Abstract

Background: Hypereosinophilia, defined as a peripheral blood eosinophil count greater than 1.5 × 109/L, can arise from allergic, infectious, autoimmune, or malignant conditions. In solid tumors, it is rare and most often linked to mucin-secreting carcinomas, while on extremely rare occasions, it accompanies signet ring cell carcinoma, a highly aggressive form of adenocarcinoma. Case Presentation: A 64-year-old woman presented with dyspnea and hypereosinophilia (2.9 × 109/L). She was admitted with suspected eosinophilic pneumonia, but extensive testing was inconclusive. After bone marrow biopsy, her condition deteriorated; histology revealed metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma. PET/CT showed skeletal metastases without apparent local recurrence, although colonoscopy could not be performed to definitively rule it out. Retrospective review uncovered a 2 mm rectal polyp with signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) removed two years earlier. Peripheral eosinophilia progressively increased from 0.16 × 109/L ten months earlier to a peak of 4.29 × 109/L one month prior to admission. She died four weeks after discharge. Conclusions: To the best of our knowledge, this case represents one of the smallest reported primary colorectal SRCC lesions (2 mm) presenting with disseminated disease and paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia as the first diagnostic clue. Monitoring peripheral blood eosinophil counts may provide additional insight into disease activity and prognosis in solid tumors.

1. Introduction

Hypereosinophilia, defined as a blood eosinophil count (BEC) > 1.5 × 109/L, may result from allergic, infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic conditions. In solid tumors, eosinophilia is rare and often overlooked []. Mucin-producing tumors, such as signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC), have been implicated in eosinophil-driven paraneoplastic syndromes due to their cytokine-secreting potential [,]. SRCC is a rare subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma that accounts for <1% of colorectal carcinoma, with younger age at onset and significantly poorer prognosis [,]. To the best of our knowledge, paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia secondary to colorectal SRCC arising from such a minute lesion has not been reported before. This case illustrates the aggressive potential of colorectal SRCC despite its origin from an extremely small primary lesion.

2. Case Presentation

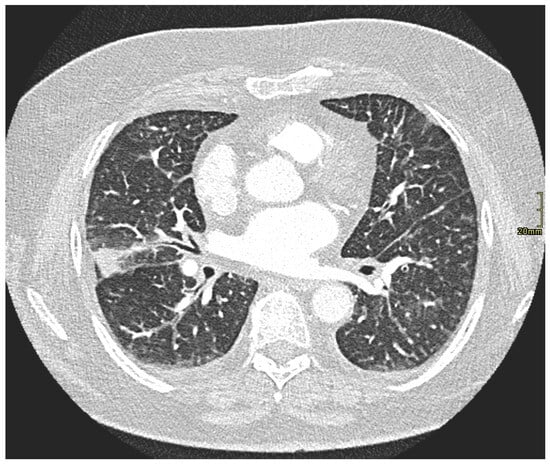

A 64-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and dry cough. Her medical history included untreated asthma, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, and chronic back pain; she had no known allergies or recent medication changes. Laboratory testing showed elevated D-dimer (7800 µg/L—reference < 500 µg/L) and BEC 2.9 × 109/L (reference range 0.02–0.67 × 109/L). CT pulmonary angiography excluded embolism but revealed nonspecific interstitial changes with diffuse thickening of the central peribronchial interstitium, consistent with interstitial pulmonary edema, without ground-glass opacities or fibrosis (Figure 1). She was admitted with suspected eosinophilic pneumonia. Spirometry demonstrated obstructive airflow limitation. FEV1 increased from 1.4 L (57% predicted) to 1.65 L (68% predicted), corresponding to a 250 mL (18%) improvement, consistent with a positive bronchodilator response according to ATS/ERS criteria. Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was 35 ppb, and total IgE was 105 IU/mL. Bronchoalveolar lavage showed mild eosinophilia (4%), below the diagnostic threshold for eosinophilic pneumonia (>25%). A transbronchial lung biopsy was performed, but the sample was suboptimal and demonstrated normal histology, rendering it diagnostically non-representative. CEA was slightly elevated at 7.2 µg/L (reference < 4.2 µg/L). Positive IgG antibodies for Strongyloides and Toxocara were consistent with past exposure; active infection was excluded by negative stool testing. Cardiac ultrasound, troponin, and NT-proBNP were normal. Electromyography was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

CT pulmonary angiography excluded pulmonary embolism and demonstrated interstitial changes consistent with moderate interstitial pulmonary edema (lung window). Given the clinical context and peripheral eosinophilia, eosinophilic interstitial pneumonia was considered more likely than lymphangitic carcinomatosis.

As prior investigations remained inconclusive, bone marrow biopsy was performed, before initiation of corticosteroid therapy. Shortly afterwards, the patient developed respiratory failure and severe low back pain requiring opioids. BEC increased (3.85 × 109/L), LDH was elevated (9.42 µkat/L), and inflammatory markers rose (CRP 330 mg/L, PCT 1.58 µg/L). Chest X-ray was unchanged, and urinalysis was normal.

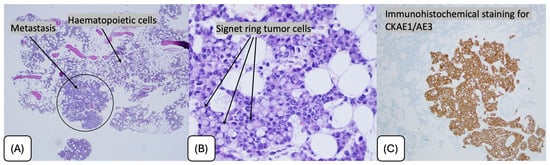

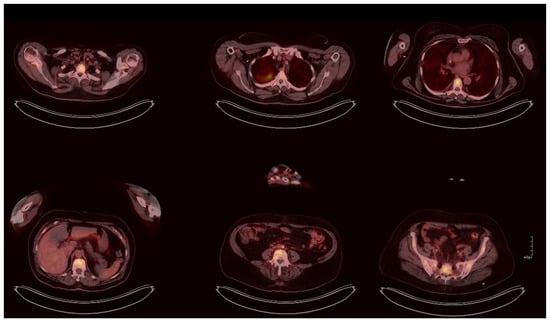

Spinal MRI revealed altered vertebral marrow density without spondylodiscitis. Empiric therapy included ivermectin (200 µg/kg/day for 2 days), albendazole (400 mg twice daily for 5 days), piperacillin/tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 h for 7 days), and systemic corticosteroids (methylprednisolone equivalent of 64 mg/day, tapered thereafter). Histology from bone marrow biopsy confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology and focal marrow infiltration, positive for cytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3) and CDX2 on immunohistochemical staining, consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal origin (Figure 2). Gastroscopy was negative, colonoscopy was not feasible due to clinical instability. PET/CT showed multiple skeletal lesions suspicious for metastases, without evident local recurrence (Figure 3). However, as colonoscopy could not be performed due to the patient’s deterioration, microscopic or mucosal recurrence could not be excluded.

Figure 2.

Bone marrow biopsy showing metastatic infiltration by signet ring cell carcinoma. (A) Low-power view demonstrating focal metastatic deposits within hematopoietic marrow (H&E, ×40). (B) High-power view highlighting signet ring tumor cells with intracytoplasmic mucin displacing the nucleus (H&E, ×400). (C) Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 confirming epithelial origin of the tumor cells.

Figure 3.

PET/CT demonstrating skeletal metastases (SUV 8.2) and metabolically active pulmonary consolidation (SUV 7.1). No abnormal uptake was observed within the gastrointestinal tract; however, given the minute size of the original lesion and the limited sensitivity of PET/CT for mucosal disease, microscopic recurrence cannot be excluded.

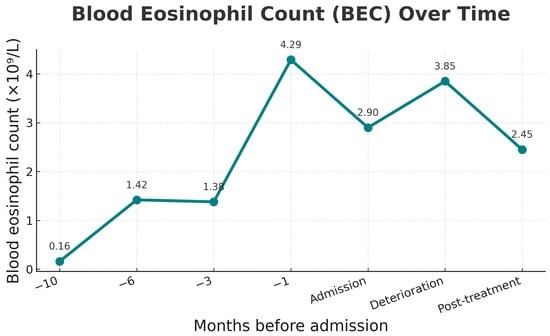

Subsequent thorough review of external records revealed that two years earlier, the patient had undergone colonoscopy for positive fecal occult blood testing in another institution. A rectal polyp had been removed, with histology confirming a 2 mm focus of signet ring cell carcinoma. Multidisciplinary tumor board recommended colectomy, which the patient declined, opting for surveillance with serial colonoscopies, rectal MRI, and tumor markers. All had remained negative until six months prior to admission, when gradual eosinophilia first appeared (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Eosinophil count over time, showing gradual rise before admission, peak at 1 month prior, persistence at deterioration, and decline after methylprednisolone was started at deterioration.

Despite supportive measures, her condition deteriorated. Following corticosteroid initiation, BEC decreased from 3.85 × 109/L to 2.45 × 109/L at discharge. As the patient transitioned to palliative oncology care, no further laboratory follow-up was performed. She died four weeks after discharge. The timeline of clinical events, including polypectomy, onset of eosinophilia, and subsequent metastatic progression, is shown in Figure 5.

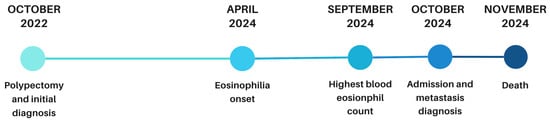

Figure 5.

Timeline of disease progression from polypectomy to eosinophilia onset, metastasis, and death.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates disseminated colorectal SRCC arising from a 2 mm intrapolyp focus that had been completely removed two years earlier. PET/CT showed no signs of local recurrence; however, this modality has limited sensitivity for mucosal disease, and colonoscopy could not be performed due to clinical instability.

Paraneoplastic eosinophilia is usually observed in hematologic malignancies and less frequently in solid tumors such as lung, gastric, and pancreatic carcinomas [], yet remains especially rare in colorectal cancer []. Recent reviews have emphasized that paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia represents a rare but clinically significant manifestation of solid tumors, often associated with advanced disease and poor prognosis [,]

Only isolated reports describe similar findings in other mucin-producing adenocarcinomas. A 2022 case of gastric SRCC with paraneoplastic eosinophilia demonstrated normalization of eosinophil counts after tumor resection, supporting a cytokine-mediated mechanism []. SRCC and other mucin-producing adenocarcinomas can secrete cytokines such as IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF, promoting eosinophil proliferation and activation [,,]. Although cytokine testing could theoretically confirm paraneoplastic origin, it is not routinely available and lacks standardization for diagnostic use [].

In our patient, a biphasic eosinophilic pattern was observed: an initial rise before admission, a spontaneous decline, and a second increase that decreased following corticosteroid therapy. Although this course differed from the more typical pattern reported in the literature—where eosinophil levels decrease after tumor regression or treatment—it may reflect exhaustion of cytokine-driven eosinophil production (e.g., IL-5, GM-CSF) or early bone marrow infiltration at an advanced stage [,]. Similar fluctuations have been described in other solid tumors, including lung adenocarcinoma, where eosinophil levels paralleled disease progression [].

Peripheral eosinophilia in this context may therefore act as an early and dynamic marker of systemic progression. While tissue eosinophilia can reflect a favorable local immune response, persistent peripheral eosinophilia usually indicates tumor aggressiveness driven by sustained cytokine release and chronic inflammation [,]. Comparable findings in pancreatic adenocarcinoma further support unexplained eosinophilia as a potential early clinical marker of malignant transformation [].

This case reinforces the importance of considering paraneoplastic causes in the differential diagnosis of unexplained eosinophilia, particularly when common etiologies have been excluded. A limitation of our report is the lack of serum cytokine measurements and the absence of follow-up colonoscopy to confirm the PET/CT finding of no local recurrence.

4. Conclusions

This case illustrates how paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia may serve as an early indicator of malignant progression, even in the absence of evident local recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, it represents one of the smallest reported primary colorectal SRCC lesions (2 mm) presenting with disseminated disease and paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia as the first diagnostic clue. Monitoring peripheral blood eosinophil counts may provide additional insight into disease activity and prognosis in solid tumors, underscoring the need for continued vigilance during oncologic follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.; investigation, S.R. and P.M.; clinical management of the patient, P.M.; methodology and clinical validation, S.Š. and M.H.; data curation, S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.Š., M.H. and P.M.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, S.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature and the use of fully anonymized patient data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical teams involved in the care of the patient. Special thanks to Biljana Grčar Kuzmanov, Institute of Oncology Ljubljana, Slovenia, for preparing the bone marrow biopsy pathology report and providing the histological images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATS | American Thoracic Society |

| BEC | Blood Eosinophil Count |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ERS | European Respiratory Society |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in 1st second |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| PET/CT | Positron Emission Tomography–Computed Tomography |

| SRCC | Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma |

References

- Shomali, W.; Gotlib, J. World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification of Eosinophilic Disorders: 2024 Update on Diagnosis, Risk Stratification, and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 946–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, A.; Ozawa, H.; Oki, M.; Yanagi, H.; Nabeshima, K.; Nakamura, N. Helicobacter pylori-Negative Advanced Gastric Cancer with Massive Eosinophilia. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Arora, R.; Das, P.; Singh, M.K. Deeply Eosinophilic Cell Variant of Signet-Ring Type of Gastric Carcinoma: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 13, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, T.; George, R.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.; Petrelli, N.J. Primary Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma of the Colon and Rectum. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 1996, 3, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, U.; Zimmermann, A.; Späth, C.; Müller, T.; Maak, M.; Schuster, T.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Käser, S.A.; Michalski, C.W.; Janssen, K.P.; et al. Mucinous and Signet-Ring Cell Colorectal Cancers Differ from Classical Adenocarcinomas in Tumor Biology and Prognosis. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska, E.; Obołończyk, Ł.; Sworczak, K. Hypereosinophilia in Solid Tumors—Case Report and Clinical Review. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 639395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielski, W.; Kupryś-Lipińska, I.; Kumor-Kisielewska, A.; Grząsiak, O.; Borodacz, J.; Niedźwiecki, S.; Hogendorf, P.; Durczyński, A.; Strzelczyk, J.; Majos, A. Peripheral Eosinophil Count May Be the Prognostic Factor for Overall Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Undergoing Surgical Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Saha, A.; Kuykendall, A.; Zhang, L. Clinical and Therapeutic Intervention of Hypereosinophilia in the Era of Molecular Diagnosis. Cancers 2024, 16, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Sui, P.; Han, B. Gastric Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma with Paraneoplastic Eosinophilia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Oncol. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.W.; Cho, M.Y.; Park, C. Expression of Eosinophil Chemotactic Factors in Stomach Cancer. Yonsei Med. J. 1999, 40, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, S.; Rezaei, N. Eosinophils in the Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, N.; Hu, W.; Ge, H.; Xie, S.; Ding, C. Tumor-Associated Eosinophilia in a Patient with EGFR-Positive, MET-Amplified Lung Adenocarcinoma Refractory to Targeted Therapy: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 4988–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ream, S.; Natarajan, P.; Gupta, S.; Sotelo-Rafiq, E.; Schuller, D. Paraneoplastic Hypereosinophilia in Poorly Differentiated Adenocarcinoma of the Lung. Cureus 2023, 15, e34386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Wang, S.; Zhong, K.; Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Chen, W.; Cheng, P. Tumor-Associated Tissue Eosinophilia Predicts Favorable Clinical Outcome in Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.M.; Russeth, T.E.; Thati, N. Hypereosinophilia as a Presenting Sign of Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Rare, Severe Presentation. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e256235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).