Abstract

As the energy structure evolves, low-load operation of coal-fired boilers is becoming common, posing challenges to combustion stability. This study explored the co-combustion of brown gas (HHO) with bituminous coal and anthracite in a one-dimensional furnace. Results indicate that introducing HHO significantly elevated combustion temperatures, with maximum increases of 158 °C and 207 °C, respectively. In the premixed mode, the flame front shifted upstream, indicating advanced ignition timing. Moreover, HHO co-combustion notably enhanced the combustion stability of anthracite, as reflected in stabilized furnace temperatures. With increasing HHO flow rate, CO concentrations from both bituminous coal and anthracite were reduced by over 80%. The combustion efficiency of bituminous coal reached 98%, while the combustion efficiency of anthracite increased by 19% (premixed) and 13% (staged), confirming the premixed mode’s superiority in promoting complete combustion. HHO co-combustion increased SO2 emissions but had a complex effect on NOX emissions due to the competition between NOX reduction caused by HHO and NOX formation caused by the increased combustion temperature. HHO co-combustion changed the melting point of fly ash, increased the content of Al2O3, and reduced the content of Na2O, K2O, and MgO, influencing the slagging behavior of the boiler and the subsequent management of fly ash.

1. Introduction

With the adjustment of energy structures and the rapid development of renewable energy, the operating conditions of coal-fired boilers have changed significantly, with low-load operation becoming increasingly frequent [1,2]. In this context, the stability of boiler combustion is facing serious challenges [3]. During low-load operation, the furnace temperature decreases, and the ignition and combustion conditions of pulverized coal airflow deteriorate, which can easily lead to incomplete combustion, reduced combustion efficiency, and increased pollutant emissions [4,5]. Therefore, achieving stable combustion under low-load conditions has become a key issue that urgently needs to be addressed in the operation of coal-fired boilers.

Currently, the industry and academia have developed a variety of combustion stabilization technologies to address this challenge. Burner optimization is a common method. By adjusting the structure and operating parameters of the burner, such as changing the swirl intensity of the primary air or adjusting the angle of the secondary air, the ignition conditions of pulverized coal can be significantly improved [6]. Additionally, increasing the concentration and fineness of pulverized coal is another frequently used approach. This method increases the contact area between pulverized coal and air, thereby enhancing the combustion efficiency [7]. Oxygen-enriched combustion technology, which is based on micro-oil ignition, introduces gas with a higher oxygen content than air into the combustion zone. The increased local O2 concentration within the ignition burner not only raises the local combustion temperature but also further reduces the ignition temperature of pulverized coal. This accelerates the reaction rate, shortens the ignition time, and significantly enhances ignition stability under cold conditions [8]. Auxiliary combustion technologies, such as plasma ignition [9] and micro-oil ignition assistance [10], provide local high-temperature zones or a small amount of fuel to help pulverized coal ignite more quickly. These technologies have alleviated combustion problems during low-load operation to some extent. However, they also have limitations, such as high costs, complex equipment, and poor adaptability to different coal qualities.

The co-combustion of hydrogen, ammonia, and other gaseous fuels has significant potential to address the limitations of existing combustion stabilization technologies. This approach can enhance the ignition and combustion stability of coal under low-load conditions, meet the flexibility requirements for deep peak regulation of power generation units, and is also an effective pathway for coal-fired power plants to reduce carbon emissions from the source. Therefore, research on the mechanisms and technologies of coal co-combustion with hydrogen and ammonia holds substantial theoretical and engineering application value. Research on the co-combustion of coal with ammonia has been widely reported [11,12,13], while studies on the co-combustion of coal with hydrogen are relatively scarce. There is an urgent need to conduct more research on coal co-combustion with hydrogen.

Jia et al. [14] conducted a thermal calculation analysis on a 300 MW subcritical boiler to study the impact of hydrogen co-combustion on boiler performance. Zhao et al. [15] carried out hydrogen-coal co-combustion experiments in a 50 kW down-fired combustion test furnace, investigating the formation patterns of NOX, CO, and CO2. They found that as the hydrogen blending ratio increased, CO2 emissions gradually decreased, while NOX emissions first decreased and then increased, with the lowest NOX emissions observed at a 30% hydrogen blending ratio. Air staging effectively reduced the NOX emissions. Yang et al. [16] conducted experiments on co-combustion bituminous coal with hydrogen in a 50 kW down-fired combustion test furnace, exploring the effects of different hydrogen blending ratios and air staging levels on NO formation, main combustion zone temperature changes, and combustion product emissions. Yasuaki Ueki et al. [17] demonstrated that an optimal hydrogen flow rate can enhance coal combustion efficiency using a drop tube furnace. Lin et al. [18] performed numerical simulations on a swirl coal combustion burner, finding that hydrogen addition increased the burnout rate of the pulverized coal. When the hydrogen added exceeded 3% of the total fuel, the water content in the furnace increased, leading to a lower temperature at the burner outlet and reduced CO production. Dong et al. [19] analyzed the flow field structure, combustion, and component changes in a 660 MW tangential boiler after coal co-combustion with hydrogen through numerical modeling. They found that the rapid combustion of hydrogen generated a large amount of heat in a short time, aiding coal ignition and reduced CO2 emissions at the source. However, the increased hydrogen blending ratio led to higher H2O production, which lowered the overall temperature and affected boiler heat transfer.

Currently, green hydrogen is primarily produced through the electrolysis of water. The separation, purification, storage, and transportation of hydrogen face a series of technical challenges, high costs, and associated safety risks, which limit its widespread application [20,21,22]. Brown gas (HHO), also known as “water fuel”, is a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen produced during the electrolysis process, along with a small amount of water vapor, oxygen radicals, hydroxyl radicals, and other reactive substances [23]. HHO gas can be produced on demand and used immediately, overcoming the issues associated with hydrogen use. Additionally, since HHO gas contains its own oxygen, at specific blending ratios, it may reduce or even eliminate the need to increase the primary air volume, thereby minimizing the impact on the boiler’s existing air distribution system.

Hu et al. [24] performed co-combustion experiments of coal with HHO gas in a tubular furnace, showing that HHO gas injection improved the burnout rate of pulverized coal and significantly reduced the fixed carbon content in fly ash. Liu et al. [25] conducted numerical simulations in a 1000 MW supercritical tangential coal-fired boiler. They blended different proportions of hydrogen and oxygen in the primary air to enhance flame temperature and improve combustion stability at low loads. Zhang et al. [26,27,28] used a 200 kW down-fired combustion test furnace to study the effects of HHO gas injection methods and air staging on flue gas emissions characteristics, combustion intensity, and fly ash properties during coal co-combustion at low and ultra-low loads. Their results showed that co-combustion with HHO gas enhanced the combustion stability of pulverized coal at ultra-low loads.

HHO gas, as a zero-carbon fuel, still requires in-depth research regarding its co-combustion characteristics with coal. Existing studies have made preliminary explorations into the co-combustion mechanisms of HHO gas with lignite and bituminous coal, but there is still insufficient research on its application with anthracite. Therefore, this paper aims to systematically investigate the adaptability and differences of co-combustion of HHO gas with bituminous coal and anthracite. Co-combustion experiments were conducted using a 100 kW combustion one-dimensional furnace. Optical windows were installed on the furnace walls, and industrial cameras were innovatively utilized to observe ignition positions, thereby accurately monitoring the combustion process. Two gas injection modes, premixed mode and staged mode, were employed to analyze the effects of different flow rates of HHO gas on combustion intensity, flue gas emissions characteristics, and fly ash properties.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Experimental Equipment

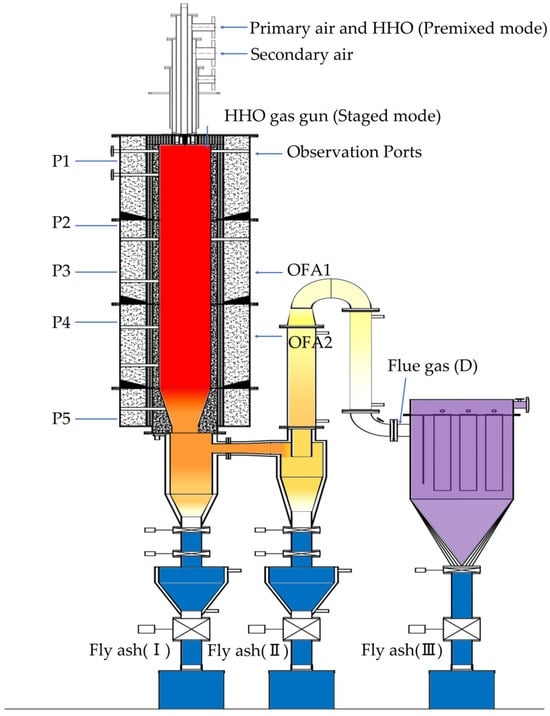

The experiments were conducted in a 100 kW one-dimensional furnace, as shown in Figure 1. The one-dimensional combustion system mainly consists of a furnace chamber, coal feeder, swirl burner, induced draft fan, forced draft fan, air preheater, cyclone separator, baghouse dust collector, baghouse bypass, and flue gas cooler. The total height of the furnace chamber is 3200 mm, with an inner diameter of 400 mm. The furnace insulation layer is composed of a corundum-mullite castable, zirconium-containing cylinder, alumina-silica insulation cotton, and stainless steel shell, ensuring the thermal insulation performance of the furnace. An observation port is located 250 mm away from the top of the furnace. An industrial camera (Hikrobot MV-CS004-10UC, Hangzhou, China) is used to capture the flame shape, with the gate width (i.e., single exposure time) of 400 μs. Type B and Type S thermocouples are installed at locations P1/P2 and P3/P4/P5, respectively, 0.5 m, 1.3 m, 1.9 m, 2.5 m, and 3.6 m from the top of the furnace, to monitor temperature changes at different positions within the furnace. The swirl burner is installed at the top of the furnace chamber. Primary air and secondary air enter the furnace chamber through the burner, and over fire air (OFA) consists of two layers, entering the furnace chamber through air inlets on the side wall. Natural gas was used for ignition in the experiments. When the temperature at the bottom of the furnace exceeds 600 °C, the feeder begins to operate and delivers pulverized coal to the combustion chamber through the main air pipe.

Figure 1.

The 100 kW one-dimensional furnace combustion system.

An HHO gas generator produces HHO gas by electrolyzing water. The generator used in this study was provided by Zhejiang Heli Hydrogen Energy Technology Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China), with the model number T20X. The entire generator weighs approximately 1000 kg, with dimensions of 1620 × 1150 × 1620 mm. The maximum gas production rate is 25 m3/h. The HHO gas generator employs an aqueous sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution as the electrolyte. Through the electrochemical reaction of water electrolysis, it decomposes water into hydrogen and oxygen; the hydrogen serves as fuel and the oxygen supports combustion. Automatic water injection allows for continuous operation without manual refilling. According to the preset back-pressure demand and gas consumption, the control system receives pressure feedback and automatically adjusts the electrolysis current to match, with the gas production rate displayed in real-time. Before operating the generator, the pressure of the internal gas storage tank must be set according to the gas demand. The HHO gas flow rate is controlled by adjusting the generator pressure and the valve opening at the outlet. The flow rate values are obtained from the generator display. Multi-stage flame arrestors are installed inside the generator and on the gas pipelines to prevent gas flashback during combustion, ensuring safety.

2.2. Fuel Properties

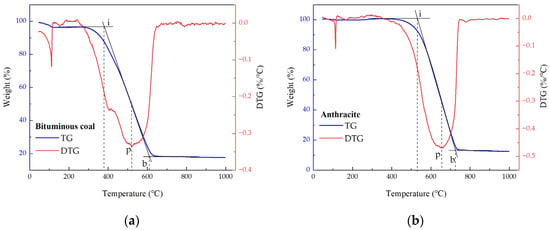

The fuels selected for the experiments were two typical types of coal used in power generation: bituminous coal and anthracite. All coal samples were ground to a particle size of less than 200 μm, stored at room temperature. The fuel characteristics are shown in Table 1. Thermogravimetric tests were performed on a simultaneous thermal analyzer (Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC3+, Zurich, Switzerland). The instrument is equipped with an ultra-micro balance with a sensitivity of 0.1 µg and a temperature accuracy of ±0.05 °C at any single point. During the experiment, the sample was placed in a small crucible and heated from 50 °C to 1000 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under an air atmosphere. Thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) analyses were performed on the two types of pulverized coal. Based on the TG–DTG curves recorded during the combustion characteristics tests of the coal samples in the thermogravimetric analyzer, the ignition temperature (Ti), burnout temperature (Tb), and the temperature corresponding to the maximum weight loss rate (Tp) were determined, as shown in Figure 2. The characteristics of these two types of coal are significantly different. Anthracite is characterized by a high fixed carbon content and low volatile matter content. Bituminous coal has high volatility, low fixed carbon, and high moisture content. As a result, anthracite has a higher heat value than bituminous coal and exhibits poorer combustion characteristics.

Table 1.

Fuel properties.

Figure 2.

TG/DTG curve of bituminous coal/anthracite used in this study. (a) Bituminous coal; (b) Anthracite. (i: ignition, p: peak, b: burnout).

2.3. Experimental Conditions

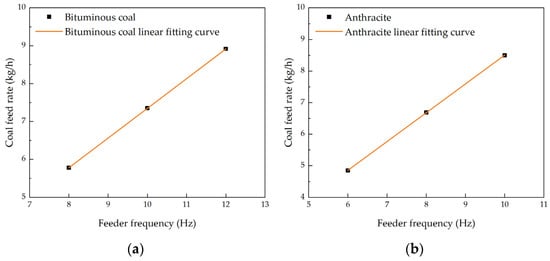

With these fuel characteristics in mind, the experimental conditions were carefully controlled to ensure accurate results. The coal feeder, which serves as the heat input source for the furnace, controls the heat load by adjusting its frequency. The coal feeder was calibrated to ensure accurate adjustments, with the results shown in Figure 3. The coal feed rate increases with the increase in the coal feeder frequency, and a strong linear relationship was observed between these two quantities.

Figure 3.

Output characteristics of coal feeder. (a) Bituminous coal; (b) Anthracite.

The experimental conditions are detailed in Table 2. The excess air ratio for the two types of coal combustion was 1.2. Throughout the experiments, the excess air ratio was maintained at a constant value, and the air distribution was kept stable. HHO gas was injected into the combustion system in two distinct modes to investigate its effects on co-combustion performance, as illustrated in Figure 1. Co-combustion experiments were conducted with varying HHO gas flow rates for each mode. In the premixed mode, HHO gas was fed into the main pipeline. The outlet end of the gas supply was connected to the primary air pipe, and a valve was installed at the outlet to control the gas flow rate. In the staged mode, HHO gas was injected through a spray gun. The spray gun was positioned 150 mm away from the center of the burner. The spray gun had a total length of 3220 mm, an outer diameter of 3 mm, and a front outlet orifice diameter of 1 mm.

Table 2.

Operating conditions of the co-combustion experiments.

2.4. Analytical and Measurement Methods

The proximate analysis of the coal sample was performed according to GB/T 212-2008 [29] using a fully automatic 5E-MAG6700 unit (Changsha Kaiyuan, Changsha, China). The ultimate analysis was carried out following GB/T 476-2001 [30] on a vario MAX cube analyzer (Elementar, Frankfurt, Germany).

Flue gas composition (O2, CO, CO2, NOX, SO2, H2O) was continuously measured at the baghouse dust collector inlet (Point D, Figure 1) using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analyzer (Gasmet DX4000, Vantaa, Finland). The analyzer, zero-calibrated with high-purity nitrogen before each test, operates in a spectral range of 900–4200 cm−1 with a configurable sampling interval (1 s to 5 min). Its detection limit for most species is <1 ppm, with an expanded uncertainty of 3% of the full-scale range.

Fly ash was sampled from three locations: the furnace chamber hopper (I), cyclone separator (II), and baghouse dust collector (III). The collected ash was analyzed for unburned carbon content and ash melting point. Furthermore, its mineralogical phase composition, chemical components, and morphology were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD; Rigaku SmartLab SE, Tokyo, Japan), X-ray fluorescence (XRF; Thermo Scientific ARL Perform’x, Guangzhou, China), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SU-70, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). XRD provided high-resolution, non-destructive phase analysis. SEM allowed for imaging at magnifications from 20× to 800,000× and qualitative to quantitative elemental analysis.

Potential uncertainties from instrumental, operational, and human factors were considered. The overall experimental uncertainty was estimated following the Kline–McClintock method to ensure measurement reliability [31].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Co-Combustion on Ignition Position and Furnace Temperature

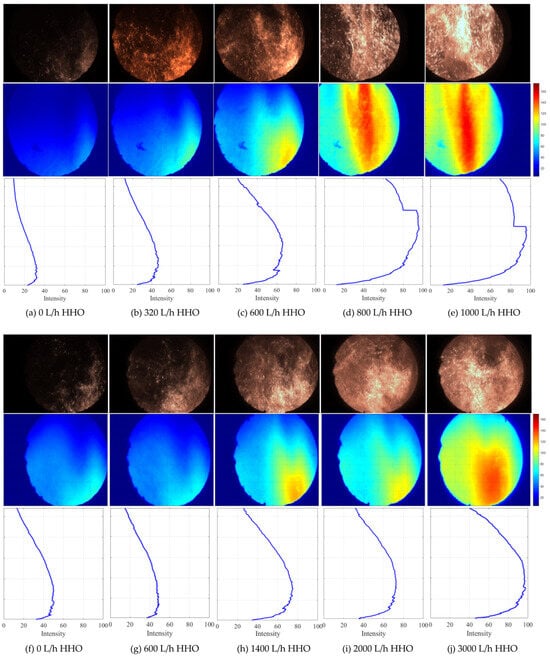

Figure 4 illustrates the flame images in the furnace, the pixel-wise mean image reconstructed from a 60 s video sequence and the associated vertical profiles of row-averaged pixel intensity during the co-combustion of HHO gas with bituminous coal in premixed (a–e) and staged (f–j) modes. In the premixed mode, a progressive increase in HHO gas flow rate shifts the entire flame front upstream, causing the peak of the mean-intensity profile to move closer to the nozzle. This signifies a marked reduction in ignition delay. At an HHO gas flow rate of 800 L/h, the ignition position moves above the observation window. In the staged mode, variations in HHO gas flow rate exerts a negligible influence on the flame-root position; the flame remained anchors slightly below the observation window. Although the peak position remains nearly unchanged, the overall heat-release rate increases monotonically with HHO gas flow. Overall, at any given HHO gas flow rate, the premixed configuration delivers a stronger enhancement; for example, the benefit obtained at 600 L/h in the premixed mode is equivalent to that at 1400 L/h in the staged mode.

Figure 4.

Changes in ignition position during the co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal. (a–e) Premixed mode, and (f–j) staged mode.

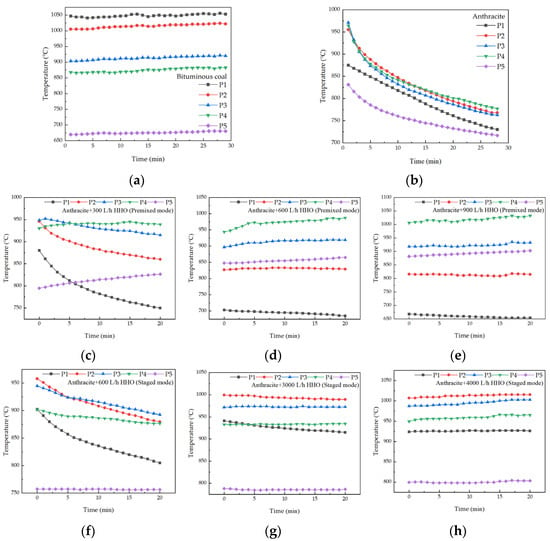

Figure 5 depicts the transient furnace temperature within the furnace during pulverized-coal combustion. When bituminous coal is burned, the temperature remains nearly constant, increasing slightly due to the thermal inertia of the one-dimensional adiabatic furnace. In contrast, firing anthracite leads to a monotonic temperature decrease, which is attributed to its poor ignition and prolonged burnout characteristics. At P1, the temperature decreases significantly because the anthracite does not ignite immediately and absorbs heat from the area. The temperatures at P2, P3, and P4 are higher than at P1 and P5, indicating that the main combustion zone is predominantly in this section, which represents a noticeable downward shift in the combustion region compared to that of bituminous coal. In the premixed mode, anthracite exhibits stable combustion when the HHO gas flow rate reaches or exceeds 600 L/h. In the staged mode, stable combustion of anthracite is achieved when the HHO gas flow rate is equal to or greater than 3000 L/h.

Figure 5.

The temporal evolution of furnace temperature during pulverized-coal combustion. (a) Bituminous coal, (b) anthracite, (c–e) anthracite co-fired with HHO in premixed mode, and (f–h) anthracite co-fired with HHO in staged mode.

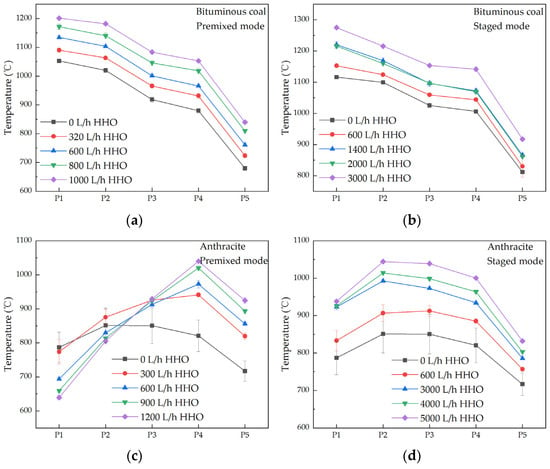

Figure 6 presents the axial temperature profiles under various operating conditions. Co-combustion of HHO gas with bituminous pulverized coal elevates temperatures along the entire furnace axis without displacing the primary reaction zone, which remains centered at P1. Anthracite, due to its elevated fixed-carbon and reduced volatile-matter contents, exhibits markedly longer ignition delay [32]; only sporadic sparks are observed through the observation window, and the ignition front is situated beneath it. In the premixed mode, HHO gas is premixed with the primary air. Due to the lower furnace temperature, anthracite coal releases fewer volatiles, resulting in lower combustion intensity, and the transported-in anthracite coal also carries away some heat, hence causing the temperature at P1 to gradually decrease. As the mixture travels downstream, HHO gas reaches the rear zone (P4), where the temperature is relatively high due to the combustion of anthracite. HHO gas combusts vigorously at that location. Raising the HHO gas flow rate increases the temperature at P4 because the gas burns in the rear section, supplying additional heat and rendering P4 the hottest location. This in turn accelerates the burnout of anthracite and enhances overall combustion efficiency. In the staged mode, HHO gas is injected adjacent to the burner and ignited by an electric spark. The gas burns immediately at the furnace top, supplying supplementary heat that halts the temperature drop at P1 and subsequently elevates it. As the HHO gas flow increases, P2 and P3 evolve into high-temperature zones because additional heat released at the burner accelerates anthracite ignition, shifting the high-temperature region upstream. Consequently, the axial temperature distribution becomes more uniform and combustion efficiency improves. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that optimizing the HHO gas injection strategy can simultaneously improve the combustion process and enhance the combustion efficiency.

Figure 6.

Furnace temperature profiles for various operating conditions. (a) Bituminous coal and HHO, premixed mode; (b) Bituminous coal and HHO, staged mode; (c) Anthracite and HHO, premixed mode; (d) Anthracite and HHO, staged mode.

As the HHO gas flow rate increases, the combustion temperature in the main combustion zone rises. Radiative heat transfer is dominant in the high-temperature zone of the furnace. The primary components of HHO gas, hydrogen, and oxygen release heat upon combustion and produce a substantial amount of water vapor. Water molecules, as polyatomic molecules, possess strong radiative capabilities. In the premixed mode, when co-combusted with bituminous coal, the main combustion zone temperature increases from 1052 °C to 1201 °C as the HHO gas flow rate increases to 1000 L/h, a temperature rise of 149 °C. The thermal power input increases by 1.84 kW, corresponding to a 4.91% increase, while the temperature rises by 14.16%. When co-combusted with anthracite, the main combustion zone temperature increases by 26.74% as the HHO gas flow rate increases to 1200 L/h, while the thermal power input rises by 5.35%. The temperature rise is more pronounced than the increase in thermal power input. In the staged mode, when co-combusted with bituminous coal, the main combustion zone temperature increases by 14.21% as the HHO gas flow rate rises to 3000 L/h, while the thermal power input increases by 14.72%. When co-combusted with anthracite, the main combustion zone temperature increases by 22.16% as the HHO gas flow rate reaches to 5000 L/h, while the thermal power input increases by 22.34%. In this case, the temperature increase is less significant than the thermal power input.

In the premixed mode, HHO gas is thoroughly mixed with pulverized coal and air. At the same HHO gas flow rate, the ignition position is significantly advanced, and the combustion process becomes more uniform, with heat distributed widely. This significantly improves the combustion efficiency, resulting in a more pronounced temperature increase compared to the input of thermal power. In contrast, in the staged mode, HHO gas is introduced into the furnace 15 cm from the center at the top of the furnace and gradually mixes with pulverized coal and air. The combustion of HHO gas is primarily concentrated in a local area, making the combustion process more focused. As a result, the overall temperature increase is relatively limited, with the temperature rise being less than the input of thermal power.

3.2. Effect of Co-Combustion on Emission Characteristics

To eliminate the dilution effect of flue gas, the concentrations of CO2/CO/NOX/SO2 are normalized to a 6% O2 volume fraction, as shown below:

where is the normalized value, is the measured concentration, and is the measured O2 volume fraction.

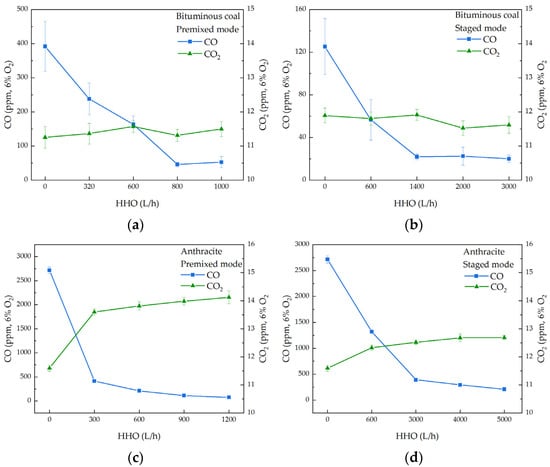

3.2.1. CO2 and CO Emissions

Figure 7 illustrates the impact of different HHO gas injection methods on CO2 and CO emissions during co-combustion with the two types of coal. When co-combusted with bituminous coal, the CO concentration decreases with increasing HHO gas flow rate, while the CO2 concentration remains relatively unchanged. In contrast, anthracite, with its extremely low volatile matter content, generates limited heat during the initial combustion phase, which hinders the rapid attainment of the high temperatures necessary for complete combustion. Consequently, incomplete combustion occurs, leading to higher CO emissions. However, when anthracite is co-combusted with HHO gas, the CO concentration is markedly reduced, and the CO2 concentration experiences a slight increase. These observations suggest that the introduction of HHO gas accelerates the oxidation of CO, thereby reducing its concentration and enhancing the combustion efficiency of pulverized coal. HHO gas, produced by water electrolysis, contains a large amount of oxygen, as well as reactive species such as OH radicals, O atoms, and other active substances that significantly affect combustion [33]. These components further enhance the oxidizing atmosphere in the furnace under the original excess oxygen conditions, promoting the combustion of pulverized coal.

Figure 7.

The CO2 and CO emissions during co-combustion of bituminous coal/anthracite with HHO. (a) Bituminous coal and HHO, premixed mode; (b) Bituminous coal and HHO, staged mode; (c) Anthracite and HHO, premixed mode; (d) Anthracite and HHO, staged mode.

In the premixed mode of co-combustion with bituminous coal, the CO concentration drops sharply from an initial 391.7 ppm to 45.6 ppm at an HHO gas flow rate of 800 L/h, representing a substantial reduction of 88.36%. In the staged mode, the CO concentration decreases from 125.2 ppm to 21.8 ppm at an HHO gas flow rate of 1400 L/h, a reduction of 82.59%. Further increases in the HHO gas flow rate beyond these levels result in only minimal changes in CO concentration. When co-combusted with anthracite, the CO concentration decreases by 84.74% in the premixed mode at an HHO gas flow rate of 300 L/h. In the staged mode, the CO concentration decreases by 85.56% at an HHO flow rate of 3000 L/h. The premixed mode requires a lower HHO gas flow rate to achieve significant CO reduction, indicating that it is more effective in promoting the complete combustion of char. During the pulverized coal combustion process, a large amount of oxygen is consumed, creating an oxygen-deficient or even oxygen-free zone downstream of the center of the one-dimensional furnace burner [34]. In the staged mode, the outlet of the HHO gas injector is situated in this low-oxygen region. The direct injection of HHO gas into this area affects the combustion process by transforming it into a reducing atmosphere. In contrast, in the premixed mode, HHO gas is thoroughly mixed with primary air and pulverized coal before being introduced into the burner. This enhanced contact between the components weakens the reducing atmosphere effect, leading to more efficient combustion.

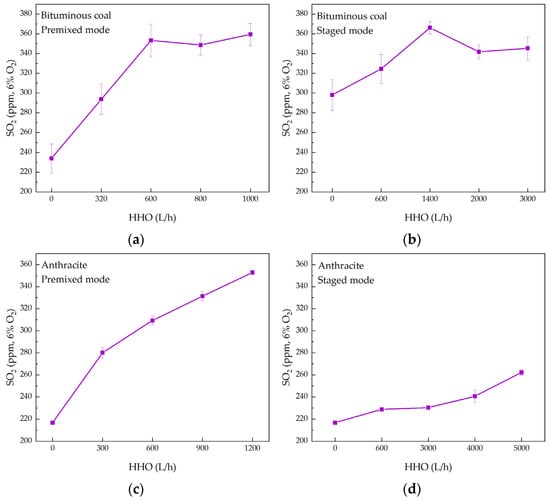

3.2.2. SO2 and NOX Emissions

Figure 8a–d illustrates the SO2 emissions under various operating conditions. As the HHO gas flow rate increases, the SO2 emissions from bituminous coal combustion generally exhibit an increasing trend, with slight fluctuations. In the premixed mode, the SO2 concentration rises from 234 ppm under pure coal conditions to 353 ppm at an HHO gas flow rate of 600 L/h, representing an increase of 50.85%. In the staged mode, the SO2 concentration increases from an initial 298 ppm to 366 ppm at an HHO gas flow rate of 1400 L/h, corresponding to a 22.82% increase. For anthracite combustion, the SO2 emissions also rise with the HHO gas flow rate. In the premixed mode, the SO2 concentration increases by 62.76% when the HHO gas flow rate reaches 1200 L/h. In the staged mode, the SO2 concentration rises by 21.00% when the HHO gas flow rate reaches 5000 L/h. The observed increase in SO2 emissions is primarily driven by the elevated combustion temperature resulting from HHO co-combustion. The higher flame temperature intensifies the devolatilization process, thereby promoting the release and subsequent oxidation of fuel-sulfur [35,36]. Although HHO gas introduces a small amount of oxygen, its contribution is negligible compared to the well-controlled excess air supply (α = 1.2). Therefore, the thermal effect is the dominant factor enhancing SO2 formation. Notably, the SO2 emission increment in the staged mode was lower than that in the premixed mode. This can be attributed to the strong, localized reducing atmosphere created in the staged configuration, which promotes the reduction of SO2 to other sulfur species such as H2S [28]. Nevertheless, the overall SO2 emissions still increased relative to pure coal combustion, indicating that the temperature-driven promotion of sulfur release and oxidation remains the dominant factor.

Figure 8.

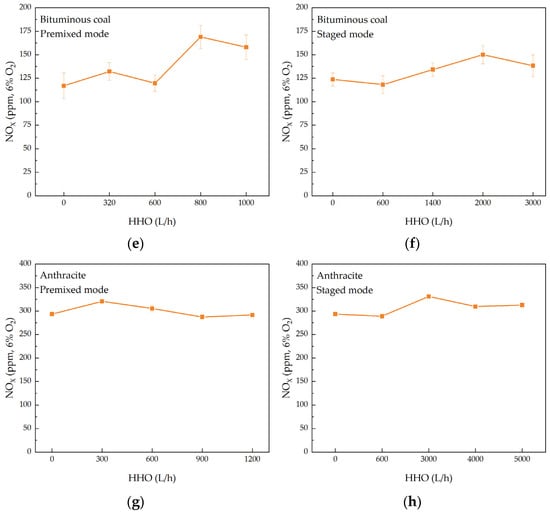

SO2 and NOX emissions during co-combustion of bituminous coal/anthracite with HHO. (a–d) SO2 emissions; (e–h) NOX emissions.

Figure 8e–h illustrates the NOX emissions under various operating conditions. The impact of HHO gas on NOX emissions can be understood through two primary mechanisms. First, the O in HHO gas and the ionized OH radicals significantly enhance the oxidative atmosphere in the main combustion zone. This enhancement promotes the release of volatile nitrogen compounds and the subsequent formation of NOX. Additionally, the combustion of gaseous fuels like H2 is a homogeneous reaction, with a reaction rate much faster than the heterogeneous combustion reaction of pulverized coal. This faster reaction rate increases the propagation speed of the original flame, enhancing the preheating effect of the flame front on coal particles and accelerating the heating and devolatilization ignition combustion process of the particles [37,38]. Conversely, HHO gas also contains strong reducing components, such as H2 and H radicals, which can directly reduce the formed NOX through specific reactions (2) and (3) [39]. Moreover, CO can promote the NO–char interaction, primarily through reaction (4), which is catalyzed by char [40,41].

When bituminous coal is burned in the premixed mode, NOX emissions are higher compared to pure coal combustion. This increase is primarily due to the elevated combustion temperature resulting from co-combustion, which outweighs the reduction effect of HHO gas on NOX formation. In the staged mode, the increase in NOX emissions is lower than in premixed mode. This is attributed to the localized combustion of HHO gas, which results in a limited overall temperature increase and restricts the formation of thermal NOX. Additionally, the staged mode, by concentrating HHO gas injection, may create stronger localized reducing conditions that more effectively mitigate the overall thermal NOX formation. For anthracite combustion, the introduction of HHO gas has little impact on NOX emissions in both premixed and staged modes.

3.3. Effect of Co-Combustion on Fly Ash Characteristics in Furnace

The melting point of ash is a critical factor influencing the tendency and degree of slagging in boilers. Low-melting-point substances within ash melt in the high-temperature environment of the boiler, leading to slag formation [42,43]. Taking bituminous coal as an example, Table 3 presents the four characteristic temperatures of fly ash during the co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal: deformation temperature (DT), softening temperature (ST), hemispherical temperature (HT), and flow temperature (FT). In the premixed mode, DT initially increases and then decreases with increasing HHO gas flow rate. For example, it rises from 1316 °C at 0 L/h HHO gas to 1443 °C at 600 L/h HHO gas, drops to 1404 °C at 800 L/h HHO gas, and increases again to 1479 °C at 1000 L/h HHO gas. This trend indicates that the addition of HHO gas influences the initial deformation temperature of fly ash. Higher DT values suggest greater resistance to deformation at elevated temperatures. Meanwhile, ST, HT, and FT are generally above 1500 °C, demonstrating that fly ash exhibits high thermal resistance during co-combustion and is less likely to soften, form a hemispherical shape, or flow at lower temperatures. In the staged mode, DT exhibits slight fluctuations, likely due to localized high-temperature zones that affect the thermal stability of fly ash at different HHO gas flow rates. Similar to the premixed mode, the ST, HT, and FT in the staged mode were also mostly above 1500 °C, further confirming the high thermal resistance of fly ash under these conditions.

Table 3.

Characteristic temperatures of fly ash during co-combustion of bituminous coal and HHO gas.

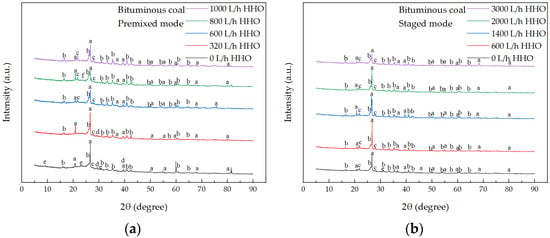

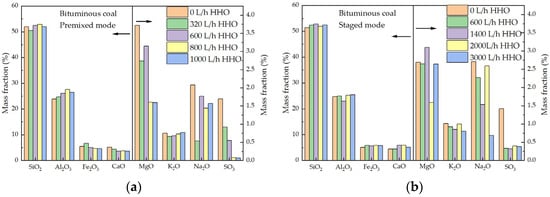

XRD analysis, as shown in Figure 9, indicates that the main components of ash are quartz, mullite, and albite, with some samples containing calcite, anorthite, and orthoclase. Co-combustion with HHO gas does not significantly alter the main chemical composition of fly ash compared to pure coal combustion. As shown in Figure 10, XRF results indicate that the main oxides in ash are SiO2 and Al2O3, accounting for over 75% of the total mass. As the HHO gas flow rate increases, the content of Al2O3 rises, suggesting an increase in the number of completely combusted aluminosilicate particles [44] and a corresponding decrease in unburned carbon content. Additionally, the SO3 content in fly ash during HHO gas co-combustion decreases compared to pure coal combustion. This reduction is likely due to the high-temperature reducing atmosphere, which promotes the decomposition of sulfate minerals [45] and increases SO2 emissions, as illustrated in Figure 8a,b. Bituminous coal ash has a high level of sodium, accounting for 6.06 wt.% of the ash. However, the concentration of sodium oxides in fly ash is much lower than that in coal ash. This is probably because sodium species in coal are usually mobile and enter the gas phase in the form of NaCl during combustion [45]. NaCl vapor mainly forms submicron particles through homogeneous condensation in the flue gas stream or undergoes heterogeneous condensation on fly ash particles containing Si-Ca. Subsequently, the condensed NaCl reacts with silicon to form sodium silicate [46]. Therefore, many sodium species eventually deposit on fly ash particles, which is consistent with the XRD results. Compared with pure coal combustion, the total content of Na2O, K2O, and MgO in fly ash decreases under HHO gas co-combustion. This reduction is attributed to the high-temperature reducing atmosphere created by HHO gas, which promotes the reduction of these metallic oxides to more volatile elemental or sub-oxide species (e.g., Na, K). These volatile species vaporize from the fly ash particles and are likely transported downstream in the flue gas, condensing on cooler heat exchange surfaces beyond the fly ash sampling point [47,48]. Consequently, the depletion of these key fluxing agents in the collected fly ash reduces the tendency to form low-melting-point eutectic compounds [49,50], thereby increasing the ash fusion temperature, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 9.

XRD analysis of fly ash from co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal. (a) Premixed mode, and (b) staged mode. a: SiO2 (Quartz); b: Al6Si2O13 (Mullite); c: Na(AlSi3O8) (Albite); d: CaCO3 (Calcite); e: K(NaMg2) (Si4O10F2) (Anorthite); f: K(AlSi3O8) (Orthoclase).

Figure 10.

The oxide composition of fly ash from co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal. (a) Premixed mode and (b) staged mode.

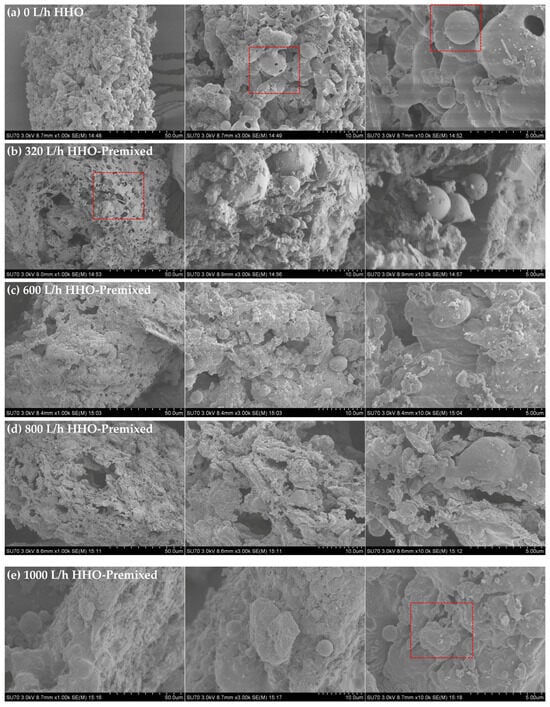

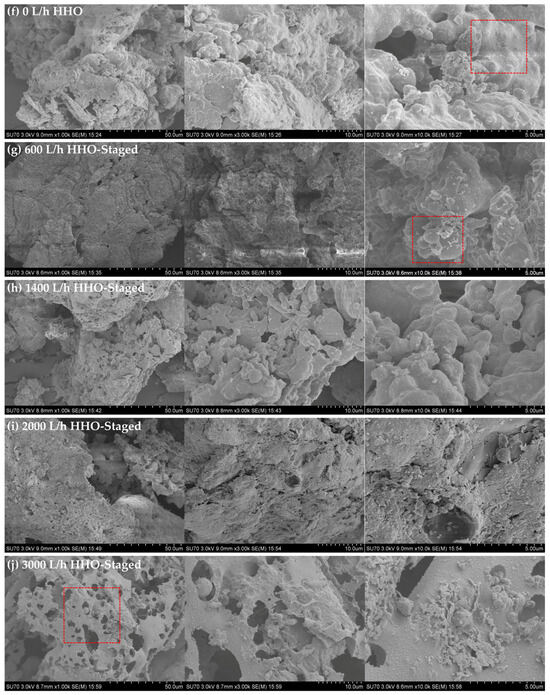

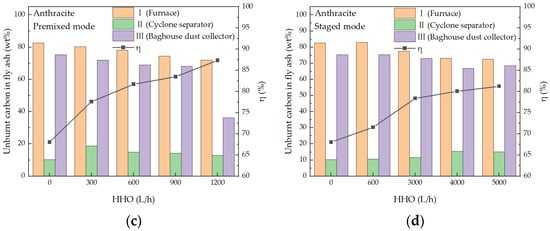

SEM observations of fly ash during co-combustion of bituminous coal and HHO gas, as shown in Figure 11, revealed the micromorphology of the samples. During pure coal combustion, coal particles break into smaller particles with hollow interiors and a large number of spherical coal ashes appear, exhibiting melting phenomena. The main component of these spherical coal ashes is silicoaluminates, and their surfaces are often enriched with substances containing K, Ca, Fe, Mg, etc. [51], formed by the rapid cooling of molten coal ash at high temperatures. When bituminous coal is co-combusted with HHO gas, the carbon structure on the coal surface is significantly consumed, forming a collapsed, honeycomb-like, uneven porous structure [52]. In premixed mode, fly ash particles may melt to some extent at high temperatures, forming larger particle clusters. In staged mode, the morphology of fly ash particles may vary due to changes in combustion temperature, with some particles remaining small in size and others melting and clustering due to local high temperatures. As the HHO gas flow rate increases, the combustion temperature rises, and the morphology of the fly ash particles changes significantly. At high flow rates, fly ash particles may melt and form larger particle clusters due to high temperatures, while at low flow rates, they may remain small in size.

Figure 11.

SEM images of fly ash from co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal. (a–e) Premixed mode and (f–j) staged mode (scale bars: 50 μm, 10 μm, 5 μm).

The influence of co-combustion of HHO gas and bituminous coal on fly ash characteristics is multifaceted. The addition of HHO gas raises the combustion temperature, causing more complex chemical reactions in the mineral components of fly ash. Meanwhile, the high-temperature environment causes fly ash particles to melt and cluster, forming larger particle clusters. These changes vary depending on the combustion mode and HHO gas flow rate, and they have significant implications for the subsequent treatment of fly ash and its environmental impact. For example, silicate minerals in fly ash may have certain effects on soil and water [53], while larger particle clusters may affect the emission of atmospheric particulate matter.

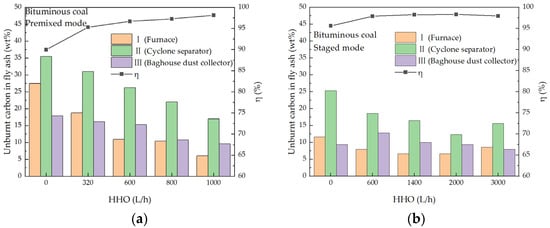

3.4. Effect of Co-Combustion on Combustion Efficiency

The results of unburned carbon in fly ash and pulverized coal combustion efficiency (η), shown in Figure 12, were used to analyze the impact of HHO gas co-combustion on pulverized coal burnout. Combustion efficiency is calculated using the following formula:

where Qr is the input heat, kJ/kg; ax is the mass fraction of ash discharge at that location relative to the total ash quantity, %; Cx is the unburned carbon content in the fly ash, %; and RO2 is the volume percentages of triatomic gases (CO2 and SO2), %.

Figure 12.

The unburnt carbon in the fly ash and pulverized coal combustion efficiency. (a) Bituminous coal and HHO, premixed mode; (b) Bituminous coal and HHO, staged mode; (c) Anthracite and HHO, premixed mode; (d) Anthracite and HHO, staged mode.

Combustion efficiency exhibited a consistent upward trend with increasing HHO gas flow rate for both bituminous coal and anthracite under the two HHO injection modes. For bituminous coal co-combustion systems, the premixed mode achieved the maximum combustion efficiency of 98.15% at an HHO flow rate of 1000 L/h, corresponding to an increment of 8.18 percentage points (pp) relative to the baseline efficiency (89.97%) without HHO addition. In contrast, the staged mode reached a peak efficiency of 98.32% at a higher HHO flow rate of 2000 L/h.

Anthracite, as a high-rank coal characterized by high fixed carbon content and low volatile matter, inherently suffers from poor ignition performance and sluggish combustion kinetics, resulting in a substantially lower baseline combustion efficiency of 68.04%. HHO co-combustion effectively mitigated these drawbacks and significantly improved anthracite combustion efficiency. Specifically, the premixed mode elevated the efficiency to 87.34% at an HHO flow rate of 1200 L/h, yielding a remarkable increment of 19.30 pp; in staged mode, the efficiency increased to 81.25% at an HHO flow rate of 5000 L/h, with an increment of 13.21 pp. This divergence clearly demonstrates that the premixed mode exerts a more potent promoting effect on anthracite combustion efficiency than the staged mode.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted co-combustion experiments of HHO gas with bituminous coal and anthracite in a 100 kW down-fired one-dimensional combustion system. The effects of HHO gas injection methods and co-combustion flow rates on combustion intensity, flue gas emissions, and fly ash properties were investigated. The results include:

- HHO co-combustion improved combustion intensity and stability. The premixed mode advanced the ignition timing of bituminous coal, evidenced by an upstream shift of the flame front. For anthracite, stable combustion was achieved at HHO flow rates ≥ 600 L/h in the premixed mode, whereas the staged mode required ≥ 3000 L/h, effectively addressing the issue of unstable furnace temperatures that occurred when anthracite was burned alone.

- HHO co-combustion significantly increased the temperature in the main combustion zone. In the premixed mode, the maximum temperature rise for bituminous coal was 149 °C, while for anthracite, it reached 207 °C. In the staged mode, the maximum temperature rises for bituminous coal and anthracite were 158 °C and 191 °C, respectively. As the HHO flow rate increased, the CO emission concentrations from both bituminous coal and anthracite combustion were reduced by over 80%, indicating a substantial improvement in combustion completeness. HHO co-combustion significantly enhanced combustion efficiency: the efficiency of bituminous coal reached 98%, while that of anthracite increased by 19% in the premixed mode and 13% in the staged mode, confirming the superiority of the premixed mode in promoting the complete combustion of pulverized coal.

- HHO co-combustion promotes the release and oxidation of sulfur in coal, leading to increased SO2 emissions. The impact on NOX emissions is complex. This is primarily due to the competition between the reduction of NOX caused by HHO gas and the increased formation of NOX due to the higher combustion temperatures. Optimization is required based on specific combustion conditions.

- HHO co-combustion increases the melting point of fly ash and alters its chemical composition and micro-morphology. Compared with pure coal combustion, co-combustion with HHO gas increases the content of Al2O3 in fly ash while reducing the contents of Na2O, K2O, and MgO. These changes collectively reduce the risk of boiler slagging.

Author Contributions

K.H.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; Y.C.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Resources; Y.H.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation; S.L. (Shiyan Liu): Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology; C.X.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation; S.L. (Siyu Liu): Investigation, Supervision, Validation; W.W.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation; Y.Z.: Resources, Supervision, Validation; Z.W.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24B2068, 52125605, Zhihua Wang), R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (2025C04018, Zhihua Wang), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR23E060001, Yong He), and the Baima Lake Laboratory Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LBMHZ24E060001, Wubin Weng).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yunlong Cai is employed by the Zhejiang Heli Hydrogen Energy Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Richter, M.; Oeljeklaus, G.; Görner, K. Improving the load flexibility of coal-fired power plants by the integration of a thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. Overall review of peak shaving for coal-fired power units in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Huang, C.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Z.; Song, J.; Fang, F.; Su, J.; et al. Industrial measurement of combustion and NOx formation characteristics on a low-grade coal-fired 600MWe FW down-fired boiler retrofitted with novel low-load stable combustion technology. Fuel 2022, 321, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, J. Energy consumption characteristics and energy saving potential of thermal power plants under ultra-low power load ratio conditions. Energy 2025, 330, 136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, H.; Yang, Z.; Deng, S.; Wu, X.; An, J.; Sheng, R.; Ti, S. CFD modeling of flow, combustion and NOx emission in a wall-fired boiler at different low-load operating conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z. Achievement in ultra-low-load combustion stability for an anthracite- and down-fired boiler after applying novel swirl burners: From laboratory experiments to industrial applications. Energy 2020, 192, 116623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Moon, C.; Eom, S.; Choi, G.; Kim, D. Coal-particle size effects on NO reduction and burnout characteristics with air-staged combustion in a pulverized coal-fired furnace. Fuel 2016, 182, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Guo, X.; Hou, D.; Yao, W.; Yan, G.; Xin, Z.; Xiaoming, Z. Application of pure oxygen ignition technology in a 670 MW unit boiler firing inferior coal. Therm. Power Gener. 2013, 42, 103–106+128. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/61.1111.TM.20131224.1700.021 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Ibrahimoglu, B.; Yilmazoglu, M.Z.; Cucen, A. Numerical modeling of repowering of a thermal power plant boiler using plasma combustion systems. Energy 2016, 103, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z. Influence of coal-feed rates on bituminous coal ignition in a full-scale tiny-oil ignition burner. Fuel 2010, 89, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on co-firing characteristics of ammonia with pulverized coal in a staged combustion drop tube furnace. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 3217–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Si, T.; Lv, Z.; Li, S. Comprehensive effect of the coal rank and particle size on ammonia/coal stream ignition. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H. Experimental study on the effects of ammonia cofiring ratio and injection mode on the NOx emission characteristics of ammonia-coal cofiring. Fuel 2024, 363, 130996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Yin, Y. Study on Co-combustion Hydrogen in a 300 MW Coal-fired Boiler. Power Syst. Eng. 2016, 32, 37–38. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Ow72tX7v2w20D5qJMxlWm2HgVU6MS8ta2TPjQQX9mNg6_Zsl36ytDS93IA6n5udM1wTPmGe1KIfFgIe8d579bbZST0imax9qsMN6PQ4ghlniGPAdCTDvzqapMDPRIvoSzf5z6FjTb8QnPNGp4xv7fZEhU86B-5WX6nG0ChVdYwNcimD3UTBmA42-iVZ5ktJ1&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, G.; Lin, S.; Fan, W. Experimental study on the influence of coal/hydrogen co-firing on combustion characteristics. Clean Coal Technol. 2024, 1–7. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3676.TD.20240730.0944.002 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wei, G.; Fan, W. Study on combustion technology of pulverized coal mixed with hydrogen. Ind. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 51, 104–108. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/42.1640.X.20241028.1120.016 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Ueki, Y.; Yoshiie, R.; Naruse, I.; Matsuzaki, S. Effect of hydrogen gas addition on combustion characteristics of pulverized coal. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 161, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lei, X.; Wang, C.; Jing, X.; Liu, W.; Dong, L.; Wang, Q.; Lu, H. Numerical Simulation Study of Hydrogen Blending Combustion in Swirl Pulverized Coal Burner. Energies 2024, 17, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Huang, S.; Qian, B.; Wang, K.; Gao, N.; Lin, X.; Shi, Z.; Lu, H. Numerical Simulation of Hydrogen–Coal Blending Combustion in a 660 MW Tangential Boiler. Processes 2024, 12, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Yuan, Z. Research progress of hydrogen energy and metal hydrogen storage materials. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 55, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momirlan, M.; Veziroglu, T.N. The properties of hydrogen as fuel tomorrow in sustainable energy system for a cleaner planet. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2005, 30, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yartys, V.A.; Lototskyy, M.V.; Linkov, V.; Pasupathi, S.; Davids, M.W.; Tolj, I.; Radica, G.; Denys, R.V.; Eriksen, J.; Taube, K.; et al. HYDRIDE4MOBILITY: An EU HORIZON 2020 project on hydrogen powered fuel cell utility vehicles using metal hydrides in hydrogen storage and refuelling systems. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 35896–35909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, R.M. A new gaseous and combustible form of water. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2006, 31, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Feng, Z.; Guo, Q.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Y. Catalytic Effect of Brown Gas on Low Oxygen Combustion of Pulverized Coal. J. Shenyang Inst. Eng. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 20, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Li, F.; Li, K. Numerical Simulation of Effect of Primary Air Mixed with Hydrogen and Oxygen on Furnace Temperature of Coal-fired Boiler. J. Eng. Therm. Energy Power 2023, 38, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, X.; Hou, B.; Zhou, H. Combustion stability and emission characteristics of a pulverized coal furnace operating at ultra-low loads assisted by clean gas (HHO) from water electrolysis. Fuel 2024, 370, 131811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, X.; Hou, B.; Zhou, H. Experimental study on the effects of co-firing mode and air staging on the ultra-low load combustion assisted by water electrolysis gas (HHO) in a pulverized coal furnace. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 117, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Kang, X.; Hou, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H. Comparative experimental study on the co-firing characteristics of water electrolysis gas (HHO) and lean coal/lignite with different injection modes in a one-dimensional furnace. Fuel 2024, 378, 132968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 212-2008; Proximate Analysis of Coal. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 476-2001; Ultimate Analysis of Coal. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2001.

- Moffat, R.J. Describing the uncertainties in experimental results. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 1988, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Wang, Z.; Costa, M.; He, Y.; Cen, K. Ignition and combustion of single pulverized biomass and coal particles in N2/O2 and CO2/O2 environments. Fuel 2021, 283, 118956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, N.A.; Gupta, M.M.; Joshi, S.S. Effect of oxy hydrogen gas addition on combustion, performance, and emissions of premixed charge compression ignition engine. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 227, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y. Coal-nitrogen release and NOx evolution in the oxidant-staged combustion of coal. Energy 2017, 125, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigge, L.; Ströhle, J.; Epple, B. Release of sulfur and chlorine gas species during coal combustion and pyrolysis in an entrained flow reactor. Fuel 2017, 201, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, E.; Panahi, A.; Ren, X.; Levendis, Y.A. Curtailing the generation of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions by blending and oxy-combustion of coals. Fuel 2016, 181, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, K.; Ichimura, R.; Hashimoto, G.; Xia, Y.; Hashimoto, N.; Fujita, O. Effect of fuel ratio of coal on the turbulent flame speed of ammonia/coal particle cloud co-combustion at atmospheric pressure. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 4131–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M. Flame Propagation Velocity for Co-combustion of Pulverized Coals and Gas Fuels. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 6305–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Jia, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z. Selective catalytic reduction of NOx by H2 over Pd/TiO2 catalyst. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Lu, G.Q.; Rudolph, V. The kinetics of NO and N2O reduction over coal chars in fluidised-bed combustion. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1998, 53, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, D.; Li, B.; Wang, P.; Tan, H.; Sun, S. Effects of flue gases (CO/CO2/SO2/H2O/O2) on NO-Char interaction at high temperatures. Energy 2019, 174, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Wei, B.; Zhang, L.; Tan, H.; Yang, T.; Mikulčić, H.; Duić, N. The ash deposition mechanism in boilers burning Zhundong coal with high contents of sodium and calcium: A study from ash evaporating to condensing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 80, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.-Q.; Low, F.; De Girolamo, A.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L. Characteristics of Ash Deposits in a Pulverized Lignite Coal-Fired Boiler and the Mass Flow of Major Ash-Forming Inorganic Elements. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 6198–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, S.; Huang, Q.; Yao, Q. Fine particulate formation and ash deposition during pulverized coal combustion of high-sodium lignite in a down-fired furnace. Fuel 2015, 143, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.L.; Junker, H.; Baxter, L.L. Pilot-Scale Investigation of the Influence of Coal—Biomass Cofiring on Ash Deposition. Energy Fuels 2002, 16, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhiyanon, T.; Sathitruangsak, P.; Sungworagarn, S.; Pipatmanomai, S.; Tia, S. A pilot-scale investigation of ash and deposition formation during oil-palm empty-fruit-bunch (EFB) combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 96, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Pan, W. A review on release and transformation behavior of alkali metals during high-alkali coal combustion. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 70, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.-P.; Li, X.; Wei, B.; Tan, P.; Fang, Q.-Y.; Chen, G.; Xia, J. Release and transformation characteristics of Na/Ca/S compounds of Zhundong coal during combustion/CO2 gasification. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Han, G.; Fan, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, M.; Guo, M.; Fang, Y. The effects of Na2O/K2O flux on ash fusion characteristics for high silicon-aluminum coal in entrained-flow bed gasification. Energy 2023, 282, 128603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Baláš, M.; Lisý, M.; Lisá, H.; Milčák, P.; Elbl, P. An overview of slagging and fouling indicators and their applicability to biomass fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 217, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J.; Li, S.; Song, Q.; Yao, Q. The Electron Microscopy Study of PM1 in The Pulverized-Coal Flame. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2008, 871–875. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Ow72tX7v2w1Gr6iTI97WlrapRZPaZobh1KJzamlcLRP4Q6EoAGMpcvNGggp_zicM-j1tTda7nqsUv3lkhCvndpCX6brrDII4Hk0a-M3V6t0iE3zUJdKl0wjs4ob1QqqvxLmDmr13l-lTLomBh2ChiqyJr0034rIKfpAoe7io5P0e0N_aGbP20A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Tan, J.; He, Y.; Cen, K. Co-firing characteristics and fuel-N transformation of ammonia/pulverized coal binary fuel. Fuel 2023, 337, 126857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, S.; Guan, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Wollastonite addition stimulates soil organic carbon mineralization: Evidences from 12 land-use types in subtropical China. CATENA 2023, 225, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.