Abstract

Fotis Kontoglou (1895–1965) was a prominent Greek painter and writer, known primarily for revitalizing byzantine painting in the 20th century and being one of the first artist-conservators in Greece active at this period. The current study represents the first systematic attempt to examine seven (7) icons (i.e., ecclesiastical panel paintings) attributed to Kontoglou, currently located in two famous monasteries in Laconia, Greece. The research utilized exclusively non-destructive analytical techniques, namely digital optical microscopy, UV-induced visible fluorescence photography (UVIVF), and portable X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF) spectroscopy, to identify the materials—particularly pigments—employed in the corresponding paintings. The results are interpreted under the light of Kontoglou’s own writings on painting, in particular his “Ekphrasis” painting manual. Preliminary assessments of surface morphology and state of preservation were achieved through macroscopic and microscopic probing, as well as through inspection under ultraviolet light, while further analysis was performed using portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. The results confirm the employment of both traditional and modern synthetic inorganic components, while comparisons with the pigments listed in Kontoglou’s “Ekphrasis” painting manual suggest his persistent use of a rather limited palette of pigments. Nevertheless, despite the fact that the paintings were executed in a small period of time (1954–1956), data revealed notable differentiation between the studied icons, which probably indicates procurement of materials from various sources. Given the scarcity of technical investigations of modern (20th century) paintings, this study is relevant and reveals some interesting hints, which may pertain to the trends of the mid-20th century Greek paint market, like, e.g., the rather limited distribution of Ti-white. Additionally, the current findings contribute considerably towards understanding Kontoglou’s artistic methods during a highly creative period and can be utilized to support future conservation efforts. Ultimately, the current preliminary study sheds light on some methodological aspects of the pertinent research and assists towards establishing a detailed protocol for future studies.

1. Introduction

Religious painting holds a central role in Eastern Orthodox Christian culture, combining spiritual significance with a long artistic tradition [1,2]. Even after the Seize of Constantinople and the end of Byzantium (1453), religious painting continued to be practiced in territories with Orthodox Christian communities, leading to the creation of thousands of pertinent works; interestingly, most of the Greek painters working within this framework showed adherence to the traditional way of painting [1,3]. However, after the formation of the Greek State in the early 19th century, academic painting emerged, and many icon painters started deviating substantially from the traditional, “Byzantine” religious painting style [4]. Similar trends have been documented in other Orthodox territories too, and it was not until the early 20th century that painters started exploring the rich world of Byzantine painting again, a tendency that was to a certain degree sparked by the rediscovery of old Byzantine icons in Russia and beyond [5]. A similar trend emerged in Greece too, yet in this case the person who initiated and led the reinvention and revival of the Byzantine painting was Fotis Kontoglou.

Fotis Kontoglou, a prominent Greek painter, writer, and practical art conservator, was born in Ayvalik (then known as Aivali), Asia Minor (Western Turkey), on 11 November 1895. As his father passed away early, he was raised by his mother and uncle, Archimandrite Stefanos Kontoglou [6]. He spent his school years in Ayvalik, completing his education while also contributing to the student magazine Melissa [6]. In 1913, Kontoglou studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts, entering the third year due to his natural talent. Two years later, he left his studies and traveled throughout several countries. Eventually, he settled in Paris, where he lived until 1919 and wrote the book Pedro Cazas [6,7]. His stay there functioned as a preparatory period; while his exposure to post-Byzantine painting may have provided him with foundational techniques and stylistic approaches, it was Europe that enabled him to create without imitation, embracing modern ideas [7].

Upon his return to Ayvalik, he started teaching French and Art at a high school [8]. However, due to the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), he was forced to become a refugee, first relocating to Lesbos and then to Athens, where he first worked for the well-esteemed Εγκυκλοπαιδικόν Λεξικόν Ελευθερουδάκη (Eleftheroudakis Encyclopaedic Dictionary) [6].

The year 1922 represents a landmark in his artistic and literary development. He visits Mount Athos, and, during his stay there, he wrote numerous texts, primarily dedicated to Stratis Doukas—which were included in the first edition of Vasanta published in 1923. However, the longer he stayed in the Athos monastic community, the more he became fascinated by post-Byzantine art, making copies of many pertinent works [6]. That same year, also he held an important exhibition with the already very famous contemporary painter Konstantinos Maleas and displayed his works at the Girls’ Lyceum of Athens [6,8].

Kontoglou married Maria Chatzikampouri, a fellow Ayvalik native, in 1925, and their daughter Despina (now Mrs. Martinou) was born in 1927 [6,9]. Between 1924 and 1932, Kontoglou moved five times before settling with his wife and daughter in a house of his own at 16 Vizyinou Street in Athens [9]. In 1932, with the help of the renowned painters Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos, he created frescoes in his own home at 16 Vizyinou Street—works that are now housed in the National Gallery [9].

His conservation work began in 1930 at the Byzantine Museum of Athens, followed by positions at the Coptic Museum in Cairo (1933) and the Corfu Museum (1934–1935). From 1936 onward, he worked on preserving and cleaning the extremely important Byzantine wall paintings of the Perivleptos Church in Mystras, Laconia, Greece [6].

Additionally, during the 1930s, he produced a large number of icons (religious panel paintings), while his first wall paintings in small chapels marked the initial link in a chain of tireless efforts to revive the post-Byzantine iconographic tradition [6]. During the same period, he participated in numerous exhibitions in Greece and abroad, and between 1937 and 1939, he executed Byzantine-style murals (primarily scenes pertaining to Athens’ history) at the Athens City Hall [6].

After the end of World War II, and in particular from 1945 onward, with his students, he dedicated himself to painting numerous churches—including the Kapnikarea Church in Athens (1942–1953)—and created a large number of portable icons. Guided by the traditions of Byzantine and Greek folk art and drawing additional inspiration from earlier artistic periods such as the Fayum portraits, he consistently advocated for the authenticity of Greek artistic expression [10]. His work played a pivotal role in shaping modern ecclesiastical painting and beyond, and his contribution is regarded as both foundational and enduring [11].

Besides being a multifaceted and gifted artist, Kontoglou was also a distinguished educator who founded a significant iconography workshop with the primary aim of imparting his profound experience and knowledge to the next generation [1]; one should not overlook the very significant impact of Kontoglou’s writings on modern Greek literature. In addition, his overall contribution was well recognized from his contemporaries, and in 1960 he was awarded the Athens Academy Prize for his two-volume work Ἔκφρασις τῆς Ὀρθοδόξου Εἰκονογραφίας (Ekphrasis of Orthodox Iconography), published by Astir [7,12]. Sadly, Kontoglou passed away on 13 July 1965, in Athens, his death being the result of complications following surgery necessitated by a car accident [8].

The aforementioned Ekphrasis by Kontoglou is a work that outlines traditional techniques and the principles of Byzantine and post-Byzantine iconography, emphasizing the spiritual and artistic discipline required for this sacred art [13]. It was first published in 1960 and serves both as a technical manual and a philosophical/theological guide, reflecting Kontoglou’s devotion to simplicity, humility, and timeless craftsmanship in religious painting. It is worth noting that Ekphrasis can be seen as a natural continuation of the renowned Dionysius’ of Fourna Ἑρμηνεία τῆς Ζωγραφικῆς Τέχνης (Hermeneia of the Art of Painting) painting manual, and it is true that its technical content overlaps in part with the latter text [14,15]. Written between 1728 and 1733, Dionysios’s manual remains one of the most significant efforts to preserve and transmit the Byzantine tradition of icon painting [15,16]. Addressed to practicing iconographers, his work adopts a practical and prescriptive tone, codifying both the technical processes and thematic conventions of Orthodox iconography.

Writing in the mid-20th century, Kontoglou builds upon this foundation while significantly expanding its scope. Although his Ekphrasis serves a similar instructional purpose, it is also deeply theological and polemical, against the introduction of naturalistic painting in religious contexts, defending the spiritual and aesthetic integrity of Orthodox iconography against Westernizing influences. Thus, the relationship between the two works reflects more than a mere transmission of artistic technique; it embodies a deeper continuity of Orthodox tradition, encompassing theology, aesthetics, and cultural identity, from the post-Byzantine period to the modern era [12].

According to Kontoglou’s guidelines in “Ekphrasis”, the following pigments and dyes are decent and therefore proper for painting religious themes, while they are also recommended as “stable and unaltered by the passage of time”. On this basis, these pigments might have been integral to his iconographic art, used individually or in combination to produce various shades. While many are common in traditional painting, they are presented here from Kontoglou’s unique perspective and using his own terminology [13].

- White (“άσπρον”):

Kontoglou states that white serves as the foundation for all colors in iconography, since all pigments are mixed with it in order to produce the various corresponding shades. Therefore, painters must pay special attention when selecting his white pigment. Kontoglou preferred titanium white for its durability and brilliance over alternatives like zinc white, and suggests the addition of a bit of zinc white to avoid “whitening too much” [13].

- Black (“μαύρον”):

Charred ivory yields the finest quality black pigment, according to Kontoglou, while soot and other bone-blacks can serve as alternatives. Black was essential for depicting shadows in skies, doors, windows, and caves [13].

- Ochre (“ώχρα”):

A class of yellow-gold earth pigments deriving “from the rust of iron”, can be found in various tones, from reddish (“πολίτικη”/“politiki”) to greenish-yellow (“βενέτικη”/“venetian”). Apart from major substances of many colors (like, e.g., flesh tones), ochre was also used as a base for crowns of the Saints, and Kontoglou explicitly states that ochre is an “unaltered and strong” pigment (“χρώμα αναλλοίωτον και δυνατόν”) [13].

- Raw Sienna (“σιέννα ωμή”):

This is a deep yellow resembling the color of wood, hence often named “deep ochre” (“βαθείαν ώχραν”) by the old masters. Like ochre, it is an earth pigment considered to be “unaltered” (“αναλλοίωτον"), often used as a base for rendering gilded highlights [13].

- Burnt Sienna (“σιέννα ψημένη ή καμένη”):

This earthy red-brown pigment is considered as stable as raw sienna and was also employed as a base for rendering gilded highlights/striations (“χρυσοκονδυλιές”) [13]. Additionally, Kontoglou mentions that the old craftsmen used the term bole (“βώλο”) for this very pigment.

- Raw Umber (“όμπρα ωμή”):

Resembling earthy tones ranging from brown to ashen green, raw umber was often used for flesh undertones and garments, and it often served as the dominant color for particular dresses [13].

- Burnt Umber (“όμπρα ψημένη”):

A stable earth pigment of a blackish-red or deep-brown shade, burnt umber can be mixed with white to produce an exceptional violet tone according to Kontoglou [13].

- Chondrokokkino (“χονδροκόκκινο”):

This pigment is described as “not too red…yet very sweet and stable” (“δεν είναι πολύ κόκκινον…αλλά είναι γλυκύτατον και στερεόν”) and is an earth material composed of “iron rust” (“σκουριά του σιδήρου”) that was valued for its depth and richness [13].

- Lazuri or Indikon (“λαζούρι ή ινδικόν”):

According to Kontoglou this pigment was imported from India and provided a mauve tone; however, being a “plant-based” pigment, it was rather unstable (“αδύνατον”). Kontoglou adds that “now, we have loulaki (“λουλάκι”, i.e., synthetic ultramarine), which is very stable and can also be used on wall painting” [13]. The interchangeable use of the terms lazuri and Indigo by Kontoglou is confusing, since the former is most commonly used in association with mineral blue pigments (mainly lazurite and azurite) [14,17].

- Cobalt (“κοβάλτιον”):

A durable, light blue pigment, cobalt was suitable for wall painting [13].

- Copper Green (”πράσινον του χαλκού”):

Produced from copper and vinegar, this “stable” (“στερεόν”) green pigment was often used for intricate details in iconography and was once named “vardaramon or tsigkiari” (“βαρδάραμον ή τσιγκιάρι”) [13].

- Lake (”λάκκα”):

This is a deep crimson pigment made from natural dyes like lac resin or Brazilwood, which, however, was rather impermanent; therefore, it was either used in the form of glazes or varnished to preserve its delicate color [13].

- Vermillion (“κιννάβαρις”):

This vibrant red-orange hue, resembling pomegranate flowers, was made from mercury and was commonly used for writing red text in manuscripts and in particular for signing imperial documents [13].

In each era, the availability—or lack—of particular pigments shaped the way artists approached their use. For instance, during the Middle Ages, each pigment was treated with great significance, as though it were an exceptionally valuable component of the palette, and it was rarely diminished through mixing. Such mixing typically occurred for economic reasons or due to the rarity of a particular pigment [18].

This reverence for pigments is less evident in more recent periods, in which access to a wide variety of shades and types of colored pigmented substances is considerably easier [18]. In his era, Kontoglou may have had access to various pigments, but he believed that polychromy did not suit the divine character of iconography and that icons should reflect modesty. Nevertheless, specific combinations were carefully crafted to enhance details in religious icons, showcasing both artistry and precision [13,19]. Hence, Kontoglou provides detailed instructions on the proper mixing of pigments, and the resulting combinations reflect his commitment to traditional techniques, offering a timeless palette steeped in spiritual symbolism. It is worth transcribing Kontoglou’s concluding phrase about pigment mixing: “Yet you shall avoid the many and various colors (i.e., pigments), and hold dear the simple and humble ones, and those (pigments) that appear like faint due to oldness” [13].

Kontoglou’s work was extremely influential for his contemporaries and the painters to come, and this is well demonstrated by the fact that many Greek 20th-century painters were either direct students of his (like the renowned painters Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos), or obviously influenced by his work [20,21], as well as by the great interest of scholars about his artistic work and overall activity that was sparked far before his unexpected death; in addition, Kontoglou has been commonly considered among the artists of the so-called “Generation of the Thirties” [22], while he is admired for both his paintings and writings [23].

Despite the significance of his work, to the best of authors’ knowledge, none of Kontoglou’s paintings have hitherto been studied by means of analytical techniques. In fact, it appears that the technical studies of Greek 20th-century paintings are indeed very scarce, since only a handful of pertinent publications exist [24,25,26,27]; therefore, a significant gap in the contemporary technical literature is documented. It is worth noting that, contrarily, several technical investigations of contemporary European paintings exist, which have gradually built a considerable body of literature [28,29,30,31,32]. In this view, the current study aims primarily to compensate—at least partially—for this gap. The main target of this study is to identify the painting materials (focusing on pigments) employed by Kontoglou in certain icons, in order to assess if the pigments used in his paintings correspond to those described in Ekphrasis and traditionally employed in post-Byzantine iconography. Also, the technical investigation of Kontoglou’s icons will provide evidence about his working methods and painting materials. Thus, another critical question may be answered: did Kontoglou remain adhered to particular materials upon rendering his paintings, or did he rely on materials deriving from different sources? This data will certainly provide sound foundations for expanding the research on Kontoglou’s paintings, which will allow for proper management and conservation planning of his extremely valuable artistic legacy. To this end, seven (7) Kontoglou icons that are currently kept in two Greek monasteries were thoroughly studied in situ using non-invasive and portable techniques, like digital microscopy and portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. Details of the methodology are provided below.

2. Materials and Methods

For the study, the authors investigated seven (7) icons painted by Fotis Kontoglou between 1954 and 1956, which are currently located in two monasteries in the region of Laconia (monasteries of St. Anargyroi & Forty Martyrs). Indicative images of the paintings, along with the corresponding details, are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Note that the state of preservation was classified on the basis of the framework presented by Keene Suzanne [33]. In particular, four levels can be identified:

Figure 1.

Pictures of the examined portable icons. (a) Archangel Michael; (b) Archangel Gabriel; (c) Prophet Isaiah; (d) Prophet Zechariah; (e) Prophet David; (f) Prophet Jeremiah; (g) Saint Alexios.

Table 1.

The corresponding dimensions and year of creation of the examined portable icons. In the case of the Archangels’ icons, the width was not measured (n.m.) due to inaccessibility.

- Condition Scale 1—VERY GOOD: The object is in very good preservation/conservation condition or stable.

- Condition Scale 2—GOOD: Good condition, possibly deformed or worn but stable, not requiring immediate intervention.

- Condition Scale 3—FAIR: Poor condition, potentially unstable, where intervention is desirable or necessary.

- Condition Scale 4—POOR: Unacceptable condition, completely unstable and actively deteriorating, with the risk of affecting other objects. Immediate intervention is required.

The adopted methodology included only non-invasive techniques, i.e., photography under ultraviolet illumination (ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence—UVIVF), digital optical microscopy, and portable X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF) spectroscopy. In particular, a 500× Zoom USB Digital Microscope (Smart Electronics, Shannon, Ireland) was used, connected to a MacBook Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) to document all points of interest on the icons in situ. Microphotographs were captured using the microscope’s integrated 2 MP camera, achieving magnifications of up to 500×. After the preliminary investigation under the digital microscope, the paintings were further examined and photographed under UV light. UV photography of the icons was conducted in situ at the monasteries using specialized UV lamps and a Nikon D3400 DSLR camera (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an 18–55 mm AF-P Nikkor lens in fully manual mode. For the best results, the space was completely darkened, with the only light source being two T8 18W G13 Blacklight fluorescent tubes (emission peak at 365 nm) positioned at a distance of 30 cm and a 45-degree angle to the left and right of each icon. The camera was mounted on a tripod to prevent image blur due to long exposure time and was used without additional filters. Additionally, all the icons were thoroughly examined in situ using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. In detail, for the XRF analyses, a Tracer 5 g spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used. This spectrometer is equipped with an Rh-target X-ray tube (maximum voltage range 50 kV, maximum output: 4 W) and utilizes a high-performance 1 μm graphene window silicon drift detector (SDD). In the framework of the current study, the generated beam was collimated by a 3 mm collimator; on each icon, several spots of interest were selected based on macroscopic and UV inspection, and from each point two distinct spectra were collected: the first with the spectrometer operating in a 15 kV–30 μA (no filter) mode for the detection of low Z elements (13/Al to 26/Fe) and the second in a 50 kV–30 μA (+Ti/Al composite filter) set up for the excitation of the higher Z elements (29/Cu to 82/Pb). The spots of the analyses are marked on the corresponding figure provided as Supplementary Materials (Figure S1). Spectra were collected for 10 s and were subsequently processed using the Artax software (version 8.0.0.476, Bruker), through which the net intensities of the identified elemental peaks were calculated. Given that spectra from different points of analysis were collected using the same parameters (voltage, current, acquisition time), the calculated net intensity values are comparable. Of note, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was calculated by dividing the net intensity of a given peak with the noise of this very peak, with the latter being equivalent to the square root of the corresponding background [34]. In cases of low peak intensity elements like Al, SNR values above 20 were calculated in all cases, while in cases of major elemental peaks (like, e.g., peaks due to Fe and Zn) the SNR values were in most of the cases well above 1500. Finally, of note is that the employed spectrometer parameters led to high count rates (30,000 to 60,000 cps) and dead times of around 5%, thus securing reliable statistics of the collected spectra.

3. Results

3.1. Digital Microscopy

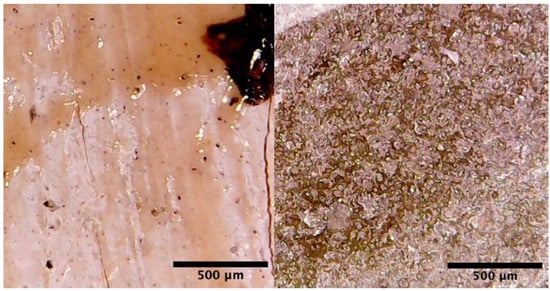

Detailed probing through the digital microscope revealed that all studied icons exhibit common micromorphology in the paint layers, sharing similar color and texture characteristics. Interestingly, the presence of varnish is not detected on most of the icons, with the icon of St. Alexios being an exception, where varnish is occasionally observed (not consistently; see Figure 2). Similarly, for the icon of Archangel Gabriel, there is some suspicion of the presence of a thin varnish layer in certain areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of Saint Alexios and Archangel Gabriel. The off-white paint layer (scroll) is partially covered by varnish, while the brown paint layer (himation) of Archangel Gabriel shows possible signs of a thin varnish layer (200×).

Most paint layers, apart from yellow, exhibit significant inclusions of both white and dark particles, thus indicating a strong tendency to produce desirable colors though pigment mixing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Microphotograph of Prophet Zechariah’s green tunic; paint layer containing numerous white, dark, and reddish inclusions (200×).

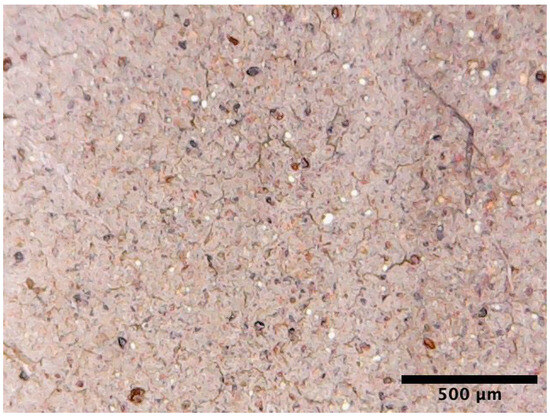

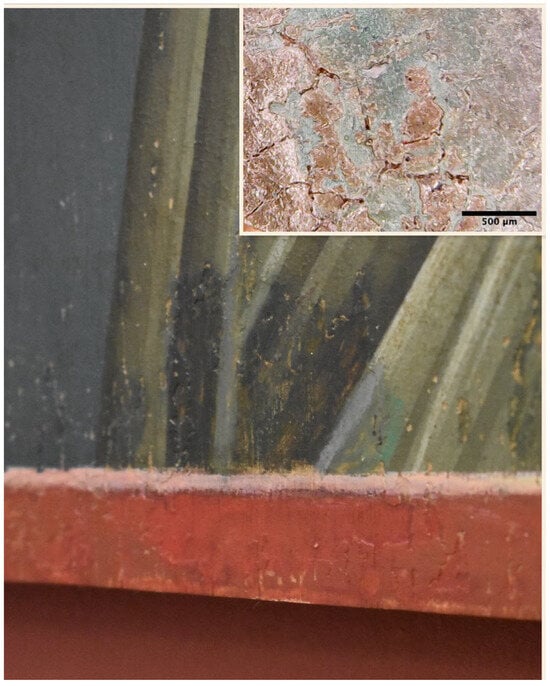

Additionally, all icons display cracking and sporadic losses of paint layers across their surfaces, while small cracks are also detected on the gilded background of St. Alexios’ icon (Figure 4, left and middle). Generally, the paint layers exhibit uniformity in their application technique. In particular, it is obvious that Kontoglou painted these icons by using multiple overlapping yet not intermixed paint layers, which is the typical stratigraphy of post-Byzantine painting (Figure 4, right) [14]. Recent interventions on the icons, mostly on Prophet Isaiah, Zechariah, and Jeremiah, reveal differences in the pigments used on the same surface, as seen in both USB microscope images and standard photographs (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

(Left): USB microphotograph of St. Alexios. Cracking of the gold background (200×). (Middle): USB microphotograph of St. Alexios. Cracking in the paint layer of the Saint’s head (cheek) (200x). (Right): USB microphotograph of St. Alexios. Loss and exposure of the underlying substrate, marginal line (200×).

Figure 5.

USB microphotograph (200×) and standard photograph of Prophet Jeremiah. Recent interventions on the red and green layers of the icon are evident. The USB microphotograph reveals the newly added section of the green cloth.

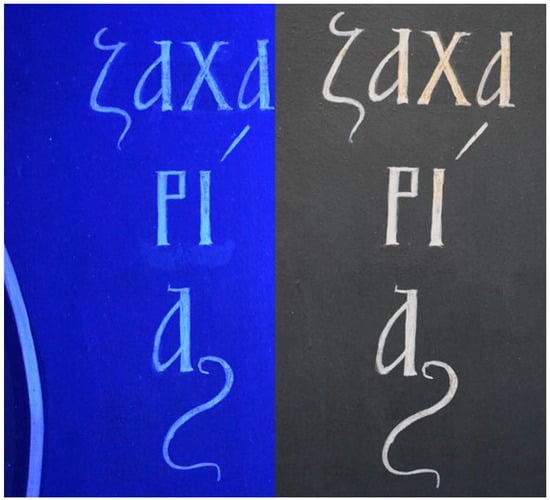

3.2. UV Photography

Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UVIVF) imaging was employed as a complementary technique to highlight surface coatings (e.g., varnishes) and previous restorations. While UVIVF can reveal areas of interest that are not apparent under visible light, fluorescence responses are non-specific, with multiple natural and synthetic materials producing similar emission colors. In addition, the appearance of fluorescence is influenced by material aging, previous treatments, environmental factors, and the excitation/capture set up, meaning that UVIVF observations are primarily qualitative. Therefore, UVIVF served as a screening tool to guide sampling and interpretation, with material identification attempted through X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

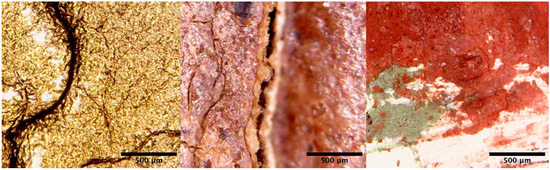

Upon UV photography, fluorescence was mainly observed in the white pigments of the portable icons (Figure 6, left), as well as in certain overpainted areas that were invisible to the naked eye (Figure 6, middle and right). In all icons except for the St. Alexios icon, strong fluorescence was evident in regions containing white pigments and highlights, which are, in fact, composed of various pigments mixed with white (Figure 6, left). There is a possibility that lithopone was used as a preparatory layer—since this pigment exhibits fluorescence upon exposure to UV radiation—particularly in the case of the St. Alexios icon, where preliminary analysis detected a possible preparatory substance on the side of the icon (Figure 7, left). The results were then compared with Dr. Cosentino’s study of 54 historical pigments [35].

Figure 6.

(Left): Depiction of the fluorescence of white pigments in the icon of the Prophet Isaiah. (Middle,Right): Depiction of Archangel Gabriel in ultraviolet light (middle) and visible light (right). Under ultraviolet light, a correction to the Archangel’s hair becomes visible.

Figure 7.

Depiction of Saint Alexios under ultraviolet light. On the side of the icon, drips of varnish are revealed (left), while the same, orange-fluorescent material appears on the recto of the painting (right); the distribution of the fluorescence reveals that the varnish was not evenly applied over the surface of the icon.

In addition, according to the literature [35], zinc white exhibits the most intense fluorescence among white pigments, while lead white and lithopone fluoresce at varying intensities depending on the binding medium. In contrast, titanium white, due to its strong UV absorption, lacks fluorescence [35]. Therefore, the presence of fluorescence is significant, as it can, in combination with p-XRF analysis results, aid in precisely identifying these white pigments. The consistency between similar colors’ fluorescence patterns across the icons, or lack of it, suggests the use of similar pigments across the studied works.

Patches of an orange-colored fluorescent material—probably a varnish [36]—were observed primarily along the painted areas of the St. Alexios icon, and on the lettering and halo outline on the gilded campus (Figure 7, right). It is worth noting that the orange-colored fluorescence is considered a characteristic of shellac [37,38], while Kontoglou explicitly mentions that only the lettering and halo outlines on gilded areas should be covered with shellac [13]. Interestingly, the absence of pertinent fluorescence on the Prophet and Archangel icons appears consistent with the writing of Kontoglou, yet in order to securely exclude the presence of varnish in these icons, additional technical analysis is needed (e.g., ATR-FTIR).

Finally, in the Archangel Gabriel icon, over-painting was detected around the head, indicating the iconographer’s effort to reduce the hair size (Figure 6, middle and right), while later interventions were also spotted in other icons through inspection under UV radiation, thus highlighting the extent of later restoration interventions (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

UV and visible (VIS) photography of the inscription of Prophet Zachariah revealed a clear distinction beneath the letters “ΡΙ” (“RI”) in the UV image, which is not visible to the naked eye.

3.3. XRF Spectroscopy

The results of the p-XRF analyses are summarized in Table 2; in order to proceed with the evaluation of the data, the latter were assessed under the light of pre-existing studies, as well as through comparisons with the open access XRF spectra database provided by CHSOS [39]. Significant similarities as well as notable differentiation were identified among the analyzed portable icons.

Table 2.

Summary of the p-XRF results; numbers correspond to the net intensities of the elemental peaks.

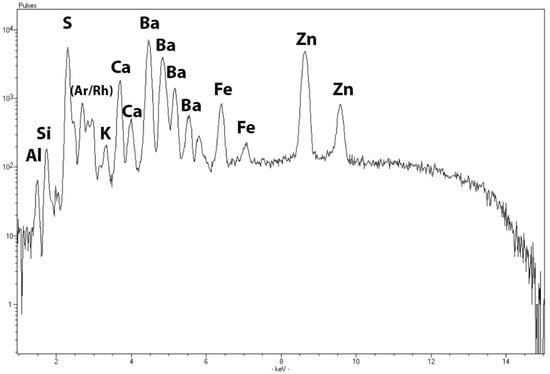

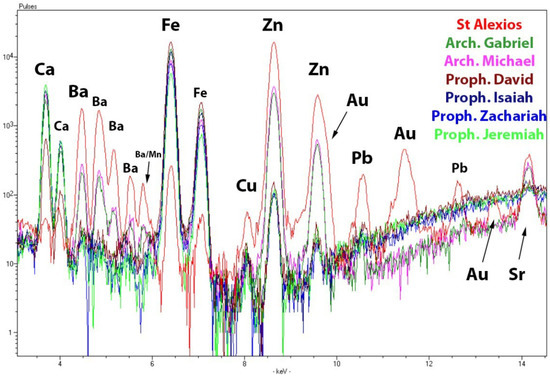

All the spectra revealed elements primarily associated with white pigments/compounds and fillers, in particular calcium (Ca), zinc (Zn), and barium (Ba); indeed, these elements show high-intensity peaks across the measurements, regardless of the color. The consistent presence of these elements suggests that corresponding compounds were probably used as base colors, highlights, or preparation materials [19,20]. Notably, due to the XRF technique’s penetration depth, the results also reflect the composition of underlying layers; therefore, identification of specific compounds is not an easy task. Based on the results and comparison with similar studies, such as the examination of early 20th-century Theophilos artworks [27], the analysis of 20th-century overpaintings on two late 16th century Greek icons [40], and a recent p-XRF analysis of certain late 19th-century Vincent van Gogh paintings [28], the detection of the elements Ca, Ba, and Zn can be associated with numerous components like calcite (CaCO3) and/or gypsum (CaSO4∙2H2O, compatible with the strong presence of Ca peaks), along with zinc white (ZnO), barium sulfate (“permanent white”–BaSO4), and lithopone (a mixture of ZnS and BaSO4), which are compatible with the simultaneous detection of barium (Ba) and zinc (Zn) elemental peaks. It should be noted that the artworks of Theophilos and Kontoglou provide relevant points of comparison, as both artists lived during the same period and held mutual respect for each other’s work.

According to Kontoglou’s ‘Ekphrasis’, “τσίγκος” (“tsigos”) was used as the main component in ground preparation (gesso layer) [13]; since this term is still widely used by Greek craftsmen to refer to lithopone, it seems likely that this compound was indeed used to make the grounds of the icons in consideration. In fact, bare ground was only spotted in the case of the St Alexios icon and in this instance the XRF analysis revealed the presence of the elements Zn, Ba, and S, along with minor Ca (Table 2 and Figure 9). The three first elements corroborate the assumption of lithopone employment, while Ca appears to pertain to a minor component (probably calcite); in addition, Kontoglou asks for the addition of a bit of “στόκος” (“stokos”) in the lithopone [13] and it seems that the Ca of the ground in the St Alexios icon pertains to this very compound. It is worth noting, however, that in the framework of traditional post-Byzantine Greek iconography, the preparation layers were almost exclusively made using natural calcium sulfate compounds (mainly gypsum and anhydride) [41,42,43,44]. Interestingly, gypsum is also explicitly recomended as the material for making ground by hieromonk Dionysios of Fourna, whose early 18th-century painting manual “Hermeneia” [15] was extremely influential for the painters to come and for Kontoglou too [14]. In this view, the choice (and recommendation) of Kontoglou to use lithopone for making icons’ ground is a notable deviation from the “traditional” practices, and this is a finding indeed worth underlining.

Figure 9.

XRF spectrum (15 kV–30 μA) from the Saint Alexios icon ground (logarithmic scale).

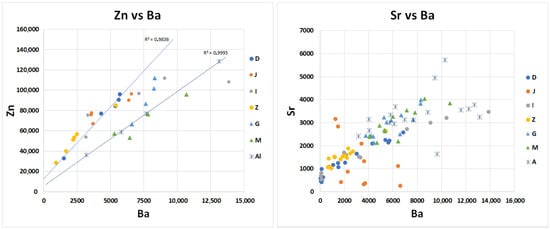

Although the presented data herein is merely qualitative, it is worth attempting to further assess the nature and potential differences between the white components used in the studied icons. To this aim, the peak intensities of the elements Ba and Zn from the white-colored areas (namely highlights, white contour lines, and scroll backgrounds; see Table 2) were plotted, and the corresponding graph is shown in Figure 10, left. Interestingly, in most of the cases, there is a linear correlation between the Ba and Zn peak intensities, thus indicating the use of specific components. Additionally, the data deriving from the Prophets’ icons show a strong correlation, and they seem to more or less align with the trend line of white-rendered areas in the Prophet David icon. Contrarily, the white areas in the St Alexios icon show substantially deviating Zn vs. Ba ratios and the two white areas in the Archangel icons seem to better fit with the trend line of these very points. On this basis, it is inferred that Kontoglou used at least two distinct Ba- and Zn-containing components, either lithopone or mixtures of zin oxide and barium sulfate, which were both indeed widely used by 20th-century painters [29]. Here, it should be noted that deviations from the major trend lines are expected since other (i.e., non-white) Ba- or/and Zn-bearing components may exist below the white-colored areas analyzed. Additionally, of interest is the correlation between the intensities of the Ba and Sr elemental peaks (Figure 10-right) since it has been recently shown that the ratio of the contents of these two elements can potentially be used as a discriminating factor [45]. In most of the corresponding spots, a linear correlation between these elements is documented, thus suggesting employment of a single-origin barium sulfate component. Nevertheless, some samples like the majority of the spots of analysis for the Prophet Zachariah icon and numerous spots in the St Alexios icon show significant deviation (lower ratios), suggesting the employment of a different component. It should be finally noted that minor Sr is detected even when the intensity of Ba elemental peak is almost zero, and this finding clearly shows that other (minor) Sr contributors exist, most probably calcium sulfate compounds [43,46].

Figure 10.

(Left): Zn (Kα) versus Ba (Lα) elemental peak intensities (Table 2), white-colored areas; trend lines correspond to Prophet David (light blue) and St Alexios (dark blue) data. (Right): Sr (Kα) vs. Ba (Lα) elemental peak intensities, complete data set (all analyzed spots/icons). Abbreviations: D: David; J: Jeremiah; I: Isaiah; Z: Zachariah; G: Archangel Gabriel; M: Archangel Michael; A: St Alexios.

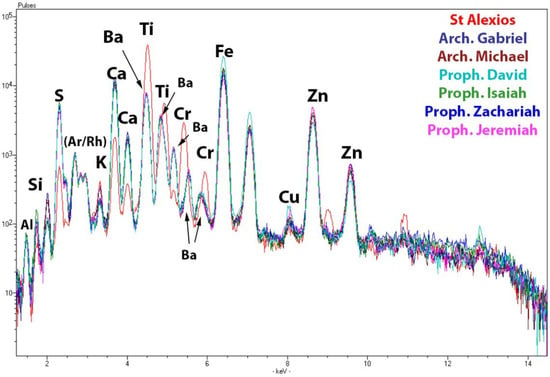

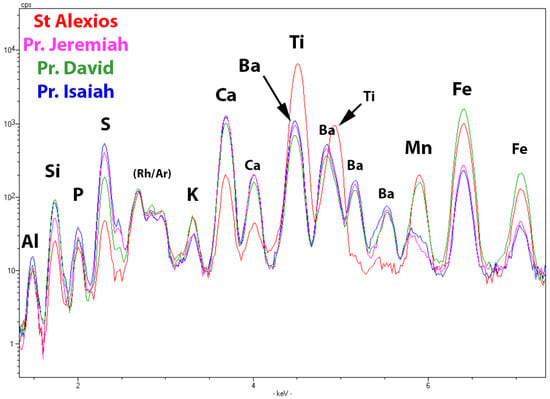

In the framework of the attempt to investigate white pigments, it should be noted that the barium Lα1 transition almost coincides with the titanium Kα transition (4.47 vs. 4.51 keV, respectively); therefore, titanium peaks are difficult to spot in paints that contain barium too. In particular, since most of the analyzed spots show relatively high Ba Lα transitions (Table 2), Ti peaks were securely identified only in the case of the St. Alexios painting. Indeed, in the white tones of the St Alexios icon, XRF analysis revealed significant titanium peaks, suggesting that titanium white (TiO2) may have been the primary white pigment for particular iconographic elements like the flesh tones, the garment highlights, and the scroll. By contrast, in the Prophet and Archangel icons, the flesh highlights were rendered using a Ba- and Zn-rich paint, obviously either lithopone or a ZnO and BaSO4 mixture, which were both commonly used by 20th-century painters [29]. (Figure 11). The documentation of the use of Ti white in only one out of the seven studied paintings is a notable finding, in particular because in his painting manual (Ekphrasis), Kontoglou clearly expresses his preference for this particular pigment by stating, “In my opinion, based on my experience, the best and more stable white color is titanium” (“Κατά την γνώμην την ιδικήν μου, από την πείραν οπού έχω, το καλύτερον και στερώτερον άσπρον χρώμα είναι το τιτάνιο” [13]. One possible explanation for the scarce use of TiO2 white in these paintings might be the fact that, despite its rather early industrial production (1918; see [47]), TiO2 was not widely adopted by painters of that time, and its use started becoming widespread well after the end of World War II [48].

Figure 11.

White highlight on flesh parts, St Alexios (Ti-dominated, red spectrum), vs. spectra from the same pictorial element from the other icons. Spectra were collected with a 15 kV–30 μA spectrometer set up (logarithmic scale).

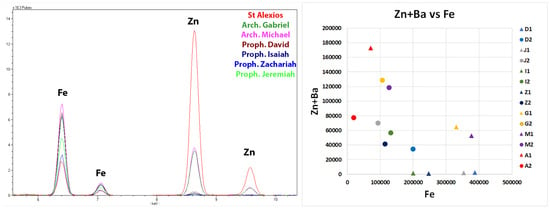

Apart from Ca, Zn, and Ba, most of the spectra show intense peaks of iron (Fe), particularly those collected from areas with red-, brown-, and yellow-colored hues. The predominance of iron and the absence of other elements that pertain to widespread red pigments like Pb (lead oxide/minium) and Hg (mercury sulfide/vermilion) reveal that Kontoglou used exclusively Fe-based pigments to render these hues. These pigments were indeed very commonly used in the framework of icon painting, alongside cinnabar (HgS) and minium (red lead oxide) [27,49,50,51]. It is worth highlighting the absence of the latter two pigments from the studied icons; in fact, upon completing his list of recommended pigments (which contains HgS-“κιννάβαρι”), Kontoglou argues that a painter should limit himself to the use of “…the eleven first pigments of the aforementioned list (i.e., excluding cinnabar and lake red), since these are enough for a painter to use in his work without compromising, as we did too. Because the excessive use of many colors is not proper for our ecclesiastical painting, which is strict and delighted in humble colors” (“…εις τα ια’ οπού προεγράψαμεν, διότι είναι αρκετά να κάμη τινάς την εργασία του, δίχως να του λείψη τίποτε, όπως εκάμαμεν και ημείς. Διότι η υπερβολική ποικιλοχρωμία δεν είναι καλή δια την εκκλησιαστικήν τέχνην μας, οπού είναι αυστηρά και ευφραίνεται εις την σεμνοχρωμίαν” [13].

Nevertheless, the p-XRF analysis results suggest that Kontoglou used similar (in terms of hue) but significantly different (in terms of composition) colors for rendering various pictorial elements. A characteristic example is the red marginal lines, a standard pictorial element encountered in almost all icons. Indeed, the relevant spectra show evidently that the red paints used for the margins of the two Archangel icons are of almost identical composition, as they both show high Fe and moderate Zn (Figure 12 left). Contrarily, the four Prophet icons bear red marginal lines that contain notably lower amounts of Zn, while the St Alexios icon margin stands out due to its rather low Fe content and the very significant presence of Zn (Figure 11). This finding reveals that, even in a rather small period of time (1954–1956), Kontoglou used a variety of paints to render given iconographical elements, and this obviously hints towards the procurement of materials from various sources.

Figure 12.

(Left): Detail of the 15 kV/30μA XRF spectra from red marginal lines, from all the studied icons. Spectra displayed on a linear scale. (Right): Zn (Kα) + Ba (Lα) peak intensities versus Fe (Kα) peak intensities, flesh primary colors (Δ) versus the corresponding data from flesh highlights (○) (D: David, J: Jeremiah, I: Isaiah, Z: Zachariah, G: Gabriel, M: Michael, A: Alexios).

Additionally, the p-XRF analysis of the flesh tones returned very interesting results. Prior to commenting on this data, it must be emphasized that Eastern Orthodox ecclesiastical painting is practiced under a rather strict technical framework, within which many practical details are well defined. For instance, there are specific rules on how one should paint body parts like faces, hands, and feet, and Kontoglou himself offers detailed, pertinent instructions, including recipes for making the corresponding colors, i.e., flesh primary color/proplasmos-“προπλασμός” and flesh highlights/sarkomata-“σαρκώματα” [13]. In a similar way, Dionysius of Fourna in his pioneering “Hermeneia” painting manual offers recipes that dictate the type and quantity of pigments to be mixed in order to produce these particular colors [15]. In all these cases, the primary flesh color (proplasmos) is made by mixing earth pigments (ochre, sienna, umber) with a bit of white (and occasionally black or green too), while the highlights are rendered in mixtures of white, ochre, and red. In the case of the icons discussed herein, it has been already demonstrated that the white pigments were—in all but one instance (St Alexios icon)—Ba- and Zn-based; therefore, potential variations in the compositions of flesh tones can be revealed by plotting the sum of Zn plus Ba elemental peak intensities versus the Fe peak intensities. The pertinent graph is shown in Figure 12 (right), and it readily reveals that the four Prophet icons show notable compositional similarities as for their primary (triangles) and highlighting (circles) colors; the latter deviate substantially from the colors used to render the same pictorial elements in the case of the Archangel icons, since the Archangels’ flesh tones show enhanced contents of Zn and Ba.

Notably, the St Alexios flesh tones show a very peculiar trend, since the dark primary color (proplasmos) shows substantially higher Zn + Ba content in comparison to the—far lighter in tone—highlights. These, at first sight, abnormal flesh color compositions emerge due to the use of Ti-white exclusively in the case of the flesh highlight; the reserve use of Ti-white only for highlighting suggests that this pigment was highly prized by Kontoglou—something which is also evident by his writing (see above)—while restricted access to this particular painting material might also have been another reason for its scarce use. In addition, these findings are in line with the results of pertinent studies that highlight the gradual diffusion of this pigment in the post-World War II painting material market [29,48]. In addition, the St Alexios proplasmos color is the only pictorial element that contains detectable Cl, and this is an additional clue that differentiates this particular icon from the others examined in the current study (Table 2).

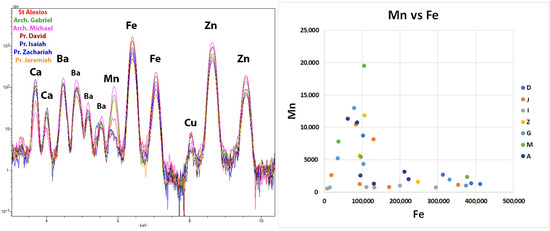

The persistent mixing of the Fe-based pigments with white ones is readily observed in the pertinent spectra too (Figure 13), since elemental peaks of Fe, Zn, and Ba coexist in all cases. However, it is apparent that different Fe-based pigments were used for rendering similar tones, as the manganese (Mn) elemental peak intensities show substantial deviations between the pertinent spectra. A characteristic example is the various red/reddish vestments. The corresponding spectra from the two Archangel and the Prophet Jeremiah icons show substantial Mn peak, whilst minor Mn is also detected in St Alexios’ vestment; contrarily, the corresponding spectra from the Prophets David, Zachariah, and Isaiah show practically no Mn (Figure 13, left). As for the latter, it should be noted that other Fe-dominated spots that show no Mn exist (Table 2). Nevertheless, when it comes to those paints that contain both Fe and Mn, it is particularly interesting to assess the correlation between Fe and Mn peak intensities. The pertinent graph is shown in Figure 13 (right) and clearly shows that at least two different Mn-bearing Fe-based pigments have been used in the painting of the icons in consideration: pigments that contain substantial Mn (peak intensity > 5000 counts) and pigments with rather low Mn content (Mn peak intensity < 5000 counts). Although the data presented herein are not quantitative, this finding suggests that Kontoglou used both sienna-type (low Mn content) and umber-type (elevated Mn content) pigments [50,52], which were both commonly used for rendering the underlayer of faces or garments, as well as for contours [42,51].

Figure 13.

(Left): Detail of XRF spectra from red-colored garments (50 kV spectra, logarithmic scale). (Right): graph of the net elemental peak intensities of Mn (Kα) vs. Fe (Kα), 50 kV/30 μA (D: David, J: Jeremiah, I: Isaiah, Z: Zachariah, G: Gabriel, M: Michael, A: Alexios).

Apart from red-colored areas, Fe peaks were also noted in XRF spectra collected from different colors, likely due to mixtures of Fe-bearing earth pigments with other pigments. In fact, red, yellow and brown earth pigments feature ubiquitously in Byzantine and post-Byzantine religious paintings, and they have been identified in numerous relevant portable and monumental works [51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]). It is worth noting that six out of the eleven essential pigments in Kontoglou’s list are Fe-based components, and it is also useful to recall his recommendation about the need to “hold dear the simple and humble ones (pigments), and those that appear like faint due to oldness” [13]. In this respect, elements like silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), and potassium (K) that are often detected in the p-XRF spectra (Table 2) can be probably attributed to pertinent pigments that were indeed predominant in Kontoglou’s palette.

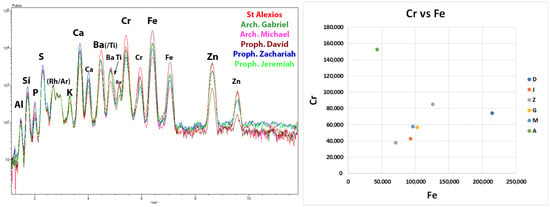

Fe is the dominant element in the p-XRF spectra collected from the yellow-colored areas of the Prophets’ and the Archangels’ icons (like, e.g., haloes; see Table 2), revealing thus the use of yellow ochre for rendering these pictorial elements (Figure 14). Nevertheless, it is obvious that the material used to render the halos of the Archangels’ icons deviated substantially from that used in the Prophets icons, since in the former, elevated Zn and Ba peaks are identified, along with the predominant Fe peaks (Figure 14, Table 2). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no natural Fe-based yellow pigment containing inherent Zn and Ba; therefore, the detection of the latter elements in the Archangels’ yellow halos can be safely attributed to the employment of lithopone or a ZnO plus BaSO4 mixture (see above), and this is a notable deviation from the composition of the Prophets’ halos, which contain only traces of Zn and no Ba (Figure 14). On the other hand, the halo and campus (background) of the St. Alexios icon are covered with a gold leaf, and this is the only case for verifying the employment of gilding in the studied icons. Gold leaves were frequently used to embellish the halos and backgrounds, as well as other pictorial elements, of icons produced in the framework of post-Byzantine religious painting; hence, the fact that Kontoglou used this material only in the case of the St. Alexios icon is notable. Interestingly, the spectrum collected from the St Alexios icon shows only minor Fe yet high Ba and Zn peaks (which obviously relate to the ground’s composition), along with elevated Pb (Table 2); these compositional characteristics reveal that the gold leaves were applied using a mordant (linseed-oil-based poliment) rather than bole (Fe-based clayey poliment) a finding in line with Kontoglou’s “Ekphrasis”, where only the mordant gilding technique is described for the attachment of gold leaves on icons [13]. Green-colored pictorial elements exist in all but one (prophet Isaiah) of the icons; the detection of elements such as K, Si, Ca, and Fe may, at first sight, appear as an indication for green earth (celadonite or glauconite) employment (Figure 15).

Figure 14.

XRF spectra from the haloes depicted on the studied icons. The demonstrated spectra were collected with a 50 kV/30μA set up and are displayed in logarithmic scale.

Figure 15.

(Left): XRF spectra from green-colored areas; spectra were collected with a 15 kV/30μA set up and are displayed here in logarithmic scale. (Right): elemental peak intensities of Cr (Kα) versus Fe (Kα), 15 kV/30μA (D: David, J: Jeremiah, Z: Zachariah, G: Gabriel, M: Michael, A: Alexios).

Nevertheless, chromium elemental peaks were detected in all the relevant spectra too; therefore, employment of chromium oxide or hydrated chromium oxide green pigments is inferred [52]. Based on the employment of Cr-green, the elevated Fe peaks may, at first sight, seem irrelevant. Nevertheless, the Fe Kα peak intensity shows—in most of the cases—a linear correlation with the Cr Kα peak intensity (Figure 16, and this finding suggests that a Fe component was intermixed with the Cr pigment; since mixtures of viridian green with Prussian blue were commonly used in the framework of 20th-century European painting [31], it seems possible that a similar mixture was employed by Kontoglou too. However, the Cr vs. Fe peak intensity graph reveals the existence of two outliers: the Prophet David’s green precious stone and the St Alexios’ green ground (Figure 16). The former shows substantially more iron in comparison to the other green colors, which is, however, obviously due to the application of the green color over the yellow stole, which is rendered in a Fe-base ochre. Contrarily, the green color of the St. Alexios icons indeed stands out as it contains far more chromium in comparison to the green tones of the other icons; additionally, the corresponding spectrum shows titanium, an element not detected in the other pertinent colors (Figure 16).

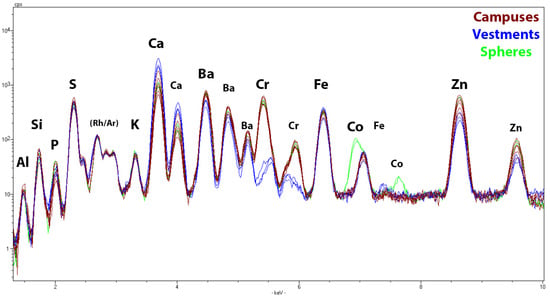

Figure 16.

XRF spectra from the blue-colored areas of the studied icons: pale-blue campuses (brown spectra), dark-blue vestments (blue spectra), and blue spheres (green spectra). All spectra were collected with a 15 kV/30μA set up and are here displayed in logarithmic scale.

Blue tones were used to render some of the figures’ vestments, the spheres held by the Archangels, and the campuses (i.e., backgrounds) of the icons (with the sole exception being the St. Alexios icon, where the background is gilded). p-XRF analyses revealed interesting compositional trends in the corresponding spots and employment of radically different pigment mixtures between the different pictorial elements. In detail, all spectra collected from blue campuses show intense Cr elemental peaks, which are accompanied by enhanced Zn and Ba elemental peaks (Figure 17). Contrarily, the XRF spectra from the dark blue-colored vestments show no chromium, and less zinc, along with notably more intense Ca peaks; these findings reveal that the color used for rendering blue vestments is radically different from that used for the blue campuses (Figure 17). The detection of chromium in blue-colored areas may, at first sight, appear irrelevant, as this element is primarily associated with green and yellow pigments such as chrome oxide and lead chromate, respectively. Nevertheless, since the corresponding p-XRF spectra show enhanced Fe elemental peaks, employment of Prussian blue may be inferred; in addition, the spectra show no presence of chemical elements typically associated with other common blue pigments like, e.g., copper (Cu-based blues like azurite and phthalocyanine) and cobalt (Co-blue). In this view, it appears that Kontoglou used either Prussian blue, indigo, or artificial ultramarine to render the campuses and vestments blue, yet for the secure identification of the exact blue compound, additional analysis is certainly needed. As for the detection of Cr in the spectra collected from the campuses, the identification of this particular element indicates chromium oxides too, and it is true that examples of 20th-century paintings exist, where the use of mixtures of blue pigments with viridian green has been attested [31]. Finally, Co was detected in the blue spheres held by both Archangels (Figure 17); the detection of this particular element clearly shows employment of Co-blue, a vivid blue pigment that was widely used by painters in the 20th century [60,61].

Figure 17.

XRF spectra from the black lettering on the scrolls held by St Alexios and the Prophets David, Jeremiah, and Isaiah; 15 kV/30 μA spectra, logarithmic scale. Chlorine-containing areas.

Finally, of particular interest are the results of the analysis of the dark/black lettering on the scrolls held by the Prophets David, Jeremiah, and Isaiah, as well as by St Alexios (Figure 17 and Table 2). In case of the lettering of Prophet David’s and St Alexios’ scrolls, the spectra show enhanced Fe elemental peaks, along with notably high Mn peaks (Figure 17); these characteristics clearly suggest that an umber-type pigment has been used in these cases. Contrarily, the rather low (in comparison to the former spectra) intensities of Fe peaks documented in the spectra from the Prophet Jeremiah and Isaiah’s scrolls allow for the exclusion of the employment of a Mars black pigment (artificial Fe3O4) [50]; hence, use of a C-based black component is assumed [62].

4. Discussion

Despite the fact that the employed methodology did not allow for the identification of the painting materials used by Kontoglou, the rigorous processing and assessment of the p-XRF data lead to certain important findings. First of all, the analytical data presented herein clearly show that Kontoglou used different materials to paint the icons in consideration. On the one hand, the St. Alexios icon stands out, as it is the only one that bears gilded decorations (the halo and background); interestingly, the corresponding XRF spectrum (Figure 15, Table 2) shows only minor copper and no silver elemental peaks, thus suggesting employment of high-purity gold leaves [63]. Additionally, the same icon is the only one to bear titanium white as the primary white pigment used for rendering flesh tones, as suggested by the corresponding p-XRF data (Table 2), while Cr is detected in the flesh tones of this icon, thus suggesting the use of viridian green—a notable differentiation from the compositions containing the same pictorial elements of the other icons. The fact that Ti-white was used in only one out of the seven icons (and in this case scarcely) is considered evidence of the rather slow introduction of Ti-white in the Greek painting material market and the persistent use of competitor colors. In fact, results of other pertinent studies conducted on contemporary Greek paintings corroborate this assumption [24]. On the other hand, the four Prophet icons show notable differences—in terms of painting materials—from the two Archangel icons. A characteristic example is the color used to paint the flesh underpaint and highlights: the two Archangel icons show considerably higher Zn and Ba elemental peak intensities in comparison to the Prophets’ flesh underpaints and highlights (Table 2, Figure 12 left). Similarly, notable differences as regards Zn content are documented in the colors used to paint yellow haloes (Figure 15) and the red marginal lines (Figure 12 left). The presence of enhanced Zn in many of the colors used to paint the Archangels icons is regarded as a rather important finding; the reader is reminded that all these icons were painted in the same year [1954]; hence, the employment of different materials may suggest that the Archangel icons were painted in a different period from the Prophet icons.

Notable differentiations are also observed in the composition of the paints used to render the lettering on the scrolls, as well as between other pictorial elements of the icons. The reader is urged to evaluate these findings on the basis of the strict technical background of Kontoglou’s paintings. It is emphasized that within the framework of Eastern Orthodox Christian painting, there are rules and dictations (on both a painting material and style basis) that must be followed by painters in order for their works to be considered proper. In addition, this is evident from the content of Kontoglou’s “Ekphrasis” painting manual, which was indeed a detailed and handy guide for painters.

In this view, it is indeed notable that at least three trends—in terms of painting material use—were documented within the rather small corpus of Kontoglou paintings that were studied in the framework of the current work. To the authors’ view, this fact most probably reflects the procurement of pigments/paints from different suppliers and/or procurement of commercial pigments that were erroneously labeled/adulterated. Moreover, the fact that Kontoglou was not consistent in using standard materials is reflected even in less important details of his paintings like the lettering of the scrolls, and this might be considered an indication of his devotion to his primary target, which was certainly to paint in line (in terms of style and content) with the tradition. At this point, however, this statement is merely an assumption, and analysis of additional Kontoglou’s works is certainly needed in order to assess its validity.

It has been already argued that the employed methodology suffers from certain limitations like, e.g., the inability to identify specific compounds and the X-ray penetration depth, which did not allow for the analysis of single paint layers. Nevertheless, despite its limitations, the current study sets the foundations for future pertinent studies, and the results obtained allowed for proper planning. Indeed, since in many cases the employed methodology does not lead to conclusive results, it is imperative to employ additional analytical tools. In particular, it is considered essential to employ a molecular characterization technique like Raman, which is complementary to XRF and could allow for the identification of specific compounds. Additionally, technical photography and in particular infrared reflectography (IRR), along with false-color IRR, will contribute considerably towards assessing both the nature of the employed pigments and the technical details of the paintings (e.g., employment of preliminary drawings, brushstrokes, etc.). These considerations have already formed the basis of the planning of future expeditions to Lakonia, aiming at a more thorough and in-depth investigation of existing portable Kontoglou paintings.

5. Conclusions

The significance of the present preliminary study lies primarily in the fact that it represents the first attempt to examine the materials of selected Kontoglou icons. As such, it is of great importance, as it serves as the foundational step towards an in-depth examination of the materials and techniques employed by Kontoglou in his paintings. The analytical data documented herein, do allow for an assessment of the materials used for painting the icons in consideration, although in most of the cases they cannot lead to sound identifications of given components. The absence of varnish in the majority of these icons is an interesting finding, as the application of relevant protective layers only on gilded areas of the paintings is explicitly dictated in the painting manual compiled by Kontoglou himself [13]. Τhe analytical data revealed that all seven icons were painted using modern, commercially available colors, as substances containing elements like zinc, barium, andor Cr were consistently detected in the majority of the analyzed paint layers. However, data revealed very scarce use of Ti-white, which probably reflects the limited distribution of this pigment in the Greek market of those times, a finding in line with the results of recent pertinent studies conducted on European paintings.

Variations in the identified materials suggest possible differences in palette choices, which may in turn reflect different moments of production—even among the six icons dated to 1954 (Prophets and Archangels). While this observation points toward potential chronological distinctions, additional contextual and comparative evidence would be necessary to confirm this interpretation. Additionally, this finding clearly suggests that Kontoglou used materials of different origin, and further study as for his sources is certainly needed. It is worth noting that Emeritus Professor Nikos Zias characterizes the period between 1950 and 1960 as “the years of great ecclesiastical painting production” [7], when Kontoglou refined his methods and focused on the restoration of Orthodox iconography while maximizing his output. The current study is consistent with this characterization and suggests that Kontoglou did not rely on a fixed set of pigments; rather, he appears to have used a variety of painting materials, presumably originating from various sources. Ultimately, the findings of the current study shed light on the methodological aspects of the pertinent research field and contributed considerably towards establishing a detailed protocol for future studies. In fact, it is imperative that future research shed more light on the materials and techniques employed by Kontoglou, so as to allow for sound conservation strategy planning. To this end, the employment of additional analytical techniques such as μ-Raman, FTIR, and IRR will certainly contribute considerably.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8120528/s1. Figure S1: The studied icons and the corresponding points of XRF analyses (numbered).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and G.P.M.; methodology, C.K. and G.P.M.; software, G.P.M.; validation, F.A. and G.P.M.; formal analysis, F.A.; investigation, F.A., G.P.M. and C.K.; resources, C.K.; data curation, G.P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A. and G.P.M.; writing—review and editing, G.P.M. and C.K.; visualization, F.A. and G.P.M.; supervision, C.K.; project administration, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Acknowledgments

F.A. would like to express her gratitude to Eleni Filippaki for her valuable guidance and support throughout this research. F.A. is also deeply thankful to conservator Asimina Bellou for her assistance in the field. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Head of the Ephorate of Antiquities in Laconia, Evaggelia Pantou, for granting permission to analyze the icons. Also, His Eminence, the Bishop of Monemvasia and Sparta, Eustathios, the Abbot of the Forty Martyrs Monastery, Archimandrite Efraim, and the Abbot of the St. Anargyroi Monastery, Archimandrite Gregorios, are sincerely thanked for their kind cooperation and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chatzidakis, M. Greek Painters After the Fall (1450–1830); Centre for Neo-Hellenic Research, National Hellenic Research Foundation: Athens, Greece, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gravgaard, A.M. Change and Continuity in Post-Byzantine Church Painting. Cah. L’Institut Moyen-Âge Grec Lat. 1987, 54, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzidaki, N. Icons. The Velimezis Collection: Scholarly Catalogue; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 1997; p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- Graikos, N. Academic trends of ecclesiastical painting in Greece during the 19th century. In Cultural and Iconographic Issues; CopyCity desktop: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evseeva, L.M.; Cook, K. A History of Icon Painting: Sources, Traditions, Present Day; Grand-Holding Publishers: Athens, Greece, 2005; p. 287. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/A_History_of_Icon_Painting.html?hl=el&id=fDYOOAAACAAJ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Chatzifotis, I.M. Fotis Kontoglou—His Life and Work; Grammi: Athens, Greece, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Zias, N. Introduction. In Fotis Kontoglou: Reflections of Byzantium in the 20th Century; Hellenic Cultural Foundation: Athens, Greece, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kounenaki, R. Chronology of F. Kontoglou. In Greek Painters: El Greco, Theophilos, Kontoglou, Papaloukas; Kathimerini: Athens, Greece, 1996; pp. 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Frantziskaki, F.K. The World of Kontoglou Painted on a Fresco. Zygos, September 1978; pp. 10–12.31. [Google Scholar]

- Zias, N. Fotis Kontoglou; Alpha Bank: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kontoglou, F. National Gallery. Available online: https://www.nationalgallery.gr/artist/kontoglou-fotis/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Konstantinidis, T. Fotis Kontoglou: The Author, the Painter, the Greek. In Fotis Kontoglou, en Ikoni Diaporeuomenos: One Hundred Years Since His Birth and Thirty Since His Passing; Akritas: Athens, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kontoglou, F. Ekphrasis of Orthodox Iconography; Astir: Athens, Greece, 1993; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G. The Balpis Expansion of the Technical Part of the Hermeneia Painting Manual by Dionysius of Fourna. Stud. Conserv. 2024, 69, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysios of Fourna. Hermeneia of the Art of Painting; Papadopoulos-Kerameus, A., Ed.; Spanos: Athens, Greece, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Markozanis, N.I. The “Hermeneia of the Art of Painting” by Dionysios of Fourna and the Western Technological Tradition of the Middle Ages; Armos: Athens, Greece, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y. On the blue and green pigments of post-Byzantine Greek icons. Archaeometry 2020, 62, 774–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1956; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Karydis, C. Techniques & Materials of Paintings: Portable Icons & Panels. General Principles of Preventive Conservation; Ion Editions: Athens, Greece, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlopoulos, D. The Secret Garden of the Icons of Fotis Kontoglou. Them. Archaeol. 2017, 1, 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ene D-Vasilescu, E. Twentieth Century Developments in European Icon Painting. IKON 2016, 9, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, A. The ‘Generation of the Thirties’ in art: Cold War cultural politics and modern painting in Greece. In Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalothanasis, N. Theophilos and the Generation of the Thirties (again). In Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesidis, S.; Kaminari, A.A.; Alexopoulou, A.G.; Zacharias, N. Preliminary investigation of the painting technique of Thalia Flora-Karavia (1871–1960): The ‘Paris’ case study. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 71, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romantzi, T.; Ganetsos, T.; Giakoumi, D.G.I. Katsigras Museum: In-Situ Measurements in Paintings by G. Gounaro. Archaeology 2021, 9, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulou-Athera, N.; Chatzitheodoridis, E.; Terlixi, A.; Doulgerides, M.; Serafetinides, A.A. Reconstructing the colour palette of the Konstantinos Parthenis’ burnt paintings. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 201, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, A.-C.; Dritsa, V.; Cheilakou, E.; Valavani, E.; Margariti, C.; Efthimiou, K.; Koui, M. Non-invasive Identification of the Pigments and Their Application on Theophilos Hatzimihail’s Easel Paintings. In 10th International Symposium on the Conservation of Monuments in the Mediterranean Basin: Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards and Sustainable Preservation; Koui, M., Zezza, F., Kouis, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 217–231. ISBN 978-3-319-78093-1. [Google Scholar]

- Molari, R.; Appoloni, C.R. Pigment analysis in four paintings by Vincent van Gogh by portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2021, 181, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, B.A.; van den Berg, K.J.; Gerretzen, J.; Dik, J. The white of the 20th century: An explorative survey into Dutch modern art collections. Herit. Sci. 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Snickt, G.; Martins, A.; Delaney, J.; Janssens, K.; Zeibel, J.; Duffy, M.; McGlinchey, C.; Van Driel, B.; Dik, J. Exploring a hidden painting below the surface of René Magritte’s Le portrait. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 70, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizun, D.; Kurkiewicz, T.; Szczupak, B. Exploring Liu Kang’s Paris Practice (1929–1932): Insight into Painting Materials and Technique. Heritage 2021, 4, 828–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchieri, J.; Scialla, E.; D’Onofrio, A.; Sabbarese, C. Combining XRF, Multispectral Imaging and SEM/EDS to Characterize a Contemporary Painting. Quantum Beam Sci. 2023, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, S. Managing Conservation in Museums; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Reza, S.; Norlin, B.; Fröjdh, C.; Thungström, G. Signal-to-noise ratio optimization in X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for chromium contamination analysis. Talanta 2021, 230, 122236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, A. Effects of Different Binders on Technical Photography and Infrared Reflectography of 54 Historical Pigments. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2015, 6, 287–298. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=2067533X&AN=109383509&h=4dyUgHVjvkdqzif9xqgJ3lV0%2Bq5Xs0fXzh20id2QSua%2FZrTNgYcERi5h8UuRo52rb9Havx%2FsEPOz%2Fw11kkNSSA%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Stuart, B.H. Analytical Techniques in Materials Conservation; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, S.; Umney, N. Conservation of Furniture; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; p. 840. [Google Scholar]

- Measday, D.; Walker, C.; Pemberton, B. A Summary of Ultra-Violet Fluorescent Materials Relevant to Conservation. Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material. Available online: https://aiccm.org.au/network-news/summary-ultra-violet-fluorescent-materials-relevant-conservation/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Larsen, R.; Coluzzi, N.; Cosentino, A. Free xrf spectroscopy database of pigments checker. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 7, 659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Daniilia, S.; Bikiaris, D.; Burgio, L.; Gavala, P.; Clark, R.J.H.; Chryssoulakis, Y. An extensive non-destructive and micro-spectroscopic study of two post-Byzantine overpainted icons of the 16th century. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2002, 33, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P. Pigments and Various Materials of Post-Byzantine Painting; University of Ioannina: Ioannina, Greece, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Asvestas, A.; Gerodimos, T.; Anagnostopoulos, D.F. Revealing the Materials, Painting Techniques, and State of Preservation of a Heavily Altered Early 19th Century Greek Icon through MA-XRF. Heritage 2023, 6, 1903–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y.; Papadopoulou, V. On The Grounds of Post-Byzantine Greek Icons. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou, S.; Daniilia, S. Material aspects of icons. A review on physicochemical studies of Greek icons. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, S.; Bui, D.W.; Canler, T.; Carnevali, A. Strontium in barium sulphate as a discriminating factor in the forensic analysis of tool paint by SEM/EDS. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 331, 111127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, E.; Locardi, F. Strontium, a new marker of the origin of gypsum in cultural heritage? J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, M. Titanium white. In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; Archetype Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1997; pp. 295–355. [Google Scholar]

- Morozova, E.; Kadikova, I.; Pisareva, S. Titanium dioxide whites in xx century works of art: Occurrences and composition study. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 13, 1553–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou, D.; Malletzidou, L.; Zorba, T.; Beinas, P.; Karapanagiotis, I.; Pavlidou, E. Characterization of a two field icon of Virgin Mary ‘eleousa’ (19th century). AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2075, 200004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G. Pigments—Iron-based red, yellow, and brown ochres. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y. On the Red and Yellow Pigments of Post-Byzantine Greek Icons. Archaeometry 2021, 63, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastaugh, N.; Walsh, V.; Chaplin, T.; Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008; p. 958. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Filippaki, E.; Bassiakos, Y.; Beltsios, K.G.; Papadopoulou, V. Probing the birthplace of the “Epirus school” of painting: Analytical investigation of the Filanthropinon monastery murals—Part I: Pigments. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 2821–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristache, R.A.; Sandu, I.C.A.; Simionescu, A.E.; Vasilache, V.; Mariabudu, A.; Sandu, I. Multi-analytical study of the paint layers used in authentication of icon from XIXth century. Rev. Chim. 2015, 66, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Karapanagiotis, I.; Minopoulou, E.; Valianou, L.; Daniilia, S.; Chryssoulakis, Y. Investigation of the colourants used in icons of the Cretan School of iconography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 647, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civici, N.; Demko, O.; Clark, R.J.H. Identification of pigments used on late 17th century Albanian icons by total reflection X-ray fluorescence and Raman microscopy. J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 6, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holclajtner-Antunović, I.; Stojanović-Marić, M.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Žikić, R.; Uskoković-Marković, S. Multi-analytical study of techniques and palettes of wall paintings of the monastery of Žiča, Serbia. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 156, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilia, S.; Tsakalof, A.; Bairachtari, K.; Chryssoulakis, Y. The Byzantine wall paintings from the Protaton Church on Mount Athos, Greece: Tradition and science. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanidis, A.; Garcia-Guinea, J.; Strati, A.; Gkimourtzina, A.; Papoulidou, A. Byzantine wall paintings from Kastoria, northern Greece: Spectroscopic study of pigments and efflorescing salts. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boracchi, B.G.; Ferrer, E.-J.S.; Gnemmi, M.; Falchi, L.; Izzo, F.C.; Sandu, I.C.A. A multi-analytical study of early twentieth-century industrially produced cobalt blue paints from Edvard Munch’s studio. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Monet’s Palette in the Twentieth Century: ‘Water-Lilies’ and ‘Irises’. Natl. Gallery Tech. Bull. 2007, 28, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini, E.; Siracusano, G.; Maier, M.S. Spectroscopic, morphological and chemical characterization of historic pigments based on carbon. Paths for the identification of an artistic pigment. Microchem. J. 2012, 102, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y.; Papadopoulou, V. On the Metal-Leaf Decorations of Post-Byzantine Greek Icons. Archaeometry 2018, 60, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).