1. Introduction

Technology and fashion have always gone hand in hand. Whether it is innovative materials, new production methods, or changing ways of perceiving the style of clothing, these two spheres are constantly intertwined. Historical dresses are not merely old clothes but complex cultural artifacts, involving materials, construction, trimming, and context. In this study, we focus narrowly on dress silhouette as a quantifiable dimension, while acknowledging that it represents only one aspect of dress history [

1].

The function of dress silhouettes is to show how different shapes can emphasize or conceal certain parts of the body, which is useful in design, styling, or choosing dresses according to the figure.

Research on dress in the cultural heritage domain is often laborious, requiring detailed visual comparison across large and heterogeneous datasets. While historians and costume specialists already identify dress silhouettes with speed and accuracy, the challenge arises when collections expand to thousands of images, such as in museum databases or digital archives. In these contexts, automated image-sorting procedures can assist by providing reproducible baselines for preliminary grouping, accelerating cataloging, and enabling large-scale comparative studies that would otherwise be prohibitively time-consuming. Such tools do not replace expert interpretation, but complement it by reducing repetitive labor and highlighting ambiguous cases for further scholarly analysis. This practical relevance has been noted in digital heritage research, where scalable methods are increasingly required to manage visual data at scale [

2,

3].

In recent years, for the objective assessment and analysis of historical dresses, digital image processing methods, such as computer vision techniques, algorithms for automatic recognition of visual features, and three-dimensional reconstructions [

4], have been developed. These approaches allow for a more accurate and systematic description of dress silhouettes and their details, facilitate comparative analysis between different eras, and create prerequisites for a new type of analysis that unites humanitarian and technological research [

5].

The classification of visual forms of historical dress silhouettes requires a combination of image processing techniques, feature extraction, and machine learning. The task of systematizing dress silhouettes includes contour analysis, data dimensionality reduction, and classification algorithms.

ContourCNN, proposed by Zhang et al. [

6], is a deep neural network specialized in processing contour data. The model uses circular convolutional layers and prioritization pools that allow the preservation of local geometric features such as asymmetry, smoothness, and shape variation. This approach is suitable for tasks where shape is a key classification feature, as is the case with historical dress silhouettes. A disadvantage of ContourCNN is that it requires relatively large training sets and significant computing power, which makes it more difficult to apply to limited data, such as those often found in historical research. In the study of Mileni [

7], based on the Fashion-MNIST dataset, the effectiveness of classical algorithms such as k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), support vector machine learning (SVM), and principal component analysis (PCA) in classifying dress images is demonstrated. PCA is used to reduce the dimensionality of the input data, preserving the maximum amount of information, and SVM shows high accuracy in optimizing the kernel (the separating function). These techniques are also applicable to the analysis of dress silhouettes, where the visual structure of the recognized object in the image is key. A major limitation of this development is that Fashion-MNIST works with pre-structured images and does not take into account the complexity of real contours and variations in dress silhouettes.

Singh et al. [

8] propose a method for classification by contour matching. The authors extract geometric features such as normalized radii, centroids, and local variations, which are used to create a vector representation of the shape. This approach allows for objective classification of complex visual structures, including dress silhouettes, and emphasizes the importance of formal indices of symmetry, smoothness, and volume distribution. A limitation of this method is that it does not include automated feature selection, which can lead to overfitting or loss of relevant information.

Compared to the considered data processing methods from the available literature, extracted contour indices and automated selection through sequential evaluation methods such as ReliefF, FSRNCA, and SFCPP can be used [

9,

10,

11], as well as combined dimensionality reduction through principal components and latent variables [

12,

13], which provides higher objectivity, adaptability, and interpretability in the classification of historical dress silhouettes.

The main problem addressed is the absence of accessible, reproducible tools for large-scale comparative analysis of silhouettes in digital heritage contexts. Dress historians already identify silhouettes with speed and accuracy; our method is intended to support them in contexts where datasets are too large for manual classification, or where preliminary grouping can accelerate expert interpretation. They are more often laborious and require significant time, resources, and the specialized training of researchers. In addition, they are subjective, since the analysis of visual characteristics and the classification of dress silhouettes depend largely on the individual interpretation of the person. This leads to inconsistency and makes it difficult to reproduce the results across different research teams.

At the same time, the interpretive traditions of dress history, including visual literacy, iconographic comparison, and contextual reading, remain indispensable. Our approach seeks to integrate these traditions with computational tools, translating visual literacy practices into quantifiable indices that can be systematically compared.

The purpose of this study is to explore how machine learning can provide reproducible baselines for silhouette classification in large digital datasets. The method is intended to support, not replace, expert interpretation, offering scalable tools for museum cataloging, digital heritage projects, and educational platforms.

The study focuses on Western European fashion (primarily of France and Britain), where dress silhouette changes were most pronounced. Categories such as Regency, Romanticism, Victorian sub-periods, and Belle Époque are used to reflect established dress history scholarship. We exclude theatrical costume, fancy dress, and re-drawings to ensure the dataset reflects fashion history rather than derivative representations.

To guide the study, three research questions were formulated: (1) Can machine learning methods provide reproducible baselines for classifying historical dress silhouettes across different periods? (2) Which shape indices are most informative for distinguishing silhouettes, and how do they correspond to visual literacy practices in dress history? (3) How does the accuracy of different classifiers vary across historical periods, and what does this reveal about the potential and limits of automation in cultural heritage research? These questions connect the theoretical rationale with the methodological approach and frame the scope of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

The images of historical dresses were obtained from Wikimedia Commons (

https://www.wikimedia.org, accessed on 24 August 2025). For isolation and standardization, garments were extracted from the images using the Copilot online artificial intelligence tool (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) (

https://copilot.microsoft.com/ (accessed on 24 August 2025)). After background removal, the silhouettes were presented in a standardized frontal view to ensure consistency. Importantly, no geometric transformation of perspective was applied; contours were extracted directly from the available images. Minor artifacts (e.g., cropping errors, inclusion of hands, or non-frontal poses) were acknowledged as limitations. All of the dresses are presented as

Supplementary Material.

Backgrounds were removed using the online tool

Remove.bg (accessed on 23 August 2025), and the processed images were saved in *.PNG format. The dataset was assembled with selection criteria emphasizing visual clarity, identifiable historical period, and sufficient resolution for contour extraction. It includes paintings, engravings, and museum photographs, each carrying distinct interpretive biases. Metadata was added to record source type, date, and provenance, and images with excessive cropping errors, obscured silhouettes, or unclear poses were excluded to improve validity.

Table 1 shows the historical fashion periods and the number of images used from each of them, divided by periods and subperiods (Empire, Romanticism, Victorian era, Art Nouveau). The total number of images is 270.

2.1. Basic Dress Silhouettes Used

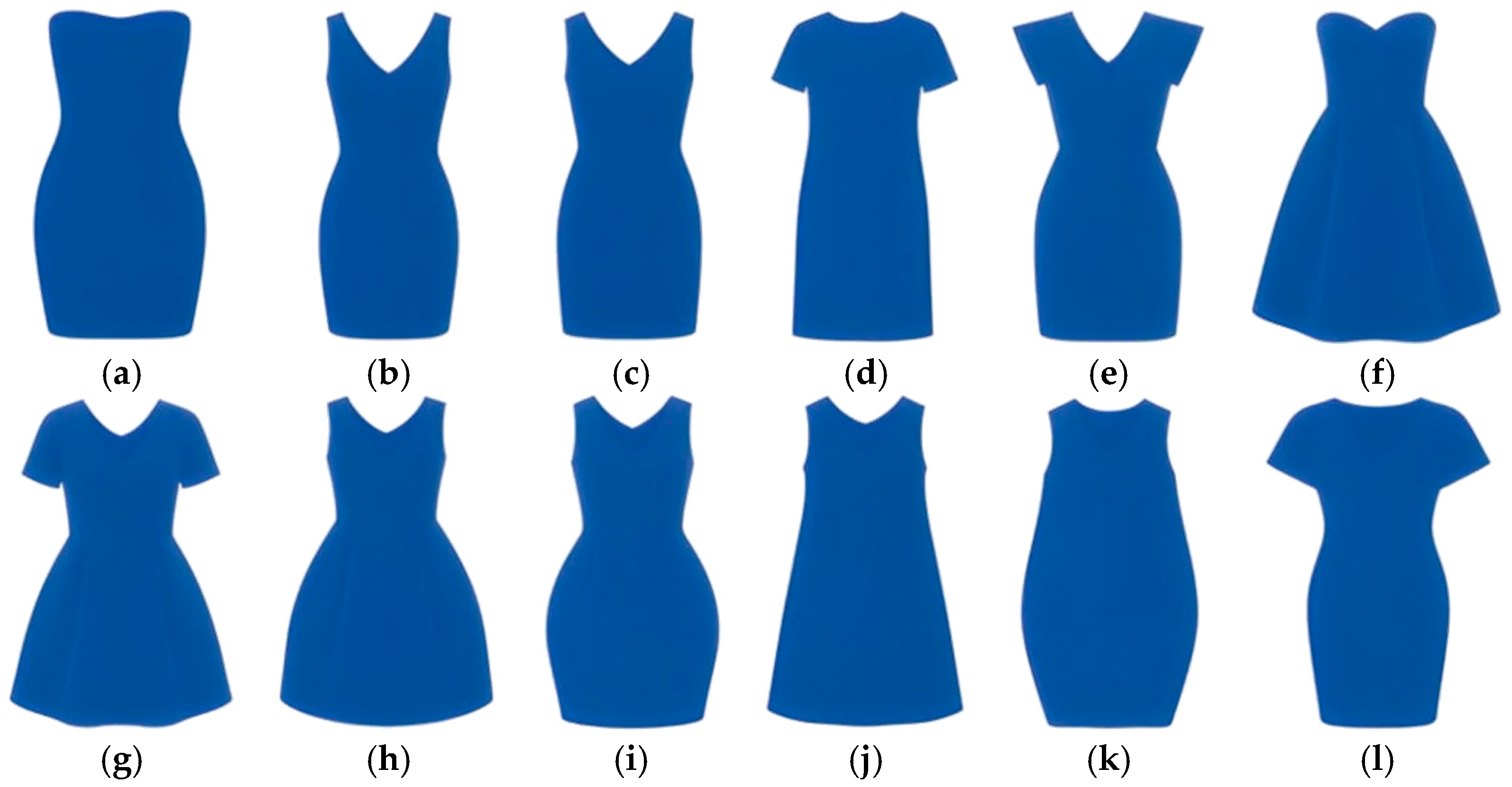

Basic silhouettes presented in the available literature [

14,

15] were used. These silhouettes are presented in

Figure 1. They are arranged in 12 different styles. Each silhouette is indicated by a code (e.g., S1, S2, etc.) and a brief description of the shape.

To obtain shape indices via a centroid, algorithms proposed in the available literature [

15,

16] were used, with some modifications.

For an object in a binary image, the center of gravity, with coordinates

cx and

cy, is

where (

xk,

yk) are the coordinates of the pixels in the figure and

N is the number of pixels.

From the boundary pixels, a set

M of points is obtained:

The topmost point of the contour (minimum y) is selected and the contour is rotated to start from it. This ensures the same starting position for different images.

Since the number

M of contour points is different, a uniform sampling

ti (interpolation) is performed to exactly 100 points:

The new

x and

y coordinates are obtained by interpolation:

The new set of exactly 100 points along the contour thus obtained enters the formula for the radius

ri:

To make different shapes comparable (regardless of their size), the radii are normalized:

A vector of features

fi is created:

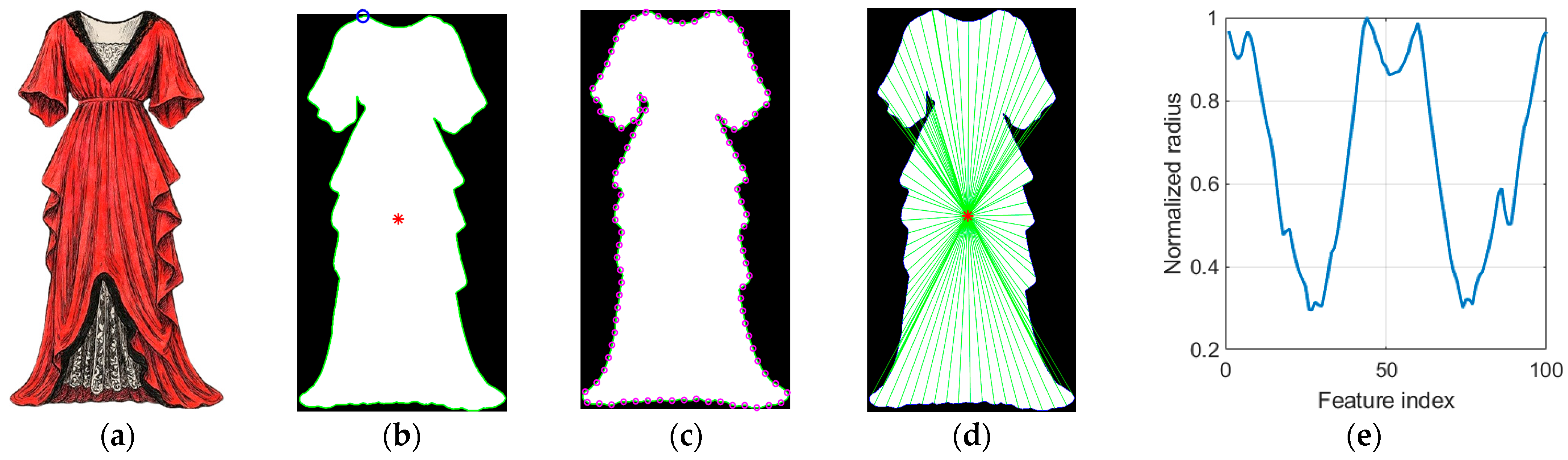

Figure 2 shows the stages of the algorithm for extracting features from an object in an image. The original image is loaded, on which the contours of the dress are detected, and the main points are marked—the center of gravity and the starting point of the contour. Then the contour is resampled to 100 evenly distributed points, which facilitates analysis and comparisons between different shapes. The last stage involves calculating normalized radii. These are values that describe the distance from the center of the object to each point of its contour, presented graphically.

From the obtained data in the feature vector (f), shape indices (FIx) are calculated [

17,

18,

19,

20] (Equations (8)–(22)).

FI1–FI4 capture asymmetry and volume distribution, while FI5–FI9 focus on local variation and smoothness.

FI1 is a local asymmetry at the beginning of the contour. It compares the first radii, sensitive to small distortions.

FI2 averages the upper contour radii, reflecting the overall shape in the upper silhouette.

FI3 is a contrast between the upper and lower halves. It is an indicator of vertical asymmetry.

FI4 is a comparison of areas. It reflects whether the upper part is more voluminous than the lower.

FI5 is a comparison of variations. It shows how uniform the shape is in different areas.

FI6 describes symmetry around the middle. It is sensitive to shifts or bulges.

FI7 is the smoothness of the contour. It measures how abrupt the changes are between adjacent points.

FI8 compares the middle part to the top. It shows whether the shape is expanding or contracting.

FI9 describes deviation from the center and detects local anomalies around the midpoint.

FI10 is a shape energy measure sensitive to large radii and emphasizes volume.

FI11 compares the edges of the contour to its center. Indicates whether the shape is wider at the edges.

FI12 is the distribution of the radii. If it is close to 1, the shape is symmetrical and uniform.

FI13 correlates the upper and lower halves of the object contour and indicates whether the shape is mirrored.

FI14 is the overall variation in the radii, an indicator of shape complexity.

FI15 is the ratio of edges to the center; it is similar to

FI11, but relative to the first and last points of the object contour in the image.

For readers less familiar with mathematical notation, these indices can be understood as quantifications of symmetry, smoothness, and proportional balance in dress silhouettes. Shape indices are calculated using the following formulas:

The reliance on silhouette is a methodological simplification. While it enables reproducible feature extraction, it does not capture other critical dimensions of dress history such as fabric, construction, or cultural symbolism. Our approach should therefore be understood as complementary to, rather than substitutive of, established methodologies.

2.2. Selection of Informative Form Indices

Shape indices are used as objective criteria for describing historical dresses. Three sequential evaluation methods—RReliefF, FSRNCA, and SFCPP—were applied for the selection of informative features.

RReliefF (Relief-Based Feature Selection): This method is robust to noise and nonlinear dependencies, which makes it suitable for selecting shape indices, since these features have sufficiently complex interrelationships [

9].

FSRNCA (Feature Selection for Regression via Neighborhood Component Analysis): This method optimizes feature weights and provides sparsity, which facilitates the discovery of informative shape indices in the presence of high interdependence [

11].

SFCPP (Subset Feature Selection Based on Pairwise Correlation and Performance): This method eliminates highly correlated indices and provides stable predictive power through cross-validation, which is important for data with many similarly shaped indices [

10].

2.3. Reducing the Volume of Data in Vectors of Form Indices

To reduce the volume of data in the vectors of selected shape indices, two methods were used: principal components and latent variables.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical method for reducing the dimensionality of data that transforms the original variables into new, uncorrelated principal components, ordered by the degree of explained variance. The main idea is to preserve the maximum amount of information with the minimum number of components, which facilitates visualization and improves the efficiency of machine learning models [

12].

Partial least squares regression (PLSR) is a method that combines features of regression and latent variable analysis by extracting new components (LVs) that maximize the covariance between the input and output data. Unlike PCA, which focuses only on the structure of the input data, PLSR also takes into account the dependence on the target variable, which makes it particularly suitable for predictive tasks with high collinearity [

13].

2.4. Classification Methods Used

The k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) method acts as an intuitive and efficient classifier that does not require prior training. In it, classification is performed by comparing the subject with the k-nearest neighbors in the training set, using a metric such as Euclidean distance. This approach is particularly suitable for tasks with well-defined classes but is sensitive to the dimensionality of the data [

21].

Support vector machines (SVMs) are a type of classifier that find the optimal hyperplane separating the classes with a maximum margin. The method is particularly effective for tasks with high dimensionality and few observations, allowing nonlinear classification using kernel functions. In this work, the kernel functions linear, RBF, and polynomial were used [

22].

Decision Tree: A decision tree is an interpretable model that uses a hierarchical structure of logical “if-then” rules to classify data. It is particularly useful for visualizing the decision-making process and for discovering relationships between features [

23].

The criteria accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are used to evaluate the performance of classifiers.

Accuracy is a measure of what proportion of all predictions are correct.

Precision determines, of those predicted positive, how many actually are positive.

Recall (sensitivity, completeness) determines, from all of the actual positives, how many are registered.

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Here, TP (True Positives)—correctly classified as positive; FP (False Positives)—incorrectly classified as positive; FN (False Negatives)—incorrectly classified as negative; TN (True Negatives)—correctly classified as negative.

2.5. Algorithm for Clustering Historical Dress Silhouettes

Table 2 presents the algorithm for grouping historical dress silhouettes. The algorithm for classifying historical dress silhouettes consists of four stages, which include data preparation, machine learning, and visualization. At the beginning, data for standard and historical dress silhouettes are loaded, from which informative features are extracted, serving as the basis for classification. Then the data is divided into a training and a test set. At the classification stage, three different classification models are trained—k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), support vector machine learning (SVM), and decision tree—which determine which class (to which of the standard silhouettes) the silhouettes in the test set belong to. To assess the effectiveness of each classification model, 10-fold cross-validation is applied, accuracy metrics are calculated, and confusion matrices are visualized, showing the errors made. Finally, the results are presented graphically by reducing the dimensionality with PCA through a two-dimensional visualization of the classifications in order to compare the different classification models.

The following chapter presents the results of the analysis, focusing on both quantitative outcomes and interpretive discussion.

3. Results and Discussion

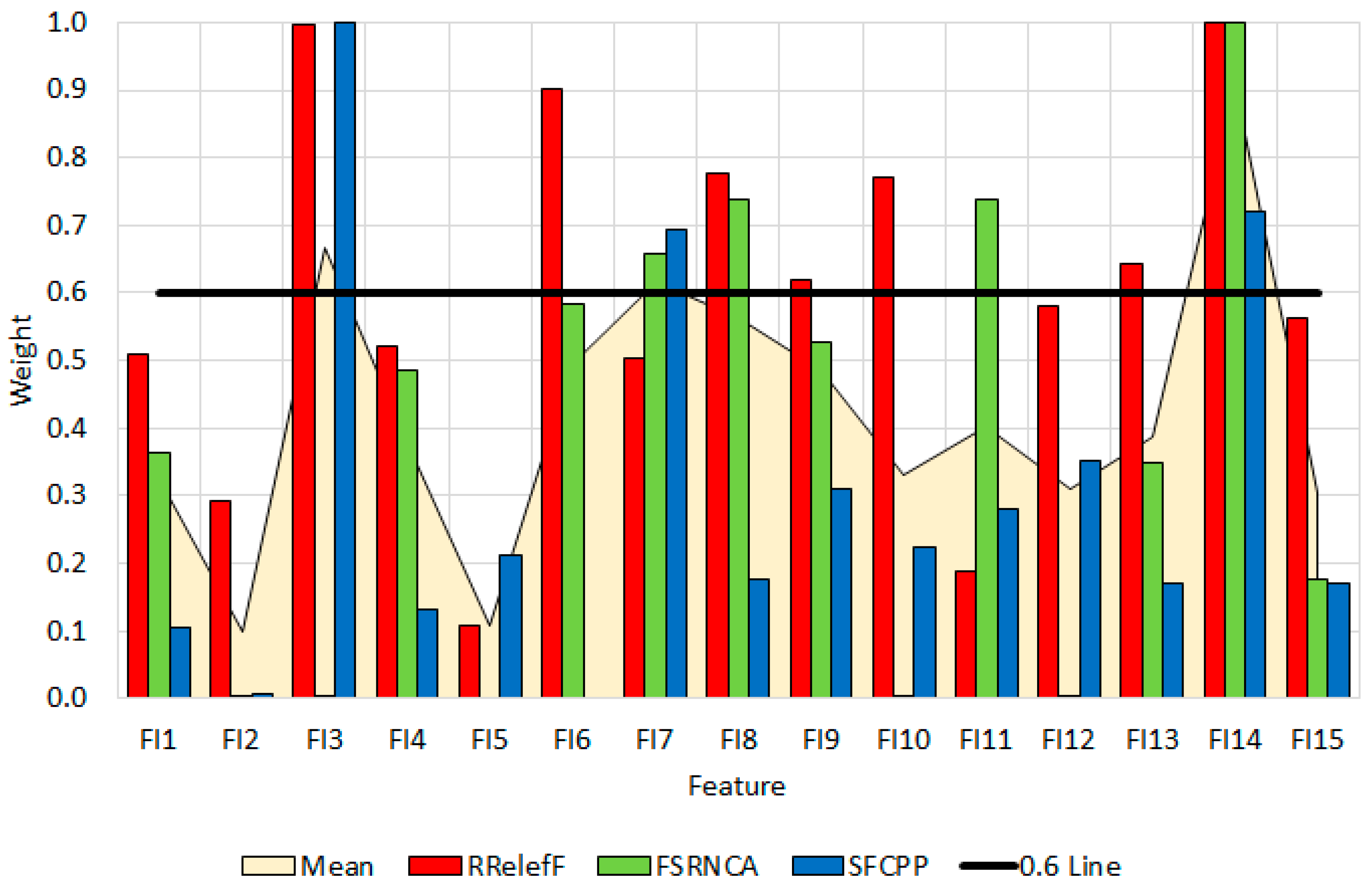

Figure 3 shows the results of the selection of informative shape indices. Based on the results obtained, the most significant feature is FI14, which reaches maximum values in RReliefF (1.00), FSRNCA (1.00), and SFCPP (0.72), and has an average value of 0.91. FI3 also shows high values in RReliefF (1.00) and SFCPP (1.00), with an average value of 0.67. FI7 exceeds the threshold of 0.6 in FSRNCA (0.66) and SFCPP (0.69), and has an average value of 0.62, which indicates its constant significance across the different selection methods. FI8 also approaches the threshold with values of 0.78 (RReliefF) and 0.74 (FSRNCA), although SFCPP evaluates it lower (0.18), and the average value is 0.56. FI9 reaches 0.62 in RReliefF and has moderate values in FSRNCA (0.53) and SFCPP (0.31). FI10 is above the 0.6 threshold only in RReliefF (0.77). FI6 reaches 0.90 in RReliefF and 0.58 in FSRNCA, which puts it close to the 0.6 threshold and makes it significant, especially for local dependencies. FI13 exceeds the 0.6 threshold in RReliefF (0.64), with moderate values in the other methods. FI11 is significant only in FSRNCA (0.74), indicating sensitivity to regularized selection. The remaining traits—FI1, FI2, FI4, FI5, FI12, and FI15—do not exceed the 0.6 threshold in any method and can be considered less significant. The features FI3, FI7, and FI14, which have been assessed as important by more than one method, are suitable for building reliable and interpretable classification models.

Table 3 presents the informative indices of the shape, depending on the method for their selection. It can be seen that the RReliefF method identifies the largest number of informative features—FI3, FI6, FI8, FI9, FI10, FI13, and FI14—which indicates its sensitivity to local dependencies in the data. FSRNCA, in turn, selects a more limited set of features—FI7, FI8, FI11, and FI14—which reflects its regularized and more structured evaluation logic. The SFCPP method marks as significant only FI3, FI6, and FI14, which suggests a stricter selection criterion based on probabilistic dependencies. FI14 is selected in all methods. “+” sign denotes that the feature is informative.

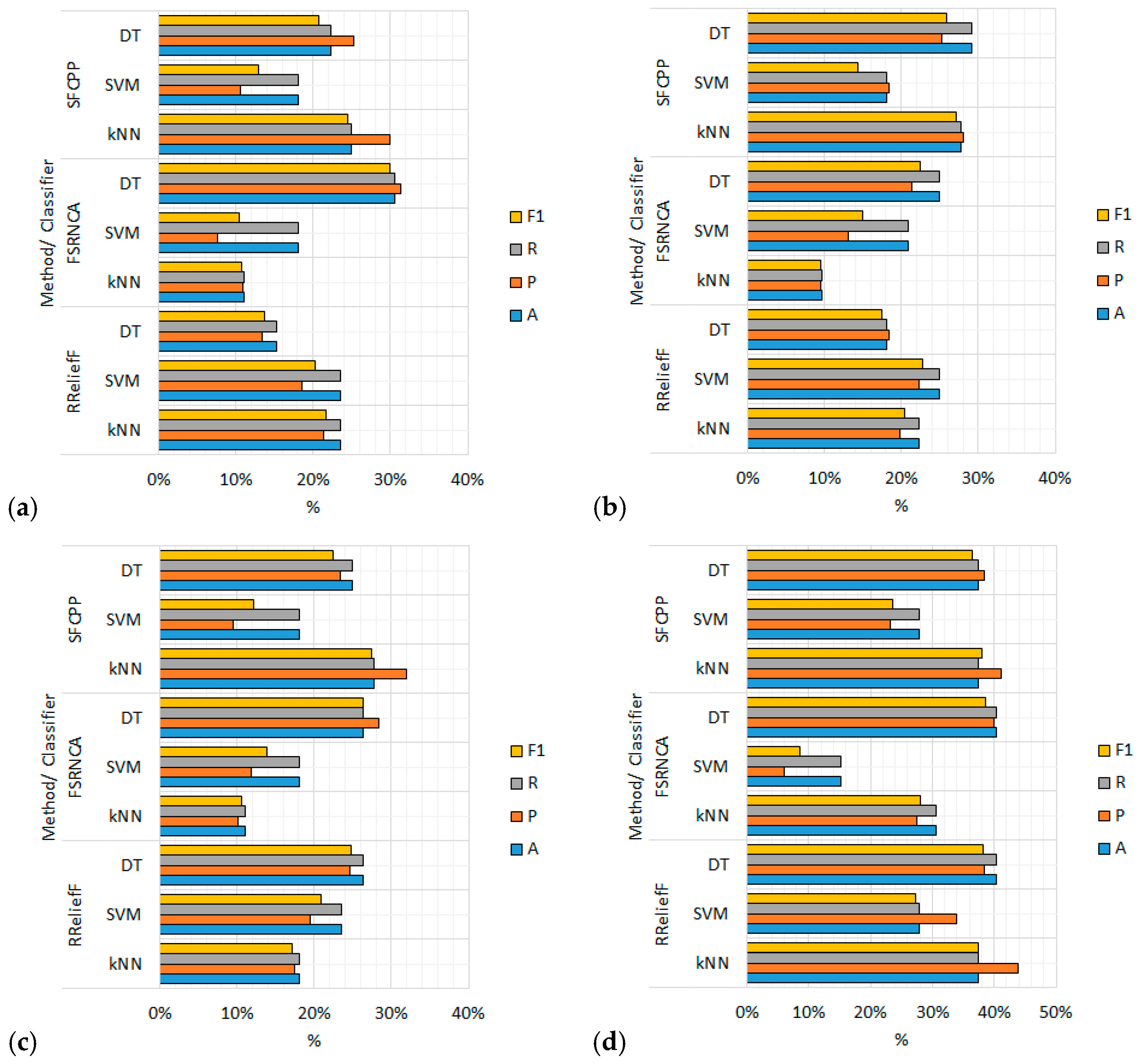

Figure 4 visualizes the results of classification with k-NN, SVM, and DT. Analysis of the classification results shows that the used classification models have different degrees of success in recognizing silhouettes from different historical periods. The data presented in the table show that the accuracy of the classifiers is generally low, which means that the models often make mistakes in relating historical dresses to the corresponding standard silhouette. Regarding the individual periods, the results vary significantly. For the Empire period (E), the accuracy is between 15.2% and 23.6%, with the best results achieved by the RReliefF feature selection method in combination with the kNN and SVM classifiers. This shows that even in the most favorable scenario, the models manage to correctly classify only about a quarter of the images. The situation is similar for the Art Nouveau period (N), where the accuracy varies between 9.7% and 29.1%. In Romanticism (R), the accuracy ranges from 11.1% to 27.7%. The highest accuracy is observed in the Victorian era (V), where the results reach 40.2%. This can be explained by the more distinct and diverse silhouettes characteristic of this long and visually rich period, which makes it easier for classifiers to recognize. Although the silhouettes of dresses from the Victorian era are classified most successfully compared to those from other historical periods, the results generally remain inconclusive.

The accuracy of the classification depends on both the shape index vector used and the classification model. The highest accuracy is obtained when using the index vector selected with the RRelefF method. It is necessary to perform a more in-depth analysis using a modified version of one of the classification models.

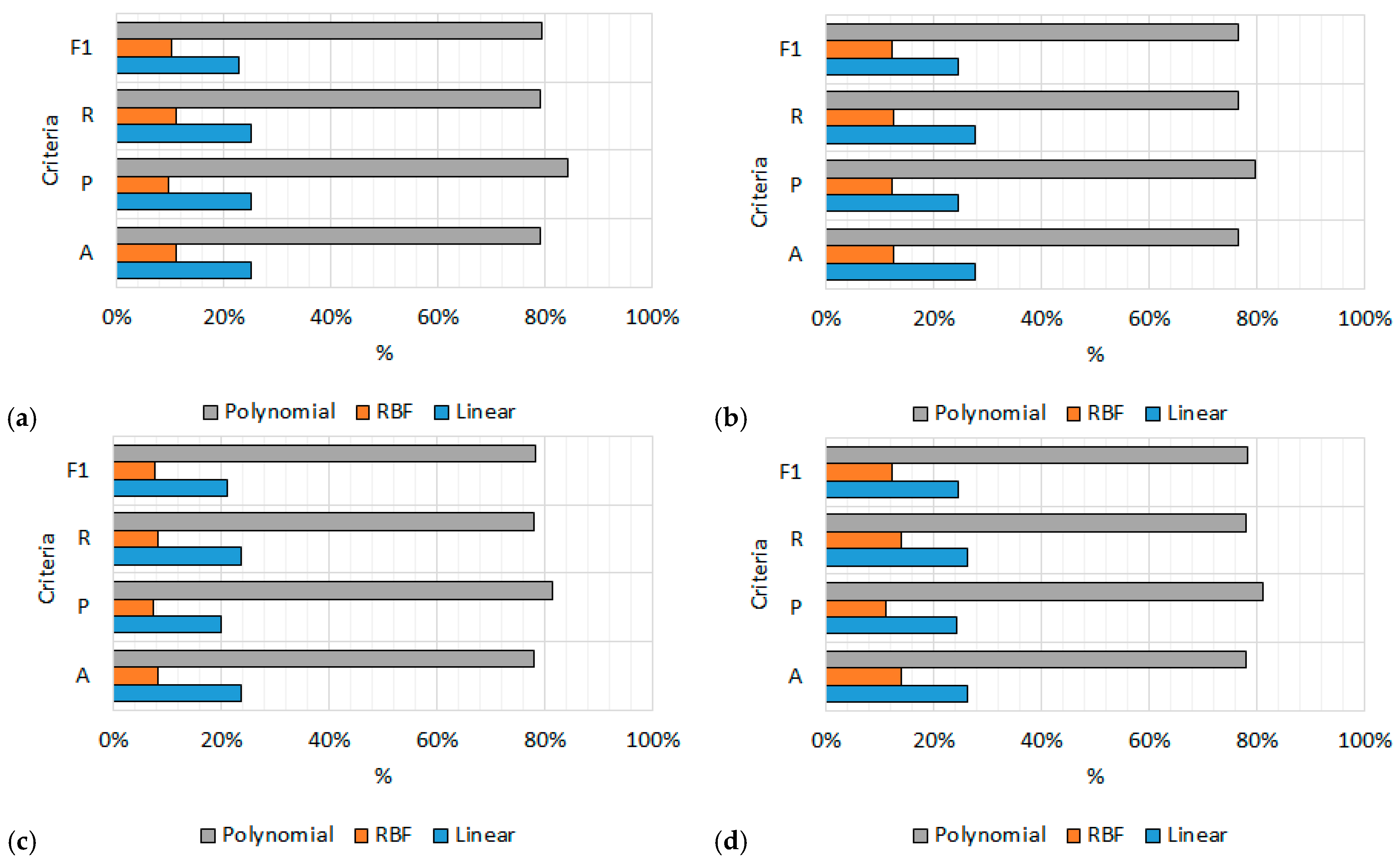

In this study, the effectiveness of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model in the classification of historical dress silhouettes was analyzed, testing three different kernels—linear, radial basis (RBF), and polynomial. The evaluation was made according to four metrics—accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 measure—for each of the four historical periods (Empire (E), Art Nouveau (N), Romanticism (R), and Victorian Era (V)).

Figure 5 visualizes the results of classification with SVM with three types of kernels. The results show a clear trend—when using the polynomial kernel, it significantly outperforms the others, regardless of the historical period. For example, for Empire, polynomial reaches an accuracy of 0.79, precision of 0.84, completeness of 0.79, and F1 measure of 0.79, which is more than three times higher than the results with the linear and RBF kernels. Similar values are observed for the Art Nouveau (accuracy 0.76–0.80), Romanticism (0.78–0.81), and Victorian eras (0.78–0.81). On the other hand, the RBF kernel shows the weakest results in all periods, with accuracy between 0.08 and 0.14 and F1 measure between 0.08 and 0.12. The radial basis function fails to adequately model the complexity of the visual data. The linear kernel performs moderately, with results around 0.24–0.28 for accuracy and F1 measure, indicating classification ability, but with nowhere near the efficiency of the polynomial. The differences in the results between the “default” SVM presented in the comparison of three different classification models and the “linear” SVM can be explained by the fact that the kernel variants allow for additional tuning and transformation of the data, which leads to different classification accuracy when the parameters of the linear kernel are tuned to the specific problem.

The highest values are observed in the Art Nouveau and Victorian eras, which is due to the more distinct visual characteristics of the silhouettes from these eras. This makes it easier for the classifier to recognize and assign to the correct category.

The results of the analysis show that the choice of kernel in SVM is important for achieving classification success. The polynomial kernel stands out as the most suitable for the task, while RBF does not offer adequate performance.

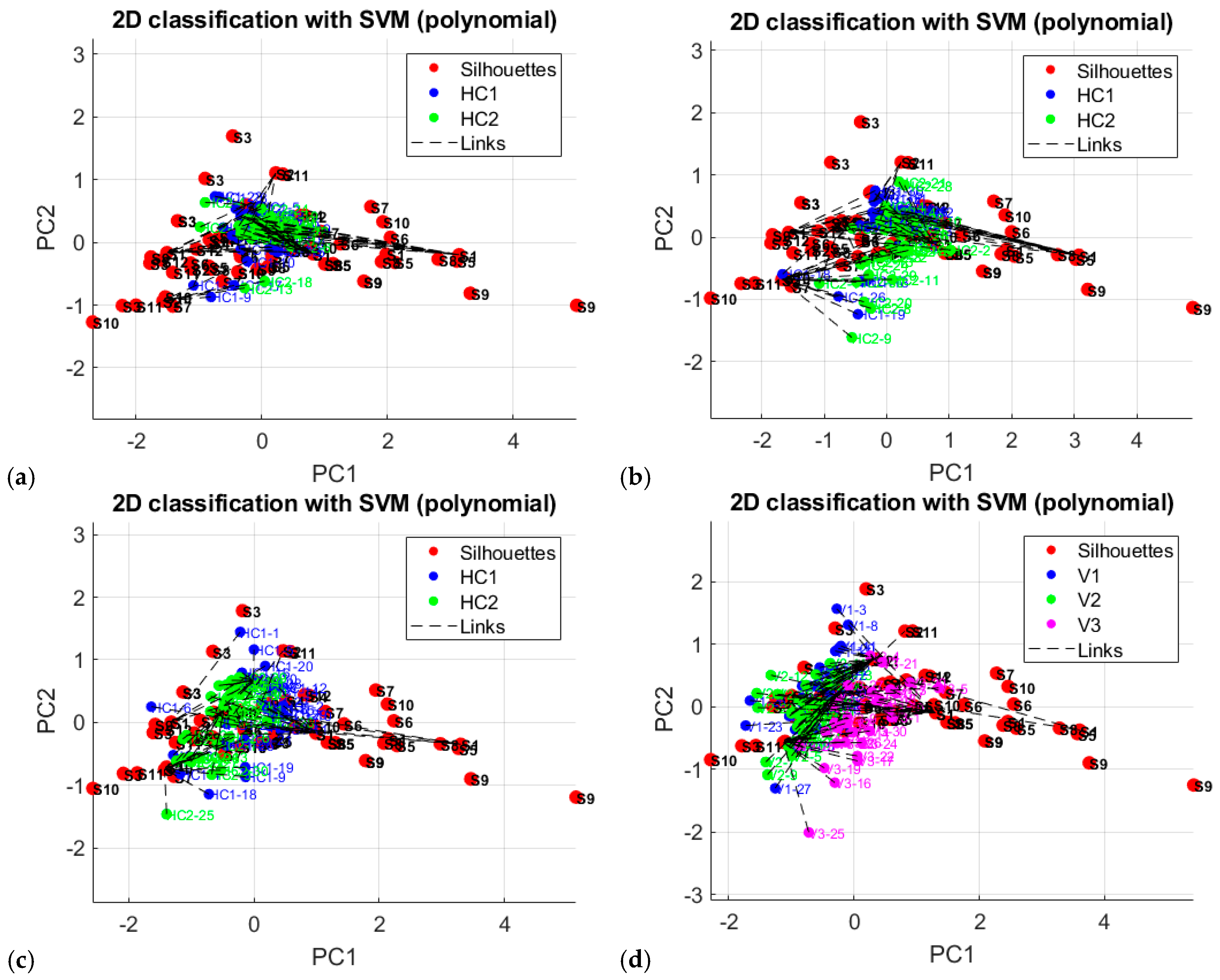

Figure 6 visualizes the clustering of silhouettes from the four historical periods using an SVM classifier with a polynomial kernel function. The figure serves as an illustration of the methodological approach, not as a final classification result. Its main purpose is to visualize how the SVM algorithm with a kernel function works in a two-dimensional space reduced by principal components (PC1 and PC2). Each of the four graphs visualizes the distribution of the data by principal components (PC1 and PC2), with different colors and labels indicating the classified categories—for example, silhouettes, classes (HC1, HC2), links (Links), and variants (V1, V2, V3). The visualization illustrates how the model divides the data in two-dimensional space, with some periods showing a clearer distinction between the classes, for example, the third sub-period for the Victorian style.

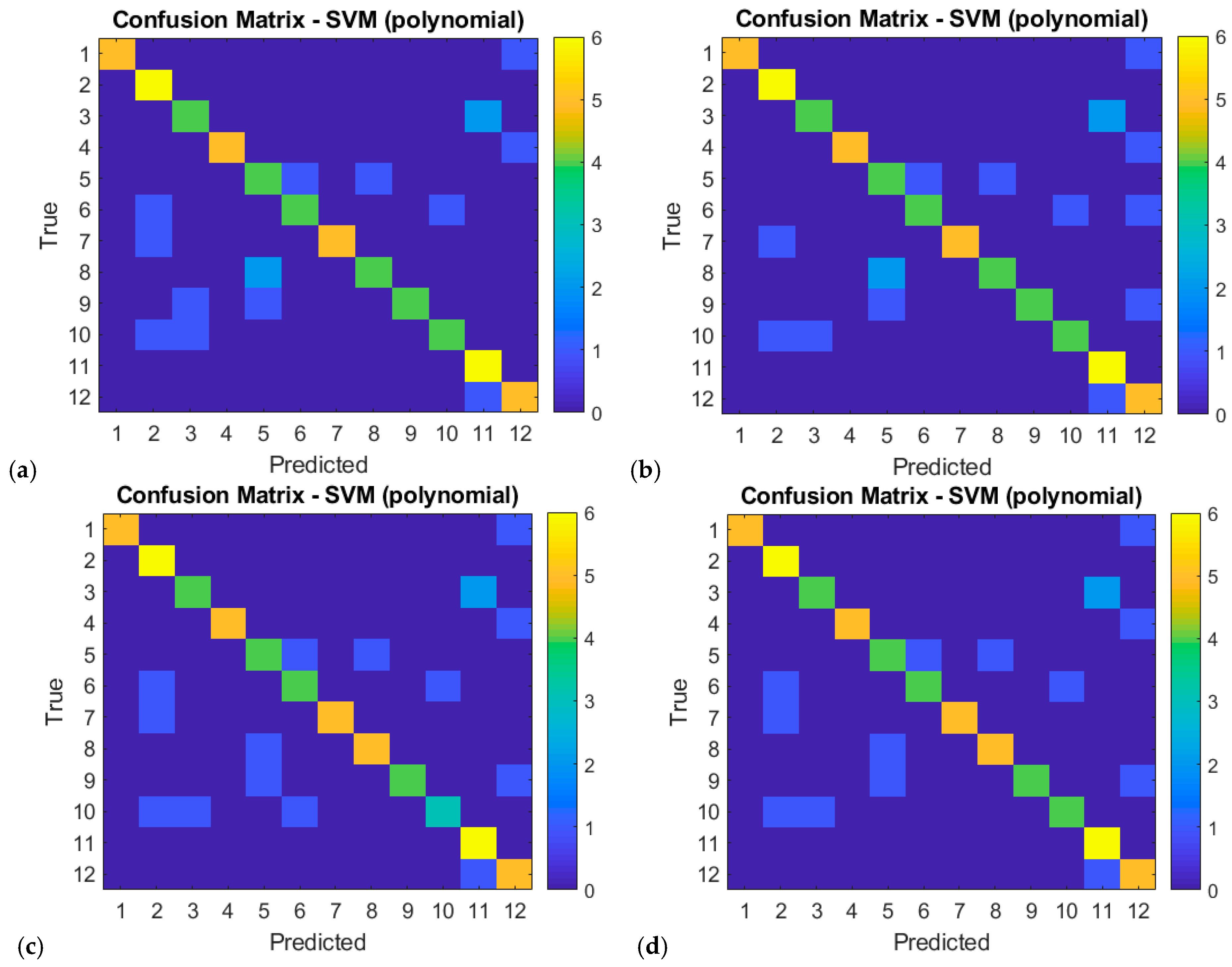

Figure 7 shows the confusion matrix using the SVM classifier with a polynomial kernel function. The most pronounced diagonal structure is observed for the Victorian period, which indicates higher accuracy and fewer classification errors. For Art Nouveau and Romanticism, there is partial agreement along the diagonal, but also significant scatter off it, which indicates difficulties for the model in distinguishing classes. Empire shows the weakest diagonal line, which means that the classifier often does not find matches with standard silhouettes. The color scale further emphasizes the intensity of the classification results—lighter cells on the diagonal mean more correct classifications, while darker ones off the diagonal indicate more frequent errors. The results confirm that the classification is most successful for the Victorian style, while Empire remains the most difficult for the classification algorithm to recognize.

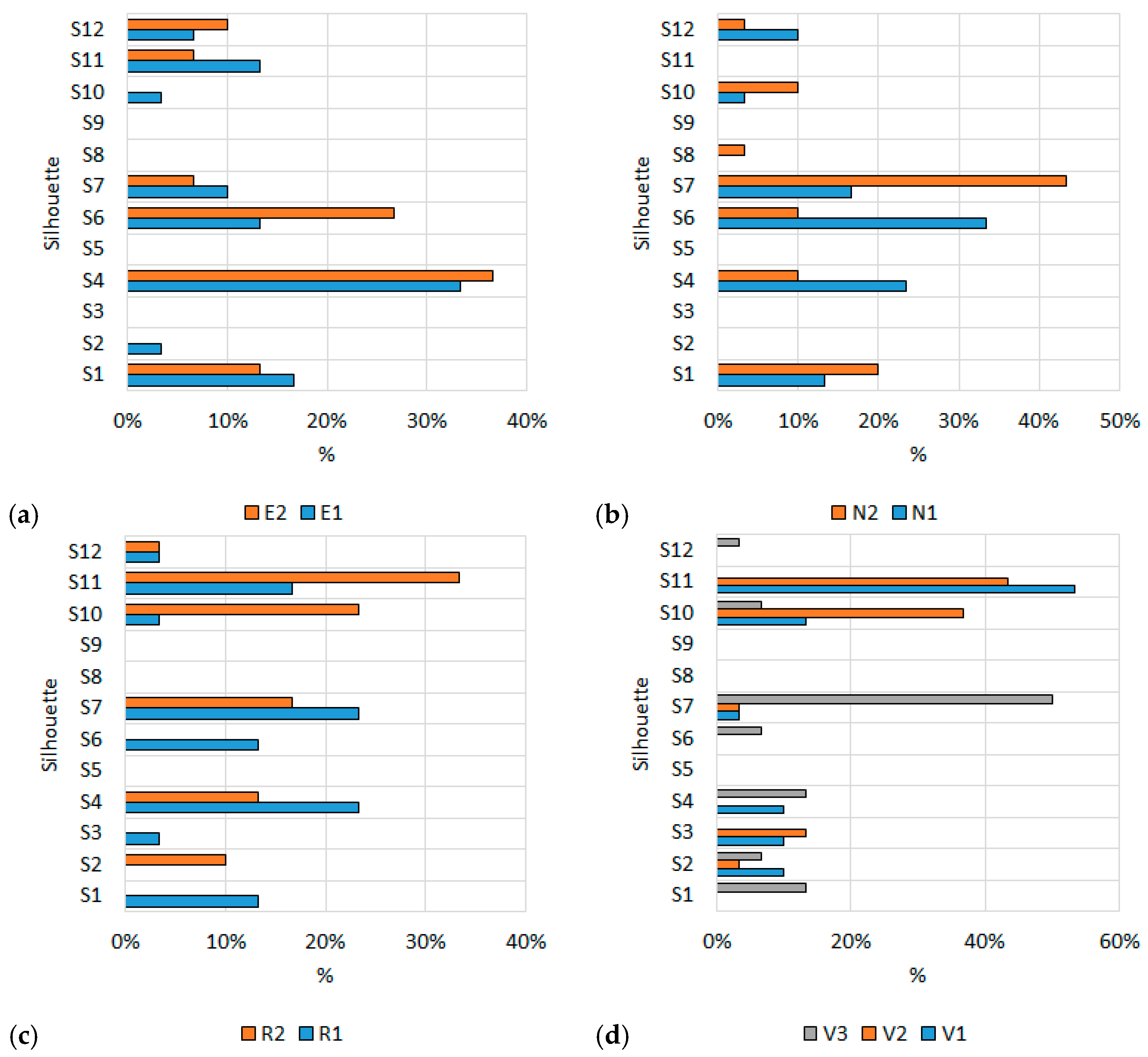

Figure 8 shows the percentage of silhouettes for each sub-period of the historical periods. The percentage distribution of 12 standard silhouettes (S1–S12) is presented within 9 sub-periods, covering 4 main historical dress styles: Empire (E1, E2), Art Nouveau (N1, N2), Romanticism (R1, R2), and Victorian (V1, V2, V3). Each sub-period is represented by 30 images, with the percentages reflecting the frequency of occurrence of a given silhouette in the respective group. The most distinct trends are observed in the Victorian style, where the silhouette S11 dominates with extremely high values—53% in V1 and 43% in V2. The silhouette S7 is also strongly represented in V3 (50%) and N2 (43%), which indicates a visual continuity between Art Nouveau and Victorian style. In Empire and Art Nouveau, there is a concentration around the silhouettes S4, S6, and S7; for example, S4 reaches 37% in E2 and 33% in E1, and S6 reaches 33% in N1. This shows that these silhouettes are characteristic of the early styles and have a role in their visual structure. Romanticism demonstrates a more even distribution, but with a distinct presence of S11 (33% in R2) and S7 (23% in R1), which suggests a transitional nature of the period between the earlier and later styles.

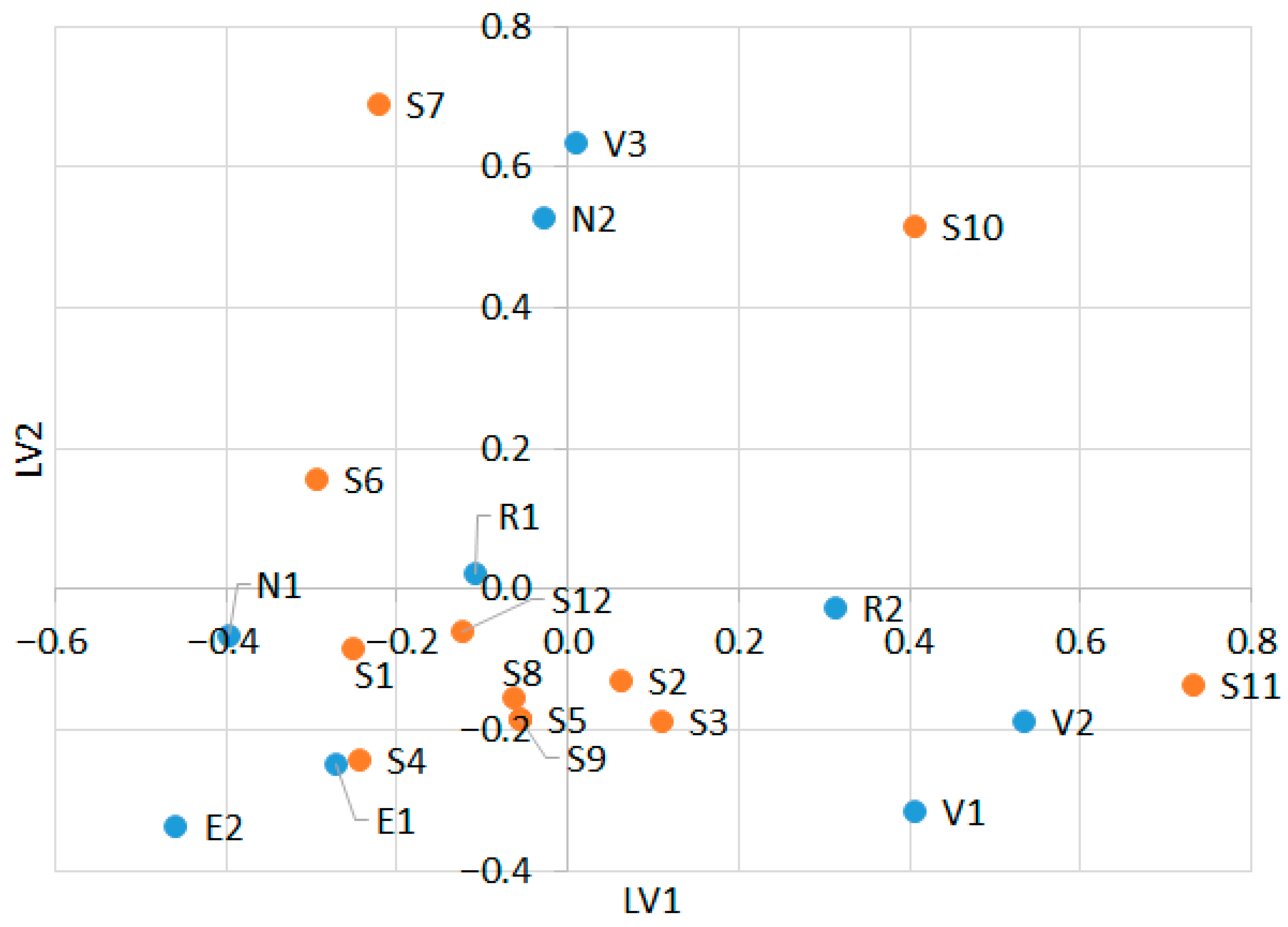

Figure 9 shows the distribution of silhouettes according to historical periods. The distribution of silhouettes in the latent variable space (LV1 and LV2) shows distinct groupings that correspond to different historical periods. Periods E1 and E2 (Empire) are located in the lower left quadrant (LV1 < 0, LV2 < 0), close to silhouettes S1, S4, and S6, which indicates a visual proximity between these silhouettes and the Empire style. N1 and N2 (Art Nouveau) are located in the upper left and central area, with N2 clearly expressed in the upper right quadrant (LV2 > 0), close to S7, which indicates that this silhouette is characteristic of Art Nouveau. Silhouette S6 is also close to N2, which suggests a possible stylistic connection. R1 and R2 (Romanticism) are located around the center of the graph, with R2 shifted to the right (PC1 > 0), close to S2, S3, and S5, which indicates that these silhouettes are less tied to visually dominant elements and can be considered transitional. V1, V2, and V3 (Victorian style) are located in the lower and upper right quadrants, with V2 and V3 being the furthest to the right and up. They are in close proximity to silhouettes S10 and S11, which have the highest values in LV1 and LV2. This indicates that these silhouettes are characteristic of the Victorian style and represent its visual identity. Silhouettes S2, S3, S5, S8, and S9 are located close to the center, which indicates that they do not have a clear affiliation with a particular historical period. The visual distribution shows that silhouettes such as S4, S6, S7, S10, and S11 have a stylistic connection to specific historical periods, while others (S2, S3, S5, S8, and S9) remain more unapplied to these eras.

The results of this study show that the shape indices FI14 (overall shape complexity) and FI3 (vertical asymmetry) are consistently identified as the most significant features across all selection methods. This finding aligns with that of Zou et al. [

24], who demonstrated that global shape variation and vertical asymmetry are effective for distinguishing historical dress styles in architectural analysis. These indices therefore capture fundamental differences that are crucial for the classification of historical dress silhouettes.

Initial accuracy values for k-NN, SVM, and DT classifiers were relatively low (up to 40.2%), reflecting the complexity of historical dress silhouettes and the internal scatter of the data. Similar challenges were reported by Hu et al. [

25] in the classification of ceramic artifacts, where simple models struggled with heterogeneous shapes. Optimization through kernel selection proved essential; the polynomial kernel in SVM significantly outperformed linear and RBF kernels. This result complements those of Umasankari et al. [

26], who found polynomial and Gaussian kernels to be more effective in modeling nonlinear dependencies, though our unusually poor RBF performance contrasts with the findings of Kim et al. [

27], who reported strong results for face recognition. The relatively high accuracy achieved for Victorian silhouettes (up to 81%) can be explained by their distinct visual markers, consistent with the conclusions of Wu et al. [

28], who noted that recognition algorithms perform better with categories that have stable visual features. Conversely, the low accuracy for Empire silhouettes reflects their minimal contours, echoing the findings of Magdalena-Benedicto et al. [

29], who observed difficulties in classifying objects with flowing or less defined shapes. Confusion matrices confirm that Victorian styles are most reliably recognized, while Empire styles are most frequently misclassified, similar to the pattern found by Mata-Montero et al. [

30] in botanical species classification, where visually similar categories caused errors.

Beyond numerical accuracy, the interpretive value of the method lies in its ability to formalize visual literacy practices. Indices such as FI3 and FI14 correspond to the historian’s eye for balance, proportion, and silhouette variation, thereby bridging technical modeling with established traditions of dress history. The visualization of silhouettes in latent variable space further illustrates stylistic continuity, particularly between Victorian and Art Nouveau, consistent with the findings of Rostamzadeh et al. [

31], who emphasized that fashion styles evolve gradually rather than abruptly. These findings are consistent with previous work on contextual communication structures in human–machine interaction [

32].

The automated approach adds value by providing reproducible baselines, reducing subjectivity, and enabling large-scale comparative analysis. Its practical applications span multiple domains: in education, automated grouping can help students trace the evolution of silhouettes; in museums, it can assist curators with cataloging and digital archiving; in design curricula, it offers iterative tools for training; and in film and theater costume departments, it can pre-sort archives to accelerate production workflows. Automated classification could also enrich visual libraries by enabling interactive search functions based on shape indices or historical period. In digital heritage projects, preliminary automated reconstruction can support large dataset processing before expert validation, while designers may use such reconstructions as heuristic inspiration.

4. Conclusions

This study indicates that efficient machine learning can raise historical dress silhouette profiling to a new level of accuracy and reliability through calculating centroid indices. The scalable nature of computational methods cannot replace the interpretive skills of historians. Rather, they are reproducible tools that can be used in combination with traditional means of understanding the landscape to provide beneficial support for museum catalogs, digital heritage projects, and educational applications. It combines visual literacy and quantifiable indices to extend the methodological foundation of dress history, opening up new possibilities for comparison. Among the models tested, the polynomial kernel of SVM proved most effective—its accuracy could be as high as 81%, with the highest success in classification being achieved for Victorian period dresses as distinctly recognizable silhouettes. The Empire, Romanticism Movement, and Art Nouveau periods had their own specific features, with these reflected as dominant shapes. Though the degree of accuracy is still lower than that wielded by expert historians, the sturdiness of this method lies in its capacity to carry out big datasets, reduce repetitive labor that comes from manual intervention, and establish reproducible guidelines going forth. However, further research should enlarge these databases in addition to incorporating algorithms that adapt themselves to real-time use. The application of this work could be beneficial in systems for intelligent decision-making and education platforms, whilst it will also need fashion design and exposure libraries throughout the visual arts as well as historically recreated silhouettes to serve contemporary creative practices.

Extending beyond fashion history itself, this methodological innovation is a baseline for future picture deconstruction in the broader context of digital humanities, although such tools designed from computation are becoming stronger pints of division between those who praise the quantitative rigor it enables, on the one hand, and those who display an aversion to modern machine technology and therefore place lesser value on these tools, on the other hand. Cultural artifacts can be measured relatively easily with sufficient accuracy of a reproducible type. Thus, this method not only enriches heritage studies via translating visual traditions into measurable indices, etc., but also presents a case for the ability of interdisciplinary cooperation to form new epistemological frameworks that are just as deep as those reached by the humanities and which combine the scalability of technology. Such integration has implications for both the maintenance and spread of cultural knowledge, with institutions and libraries now able to create interactive platforms that, while pretending to develop the field, would like to see the end of academia on the artistic form and style. This continuation is nothing less than a renaissance. It is in this sense that the research illustrates how machine learning can act as a strikingly active and truly innovative partner in cultural heritage, reshaping the processes of work, opening up new frontiers in comparative vision, or indeed even finding its own inspiration, which brings past esthetics into modern practice and pedagogy.