Abstract

Recent years have seen a disconnect between much-needed real-world skills and knowledge imparted to cybersecurity graduates by higher education institutions. As employers are shifting their focus to skills and competencies when hiring fresh graduates, higher education institutions are facing a call to action to design curricula that impart relevant knowledge, skills, and competencies to their graduates, and to devise effective means to assess them. Some institutions have successfully engaged with industry partners in creating apprenticeship programs and work-based learning for their students. However, not all educational institutions have similar capabilities and resources. A trend in engineering, computer science, and information technology programs across the United States is to design project-based or scenario-based curricula that impart relevant knowledge, skills, and competencies. At our institution, we have taken an innovative approach in designing our cybersecurity courses using scenario-based learning and assessing knowledge, skills, and competencies using scenario-guiding questions. We have used the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Hiring Cybersecurity Workforce report for skills, knowledge, and competency mapping. This paper highlights our approach, presenting its overall design and two example mappings.

1. Introduction

The increasing call to action for higher education institutions to impart relevant skills, knowledge and competencies to their graduates is leaving a footprint in cybersecurity education. There is a real disconnect between what students are learning and what is expected of them in the real-world, pushing higher education institutions to adopt innovative learning and teaching strategies. Sometimes, a lack of industry partnerships and other resources are limiting institutions in terms of the design of practical, work-based learning. However, many academics have been engaged in designing and delivering project-based and/or scenario-based curricula that impart relevant knowledge, skills, and competencies. Another challenge that academic programs are facing is how to realistically assess competencies and skills. Traditional approaches such as exams, quizzes, and laboratory exercises can only achieve so much, leaving a gap regarding what students are learning and what their employers expect of them. Moreover, many employers are also shifting their focus to competency-based hiring [1], which places an enormous pressure on higher education institutions to design, deliver, and assess relevant and rigorous curricula. Fortunately, the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2,3], the Office of Personnel Management’s report on Attracting, Hiring, and Retaining a Federal Cybersecurity Workforce [4], and the Cybersecurity Competency Model [5] provide some good reference frameworks that institutions can start with.

Recently, NIST published a draft NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework Competencies—request for public comments [6] in which competency is defined as “as a mechanism for organizations to assess learners”. They also released an initial draft of competencies—technical, professional, organizational and leadership—to accompany the draft framework. The public comment space is centered around the following questions:

- Should the NICE Framework work roles and competencies be addresse d separately or in tandem?

- Some competencies have been defined as type “professional”. Should these be included in the NICE Framework competencies? Should they be included as knowledge and skills statements?

- Should proficiency levels be incorporated in the NICE Framework Competencies? If yes, then how?

- Is the provision of different competency types useful?

2. Competency Framework

The NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2], and its subsequent revision [3], serve as fundamental references and resources for describing and sharing information about cybersecurity work roles and the knowledge, skills, and tasks (KSTs) needed for those roles that can strengthen the cybersecurity posture of an organization. The framework organizes cybersecurity work roles into seven categories, namely, Securely Provision, Operate and Maintain, Oversee and Govern, Protect and Defend, Analyze, Collect and Operate, and Investigate, and identifies the KSTs needed for each work role. The complete list of KSTs for each work role can be found in [2] and [3]. The framework serves as a vital resource to bridge the gap between education and industry by providing a common lexicon for organizations to identify and recruit for cybersecurity work roles, and for education and training programs to identify the KSTs and prepare professionals for KSTs and competencies required for those roles. A revised framework was published in November 2020 [3].

The U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) published a report on Attracting, Hiring, and Retaining a Federal Cybersecurity Workforce [4] in October 2018, in which they discussed their Cybersecurity Competency Model. The model was developed using the following two categories based on OPM’s collaboration with the National Security Council Interagency Policy Committee Working Group on cybersecurity education and workforce issues.

- IT infrastructure, operations, computer network defense and information assurance

- Domestic law enforcement and counterintelligence

The set of competencies was created by surveying a select group of employers in various occupations related to cybersecurity. The entire list of competencies can be found in Appendix B of the OPM report [4]. The scenarios that we have created are mapped to these competencies, as described in the next section.

The Cybersecurity Competency Model [5] was created by the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) in collaboration with the Department of Homeland Security and the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) to develop a comprehensive competency model for the cybersecurity workforce. The Cybersecurity Competency Model defines the latest skill and knowledge requirements needed by individuals to improve the security posture of their organizations. The model incorporates competencies identified in the NICE National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework and complements the framework by including competencies needed by the workforce and those needed by cybersecurity professionals.

In the following sections, we discuss related work on competency assessment and describe scenario-based learning and our approach of using scenario-based learning technique to assess competencies. We illustrate our approach with two example competencies from the competency frameworks discussed in this section.

3. Related Work on Competency Assessment

In [7], the authors conducted an evaluation of a novel computerized competency-based assessment of computational thinking. The assessment process draws upon a multidisciplinary approach by combining psychometrics, learning sciences, and computing education. Further, the approach utilizes both summative and formative assessments to generate constructive and personalized reports for learners.

A competency assessment model for engineering education using discussion forums was proposed by Felicio and Muniz in [8]. In this model, the evaluation feedback is defined by utilizing the Rubrics scoring tool and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Related to this work is an ontological knowledge assessment model proposed by Zulfiya, Gulmira, Assel and Altynbek in [9]. In this model, assessments of student competencies at the level of the educational program are undertaken at two lower levels: modules and discipline.

In [10], Grann and Bushway present a visualization of assessed competency using a competency map. The authors argue that MBA students who utilize the competency map demonstrate elevated competency levels and make progress at a greater rate compared to their peers who have not used the visual tool. A study on the competencies of data scientists was presented by Hattingh, Marshall, Holmner and Naidoo in [11]. Their findings were grouped into six competency themes: organizational, technical, analytical, ethical and regulatory, cognitive, and social. Using a thematic analysis, a unified model of data science competency was developed. This is a seminal work for the conceptual development of competency in the discipline, and could contribute to the improvement of the data science workforce.

In an article published in the Infragard journal, Watkins et al. argued that the competency-based learning approach “focuses on mastering each critical knowledge and skill component before moving on to the next one without being constrained to a fixed time period”, in contrast to the outcome-based approach which attempts to impart knowledge and skill components within a fixed time period with the objective of reaching a passing level of competence [12].

In [13], Brilingait, Bukauskasa, and Juozapaviciusb proposed a framework using cyber defense exercises as competency-based approach for cybersecurity education, and an assessment framework to measure competency. The framework consists of a sequence of steps for team formation, determination of objectives for each team, exercise flow, and formative assessments based on surveys. Exercises or competitions, as they were proposed in the paper, are deemed to be effective tools for hands-on, competency-based learning. However, they have one major drawback, i.e., they typically provide a learning environment for experienced students and do not, by design, build on one another, from beginner to advanced knowledge levels, unless they are designed to achieve those goals. Further, most of the time, it is not feasible to design competitions in this manner.

These diverse writings on competency assessment underscore the significance of competency-based learning and competency assessment in the learning process. The U.S. Department of Education has emphasized the importance and need for competency-based learning, and has articulated that “by enabling students to master skills at their own pace, competency-based learning systems help to save both time and money. Depending on the strategy pursued, competency-based systems also create multiple pathways to graduation, make better use of technology, support new staffing patterns that utilize teacher skills and interests differently, take advantage of learning opportunities outside of school hours and walls, and help identify opportunities to target interventions to meet the specific learning needs of students” [14]. In this paper, we present our approach for the design of scenario-based, competency-focused learning, and introduce a methodology with which to assess competency through scenarios.

4. Scenario-Based Learning

Scenario-based learning is firmly based on the theory of contextual learning, i.e., that learning takes place in a context in which it is applied. It subscribes to the idea that knowledge is best acquired and fully understood when situated within its proper context. Using real-life situations, scenario-based learning provides a relatable and relevant learning experience through an immersive and highly engaging approach [15]. Scenario-based learning works best for training when tasks are set that involve serious consequences, which is apt for the field of cybersecurity. It offers a simulated environment or situation in which learners can afford to make mistakes without serious repercussions. As noted by the authors of [16], “Scenario-based learning is grounded in the idea that students learn better through application of authentic tasks in a real-world context”. In [17], Iverson and Colky emphasized that scenario-based learning supports the constructivist view that learning is effective when students apply prior knowledge and construct meaning from that knowledge and experience. These constructs emphasize the need for scenario-based learning in disciplines like cybersecurity, where the application of knowledge within specific contexts is important for learning.

In [18], Clark proposes the following checklist for determining whether scenario-based learning is the right option:

- Are the outcomes based on skill development or problem solving?

- Does it provide a simulated experience in lieu of a real and dangerous situation?

- Are the students provided with relevant knowledge for decision making?

- Is a scenario based solution cost- and time-effective?

- Will the content and acquired skills be sufficiently relevant to justify their inclusion?

Based on the recent shift among employers to competency and skill-based hiring, and the disconnect between imparted knowledge and needed skills and competencies, it is proposed that scenario-based learning is an excellent option for cybersecurity education and training. In this paper, we outline our approach for the design of scenario-based learning to assess competencies in cybersecurity curricula. We also highlight two use cases with two example courses.

5. Assessing Competencies Using Scenario-Based Learning

One critical question that always needs to be answered is how do we determine whether the learning objectives have been satisfied? In today’s world, where skills and knowledge are being used interchangeably more and more, we need a mechanism to ensure that students gain the knowledge, skills, and competencies required to effectively perform their jobs.

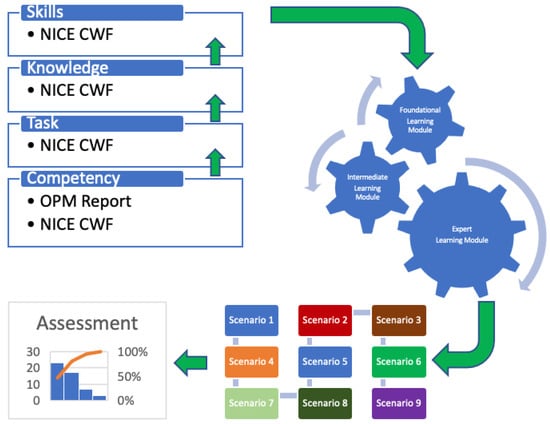

Although NIST published a draft of the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework Competencies [6] for public comments, a good starting point would be the US Office of Personnel Management’s report on Attracting, Hiring, and Retaining a Federal Cybersecurity Workforce [4] and list of competencies. Our approach to using scenario-based learning in assessing competencies is depicted in Figure 1, and may be summarized as follows:

Figure 1.

Scenario-Based Learning Implementation.

- Start from the definition of a selected competency from the OPM report [4]. Alternatively, a work role can be selected from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework revision 1 [3].

- Which tasks should be performed to satisfy that work role or competency? Choose a set of tasks from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2,3] related to that competency at all three levels (beginner, intermediate, expert).

- Which knowledge areas are required to perform the selected tasks? Choose knowledge areas from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2,3] related to the set of tasks at all three levels (beginner, intermediate, expert).

- Which skills are required to impart the desired knowledge? Choose skills from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2,3] related to the desired knowledge at all three levels (beginner, intermediate, expert).

- Create learning modules incorporating the knowledge areas, skills, and tasks starting at the beginner level and moving up to advanced level.

- Results in sequence of courses, starting from foundational course, leading to an intermediate-level course and culminating in a scenario-based experience.

- The scenario-based experience will follow the theory of contextual learning with tasks specifically designed to assess the overall competency.

- Knowledge, skills, and competencies will be assessed by designing appropriate scenario-guiding questions that students will have to answer as they progress through the scenarios.

6. Our Approach

We discuss two approaches with which to assess competencies using scenario-based learning, both of which map to the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [2,3]. In our first approach, we start with the knowledge, skills, and tasks that are used to satisfy the chosen competency. The scenarios are created with guiding questions that will lead students to work on the scenario and answer questions as they progress. Each answer is mapped to a set of knowledge, skills, and tasks, thus assessing whether the student is able to perform that task and has assimilated the relevant knowledge and skills. Our second approach follows the revised NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework [3] and starts with a work role corresponding to the chosen competency. We then list the tasks that are needed for that work role and to achieve the chosen competency, followed by sets of knowledge and skills needed to perform relevant tasks. Again, scenarios are designed to guide students through a set of tasks and to impart the knowledge and skills required to perform those tasks.

Although we did not map learning outcomes and tasks as suggested in Bloom’s taxonomy [19], our expectation is that each learning outcome mapped to a task from the NICE Framework will need to relate to the appropriate action verb in the Bloom’s taxonomy depending on the proficiency level and competency required for the corresponding work role. For example, for computer network defense competencies, tasks that are at an advanced proficiency level relate to either the ‘analyze’, ‘evaluate’, or ‘create’ action verbs. We leave it to the instructional designer to use appropriate learning outcomes mapped to NICE Framework tasks that relate to the Bloom’s taxonomy action verbs.

For each scenario, assessment instruments are designed and implemented to document the attainment of the learning objectives at an acceptable level, in accordance with policies of the institution/department/program. These instruments include questionnaires and a write-up describing the evolution of the compromise based on the analysis of digital artifacts. Each of the approaches is discussed in detail below, with examples.

6.1. Approach 1—Example on Network Defense

From the OPM report [4], we chose the following competency:

Competency: Computer Network Defense—Knowledge of defensive measures to detect, respond, and protect information, information systems, and networks from threats.

The scenario was created using two virtual machines: one a Kali Linux attacking machine and the other a Windows 7 victim machine. A vulnerable application running on Windows 7 was targeted for buffer overflow, and the machine was compromised using weaponized code. Several post-exploitation activities were carried out. Each step of the attack, starting from reconnaissance all the way to mission completion mapping to the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain [20], was supported with artifacts. The scenario was designed to have students investigate the artifacts, analyze and recreate the attack vector, and devise an appropriate countermeasure.

Our goal was to design the scenario and scenario guiding questions that would map to knowledge, skills, and tasks, and which would satisfy the chosen competency. The following knowledge, skills, and tasks (KST) that directly map to the competency were chosen from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework. Each KST is further classified into beginner, intermediate, and advanced based on its complexity (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Knowledge Skills and Tasks for Computer Network Defense.

Table 2 shows how the scenario questions are framed to assess KSTs and competencies following scenario-based learning. In addition, suggested sample artifacts are listed to guide the development of a staged laboratory setting.

Table 2.

Assessing KSTs and Competencies from Scenarios—Competency: Computer Network Defense.

6.2. Approach 2—Example on Threat Intelligence

From the OPM report [4], we chose Threat Intelligence Analysis and Threat Analyst as the competency and work role, respectively.

This scenario was also created using two virtual machines: a Kali Linux attacking machine and a victim Windows 2016 server machine. The Windows server machine was compromised using a malicious code downloaded on the machine. Several post-exploitation activities were carried out. Each step of the attack was backed up with artifacts in this scenario as well. The scenario was designed to have students investigate the artifacts, analyze and recreate the attack vector, create indicators of compromise, and package and share them using a threat sharing platform.

In this scenario, our goal was to design a scenario and scenario guiding questions that would map to the specific tasks required for the selected competency and work role, and then map to the knowledge and skills required to perform the relevant tasks. The knowledge, skills, and tasks (KST) shown in Table 3 were chosen from the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework that directly map to the relevant competency.

Table 3.

KSTs for Threat Analyst work role.

Table 4 shows how the scenario questions are framed to assess KSTs and competencies from scenario-based learning. Suggested sample artifacts are listed to guide the development of a staged laboratory setting for this particular scenario.

Table 4.

Assessing KSAs and Competencies from Various Scenarios—Competency: Threat Intelligence Analysis.

6.3. How Does Clark’s Checklist Apply to These Scenarios?

We discussed Clark’s checklist in a previous section as a tool for determining whether scenario-based learning is the right option for cybersecurity curriculum design. After discussing our example scenarios, we outline below how the checklist applies to those scenarios.

Both scenarios impart skills and knowledge to students by providing real-world examples and artifacts that would help them recreate cyberattacks and propose mitigating solutions. Outcomes are very much skill-based and are mapped to cybersecurity competencies and tasks. The example scenarios provide students with artifacts based on real-world attacks instead of requiring them to install actual malware on their systems. The artifacts and scenario-guiding questions provide them with relevant knowledge to recreate the attacks at each stage of the cyber kill chain for appropriate decision making. In this sense, both scenarios are cost- and time-effective.

7. Competency Assessment Rubric

In order to properly assess competencies, a uniform rubric must first be developed and implemented. In Table 5, we apply the rubric as an assessment tool for computer network defense competency. This rubric is an adaptation of the student performance rubric developed in [21] by the Institute for the Development of Excellence in Assessment Leadership (IDEAL) for ABET. In the rubric, specific competency indicators are assessed based on four levels of competency. The assessment process is guided by the description provided for each pair of indicator-competency levels.

Table 5.

Competency Assessment Tool for Computer Network Defense.

The levels of competency are designed to be flexible and subjective. They are bound to be guided by the personal perspective or judgement of the evaluator. As long as these metrics are consistently and uniformly applied, we believe that they are fair and useful metrics. We resist linking these levels to numeric scores to avoid being prescriptive. Instead, we use qualitative terms such as “some”, “basic”, “advanced”, etc. Indicators of the levels of competency include “Unsatisfactory’, “Developing”, Satisfactory”, and “Exemplary.”

8. Preliminary Empirical Data

Preliminary evaluation data on the efficacy of the scenario-based cybersecurity learning approach were collected during an industrial control systems security course. Immediately following the course, participants completed in a post-course survey. The respondents (n = 10) overwhelmingly agreed that the scenario-based laboratory exercises were very helpful to their learning process. Anecdotal comments that were gathered included descriptive qualifiers such as “… reinforced some things that we have done and that we have not done.”, “… the exercises were a lot of help”, “they were really everything…”, “Overall the hands on were great”, “… through the exercises I now have a more thorough understanding” and “… were the most enlightening portion of the class.” Encouraged by these results, we will continue to use this approach and incorporate the assessment levels that were described in the previous section of this paper. However, we need to point out that this learning technique is just one component of a major project, i.e., the development of a cybersecurity competency assessment model, and should be regarded as such.

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

As employers are increasingly focusing on skills and competencies to assess their employees and hire new graduates, higher education institutions are facing a call to action to design curricula that impart relevant knowledge, skills, and competencies to their graduates, and to devise effective means to assess them. However, there is a lack of comprehensive measures regarding which metrics should be used to assess competencies and what constitutes an effective learning and assessment strategy to ensure that graduates obtain sufficient skills and knowledge to satisfy their employer’s needs. In this paper, we have discussed how to design scenario-based learning strategies for cybersecurity courses, and have devised a method to assess competencies using scenario-guiding questions and artifacts. We have designed and delivered a number of courses that use the strategy discussed in this paper and have presented some examples of scenario designs, scenario-guiding questions, and assessment rubrics.

In this paper, we presented examples of how to assess competencies using scenario-based learning. For a given scenario, we mapped the expected knowledge, skills, and tasks (KST). Although significant empirical data are yet to be collected, what we have provided is a foundation for a pedagogical process that is intended to be broadly applied. Using this seminal work, we intend to follow through with extensive data collection and evaluation, as described in the section on future research directions. We believe that the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- a preliminary evaluation of the efficacy of a scenario-based learning approach to cybersecurity;

- the construction of a competency assessment model based on existing frameworks and reports; and

- the assembly of a generic and functional assessment rubric for competency evaluation.

There is much to do in this domain. A comprehensive list of competencies needs to be developed; this would benefit employers and higher education institutions in terms of effectively assessing skills and competencies at various levels. Higher education institutions need to effectively design assessment tools and techniques with which to measure skills and competencies, and work closely with industry partners to evaluate the effectiveness of those tools and techniques. It is time to ask whether traditional lectures and lab-style delivery of courses are meeting the needs of today’s employers and imparting relevant skills and competencies to graduates.

Additional future directions for enhancing competency-based learning, particularly in the area of cybersecurity, include the following:

- develop a dynamic and artificial intelligence-based system that provides an effective learning path that is in line with the learner’s abilities;

- expand the data collection and evaluations of scenario-based learning approaches and identify possible actions for continuous improvement;

- design and implement digital and verifiable credentials for cybersecurity competency pathways that are industry-endorsed; and

- enable an effective communication mechanism and collaborative platform wherein industry and academia can actively and constantly communicate to address the competency gaps that evolve due to rapid technological advancements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, T.G. and G.F.III; investigation and resources, T.G. and G.F.III; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, G.F.III; project administration, T.G. and G.F.III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially supported by the National Security Agency under Grant Number H98230-20-1-0350, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) under grant number N00014-21-1-2025, and the National Security Agency under grant numbers H98230-20-1-0336 and H98230-20-1-0414. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the funding agencies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABET | Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology |

| ETA | Employment and Training Administration |

| IDEAL | Institute for the Development of Excellence in Assessment Leadership |

| KST | Knowledge, Skills, and Tasks |

| NICE | National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

References

- Competencies Hold the Key to Better Hiring. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/pages/0315-competencies-hiring.aspx (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework. NIST Special Publication 800-181. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-181.pdf?trackDocs=NIST.SP.800-181.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NICE) Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity. NIST Special Publication 800-181 Revision. 1. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-181r1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Interpretive Guidance for Cybersecurity Positions Attracting, Hiring and Retaining a Federal Cybersecurity Workforce. Available online: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/reference-materials/interpretive-guidance-for-cybersecurity-positions.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Cybersecurity Competency Model. Available online: https://www.careeronestop.org/competencymodel/competency-models/cybersecurity.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology NICE Framework Competencies: Assessing Learners’ Cybersecurity Work. NISTIR 8355. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8355/draft (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Lai, R.P.Y. The Design, Development, and Evaluation of a Novel Computer-based Competency Assessment of Computational Thinking. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Trondheim, Norway, 15–19 June 2020; pp. 573–574. [Google Scholar]

- Felicio, A.C.; Muniz, J. Evaluation model of student competencies for discussion forums: An application in a post-graduate course in production engineering. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiya, K.; Gulmira, B.; Assel, O.; Altynbek, S. A model and a method for assessing students’ competencies in e-learning system. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Data Science, E-Learning and Information Systems, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2–5 December 2019; Article 58. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Grann, J.; Bushway, D. Competency Map; Visualizing Student Learning to Promote Student Success. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 24–28 March 2014; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hattingh, M.; Marshall, L.; Holmner, M.; Naidoo, R. Data Science Competency in Organizations: A Systematic Review and Unified Model. In Proceedings of the ACM SAICSIT Conference (SAICSIT’19), Skukuza, South Africa, 17–18 September 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, A.B.; Tobey, D.H.; O’Brien, C.W. Applying Competency-Based Learning Methodologies to Cybersecurity Education and Training: Creating a Job-Ready Cybersecurity Workforce. Infragard J. 2018, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brilingaite, A.; Bukauskasa, L.; Juozapaviciusb, A. A Framework for Competence Development and Assessment in Hybrid Cybersecurity Exercises. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Competency-Based Learning or Personalized Learning. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/oii-news/competency-based-learning-or-personalized-learning (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Pandey, A. A 5-Step Plan to Create a Captivating Scenario-based Corporate Training. ELearning Industry. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/scenario-based-learningcorporate-training-how-create (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Mery, Y.; Blakiston, R. Scenario-Based E-Learning: Putting the Students in the Driver’s Seat. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference in Distance Teaching and Learning, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System, Madison, WI, USA, 3–6 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, K.; Colky, D. Scenario-based e-learning design. Perform. Improv. 2004, 43, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. Accelerating Expertise with Scenario Based Learning. Association for Talent Development. Available online: https://www.td.org/magazines/accelerate-expertise-with-scenario-based-e-learning (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Bloom’s Taxonomy. Available online: https://www.bloomstaxonomy.net/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain. Available online: https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/cyber/cyber-kill-chain.html (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Warnock, J.; Rogers, G. Rubrics Scoring the Level of Student Performance; Institute for the Development of Excellence in Assessment Leadership (IDEAL); ABET, Inc.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).