Abstract

Background and Clinical Significance: Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a mitochondrial disorder characterized by acute or subacute bilateral central vision loss, typically in young males. Multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) are immune-mediated demyelinating diseases that may present with optic neuritis and myelitis. Although distinct in etiology, recent evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation can overlap, giving rise to combined phenotypes such as LHON-MS (also known as Harding’s disease). Case Presentation: We report a 42-year-old man who initially presented in 2018 with right-eye pain and severe visual loss diagnosed as idiopathic optic neuritis. Despite corticosteroid and plasma-exchange therapy, visual recovery was poor, and he was maintained on azathioprine. One year later, he developed visual flashes and left-eye visual loss with bilateral optic nerve thinning on OCT. Genetic testing revealed a pathogenic MT-ND4 (m.11778G>A) mutation, confirming LHON. In 2021, he presented with ascending lower-limb numbness and bladder urgency. MRI demonstrated a central thoracic cord lesion at T11, consistent with acute transverse myelitis, while serum AQP4 and MOG antibodies were negative. CSF showed five unique oligoclonal bands. The diagnosis of LHON-MS overlap was established, and he was treated with corticosteroids followed by rituximab with clinical stability thereafter. Conclusions: This case highlights the diagnostic challenges of LHON with atypical optic neuritis initially followed by the development of demyelinating disease. Red flags such as poor visual recovery, bilateral or sequential optic neuropathy, and steroid-refractory episodes should prompt genetic testing to rule out LHON. Recognition of the mitochondrial–immune overlap is essential for accurate diagnosis, counseling, and an appropriate therapeutic strategy.

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a mitochondrial disorder causing acute or subacute bilateral central vision loss, typically in young males. Multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) are immune-mediated demyelinating diseases that may present with optic neuritis and myelitis. Although pathophysiologically distinct, mounting evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation intersect, giving rise to overlapping phenotypes collectively referred to as LHON-MS or Harding’s disease [1,2]. This small but well-described subgroup of patients exhibits both LHON mutations seen in mitochondrial hereditary diseases and inflammatory demyelinating episodes mimicking MS, exceeding coexistence by chance [2]. Published reports describe a heterogeneous group of patients, most of the time diagnosed as MS, and many years later, a retrospective diagnosis of LHON is made [3,4]. Most of these cases are female, with a median age of diagnosis of 30, with painless vision loss [2]. In this case, we present a male patient who presented with painful vision loss suggestive of optic neuritis with poor recovery; a few years later, he had a demyelinating attack with a positive CSF study, making the diagnosis of demyelinating disease on top of the existing LHON diagnosis.

Clinical Significance: This case illustrates the diagnostic dilemma that can be seen in such cases: the patient was initially diagnosed with idiopathic optic neuritis until one year later, when he had involvement in the other eye, warranting genetic testing that confirmed the diagnosis of LHON. Subsequently, this patient was diagnosed with an LHON-MS overlap after developing typical symptoms of demyelinating disease. Increasing awareness of the possible overlaps can improve the diagnostic accuracy, encourage neurologists to consider LHON testing, and improve the treatment pathway.

2. Case Presentation

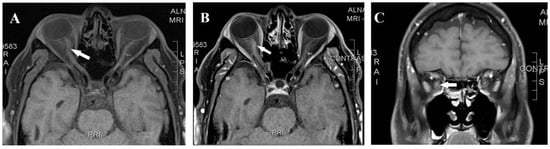

A 42-year-old man presented in February 2018 with right-eye pain and progressive visual loss over two weeks. The patient was in his usual state of health with no medical illness other than chronic migraines managed by topiramate. He has no family history of autoimmune disease or neurological disease but mentioned a case of blindness in a maternal uncle, which was attributed to glaucoma. Upon examination, visual acuity was reduced to hand motion OD and 20/20 OS, with a right relative afferent pupillary defect. Fundus examination showed optic disk hyperemia in the right eye; the left eye was normal. Visual evoked potential (VEP) showed an absent right-eye response, and the left-eye P100 = 112 ms. Automated Humphrey visual field testing showed a dense central scotoma in the right eye. Laboratory evaluation and a routine autoimmune panel, like antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), in addition to negative aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4 Ab) and anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies, were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was unremarkable, including negative oligoclonal bands. Brain and spinal MRI were normal, while orbital MRI revealed right-optic-nerve enhancement and mild enlargement (Figure 1). Moreover, metabolic, toxicological, and infectious serological studies were negative. He was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone and plasma exchange with minimal recovery (the right eye improved from hand motion to counting fingers at a 50 cm distance). Azathioprine at a dose of 2 mg/Kg was started for the presumptive diagnosis of idiopathic autoimmune optic neuritis.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging axial T1 pre-contrast (A), axial T1 post-contrast (B), and coronal T1 post-contrast (C) showed right-optic-nerve mild enhancement and enlargement (arrow).

One year later, in June 2019, he developed visual flashes and headaches affecting the left eye, with decreased vision. MRI showed no new lesions. Upon examination, vision acuity was 20/200 OD and 20/60 OS with a right relative afferent pupillary defect. Fundus examination showed a pale right optic disk and a subtle temporal pallor left optic disk. VEP demonstrated delayed P100 latency (159 ms) in the left eye and a persistent absent response in the right. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed diffuse retinal nerve fiber layer thinning bilaterally. Automated Humphrey visual field testing showed a persistent dense central scotoma in the right eye and a temporal defect in the left eye. The patient received another course of IV methylprednisolone, followed by oral tapering. Due to the development of bilateral optic neuropathy and poor recovery, hereditary causes were favored over inflammatory causes. The patient also underwent an extended workup, including repeated autoimmune antibody testing, thyroid, vitamin B12, and infectious etiology, including bacterial, viral, and syphilis, in addition to the CT chest, abdomen, pelvis, and PET scan, which were all inconclusive. Finally, genetic testing (whole-exome and mitochondrial genome sequencing) revealed a point mutation at the m.11778G>A (MT-ND4) gene, confirming the diagnosis of LHON. The patient was advised to stop azathioprine and referred to the genetics clinic for counseling.

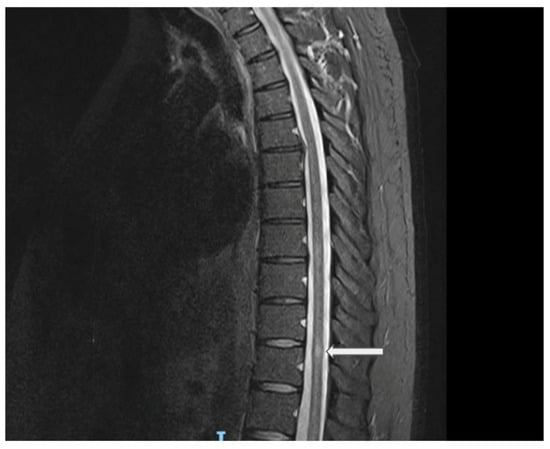

In August 2021, the patient presented with a 10-day history of ascending lower-limb numbness in both legs with some bladder urgency, without weakness or gait disturbance. Neurological examination showed preserved strength and reflexes with sensory impairment to the knees bilaterally; at that time, the estimated expanded disability status scale (EDSS) was 2.5. The brain MRI demonstrated no demyelinating lesions. The spine MRI revealed a small T2-hyperintense lesion at T11 with subtle cord expansion, minimal post-contrast enhancement, and a questionable ill-defined lesion at T8 (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute transverse myelitis. Serum AQP4 and MOG antibodies were again negative. CSF was positive for five unique OCBs. An extended diagnostic workup was performed to exclude alternative etiologies of myelitis, including ANA, ENA, ANCA, ACE, B12/MMA, infectious serologies (HIV, VZV, syphilis, TB), and paraneoplastic screening, all of which were unremarkable. He was treated with intravenous corticosteroids with good improvement. After this episode, the patient was diagnosed with LHON plus a demyelinating disease, most likely LHON-MS or Harding’s disease.

Figure 2.

Sagittal spine MRI (STIR sequence) showing a central thoracic cord lesion with high T2 signal intensity opposite the superior aspect of the T11 vertebral level, associated with subtle cord expansion. Explanation of the arrow figure: central thoracic cord lesion with high T2 signal intensity opposite the superior aspect of the T11 vertebral level.

The patient was started on rituximab every 6 months as a disease-modifying therapy and was counseled on mitochondrial disease management, including the use of idebenone and vitamin supplementation; also, he was advised to discontinue smoking. The patient’s condition has been stable with no further relapses and some improvement in vision. His last assessment showed a vision of 20/200 OD and 20/20 OS, and he recognized 0/16 color plates in the right eye and 16/16 in the left eye with a pale right optic nerve and mild left-optic-nerve temporal pallor. Otherwise, his neurological exam continues to be the same, with only sensory abnormality estimated at EDSS = 2.

3. Discussion

LHON is a mitochondrially inherited disorder due to a point mutation in the mtDNA. LHON is characterized by sequential optic nerve involvement with variable degrees of visual impairment. However, systemic involvement is not uncommon and is referred to as LHON+. The most common organ involvements are the cardiac and nervous system [5]. Several reports mentioned the possible coexistence of mitochondrial disease, LHON, and demyelinating diseases like MS. This coexistence has been given a specific name: Hardig’s disease. The pathophysiology of LHON involves a gene mutation that causes mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in selective retinal ganglion cell apoptosis [6]. Although this point mutation causes neurodegeneration, it makes patients prone to neuroinflammation and possibly to developing MS [6]. The relation between neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction remains hypothetical rather than established pathogenic pathways. Evidence from experimental models of multiple sclerosis showed that mitochondrial dysfunction is present even before overt clinical demyelination occurs [7]. Similarly, several studies reviewed the potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction in MS, highlighting that mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies and altered mitochondrial dynamics may contribute to neurodegeneration in MS, although the direct causation of these associations remains incompletely understood [8]. While these observations offer biologically plausible explanations for cases of LHON–MS overlap, a definitive link is still under investigation, and current evidence should be interpreted as supportive but not conclusive. A review of 103 cases with LHON found that three mutations (m.11778G>A, m.3460A>G, and m.14484T>C) are associated with demyelinating symptoms like MS. They reported that MS symptoms in these patients are almost similar to any patient with MS, with only a more severe visual involvement [1]. Our patient presented initially with unilateral severe optic neuritis, manifesting as marked vision loss, eye pain, subacute onset, and abnormal MRI features. These features initially deviated the working diagnosis from a hereditary neurodegenerative etiology. An MRI of the brain in isolated LHON is expected to be normal or can show some optic nerve atrophy at later stages [9]. However, the description of optic nerve hyperintensity, especially retro-chiasma and chiasm enlargement and T2 signals in MRI, which can mimic optic neuritis, has been described in few cases of LHON [10,11]. These MRI findings can cause diagnosis complexity and expose the patient to multiple immunotherapy treatments; the lack of visual improvement despite the use of immunotherapy like steroids or plasma exchange should prompt considering a genetic test for LHON. A previous report by Lai and colleagues addressed the main similarities and differences in clinical features between two groups of LHON and optic neuritis Chinese patients during the acute stage [12]. Evaluation of clinical features of both LHON and inflammatory optic neuritis could clarify the overlap between both conditions, especially in the acute stage (Table 1) [12,13,14].

Table 1.

Features of typical idiopathic optic neuritis vs. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) in adults.

To illustrate the diagnostic complexity of our case, we reviewed published reports describing LHON–MS overlap (Harding’s disease). Table 2 summarizes representative cases and highlights how phenotypic variability, diagnostic delay, and overlapping MRI/CSF features may complicate accurate classification. These comparisons underscore the distinctive features of our patient, particularly the confirmation of a pathogenic LHON mutation prior to the onset of myelitis and the presence of optic nerve enhancement—an uncommon but increasingly recognized challenge in differentiating LHON from immune-mediated optic neuritis.

Table 2.

Published LHON–MS overlap cases compared with the present case.

Patients with LHON-MS and patients with MS share almost similar features on brain MRI, fulfilling the 2017 McDonald’s diagnostic criteria for MS [17]. Our case had only a spinal cord lesion and no other lesions to fulfill dissemination in space (DIS) criteria (requiring at least one lesion in two topographical locations typical for MS) and had a positive oligoclonal band in the CSF study at the time of the transverse myelitis presentation, which could substitute for dissemination in time [12]. A more recently published diagnostic criterion for MS, the 2024 revisions of the McDonald Criteria, added the presence of an optic nerve lesion on MRI as a fifth topographical lesion for dissemination in space (DIS) [18]. So our case can be diagnosed as MS after excluding any alternative diagnosis according to the newer version of the 2024 McDonald Criteria, based on the presence of two lesions (optic nerve and spinal cord) and a positive CSF study. Nevertheless, applying the 2024 McDonald Criteria in this context is challenging. The patient carries a confirmed mitochondrial mutation causing hereditary optic neuropathy, providing a clear alternative explanation for optic nerve pathology. Thus, complete exclusion of a non-MS etiology for optic nerve involvement—one of the essential prerequisites when applying MS diagnostic criteria—cannot be definitively achieved in this case. This overlap between hereditary mitochondrial optic neuropathy and inflammatory spinal cord disease illustrates the diagnostic ambiguity characteristic of LHON-MS overlap syndromes (Harding’s disease). It highlights the need to interpret the 2024 McDonald Criteria cautiously, especially in patients with atypical presentations, to avoid misdiagnosis.

There is not enough evidence to support specific treatment options for Harding’s disease or LHON-MS. Disease-modifying therapy used in MS can be used in addition to a specific treatment for LHON, like a trial of idebenone. Until now, there has been no cure for LHON; idebenone showed some benefit in stabilizing vision, but results have been inconsistent [19].

LHON is a challenging diagnosis, as the initial presentation can mimic multiple sclerosis or other autoimmune demyelinating diseases, like NMOSD or myelin oligodendrocyte antibody-associated disease (MOGAD). In order to reach the diagnosis, an extensive workup to exclude disease mimics and genetic testing is required. Red flags in patients with MS, for example, the presence of severe optic nerve dysfunction or subsequent optic nerve improvements in a patient with MS, may sometimes warrant testing for LHON, as this disease requires a specific approach and genetic counseling. Although LHON–MS overlap syndromes have been previously reported, the sequence observed in our patient is unusual and clinically important. In most published cases, patients are diagnosed with MS (or recurrent optic neuritis) first, and LHON is only recognized later when vision fails to recover. In contrast, our patient had genetically confirmed LHON prior to the development of a typical demyelinating event, which provides a unique window into how mitochondrial neurodegeneration may precede or coexist with central nervous system demyelination.

This case also reinforces the importance of considering LHON in patients with atypical optic neuropathy, particularly when visual recovery is poor, when MRI findings mimic inflammatory disease, or when treatment response is minimal. While ophthalmologists frequently encounter LHON-like presentations, neurologists may be less familiar with the condition, increasing the risk of misclassification as inflammatory optic neuritis or CRION. Increased awareness of LHON testing among neurologists is therefore essential to avoid diagnostic delay and to appropriately interpret subsequent demyelinating events.

4. Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of recognizing that LHON can present in the context of inflammatory demyelinating disease, resulting in a diagnostic overlap known as LHON-MS or Harding’s disease. The initial presentation may resemble autoimmune optic neuritis. However, red flags, such as poor visual recovery, sequential optic nerve involvement, and no improvement with steroids, should prompt consideration of genetic testing for LHON, even in patients who appear to have demyelinating features. Although this case does not present a new or novel diagnosis, it illustrates and reinforces the diagnostic challenges of distinguishing LHON from inflammatory optic neuritis.

What is also unique in this case is the sequence of diagnosis. LHON was genetically confirmed before the patient developed typical inflammatory myelitis, underscoring the need to consider LHON in atypical or poorly recovering optic neuritis. Furthermore, the subsequent development of myelitis and positive CSF oligoclonal bands in this patient describes how mitochondrial dysfunction may predispose to immune-mediated neuroinflammation. Identification of LHON-MS overlap is critical, as it has implications for therapeutic decisions, guides genetic counseling, and helps to avoid unnecessary immunosuppression in cases where inflammation is not the main cause of vision loss.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and W.E.; data collection, H.A.; clinical evaluation and investigation, H.A. and W.E.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A. and W.E.; supervision, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the nature of a single anonymized case report, which does not meet the criteria for research involving human subjects according to institutional policy. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5) to assist with text refinement and language clarity. The authors reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| LHON | Leber hereditary optic neuropathy |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| NMOSD | Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder |

| LHON-MS | LHON associated with demyelinating disease (Harding’s disease) |

| MT-ND4 | Mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4 gene |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| STIR | Short tau inversion recovery |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| GCL | Ganglion cell layer |

| VEP | Visual evoked potential |

| RAPD | Relative afferent pupillary defect |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| OCBs | Oligoclonal bands |

| AQP4 Ab | Aquaporin-4 antibody |

| MOG Ab | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibody |

| ENA | Extractable nuclear antigen |

| ANCA | Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| IVMP | Intravenous methylprednisolone |

| AZA | Azathioprine |

| DMT | Disease-modifying therapy |

| DIS | Dissemination in space (MS diagnostic criterion) |

| DIT | Dissemination in time (MS diagnostic criterion) |

References

- Vanopdenbosch, L.; Dubois, B.; D’Hooghe, M.B.; Meire, F.; Carton, H. Mitochondrial mutations of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy: A risk factor for multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2000, 247, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, G.; Silverman, M.; Lucas, M.; Kazerooni, L.; Yousuf, M.M.; Jafarpour, S.; Santoro, J.D. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and multiple sclerosis: Overlap between mitochondrial disease and neuroinflammation. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1538358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmøy, T.; Beiske, A.G.; Zarnovicky, S.; Myro, A.Z.; Røsjø, E.; Kerty, E. Severe inflammatory disease activity 14 months after cessation of Natalizumab in a patient with Leber’s optic neuropathy and multiple sclerosis—A case report. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Kermode, A.G. Harding’s disease: An important MS mimic. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e228337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, L.; Hazzard, I.; STehrani, N.; Ansari, U.; Ali, A.; Kumar, P.; Ali, N.; Gakhal, G.; Lui, F. Extraocular features of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: A scoping review. J. Biol. Methods 2025, 12, e99010055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargiela, D.; Chinnery, P.F. Mitochondria in neuroinflammation—Multiple sclerosis (MS), leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) and LHON-MS. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710, 132932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghian, M.; Mastrolia, V.; Rezaei Haddad, A.; Mosley, A.; Mullali, G.; Schiza, D.; Sajic, M.; Hargreaves, I.; Heales, S.; Duchen, M.R.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction is an important cause of neurological deficits in an inflammatory model of multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barcelos, I.P.; Troxell, R.M.; Graves, J.S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Multiple Sclerosis. Biology 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arianti, A.; Chuman, H.; Kajihara, N.; Sakamoto, N.; Nao-IM.D, N. Atypical Clinical and Neuroimaging Findings in Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy: A Case Report. JOJ Ophthalmol. 2018, 6, 555698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Yamada, K. Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy With Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings Suggestive of Optic Perineuritis and Optic Neuritis: A Diagnostic Challenge. Cureus 2025, 17, e80439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, C.; Heran, F.; Habas, C.; Bejot, Y.; Sahel, J.; Vignal-Clermont, C. MRI of the Optic Nerves and Chiasm in Patients with Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. J. Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2018, 38, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy and Optic Neuritis: Similarities and Differences of Clinical Characteristics. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18070523/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Savini, G.; Barboni, P.; Valentino, M.L.; Montagna, P.; Cortelli, P.; De Negri, A.M.; Sadun, F.; Bianchi, S.; Longanesi, L.; Zanini, M.; et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer evaluation by optical coherence tomography in unaffected carriers with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy mutations. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglese, M.; Rovaris, M.; Bianchi, S.; La Mantia, L.; Mancardi, G.L.; Ghezzi, A.; Montagna, P.; Salvi, F.; Filippi, M. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetisation transfer imaging, and diffusion weighted imaging correlates of optic nerve, brain, and cervical cord damage in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2001, 70, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chang, M. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy misdiagnosed as optic neuritis and Lyme disease in a patient with multiple sclerosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 11, e227109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, P.M.; Fraser, J.A.; Lee, D.H.; Morrow, S.A. Severe sequential visual loss in MS co-diagnosis of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54, e69–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alorainy, J.; Alorfi, Y.; Karanjia, R.; Badeeb, N. A Comprehensive Review of Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy and Its Association with Multiple Sclerosis-Like Phenotypes Known as Harding’s Disease. Eye Brain 2024, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalban, X.; Lebrun-Frénay, C.; Oh, J.; Arrambide, G.; Moccia, M.; Pia Amato, M.; Amezcua, L.; Banwell, B.; Bar-Or, A.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2024 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopstock, T.; Metz, G.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Büchner, B.; Gallenmüller, C.; Bailie, M.; Nwali, N.; Griffiths, P.G.; von Livonius, B.; Reznicek, L.; et al. Persistence of the treatment effect of idebenone in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2013, 136 Pt 2, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).