Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials Based on Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles and Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials

2.2. Characterization of Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural, Morphological and Chemical Characterization of CFNs

3.2. Structural, Morphological and Chemical Characterization of MPHMs

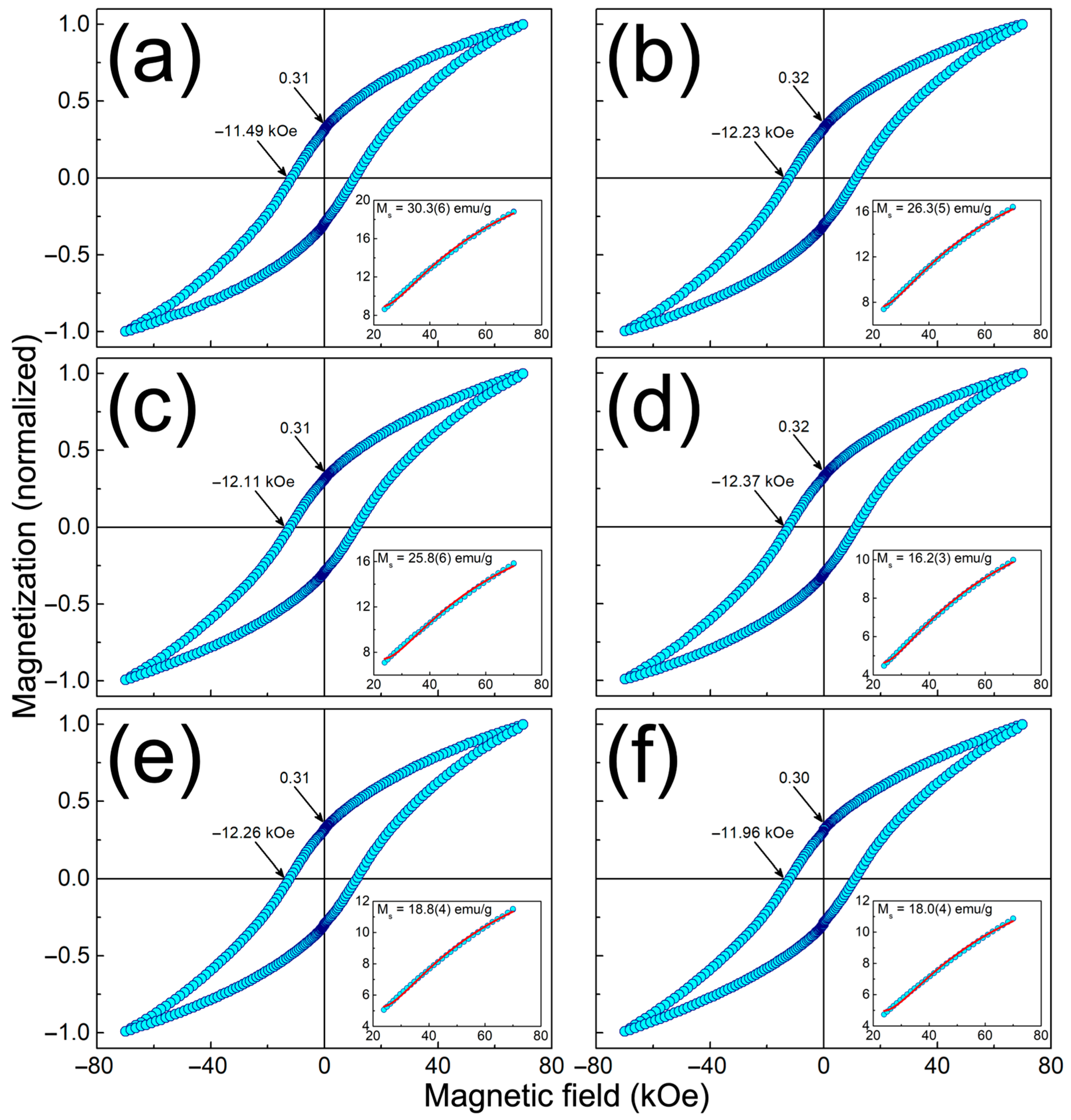

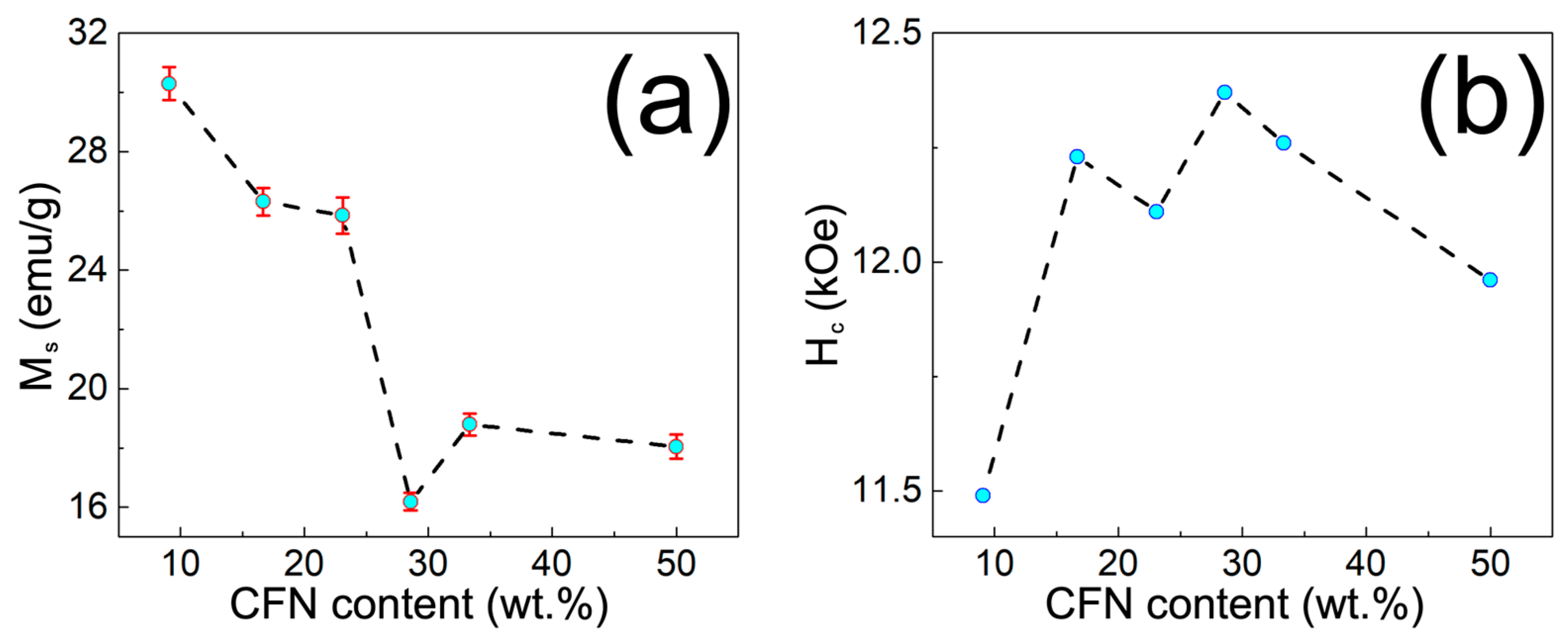

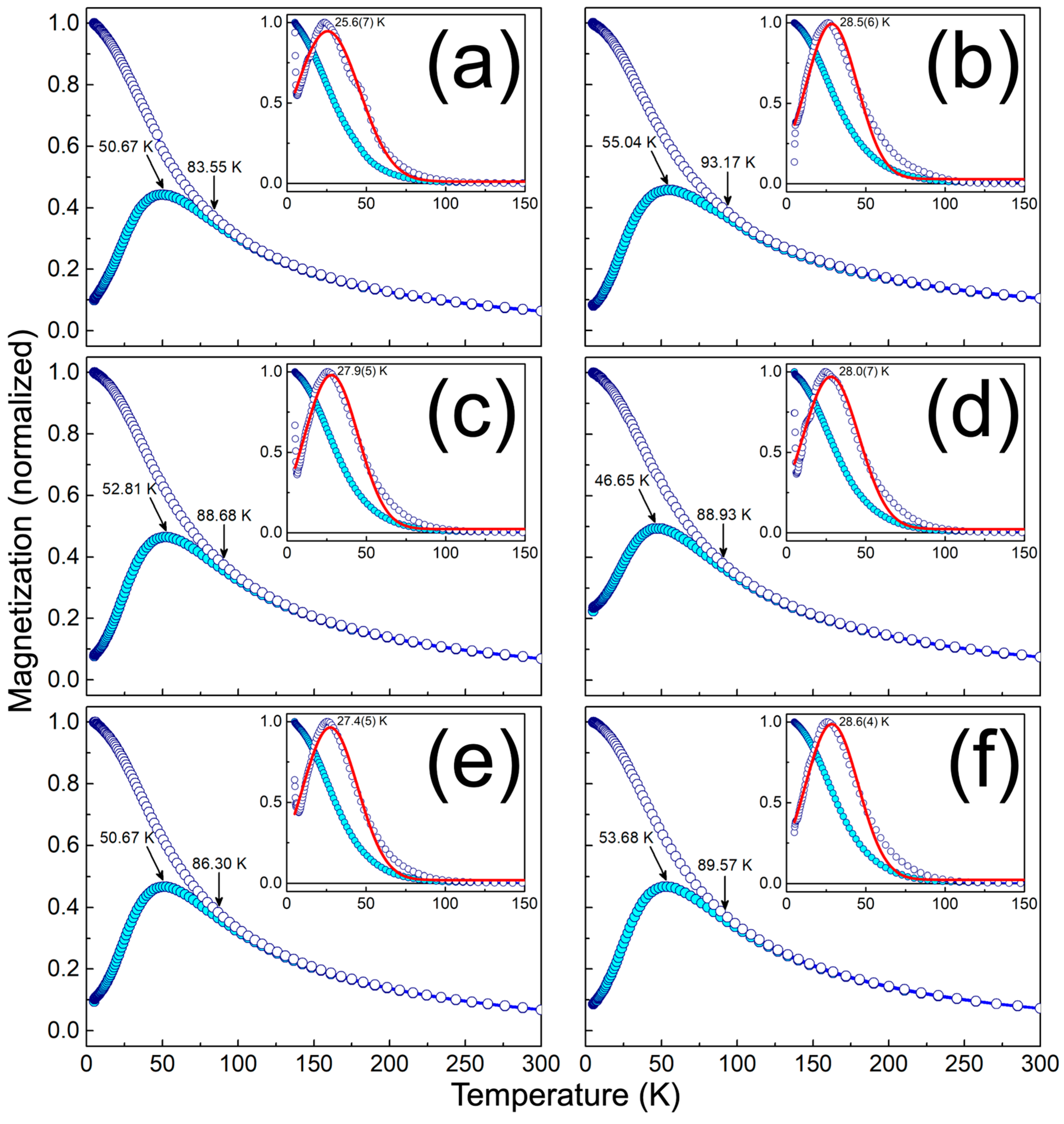

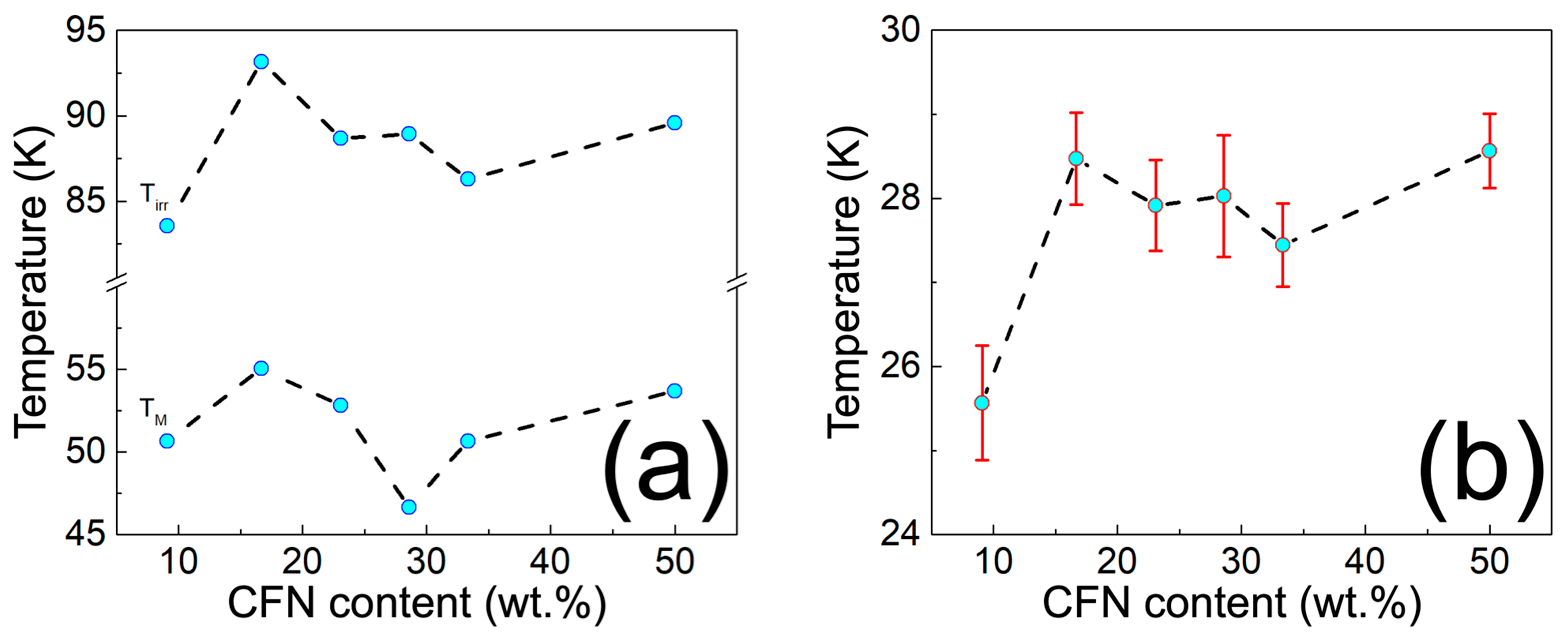

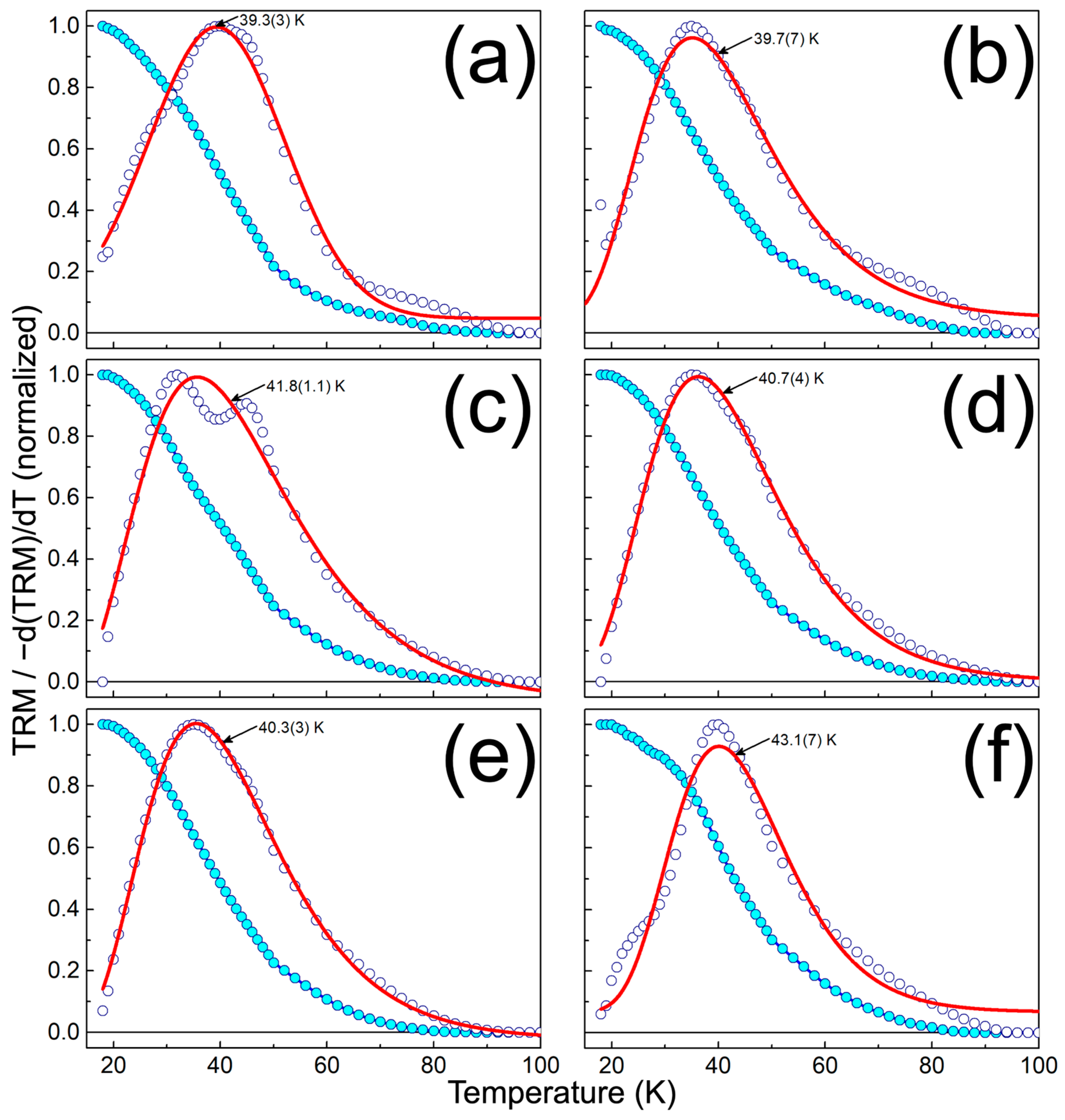

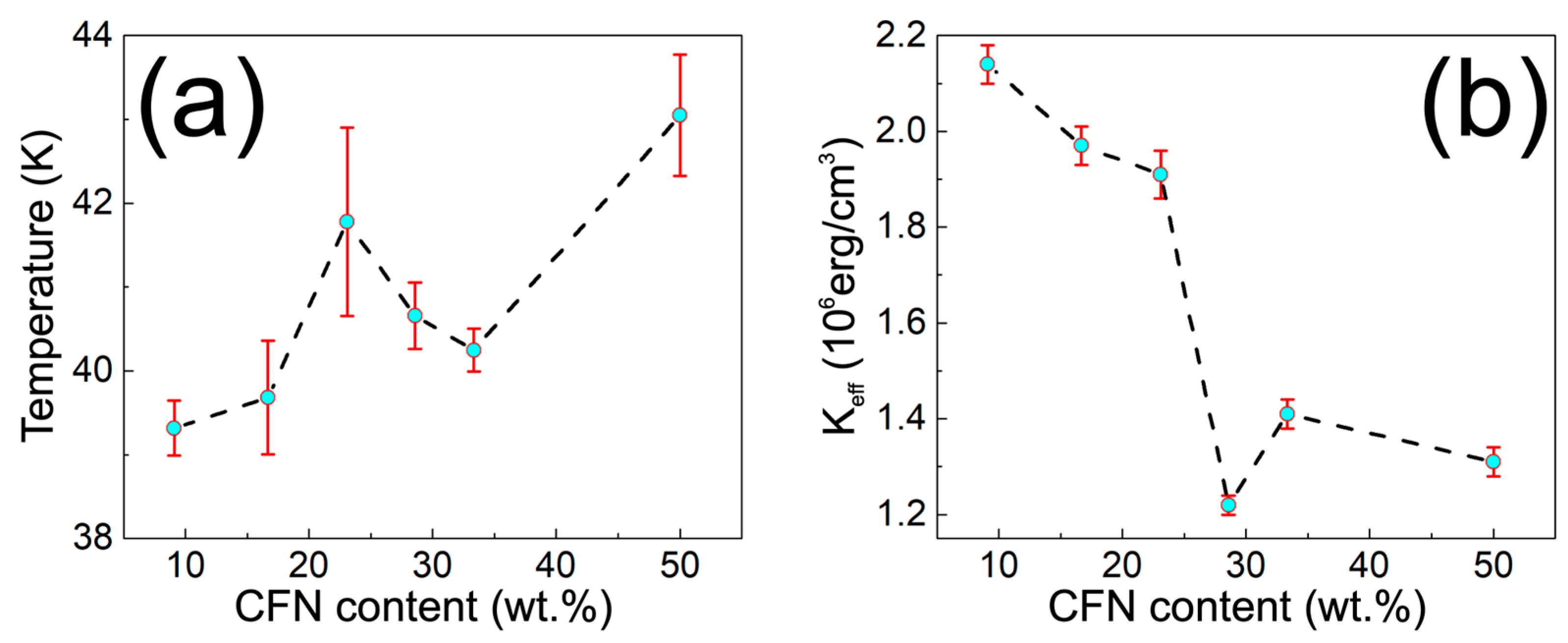

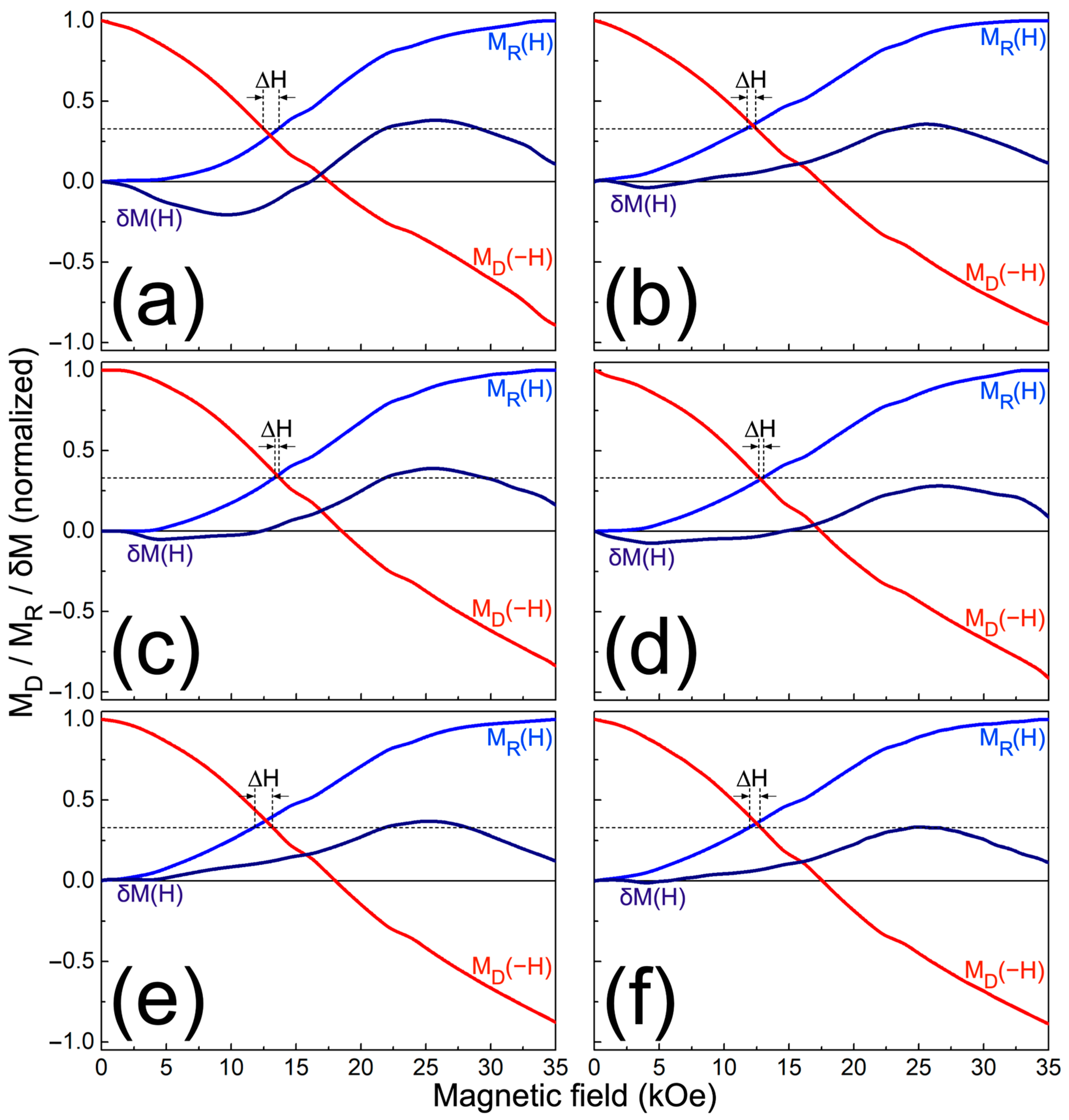

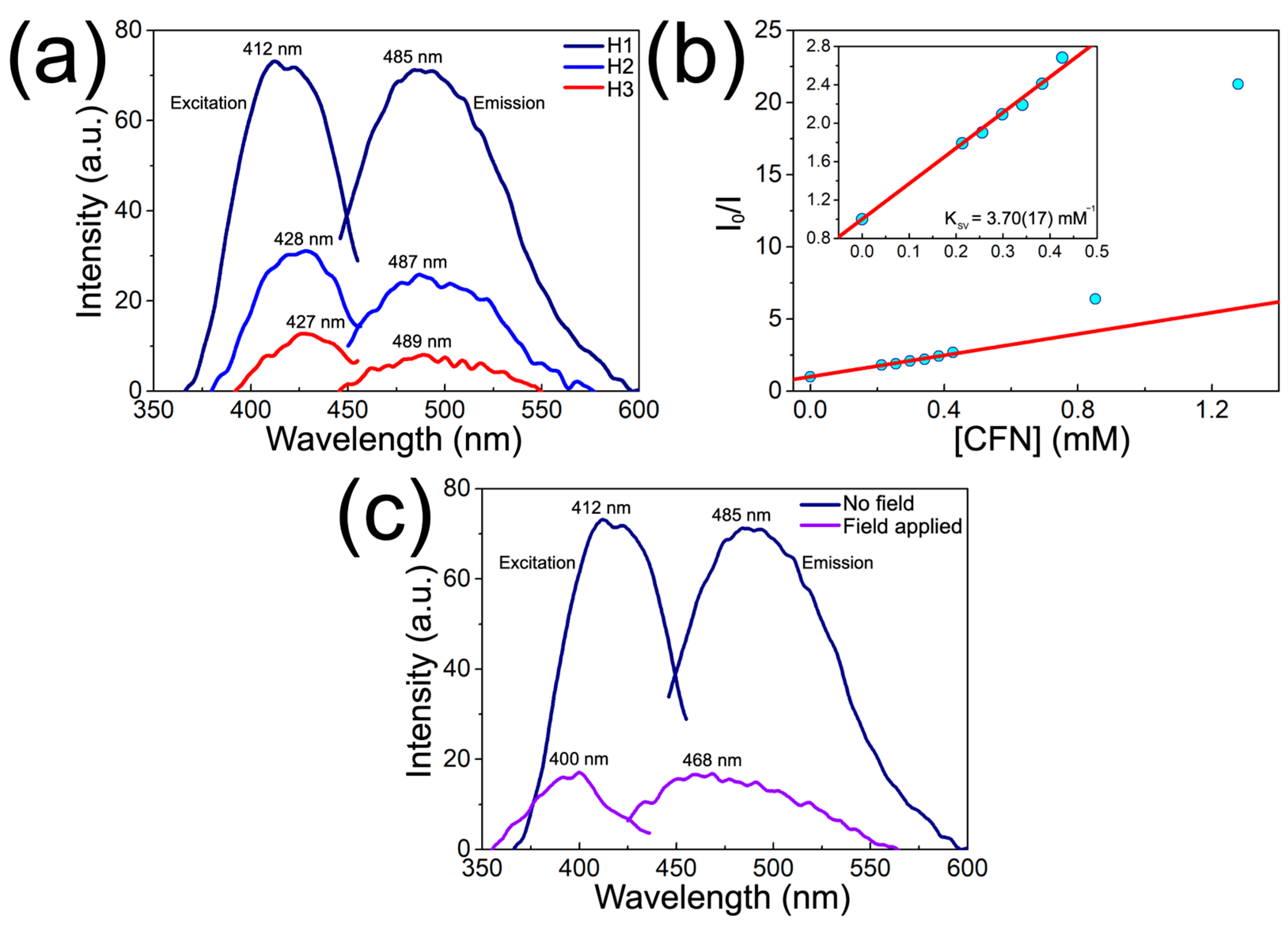

3.3. Physical Characterization of MPHMs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPHMs | Magneto-photoluminescent hybrid materials |

| CFNs | Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles |

| PT2U | Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one) |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| BF | Bright field |

| SAED | Selected area electron diffraction |

| HAADF-STEM | High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| LS | Luminescence spectroscopy |

| TRM | Thermoremanence |

| IRM | Isothermal remanent magnetization |

| DCD | Direct current demagnetization |

| CI95 | 95% confidence interval |

| ZFC | Zero-field-cooled |

| FC | Field-cooled |

| AIE | Aggregation-induced emission |

References

- Miao, J.; Liu, A.; Wu, L.; Yu, M.; Wei, W.; Liu, S. Magnetic ferroferric oxide and polydopamine molecularly imprinted polymer nanocomposites based electrochemical impedance sensor for the selective separation and sensitive determination of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1095, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Fierro, D.; Bustamante-Torres, M.; Bravo-Plascencia, F.; Magaña, H.; Bucio, E. Polymer-magnetic semiconductor nanocomposites for industrial electronic applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostruszka, R.; Půlpánová, D.; Pluháček, T.; Tomanec, O.; Novák, P.; Jirák, D.; Šišková, K. Facile one-pot green synthesis of magneto-luminescent bimetallic nanocomposites with potential as dual imaging agent. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Fard-Fini, S.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Safardoust-Hojaghan, H. Hydrothermal green synthesis and photocatalytic activity of magnetic CoFe2O4–carbon quantum dots nanocomposite by turmeric precursor. J Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 16205–16214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, L.S.; Khan, L.U.; Franqui, L.S.; Delite, F.D.S.; Muraca, D.; Martinez, D.S.T.; Knobel, M. Hybrid magneto-luminescent iron oxide nanocubes functionalized with europium complexes: Synthesis, hemolytic properties and protein corona formation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Pathak, S.; Jain, K.; Singh, A.; Kuldeep; Basheed, G.A.; Pant, R.P. Low-temperature large-scale hydrothermal synthesis of optically active PEG-200 capped single domain MnFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 904, 163992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ganguly, S.; Margel, S.; Gedanken, A. Tailor made magnetic nanolights: Fabrication to cancer theranostics applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 6762–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Min, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.K. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic–luminescent Fe3O4–CdSe core–shell nanocrystals. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2019, 15, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaz, M.; Haque, A.; Cornelison, D.M.; Wanekaya, A.; Delong, R.; Ghosh, K. Magneto-luminescent zinc/iron oxide core-shell nanoparticles with tunable magnetic properties. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2020, 123, 114090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Rubio, I.; Barón, A.; Luis-Lizarraga, O.; Rodrigo, I.; de Muro, I.G.; Orue, I.; Martínez-Martínez, V.; Castellanos-Rubio, A.; López-Arbeloa, F.; Insausti, M. Efficient magneto-luminescent nanosystems based on rhodamine-loaded magnetite nanoparticles with optimized heating power and ideal thermosensitive fluorescence. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 50033–50044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, D.; Xiong, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, Q. Synthesis and morphological control of biocompatible fluorescent/magnetic Janus nanoparticles based on the self-assembly of fluorescent polyurethane and Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Polymers 2019, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Qu, H.; Zheng, X.; Wintermark, M.; Liu, Z.; Rao, J. Janus iron oxides @ semiconducting polymer nanoparticle tracer for cell tracking by magnetic particle imaging. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Vergara, V.A.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; González-González, V.A.; López-Cuellar, E.; Estrada-de la Vega, A. Interactions between magnetic and luminescent phases in hybrid nanomaterials composed of magnetite nanoparticles assembled within a cross-conjugated polymer. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 313, 117901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zeng, H.; Robinson, D.B.; Raoux, S.; Rice, P.M.; Wang, S.X.; Li, G. Monodisperse MFe2O4 (M = Fe, Co, Mn) nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.T.; Dung, N.T.; Tung, L.D.; Thanh, C.T.; Quy, O.K.; Chuc, N.V.; Maenosono, S.; Thanh, N.T.K. Synthesis of magnetic cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with controlled morphology, monodispersity and composition: The influence of solvent, surfactant, reductant and synthetic conditions. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 19596–19610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahhouti, Z.; El Moussaoui, H.; Mahfoud, T.; Hamedoun, M.; El Marssi, M.; Lahmar, A.; El Kenz, A.; Benyoussef, A. Chemical synthesis and magnetic properties of monodisperse cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 14913–14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, H.A. The Choice of a Class Interval. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1926, 21, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, F.H.; Coaquira, J.A.H.; Villegas-Lelovsky, L.; da Silva, S.W.; Cesar, D.F.; Nagamine, L.C.C.M.; Cohen, R.; Menéndez-Proupin, E.; Morais, P.C. Evolution of the doping regimes in the Al-doped SnO2 nanoparticles prepared by a polymer precursor method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 095301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R. An Introduction to Error Analysis, 2nd ed.; University Science Books: Melville, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cevallos, V.J.; Briceño, S.; Solorzano, G.; Gardener, J.; Debut, A.; Dávalos, R.; Bramer-Escamilla, W.; González, G. Electrospun polyvinylpyrrolidone fibers with cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. Carbon Trends 2025, 19, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, S.; Reinoso, C. CoFe2O4-chitosan-graphene nanocomposite for glyphosate removal. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantharamaiah, P.N.; Joy, P.A. Enhancing the strain sensitivity of CoFe2O4 at low magnetic fields without affecting the magnetostriction coefficient by substitution of small amounts of Mg for Fe. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 10516–10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Sharma, A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Mali, S.S.; Hong, C.K.; Shirage, P.M. Morphology-controlled synthesis and enhanced energy product (BH)max of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 15793–15802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 72–108. [Google Scholar]

- Peddis, D.; Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Ardu, A.; Orrù, F.; Fiorani, D.; Laureti, S.; Rinaldi, D.; Muscas, G.; Concas, G.; et al. Beyond the effect of particle size: Influence of CoFe2O4 nanoparticle arrangements on magnetic properties. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coey, J.M.D. Noncollinear spin arrangement in ultrafine ferrimagnetic crystallites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1971, 27, 1140–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, R.H.; Berkowitz, A.E.; McNiff, E.J., Jr.; Foner, S. Surface spin disorder in NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Nunes, A.C.; Majkrzak, C.F.; Berkowitz, A.E. Polarized neutron study of the magnetization density distribution within a CoFe2O4 colloidal particle II. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1995, 145, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, X.; Labarta, A. Finite-size effects in fine particles: Magnetic and transport properties. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2002, 35, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, R.H. Magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 200, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-de la Vega, A.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; Durán-Guerrero, J.G.; Moreno-Cortez, I.E.; Lucio-Porto, R.; González-González, V. Tailoring the magnetic properties of cobalt-ferrite nanoclusters. J. Nanopart. Res. 2016, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianciola, B.N.; Lima, E.; Troiani, H.E.; Nagamine, L.C.C.M.; Cohen, R.; Zysler, R.D. Size and surface effects in the magnetic order of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 377, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.F., Jr. Theory of the approach to magnetic saturation. Phys. Rev. 1940, 58, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrish, A.H. The Physical Principles of Magnetism, 1st ed.; Reprint; IEEE Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 394–396. [Google Scholar]

- Sanna Angotzi, M.; Mameli, V.; Zákutná, D.; Kubániová, D.; Cara, C.; Cannas, C. Evolution of the magnetic and structural properties with the chemical composition in oleate-capped MnxCo1–xFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 20626–20638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddis, D.; Mansilla, M.V.; Mørup, S.; Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Piccaluga, G.; D’Orazio, F.; Lucari, F.; Fiorani, D. Spin-canting and magnetic anisotropy in ultrasmall CoFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 8507–8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddis, D.; Orrù, F.; Ardu, A.; Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Piccaluga, G. Interparticle interactions and magnetic anisotropy in cobalt ferrite nanoparticles: Influence of molecular coating. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mørup, S.; Hansen, M.F.; Frandsen, C. Magnetic interactions between nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2010, 1, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M.; Pereira, C.; Silva, A.S.; Schmool, D.S.; Freire, C.; Grenche, J.M.; Arajo, J.P. Unravelling the effect of interparticle interactions and surface spin canting in γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 superparamagnetic nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 114319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosiniewicz-Szablewska, E.; Figueiredo, L.C.; da Silva, A.O.; Sousa, M.H.; Morais, P.C. Magnetic studies of ultrafine CoFe2O4 nanoparticles with different molecular surface coatings. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 3296–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie-Pelecky, D.L.; Rieke, R.D. Magnetic properties of nanostructured materials. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bianco, L.; Fiorani, D.; Testa, A.M.; Bonetti, E.; Savini, L.; Signoretti, S. Magnetothermal behavior of a nanoscale Fe/Fe oxide granular system. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 174418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, M.; Socolovsky, L.M.; Vargas, J.M. Propiedades magnéticas y de transporte de sistemas nanocristalinos: Conceptos básicos y aplicaciones a sistemas reales. Rev. Mex. Fis. E 2004, 50, 8–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Piccaluga, G.; Fiorani, D.; Peddis, D.; Rasmussen, H.K.; Mørup, S. Magnetic properties of cobalt ferrite–silica nanocomposites prepared by a sol-gel autocombustion technique. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 164714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantrell, R.W.; El-Hilo, M.; O’Grady, K. Spin-glass behavior in a fine particle system. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1991, 27, 3570–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinone, A.J.; Samia, A.C.S.; Zhang, Z.J. Superparamagnetic relaxation and magnetic anisotropy energy distribution in CoFe2O4 spinel ferrite nanocrystallites. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 6876–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneller, E.F.; Luborsky, F.E. Particle size dependence of coercivity and remanence of single-domain particles. J. Appl. Phys. 1963, 34, 656–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Otero, J.; García-Bastida, A.J.; Rivas, J. Influence of temperature on the coercive field of non-interacting fine magnetic particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1998, 189, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, A.; Basini, A.M.; Capolupo, L.; Innocenti, C.; Corti, M.; Cobianchi, M.; Orsini, F.; Guerrini, A.; Sangregorio, C.; Lascialfari, A. Optimized PAMAM coated magnetic nanoparticles for simultaneous hyperthermic treatment and contrast enhanced MRI diagnosis. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 44104–44111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, E.P. Relations between different modes of acquisition of the remanent magnetization of ferromagnetic particles. J. Appl. Phys. 1958, 29, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.E.; O’Grady, K.; Mayo, P.L.; Chantrell, R.W. Switching mechanisms in cobalt-phosphorus thin films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1989, 25, 3881–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddis, D.; Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Piccaluga, G. Magnetism in nanoparticles: Beyond the effect of particle size. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 7822–7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Mantecón, M.; O’Grady, K. Interaction and size effects in magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 296, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geshev, J.; Mikhov, M.; Schmidt, J.E. Remanent magnetization plots of fine particles with competing cubic and uniaxial anisotropies. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 85, 7321–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, E.; Martínez-Huerta, J.M.; Piraux, L.; Encinas, A. Quantification of the interaction field in arrays of magnetic nanowires from the remanence curves. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3981–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ramos, N.; Ibarra, L.E.; Serrano-Torres, M.; Yagüe, B.; Caverzán, M.D.; Chesta, C.A.; Palacios, R.E.; López-Larrubia, P. Iron oxide incorporated conjugated polymer nanoparticles for simultaneous use in magnetic resonance and fluorescent imaging of brain tumors. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, P.; Green, M.; Bowers, A.; Parker, D.; Varma, G.; Kallumadil, M.; Hughes, M.; Warley, A.; Brain, A.; Botnar, R. Magnetic conjugated polymer nanoparticles as bimodal imaging agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9833–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, S.A.; Rakovich, Y.P.; Gun’Ko, Y.K. Multifunctional magnetic-fluorescent nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, M.H. The centenary of the Stern-Volmer equation of fluorescence quenching: From the single line plot to the SV quenching map. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2020, 42, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, W.R.; Contino, P.B. Fluorescence quenching studies: Analysis of nonlinear Stern-Volmer data. In Methods in Enzymology, 1st ed.; Brand, L., Johnson, M.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 210, pp. 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Zappas, A.; Bunz, U.; Thio, Y.S.; Bucknall, D.G. Fluorescence quenching of a poly(para-phenylene ethynylenes) by C60 fullerenes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 249, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, A.S.; Parui, R.; Garai, R.; Chanu, M.A.; Iyer, P.K. Dual “static and dynamic” fluorescence quenching mechanisms based detection of TNT via a cationic conjugated polymer. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Liu, B.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission: Fundamental understanding and future developments. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | PT2U (mg) | CFN (mg) | PT2U:CFN Weight Ratio | CFN Content (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 10 | 1 | 10:1 | 9.1 |

| H2 | 10 | 2 | 10:2 | 16.7 |

| H3 | 10 | 3 | 10:3 | 23.1 |

| H4 | 10 | 4 | 10:4 | 28.6 |

| H5 | 10 | 5 | 10:5 | 33.3 |

| H10 | 10 | 10 | 10:10 | 50.0 |

| Wavenumber (cm–1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| 3424–3333 | ν(O-H) keto–enol, 2-undecanone terminal |

| 2919–2917 | νas(C-H) aliphatic methylene |

| 2850–2851 | νs(C-H) aliphatic methylene |

| 2732–2731 | ν(C-H) aldehyde carbonyls |

| 1705 | ν(C=O) ketonic carbonyls |

| 1668–1663 | ν(C=C) di- and tri-substituted |

| 1605–1589 | ν(C=C) (mode 1) para-disubstituted Ar |

| 1467–1462 | δas(C-H) terminal methyl |

| 1380–1374 | δs(C-H) terminal methyl |

| 1209 | ν(C-CO-C) ketones |

| 1110–1106 | δip(C-H) (mode 1) para-disubstituted Ar |

| 1019–1018 | δip(C-H) (mode 2) para-disubstituted Ar |

| 982–969 | δop(C=C-H) (mode 1) double bonds |

| 891–890 | δop(C=C-H) (mode 2) double bonds |

| 828–824 | δop(C-H) para-disubstituted Ar |

| 720–719 | ρ(C-H) methylene |

| 608–600 | ν(M-O) spinel structure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ortiz-Vergara, V.A.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; González-González, V.A.; Lopez-Cuellar, E.; Martínez-de la Cruz, A. Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials Based on Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles and Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one). Surfaces 2026, 9, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010006

Ortiz-Vergara VA, Garza-Navarro MA, González-González VA, Lopez-Cuellar E, Martínez-de la Cruz A. Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials Based on Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles and Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one). Surfaces. 2026; 9(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz-Vergara, Victor Alfonso, Marco Antonio Garza-Navarro, Virgilio Angel González-González, Enrique Lopez-Cuellar, and Azael Martínez-de la Cruz. 2026. "Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials Based on Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles and Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one)" Surfaces 9, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010006

APA StyleOrtiz-Vergara, V. A., Garza-Navarro, M. A., González-González, V. A., Lopez-Cuellar, E., & Martínez-de la Cruz, A. (2026). Magneto-Photoluminescent Hybrid Materials Based on Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles and Poly(terephthalaldehyde-undecan-2-one). Surfaces, 9(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010006