Abstract

In 2011, a new approach was introduced into the management of heritage on Ilha de Moçambique by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Known as the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach, this seeks to expand current understanding of the island’s historic urban heritage, recognising that ‘heritage’ is not limited solely to monuments or the built environment. Importantly, HUL incorporates urban sustainable development within the scope of heritage preservation. Given this, the adoption of the HUL approach has the potential to contribute to ensuring the authenticity and integrity of the built heritage, as prescribed by the 1972 UNESCO Convention, of Ilha de Moçambique, and effectively maintaining the Outstanding Universal Values that resulted in the declaration of the island as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991. This paper discusses how local communities use the resources and heritage available to them and the central role of commerce, and the marketplace, in the heritage landscape of the island. A critical aspect of this is the sale of antiquities, including archaeological items, to tourists. Perspectives developed within the Rising from the Depths (RftD) network recently supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) UK, with funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), offer positive alternative solutions to overcome this challenging situation. In particular, the network sought to identify how the tangible submerged and coastal Marine Cultural Heritage (MCH) of Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Madagascar, and its associated intangible aspects, can be utilised to stimulate ethical, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth in the region. Our paper demonstrates how the implementation of the RftD initiative when combined with the HUL approach can help to increase awareness among communities on Ilha de Moçambique about the relevance of their heritage and the need for preserving it while meeting everyday needs.

1. Introduction

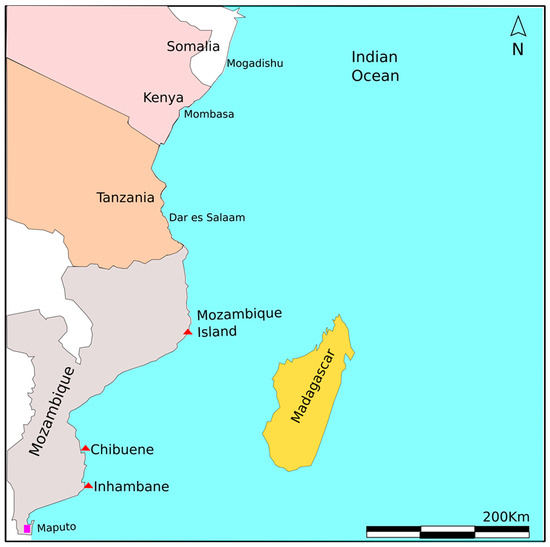

Ilha de Moçambique was the first World Heritage Site (WHS) designated in Mozambique, inscribed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) list in 1991. The island is located in the northern province of Nampula, and forms part of a coral reef archipelago in the Indian Ocean, of which two other islands, Goa and Sena, are also a part (Figure 1). Ilha de Moçambique is only 3 km in length and 200–500 m wide. It lies within a largely rural coastal landscape setting that attracts many tourists. A bridge built in the 1960s connects the island to the mainland [1]. The island is divided into two urban settlements: the macuti town, where the majority of the local community lives (Figure 2 and Figure 3), and the stone town with the major concentration of monuments. This latter area is also referred to as the museum quarter.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of Ilha de Moçambique (Mozambique Island), prepared by Varsil Marcos Cossa.

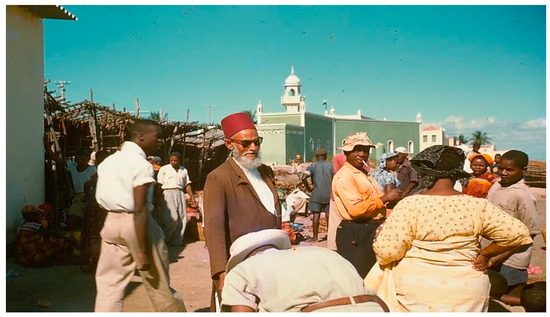

Figure 2.

Marketing is at the centre of the life of the inhabitants of Ilha de Moçambique. This image captures the social character of the marketplace. Old image, courtesy of Leonardo Adamowicz (After [2]).

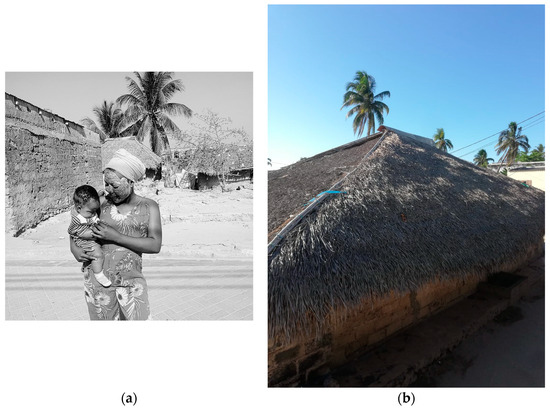

Figure 3.

(a) Macuti town and daily life (Photo: S. Selemane). (b) Details of a macuti house (Photo: S. Selemane).

Ilha de Moçambique is also referred to as Mozambique Island in English-speaking conventions, and the island is known as Muhipiti (or Omuhipiti) in the local Macua language. The origin of the name Muhipiti is linked to the island’s historical role as a site for the export of large numbers of enslaved persons, particularly during the 18th century, and persons coerced through forced labour in the 19th century [3,4]. Muhipiti may originate from the verb wiphita, which refers to the act of hiding so as to avoid being captured and shipped overseas as a slave. The retention and use of the name Muhipiti is important for the preservation of local community memories, the history of slavery, and recognition of the complex heritage of the island.

2. Historical Background

During the late first and early second millennium, CE littoral communities oriented towards maritime trade emerged along the East African coastline [5] (p. 101). These communities were differentiated from those of the hinterland. Felix Chami and others have associated these communities with early proto-Swahili communities. Ricardo Duarte [6] noted that these “proto-Swahili” were a Bantu community. They were first established in the Tana River region, in present-day northern Kenya, and spread throughout the coastal regions of eastern Africa, including Ilha de Moçambique. Their characteristic pottery was initially named Tana Tradition [6] (p. 38), and later renamed Triangular Incised Ware (TIW) by Chami [5]. Ilha de Moçambique was established as a Swahili town during the 10th century CE and developed into an important trading post.

International trade in East Africa was facilitated by seasonal monsoon winds, which enabled maritime connections between Southeast Asia and the East African coast from the mid-first millennium CE [6,7,8]. Trade remained an important factor in subsequent eras. As Duarte [6] (p. 41) notes, “when the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century their objective was to control the trade in spices from India to Europe, and their efforts to obtain gold and ivory on the east coast of Africa were intended to finance the spice trade with India”. An increase in the global world of trade and cultural interactions, connecting Asia to Europe through the island, developed with the Portuguese, who discovered a sea route via the Cape and established a fort on Ilha de Moçambique. Given its unique position, Ilha de Moçambique quickly became an important way-station for ships travelling to the Indies and as an access point to the interior of southern Africa. As noted by Mahumane and Simbine [9] (p. 17): “local trade routes supplied raw materials or finished fine goods that fed a growing maritime global trade in the 17th century. These routes were mostly dominated by the Portuguese who established the Carreira das Indias and invested in shipbuilding to sail to the Indies to buy spices and other exotic goods appreciated in Europe”.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Portuguese crown, on an annual voyage, used to bring cloth and beads from India to Mozambique to exchange for gold and ivory from the southern African interior [7] (p. 29). The majority of these goods, after passing Ilha de Moçambique, where the Portuguese trade was controlled in Mozambique, were transported to Quelimane and from there to Sena and Tete along the Zambezi River. In Sena, for example, local communities transformed familiar subsistence economies into trade through marketable goods, mainly ivory, iron, gold, and animal skins [10]. Little is known about Sena before the 16th century, although, similarly to Ilha de Moçambique, it was an Islamic settlement before being conquered by the Portuguese in the 16th century. According to Madiquida [10] (p. 79), Sena was the main entrance of the Portuguese expansion to the interior of Mozambique, as “indicated by evidence of long-distance trade which is found in abundance at the site, mainly glass beads and porcelain fragments, known from Mozambique Island”. Costa [7] (p. 29) notes that goods were sold first to merchants in different places called feiras (trading places) that were likely introduced by the Portuguese. The exchanges between Portuguese merchants and local communities at various feiras were often undertaken by itinerant traders, known as vashambadzi, but were subject to the payment of fees to local political authorities in the form of taxes or tribute [11]. Trade on Ilha de Moçambique was not limited to international goods. As noted by Radimilahy [8] (p. 32), “[e]xchanges of many kinds of products from one region to another have always existed between agriculturalists, forest dwellers and herders”, and regional exchange networks linked coastal and inland communities in various ways. As Portugal extended its colonial authority across Mozambique, Ilha de Moçambique became Mozambique’s first capital (1818–1898), before being replaced by Lourenço Marques (now Maputo), at the end of the 19th century. The circulation of both local and international goods remained a characteristic of trade on Ilha de Moçambique in the 19th and 20th centuries. Indeed, the contemporary marketplaces on Ilha de Moçambique are, in many respects, a legacy of the 16th century feiras.

3. World Heritage Designation and Existing Legislative Frameworks

After it had lost its economic, political, and administrative position, the island experienced economic decline [12], which also affected its tangible heritage, especially the Portuguese architectural elements and the town’s overall urban fabric [13] (p. 3), with limited efforts being aimed at their conservation until the 1980s. As part of the steady decline in the island’s prosperity, many historical buildings were abandoned by their Portuguese owners and local communities were not prepared to occupy them either because they were (and still are) expensive to maintain or because of their connotations as houses of the coloniser [14] (p. 14). With growing national and international recognition of the endangered nature of much of the historical, stone-built architecture, it was felt by many that if no measures were taken, nothing would remain of Ilha de Moçambique’s rich tangible heritage [13] (p. 3). As noted, for example, by Luís Filipe Pereira [15] (p. 5), one of the members of the Association of the Friends of Ilha de Moçambique, only the memories of local inhabitants of the functions of the different buildings would survive eventually since many buildings were physically decaying.

In the early 1980s, however, local initiatives aimed at preserving this rich architectural heritage began to emerge, and funding was sought through collaboration agreements with various international partners, including UNESCO, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the international development agencies of several Scandinavian countries. In particular, a team led by Jens Hougaard, an architect from the Aarhus School of Architecture in Denmark, enabled the preparation of the necessary documentation for the successful nomination of Ilha de Moçambique as a World Heritage Site.

In 1982, following recommendations made by Hougaard and his team coordinated by the National Built Heritage Service of the former State Secretariat for Culture, the Government of Mozambique adopted the 1972 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage. This was followed by the adoption by parliament of the 1988 Heritage Law, Lei nr. 10/88, de 22 de Dezembro. This legal framework enabled the process through which the site was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, under criteria (iv) and (vi). Criterion (iv) recognizes the importance of Ilha de Moçambique for its varied architecture, mainly historical buildings, which are considered an outstanding testimony of ‘local traditions, Portuguese influences and to a somewhat lesser extent, Indian and Arab influences … all interwoven’ [2,16]. Use of criteria (vi) refers to the historical contribution of the island ‘to the establishment and development of the Portuguese maritime routes between Western Europe and the Indian sub-continent and thence to Asia’ [16]. A detailed study, popularly known as the “Blue Book” [1], prepared by the Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark, and published jointly with the Mozambique State Secretary for Culture was a key component of the nomination dossier.

Monitoring actions by ICOMOS followed, guided by the Ministerial Department of Monuments. This activity was challenging, as most of the monuments remained poorly conserved, with some eventually collapsing. Given the focus on the stone-built architecture largely associated with the Portuguese occupation of the island, communities living in macuti town inevitably feared their concerns would be left out of future management plans for the island’s heritage. There was no incentive for them to maintain the original macuti structures, especially as they considered people in a brick house with a zinc roof as having better living conditions than those in traditional, wattle-and-daub macuti houses (see [17] for a detailed description of these).

During the 1980s, conservation efforts were also combined with development [14,15], starting with attributing functions to the abandoned buildings of historical and architectural significance. Additionally, parallel efforts were made toward reviving the economic basis of the island, based on fishing, salt production, and agriculture. Actions were combined at the level of public services (water, public works, and education); economic initiatives (fishery, agriculture, salt production, and tourism); and at the cultural level (conservation, restoration, and crafts) [14] (p. 15). These activities included (i) the creation of a Conservation and Restoration office; (ii) the establishment of the Friends of Ilha de Moçambique Association; (iii) various exhibitions and study plans on Ilha de Moçambique’s tangible heritage; and (iv) some interventions that allowed the restoration of a few buildings, as well as the inclusion of Ilha de Moçambique into UNESCO’s various cooperation programmes. These steps were not enough, however, to halt the steady degradation of the town’s urban fabric [14] (p. 14).

In the 2000s, a new threat to Ilha de Moçambique’s archaeological heritage also emerged, related to commercial treasure-hunting activities. In this context, between 2000 and 2014, underwater interventions were exclusively carried out by the Portuguese commercial company Arqueonautas, S.A, in consortium with the Mozambican company Património Internacional (AWW/PI) [18]. This company was created for commercial purposes with a licence provided by the Ministry of Culture in Ilha de Moçambique, despite strong opposition from the archaeological community. Unfortunately, in this process of commercial oriented activity, numerous objects of underwater archaeological heritage were decontextualised and poorly referenced. Fortunately, in 2014, the Ministry of Culture, on the recommendation of the National Council for Cultural Heritage, cancelled the licence, and these activities ceased. A decision was then taken to survey and assess the situation related to the underwater archaeological heritage of Ilha de Moçambique. This was led by the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Eduardo Mondlane University.

Through the Ilha de Moçambique Archaeology, Research and Resource Center (CAIRIM), in coordination with UNESCO, monitoring and protection of 25 shipwrecks already inventoried around the Island of Mozambique is now being carried out, following a mandate from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. This work is guided by the 2001 UNESCO Convention in collaboration with UNESCO-Maputo and the U.S. Slave Wreck project [19] (p. 74). Research is also continuing on Ilha de Moçambique within a training program financed by the Swedish International Development Coordination Agency (SIDA).

These conservation efforts have not always been recognised by members of the local community since other aspects related to daily community needs have been left out, giving rise to frustration among both heritage managers and the community. This is partly a result of the narrow focus of heritage management on the island. The criteria for the initial inscription of the island were entirely based on its tangible values with respect to the authenticity and integrity requirements for a property to be recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Yet, other aspects of heritage, particularly the varied intangible heritage of Ilha de Moçambique, were not given due consideration in the nomination process. This narrow focus on monumental architecture, and the lack of conservation efforts to address the needs of local communities, has led to several management challenges. These are outlined in the following sections.

4. Moves toward Integrating Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development

An emphasis on linking heritage with development issues began to emerge in the years following the inscription of Ilha de Moçambique on the World Heritage List, as heritage practitioners began to realise that this was fundamental for heritage conservation on the island. To address this, following a request from the Government of Mozambique to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), funding was made available to UNESCO to prepare a detailed report on the state of conservation and opportunities for the rehabilitation of various monuments. Prepared jointly by a national and international mission, led by Sylvio Mutal, a UNDP expert, this ran to seven volumes. The main objectives of this mission were both the rehabilitation of the human settlement and the physical rehabilitation of the island’s cultural urban heritage. In all, 50 project files were generated. These projects were peculiar in that they combined ‘development’ and ‘preservation of cultural and natural heritage’ [20,21] so as to create an integrated process of rehabilitation, in which heritage conservation was just one of several facets. Following Mutal [12] (xi), it becomes “evident that an action based solely on the preservation of the historic built heritage/landmarks would be useless. It would not be sustainable”.

However, this initiative was ultimately stopped by UNESCO, on the grounds that it was not adequate, and that priority should be given to the development of a Special Status Management Plan for the island. Nevertheless, one important lesson that did emerge was recognition of the need for adaptive re-use of monuments and the integration of actions aimed at human development in any future heritage protection and conservation efforts.

The legal requirement established by the 1972 UNESCO Convention falls under the umbrella of its World Heritage Centre (WHC), which stipulates the need for regular monitoring of the state of conservation of the site, periodic reporting, and reactive monitoring by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). In this process, recommendations are provided by ICOMOS to ensure that stronger conservation strategies are implemented to safeguard a site’s immovable heritage. Nomination for World Heritage status, when properly approached, contributes to the improvement of urban environments and the preservation of immovable heritage since such heritage assets often attract investment from both the public and private sectors [22,23]. Several monitoring missions to the island by experts from ICOMOS have looked at this aspect over many years, and the mandatory requirements of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre are to routinely report on the condition of these monuments and the maintenance of overall site integrity and authenticity necessary for the site to be retained on the World Heritage List. The creation of the Cabinet for the Conservation of the Island of Mozambique (GACIM) by the Ministry of Culture in 2006 [24] was partly intended to give further support to these conservation measures. Its overall role was to implement the heritage legislation enacted by the Government of Mozambique and UNESCO for Ilha de Moçambique’s preservation and valorisation, thereby helping to maintain the island on the World Heritage List through continuous monitoring of its state of conservation. GACIM’s monitoring activity focused mainly on the built heritage; however, adherence to this protocol has narrowed how the island’s heritage value has been conceptualised and overlooks the local community’s perspective, which is that of a place and not any single building.

In recent decades, the Government of Mozambique attempted to correct this over-emphasis on tangible heritage by adopting the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Intangible Heritage and the 2005 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. To this end, the Ministry of Culture through its Institute for Socio Cultural Investigation, took the initiative to compile procedures for an inventory of the island’s intangible heritage [25]. This created opportunities for improving the visibility of such expressions of intangible heritage, including typical culinary practices, cosmetics made using natural resources, and a set of religious beliefs and manifestations on the island. As observed by Sylvio Mutal, “Muslim, Christian, [and] Hindu faiths are practised [on the island] in peace and harmony” [12], although the first is more dominant with roots in Swahili culture, mainly in the macuti town.

With the support of the African World Heritage Fund (AWHF) and associated institutions (World Heritage Centre [WHC], CRAterre-ENSAG [the International Centre for Earthen Architecture], and the UNESCO Africa 2009 programme), the first Management Plan for 2010–2014 was prepared for the island, in collaboration with the former Ministry of Culture and Eduardo Mondlane University. The idea of this plan was to place local stakeholders’ interests at the centre of conservation efforts, through constant consultation and consensus building. The plan also established guidelines for daily monitoring of conservation needs and issues, and how they should be addressed on a regular basis. The specific objective was “to preserve and value everything good that Ilha de Moçambique possesses, in terms of historic, cultural, ethnoarchaeological, artistic and museological heritage, with its heritage importance and exceptional world value, dating back centuries” [16] (p. 21).

This objective emanated from the existing protective legislation in the country and the 1972 UNESCO Convention. This reflected the prevailing vision in the Ministry at the time regarding heritage management which focused on preservation without clearly defined heritage management mechanisms. Although this management plan was important in considering both tangible and intangible heritage and expanding the existing conceptualisation of the heritage landscape, it did not satisfactorily address ways of directly involving local communities in heritage protection and management, resulting in the continued lack of clarity about the importance of heritage protection to people’s everyday lives [14]. No attention has been paid to how local people engage with the wider heritage landscape of the island, not only in terms of buildings but also in relation to the way they use different spaces on the island and draw material benefits and heritage values from these. A good example of this is provided by the way the island’s residents establish active relations with their heritage through their routine participation in trade and exchange in outdoor marketplaces.

With these points in mind, there is clearly a need to find a strategy for how to integrate “Indigenous” conceptualisation of the island as a ‘marketplace’ into heritage management processes in a manner that references and engages with the island’s Swahili cultural history, while also supporting local livelihoods and sustainable development. This is where the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach is of benefit. Specifically, the HUL approach draws attention to the significance of living, historic cities by giving due recognition to the use of tangible and intangible heritage resources and their management as part of the daily life of their citizens [26]. This is largely true for the inhabitants of the macuti town. These island communities have long integrated their heritage in a broad sense that defines the historic urban landscape approach. These comprise various aspects of the island’s maritime landscapes, such as urban and public spaces, intertidal zones, beachfronts, coastal protected areas, and fishing grounds. These have recently been listed in the Regulation for the classification and management of the built and landscape heritage of the Island of Mozambique [27]. The Rising from the Depths Network (RftD) initiative [28] provides an additional template for increasing the benefits for local communities arising from Ilha de Moçambique’s inscription onto the World Heritage List in a manner that complements the HUL approach.

5. Implementing the Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Heritage Conservation on Ilha de Moçambique

Historic urban landscapes can be defined as those parts of urban areas derived from ‘historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes’ and are part and parcel of the everyday, lived experiences of their inhabitants. Conceptually, these spaces extend beyond more localised ‘historic centres’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting and the traditions and perceptions of local communities [26] (p. 198). As articulated by Rossa et al. [29], the HUL approach is aimed at preserving the quality of the human environment, enhancing the productive and sustainable use of urban spaces, while recognising their dynamic character, and promoting social and functional diversity. It integrates the goals of urban heritage conservation and those of social and economic development. It is rooted in a balanced and sustainable relationship between the urban and natural environment, between the needs of present and future generations, and legacies from the past.

As identified by Oers [26] (p. 9), “living historic cities display characteristics that basically revolve around three competing and at times interlocking issues, which need recognition and attention if this valuable resource is to be managed and preserved for the benefit of present and future local communities”. Oers identified these issues to be the following:

“(1) A constant need for adaptation and modernization in recognition of the cycle of cities that grow, mature, stagnate and then regenerate (or else decline);

(2) An expansion of interrelations with a widening of stakeholder groups and interests, which requires negotiation and conflict resolution;

(3) Changing notions of what is to be considered heritage, which needs a broadening of approaches for recognition and inclusion”.[26] (p. 10)

Ilha de Moçambique can be defined as a Swahili urban landscape because it shares a mixture of cultural architectural influences, “the main elements [of which] were for very long periods derived from similarities in conduct (trade and commerce), assembly (urban communities) and belief system (Islam) [also found elsewhere] around the central stretch of the Indian Ocean rim” [26] (p. 8). The legacy of this Swahili history is visible on the island and within its community in different ways. As Duarte noted, Swahili architectural influences are visible on the landscape, for example, with the presence of mosques [6]. However, they are also visible in practices and habits, one of them being trade. It is in these practices that Swahili cultural influences are better perceived.

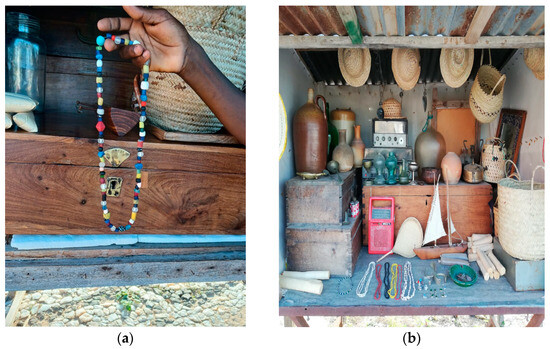

On Ilha de Moçambique, the market is a dominant feature in the daily life of the island’s inhabitants. The markets do not merely uphold a subsistence economy, but are part of cultural practices, and are also found in different strategic places. Patrons are determined by the type of products sold and potential customers: crafts, including antiquities, are primarily sold to tourists, while food and a variety of utilitarian products are principally sold to members of the general public and local residents (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Craft Market and antiquities on sale, such as glass beads mixed with modern types (Photo: S. Selemane). (b) Utilitarian Market offering local handicraft products and food (Photo: S. Selemane).

As previously noted, Ilha de Moçambique was established as a marketplace in a larger Swahili cultural landscape, on trade routes that spanned East Africa and the Indian Ocean. Swahili communities, who share many common cultural similarities, are now spread across the East African coast from Somalia to northern Mozambique [30]. However, while “trade and commerce have lain at the heart of Swahili culture” for over a millennium, “the modes of commerce and the spaces of exchange have changed and multiplied over time. Rather than stable, authentic Swahili cultural artefacts, commercial spaces in the cities and towns reflect the multiplicity of origins and the cosmopolitan character of coastal life” [31] (p. 24). This is certainly true for Ilha de Moçambique. Local communities organise themselves and sell products in different places in an informal way, a practice that happens elsewhere in Mozambique. Currently, there are three official municipality markets operating on the Island, and a fourth located on the mainland. The principal, central market was established in 1887 as a permanent market building (Figure 5). It is a complex structure with a symmetrical quadratic plan. The corners of the building are marked by small towers which are connected by tall iron railings. This complex with its outdoor facilities is still in use but in need of regular maintenance (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 5.

A panoramic view of the main Municipality market/Ilha de Moçambique in 2024 (Photo: Courtesy of Cláudio Zunguene).

Figure 6.

(a) The functioning of the Market. (b) The state of degradation of the building is evident (Photo: Courtesy of Cláudio Zunguene, 2024).

In common with most other towns and villages across mainland Mozambique, the dominant trade items circulating in the small markets on Ilha de Moçambique are agricultural products, such as vegetables and fruits from the Lumbo area on the mainland, and fresh and dried fish caught off the island (Figure 7a,b). Currently, considering that few local residents can afford a freezer, it is becoming common to conserve seafood in someone else’s freezer and pay a modest price of 10 Meticais (local currency; 1 Euro is roughly 67 Meticais) for the service [32].

Figure 7.

(a) Fresh seafood for sale on Ilha de Moçambique (Photo: S. Selemane). (b) Dried fish on sale in the local market (Photo: S. Selemane).

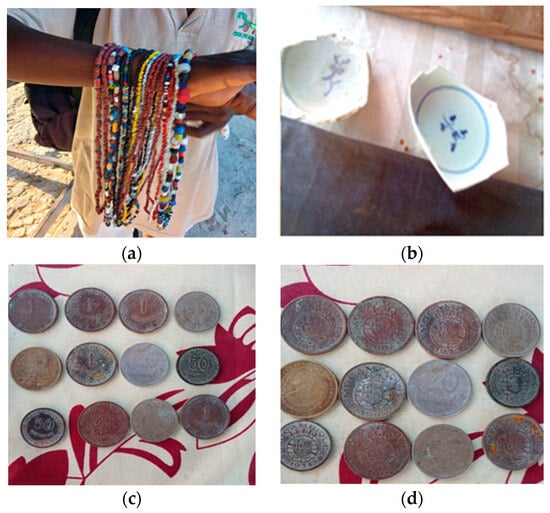

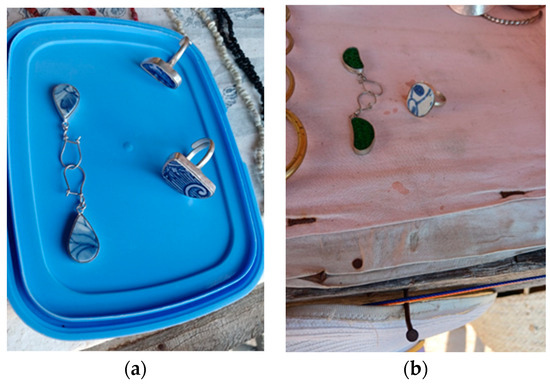

However, it is possible to identify some seemingly distinctive features about these markets on Ilha de Moçambique that differentiate them from those on the mainland. Specifically, young people on Mozambique Island are engaged in the trade of antiquities, with the preferable place to trade these being the stone town, where most tourists typically congregate, either near the Fortress or in front of the Museum. Items being sold include old glass beads, which are mainly found in intertidal zones, but also in houses, recovered during digging house foundations, refuse pits, latrines, or some other compound facility. Beads are converted into marketable necklaces (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Old coins that some families have in their homes are also sold, as well as fragments of porcelain that are converted into earrings (Figure 9 and Figure 10) [30,33].

Figure 8.

(a) Beads (including archaeological examples) on sale in the market (Photo: N. Baltazar). (b) Antiquities and crafts for sale in the market (Photo: S. Selemane).

Figure 9.

Antiquities for sale on Ilha de Moçambique. (Top left) (a) Beads (Photo: N. Baltazar); (Top right) (b) Porcelain (Photo: S. Selemane); (bottom) image (c,d) Old coins (Photo: N. Baltazar).

Figure 10.

Examples of archaeological materials being incorporated into jewellery for sale in the market (a,b) earrings and finger rings using Chinese porcelain (Photo: N. Baltazar).

This situation is concerning for various heritage authorities. Attempts to discourage the practice by the Museum and the central authority in the Ministry of Culture have not succeeded, despite the efforts and energy of various individuals and local authorities with strong support from Eduardo Mondlane University. According to the existing heritage legislation [34], the sale of archaeological objects is prohibited. The UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Heritage reinforces this position. Although it has not yet been adopted by Mozambique, the Convention has been used as an example and reference to address this problem.

Although the antiquities and archaeological material being sold are not usually recovered from in situ contexts, with many coming from the shoreline, they still possess archaeological value, and their conservation and care matter as part of wider strategies aimed at protecting the island’s tangible archaeological heritage. According to Simbine [33] (p. 92) “documenting the location [where] objects [were found] taken in conjunction with an analysis of environmental and human catalysts, may allow archaeologists to trace their origin to sites or places and perform more meaningful investigation”. The practice of selling antiquities, and the inability of the legislation to deter members of the community from selling antiquities, also calls attention to questions of what should and should not be sold within a context of desirable ethical and inclusive sustainable development. Developing ethically informed approaches to the use of marine cultural heritage was a core focus of the Rising from the Depths Network [28]. Members of the RftD initiative emphasised, for example, that the best strategy for protecting heritage is to first meet the needs of local communities. The use of heritage resources to benefit local communities on Ilha de Moçambique should also be guided by a code of ethics that is clearly defined to be understood for the benefit of all in the community. This point is developed in the following section.

6. The Market Place and Antiquities: Challenges and Proposed Solutions

The RftD and HUL approaches to heritage conservation are centred on finding uses for heritage that can benefit local communities. The HUL approach encourages an enlarged understanding of heritage, that is not solely about buildings, but also considers practices and spaces such as the market. This is an important observation to take on board when considering conservation issues and heritage management, especially as local communities on the island spend most of their time outside of buildings, in open spaces designated for trade and socialising. Given this, we argue that the HUL approach provides an important lens for addressing conservation issues and heritage management in Swahili towns like Ilha de Moçambique.

Marketplaces or commercial spaces on Ilha de Moçambique are part of the Swahili history of the East African coast to which the island belongs. However, as pointed out by Heathcott [31] (p. 24), the modes of trade and places of exchange have changed and multiplied over time: commercial places in the Swahili World reflect the multiplicity of origins and cosmopolitan character of coastal life. The same is true for contemporary Ilha de Moçambique as objects with different origins (Tanzania, India, China, and Japan) continue to circulate (Table 1). The markets are also places for socialising, and in the recent past the island’s main market was located near the main mosque (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Marketplace characteristics on Ilha de Moçambique (Data collection, courtesy of Saíde Selemane).

There is no doubt that the development of marketplaces on the Island is an activity that benefits locals, but they need to be regulated with respect to heritage protection and development. The existing legislation can be better implemented to help achieve this goal. Local communities need to be informed as to what can and cannot be sold. At the same time, this is a shared responsibility of the island’s inhabitants and of the tourists buying the products, and tourists should also be informed of the heritage legislation (see discussion in [35]).

Two pieces of recently introduced legislation are intended to support these goals. These are the ‘Regulation for the Classification and Management of the Island of Mozambique—Built and Landscape Heritage’ [27] and the ‘Regulation for the Management of Immovable Cultural Goods’ [36]. Both were developed as part of a collaborative effort involving the Faculty of Architecture and Physical Planning, Eduardo Mondlane University, and the Ministry of Culture through its National Directorate for Cultural Heritage, between 2010 and 2016.

Regarding the former, this regulation is innovative in that it encompasses both cultural and environmental legislation in a manner that integrates monuments, their landscape setting, and their associated history of African, Asian, and European contacts. Courtyards, open spaces, beaches, mangroves, other coastal protection zones, and urban landscapes together with the archaeological and built heritage are mentioned in this regulation with an aim to improve the overall management of the island’s heritage resources. It is worth mentioning that a key provision of this Regulation (in line with national legislation) is the prohibition of the commercialisation of archaeological finds of any kind and at any location, following applicable legislation. As discussed above, this helps to reinforce previous legislation and can be also used to discourage the sale of archaeological materials collected from the intertidal zones and other locations within the island, as well as antiquities from within and outside the island.

The primary focus of the Regulation for the Management of Immovable Cultural Goods is on using a grading system to determine appropriate kinds of interventions in the historic fabric, following guidelines set out in the national Monument Policy in 2010 [37]. The grading system involves the classification of buildings into four categories from A to D (Table 2) and is a flexible approach to historic building conservation that reduces the risk of monumentalism, as identified by the HUL approach. The approach is founded on the assumption that to reflect the dynamic, multifaceted, and cosmopolitan character of Swahili cities, heritage professionals must pay attention to the use of the urban landscape as a whole, and shift their overemphasis on monuments to a much broader conceptualisation of heritage based around identification of community needs within the urban space [31] (p. 21). For example, according to the Regulation interventions in the Grade C category of buildings will depend on their environmental location, where urban landscapes, comprising both the building and associated intangible values, are considered together [36]. Grade C is perhaps the only one that can be implemented for macuti houses.

Table 2.

Grading system for the built heritage (after [2]).

As observed by Heathcott with reference to Lamu town in Kenya “some of these macuti houses accumulated architectural modifications, context adaptations, expansions and fashion upgrades over time, according to the flow of wealth into the town” [31] (p. 27). In the Ilha de Moçambique case, the scarcity of palm trees and the lack of environmental rules to control the use of this resource provide additional motivations for the modernisation of macuti houses, using zinc roofing materials [38]. The Regulation also clearly defines the uses to be given to heritage in general, thereby helping ensure the sustainability of heritage preservation. The various uses considered under this Regulation are activities associated with education, scientific investigation, the hospitality industry, cultural tourism, and social activities, which should be attributed in accordance with the grading system. The Regulation also indicates that the functions assigned to heritage buildings should benefit local communities and support sustainable and appropriate use of the built heritage, which demands knowledge of their priority needs, through constant dialogue and sensitisation around the conditions and goals of the Regulation.

As seen in Table 2, the recommended functions for the Grades A+ and A, because of their high heritage value, are more clearly indicated compared to other grades with relatively limited heritage values. Hence, in essence, the grading system enables heritage management of monuments in a flexible way, but it also has limitations since it can not be fully applied in the macuti town and allows changes or modifications to structures classed as Grade B, C, or D without further scrutiny of how the proposed changes might alter the overall historical fabric of the building (such as the use of novel raw materials for repairs and extensions, e.g., replacing roofing tiles with zinc sheeting), or the overall appearance of a building’s facade which might significantly alter the wider streetscape.

7. Discussion

The inhabitants of Ilha de Moçambique, as with many other archeological wonder-worlds, often find themselves at the crossroads between preserving their cultural heritage and satisfying economic needs. This island is home to a wealth of historical artefacts, structures, and sites that hold invaluable insights into our collective past. Yet, the lure of the commercial market can pose a serious threat to the integrity of these archaeological remains. More feasible ways in which cultural markets on such islands can operate without the sale of artefacts, but while promoting sustainable heritage preservation, need to be identified.

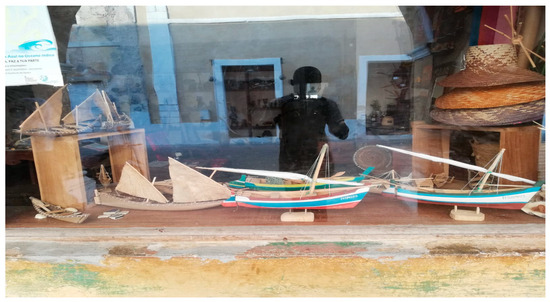

Legislation alone is not enough to prohibit the sale of archaeological objects and antiquities by local community members. One possible solution is to encourage creative heritage-related activities and to concentrate these in a Heritage Visitor Centre or in a cultural marketplace to benefit everyone. The creation of a Heritage Visitor Centre would appeal to tourists and provide employment opportunities for local guides and curators, thereby helping job creation and income generation (For examples, see Figure 11). This Centre could be established within the fortress and enlarge its functions and uses [39].

Figure 11.

Creative economy on Ilha de Moçambique—a good solution for heritage protection (Photo: S. Selemane).

As discussed above, approaching the heritage of Ilha de Moçambique from the Historic Urban Landscape perspective draws attention to an expanded understanding of the heritage landscape, that comprises the bay and the island, including the macuti city and the stone town. Even within the stone town, there are different areas of utilisation encompassing administrative, commercial, fishing, and religious activities [16]. The RftD approach complements the HUL approach by drawing attention not only to defining heritage but also to the role of heritage in sustainable development to benefit local coastal communities. By adopting a comprehensive approach that encompasses sustainable tourism, community involvement, regulation, and education, it may be possible to protect and celebrate the archaeological heritage of Ilha de Moçambique for generations to come. The following concepts and action points provide a foundation for achieving this, through the development of a model for cultural markets in Ilha de Moçambique.

7.1. Sustainable Tourism as a Cornerstone

Cultural markets on the Island should be redefined as hubs for sustainable tourism, focusing on the holistic experience of visitors rather than merely the sale of artefacts. Sustainable tourism emphasises the interconnectedness of culture, nature, and heritage, encouraging tourists to engage with local history and communities while respecting the environment. Immersive experiences, guided tours, and educational programs that provide insights into the island’s history and archaeology can replace the transactional nature of artefact sales [40,41].

7.2. Community Engagement and Ownership

The operation of cultural markets should involve empowering local communities to take an active role in heritage preservation. By involving local residents in the management and operation of these markets, a deeper sense of ownership and responsibility for the preservation of archaeological artefacts can be fostered. This approach would not only safeguard the artefacts but also ensure that economic benefits are more evenly distributed among the local population. Community-driven initiatives can create a strong sense of pride and a shared commitment to cultural heritage preservation [42].

7.3. Regulation and Licensing

Stringent regulation and licensing for the sale of antiques must be put in place to prevent the illegal trade in cultural items. With the collaboration of the government, establishing a legal framework that governs the sale and transfer of antiques but not archaeological artefacts is critical in achieving such a milestone. All sales should be subject to strict oversight, documentation, and ethical sourcing. This discourages the sale of illicitly acquired artefacts, supporting the authenticity and provenance of the items [43,44].

7.4. Educational Programs and Awareness

The Ilha de Moçambique Cultural Market should offer a range of educational programs and materials that raise awareness about the importance of preserving the island’s cultural heritage. These programs can target both residents and tourists, fostering a sense of responsibility for the protection of this heritage. By highlighting the cultural and historical significance of artefacts, buildings, and open spaces, it will become more likely that people will value them beyond their market value [45].

7.5. Strategic Oversight of Cultural Markets

A strategic management model is crucial for promoting sustainable development and the preservation of local culture. The strategic management of cultural markets in Ilha de Moçambique should focus on valuing local culture, economic sustainability, and community engagement. Such an approach would contribute to the strengthening of these markets and the promotion of Mozambique’s cultural identity. The key elements for effective management, in our view, are as follows:

- ○

- Cultural Environment Analysis:

- ○

- An in-depth study of culture, including traditions, craft techniques, and the role of local products.

- ○

- Assessment of market demands and preferences, identifying consumer segments and trends.

- ○

- Strategic Objectives:

- ○

- Definition of measurable goals, such as increasing artisans’ income, expanding sales, promoting cultural tourism, and conserving traditional culture [46].

- ○

- Partnerships and Stakeholders:

- ○

- Engagement with key partners, such as artisan associations, cultural institutions, government authorities, and the private tourism sector.

- ○

- Inclusion of local communities in the management process and decision-making [47].

- ○

- Cultural Product Development:

- ○

- Encouragement of innovation and the creation of craft products and seafood dishes, while maintaining cultural authenticity and meeting market preferences.

- ○

- Adaptation to contemporary standards without losing a product’s cultural essence [48].

- ○

- Marketing Strategies:

- ○

- Development of campaigns to highlight the cultural richness and uniqueness of the products.

- ○

- Utilisation of social media, digital marketing, and cultural events to reach broad audiences [49].

- ○

- Infrastructure and Logistics:

- ○

- Improvement of market infrastructure, including exhibition spaces and tourist facilities.

- ○

- Implementation of efficient logistics to ensure a continuous supply and distribution of craft products [50].

- ○

- Capacity Building and Skill Development:

- ○

- Offering training to artisans, chefs, and other professionals to enhance their technical and management skills.

- ○

- Promotion of entrepreneurship and business management in the sector.

- ○

- Monitoring and Evaluation:

- ○

- Establishment of regular monitoring mechanisms to assess the progress and effectiveness of strategies [51].

- ○

- Conducting consumer satisfaction surveys and economic analyses to identify areas for improvement.

The operation of a cultural market on an island such as Ilha de Moçambique must align with principles of sustainable tourism, community involvement, regulation, and education. By embracing these strategies, we can effectively preserve the cultural heritage of the island and discourage the sale of invaluable artefacts. This multi-faceted approach could ensure the protection of the island’s historical treasures while also fostering a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of its shared human history. It is not merely about safeguarding artefacts but also about celebrating the common heritage for the benefit of present and future generations.

8. Conclusions

The main focus of this paper has been on how to integrate the preservation and conservation of the built heritage of Ilha de Moçambique with commercial activities. The island has long been viewed as a marketplace, and remnants from the past, namely feiras, continue in the form of the many markets and modern feiras on the island today. As shown, marketing is central to daily life and conservation strategies should be informed by this. Commerce on the island includes a diversity of natural resources, from crafts, vegetables, fruit, seafood, cosmetics, and a variety of imported utilitarian goods, including textiles from Tanzania, cars from Japan, motorbikes from China, and bicycles from India. These products meet the everyday needs of the island’s inhabitants while also continuing a long tradition of overseas trade contacts and cultural interactions.

Maintaining the integrity and authenticity of the built heritage, as per UNESCO requirements for maintaining World Heritage status, should be combined, therefore, with interventions that help meet the everyday needs of the island’s inhabitants. For the processes of monitoring and evaluating the state of conservation of the island’s physical heritage to be recognised by the community a plan directed at using heritage to benefit local inhabitants needs to be developed. It is our obligation to find alternatives for them to survive, but without encouraging them to sell their unique archaeological heritage.

We have argued that conceptualising the island as a ‘marketplace’ offering its heritage assets as one of several commodities on sale (in the form of an enriched experience for tourists and inhabitants alike) builds on the island’s unique history without doing undue harm to these heritage assets. It can also be achieved in combination with other strategies toward developing heritage industries (such as crafts and souvenir productions), based on local skills and cultural traditions so that local communities can generate their own income. The increased demand from tourists for ‘antiquities’, such as beads, old coins, and porcelain, needs to be challenged. The sale of artefacts is common at marketplaces and sites along the beach. Visitors are not aware of the scientific value of chance finds. An additional solution, outlined above, is the creation of a cultural marketplace. This could also involve the development of new industries, such as producing replicas for sale in place of the archaeological items, with the income generated returning to those making the replicas and visitor fees used to help sustain management activities.

Identifying how to help local people differentiate between items that can and should not be sold demands serious planning of a marketplace on the island with innovative experiences in the spirit of the RftD approach. Most of the very rich results of these projects still await permission from their authors to be used. However, there are good experiences from other projects inspired by the RftD approach, such as the investigation led by Zacarias Ombe aiming to develop ecosystem services in Chongoene. This helped the design of ongoing work (funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation [52]) aimed at creating a community-run craft and seafood cultural market, with the specific goals of enabling social development and ecosystem services. The main purpose of the development of a formal market at Chongoene and Xai-Xai is to offer better opportunities for local communities compared to an informal market system as found across Mozambique, on the grounds that a formal cultural market can reduce the uncertainties associated with informal markets, and so better serve local communities while at the same time helping to protect heritage. Ilha de Moçambique offers even greater possibilities to accomplish these goals and to better marry heritage protection with sustainable social and economic development.

Author Contributions

S.M.—Conception, Design, Investigation, Analysis, Interpretation, and Writing—original draft. M.R.—Designing a model for a Cultural Market, Investigation, Analysis, and Interpretation. A.M.—Analysis, Interpretation, and Editing. P.L.—Investigation, Interpretation, Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, being the result of work experience in Ilha de Moçambique and litera-ture review.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the following for their kind support: Saíde Selemane for the images included in the text and Silva Mutombene for assisting in processing them for publication. Varsil Marcos assisted with preparation of the map. Énio Tembe engaged in helpful discussions on the concepts of a cultural market. Additional information about the markets and the products being sold in Ilha de Moçambique were obtained from Cláudio Zunguene, the Director of GACIM, and his assistant, Nicotelmo Baltazar. Celso Simbine for discussing the challenging situation on the protection of Ilha de Moçambique archaeological artefacts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Hougaard, J. (Ed.) Ilha de Moçambique: Relatório—Report 1982–85; Secretaria de Estado da Cultura—Moçambique: Maputo, Mozambique; Arkitektskolen in Aarhus: Aarhus, Denmark, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, S. Ilha de Moçambique, Património Cultural Mundial; Ministério da Cultura, Direcção Nacional do Património Cultural: Maputo, Mozambique, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alpers, E.A. Ivory and Slaves: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angelese, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cachat, S. Un Heritage Ambigu: L’île de Mozambique, la Construction du Patrimoine et ses Enjeux. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de la Réunion, Saint-Denis, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chami, F. The Tanzanian Coast in the First Millennium ad: An Archaeology of the Iron-Working Farming Communities: With Microscopic Analyses by Anders Lindahl; Studies in African Archaeology 7; Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis: Uppsala, Sweden, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, R.T. Northern Mozambique in the Swahili World: An Archaeological Approach; Studies in African Archaeology 4; Eduardo Mondlane University: Maputo, Mozambique; Central Board of National Antiquities: Stockholm, Sweden; Sociatis Archaeologica Uppsaliensis: Uppsala, Sweden, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, N. O Caso do Muenemutapa; Tempo, Departamento de História da Universidade Eduardo Mondlane: Maputo, Mozambique, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Radimilahy, C. Mahilaka: An Archaeological Investigation of an Early Town in Northwestern Madagscar; Studies in African Archaeology 15; Department of Archaeology and Ancient History: Uppsala, Sweden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mahumane, C.; Simbine, C. (Re-)interpreting the Artefact Collection of the Nossa Senhora da Consolação Wreck (1608). Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373312156_Re-interpreting_the_Artefact_Collection_of_the_Nossa_Senhora_da_Consolacao_Wreck_1608 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Madiquida, H. Archaeological and Historical Reconstructions of the Foraging and Farming Communities of the Lower Zambezi. From the Mid-Holocene to the Second Millennium AD; Studies in Global Archaeology 21; Department of Archaeology and Ancient History: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mudenge, S.I. The role of foreign trade in the Rozvi Empire: A reappraisal. J. Afr. Hist. 1974, 15, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutal, S. Ilha de Moçambique World Heritage Site. A Programme for Sustainable Human Development and Integral Conservation; Global Report; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Honwana, L.B. Prefácio. Ilha de Moçambique-Relatório-Report 1982–85; Secretaria de Estado da Cultura: Maputo, Mozambique, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Capão, J. Ilha de Moçambique: Sem desenvolvimento não há conservação. Arquivo 1988, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L. Algumas notas sobre a Ilha de Moçambique- Património Histórico Nacional em degradação acelerada. Arquivo 1988, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jopela, A.; Rakotomamonjy, B. Plano de Gestão e Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique 2010–2014; Ministério da Cultura: Maputo, Mozambique, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sollien, S.E. The Macuti House, Traditional Building Techniques and Sustainable Development in Ilha de Mocambique. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 17th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium: Heritage as Driver of Development, Paris, France, 27 November–2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Island of Mozambique. Management and Conservation Plan 2022–2027; Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Maputo, Mozambique, 2023.

- Mahumane, C. New Approaches to Protect Endangered Shipwrecks Around Mozambique Island. In Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Management on the Historic and Arabian Trade Routes; Parthesius, R., Sharfman, J., Eds.; Springer: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; WHC: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Creative Economy Report 2008: The Challenges of Assessing the Creative Economy: Towards Informed Policymaking; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Machado, J.; Braga, S. Comunicação e Cidades Património Mundial No Brasil; Monumenta, IPHAN: Brasília, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, S.; Hougaard, J.; Jopela, A. The Implementation of the Historic Urban Landscape of the Island of Mozambique. In Reshaping Urban Conservation. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action. Creativity, Heritage and the City; Pereira Roders, A., Bandarin, F., Eds.; UNESCO, WHC: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto nr. 28/2006, de 13 de Julho: Cria o Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique e Aprova o Respectivo Estatuto Orgânico; Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2006.

- Wane, M. (ARPAC-Instituto de Investigação Sócio Cultural, Maputo, Mozambique). Personal communication, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oers, R.V. Swahili Historic Urban Landscapes-Applying HUL in East Africa. In Swahili Historic Urban Landscapes. Report on the Historic Urban Landscapes Workshops and Field Activities on the Swahili Coast in East Africa 2011–2012; Van Oers, R., Haraguchi, S., Eds.; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto nr. 54/2016, de 28 de Novembro: Aprova o Regulamento Sobre a Classificação e Gestão do Património Edificado e Paisagístico da Ilha de Moçambique, o Glossário, o Mapa da Área de Protecção Costeira, o Mapa das Praias Abertas e Enfiamentos Visu-ais, o Mapa de Infraestruturas Viárias, o Catálogo dos Edifícios Classificados da Ilha de Moçambique da Cidade de Pedra e Cal. Boletim da República. I Série, No. 142; Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2016.

- Henderson, J.; Breen, C.; Esteves, L.; La Chimia, A.; Lane, P.; Macamo, S.; Marvin, G.; Wynne-Jones, S. Rising from the Depths Network: A Challenge-Led Research Agenda for Marine Heritage and Sustainable Development in Eastern Africa. Heritage 2021, 4, 1026–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossa, W.; Ribeiro, M.C. Modos de Olhar. Walter Rossa & Margarida Calafate Ribeiro. In Patrimónios de Influência Portuguesa: Modos de Olhar; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2015; pp. 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, S.L. Macuti town and community involvement in the conservation of Mozambique Island. In Academic Papers: International Conference on “Living with World Heritage in Africa”; 40 years World Heritage Convention; African World Heritage Fund (AWHF) and the Department of Arts and Culture: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Heathcott, J. Historic Urban Landscapes of the Swahili Coast. New frameworks for Conservation. In Swahili Historic Urban Landscapes. Report on the Historic Urban Landscapes Workshops and Field Activities on the Swahili Coast in East Africa 2011–2012; Van Oers, R., Haraguchi, S., Eds.; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Selemane, S. (Ilha de Moçambique Archaeology, Research and Resource Center (CAIRIM), Ilha de Moçambique, Mozambique). Personal communication, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Simbine, C. The maritime archaeology of Mozambique Island: Lessons from the commercial gathering of beads and porcelain for tourists. In Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Management on the Historic an Arabian Trade Routes; Pathersius, R., Sharfman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 77–98. Available online: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/13840815 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Lei nr. 10/88 de 22 de Dezembro, que Determina a Protecção Legal dos Bens Materiais e Imateriais do Património Cultural Moçambicano. Boletim da República nr. 51 (I Série); Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 1988.

- Bouchenaki, M. Foreword. In Sharing Conservation Decisions. Lessons Learnt from an ICCROM Course; Varoli-Piazza, R., Ed.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2007; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto nr. 55/2016, de 28 de Novembro que Aprova o Regulamento Sobre a Gestão de Bens Culturais Imóveis, Boletim da República n.º 142 (I); Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2016.

- Resolução nr. 12/2010, de 2 de Junho que Aprova a Política de Monumentos. Boletim da República nr. 22 (I); Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Moçambique, 2010.

- Nguirazi, T. Conservation of Traditional Buildings on the Island of Mozambique: A Case Study of Macuti City; University of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simbine, C. (Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo, Mozambique). Personal communication, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Tourism for Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-tourism-development (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Hall, C.M.; Lew, A.A. Sustainable Tourism: A Marketing Perspective; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. Tourism and Regional Development: New Pathways; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Khan, H.U.; Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Ahmed, M.F. Sustainable tourism policy, destination management and sustainable tourism development: A moderated-mediation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Fight against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/fight-against-illicit-traffic-cultural-property (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Messenger, P.M. The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property: Whose Culture? Whose Property? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Selin, S. Strategic Management in the Arts. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2003, 5, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. (Ed.) Building Tourism and Resilience in Coastal Communities: Concepts, Theories and Practices; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, A.C.; Hutton, T.A. Reconceptualising the Relationship between the Cultural Economy and Cities. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2310–2327. [Google Scholar]

- Radbourne, J.; Glow, H. (Eds.) The Audience Experience: A Critical Analysis of Audiences in the Performing Arts; Intellect Books: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan Publications: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, D. Cultural Policy Evaluation: A Review of Literature and Trends. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2006, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Macamo, B.; Raimundo Mutombene, S.; Macamo, S.; Lane, P. (in prep.) Stimulating retailing business for heritage preservation: Community social and economic benefits in the Xai-Xai and Chongoene beach areas, Gaza Province, Mozambique. In Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists, Houston, TX, USA, 1–6 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).