Abstract

The conversion of biowaste into biofertilizer offers a sustainable alternative to synthetic fertilizers by supporting nutrient recycling and agricultural productivity. However, industrial pelletization can compromise the viability of microorganisms essential for biofertilizer function. In this study, a 40/60 (dry wt%) blend of biochar and commercial potting mix (biowaste blend) was used to produce a biochar biofertilizer (BCBF) through pelletization. Microbial population dynamics were then assessed at different stages of the BCBF pelletization process and under variations in key pelleting parameters—moisture content (15–35%), die surface temperature (70–180 °C), and feed rate (75–150 lb/h). The results showed that fungal and protozoan populations increased during the composting stage of BCBF, but declined to undetectable levels following drying and coating of the BCBF pellets. Bacterial populations increased after composting, but decreased substantially after pelleting and subsequent storage of the BCBF, while actinobacteria remained low throughout the pelletization process. Elevated temperatures and moisture loss were identified as major contributors to microbial inactivation during pelletization. These findings demonstrate that careful control of pelletization parameters is essential for maintaining microbial viability, thereby supporting the development of higher-quality, microbially active biochar-based biofertilizers.

1. Introduction

While boosting short-term agricultural output, extensive reliance on synthetic fertilizers has caused long-term environmental degradation [1,2]. Continuous, high-volume application of synthetic fertilizer is a key driver of soil quality decline, diminishing soil organic matter, disrupting microbial communities, and altering soil pH [3,4]. Producing synthetic fertilizers is energy-intensive. Their field application releases greenhouse gases, most notably nitrous oxide (N2O), which has a global warming potential ~300 times greater than that of carbon dioxide (CO2) [5,6]. These impacts underscore the need for sustainable agricultural practices that mitigate the drawbacks of conventional fertilizer use. In this context, biofertilizers derived from biowaste offer a promising, circular alternative to modern agriculture [7].

However, a critical knowledge gap remains in how to process biowaste into biofertilizers without compromising the microbial integrity essential for agronomic performance. Biofertilizers enhance agricultural productivity by supplying mineral nutrients through microbial enhancement processes. These beneficial microorganisms, including plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi, actively improve the soil structure, increase water retention, and enhance nutrient bioavailability [8]. Certain bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen () into a plant-available form via biological nitrogen fixation [9], while others secrete organic acids that solubilize locked-up phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) from the soil matrix [10]. This biological activity not only boosts crop yields, but also reduces the need for synthetic inputs, thereby promoting long-term agricultural resilience and sustainability.

But the direct, non-processed use of biowaste is often impractical and inefficient. Raw biowastes typically possess a low nutrient density, are difficult to handle, and may contain pathogens that pose health risks [11]. Appropriately processed biowaste into biofertilizers can safely and effectively return macro- and micronutrients to the soil while simultaneously introducing beneficial microorganisms vital for soil health and plant vitality [12]. Table 1 summarizes examples where biowaste resources were processed to convert into biofertilizer. Pelletizing is a widely adopted process, as shown in Table 1, for converting biowaste into biofertilizer. This process creates uniform biofertilizer particles that are easily stored, transported, and applied using conventional fertilizer equipment. Due to their convenience and ease of use, many farmers utilize locally fabricated or modified pellet machines—often with suboptimal or non-standard specifications—to produce biofertilizer. A significant portion of the organic fertilizer industry relies on this business model.

Table 1.

Summary of typical biofertilizer production processes from literature.

The pelletization process, while effective for biowaste-to-biofertilizer production, introduces a significant challenge: preserving the viability of the microorganisms that define the biofertilizer’s value. A negative impact on the microbial condition in the biofertilizer has been indicated by various research, arising from the thermo-mechanical operating conditions of the pelleting machine in biowaste conversion. Recent experimental work by Rubel et al. [15] revealed that pelleting of biowaste (a mixture of biochar and manure in this research) to biofertilizer significantly reduced the microbial population after processing, with the viability turning to zero at the end of the pelletization. Thus, the biofertilizer company focuses on microbial inoculation after the biofertilizer-making process to introduce new beneficial microorganisms [7]. This has been considered the easiest way to regain microbial benefit from the biofertilizer. These studies raise critical questions about biofertilizer processing and the quality of the final product, which is often produced by local farmers and applied in the field without a proper microbial assessment.

Pelleting involves a complex sequence of operations, including dewatering, mixing, compaction under high pressure, and the generation of frictional heat [25]. The temperature inside a pelletizing machine can reach high values, and the high-pressure compaction subjects microbial cells to intense mechanical shear stress, which can cause cellular lysis and death [26]. Furthermore, the rapid reduction in moisture content induces severe osmotic stress on microbial communities, further reducing their population. Thus, despite the proven agronomic benefits and post-application soil microbiology of biofertilizers derived from biowaste, a critical knowledge deficit persists regarding the process dynamics of microbial inactivation during the industrial pelletization process. Specifically, there is an absence of quantitative studies that directly correlate thermo-mechanical processing parameters (e.g., the moisture of the feed, die surface temperature, feed rate, etc.) with the survival rate of microbial communities within the biofertilizer matrix. This lack of process validation and microbial kinetics data impedes the rational design of low-stress pelleting protocols and the optimization methods necessary for maximum microbial viability in the biowaste-to-biofertilizer process.

To address this critical knowledge gap, the present study investigates microbial population dynamics throughout a lab-scale biofertilizer pelletization process and evaluates the influence of key processing parameters on microbial survival. Using a pilot-scale manufacturing setup that simulates industrial conditions, a 40/60 (dry wt%) blend of biochar and commercial potting mix (referred to as biowaste) was pelletized. Biofertilizer samples were collected at multiple stages of production to quantify changes in microbial populations, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and actinobacteria. Under controlled variations in the moisture content (15–35%), die surface temperature (70–180 °C), and feed rate (75–150 lb/h), pelletization was performed for biowaste to see the effect of key pelleting parameters. Overall, this study aims to quantify how pelletization conditions affect microbial survival and to provide a clearer understanding of microbial population dynamics across the biofertilizer production process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biowaste Sample Preparation

This study utilized a 40/60 (dry wt%) mixture of potting mix (Miracle-Gro Potting Mix, Walmart, Brookings, SD, USA) and biochar to create a biowaste sample. The ratio was selected to ensure that the blend maintained a suitable moisture content (50–60%) for microbial growth in the initial blend, following the approach reported by Rubel et al. [15]. The biochar was sourced from Advanced Renewable Technology International, Inc. (Des Moines, IA, USA) and produced from wood at 500 °C. Its properties were as follows: 78.7% (wt/wt) organic carbon, 0.71% (wt/wt) nitrogen, 4.38% (wt/wt) ash, and a pH of 7.55. The raw potting mix had an initial moisture content of 74.2%, and the blend had an initial moisture content of 58.31%, while the biochar’s moisture content was 2.91%. Mixing was performed for one hour in a commercial rotating drum operated at 50 rpm at ambient temperature (23–25 °C); no external heat was applied. Following mixing, the blend was covered and stored for 14 days (23–25 °C) to undergo mesophilic composting and allow moisture to infuse evenly into the biochar. The blend was rotated once to maintain gentle aeration. This incubation step resulted in a final moisture content of 23.7% before pelletization.

2.2. Pelletizing Conditions

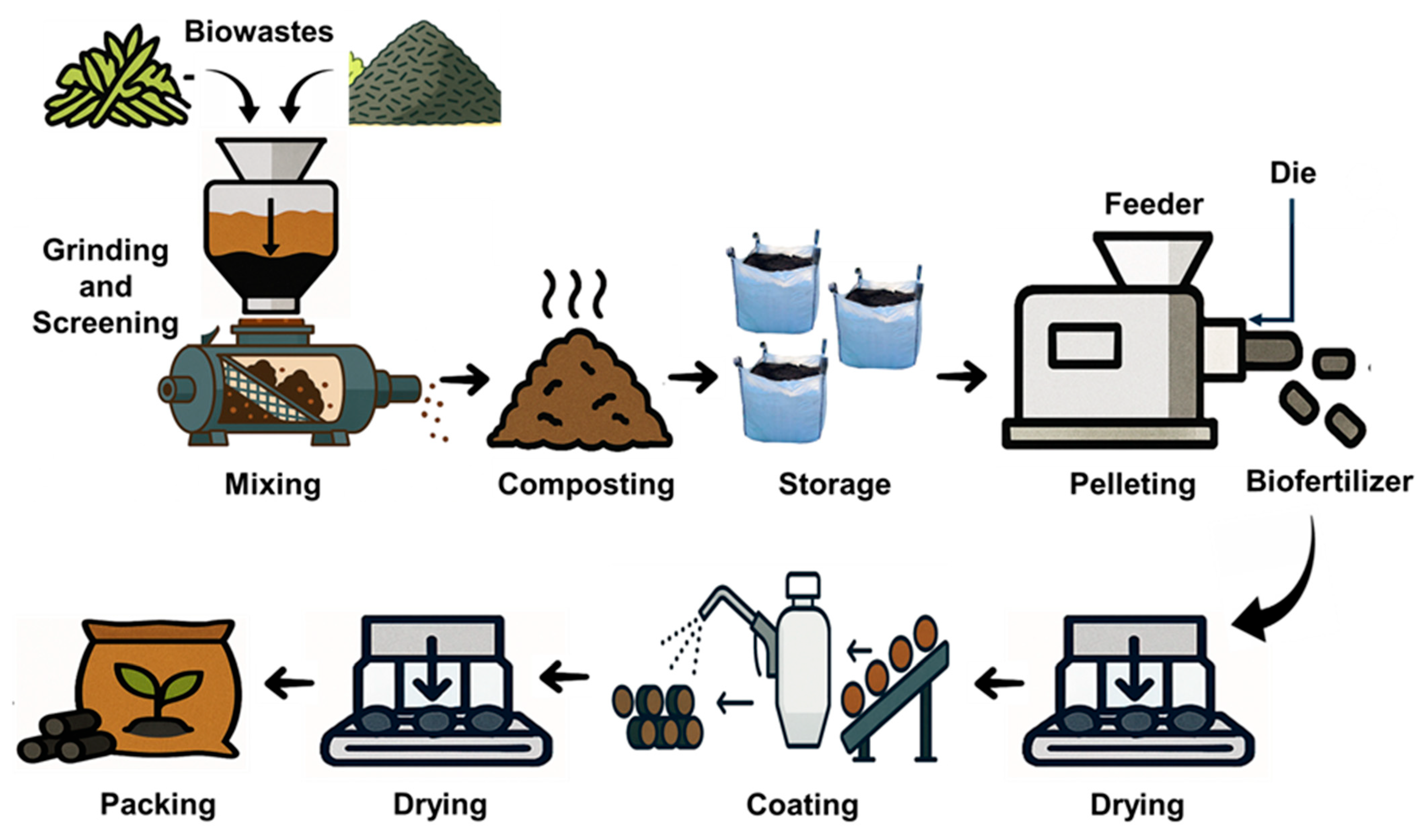

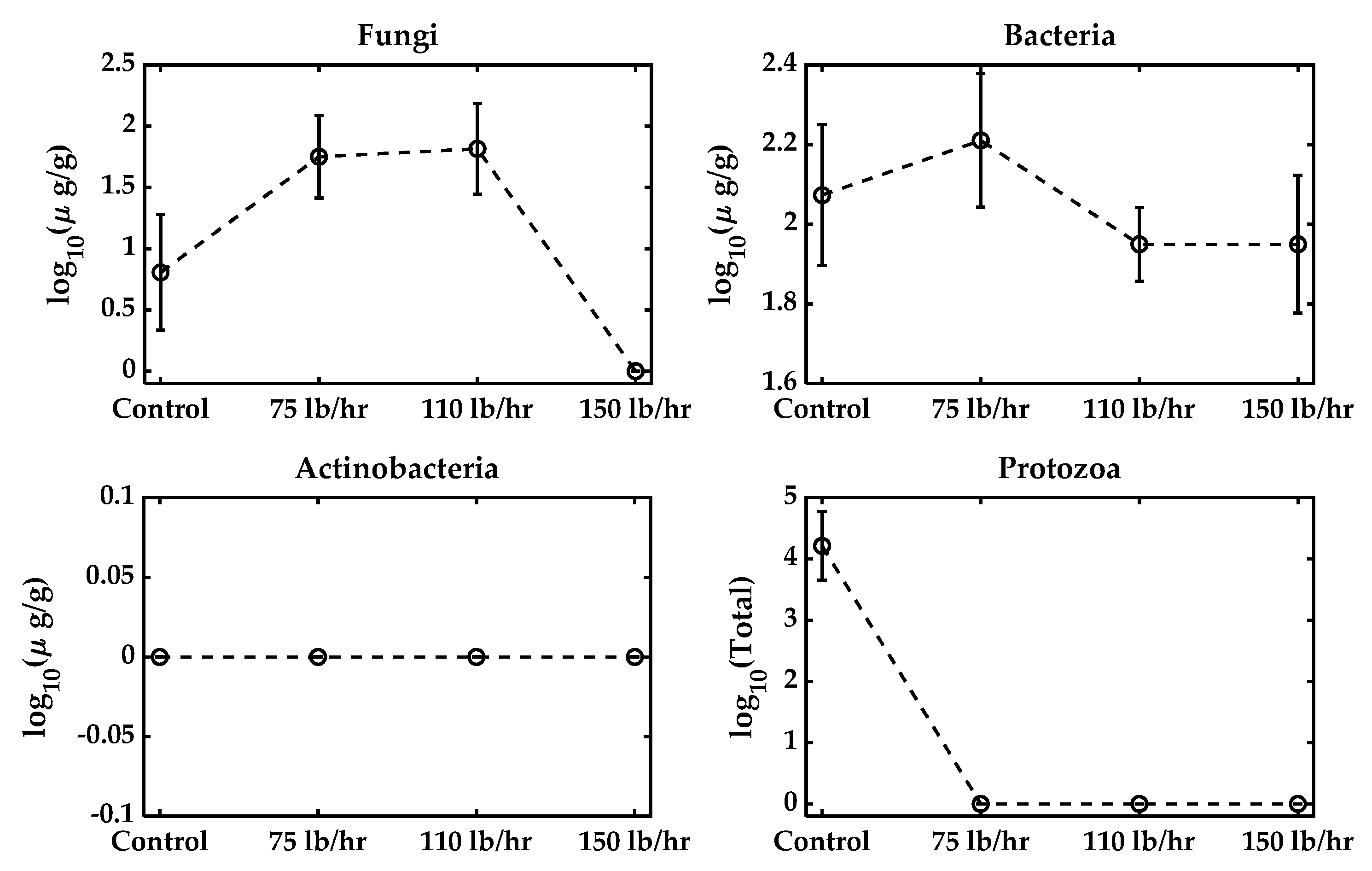

The study involved two phases: (1) assessing the different stages of biochar-based biofertilizer (BCBF) pelletization and (2) assessing the effect of the pelletization parameters on microbial viability. The pilot-scale pelletization facility, located at the Bioprocessing Lab of South Dakota State University, included screening and grinding processes before the biowaste material was fed to the pelletizer. The pelletizing machine used was Hobart, Troy, Ohio, Model 4146. The die diameter was 3.5 inches, capable of producing 2 mm pellets, and was operated at 60 lb/h. The biowaste blend was fed continuously into the die chamber, where compaction and friction generated the heat necessary for pellet formation. No binders were added during pelletization. Each batch required less than 20 s of residence time inside the die channel before exiting as cylindrical pellets. The die surface temperature was monitored using an infrared temperature sensor, and cooling was controlled through periodic water spraying to maintain consistent thermal conditions during pelletization. The sequential stages of this production workflow are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the industrial process involved in this study.

To observe the effect of the full production line, the composted biowaste blend was immediately processed after the 14-day incubation. Fresh pellets retained a high moisture (15–25%), so they were air-dried indoors for ten days, reducing the moisture to 6.12%. After drying, the pellets were spray-coated with a 5% polylactic acid (PLA) solution in chloroform to isolate and assess the impact of the coating step alone to evaluate coating as a unique processing step. The coated pellets were left under ambient conditions for two days to allow for complete solvent evaporation. Samples were collected at seven stages of the pelletization: (1) raw constituents (compost and biochar), (2) biowaste (blended compost and biochar), (3) biowaste after two weeks of composting, (4) post-pelleting, (5) post-drying, (6) post-coating, and (7) after three months of storage of the coated pellets. In the second phase, the biowaste (20.1% moisture) was pelleted under controlled variations in the moisture (15%, 25%, 35%), die surface temperature (70 °C, 110 °C, 180 °C), and feed rate (75, 110, 150 lb/h). The feed rate was adjusted through a dedicated feed-control hopper (Figure 1).

It should be noted that the temperature recorded during pelletization represents the die surface temperature, not the surface or internal temperature of the pellets. Due to evaporative cooling and the heterogeneous nature of the wet feed material (biowaste in this case), the internal granule temperature can be different, but the worst can be the die surface temperature for the pelleted BCBF. The BCBF samples were collected immediately after being completed under each key varying condition for a microbial population analysis.

2.3. Microbial Analysis

A microbial analysis was conducted at Sprouting Soil (Auburn, CA, 95603, USA). The plate count method was used to assess microbial populations. For fungi, potato dextrose agar was utilized, while nutrient agar was used for the total bacteria. Actinobacteria were quantified using Actinomycete isolation agar, a selective medium containing sodium propionate and glycerol that suppresses fast-growing bacteria and fungi, thereby promoting actinomycete colony development. The plates were incubated at 28–30 °C. Protozoa were assessed using a dilution-plating method on non-nutrient agar overlaid with heat-killed Escherichia coli as a food source. Microbial groups were quantified and expressed as log10 (µg/g). To assess microbial recovery after processing, dry pelleted and coated biofertilizer particles were subjected to a rehydration test by soaking for 4 days. Approximately 2–3 g of each particle type was placed in 100 mL of sterile distilled water at room temperature (23–25 °C). The samples were left undisturbed for four days, with only one gentle handshake applied on day four to check the disintegration. After rehydration, the disintegrated mixture was homogenized and analyzed using the same microbial plating procedures. This method allowed for an evaluation of dormant but viable microbial populations.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed in R4.5.1. For the processing-step experiment, differences among the stages were tested using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. Parameter variation experiments (moisture, temperature, feed rate) were also evaluated using an ANOVA + Tukey’s HSD. Normality and variance homogeneity were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. The data were log-transformed when assumptions were violated; otherwise, Welch’s ANOVA was applied. Each treatment had three biological replicates, and the results are reported as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of the Pelletization Process on the Microbial Population

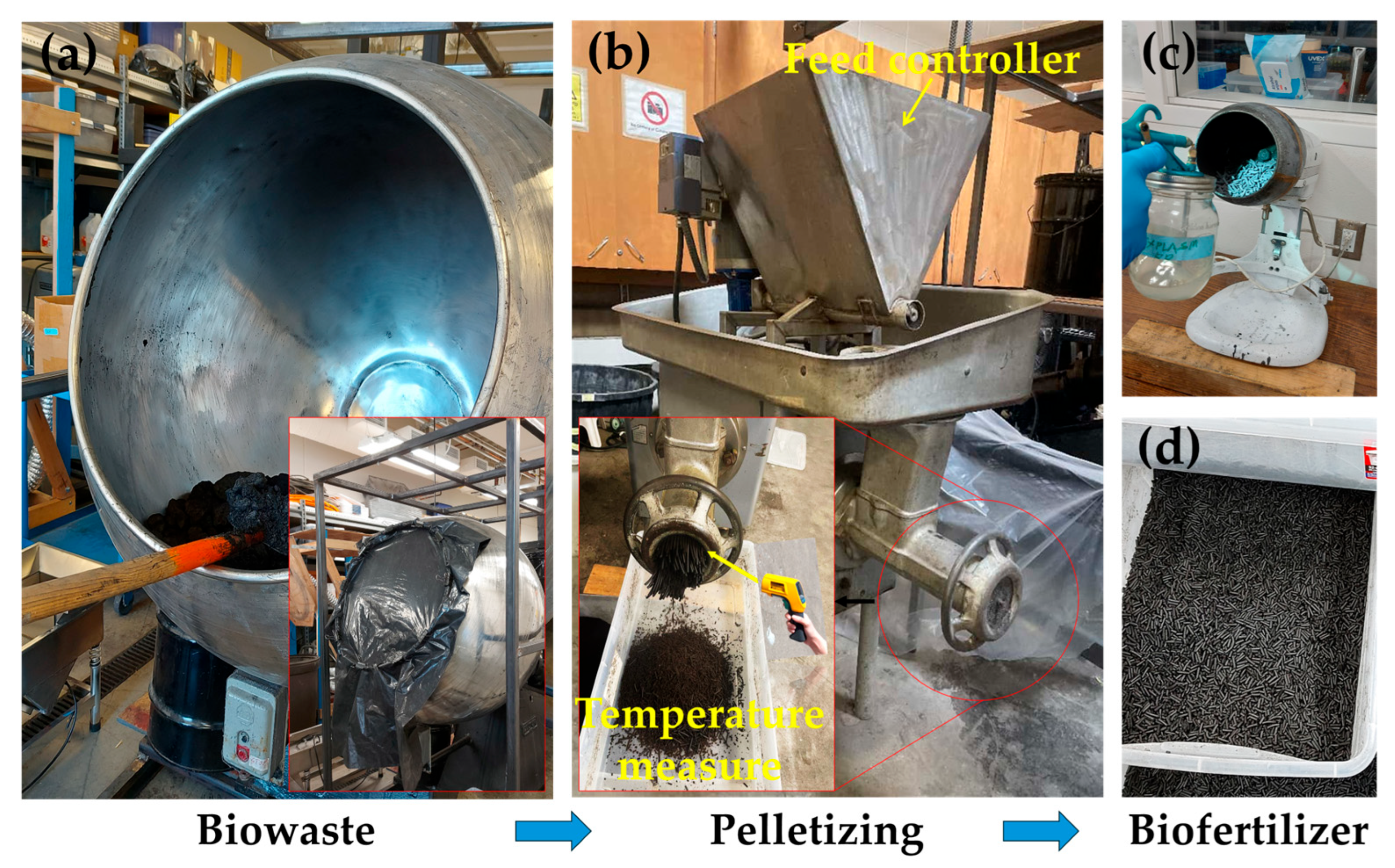

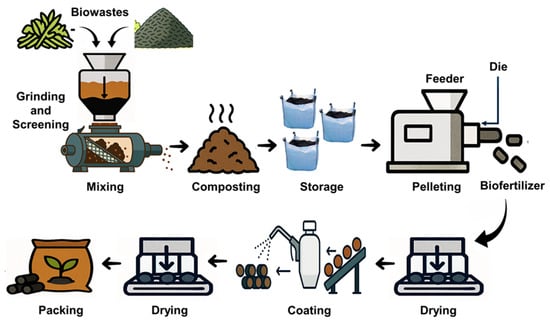

Biofertilizers provide substantial agronomic benefits, promoting soil fertility and increasing crop yield by up to 10–40%. They also enhance crop quality by increasing the protein content, essential amino acids, and vitamins through microbially mediated nutrient transformations [27,28,29]. This efficacy fundamentally depends on live microbial strains that colonize the rhizosphere and facilitate nutrient availability. The results of the present study demonstrate that industrial processing of biowaste into biofertilizer diminishes this critical microbial integrity. The typical process flow shown in Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental stages, where each step introduces adverse impacts on viability of microbial communities. Figure 2 shows the pellet machine used and the final product after coating.

Figure 2.

Biowaste-to-biofertilizer production. (a) Biochar–potting mixture blending, (b) pelletizing of the mixture, and (c) coating of the dried biofertilizer particles. Drying was performed before the coating step. (d) The final biofertilizer particles. The pellets shown in panels (c,d) are the same biochar-based particles. The slight color difference is due to lighting effects.

During biofertilizer formulation, selecting carrier materials with a high porosity and water-holding capacity and a neutral pH is vital for the physical and chemical compatibility necessary to sustain microbial strains [30,31,32]. Table 2, which presents the microbial population across the conversion steps, clearly shows a general reduction across the entire production line. Fungi and protozoa were observed to be particularly vulnerable to the cumulative mechanical and chemical stresses, leading to their complete elimination after the coating and storage stages (Table 1). In addition to the direct thermal and mechanical aspects, multiple physical, chemical, and biological factors concurrently influenced microbial survival during production [33]. The fungal population decreased upon initial blending, likely due to the rapid moisture reduction (from 74.2% in the potting mixture to 58.31% in the blend). Subsequently, the population increased significantly after the two-week composting period, reaching a peak of 2.91 log10 (µg/g) (p ). This recovery is consistent with the observation that fungi often activate in the later stages of decomposition, benefiting from the moisture equalization within the biowaste. Although no visual fungus formation (mold) was observed during the two weeks, indicating a slower establishment phase, the quantitative data confirm population recovery.

Table 2.

Status of the microbial population in different steps of fertilizer-making at room temperature for the biowaste blends of 23.7% moisture at 60 lb/h. Different letters within a column indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

This period of moisture reduction and regular aeration differs from active composting, yet appears favorable for fungal growth over an extended timeframe. Post-pelleting caused a reduction in the fungal population, although not statistically significant (p ). However, the dry pelleted particles lost a significant population (p ) and were reduced to zero onward after the coating process and three months of storage.

The bacterial population exhibited a similar recovery phase with greater persistence. The two-week composting period increased the bacterial population, which rose by approximately 0.63 log10 (µg/g) units (an approximately 4.5-fold increase on the linear scale) compared to the initial blend. The initial moisture level of the biowaste (58.31%) combined with the mild, anaerobic temperature (23–25 °C) promoted bacterial growth. Furthermore, biochar, while microbially inert initially, is known to be an active material that participates in redox reactions, facilitating both abiotic and microbial transformations, thereby enhancing microbial growth after being introduced to other sources [27,34,35]. The population then dropped significantly in the post-pelleting stage (p ) and through the rest of the processing, but notably, did not drop to zero even after coating with a 5% PLA solution and three months of storage (Table 2). The reduction in the bacterial count is likely attributable to osmotic stress from moisture loss (dropping from 23.70% pre-pelleting to 18.11% instantly post-pelleting) and chemical stress from the use of a chloroform solvent in the coating stage. While specific studies using chloroform on biofertilizer were not found, related research has reported that chloroform fumigation in soil is highly effective, killing 99% of bacteria [36]. The persistence of the remaining bacterial population under these harsh conditions suggests an exceptional resilience, likely via endospore formation.

Actinobacteria share characteristics of both bacteria and fungi, and their dynamic behavior in complex mixtures is often difficult to understand. The population became zero in the biowaste after two weeks and remained zero in the post-pelleted particles (Table 2). However, some Actinobacteria reappeared in the particle-drying, coating, and storage steps. Since some bacterial populations remained in the final steps, it is possible that some Actinobacteria were reactivated by mycelial growth, which is the secondary production or repair stage of microbes from surviving dormant structures. The protozoa population showed a reduction after mixing and a two-week incubation period. This suggests that the initial mixing/composting stages posed a greater long-term environmental stress than the rapid thermo-mechanical shock of pelleting, as no significant difference in the protozoa population was observed post-pelleting. However, the subsequent drying and coating steps led to complete elimination (Table 2), which is expected, as protozoa require high water activity for survival and reproduction.

The survival of the microbial population was also assessed via a rehydration test. Dry pelleted biofertilizer and coated biofertilizer particles were soaked in water, dispersing after approximately four days with a light shake. As presented in Table 3, biofertilizer particles from both the dry pelleted and coated stages show that bacteria and protozoa regained substantial populations after soaking, indicating that these groups may enter a dormant but recoverable state during processing. In contrast, fungi and actinobacteria showed no recovery, suggesting that their viability was likely irreversibly lost under the processing conditions used in this study.

Table 3.

Status of the microbial population in dry and coated particles after soaking for four days in water. Different letters within a column indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

3.2. Effect of Pelletization Parameter on Microbial Population

While biofertilizer pelleting is designed to improve the handling, shelf life, and marketability, the inherent mechanical and thermal stresses pose significant challenges to microbial survival. Among the most critical steps are drying and pelletization, as they introduce significant heat and mechanical stress. Most microbial strains are sensitive to temperatures above 45 °C. Pelletizing machines often operate at high friction temperatures (80–200 °C) that drastically reduce microbes [37]. High pelleting temperatures can denature microbial proteins and enzymes and damage cell membranes. With this perspective, a parametric test was performed during the pelleting process to assess the effect of three major factors—moisture, temperature, and feed rate—on the microbial population. The feed rate passively represents the force inside the pellet channel [38,39]. Note that the biowaste used in this case was the same for this test, but due to the time difference, the sample lost moisture from 23.7% to 20.1%.

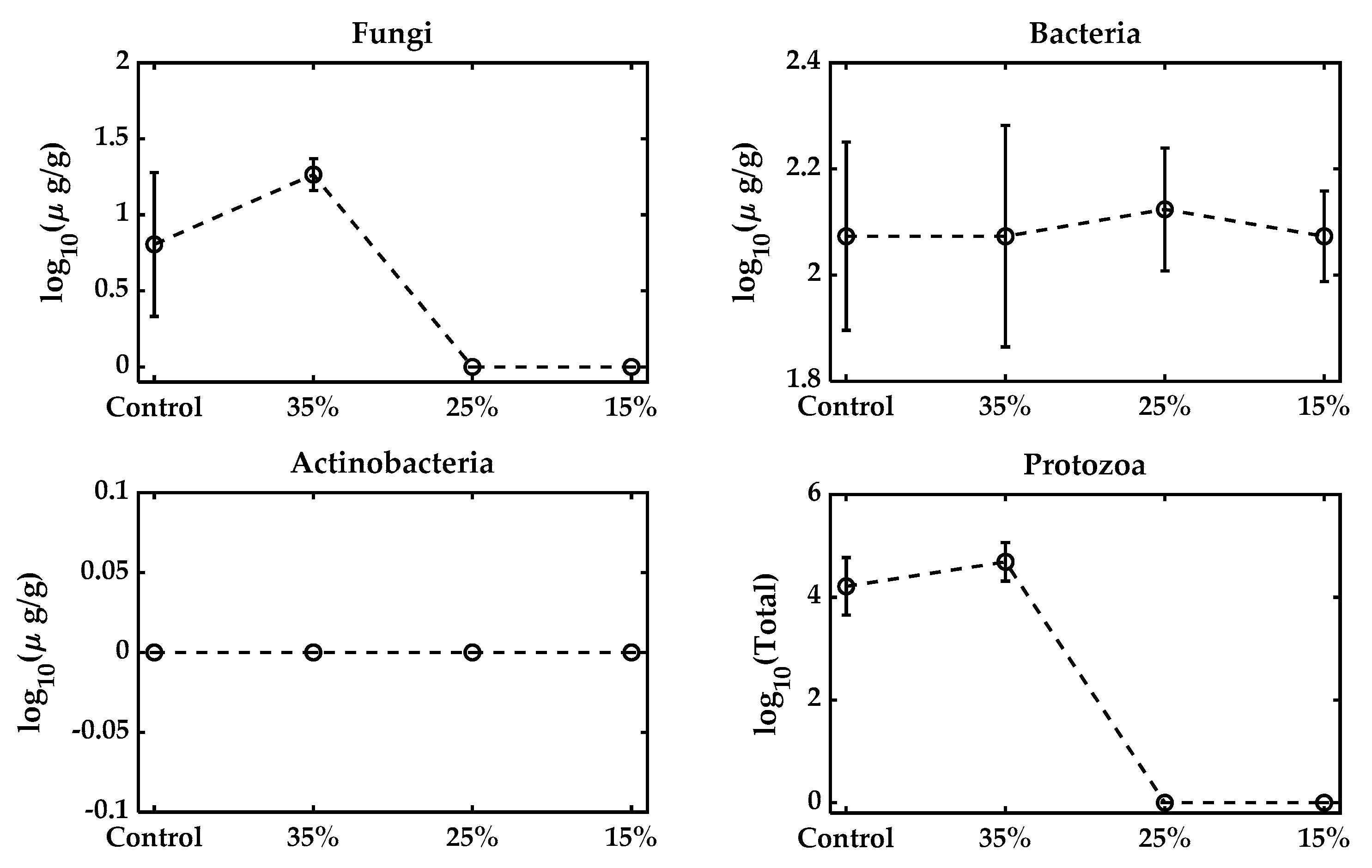

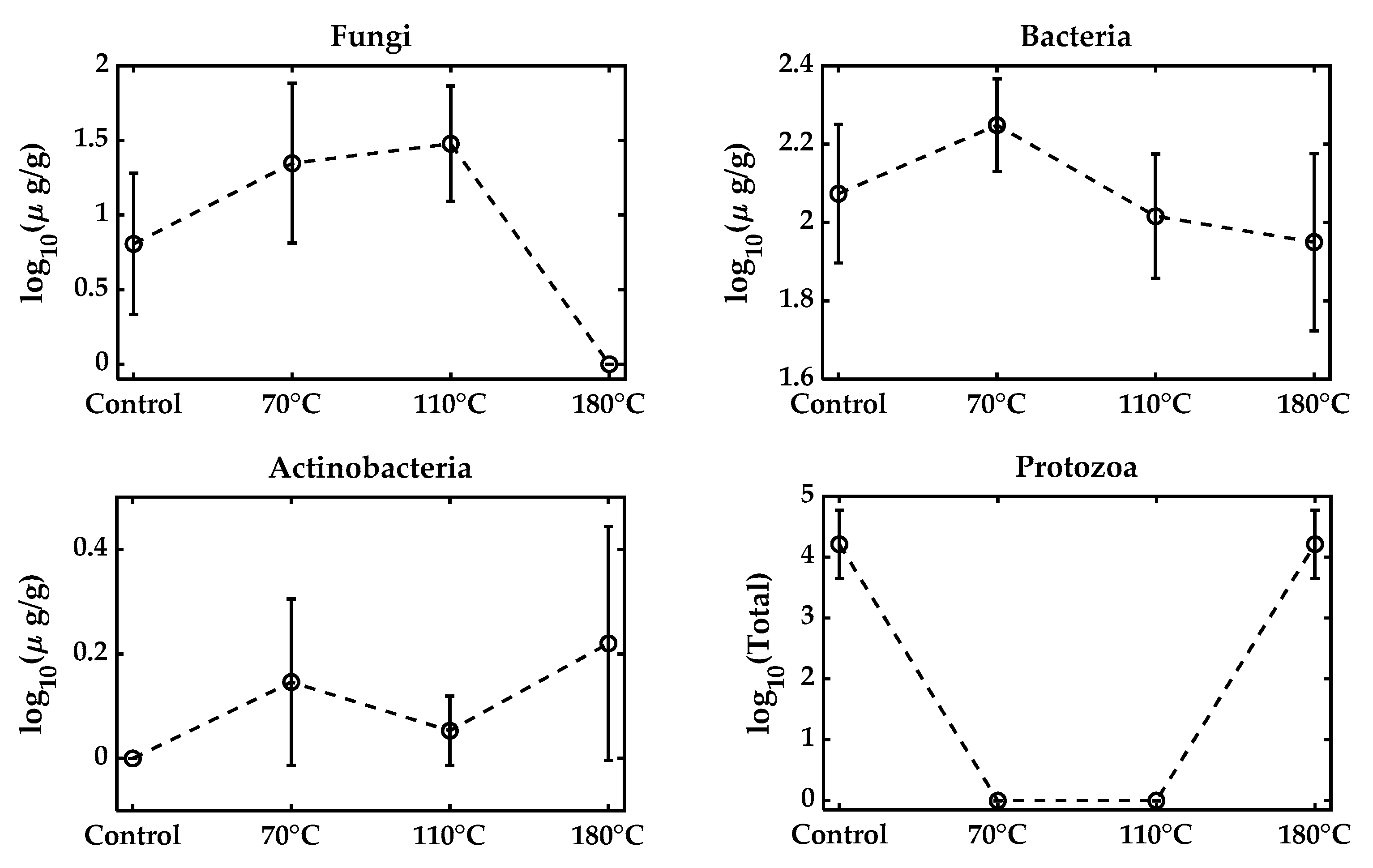

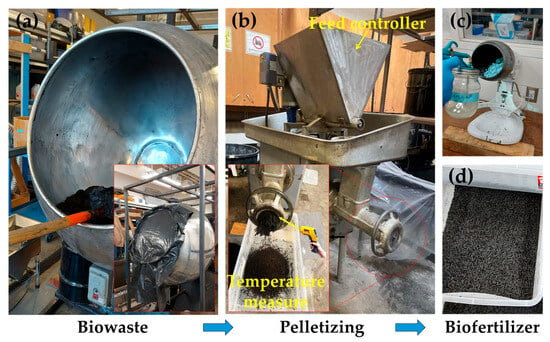

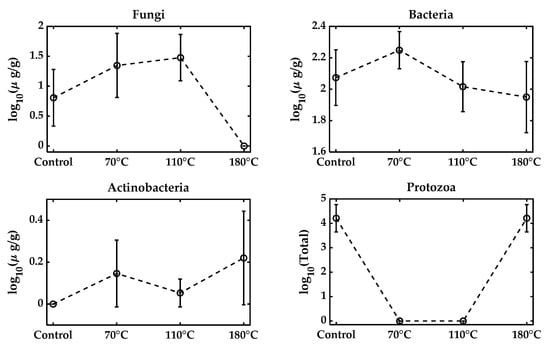

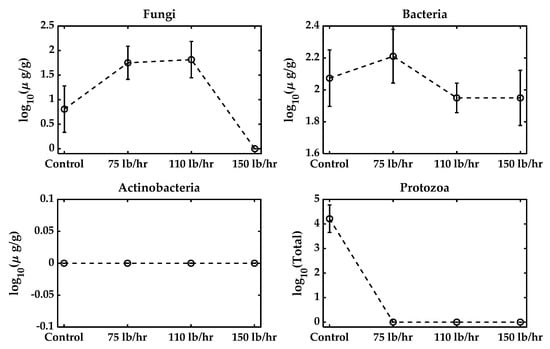

All microbial metabolic functions that require 40–60% are typically optimal for microbial growth. While moisture reduction is necessary to prolong the shelf life, excessive desiccation reduces water activity and leads to microbial death. Formulations typically aim for a final moisture level around 20–30%, but air-drying to levels as low as 6–10% for shelf stability significantly reduces survival [40,41], consistent with our observations (Table 2). Similar results were observed in the varying moisture pelleting process, keeping the feed rate and temperature unchanged at the 15%, 25%, and 35% levels, as shown in Figure 3. The fungal population increased with the adjusted 35% moisture, but reduced to zero at 25% and 15% moisture. Bacteria, on the other hand, remained approximately constant. No presence of actinobacteria was found in the samples, and the total protozoa were also reduced to zero with moisture reduction. Figure 4 presents the effect of varying the pelleting temperatures on the microbial populations within the biofertilizer. The results demonstrate that increasing the temperature during pelletization leads to a pronounced reduction in the viability of key microbial groups, especially the fungal population, which becomes zero. Most microbial strains are sensitive to temperatures above 60 °C, and the pelleting process here exposes them to much higher temperatures (110~180 °C), which can be considered extreme [42,43]. Bacteria exhibit some resilience, but also experience significant losses as the temperature rises, while actinobacteria detected at three different temperatures had overlapped standard deviations.

Figure 3.

Microbial population with varying moisture levels from the original control mixture. The control biowaste was at 20.1% and not pelleted. This moisture was adjusted to 35%, 25%, and 15% and pelleted at a feed rate of 60 lb/h.

Figure 4.

Microbial population with varying temperatures from the original control mixture. The control biowaste mixture was at 20.1% moisture and pelleted at a feed rate of 60 lb/h at temperatures of 70 C, 110 C, and 180 C. A high temperature was achieved by removing cooling to simulate the extreme heat stress.

The total protozoa were detected at zero at 70 °C and 110 °C, but a surprising presence was noted at 180 °C. This might have resulted from the sample heterogeneity, as the potting mixture particle size was coarse. These findings highlight that thermal stress is a major factor contributing to microbial inactivation during biofertilizer production. However, the maximum recorded temperature reflects only the die surface temperature and not the internal temperature of the granules; the microbial reductions observed in this study should be interpreted as possible worst-case temperature exposures.

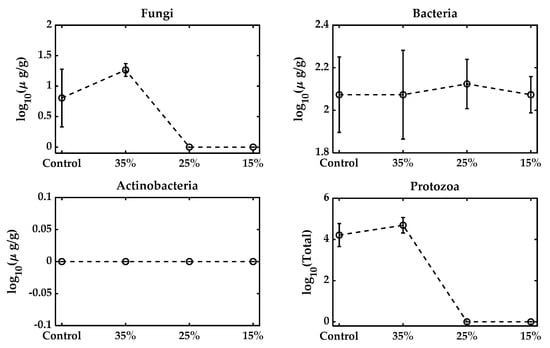

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of different feed rates during pelletization on microbial survival. As the feed rate increased from 75 lb/h to 150 lb/h, the mechanical stress within the pelletizer intensified, subjecting microbial cells to greater shear forces [39]. Overall, the fungi and protozoa exhibited the lowest structural resistance to the feed rate (passive mechanical shear force). Fungal vegetative cells and hyphae lack the robust structures of bacterial endospores, making them susceptible to rupture. Protozoa, being larger cells sensitive to moisture, are highly susceptible to deformation and collapse under the intense, rapid pressure cycles of pelleting. Their populations were therefore reduced to zero across all the tested feed rates (Figure 5, inferred from Figure 3 and Table 2 data). The persistence of the bacterial fraction, even at the maximum throughput of 150 lb/h, relied on the structural advantage of spore formation. This tolerance threshold against mechanical failure ensures that the bacterial spores form the only reliable mechanism for maintaining viable counts in the final biofertilizer product, allowing potential metabolic reactivation (as shown in Table 2). Actinobacteria remained undetectable across all feed rates. The data indicate that, in addition to moisture and temperature, mechanical factors such as the feed rate play a significant role in determining microbial viability in the final biofertilizer product. Therefore, careful adjustment of the feed rate, alongside temperature control, is crucial for maximizing the retention of beneficial microbes during the pelleting process.

Figure 5.

Microbial population with a varying feed rate during pelletization. The control biowaste mixture was at 20.1% moisture and not pelleted. The feed rate was set to 75 lb/h, 110 lb/h, or 150 lb/h.

3.3. Study Limitations and Context

This study provides valuable insights; however, its generalizability is constrained by several limitations. First, the experiments were conducted using a single biowaste blend composed of biochar and potting mix. Consequently, the findings primarily reflect the behavior of this specific matrix and its indigenous microbial community. Other biowaste sources—such as livestock manure, poultry litter, or sewage sludge—differ significantly in their moisture-buffering capacity, organic composition, and microbial diversity, which could alter the survival thresholds under pelletization. Second, the parametric analysis was limited to three operational factors: the moisture content, die surface temperature, and feed rate. Additional parameters, including the pellet die geometry, compression pressure, residence time, and binder type, were not evaluated. Among these, of particular importance is the die’s length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio, which strongly influences shear stress and thermal gradients during compaction. The absence of this metric restricts a precise correlation between the mechanical energy input and microbial mortality. Third, microbial diversity was assessed only at the group level (fungi, bacteria, actinobacteria, protozoa) without species-level resolution. These limit understanding of strain-specific resilience mechanisms, such as spore formation or osmotic tolerance, which are critical for designing robust biofertilizer formulations. Additionally, the observed reappearance of protozoa and actinobacteria at certain processing stages might be due to methodological limitations rather than actual biological changes (Figure 4). The plate-count technique adopted in this study is highly sensitive to factors such as moisture variation, heterogeneity of the material, and microbial dormancy, all of which can result in inconsistent detection across different stages. In particular, the potting mixture used for biowaste blend preparation (Section 2.1) is inherently heterogeneous, and microorganisms present in very low numbers or in dormant form may remain below detection levels initially and become detectable only when conditions temporarily favor their revival.

4. Conclusions

This study quantified the effects of pelletization conditions on microbial populations during the production of BCBF. The results demonstrated that each processing step, particularly drying, coating, and storage, led to a marked reduction in the viability of the microbial population. Fungal and protozoan populations, which peaked after composting, were reduced to below detection levels in this study following drying and coating. Bacterial populations increased during composting, but declined substantially after pelleting and storage. Actinobacteria remained low throughout the process. A parametric analysis revealed that elevated die surface temperatures (up to 180 °C) and a reduced moisture content (as low as 15%) were major drivers of microbial losses, while higher feed rates intensified mechanical stress, further diminishing microbial viability. Rehydration tests indicated that dormant bacteria and protozoa could be reactivated, suggesting that some microbial resilience persists despite adverse pelletizing conditions. These findings lead to the importance of optimizing pelletization parameters to preserve microbial viability, thereby enhancing the agronomic value and sustainability of BCBF. Future work should explore additional processing variables and microbial diversity to further improve the pelletization of BCBF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I.R.; methodology, R.I.R. and L.W.; investigation, R.I.R., A.S., and S.M.S.A.; formal analysis, R.I.R.; data curation, R.I.R., A.S., and S.M.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.R.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; supervision, L.W.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by (1) USDA NIFA (award No. 2022-67021-37601) and (2) the USDA Hatch Project (Nos. 3AR742 and 3AH797), funded through the South Dakota Agricultural Experimental Station at South Dakota State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, X. The role of modern agricultural technologies in improving agricultural productivity and land use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1675657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: Recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X. Enhancing Soil Health through Balanced Fertilization: A Pathway to Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1536524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tu, C.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Gentry, L.F.; Hoyt, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Hu, S. Long-term impact of farming practices on soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools and microbial biomass and activity. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 117, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, U.; Rees, R.M. Nitrous oxide, climate change and agriculture. Outlook Agric. 2014, 43, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M.; Corona, F.; Verdugo, F. Waste-Derived Fertilizers: Conversion Technologies, Circular Bioeconomy Perspectives and Agronomic Value. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barea, J.M.; Pozo, M.J.; Azcón, R.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Microbial co-operation in the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1761–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Schmidt, M.A.; Hynes, M.F. Molecular Biology in the Improvement of Biological Nitrogen Fixation by Rhizobia and Extending the Scope to Cereals. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.B.; Acosta-Martinez, V. Cover Crops and Compost Influence Soil Enzymes during Six Years of Tillage-Intensive, Organic Vegetable Production. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, L.; Elphinstone, J.; Jensen, D.F. Literature review on detection and eradication of plant pathogens in sludge, soils and treated biowaste. Brux. Eur. Comm. DG RTD Framew. 2006, 6, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bulluck, L.R., III; Brosius, M.; Evanylo, G.K.; Ristaino, J.B. Organic and synthetic fertility amendments influence soil microbial, physical and chemical properties on organic and conventional farms. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2002, 19, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlaki, E.; Kermani, A.M.; Kianmehr, M.H.; Vakilian, K.A.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Ma, N.L.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Lam, S.S. Improving sustainability and mitigating environmental impacts of agro-biowaste compost fertilizer by pelletizing-drying. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 117412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, A.; Cochrane, R.; Jones, C.; Atungulu, G.G. Physical and chemical methods for the reduction of biological hazards in animal feeds. In Food and Feed Safety Systems and Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, R.I.; Wei, L.; Alanazi, S.; Aldekhail, A.; Cidreira, A.C.M.; Yang, X.; Wasti, S.; Bhagia, S.; Zhao, X. Biochar-compost-based controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer intended for an active microbial community. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiema, J.; Cofie, O.; Impraim, R.; Adamtey, N. Processing of fecal sludge to fertilizer pellets using a low-cost technology in Ghana. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 2, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniyan, I.A.; Akhere, O.M. Development of a Multi Feed Pelletizer for the Production of Organic Fertilizer. Am. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2017, 1, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammed, T.O. The effect of locally fabricated pelletizing machine on the chemical and microbial composition of organic fertilizer. Brit. Biotechnol. J. 2013, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwalina, P.; Obidziński, S.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Kowczyk-Sadowy, M.; Piekut, J.; Bagińska, E.; Mazur, J. Production and quality assessment of fertilizer pellets from compost with sewage sludge ash (SSA) addition. Materials 2025, 18, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza-Bagheri, A.A.G.; Hossein-Kianmehr, M.; Sarvastani, Z.A.T.; Hamzekhanlu, M.Y. The effect of pellet fertilizer application on corn yield and its components. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 2364–2371. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemzadeh, M. Process for Producing Odorless Organic and Semi-Organic Fertilizer. U.S. Patent 5,772,721, 30 June 1998. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US5772721A/en (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mieldazys, R.; Jotautiene, E.; Jasinskas, A.; Aboltins, A. Evaluation of physical mechanical properties of experimental granulated cattle manure compost fertilizer. In Proceedings of the Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunerová, A.; Müller, M.; Gürdil, G.A.K.; Šleger, V.; Brožek, M. Analysis of the physical-mechanical properties of a pelleted chicken litter organic fertiliser. Res. Agric. Eng. 2020, 66, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, E.; Brambilla, M.; Bisaglia, C.; Pampuro, N.; Pedretti, E.F.; Cavallo, E. Pelletization of composted swine manure solid fraction with different organic co-formulates: Effect of pellet physical properties on rotating spreader distribution patterns. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2014, 3, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, S.; Obeidat, W.; Al-Zoubi, N. Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts. e-Polymers 2022, 22, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Wright, C.T.; Kenny, K.L.; Hess, J.R. A Review on Biomass Densification Technologies for Energy Application; Idaho National Laboratory (INL): Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Bolan, N.; Prévoteau, A.; Vithanage, M.; Biswas, J.K.; Ok, Y.S.; Wang, H. Applications of biochar in redox-mediated reactions. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figiel, S.; Rusek, P.; Ryszko, U.; Brodowska, M.S. Microbially Enhanced Biofertilizers: Technologies, Mechanisms of Action, and Agricultural Applications. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Shabbir, S.; Manzoor, N.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Arshad, K.T.; Zohaib, A.; Farooq, T.H.; Sun, J. Recent advances in biofertilizer development. In Agricultural Nutrient Pollution and Climate Change; Hussain, N., Hung, C.Y., Wang, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 271–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakpirom, J.; Nunkaew, T.; Khan, E.; Kantachote, D. Optimization of carriers and packaging for effective biofertilizers to enhance oryza sativa L. growth in paddy soil. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Singh, B.K. Formulation challenges associated with microbial biofertilizers in sustainable agriculture and paths forward. Sustain. Agric. Rev. 2024, 3, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Live to Plant. Techniques to Improve Microbial-Based Biofertilizer Formulations. 2025. Available online: https://livetoplant.com/techniques-to-improve-microbial-based-biofertilizer-formulations/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Van Impe, J.; Smet, C.; Tiwari, B.; Greiner, R.; Ojha, S.; Stulić, V.; Vukušić, T.; Jambrak, A.R. State of the art of nonthermal and thermal processing for inactivation of micro-organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Nepal, J.; Zou, Z.; Munsif, F.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Zaheer, S.; Khan, M.S.; Jadoon, S.A.; Tang, D. Biochar particle size coupled with biofertilizer enhances soil carbon-nitrogen microbial pools and CO2 sequestration in lentil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1114728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, T.; Hou, Y.; Bol, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Yu, N.; Meng, J.; Zou, H.; Wang, J. Review on the effects of biochar amendment on soil microorganisms and enzyme activity. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 2599–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J.T.; Lehmkuhl, B.K.; Chen, L.; Illingworth, M.; Kuo, V.; Muscarella, M.E. Resuscitation-promoting factor (Rpf) terminates dormancy among diverse soil bacteria. mSystems 2025, 10, e0151724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, L.; Mazutti, M.A. Freeze and spray drying technologies to produce solid microbial formulations for sustainable agriculture. Processes 2025, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; De-Bashan, L.E.; Prabhu, S.R.; Hernandez, J.-P. Advances in plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculant technology: Formulations and practical perspectives (1998–2013). Plant Soil 2014, 378, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, P.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Wang, L.; Song, H.; Yang, H.-P.; Zampilli, M.; Bidini, G.; Fantozzi, F. Mechanical aspects and applications of pellets prepared from biomass resources. In Production of Materials from Sustainable Biomass Resources; Fang, Z., Smith, R., Jr., Tian, X.F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibekwe, A.M.; Papiernik, S.K.; Gan, J.; Yates, S.R.; Yang, C.-H.; Crowley, D.E. Impact of fumigants on soil microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3245–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Paredes, C.; Tájmel, D.; Rousk, J. Can moisture affect temperature dependences of microbial growth and respiration? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 108316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Wahid, F.; Adnan, M. (Eds.) Biofertilizers for Sustainable Soil Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.