Abstract

Underwater imaging suffers from significant degradation due to scattering by suspended particles, selective absorption by the medium, and depth-dependent noise, leading to issues such as contrast reduction, color distortion, and blurring. Existing enhancement methods typically address only one aspect of these problems, relying on unrealistic assumptions of uniform noise, and fail to jointly handle the spatially heterogeneous noise and spectral channel attenuation. To address these challenges, we propose the variational-based spatial–spectral joint enhancement method (VSJE). This method is based on the physical principles of underwater optical imaging and constructs a depth-aware noise heterogeneity model to accurately capture the differences in noise intensity between near and far regions. Additionally, we propose a channel-sensitive adaptive regularization mechanism based on multidimensional statistics to accommodate the spectral attenuation characteristics of the red, green, and blue channels. A unified variational energy function is then formulated to integrate noise suppression, data fidelity, and color consistency constraints within a collaborative optimization framework, where the depth-aware noise model and channel-sensitive regularization serve as the core adaptive components of the variational formulation. This design enables the joint restoration of multidimensional degradation in underwater images by leveraging the variational framework’s capability to balance multiple enhancement objectives in a mathematically rigorous manner. Experimental results using the UIEBD-VAL dataset demonstrate that VSJE achieves a URanker score of 2.4651 and a UICM score of 9.0740, representing a 30.9% improvement over the state-of-the-art method GDCP in the URanker metric—a key indicator for evaluating the overall visual quality of underwater images. VSJE exhibits superior performance in metrics related to color uniformity (UICM), perceptual quality (CNNIQA, PAQ2PIQ), and overall visual ranking (URanker).

1. Introduction

With the advancement of ocean power strategies, technologies such as marine resource exploration, underwater infrastructure monitoring, and autonomous underwater robot navigation are experiencing rapid development. High-quality underwater visual data is essential for the effective implementation of these technologies [1,2,3]. However, the unique characteristics of the underwater imaging environment lead to multidimensional degradation of raw images, which severely impairs the performance of the entire use case architecture. Specifically, suspended plankton and sediment particles cause significant light scattering, reducing image contrast and generating spatially heterogeneous noise, which increases with scene depth—this noise intensity is exponentially correlated with the distance between the camera and the target. Additionally, water exhibits wavelength-dependent absorption: red light is heavily absorbed over short distances (typically within 1–2 m in coastal waters), followed by green light, while blue light attenuates the least. This phenomenon leads to non-uniform spectral attenuation across the RGB channels, resulting in severe blue-green color casts in deep-water images or red channel loss in turbid coastal waters. The combined effects of scattering and absorption further blur target edges, leading to a loss of fine details (e.g., coral texture, pipeline surface defects) and complicating subsequent visual processing tasks [4,5]. For instance, in AUV navigation scenarios, blurred obstacle edges in raw images may cause navigation systems to misjudge obstacle distances, leading to collision risks; in coral reef monitoring, color distortion may result in misclassification of coral species.

In recent years, underwater image enhancement technology can be divided into two major approaches: physics model-driven methods [6,7] and data-driven methods [8], each with its own advantages and disadvantages, yet both exhibit significant limitations. In the physics model-driven direction, methods represented by Dark Channel Prior (DCP [9]) restore the true scene radiance by estimating scene transmission and ambient light. Their underwater variants, such as Generalization of the Dark Channel Prior for Single Image Restoration (GDCP [10]), adapt to underwater optical characteristics, but in complex lighting or strongly color-cast scenes, transmission estimation can be biased, and they do not account for the depth-dependent nature of noise, leading to imbalanced denoising and color correction effects. In the data-driven direction, deep learning methods like An Underwater Image Enhancement Benchmark Dataset and Beyond (WaterNet [11]) and Underwater Image Enhancement via Medium Transmission-Guided Multi-Color Space Embedding (Ucolor [12]) rely on large-scale paired datasets to learn degradation-to-enhancement mappings and perform well on specific datasets. However, their generalization is limited by the scene distribution of the training data, and the models function as a ’black box’ lacking physical interpretability, often failing in unseen extreme degradation scenarios such as highly turbid water.

Moreover, existing methods generally suffer from the defect of single-dimensional optimization, which is incompatible with the multi-objective requirements of the underwater imaging use case architecture. Specifically, these methods either only address scattering while ignoring the spatial heterogeneity of noise, or use globally fixed regularization parameters that cannot adapt to the spectral attenuation differences among RGB channels. This single-dimensional optimization strategy ultimately leads to the contradictory issue of enhanced images either losing details due to over-denoising or distorting colors due to imbalanced color correction—both outcomes degrade the performance of downstream application tasks. For example, over-denoised images may cause target detection models to miss small objects (e.g., juvenile fish), while color-distorted images may lead to incorrect semantic segmentation of coral reefs.

To overcome the technical bottlenecks mentioned above, this paper proposes a spatial–spectral joint adaptive enhancement method (VSJE) based on a variational framework. Its core lies in combining the physical principles of underwater imaging with the multi-objective balancing capability of variational optimization to achieve synergistic correction of coupled degradations. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Noise Heterogeneity Modeling for Depth Perception: Breaking through the traditional assumption of uniform noise, a spatially varying noise model is constructed based on the exponential attenuation law of underwater light propagation. By combining the improved dark channel prior with the underwater optical equation, unsupervised depth estimation is achieved, providing an accurate physical basis for spatially adaptive denoising.

- Multi-dimensional Statistical Channel Sensitivity Mechanism: Addressing the spectral attenuation differences of the RGB channels, we propose a method to calculate channel sensitivity coefficients by integrating dark channel mean, luminance distribution, and contrast, quantifying the sensitivity of different channels to noise and color bias, and achieving differentiated processing in the spectral dimension.

- Dual Adaptive Regularization and Unified Variational Framework: Design regularization parameters that rely simultaneously on spatial noise intensity and channel sensitivity, and construct a variational energy function integrating spatially adaptive denoising, data fidelity, and color consistency correction. Multi-objective collaborative optimization is achieved through the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), avoiding error accumulation from staged processing.

2. Related Work

Numerous approaches have been proposed to mitigate degradation and improve the visual quality of underwater images. These approaches can be mainly categorized into two major types: (1) Physical model-based methods, which leverage the intrinsic principles of underwater optical imaging to establish mathematical models, thereby guiding the inverse process of image degradation; (2) Non-physical model-based methods, which abandon the reliance on underwater imaging physics and instead enhance image quality by mining statistical distributions, texture structures, or high-level semantic features of the image.

2.1. Physical Model-Based Methods

The core idea of physical model-based methods is to simulate the process of light propagation and interaction with suspended water molecules during underwater imaging and construct a quantitative optical model to describe the mapping relationship between degraded underwater images and clear scenes. By estimating the key parameters in the model, such as atmospheric light, transmission, and attenuation coefficient, these methods can invert the degradation process to recover clear images. Bianco et al. [13] introduced the scene depth prior (MIP), which estimates the depth using the significant differences in light attenuation across the three color channels in the water. Drews et al. [14] designed the underwater dark channel prior (UDCP) based on selective absorption of light by water (excluding the red channel), Peng and Cosman [15] proposed the Image Blurriness and Light Absorption (IBLA) method that relies on image ambiguity and light absorption prior to estimating scene depth and restoring degraded images. Berman et al. [16] suggested the Haze-Line prior to addressing wavelength-dependent attenuation in underwater images. Peng et al. [10] proposed the GDCP method, Song et al. [17] put forward the Enhancement of Underwater Images With Statistical Model of Background Light and Optimization of Transmission Map (SMBL) method, and Song et al. [18] also proposed a quick depth estimation model based on the Underwater Light Attenuation Prior (ULAP), whose coefficients were trained using supervised linear regression with a learning-based approach. However, these simplified models-based methods are easily influenced by water absorption and scattering factors, making it difficult to accurately infer environmental light and transmission in complex scenes.

2.2. Non-Physical Model-Based Methods

Non-physical model-based methods do not rely on the physical principles of underwater optical imaging; instead, they improve image quality at the pixel level by leveraging the statistical features and structural information of images, thereby enhancing contrast, texture and color. This category covers both traditional enhancement methods and deep learning-based methods, each with distinct technical routes and application characteristics. Among traditional methods, Ancuti et al. [19] proposed a fusion approach that combines different feature images into a single image by weight assignment; subsequently, Ancuti et al. [20] advanced this method by developing a multiscale fusion technique that integrates color correction from white balance and contrast enhancement from a histogram method, achieving favorable results for underwater images with significant red channel attenuation. Qi et al. [21] designed the SGUIE-Net framework that utilizes deep semantic attention guidance for enhancement, although its semantic segmentation model performs poorly underwater, leading to inaccurate region division. Zamir et al. [22] have proposed the Restormer method, yet its progressive training scheme demands extensive training time and data. However, these non-physical model-based methods generally analyze and adjust images only in the temporal or spatial domain, neglecting the physical mechanisms underlying underwater image degradation. Traditional methods often suffer from over-enhancement and overexposure due to the lack of consideration for underwater imaging principles, while deep learning methods require large-scale annotated data and substantial computational resources—resources that are challenging to obtain for real clear underwater images. Collectively, their generalization capabilities are insufficient to meet the requirements of complex underwater scenes.

3. The Proposed Method

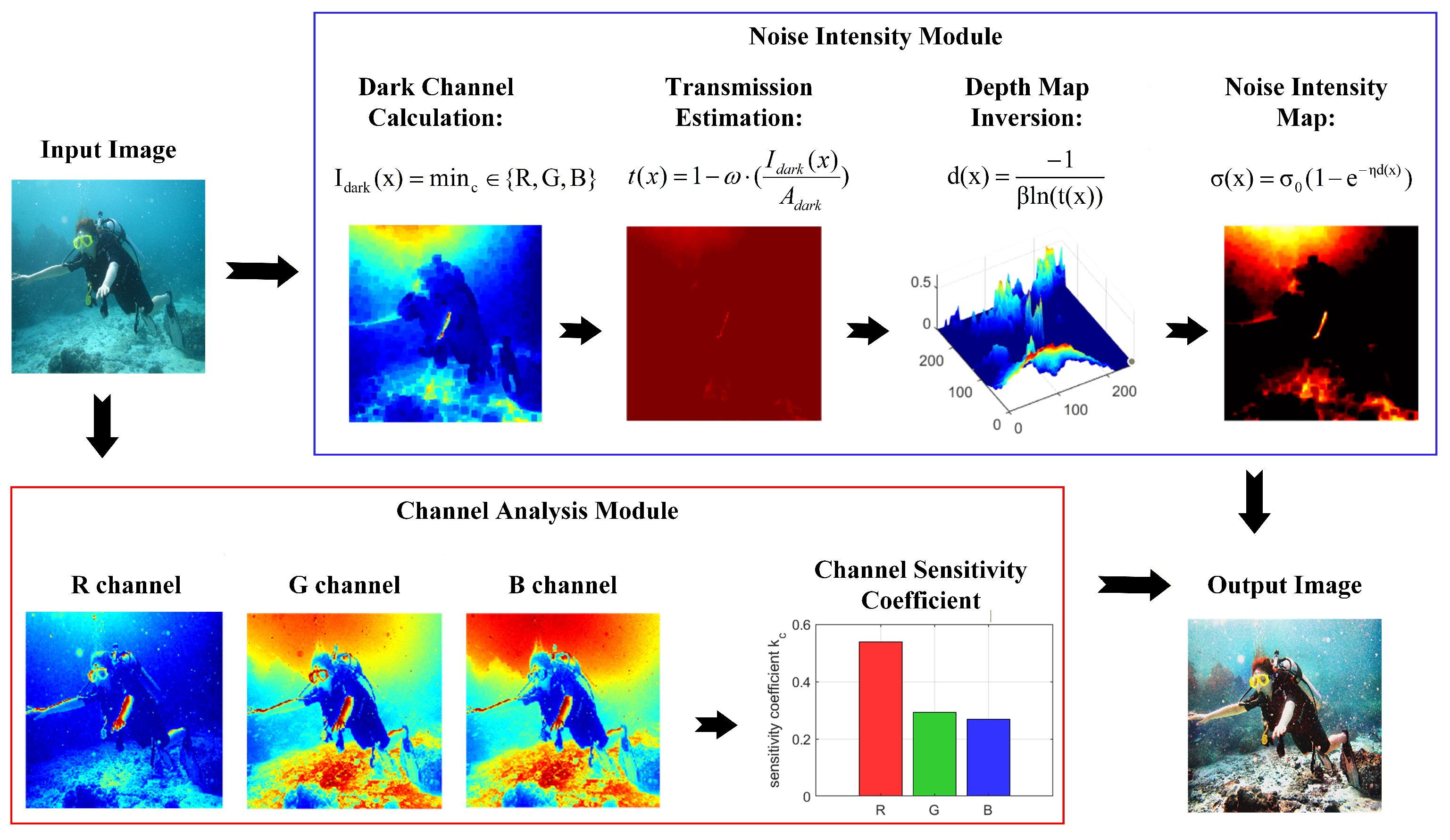

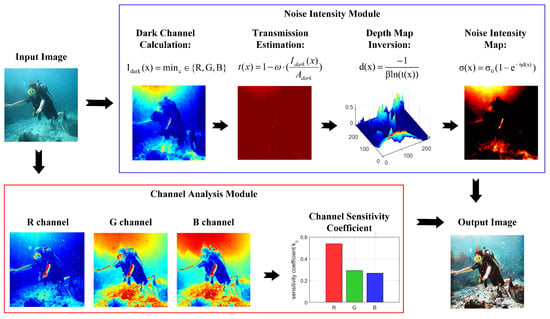

We propose a variational-based underwater image enhancement method that jointly processes spatial and spectral information, aimed at effectively suppressing depth-dependent noise and multi-channel color distortion in degraded scenes such as underwater or hazy environments. This method integrates depth-aware noise modeling with channel-sensitive adaptive regularization to construct a unified variational energy function, enabling the collaborative optimization of image noise and color bias, significantly improving visual quality and scene restoration. The structure of The overall model is shown in Figure 1, with core modules that include noise modeling, depth estimation, channel weight calculation and regularization design.

Figure 1.

Overview of variational-based spatial–spectral joint enhancement method.

3.1. Noise Intensity Modeling

In underwater environments, noise is mainly caused by the scattering of suspended particles in the water, and its intensity increases significantly with the depth of the scene. Traditional homogeneous noise models cannot accurately describe this spatial heterogeneity. To address this issue, we established a depth-related noise model based on the principle of exponential attenuation of light in water. When light propagates underwater, its intensity diminishes due to absorption and scattering, a process described by the transmission .

where is the overall attenuation coefficient of water, the cleanness or clarity of imaging in the water also decreases exponentially with depth. Therefore, we define the model of the noise intensity at pixel x as given by the following equation:

where represents the noise intensity at pixel x of the image, is the maximum noise intensity in the scene, and controls the attenuation rate of noise with depth increase and is set as a preset empirical parameter at 0.15. This value is optimized via cross-validation on the UIEB dataset: we found that 0.15 achieves the best balance between noise suppression in far-view regions and detail preservation in near-view regions. Although both and appear in exponential forms with respect to depth, they characterize fundamentally different degradation processes. Specifically, the coefficient models the physical attenuation of useful signal intensity governed by absorption and scattering during underwater light propagation, whereas controls the statistical accumulation rate of noise induced by multiple scattering, suspended particles, and imaging system amplification. As a result, and are not equivalent and should be treated as independent parameters in the proposed degradation modeling. is the depth map at the corresponding position. Equation (2) is the core of the depth-aware noise modeling module in VSJE, and its implementation is tightly coupled with the transmission estimation and depth inversion steps described below. This model simulates the cumulative effect of noise through an exponential function. When the depth approaches 0 (near-view region), is close to 0, which is consistent with the actual situation of weak noise in near-view areas; when the depth increases, gradually approaches , accurately reflecting the characteristic of significant noise enhancement in far-view regions.

In order to obtain the depth to implement this model and avoid relying on additional sensors, we indirectly estimate the depth from a single input image based on the underwater optical imaging model and the dark channel prior. First, the transmission is estimated. Using the dark channel prior, the transmission estimation formula is as follows:

where denotes the transmission at pixel x, represents the intensity of the observed image at pixel y in color channel c, is the estimated global atmospheric light in channel c, denotes a local square patch centered at pixel x, and is a constant used to retain a small amount of haze for visual naturalness, typically set to 0.95. Subsequently, the depth map can be inversely solved from the transmission definition:

The depth map derived from Equation (4) is then fed into Equation (2) to compute the spatially varying noise intensity , which is further integrated into the regularization term of the variational energy function to enable spatially adaptive denoising in VSJE. This design combines physical modeling and image prior, enabling accurate acquisition of depth information without additional hardware and providing support for spatially non-uniform modeling of noise.

3.2. Calculation of Channel Sensitivity Coefficients

In underwater environments, the wavelengths of red, green, and blue channel lights are different, leading to significant differences in the attenuation rates in water and thus distinct sensitivities of each channel to noise and color cast. To achieve spectral adaptive processing, this paper proposes a channel sensitivity coefficient calculation method based on multi-dimensional statistics, which quantifies the inherent characteristics of each channel to provide a basis for subsequent differentiated processing. The specific steps are as follows:

(1) For each channel , the attenuation of light in water is most prominent in the dark regions of the image, where the pixel values are dominated by the absorption and scattering effects of the water medium rather than the true scene radiance. Therefore, we capture the dark-region attenuation information of each channel by computing the local minimum brightness within a neighborhood, which serves as a direct indicator of the channel’s attenuation degree:

where is the local pixel area centered on pixel x. This formula highlights the dark-region pixels most affected by water attenuation in the channel by taking the minimum value of the local area, indirectly reflecting the attenuation degree of the channel.

(2) To comprehensively characterize the quality of each color channel, we need to extract three core statistical features that correlate with attenuation, brightness, and detail preservation—three key factors determining channel sensitivity to noise and color cast. First, the mean of the local minimum brightness reflects the overall proportion of dark regions in the channel, which is positively correlated with the channel’s attenuation level. Second, the average intensity of the channel quantifies the overall brightness level. For example, due to higher attenuation in underwater images, the red channel usually exhibits lower brightness. Third, the contrast of the channel (measured by the root mean square deviation of pixel values) reflects the dispersion degree of pixel intensities; a lower contrast indicates more severe detail loss caused by water scattering and noise interference:

(3) Based on the three statistical features above, we need to construct a unified weight metric to integrate attenuation, brightness, and detail information, thereby quantifying the comprehensive sensitivity of each channel. The weight is designed with a penalty mechanism for channels with poor quality: channels with severe attenuation, low brightness, or low detail retention will receive lower weights, corresponding to higher sensitivity that requires stronger subsequent processing.

The design logic of the weight formula is as follows: penalizes channels with severe attenuation, penalizes channels with missing details, and penalizes channels with insufficient brightness. A larger product of the three indicates better channel quality and lower sensitivity.

Since the three statistical features are in different value ranges, direct multiplication will lead to incomparable weights across channels. To eliminate the scale difference and ensure that the sum of weights of the three channels is 1, we perform a normalization operation on the raw weights:

Finally, in order to map the normalized weights to a preset reasonable range and avoid some channels being over-processed or under-processed, we perform a linear calibration to obtain the final channel sensitivity coefficients. The linear transformation ensures that the sensitivity coefficients have limits and are comparable, with larger coefficients corresponding to higher sensitivity of the channels to noise and color bias:

where and are the preset reasonable ranges of the coefficient, used to avoid processing imbalance caused by extreme coefficient values. A larger value indicates that the channel is more sensitive to noise and color cast, requiring stronger processing intensity.

3.3. Design of Regularization Intensity

The regularization parameter is the key to balancing the denoising effect and detail preservation. Traditional fixed-parameter design cannot adapt to the spatial noise differences and spectral channel characteristics of underwater images. We propose a spatial–spectral dual-adaptive regularization intensity , whose expression is written as follows:

where is the basic regularization intensity, is the sensitivity coefficient of channel c, and is the noise intensity at that position. This design enables the denoising and color correction process to have spatial–spectral dual adaptability. Spectral adaptability: The regularization intensity of different channels is regulated by , and sensitive channels (with large ) are assigned stronger regularization to ensure the pertinence of noise suppression and color cast correction. Spatial adaptability: The regularization intensity of different spatial positions is regulated by , with stronger regularization in regions with high noise intensity (e.g., far-view regions) and weaker regularization in regions with low noise intensity (e.g., near-view regions), avoiding detail loss caused by over-smoothing.

3.4. Construction of Energy Function

To avoid conflicts between denoising and color cast correction caused by phased processing, VSJE constructs a unified energy function , integrating the two tasks into a single optimization problem to achieve joint optimization. The design of this energy function follows a variational regularization framework, which combines three core components—adaptive gradient regularization, data fidelity, and color consistency—based on the physical characteristics of underwater image degradation and the requirements of visual quality restoration. The expression of the energy function is as follows:

where is the image channel to be restored, is the input channel image, is the average value of the three channels, and and are the balance parameters between the data fidelity term and the color consistency term, respectively.

The energy function is constructed based on three design principles, each corresponding to a specific term in the equation, and the integration of these terms is guided by the goal of synergistic suppression of coupled degradation (spatially heterogeneous noise and spectral channel attenuation). is designed to suppress spatially heterogeneous noise while preserving image edges and details, and its construction is tightly coupled with the depth-aware noise model (Equation (2)) and channel-sensitive attenuation characteristics of underwater images. The regularization coefficient is defined as a function of the noise intensity from Equation (2). In near-view regions with low noise, increases to strengthen gradient constraints and preserve fine details; in far-view regions with high noise, decreases to relax gradient constraints and enhance noise suppression. For RGB channels with different attenuation levels, is further weighted by the channel sensitivity coefficient (calculated from the dark channel mean and contrast of each channel).

is constructed to constrain the similarity between the restored image and the input image , preventing information loss caused by over-correction of noise and color cast. The L2 norm is selected for this term to ensure the stability of the optimization process, as L2 fidelity terms have smooth loss surfaces that facilitate convergence in numerical optimization. is designed to correct spectral attenuation-induced color cast, and its construction is motivated by the gray world assumption (a classic color constancy principle adapted to underwater scenes). The term constrains each restored channel to be close to the average channel intensity , narrowing the intensity gap between RGB channels caused by selective absorption. For example, in deep underwater images where the red channel is severely attenuated, this term will pull the red channel intensity toward , mitigating blue-green color cast.

We then introduce the auxiliary variable , transforming the original problem into the following:

Then, we construct the augmented Lagrangian function, where is the dual variable:

To minimize the objective function, we use ADMM to iteratively update , and to compute the optimal solution.

Update as follows:

Update as follows:

Update as follows:

By minimizing this energy function, the optimal balance can be achieved among noise suppression, data fidelity, and color consistency, while realizing synchronous denoising and color cast correction without phase conflicts. The final output restored image u is the result of this variational optimization.

4. Experiments

4.1. Qualitative Evaluation

4.1.1. Image Visualization Comparison

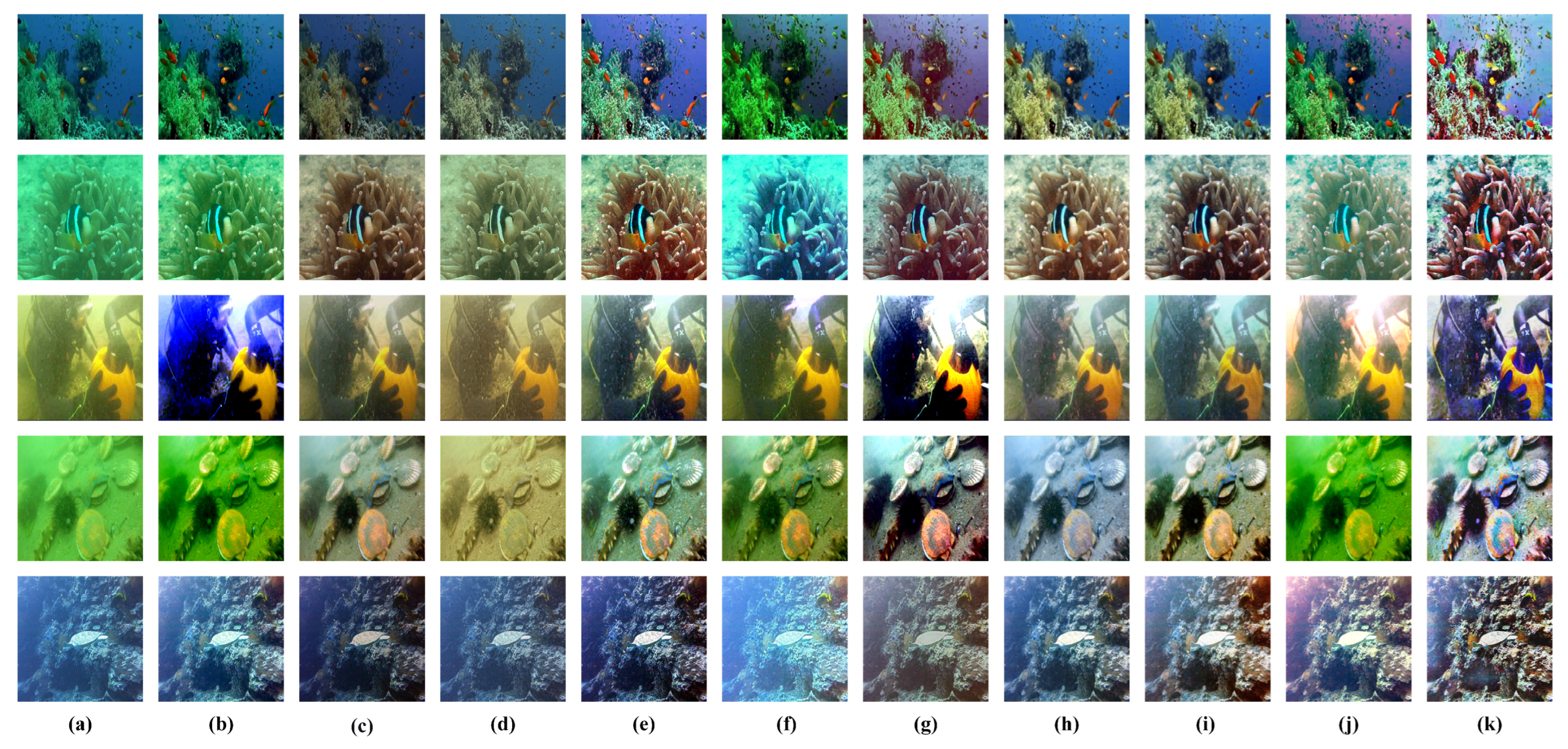

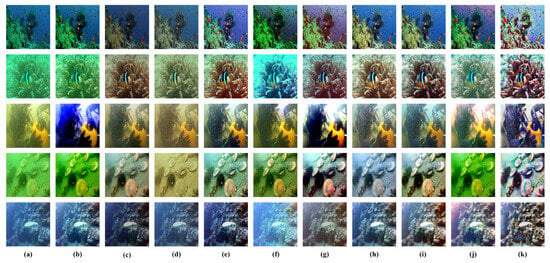

In order to more intuitively demonstrate that our method has better visual effects compared to existing underwater image enhancement methods, we selected several underwater images with different styles to compare the enhancement results of various methods. The visual comparison results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visual comparative evaluation of various methods on the UIEB [11], U45 [19], and MABLS [17] datasets. From left to right: (a) RAW; (b) IBLA [15]; (c) WaterNet [11]; (d) UWCNN [23]; (e) CBM [24]; (f) GDCP [10]; (g) HLRP [25]; (h) Restormer [22]; (i) SGUIE [21]; (j) SMBL [17]; (k) our method.

GDCP [10] has limitations in color correction, with color reproduction sometimes appearing unnatural in certain scenes, such as over-enhanced green tones that lead to color distortion; it also lacks adaptability to complex scattering environments, with limited detail enhancement. IBLA [15] shows significant color reproduction deviations, causing the overall image color to differ from the real scene; meanwhile, its detail enhancement is insufficient, and some areas remain blurry. WaterNet [11] has weak dehazing effects for underwater images, with negligible improvement in overall image transparency, and details in dark areas tend to be obscured. Underwater scene prior inspired deep underwater image and video enhancement (UWCNN [23]) processed images often experience color distortion, and contrast is over-enhanced, leading to overexposed highlights and lost texture information. An Underwater Image Vision Enhancement Algorithm Based on Contour Bougie Morphology (CBM [24]) has color correction deviations in certain scenes and insufficient detail preservation in complex backgrounds. Underwater Image Enhancement With Hyper-Laplacian Reflectance Priors (HLRP [25]) tends to overly stylize colors, shifting image tones toward unnatural warm hues and losing the original underwater colors; its ability to preserve image details is weak, with texture edges easily blurred. Restormer [22] shows limited improvement in image clarity when handling highly scattered, high-noise underwater images, with some residual blurriness; its color correction accuracy is insufficient, and color bias in certain areas is not effectively addressed. SGUIE [21] exhibits locally over- or under-enhanced regions, such as loss of detail in bright areas while dark areas remain blurry; color reproduction consistency is poor, with unnatural transitions across different regions. SMBL [17] performs poorly in noise suppression for underwater images, with enhanced images still showing noticeable noise; color correction tends to be biased, such as over-strengthened blue tones, leading to imbalanced image colors. In contrast, our method can accurately restore the true colors of underwater scenes and effectively enhance image contrast, making the layers between foreground and background more distinct.

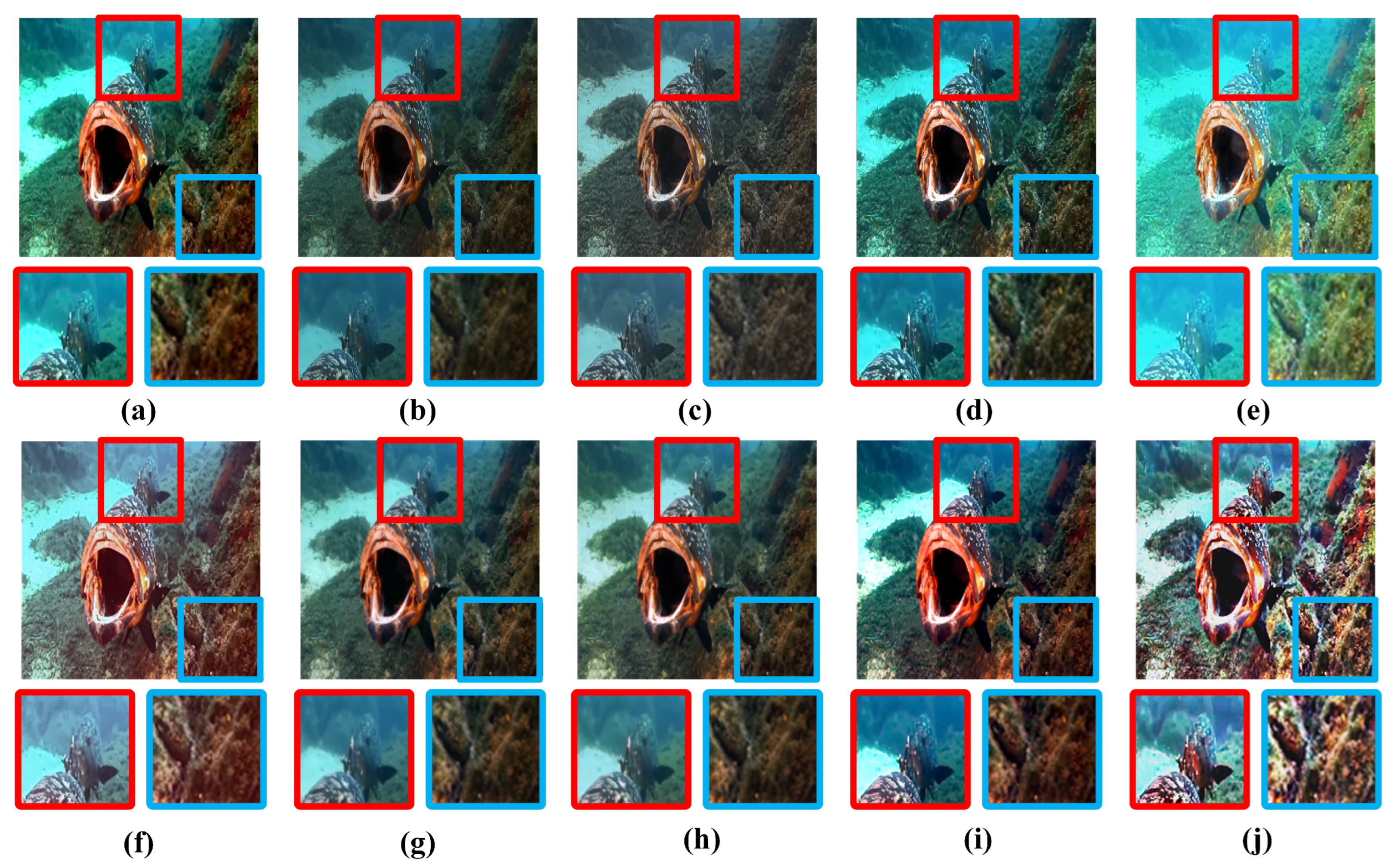

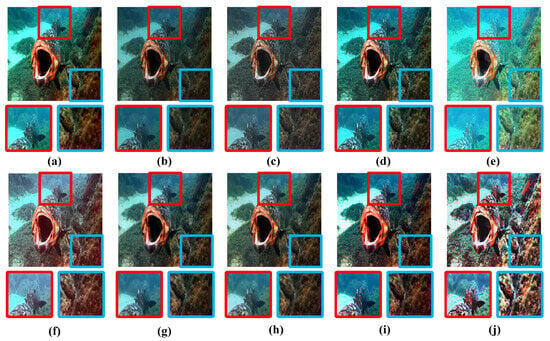

4.1.2. Image Detail Comparison

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, scenes with characteristics of blurred color bias were selected from the U45 dataset. As shown in Figure 3, the comparison of image detail enhancement for each method is presented, with zoomed-in sections highlighting the effect of each method on image detail enhancement.

Figure 3.

Detail enhancement comparison of various methods. From left to right: (a) IBLA [15]; (b) WaterNet [11]; (c) UWCNN [23]; (d) CBM [24]; (e) GDCP [10]; (f) HLRP [25]; (g) Restormer [22]; (h) SGUIE [21]; (i) SMBL [17]; (j) our method.

In terms of haze removal, GDCP [10], SMBL [17], and Restormer [22] perform unsatisfactorily, with noticeable scattering blur still present in their enhanced results, especially in distant areas, where the haze caused by suspended particles in water is not completely eliminated. IBLA [15] shows insufficient contrast improvement in shadow areas, and texture details remain dark and blurry. WaterNet [11] has limited effectiveness in removing haze, with no significant clarity improvement in distant areas. UWCNN [23] has weak haze removal capabilities, particularly failing to alleviate haze in distant regions; simultaneously, contrast and brightness recovery in shadow areas are inadequate. CBM [24] still leaves scattering-induced blur in distant regions, and the enhancement of texture details in shadow areas is insufficient, with some color distortion issues. HLRP [25] fails to effectively restore the image’s color, and recovery in shadow areas is unsatisfactory; due to low brightness and contrast, it remains blurry. SGUIE [21] performs poorly in color recovery with low saturation and does not adequately enhance shadow areas in the image. In contrast, our method successfully removes haze, restores saturation, and enhances image contrast.

4.2. Quantitative Evaluation

In order to more objectively demonstrate the performance of the proposed model, the quality of the restored images is comprehensively evaluated using objective assessment techniques. To provide a robust and fair evaluation of different methods, this study tests on three well-known publicly available datasets: An Underwater Image Enhancement Benchmark Dataset and Beyond (UIEB [11]), Enhancement of Underwater Images With Statistical Model of Background Light and Optimization of Transmission Map (MABLs [17]), and Enhancing underwater images and videos by fusion (U45 [19]). Specifically, the UIEB [11] dataset consists of 950 real underwater images, with the following clearly defined subsets based on the official division criteria of scene distribution balance and degradation level balance: (1) UIEBD-TRAIN subset: 800 paired images (degraded input + reference clear image), used for training deep learning models; (2) UIEBD-VAL subset: 90 paired images (degraded input + reference clear image), reserved for paired test evaluation; (3) UIEBD-TEST subset: 60 unpaired images (only degraded input, no reference clear image), reserved for unpaired test evaluation. The MABLs [17] dataset includes a variety of underwater scenes, such as single fish, schools of fish, coral, and diving scenarios. It also covers a range of distortion levels, such as deep water and low-visibility conditions. This dataset is well-known for its manually annotated background light within the images. U45 [19] is a commonly used underwater image test dataset characterized by typical underwater image degradation features such as severe light scattering, significant color cast, and low contrast. This dataset is selected to ensure comprehensive representation of various underwater environments.

To evaluate image quality, we used six different metrics: Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation (UCIQE [26]), Rank-based Underwater Image Quality Evaluation (URanker [27]), Underwater Image Chromatic Measure (UICM [28]), Multi-scale Image Quality Assessment (Musiq [29]), Perceptual Image Quality Assessment based on Pairwise Image Comparison (PAQ2PIQ [30]), and Convolutional Neural Network-based Image Quality Assessment (CNNIQA [31]). UCIQE [26] assesses image quality by considering chroma, saturation, and contrast, assigning higher scores to better-quality images. URanker [27] ranks enhanced underwater images generated by various enhancement algorithms based on color fidelity and local image degradation, with higher scores indicating better image quality. UICM [28] evaluates the color richness of underwater images; a higher index indicates better image quality. Musiq [29] quantifies image quality using features from the human visual system and distortion detection, with higher scores indicating better quality. PAQ2PIQ [30] uses a perceptual approach to assess image quality, providing detailed evaluations where higher scores signify better quality. CNNIQA [31] adopts a CNN model to predict the quality of images without reference, with higher scores indicating higher quality.

Table 1 lists the average scores of our method compared with IBLA [15], GDCP [10], SMBL [17], HLRP [25], SGUIE [21], Restormer [22], WaterNet [11], UWCNN [23] and CBM [24] on three datasets (UIEBD [11], U45 [19], and MABLs [17]) using several no-reference quality metrics, including UCIQE [26], URanker [27], UICM [28], Musiq [29], PAQ2PIQ [30], and CNNIQA [31]. Among these scores, those marked in red indicate the first place, while those marked in blue indicate the second place.

Table 1.

Objective comparison for various methods on UIEBD, U45, and MABLs datasets. The best result for each dataset is in red, and the second-best is in blue.

From the limitations of previous studies, traditional physics-driven underwater image enhancement methods (such as GDCP [10] and IBLA [15]), while physically interpretable, generally assume uniform noise and globally fixed regularization parameters, which cannot adapt to the depth-dependent noise and spectral attenuation differences among channels. GDCP [10] attains a UICM [28] score of only 6.9332 on the UIEBD-VAL [11] dataset, which is substantially lower than the 9.0740 achieved by the proposed method. This performance gap is primarily due to GDCP’s limited ability to correct color bias, as illustrated in Figure 2. GDCP produces noticeable color imbalance, particularly in scenes with severe wavelength-dependent degradation. As a result, residual color imbalance persists, limiting the effectiveness of color restoration. Mainstream data-driven methods (such as WaterNet [11] and UWCNN [23]), although achieving certain advantages on specific datasets, are limited by the scene distribution of training data. In extreme high-turbidity scenarios in U45 [19], the MUSIQ [29] scores are only 44.3754 (WaterNet [11]) and 47.9955 (UWCNN [23]), lower than our method’s 49.8634. These methods also suffer from insufficient model interpretability, making it difficult to handle unseen degraded scenes.

Grounded in the physical principles of underwater optical imaging, this study introduces a two-dimensional degradation hypothesis that jointly models spatially heterogeneous noise and spectrally channel-sensitive degradation. The proposed formulation integrates a depth-aware noise attenuation model with multi-dimensional statistical sensitivity coefficients across spectral channels, enabling precise characterization of the coupled degradation patterns commonly observed in underwater images. Comprehensive experimental validation demonstrates the effectiveness of this hypothesis: the proposed method ranks within the top two across 83% of core evaluation metrics, while also exhibiting significantly lower performance variance across datasets compared to learning-based approaches. These results highlight the advantages of physically guided adaptive modeling over traditional enhancement frameworks, particularly in terms of robustness and generalization.

VSJE demonstrates outstanding performance in the field of underwater image enhancement, demonstrating significant advantages across multiple core evaluation metrics on the UIEBD [11] datasets, including the VAL and TEST subsets, as well as on the U45 [19] and MABLs [17] datasets. Taking the UIEBD-VAL, UIEBD-TEST [11], and U45 [19] datasets as examples, our method ranks in the top two for 83% of the six key metrics: UCIQE [26], URanker [27], CNNIQA [31], UICM [28], MUSIQ [29], and PAQ2PIQ [30]. This result fully proves that our method excels in color restoration accuracy, contrast enhancement effectiveness, detail preservation, and overall user subjective visual experience. Notably, in UICM [28], UCIQE [26], and URanker [27], our method shows a clear advantage over mainstream comparative methods such as GDCP [10], SMBL [17], and HLRP [25]. Quantitative experiments demonstrate the broad applicability and excellent robustness of our method for image enhancement tasks across different underwater scenes and varying levels of degradation.

4.3. Subjective Quality Assessment

To objectively validate the visual quality improvement of the proposed method from a human perception perspective, a standardized subjective evaluation experiment was designed with a representative observer group. This experiment strictly follows the ITU-R BT.500-13 [32] standard to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of evaluation results, making up for the limitations of single visual comparison.

A total of 30 subjects were recruited, divided into two groups to cover different professional backgrounds and perceptual perspectives, ensuring the representativeness of the evaluation. Group 1 (Expert Group) included 10 researchers in underwater image processing or computer vision, who are proficient in identifying subtle differences in color fidelity, detail preservation, and distortion levels. Group 2 (Non-Expert Group) consisted of 20 subjects (11 males and 9 females, aged 22–45) with no professional background in image processing but with normal color vision, which helped to evaluate the consistency between enhanced images and real underwater scenes. All subjects were required to complete a pre-experiment training to familiarize themselves with the evaluation criteria and process, reducing individual bias.

The double-stimulus continuous quality scale method was adopted for the experiment. A total of 60 test images were selected from UIEBD-TEST [11], U45 [19], and MABLs [17] datasets, covering different degradation types (severe color cast, high turbidity, and low contrast) and scene styles (coral reefs, fish schools, and underwater landscapes). For each test image, the original degraded image and the enhanced images of 10 methods (including our method) were paired and randomly presented on a calibrated display device (1920 × 1080 resolution, 200 cd/m2 brightness, color temperature 6500K). The viewing distance was set to 3 times the screen height, and the indoor ambient light was controlled at 50–80 lux to avoid glare interference. Subjects were asked to score each enhanced image on a 5-point scale based on four core dimensions: color naturalness (consistency with real underwater scenes), detail clarity (texture edge preservation), and contrast rationality (layer distinction without over/under-enhancement). The scoring criteria were clearly defined: 5 points (excellent, no obvious defects), 4 points (good, slight defects not affecting perception), 3 points (fair, noticeable defects but acceptable), 2 points (poor, obvious defects affecting perception), 1 point (bad, serious defects and unrecognizable details). Each image pair was displayed for 8 s, followed by a 1 s gray screen interval to eliminate memory bias. The entire experiment was divided into 3 sessions with a 5 min break between sessions to avoid visual fatigue.

After collecting all scores, the consistency of the observer group was first verified using Kendall’s W coefficient and Cronbach’s coefficient. The results showed that Kendall’s W for the expert group, it was 0.82, and for the non-expert group was 0.76, both greater than 0.7, indicating good consistency among observers and reliable evaluation data. Cronbach’s coefficient was 0.89, confirming the internal consistency of the evaluation dimensions. From the results in Table 2, it can be concluded that our method achieved the best overall results in terms of color naturalness, detail clarity, and contrast rationality.

Table 2.

Objective Comparison for Various Methods on UIEBD-TEST, U45, and MABLs Datasets. The best result for each dataset is in red, and the second-best is in blue.

4.4. Ablation Study

To verify the positive impact of each proposed method on the output results, we conduct ablation experiments on the T90 [11] dataset. The experiment is divided into the following parts:

a. Replace space-adaptive noise intensity with a globally fixed value.

b. Replace the spectral adaptive coefficient with an equal fixed value.

c. Replace edge-aware regularization with standard L2 regularization.

Ablation experiments were conducted on the UIEBD-VAL [11] dataset, and six metrics for each module were measured in detail to comprehensively evaluate the impact of each module. The objective results of the ablation experiments are shown in Table 3. Notably, our method demonstrated the best overall performance on this dataset, further confirming its superiority. When each module was removed one by one, the overall metric of our method generally decreased, indicating the critical role of each sub-method in the proposed approach and showing that each module makes a positive contribution to the final results. This series of experimental results not only reinforces the superiority of our method on the T90 [11] dataset but also reveals the unique contribution of each module within the overall approach.

Table 3.

Objective results of the ablation study.

5. Discussion

From the perspective of future development, the proposed framework exhibits several promising directions for continued advancement. The key consideration involves algorithmic lightweighting and real-time performance optimization. The current implementation adopts an ADMM-based iterative strategy, which, while effective, incurs considerable computational cost—approximately 0.8 s per image. This latency presents limitations for time-sensitive tasks such as real-time navigation in autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), where sub-second or even millisecond-level inference is often required. To overcome this constraint, future efforts may incorporate multi-scale variational decomposition to reformulate high-resolution optimization into hierarchical subproblems. In conjunction with model quantization and GPU-parallel acceleration, such strategies are expected to yield substantial gains in inference efficiency and enable real-time deployment in embedded platforms. In addition, there is still room for improvement in the depth estimation module of our method. Currently, the depth estimation of our underwater image enhancement method relies solely on the dark channel prior, whose accuracy is limited in underwater scenes with uniform illumination and no significant dark regions. This directly impairs the reliability of depth-aware noise modeling and adaptive processing.

In addition to computational improvements, advancing the framework through multimodal information fusion holds significant potential. In ultra-long-range underwater environments where red wavelengths are severely attenuated, single-channel optical imagery becomes intrinsically incomplete. Integrating auxiliary modalities—such as polarization imaging and sonar-based point clouds—can compensate for the missing information. Polarization data contribute to scattering suppression, while sonar observations offer geometric priors and approximate depth cues. Such multimodal fusion can enhance robustness and visual quality in severely degraded conditions.

6. Conclusions

To address the multidimensional degradation of underwater images caused by the coupling of spatially heterogeneous noise and spectral channel attenuation, we introduce VSJE. The proposed method achieves spatially adaptive denoising through deep perception-based noise modeling and constructs channel-sensitive coefficients using multidimensional statistics to facilitate spectral differentiation. A unified variational energy function is employed to enable multi-objective collaborative optimization. Experimental results on three major public datasets demonstrate that VSJE significantly outperforms mainstream algorithms in both objective metrics and subjective visual quality. Notably, the method shows exceptional robustness and generalization capabilities in complex degradation scenarios. Quantitative results indicate that VSJE outperforms the SGUIE method by 64.65% and 16.03% in UICM and URanker, respectively, and exceeds the Restormer method by 73.37% and 16.16%, respectively. Extensive experiments further validate the method’s effectiveness in color restoration and detail enhancement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., S.C. and J.Z.; methodology, B.L., S.C. and J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, B.L., S.C., J.Z. and D.Z. (Dehuan Zhang); formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, S.C. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L., S.C., J.Z. and D.Z. (Dehuan Zhang); writing—review and editing, B.L., S.C., J.Z. and D.Z. (Deming Zhang); visualization, B.L., S.C., J.Z. and D.Z. (Deming Zhang); supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, B.L. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Intelligent Policing Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, No. ZNJW2026KFQN002; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62301105); in part by the Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Plan Joint Program (Natural Science Foundation—General Program) (No. 2025-MSLH-113); in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 3132025268); and in part by the Fundamental Research Funds of the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (No. LJ212510151021).

Data Availability Statement

The UIEB, U45, and MABLs datasets utilized in this study are publicly accessible for academic research purposes. Specifically, the datasets can be retrieved from their respective official repositories via the following URLs: UIEB at https://li-chongyi.github.io/proj_benchmark (accessed on 11 March 2024), U45 at https://github.com/IPNUISTlegal/underwater-test-dataset-U45- (accessed on 11 March 2024), and MABLs at https://github.com/wangyanckxx/Enhancement-of-Underwater-Images-with-Statistical-Model-of-BL-and-Optimization-of-TM (accessed on 11 March 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, Q.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, W.; Li, C. Perception-Driven Deep Underwater Image Enhancement Without Paired Supervision. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 4884–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, C.; Ren, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, P. A Perception-Aware Decomposition and Fusion Framework for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, S.; Fu, X.; Li, X. Spatial Residual for Underwater Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 4996–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Sohel, F. A pixel distribution remapping and multi-prior retinex variational model for underwater image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 7838–7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement by Attenuated Color Channel Correction and Detail Preserved Contrast Enhancement. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 47, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaynak, D.; Treibitz, T. A Revised Underwater Image Formation Model. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6723–6732. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, D.; Levy, D.; Avidan, S.; Treibitz, T. Underwater Single Image Color Restoration Using Haze-Lines and a New Quantitative Dataset. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 2822–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Contrastive Semi-Supervised Learning for Underwater Image Restoration via Reliable Bank. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18145–18155. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 1956–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.-T.; Cao, K.; Cosman, P.C. Generalization of the Dark Channel Prior for Single Image Restoration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 2856–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Guo, C.; Ren, W.; Cong, R.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Tao, D. An Underwater Image Enhancement Benchmark Dataset and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 4376–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Anwar, S.; Hou, J.; Cong, R.; Guo, C.; Ren, W. Underwater Image Enhancement via Medium Transmission-Guided Multi-Color Space Embedding. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 4985–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlevaris-Bianco, N.; Mohan, A.; Eustice, R.M. Initial results in underwater single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the Oceans 2010 MTS/IEEE Seattle, Seattle, WA, USA, 20–23 September 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Drews, P., Jr.; do Nascimento, E.; Moraes, F.; Botelho, S.; Campos, M. Transmission Estimation in Underwater Single Images. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 825–830. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.-T.; Cosman, P.C. Underwater Image Restoration Based on Image Blurriness and Light Absorption. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, D.; Avidan, S. Diving into Haze-Lines: Color Restoration of Underwater Images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Liotta, A.; Perra, C. Enhancement of Underwater Images with Statistical Model of Background Light and Optimization of Transmission Map. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2020, 66, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Tjondronegoro, D. A Rapid Scene Depth Estimation Model Based on Underwater Light Attenuation Prior for Underwater Image Restoration. In Advances in Multimedia Information Processing–PCM 2018; Hong, R., Cheng, W.H., Yamasaki, T., Wang, M., Ngo, C.W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11164, pp. 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- Ancuti, C.; Ancuti, C.O.; Haber, T.; Bekaert, P. Enhancing underwater images and videos by fusion. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ancuti, C.O.; Ancuti, C.; De Vleeschouwer, C.; Bekaert, P. Color Balance and Fusion for Underwater Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Q.; Li, K.; Zheng, H.; Gao, X.; Hou, G.; Sun, K. SGUIE-Net: Semantic Attention Guided Underwater Image Enhancement With Multi-Scale Perception. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 6816–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.-H. Restormer: Efficient Transformer for High-Resolution Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Anwar, S.; Porikli, F. Underwater scene prior inspired deep underwater image and video enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 98, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cao, W.; Cai, Z.; Su, B. An Underwater Image Vision Enhancement Algorithm Based on Contour Bougie Morphology. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 8117–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Wu, J.; Porikli, F.; Li, C. Underwater Image Enhancement with Hyper-Laplacian Reflectance Priors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 5442–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Sowmya, A. An Underwater Color Image Quality Evaluation Metric. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 6062–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wu, R.; Jin, X.; Han, L.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, C. Underwater Ranker: Learn Which Is Better and How to Be Better. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 22 February–1 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Panetta, K.; Gao, C.; Agaian, S. Human-Visual-System-Inspired Underwater Image Quality Measures. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2016, 41, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Milanfar, P.; Yang, F. MUSIQ: Multi-scale Image Quality Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 5128–5137. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Z.; Niu, H.; Gupta, P.; Mahajan, D.; Ghadiyaram, D.; Bovik, A. From Patches to Pictures (PaQ-2-PiQ): Mapping the Perceptual Space of Picture Quality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3572–3582. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, M.; Li, Q. Convolutional Neural Networks Based on Residual Block for No-Reference Image Quality Assessment of Smartphone Camera Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), London, UK, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Jiang, G.; Yu, M.; Luo, T.; Zhang, X.; Ying, H. Underwater Image Quality Assessment from Synthetic to Real-World: Dataset and Objective Method. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.