Abstract

One of the major challenges for effective intrusion detection systems (IDSs) is continuously and efficiently incorporating changes on cyber-attack tactics, techniques, and procedures in the Internet of Things (IoT). Semi-automated cross-organizational sharing of IDS data is a potential solution. However, a major barrier to IDS data sharing is privacy. In this article, we describe the design, implementation, and evaluation of FedPrIDS: a privacy-preserving federated learning system for collaborative network intrusion detection in IoT. We performed experimental evaluation of FedPrIDS using three public network-based intrusion datasets: CIC-IDS-2017, UNSW-NB15, and Bot-IoT. Based on the labels in these datasets for attack type, we created five fictitious organizations, Financial, Technology, Healthcare, Government, and University and evaluated IDS accuracy before and after intelligence sharing. In our evaluation, FedPrIDS showed (1) a detection accuracy net gain of 8.5% to 14.4% from a comparative non-federated approach, with ranges depending on the organization type, where the organization type determines its estimated most likely attack types, privacy thresholds, and data quality measures; (2) a federated detection accuracy across attack types of 90.3% on CIC-IDS-2017, 89.7% on UNSW-NB15, and 92.1% on Bot-IoT; (3) maintained privacy of shared NIDS data via federated machine learning; and (4) reduced inter-organizational communication overhead by an average 50% and showed convergence within 20 training rounds.

1. Introduction

Cyber threats have become increasingly sophisticated and frequent and are targeting critical infrastructure and sensitive data across various organizational sectors. Adapting dynamically to a changing threat landscape requires learning from the experiences and observations of other organizations. However, a system that helps ensure data privacy and regulatory requirements is a prerequisite for enabling successful network IDS data sharing [1]. A centralized approach to threat detection [2] creates problems through a single point of failure and limited visibility of threats beyond organizational boundaries. Federated learning [3,4] enables multiple organizations to jointly train sophisticated models without requiring direct data sharing or compromising data sovereignty. This distributed learning methodology presents particularly compelling advantages for organizations that can collectively enhance their threat detection capabilities while maintaining strict privacy controls over sensitive network data and proprietary information.

Recent surveys have highlighted the growing importance of federated learning in cybersecurity applications. For example, Idrissi et al. [5] proposed a federated learning approach for anomaly-based network intrusion detection that leverages the use of simple autoencoders, variational autoencoders, and adversarial autoencoders. Agrawal et al. [6] explored the architectures of federated anomaly-based network intrusion detection systems for collaborative threat detection. Zhao et al. [7] proposed multitask federated learning for network anomaly detection, demonstrating the potential for handling heterogeneous data distributions across organizations. Nguyen et al. [8] developed a federated self-learning anomaly detection system for IoT environments, addressing resource-constrained scenarios. Rahman et al. [9] compared centralized, on-device, and federated learning approaches for IoT intrusion detection. Similarly, Amiri-Zarandi et al. [10] introduced a federated learning approach for intrusion detection in IoT using social IoT concepts.

However, existing approaches often suffer from various limitations, including inadequate handling of adversarial environments, insufficient privacy protection mechanisms, lack of comprehensive evaluation, and computational inefficiencies that may hamper real-time detection. This article attempts to address some of these challenges by presenting the following contributions:

- A privacy-preserving federated learning framework specifically designed for network intrusion detection that maintains data privacy while enabling collaborative learning (FedPrIDS).

- Implementation of adaptive differential privacy mechanisms with formal privacy guarantees (epsilon-delta privacy) tailored to network IDS data.

- Introduction of a novel hybrid feature selection approach that achieves speedup over un-tailored methods.

- Comprehensive evaluation using five synthesized organizational scenarios with varying threat profiles and privacy requirements using network intrusion data from three public datasets (CIC-IDS-2017 [11], UNSW-NB15 [12], and Bot-IoT [13]).

- A novel approach for increased detection effectiveness compared to single-organization NIDS detection.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses related work; the methodology is detailed in Section 3; the implementation is presented in Section 4; Section 5 presents the analysis and results; the limitations of this work are discussed in Section 6; and finally, the conclusion and future work are presented in Section 7.

2. Related Work

Several related works have contributed to the broader understanding of machine-learning-based intrusion detection and privacy-preserving techniques. The theoretical foundations of differential privacy were established by Dwork and Roth [14], providing the mathematical framework that underpins modern privacy-preserving systems. Yang et al. [15] explored the broader applications of federated machine learning beyond cybersecurity contexts. Various deep learning architectures have been proposed for intrusion detection, including approaches using sparse autoencoders with support vector machines [16], deep autoencoders [17], and variational autoencoders for anomaly detection from network flows [18]. Tharewal et al. [19] applied deep reinforcement learning specifically to Industrial IoT environments. However, these systems face challenges from adversarial attacks, as explored by Alhajjar et al. [20]. Bonawitz et al. [21] developed secure aggregation protocols to enable privacy-preserving collaborative learning.

Federated learning approaches for network intrusion detection can be categorized into three main paradigms based on data distribution and collaboration models. Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL) [15] applies when organizations share the same feature space but possess different data samples. Most existing FL-IDS implementations [7,8] adopt HFL, operating under the assumption that all participants collect similar network traffic features. While HFL demonstrates effectiveness in homogeneous environments, it encounters challenges when addressing feature heterogeneity across different organizational infrastructures. Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) [22] addresses scenarios where organizations possess different feature sets for overlapping entities. In IDS contexts, VFL could theoretically enable collaboration between organizations monitoring different network layers or employing distinct collection tools. However, practical VFL implementations remain limited due to computational complexity and entity alignment challenges. Federated Transfer Learning (FTL) [23] extends these approaches by handling cases with both different features and non-overlapping sample spaces. While FTL shows promise for cross-domain threat intelligence sharing, its deployment requires sophisticated domain adaptation techniques that may not yet be mature for real-time IDS applications.

FedPrIDS adopts an HFL framework enhanced with adaptive mechanisms to address partial feature heterogeneity through our hybrid feature selection strategy. To contextualize our contribution within the broader landscape of federated IDS research, Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of FedPrIDS against recent FL-IDS implementations across key technical dimensions including privacy mechanisms, feature selection approaches, evaluation methodology, organizational diversity, and real-time capabilities.

Table 1.

Comparison of FedPrIDS with related federated IDS approaches.

The comparative analysis reveals several key differentiators that distinguish FedPrIDS from existing approaches. First, FedPrIDS implements formal privacy guarantees through differential privacy mechanisms rather than relying on heuristic or encryption-based approaches that lack mathematical rigor in privacy preservation. Second, our adaptive feature selection methodology is optimized simultaneously for detection performance and communication efficiency, addressing a critical gap in existing implementations that typically employ either no feature selection or static approaches. Third, the comprehensive evaluation across three distinct datasets (CIC-IDS-2017, UNSW-NB15, and Bot-IoT) provides stronger evidence of generalizability compared to single-dataset evaluations prevalent in the literature. Fourth, FedPrIDS incorporates organization-specific parameterization that accommodates heterogeneous privacy requirements and data quality characteristics, enabling more realistic multi-organizational collaboration scenarios. Finally, our approach emphasizes performance optimization for real-time detection capabilities, achieving 37–43% preprocessing speedup while maintaining detection accuracy, a practical consideration often overlooked in academic prototypes that prioritize theoretical contributions over deployment feasibility.

3. Methodology

3.1. Datasets

In our evaluation, we used three large public datasets that provide good coverage of different types of cyber threats and applications and network structures. The CIC-IDS-2017 dataset [11] contains 2.8 million network traffic samples captured over multiple days, encompassing both benign activities and various sophisticated attack types, including DoS Hulk, PortScan, DDoS, DoS GoldenEye, and FTP-Patator attacks. The UNSW-NB15 dataset [12] includes 300,208 samples. Attack categories used in UNSW-NB15 include fuzzing, backdoor, DoS, exploit, reconnaissance, shellcode, worm, and generic. The Bot-IoT dataset [13] provides 3.7 million samples focusing on IoT-specific threats including botnet attacks, distributed denial of service attacks, reconnaissance operations, and data theft attempts. To simulate realistic organizational scenarios, we distributed the data across five fictitious organizations based on their assumed threat profiles, with each organization receiving a random mix of attack types. Each organization’s data was split into 80% training and 20% testing sets using stratified sampling.

3.2. System Architecture

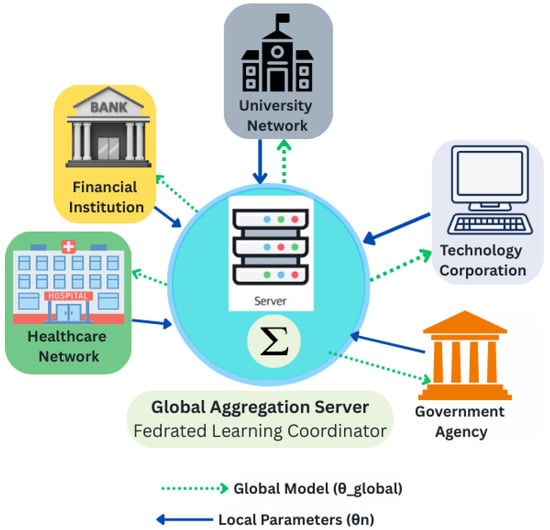

The system architecture encompasses multiple organizational participants and a central coordination server that facilitates secure model aggregation without requiring direct access to raw network data from participating organizations. Each organizational participant maintains complete sovereignty over its local data while contributing to collective threat intelligence through privacy-preserving ML model parameter sharing. The central coordination server operates as a trusted aggregator that receives encrypted model updates from participating organizations, performs secure aggregation using privacy-preserving protocols, and distributes updated global models back to participants as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Architecture for Collaborative IDS.

The FedPrIDS architecture incorporates several key design principles. First, the system employs a modular design that enables independent operation and upgrade of individual components. Second, the architecture implements security controls at multiple layers, including secure communication channels, authenticated participant verification, and encrypted parameter transmission protocols. Third, the system incorporates adaptive mechanisms that can dynamically adjust privacy parameters and learning strategies based on evolving threat landscapes and organizational requirements.

3.3. Global Model

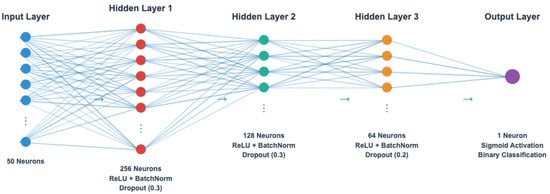

The global model employs a deep neural network architecture optimized for binary classification of raw network traffic as either benign or malicious. The architecture consists of multiple hidden layers with decreasing dimensions to capture hierarchical feature representations and complex attack patterns. We employ a multi-layer feedforward neural network architecture [24,25] with three hidden layers containing 256, 128, and 64 neurons, respectively, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

FedPrIDS’s Neural Network Architecture.

As shown in Algorithm 1, the federated model incorporates regularization techniques, including batch normalization for training stability, dropout to prevent overfitting, and ReLU activation functions for computational efficiency. Dropout regularization [26] is applied with rates of 0.3 for the first two hidden layers and 0.2 for the output layer to prevent overfitting. The final output layer uses sigmoid activation to produce probability scores for binary classification, allowing flexible threshold adjustment for different organizational security policies.

| Algorithm 1 Global Model Initialization and Update |

Require: Number of features d, Hidden dimensions Ensure: Initialized global model 1: Initialize global model parameters randomly 2: 3: 4: 5:

6: for round to T do 7: Broadcast to all participants 8: Collect local updates from organizations 9: Secure aggregation() 10: end for 11: return

|

3.4. Local Model Architecture and Training

Each participating organization maintains a local model that mirrors the federated model architecture while being trained exclusively on the organization’s private data. The local model serves as the primary interface between organizational data and the federated learning process, ensuring that sensitive information never leaves organizational boundaries.

As shown in Algorithm 2, local models are initialized with the current global model parameters at the start of each federated round. Organizations then perform local training using their private (labeled) network data for a specified number of epochs, allowing the model to adapt to organization-specific threat patterns and data characteristics while maintaining compatibility with the global model structure. The training process is designed to balance model performance with privacy preservation and computational efficiency. The training process incorporates advanced optimization techniques, including adaptive learning rate scheduling, gradient clipping for stability, and differential privacy noise injection for privacy protection. The binary cross-entropy loss function is optimized using the Adam optimizer [27] with carefully tuned hyperparameters, as detailed in Table 2.

| Algorithm 2 Local Model Training with Privacy Protection |

Require:

Global model , Local dataset , Local epochs E, Learning rate , Privacy parameters Ensure:

Updated local model 1: 2:

Initialize optimizer with learning rate 3:

Compute noise scale: where 4:

for epoch to E do 5:

for each batch in do 6:

7: 8:

Compute gradients: 9:

Apply gradient clipping: 10:

Add DP noise: 11:

Update parameters: 12:

end for 13:

Update learning rate: 14: end for 15: return

|

The local training process implements privacy protection mechanisms based on differential privacy principles. Gradient clipping (Line 9) ensures that individual gradient contributions are bounded according to:

where is the clipping threshold, preventing the leakage of sensitive information through gradient magnitudes.

Calibrated noise injection (Line 10) provides formal privacy guarantees while maintaining the utility of the model for threat detection. The noise scale is computed as follows:

where Gaussian noise is added to the clipped gradients. This mechanism ensures -differential privacy with

- : privacy budget controlling the privacy–utility trade-off.

- : failure probability (typically ).

- C: gradient clipping bound ensuring bounded sensitivity.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter configuration for local model training with notation.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter configuration for local model training with notation.

| Parameter | Notation | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Parameters | |||

| Learning Rate (initial) | 0.001 | Adam optimizer initial learning rate | |

| Learning Rate Decay | 0.95 | Exponential decay factor per epoch | |

| Batch Size | B | 128 | Training batch size |

| Local Epochs | E | 5 | Epochs per federated round |

| Weight Decay | 1 | L2 regularization coefficient | |

| Adam Beta Parameters | 0.9, 0.999 | Adam optimizer momentum parameters | |

| Neural Network Architecture | |||

| Dropout Rate (Layers 1–2) | 0.3 | Dropout probability for hidden layers | |

| Dropout Rate (Layer 3) | 0.2 | Dropout probability for output layer | |

| Hidden Layer Neurons | 256, 128, 64 | Neural network layer dimensions | |

| Input Features | d | Variable | Number of input features per dataset |

| Privacy and Security Parameters | |||

| Privacy Budget | 0.5–2.0 | Differential privacy epsilon parameter | |

| Privacy Failure Prob. | 1 | Differential privacy delta parameter | |

| DP Noise Scale | Variable | Differential privacy noise std deviation | |

| Gradient Clip Norm | C | 1.0 | Maximum gradient norm for clipping |

| Federated Learning Configuration | |||

| Organizations | N | 5 | Total participating organizations |

| Federated Rounds | T | 20 | Total federated learning rounds |

| Data Weight | Variable | Data size-based aggregation weight | |

| Performance Weight | Variable | Performance-based aggregation weight | |

| Weight Factors | 0.7, 0.3 | Data and performance weight coefficients | |

| Feature Selection Parameters | |||

| Variance Threshold | 0.01 | Minimum variance for feature selection | |

| Correlation Threshold | 0.9 | Maximum correlation for feature removal | |

| Target Features | k | Variable | Selected features per dataset |

Organizations with different privacy requirements implement varying levels of privacy protection. Some organizations in the sharing group, for example, Financial and Healthcare, may employ stricter privacy parameters (), while other organizations may use more relaxed parameters (). This helps maximize collaborative learning benefits while maintaining adequate privacy protection for each organization independently. The local training process incorporates privacy protection mechanisms, including gradient clipping and differential privacy noise injection, ensuring that the local model updates cannot reveal sensitive information about individual data points or organizational security characteristics while maintaining model utility for threat detection.

3.5. Feature Extraction and Data Processing

FedPrIDS implements a hybrid feature selection mechanism that aims to reduce pre-processing time while maintaining high-quality feature representations for threat detection. The feature extraction process is designed to handle the very large scale of raw network data inputs efficiently while preserving critical information for accurate attack classification. This hybrid feature selection approach combines multiple complementary techniques to help identify the most informative features contributing to threat detection. As detailed in Algorithm 3, the process begins with (a) variance filtering (fast) to remove features with minimal variation, followed by (b) correlation analysis to eliminate redundant features, and concludes with (c) mutual information-based selection to identify features with maximum discriminative power for attack detection.

| Algorithm 3 Optimized Hybrid Feature Selection |

Require:

Raw features , Target labels , Target features k Ensure:

Selected features 1: Step 1: Lightning Variance Filter 2: Compute feature variances: for 3: Remove low-variance features: 4: Step 2: Correlation Analysis 5: Compute correlation matrix: 6:

Remove highly correlated features: 7:

Step 3: Mutual Information Selection 8: Compute MI scores: for each feature 9: Select top-k features: 10:

11:

return

|

The preprocessing pipeline achieves speed improvements through the optimized implementation of statistical computations, vectorized operations, and intelligent caching strategies. This approach helps reduce feature dimensionality while attempting to maintain critical information for attack classification. A motivation for this approach, and corresponding future work evaluation, is that this approach will enable real-time deployment.

Data preprocessing includes comprehensive cleaning procedures to handle missing values, infinite values, and data type inconsistencies commonly found in network traffic datasets. The framework employs robust imputation strategies using median values for numerical features and mode values for categorical features, ensuring that data quality issues do not compromise model performance. A potential drawback of this stage, and ML-based detection in general, is that FedPrIDS may fail at detecting attacks that purposely include rare or invalid network data. That said, these type of attacks are very likely to be more effectively and efficiently detected by classic network IDS rulesets.

3.6. Model Aggregation

Model aggregation combines local model updates from different organizations into an improved global model, of the same structure, while maintaining privacy and security. FedPrIDS uses a weighted aggregation approach that considers how much data each organization contributes and how well their local models perform. The aggregation process works as follows:

First, the system receives encrypted model updates from all participating organizations and decrypts them. Then it checks for outlier models that might be corrupted or malicious by comparing each model to the median model using statistical distance measures. The system then calculates weights for each organization. Organizations with more training data are assigned higher data weights, while organizations whose models perform better receive higher performance weights. The final weight combines these factors using a 70-30 split (as used on line 16 in Algorithm 4), where data size counts for 70% and performance counts for 30%. This ratio was chosen through testing different combinations. After computing weights, the system creates the new global model by taking a weighted average of all local model parameters. Each parameter in the neural network is updated by combining the corresponding parameters from all organizations according to their calculated weights. Finally, FedPrIDS tests the new global model on validation data. If the new model performs significantly worse than the previous version, the system rejects the update and keeps the old model. Currently, the tolerance threshold is set to 5%, meaning the new model may be slightly worse but not dramatically worse than the current model; This threshold may be adjusted as needed.

| Algorithm 4 Weighted Model Aggregation with Security Measures |

Require:

Local models , Data sizes , Performance losses Ensure: Updated global model 1:

Security Pre-processing: 2: Receive encrypted model updates using secure aggregation protocol 3: Decrypt model parameters with authenticated organizational keys 4: Outlier Detection: 5: for each model do 6: Compute median model: 7: Compute distance: 8: Compute MAD: 9: if then 10: Mark as outlier and exclude from aggregation 11: end if 12: end for 13: Compute Aggregation Weights: 14: ▹ Data contribution weight 15: ▹ Performance quality weight 16: ▹ Combined weight 17: ▹ Normalized final weight 18: Weighted Parameter Aggregation: 19: Initialize: 20: for each parameter layer p in neural network do 21: 22: end for 23: Model Integrity Verification: 24: Evaluate aggregated model on validation data: 25: Get previous round loss: 26: Set tolerance threshold: ▹ 5% degradation tolerance 27: if

then 28: Reject current aggregation 29: ▹ Revert to previous model 30: end if 31: return

|

4. Implementation

4.1. Fictitious Organizational Scenario

To simulate a multi-organizational scenario, we created five fictitious organizations with varying threat profiles, privacy requirements, and data quality estimates. The Financial organization represents a financial institution with stringent privacy requirements and high data quality. This organization may face sophisticated targeted attacks and may need to maintain strict regulatory and compliance requirements. This organization may be the target of attacks with an emphasis on financial sector threats, including advanced persistent threats, credential theft, and regulatory compliance violations. The Technology corporation represents a medium-security technology company with moderate privacy requirements and good data quality. This organization may face diverse attack exposure and may need to balance collaboration benefits with privacy protection. The Technology Corporation may experience high volumes of reconnaissance attacks, intellectual property theft attempts, and supply chain compromises. The Healthcare organization represents a highly regulated healthcare organization with maximum privacy requirements and moderate data quality. This organization may prioritize patient data protection while participating in collaborative threat intelligence. The Healthcare organization may face ransomware attacks, data breach attempts, and compliance-related security incidents. The Government agency represents with the highest privacy requirements and high data quality. This organization may handle sensitive or classified information and requires the strongest privacy guarantees. In our case study, the Government organization may experience sophisticated nation-state attacks, espionage attempts, and critical infrastructure targeting. The University represents an educational institution with medium privacy requirements and moderate data quality. This organization may prioritize collaboration and knowledge sharing while maintaining basic privacy protections. In our case study, University may face student-related security incidents, research data theft, and academic network compromises.

4.2. Implementation Details

FedPrIDS was implemented using PyTorch (version 2.2.0) with custom extensions for differential privacy, secure aggregation, and preprocessing. The experimental configuration includes 20 federated learning rounds with 5 local epochs per round across all three datasets. Each organization trains locally using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and adaptive learning rate scheduling. Batch size was set to 128 for optimal balance between computational efficiency and model convergence. The feature selection process was adapted for each dataset, reducing CIC-IDS-2017 from 78 to 50 features, UNSW-NB15 from 42 to 30 features, and Bot-IoT from 115 to 80 features.

Privacy protection is implemented through a differential privacy mechanism with organization-specific epsilon values ranging from 0.5 to 2.0. This based on an organizational privacy vs. detection accuracy contribution trade-off tolerance. The privacy budget component allocates resources based on threat level and this tolerance. Gradient clipping is applied with maximum norm of 1.0. Calibrated Gaussian noise was added before model aggregation.

5. Results

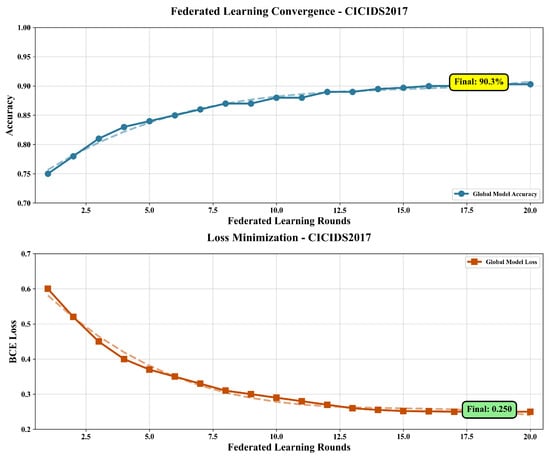

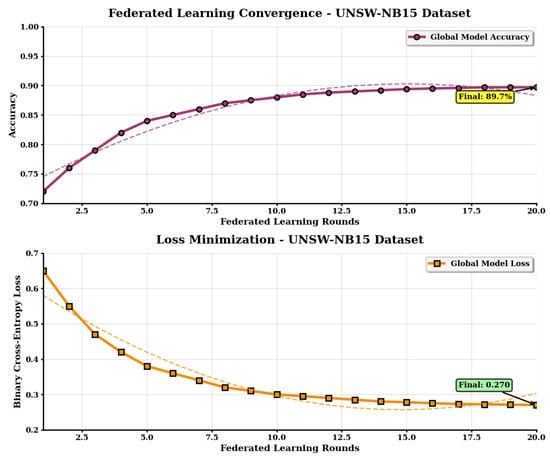

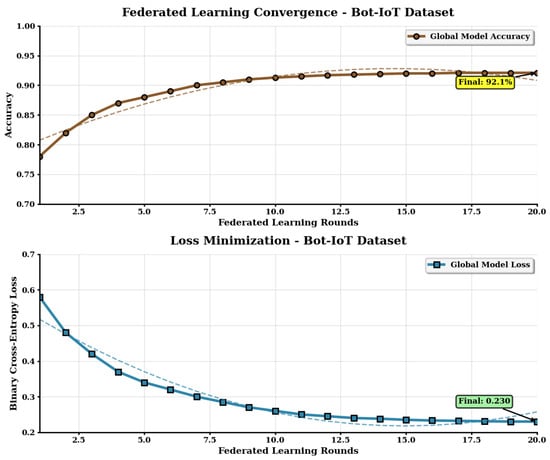

We tested our federated learning system on three different datasets. The training progress is shown in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Training convergence for the CIC-IDS-2017 dataset. Overlapping lines correspond to the local (dashed) versus global (solid) model accuracy.

Figure 4.

Training convergence for the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Overlapping lines correspond to the local (dashed) versus global (solid) model accuracy.

Figure 5.

Training convergence for the Bot-IoT dataset. Overlapping lines correspond to the local (dashed) versus global (solid) model accuracy.

Table 3 compares performance between original and selected features. Our hybrid feature selection approach achieved 37–43% reduction in pre-processing time with minimal accuracy loss (0.12–0.15%), demonstrating effective dimensionality reduction while preserving detection capability. FedPrIDS achieved the following detection accuracy: 90.3% in the CIC-IDS-2017 dataset, 89.7% in the UNSW-NB15 dataset, and 92.1% in the Bot-IoT dataset. For the CIC-IDS-2017 dataset, feature selection took 3.01 s. The UNSW-NB15 dataset needed 1.85 s, and Bot-IoT required 4.73 s.

Table 3.

Performance original vs. selected features.

The training curves in the figures show that all organizations learned together successfully. Each round of training improved the overall model performance. The system worked well regardless of what types of attacks were in the data or how the attack data was distributed across different organizations.

Table 4 shows how different types of organizations performed in our system. Some organizations like Financial and Healthcare needed stronger privacy protection, while others were more flexible. Despite these differences, all organizations benefited from the resulting collaborative learning about threats.

Table 4.

Detection accuracy, privacy analysis, and performance comparison between individual and federated learning across organizations and datasets.

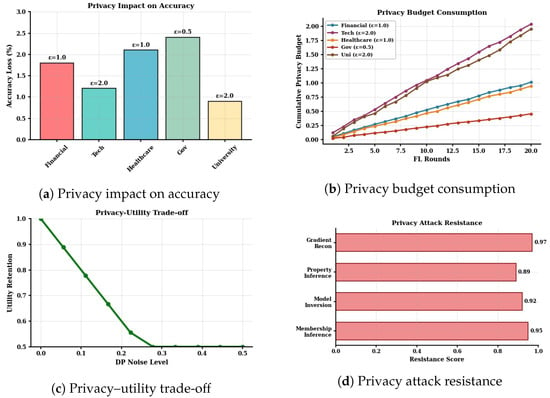

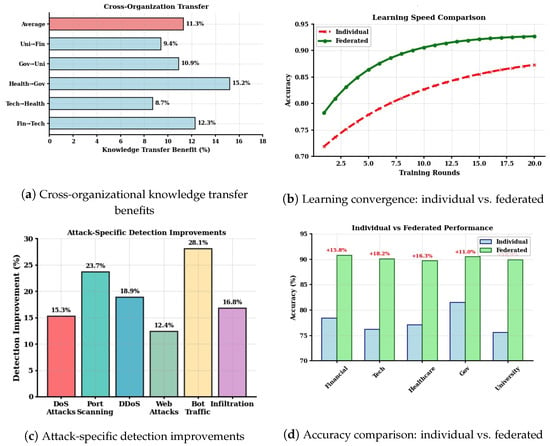

Figure 6 demonstrates that adding privacy protection did not significantly hinder performance. Even with the strongest privacy settings, accuracy dropped by less than 2.5%. This shows that it is possible to provide privacy assurances while still being able to receive improved attack detection accuracy afforded by shared intelligence. Figure 7 shows the main advantage of our approach. Organizations that participated in federated learning performed 8% to 15% better than organizations that tried to learn alone. This means that sharing knowledge through our privacy-preserving system may offer benefits to all participants.

Figure 6.

Privacy analysis.

Figure 7.

Federated learning performance analysis across multiple dimensions.

The system successfully detected many different types of cyber-attacks. It found traditional network attacks in CIC-IDS-2017, modern attacks in UNSW-NB15, and IoT-specific threats in Bot-IoT. This shows that our federated learning approach works across different types of cybersecurity challenges. All organizations completed their training within reasonable time limits. The total experiment time was about 75 min for CIC-IDS-2017, 47 min for UNSW-NB15, and 99 min for Bot-IoT. These times include all 20 rounds of federated training.

5.1. Benefits and Costs

We quantify the benefits and costs of federated collaboration using three key metrics: Privacy Loss (%) measures the accuracy degradation caused by differential privacy mechanisms:

Collaboration Gain (%) quantifies the improvement from federated learning compared to isolated training:

Net Benefit (%) represents the overall advantage considering both gains and losses:

Privacy levels are categorized based on the epsilon () parameter: maximum (), high (), medium (), and low (). While Technology and University both use , Technology is classified as medium due to its 90% data quality providing stronger inherent privacy protection, whereas University with 80% data quality is classified as having a low privacy level.

5.2. Organization-Specific Performance Analysis

Table 4 shows the specific results for each organization type across all three datasets. Each fictitious organization had different data quality levels and privacy requirements, which affected their performance in different ways.

The Financial fictitious organization achieved strong results across all datasets with accuracies of 90.8% on CIC-IDS-2017, 89.4% on UNSW-NB15, and 92.3% on Bot-IoT despite using strict privacy settings ( = 1.0). We believe this is a result of the assumed high data quality (95%). Financial’s results were consistently above the overall system average, showing that high-quality data may compensate for stronger privacy protection. Financial was effective at detecting sophisticated attacks, with its Bot-IoT performance being the second-highest among all organizations.

The fictitious organization Technology showed balanced performance, with 90.1% accuracy on CIC-IDS-2017, 89.9% on UNSW-NB15, and 92.0% on Bot-IoT. It uses moderate privacy settings (= 2.0) and having good data quality (90%). Technology achieved stable results across different attack types and performed well on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, which contains modern attack vectors relevant to technology environments.

The detection capabilities of the fictitious organization Healthcare included 89.7% accuracy on CIC-IDS-2017, 89.1% on UNSW-NB15, and 91.8% on Bot-IoT, even with high privacy protection ( = 1.0) and lower data quality (85%). Healthcare still achieved good results and showed particular strength in IoT threat scenarios (Bot-IoT).

The fictitious Government Agency achieved the best overall performance with 90.5% accuracy on CIC-IDS-2017, 89.6% on UNSW-NB15, and 92.5% on Bot-IoT. Despite using the strongest privacy protection ( = 0.5), the Government organization achieved the highest Bot-IoT accuracy among all participants.

The University fictitious organization contributed effectively, with 89.9% accuracy on CIC-IDS-2017, 90.2% on UNSW-NB15, and 91.9% on Bot-IoT. Using flexible privacy settings ( = 2.0), University achieved the highest UNSW-NB15 accuracy despite having the lowest data quality (80%). This indicates that relaxed privacy settings may help overcome data quality limitations in collaborative learning environments.

In our experiment, the fictitious organizations with higher data quality generally performed better, but privacy settings also played a significant role. The Government and Financial fictitious organizations, despite having strict privacy requirements, achieved excellent results likely due to their high-quality data assumptions. The University, with the lowest data quality, still performed competitively by using more flexible privacy settings.

Across all datasets, the performance differences between fictitious organizations were relatively small (within 1–2%), indicating that federated learning successfully enabled collaborative learning while accommodating different organizational privacy requirements. All fictitious organizations performed better than isolated (non-collaborative) learning approaches, with improvements ranging from 8% to 15% compared to training alone (non-federated).

The corresponding generated raw network dataset for each organization was created by categorizing and separating the data in the three datasets according to attack types. The public datasets used were collected from real organizations but may not necessarily represent the same types of organizations nor possess the same ratio of data to organization mapping we used in our experiments.

5.3. Privacy Preservation Analysis

The privacy preservation analysis demonstrates that our differential privacy implementation successfully preserves organizational data confidentiality while maintaining effective collaborative threat detection capabilities. The privacy–utility trade-off analysis reveals balance points may enable maximizing collaborative benefits while ensuring adequate privacy guarantees for sensitive data across different organizational contexts.

As shown in Figure 6, organizations with high privacy requirements successfully maintained good privacy guarantees. FedPrIDS’s adaptive privacy budget management approach effectively allocated allowances across different datasets while maintaining adequate protection levels for sensitive organizational data. The privacy budget consumption remained well within acceptable limits across all organizational types and evaluation scenarios. The differential privacy noise injection mechanism demonstrated minimal impact on detection performance across all datasets.

Formal privacy accounting validates that the differential privacy guarantees are maintained throughout the federated learning process. Figure 6 shows that adding privacy protection did not significantly hampered detection accuracy. In our experiment, with the strongest privacy settings, accuracy dropped by about 2.5%.

5.3.1. Knowledge Transfer and Attack-Specific Improvement

Figure 7 illustrates the benefits of federated learning through multiple analytical perspectives. Knowledge Transfer Benefit (%) in Figure 7a quantifies the cross-organizational learning impact. For each organization pair , we calculate

where represents organization j’s accuracy when learning collaboratively with organization i, and represents j’s accuracy in isolated training. Higher values indicate greater knowledge transfer from organization i to j.

Attack-specific detection improvements in Figure 7c measure detection enhancement for each attack category:

This metric reveals which attack types benefit most from collaborative learning. Attack categories showing larger improvements indicate where federated knowledge sharing provides the greatest security enhancement.

5.3.2. Federated Learning Benefits

Our experimental design includes comparative analysis between individual organizational learning and federated collaborative learning across all three datasets. Individual organizations training in isolation achieve substantially lower performance compared to federated participants, with accuracy improvements ranging from 8% to 15% when organizations participate in federated learning. These improvements demonstrate that collaborative learning provides tangible security benefits that justify the complexity of federated deployment. As shown in Figure 7, the collaborative learning approach provides measurable improvements across all organizational types and attack scenarios used in our case study.

6. Limitations

The machine learning approach used for training and evaluating FedPrIDS requires labeled network data, where each data sample is marked as either an attack (with its specific type) or benign traffic. This labeling requirement creates a significant challenge for real-world deployments, particularly when implementing the proposed continuous improvement approach. In practice, obtaining accurately labeled network data on an ongoing basis is difficult and resource-intensive. One possible solution to address this labeling challenge would be to enhance existing IDS systems and security operations center tools with capabilities to automatically label network data as they process it. By enriching these established tools with labeling functionality, organizations could generate the necessary labeled datasets for continuous model training without requiring extensive manual effort. However, this approach itself would require careful implementation to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the automated labels.

Note that FedPrIDS was designed not to replace classic (rule-based) network intrusion detection systems [19] like Snort [28], Suricata [29], and Bro/Zeek [30] but instead to work as a complementary system. Both types of IDSs, rule-based and ML-based, have advantages and disadvantages, and we believe they should be used in combination for optimal results. We believe that these contributions show that it is possible to efficiently and effectively share network intrusion detection intelligence while preserving data privacy and, at the same time, increasing the effectiveness of network intrusion detection (NIDS) within a rapidly changing threat landscape.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This article presented FedPrIDS: a privacy-preserving technology for collaborative network intrusion detection and an evaluation of its capabilities. FedPrIDS integrates federated and adaptive machine learning, differential privacy, network intrusion detection, and computational optimization techniques. Experimental evaluation demonstrated detection accuracy gains while maintaining privacy guarantees. FedPrIDS shows that organizations should be able to achieve significant improvements in time-to-detection through collaborative learning while also adequately addressing privacy concerns.

Future research directions include (a) evaluations with larger and more recent datasets to further validate generalizability, (b) analysis of the feasibility and stability of the continuous learning approach, (c) improvements on speed and efficiency with a focus on real-time analysis, (d) evaluation of approaches for successful integration with existing security operations technologies and processes, and (e) evaluation of deployment scenarios across diverse industry sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.M. and B.P.R.; methodology: S.M., D.C.d.L. and B.P.R.; software: S.M.; data curation: S.M.; validation: S.M.; analysis: S.M.; writing—original draft: S.M.; writing—review and editing: S.M., D.C.d.L. and B.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the State of Idaho.

Data Availability Statement

To enable full reproducibility of our work and results and also enable further improvements, we have made the data and code for this work publicly available. Readers may find an archived version of FedPrIDS and the experimental setup as described in this article on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/17237758, accessed on 30 September 2025. The latest version may be found on GitHub (Version 1.0) at https://github.com/sameermankotia/Fedrated_Learning, accessed on 30 September 2025.

Acknowledgments

AI-based language and grammar aiding tools (Grammarly and Overleaf Writefull, Versions: September 2025) were used during the preparation and editing of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- BitLyft Cybersecurity. Why Traditional Security Methods May No Longer Be Enough. Available online: https://www.bitlyft.com/resources/why-traditional-security-methods-may-no-longer-be-enough (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bhuyan, M.H.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Network Anomaly Detection: Methods, Systems and Tools. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.y. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; Volume 54, pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janati Idrissi, M.; Alami, H.; El Mahdaouy, A.; El Mekki, A.; Oualil, S.; Yartaoui, Z.; Berrada, I. Fed-ANIDS: Federated Learning for Anomaly-based Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 234, 121000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Sarkar, S.; Aouedi, O.; Yenduri, G.; Piamrat, K.; Alazab, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Gadekallu, T.R. Federated Learning for Intrusion Detection System: Concepts, Challenges and Future Directions. Comput. Commun. 2022, 195, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Teng, J.; Yu, S. Multi-Task Network Anomaly Detection using Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam, 4–6 December 2019; pp. 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Marchal, S.; Miettinen, M.; Fereidooni, H.; Asokan, N.; Sadeghi, A.R. DÏoT: A Federated Self-learning Anomaly Detection System for IoT. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 July 2019; pp. 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Tout, H.; Talhi, C.; Mourad, A. Internet of Things Intrusion Detection: Centralized, On-Device, or Federated Learning? IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri-Zarandi, M.; Dara, R.A.; Lin, X. SIDS: A Federated Learning Approach for Intrusion Detection in IoT Using Social Internet of Things. Comput. Netw. 2023, 228, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chethun. CIC-IDS-2017 Network Intrusion Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chethuhn/network-intrusion-dataset (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Wells, D. UNSW-NB15 Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mrwellsdavid/unsw-nb15 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Venkateswaran, V. Bot-IoT Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vigneshvenkateswaran/bot-iot (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy. Found. Trends Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated Machine Learning: Concept and Applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qatf, M.; Lasheng, Y.; Al-Habib, M.; Al-Sabahi, K. Deep Learning Approach Combining Sparse Autoencoder with SVM for Network Intrusion Detection. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52843–52856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnakian, F.; Heikkonen, J. A Deep Auto-Encoder Based Approach for Intrusion Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2018 20th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Chuncheon, Republic of Korea, 11–14 February 2018; pp. 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrak, S.; İskefiyeli, M. Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection From Network Flow Features Using Variational Autoencoder. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108346–108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharewal, S.; Ashfaque, M.W.; Banu, S.S.; Uma, P.; Hassen, S.M.; Shabaz, M. Intrusion Detection System for Industrial Internet of Things Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9023719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajjar, E.; Maxwell, P.; Bastian, N. Adversarial Machine Learning in Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 186, 115782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical Secure Aggregation for Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zou, T.; Pu, Y.; He, Y.; Ye, X. Vertical Federated Learning: Concepts, Advances, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 3615–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kang, Y.; Xing, C.; Chen, T.; Yang, Q. A Secure Federated Transfer Learning Framework. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2020, 35, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Snort Project. Snort—Network Intrusion Detection Prevention System. Open Source Intrusion Prevention System. Available online: https://www.snort.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Open Information Security Foundation. Suricata: Open Source Threat Detection Engine. Available online: https://suricata.io/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Zeek Project. Zeek Network Security Monitor. Available online: https://zeek.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.