Abstract

In early 2025, the Jason-3 satellite’s orbit shifted from an “interleaved” to a tandem configuration with Sentinel-6A, and its Geophysical Data Records (GDR) were upgraded from Version F to G. This study evaluated GDR-G via eight processing approaches, using Jason-3’s last six GDR-F cycles (#394–#399) and first six GDR-G cycles (#501–#506), integrating histogram/geographical distribution analyses of Sea Surface Height Anomaly (SSHA), Significant Wave Height (SWH), Wind Speed (WS), and multi-method validation (e.g., self-cross-calibration). Key findings include the following: GDR-G had significantly lower SSHA noise than GDR-F, with up to ~4 cm SSHA bias from different retrackers/corrections; Adaptive retracker + 3D Sea State Bias (SSB) correction achieved optimal accuracy. Adaptive retracker’s SWH/WS anomalies linked to invalid MLE4 results and non-Brownian waveforms (coastal/sea ice). A detrending method was proposed, and the 41-point Lanczos window was optimal for smoothing. The results from the “detrending method” were consistent with the results based on the SSHA spectrum and classic self-cross-calibration methods. A ~5 mm drop was observed in Jason-3 GDR-G MLE4 baseline SSHA, probably caused by GDR upgrade or geographic sampling mismatch, while Sentinel-6A’s GDR-G upgrade might induce ~1 cm jump. The jumps along with GDR version upgrade highlighted the value of timely in situ absolute calibration.

1. Introduction

Since the launch of the Topex/Poseidon satellite in 1992, satellite altimetry has been one of the indispensable data sources in the oceanography and marine geodesy community [1]. The TOPEX/Poseidon satellite and its successors (Jason-1, Jason-2, Jason-3, Sentinel-6A satellites, all of which are usually called “Jason-series” missions) have routinely provided global sea surface height, significant wave height and sea surface wind speed measurements for over three decades. The data provided very clear evidence of the global sea level rise [2,3]. Sentinel-6A is the first altimetry mission that can simultaneously offer a SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) mode measurement and an LRM (Low Resolution Mode) measurement over the global ocean. SAR mode can significantly improve the along-track resolution and radar Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), hence achieving more precise range measurements. SAR mode is quite different from the previous Jason missions (which use LRM), and SAR/LRM differences are still the subject of research [4,5,6].

The Jason-series missions are defined as the “reference missions” in the altimetry community. In the early life of a new Jason-series satellite, it is crucial to make sure that the measurements are stable and consistent, so the satellite usually operates in the “tandem phase” in which the new satellite (e.g., Sentinel-6A) and its precursor (e.g., Jason-3) share the same ground track, one flying a very short time behind the other. Relative calibration based on the tandem configuration has a significant advantage over crossover calibration: more valid measurement-pairs can be compared, and most errors in the SSHA (Sea Surface Height Anomaly; some researchers may be more familiar with its alias, SLA (Sea Level Anomaly)) computation can be canceled out.

In the past, there was only one tandem phase between successive missions. However, the Jason-3/Sentinel-6A tandem mission has brought many benefits, and a second tandem mission has been strongly recommended [7]. The Jason-3 orbit was maneuvered in January 2025 and returned to its initial orbit (i.e., the same track as Sentinel-6A). Meanwhile, its data (Geophysical Data Records, GDR) was upgraded to a new version labelled “G” [8]. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the performance of GDR-G data as soon as possible.

2. The Evolution of Jason-3 GDR Standards

For modern altimetry missions, data processing methodologies and auxiliary data sources keep evolving, and GDR data standards are upgraded accordingly. In the early phase of the Jason-3 mission (since September 2016, the end of its Cal/Val phase), the GDR adhered to the “GDR-D” standard, and GDR-F was introduced in September 2020 [9]. GDR-F represented a significant improvement over GDR-D: parameters were organized in groups; the reference ellipsoid was changed to WGS84 instead of Topex/Poseidon [10] (there is a ~70-cm bias between the two ellipsoids), a number of auxiliary models for calculating corrections were upgraded, and more importantly, an innovative retracker called the “Adaptive Retracker” was introduced [11,12,13].

For more than a decade, the official GDR products of Jason missions have included two operational retrackers: MLE3 and MLE4 [14]. In both retrackers, waveforms are fitted to the Hayne [15] model (an upgraded version of the classic Brown [16] model), the radar altimeter’s Point Target Response (PTR) is approximated as a Gaussian shape to improve computational efficiency, and the Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) is implemented using the least squares criterion. The only difference between MLE3 and MLE4 lies in the estimation of the satellite off-nadir angle: in MLE3, the off-nadir angle is estimated from the trailing-edge slope of the logarithmic power spectrum, while in MLE4, it is treated as a parameter in the least square procedure. The Adaptive Retracker offers several advantages over MLE3 and MLE4:

A new waveform model (the Adaptive model) has replaced the Brown or Hayne model, adding a parameter correlated with the mean square slope (describing sea surface roughness) of the reflective surface and significantly improving the retracking success rate for peaky waveforms.

The real radar PTR is numerically convolved with the other two terms (flat sea surface response and sea surface elevation pdf) in the analytical waveform model.

A true MLE approach (using the exact likelihood function) is employed, which accounts for the statistics of speckle noise present in echo waveforms.

The GDR-G standard is roughly aligned with GDR-F. Perhaps the most critical improvement is the replacement of MLE3 retracker parameters with Adaptive Retracker parameters (particularly “ssha_adaptive”). Parameters based on the MLE4 retracker remain the default. While MLE3 range measurements are still provided, SSHA cannot be calculated due to the lack of proper correction terms dedicated to the MLE3 retracker. Fortunately, the ionospheric path delay and sea state bias corrections for the Adaptive Retracker were included in GDR-F, enabling the calculation of Adaptive-based SSHA for GDR-F using Equations (1) and (2).

Another improvement worth mentioning is the wet tropospheric correction. Drift in Jason-3’s Advanced Microwave Radiometer (AMR) has also been detected and corrected. Several models were additionally upgraded [8], as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evolution of the Models from Jason-3 GDR-F to Jason-3 GDR-G.

In Table 1, both Mean Sea Surface (MSS) solutions have been upgraded: the CNES_CLS-2015 model was replaced with the Hybrid 2023 model, and the DTU18 model with the DTU21 model. The Hybrid MSS incorporates the advantages of the SCRIPPS_CLS22, CNES_CLS22, and DTU21 MSS models [17]. Among these three models, CNES_CLS22 MSS is most precise in coastal areas, SCRIPPS_CLS22 MSS performs best in the open ocean, and DTU21 MSS best represents the Arctic Ocean’s coastal regions—additionally, when combined with CNES_CLS22 MSS, it optimally represents the entire Arctic and Southern Oceans [18,19,20].

The Finite Element Solution (FES) 2022B model is the latest ocean tide version proposed by Lyard et al. (affiliated with LEGOS, Laboratoire d’Etudes en Geophysique et Oceanographie Spatiale). Benefiting from more background model data and advanced processing methods, FES 2022B offers significant improvements in resolution and accuracy over its predecessor (FES 2014B) [21].

Jason-3’s GDR-G data has been released for only a few months [22], and there is little published research on the evaluation of this dataset. To fully exploit the dataset’s potential, it is necessary to understand its key characteristics—such as potential biases and precision when different correction models are adopted. This study therefore conducts an in-depth analysis of the data, focusing on SSHA under different retrackers and correction models. Additionally, it analyzes Significant Wave Height (SWH), backscattering coefficient (Sigma-0), and Wind Speed (WS), uncovering several notable features.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

The release of Jason-3 GDR-G coincided with the maneuver of the Jason-3 satellite to form a tandem configuration with the Sentinel-6A satellite. In the first half of Cycle #400, the satellite orbit was maneuvered to enter the second tandem phase with Sentinel-6A, and cycle labels were reassigned (beginning with #500) in this new phase. Thus, Cycle #501 is the first cycle with complete GDR-G data products. As of July 2025, only six cycles of GDR-G (Cycles #501–#506) have been disseminated, and these served as the primary data source for this study. As a counterpart to GDR-G, the last six cycles of GDR-F (Cycles #394–#399) were also collected for comparative analysis. In total, twelve cycles of Jason GDR data were analyzed. To ensure optimal precision, only non-time-critical GDR products were used, rather than Operational GDR (OGDR) or Interim GDR (IGDR) products.

As shown in Section 4.1.1, relative biases exist between the average SSHA of Jason-3 GDR-F and GDR-G. To further investigate these biases, some Sentinel-6A data were also analyzed.

Like Jason-3, Sentinel-6A also underwent a data product update, but this update was not synchronized with that of Jason-3. Starting from Pass #21 of Cycle #160, the GDR products of the Sentinel-6A altimeter were upgraded to Version G. Therefore, comparative analyses of data before and after this cycle must be conducted separately. To increase the sample size of data where both satellites used Version G products, besides the above 12 cycles, we added data from three additional cycles (Cycles #507–#509 of Jason-3 and Cycles #162–#164 of Sentinel-6A) to the analysis. The data from these three additional cycles were only used in Section 5.1.

As previously mentioned, the Sentinel-6A radar altimeter operates in two modes: the traditional pulse-limited mode and the high-resolution SAR mode, corresponding to Low-Resolution (LR) and High-Resolution (HR) products, respectively [23]. Since Jason-3 operates only in pulse-limited mode, we selected Sentinel-6A’s LR products for comparative analysis to avoid introducing additional errors.

The date, mission, cycle number and the corresponding processing standards of the data used in this study were tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Date, Mission, Cycle number and the corresponding processing standards of the data used in this study.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Computation of SSHA

The primary objective of an altimetry mission is to measure Sea Surface Height (SSH) and Sea Surface Height Anomaly (SSHA). SSH refers to the height of the sea surface above the reference ellipsoid and can be calculated as follows:

where H is the orbital height, R is the range from the satellite to the sea surface (measured from the radar altimeter, including all instrumental corrections), , and are the three components of the atmospheric path delay correction (dry tropospheric delay, wet tropospheric delay and ionospheric delay, respectively), and is the sea state bias (SSB) correction.

SSHA is defined here as the SSH minus the mean sea surface and minus known geophysical effects [8]:

where MSS is the Mean Sea Surface, is the geocentric ocean tide height (including ocean load tide height), is the solid earth tide height, is the pole tide height, (based on the work of Zaron [24], and introduced in GDR-F), is the non-equilibrium long period tide height, is the dynamic atmospheric correction (the summation of inverse barometric correction and high frequency fluctuations correction).

For several correction items, Jason-3 GDR provides two solutions (see Table 3). The solutions used in the computation of the official “ssha” parameters are defined as the “baseline” solutions, while SSHA can also be calculated by replacing any baseline solution with its corresponding secondary solution.

Table 3.

Candidate solutions of several correction items.

SSHAs were calculated (where possible) for every 1 Hz measurement point of the Jason-3 altimeter using eight processing approaches:

- Baseline (MLE4): directly extracted from the data products (all the corrections was same to the “baseline solution” column of Table 2).

- 3D SSB (MLE4): same to the “Baseline” processing approach, except that the 2D (two dimensions, SWH + WS) sea state bias correction was replaced by its 3D (three dimensions, SWH + WS + mean wave period) counterpart.

- Model wet tropospheric (MLE4): same to the “Baseline” processing approach, except that the microwave radiometer-derived wet tropospheric delay correction was replaced by a model (ECMWF) solution.

- GIM ionospheric (MLE4): same to the “Baseline” processing approach, except that the dual-frequency altimeter-derived ionospheric delay correction was replaced by a model (GIM) solution.

- GOT tide (MLE4): same to the “Baseline” processing approach, except that the LEGOS FES model-derived ocean tide height was replaced by another model (NASA GOT) solution.

- DTU MSS (MLE4): same to the “Baseline” processing approach, except that the CNES_CLS (for GDR-F) or Hybrid (for GDR-G) MSS was replaced by another model (DTU) solution.

- Baseline (Adaptive): For GDR-G, directly extracted from the data products (all the corrections was same to the “baseline solution” column of Table 2); for GDR-F, calculated from Equation (2), for there was no “ssha_adaptive” parameter in GDR-F.

- 3D SSB (Adaptive): same to the “Baseline (MLE4)” processing approach, except that the 2D (SWH + WS) sea state bias correction was replaced by its 3D (SWH + WS + mean wave period) counterpart.

Radar altimeter range measurements are derived from retracking radar echo waveforms, so different retrackers can produce different SSHAs. Both GDR-F (MLE4 and MLE3) and GDR-G (MLE4 and Adaptive) provide two baseline SSHAs [8,9,10]. Beyond range, ionospheric path delay and SSB corrections also depend on the retracker. In GDR-G, ionospheric path delay and SSB corrections for the MLE3 retracker are no longer provided, making it impossible to calculate valid SSHA for MLE3. Fortunately, GDR-F includes ionospheric path delay and SSB corrections for the Adaptive retracker [9,10], enabling the calculation of Adaptive-based SSHA for GDR-F using Equations (1) and (2).

After computing the SSHAs, simple data editing was performed. First, the robustness (for an iterative retracker, the robustness can be characterized by the success rate of retracking) of the MLE retracker (with a success rate of only ~70%) is much lower than that of the Adaptive retracker (~90% success rate). Thus, only measurements with both MLE4 and Adaptive SSHAs were included in comparative analysis to eliminate representativeness errors. Second, SSHA measurements with an absolute value exceeding 1 m were rejected as outliers—except in extreme cases (e.g., storm surges or heavy rain), actual SSHA typically ranges within ±0.2 m. For all cycles, over 500,000 valid measurements were included, ensuring statistical significance.

3.2.2. Evaluation of the SSHA Noise Level: The Detrend Method

After deriving multiple SSHAs from the same dataset, a key task is to compare them and quantify the contribution (or degradation) of different correction models.

Several methods exist to evaluate SSHA noise levels. One method relies on the power level of the white-noise region in the power spectrum of SSHA time series. This spectrum is obtained using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), which requires sufficiently long, continuous SSHA time series (interpolation may introduce errors if gaps exist). However, within a two-month period, the number of suitable time series is limited, and the boundary between the linear-decreasing region and white-noise region may be ambiguous. Another common approach is self-cross-calibration between ascending and descending passes, but time lags between passes at crossover points introduce mismatch errors.

This study proposes a “detrend method”, which involves filtering out the trend of SSHA. A moving average was applied to the along-track SSHA series, and the smoothed SSHA was subtracted to obtain the SSHA residual series:

Afterwards, the standard deviation of can serve as a metric of the SSHA noise level. For other approaches, improvement or degradation over the Baseline (MLE4) approach was quantified by the decrease or increase in standard deviation, calculated using the Root Square Summation (RSS) method.

The core logic of this detrend method aligns with the approach based on explained variance percentage. Using a control variable design, different processing approaches were tested—each modifying only one correction term—to evaluate the relative contribution of individual error sources. While numerical results may differ slightly from other methods, the overall trend remains consistent.

A critical consideration for this method is the moving window length. Detrending acts as a high-pass filter: shorter windows result in higher filter cutoffs, which may filter out small-scale or mesoscale components of correction terms. While this reduces the standard deviation of the SSHA residual series, it also makes standard deviations across approaches nearly indistinguishable (e.g., a 21-point moving average barely differentiates SSHA series from the “Baseline” and “model wet” approaches). As a compromise, a 61-point boxcar moving average was used for all processing (equivalent to ~350 km, given the satellite’s ground speed of ~5.8 km/s). Although some actual SSHA signals (e.g., mesoscale eddies) may be aliased into the residual series (which ideally contain only errors), most error signals (e.g., atmospheric path delay, SSB, tides) are retained to facilitate further analysis.

Another key issue is the choice of smoothing window. The classic moving average (rectangular window) is simple to implement but applies a rectangular window in the time domain, with a frequency response expressed as a Sinc function:

A major limitation of the rectangular window is high sidelobes (primary sidelobes reach ~−13 dB), which cause aliasing errors. Kernel functions (e.g., Gaussian, Hamming, Lanczos windows) can be used during smoothing to improve performance [25,26,27,28].

The Hamming window is a cosine-weighted window designed to reduce spectral leakage compared to the rectangular window by tapering edges to zero. It balances main lobe width (frequency resolution) and sidelobe suppression, making it suitable for general signal smoothing.

For an N-point Hamming window (), with n in [0, N − 1], the function is:

The coefficients 0.54 and 0.46 are standard values that minimize side lobe amplitude while maintaining a narrow main lobe. The cosine term tapers the window smoothly from 0.08 (at n = 0 and n = N − 1) to 1.0 (at n = (N − 1)/2). The frequency response decomposes into the sum of three rectangular window responses (shifted by different frequencies):

Here, is the rectangular window frequency response. The additional terms account for the cosine taper, reducing side lobe magnitude (to ~−40 dB) but slightly widening the main lobe compared to the rectangular window of the same size.

The Lanczos window is a Sinc-weighted window optimized for high sidelobe suppression and sharp frequency cutoff, making it ideal for smoothing applications requiring precise frequency separation (e.g., spectral analysis). It uses the product of two Sinc functions to control both main lobe width and sidelobe decay.

For an N-point Lanczos window () with shape parameter α = 2 (a common choice for balanced performance), the window is symmetric around n = 0, with . The function is:

For n = 0, = 1 (by the limit of the sinc function). The parameter α = 2 ensures rapid side lobe decay (~−60 dB per octave) without excessive main lobe widening.

The frequency response is the DTFT of the Lanczos window, which corresponds to the convolution of two rectangular window frequency responses (due to the product of sinc functions in the time domain):

Here, is the rectangular window response, and the convolution narrows the effective main lobe while suppressing side lobes, resulting in a sharper frequency transition than the Hamming window.

Introducing kernel windows broadens the filter’s frequency response: the Hamming window widens it by approximately 30%. To ensure matching cutoff frequencies between the Hamming and rectangular windows, fewer samples are needed. This study uses a 45-point Hamming window (with a cutoff frequency equivalent to a 61-point rectangular window). A 41-point Lanczos window, meanwhile, has a main lobe width nearly identical to that of a 61-point rectangular window (~0.205 rad/sample) while offering superior sidelobe suppression.

Thus, in terms of main lobe width (a key metric for frequency response width), the 61-point rectangular window, 45-point Hamming window, and 41-point Lanczos window are approximately equivalent.

Extensive testing showed that among common kernel functions, the Hamming and Lanczos windows outperform the rectangular window, with the Lanczos window yielding the best results (see Section 5.1 for details).

3.2.3. Candidate Method: SSHA Wavenumber Power Spectrum

Maybe the most popular method to evaluate the altimetry data performance is based on the spectrum approach. The Power Spectrum Density (PSD) of the SSHA can be computed by the periodogram of the SSHA series:

where is the wavenumber (L is the scale in unit of kilometer). The SSHA is a real signal, so the initial spectrum is a double-sideband one. In analyzing the noise level, we only retain the positive part.

The spectrum usually gradually decreases with respect to the wavenumber (more energy in larger scale), until it enters a plateau region. The spectrum in this region is dominated by the white noise (the oceanography signal is relatively weaker and cannot be discernable). The white noise is mostly attributed to the instrumental noise, so the white noise level of SSHA spectrum is an excellent metric to evaluate the altimeter instrumental error (not SSHA error). For the evaluation of the correction terms, the PSD in the 50~500 km scale band can be a qualitative indicator.

We chose ~10% passes that had overwhelming open-ocean measurements and generated the along-track 1 Hz SSHA spectrum. For each pass we extracted two 1024-point SSHA series, and filled the invalid points via spline interpolation. The along-track 1 Hz resolution corresponds to ~6 km in distance, so the spectrum contained oceanography information from large scale (~6000 km) to small scale (~12 km). We got over 300 spectrums of each 1024-point series for both GDR-F and GDR-G in six cycles, which were averaged to alleviate the fluctuations.

3.2.4. Candidate Method: Self-Cross-Calibration

Another standard approach for evaluating different processing approaches is the self-cross-calibration method [29,30]. The methodology is as follows: first, identify and count the crossovers (intersection points) between the ascending and descending orbits of the Jason-3 satellite (no reference satellite is required); second, perform appropriate data editing to select reliable crossovers; finally, calculate the SSHA discrepancies between ascending and descending orbits at these crossovers, and compute the standard deviation of the sequence formed by these discrepancies. Generally, the higher the SSHA measurement quality, the lower the standard deviation of the SSHA discrepancy sequence obtained via self-cross-calibration.

In practice, we conducted a self-cross-calibration-based analysis of various approaches, editing crossovers according to the following criteria:

- Only count the crossovers within the ±50° latitude band, to reduce the impact of polar ice;

- Reject all the measurement points where the water depth exceeds 1000 m to minimize the impact of nearshore areas;

- Ensure that both the rain flags and ice flags are 0 to eliminate ice contamination or rain interference at the crossovers;

- Require that the time interval between ascending and descending orbit observations to not exceed 3 days, so as to reduce the impact of temporal mismatch errors;

- For each ascending or descending orbit forming a crossover, there must be no fewer than 4 consecutive valid measurement points on both sides of the crossover. Since crossover locations rarely coincide with the altimeter’s 1 Hz products, SSHA values at crossovers were derived using the cubic spline interpolation method.

3.2.5. Overall Descriptive Analysis: Histograms and Geographical Distribution

Overall descriptive analysis is a complementary to the quantitative analysis described above. To check the distribution of the SSHA and find potential imperfect features (e.g., non-Gaussian pattern, quantization errors), the histograms of the SSHAs of individual cycles were generated. To make sure that the overall dynamic oceanography features is confirm with the theoretical and empirical predictions, the along-track geographical map of individual cycles were drawn.

3.2.6. The SWH, Sigma-0 and WS Analyzing Method

Significant Wave Height (SWH), backscattering coefficient (Sigma-0), and Wind Speed (WS)—often called “wind-and-wave” products—are critical parameters in dynamic oceanography. More importantly, SSB (a leading error source in SSHA) depends on the accuracy of SWH and WS, making the evaluation of these wind-and-wave products essential.

For the analysis of SWH, Sigma-0, and WS, histograms were generated for each cycle (both before and after outlier editing). Average values derived from the MLE4 and Adaptive retrackers were calculated cycle by cycle to identify relative biases between the two retrackers.

4. Results

4.1. SSHA Results

4.1.1. Average Value

The average SSHA values of six cycles (GDR-F SSHAs were averaged from Cycles #394–#399, and GDR-G SSHAs were averaged from Cycles #501–#506) and their relative biases relative to the baseline (MLE4) product were calculated under the eight approaches, with the results tabulated in Table 4. Once the smoothing window of a measurement intercepted with the coastal boundaries (i.e., any “surface_classification_flag” parameter was nonzero or any “distance_to_coast” parameter in the smoothing window was non-positive), the measurement was rejected. The following features were observed:

Table 4.

SSHA mean values and relative biases to the baseline product under the eight approaches (Unit: centimeters; GDR-F SSHAs were averaged from Cycles #394–#399, and GDR-G SSHAs were averaging from Cycles #501–#506).

- The global average SSHA of GDR-G was slightly lower (by ~4 mm) than that of GDR-F. Given the ~3-month time lag between the two datasets, we cannot rule out potential seasonal variations (i.e., true changes in global average sea level) or geographic sampling differences in the SSHA signal. A further investigation of this bias is provided in Section 5.3.

- Discrepancies of more than 4 cm were observed between the highest value (from the “MLE4 + 3D SSB” processing approach) and the lowest value (from the “Baseline (Adaptive)” processing approach). Thus, it is crucial to specify the relevant retracker and correction sources [10] (e.g., replacing wet tropospheric or ionospheric path delay corrections with model-derived solutions near coasts may cause discontinuities). Furthermore, in calibration/validation activities, it is insufficient to only calibrate the “ssha” parameter in GDR products (the baseline SSHA for the MLE4 retracker).

- The Adaptive retracker yielded a lower SSHA (by ~2.5 cm) than the MLE4 retracker. In SSHA computation, range, SSB, and ionospheric path delay all depend on the retracker. Further analysis showed that differences in SSB accounted for ~50% of the total discrepancy, range differences for ~40%, and ionospheric path delay differences for ~10%.

- Among all correction items in raw SSHA computation, two were dominant: SSB and ionospheric path delay. Choosing 3D SSB instead of 2D SSB, or GIM ionospheric path delay instead of dual-frequency ionospheric path delay, resulted in a higher SSHA (by ~1.5 cm).

4.1.2. Noise Level

The standard deviations of SSHA under the eight approaches were calculated cycle by cycle for GDR-F (shown in Table 5) and GDR-G (shown in Table 6), while the improvement or degradation of SSHA relative to the MLE4 baseline SSHA was shown in Table 7.

Table 5.

SSHA standard deviations under different processing approaches (Unit: centimeters, GDR-F, cycle #394–#399, 41-point Lanczos kernel).

Table 6.

SSHA standard deviations under different processing approaches (Unit: centimeters, GDR-G, cycle #501–#506, 41-point Lanczos kernel).

Table 7.

SSHA improvement or degradation over the MEL4 baseline SSHA (Unit: centimeters, Detrend method, 41-point Lanczos kernel).

In Table 7, the baseline SSHA from the Adaptive retracker had a lower standard deviation than the MLE4 baseline SSHA, resulting in an improvement of: for GDR-G, and the noise level was relatively reduced by (4.05 − 3.76)/4.05 = 7.2%, which is comparable to the ~10% value reported by Thibaut et al. (2021) [13].

- As expected, the standard deviations of GDR-G were lower than those of GDR-F for all approaches. This result confirms that GDR-G helps unlock the potential of satellite altimetry.

- The Adaptive retracker significantly outperformed the MLE4 retracker: replacing MLE4 with the Adaptive retracker achieved an improvement of 1.36 cm (for GDR-F) or 1.46 cm (for GDR-G); further replacing 2D SSB with 3D SSB yielded an additional improvement of 1.72 cm (for GDR-F) or 1.79 cm (for GDR-G) relative to the MLE4 baseline.

- Except for 3D SSB, all secondary solutions in Table 2 caused degradation. The most significant degradation came from the MSS model: the DTU model—especially DTU18—performs less well than the CNES_CLS (for GDR-F) or Hybrid (for GDR-G) model in low-to-mid latitudes (Jason-3 does not collect data in polar regions, where DTU models are optimized). This conformed with the results of Laloue et al. (2025), in which the Power Spectrum Density (PSD) of the measured SSHA (i.e., including the MSS error) between 15 and 100 km wavelength along Sentinel-3A Tracks using five MSS models were compared, finding that the MSS error of Hybrid23 MSS was only half of the MSS error of CNES_CLS-2015 MSS [17]. The LEGOS FES ocean tide model outperformed its NASA GOT counterpart by ~0.6 cm (as expected, since FES includes more tidal constituents and has higher resolution [21]). The wet tropospheric path delay derived from the Advanced Microwave Radiometer (AMR) outperformed the model-based solution by ~0.5 cm, and the ionospheric path delay derived from dual-frequency altimetry outperformed the model-based solution by ~0.2 cm—both results confirm the value of on-board measurements.

4.1.3. Histograms of SSHA

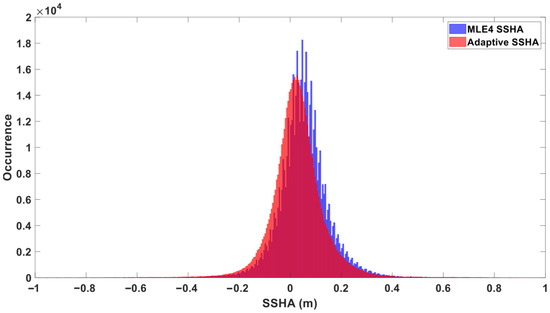

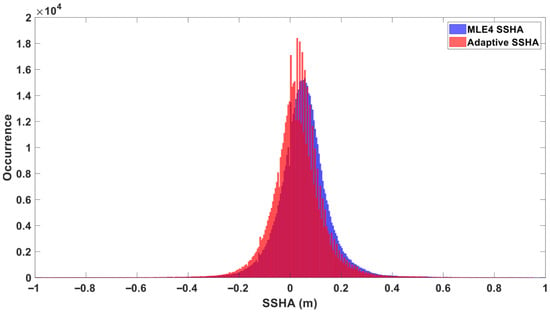

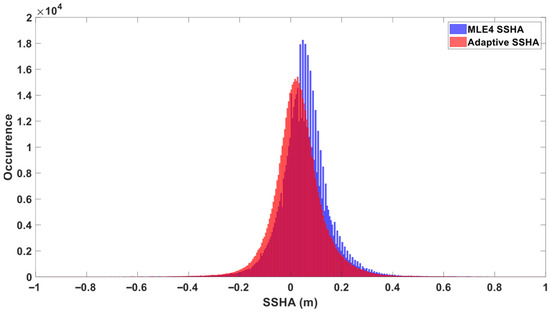

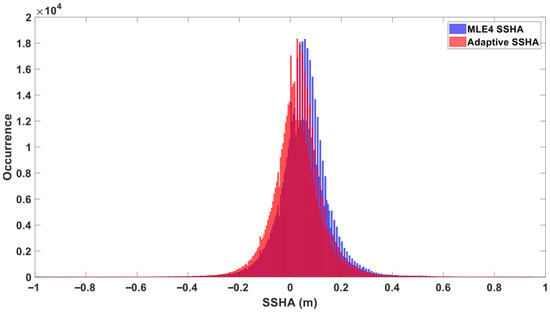

The histograms of SSHA measurements for GDR-F (Cycle #399) and GDR-G (Cycle #501) are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. Before data editing, the SSHA histograms of the MLE4 Baseline contained more irregularly distributed samples than those of the Adaptive Baseline. After data editing, both distributions tended to follow a Gaussian distribution and were consistent with AVISO’s published data (https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/calval/systematic-calval.html, accessed on 19 November 2025), with the peak of the Adaptive Baseline’s SSHA histogram more to the left (lower average SSHA). The SSHA histogram of the Adaptive Baseline for Cycle #399 was smoother because these SSHAs were recalculated according to Equation (1) and quantized to 0.1 mm, whereas the SSHAs directly provided in the GDR products were quantized to 1 mm, resulting in minor sawtooth features.

Figure 1.

Histogram of SSHA Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive; Data Unedited).

Figure 2.

Histogram of SSHA Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive; Data Unedited).

Figure 3.

Histogram of SSHA Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

Figure 4.

Histogram of SSHA Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

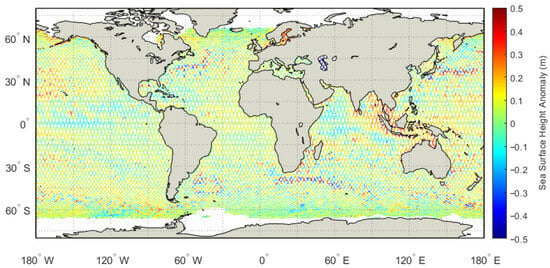

4.1.4. Geographical Distribution of SSHA

Geographical distribution maps of SSHA from the Jason-3 satellite altimeter for Cycles #399 and #501 are presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. Between Cycles #399 and #501, the core latitudinal pattern of SSHA remains consistent. The Rhines scale and Rossby radius of deformation are key length scales for oceanic mesoscale dynamics inferable from global SSHA maps [31,32,33,34]. Both scales exhibit strong latitudinal variability—200–300 km and 200–250 km in low latitudes, 50–100 km and 100–130 km in mid-latitudes, <50 km and <100 km (beyond SSHA resolution) in high latitudes—with their temporal stability confirmed by consistent SSHA features over a 40-day interval.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of Jason-3 satellite altimeter SSHA (Cycle #399, GDR-F).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of Jason-3 satellite altimeter SSHA (Cycle #501, GDR-G).

4.2. SWH, Sigma-0 and WS Results

4.2.1. Relative Biases Between MLE4 and Adaptive Retrackers

To analyze SWH, Sigma-0, and WS, we edited the data. The following editing criteria were applied to the analysis:

- Only measurement points with valid data from both the MLE4 retracker and Adaptive retracker were included in the statistics;

- The surface class was restricted to open ocean (where the parameter “surface_classification_flag” equals 0) to exclude coastal waters, inland water bodies, or ice-covered surfaces;

- The waveform class was Brownian, corresponding to the echo classification flag marked as 1 in the “wvf_main_class” parameter of Sensor Geophysical Data Record (SGDR) data;

- Both the “ice_flag” and “rain_flag” were set to 0 (to eliminate ice contamination or rain interference at the measurement point).

No upper or lower bounds were imposed on the numerical values of SWH and WS during screening. In fact, the above criteria are sufficient to eliminate most outliers of SWH and WS.

The relative biases of SWH, Sigma-0, and WS between the MLE4 and Adaptive retrackers were tabulated cycle by cycle in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10, respectively. For SWH and WS, concurrent SWH values from Sentinel-6A were also calculated for comparison.

Table 8.

Comparison of MLE4 SWH and Adaptive SWH.

Table 9.

Comparison of MLE4 Sigma-0 and Adaptive Sigma-0.

Table 10.

Comparison of MLE4 WS and Adaptive WS.

- Cycle #395 exhibited different relative biases in SWH, Sigma-0, and WS compared to all other cycles, likely due to residual outliers after editing. Thus, this cycle was excluded from further analysis.

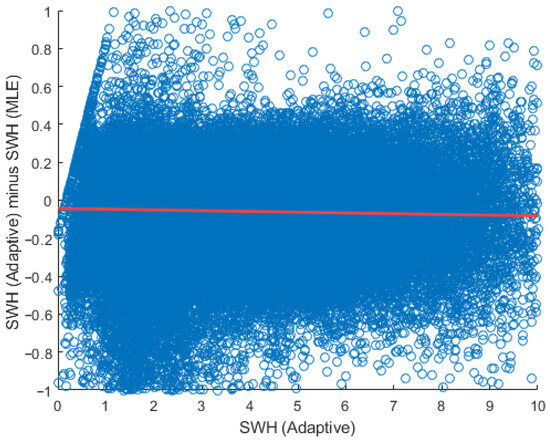

- The cycle-averaged SWH from the Adaptive retracker was slightly lower (by ~0.06 m) than that from the MLE4 retracker for both GDR-F and GDR-G. The difference between SWH from Jason-3 MLE4 and Sentinel-6A MLE4 was negligible. We performed a linear regression analysis between the SWH from the Adaptive retracker (generally more precise than MLE4 SWH) and the SWH difference (Adaptive SWH minus MLE4 SWH). A slight trend was identified, as shown in Figure 7:

Figure 7. Linear regression analysis between the Adaptive SWH and the SWH difference (Adaptive SWH minus MLE4 SWH) for Cycle #501. The blue circles were the pairs of the Adaptive SWH and the SWH difference. The thick red line illustrated the trend (Slope = −0.00396, Offset = −0.043).

Figure 7. Linear regression analysis between the Adaptive SWH and the SWH difference (Adaptive SWH minus MLE4 SWH) for Cycle #501. The blue circles were the pairs of the Adaptive SWH and the SWH difference. The thick red line illustrated the trend (Slope = −0.00396, Offset = −0.043). - The cycle-averaged Sigma-0 from the Adaptive retracker was consistently lower than that from the MLE4 retracker, and the relative bias between the two Sigma-0 values was relatively stable.

- The relative bias between WS from the Adaptive retracker and MLE4 retracker was negligible in most cycles, but the difference between WS from Jason-3 MLE4 and Sentinel-6A MLE4 was significant. Due to space constraints, we do not elaborate further here. One intriguing feature worth noting is that in Cycles #501–#504, a large bias (~−0.2 m/s) coincided with the period when Jason-3 used GDR-G data, while Sentinel-6A still used GDR-F data.

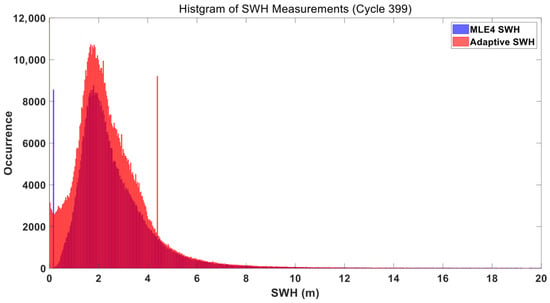

4.2.2. Histograms of SWH and WS

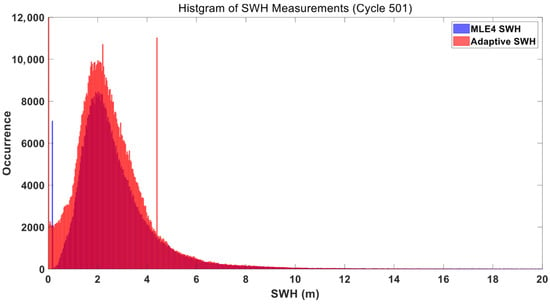

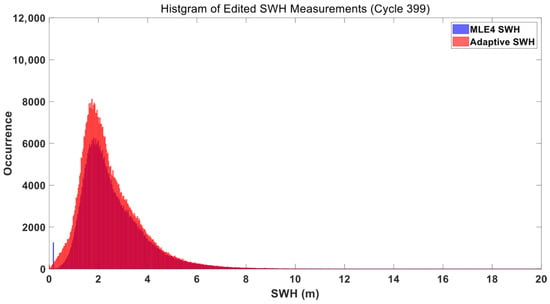

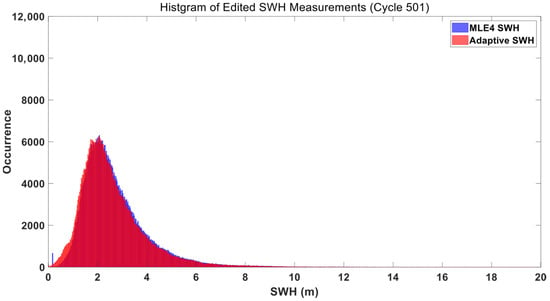

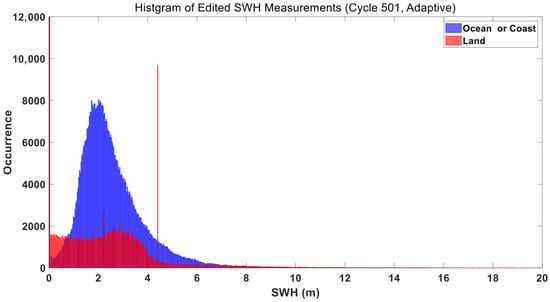

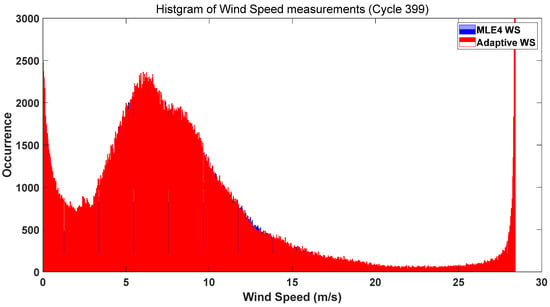

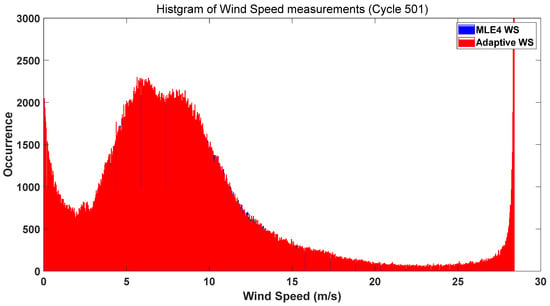

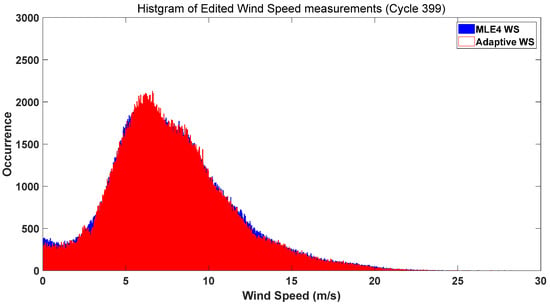

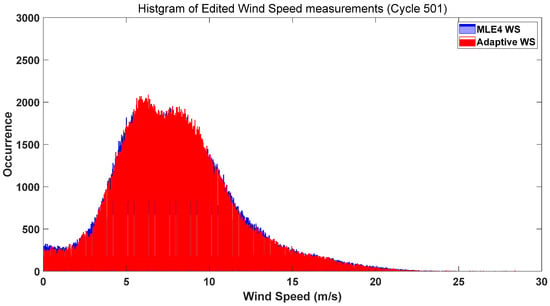

The histograms of SWH and WS measurements for GDR-F (Cycle #399) and GDR-G (Cycle #501) were shown in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, respectively. Histograms of Sigma-0 are not presented here, as few outliers were observed. As mentioned earlier, the Adaptive retracker was much more robust than the MLE4 retracker.

Figure 8.

Histogram of SWH Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Unedited).

Figure 9.

Histogram of SWH Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Unedited).

Figure 10.

Histogram of SWH Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

Figure 11.

Histogram of SWH Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

Figure 12.

Histogram of SWH Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: Ocean or Coast, Red: Land).

Figure 13.

Histogram of WS Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Unedited).

Figure 14.

Histogram of WS Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Unedited).

Figure 15.

Histogram of WS Distribution for Cycle #399 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

Figure 16.

Histogram of WS Distribution for Cycle #501 (Blue: MLE4, Red: Adaptive Method; Data Edited, Open Ocean Data Retained).

In unedited data (Figure 8 and Figure 9), MLE4 produced uneven frequency peaks and broader tails. Its fixed bin width fails to separate noise from the dominant open ocean SWH signal, leading to a muddled distribution. In contrast, the Adaptive SWH histogram smoothed these irregularities and clearly isolates the primary SWH range (2–4 m) by aligning bin widths with natural data clustering. Notably, a large number of outliers from the Adaptive retracker had the same SWH value (4.29 m), which may be a default value in the Adaptive retracker. In edited data (Figure 10 and Figure 11), the SWH distribution concentrated in the 1–5 m range (typical of open ocean waves) with fewer extreme values. The Adaptive SWH histogram retained a smooth, symmetric curve with a sharp peak in the 2–3 m range (the most common open ocean SWH), while MLE4 still showed subtle inconsistencies in the lower (0–1 m) and higher (5–7 m) ranges.

Figure 12 further clarified that land regions (red) exhibited negligible SWH values (mostly 0–1 m), while ocean/nearshore regions (blue) showed a distribution consistent with open ocean conditions (1–5 m). This confirmed that data editing (removing land data) is essential for accurate SWH analysis—and the Adaptive method was better equipped to capture this distinction.

Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 confirmed the superiority of the Adaptive method over MLE4 and the importance of data editing for WS analysis. In unedited data (Figure 13 and Figure 14), MLE4 exhibited jagged distributions with extended tails (e.g., WS > 16 m/s). These tails corresponded to spurious high wind speeds caused by land/coastal interference or transient meteorological noise, which MLE4’s fixed bin width failed to filter. The Adaptive method smoothed these artifacts and clearly defined the primary WS range (5–12 m/s) by focusing on data-dense regions. In edited data (Figure 15 and Figure 16), data editing retained only open ocean wind data, narrowing the distribution to the 4–14 m/s range (consistent with typical open ocean conditions). The Adaptive method produced a smooth, symmetric curve with a distinct peak in the 8–10 m/s range (the modal open ocean WS), while MLE4 still showed unevenness in the upper range (12–16 m/s). Across both cycles, the Adaptive method consistently delivered more accurate and interpretable open ocean WS distributions, making it ideal for studies of wind-driven ocean dynamics.

4.2.3. Geographical Distribution of SWH and WS

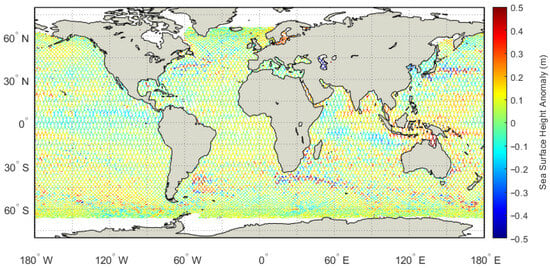

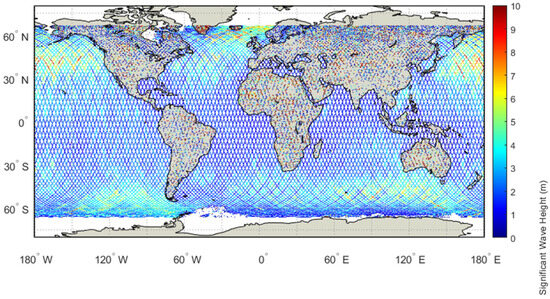

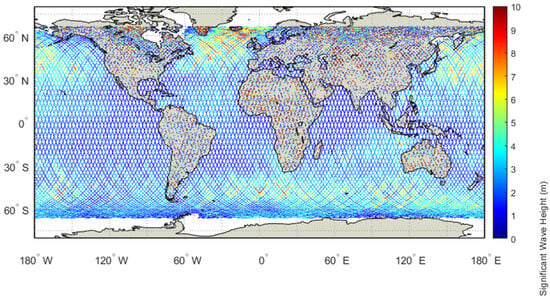

Figure 17 and Figure 18 displayed the global SWH distributions for Jason-3 Cycles #399 and #501. Between Cycles #399 and #501, the core latitudinal pattern of SWH remained consistent.

Figure 17.

Geographical distribution map of SWH from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #399, GDR-F).

Figure 18.

Geographical distribution map of SWH from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #501, GDR-G).

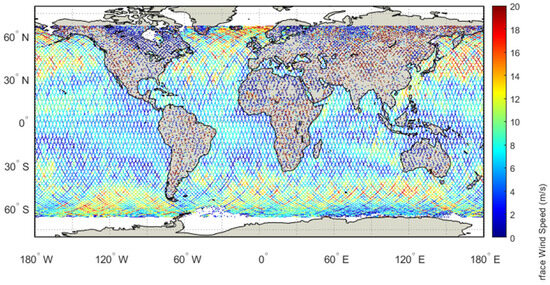

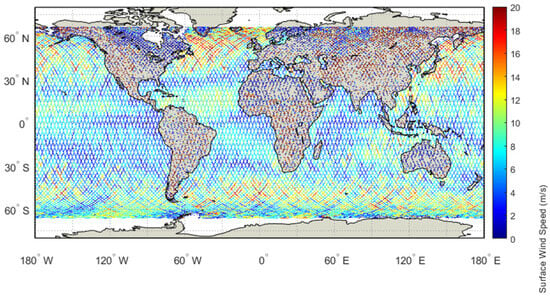

The geographical WS distributions were shown in Figure 19 and Figure 20 (Jason-3 Cycles #399 and #501). The spatial pattern aligned closely with global wind systems.

Figure 19.

Geographical distribution map of WS from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #399, GDR-F).

Figure 20.

Geographical distribution map of WS from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #501, GDR-G).

5. Discussion

5.1. On the Selection of SSHA Smoothing Methods

In the detrending method, we applied different filtering methods to smooth the 1 Hz SSHA sequence. As mentioned in Section 3.2.2, a 41-point Lanczos kernel smoothing method was adopted, which is roughly equivalent to a 61-point rectangular window or a 45-point Hamming kernel window. Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 presented the results obtained using the rectangular window, while Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16 presented those obtained using the Hamming kernel.

Table 11.

SSHA standard deviations under different processing approaches (Unit: centimeters, GDR-F, cycle #394–#399, 61-point rectangle window).

Table 12.

SSHA standard deviations under different processing approaches (Unit: centimeters, GDR-G, cycle #501–#506, 61-point rectangle window).

Table 13.

SSHA improvement or degradation over the MEL4 baseline SSHA (Unit: centimeters, Detrend method, 61-point rectangle window).

Table 14.

SSHA standard deviations under different approach (Unit: centimeters, GDR-F, cycle #394–#399, 45-point Hamming window).

Table 15.

SSHA standard deviations under different approach (Unit: centimeters, GDR-G, cycle #501–#506, 45-point Hamming window).

Table 16.

SSHA improvement or degradation over the MEL4 baseline SSHA (Unit: centimeters, Detrend method, 45-point Hamming window).

As observed from the tables above, the relative performance of the eight configurations was consistent across the rectangular window, Hamming window, and Lanczos window. Thus, the windowing method did not affect the evaluation of the relative superiority of different configurations. The Lanczos window exhibited the lowest sidelobes, resulting in the smallest standard deviations for all parameters.

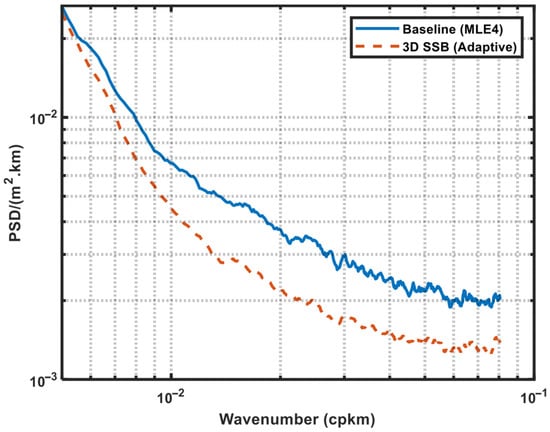

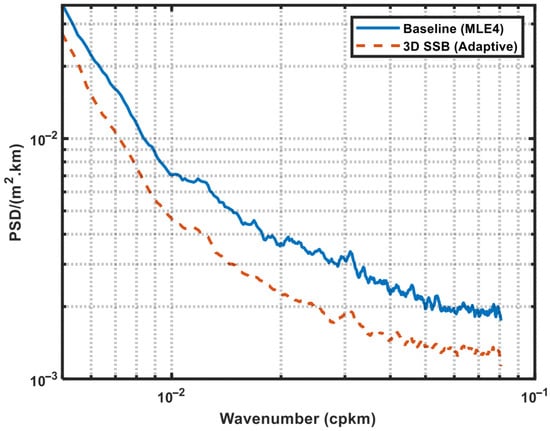

5.2. SSHA Spectrum Results

The range noise levels estimated from the noise region of the SSHA spectrum (Unit: centimeters were tabulated in Table 17. It can be seen that the 1 Hz range noise level varied between 1.4–1.8 cm. Most error correction terms had little effect on the ranging noise level because the scales of these errors were usually larger than the region used for noise level calculation (The observed fluctuation of ±0.02 cm was mainly due to the insufficient number of cycles involved in the power spectrum calculation); the 3D Sea State Bias (SSB) made a substantial contribution to reducing SSHA noise, presumably because part of the SSB consists of residual retracking errors, and better correction of SSB can reduce such retracking errors. The Adaptive retracker had a more significant contribution to reducing the ranging noise level than the 3D SSB, while the combination of the Adaptive retracker and 2D SSB performed the best as expected.

Table 17.

Range noise levels estimated from the noise region of the SSHA spectrum (Unit: centimeters).

5.3. SSHA Self-Cross-Calibration Results

Thousands of valid crossovers were obtained for each cycle. For each crossover, the discrepancy between ascending and descending orbits was calculated; outliers were then removed using the 3σ (three-times standard deviation) criterion to form a discrepancy sequence, from which the mean and standard deviation were computed. For all cycles, the absolute value of the mean of the discrepancy sequence was within 1 mm, and the standard deviations are presented in Table 18.

Table 18.

Summary of Standard Deviations of SSHA Discrepancy Sequences from Jason-3 Altimeter Self-Cross-Calibration (Unit: centimeters, Cycles #501–#506).

The SSHA spectrums from Jason-3 satellite altimeter were shown in Figure 21 (Cycle #394–#399, GDR-F) and Figure 22 (Cycle #501–#506, GDR-G). The curves of both Baseline (MLE4) SSHA, and 3D SSB (Adaptive) SSHA (the most precise processing approach) were shown. It can be shown that the 3D SSB (Adaptive) approach outperforms the Baseline (MLE4) approach in both mesoscale and small scale.

Figure 21.

SSHA spectrums from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #394–#399, GDR-F). The blue curve was for the Baseline (MLE4) SSHA, and the red curve was for the most precise 3D SSB (Adaptive) SSHA.

Figure 22.

SSHA spectrums from Jason-3 satellite altimeter (Cycle #501–#506, GDR-G). The blue curve was for the Baseline (MLE4) SSHA, and the red curve was for the most precise 3D SSB (Adaptive) SSHA.

As shown in Table 18, the characteristics obtained via self-cross-calibration were generally consistent with those from the detrending method (e.g., the “Adaptive + 3D SSB” configuration performs best among all approaches). However, the differences between configurations with different error correction terms were less pronounced than in the detrending method, and occasional deviations from the overall pattern can be observed (e.g., no significant difference in standard deviation between “Baseline (MLE4)” and “Baseline (Adaptive)”, and in some cycles, “Baseline (MLE4)” even exhibited a smaller standard deviation). This is mainly because the self-cross-calibration method used fewer samples than the detrending method, and the time lag between ascending and descending orbits may introduce temporal sampling mismatch errors. Additionally, SSHA values at crossovers in self-cross-calibration were smoothed via spline interpolation, which may diminish the Adaptive retracker’s advantage in reducing high-frequency noise. Considering that the time complexity of self-cross-calibration is much higher than that of the detrending method proposed in this study, the detrending method was adopted as the primary product evaluation method, with self-cross-calibration serving as a supplement.

5.4. Explanation of SSHA Biases Between Different Versions

To further investigate potential SSHA jumps caused by the version update of Jason-3 satellite data products, this study analyzed concurrent observation data from the Sentinel-6A satellite.

The LR products of Sentinel-6A include three retrackers: MLE4, MLE3, and Numerical Retracking (NR). Similar to Jason-3, MLE3 was no longer supported in GDR-G data. It should be noted that NR is not the counterpart of Jason-3’s Adaptive retracker: it is an improved version of MLE4 and still uses the Hayne model as the baseline for fitting [35,36]. Therefore, only SSHA values derived from the MLE4 retracker in Sentinel-6A’s LR products were analyzed.

The data were divided into three groups:

- Group 1: Jason-3 Cycles #394–#399 (corresponding to Sentinel-6A Cycles 147–152), consisting of six complete cycles. In this group, the two satellites had different ground track sampling patterns but used the same version of data products.

- Group 2: Jason-3 Cycles #501–#504 (corresponding to Sentinel-6A Cycles #156–159), consisting of four complete cycles. In this group, the two satellites had the same ground track sampling pattern but used different data product versions (Jason-3 used Version G, while Sentinel-6A used Version F).

- Group 3: Jason-3 Cycles #505–#509 (corresponding to Sentinel-6A Cycles #160–#164), consisting of four complete cycles and one nearly complete cycle. Starting from Pass #21 of Jason-3 Cycle #505 and Sentinel-6A Cycle #160, Sentinel-6A’s GDR products were upgraded to Version G; thus, all data from the first 20 passes of Jason-3 Cycle #505 and Sentinel-6A Cycle #160 were excluded. A single cycle contains 254 passes, so over 90% of the passes were retained.

The cycle-by-cycle baseline MLE4 SSHA results for Jason-3 and Sentinel-6A were tabulated in Table 19. Within each group, the relative SSHA biases between the two satellites were roughly consistent; however, significant jumps can be observed between groups. In Group 1, the average SSHA of Jason-3 was approximately 1.19 cm lower than that of Sentinel-6A; in Group 2, the average SSHA of Jason-3 was approximately 0.69 cm lower than that of Sentinel-6A; and in Group 3, the average SSHA of Jason-3 was approximately 0.43 cm higher than that of Sentinel-6A.

Table 19.

Cycle-by-cycle baseline MLE4 SSHA results for Jason-3 and Sentinel-6A.

Between Group 1 and Group 2, the SSHA of Jason-3 decreased by only 0.19 cm, while the SSHA of Sentinel-6A decreased by 0.69 cm. Since Sentinel-6A’s ground tracks and data products remained unchanged during this period, we used Sentinel-6A’s observations as a reference (i.e., the true global average sea level decreased by 0.69 cm during this period), indicating that Jason-3’s SSHA in Group 2 was elevated by 0.5 cm. This value results from the combined effects of ground track sampling differences and Jason-3’s data product version update. If we assume that geographic sampling differences are negligible in the calculation of global average sea level (a somewhat arbitrary assumption), Jason-3’s SSHA measurements exhibited a downward jump of approximately 5 mm due to the GDR product version update.

Between Group 2 and Group 3, Jason-3’s data version remained unchanged; the only difference was Sentinel-6A’s data update. This update caused a downward jump of approximately 1 cm in Sentinel-6A’s SSHA measurements.

Admittedly, this study cannot draw definitive conclusions regarding the relative bias of Jason-3 after its data version update, primarily because Jason-3’s data version update coincided with a satellite orbit maneuver. However, the assertion that Sentinel-6A’s GDR product update caused an SSHA jump is relatively reliable. This highlights the possibility of jumps in satellite data after version updates; thus, it is necessary to promptly perform calibration and timely reprocessing based on calibration sites following updates to altimeter satellite data.

6. Conclusions

In this study, SSHAs under eight approaches were calculated using data from the final cycles (Cycles #394–#399) of the Jason-3 altimeter’s GDR-F products and Cycles #501–#506 of its GDR-G products. The relative bias and noise level of SSHA were evaluated, with a focus on quantitatively investigating the contribution of selecting different error correction approaches. It was found that the noise level of GDR-G SSHA has been significantly reduced compared with that of GDR-F; there was a relative bias of up to ~4 cm in SSHA when different waveform retrackers or error correction approaches were selected, and among all error correction approaches, Adaptive retracking combined with 3D SSB achieved the best accuracy. Therefore, we recommend that the “3D SSB (Adaptive)” processing approach be adopted as the baseline for SSHA calculation in the future, and an offset should possibly be added to align with the global Mean Sea Surface (MSS) at a reference epoch (e.g., the classic 1993–2012 time period), considering that the global MSS is increasing over time.

This study also compared the Significant Wave Height (SWH), backscattering coefficient (Sigma-0), and Wind Speed (WS) retrieved using the MLE4 and Adaptive retrackers. It was shown that the SWH histograms of the Adaptive retracker contained a large number of outliers around 0 m and 4 m, while its WS histograms had a large number of outliers slightly above 28 m/s. The corresponding measurements of the MLE4 retracker at these points were usually invalid. Furthermore, these outliers almost all corresponded to non-Brownian waveform shapes (distributed in coastal waters, inland waters, sea ice, and other areas). Therefore, improving the Adaptive retracker or developing a new waveform retracker can further enhance the observational performance of the Jason-3 satellite. The relative biases between the two retrackers are presented in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, which show that the Adaptive retracker usually led to slightly lower SWH, slightly lower Sigma-0, and almost the same WS. Thus, if the wind-and-wave parameters from the Adaptive retracker are to be assimilated into operational models, additional calibration activities should be conducted.

By late June 2025, only six complete cycles (covering ~2 months) of Jason-3 GDR-G had been disseminated, and no cycle containing both GDR-F and GDR-G products could be identified. In fact, in June 2025, the orbit of the Jason-3 satellite was maneuvered to the Long Repeat Orbit (LRO) phase relabeled starting from Cycle #600 (https://www.ospo.noaa.gov/data/messages/2025/06/MSG_20250602_1344.html, accessed on 19 November 2025), leaving only twelve complete cycles in the entire second tandem phase. As mentioned in [8], AVISO+ plans to produce GDR-G for earlier cycles in 2026. After a sufficient number of GDR-F and GDR-G products that cover the same measurement points simultaneously are collected, representative errors will be eliminated, and the relative biases between GDR-F and GDR-G, as well as among different SSHA calculation approaches, will be determined more accurately.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-Y.X.; methodology, X.-Y.X. and Q.L.; software, X.-Y.X. and M.L.; validation, T.S.; formal analysis, X.-Y.X.; investigation, X.-Y.X.; resources, X.-Y.X. and Z.H.; data curation, T.S. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and Q.L.; visualization, X.-Y.X. and M.L.; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, X.-Y.X.; funding acquisition, X.-Y.X. and Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China’s HY-2E/F Satellite Radar Altimeter Mission (Grant Number: E41Z200101; funder: National Satellite Ocean Application Service of China) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number. 41876209).

Data Availability Statement

The official satellite Jason-3 GDR-F and GDR-G data used in this article are available at aviso-data-center.cnes.fr/user/ssalto/modules/1859 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank AVISO+ for archiving and distributing the Jason-3 satellite altimeter data, and EUMETSAT for archiving and distributing the Sentinel-6A satellite altimeter data. Special acknowledgement should be dedicated to Ke Xu, who provided many insightful advices in the procedure of revising the manuscript. We would like also to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their painstaking revision which helped to improve the final quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Advanced Microwave Radiometer |

| AVISO | Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic data |

| CLS | Collecte Localisation Satellites |

| CNES | CNES Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales |

| DTU | Danmarks Tekniske Universitet |

| ECMWF | European Center for Medium range Weather Forecasting |

| FES | Finite Element Solution |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| GDR | Geophysical Data Records |

| GIM | Global Ionosphere Maps |

| GOT | Global Ocean Tide |

| HR | High Resolution |

| LEGOS | Laboratoire d’Etudes en Geophysique et Oceanographie Spatiale |

| LR | Low Resolution |

| LRM | Low Resolution Mode |

| MLE3 | Maximum Likelihood Estimator (3 parameters) |

| MLE4 | Maximum Likelihood Estimator (4 parameters) |

| MSS | Mean Sea Surface |

| MQE | Mean Quadratic Error |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| PSD | Power Spectrum Density |

| PTR | Point Target Response |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error |

| RSS | Root Square Summation |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SGDR | Sensor Geophysical Data Records |

| SIO | Scripps Institute of Oceanography |

| SLA | Sea Level Anomaly |

| SSB | Sea State Bias |

| SSH | Sea Surface Height |

| SSHA | Sea Surface Height Anomaly |

| SWH | Significant Wave Height |

| WS | Wind Speed |

References

- Stammer, D.; Cazenave, A. (Eds.) Satellite Altimetry over Oceans and Land Surfaces; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ablain, M.; Cazenave, A.; Larnicol, G.; Balmaseda, M.; Cipollini, P.; Faugère, Y.; Fernandes, M.J.; Henry, O.; Johannessen, J.A.; Knudsen, P.; et al. Improved sea level record over the satellite altimetry era (1993–2010) from the Climate Change Initiative project. Ocean Sci. 2015, 11, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablain, M.; Cazenave, A.; Valladeau, G.; Guinehut, S. A new assessment of the error budget of global mean sea level rate estimated by satellite altimetry over 1993–2008. Ocean. Sci. 2021, 5, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, C.J.; Cullen, R.; Giulicchi, L.; Vuilleumier, P.; Francis, C.R.; Kuschnerus, M.; Simpson, W.; Bouridah, A.; Caleno, M.; Bertoni, R.; et al. The Copernicus Sentinel-6 mission: Enhanced continuity of satellite sea level measurements from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardo, S.; Maraldi, C.; Daguze, J.A.; Amraoui, S.; Boy, F.; Moreau, T.; Fornari, M.; Cullen, R.; Picot, N. Sentinel-6 MF Poseidon-4 radar altimeter in-flight calibration and performances monitoring. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardo, S.; Maraldi, C.; Cadier, E.; Rieu, P.; Aublanc, J.; Guerou, A.; Boy, F.; Moreau, T.; Picot, N.; Scharroo, R. Sentinel-6 MF poseidon-4 radar altimeter: Main scientific results from S6PP LRM and UF-SAR chains in the first year of the mission. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 73, 337–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablain, M.; Lalau, N.; Meyssignac, B.; Fraudeau, R.; Barnoud, A.; Dibarboure, G.; Egido, A.; Donlon, C. Benefits of a second tandem flight phase between two successive satellite altimetry missions for assessing the instrumental stability. EGU Sphere 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Puig, C.; Bignalet Cazalet, F.; Lucas, B.; Cullen, R.; Desjonqueres, J.D.; Leuliette, E.; Maraldi, C. Definition of the new GDR-G standards in a multi-mission context. In Proceedings of the OSTST 2023, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 7–11 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bignalet-Cazalet, F.; Roinard, H.; Tran, N.; Urien, S.; Picot, N.; Desai, S.; Scharroo, R.; Egido, A.; Bailly-Poirot, F.; Dippenweiler, E.; et al. Jason-3 GDR-F standard: Ready for operational switch. In Proceedings of the OSTST 2020, Venice, Italy, 19–23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AVISO+. Jason-3 Products Handbook Standard F (v2.1). 2021. Available online: https://aviso.altimetry.fr/fileadmin/documents/data/tools/hdbk_j3.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Poisson, J.C.; Quartly, G.D.; Kurekin, A.A.; Thibaut, P.; Hoang, D.; Nencioli, F. Development of an ENVISAT altimetry processor providing sea level continuity between open ocean and arctic leads. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 5299–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourain, C.; Piras, F.; Ollivier, A.D.; Hauser, D.; Poisson, J.C.; Boy, F.; Thibaut, P.; Hermozo, L.; Tison, C. Benefits of the Adaptive algorithm for retracking altimeter nadir echoes: Results from simulations and CFOSAT/SWIM observations. Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9927–9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, P.; Piras, F.; Roinard, H.; Guerou, A.; Boy, F.; Maraldi, C.; Bignalet-Cazalet, F.; Dibarboure, G.; Picot, N. Benefits of the Adaptive Retracking Solution for the JASON-3 GDR-F Reprocessing Campaign. In Proceedings of the IGARSS Proceedings, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 7422–7425. [Google Scholar]

- Amarouche, L.; Thibaut, P.; Zanife, O.Z.; Dumont, J.-P.; Vincent, P.; Steunou, N. Improving the Jason-1 ground retracking to better account for attitude effects. Mar. Geod. 2004, 27, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayne, G.S. Radar altimeter mean return waveforms from near-normal–incidence ocean surface scattering. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1980, 28, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. The average impulse response of a rough surface and its applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1977, 25, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloue, A.; Schaeffer, P.; Pujol, M.I.; Veillard, P.; Andersen, O.; Sandwell, D.; Delepoulle, A.; Dibarboure, G.; Faugère, Y. Merging recent mean sea surface into a 2023 Hybrid model (from Scripps, DTU, CLS, and CNES). Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2024EA003836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.B.; Rose, S.K.; Abulaitijiang, A.; Zhang, S.; Fleury, S. The DTU21 global mean sea surface and first evaluation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4065–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.; Pujol, M.-I.; Veillard, P.; Faugere, Y.; Dagneaux, Q.; Dibarboure, G.; Picot, N. The CNES CLS 2022 Mean sea surface: Short wavelength improvements from CryoSat-2 and SARAL/AltiKa high-sampled altimeter data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwell, D.T. Adding Mean Sea Surface (MSS) as an Altimetry Product; Scripps Institution of Oceanography: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AVISO+ Altimetry. FES2022 (Finite Element Solution) Ocean Tide Product Handbook. 2022. Available online: https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/fileadmin/documents/data/tools/hdbk_FES2022.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Jason-3 GDR-G Change Log. 2025. Available online: https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/fileadmin/documents/data/tools/20250107_GDR-G_Jason-3_Change_Log.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- EUMETSAT. Sentinel-6/Jason-CS ALT Level 2 Product Format Specification (L2 ALT PFS); EUMETSAT: Darmstadt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaron, E.D. Baroclinic tidal sea level from exact-repeat mission altimetry. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2019, 49, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.V.; Schafer, R.W.; Buck, J.R. Digital Signal Processing: Principles, Algorithms, and Applications, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. Experimental Study on Window Effects in Rubidium Atomic Spin Noise Spectrum Analysis. J. Quantum Electron. 2024, 60, 032602. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. Quantitative Comparison of Typical Window Functions for Interference Imaging Spectral Restoration. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 22789–22805. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.J. Lanczos Window Applications in High-Precision Frequency Separation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 31, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Cazenave, A. (Eds.) Satellite Altimetry and Earth Sciences; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G. Global Observations of Ocean Mesoscale Eddies from Satellite Altimetry. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2023, 128, e2022JC018954. [Google Scholar]

- Rhines, P.B. Turbulence and Geostrophic Eddies in the Ocean (Reprint with Commentary). J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2022, 52, 2541–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch, C. The Rossby Radius in Global Ocean Circulation: A Synthesis from Satellite and In Situ Data. Oceanography 2023, 36, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dorandeu, J.; Ablain, M.; Faugère, Y.; Mertz, F.; Soussi, B.; Vincent, P. Jason-1 global statistical evaluation and performance assessment: Calibration and cross-calibration results. Mar. Geod. 2004, 27, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Liu, Q.K.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y. Analysis of the Consistency Between Sentinel-3A & B Altimeters During the Tandem Mission. In Proceedings of the IGARSS Proceedings, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022; pp. 7022–7025. [Google Scholar]

- EUMETSAT. Sentinel-6/Jason-CS ALT Level 2 Product Generation Specification (L2 ALT PGS); EUMETSAT: Darmstadt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buchhaupt, C.; Fenoglio-Marc, L.; Dinardo, S.; Scharroo, R.; Becker, M. A fast convolution-based waveform model for conventional and unfocused SAR altimetry. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 62, 1445–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.