Abstract

Metal Injection Molding (MIM) is an established, high-precision manufacturing route for small, geometrically complex metallic components, integrating polymer injection molding with powder metallurgy. State-of-the-art feedstock systems, such as Catamold (polyacetal-based), enable catalytic debinding performed in furnaces operating under ultra-high-purity nitric acid atmospheres (>99.999%). The subsequent thermal stages pre-sintering and sintering are carried out in continuous controlled-atmosphere furnaces or vacuum systems, typically employing inert (N2) or reducing (H2) atmospheres to meet the specific thermodynamic requirements of each alloy. However, incomplete decomposition or secondary volatilization of binder residues can lead to progressive hydrocarbon accumulation within the sinering chamber. These contaminants promote undesirable carburizing atmospheres, which, under austenitizing or intercritical conditions, increase carbon diffusion and generate uncontrolled surface carbon gradients. Such effects alter the microstructural evolution, hardness, wear behavior, and mechanical integrity of MIM steels. Conversely, inadequate dew point control may shift the atmosphere toward oxidizing regimes, resulting in surface decarburization and oxide formation effects that are particularly detrimental in stainless steels, tool steels, and martensitic alloys, where surface chemistry is critical for performance. This review synthesizes current knowledge on atmosphere-induced surface deviations in MIM steels, examining the underlying thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms governing carbon transport, oxidation, and phase evolution. Strategies for atmosphere monitoring, contamination mitigation, and corrective thermal or thermochemical treatments are evaluated. Recommendations are provided to optimize surface substrate interactions and maximize the functional performance and reliability of MIM-processed steel components in demanding engineering applications.

1. Introduction

Metal Injection Molding (MIM) is an established, high-precision manufacturing route for small, geometrically complex metallic components, integrating polymer injection molding with powder metallurgy. State-of-the-art feedstock systems, such as Catamold (polyacetal-based), enable catalytic debinding performed in furnaces operating under ultra-high-purity nitric acid atmospheres (>99.999%). The subsequent thermal stages—pre-sintering and sintering—are carried out in continuous controlled-atmosphere furnaces or vacuum systems, typically employing inert (N2) or reducing (H2) atmospheres to meet the specific thermodynamic requirements of each alloy [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The MIM process has distinguished itself in recent decades for its excellent performance in component applications with complex geometries, high production volume, and reduced mass [1,2,3,4,5]. Variants of the MIM process, such as microMIM, represent an alternative to machining microcast components with subsequent machining or the direct application of micromachining [5,6].

The metallurgical characteristics of the surface and subsurface microstructure of machined or micromachined components are generally homogeneous due to the removal of excess material (overmetals) from micromachined or, primarily, rolled bars [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Catamold is one of the most widely used feedstocks, using polyacetal (CH2O)n as the binder, with debinding carried out chemically and thermally [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Most of the debinding is performed in a furnace or chamber separate from the sintering process, utilizing an atmosphere based on highly concentrated nitric acid (99.999%) at temperatures between 150 and 200 °C. In the debinding stage, a large portion of the polymer is extracted, creating vacancies between the metal powders. However, a portion of the polymer still retains the shape of the components after debinding; these are then sent to another chamber in continuous furnaces or a different furnace for the “pre-sintering and sintering” stages [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. During the pre-sintering stage, the remaining polymers that were not removed are cumulatively extracted in the chamber, which is most often the same as the sintering chamber. Sintering is a heat treatment that generates volumetric shrinkage in components obtained by MIM processes [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Sintering is conducted in controlled-atmosphere or vacuum furnaces, utilizing nitrogen, hydrogen, or nitrogen/hydrogen atmospheres to prevent powder oxidation, depending on the chemical composition of the powder [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Sintering temperatures for low-alloy steels with medium carbon content, such as DIN 42CrMo4, AISI 4140, and AISI 8740, are typically set at 1250 °C using a nitrogen atmosphere. For stainless steels, recommended temperatures vary according to the microstructural class: austenitic grades are sintered at approximately 1380 °C, while martensitic grades exhibit optimal sintering around 1340 °C, both generally processed under hydrogen or argon atmospheres. For precipitation-hardening stainless steels, such as 17 4 PH, the indicated sintering temperature is approximately 1350 °C. The choice of sintering atmosphere is directly related to the thermochemical behavior of each steel class. Nitrogen-based atmospheres are widely employed for low-alloy steels with medium or high carbon content, whereas stainless steels require more reducing atmospheres, predominantly composed of hydrogen. Hydrogen plays a crucial role in preserving the protective Cr2O3 film, reducing its thermal degradation and contributing to the maintenance of low carbon levels within the metallic matrix due to its high reducing potential [1,2,4,5,7].

An important aspect of furnace atmospheres, particularly at the start of production or after extended periods of inactivity, relates to the moisture content present in the system. The dew point is a fundamental thermohygrometric parameter used to characterize the atmosphere applied during sintering in the Metal Injection Molding (MIM) process. It represents the temperature at which the water vapor present in the processing gas reaches saturation and begins to condense. In metallurgical applications, the dew point serves as an indirect indicator of the residual moisture content in the furnace atmosphere, directly influencing the reducing or oxidizing potential of the sintering environment [7,14]. The sintering of stainless steels is highly sensitive to oxidizing species, particularly water vapor. Even trace amounts of moisture can oxidize the protective Cr2O3 film, negatively affecting mass transport, densification, pore formation, and ultimately the corrosion resistance and mechanical performance of MIM-produced components. Therefore, strict control of the dew point is essential to ensure the preservation of metallic phases and the formation of homogeneous microstructures. In industrial practice, atmospheres with a dew point of −40 °C or lower are generally considered suitable for the sintering of stainless steels in hydrogen or argon-hydrogen mixtures [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, for more sensitive alloys, such as ASTM 316/316L and 420, or in systems where furnace tightness cannot be fully guaranteed, the use of atmospheres with a dew point below −60 °C is recommended to maintain strongly reducing conditions throughout the thermal cycle. The comprehensive study of atmosphere control is therefore restricted in scope to the MIM route, which presents distinct advantages over other processes that rely on the powder-binder system. Most notably, the Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (MAM-FDM) route, which is based on layer-by-layer deposition of metal filaments, must be addressed for proper scope justification. Although MAM-FDM also utilizes sintering as a final step, similar to MIM, its layer-by-layer deposition processing route results in distinct microstructures and properties [7,8]. MAM-FDM is predominantly ideal for prototyping and low-volume production, owing to its low tooling costs. In contrast, MIM remains the most economical and efficient solution for high-volume production (typically exceeding 50,000 parts per year) of complex geometries, despite the substantial initial investment required for tooling and molds [16]. Furthermore, the final density and resulting porosity of MAM-FDM components tend to exhibit greater variability than those achieved by MIM, directly impacting critical properties such as hardness and fatigue resistance [16]. This systematic difference in mechanical performance is comprehensively illustrated in Table 1, presented in the discussion section. Based on the superior microstructural control, higher throughput, and established industrial application of MIM for demanding performance components, this review focuses exclusively on the mechanisms of surface engineering and atmosphere-induced deviations inherent to the Metal Injection Molding process. In vacuum sintering systems, dew point control is replaced by monitoring the partial pressure of oxidizing species, maintaining the core principle of minimizing water vapor content. Thus, the establishment of atmospheres with extremely low dew points is essential for the efficient processing of stainless steels via MIM, ensuring chromium preservation, effective oxide reduction, and the achievement of the required physicochemical properties for high-performance applications [7,14]. At the sintering temperature, interstitial diffusion and chemical changes occur on the external surface when the temperature approaches the intercritical region [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. At these temperatures, decarburization and carbon enrichment effects are intensified when using an inadequate atmosphere or due to the deposition of hydrocarbons inside the furnace, depending on the composition and morphology of the powder. The material exhibited a density exceeding 99% of its theoretical value, as determined by pycnometric measurements. [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Dynamic recovery, recrystallization, and grain growth follow atomic diffusion in the solid state during the sintering process. As the temperature increases, thermolysis occurs, assisting in the removal of any remaining polymeric binder material [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The main sintering theories emphasize that two particles in contact at isothermal temperatures generate neck formation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The phenomena associated with neck formation are related to mass and heat transfer. The thermodynamic behavior of the particles generates a static condition in which spherical powders remain stationary during sintering, leading to porosity reduction, and through the preliminary use of the HIP process, 100% density can be achieved [49,50,51,52]. The main atmospheres used in the sintering of steels obtained in the MIM process are nitrogen for low-alloy steels and hydrogen for ferritic, austenitic and precipitation-hardened stainless steels [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. There are variable atmospheres for high nickel alloys [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. In this class of steels, a nitrogen-based atmosphere contributes to obtaining carbon classified as medium and hydrogen to obtaining low carbon in the alloy [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Martensitic stainless steels are sintered with nitrogen [36,37,40]. The use of the right atmosphere for each alloy is fundamental for obtaining the best metallurgical properties for components to be used in the sintered condition or for subsequent thermal and thermochemical treatments [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. This study aims to elucidate the main mechanisms that can have detrimental effects on the surface of steels produced by MIM process during stages involving atmosphere control. It also seeks to identify best practices for sintering, heat treatment, and thermochemical treatment cycles, when such processes are required for the intended application.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of the typical mechanical properties of sintered 17 4 PH stainless steel components produced through the MIM and MAM-FDM routes on the substrate [7,9,11,16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review Methodology

This review was conducted following a structured and systematic approach to identify, select, and critically analyze the scientific literature concerning the effects of sintering atmospheres, heat treatments, and thermochemical processes on steels produced via Metal Injection Molding (MIM). A comprehensive search was carried out across major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, using combinations of keywords such as “Metal Injection Molding,” “stainless steel sintering,” “carbon diffusion,” “dew point,” “porosity in MIM steels,” and “densification behavior.” Inclusion criteria encompassed peer-reviewed journal articles, systematic reviews, technical standards, and specialized books published between 2000 and 2025 in English, with high impact factors. Publications that were not peer-reviewed, duplicated studies, or works exclusively focused on experimental procedures that did not contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the processing-structure-property relationships in MIM steels were excluded. The literature screening followed a three-stage process: initial title evaluation, abstract assessment, and detailed full-text review to ensure relevance, methodological rigor, and alignment with the objectives of the review. Extracted data were systematically organized into thematic categories, including sintering parameters, furnace atmospheres, dew point control, carbon diffusion kinetics, and densification behavior. The collected information was critically compared and synthesized to identify trends, consensus, discrepancies, and research gaps. This methodology provided a rigorous and comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge, offering insights into the key factors that influence the microstructure, properties, and performance of steels fabricated via MIM.

2.2. Basis for Data Analysis and Characterization

The analysis and discussion of property data and microstructural characterization were based on established industrial practices for powder metallurgy components, addressing specific concerns regarding elemental quantification in porous structures. For critical light elements, such as Carbon (C), Oxygen (O), and Nitrogen (N), the primary industry standard for precise quantification is Elemental Analysis by the LECO method, as Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) has known limitations in accurately measuring the content of these light elements in steels. Consequently, the assessment of surface deviations, such as decarburization or carbon enrichment depth, is preferentially determined by measuring Vickers Microhardness (HV) profiles. These profiles provide a robust and quantitative metric of the resulting mechanical property gradient, which is directly dependent on the interstitial carbon content in the affected region, offering a more reliable validation of atmospheric effects than semi-quantitative EDS data. Furthermore, the analysis of optimal processing parameters, including thermal cycles for sintering and post-treatments, as well as the quantitative limits for critical impurities, was conducted using data compiled from specialized MIM handbooks and relevant international standards (e.g., ASTM) to provide authoritative reference values [18].

3. Effects of Sintering Atmospheres, Heat Treatments, and Thermochemical Processes on the Surface Engineering of Catamold Steels

3.1. Thermodynamic Aspects in the Sintering Atmosphere

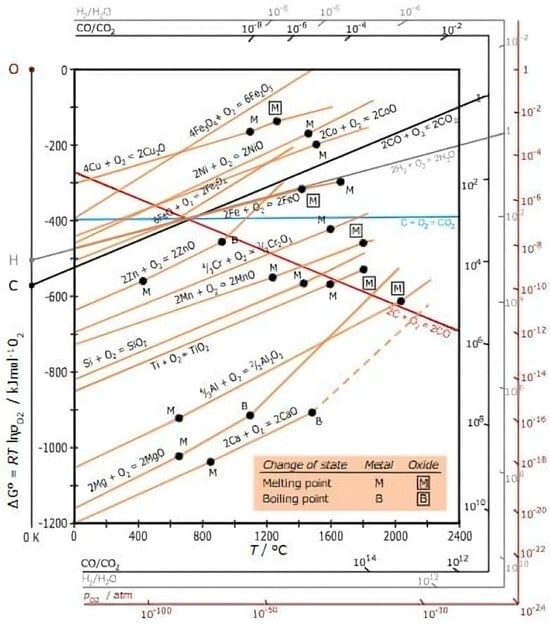

The Ellingham diagram can be very useful in understanding the thermal cycles related to the use of protective atmospheres, especially to determine whether a particular atmosphere is oxidizing, enriching carbon or reducing [19,20,26]. It is important to note that the diagram refers to the equilibrium condition and does not take into account the kinetics of the reactions. It also assumes the presence of sufficient oxidizing species for the reaction to continue [19,20,26]. The Ellingham diagram uses various graphs of the variation in Gibbs energy (ΔG) versus temperature for the formation of an oxide, sulphide, chloride and so on. As enthalpy variation (ΔH) and entropy variation (ΔS) are basically constant with sintering temperature, since there is no phase change, the graph of free energy versus temperature can be drawn as a series of lines, where (ΔS) is the slope and (ΔH) is the intercept on the y-axis. Figure 1 shows the Ellingham diagram, illustrating the Gibbs free energy and the partial pressures.

Figure 1.

The figure shows the Ellingham diagram, illustrating the Gibbs free energy and the partial pressures [19].

The free energy of formation is negative for most metal oxides and is therefore used in the heat treatment of steels. The main applications of Ellingham diagrams in sintering are to determine the reduction of a given metal oxide to the metallic condition. It is also used to determine the partial pressure of oxygen that is in equilibrium with a metal oxide at a given temperature. In relation to atmospheres, it helps to determine the ratio of carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide that will be able to reduce the oxide to metal at a given temperature. Finally, it determines the proportion between hydrogen and water vapor that will be able to reduce the oxide to metal at a given temperature [19,20,26,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. The kinetics of carbon diffusion in steels with high porosity, such as those produced via Metal Injection Molding (MIM), are strongly influenced by the open microstructure and the increased surface area provided by interconnected pores. At elevated sintering temperatures, carbon primarily diffuses through the metallic matrix, but it can also interact with the internal surfaces of the pores, promoting localized carburization processes. The high porosity increases the contact area between the steel and the sintering atmosphere, accelerating surface diffusion of carbon and potentially generating concentration gradients throughout the component [19,20,26]. This effect is particularly relevant in low- and medium-alloy steels, where carbon diffusion is thermodynamically controlled and follows Fick’s laws, with diffusion coefficients dependent on temperature and alloy composition. Furthermore, the presence of interconnected porosity can reduce the effective density of the material, influencing the time required to achieve homogeneous carbon distribution within the matrix. Therefore, the diffusion kinetics are not solely a function of temperature but are also strongly dependent on pore morphology, particle size, component thickness, and local chemical composition, requiring precise control of sintering conditions to optimize the mechanical properties and microstructural uniformity of MIM-fabricated parts [19,20,26].

Furthermore, the final chemical composition of MIM components must be rigorously controlled. Specifically, the critical impurity limits for light elements, such as Oxygen (O), Carbon (C), and Nitrogen (N), must strictly adhere to the specifications defined by relevant international standards, such as those from the ASTM. Exceeding these established limits, even marginally, severely compromises the final densification, mechanical integrity, and corrosion resistance of the component. Quantification of these elements in industrial practice is typically performed via Elemental Analysis (LECO Method), which is recognized as the most accurate standard for porous structures in powder metallurgy, providing the quantitative data necessary for quality assurance [58].

To systematically address the quantitative difference in final properties between Metal Injection Molding (MIM) and Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (MAM-FDM), Table 1 presents a comparative summary of typical mechanical performance metrics for 17 4 PH stainless steel produced by both routes. This data corroborates the superior microstructural control achieved by MIM, particularly regarding density and mechanical strength, thus justifying the focus of this review on the MIM process.

3.2. Summary of Deleterious Aspects

Inadequate surface and subsurface carbon content compromises the metallurgical and mechanical properties of steel [21]. The presence of decarburization in components used in the sintered condition alone significantly reduces the wear resistance of the components [21,22,23,24,25,26]. In low-alloy, medium-carbon steels subjected to quenching followed by tempering, the full recovery of the surface carbon content becomes limited when the depth of the decarburized layer exceeds approximately 0.2 mm. Under these conditions, even with the use of controlled atmosphere furnaces, the applied carbon potential and the austenitizing time may not provide sufficient diffusion to reestablish carbon equilibrium in the affected region. As a result, a microstructural configuration develops consisting of alternating zones with adequate carbon potential, followed by a decarburized region and subsequently another zone with stable potential. This degradation of the surface carbon profile induces residual stress fields—tensile stresses in the decarburized layer and compressive stresses in the adjacent regions which can act as stress concentrators and promote the nucleation of localized microcracks [24,25,26]. The limitation in carbon recovery during conventional austenitizing cycles prior to quenching is primarily due to the short holding times at the austenitizing temperature. Under such reduced dwell times, the diffusion kinetics of carbon at these temperatures are not sufficiently rapid to homogenize the chemical composition at depths greater than approximately 0.2 mm. Consequently, the restoration of carbon within the decarburized layer remains incomplete, even under controlled-atmosphere conditions [21,26].

When the decarburization is deeper, a carbon recovery cycle is recommended. This can be carried out at the conventional austenitizing tempering temperature with lower interstitial diffusion kinetics or at a higher temperature with a threshold of 930 °C for diffusion without austenitic grain growth. It is not recommended to directly quench components with deep carbon recovery at high temperatures, as there is a risk of cracking. It is recommended that the austenizing temperature be reduced to the specified range for each material and maintained for sufficient time for homogeneous hardening or normalization of the material with subsequent austenitization for tempering and tempering. In general, the tempering temperatures of low alloy and medium carbon steels obtained by the MIM process are lower than those obtained by conventional processes. The main phenomenon linked to the deposition of hydrocarbons in the sintering chamber is related to the carbon enrichment of the components. As with decarburization, this enrichment can be superficial, subsurface or deep (depending on the sintering time). Because the feedstock residues are hydrocarbons, they generate a carbon-enriching atmosphere, which is enhanced by the inherent characteristics of materials at high sintering temperatures with high porosity [21,22,23,24,25,26].

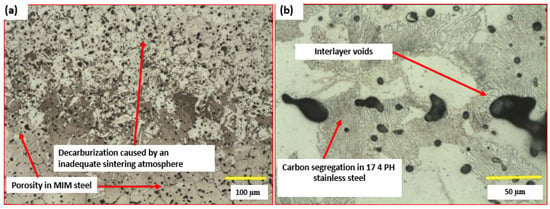

This condition favors the diffusion of interstitial carbon in these steels. In medium carbon and low alloy steels, the carbon content tends to reduce elongation when used in the sintered condition and to have greater wear resistance and higher surface microhardness, making it more difficult to go through the steps of reaming, qualifying holes and small machining operations when the geometries make it difficult to obtain all the dimensions and elements of the parts. When the steel being processed is low carbon and medium alloy, such as 8620, the presence of carbon enrichment can lead to surface and core uniformity in the range of 0.4 to 0.6%, values which are much higher than those stipulated for this class of steel (in the range of 0.2%). This condition directly hinders the thermochemical treatments of carburizing or carbonitriding. These steels will have difficulties diffusing carbon and will not form homogeneous layer depths and components with very small dimensions and low masses will show high embrittlement. One of the most critical aspects is the presence of carburizing elements in the sintering atmosphere of martensitic, austenitic, ferritic, duplex and precipitation-hardened stainless steels [37,40,43]. High values of these elements cause severe unbalancing of the alloys. This condition leads to a drastic reduction in corrosion resistance and, in some cases, in the biocompatibility of steels used in biomedical applications, such as 316L and 17 4 PH [7,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,46,47,48]. Figure 2a shows decarburization near the surface of a medium-carbon steel produced by the MIM process, whereas Figure 2b presents surface segregation in stainless steel fabricated by metal additive manufacturing.

Figure 2.

(a) Surface decarburization observed in low-alloy MIM steel after sintering. (b) Carbon segregation due to an inadequate sintering atmosphere in 17 4 PH stainless steel produced by additive manufacturing.

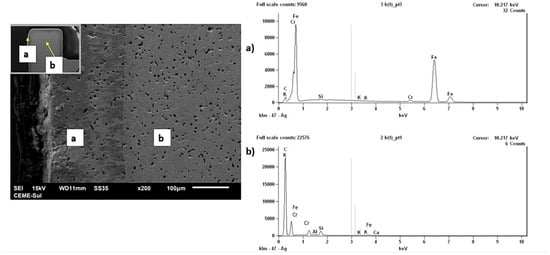

Alternatives to this condition can be the application of new sintering in a hydrogen atmosphere, obtaining dew point values suitable for reducing the carbon diffused in the samples. At the end of the processes, whether or not solution heat treatment is applied to dissolve carbides in austenitic stainless steels, solution treatment followed by aging in precipitation-hardened steels, and quenching and tempering in martensitic steels, passivation must be performed to form a homogeneous Cr2O3 layer [7,8,9]. The adjustment of carbon content on the surface and in the core is of great importance for the tribological quality, residual stresses, corrosion resistance, and microhardness of components produced by the MIM process. The 17 4 PH MMM stainless steel with superficial carbon enrichment can be observed in Figure 3. This condition is identified by the variation in the microstructure and by the EDS microprobe peaks between region (a), near the surface, and (b), in the substrate. The EDS microprobe data are qualitative and semi-quantitative.

Figure 3.

17 4 PH MIM stainless steel with superficial carbon enrichment, evidenced by the microstructure variation and by the EDS microprobe peaks in regions (a) near the surface and (b) in the substrate. The EDS data are qualitative and semi-quantitative.

3.3. Accumulation of Polyacetal Residues in the Sintering Chamber

During the sintering process of low alloy steels with a nitrogen atmosphere, the associated thermodynamic reactions do not favor the elimination of residues [3,26,28,35,43]. These residues gasify, generating a partially carbonaceous atmosphere at high sintering temperatures of between 1280 °C and 1380 °C, depending on the alloy processed [44]. As the sintering temperatures are high, the carbon shows interstitial diffusion behavior, causing surface and subsurface changes in the steels due to carbon enrichment. This enrichment can have catastrophic consequences in low alloy and medium carbon steels or stainless steels when used in the simply sintered condition [44]. In low alloy and medium carbon steels (42CrMo4), there can be a drastic reduction in surface elongation. In the case of precipitation-hardened (17 4 PH) or martensitic (420) stainless steels, there can be a drastic reduction in corrosion resistance, a reduction in biocompatibility and difficulty in obtaining micro-hardness in 17 4 PH steels. In martensitic stainless steels, corrosion resistance is also compromised and resistance to tempering can be detected [7,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,45,46,47]. The main mechanisms identified for these phenomena are associated with the interstitial diffusion of carbon, which leads to the degradation of the Cr2O3 layer at elevated temperatures [17,46,47,48]. Another factor linked to the presence of unsuitable atmospheres in stainless steels is the reduction in biocompatibility, as well as the occurrence of sensitization and intergranular corrosion during the subsequent cooling stage after sintering [7,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,46,47,48].

In addition to carbon enrichment, another undesirable condition, especially in low-alloy and medium carbon steels such as 42CrMo4, is decarburization. This can occur when the dew point is inadequate during the sintering process [46,47,48,49,50,51].

3.4. Reducing Atmosphere

The primary atmospheres used during the sintering of components produced by MIM process are selected based on the type of steel being sintered [1,2,3,4,5]. For steels that develop passivated surface layers, hydrogen is the most commonly used reducing atmosphere. The formation of surface oxides such as Cr2O3 in stainless steels is closely influenced by the sintering atmosphere, as are other factors like grain refinement hardening, alloying element behavior, and work hardening mechanisms [46,47,48]. For austenitic and precipitation-hardened stainless steels, a hydrogen-based reducing atmosphere is strongly recommended. It helps preserve the integrity of the surface oxide layer while maintaining low carbon levels—this applies to both standard 316 and the low-carbon 316L grades [35,40,45]. It ensures a consistently low carbon content, preventing carbon segregation that could hinder solution heat treatment and aging processes. High-nickel steels can also benefit from a reducing atmosphere when a low carbon content is required before subsequent carburizing or carbonitriding treatments [46]. Moreover, hydrogen significantly enhances the corrosion resistance of stainless steels [40,45]. Periodic application of a hydrogen atmosphere is also useful for partially removing excess hydrocarbon deposits from the furnace, which could otherwise create an unsuitable sintering environment. However, hydrogen atmospheres have some drawbacks, including high flammability, the requirement for high purity, and the risk of volatilization of certain alloying elements [35,40,45].

3.5. Nitrogen Protective Atmosphere

A nitrogen protective atmosphere is the most widely used environment for sintering low-alloy steels, martensitic stainless steels, and medium-carbon steels in Metal Injection Molding (MIM) processes [1,2,3,4,5]. It is particularly important for achieving the desired hardenability in steels such as 420 (martensitic stainless), as well as 8740, 42CrMo4, 100Cr6, and other similar grades. Compared to hydrogen, nitrogen offers several advantages: it is more cost-effective, non-flammable, and provides moderate corrosion resistance. However, when used for austenitic or precipitation-hardened stainless steels, nitrogen atmospheres tend to promote carbon accumulation on the surface. This buildup can increase the risk of sensitization and intergranular corrosion during or after processing [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Nitrogen atmospheres are exothermic in nature, meaning they release heat during sintering [1,2,3,4,5]. One consequence of this environment is a tendency toward surface carbon enrichment. If not properly controlled, this can negatively impact the mechanical properties of the final component, leading to reduced elongation and increased susceptibility to embrittlement [1,2,3,4,5].

3.6. Partially Reducing Atmosphere

Up to 40% hydrogen. In this configuration, the environment acquires partial reducing properties, suitable for certain sintering applications [1,2,3,4,5]. Under these conditions, precise control of the dew point is critical to ensure consistent results and to prevent unwanted oxidation or carbon-related defects during sintering [1,2,3,4,5]. The MIM process has been characterized over the past decades by numerous advances and the high quality of its products [1,2,3,4,5]. This statement is directly related to the control of chemical composition and microstructure throughout its manufacturing and finishing stages [1,2,3,4,5]. Aspects such as porosity level, presence of segregations, and microstructural uniformity. These aspects can be assessed using a carbon sensor, optical emission spectrometry on components with larger inspection areas, and optical microscopy. To determine the morphology of precipitates and obtain semi-quantitative and qualitative data, techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and EDS microprobe can be used. For mechanical property testing, the main technique is Vickers microhardness testing, according to MDP standards [6,10,46,47].

3.7. Inert Atmosphere with Argon

The primary inert atmosphere used for sintering is argon. However, in the Metal Injection Molding (MIM) process, the use of pure argon is not common practice [51,52,53,54,55]. Instead, small amounts of hydrogen are typically added to the argon atmosphere. This combination helps minimize gas retention and reduces the volatility of alloying elements during sintering [51,52,53,54,55]. While pure argon has limited effectiveness in reducing oxidation, this limitation can be overcome by introducing small concentrations of hydrogen [51,52,53,54,55]. This mixed atmosphere is suitable for both ferrous and non-ferrous alloys that exhibit corrosion resistance through the formation of passivating surface oxides such as stainless steels (Cr2O3) and titanium (TiO2) [51,52,53,54,55].

3.8. Low-Pressure Vacuum Atmosphere

The use of low-pressure vacuum represents an excellent alternative for carbon control during the sintering process, as it provides a low oxygen potential. Low-pressure vacuum sintering is characterized by a thermal cycle conducted under reduced pressure, typically in the range of 10−3 to 102 mbar [45,48]. This condition can be applied to promote the densification of steel. The conditions for neck formation and diffusion kinetics can also be influenced by residual hydrocarbons or by the materials used in the sintering chamber. The use of graphite furnaces may, over time, generate carbon sources with high interstitial diffusion potential due to the elevated temperatures within the austenitic or intercritical region [51,52,53,54,55]. To minimize this effect, the use of molybdenum chambers is recommended, along with periodic mechanical cleaning and the introduction of a reducing gas, such as hydrogen. During low-pressure vacuum sintering, heat promotes solid-state diffusion and pore reduction, resulting in high material density. In many cases, the controlled injection of inert or reducing gases, such as argon or hydrogen, at suitable pressures is employed to improve atmosphere control and enhance the surface characteristics of MIM steels.

3.9. Heat and Thermochemical Treatment Atmospheres Applied to Catamold Steels Produced by MIM

Regarding the heat and thermochemical treatments applied to Catamold steels produced by Metal Injection Molding (MIM) there are numerous parameters and correlations that still require investigation. For low-alloy or high-alloy non-stainless steels, carbon recovery heat treatment is a valuable approach for maintaining both metallurgical and mechanical properties in the surface and core regions [51,52,53,54,55,56]. In cases of surface decarburization or harmful carbon enrichment, these effects can be corrected by applying a controlled carbon potential specific to each steel grade, thereby restoring the carbon balance.

To guide the implementation of these corrective measures, specific quantitative thermal cycles and process parameters are required. For instance, the carbon recovery cycle for medium-carbon, low-alloy steels (e.g., 4140, 42CrMo4, and 8740) is typically conducted through austenitization at 870 °C for 3 h, maintaining a precise carbon potential of 0.4%. Similarly, for hypereutectoid steels (e.g., 100Cr6), the cycle is set at 840 °C for 3 h with a higher carbon potential of 1%. The selection of these specific temperatures and holding times is critical, as detailed by the Handbook of Metal Injection Molding, to ensure complete carbon restoration without inducing abnormal austenitic grain growth or cracking during subsequent quenching and tempering cycles.

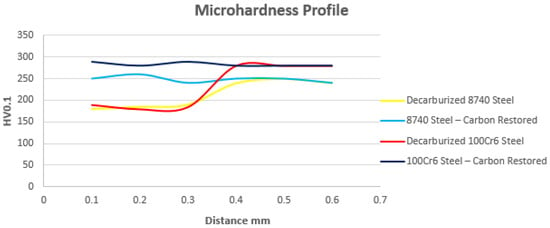

Steels such as 4140, 42CrMo4, and 8740 can undergo a carbon recovery cycle through austenitization at 870 °C for 3 h, with a carbon potential of 0.4%. This treatment enables complete restoration of the surface layer while maintaining the original conditions of the substrate. Subsequently, MIM-fabricated components can be subjected to quenching and tempering, achieving the specified mechanical properties [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. For hypereutectoid steels such as 100Cr6, austenitizing should be conducted at 840 °C for 3 h under a carbon potential of 1%, followed by quenching and tempering to achieve the specified final properties [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. In cases where the decarburization depth exceeds acceptable limits, the empirical rule of 1 h per 0.1 mm of carbon restoration may be applied. Conversely, when surface carbon enrichment occurs instead of decarburization, the austenitizing temperature and carbon potential remain unchanged, and homogenization between the surface and the substrate proceeds over time according to thermodynamic equilibrium and Fick’s diffusion law [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. In Figure 4, the behavior of decarburized Catamold 8740 and 100Cr6 steels can be observed after sintering and carbon restoration in a bath-type furnace under controlled atmospheres of 0.4% and 1%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Surface decarburization was observed in low-alloy MIM steel after sintering and subsequent carbon restoration.

Low-carbon steels such as 8620 and FN02 or FN08, when sintered under hydrogen, can be carburized or carbonitrided in gaseous or liquid atmospheres, followed by quenching and tempering. It is worth noting that FN02 and FN08 steels sintered in hydrogen generally exhibit low core microhardness, whereas 8620 sintered in nitrogen typically presents core microhardness values between 300 and 380 HV0.1 [52,53,54,55,56,57]. The temperature used for these cycles is generally the same as the austenitizing temperature prior to quenching, with an extended holding time to allow carbon diffusion or reduction at the surface.

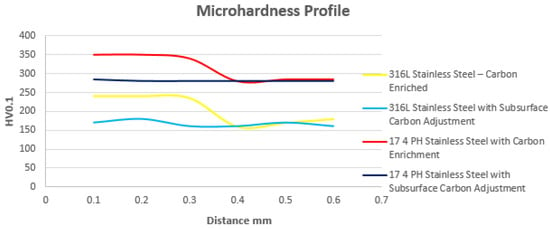

For martensitic stainless steels, the temperature commonly employed to mitigate surface anomalies caused by deleterious carbon enrichment during sintering is 950 °C, using a hydrogen atmosphere, followed by quenching and tempering. For precipitation-hardening stainless steels such as 17 4 PH, the recommended treatment temperature is 1040 °C, also under a hydrogen atmosphere, followed by quenching and artificial aging. In the case of austenitic stainless steels, such as 316L, solution treatment is performed at 1040 °C in a hydrogen atmosphere, followed by rapid water quenching to ensure complete dissolution of carbides. In Figure 5, the austenitic stainless steel Catamold 316L and the precipitation-hardened stainless steel Catamold 17 4 PH are shown with surface carbon enrichment, highlighting the effect of the reducing atmosphere on the final carbon adjustment between the surface and the substrate.

Figure 5.

Microhardness behavior of austenitic and precipitation-hardened stainless steels following carbon equilibration between the surface and core under a reducing atmosphere.

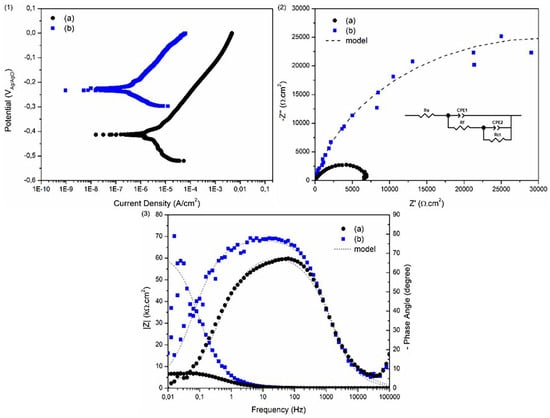

The use of inappropriate atmospheres is critical for sintered stainless steels [58]. The potentiodynamic polarization curves shown in Figure 6 illustrate the deleterious effects of unsuitable atmospheres on the corrosion resistance of Catamold 17 4 PH steel. The conditions depicted in Figure 6 can be mitigated by performing a new sintering cycle under a hydrogen atmosphere for either austenitic or 17 4 PH stainless steels [58]. The use of a hydrogen atmosphere can contribute to improvements in corrosion resistance superior to those observed with a nitrogen atmosphere [58].

Figure 6.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves (1), Nyquist plots (2), and Bode plots (3) for samples sintered with water vapor-based contaminants (a) and pure nitrogen (b) [57].

The use of a hydrogen atmosphere can contribute to improvements in corrosion resistance superior to those detected with a nitrogen atmosphere [57]. Because the austenitizing temperature is not excessively high, abnormal austenitic grain growth is minimized, resulting in a desirable final microstructure [49,50,51,52]. Controlling the cooling kinetics after sintering is of fundamental importance. In steels with high hardenability, post-sintering machining operations—such as drilling or dimensional calibration—can be challenging. In such cases, subcritical annealing cycles can be employed, especially for martensitic stainless steels (Catamold 420) or precipitation-hardening grades (Catamold 17 4 PH) [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. For precipitation-hardened steels produced by either MIM, it is possible to control the sintering and cooling stages to promote an initial solution treatment. Under these conditions, the cooling rate must be carefully controlled, followed by conventional aging cycles. This approach can be applied to Catamold 17 4 PH and Maraging 300 steels [51,52]. In gas, liquid, or plasma nitriding, Catamold steels containing nitride-forming elements such as Cr, Al, V, Mo, and Nb develop well-defined compound and diffusion layers. Some studies have explored the relationship between porosity levels and nitrogen diffusion kinetics, though results remain inconclusive. Generally, decarburization during carburizing or carbonitriding of MIM steels is mitigated by the high carbon potentials used in these processes, while for nitriding and oxinitrocarburizing, decarburization is undesirable. After carburizing or carbonitriding followed by quenching and tempering, Catamold steels exhibit increased wear resistance, higher surface microhardness, and improved fatigue life [51]. Similarly, thermochemical treatments such as nitriding and oxinitriding yield comparable mechanical improvements, with the added benefit of enhanced corrosion resistance [51]. Overall, the surface condition after sintering plays a crucial role in determining the mechanical and metallurgical properties of this class of steels.

Appendix A presents supplementary information relating sintering and thermal and thermochemical treatments to the Metal Injection Molding and Metal Additive Manufacturing techniques.

4. Final Considerations

A significant body of literature addresses sintering, heat treatment, and thermochemical atmospheres applied to Catamold steels used in the MIM process. This review provides a comprehensive assessment of all processing stages and their effects on surface engineering, systematically integrating comparisons with the Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing (MAM-FDM) route to justify the MIM process as the dominant technology for high-performance, high-volume metallic components. Based on the synthesis of current research trends, experimental evidence, and the identified performance gaps, this work outlines the key mechanisms governing surface integrity in MIM steels and establishes strategic research directions aimed at optimizing contamination control, diffusion behavior, and the efficiency of post-treatment processes.

- Atmosphere Control and Porosity: The use of appropriate sintering atmospheres is paramount for improving surface and substrate homogeneity in MIM steels. However, a significant gap remains in the quantitative understanding of how specific atmosphere compositions—including the critical O, C, and N impurity levels (monitored via LECO method)—interact with the inherent microstructural porosity to precisely influence final mechanical performance.

- Contamination and Cr2O3 Degradation: Periodic cleaning of sintering chambers is necessary to prevent undesirable atmospheres, which lead to superficial carbon enrichment in low-alloy steels or degradation of the Cr2O3 protective layer in stainless steels. Despite these established recommendations, standardized, industry-wide protocols for atmosphere monitoring and maintenance are still lacking, representing a major gap in industrial practice.

- Modeling and Process Optimization: Corrective treatments, such as carbon recovery using controlled-atmosphere furnaces or hydrogen-based sintering for stainless steels, are effective. Yet, integrated predictive models for carbon diffusion and potential adjustment in porous MIM components remain critically underdeveloped, thereby limiting comprehensive process optimization and control.

- Impact on Performance: Inadequate atmospheres significantly affect porosity volume, surface finish, wear resistance, corrosion resistance, fatigue life, and biocompatibility in biomedical alloys, underscoring the critical need for real-time atmosphere monitoring and control throughout the thermal cycle.

- Post-Processing: Thermochemical treatments such as carburizing, quenching, and tempering are effective for low-carbon steels produced via MIM, while nitriding and oxinitrocarburizing enhance properties. Nonetheless, systematic studies correlating specific process parameters (e.g., quantitative cycles detailed in Section 3.9) with long-term performance are scarce for high-alloy and stainless steels.

5. Future Research Roadmap

To advance the field of surface engineering in MIM steels, future research should be strategically focused on the following areas:

- Development of Predictive Digital Models: Prioritize the creation of integrated predictive models that link sintering atmosphere composition, O, C, N impurity levels, porosity morphology, and carbon diffusion kinetics to the final mechanical and corrosion properties.

- Real-Time Monitoring and Standardization: Establish standardized testing and monitoring protocols for atmosphere control. This includes developing and validating in situ, real-time atmosphere sensing technologies that can automatically adjust process parameters to mitigate contamination effects.

- Advanced Post-Treatment Studies: Conduct systematic, quantitative studies correlating parameters of advanced post-treatment processes (e.g., nitriding, oxinitrocarburizing, or carbon recovery cycles) with the long-term performance and fatigue life of different classes of MIM steels, especially high alloy and biomedical grades.

- Interface Engineering: Investigate the fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms at the interface between the MIM porous structure and the processing atmosphere, aiming to develop new alloy compositions or pre-treatments that are intrinsically more resistant to surface deviations.

These efforts will support the optimization of current MIM processes and enable the development of high-performance, reliable components for emerging applications, including the biomedical, aerospace, and high-fatigue-demand environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.B.M.; methodology, J.L.B.M.; software, J.L.B.M.; validation, J.L.B.M., formal analysis, J.L.B.M.; investigation, J.L.B.M., C.O.D.M. and L.V.B.; resources, J.L.B.M.; data curation, J.L.B.M.; writing, review and editing, J.L.B.M., C.O.D.M. and L.V.B.; supervision, J.L.B.M.; project administration, J.L.B.M.; funding acquisition, J.L.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel-Brazil (CAPES).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank CAPES, CNPQ and FAPERGS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In general, the equipment used for sintering components produced by Metal Injection Molding (MIM) can also be applied to Additive Manufacturing using metal filaments (MAM) with catalytic debinding. This is possible even though the polymeric binders in this technique are different, yet still catalytic [6,7,8]. The Ultrafuse 316L and Ultrafuse 17 4 PH metal filaments represent well-established solutions for producing complex and dimensionally precise metallic components via Material Extrusion (MEX/FFF) [6,7,8]. Both materials are metal-polymer composites containing over 90% by mass of finely atomized metal powder dispersed in an organic matrix. This matrix is specifically designed to ensure printability, robust green part stability, and controlled binder removal during debinding and sintering. For Ultrafuse 316L, Polyoxymethylene (POM) acts as the primary binder, enabling catalytic debinding under an acidic atmosphere, while Polypropylene (PP) functions as a backbone binder, providing dimensional stability to the green part [6,7,8]. The formulation also includes plasticizers, such as dioctyl phthalate (DOP) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP), as well as zinc oxide (ZnO) as a thermal stabilizer. This composition ensures suitable rheological behavior and controlled transitions between the printing, debinding, and sintering stages, resulting in dense parts with mechanical properties comparable to those obtained via conventional powder metallurgy [6,7,8]. Ultrafuse 17 4 PH utilizes a binder system analogous to 316L; however, the key distinction lies in the metallic powder itself. While 316L is austenitic, 17 4 PH is martensitic and precipitation-hardenable, which mandates an additional post-sintering heat treatment to form intermetallic precipitates responsible for increased strength, hardness, and thermal stability. The processing of both filaments follows the classical powder metallurgy sequence adapted for MAM: printing the green part, catalytic and thermal binder removal, high-temperature sintering, and, in the case of 17 4 PH, the final aging treatment [6,7,8]. This entire process enables the production of metallic components with refined microstructure and robust mechanical properties, representing a cost-effective and technically competitive alternative to conventional powder bed fusion methods. Importantly, these alloys generally do not generate significant carbon enrichment in the sintering chamber, as the process typically employs reducing atmospheres free of excess hydrocarbons, thereby minimizing contamination and preserving the material’s intended properties. Consequently, the precautions to be applied to these materials, as well as to future materials to be developed via MEX/FFF, are similar to those established for steels in the MIM process. It is highlighted that the temperatures proposed for the carbon-recovery and carbon-potential adjustment processes should be taken as operational reference values. Nevertheless, the treatment durations may be shortened or extended in accordance with the severity and type of nonconformity detected in the component.

References

- Kuo, C.-C.; Farooqui, A.; Tasi, C.-X.; Pan, X.-Y.; Huang, S.-H. Revolutionizing metal powder injection molding: A cost-effective approach to tooling innovation. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 150, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.U.; Khor, C.Y.; Zailani, Z.A. Optimization of process parameters in metal injection molding for turbine blade using response surface methodology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 5899–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledniczky, G.; Ronkay, F.; Hansághy, P.; Weltsch, Z. Impact of recycling on polymer binder integrity in metal injection molding. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, F.; Lu, R.; Lu, X. Strength-ductility synergy strategy of Ti6Al4V alloy fabricated by metal injection molding. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2025, 32, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Li, L. The process, microstructure, and mechanical properties of hybrid manufacturing for steel injection mold components. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 57, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.L.B.; Biehl, L.V.; Baierle, I.C. Analysis of fatigue life after application of compressive microstresses on the surface of components manufactured by metal injection molding. Surfaces 2025, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzyński, M.; Płatek, P.; Cedro, P.; Gunputh, U.; Wood, P.; Rusinek, A. Mechanical behavior of 3D-printed zig-zag honeycomb structures made of BASF Ultrafuse 316L. Materials 2024, 17, 6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davids, A.; Apfelbacher, L.; Hitzler, L.; Krempaszky, C. Microstructure and Properties of the Fusion Zone in Steel-Cast Iron Composite Castings. In Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzderland, 2022; pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedziora, S.; Decker, T.; Museyibov, E.; Morbach, J.; Hohmann, S.; Huwer, A.; Wahl, M. Strength properties of 316L and 17 4 PH stainless steel produced with additive manufacturing. Materials 2022, 15, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, M.J.; Medeiros, J.L.B.; de Souza, J.; Martins, C.O.D.; Biehl, L.V. Aluminium injection mould behaviour using additive manufacturing and surface engineering. Materials 2025, 18, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.; Lavecchia, F.; Guerra, M.G.; Galantucci, L.M. Influence of aging treatments on 17 4 PH stainless steel parts realized using material extrusion additive manufacturing technologies. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Caminero, M.A.; García-Plaza, E.; Núñez, P.J.; Chacón, J.M.; Rodríguez, G.P.; Cañadilla, A.; Martínez, J.L. Mechanical and metrological characterisation of 17-4PH stainless steel structures processed by material extrusion additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoz, T.T.; Burgess, A.; Ahuir-Torres, J.I.; Kotadia, H.R.; Tammas-Williams, S. The effect of surface finish and post-processing on mechanical properties of 17 4 PH stainless steel produced by the atomic diffusion additive manufacturing process (ADAM). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 4053–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.; Chemkhi, M.; Boussel, J.; Strub, M.; Alhussein, A. Enhancing surface integrity and fatigue behavior of additively manufactured 17-4PH stainless steel via mechanical post-treatments. Mater. Charact. 2025, 223, 114941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.; Guerra, M.G.; Lavecchia, F. Shrinkage evaluation and geometric accuracy assessment on 17 4 PH samples made by material extrusion additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 109, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Leu, M.C. Additive manufacturing: Technology, applications and research needs. Front. Mech. Eng. 2013, 8, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.; Jeon, E.S.; Moon, S.K.; Park, S.J. Fabrication of 17-4PH stainless steel by metal material extrusion: Effects of process parameters and heat treatment on physical properties. Mater. Des. 2024, 248, 113471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Joens, C.J. Debinding and Sintering of Metal Injection Molding (MIM) Components. In Handbook of Metal Injection Molding, 2nd ed; Miles, R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 129–171. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.N.; Furlan, K.P.; Schroeder, R.M.; Hammes, G.; Binder, C.; Neto, J.B.R.; Probst, S.H.; de Mello, J.D.B. Thermodynamic aspects during the processing of sintered materials. Powder Technol. 2015, 271, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, I.U.; Lager, D.; Hohenauer, W.; Gierl, C.; Danninger, H. Finite element sintering analysis of metal injection molded copper brown body using thermo-physical data and kinetics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 53, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Liu, M.; He, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, X.; An, C. Investigation of decarburization behaviour during the sintering of metal injection moulded 420 stainless steel. Metals 2020, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Lou, J.; He, H.; Wu, C.; Huang, Y.; Su, N.; Li, S. Effects of carbon content on the properties of novel nitrogen-free austenitic stainless steel with high hardness prepared via metal injection molding. Metals 2023, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Chen, S.; Yang, L.; Wei, G. Research progress on injection technology in converter steelmaking process. Metals 2022, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadbeck, P.; Strauß, A.; Weißgärber, T. Decarburization and gas formation during sintering of alloyed PM steel components. Met. Mater. Trans. B 2024, 55, 4352–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamwa, L.D.; Vitry, V.; Malingraux, M.; Lhenry-Robert, L. Practical approach for characterizing the projection of stainless-steel droplets: Vacuum decarburization plant. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; He, S. Thermodynamic and experimental study on CO2 injection in RH decarburization process of ultra-low carbon steel. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 50, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, K.-R.; Choi, S.-H.; Kwon, Y.-S.; Park, D.-W.; Cho, K.-K.; Ahn, I.-S. Study on the sintering behavior and microstructure development of the powder injection molded T42 high-speed steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2011, 17, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simchi, A.; Petzoldt, F. Cosintering of powder injection molding parts made from ultrafine WC-Co and 316L stainless steel powders for fabrication of novel composite structures. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 41, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hou, H.; Tan, Z.; Lee, K. Metal injection molding of pure molybdenum. Adv. Powder Technol. 2009, 20, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, G.; Levenfeld, B.; Várez, A. Effect of residual carbon on the microstructure evolution during the sintering of M2 HSS parts shaping by metal injection moulding process. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 534, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, K.K.; Date, P.P.; Kotwal, G.N.; Nayak, K.C.; Srivatsan, T.S. Influence of sintering on mechanical response of metal injection moulded parts. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2022, 38, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergül, E.; Gülsoy, H.Ö.; Günay, V. Effect of sintering parameters on mechanical properties of injection moulded Ti-6Al-4V alloys. Powder Met. 2013, 52, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadiuk, S.; Loboda, P.; Soloviova, T.; Trosnikova, I.; Karasevska, O. Optimization of the sintering parameters for materials manufactured by powder injection molding. Sov. Powder Met. Met. Ceram. 2020, 59, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, P.; Koseski, R.P.; German, R.M. Microstructural evolution of injection molded gas- and water-atomized 316L stainless steel powder during sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 402, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lv, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; E, S.; Wang, L. Shear Strength Enhancement of Injection-Molded Metal-Polymer Composite Joints Using Z-Pins Manufactured Through Fused Filament Fabrication. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2026, 33, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.-J.; Ha, T.K.; Ahn, S.; Chang, Y.W. Powder injection molding of a 17 4 PH stainless steel and the effect of sintering temperature on its microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Mech. Work. Technol. 2002, 130, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, J.M.; Hidalgo, J. Metal Injection Molding (MIM) of Stainless Steel. In Handbook of Metal Injection Molding, 2nd ed.; Heaney, D.F., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, C.V.; Patel, G.C.M.; Ramesh, M.R.; Desai, V.; Kumar, S. Analysis and Optimization of Metal Injection Moulding Process. In Materials Forming, Machining and Post Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourandish, M.; Godlinski, D.; Simchi, A.; Firouzdor, V. Sintering of biocompatible P/M Co–Cr–Mo alloy (F-75) for fabrication of porosity-graded composite structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 472, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourandish, M.; Simchi, A. Study the sintering behavior of nanocrystalline 3Y-TZP/430L stainless-steel composite layers for co-powder injection molding. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Cooney, R.P. Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; Kutz, M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, UK, 2018; pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, A.; Schuh, C.A.; Tobia, J.C.; Tuncer, N.; Mykulowycz, N.M.; Preston, A.; Barbati, A.C.; Kernan, B.; Gibson, M.A.; Krause, D.; et al. Traditional and additive manufacturing of a new tungsten heavy alloy alternative. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 73, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-W.; Huang, Z.-K.; Tseng, C.-F.; Hwang, K.-S. Microstructures, mechanical properties, and fracture behaviors of metal-injection molded 17-4PH stainless steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2015, 21, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T. Carbon potential control in MIM sintering furnace atmospheres. Met. Powder Rep. 2014, 69, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Shen, B.-C.; Chang, S.-H.; Muhtadin, M.; Tsai, J.-T. Microstructures evolution and properties of titanium vacuum sintering on metal injection molding 316 stainless steel via dip coating process. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Joshi, K.; Patil, B. Comparative economic analysis of injection-moulded component with conventional and conformal cooling channels. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2022, 103, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.L.B.; Biehl, L.V.; Martins, C.O.D.; Pacheco, D.A.d.J.; de Souza, J.; Reguly, A. Assessment of residual stress behavior and material properties in steels produced via oxynitrocarburized metal injection molding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 7596–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Ji, Z.; Ren, S.; Qu, X. UNS S32707 hyper-duplex stainless steel processed by powder injection molding and supersolidus liquid-phase sintering in nitrogen sintering atmosphere. Vacuum 2021, 184, 109910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Kang, Y.; Tian, X.; Ding, J.; Li, D. Material extrusion 3D printing of polyether ether ketone in vacuum environment: Heat dissipation mechanism and performance. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 62, 103390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Neves, E.C.; do Nascimento, E.G.; Sacilotto, D.G.; Ferreira, J.Z.; Medeiros, J.L.B.; Biehl, L.V.; de Jesus Pacheco, D.A. Nondestructive analysis of corrosion in ageing hardened AA6351 aluminium alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 291, 126664–126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochetto, R.; Tochetto, R.; Biehl, L.V.; Medeiros, J.L.B.; Santos, J.C.D.; Souza, J.D. Evaluation of the space holders technique applied in powder metallurgy process in the use of titanium as biomaterial. Latin Am. Appl. Res. 2019, 49, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, B.C.; Gupta, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Jaisal, A.K.; Ranjan, A.K.; Srivastava, A.; Chaudhary, P. Effect of heat treatment on properties and microstructure of steels. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, S.; Acarer, M. The effect of heat treatment on high temperature mechanical properties of microalloyed medium carbon steel. Mater. Des. 2006, 27, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfahany, A.N.; Saghafian, H.; Borhani, G. The effect of heat treatment on mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 3931–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Mondal, D.K.; Maity, J. Effect of cyclic heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of 0.6 wt% carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 4001–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, K.; Lorraine, C.; Salgado, G.; Taylor, A.; Ogren, J.; Umin, P.; Es-Said, O.S. Effects of heat treatments on steels for bearing applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2007, 16, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, T.; Ågren, J. The Carbon Potential During the Heat Treatment of Steel. In The SGTE Casebook: Thermodynamics at Work, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellaro, O.R.; Medeiros, J.L.B.; Uva, G.P.; Carreno, N.L.V.; Maron, G.K.; Biehl, L.V.; Alano, J.H. Corrosion behavior of 17—4PH steel, produced by the MIM process, sintered in different atmospheres. Materia 2024, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Hayat, M.D. Feedstock Technology for Reactive Metal Injection Molding: Process, Design, and Application; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Falah, E.N.; Pratiwi, V.M.; Adityawan, I.; Safrida, N.; Wikandari, E.; Widiyanto, A.R.; Abdullah, R. Research progress, potentials, and challenges of copper composite for metal injection moulding feedstock. Powder Technol. 2024, 440, 119785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Goulas, C.; Ya, W.; Hermans, M.J.M. A high-strength and ductile titanium alloy fabricated by metal injection molding. Metals 2019, 9, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.