Abstract

Quantum anomalies are traditionally understood as classical symmetries that fail to survive quantization, while experimental “anomalies” denote deviations between theoretical predictions and measured values. In this work, we develop a unified framework in which both phenomena can be interpreted through the lens of algebraic quantum field theory (AQFT). Building on the renormalization group viewed as an extension problem, we show that renormalization ambiguities correspond to nontrivial elements of Hochschild cohomology, giving rise to a deformation of the observable algebra , where is a Hochschild 2-cocycle. We interpret as an intrinsic algebraic curvature of the net of local algebras, namely the (local) Hochschild class that measures the obstruction to trivializing infinitesimal scheme changes by inner redefinitions under locality and covariance constraints. The transported product is associative; its first-order expansion is associative up to while preserving the ∗-structure and Ward identities to the first order. We prove the existence of nontrivial cocycles in the perturbative AQFT setting, derive the conditions under which the deformed product respects positivity and locality, and establish the compatibility with current conservation. The construction provides a direct algebraic bridge to standard cohomological anomalies (chiral, trace, and gravitational) and yields correlated deformations of physical amplitudes. Fixing the small deformation parameter from the muon discrepancy, we propagate the framework to predictions for the electron , charged lepton EDMs, and other low-energy observables. This approach reduces reliance on ad hoc form-factor parametrizations by organizing first-order scheme-induced deformations into correlation laws among low-energy observables. We argue that interpreting quantum anomalies as manifestations of algebraic curvature opens a pathway to a unified, testable account of renormalization ambiguities and their phenomenological consequences. We emphasize that the framework does not eliminate renormalization or quantum anomalies; rather, it repackages the finite renormalization freedom of pAQFT into cohomological data and relates it functorially to standard anomaly classes.

1. Introduction and Motivation

1.1. Quantum Anomalies Versus Experimental Discrepancies

A quantum anomaly is the failure of a classical symmetry of the action to be implementable at the quantum level after renormalization. Canonical examples include the axial (ABJ) anomaly in chiral currents, the trace (Weyl) anomaly of the stress tensor, and gravitational anomalies in theories of chiral matter [1,2,3,4,5]. By contrast, an experimental discrepancy denotes a persistent deviation between a theoretically predicted quantity and its measured value (e.g., the muon anomalous magnetic moment). These notions live at different conceptual layers: the former is a cohomological obstruction in the quantization/renormalization of symmetries, while the latter is a property of phenomenological comparison.

This work develops a framework in which renormalization ambiguities in algebraic quantum field theory (AQFT) are organized by Hochschild cohomology and thereby acquire the status of an intrinsic algebraic curvature of the observable algebra. Within this perspective, familiar quantum anomalies are realized as particular images of cohomology classes that govern the deformation of products of observables, while certain classes of low-energy discrepancies can be probed through universal correlation laws implied by the same deformation. The guiding principle is that changes in the renormalization scheme act as (local) automorphisms on the algebra of observables; infinitesimally, they define a 2-cocycle controlling deformations of the product. The nontrivial cohomology class of this cocycle is what we call algebraic curvature.

- Scope clarification.

Throughout, it is not claimed that quantum anomalies disappear. Standard gauge, trace/Weyl, and gravitational anomalies remain as cohomological obstructions to simultaneously enforcing locality, covariance, and Ward identities after renormalization. The present contribution is to identify a natural Hochschild-cohomological organization of renormalization ambiguities in pAQFT and to relate the resulting class to the familiar anomaly cohomology via a canonical map developed below.

1.2. AQFT, Renormalization as an Extension Problem, and the Stückelberg–Petermann Group

The AQFT approach associates each causally complete spacetime region O with - or von Neumann algebra of observables satisfying isotony, locality (Einstein causality), and covariance [6,7]. In the perturbative setting (pAQFT), interacting observables are constructed from microcausal functionals by time-ordered products that satisfy causal factorization, covariance, and microlocal spectral conditions [6,7,8,9].

Renormalization is posed as an extension problem: distributions defined away from coincident points must be extended to the diagonals in configuration space. The freedom in this extension is finite at each order and local in the sense of scaling degree, and it is canonically organized by the Stückelberg–Petermann renormalization group , a group of local field redefinitions acting on the time-ordered products (or equivalently on the Bogoliubov S-matrix) [7,10,11]. Two renormalization schemes T and related by an element produce the same physical S-matrix up to local counterterms fixed by renormalization conditions; the relative Z encodes the ambiguity data.

- Not a “solution” of renormalization.

We stress that we do not propose an alternative to the Epstein–Glaser/Hollands–Wald renormalization program. Renormalization is still implemented as the extension of distributions to coincident configurations subject to the usual normalization conditions. Our goal is instead to make the finite renormalization freedom (encoded by ) explicit in cohomological terms, thereby isolating scheme-invariant information under locality and covariance constraints.

- Renormalizability versus renormalization.

We do not claim to solve renormalization as a constructive procedure. Rather, assuming perturbative renormalizability in the Epstein–Glaser sense, we show that the residual finite renormalization freedom—encoded by the Stückelberg–Petermann group—is governed by a local Hochschild cohomology class. This class organizes scheme dependence under locality and covariance constraints and is what we interpret as an intrinsic algebraic curvature.

1.3. From Renormalization Freedom to Hochschild Cohomology

Let denote the algebra of (microcausal) observables equipped with a product induced by a choice of renormalization prescription (e.g., the time-ordered product ). Let be near the identity, and we write a formal expansion

with as a bookkeeping parameter. The transformed product is again associative. Expanding to first order in one obtains

where

Associativity of ∗ up to imposes the Hochschild 2-cocycle condition

i.e., with respect to the Hochschild coboundary [12]. Conversely, a Hochschild 2-cocycle determines the first-order part of an associative deformation of the product. Coboundaries correspond to trivial deformations induced by inner changes of variables; the cohomology class measures the obstruction to trivialization and is independent of the representative . We refer to this class as the algebraic curvature of the observable algebra relative to the chosen renormalization scheme.

Two structural constraints are immediate. First, the ∗-structure: to preserve at , it suffices that

Why Hochschild cohomology appears (conceptual bridge).

The appearance of Hochschild cohomology is a standard feature of associative deformation theory: infinitesimal changes of an associative product are classified by Hochschild 2–cocycle modulo coboundaries. In pAQFT, finite renormalizations act by local redefinitions (the Stückelberg–Petermann group) on the algebra of observables; expanding a scheme transformation produces the bilinear map in (2). Associativity of the transported product then implies the cocycle condition (3), while changes of representative shift by a Hochschild coboundary. Thus, packages the scheme-change data in a cohomology class rather than introducing new degrees of freedom.

Second, locality: if A and B are localized in spacelike separated regions, microcausality demands . A sufficient condition for microcausality to persist to is that whenever A and B are spacelike separated and that be local (supported on coincident configurations in the sense of microlocal analysis) [6,7,8]. We will work within the pAQFT category, where such locality conditions are natural consequences of the scaling degree bounds that govern extensions.

1.4. Interpretation as Intrinsic Algebraic Curvature

The term “curvature” is used in the following precise, algebraic sense. The family of renormalization prescriptions forms a torsor for ; infinitesimally, changes in prescription are generated by . The obstruction to trivializing the induced first-order deformation of the product is the Hochschild cohomology class . This class is invariant under changes of representative and does not depend on a particular presentation. It therefore captures an intrinsic piece of the structure of the observable algebra endowed with a renormalization-compatible product. In geometric language, plays the role of a curvature 2-form for the (flat when trivial) bundle of products over the groupoid of renormalization schemes. When , there is a cohomological obstruction to globally identifying all prescriptions by inner conjugations, and this obstruction manifests in controlled deformations of composite observables.

- What “curvature” is not

The term curvature is used here in a strictly algebraic and scheme-geometric sense. It does not refer to spacetime curvature, nor does it posit a new propagating field. Rather, measures the obstruction to globally identifying renormalization prescriptions by local inner redefinitions once locality and covariance are enforced. In this sense, it plays the role of a curvature for the “bundle of products” over the renormalization groupoid.

1.5. Relation to Known Anomaly Mechanisms

Standard quantum anomalies arise from the impossibility of simultaneously maintaining locality, covariance, and the classical Ward identities after renormalization; they therefore persist as genuine obstructions, and our framework provides an AQFT-level cohomological organization of the corresponding ambiguity data. In BRST language, anomalies are characterized by cohomology classes of local functionals obeying the Wess–Zumino consistency condition [4]. In the pAQFT setting, time-ordered products implement renormalization in configuration space, and their ambiguity is encoded by local maps acting on functionals. We will show that the first-order deviation of these maps induces a whose cohomology class maps functorially to the usual anomaly classes: axial (ABJ) [1,2], trace/Weyl [3], and (in appropriate chiral settings) gravitational [5]. The bridge proceeds through two steps: (i) an analysis of the Ward–Takahashi identities in the deformed product and their contact terms, and (ii) a comparison of the resulting cocycles with the BRST cohomology in the space of local functionals.

1.6. Ward–Takahashi Identities and Vertex Structures

Consider a conserved current associated with a gauge symmetry in the classical theory. Let denote the one-particle-irreducible (1PI) vertex function for the corresponding coupling to a Dirac field in momentum space. The Ward–Takahashi identity (WTI) reads

where S is the renormalized fermion propagator. In our framework, the deformed product ∗ modifies composite operators and thereby the definition of the vertex. At the first order in , the induced change in the vertex is linear in and can be organized as a sum of local contact terms plus terms proportional to standard form factors (e.g., Dirac and Pauli). A sufficient condition for (5) to hold to is that acts as a biderivation on the current algebra modulo local counterterms fixed by renormalization conditions; specifically, the map must intertwine with the derivations generated by the symmetry. This constraint is compatible with (4) and with locality, and it will be formulated and proved within pAQFT. The upshot is that identifiable pieces of project to the Pauli form factor (and to CP-odd dipole operators when parity is violated), providing a foothold for phenomenological correlation tests without introducing ad hoc form factors.

1.7. Phenomenological Impetus and Scope

The formalism presented here is developed with two complementary objectives. The first is to supply a mathematically controlled interpretation of renormalization ambiguities as classes in Hochschild cohomology (algebraic curvature) in a setting that is local and covariant, namely pAQFT on globally hyperbolic spacetimes [6,7,9].

All constructions use perturbative algebraic quantum field theory (pAQFT) with Epstein–Glaser renormalization on configuration space (and the locally covariant refinement of Hollands–Wald); no alternative quantization scheme is introduced.

Second, to identify robust, dimensionless correlation laws among low-energy observables that are insensitive to short-distance details once a small deformation parameter is calibrated in one channel. We will primarily consider flavor-diagonal electroweak observables where the mapping from to effective operators is under perturbative control (anomalous magnetic moments and electric dipole moments of charged leptons), postponing gravitational sectors and cosmological applications to an outlook discussion where additional scales and decoupling issues arise.

1.8. Main Contributions

- We construct, within pAQFT, a deformation of the observable product induced by infinitesimal changes of renormalization prescription and prove that is a Hochschild 2-cocycle. The cohomology class is identified as an intrinsic algebraic curvature associated with the net of local algebras.

- We establish conditions ensuring preservation of the ∗-structure, positivity on a dense domain, and locality to the first order in , and we derive a sufficient criterion for the Ward–Takahashi identities to hold up to .

- We develop a functorial bridge between and standard anomaly cohomology (axial, trace, gravitational) via the structure of time-ordered products and BRST complexes, thereby unifying several anomaly mechanisms at the algebraic level.

- We formulate dimensionless correlation relations among low-energy observables that follow from the tensorial decomposition of , and we outline how a single calibration of leads to predictions for other channels with controlled uncertainties.

1.9. Organization of the Paper

Section 2 reviews the AQFT/pAQFT setting, the microlocal framework for renormalization, and the Stückelberg–Petermann group. Section 3 introduces Hochschild cohomology and proves that renormalization-induced deformations are controlled by a cocycle . Section 4 gives explicit constructions for in free theories and discusses locality and scaling. Section 5 derives the Ward–Takahashi identities in the deformed theory and analyzes the induced vertex structures. Section 6 relates to standard anomaly cohomology. Section 7 develops phenomenological correlation relations and discusses their robustness. Section 8 discusses limitations and possible extensions. Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D and Appendix E provide technical proofs and microlocal background.

- Notation and conventions. We work in four spacetime dimensions with signature . Unless stated otherwise, . The formal parameter tracks the first-order deformation of the product induced by changes in renormalization prescription; it is distinct from any kinetic-mixing or phenomenological parameter bearing the same letter in other contexts.

For readability, the Introduction emphasizes motivation and conceptual structure; technical constructions and proofs are concentrated in later sections and appendices.

2. Preliminaries on AQFT and Renormalization Ambiguities

2.1. Local Nets, States, and Dynamics

We recall the algebraic (Haag–Kastler) framework for relativistic quantum field theory on a globally hyperbolic spacetime (in Minkowski spacetime, this specializes to the traditional axioms; in general , we adopt the locally covariant reformulation). To each causally convex region , one assigns a unital - (or von Neumann) algebra of observables such that

- Isotony: .

- Locality (Einstein causality): If (spacelike separated), then for all .

- Covariance: There exists an action of the isometry group (Poincaré in Minkowski) by automorphisms with .

- Time-slice axiom: If O contains a Cauchy surface for , then .

A state is a positive, normalized linear functional ; the GNS construction yields a representation . In Minkowski space, physically relevant local algebras are typically of type III, whereas the perturbative constructions used below yield topological ∗-algebras completed with respect to Hadamard two-point functions [6,7,13,14].

2.2. Microcausal Functionals and the Free-Field Star Product

Let denote a suitable space of classical field configurations (e.g., smooth sections of a vector bundle). A local functional is of the form with an f polynomial in jets and compactly supported. Its n-th functional derivative satisfies microcausality if

i.e., its wavefront set avoids unions of future/past lightcones in each cotangent factor [6,7,15]. The space of microcausal functionals is stable under a pointwise product and functional differentiation.

Fix a Hadamard two-point function for the free field; define the bidifferential operator

Then, the (normal ordered) free-field star product on is given by

where is the pointwise multiplication and the brackets denote the distributional pairing (well-defined by Hörmander’s criterion and microcausality). The resulting topological ∗-algebra depends on the choice of by an inner (coherent-state) equivalence; observables are thus defined modulo this equivalence [6,7].

2.3. Time-Ordered Products and Causal Factorization

Interacting observables are constructed from time-ordered products

satisfying axioms of symmetry, causal factorization, unit, microlocal spectrum condition, covariance, scaling degree bounds, and field independence [6,7,8,9,16]. Causal factorization reads as follows: if for all (i.e., all points in are not later than any in ), then

For free fields, a compact formula is

where is the Feynman propagator (Hadamard parametrix with -prescription). Interactions are introduced via the Bogoliubov S-matrix

and the relative S-matrix

The interacting (retarded) field is obtained by functional differentiation at zero coupling:

Causal factorization of T ensures the Bogoliubov causality of , while the time-slice axiom holds provided T is constructed covariantly and locally [6,9,14].

2.4. Microlocal Extension and the Epstein–Glaser Program

The inductive construction of (Epstein–Glaser) reduces to extending distributions defined on configuration space with thin diagonals removed to distributions supported also on the diagonals, under control of scaling degrees. Here, configuration space refers to for n insertions; “coincident points” correspond to the thin (partial) diagonals where one or more insertion points coincide, i.e., loci of the form . The extension ambiguity is supported on these diagonals and is controlled by the scaling degree. Let ; its (Steinmann) scaling degree at the origin is

Theorem 1

(Extension with minimal scaling degree [8,17]). If has a finite scaling degree , then there exists an extension with . If , the extension is not unique; the ambiguity space is finite-dimensional and spanned by derivatives with .

In the EG recursion for , the singular distributions arise from concatenations of Feynman propagators on configuration space. The theorem implies the following:

- Existence: exists for all n with the stated axioms, by induction on n.

- Locality and covariance: If the choice of extension is local and covariant (in the sense of natural transformations under embeddings of spacetimes), then so is [6,8,14,18].

- Finite renormalization freedom: At each order, ambiguities correspond to local counterterms supported on diagonals, with the dimension bounded by the degree of divergence .

Thus, renormalization is precisely the freedom of extension at coinciding points, controlled by scaling degree and microlocal spectral properties (Hadamard condition) [6,19].

2.5. Normalization Conditions and Renormalization Schemes

To fix uniquely, one imposes normalization conditions (in the spirit of EG/Scharf):

- N0.

- Symmetry: is symmetric in its arguments.

- N1.

- Causal factorization (as above).

- N2.

- Unit: and for linear F.

- N3.

- Covariance: is natural with respect to isometries/embeddings.

- N4.

- Microlocal spectrum: wavefront set bounds are consistent with Hadamard structure.

- N5.

- Scaling: scaling degree bounds are compatible with canonical dimensions.

- N6.

- Unitarity: (causal unitarity).

- N7.

- Field independence: functional derivatives commute appropriately with .

Different choices of extensions consistent with N0–N7 define distinct renormalization schemes. The space of schemes is an affine space modeled on local counterterms (polynomial in fields and derivatives) graded by canonical dimension or scaling degree.

2.6. The Stückelberg–Petermann Renormalization Group

Let be the space of local functionals. The Stückelberg–Petermann group is the group of formal, local redefinitions of the form

compatible with support, covariance, and degree (it acts as a formal diffeomorphism on the space of interactions). The Main Theorem of Renormalization in the causal framework can be stated as follows:

Theorem 2

(Main theorem, causal version [10,11]). Let T and be two time-ordered product families satisfying the axioms N0–N7. Then there exists a unique such that the corresponding Bogoliubov S-matrices obey

Moreover, the composition of renormalization schemes corresponds to the composition in .

In particular, the physical content encoded by relative S-matrices is invariant under Z, while individual composite operators transform covariantly. The difference between schemes appears as local reparametrizations of couplings and fields, and as finite redefinitions of composite operators. This group-theoretic structure will be the starting point for our algebraic deformation analysis.

2.7. Retarded Products and the Algebra of Interacting Observables

Define the multilinear retarded products by

They satisfy causal support properties: and obey combinatorial identities mirroring BPHZ forests but formulated in configuration space [6,16]. The interacting algebra generated by (for a fixed interaction V) inherits the net structure and the time-slice property from , and its dependence on the renormalization scheme is governed by as above.

2.8. Example: in Four Dimensions

For concreteness, consider the scalar model with . Power counting gives a degree of divergence for a graph with loops L and internal lines I. In EG language, the singular part at order n is supported on the union of partial diagonals in ; scaling degree bounds restrict the ambiguity to local counterterms of the schematic form

with coefficients polynomial in and distributions built from curvature if is curved (local covariance). Changing the scheme amounts to acting by some that reparametrizes and modifies composite operators (e.g., Wick powers) by local terms, consistent with Hollands–Wald’s classification of Wick polynomials [8,9].

2.9. Summary of Structural Consequences

The EG/pAQFT framework yields the following:

- A functorial assignment with time-ordered products encoding interactions and retarded products encoding dynamics.

- A finite-dimensional space of renormalization ambiguities at each order, localized on diagonals and controlled by scaling degree.

- A global, group-theoretic organization of scheme changes via , acting by formal local redefinitions on interactions and composite operators.

In Section 3, we will use these facts to identify the first-order effect of a scheme change with a Hochschild 2-cocycle that controls an associative deformation of the observable product. The associated cohomology class will be our algebraic curvature.

3. Algebraic Curvature as Hochschild Cohomology

3.1. Hochschild Cochains, Differential, and Gerstenhaber Bracket

Let be a (topological) associative ∗-algebra over with multiplication , . The space of n-cochains consists of continuous n-linear maps (with ). The Hochschild differential is

One verifies ; the Hochschild cohomology is with and [20,21].

The space (degree shifted by ) carries the Gerstenhaber bracket that turns it into a graded Lie algebra [12,22]. For , ,

The associative product m is a 2-cochain obeying . The Hochschild differential is , so by graded Jacobi.

3.2. First-Order Deformations and Classification by

A formal associative deformation of m is a -bilinear product

with , such that in . Expanding the associativity constraint order-by-order yields the Maurer–Cartan tower

Thus, a necessary and sufficient condition for a first-order associative deformation is that be a Hochschild 2-cocycle. Two first-order deformations and are equivalent if there exists a formal automorphism with such that

Hence, equivalence classes of first-order associative deformations are classified by [12,23,24]. In geometric language, the moduli of associative structures modulo inner equivalence has tangent space at m.

3.3. Scheme Changes ⇒ Hochschild 2-Cocycles

Let T be a fixed renormalization prescription (family of time-ordered products) in pAQFT and let be the Stückelberg–Petermann group of local, formal redefinitions acting on interactions and composites. For close to the identity, define a new product on by transport of structure

where · denotes the original product (time-ordered or otherwise) associated with T. Writing , a direct calculation gives at first order

Proposition 1

(Cocycle property of ). The bilinear map ω in (14) obeys . Moreover, if with , then . Hence, the cohomology class is well-defined by the scheme-change orbit of T.

Sketch.

Associativity of implies at , i.e., , which is by the identity . Under with a derivation-like 1-cochain, (14) shifts by exactly as in the standard deformation equivalence. □

We call the algebraic curvature associated with the renormalization class of T. It is intrinsic up to inner equivalences generated by 1-cochains and, crucially, is local in the sense explained below.

3.4. Locality, ∗-Structure, and Microcausality at First Order

In AQFT/pAQFT, one requires that composite operations be local and respect the causal structure. Let be generated by microcausal functionals; locality of means that depends on the jets of at coincident points and is supported on the diagonals of configuration space (as a distribution-valued bidifferential operator).

Proposition 2

(Locality and microcausality). Suppose ω arises from a renormalization scheme change Z that preserves the microlocal spectrum condition and naturality under embeddings (locally covariant). Then ω is supported on the diagonals and is a local bidifferential operator of finite order (bounded by scaling degree). In particular, if A and B are localized in spacelike separated regions, then implies .

Sketch.

In the Epstein–Glaser construction, ambiguities at order n are linear combinations of derivatives of delta distributions supported on partial diagonals, multiplied by local polynomial functionals with bounded scaling degree [8,17,25]. The induced first-order change is local and respects causal factorization; therefore, computed from (14) inherits locality and finite order. Spacelike commutativity persists because the support properties forbid nontrivial contributions when arguments are causally disjoint to first order. □

The ∗-structure imposes the compatibility condition

This holds provided intertwines the adjoint (causal unitarity) [9,16].

Remark 1

(Positivity to first order). Let φ be a positive, continuous state on . If ω satisfies (15) and is bounded on the relevant dense domain, then for sufficiently small ε one has on that domain, i.e., quasi-positivity to first order. In our perturbative context, observables are formal power series and positivity is interpreted order-by-order [7].

3.5. Explicit Local Form of in pAQFT

Let T and be two time-ordered products obeying the pAQFT axioms. Their difference at order n is supported on the union of partial diagonals in and has the general form

with local coefficients constrained by scaling. Specializing to and transporting via (14), one obtains the typical structure

where are locally and covariantly constructed from the metric and coupling constants (and curvature if is curved). Equation (17) makes explicit that is local and supported on coincident configurations. The “higher functional-derivative terms” appear when involves field redefinitions of order in the fields.

3.6. Biderivations and Ward Identities at

For later use (vertex analysis), it is convenient to single out a class of that act as biderivations modulo local contact terms:

Such a property holds if is (to first order) a derivation with respect to the product modulo local counterterms fixed by normalization conditions (N0–N7). In pAQFT this amounts to the field independence and covariance of T and the naturality of Z [7,11]. When (18) is satisfied, the deformation of the Noether current algebra respects the Ward–Takahashi identities to first order after appropriate redefinition of local counterterms (Section 5).

3.7. Comparison with Standard Deformation Quantizations

It is instructive to contrast the present deformation with classical star products from deformation quantization. If is a Poisson manifold, a formal star product is

with bidifferential operators and [26,27,28]. In that setting, detects infinitesimal classes of associative deformations compatible with the Poisson bracket and is related to Poisson cohomology. In our AQFT/pAQFT context, the algebra is noncommutative from the outset; the deformation parameter tracks renormalization-scheme changes rather than quantization, and the corresponding is local (supported on diagonals).

On the -algebraic side, Rieffel deformation by an -action produces associative star products that notoriously preserve the -norm and positivity [29]. Net-level implementations (warped convolutions) yield wedge-local quantum fields [30,31]. Our can be viewed as the formal, local, configuration-space analogue driven by the renormalization-group torsor rather than by an external group action.

3.8. Summary of the Cohomological Picture

The discussion above establishes the following chain:

4. Explicit Constructions of the Cocycle

In this section, we construct the first-order deformation cocycle explicitly in perturbative AQFT. We begin by displaying as the differential of an infinitesimal Stückelberg–Petermann map acting on local functionals and then work out concrete formulas for free scalar and Dirac fields. We emphasize locality (support on diagonals), covariance, scaling-degree bounds, and the compatibility with the ∗-structure. Finally, we indicate conditions for nontriviality of within natural subcategories of local, covariant cochains.

4.1. Renormalization Maps as Local Differential Operators

Let denote the space of local functionals (polynomial in jets, compactly supported). A renormalization prescription T (family of time-ordered products) induces a product on an algebra generated by microcausal functionals. A change of prescription is encoded by (Main Theorem), i.e., a formal, local and covariant redefinition acting functorially under isometric embeddings [7,11]. We write

where values are local differential operators of total jet-order acting on the integrands of local functionals, and the coefficients are locally and covariantly constructed from the background (metric, couplings, curvature) with definite scaling dimension; R and are bounded by the scaling-degree constraints of the Epstein–Glaser extension at the order considered [8,9,25].

Transport of structure (Section 3) yields the deformed product

with and independent of the representative modulo 1-cochains. Since is local and covariant, is a local bidifferential operator supported on coincident configurations (partial diagonals) and bounded in order by the same scaling-degree estimates.

4.2. Scalar Fields: Wick Monomials and Time-Ordered Products

Consider a real free Klein–Gordon field on a globally hyperbolic spacetime , with Hadamard two-point function and Feynman parametrix . For compactly supported test functions , define Wick monomials (with respect to )

where the normal ordering is given by the free-field star product [6,7]. The time-ordered product of local fields is built from and extended to partial diagonals by the Epstein–Glaser recursion subject to the local covariance and scaling-degree constraints [8,9].

- A worked example:

On (for concreteness), Wick’s theorem gives the point-split form

The last term is a distribution singular as with scaling degree 4; its extension to the diagonal is not unique. Minimal scaling-degree extension is unique up to local counterterms supported on :

with constants (in curved backgrounds, the values are replaced by local curvature polynomials). Changing the extension by produces a shift in by a local term:

where denotes the unit. Interpreting this change via (21), we obtain the corresponding contribution to :

Thus, is explicitly a local bidifferential operator of finite order, supported on the diagonal, with coefficients fixed by the (finite) extension freedom. By construction, , and the class is independent of the presentation of .

- Further scalar examples.

For mixed monomials such as , one obtains

and the extension ambiguity resides in the term when . A change of extension yields

again manifestly local. Analogous formulas hold for higher-degree monomials, with the highest number of derivatives determined by the scaling degree of the singular kernel entering the unextended product; the coefficients depend polynomially on couplings and (in curved backgrounds) on curvature scalars [8,9].

Proposition 3

(Locality, covariance, and order bounds). For scalar Wick monomials, the cocycle ω determined by any change of extension in the Epstein–Glaser construction has the form of a finite sum of terms like (25)–(27), i.e., a local bidifferential operator supported on the diagonal with total derivative order bounded by the degree of divergence of the unextended kernel. The coefficients are locally and covariantly constructed (curvature polynomials on curved spacetime).

Sketch.

The statement is a direct consequence of the microlocal spectrum condition and scaling-degree bounds for the distributions entering , combined with the structure theorem for extensions (Section 2.4) and the naturality requirement under embeddings [6,8,9]. □

4.3. Dirac Fields: Currents and Spinor Bilinears

Let be free Dirac fields on (possibly coupled to smooth background gauge and Yukawa fields). The algebra of microcausal functionals and the classification of Wick powers/time-ordered products are developed in [32,33]. Denote by the Dirac Feynman parametrix. Consider the vector current and the spinor field ; by fermionic Wick calculus,

The second term exhibits a short-distance singularity of the universal Hadamard form; differentiation with respect to x followed by the limit produces local, covariant contact terms. Changing the extension of (28) at the diagonal yields the general local form

and similarly for . For current–current products,

the extension ambiguity lies in the last trace term; a change in extension produces

with being local and covariant (built from -matrix traces and background fields). The structures (29)–(31) are again local bidifferential operators supported on the diagonal and of finite order fixed by scaling degree [33]. They will feed directly into the vertex analysis and Ward identities (Section 5).

4.4. Curved Backgrounds and Curvature Dependence

On a general globally hyperbolic spacetime, Hadamard parametrices have the universal form

with smooth obtained locally and covariantly from the metric (and bundle data), and the signed geodesic squared distance with -prescription. Products such as and admit scaling expansions whose extensions differ by curvature polynomials multiplying delta and its derivatives [34,35]. Consequently, the coefficients in (20) and the constants (25), (29), (31) become curvature-dependent (e.g., involve R, and their derivatives) with dimensions fixed by the scaling degree. This is the precise sense in which is locally and covariantly constructed.

4.5. Compatibility with the -Structure and Microcausality

If Z is chosen to preserve causal unitarity (normalization N6) and field independence (N7), then intertwines the ∗-operation and one has

as required for to hold at [9,16]. Microcausality is preserved to the first order because the support of is confined to diagonals (Proposition 3); hence, if , then .

4.6. Associativity Check on Generators

Although associativity to is guaranteed by , it is instructive to verify it directly on generators. Let . Using (25)–(27) and the combinatorics of Wick contractions, it follows that

because the only nonzero contributions at first order would arise from two contact singularities simultaneously—which are absent in the first-order perturbation of by construction (the ambiguity enters only at higher orders in the Stückelberg–Petermann expansion). The same holds in the Dirac sector using (29)–(31).

4.7. On the Nontriviality of

Within the class of local, covariant 1-cochains of bounded differential order (consistent with the normalization N0–N7), not every local contact shift (25)–(31) can be written as . For instance, the identity contribution in (25) proportional to cannot be generated by a that preserves the engineering dimensions of Wick polynomials and respects field independence. Indeed, is a linear combination of and , which, under the stated constraints, cannot reproduce a pure multiple of the identity with the derivative structure required by (25). A similar obstruction appears in the current sector (31), where the symmetric tensor defines a central term in the current algebra that cannot arise from a derivation-like consistent with covariance and scaling. These observations, together with the classification results for Wick powers and time-ordered products [8,9,33], provide explicit examples where in the subcategory of cochains compatible with the AQFT axioms. (We stress that this is a statement about nontriviality within the natural class of local, covariant cochains of bounded order; without such restrictions, continuous Hochschild cohomology of certain - or von Neumann completions may be trivial. Our setting is the perturbative, microlocal algebra of local fields.)

4.8. A No-Go Lemma for Trivialization by Local 1-Cochains

We now formalize the claim that the scalar and current central terms identified in Equations (25) and (31) cannot arise as Hochschild coboundaries of any admissible local 1-cochain compatible with our axioms. The proof isolates precise hypotheses on the allowed and then uses a filtration by Wick degree together with the unit and field independence normalizations to rule out pure central outputs.

- Set-up and notation.

Let be the topological ∗-algebra generated by Wick powers (scalar and Dirac sectors) on a globally hyperbolic spacetime, completed as in Section 2. Denote by the Wick degree (number of fields in the normal-ordered monomial); for instance, , , etc. Let be the projection onto the central (multiple-of-the-identity) component defined by the vacuum two-point structure used for normal ordering (equivalently, the map extracting the coefficient of in the Wick expansion). For , write

- Admissible local 1-cochains.

We call a linear map admissible if it satisfies

- (L1)

- Locality and covariance: is given on local generators by a finite sum of differential operators on the test function jets with locally covariant coefficient tensors (as in (20)). In particular, is contained in and is natural under isometric embeddings.

- (L2)

- Unit and field independence: and commutes with functional differentiation on microcausal functionals in the sense induced by the normalization N7 of time-ordered products (no explicit dependence on external test functions beyond the functional’s integrands).

- (L3)

- Filtration (no degree drop to 0): For any W with , the central component of vanishes, i.e., . Equivalently, whenever .

- (L4)

- Scaling bound: respects the scaling-degree bounds implied by the EG extension at the order considered (so the total derivative order is bounded by the degree of divergence, as in Proposition 3).

Conditions (L1)–(L2) are the 1-cochain analogues of our renormalization axioms (N0–N7), in particular, the unit and field independence normalizations ensure that annihilates constants and introduces no spurious nonlocal dependence. (L3) encodes that admissible finite renormalizations cannot turn nontrivial Wick polynomials into pure c–numbers; it is the standard filtration property for local redefinitions consistent with the Hollands–Wald classification of Wick polynomials. (L4) matches the microlocal scaling bounds.

Lemma 1

(No central coboundary from admissible ). Let η be an admissible local 1-cochain. Then, for any with and ,

In particular, for and , one has

so cannot reproduce the central contact structure of Equation (25). Likewise, for and , one cannot obtain the central tensor structure of Equation (31) from any admissible η.

Proof.

We take central parts with and use linearity:

By (L3), and for . Since multiplication by B (resp. A) cannot create a central component out of a noncentral element in the Wick filtration (equivalently, if X has vanishing central part, then so do and when , because any central component would require full Wick contraction with a c–number kernel independent of the fields, which is excluded by (L2)–(L3)), we get . Thus,

Decompose into its Wick expansion. Write , where has strictly positive Wick degree and is a local distribution built from the parametrix contractions (for the pairs considered, this is exactly the -type object whose EG extension produces the central contact terms). Applying and using linearity,

The first term vanishes by (L3), because implies . For the second term, (L2) (unit and field independence) gives and forbids a nontrivial action of on pure c–number multiples of the unit beyond differential relabelings already absorbed in ; combined with (L1)–(L4), this yields . Hence , and (33) follows. □

Remark 2

(Consequences for the cocycle class). Lemma 1 shows that the central bidistributions appearing in (25) and (31) cannot be written as with η admissible. Therefore, within the local, covariant subcomplex singled out by (L1)–(L4), the cocycle ω obtained from EG extension differences has a nontrivial central projection in . In particular, the algebraic curvature class is nonzero in this subcomplex whenever those central pieces are present.

Remark 3

(On the hypotheses). Hypothesis (L3) is the filtration statement one expects from the Hollands–Wald classification of Wick polynomials: admissible finite renormalizations map Wick powers to linear combinations of Wick powers of nonnegative degree with local differential operators on the smearing and do not collapse a nontrivial Wick monomial into a pure c-number. Hypothesis (L2) imports the unit and field independence normalizations (N2, N7) at the level of η, ensuring and excluding spurious test function dependence. Both are satisfied by the Stückelberg–Petermann maps used elsewhere in this section.

4.9. Summary

We have exhibited explicitly as a local, covariant bidifferential operator supported on diagonals, derived from the finite extension freedom in (and, mutatis mutandis, higher ). For scalar and Dirac fields, we displayed the structure of on a set of generators (Wick monomials and currents). The resulting cocycle preserves the ∗-structure and microcausality to first order and is, under natural constraints, cohomologically nontrivial. These constructions form the concrete backbone for the Ward identity analysis and for the anomaly/cohomology bridge developed in the next section.

5. Ward–Takahashi Identities and Deformed Vertices

In this section, we establish that the deformation of the observable product

constructed in Section 3 and Section 4, is compatible with gauge-current conservation and Ward–Takahashi identities (WTIs) at first order in under natural locality and biderivation hypotheses on . We then compute the induced structure of the vertex function for a Dirac field minimally coupled to a background, showing how the transverse (gauge-invariant) form factors are controlled by the tensorial decomposition of , while the longitudinal part remains fixed by the WTI to . Finally, we comment on the non-Abelian/BRST generalization.

5.1. Setup: Background-Coupled Current and Relative S-Matrix

Let denote the conserved Noether current of a Dirac field for a gauge symmetry in the free theory. We regard an external gauge potential as a classical background and introduce the coupling via the local functional

In the pAQFT framework reviewed in Section 2, interacting (retarded) fields are defined with the relative S-matrix

where T is a fixed time-ordered product obeying the axioms. Gauge variations induce functional identities for that are equivalent to the WTIs for time-ordered products with current insertions [7,16].

We now change the product on the algebra of microcausal functionals by the deformation ∗ induced by a scheme change , as in (21). We write for the time-ordered maps constructed from the same renormalization prescription but with a product * used to concatenate factors (equivalently, we transport the old T through Z; all constructions remain local and covariant at ). We emphasize that and the associated retarded products differ from T by local contact terms controlled by and preserve causal factorization at first order.

5.2. Master Ward Identity at First Order

Let be a tensor of local functionals with pairwise disjoint supports. In the undeformed theory, one has the familiar current Ward identity (distributionally)

where is the infinitesimal gauge variation acting on and ; the right-hand side collects the standard contact terms at coincident points [16,36,37]. We say that a bilinear map is a biderivation modulo local contact terms if it satisfies (18).

Proposition 4

(Master Ward Identity to ). Assume ω is local, supported on partial diagonals, and a biderivation modulo local contact terms. Then

where is a local, covariant functional (polynomial in jets of the ) supported on the diagonals . Equivalently, the violation of the naive Leibniz rule introduced by ω is absorbed into contact terms that preserve the distributional WTI structure.

Sketch.

Write and expand the left-hand side. By Section 4, the first-order change is a finite sum of distributions supported on diagonals, with coefficients built locally and covariantly from the background. Differentiation with respect to x preserves this support. The biderivation property (18) ensures that away from diagonals (i.e., for mutually disjoint points), the Leibniz rule holds and the current remains conserved at order ; therefore, any deviation must be a sum of contact (delta and derivatives) terms, which we package into . Local covariance follows from that of Z and of the EG extension. □

5.3. Normalization of Contact Terms in the Ward–Takahashi Identity

Proposition 4 showed that the deformed time–ordered products obey the Master Ward Identity up to a local contact insertion supported on diagonals. In the AQFT framework, one interprets these contact terms as renormalization ambiguities of the current operator itself, to be fixed by suitable normalization conditions. We now spell out precise hypotheses under which the offending term can be removed once and for all by current improvement and field renormalization.

Lemma 2

(Normalization of contact terms in the WTI). Let ω be a local Hochschild 2 cocycle satisfying the biderivation–mod–contacts property (18). Then there exist renormalizations

- (i)

- A redefinition of the current by a local improvement term

- (ii)

- A finite wavefunction renormalization of the Dirac field,

such that the contact term in (36) vanishes identically at , i.e., the renormalized current and field ψ satisfy the clean Ward–Takahashi identity

for all local tensors .

Sketch of proof.

The local contact term obtained in Proposition 4 is a sum of distributions supported on the diagonals with coefficients that are local polynomials in the background fields and jets of the . By covariance, they can only arise from (i) improvement terms of the current () and (ii) local multiplicative renormalization of the matter field entering .

Indeed, (i) accounts for derivative-type contact terms proportional to total derivatives of delta functions. Choosing appropriately absorbs these into the definition of the current. (ii) accounts for contact terms proportional to or , which are removed by a finite rescaling of . Since is local and a biderivation modulo contacts, no further structures are possible at . Thus, all contact contributions can be absorbed into the pair , yielding the clean WTI (39). □

Remark 4.

This is the rigorous AQFT analogue of the usual textbook statement that conservation of the renormalized current can be restored by a suitable choice of finite counterterms and field renormalization. Here it appears as a structural consequence of locality and the biderivation property of ω.

Corollary 1

(Charge action as a derivation to first order). Let with f compactly supported on a Cauchy surface. Then for observables localized in the support of f, one has

i.e., the charge acts by derivations on up to (and local contact terms).

This corollary encodes the algebraic content of the WTI at first order: the symmetry is compatible with the deformed product to the extent that is a biderivation modulo local counterterms.

5.4. Momentum Space WTI and the Vertex Decomposition

We now pass to momentum space in Minkowski spacetime to extract the vertex function. Define the Fourier transform conventions

Let be the exact (two-point) propagator in the deformed theory, i.e., the Fourier transform of , and let be defined by the amputated three-point function with one current insertion,

Transforming (36) and using standard manipulations yields the momentum-space WTI

where is a polynomial in external momenta originating from the Fourier transform of . As it is a local polynomial, it can be absorbed into a redefinition of local counterterms (field renormalizations and improvement terms in the current). Upon imposing a standard renormalization condition for the current, we set henceforth and obtain the familiar WTI to :

5.5. How Feeds the Transverse Form Factors

The explicit local forms (29)–(31) imply that the first-order change of three-point functions with one current insertion is a sum of contact contributions and terms with the tensor structures of Pauli and electric–dipole operators. Schematically, from (29), one finds (suppressing polynomial contact pieces)

with scalar form factors determined by the -coefficients and after amputation and renormalization. The WTI (42) enforces the relation between and the self-energy; thus, the independent deformations at the first order reside in

In particular, the anomalous magnetic moment shift is

and (if CP is violated by the -tensor structure) the electric dipole moment is

Equations (46) and (47) provide the desired linear map from the algebraic cocycle data to measurable transverse vertex deformations.

5.6. CP, P, and T Properties of

Decompose the cocycle into CP-even and CP-odd parts, , according to its action on spinor bilinears. For instance, an proportional to is CP-even, while a component proportional to is CP-odd. Then,

to the first order. This dichotomy follows from the transformation properties of the Dirac bilinears and the fact that the WTI constrains only the longitudinal part, leaving the transverse CP-odd/even sectors available for deformation. The local, covariant structure of (Section 4) ensures that these statements are independent of the regularization scheme.

5.7. Example: Contact Terms and On-Shell Normalization

To make the handling of the -term in (41) explicit, consider the typical contact contribution arising from (29) with :

Fourier transforming and amputating yields a term in proportional to . Its divergence is a polynomial in external momenta and can be absorbed by imposing the on-shell renormalization condition and by choosing a conserved improved current (if desired) via the usual freedom to add total derivatives to . This implements in (41) without affecting the transverse form factors.

5.8. Comparison with Standard Star-Product Models

In Moyal-type noncommutative QFT, the star product is defined from a constant Poisson bivector and produces momentum-dependent phases in vertices while preserving the Ward identity because derivations with respect to the Moyal product are inner and satisfy Leibniz rules [26,29]. In our setting, the deformation arises from the Stückelberg–Petermann torsor and is local (supported on diagonals); nevertheless, the biderivation property (18) plays the same structural role and suffices to ensure the WTI to after appropriate normalization. The crucial difference is that our is not tied to a global Poisson structure but to renormalization ambiguities organized cohomologically; its physical imprint is therefore concentrated in transverse, local operator mixings (Pauli and EDM) rather than in nonlocal phase factors.

5.9. BRST/Slavnov–Taylor Generalization

For non-Abelian gauge theories, the WTIs are replaced by Slavnov–Taylor (ST) identities, most naturally encoded in the BRST framework. Let s be the BRST differential acting on the algebra of fields and antifields. In the pAQFT setting, the Master Ward Identity (MWI) expresses s-invariance of the generating functional up to local anomalies characterized by the BRST cohomology in ghost number one [7,38]. If is chosen to respect the biderivation property with respect to the BRST differential (modulo local counterterms), then the ST identity holds to with possible local breaking terms entirely controlled by the same cohomology class that will appear in the anomaly bridge of the next section. Thus, the present Abelian analysis extends verbatim to the BRST setting at the first order.

5.10. Summary

We have shown that (i) the current WTIs survive the first-order product deformation induced by , up to local contact terms that can be fixed by normalization, and (ii) the transverse part of the vertex—which encodes the Pauli and electric–dipole operators—receives linear, calculable corrections determined by the tensorial decomposition of . Equations (42) and (43) and the maps (46) and (47) provide the algebraic bridge between cohomological curvature and measurable low-energy form factors.

6. Anomalies from Algebraic Curvature: The BRST/BV Bridge

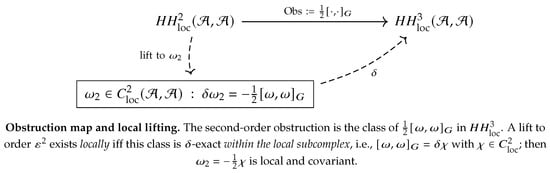

In this section, we connect the first-order deformation class of Section 3 and Section 4 with the standard cohomological classification of anomalies. We work in the BRST/BV framework and the perturbative-algebraic setting of time-ordered products. Our main statements are (i) the deformed product ∗ induces, via the (anomalous) Master Ward Identity, a local anomaly insertion that solves the Wess–Zumino (WZ) consistency condition; (ii) the assignment defines a canonical homomorphism

where is the local BRST cohomology (ghost number 1, form degree d); (iii) intertwines trivial deformations with trivial anomalies, and is compatible with renormalization-group redefinitions; (iv) in examples, the image of reproduces the known gauge (ABJ), mixed, and Weyl anomalies.

6.1. Local BRST Bicomplex and Wess–Zumino Consistency

Let denote the graded-commutative algebra of local forms built from fields, antifields, ghosts and finitely many of their derivatives (jets). The BRST differential s increases the ghost number by and implements gauge symmetry; the exterior derivative d increases the form degree by . The pair defines a bicomplex, and anomalies are classified by the local cohomology

where is the consistent anomaly density and the associated descent form [39]. Equivalently, if W is the generating functional, the WZ condition reads

encoding and defining [4,40,41,42]. In even spacetime dimension , solutions descending nontrivially are generated by the Chern–Weil polynomial through the Stora–Zumino descent; for conformal (Weyl) symmetry, the solutions split into type A (Euler density) and type B (Weyl invariants) [43].

6.2. Anomalous Master Ward Identity in pAQFT

Let T be a renormalized family of time-ordered products fulfilling the pAQFT axioms, and let be the corresponding family for the deformed product . The (anomalous) Master Ward Identity (MWI) expresses the BRST variation of time-ordered products in terms of local insertions [44,45]:

where X is a tensor of local functionals and is a local, covariant map supported on diagonals. At the first order in , one has

Nilpotency of s together with causal factorization implies the WZ condition for ; thus, the coefficient density defined by pairing with background sources is a representative of a class in .

6.3. Constructing the Anomaly from the Cocycle

Let be a local Hochschild 2-cocycle () arising from a Stückelberg–Petermann change of scheme (Section 4 and Section 5). For a collection of local functionals with mutually disjoint supports, one defines

where and denote the obvious insertions at the k-th (or -th) slot and collects the contact terms generated by the biderivation property of (Section 4). (Equation (49) is the abstract form of the first-order contact insertions computed in Section 4; for explicit scalar and Dirac examples see (25)–(31).) Transporting (49) through the -map yields the insertion in (48).

Proposition 5

(WZ consistency from Hochschild closedness). Assume ω is local, covariant, and a biderivation modulo local contact terms. Then the associated insertion satisfies

for some local , i.e., the corresponding density obeys . In particular, determines a well-defined class .

Sketch.

By (48), yields

Using locality/biderivation of and causal factorization, the second term is a total derivative acting on local polynomials built from the jets of X; these assemble into . The first term then enforces . The assumption is precisely the associativity that underlies the graded Jacobi identity needed to close the descent. □

Proposition 6

(Trivial deformations give trivial anomalies). If is Hochschild-exact with η local and covariant, then for some local , hence in .

Sketch.

Writing in (49) and using the Leibniz rule for s together with causal factorization shows that is a BRST coboundary modulo d of a local functional depending on . □

6.4. Definition of the Local Hochschild Complex and Construction of

We now make precise the domain and codomain of the map

constructed informally in the previous subsections. The key ingredients are (i) the local Hochschild cochain complex for the algebra of observables in pAQFT and (ii) the anomalous Master Ward Identity that produces a BRST anomaly density from a Hochschild 2-cocycle.

- Local Hochschild complex.

Let be the algebra generated by microcausal functionals on a globally hyperbolic spacetime , as in Section 2. We define the graded vector space of local Hochschild n–cochains by

where

- Continuity is with respect to the locally convex topology on induced by the wavefront set seminorms on functional derivatives [6,7].

- Locality means, for with mutually disjoint supports, ; equivalently, is supported on the total diagonal in configuration space.

- Covariance means is natural under embeddings of spacetimes , in the sense of locally covariant QFT [14]. In particular, for isometries h.

The Hochschild differential is the usual

It is straightforward to check that maps to , so is a subcomplex of the full Hochschild complex. We denote its cohomology by .

- Definition of .

Let , with a local 2–cocycle (). Construct the deformed product and corresponding deformed time–ordered products by transport of structure. The anomalous Master Ward Identity (MWI) then produces, to first order in ,

with a local insertion supported on diagonals (Section 6.3). Pairing with background ghost sources yields a local anomaly density of ghost number 1 and form degree d, i.e., a representative in . We define

- Well-definedness on cohomology.

Proposition 7.

The map Φ is well defined on cohomology:

- (i)

- If with , then for some local , hence .

- (ii)

- If T and are two renormalization schemes related by a Stückelberg–Petermann map Z, their cocycles lie in the same cohomology class and .

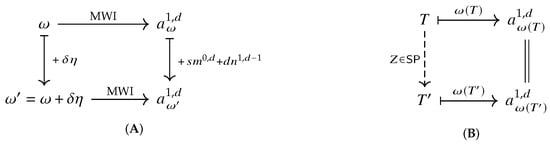

The following commuting diagrams (Figure 1 and Figure 2) summarize Proposition 7: independence of representative and independence of renormalization scheme within the Stuckelberg–Petermann orbit.

Figure 1.

Commutativity expressing the well-definedness of on cohomology classes and its independence of the renormalization scheme. (A) Coboundary invariance. Changing the representative shifts the anomaly density by BRST- and d-exact terms. Hence, and . (B) Scheme invariance. If is obtained from T by a Stückelberg–Petermann map Z, then in the local complex; therefore and .

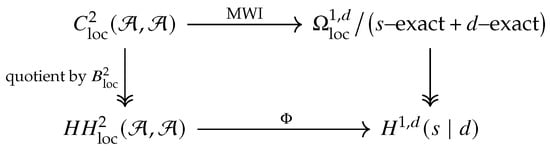

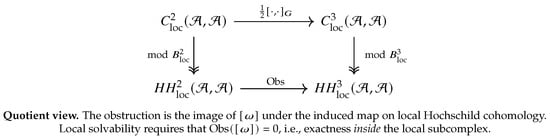

Figure 2.

The map factors through the quotient by local Hochschild coboundaries on the domain and by BRST- and d-exact representatives on the codomain; the top arrow is induced by the anomalous MWI.

Sketch.

(i) If , then the corresponding insertion differs from by s- and d-exact local terms (see Proposition 6), so they define the same class in . (ii) The Main Theorem of Renormalization (Section 2.6) shows is obtained from T by a local SP map. At first order, this changes by a coboundary in and hence does not affect . □

- Homomorphism property.

Proposition 8.

The map Φ is a homomorphism of Abelian groups: .

Proof.

Linearity in of both the deformation and the induced insertion implies up to s- and d-exact terms, so cohomology classes add linearly. □

- Functoriality under embeddings.

Proposition 9.

The assignment is a natural transformation with respect to embeddings in the category of globally hyperbolic spacetimes. In particular, if is an embedding, then

where is the induced morphism of observable algebras.

Sketch.

Locality and covariance of (by definition of ) imply naturality of the deformation under embeddings. Since the anomalous MWI is functorial in the choice of background, the anomaly density transforms covariantly as well. Thus, commutes with . □

- Summary.

We have now defined rigorously, proved that it is well defined on local Hochschild cohomology, linear, and functorial with respect to spacetime embeddings. This makes precise the central claim of this section: an intrinsic algebraic curvature class canonically determines a BRST anomaly class in .

6.5. Gauge, Mixed, and Weyl Anomalies

- Abelian and non-Abelian gauge anomalies.

For a chiral Dirac field, the current sector of (Section 4.3) produces, via (49), a density proportional to the invariant polynomial in (with ghost C and curvature F), i.e., the standard consistent anomaly class. Adding the Bardeen–Zumino polynomial corresponds to changing the representative by d-exact terms, leaving the cohomology class unchanged [40]. The Fujikawa Jacobian realizes the same class at the path-integral level [46,47]. In particular, vanishes precisely when the usual representation-theoretic conditions for anomaly cancellation hold (trace constraints on cubic Casimirs, etc.) [39].

- Mixed gauge–gravitational and pure gravitational anomalies.

When background curvature is present, the local, covariant coefficients in (Section 4.3 and Section 4.4) generate mixed terms proportional to in ; in even dimensions of the form , one also finds pure gravitational anomalies for chiral matter, in agreement with the index-theoretic classification [5,39].

- Weyl (trace) anomalies.

Taking the BRST differential to be the Weyl differential , the same construction yields , where is the Weyl ghost, the Euler density (type A) and local Weyl invariants (type B), with coefficients determined by the curvature-dependent part of [43]. Again, different renormalization schemes (i.e., different representatives of ) shift by - and d-exact pieces without changing their class.

6.6. Descent and Index: Factoring Through Characteristic Classes

Let denote the space of invariant polynomials (Chern character, Pontryagin classes). In even dimension , the anomaly polynomial determines by descent a cocycle [41,42]. In our setting, the principal, curvature-dependent symbol of the local bidifferential operator defines an element of and the map factors as

up to s- and d-exact terms. This makes precise the statement that encodes the local index density data of the anomaly. The factorization is consistent with the BV formulation of the quantum master equation (QME) in pAQFT, where the anomaly is the obstruction to solving the renormalized QME and satisfies the same WZ condition [44,45,48].

6.7. Scheme Independence and One-Loop Exactness

Because is defined on Hochschild classes, finite renormalizations (i.e., changes Z of scheme) cannot change ; they only modify representatives by s- and d-exact terms (Proposition 6). Consequently, standard nonrenormalization results for consistent anomalies (e.g., Adler–Bardeen-type statements) are compatible with our picture: higher-order scheme changes shift by trivial cocycles but cannot alter their cohomology class [39]. This is mirrored on the MWI side, where violations can be removed by finite counterterms whenever the corresponding class vanishes; otherwise, an anomalous MWI holds with fixed [45].

6.8. Examples: Recovering Known Anomaly Structures

- ABJ anomaly in .

Take chiral fermions in a representation R of a compact gauge group. The current-sector cocycle of (31) produces, upon applying , the density

in agreement with consistent vs. covariant choices distinguished by Bardeen–Zumino polynomials [40,46,47].

- Weyl anomaly in .

For a conformally coupled scalar or a Dirac field, the curvature-dependent part of (Section 4.4) yields

with coefficients determined by the field content; the split into type A/B follows the geometric classification of [43].

6.9. Summary

The first-order, local associative deformation encoded by determines, through the anomalous MWI, a BRST anomaly class . Hochschild closedness yields WZ consistency, while Hochschild exactness produces a BRST-trivial anomaly. The curvature dependence of recovers the known geometric (index/characteristic-class) structure of gauge, mixed, and Weyl anomalies. Thus, the “algebraic curvature” provides an intrinsic AQFT origin for the anomaly cohomology and its observable consequences.

7. Phenomenological Applications: Calibration and Correlation Laws

In this section, we convert the first-order associative deformation

into quantitative, low-energy predictions. The analysis proceeds in three steps: (i) an effective-operator matching of the tensor structures induced by onto a standard low-energy basis for lepton–photon couplings; (ii) an RG evolution from a matching scale to the experimental scale; (iii) correlation laws among observables obtained by fixing the single small parameter in one channel and propagating to others. Throughout, we retain only the leading (linear) dependence on and impose the Ward–Takahashi identities as derived in Section 5, so that only transverse (gauge-invariant) form factors receive independent deformations.

Here, is a formal bookkeeping parameter that tracks the first-order part of a scheme-induced deformation; its “smallness” reflects that we truncate the expansion at (with consistency controlled by and higher-order obstructions in discussed in Section 8). The condition is not imposed by hand: it follows from associativity of the transported product and is the standard first-order Maurer–Cartan constraint in deformation theory.

7.1. Observables and Form-Factor Normalizations

For a charged Dirac lepton , the -covariant vertex function admits the decomposition

With on-shell renormalization, , and the anomalous magnetic moment and electric dipole moment are

The Ward identity fixes the longitudinal piece, leaving unconstrained and therefore available to receive contributions from (Section 5). We focus on and , which admit a compact effective-operator description.

7.2. From Algebraic Curvature to Effective Operators

The local, covariant cocycle constructed in Section 4 modifies time-ordered products with current insertions by contact terms that, after amputation, project onto the electromagnetic dipole structures. A convenient language is to match onto the SMEFT operator basis above the electroweak scale :

with the lepton doublet, the singlet, H the Higgs doublet, and the electromagnetic field-strength. (We assume hypercharge/weak dipoles have been rotated to the mass basis so that (52) captures the photon coupling after EWSB.) Electroweak symmetry breaking (EWSB) gives the LEFT operator

so that, comparing with (51),

In our framework, the Stückelberg–Petermann deformation induces these dipoles linearly in . It is therefore natural to write

with as a dimensionless “reduced” Wilson coefficient fixed by the local tensor content of in the current sector (cf. (29)–(31)). Combining (54) and (55),

Equation (56) is the basic “algebra → EFT → observable” map at the matching scale.

7.3. RG Evolution from to the Experimental Scales

The LEFT dipole coefficients run under QED/QCD renormalization. To leading-log accuracy,

where denote other LEFT/SMEFT Wilson coefficients that mix into the dipoles at one loop (four-fermion, Higgs–lepton, etc.). The solution is

with . In many scenarios, the mixing terms are subleading and one may take

All results below remain valid to this order by replacing in (56) with their running values at for and at the experimental scale for . (For a systematic SMEFT-to-LEFT evolution including operator mixing, see [49,50,51,52].)

7.4. Calibration of and Propagation

- Concreteness and testability.

The purpose of this section is not to propose a specific ultraviolet completion but to extract falsifiable correlations that follow from the cohomological organization of first-order deformations once a single calibration is chosen. In particular, Equations (61) and (63) give parameter-free relations (up to flavor texture assumptions) that can be confronted with improved measurements of , and EDM bounds.

Fix a reference channel, e.g., the muon anomalous magnetic moment. We use the experimentally measured muon anomalous magnetic moment as the calibration input, as reported by the BNL E821 experiment and the Fermilab Muon g–2 collaboration [53,54]. For the Standard Model prediction and the definition of the discrepancy, we refer to the current community theory evaluations [55]. Define the (experiment–SM) discrepancy (we keep it symbolic). At the scale ,

Inserting (60) into (56) yields parameter-free correlations:

In particular, (56) implies the EDM– phase relation

independent of and . Thus, any nonzero phase in the -induced dipole immediately correlates with .

7.5. Flavor Textures and Universal Correlation Laws

Equation (61) still depends on the flavor texture of . Two benchmark hypotheses capture broad classes of UV completions and are natural from the algebraic standpoint (they reflect whether the chirality flip is provided dominantly by the Higgs insertion or not):

- Texture U (flavor-universal). independent of ℓ. Then and :

- Texture Y (Yukawa-aligned/MFV). with . Then and :

These follow directly from (56) using and are stable under leading-log running because the QED anomalous dimensions are flavor universal.

7.6. Rigorous Statements and Proofs

We formalize the above as two propositions.

Proposition 10

(Phase–ratio relation). Let the deformed vertex satisfy the WTI of Section 5, and assume that the transverse dipole structures arise solely from the local cocycle ω via (55) with a single complex coefficient for flavor ℓ. Then, (63) holds, i.e.,

independent of Λ, ε, and RG improvement at the leading log.

Proof.

Proposition 11

(Flavor-scaling laws). Under Texture U (resp. Y), the ratios in Table 1 hold to the leading log.

Table 1.

Parameter-free correlations implied by the algebraic-curvature deformation, for two benchmark flavor textures of .

Proof.

In Texture U, is a common constant, so from (56) , , and the listed ratios follow. In Texture Y, , giving and . Universality of the anomalous dimensions ensures that running does not spoil ratios at the leading log. □

7.7. Uncertainty Propagation and Inference of

Let be calibrated with uncertainty . Denote by the predicted ratio in a chosen texture, and by the (possibly complex) ratio of reduced Wilson coefficients . Then

where and includes theoretical systematics from RG evolution and matching. Analogously, EDM predictions read

Given measurements (or upper bounds) on and , one can infer and up to texture assumptions by combining (60) and (63).

7.8. Beyond Dipoles: Additional Transverse Structures

While the dipole operator dominates low-energy, spin-flip observables, other transverse pieces can arise from :

- Anapole form factor (axialvector coupling), which contributes to parity-violating Møller and atomic observables. The cocycle components acting on axial currents generate local operators of the form in LEFT; these are suppressed by but can be relevant at Z-pole energies.

- Four-fermion operators mixing into under RG, e.g., ; their leading effect is encoded in the second line of (57) and is modeled by the same through the -tensor structure in the matter sector.

These additions preserve the correlation logic but introduce further (controlled) parameters if included in the same order.

7.9. Consistency Checks: Dimensions, Limits, and Decoupling

The map (56) is dimensionally consistent: , , and while . In the decoupling limit or , both and vanish linearly in (quadratically if Texture Y is enforced through Yukawa scaling). If the phase vanishes, , then as in (63). These properties are invariant under reparametrizations of the renormalization scheme because multiplies a class and observables depend only on through .

7.10. Illustrative Worked Example (Symbolic)

7.11. Remarks on Hadronic and SM Backgrounds

The map (56) concerns new contributions induced by . Standard Model (SM) backgrounds (QED, electroweak, hadronic) are additive and can be subtracted in defining the discrepancies . The hadronic vacuum polarization/light-by-light pieces are independent of and enter only through the input value of used for calibration; see [55,56] for comprehensive SM accounts. Our correlation laws are thus insensitive to the internal organization of the SM piece, provided a common convention is used across flavors.

7.12. Application to the Muon : Calibration and Predictions

The electron anomalous magnetic moment has been measured with extremely high precision; we refer to the most precise determinations in the literature [57,58].

We now specialize the general map of Equation (52) to the muon channel and propagate to other leptons. Define the (experiment–SM) discrepancy symbolically by (we do not use any external numeric input here). The calibration step is, at the scale ,

cf. Equation (56). Inserting this into Equation (52) gives parameter-free correlations:

For the EDMs, we use the phase–ratio relation (59):

Two benchmark flavor textures, both natural in the present framework, then, imply the following:

- Texture U (flavor-universal): .

- Texture Y (Yukawa-aligned/MFV): with .

These relations are derived entirely within the paper from Equations (52)–(59); no external numbers are needed. Importantly, the signs of and may differ here (depending on the relative phase of and ), which will become a key discriminator below.

7.13. Vector-Portal (“Dark-Photon”) Foil: Loop Structure, Scaling, and Discriminants

As a foil, consider a kinetically mixed vector of mass that couples as after the diagonalization of kinetic terms (we reserve for our algebraic-curvature deformation and write for the kinetic-mixing parameter). The one-loop contribution to the lepton anomaly is (vector coupling)

This integral is positive and yields the familiar limits

At the leading order with a pure vector coupling, does not induce an EDM (), since there is no CP-odd phase (CP–odd EDMs may arise only if additional CP-violating interactions are introduced beyond minimal kinetic mixing).

- Qualitative comparison to algebraic curvature.

- Sign structure. Curvature can accommodate either sign for (through ), and different flavors can in principle have opposite signs. The minimal vector gives a positive contribution to all ℓ.

- EDM correlation. Curvature predicts (Equation (59)), so a nonzero phase forces a correlated EDM. The minimal dark photon has at one loop. Hence, any robust nonzero aligned with favors curvature over a pure dark photon.

- Flavor correlations. Curvature gives the mass ratio laws in Section 7.12 (Texture U or Y). For a dark photon, the flavor pattern is governed by : with f the loop integral in (70).