Abstract

The anion, cation, and radical structural forms of B2N (−,0,+) were studied in the case of symmetry breaking (SB) inside a (5, 5) BN nanotube ring and were also compared in terms of non-covalent interaction between these two parts. The non-bonded system of B2N (−,0,+) and the (5, 5) BN nanotube not only causes SB for BNB but also creates an energy barrier in the range of 10−3 Hartree of due to this non-bonded interaction. Moreover, several SBs appear via asymmetry stretching and symmetry bending normal mode interactions according to the multiple second-order Jahn–Teller effect. We also demonstrated that the twin minimum of BNB’s potential curve arises from the lack of a proper wave function with permutation symmetry, as well as abnormal charge distribution. Through this investigation, considerable enhancements in the energy barriers due to the SB effect were also observed during the electrostatic interaction of BNB (both radical and cation) with the BN nanotube ring. Additionally, these values were not observed for the isolated B2N (−,0,+) forms. This non-bonded complex operates as a quantum rotatory model and as a catalyst for producing a range of spectra in the IR region due to the alternative attraction and repulsion forces.

1. Introduction

B2N (−,0,+) structures are susceptible to the symmetry breaking (SB) effect triggered by the pseudo-second-order Jahn–Teller effect. These structures can result in non-bonded attraction or repulsion within (5, 5) BN nanotubes (BNNTs), potentially causing either real or artefactual interactions [1,2,3,4]. Over the past few decades, several experimental and theoretical discussions have been conducted regarding BNB structures [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. However, there has been little significant work on the SB of B2N (−,0,+) structures in non-covalent systems within homogenous rings, such as (5, 5) BN nanotubes (BNNTs), aside from our previous work [13,14,15,16] and work by our colleagues at the University of Texas, Austin [17,18]. In 1989 Martin et al. conducted an extensive study on BnN3−n (n = 0, 1, 2 and 3) simultaneously. They observed an asymmetric linear structure for neutral B2N(0) in its ground state, with low bending vibration ranging from 71 to 73 cm−1 [1]. Generally, researchers agree on a linear combination in ground states for B2N (−) and B2N (0) with terms of ( and (, respectively. Consequently, Paldus [9] minimized the BB radical through an extensive calculation of multi-reference coupled clusters in both singlet and doublet positions [RMR CCSD (T)] by using basis sets (cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, and cc-pVQZ). Asmis et al. demonstrated and analyzed a mode value of of 6329 ± 39 cm−1 after [2]. They interpreted these states through a photoelectron spectrum as two equations, and , with linear symmetry transitions at 355 and 266 nm, respectively. Moreover, through the IR spectrum for the electronic band was observed at 6000 cm−1 [7]. According to Walsh’s theorem [19], a linear -block of B includes 11 electrons in valence orbitals. By adding an extra electron, the configuration can shift towards the ground state as follows: . Moreover, the (5, 5) BN nanotube structure enables us to create multiple reactive sites for the B2N (−,0,+) @ (5, 5) BN system, including functional groups similar to core/shell systems. In this work, a B2N (−,0,+) @ (5, 5) BNNT system was simulated from the viewpoint of quantum non-bonded interactions, considering the attraction or repulsion forces between BN (−,0,+) B ions. In this activity, we confirmed the creation of several energy barriers for the BN (−,0,+) B system during its interaction and quantum rotation inside (5, 5) BNNTs. We also discussed how the external field of (5, 5) BNNT rings would lead to a stronger pseudo-second-order Jahn–Teller effect [20,21,22] for certain BN (−,0,+) B ions in various states.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Quantum Theory of the BN (+, −, 0) B @ (5, 5) BNNT

In quantum mechanics, it has been confirmed that the total wave function of our system, which includes and in the overall structure of the non-bonded combination of @, is anti-symmetric under the permutation of electron coordinates. Moreover, it can also be proven that the product states under intermolecular exchange cannot be anti-symmetric. Therefore, an anti-symmetrization operator could be defined for this behavior as “” [23]. This approach is interpreted according to the Eisenschitz statement [24], which indicates that the anti-symmetrized unperturbed states are no longer eigen-functions of H (0) with the commutator. In addition to the projected excited states, can be represented as a linear relationship [23,24,25]. The first-order equation for energy, which includes exchange terms, can be rearranged as follows:

Although the exchange term is commensurate, it arises from the overlapping between BN (+, −, 0) B and the (5, 5) BNNT rings, making it difficult to calculate the related energies. Thus, its wave functions decay exponentially due to the exchange interaction, which depends on changes in distance variables [23,24,25]. Consequently, a ring, especially with a small diameter, could be effectively utilized in this non-bonded model to enhance overlap. (In our model, exchange interactions should be neglected.) We also observed that although this interaction is generally attractive, in certain positions, it shifts towards repulsive forces due to the diameter of the rings and the presence of ionic or radical states. Therefore, RS-PT theory [23,24,25,26,27,28,29] was utilized, taking into account the exchange factor. The unperturbed Hamiltonian was estimated by summing two monomer Hamiltonians. Meanwhile, we assume that the total Hamiltonian is the sum of these two sections, as shown in the following equation:

In this case, the unperturbed states can be written as follows:

Charge densities of BNB parts can be measured using the equation

In this equation, represents the nucleus of boron and nitrogen atoms with position vector R. The Dirac delta, Zα δ(r − R), can be used to express the changes in these nuclei over the n − 1 electron coordinates of B2N (−,0,+) as follows:

It can be shown that the first-order expression can be rearranged as

Equations (2)–(8) confirm the RS-PT energy related to the electrostatic interaction of BN (+, −, 0) B @ (5,5) BNNT. This interaction was simulated in this work by using the following equation:

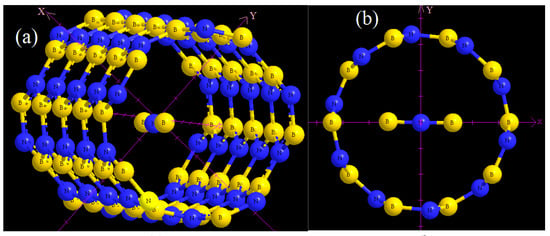

All relative motions, including vibration and rotation, in the BN (−,0,+) B @ (5, 5) BNNT system affect the charge densities in both the ground and excited states. We measured the ion–dipole and dipole–dipole parameters, as well as non-overlapping parts for the BB @ system across various electronic states. For the ionic forms, the ion–dipole interactions of inside can also be estimated. These interactions are created as either intermolecular forces or a rather special kind of force, such as multipolar attraction, which is related to the distance (). This piece of information confirms that attraction can be produced in the ground state between and the ring. In contrast, repulsion appears between and rings (Figure 1). In the excited state, particles generate an attractive force towards each other. Based on the free rotation of , the total electrostatic dipole–dipole interaction is evidently much weaker and lower than the non-averaged one [30]. The total electrostatic interaction energies and charge distributions can be estimated as follows:

Figure 1.

Optimized configuration of BNB inside : (a) vertical position and (b) horizontal position.

The charge distribution of these molecule and ions inside the ring is highly polarized. The Hamiltonian should be considered based on the Born–Oppenheimer approximation for all pairs of non-bonded interactions.

where the unperturbed states can be written as with

and

Here, we measured the electrostatic energies of the monomer’s wave functions using a multipole expansion [31,32,33,34].

2.2. The Interactions Between BNB and

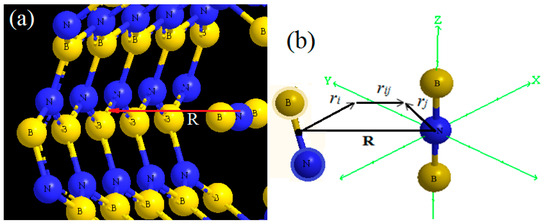

Figure 2 shows the structure of a BNB molecule and a ring at a distance R (from the BNB molecule to each B-N bond of the ring). It is worth noting that the wave function may be too small due to overlap and can be omitted. Particles with indices ∈ and are considered in this model, with a total Hamiltonian shown as . This Hamiltonian combines two parts: (A) a free molecule, , and (B) an interaction operator,

Figure 2.

(a) BNB located at distance R from the B-N unit of a BNNT ring; (b) and , and , with R= (0, 0, R) and rij = rj − ri + R. The red arrow demonstrate the distance between atom N from B2N to atom B from center of BNNT.

One of the B-N bonds in the ring interacts with BNB molecules to create an external potential denoted by for BN (−, 0, +) B. This potential is defined as . Therefore, we can express it as

By making a substitution into Equation (1) and rearranging Equations (9)–(14), Equations (15)–(17) result in the following:

Here the total charges can be measured as

The operator H (1) represents the electrostatic interactions of the dipole moments and charges for the BB @ system. The operator for the dipole–dipole interaction tensor can be presented as follows:

The interaction tensor can be arranged as ==. This can also be expressed in more general terms.

The application of the Schrödinger equations between the isolated BNB and can be written as = and =. The eigenvalues of unperturbed terms (=, with ) are .

Therefore, the first-order energy can be measured using the following equation:

Moreover, the multipole expansion of this integral can be separated by the Cartesian coordinates () and () of molecules BNB and .

The permanent multipole moments are and . Similar to the above equation, the second-order energy can be written as follows:

Here k denotes the excited state, which is divided into two parts as k = (k1, K2). In addition, summation over k 0 results into a split into three sums in the excited state. These are k1 ≠ 0 and K2 = 0 for BNB, k2 ≠ 0 and k1 = 0 for the , and (k1, k2) ≠ 0 for the non-bonded combination of the system of BNB inside the . Here, we assume that the has a ground state configuration, while BN (−,0,+) B can be excited to different energy levels. The main important issue is to understand the electrostatic interaction between BNB and the environment. The electrostatic interactions of the BNB exhibit multiple turning points with several parts of the loops. Consequently, the first bond of the B-N position in the first segment of the has been estimated, while the other loops have been kept frozen. Meanwhile, this action will continue systematically to consider all positions (Figure 2). We also selected each B-N bond in front of each part in the subunit and then measured the non-bonded interaction between these two parts [14]. According to our previous works [13,14,15], dipole expansions are utilized in electromagnetic field approaches due to the charge distributions [31,32,33,34]. Due to the lack of experimental evidence, the theoretical simulations can be improved by the concepts of dipole moment and angular momentum. These can be defined as a sum of spherical harmonics as follows:

According to the total electrostatic interaction energy (UBNNT-BNB) from Equation (9), the charge distribution of the ring can be polarized through BNB due to the electromagnetic field induced by the ring environment. The dipole moment arising from the electric charge distribution usually produces powers according to the distance (r) as well as angular dependence (Ө and Φ). The dipole moment can be analyzed based on two cases: one where the charge distribution is located near the origin, resulting in exterior dipole moments, and another where the charges are far from the origin, resulting in interior dipole moments. Therefore, it can usually be calculated by considering both interior and exterior dipole contributions [14,31,32,33,34].

For BNB, it can be considered that Ө = Φ = 0, meaning that the dipole moment vectors should be located on the BNB axis. Due to the measurement of dipole moments, the r component can be predicted for both cationic and radical forms of BNB. These molecules exhibit a tendency to rotate within three distinct conical surfaces. Therefore, it can be concluded that the dipole moment arises from the linear structure of the BNB molecule. Under extrinsic factors, the physico-chemical properties of the radical, anion, and cation of the BNB-BNNT non-bonded combination forms will be completely altered by the electrical current passing through the ring. Consequently, the three types of ions, i.e., cationic, anionic, and radical, enable the generation of ions from each other frequently. As a result the radial vector of the dipole moment (r) becomes quantized during the formation of three cone levels.

Finally, the BSSE was used to calculate the binding energies of pseudo-systems, including the ghost atom, in its normal position within any real molecule when applying a normal basis function that was fitted. Since they do not have a nuclear charge or any electrons to contribute to the molecule, we need to use an appropriate ghost basis set file for each atom involved in the calculation. After that we can copy the basis set file and remove the frozen core. In quantum chemistry, measurements using different basis sets are susceptible to basis set superposition error (BSSE). When atoms interact, their basic functions overlap, causing each part to "borrow" functions from nearby parts. In order to improve the calculation of derived properties such as energy, we need to consider using BSSE.

3. Results and Computational Details

The system was minimized using the CASSCF (10, 12) level, which included EPR-II, EPR-III, and AUG-cc-pvqz basis sets for ionic forms. Meanwhile, for the radical form, the UHF and ROHF methods were also taken into consideration. Energy minimization of B2 in ground and excited states within the BNNT ring was measured using the M062x/6-31g*, M062x/EPR-II, B3p86/EPR-ii, B3p86/6-31g*, and B3LYP/6-31g* levels of theory. The BNNT ring was also optimized using the DFT method (Table 1 and Table 2 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). All ab initio calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 software, as well as additional correlated software: Games (modified by Head Gordon), Chem3D, and AIM within this version of Gaussian programming software [35].

Table 1.

Electric Potential (EP) and Isotropic Fermi Contact Couplings (IFCCs) (MHz) for isolated and non-isolated B2.

Table 2.

Energies of B2 @ BNNT.

ECPs were measured using QCISD/EPR-III, m062x/6-31g, b3p86/6-31g, HF/EPR-ii, HF/6-31g*, and m062x/EPR-ii for BNB (−, 0, +) in different scenarios within a (5, 5) BNNT environment. Attraction and repulsion energies between the BNNT ring and BNB (−, 0, +) components in excited and ground states were calculated and are listed in Table 2 and Table 3 (as well as in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3) at different levels of theory.

Table 3.

ECP fitting for BNB@ (5, 5) BNNT (Supplementary Table S3).

The EPR-III and EPR-II basis sets by Barone [36], have been shown to be suitable for ESP distributions. EPR-II is a double-ζ set with a single set of polarization functions, making it suitable for atoms from boron to fluorine [34,36]. In addition, EPR-III is a triple-ζ basis set consisting of diffuse functions with double d-polarization. In EPR-III, the s-part is also modified for accurate optimization in the nuclear region for boron to fluorine atoms [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] (Table 1 and Table 2 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The active space for CASSCF methods is determined based on the number of valence electrons and orbital configurations. A total of 11 active electrons were considered for insertion into 12 active orbitals specifically for B2N(0), with an additional 10 and 12 being added for B2N(+) and B2N(−), respectively. Spin–orbital coupling during various spin states has also been estimated during CASSCF calculations [45]. The Quadratic CI calculations with single and double substitutions [43] have also been used for measurement. One-electron items include bonding analysis and atoms in molecules of Bader’s theory (AIM) [44]. In addition, we explored the coupling of vibrations. Additionally, we included the time-dependent DFT and extended multi-configuration with second-order perturbation theory. We found that the coupling of spin–orbitals, along with electron– and hole–vibration couplings, is sufficient to describe the mechanistic link between observed structural distortions and the SOJT framework.

Natural bond orbital and population analyses based on multipole momentum and electrostatic potentials were conducted using the Merz–Kollman–Singh [45], Chelp [46], or Chelp-G [47] approaches. Hyper-polarizabilities and polarizabilities were measured in a simplified manner using the CISD and QCISD methods. Double numerical differentiation for energies was defined using the “pol=En only” keyword in BNB systems. Since the charges from molecular electrostatic potentials (MESPs) may not be well-suited for larger molecules, as the innermost atoms are placed far away from the MESP centers, CHELPG (Charges of Electrostatic Potentials including Grid reticulation) was applied to fit and reproduce the MESPs at various points around the molecule (see Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3). A comprehensive discussion of the detailed result basis set and the Hamiltonian effects on charge distribution was provided by Martin et al. [48]. In this work all calculations were performed using the Gaussian program package [35]. Minimization was achieved through frequency measurements to confirm proper geometries in a true minimum (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The discussion can be separated into three sub-sections, containing (a) structural concepts, (b) energetic concepts, and (c) physical and chemical properties. The related results are shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, as well as several (Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S3). The results of the energies from attraction and repulsion among various BNB (-, 0, +) and (5, 5) BNNT rings are listed in Table 4. The data of the physical parameters for both isolated and non-isolated structures of B2 are listed in Table 5.

Table 4.

Attraction & Repulsion energies (eV) of BNB (−, 0, +) @ (5,5)BNNT.

Table 5.

Several physical properties, such as anisotropic spin dipole coupling (ASDF), Electric Potential, and Isotropic Fermi Contact Coupling {,}, of isolated and non-isolated forms of B2.

4.1. Discussion on Structure

The BNB radical has a linear structure in its ground state ( with a molecular orbital sequence of .

Meanwhile, the lowest excited state is guessed to be , with a molecular orbital sequence of .

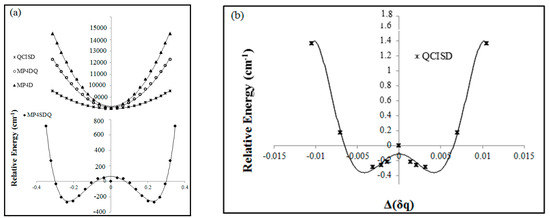

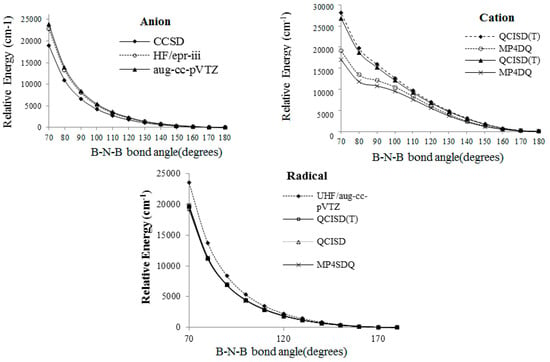

In addition, , which is an excited state with a molecular orbital sequence of (above ), obeys the Jahn–Teller effect. The further excited state is related to the of the triplet state. As can be seen in Figure 3, according to Knight’s works [4], a cyclic radical or anion B2 could not appear. In the cation structure, a bulge can be observed at 90° in the calculation of the MP4DQ and MP4DSQ levels of theory; therefore, this bulge confirms a cyclic B2.

Figure 3.

The B2 case from the viewpoint of SM (symmetry breaking) in several calculations versus the B-N-B bond for (a,b) cation, (c) radical, and (d) anion structures.

By considering the wave function, it was found which BNB with symmetry containing a real wave function must be converted into the irreducible representation (of the point group). In addition, and have degeneracy when two B–N bonds are asymmetrically stretched (similarly, the and MOs have the same symmetry and degeneracy). Therefore, which corresponds to an excited state, has a strong interaction containing singlet and triplet states. In this case the non-isolated configuration energy increases significantly (Table 4). This phenomenon may be due to an artefactual symmetry breaking, which can pose a challenge in the concept of a real Jahn–Teller distortion or artificial model. Distortions for non-isolated BNB compared with isolated ones have two specifications: high distortion energy and irregular symmetry breaking (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

B2 from the viewpoint of symmetry breaking versus B-N-B bond angle according to several methods.

Finally, we are going to understand the differences in the electromagnetic properties of BNB as an isolated structure compared with its localization in the BNNT ring. In the symmetry of the isolated form, the unpaired electron is delocalized, while in the asymmetric structure, it is localized on one of the B atoms. Investigation of the structures has shown that a system with broken symmetry, , can stabilize the non-bonded interaction compared with the symmetric geometry.

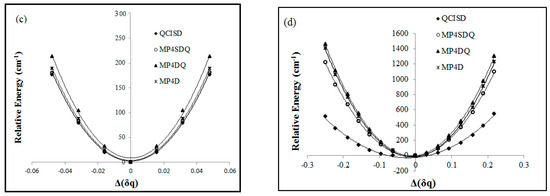

4.2. Discussion on Energy

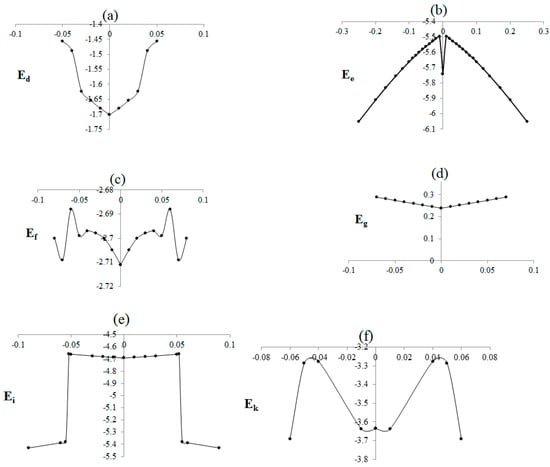

Various DFT methods, including B3p86, B3lyp, m062x, m06-L, and m06, are discussed in relation to non-bonded interactions between BNB (−, 0, +) and BNNTs in various scenarios. The novel methods m062x, m06-L, and m06-HF show promising results in non-bonded measurements, making them useful for calculating energies based on distances with medium (∼2–5 Å) and long (5 Å) ranges [49]. However, the B3LYP method is unable to predict van der Waals information for medium-range interactions [49,50]. Studies in recent decades have confirmed inaccuracies in medium-range exchange energies leading to large systematic errors in the prediction of molecular properties [51,52,53,54,55]. Although DFT methods are unable to perfectly exhibit second-order Jahn–Teller distortion for isolated BNB, these levels of theory for BN(−, 0, +)B-BNNT systems can estimate the second-order Jahn–Teller effect for BNB approximately, which is useful for further comparison (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 5) [56,57,58,59].

Figure 5.

Relative energies of B2 versus B-N-B bond of a BNB@95,5) BNNT system, where (a,b) (radical), (c,d) (anion), (e) , and (f) .

In Table 4, the calculation data for m062x with Epr-ii and 6-31g* can be seen and compared with B3P86 and B3LYP, showing lower values. Interestingly, both the m062x and B3LYP methods show attraction for BN (−, 0) B and repulsion for BN (+) B with the BNNT ring. Table 1 lists the energy differences for the global minima and local minima for both and . It also confirms that the total energies for both methods are the same as the spin–orbitals depending on the bending angles of A1 and A2, which have an extremely low frequency of around 70 cm−1 from bending vibration. As it is indicated in Table 1 and Table 2, the energy of in the state of for isolated BNB (0) is higher than that of for non-isolated BNB (0), and so is the one for . The energies of , can be shown as

and

Consequently, the differences between these cases indicate that is significantly higher in stability than , so the isolated form has more stability compared with the non-isolated form. Moreover, the orbital has higher stabling compared with the non-isolated form for both the cation and anion structures. The energies of and valance-occupied MOs for the first triplet excited state are , = −0.23701 and while those for are , and .

Since the energy of is higher than that of , it can be concluded that there is a stronger correlation in the anion form compared with the other forms. In the excited state, an electron moves from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), , to the MO, which is devoted the state, appearing considerably above the previous state.

According to the values in the tables and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, the energy differences between the two states () and ( {(k – a) and (k – k′)} are 5829.75 cm−1 and 5834.79 cm−1, respectively. These amounts are closer to the photoelectron spectroscopy calculations which were performed by Asmis et al. [2]. Consequently (excited state above ) is subject to the Renner–Teller effect according to the data in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, which is confirmed for the BNB radical in the BNNT field in neutral B2N {() and , though in a high energy level.

4.3. Calculation of Physical Properties

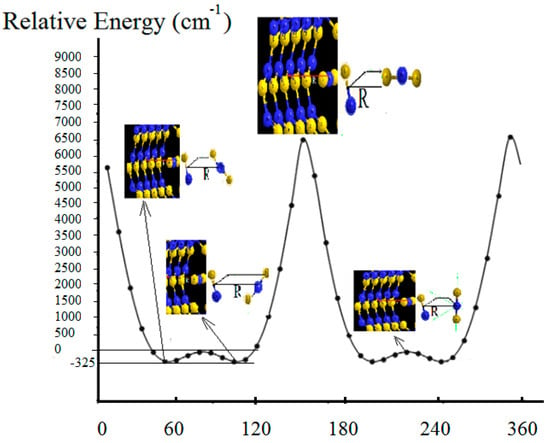

Electrical parameters and electrostatic potential (EP), including the geometry of BNB in the excited and ground states, as well as HOMO/LUMO and Isotropic Fermi Contact Couplings (MHz), under the external field of a (5, 5) BNNT were calculated. The data are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The ESP fitting, i.e., , and the force energies of both attraction and repulsion for the BNB (−, 0, +) @ (5, 5) BNNT ring system, including NBO information, are reported (in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). Anisotropic spin dipole coupling (MHZ) and the differences () are also listed in Table 5. The data in Table 5 correspond to the IFCC amounts, including the EP of the BNB (−, 0, +) @ (5, 5) BNNT ring system. It is notable that the EP is not influenced by the external field caused by the ring, while the IFCC is. In addition, the dipole moment of the ( radical can change from 0.000 (for isolated BNB) to 1.4436 (for non-isolated BNB); therefore, IFCC also varies between these two limits. In addition, multiple initial orientations of B2N inside the BNNT ring were explored, such as axial/equatorial, vertical, and placements at other degrees (Figure 6). A systematic potential energy surface scan was performed over rotational and translational coordinates to perform quantized rotation. Moreover, vibrionic couplings are important for understanding non-adiabatic processes, especially near points of conical intersections. In this study vibrionic coupling and non-adiabatic coupling or derivative coupling were considered for the interaction between electronic and nuclear vibrational motions of our system. Since direct calculation of vibrionic coupling is challenging due to difficulties associated with its evaluation, in our model, vibrational and electronic interactions were calculated according to the Born–Oppenheimer approximation.

Figure 6.

Potential energy surface (PES) scan using CASSCF (10, 12)/AUG-cc-pvqz.

The MESP fitting for charges as well as partial charges for two boron atoms and one nitrogen atom () in the range from to exhibited a value of zero for the radical system, approximately (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, the summation of partial charges in for the BNB radical inside the BNNT ring is not zero, with amounts in the ranges of 0.1–0.2 for 0.1 to −0.32 for , and 0.13 to 0.22 for (Supplementary Table S3). This is due to the fact that the unpaired electron of nitrogen is localized while BNB is under the influence of the external field of the BNNT ring, causing a charge transfer between BNB and the BNNT. Obviously, the differences among, and are attributed to the various methods and basis sets used. For the excited state of radical forms, although the change in MESPs for both the excited state() and ground state ( is negligible, as opposed to the ground state (S = 1 of the BNB radical), the IFCC is not considerable for S = 3/2 (Table 1 and Table 5). The sum of partial charges () for all items is −1, indicating an anion form. However, the total partial charge of for the BNB anion inside the BNNT ring is not −1, and it changes from mostly around −0.9, −0.8, and in one case, −0.6 for and for . As a result, the total partial charge for all the items of BN (−) B is less than −1 (Supplementary Table S3). This is because the unpaired electron of nitrogen is localized while BNB is under the influence of the external field of the BNNT ring. It seems that the anion isolated in the field of the BNNT ring changes to a combination of radical and anion forms. Finally, the stability sequences are calculated as follows: {BNB (−) > BNB (0) > BNB (+) for non-isolated}{BNB (+) > BNB (0) > BNB (−) for isolated}.

5. Conclusions

Several states of the linear BNB molecule both in isolated position and inside a BNNT field were calculated using various ab initio methods based on multi-reference wave functions. CASSCF calculations predict a symmetry-broken (SB) structure for BNB with unequal bond lengths, as does perturbation theory with second-order perturbation theory. Therefore, knowing the spin–orbital couplings and electron– and hole–vibration couplings is important to describing the mechanistic link between observed structural distortions and the SOJT framework. We also examined the case of (excited state above ) according to the Renner–Teller effect, which is confirmed for the BNB radical in a BNNT field, as well as for neutral B2N {() and . We also discussed the differences among the electromagnetic properties of BNB as an isolated structure compared with its localization in a BNNT ring. We found that according to the total electrostatic interaction energy (UBNNT-BNB) from Equation (9), the charge distribution of the ring can be polarized through BNB due to the electromagnetic field induced by the ring environment. We also found that the twin minimum of BNB’s potential curve arises from the lack of a proper wave function of permutation symmetry, as well as abnormal charge distribution. Moreover, we found that in the symmetry of the isolated form, the unpaired electron is delocalized, while in the asymmetric structure, it is localized on either one of the B atoms. Investigation of the structures proved that a system with broken symmetry, , could stabilize the non-bonded interaction compared with the symmetric geometry. Since the quantum behavior under an external field is completely different in an isolated position, important information can be obtained from any external field that affects the quantum systems of the mentioned molecules. We also recommend that researchers use various external fields that can affect small molecules to obtain valuable information.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/quantum7040058/s1, Table S1: Continuation of Table 1. B2 in ground and excited states, Electric Potential (EP), and Isotropic Fermi Contact Couplings (IFCCs) (MHz) for isolated and non-isolated positions of BNB, Table S2: Continuation of Table 2. Energies of B2 in ground and excited states inside the BNNT ring, Table S3: Continuation of Table 3. Charges from ECP fitting for BNB in two positions, isolated and under the external field of a (5, 5) BNNT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; Methodology, M.M. and F.M.; Software, M.M.; Validation, M.M. and F.M.; Formal analysis, M.M. and F.M.; Investigation, M.M. and F.M.; Resources, M.M. and F.M.; Data curation, M.M. and F.M.; Writing—original draft, M.M. and F.M.; Writing—review and editing, M.M. and F.M.; Visualization, M.M. and F.M.; Supervision, M.M.; Project administration, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martin, J.M.L.; François, J.-P.; Gijbels, R. A b initio study of boron, nitrogen, boron–nitrogen clusters. I. Isomers and thermochemistry of B3, B2N, BN2, N3. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 6469–6485. [Google Scholar]

- Asmis, K.R.; Taylor, T.R.; Neumark, D.M. Anion photoelectron spectroscopy of B2N−. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.L.; François, J.-P.; Gijbels, R. Some cost-effective approximations to CCSD and QCISD. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1990, 172, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, L.B., Jr.; Hill, D.W.; Kirk, T.J.; Arrington, C.A. Matrix isolation ESR and theoretical investigations of 11B14N11B and 10B14N11B: Laser vaporization generation. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.L.; François, J.-P.; Gijbels, R. The structure, stability, and infrared spectrum of B2N, B2N+, B2N−, BO, B2O and B2N2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 193, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, P.; Andrews, L. Pulsed laser-assisted reactions of boron and nitrogen atoms in a condensing nitrogen stream. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 9177–9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.; Hassanzadeh, P.; Burkholder, T.R.; Martin, J.M.L. Reactions of pulsed laser produced boron and nitrogen atoms in a condensing argon stream. J.Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Andrews, L. Reactions of B atoms with NH3 to produce HBNH, BNBH, and B2N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10125–10126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Paldus, J. Real or artifactual symmetry breaking in the BNB radical: A multireference coupled cluster viewpoint. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 224304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.; El-Yazal, J.; François, J.P.; Gijbels, R. The structure and energetics of B3N2, B2N3, and BN4 Symmetry breaking effects in B3N2. Mol. Phys. 1995, 85, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, G.; Baba, M.S.; Gingerich, A. Knudsen cell mass spectrometric investigation of the B2N molecule. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 8995–8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, W.R.K.; Weltner, W. B atoms, B2 and H2BO molecules: ESR and optical spectra at 4° K. J. Chern. Phys. 1976, 65, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monajjemi, M. Non bonded interaction between BnNn (stator) and BN(−,0,+) B (rotor) systems: A quantum rotation in IR region. Chem. Phys. 2013, 425, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monajjemi, M.; Lee, V.S.; Khaleghian, M.; Honarparvar, B.; Mollaamin, F. Theoretical Description of Electromagnetic Nonbonded Interactions of Radical, Cationic, and Anionic NH2BHNBHNH2 Inside of the B18N18 Nanoring. J. Phys.Chem. C 2010, 114, 15315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monajjemi, M.; Boggs, J.E. A New Generation of BnNnRings as a Supplement to Boron Nitride Tubes and Cages. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monajjemi, M. Quantum investigation of non-bonded interaction between the B15N15 ring and BH2NBH2 (radical, cation, anion) systems: A nano molecularmotor. Struct. Chem. 2012, 23, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zou, W.; Bersuker, I.B.; Boggs, J.E. Symmetry breaking in the ground state of BNB: A high level multireference study. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 184305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bersuker, I.B. The Jahn–Teller Effect: Implications in Electronic Structure Calculations, January 2009. In Advances in the Theory of Atomic and Molecular Systems; Springer: Dorderecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.D. The electronic orbitals, shapes, and spectra of polyatomic molecules. Part II. Non-hydride AB2 and BAC molecules. J. Chem. Soc. 1953, 2266–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuker, I.B. Jahn–Teller and Pseudo-Jahn–Teller Effects: From Particular Features to General Tools in Exploring Molecular and Solid State Properties. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1463–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuker, I.B.; Polinger, V. Perovskite Crystals: Unique Pseudo-Jahn–Teller Origin of Ferroelectricity, Multiferroicity, Permittivity, Flexoelectricity, Polar Nanoregions. Condens. Mater. 2020, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorinchoy, N.; Balan, I.; Polinger, V.; Bersuker, I. Pseudo Jahn-Teller origin of the proton-transfer energy barrier in the hydrogen-bonded [FHF]-system. Chem. J. Mold. 2021, 16, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, F. On the theory and system of molecular forces. Z. Physic 1930, 63, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenschitz, R.; London, F. Über das Verhältnis der van der Waalsschen Kräfte zu den homöopolaren Bindungskräften. Z. Physik 1930, 60, 491–527, Erratum in Z. Physik. Chemie 1937, 33, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalewicz, K.; Jeziorski, B. Molecular Interactions; Scheiner, S., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1995; ISBN 0-471-95921-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfelder, O.; Curtiss, C.F.; Bird, R.B. Molecular Theory of Gases and Liquids; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A.J. The Theory of Intermolecular Forces; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö, P.; Wang, C.; Straka, M.; Vaara, J. A London-type formula for the dispersion interactions of endohedral A@B systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pyykkö, P.; Straka, M. Formulations of the closed-shell interactions in endohedral systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 6187–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennard-Jones, J.E. Cohesion. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1931, 43, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, A.R. Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.J. Angular Momentum; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, K.S. Multipole expansions of gravitational radiation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1980, 52, 299–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, D.M.; Satchler, G.R. Angular Momentum, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Head-Gordon, M.; Gill, P.M.; Wang, M.W.; Foresman, J.B.; Johnson, B.C.; Schlegel, H.B.; Robb, M.A.; Replogle, E.S.; et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, V. Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods, Parts I; Chong, D.P., Ed.; Springer World Scientific Publisher, Co.: Singapore, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, N.G.; Luyken, R.J.; Cherrey, K.; Crespi, V.H.; Cohen, M.L.; Louie, S.G.; Zettl, A. Boron nitride nanotubes. Science 1995, 269, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasé, X.; Rubio, A.; Louie, S.G.; Cohen, M.L. Stability and band gap constancy of boron nitride nanotubes. Europhys. Lett. 1994, 28, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasé, X.; Charlier, J.C.; de Vita, A.; Car, R. Theory of composite BxCyNz nanotube heterojunctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monajjemi, M. Theoretical Study of Boron Nitride Nanotubes with Armchair Forms. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2013, 21, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.E.; Richards, W.G. Molecular spin-orbit coupling constants. The role of core polarization. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 52, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Koseki, S.; Schmidt, M.W.; Gordon, M.S. MCSCF/6-31G(d,p) calculations of one-electron spin-orbit coupling constants in diatomic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 10768–10772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pople, J.A.; Head-Gordon, M.; Raghavachari, K. Quadratic configuration interaction. A general technique for determining electron correlation energies. J.Chem. Phys. 1987, 87, 5968–5975. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecule: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Besler, B.H.; Merz, K.M.; Kollman, P.A. Atomic charges derived from semiempirical methods. J. Comp. Chem. 1990, 11, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirlian, L.E.; Francl, M.M. Atomic charges derived from electrostatic potentials: A detailed study. J. Comp. Chem. 1987, 8, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brneman, C.M.; Wiberg, K.B. Determining atom-centered monopoles from molecular electrostatic potentials. The need for high sampling density in formamide conformational analysis. J. Comp.Chem. 1990, 11, 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F.; Zipse, H. Charge distribution in the water molecule—A comparison of methods. J. Comp. Chem. 2005, 26, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Check, C.E.; Gilbert, T.M. Progressive systematic underestimation of reaction energies by the B3LYP model as the number of C–C bonds increases: Why organic chemists should use multiple DFT models for calculations involving polycarbon hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 9828–9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Seemingly simple stereoelectronic effects in alkane isomers and the implications for Kohn–Sham density functional theory. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4460–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodrich, M.D.; Corminboeuf, C.; Schleyer, P.V.R. Systematic errors in computed alkane energies using B3LYP and other popular DFT functionals. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3631–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, P.R.; Fokin, A.A.; Pascal, R.A., Jr.; de Meijere, A. Many density functional theory approaches fail to give reliable large hydrocarbon isomer energy differences. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3635–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. A density functional that accounts for medium-range correlation energies in organic chemistry. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5753–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaltney, S.R.; Head-Gordon, M. Calculating the equilibrium structure of the BNB molecule: Real vs. artifactual symmetry breaking. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 4495–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Morse, M.D.; Apetrei, C.; Chacaga, L.; Aier, J.P. Resonant two-photon ionization spectroscopy of BNB. J. Chem. Physics 2006, 125, 194315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, W.A. Ground state structure of BNB using fixed-node diffusion Monte Carlo. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 543, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Probabilistic Measure of Symmetry Stability. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).