Abstract

Automatically generated chains-of-thought (gCoTs) have become common as large language models adopt deliberative behaviors. Prior work emphasizes fidelity to internal processes, leaving explanatory properties underexplored. Our central hypothesis is that these traces, produced by highly capable reasoning models, are not arbitrary by-products of decoding but exhibit stable and practically valuable textual properties beyond answer fidelity. We apply a multidimensional text-evaluation framework that quantifies four axes—structural coherence, logical–factual consistency, linguistic clarity, and coverage/informativeness—that are standard dimensions for assessing textual quality, and use it to evaluate five reasoning models on the GSM8K arithmetic word-problem benchmark (~1.3 k–1.4 k items) with reproducible, normalized metrics. Logical verification shows near-ceiling self-consistency, measured by the Aggregate Consistency Score (ACS ≈ 0.95–1.00), and high final-answer entailment, measured by Final Answer Soundness (FAS0 ≈ 0.85–1.00); when sound, justifications are compact, with Justification Set Size (JSS ≈ 0.51–0.57) and moderate redundancy, measured by the Redundant Constraint Ratio (RCR ≈ 0.62–0.70). Results also show consistent coherence and clarity; from gCoT to answer implication is stricter than from question to gCoT support, indicating chains anchored to the prompt. We find no systematic trade-off between clarity and informativeness (within-model slopes ≈ 0). In addition to these automatic and logic-based metrics, we include an exploratory expert rating of a subset (four raters; 50 items × five models) to contextualize model differences; these human judgments are not intended to support dataset-wide generalization. Overall, gCoTs display explanatory value beyond fidelity, primarily supported by the automated and logic-based analyses, motivating hybrid evaluation (automatic + exploratory human) to map convergence/divergence zones for user-facing applications.

1. Introduction

The term Chain-of-Thought (CoT) encompasses a broad range of techniques in large language models (LLMs), traditionally rooted in prompting strategies that guide models to generate intermediate reasoning steps before arriving at final answers. This approach has become pivotal for enhancing reasoning capabilities, enabling the decomposition of complex tasks into sequential subtasks and often yielding 20–30 percentage-point gains on benchmarks such as GSM8K and BIG-Bench Hard [1]. While traditional CoT relies on handcrafted prompts or demonstrations, recent advancements have led to automatically generated CoT traces (gCoT), which emerge as models evolve toward more deliberative behaviors without explicit user intervention. This shift improves transparency but exposes persistent weaknesses: generated explanations may diverge from the model’s true computations, introducing spurious correlations or misleading rationales [2,3]. Moreover, reliance on handcrafted demonstrations limits scalability and generalization, motivating automated techniques such as zero-shot prompting (“Let’s think step by step”), diversity-based sampling, and active learning [4,5,6].

Prior research on CoT can be grouped into three complementary strands. First, applications and interpretability studies show the utility of CoT in domains such as healthcare, education, and code analysis, integrating retrieval systems or domain-specific agents; interpretability efforts probe internal mechanisms via neuron ablations, causal analyses, and multimodal extensions [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Second, generation and prompting techniques investigate structured demonstrations, zero-/few-shot protocols, and automated strategies including evolutionary search, rationale distillation, and federated prompting [4,13,14]. These advances reduce annotation costs and improve robustness, yet they remain sensitive to exemplar selection, data quality, and noise. Third, evaluation and metrics encompass fidelity assessments, performance benchmarks, and theoretical analyses. Existing frameworks measure alignment with internal processes [2,3,15], task accuracy [16,17,18,19], or vulnerability to noisy reasoning [20], but they tend to isolate dimensions rather than provide holistic characterization, and they rarely test chain-to-answer entailment directly.

Despite these advances, automatically generated CoT traces remain underexplored as standalone explanatory artifacts. Current evaluations privilege fidelity—i.e., whether verbalized steps reflect hidden model computations—while neglecting their potential explanatory value for users, independent of internal validity. This gap limits objective benchmarking and hampers deployment in user-centric applications where clarity, informativeness, and reliability matter as much as alignment with internal mechanisms.

This work introduces a multidimensional evaluation framework to assess gCoT traces along four dimensions: structural coherence, logical/factual consistency, linguistic clarity, and coverage/informativeness. These standard text-evaluation dimensions jointly capture discourse structure, semantic alignment with the problem and answer, surface readability, and the amount of task-relevant content that is verbalized, and they allow us to systematically assess the practical usefulness of gCoTs in terms of both strengths and limitations. We elicit gCoT responses from contemporary LLMs and reasoning models on the GSM8K dataset and compute reproducible, normalized indicators from both evaluation channels. Multiple gCoT generators are used solely to increase output diversity. We do not pursue in-depth cross-model rankings; instead, we verify the presence, magnitude, and stability of structural and linguistic properties. Our guiding question is: How can auto-generated CoT traces be characterized in a multidimensional way to quantify properties beyond fidelity? We test the following hypothesis:

H1.

Auto-generated chains-of-thought produced by highly capable reasoning models are not arbitrary by-products of decoding. When viewed as text, they exhibit stable and quantifiable properties beyond answer fidelity—specifically along coherence, logical/factual consistency, linguistic clarity, and coverage/informativeness—which can be empirically measured and compared across models, providing a basis for future applications aimed at reducing user uncertainty about model outputs.

Owing to the heterogeneous use of “Chain-of-Thought (CoT)” in recent literature, we first clarify the terminology adopted in this paper and then present our empirical contributions: (i) a reproducible methodology for numerical profiling of CoT traces, including a direct logical verification layer; (ii) empirical evidence of explanatory utility beyond fidelity; and (iii) a benchmarking tool and policy hooks to advance interpretable, user-facing deployment (e.g., verification/reranking with FAS0 and compression with JSS/RCR).

The primary contribution of this article is to experimentally demonstrate that auto-generated chains-of-thought (gCoTs) produced by highly capable reasoning models exhibit stable and measurable textual properties. This finding expands the prevailing fidelity-centric perspective and shows that gCoTs can be characterized as structured textual artifacts rather than incidental by-products of decoding. In doing so, our results open the door to deeper investigations into how these properties may be leveraged in explainable AI settings. Finally, the article provides a unified evaluation framework that integrates text-based metrics, expert human judgments, and logic-based verification, enabling systematic characterization.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the literature review; Section 3 presents the methodology, including CoT elicitation protocols, metric computations, and task selection; Section 4 describes empirical results from evaluations; and Section 5 discusses implications for model transparency and deployment and concludes with limitations and future research avenues.

2. Background and Related Work

Although chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting has recently emerged as a central technique in LLM reasoning, its study remains fragmented across domains, generation strategies, and evaluation protocols. Existing works provide valuable advances in applications, prompting methods, and interpretability, yet they also highlight instability, bias, and limited explanatory validity of auto-generated CoT traces. To contextualize our contribution, this section reviews prior research along three dimensions: (i) applications and interpretability, (ii) techniques for generation and prompting, and (iii) evaluation and metrics.

2.1. Applications and Interpretability of CoT

To support our multidimensional evaluation of chains of thought, we reviewed evidence on the practical utility and interpretability of CoT, emphasizing the limitations such an evaluation must capture. In applied domains, CoT proves effective but remains conditioned by the use of auxiliary tools (chunking, RAG, templates) and by noisy or synthetic data: for instance, in the clinical setting, the combination of GPT-4 + RAG + encoders enables correction and detection, though it inherits segmentation and synthesis biases [21,22]; in moderation, post-hoc explanations fail to safeguard against noise [23]; in education, alignment with human evaluators entails high computational cost and risk of overfitting to scoring criteria [7,24]; and in social media, decomposition and multi-prompts improve F1 while undermining scalability [25,26]. Specialized domains show local gains with limited validation or small samples, alongside generalization constraints due to template dependence [8,9,10,11,27,28,29,30].

In parallel, interpretability evidence suggests that the chain does not equate to the internal reasoning process: ablations identify arithmetic-sensitive neurons in Llama2 but fall short of a full explanation, leaving attention mechanisms underexplored [12]; theoretical work models intermediate steps as computational resources, extending capacities (from TC0 to P) without conclusive empirical transfer [31]; and in vision-language tasks, LoRA-based fusion localizes cues (e.g., head, hands) but yields static, acausal explanations [32].

In this context, the utility of CoT remains conditional (templates, cost, noise) and mechanistic gaps persist, reinforcing the need for a multidimensional evaluation such as the one we propose.

2.2. Techniques for Generation and Use of CoT

In this review we distinguish four axes directly related to the generation of CoT: (1) automatic generation for inference, (2) generation of CoT for training, (3) format control and alignment, and (4) tool/modality coupling for robustness. This organization allows us to separate orchestration effects (templates, retrieval, perception) from the intrinsic properties of the chain, as required by our multidimensional evaluation.

- 1.

- Automatic generation of CoT for inference

Automation seeks to seed the prompt with demonstrations (question + chain + answer) systematically in order to produce CoT at scale and under experimental control. Hybrid auto-annotation, NumDecoders, and dialogue agents opened the way for scalable trace production [26,33,34]; efficiency improves with evolutionary search and cost-sensitive sampling [13,35,36]. Synthetic and adaptive prompting, policy-gradient optimization, and Gibbs sampling optimize demonstration selection [4,5,6,37]; refinements such as attention-based strategies, curricula, and hybrid templates standardize form without fully stabilizing traces [14,23,38,39,40,41]. The scope is expanded through retrieval-augmented CoT and rationale distillation [40,41,42,43,44,45], as well as structured dataset design and regulated/federated frameworks [46,47,48]. Stability interventions reduce variance but leave residual fragility [49,50,51,52,53]. Domain-specific pipelines, adaptive clustering, saliency-based selection, and preference optimization illustrate fine-tuning and control at the input level [54,55,56,57], while task-specific adaptations show transfer to clinical and symbolic settings at non-trivial cost [58,59,60].

- 2.

- Generation of CoT for training (SFT, distillation, RL)

The same mechanisms are used to create training data and shape how the model learns to reason: rationale distillation and structured dataset design provide direct signals for SFT [44,45,46]; federated frameworks and legal RAG constrain availability and introduce biases [47,48]; saliency-based and preference-optimized selection are applied to ensure quality and diversity [55,56,57]; and structure-oriented methods influence the learned form of the chain [49,51,60]. This line reduces annotation costs and standardizes signals but may perpetuate dependencies on templates and annotation if not carefully controlled.

- 3.

- Format control and alignment

Structured prompting regulates how the chain is produced to meet behavioral constraints. Multi-step protocols mitigate jailbreaks [61,62], and few-shot prompting achieves SOTA performance (e.g., PaLM 540 B on GSM8K) while retaining sensitivity to exemplars [1]. Specialized frameworks improve local alignment but inherit scaffold biases [63,64,65,66,67]. Broader applications—including requirements engineering, structured reasoning, human factors, operating systems, and clinical reasoning—show applicability under curated contexts [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. Efficiency-oriented methods (Concise CoT, Scale-CoT, pruning) compress chains with possible loss of explanatory signal [77,78,79], while concept- or task-oriented approaches (CGCoT, Chain-of-X, CotNER, Time-CoT, interactive CoT, Pipeline-CoT) expand interfaces without removing template/exemplar dependence [80,81,82,83,84,85].

- 4.

- Tool and modality coupling for robustness

Integrating CoT with external tools and vision encoders seeks to increase robustness, although credit may shift to perception or retrieval. Coupled designs appear across agents and training schemes [4,5,49,50,78,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96]; systems such as ChatCoT, Visual CoT, LangChain agents, MultiTool-CoT, Graph CoT, DCoT, and scene-graph prompting demonstrate breadth but also cost and noise sensitivity [5,49,86,87,88,89,90,91,93,94]. Domain-specific tasks—metaphor generation, science QA, fake news detection, demographic inference, and knowledge-graph reasoning—extend testing but reveal fragility under domain shift [50,92,95,96,97,98]. Designs that integrate recognition with inference, such as DDCoT, reduce hallucination yet leave deployment cost and transfer as open challenges [99].

2.3. Evaluation and Metrics for CoT Outputs

Evaluation research seeks to answer how to measure the reliability, utility, and robustness of CoT traces, going beyond mere task accuracy to examine what the chains explain and how they fail. A first line of work focuses on fidelity—the degree to which CoT aligns with internal mechanisms—using model–mechanism comparisons and perturbation tests to probe causal correspondence [2,12,21,33]. Systems like CoTEVer integrate prompting, retrieval, and human Likert-scale judgments to classify error types, although annotation scalability remains a central bottleneck [15]. Bias-induced divergences further warn that plausible justifications can be misleading: under controlled bias, GPT-3.5 and Claude show a ~36% accuracy drop on BIG-Bench Hard and BBQ, highlighting the gap between surface coherence and faithful reasoning [3].

A second line evaluates performance and accuracy with diagnostic setups and standard metrics [16], but also emphasizes how improvements are achieved. In oral/maxillofacial surgery, CoT with ChatGPT-4 improved internal consistency (higher Cronbach’s alpha) and reliability with small accuracy gains (+3.1%), which limits the interpretability of results. Beyond single-shot scoring, SelfCheck adds a four-stage verification with weighted voting that increases precision on GSM8K, MathQA, and MATH, at the cost of significant computational consumption [17]. GridPuzzleEval introduces PuzzleEval to uncover reasoning failures that aggregate scores mask [18]. From a selection perspective, EPVI extends V-information to black-box settings: choosing instances with high EPVI yields improvements of up to +30% in accuracy, although computational complexity and the lack of clinical validation remain obstacles as reported in [19].

A third line examines effectiveness and limitations by connecting theoretical capacity, empirical behavior, and robustness. Theory bounds constant-depth transformers with autoregressive CoT steps that expand representable circuits, but face scalability constraints in practice [100]. Counterfactual and ablation studies show that the strength of CoT often lies in structural coherence rather than strict logical validity, maintaining ≈80–90% of baseline performance even when chains are flawed [101,102]. In information retrieval, query expansion can outperform CoT rationales in ≤20 B models, underscoring a trade-off between complexity and efficiency, and the limits of textual chains as a universal tool [103]. Robustness studies confirm sensitivity to noisy reasoning: the NoRa dataset induces accuracy drops of 1.4–40% in GPT-3.5 [20].

Finally, while our review and experiments reflect the state of reasoning models and CoT research up to mid-2025, the proposed evaluation framework is architecture-agnostic. As newer iterative and verifier-augmented reasoning systems become available with stable and reproducible access to their generated chains-of-thought, the same multidimensional, text-based analysis can be directly applied to them.

3. Methodology

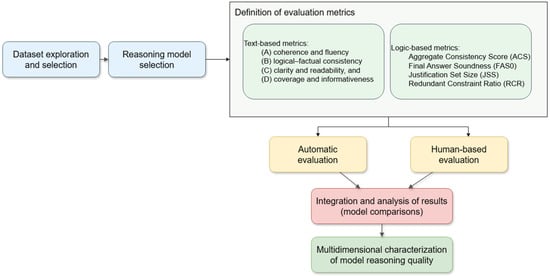

We apply a quantitative, multidimensional text-evaluation framework (Figure 1). The framework spans four core axes that are standard in text quality assessment: (A) coherence and fluency, (B) logical–factual consistency, (C) clarity and readability, and (D) coverage and informativeness. These axes are instantiated through a combination of automatic text-based metrics, logic-based scores (ACS, FAS0, JSS, RCR), and an aligned human evaluation protocol described in the following subsections. Where applicable, scores are normalized to [0, 1] to facilitate cross-metric comparisons, and hyperparameters are fixed across models to promote reproducibility. We deliberately avoid external grammar-correction tools (e.g., LanguageTool) to keep the framework lightweight and easy to integrate.

Figure 1.

Overview of the multidimensional evaluation methodology for reasoning models, from dataset selection to the integrated automatic and human-based characterization of reasoning quality.

3.1. Dataset and Evaluated Models

We evaluated on GSM8K, a dataset of human-written arithmetic problems (~1.3 k–1.4 k). We used the gold prompt and answer, while gCoT traces were generated by each model under controlled protocols. All models were run with the same deterministic decoding configuration (temperature = 0, top-p = 1, fixed maximum generation length, no external tools), so that cross-model differences arise from the models themselves rather than from bespoke sampling parameters.

The models selected emphasize reasoning capabilities:

- -

- DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B (DS_LL): An 8B-parameter dense model distilled from DeepSeek-R1 using Llama-3.1-8B-Base, fine-tuned on R1-generated samples for enhanced math, code, and logical reasoning; supports 128 K context and is optimized for efficient inference.

- -

- DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B (DS_QW): A 7B-parameter dense distillation from DeepSeek-R1 on Qwen-2.5-Math-7B, tuned for chain-of-thought reasoning with 128 K context.

- -

- GPT-OSS-20B and GPT-OSS-120B (GPT_12, GPT_20): Open-weight models under Apache 2.0; the 20B variant (21B total, 3.6B active via MoE (Mixture of Experts)) targets edge devices (16 GB memory), while the 120B (117B total, 5.1B active) deployable on a single 80GB GPU.

- -

- Qwen3-4B-Thinking-2507 (QWEN3_THK): A 4B-parameter causal LM from Alibaba’s Qwen3 series, featuring pre- and post-training enhancements for “thinking” mode; supports up to 262K-token context (extendable to 1 M) and excels in explicit reasoning traces.

The evaluated models were deliberately selected to represent reasoning-specialized systems that natively produce explicit chains of thought under deterministic decoding. Instruction-tuned or chat-oriented models were not included, as they often require additional prompting strategies to elicit step-by-step reasoning, introducing confounds related to prompt design rather than intrinsic gCoT properties. Accordingly, the present analysis focuses on deliberative reasoning models, and does not claim universality across all instruction-tuned LLMs.

3.2. Automatic Metrics

- A.

- Coherence and Fluency

This axis evaluates the gCoT’s logical–linguistic structure, spanning global organization, local continuity, and surface naturalness.

- a.

- Global coherence via Coherence-Momentum

We employ the Coherence-Momentum model as a comparative scorer [104]. For each gCoT , we generate degraded variants using operations that perturb discourse structure while preserving content tokens: sentence shuffling, random sentence drops (~20%), adjacent pair swaps (stochastic), and removal of discourse connectors. We then aggregate the probability that the original is more coherent than its degraded counterparts:

with the score given by the model, is the sigmoid function, and the temperature is In all experiments, Coherence-Momentum is computed with samples per chain, chosen as a practical trade-off between computational cost and variance reduction; we use this metric to characterize qualitative coherence profiles rather than to make thresholded decisions based on its absolute value. We report per-item mean probability, std, and a z-score vs. chance 0.50.

- b.

- Local semantic cohesion (embedding-based)

Using Sentence-Transformers (all-mpnet-base-v2 [105]), we compute adjacent sentence cosine similarity [106]:

and a multi-hop cohesion with geometric decay over lags , normalized by the total weight. To control for topicality, we estimate a shuffle baseline by averaging adjacent similarity over multiple random sentence permutations [107] and define a corrected cohesion . We further apply penalties for abrupt drops and near-duplications on the adjacent track (thresholds , ), yielding a final score:

As diagnostics we also report mean/std/min/max of adjacent similarity and an auto-similarity band ratio (mass near the diagonal of the sentence–sentence similarity matrix) [108]. In all our experiments, this metric is used with a single fixed configuration across models: we compute multi-hop cohesion with and geometric decay over lags, estimate the shuffled baseline with 10 random permutations, and apply jump/repetition penalties with thresholds and and weights and ; the band-based density measure uses and , and all sentence embeddings are obtained with the all-mpnet-base-v2 model.

- c.

- Context-aware coherence (cross-encoder)

For Q–gCoT alignment, a CrossEncoder (coherence-all-mpnet-base-v2 [109]) scores the coherence between the problem and the whole gCoT , returning a single scalar per item.

- d.

- Surface fluency (perplexity)

We quantify surface fluency via perplexity (PPL) under a fixed causal LM (default GPT-2 [110]). For a tokenized gCoT and the subset of scored indices (with ):

This is the standard relation [111]. Two models’ PPLs are only directly comparable when tokenization/vocabulary and test set are identical [112].

- B.

- Logical Consistency and Congruence

- a.

- Consistency using Natural Language Inference

We quantify whether a generated gCoT is non-contradictory with the input question and locally self-consistent. The metric uses a Natural Language Inference (NLI) classifier to obtain probabilities over {entailment, contradiction, neutral} for sentence pairs ; we denote the model’s contradiction probability. Higher scores indicate greater consistency (i.e., less contradiction) [113,114,115].

Q2gCoT consistency: Let Q be the question and the sentence sequence of the normalized gCoT. We score contradiction between Q and each , and aggregate:

These capture worst-case and average non-contradiction, respectively.

Intra-gCoT consistency: For a window size k, each sentence (for ) is compared against up to k preceding sentences . We penalize the strongest local contradiction and average over positions:

By construction, empty or single-sentence gCoTs yield 1.0. We use MoritzLaurer/DeBERTa-v3-large-mnli-fever-anli-ling-wanli (a DeBERTa-v3 NLI mixture [116]).

- b.

- Alignment-based Consistency (AlignScore)

We quantify whether a gCoT is textually supported by the input question and whether the final answer is implied by the gCoT. We adopt AlignScore, a unified alignment metric for factual consistency that models directional information alignment between two texts; higher values indicate stronger support/implication [117].

Let be the question, g the gCoT, and the final answer. We report two scores in [0, 1]:

where is the AlignScore alignment function. penalizes reasoning steps not grounded in the prompt; penalizes answers not derivable from the provided reasoning. These scores assess directional textual consistency rather than absolute factual correctness outside the given context.

- c.

- Factual Consistency

Detect factual conflicts between the input and the gCoT under a source–summary framing. We apply FactCC with (source = input, summary = gCoT) [118].

- C.

- Linguistic Clarity

We evaluate clarity in gCoT using four essentials differentiating metrics that capture general readability, explicit reasoning structure, handling of technical symbols, and parser-free syntactic simplicity. All are computable with local heuristics and corpus-internal normalization.

- Readability (Flesch Reading Ease, RD)

For a gCoT c with S sentences, W words, and total syllables Y [119,120]:

We map FRE to [0, 1] by robust percentile scaling over the corpus (p5 (a)–p95 (b)), yielding RD (c) (higher = easier).

where higher values indicate easier-to-read text.

- b.

- Step-Structure Explicitness (SE)

Regex-based detection of explicit step markers (line-initial “Step #”, numbered/bulleted lists, and temporal order words) [121,122].

- c.

- Definition Coverage (DC)

We extract candidate symbols from inline math and surface forms. A symbol is “defined” if preceded by patterns such as let/denote/define/where or “:=/=”. With U used and D defined,

- d.

- Syntactic Simplicity (SS_lite)

We approximate complexity as a weighted combination of average sentence length (W/S), comma/semicolon rate, and subordinators per sentence (e.g., because, although, if, while, since) [123,124]:

We invert and normalize:

- e.

- Aggregate Core Clarity Index

Finally, we propose an equal-weight aggregate over the core metrics:

This is a simple aggregation of the four normalized components; it is not intended as an optimal weighting scheme, but as a straightforward way to consider all of them jointly.

3.3. Human Evaluation

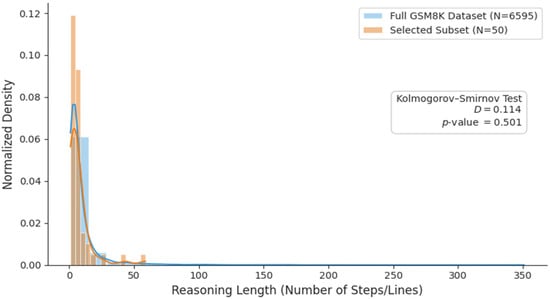

To complement the automatic metrics, we conducted a controlled expert evaluation using Label Studio that permits standardized presentation, randomized model order, and anonymized exportation. Four evaluators rated 50 representative problems from GSM8K (selected by reasoning length). For each problem, we collected ratings for five gCoTs (one per model), totaling 1000 judgments per dimension (50 problems × 5 models × 4 raters). Because this is a cost-constrained, length-stratified subset, the human study is used as complementary, exploratory evidence alongside the automated analyses.

To validate representativeness along the sampling dimension, we compared the reasoning-length distribution of the selected subset with that of the full GSM8K dataset using a two-sample KS test.

The raters, all with graduate-level training or professional experience in computer science and machine learning, rated the gCoTs following written guidelines and a prior briefing; the logical verification metrics (ACS, FAS0, JSS, RCR) are computed automatically and do not rely on manual proof checking.

Problems were sampled in bands of gCoT length to cover short, medium, and longer chains across models, without conditioning on correctness or problem category. As such, the human study is exploratory in scope and is not intended to provide an unbiased estimate over all GSM8K problem types or to support precise, fully powered model-level comparisons.

The evaluated dimensions were cohesion, coherence, clarity, and informativeness, using a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high) with a unified rubric and sample anchors:

- -

- Cohesion: local semantic continuity between steps.

- -

- Coherence: global logical organization of reasoning.

- -

- Clarity: linguistic fluency and structural readability.

- -

- Informativeness: relevant, non-redundant content.

The automatic coherence signals (e.g., Momentum, cross-encoder, embeddings) approximate these phenomena at different scales but are not exact equivalents of the human constructs. Reliability was estimated using Cronbach’s α per dimension. Differences between models were tested using Friedman (repeated measures) and paired Wilcoxon tests with FDR correction.

3.4. Logical Verification

To address the gap in deductive validity and leverage the dataset’s arithmetic nature, we incorporate a block of logic-based metrics with Z3 that assess whether the procedural steps support the final result and how tight or redundant the justification is. We operate on a Z3 solver with assert_and_track, which enables the identification of unsatisfiable cores and the analysis of each premise’s contribution.

Computing these metrics requires a structured input (Intermediate Representation, IR) that faithfully reflects the semantics of the reasoning chains. For each chain, one author first drafted an IR that encodes the operations in the surface order used by the model, and a second domain expert then checked it against the original GSM8K problem, the gold answer, and the generated chain; any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus into a single canonical arithmetic reading. We do not enumerate multiple alternative IRs per chain: algebraically equivalent rewritings collapse to the same underlying constraint system, and genuinely underspecified or inconsistent chains are reflected directly in the logical metrics (ACS, FAS0, JSS, RCR) rather than being excluded. Because this validation is manual, in this phase we limit the evaluation to the chains from 50 problems across 5 models (total: 250 IRs). For transparency, we provide the IR artifacts used for logical verification (problem × model) together with a brief schema and worked examples in the in the public repository (see the Data Availability Statement).

For each chain, we construct an IR with typed variables and a sequence of steps. The IR supports: set (constant assignment), update (add/sub/mul/div), set_expr (binary expression), and assertions assert_eq/assert_ge/assert_le. Each step is inserted with assert_and_track, preserving a track_order for downstream analysis. When the IR includes an equality final_answer == c, we take c. Otherwise, we apply textual heuristics over the model’s output (patterns such as “#### 42”, “final answer … 42”, etc.), as the dataset typically ends in a numeric value. This extracted answer serves as the target for entailment tests. These extraction and shortcut rules are intentionally tailored to the GSM8K answer format; porting the logical-verification block to other datasets would require adapting these heuristics to their specific output conventions.

To avoid “pasting” the answer, we mark as a shortcut any track that directly fixes final_answer == ans, or that fixes a bridge variable connected to final_answer to the same value ans. For validity and justification tests we compile the system without those tracks (S_without_shortcuts). The metrics used are:

- Aggregate Consistency Score (ACS)

Assesses in then range [0, 1], the global consistency of the premise set (base system, without negated goals and without shortcuts).

- -

- If the system is SAT, ACS = 1.0.

- -

- If it is UNSAT, we use:

- -

- If Z3 returns “unknown”, ACS = None.

- b.

- Final Answer Soundness (FAS0)

Checks whether the shortcut-free procedure entails the final value. We construct:

- -

- If is UNSAT, FAS0 = 1 (the chain entails the result).

- -

- If it is SAT, FAS0 = 0.

- -

- If essential information is missing (e.g., final_answer or ans), FAS0 = None.

- c.

- Justification Set Size (JSS)

Quantifies how tight the minimal justification is, and is defined only when FAS0 = 1 (i.e., when S_neg_ans is UNSAT):

where N is the number of tracks in and is the UNSAT core obtained when refuting “”. High values indicate a dense justification; low values indicate a light justification.

- d.

- Redundant Constraint Ratio (RCR)

Measures the proportion of premises that are not individually necessary to entail the answer once shortcuts are removed. It is defined only when FAS0 = 1 (i.e., when the chain without shortcuts already entails the final answer).

For each tracked premise in (the negated goal is never counted as a premise), test whether remains UNSAT. If it does, p is redundant.

Score. Let N be the number of tracked premises in , and let R be the number of premises that are redundant under the single-deletion test. Then .

High RCR indicates a redundant justification (many premises can be dropped without losing entailment); low RCR indicates a lean justification (most premises are individually necessary). Because any premise outside an UNSAT core is removable, RCR is bounded below by when JSS is computed from the same (solver-returned) core; equality need not hold since cores may be non-unique.

The construction of intermediate representations (IRs) is based on expert interpretation of the generated chains and the GSM8K problems. In this study, each IR was drafted by one author and validated by a second domain expert through consensus; no independent third-party reconstruction or formal inter-rater agreement was conducted. Consequently, the resulting logical verification metrics should be interpreted as preliminary operational indicators rather than fully validated deductive proofs. Alternative, equally valid formalizations of the same reasoning trace may exist and could lead to different logical outcomes.

4. Results

4.1. Representative Metrics by Model

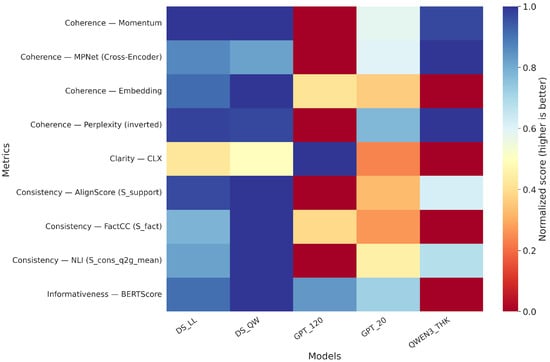

This subsection synthesizes nine representative metrics covering the four families evaluated on gCoT: coherence (Coherence-Momentum, Cross-Encoder MPNet, Embedding; Perplexity), clarity (CLX), consistency (AlignScore–S_imp, FactCC, NLI–mean), and informativeness (BLEURT). Table 1, reports, for each metric, the per-model average. For visual comparison, Figure 2 displays normalized scores; Perplexity is inverted in the figure so that higher values indicate better performance. Coverage was ≥98%, except for coherence-embedding in GPT_120 (1007/1319; 76.3%).

Table 1.

Per-model means for the representative metrics (Perplexity is shown non-inverted in the table).

Figure 2.

Comparison of reasoning-length distributions between the full GSM8K dataset and the 50-item subset used for human and logical evaluation. A two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicates no significant difference between the distributions.

The three semantic coherence signals (Momentum, MPNet, Embedding) show aligned tendencies across models, while Perplexity offers a complementary proxy of surface fluency and, once inverted in the figure, remains visually consistent with the other metrics. Within consistency, from gCoT to answer implication (AlignScore–S_imp) and average non-contradiction (NLI) capture different textual facets; FactCC adds summary-style factual verification. The concurrent presence of clarity (CLX) and informativeness (BLEURT) across all models indicates that gCoT exhibit measurable linguistic structure and evaluable informational content—an aspect revisited in the Discussion when considering explanatory value beyond internal fidelity.

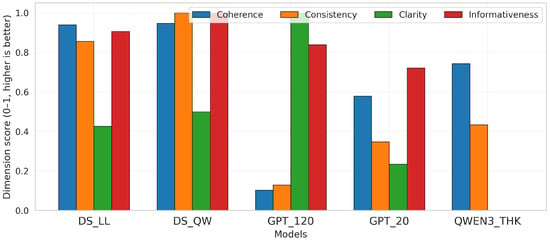

4.2. Dimension-Level Profile and Global Ranking

This subsection summarizes performance by four dimensions aggregating the nine representative metrics reported before. For each metric, per-model means were row-normalized (min–max), inverting Perplexity so that higher values indicate better performance; dimension scores correspond to the average of normalized metrics within each family. A Global Index is computed as the mean of the four-dimension scores. Results are presented in Table 2 and summarized visually in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Dimension-level scores and Global Index per model.

Figure 3.

Representative metrics normalized by metric (higher is better; Perplexity inverted).

Coherence and consistency exhibit the largest between-model separation after normalization. Under the global index, deepseek-r1-distill-qwen-7b attains the highest composite score, followed by deepseek-r1-distill-llama-8b@q8_0. Clarity derives from the CLX component and reaches its maximum in gpt-oss-120b under row-wise normalization, whereas informativeness (BLEURT) reaches its maximum in gpt-oss-20b. Row-wise min–max normalization ensures comparability across heterogeneous metrics while preserving within-metric ordering; perplexity undergoes inversion prior to normalization. Dimension aggregation, computed as the mean across normalized submetrics, yields a single score per family that reflects the metrics used.

4.3. Results by Dimension

4.3.1. Coherence

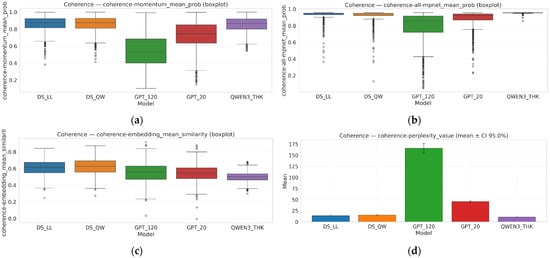

We report distributions per model. Figure 4 shows the results. Distributions for Momentum and MPNet shift toward higher values in the models with larger averages, with moderate dispersion; Embedding reproduces the pattern with slightly smaller amplitude. Perplexity exhibits the expected inverse behavior.

Figure 4.

Dimension-level profiles by model (higher is better; Perplexity inverted).

4.3.2. Consistency (Logical–Factual)

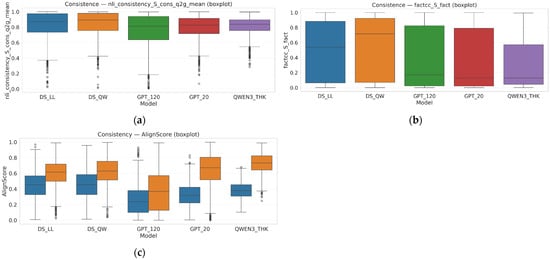

The three components that were examined are non-contradiction with the question (NLI, worst case and mean), directional alignment (AlignScore: support from Q to gCoT and implication from gCoT to answer), and factuality (FactCC). Figure 5 shows per-model distributions by submetric.

Figure 5.

Comparative coherence metrics across reasoning models. Boxplots of four coherence estimators: (a) momentum-based mean probability, (b) MPNet-based mean probability, (c) embedding mean similarity, and (d) perplexity value.

NLI signals indicate reduced contradiction in both worst-case and mean views for the models with stronger global averages. In AlignScore, support and implication are clearly separable, with implication being more stringent. FactCC provides complementary summary-style factual verification.

4.3.3. Clarity

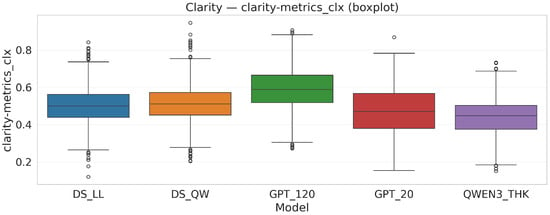

We report the aggregate index CLX. Figure 6 presents the profiles per model for CLX.

Figure 6.

Comparative consistency metrics across reasoning models. Boxplots of (a) NLI-based logical consistency, (b) factual consistency (FactCC), and (c) directional consistency via AlignScore (support/implication, blue S_support (QgCoT), Orange S_imp (gCotanswer)).

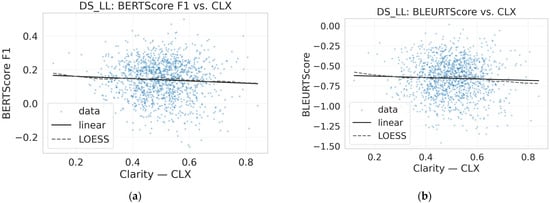

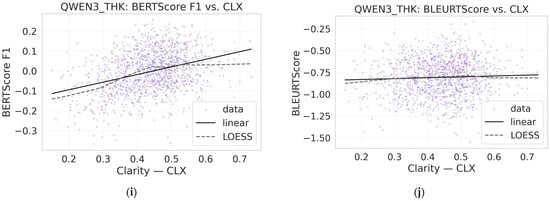

Figure 7 shows the clarity profiles by model and Table 3 describes their components, while Figure 8 shows the informativeness components by model. We report mean informativeness scores and examine the relationship between informativeness (BLEURT; BERTScore) and clarity (CLX). This analysis tests a potential trade-off: richer, more detailed gCoTs may increase informativeness while degrading clarity (e.g., verbosity, redundant steps), whereas highly concise traces may improve clarity while omitting useful content. We first use within-model scatterplots with LOESS/linear fits and confidence bands to visually inspect monotone or nonlinear patterns, and we complement this with simple within-model linear regressions of informativeness on CLX. Across the five models and two informativeness metrics, slopes range from −0.09 to 0.38 (see Table 4): six out of ten are small with 95% confidence intervals including zero, one combination shows a small negative slope (about −0.07), and three combinations show moderate positive slopes (≈0.27–0.38). This pattern suggests that, in our setting, clarity and informativeness are not in strong tension and can often be improved jointly. Methodologically, CLX serves as an aggregate clarity index, while BLEURT and BERTScore capture complementary informativeness signals; LOESS and linear fits together help detect both global and subtle trends.

Figure 7.

Clarity profiles per model. Differences in CLX across models can be explained primarily by explicit step structure (SE) and symbol definition (DC), with smaller contributions from SS_lite and RD (see Table 3).

Table 3.

CLX components by model.

Figure 8.

Informativeness components by model.

Table 4.

Within-model linear regressions of informativeness on clarity (CLX).

The scatterplots (Figure 9) show dense clouds around mid-range clarity. Within each model, most fitted lines are visually close to flat, and where slopes deviate from zero they do so modestly, in line with the regression results described above. Models differ in their overall level of BLEURT/BERTScore (vertical shifts), but within-model trends in informativeness as a function of clarity remain weak in magnitude. Dispersion is fairly uniform across CLX (no funnel pattern), reducing concern that variance alone drives the pattern. Overall, the graphical and regression evidence together suggest that, under our setting, gCoTs can be simultaneously clear and informative, with no marked trade-off.

Figure 9.

Clarity–informativeness trade-off across reasoning models. Panels (a–j) are ordered top-to-bottom, left-to-right: (a,b) DS_LL; (c,d) DS_QW; (e,f) GPT_120; (g,h) GPT_20; (i,j) QWEN_THK. For each pair, the left panel shows INF vs. CLF scatter with a linear fit (±CI); the right panel shows a smoothed diagnostic curve versus CLF (±CI).

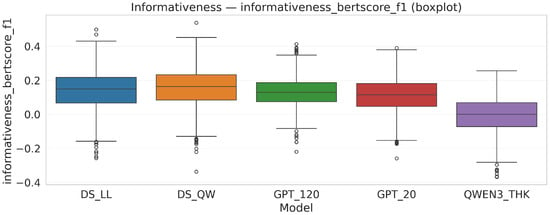

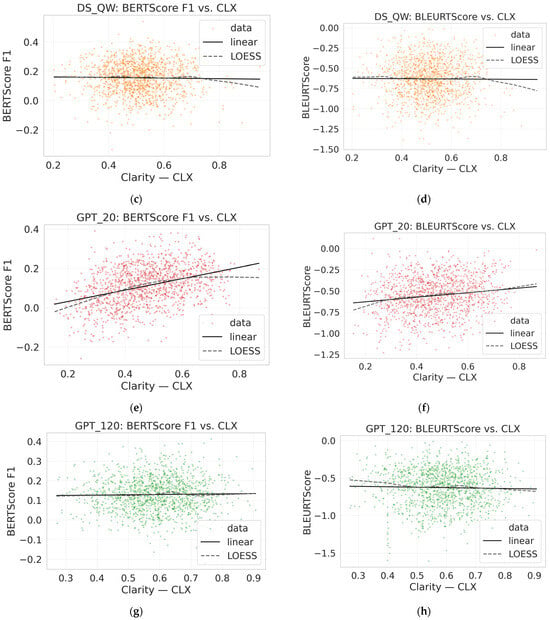

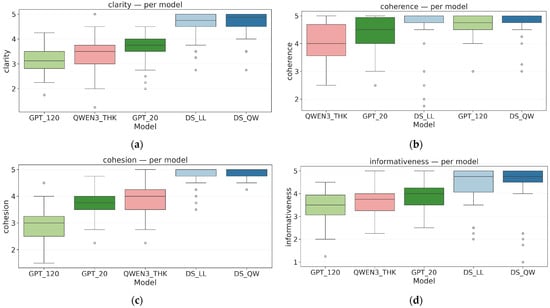

4.4. Human Evaluation Results

Figure 10 shows the result of the human evaluation. Inter-rater reliability was moderate across dimensions (see Table 5). Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.52 to 0.63, with higher agreement for cohesion (α = 0.63) and clarity (α = 0.62), and lower agreement for informativeness (α = 0.52) and coherence (α = 0.55). The moderate-to-borderline agreement for coherence/informativeness indicates non-trivial rater subjectivity and measurement noise; therefore, we interpret human results primarily as evidence for broad patterns and large between-model gaps rather than fine-grained distinctions among near-tied models. The lower values for informativeness and coherence imply a noticeable amount of measurement error in these two dimensions, so human-based model differences on informativeness and coherence should be interpreted as suggestive patterns rather than precise, high-confidence estimates.

Figure 10.

Human evaluation scores across reasoning models. Boxplots of human-rated dimensions: (a) clarity, (b) coherence, (c) cohesion, and (d) informativeness.

Table 5.

Inter-rater reliability (Cronbach’s α) with 95% confidence intervals.

Friedman tests indicated significant differences among the five models across all dimensions (Table 6; all p < 0.001), and the results remain significant under a Bonferroni-corrected threshold (α′ = 0.0125). Kendall’s W suggested effects ranging from moderate (W = 0.248 for coherence) to large (W = 0.746 for cohesion).

Table 6.

Friedman test results by dimension.

To assess sensitivity, we used the standard noncentral chi-square approximation of the Friedman test (df = 4) and Kendall’s W as effect size. Under this approximation, our repeated-measures design with N = 50 problems (k = 5 models) has ≥80% power to detect effects of approximately W ≥ 0.081 under the Bonferroni-adjusted α′ = 0.0125 (and W ≥ 0.060 under α = 0.05). Since all observed omnibus effects exceed this threshold (W = 0.248–0.746), N = 50 is sufficient to reliably detect overall between-model differences; however, the smallest pairwise contrasts among top models may have limited power after multiple-comparison correction. This sensitivity statement pertains to the omnibus test; pairwise detectability depends on contrast magnitude and the multiple-comparison correction.

Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with FDR correction showed that 8/10 pairs differed significantly for clarity, 6/10 for coherence, 8/10 for cohesion, and 7/10 for informativeness.

The mean ratings (1–5) with their confidence intervals show a consistent pattern: DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B achieves the highest scores across all dimensions (clarity 4.65, coherence 4.73, cohesion 4.84, informativeness 4.39), followed by DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B. By contrast, GPT-OSS-120B ranks second in coherence but last in clarity and cohesion (Table 7).

Table 7.

Mean scores per model × dimension (mean ± half-CI).

Visual differences among models are shown in the box plots (Figure 9), where DeepSeek medians cluster in the upper range (≈4.5–5), while GPT-OSS-120B shows greater dispersion and lower scores, particularly in clarity and cohesion.

4.5. Human–Automatic Metric Alignment

To quantify how automatic scores relate to human perceptions, we computed correlations between human ratings and automatic metrics on the overlapping subset only: the 50 human-rated problems evaluated across five models (50 × 5 = 250 problem–model instances per dimension). For each instance, the human score was the mean across four raters (1–5 scale). Automatic metric values were matched to the same instances using the shared problem index.

Because ratings are ordinal and associations may be non-linear, we report Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ). Uncertainty was quantified using a problem-level cluster bootstrap to obtain 95% confidence intervals (resampling problems and keeping the five model instances per problem together). To keep results concise, Table 8 reports, for each human dimension, the automatic proxy within the corresponding metric family with the highest absolute correlation (and for cohesion, within consistency-oriented proxies).

Table 8.

Best-aligned automatic proxy per human dimension (Spearman’s ρ) on the overlapping subset. 95% CIs from problem-level cluster bootstrap.

Table 8 shows moderate alignment for clarity and informativeness, while coherence exhibits only weak alignment even for its best-matching proxy, consistent with partial construct overlap between human judgments and automatic operationalizations.

4.6. Logical Verification

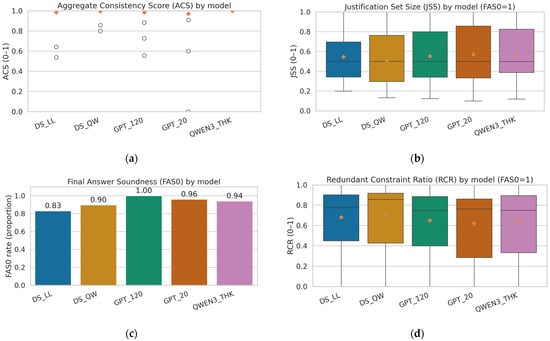

We evaluated logical validity on 50 problems across the five LRMs (250 IRs) using four complementary metrics (Figure 11); per-model values are summarized in Table 9. ACS remained near ceiling across systems (mean ≈ 0.97–1.00, median = 1.00), indicating that most extracted constraint sets are internally consistent, with occasional inconsistencies reflected in ACS values below 1. FAS0—the rate at which chains entail the final answer after shortcut removal—was also high (0.83–1.00). Across the 250 IRs, FAS0 was defined for 245/250 (98.0%); among defined cases, 227/245 (92.7%) entailed the final answer and 18/245 (7.3%) did not. The remaining 5/250 (2.0%) were not evaluable because the final answer could not be reliably extracted. Conditioning on sound chains (FAS0 = 1), JSS clustered in a narrow band (≈0.51–0.57) while RCR remained moderate (≈0.62–0.70), indicating that justifications typically rely on a compact core of premises but also contain a non-trivial amount of individually redundant steps, leaving room for pruning or compression.

Figure 11.

Logical validity across LRMs. (a) ACS by model. (b) FAS0 by model. (c) JSS by model (computed only when FAS0 = 1). (d) RCR by model (computed only when FAS0 = 1). Boxes show median and IQR; whiskers denote Tukey range; diamonds mark means. Higher ACS/FAS0 indicate more self-consistent, answer-entailing chains; higher JSS indicates tighter minimal justifications; lower RCR indicates less redundancy.

Table 9.

Logical validity summary per model. ACS and FAS0 are computed over all items; JSS and RCR only when FAS0 = 1.

The joint presence of high ACS and high FAS0 confirms that gCoTs are not merely accompanying text around a correct output: they typically form arguments that entail the result under our formalization. When verification fails, the dominant failure categories are: (i) missing/unextractable target answers (FAS0 undefined), (ii) non-entailment after shortcut removal (FAS0 = 0), and (iii) occasional internal inconsistencies in intermediate statements (ACS < 1). While small differences across models can be observed (Table 9), this analysis remains a targeted subset and is therefore interpreted as descriptive tendencies rather than a definitive model ranking.

We treat logical verification results as exploratory and report them on a targeted subset.

These logical verification results are reported for a targeted, manually constructed subset and should be interpreted as exploratory. They are intended to characterize typical structural properties of gCoTs under one reasonable formalization, not to provide definitive guarantees of logical correctness.

Statistical power considerations: The logical verification analysis is based on 50 problems per model (250 IRs total). With this sample size, the analysis is sufficiently powered to detect only large effects in logical validity metrics. Small or moderate differences between models—especially for near-ceiling measures such as ACS and FAS0—are unlikely to be detected reliably. Consequently, observed per-model differences should be interpreted descriptively rather than as statistically robust evidence of superiority.

5. Discussion

The following discussion interprets our findings in light of H1, examining how the observed structural, logical, and linguistic regularities support the hypothesis and what they imply for gCoTs as textual artifacts. The results suggest that gCoTs consistently exhibit quantifiable properties in structural coherence, logical–factual consistency, linguistic clarity, and coverage/informativeness as measured by automatic metrics and corroborated by expert human ratings. Our goal is not to crown a single superior model, but to show that, in general, gCoTs possess exploitable properties regardless of individual differences. For example, coherence metrics such as Coherence-Momentum (mean ≈ 0.75–0.86) and embedding-based semantic cohesion (≈0.50–0.62) indicate organized discourse structures, while perplexity suggests fluent surface-level generation. Consistency measures (e.g., AlignScore implication, S_imp ≈ 0.38–0.73; and NLI non-contradiction, ≈0.76–0.84) point to textual anchoring to the prompt without widespread factual conflicts, further supported by FactCC (≈0.29–0.54). Clarity, aggregated via the CLX index (≈0.44–0.59), highlights readable, step-explicit outputs, and BLEURT (≈−0.81 to −0.55) indicates substantial content density.

Complementing these proxies, direct logical verification results (Figure 10; Table 9) show near-ceiling self-consistency (ACS ≈ 0.95–1.00) and high final-answer entailment (FAS0 ≈ 0.85–1.00); conditional on entailment, minimal justifications are compact (JSS ≈ 0.68–0.80) with moderate redundancy (RCR ≈ 0.34–0.50), indicating argument-like structure beyond textual alignment.

Notably, we do not observe a systematic trade-off between clarity and informativeness, suggesting gCoTs can be simultaneously accessible and content-rich. From a narrative standpoint, the experiments support gCoTs as explanatory artifacts that extend beyond strict fidelity.

These observations fit within the broader CoT literature reviewed in Section 2. Prior evaluation frameworks largely focus on fidelity to internal mechanisms, overall task accuracy, or robustness to noisy reasoning, but typically treat chains as auxiliary tools for performance rather than as structured textual artifacts. This work, by contrast, shows that gCoTs exhibit stable profiles in coherence, clarity, informativeness, and logical–factual consistency, even when not perfectly sound. To the best of our knowledge, there is no directly comparable study that offers a text-centered, multidimensional characterization of automatic generate CoTs.

However, all interpretations are bounded by the nature of the GSM8K dataset. Extending these observations to other domains requires further evaluation and may alter the balance between structural, linguistic, and factual dimensions. These logical metrics are informative but approximate.

5.1. Automatic vs. Human Evaluations Analysis

Human evaluation supports the presence of structural and linguistic properties in gCoTs that go beyond factual fidelity; however, it is also important to discuss that human and automated evaluations do not measure identical constructs, even when they share similar dimensional labels. Automated scores operationalize model-based indicators (learned similarity/consistency signals and scoring functions), while human evaluations reflect perceived interpretability, readability, and communicative quality. We explicitly acknowledge this discrepancy in constructs as an inherent limitation to interpreting cross-modality agreement.

Accordingly, the human-automated alignment analysis on the overlapping subset (50 issues × 5 models = 250 instances) shows only partial convergence. Alignment is moderate in terms of clarity and informativeness, while coherence exhibits a weaker association, even for its best-aligned indicator. Importantly, the human sample remains small compared to the automated evaluation of 1319 gCoTs. Therefore, we consider these correlations as exploratory indicators of alignment, rather than high-certainty validation. Furthermore, since the human study is based on repeated measures (five model outcomes per problem), the effective information is limited by the number of problems (N = 50), and fine-grained pairwise distinctions, especially among the top-performing models, should be interpreted with caution.

An additional practical factor is that several automated dimensions support multiple operationalizations (e.g., consistency can be calculated using embedding similarity, probability-based measures, or NLI-type consistency), whereas the human protocol assigns a single scalar rating per dimension. Consequently, the observed alignment depends on the proxy selected, and weak correlations do not necessarily imply that the dimension is “invalid”; rather, they may indicate that a given proxy captures only one facet of multifaceted human judgment. This multiplicity also helps explain areas of divergence, such as models that perform well on semantic consistency proxies but are perceived as unclear due to verbosity, redundancy, or stylistic exposition, and vice versa.

From a statistical perspective, two additional considerations support a complementary interpretation. First, inter-rater reliability is only moderate in our human-rated study (α ≈ 0.52–0.63), implying significant measurement noise that attenuates the maximum observable correlation between any automated proxy and the human ratings. Second, both human (ordinal) and automated (heterogeneous scale) ratings motivate the use of rank-based measures of association; therefore, we do not interpret the absolute values of the metrics as directly comparable to the human scales. The results support our methodological stance: automated metrics provide a scalable and consistent measurement across the entire dataset, while human ratings contextualize perceptual quality within a cost-constrained subset, and metric-human correlations should be interpreted as exploratory evidence of alignment, rather than strict equivalence.

5.2. Actionable Properties

In arithmetic problem-solving tasks such as GSM8K, the properties exhibited by gCoTs could be leveraged to improve transparency and user interaction where appropriate. Global coherence (e.g., Coherence-Momentum) and local semantic cohesion indicate that gCoTs can organize complex problems into manageable sequences that emulate reasoning flows. This organization, together with clarity metrics such as Flesch Reading Ease (normalized RD ≈ 0.53–0.59) and step explicitness (SE ≈ 0.09–0.51), could help reduce cognitive load and facilitate understanding in educational or decision-support contexts. Directional consistency measured by AlignScore (implication being stricter than support) suggests anchoring to prompts, although derivations may remain partial; this can be used to flag uncertainty and support confidence calibration. Informativeness, approximated with BLEURT, indicates that gCoTs often contribute useful decompositions or additional content that complements human reasoning without requiring full interpretability of the internal model.

Logical verification metrics make these properties operational. FAS0 can gate downstream use by filtering chains that do not entail the answer; JSS surfaces minimal supporting sets for inspection or teaching; RCR flags compressible redundancy for pruning or summarization. Together, they enable verification, ranking, and chain compression policies that leverage gCoT structure rather than raw accuracy alone.

5.3. Logical Validity

Our framework includes a direct assessment of logical validity over an expanded subset of 50 problems per model (250 IRs total). Chains are highly self-consistent (ACS) and, in most cases, entail their final answers (FAS0). In our sample, FAS0 is defined for 245/250 IRs (98.0%); among defined cases, 227/245 (92.7%) entail the final answer, while 18/245 (7.3%) do not. The remaining 5/250 (2.0%) are not evaluable due to non-extractable final answers. Conditioning on soundness (FAS0 = 1), minimal justifications exhibit stable compactness (JSS) with moderate redundancy (RCR), indicating that—under our IR abstraction—gCoTs can often be mapped to compact, argument-like justifications beyond mere answer fidelity, while still leaving room for pruning/compression.

At the same time, these metrics are not formal proofs. They provide an operational approximation of deductive strength at the level of answer entailment and constraint usage within the extracted IR. When verification fails, the dominant failure modes are (i) missing/unextractable targets (FAS0 undefined), (ii) non-entailment after shortcut removal (FAS0 = 0), and (iii) occasional internal inconsistencies in intermediate statements (ACS < 1). Overall, this clarifies that the explanatory value of gCoTs is not purely narrative: much of it is verifiably structured under our formalization, although it remains short of formal theorem proving.

5.4. Metric Limitations

The employed metrics serve as useful proxies for profiling gCoTs but are inherently approximations, many not originally designed for this context, thereby introducing potential biases and limitations. For instance, embedding-based cohesion (using Sentence-Transformers all-mpnet-base-v2) and cross-encoder coherence (coherence-all-mpnet-base-v2) adapt semantic-similarity techniques from general NLP tasks to measure discourse flow, but may overemphasize topical overlap at the expense of nuanced reasoning transitions. Similarly, AlignScore and FactCC, although effective for factual consistency in summarization, approximate directional support in gCoT without accounting for domain-specific arithmetic logic in GSM8K. This proxy nature is compounded by black-box evaluation of black-box outputs: metrics such as DeBERTa-v3-large-mnli-fever-anli-ling-wanli for NLI and BLEURT for informativeness depend on pretrained language models, creating layered opacity in which evaluation relies on SOTA NLP performance while lacking transparency about error modes. Despite these constraints, such models represent the state of the art, offering reproducible and scalable insights aligned with human judgments in related tasks, although future refinements could incorporate more tailored and interpretable alternatives to mitigate approximation errors.

Logical verification metrics also introduce specific caveats. FAS0 depends on answer correctness and can underestimate reasoning quality when a correct chain is paired with a mis-scored answer; JSS/RCR are computed only when FAS0 = 1, reducing sample size and potentially biasing variance. JSS is sensitive to step granularity, and RCR may penalize benign elaboration. These are principled approximations of deductive behavior—not substitutes for formal proof checking—yet they offer actionable signals at scale. In our study, these logic-based metrics are applied to a manually constructed subset of 250 intermediate representations (≈4.0% of the 1319 chains), selected to span different gCoT lengths. Accordingly, the reported ACS/FAS0/JSS/RCR statistics should be interpreted as exploratory and not as fully representative of the entire dataset.

The logical verification analysis is exploratory in nature and is conducted on a targeted, manually constructed subset of chains. As a result, per-model differences in logical metrics are intended to be interpreted descriptively, rather than as statistically powered evidence of model-level superiority.

All evaluated models are reasoning-specialized and natively generate explicit chains of thought. As a result, the findings do not directly generalize to instruction-tuned or chat-oriented models. Including such baselines to contrast prompt-dependent versus native gCoT behavior is left for future work.

5.5. Applications and Risks

Even when gCoTs display narrative-like properties—coherent, clear, and informative—their practical uses require careful examination, particularly in distinguishing and extracting salient information from extraneous or misleading content. Potential applications include educational tools where gCoTs decompose problems for learners, diagnostic aids in healthcare that verbalize decision paths, or debugging interfaces for developers to inspect model reasoning. A central challenge persists: narrative richness (e.g., high informativeness without clarity trade-offs) can introduce spurious details or verbose derivations, complicating the isolation of critical insights from filler. For example, while coverage exceeds 98% on some metrics, incomplete implications in AlignScore suggest that users may need to navigate partial chains, risking over-reliance on superficial coherence. Addressing this requires techniques such as saliency mapping or automated summarization to extract key steps, ensuring that exploitable properties translate into reliable, actionable value without amplifying hallucinations or inherent biases in LLM outputs.

In practice, FAS0-aware gating and JSS/RCR-guided pruning can reduce cognitive load while preserving essential reasoning content. Care is needed to avoid overfitting to these metrics (e.g., optimizing for low RCR at the cost of helpful redundancy), which we mitigate by pairing them with clarity/coverage indicators and human spot checks.

Extension to Other Reasoning Domains

This study is intentionally scoped to GSM8K-style arithmetic reasoning. While several components of our evaluation are broadly applicable, the logic-based verification block (IR construction + Z3 + shortcut rules) leverages the arithmetic structure and answer conventions of GSM8K. Extending the full framework to other reasoning domains is therefore not a plug-and-play transfer: it would require a domain-appropriate intermediate representation, domain-specific extraction rules, and a new validation procedure to ensure that the symbolic constraints faithfully reflect the intended semantics of the reasoning traces.

Other domains differ in what constitutes a valid step and what kind of evidence is expected. In non-arithmetic settings, a symbolic solver may not be the right substrate; alternatively, the logical-verification block could be replaced by domain-suitable formal checkers while retaining the multidimensional structure of our framework. We therefore view cross-domain evaluation as a natural and important extension, but it requires additional methodological design choices beyond the present scope.

6. Conclusions

We proposed and applied a multidimensional framework to characterize gCoT beyond fidelity. Across four axes—structural coherence, logical–factual consistency, linguistic clarity, and coverage/informativeness—gCoTs exhibit quantifiable and stable properties on GSM8K (~1.4 k items), supporting their value as explanatory artifacts rather than mere byproducts of internal alignment. Taken together, these observations empirically support our central hypothesis H1 that, on GSM8K arithmetic problems, auto-generated chains-of-thought produced by highly capable reasoning models exhibit stable, measurable properties beyond answer fidelity.

Complementing automatic metrics, a controlled expert human evaluation (four raters; 50 representative items × five models) complementing the automated analyses at the level of broad patterns and large between-model gaps. Given this level of agreement, we interpret human results as a complementary, exploratory view that supports broad patterns and large differences across models, rather than as a definitive basis for fine-grained pairwise ranking. Importantly, it also revealed divergences from automatic metrics—most notably in clarity and cohesion for GPT-OSS-120B. In this case, the model often produces long, locally fluent but verbose and partially repetitive chains that receive high CLX scores (token-level fluency) yet are perceived by experts as cluttered and harder to follow, a gap further amplified by the fact that CLX is computed on the full GSM8K set whereas human ratings come from a small, length-stratified subset. Together, these findings indicate that human and automatic evaluations are complementary: they show convergence on overall patterns (e.g., the strong human profile of DeepSeek-Qwen-7B) while highlighting targeted discrepancies that refine interpretation. The logical verification results are consistent with this picture: high ACS/FAS0 with compact justifications (JSS) and moderate redundancy (RCR) indicate that much of the explanatory value in gCoT reflects usable structure, not only narrative appeal.

From a theoretical standpoint, these results support a multidimensional view of gCoTs as structured textual artifacts whose coherence, logical–factual consistency, clarity, and coverage can be analyzed separately from, yet in relation to, task accuracy and internal fidelity. This perspective bridges fidelity-centric evaluations with user-facing notions of explanation quality and provides a basis for future work on model-agnostic explanation schemes.

Results are bounded by the arithmetic focus of GSM8K and by the proxy nature of several metrics not devised for stepwise deductive validity; thus, logical soundness is only partially and approximately observed—we complement proxy metrics with direct logical verification (ACS, FAS0, JSS, RCR), which improves coverage but still falls short of formal proof. Human findings, while consistent and significant, stem from a curated subset (50 items) selected in reasoning-length bands to cover short, medium, and longer chains and designed for representativeness rather than exhaustiveness; accordingly, they should be interpreted as illustrative evidence about how experts perceive the multidimensional profiles of gCoTs for that slice of GSM8K, rather than as a fully powered, unbiased basis for precise model-level differentiation between individual models or for generalizing to all problem types.

Regarding future research directions, the framework is reproducible and suitable for extending to (i) stronger logical verification (symbolic verifiers; programmatic proof checkers; deductive NLI variants), (ii) broader domains (non-numerical and multimodal benchmarks), and (iii) policy mechanisms (verification, reranking, compression) that combine FAS0/JSS/RCR with clarity and coverage signals to control verbosity and bias. An additional and important line of future work is to study the practical utility of gCoTs in trust-sensitive settings—i.e., contexts where increasing user confidence or calibrated certainty is desirable (e.g., high-stakes decision support, educational tutoring, or expert workflows). A practical next step is to hybridize evaluation—combining adapted proxies with targeted human validation—to improve robustness and to systematically map convergence/divergence zones between human and automatic judgments. This will help bridge the gap between narrative appeal and reasoning soundness, sharpening the explanatory utility of gCoTs in user-facing AI.

This study is limited in scope in several ways. First, our analyses focus on GSM8K and on a fixed set of contemporary reasoning models, which constrains the generality of the observed patterns. Second, our framework characterizes gCoTs purely as textual artifacts and does not attempt to infer internal model mechanisms. Third, the human evaluation, while expert-based, is limited in scale and inter-rater agreement was moderate overall, with clarity and cohesion around α ≈ 0.62–0.63, and lower agreement for coherence and informativeness (α ≈ 0.55 and α ≈ 0.52), suggesting non-trivial subjectivity in these dimensions. Accordingly, these ratings should be viewed as illustrative and complementary, suitable for confirming general multidimensional profiles and large contrasts, but not as a fully powered, unbiased ground truth for precise model-level differentiation. These constraints outline natural directions for future extensions. Finally, we fully agree that other plausible choices of text-based metrics exist and that our selection does not exhaust the design space of coherence, consistency, or clarity probes; systematically comparing alternative metric sets would be an interesting line of work on its own, whereas the present article focuses on the multidimensional characterization of gCoTs using off-the-shelf probes rather than on optimizing the metrics themselves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.B.-M. and G.S.-T.; methodology, G.S.-T.; software, L.F.B.-M. and G.S.-T.; validation, L.F.B.-M., G.S.-T. and J.W.B.-B.; formal analysis, G.S.-T.; investigation, L.F.B.-M.; resources, J.W.B.-B.; data curation, L.F.B.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.B.-M. and G.S.-T.; writing—review and editing, J.W.B.-B.; visualization, L.F.B.-M.; supervision, G.S.-T.; project administration, J.W.B.-B.; funding acquisition, J.W.B.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All resources used in this study are openly available at https://github.com/sanchezgt/md-eval-cot (accessed on 29 August 2025). The repository hosts the generated gCoT datasets (standardized JSONL), the full implementations of all metrics (coherence, consistency, clarity, cohesion, and informativeness). The materials are released under an open-source license.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National University of Colombia, Medellín campus, through the project Agnostic Methodological Framework for the Generation of Structured Explanations from Chains of Thought in Large-Scale Reasoning Models (LRMs).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11903. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. How Likely Do Llms with CoT Mimic Human Reasoning? In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 19–24 January 2025; Volume Part F206484-1, pp. 7831–7850. [Google Scholar]

- Turpin, M.; Michael, J.; Perez, E.; Bowman, S.R. Language Models Don’t Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04388. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Huang, M.; Duan, N.; Chen, W. Synthetic Prompting: Generating Chain-of-Thought Demonstrations for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the ICML’23: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; Volume 202, pp. 30706–30775. [Google Scholar]

- Shum, K.; Diao, S.; Zhang, T. Automatic Prompt Augmentation and Selection with Chain-of-Thought from Labeled Data. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 12113–12139. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Banburski-Fahey, A.; Jojic, N. Reprompting: Automated Chain-of-Thought Prompt Inference through Gibbs Sampling. In Proceedings of the ICML’24: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; Volume 235, pp. 54852–54865. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, C.; Hutchins, N.; Le, T.; Biswas, G. A Chain-of-Thought Prompting Approach with Llms for Evaluating Students’ Formative Assessment Responses in Science. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 23182–23190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, A.J.; Deng, S.; Wang, D.; Song, M. CoTEL-D3X: A Chain-of-Thought Enhanced Large Language Model for Drug–Drug Interaction Triplet Extraction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 273, 126953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jang, S.; Kim, B.; Sunwoo, L.; Kim, S.; Chung, J.-H.; Nam, S.; Cho, H.; Lee, D.; Lee, K.; et al. Automated Pathologic TN Classification Prediction and Rationale Generation from Lung Cancer Surgical Pathology Reports Using a Large Language Model Fine-Tuned with Chain-of-Thought: Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e67056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Thongprayoon, C.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Krisanapan, P.; Radhakrishnan, Y.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Chain of Thought Utilization in Large Language Models and Application in Nephrology. Medicina 2024, 60, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rukmono, S.A.; Ochoa, L.; Chaudron, M.R.V. Achieving High-Level Software Component Summarization via Hierarchical Chain-of-Thought Prompting and Static Code Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE), Toba, Indonesia, 7–8 September 2023; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, D.; Yao, Z. An Investigation of Neuron Activation as a Unified Lens to Explain Chain-of-Thought Eliciting Arithmetic Reasoning of LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12288. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.-R. ChainLM: Empowering Large Language Models with Improved Chain-of-Thought Prompting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14312. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, K.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, G. Keypoint-Based Progressive Chain-of-Thought Distillation for Llms. In Proceedings of the ICML’24: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; Volume 235, pp. 13241–13255. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Joo, S.; Jang, Y.; Chae, H.; Yeo, J. CoTEVer: Chain of Thought Prompting Annotation Toolkit for Explanation Verification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.03628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Wu, Z.; Han, J.; Zhai, G.; Liu, J. Evaluating ChatGPT-4’s Performance on Oral and Maxillofacial Queries: Chain of Thought and Standard Method. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1541976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, N.; Teh, Y.W.; Rainforth, T. Selfcheck: Using Llms to Zero-Shot Check Their Own Step-by-Step Reasoning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2308.00436. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, N.; Parmar, M.; Kulkarni, M.; Aswin, R.R.V.; Patel, N.; Nakamura, M.; Mitra, A.; Baral, C. Step-by-Step Reasoning to Solve Grid Puzzles: Where Do Llms Falter? In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 19898–19915. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chu, D.; Sui, D. Analyzing Chain-of-Thought Prompting in Black-Box Large Language Models via Estimated v-Information. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; pp. 893–903. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Tao, R.; Zhu, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, B. Can Language Models Perform Robust Reasoning in Chain-of-Thought Prompting with Noisy Rationales? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.23856. [Google Scholar]

- Alzghoul, R.M.; Tabaza, A.; Abdelhaq, A.; Altamimi, A. CLD-MEC at MEDIQA-CORR. 2024 Task: GPT-4 Multi-Stage Clinical Chain of Thought Prompting for Medical Errors Detection and Correction. In Proceedings of the 6th Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, Mexico City, Mexico, 21 June 2024; pp. 537–556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, Z.; Yin, L.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Li, C.; Du, J.; Sun, Y. LC-SID: Developing a Local LLM-Based Chain-of-Thought Framework for Enhanced Sensitive Information Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Smart World Congress (SWC), Nadi, Fiji, 2–7 December 2024; pp. 2315–2320. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10925018 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Gupta, P.; Jain, N.; Bhat, A. Hate Speech Detection Using CoT and Post-Hoc Explanation through Instruction-Based Fine Tuning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 5–7 June 2024; pp. 823–829. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.-G.; Latif, E.; Wu, X.; Liu, N.; Zhai, X. Applying Large Language Models and Chain-of-Thought for Automatic Scoring. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Fu, X.; Peng, X.; Fan, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, B. Leveraging Chain-of-Thought to Enhance Stance Detection with Prompt-Tuning. Mathematics 2024, 12, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]