Abstract

Background: Rehabilitation of head and neck cancer patients with acquired intraoral defects is challenging and requires multidisciplinary collaboration. This case report describes an integrated surgical and prosthetic approach in which palatal obturator rehabilitation is used to restore palatal integrity, speech, swallowing, aesthetics, and overall quality of life after maxillectomy. The objective is to show how careful surgical planning to optimize prosthetic prognosis, combined with a precisely designed obturator prosthesis, can achieve satisfactory functional rehabilitation. Methods: A man in his 50s with sinonasal carcinoma underwent partial left maxillectomy followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The defect was classified as Aramany class I and Brown class 2b, and the surgical resection was planned to preserve structures favorable to prosthetic support. Prosthetic management included fabrication of a removable partial denture incorporating a hollow-bulb obturator. Results: During trial and delivery, the patient demonstrated improved speech and swallowing, enhanced denture stability, and favorable aesthetics. The patient reported satisfaction with functional and cosmetic outcomes and was provided with instructions for use and cleaning, with a plan for regular follow-up. Conclusions: Palatal obturator prostheses remain a gold standard for unilateral maxillectomy rehabilitation when adequate retention is achievable. Surgical-prosthetic collaboration permits restoring palatal contours, and dentition can normalize speech and swallowing, and substantially improve the quality of life.

1. Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) are common malignancies worldwide and remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with almost 0.9 million new cases and around half a million deaths estimated in 2021 [1]. Beyond survival statistics, these tumours profoundly affect how people eat, speak, breathe, and present themselves to others, so treatment is experienced not only as a battle against cancer but also as a challenge to preserve identity, relationships, and everyday roles [1,2].

Sinonasal carcinomas represent a small but particularly demanding subgroup of HNCs. They account for fewer than 5% of all head and neck neoplasms and have an incidence of approximately 0.5–1.0 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, typically presenting in older adults and often at advanced stages [3,4]. Their proximity to the orbit, skull base, and oral cavity means that oncologic surgery frequently results in complex maxillary and palatal defects. Multimodal treatment combining surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy is often required, but this can leave patients with persistent oro-nasal communication, impaired swallowing, hypernasal speech, and visible facial changes that may lead to social withdrawal and loss of self-confidence [2,3,4].

Maxillofacial rehabilitation aims not only to close these defects, but to give patients back the possibility to share a meal without leakage, speak on the phone without being misunderstood, and smile in public without feeling exposed. Removable palatal obturators remain a widely used option for unilateral maxillectomy defects when adequate support and retention can be achieved [5,6,7,8]. Observational studies and systematic reviews consistently show that well-designed obturators can significantly improve speech intelligibility, swallowing, mastication, and health-related quality of life, and that better obturator function is closely linked to psychological adjustment and social participation [5,6,7,8,9].

However, the quality of the prosthetic outcome is strongly influenced by how the ablative surgery is planned. Preservation of strategically important teeth and bony buttresses, careful shaping of defect margins, and the management of undercuts can greatly facilitate retention and stability of the future obturator, while still respecting oncologic principles [5,8,9]. For this reason, close collaboration between surgeons and prosthodontists—ideally beginning before tumour resection—offers a crucial opportunity to align tumour control with long-term functional and psychosocial rehabilitation [5,8].

In this case report, we describe the multidisciplinary management of a man in his 50s with sinonasal carcinoma treated by unilateral partial maxillectomy followed by chemoradiotherapy. Our objective is to illustrate how careful pre-surgical planning to optimise prosthetic prognosis, combined with a hollow-bulb removable partial denture obturator tailored to the patient’s needs, can restore palatal integrity, speech, swallowing, and aesthetics, supporting a meaningful return to everyday life [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

2. Clinical Case Presentation

A 57-year-old man has been diagnosed with sinonasal carcinoma (pT3N0M0, stage 3, R1) after going to the emergency room complaining of left upper airway obstruction. At the first visit, the patient didn’t know of any drug allergies. No other medical conditions. Not currently taking any medication. He denies having undergone radiation treatment or blood transfusions and reports not suffering from any chronic conditions. Intraoral examination reveals:

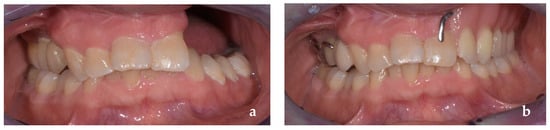

Intercalated edentulism of 14, widespread plaque and tartar. No mobile elements are found (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Palatal defect due to maxillectomy: (a) occlusal view; (b) frontal view; (c) lateral view.

After consultation with the ENT specialist and following an informative discussion with the patient, surgery is recommended. Subtotal left maxillectomy via midfacial degloving.

2.1. Surgical Procedures

Following infiltration of the superior oral and nasal vestibule, an incision was made in the oral and nasal vestibule. The procedure continued with midfacial degloving [10], left subtotal maxillectomy, extended to the subcutaneous tissue and the left orbital floor.

The surgical specimen and resection margins were sent for histological examination.

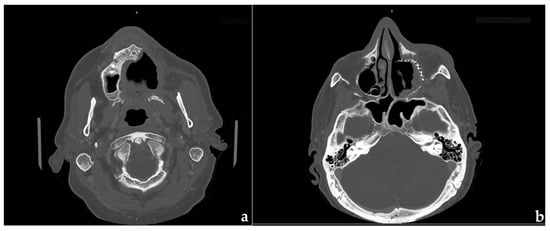

Meticulous hemostasis was achieved. A metallic mesh was placed to support the left orbital floor. A Foley catheter was inserted into the left nasal cavity. In the right nasal cavity, one Merocel sponge (sheathed in a glove finger) and a nasogastric tube were positioned. No bleeding was observed at the conclusion of the procedure. The tumor mass was about 11 cm (Figure 2a,b).

Figure 2.

CBCT slice: (a) pretreatment; (b) after surgery.

The patient’s prosthetic prognosis following subtotal maxillectomy was significantly enhanced through a series of meticulous surgical strategies [11]. Retention of the anterior maxilla improved prosthesis stability and support, enabling biomechanically favorable partial denture designs [12]. Skin grafting involved lining the reflected cheek flap with a split-thickness skin graft, which increased patient tolerance of the obturator, optimized retention, and ensured a more effective seal between the oral and nasal cavities. Preservation of teeth adjacent to the defect was achieved through a distal transalveolar resection, maximizing bony support and extending the clinical utility of the remaining teeth [13]. Management of palatal mucosa included reflecting and preserving mucosa during bony resection to cover the rounded medial bony margins, promoting better tissue integration [14]. Finally, strategic access to the defect was provided by exposing the superior and lateral aspects, allowing the prosthodontist to extend the obturator along the lateral wall, thereby enhancing overall prosthesis retention, stability, and functional support [15].

The resulting defect can be classified as class 1 with Aramany’s classification [16,17] and class 2b with Brown’s classification [18]. The patient’s chief complaint was the struggle to assume both liquids and solid food; moreover, conversations resulted in difficulty as the voice was extremely nasalised.

After undergoing a partial maxillectomy of the left palate, he received both radiotherapy (73 Gray, 35 fractions) and chemotherapy.

2.2. Prosthetic Management

The goals are to restore the portion between the nasal and oral cavity, restore palatal contours, and maintain the tongue space, replace the missing dentition, restore midfacial contours, and provide retention, stability, and support for the obturator prosthesis without compromising the health of residual dentition and supporting structures. These goals can almost always be realized when good communication exists between prosthodontic and surgical colleagues. The result is a surgical defect that is better suited for a prosthesis without compromising the resection of the tumor, as seen in Figure 1.

Given the extensive size of the neoplastic mass and the high doses of radiotherapy administered, the use of zygomatic implants was deemed unfeasible. Furthermore, the patient was no longer willing to undergo additional surgical procedures. Therefore, in agreement with the patient, a conventional obturator prosthesis was selected.

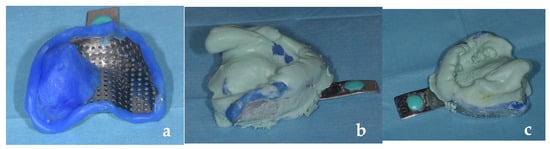

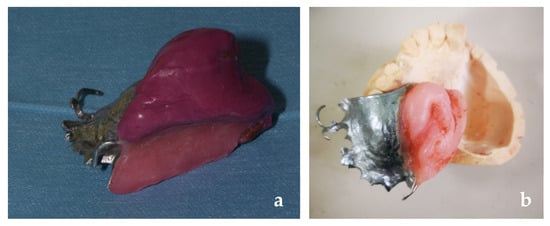

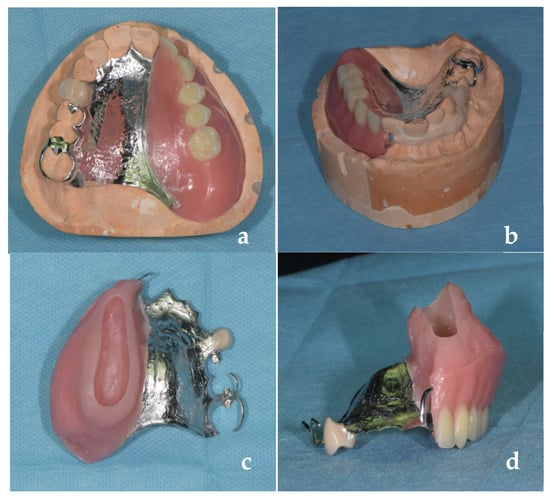

Six months after surgery, following the completion of radiotherapy sessions, the first impression was performed using alginate. Due to the depth of the defect could reduce the material precision, the prosthodontist used blue peripheral wax to personalize the standard tray (Figure 3). The technician produced the metal structure and an acrylic resin support base for the obturator. The structure design consists of a Bonwill double clamp on the molars and an Ibar clamp [19] on the central incisive (Figure 4). A full palate coverage was used as a primary connector. In the design of dental prostheses, several key principles must be observed to ensure both functional success and patient comfort. Rigidity in major connectors is essential to maintain structural integrity and prevent deformation under functional loads, especially in patients with a palatal defect. Occlusal rests should be strategically positioned to direct occlusal forces along the long axis of the abutment teeth, thereby minimizing the risk of tooth displacement or damage. The incorporation of guide planes serves to enhance stability and bracing, ensuring the prosthesis remains securely seated during function.

Figure 3.

First impression: (a) standard tray with blue wax border moulding; (b) extension of the alginate into the defect, left lateral view; (c) superior view.

Figure 4.

Metal framework: (a) it is appreciable the Bonwill double clamps, the total coverage of the palate and the wax rim; (b) it is appreciable the I-bar and the resin acrylic base.

Retentive elements must be carefully designed to operate within the physiologic tolerance of the periodontal ligament, avoiding excessive stress that could compromise periodontal health. To optimize support, the prosthesis should maximize contact with adjacent soft tissue and denture-bearing surfaces, distributing forces evenly and reducing pressure points. Finally, the overall design must prioritize cleansability, allowing for easy maintenance and hygiene to prevent plaque accumulation and associated complications. The selection of the I-bar clasp in this maxillofacial prosthesis adheres to the established principles of removable partial denture (RPD) design, particularly in terms of aesthetics, given its placement on a maxillary incisor [20]. In traditional RPDs, clasps must balance retention, support, and stability while minimizing visibility, especially in the anterior region [21].

However, in maxillofacial prosthetics, the functional demands on the dentate side often necessitate enhanced retention and support to counteract the unique biomechanical challenges posed by extensive defects and the leverage effects of extraoral prostheses [22]. The I-bar clasp, recognized as one of the most retentive clasp designs, is particularly advantageous in such cases due to its ability to provide superior retention without compromising the periodontal health of the abutment teeth [23]. This dual consideration—of both aesthetic integration and mechanical performance—underscores the rationale for its application in this clinical context.

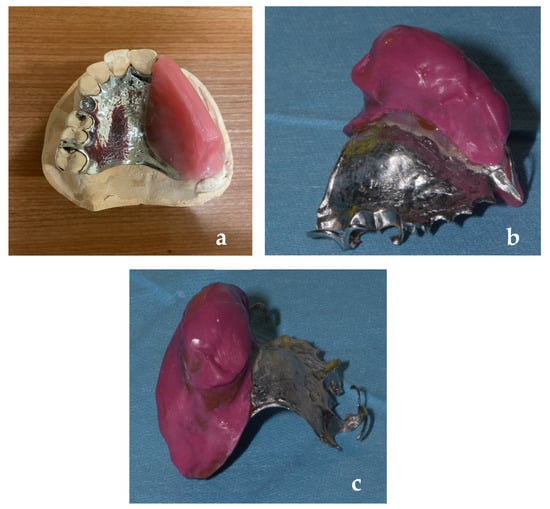

After physiological adjustment, to improve the precision of the obturator portion, we did an altered cast technique [24,25], using the prosthesis as a tray and modifying it with thermal compound (Figure 5). Occlusal dimension was relieved by wax rims and the shape and color teeth were chosen based on the features of the residual teeth. As seen in Figure 6 in the final step, the laboratory provides us with a hollow and open resin obturator bulk [13,26].

Figure 5.

Altered cast technique using thermoplastic compound: (a) lateral view; (b) internal wall impression, (c) posterior view.

Figure 6.

Definitive obturator prosthesis (a) occlusal view; (b) frontal view; (c) upper vision of the hollow bulky areas; (d) frontal view of bulky areas.

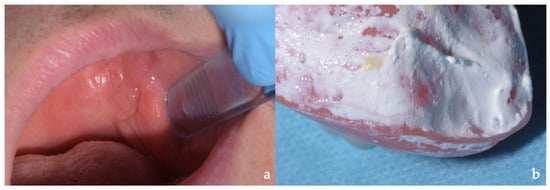

At the one-week check-up, the patient had developed a pressure sore at the level of the retromolar trigone, in the jugal mucosa (see Figure 7). After determining the exact location using PIP (Pressure Indicator Paste), the excess resin was removed.

Figure 7.

Intraoral frontal view (a) with the obturator prosthesis; (b) without the obturator prosthesis.

After one month, functional assessment tests were performed.

3. Results

By using the prosthesis during the trial session, the patient was able to speak and swallow normally. During the delivery process, denture stability and its impact on swallowing and speaking were clinically evaluated. The patient was satisfied with the restored aesthetics (Figure 7). Instructions on how to properly use and clean the prosthesis were given to avoid fungal superinfections, as in conventional prostheses. This complication should be considered possible even though there is no literature on the subject regarding obturators. A regular follow-up was arranged. The patient immediately showed improvements in chewing, swallowing, but above all, he was very satisfied with having almost completely recovered his pre-surgery phonation.

The chewing ability, as assessed by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), yielded a score of 7/10, indicating good but not optimal masticatory function. This result suggests that while the patient can effectively chew most foods, mild difficulties may persist with harder or tougher textures. Such a score reflects a clinically satisfactory outcome, though it may also highlight the need for further prosthetic adjustments or dietary modifications to enhance comfort and overall functional performance [27] (Figure 8). However, it can be considered a good result given the extent of the surgical defect and the short time that has passed since the delivery of the obturator.

Figure 8.

Pressure sore at the level of the retromolar trigone (a). Determination of the exact location using PIP (Pressure Indicator Paste). After one month of continuous use of the prosthesis, patient-reported outcome measures were performed. Regarding the degree of satisfaction assessed with the OFS (Obturator Functioning Scale), the patient scored 58 out of 75 [27].

4. Discussion

According to the literature, palatal obturators combined with removable partial dentures (RPDs) remain the gold standard for rehabilitating patients with unilateral maxillectomy defects. In most cases, surgical closure or reconstruction using soft tissue flaps is not recommended. When adequate retention for an obturator prosthesis is achievable—as demonstrated in the present case—speech and swallowing can be restored to near-normal levels in the majority of patients. Conversely, surgical closure may preclude prosthetic fabrication, resulting in compromised midfacial contours, impaired speech articulation, and difficulties with mastication and deglutition.

Rehabilitation success hinges on accurate restoration of palatal contours and precise positioning of prosthetic teeth. While reconstruction with free vascularized soft tissue flaps (e.g., the radial forearm flap) is technically feasible, it is generally discouraged. Such procedures often distort palatal anatomy, preventing proper denture tooth placement in subsequent RPDs. Additionally, mucus accumulation on the nasal surface of the flap can lead to drying, adhesion, and local infections, often accompanied by foul odor. Furthermore, facial contours—particularly those of the lips and cheeks—are more effectively restored using an obturator prosthesis than with soft tissue flaps, which frequently fail to provide adequate support for removable prostheses.

The clinical management described in the article of Nafij Bin et al. [28] utilized a hybrid analog-digital workflow, wherein a conventional putty elastomeric impression was employed to acquire a definitive gypsum cast. While this report successfully integrated digital data acquisition, design (CAD), and additive manufacturing (3D printing) for the final definitive hollow obturator, the necessity of incorporating conventional techniques for accurate cast production highlights why these analog fabrication steps often remain the established standard for complex maxillofacial rehabilitation. Nevertheless, digital prosthodontics is advancing substantially, and authors are developing extensive applications of Computer-Aided Design and 3D printing in the field of removable partial prostheses for oncological patients. This evolution has the potential to markedly reduce the design and manufacturing timeline for definitive prostheses, thereby facilitating critical early rehabilitation.

For most patients with maxillary defects resulting from oncologic surgery, obturator-based rehabilitation achieves near-normal function and aesthetics, often to the extent that even friends and acquaintances remain unaware of any impairment. This approach not only restores essential functions but also preserves social dignity.

Prosthetic rehabilitation in head and neck cancer survivors extends beyond cosmetic and masticatory concerns. It plays a pivotal role in restoring critical functions and significantly improving quality of life. These patients face not only physical and functional challenges but also profound psychological burdens that can undermine self-esteem and social reintegration. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating tumor resection with prosthetic planning, ensures optimal functional recovery and holistic rehabilitation, addressing both the physical and psychosocial consequences of cancer treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and M.C.; methodology and data curation, G.P. and V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

000030-7 January 2025 Comitato Etico Territoriale (CET) Interaziendale Aou Citta’ Della Salute e Della Scienza di Torino.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, J.; Xie, B.; Yi, X.; Wu, S.; Ji, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhuo, Q.; Li, G.; Fu, R.; Wang, J.; et al. Global Burden and Trends of Common Head and Neck Cancers between 1990 and 2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, L.Q.M. Head and Neck Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thawani, R.; Kim, M.S.; Arastu, A.; Feng, Z.; West, M.T.; Taflin, N.F.; Thein, K.Z.; Li, R.; Geltzeiler, M.; Lee, N.; et al. The Contemporary Management of Cancers of the Sinonasal Tract in Adults. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binazzi, A.; di Marzio, D.; Mensi, C.; Consonni, D.; Miligi, L.; Piro, S.; Zajacovà, J.; Sorasio, D.; Galli, P.; Camagni, A.; et al. Gender Differences in Sinonasal Cancer Incidence: Data from the Italian Registry. Cancers 2024, 16, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.M.; de Caxias, F.P.; Bitencourt, S.B.; Turcio, K.H.; Pesqueira, A.A.; Goiato, M.C. Oral Rehabilitation of Patients after Maxillectomy. A Systematic Review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblith, A.B.; Zlotolow, I.M.; Gooen, J.; Huryn, J.M.; Lerner, T.; Strong, E.W.; Shah, J.P.; Spiro, R.H.; Holland, J.C. Quality of Life of Maxillectomy Patients Using an Obturator Prosthesis. Head Neck 1996, 18, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, N.; Singaravel Chidambaranathan, A.; Balasubramanium, M.K.; Rajapandi, G.R.K. Role of Obturator in Restoring Quality of Life and Function in Maxillary Oncological Defect Cases—A Systematic Review. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 11, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saverio, C.; Antonio, B.; Hao, H.Z.; Silvia, P.; Gianluigi, C.; Dorina, L.; Carinci, F. Definitive Palatal Obturator Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ren, W.; Gao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhi, P.K. Function of Obturator Prosthesis after Maxillectomy and Prosthetic Obturator Rehabilitation. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 82, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, K.; Cobb, R.; Vassiliou, L.; Fry, A.; Cascarini, L. Scarless Total Maxillectomy: Midfacial Degloving with Extended Transconjunctival Retrocaruncular Approach. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 55, 857–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artopoulou, I.I.; Karademas, E.C.; Papadogeorgakis, N.; Papathanasiou, I.; Polyzois, G. Effects of Sociodemographic, Treatment Variables, and Medical Characteristics on Quality of Life of Patients with Maxillectomy Restored with Obturator Prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 118, 783–789.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Fattah, H.; Zaghloul, A.; Pedemonte, E.; Escuin, T. Pre-Prosthetic Surgical Alterations in Maxillectomy to Enhance the Prosthetic Prognoses as Part of Rehabilitation of Oral Cancer Patient. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, J.; Wolfaardt, J.; Seikaly, H.; Jha, N. Speech Outcomes in Patients Rehabilitated with Maxillary Obturator Prostheses after Maxillectomy: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2001, 15, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Rogers, S.; McNally, D.; Boyle, M. A Modified Classification for the Maxillectomy Defect. Head Neck 2000, 22, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Gaebler, C.; Beukelman, D.; Mahanna, G.; Marshall, J.; Lydiatt, D.; Lydiatt, W.M. Impact of Palatal Prosthodontic Intervention on Communication Performance of Patients’ Maxillectomy Defects: A Multilevel Outcome Study. Head Neck 2002, 24, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramany, M.A. Basic Principles of Obturator Design for Partially Edentulous Patients. Part I: Classification. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1978, 40, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramany, M.A. Basic Principles of Obturator Design for Partially Edentulous Patients. Part II: Design Principles. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2001, 86, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, G.R.; Tharp, G.E.; Rahn, A.O. Prosthodontic Principles in the Framework Design of Maxillary Obturator Prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1989, 62, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahross, H.Z.; Atito, E.M.; Mansour, M.M.; Badr, W.E.; Osman, M.S.; Quassem, M.A. Stress Analysis of Mandibular Kennedy Class I Partial Overdenture Submitted to Different Implant Length and Clasp Designs—An in Vitro Study. J. Prosthodont. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.B.; Brown, D.T. McCracken’s Removable Partial Prosthodontics, 13th ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2015; Available online: https://shop.elsevier.com/books/mccrackens-removable-partial-prosthodontics/carr/978-0-323-33990-2 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Krol, A.J. Clasp Design for Extension-Base Removable Partial Dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1973, 29, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, J.; Curtis, T.; Marunick, M. Maxillofacial Rehabilitation: Prosthodontic and Surgical Considerations; CV Mosby Company: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beumer, J.; Faulkner, R.F.; Shah, K.C.; Wu, B.M. Fundamentals of Implant Dentistry. Volume 1, Prosthodontic Principles; Quintessence Publishing: New Malden, UK, 2022; p. 610. [Google Scholar]

- Leupold, R.J.; Kratochvil, F.J. An Altered-Cast Procedure to Improve Tissue Support for Removable Partial Dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1965, 15, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.P.; Brudvik, J.S.; Noonan, C.J. Clinical Outcome of the Altered Cast Impression Procedure Compared with Use of a One-Piece Cast. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2004, 91, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, R.P. Obturator Prosthesis Design for Acquired Maxillary Defects. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1978, 39, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Khalifa, N.; Alhajj, M.N. Quality of Life and Problems Associated with Obturators of Patients with Maxillectomies. Head Face Med. 2018, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamayet, N.B.; Farook, T.H.; AL-Oulabi, A.; Johari, Y.; Patil, P.G. Digital Workflow and Virtual Validation of a 3D-Printed Definitive Hollow Obturator for a Large Palatal Defect. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.