options, and treatment outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.1.1. Participants

A review protocol was created a priori and registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://osf.io/hmr3z accessed on 5 February 2023). This scoping review included all published primary studies investigating CCAD. All participants in any healthcare context were included. Studies that did not investigate CCAD specifically or only mentioned CCAD in passing were excluded. Reviews and non-peer-reviewed studies were also excluded. The concepts examined by this review include the epidemiology, symptoms, clinical workup, radiographic findings, molecular findings, and management of CCAD. These concepts were explored by examining both qualitative and quantitative data as they pertain to the concepts of the review; specific attention was paid to data that allow comparisons across studies and disease processes. All works in the literature investigating CCAD that met the above criteria were included in this scoping review without restriction to any specific population, healthcare setting, or geographic context.

2.1.2. Information Sources

This scoping review included both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs, including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, before-and-after studies, and interrupted time-series studies. In addition, analytical observational studies, including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and analytical cross-sectional studies, were considered for inclusion. This review also considered descriptive observational study designs, including case series, individual case reports, and descriptive cross-sectional studies for inclusion.

Studies published in any language were included, provided an adequate translation was available. Only studies published since 2010 were included to limit irrelevant search results since CCAD was only initially described in 2014 and termed in 2017. This scoping review excluded reviews, text, and opinion papers.

2.1.3. Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate published studies. An initial limited search of PubMed (MEDLINE) was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. The text contained in the titles, abstracts of relevant papers, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a complete search strategy for PubMed. This search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was adapted for each included database. The last search was conducted on 20 December 2022.

Search strategy for PubMed: “Central Compartment Atopic Disease” OR (“CCAD” AND (“Sinus*” OR “Rhin*” OR “Central Compartment” OR “Middle Turbinate*”)) OR (“Rhin*” AND (“Central Compartment” OR “Middle Turbinate*”) AND (Aeroallergen OR Allerg* OR Atop*)) OR (“Nasal Polyposis” AND (“Central Compartment” OR “Middle Turbinate*”) AND (Aeroallergen OR Allerg* OR Atop*)) OR (“Sinus*” AND (“Central Compartment” OR “Middle Turbinate*”) AND (Aeroallergen OR Allerg* OR Atop*)).

2.2. Study Selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (C.D., F.W.) then screened titles and abstracts for assessment against the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. Potentially relevant sources were retrieved, and their full text was screened again by two independent reviewers (C.D., F.W.) to assess the full text of selected citations in detail against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reasons for excluding sources of evidence at the full-text stage that did not meet the inclusion criteria were recorded and reported in the scoping review. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved via consensus with an additional reviewer (C.D., F.W., and E.Y.H.).

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted from papers included in the scoping review by two reviewers (C.D., F.W.) using a data extraction tool developed by the reviewers. The data extracted included details about the study design, aims, participants, concept, context, study methods, and key findings relevant to the review question(s). The draft data extraction tool was modified and revised as necessary while extracting data from each included evidence source. Each study’s level of evidence (LoE) was also evaluated according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence Working Group’s guidance. Any reviewer disagreements were resolved through consensus with an additional reviewer (C.D., F.W., and E.Y.H.). The extracted data were synthesized into a narrative summary and presented in tabular form according to the concepts covered in the review.

3. Results

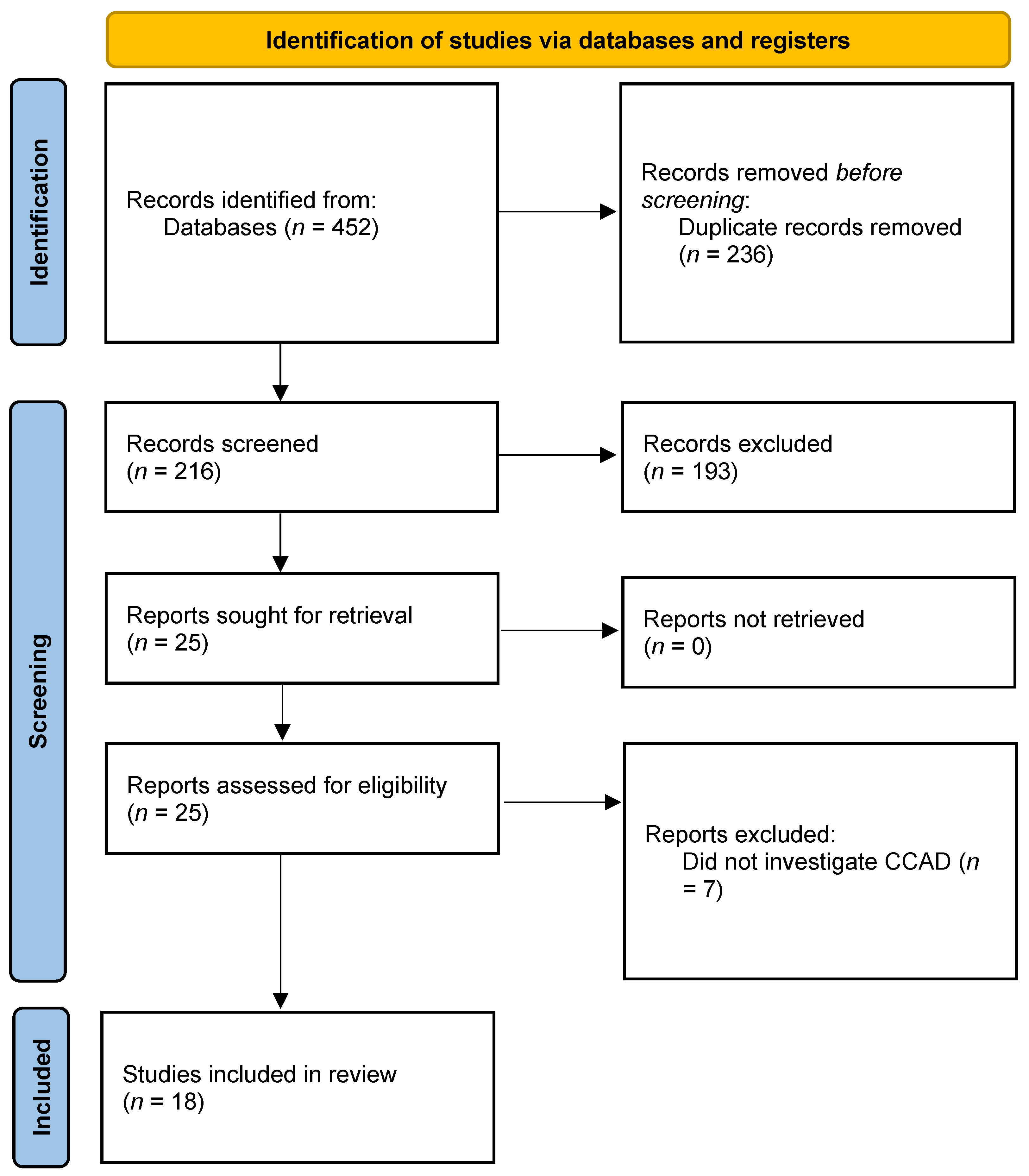

The systematic search yielded 452 results, which contained 216 unique studies after deduplication. Title and abstract screening removed 193 studies based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text evaluation of the remaining 25 studies yielded a final group of 18 for inclusion in this scoping review. The seven studies excluded during the full-text review were removed because they did not mention or specifically separate patients by CCAD or its phenotype. The flow of studies included in this review is summarized in Figure 1. A summary of all abbreviations included in this study is presented in Table 1. Additionally, all of the included studies’ aims, designs, and extracted results are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram illustrating the flow of studies included in this review.

Table 1.

Summary of all abbreviations.

The early studies of what would ultimately be termed CCAD focused on investigating the relationship between CC polypoid degeneration and allergy in patients with CRSwNP. White et al., in 2014, conducted a case series to examine the relationship between isolated MT polyps and inhalant allergy in 25 patients [6]. All 16 patients who underwent allergy testing were found to have positive results for inhalant allergy. The patients were found to be sensitive to both perennial and seasonal allergens. All patients reported symptoms of AR, including nasal congestion, facial pain, sneezing, rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, cough, and itchy eyes. Brunner et al., in 2017, compared the clinical characteristics of polypoid change of the middle turbinate (PCMT) with paranasal sinus polyposis (PSP) [8]. The study found that PCMT is more commonly associated with AR than PSP (83% vs. 34%; p = 0.001), while PSP is more commonly associated with CRS (100% vs. 10%; p = 0.0001). There was no difference in asthma incidence between PCMT and PSP, but higher NOSE scores were found in the PSP group. LM scores were also higher in PSP vs. PCMT. The most common aeroallergens found were dust mites, grasses, trees, and weeds.

After these initial studies identifying a potentially distinct endotype of CRSwNP, directed investigations began to focus on identifying its unique clinical characteristics. In the work by DelGaudio et al., published in 2017, in a study of 15 patients with sinonasal symptoms and CC polypoid mucosal changes, the authors first characterized this phenotype as a new variant of CRS, CCAD [3]. All patients were diagnosed with AR, and 14 out of 15 tested positive for environmental allergies. Endoscopy and CT scans showed central polypoid edema with central soft-tissue thickening and peripheral clearing, even in severe disease. Hamizan et al., in 2017, aimed to identify the characteristics of MT edema as a marker of inhalant allergy in 187 patients [7]. The results showed that diffuse and polypoid edema of MT were strongly associated with inhalant allergy, with positive predictive values of 91.7% and 88.9%, respectively. Additionally, multifocal MT edema was used as a cut-off to represent inhalant allergy with a sensitivity of 23.4%, a specificity of 94.7%, a positive predictive value of 85.1%, and a positive likelihood ratio of 4.4. In a cross-sectional study of 112 patients with CRS, Hamizan et al., in 2018, found that centrally limited changes in all of the paranasal sinuses were associated with allergic status (73.53% vs. 53.16%, p = 0.03) and had a high specificity (90.82%) and positive predictive value (73.53%) for predicting atopy, with a diagnostic odds ratio of 4.59 [12].

Meanwhile, in 2019, DelGaudio and colleagues investigated the relationship between CC polypoid changes, allergic status, and endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with AERD [2]. Out of 72 patients included patients, 80.6% had CC polyps/polypoid disease, and 45 out of 48 patients had positive allergy testing. CC endoscopic findings in this cohort were significantly associated with clinical AR. Patients with septal involvement and CC involvement underwent more endoscopic sinus surgeries than those without, and there was a positive association between sinus surgery and MT resection and septal involvement. Patients who had undergone MT resection were noted to have had increased septal disease, which the authors hypothesized illuminated the potential role of the MT as a protective barrier. In a study of 356 patients with CRSwNP by Roland et al. published in 2020, CT scans showed that AERD and CCAD patients had higher levels of septal inflammation and oblique MT orientation than AFRS and CRSwNP NOS (p < 0.05) [13]. Olfactory cleft opacification was also higher in AERD and CCAD compared to AFRS and CRSwNP NOS (p < 0.05). CCAD patients had the lowest levels of nasal cavity opacification and LM scores (p < 0.05).

A study by Marcus et al. in 2020 evaluated the prevalence of allergy and asthma in different CRSwNP subtypes (CCAD, AFRS, AERD, CRSwNP NOS, and CRSwNP/CC, which is CRSwNP plus CC involvement) in 356 patients [4]. Results showed that asthma was highest in AERD (100%) and CRSwNP NOS (37.1%) and lowest in AFRS (19.0%) and CCAD (17.1%). The prevalence of positive allergy tests was highest in AFRS (100%), CCAD (97.6%), CRSwNP/CC (84.6%), and AERD (82.6%), and lowest in CRSwNP NOS (56.1%). Abdullah et al., in 2020, found that, of 38 patients with CRSwNP, those with allergy (termed CCAD) had higher symptoms of needing to blow their nose, higher LK and LM scores, and 100% had allergies [14]. They also had worse MT edema and polypoidal degeneration than those without allergies.

Warman et al., in 2021, compared the inflammatory features of antrochoanal polyps to diffuse primary CRSwNP (d-CRS) and its subgroups [15]. Results showed that CCAD had higher rates of AR than eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic subgroups. Antrochoanal polyps had a higher occurrence of neutrophilic predominant infiltrates compared to d-CRS. Cyst formation was lower in the CCAD group than the antrochoanal polyp group, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Steehler et al., in 2021, evaluated surgical outcomes across five CRSwNP subtypes [16]. The cohort consisted of 32 patients with different subtypes of CRSwNP, including CCAD, AERD, AFRS, and CRSwNP NOS. They found that the recurrence rate was higher than average in AFRS and lower than average in CCAD; similarly, revision rates for surgery were higher than average in AFRS and CRSwNP NOS but lower in CCAD. The median time to revision for all subtypes was approximately 2 years. The study also found that CRSwNP NOS patients received significantly more antibiotic courses compared to CCAD patients but there was no significant difference in steroid use between subtypes.

Several studies have also investigated the clinical features, histopathologic profiles, and treatment outcomes of CCAD in Asian patients. The study by Lin et al. in 2021 demonstrated higher prevalence of hyposmia or anosmia and higher levels of peripheral eosinophils and basophils as well as higher levels of IL-5 and IL-13 in individuals with CCAD [17]. Shin et al., in 2022, examined the clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with CCAD and lateral-dominant nasal polyps (LDNP) undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery [18]. Results indicated that patients with CCAD had a higher proportion of asthma and AR symptoms, as well as higher eosinophil counts in serum and tissue, compared to those with LDNP. The CCAD group also had greater perioperative blood loss and longer mucociliary clearance time compared to LDNP. Preoperative symptom scores were similar in both groups, although the CCAD group had higher scores in sneezing and hyposmia/dysgeusia subscores. Post-operative improvement was greater in the CCAD group compared to the LDNP group; however, there was no significant difference in SNOT-22 scores three months post-op. Additionally, the CCAD group had worse initial mucociliary clearance but greater improvement after three months compared to the LDNP group. These findings suggest that there are distinct clinical and pathophysiological characteristics between CRSwNP subtypes, which should be considered in the management of patients with CRS. Kong et al., in 2022, found that allergen sensitization was more prevalent in CCAD than in other subtypes of CRS, as well as a higher incidence of asthma [19]. Nie, in 2022, revealed that CCAD had the highest eosinophilic CRS and the lowest scores for LM, TNSS, and SNOT22 compared to CRSwNP/CC and also showed a higher olfactory decline and significant differences in serum IgE levels between atopy and non-atopy CCAD groups [20].

Tripathi et al., in 2022, investigated the allergen sensitization profiles of 515 patients with CRS endotypes and AR [21]. The results showed that CCAD had the highest sensitivity to weeds and dust mites and had greater sensitivity to grasses, weeds, cats, dogs, feathers, and other animals than CRSsNP and AERD. AFRS showed greater sensitivity to most allergens, especially mold, than CCAD. These authors also showed no significant difference in inhalant allergen sensitization between AR and CCAD, except for a higher prevalence of weed allergy in the CCAD group. Meanwhile, Edwards et al., in 2022, also investigated the role of atopy in CCAD by comparing allergen sensitivity in local sinonasal tissue, skin, and serum in CCAD [22]. Ninety-three percent (14/15) of patients were sensitive to at least one allergen in all three sites. Positive correlations were found between local sinonasal tissue and systemic serum (all p < 0.05), but weaker correlations were found between local sinonasal tissue and skin serum-specific IgE (r = 0.353, p < 0.05).

Finally, Lee et al., in 2022, studied 82 pediatric patients diagnosed with CRS. The radiologic phenotype of CCAD was found to be a strong predictor of allergen sensitization (OR: 4.066) and asthma (OR: 4.923) [23]. The prevalence of CCAD phenotype was higher in allergen-sensitized vs. non-sensitized patients (24.5% vs. 7.4%). Radiologic findings of CCAD were the best predictors for allergen sensitization and asthma, followed by peripheral blood eosinophil levels greater than 5%.

Table 2.

Summary of all included studies’ aims, design, and extracted results.

Table 2.

Summary of all included studies’ aims, design, and extracted results.

| Study | Aim of Study | Study Design and Level of Evidence | Population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White, 2014 [6] | Investigate the association between isolated MT polyps and inhalant allergy | Case series Level 4 | 25 patients with isolated MT polyps |

|

| Brunner, 2017 [8] | Compare clinical characteristics of polypoid change of the MT (PCMT) with paranasal sinus polyposis (PSP) | Case series Level 4 | 593 patients: 23 (3.9%) with PCMT and 44 (7.4%) with PSP |

|

| DelGaudio, 2017 [3] | Describe a newly recognized variant of CRS, termed CCAD | Case series Level 4 | 15 patients with sinonasal symptoms and CC polypoid mucosal changes |

|

| Hamizan, 2017 [7] | Determine the characteristics of MT edema as a marker of inhalant allergy | Cross-sectional Level 4 | 187 patients |

|

| Hamizan, 2018 [12] | Identify radiologic patterns in CRS to predict allergic etiology | Cross-sectional Level 4 | 112 patients with CRS |

|

| DelGaudio, 2019 [2] | Investigate the role of allergy and surgery in CC involvement in AERD | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 72 patients with AERD: 59 (80.6%) had CC polyps/polypoid disease, with 53 bilateral and 6 unilateral |

|

| Abdullah, 2020 [14] | Define the clinical and radiological characteristics of the allergic phenotype of CRSwNP | Cross-sectional Level 4 | 38 patients with CRSwNP: 19 with allergy and 19 without allergy |

|

| Marcus, 2020 [4] | Determine the prevalence of allergy and asthma in CCAD compared with other CRSwNP subtypes | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 356 patients with CRSwNP: 37.1% with CRSwNP NOS, 24.2% with AERD, 23.6% with AFRS, 11.5% with CCAD, and 3.7% with CRSwNP/CC |

|

| Roland, 2020 [13] | Evaluate CT findings associated with each CRSwNP phenotype | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 356 patients: 23% with AFRS 28% with AERD 12% with CCAD 37% with CRSwNP NOS |

|

| Lin, 2021 [17] | Investigate the clinical features and cytokine profiles of CCAD in East Asian patients. | Cross-sectional Level 4 | 95 patients: 16 with CCAD and 51 with other CRS subtypes |

|

| Steehler, 2021 [16] | Evaluate surgical outcomes in CRSwNP subtypes | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 132 patients: 38 with CCAD, 20 with AERD, 37 with AFRS, 37 with CRSwNP NOS |

|

| Warman, 2021 [15] | Compare the inflammatory features of antrochoanal polyps (ACP) to diffuse primary CRSwNP (d-CRS) and its subgroups | Case series Level 4 | 96 patients: 40 (41.6%) with ACP, 36 (37.5%) with d-CRS, and 20 (20.8%) with control (patients undergoing turbinate reduction surgery due to nasal obstructions) |

|

| Edwards, 2022 [22] | Compare allergen sensitivity of local sinonasal tissue to that of skin and serum in patients with CCAD | Case series Level 4 | 15 participants with CCAD |

|

| Kong, 2022 [19] | Identify clinical presentations and cellular endotyping diagnosis of Chinese CCAD using artificial intelligence | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 79 Patients: 14 with CCAD, 32 with eosinophilic CRSwNP (ENP), and 26 with non-eosinophilic CRSwNP (NENP) |

|

| Lee, 2022 [23] | Investigate the ability of radiologic studies to predict CCAD in pediatric patients | Retrospective Cohort Level 3 | 82 pediatric patients diagnosed with CRS: 55/82 (67.1%) had aeroallergen sensitization, and 31/164 (18.9%) sides of sinuses had the radiologic CCAD phenotype |

|

| Nie, 2022 [20] | Describe the clinical manifestations of CCAD and compare to CRSwNP/CC involvement and CRSwNP NOS | Case series Level 4 | 116 patients: 39 with CCAD, 38 with CRSwNP/CC, and 39 with CRSwNP NOS |

|

| Shih, 2022 [18] | Determine the clinical presentations, risk factors, and surgical outcomes of CCAD in the Asian population | Case control Level 4 | 442 patients with CRSwNP: 51 with CCAD and 391 with lateral-dominant nasal polyp (LDNP) |

|

| Tripathi, 2022 [21] | Identify allergens associated with CRS endotypes and any relationships between their allergen sensitivity profiles. | Cross sectional Level 4 | 515 patients: 341 with CRS, 174 with AR. Of CRS patients: CRSwNP = 182, CRSsNP = 159. Of CRSwNP: AERD = 15, AFRS = 18, CCAD = 24, CRSwNP NOS = 125 |

|

4. Discussion

Since its formal description, an increasing body of evidence has supported the diagnosis of CCAD, a condition characterized by polypoid changes in the central compartment and a strong association with inhalant allergy but a variable prevalence of asthma. In this scoping review, we identify and synthesize the existing literature investigating CCAD, focusing on its clinical characteristics, management, and treatment outcomes. The goal of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of CCAD and its management options, which will help guide future research and inform clinical practice.

4.1. Clinical Characteristics

4.1.1. Patient Characteristics

Clinically, patients with CCAD typically present with congestion, sneezing, nasal itching, and a history of atopy [8,14]. In addition to local rhinitis and atopic symptoms, patients often have a history of systemic atopy, like asthma and dermatitis [7,8,23]. However, patients with CCAD have been shown to have variability in the presentation of their symptoms. While some authors have found minimal changes in the sense of smell, others have found that patients have had higher rates of hyposmia and anosmia despite having similar levels of nasal obstruction [17,18]. Additionally, although asthma is a common association with CCAD, there are highly variable rates ranging from 9.8% to 33.3% [18,20].

4.1.2. Nasal Endoscopy

Polypoid edema of the middle turbinate is one of the hallmark features of CCAD on nasal endoscopy. In mild cases, the polypoid edema is isolated to the middle turbinate, but in more severe cases, the polypoid edema extends to the posterior superior septum and superior turbinate [3]. Beyond more localized polypoid changes, patients with CCAD were found to have lower Lund–Kennedy endoscopic scores than patients with other CRS forms [19]. Notably, CCAD is characterized by normal sinus mucosa with the absence of thick eosinophilic mucin, which helps differentiate it from other endotypes of CRS [8,19]. This unique pattern is likely due to the airflow dynamics of the nasal cavity, which is highest centrally, leading to increased deposition of inhaled allergens on the head of the MT [1]. Additionally, this difference may have embryologic origins as the MT develops from the ethmoid bone, while the inferior turbinate arises from the lateral cartilaginous capsule and is more vascular than the MT [5].

4.1.3. Radiologic Imaging

Imaging is also a vital component in the workup of CCAD as it can help differentiate between the CRS subtypes [13]. Studies have reported unique associations between centrally limited radiological disease and inhalant allergy sensitivity [12,24]. Characteristic CT imaging demonstrates central thickening of the middle turbinate, superior turbinate, and septum with clear peripheral sinus mucosa, termed the black halo sign [1,12]. Notably, several studies expand this definition of CCAD by considering both central disease with normal sinus mucosa and disease with floor and medial wall mucosal involvement as CCAD, while diffuse disease is defined by roof or lateral wall involvement [3,12,14,17,19,23]. While it would have been valuable to further compare CCAD with and without sinus involvement, none of the studies distinguished these two groups in their results. The current literature justifies this grouping by postulating that rather than demonstrating a continuum of disease connecting CCAD to more diffuse types of CRSwNP, the presence or absence of sinus disease in CCAD results from simple ostia obstruction via medial-to-lateral disease progression or direct extension of polyps from the MT encroaching on the sinus outflow tracts. In the most severe instances, near-complete sinus opacification may be observed, with sinus involvement progressing in a medial-to-lateral direction; however, the post-obstructive nature of this sinus disease is confirmed by the presence of normal sinus mucosa within these sinuses following surgical intervention [3,12]. This pattern distinguishes CCAD from the other endotypes of CRS, which have more diffuse disease and less central compartment involvement.

Radiologic findings on CT have been found to be milder, with lower Lund–Mackay scores when compared to other forms of CRS [19]. Furthermore, imaging may help differentiate CCAD phenotypes in pediatric patients to establish an early diagnosis and provide proper long-term treatment [23]. However, CT imaging does have its limitations, and imaging alone cannot diagnose CCAD. In advanced disease, CT scans may show completely opacified sinuses that are indistinguishable from other forms of CRS [20]. These cases require further clinical examination including clinical and allergic history with nasal endoscopy to visualize the location of the polyposis to better differentiate between variants of CRSwNP.

4.1.4. Allergy Testing

A defining feature of CCAD is its association with atopic diseases. The majority of studies in this review reported positive allergy rates between 93.3% to 100% and recommended allergy testing in patients suspected of having CCAD [4,6,14,22]. Conversely, two studies found lower allergy rates of 31.3% and 37.1%; however, these results were specific to the Southern Chinese and Taiwanese population, respectively [17,20]. It is possible there are different endotypes and phenotypes for CCAD in different populations, similar to other forms of CRSwNP, but further research is needed to characterize this. Given the chronic nature of CCAD, it is hypothesized that persistent allergen exposure, resulting in chronic inflammation, produces the CCAD’s phenotype. Consequently, patients are most likely sensitive to a single perennial allergen, such as dust mites, rather than seasonal allergens like pollen [12,17].

Beyond positive environmental allergy testing, CCAD has also been shown to be associated with asthma, AERD, and AR. In one study, 80.6% of patients with AERD were found to have signs of CCAD on endoscopic exam, and among this group, 100% had clinical AR [2,18]. Given the role of atopy in the pathophysiology of CCAD, it is important to identify allergen sensitization through appropriate testing. Skin and in vitro serum allergen-specific IgE testing are the primary methods for determining IgE hypersensitivity. However, systemic allergy testing may not always reflect nasal pathophysiology, and there can sometimes be discordance between skin and serum-specific IgE testing, which can lead to misdiagnosis [22]. Additionally, local allergic rhinitis can be present in a subset of patients with negative systemic allergy testing [22,25]. A review by Hamizan et al. investigated the difference between systemic and local nasal allergen reactivity in rhinitis patients. They found local reactivity in 26.5% of patients previously classified as non-allergic, indicating the utility of nasal allergen provocation tests to detect local nasal allergen-specific IgE [26].

4.1.5. Histology and Molecular Findings

Cellular and molecular analysis is increasingly helpful both in defining and treating various CRS endotypes. In this review, we demonstrate that individuals with CCAD often have local tissue eosinophilia without eosinophil aggregates, degranulation, or Charcot–Leyden crystals as well as elevated total and specific IgE [1]. Patients with CCAD may, however, be without systemic eosinophilia. Shih et al. found that patients with CCAD had higher serum IgE levels and higher eosinophil counts in serum and local nasal tissue compared to patients with lateral-dominant nasal polyps [18]. Later studies found similar results with CCAD patients having higher blood eosinophil levels than CRSwNP without central compartment involvement and even higher levels in the local tissue of the central compartment compared to the serum [20,22,23]. These histopathologic profiles have important implications for CCAD treatments and outcomes. Eosinophilia has been linked to worse CRS overall and olfactory function as well as higher polyp recurrence, while neutrophilia is associated with corticosteroid sensitivity, and both may result in worse surgical outcomes due to excessive perioperative blood loss mediated by severe local inflammation [18,19]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that histology and molecular profiles alone are insufficient to diagnose CCAD, as many cases have similar profiles to eosinophilic CRS [20]. Further research to better characterize the endotype of CCAD is needed.

4.2. Management and Treatment Outcomes

Overall, only Steehler et al. in 2021 and Shin et al. in 2022 specifically investigated treatment outcomes in patients with CCAD [16,18]. Outside of these two studies, treatment for CCAD has been guided by the treatment of CRSwNP and allergic rhinitis. For CRSwNP, the initial treatment is intranasal and oral corticosteroids [22]. This also appears to be an effective initial treatment for CCAD [14,19]. However, in cases with extensive polypoid changes, topical corticosteroid sprays alone are unlikely to resolve the remodeling that has already occurred, necessitating surgical intervention to remove polyps, relieve any secondary obstruction, and facilitate the delivery of topical therapeutics [18]. Endoscopic sinus surgery has been shown to provide rapid relief of clinical symptoms, particularly rhinologic symptoms. In patients with isolated CCAD, conservative surgical management of the affected areas has a lower incidence of polyp recurrence and revision surgery than other subtypes [9,16,18]. Surgical management of the middle turbinate, one of the primary locations of polypoid inflammation, is not clear. Delgaudio et al. found complete resection of the middle turbinate led to recurrence of polyps in the septal mucosa [2]. Studies comparing outcomes of complete, partial, and no MT resection in CCAD patients are needed.

Notably, however, Western subjects with CCAD displayed a notably lower revision rate than expected, while the Asian cohort showed no such difference and had a revision rate about five times higher [16,18]. This variance might arise from racial, environmental, and post-operative care differences, such as the prevalent use of post-operative intranasal steroids in the West versus saline irrigation in Asia [18].

This disparity in outcomes also highlights the importance of managing the underlying inhalant allergy [10,14]. It is not uncommon for patients to remain symptomatic post-operatively, developing progressive polypoid changes on the residual turbinates and septum with a normal sinus cavity [2]. Therefore, the management of CCAD commonly involves a multifaceted approach that includes ESS, post-operative topical steroid rinses, and treatment of underlying allergies. For patients with indolent allergic processes, surgical intervention may be the initial step in alleviating nasal obstruction and other symptoms, while allergen exposure and atopic sequelae are addressed following surgery [3,24]. However, if the patient’s allergic symptoms are active and more severe, immunotherapy should be considered first and surgery delayed until the airway mucosa has stabilized. In cases where immunotherapy is not tolerated, or for those with hyper-IgE states or persistent allergy that has not responded to immunotherapy or pharmacotherapy, anti-IgE medications such as omalizumab may be considered [14]. Finally, it is important for clinicians to inquire about olfactory function, perform pre- and post-operative olfactory testing, and counsel patients on olfaction-related outcomes, as CCAD can significantly affect olfactory function [17].

Overall, it is important to note that the current level of evidence regarding CCAD treatment is generally low. The current lack of prospective studies that can guide treatment decision making leaves clinicians with limited guidance on how to manage patients with CCAD. Consequently, there is a pressing need for more well-designed prospective studies to investigate the available treatments and to identify the optimal approach to management.

4.3. Specific Populations

Given the importance of atopy in the pathogenesis of CCAD, regional and population-based differences in atopic phenotypes can alter treatment pathways and outcomes. While the bulk of CCAD research has occurred in the southeastern United States and Australia, several recent studies have focused on characterizing the CCAD endotype in East Asian populations. For example, in Western countries, CRSwNP is primarily characterized by eosinophilic type 2 inflammation, while in East Asian countries, there is a mix of type 1, type 2, and type 17 inflammation [19,20,27]. Variations in histopathology may have tangible effects on patient symptoms and outcomes, given that eosinophilia in CRS has been correlated with hyposmia/anosmia and ethmoid opacification on CT scans [17].

One significant difference between Western and Asian populations is the variation in allergy and asthma. Previous studies based on Western populations strongly linked CCAD to allergy; however, studies of Asian populations found much lower incidences of comorbid allergy, 31–37.1% vs. 73–100% in Western populations [3,4,17,18,20]. However, similar perennial allergens like dust mites were the most common allergens identified in Asian countries [17]. As opposed to allergies, the incidence of asthma was higher in Asian patients with CCAD (33.3%) than in other CRS subtypes (10.3–34.2%) and marginally higher compared to Western populations (11.6%) [4,18,20].

Regarding histologic testing, higher eosinophil counts were found in serum and local nasal tissue in patients with CCAD, but no differences were found in local sinonasal IgE levels compared to other CRSwNP subtypes [17,18,19]. These findings indicate that despite differences in allergy and asthma incidence, similar cellular mechanisms—namely type 2-based inflammation—underpin CCAD pathogenesis in Asian and Western populations.

While management strategies have not been fully elucidated yet, existing histopathologic, radiographic, and endoscopic data suggest CCAD is a distinct phenotype of CRSwNP. We hypothesize that CCAD ultimately results from progressive inflammation of the nasal cavity along with allergic rhinitis which eventually increases in severity and results in nasal polyp formation and potentially CRS.

5. Conclusions

CCAD is a subtype of CRSwNP that typically presents in younger individuals with a history of atopy, including asthma and dermatitis, and is often accompanied by local rhinitis and atopic symptoms like itchiness, sneezing, and conjunctival symptoms. The studies included in this scoping review emphasize the importance of using nasal endoscopy, CT imaging, and histology to properly diagnose CCAD, a relatively new phenotype of CRSwNP. This review also explores the current treatment approaches for CCAD, which entail a combination of endoscopic sinus surgery to remove the affected tissue, medical management with topical intranasal steroids, and treating the underlying allergic condition with immunotherapy. The proper diagnosis and treatment of CCAD are intertwined as the disease’s distinctive pathophysiology guides patient counseling, surgical management, and post-operative care.

There is, however, much to learn regarding CCAD. Considering this review includes a relatively low level of evidence, future balanced, prospective studies are required to better delineate and understand environmental and host causes for this CRS subtype. This will be especially important regarding improving the understanding of the role of surgical management of disease, given reports that surgical removal of involved anatomical subsites may promote involvement and subsequent disease progression in remaining subsites. Furthermore, given the molecular underpinnings of this disease, it will be critical to further evaluate the role of management of allergic disease or potentially even consider the role of targeted biologic therapy for this entity. While increasing interest in CCAD is encouraging, there is still much work to be done in terms of conducting well-designed prospective studies to better understand the optimal management of this CRS subtype, particularly regarding surgical interventions and the role of allergic disease management and biologic therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D., N.R.R. and O.G.A.; methodology, C.D.; data curation, C.D., F.W. and E.Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D., F.W. and E.Y.H.; writing—review and editing, C.D., N.R.R., M.T. and O.G.A.; visualization, C.D.; supervision, N.R.R., M.T. and O.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grayson, J.W.; Cavada, M.; Harvey, R.J. Clinically relevant phenotypes in chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 48, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DelGaudio, J.M.; Levy, J.M.; Wise, S.K. Central compartment involvement in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease: The role of allergy and previous sinus surgery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DelGaudio, J.M.; Loftus, P.A.; Hamizan, A.W.; Harvey, R.J.; Wise, S.K. Central compartment atopic disease. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2017, 31, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, S.; Schertzer, J.; Roland, L.T.; Wise, S.K.; Levy, J.M.; DelGaudio, J.M. Central compartment atopic disease: Prevalence of allergy and asthma compared with other subtypes of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 10, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Ong, Y.K.; Wang, Y. Precision Medicine in Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Where Does Allergy Fit In? Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 268, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.J.; Rotella, M.R.; DelGaudio, J.M. Polypoid changes of the middle turbinate as an indicator of atopic disease. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamizan, A.W.; Christensen, J.M.; Ebenzer, J.; Oakley, G.; Tattersall, J.; Sacks, R.; Harvey, R.J. Middle turbinate edema as a diagnostic marker of inhalant allergy. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.P.; Jawad, B.A.; McCoul, E.D. Polypoid Change of the Middle Turbinate and Paranasal Sinus Polyposis Are Distinct Entities. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 157, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGaudio, J.M. Central compartment atopic disease: The missing link in the allergy and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps saga. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 10, 1191–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, S.; Roland, L.T.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Wise, S.K. The relationship between allergy and chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.K. In Reply: Central compartment atopic disease: The missing link in the allergy and CRSwNP saga. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 10, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamizan, A.W.; Loftus, P.A.; Alvarado, R.; Ho, J.; Kalish, L.; Sacks, R.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Harvey, R.J. Allergic phenotype of chronic rhinosinusitis based on radiologic pattern of disease. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, L.T.; Marcus, S.; Schertzer, J.S.; Wise, S.K.; Levy, J.M.; DelGaudio, J.M. Computed Tomography Findings Can Help Identify Different Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyp Phenotypes. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 34, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, B.; Vengathajalam, S.; Md Daud, M.K.; Wan Mohammad, Z.; Hamizan, A.; Husain, S. The Clinical and Radiological Characterizations of the Allergic Phenotype of Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. J. Asthma Allergy 2020, 13, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warman, M.; Kamar Matias, A.; Yosepovich, A.; Halperin, D.; Cohen, O. Inflammatory Profile of Antrochoanal Polyps in the Caucasian Population—A Histologic Study. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2021, 35, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steehler, A.J.; Vuncannon, J.R.; Wise, S.K.; DelGaudio, J.M. Central compartment atopic disease: Outcomes compared with other subtypes of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Lin, C.F.; Liao, C.K.; Chiang, B.L.; Yeh, T.H. Clinical characteristics and cytokine profiles of central-compartment-type chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, L.C.; Hsieh, B.H.; Ma, J.H.; Huang, S.S.; Tsou, Y.A.; Lin, C.D.; Huang, K.H.; Tai, C.J. A comparison of central compartment atopic disease and lateral dominant nasal polyps. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022, 12, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, W.; Zheng, R.; Deng, H.; Yuan, T.; Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Chinese Central Compartment Atopic Disease: The Clinical Characteristics and Cellular Endotypes Based on Whole-Slide Imaging. J. Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Xu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Lai, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, F. Clinical characteristics of central compartment atopic disease in Southern China. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022, 13, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.H.; Ungerer, H.N.; Rullan-Oliver, B.; Patel, T.; Sweis, A.M.; Maina, I.W.; Kohanski, M.A.; Palmer, J.N.; Adappa, N.D.; Bosso, J.V. Similarities between allergen sensitivity patterns of central compartment atopic disease and allergic rhinitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022, 12, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.S.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Levy, J.M.; Wise, S.K. A Prospective Analysis of Systemic and Local Aeroallergen Sensitivity in Central Compartment Atopic Disease. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2022, 167, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, C.H.; Je, B.K.; Oh, S. Predictive Value of Radiologic Central Compartment Atopic Disease for Identifying Allergy and Asthma in Pediatric Patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022, 101, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helman, S.N.; Barrow, E.; Edwards, T.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Levy, J.M.; Wise, S.K. The Role of Allergic Rhinitis in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2020, 40, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, S.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Roland, L.T.; Wise, S.K. Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Does Allergy Play a Role? Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamizan, A.W.; Rimmer, J.; Alvarado, R.; Sewell, W.A.; Kalish, L.; Sacks, R.; Harvey, R.J. Positive allergen reaction in allergic and nonallergic rhinitis: A systematic review. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Bo, M.; Holtappels, G.; Zheng, M.; Lou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Bachert, C. Diversity of T(H) cytokine profiles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A multicenter study in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).