Abstract

Applicable recommendations play a key role in improving training and procedures used in civil protection. Since 1 January 2025, the Law on Civil Protection and Civil Defense has been in force in Poland. It responds to the experience of current threats, including the war in Ukraine, the 2024 floods in Western Poland, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other crises. The Act systemically regulates the problem of building social resilience, which must be developed and applied regarding today’s modern threats. The primary actor in civil protection is the fire brigade system, in which volunteer firefighters are recruited from local communities and act for their benefit. In this context, it is interesting to ask whether and what solutions should be applied in order to improve the effectiveness of the training and exercise system of volunteer fire brigades (TSOs) in the field of civil protection and crisis management. The aim of this investigation was to develop evaluations and applicable recommendations to improve the effectiveness of the training system for volunteer firefighters based on a survey of volunteer firefighters in the Cracow Poviat. Two survey diagnostic techniques were used: expert interviews and questionnaire research. The findings were compared with the results of an analysis of source documents obtained in TSO units. The expert interviews covered all chief fire officers of the municipalities in the Cracow Poviat. The paper begins with an introduction and a systematic literature review. The conclusions consist of the proposal of applicable changes in the scope of basic, specialist, and additional training. Areas of missing training are also identified. The firefighters’ knowledge of crisis management procedures is verified, deficiencies are identified, and applicable changes in the organization of field exercises are proposed.

1. Introduction

Undoubtedly, the development of scientific and technological achievements, including artificial intelligence, has had an impact in improving the effectiveness of life protection—exemplified by the use of imaging methods for fire detection and simulation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] or mapping flood risks [10]. The efforts of the relevant authorities are moving towards developing appropriate regulations to protect life and property. For this reason, strategic decisions, including civil protection and crisis management, play an important role in ensuring security in the broadest sense [11,12,13,14], as a consequence of which appropriate action schemes and legal regulations are successively developed. In the Polish legal system, the legislator has defined the concepts of both civil protection and crisis management. Civil protection is a broader category of activity, as it is related to the performance of the functions of state security bodies in peacetime [15]. Crisis management, on the other hand, is the activity of public administrations in peacetime [16] but is associated with a specific threat referred to as a crisis situation. A crisis situation is a threat that exceeds the forces and resources of those responsible for its combat [17] and thus implies a need for cooperation between public administration bodies [18]. Therefore, it is necessary for civil protection and crisis management that public administration bodies are competent to perform their own tasks, as well as to perform tasks in cooperation with other entities. Thus, a distinction should be made between training, shaping competence in one’s own tasks and exercises, and preparing for cooperation with other entities.

One of the civil protection and crisis management entities in Poland is the voluntary fire brigade. According to current data, there are 15,973 voluntary fire brigades in Poland [19] as of 1 January 2025. A total of 5155 units are included in the professional National Rescue and Firefighting System (NRFS) [20]. Considering that the country is divided into 2477 municipalities, statistically, there are 6.45 TSO units per municipality, including 2.08 units integrated into the system. This fact testifies to the operational potential of the TSOs and the proximity of the units to potential hazards. Therefore, it is considered important, from a cognitive point of view but also from a practical point of view, to determine whether and how the effectiveness of the training and exercises of TSOs in the field of civil protection and crisis management can be improved. This is the main research problem considered in this article, for which the following main research hypothesis was adopted: the team’s preparedness for its own tasks and for crisis management is significantly influenced by the content of the programs, the quality and usefulness of the training, the level of knowledge of crisis management procedures, and the experience of TSO firefighters. In view of the main hypothesis thus stated, four specific hypotheses are formulated:

- H1: There is a significant relationship between preparation in the form of training and exercises and the assessment of TSOs’ preparedness for their own tasks and TSO crisis management;

- H2: There is a significant relationship between the experience of TSO firefighters and their ratings of training and exercises;

- H3: There is a significant relationship between the ratings of TSO firefighters of the quality and usefulness of training and their ratings of their preparedness for their own tasks;

- H4: There is a significant relationship between TSO firefighters’ evaluations of their knowledge of crisis management procedures, their evaluations of their exercises, and their evaluations of the readiness of these units to carry out crisis management tasks.

The aim of this work is as follows: by verifying these hypotheses, to develop assessments and applicable recommendations to improve the effectiveness of the training system for volunteer firefighters.

To verify the hypotheses, two diagnostic survey techniques (expert interviews and a questionnaire survey) were adopted, supported by an analysis of primary documents obtained from the municipalities and TSO units. The expert interviews covered the chief fire officers of TSOs in 17 municipalities in the Cracow Poviat (Table 1). The number of expert interviews was due to the fact that the Cracow district is divided into 17 TSO commands. Thus, the survey was conducted on 100% of the research sample. Due to the fact that chief fire officers are recruited among volunteer firefighters and are not part of the state fire service, it was assumed that no social desirability bias (SDB) study was necessary. The expert interviews consisted of open-ended evaluation questions and requests for recommendations on the TSO training program and exercise system. During the interviews, access to exercise documentation was also requested. The questions referred to recommendations for changes in TSO training programs, serving to verify H1. The questionnaire survey was conducted among 365 firefighters from the Cracow Poviat, maintaining the required minimum size of the research sample of n = 361. The survey was used to verify H2, H3, and H4.

A literature review was conducted for the purpose of this study. The method of obtaining sources and the methodology of their analysis was described in an earlier article [21]. The scope of research interest was narrowed only to publications included in the indexed Scopus database. In practice, the literature was limited to English-language publications only. Papers published up to 24.07.2024 were considered for the study. The search for articles that fell within the research interest was applied by combining the following phrases:

(1) search word 1: “volunteer fire brigade” or “volunteer fire service” or “volunteer firefighter” or “volunteer fire brigade” or “territorial fire service organization”;

(2) search word 2: “training” or “exercise”.

This resulted in 56 papers with different research scopes. The term “volunteer” was distinguished from the state fire service. “Volunteering” is understood here as a social activity but not as an activity of state bodies, which also corresponds to the divisions between voluntary and career firefighters used in the literature [22]. Due to the research perspective adopted (as explained in the Introduction), the literature review included publications that dealt with training, shaping competence in the fire service’s own tasks and exercises, and preparing for cooperation with other entities. The understanding of “training” or “exercise” as physical exertion was excluded from the investigation.

In the literature analysis, the occurrence of the accepted understanding of both words 1 and 2 in the article was first verified. After reviewing the title, abstract, and keywords, 28 publications were rejected from further full-text analysis. These studies concerned the modeling of the biomass market in Małopolska, a web-based program to measure weight change among firefighters [23], a motivation system for firefighters [24], and personal development or physical exercise, including research during exercise training (here, the objective of the study was not to train firefighters but to examine the fitness of their organism) [22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Also excluded from the research were articles in which the word “training” was used only in terminological distinctions and training was not the focus of the study [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] or situations where the word “training” appeared only in the study’s conclusions [44,45,46,47,48].

After the analysis of the titles, abstracts, and keywords, 28 publications were qualified for further full-text analysis. The results of the analysis showed that the publications could be grouped. The broadest category of texts was related to research on the health of firefighters, with a particular emphasis on cardiovascular research and research that measured exercise indices during training. Fourteen of the 28 articles were assigned to this area, representing 50% of all publications. Another highlighted thematic group was publications on management, including ways to motivate volunteer firefighters. This amounted to 6 out of 28 publications, which represented 21.43%. One publication fell into the area of safety and accidents, representing 3.57% of the publications, and three articles fell into the category of psychological problems (representing 10.71%). Two publications were related to digital applications (7.14%). In addition, two publications were placed in the category “other”, representing 7.14%. The thematic breakdown is presented in Table 1.

In terms of the research methodology, there was one (3.57%) literature review [49], five (17.86%) case studies [50,51,52,53,54], and five (17.86%) surveys [46,48,55,56,57], and the remaining 17 articles (60.71%) used field research.

Table 1.

Thematic division of the literature on the subject.

Table 1.

Thematic division of the literature on the subject.

| Problem Area | Characteristic | Related Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Applications supporting firefighters | Evaluations of volunteer firefighters of various platforms and applications to support firefighter safety. | [58,59] |

| Health problems among volunteer firefighters | Research on the cardiovascular performance of volunteer firefighters and performance studies during exercise tests, including high-temperature conditions. | [43,49,57,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Management problems | Research on professional motivation and motivation, crisis communication, and the management skills of volunteer firefighters. | [48,51,52,53,54,70] |

| Psychological problems | Research on pre-retirement equipment care and research on equipment care among volunteer firefighters and professional firefighters; research on stress. | [56,65,71,72] |

| Safety and accidents | Deaths during exercises. | [50] |

| Other | Training in the management of broken teeth; research on mask adhesion. | [55,73] |

After a full-text analysis of the publications, it was found that some of them were not devoted to training and exercises themselves, but training was applied as a research tool or provided a setting for other findings. This was the case for publications on the following topics: testing the functionality of mobile applications under field conditions [58], determinants of stair-climbing speeds [64], and heat stress in the training environment [68,69,71,72]. Trainees have also been studied in terms of their skills or psychophysical characteristics [56,60,61,62,63,65,66,67,74], including the causes of death of exercise participants [50].

Taking into account that the aim of our research was to develop an evaluation and applicable recommendations to improve the effectiveness of volunteer firefighter training, publications that aligned with this research interest were considered. This included studies in which the relationship among group training experiences and the identification of affective, cognitive, and behavioral groups among volunteer firefighters was discussed [70]; the effectiveness of online and classroom training was compared [59]; the effectiveness of training in shaping firefighters’ knowledge of cardiovascular disease was tested by performing a pre- and post-test [57]; means of organizing training to increase volunteer firefighter recruitment were discussed [53]; and the extent of accidents during firefighter training and exercises was investigated [49].

Among the publications that were thematically close to the present research topic, there were those focused on improving training programs. Here, such studies focused on improving the effectiveness of a training program in communicating with autistic people in crisis situations [54], improving a training program for firefighters with special paramedic training to deal with broken teeth [55], physiological studies on improving the Candidate Physical Ability Test [75], and a training program for incident commanders [76].

The literature review revealed several research gaps. In the literature review, no single publication on the Polish training system for volunteer firefighters was noted. No articles related to the comprehensive improvement of the firefighter training system were noted (only partial selected proposals were referred to in the analyses) [54,55,75,76]. No publications dealing with field exercises were noted. No publications were noted that dealt with crisis management. Thus, the present publication, which provides an evaluation of the Polish training and exercise system for TSOs in the field of civil protection and crisis management, is intended to fill the research gaps indicated. Thus, the research perspective adopted distinguishes the present article from publications already included in the literature on this subject.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study was to establish applicable recommendations to improve the effectiveness of TSO training and exercises based on the verification of the knowledge and opinions of volunteer firefighters from the Cracow Poviat. The study was carried out for a population of 5836 volunteer firefighters from the Cracow Poviat, collected (according to data at the end of 2023) in 171 units of the voluntary fire brigade, 45 of which were included in the National Rescue and Firefighting System (NRFS). A detailed summary is included in Table 2 [77].

Table 2.

Overview of TSOs in the Cracow Poviat.

To verify research hypothesis H1, an expert interview was conducted with 17 municipality fire chiefs, representing 100% of the study population. Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 were verified based on a questionnaire survey of a population of 5836 volunteer firefighters from the Cracow Poviat. The minimum sample size was determined according to the following formula:

where Nmin—minimum sample size, Np—population size from which the sample is taken, α—confidence level, f—fractional size, and e—assumed maximum error, expressed as a fraction.

A 95% confidence level, a fraction size of 0.5, and a maximum error of 5% were assumed to ensure that the study was representative:

The survey was conducted from 1 March 2024 to 6 May 2024 using random sampling on a sample of 365 crisis firefighters, which allowed it to be considered representative under the assumptions outlined above.

Social studies evaluated basic, specialized, and additional training programs. Their presentation and analysis constitute a reference point for the research results. Training programs were provided by the Fire Brigade Headquarters.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Training and Exercise System

The training of volunteer fire brigades has been implemented since 2021 at four levels: basic, specialist, command, and additional. Table 3 presents a summary of the TSOs’ training [78].

Table 3.

Training of TSOs.

Passing the basic examination is required to participate in rescue operations and actions. It is important to clarify at this point that the research carried out for the purposes of the publication presented here only involved people who participated in rescue operations, meaning that they had at least completed basic training.

Until 2020, the “Basic Training Programme for Volunteer Fire Service Rescue Firefighters”, developed in 2015, was in force [79]. On 4 March 2022, based on the evaluation of the “Basic Training Programme for Volunteer Fire Service Rescue Firefighters” approved on 17 November 2015 by the Chief Fire Officer of the State Fire Service, the teaching plan for candidates for volunteer fire service rescue firefighters changed—it is still in force [80]. The thematic scope of the program has changed, and the number of training hours has increased. It is worth noting the change in occupational health and safety training. The number of fatal accidents among TSO rescue firefighters, which has increased dramatically since 2020, has prompted discussions on the principles of safe behavior for TSO rescue firefighters.

The basic training program currently comprises 133 h of instruction, including 64 h of theoretical instruction and 69 h of practical instruction. Training topics can be grouped into the following categories: occupational health and safety and pre-medical assistance (14 h, including 4 h practical); the organization of guard work (13 h, including 7 h practical); fire protection training (49 h, including 30 h practical); flood protection training (6 h, including 2 h practical); technical rescue training (31 h, including 22 h practical); physical and chemical properties (9 h, including no practical); road traffic hazards and other hazards (6 h, including no practical); and examination (5 h, including 4 h practical) [81]. During the questionnaire, questions about additional training were asked, which also implied an in-depth study of the selected topics of basic training. In this way, an attempt was made to establish possible recommendations for changes in the scope of the program.

The scope of the basic level of training for volunteer fire brigade (TSO) rescue firefighters includes training for drivers and maintainers of rescue equipment for volunteer fire brigades—required only for a TSO rescue firefighter acting as a driver [82].

Specialist training is required for a TSO unit to become a so-called TSO Operational and Technical Unit. Firefighters in this unit must meet the statutory requirements specified for TSO rescue firefighters, allowing them to carry out rescue operations [78].

At the specialist level, the State Fire Service trains TSO rescue firefighters in qualified first aid training, training in cooperation with the Air Ambulance Service, and training that prepares them for the exam that authorizes them to drive a motor vehicle with a total weight allowed greater than 3.5 t [82]. Since 2022, training has been certified separately in cooperation with the Air Ambulance Service of the Independent Public Healthcare Institution [80].

Command-level training, conducted by the State Fire Service, includes training for rescue operation command for volunteer fire brigade rescue firefighters, training for volunteer fire brigade chiefs, and training for the municipal fire protection commander. The purpose of the HRO training is to prepare TSO rescue firefighters to lead rescue operations, including acquiring the skills to properly assess the situation and hazards and make decisions about the use of resources and forces, including human resources [83].

In the area of a given municipality, the municipal fire protection commander has direct substantive supervision over the improvement process of the TSO units and is optionally appointed by the mayor or the town mayor [84]. Based on expert interviews with municipal fire protection commanders, the scope of training in 2020–2023 in the Cracow Poviat was determined.

The process of improving TSO rescue firefighters can be carried out through practical classes, organized at training grounds, in combustion chambers, or facilities that create conditions similar to real ones—so-called simulators. An aspect for improvement is the drills, exercises, and integration training of the units within the NRFS structures and outside them. Conducting exercises at facilities located within the operation of the units, and taking into account the assumptions the types of hazards that occur in a given area, helps to familiarize individuals with the facilities, the topography of the terrain, and the procedures in force during the operation, as well as improving the practical skills among the individuals and the teams of rescue service units and their cooperation with the structures of local government administration [78].

The Commander of the State Fire Service, regardless of the implemented system, is the competent entity responsible for organizing training and exercises in the relevant area of operation. The Act on Volunteer Fire Brigades adds other entities authorized to organize training and exercises. According to Article 10, paragraph 1, point 1a, “(...) the municipality provides, in accordance with its resources and capabilities, to volunteer fire brigades: (...) financing of training other than those indicated in Article 11 paragraph 1 and training in qualified first aid” [85]. This means that, in addition to the free training provided by the State Fire Service, the municipality may provide volunteer fire brigade units operating in the municipality with additional specialist, advanced, and other training and exercises. From a practical point of view, training and exercises in this case may be developed and carried out by the relevant municipal commander, in cooperation with an employee of the Municipal Office responsible for the implementation of tasks in the field of fire and flood protection in the municipality.

Each organized training program must take into account the safety of the people participating in the exercise. These requirements are set out in the Regulation of the Minister of the Interior and Administration of 31 August 2021, which provides detailed safety and health conditions for the work of State Fire Service firefighters [86]. On the basis of the expert interviews, the scope of the exercises carried out in the Cracow Poviat was determined.

3.2. Research Scales

The expert questions concerned the scope of the exercises and training carried out in the units subordinate to the commanders; the evaluation and recommendation of changes in the basic, specialist, and additional TSO training programs; the evaluation of the degree of preparation of TSOs for their own tasks and tasks in the field of crisis management; and evaluations and recommendations regarding the organization of training and exercises.

The questionnaire’s questions were divided into three thematic groups: those that allowed for an evaluation of the respondents’ experience, those that pertained to the evaluation of training, and those that pertained to the evaluation of exercises.

The questions allowing an assessment of the experience of the respondent TSO firefighters concerned the following: seniority in TSOs; the frequency of participation in rescue actions; the completion of additional or specialized training; and the possession of a license to drive crisis vehicles. It was assumed that simply administering the questionnaire to firefighters who had undergone basic training and were authorized to participate in rescue operations did not guarantee the reliability of their assessments in relation to the training and exercise system.

Therefore, it was checked whether the survey results were significantly influenced by respondents who had less than 5 years of service; had participated in rescue operations less than 10 times; had not completed any additional or specialized training; and did not hold a license to drive crisis vehicles. Chi-squared tests and Cramér’s V ratios were used to assess the statistical significance. The indicators used were designed to test whether experience had a statistically significant effect on the expressed ratings of the firefighters.

Training evaluation questions were explicitly asked, and cross-validation questions were also used. The straightforward questions concerned firefighters’ indications of the need for specific types of training; the effectiveness of the forms of training used; the degree of preparedness of TSOs to carry out their own tasks; and the period of re-training. The clarifying questions concerned assessments of the technical facilities of TSOs. Good equipment ratings were supposed to indicate the preparation of training tools.

Questions about the exercises were asked explicitly and implicitly. The explicit questions concerned the evaluation of the readiness of TSOs for crisis management activities, the forms of crisis management exercises, and the frequency of crisis management exercises. The non-explicit questions concerned knowledge of crisis management procedures in terms of responding during radiation contamination and carrying out general evacuations. The number of correct answers and the juxtaposition of these results with those of the explicit questions were intended to demonstrate the effectiveness of the exercises.

3.3. Research Outcomes

On the basis of the expert interviews with municipal fire chiefs, it was determined that, in the period of 2020–2023, in the Cracow Poviat, the following were trained: 689 persons undertook basic training as a TSO rescue firefighter; 207 persons undertook training as a TSO chief; 152 undertook training as a driver–maintainer of TSO rescue equipment; 351 persons undertook training as the manager of a rescue operation for TSO rescue firefighters; and no training of a municipal fire protection commander was implemented. Additionally, it was established that, in the Cracow Poviat in 2020–2023, a team-building exercise was carried out for all TSO units from the Skawina municipality, under the code name “Kopanka 2021” (27.11.2021) [87]; a team-up exercise was implemented for the Water Supply Platoon of the TSOs of the Cracow Poviat (17.09.2022) [88]; a team-up exercise was implemented under the code name “Masówka 2023” (22.04.2023) [89]; an exercise named “Monastery 2023” (4.11.2023) was implemented [90]; and exercises were conducted for the Central Operational Retreat forming part of the Małopolska Retreat Brigade under the code name “H-USAR 2023” (30.01–01.02.2023 r.) [91].

The chiefs provided recommendations in terms of training programs and the means of organizing exercises, and they assessed the degree of preparedness of TSOs for their own tasks and crisis management tasks.

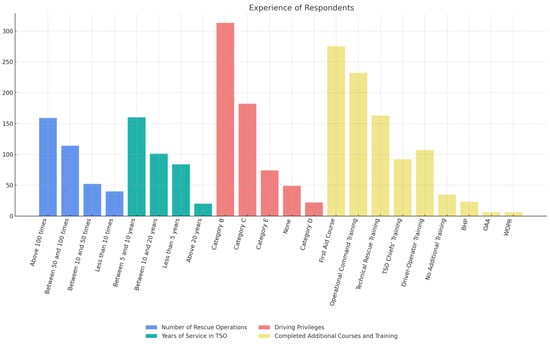

The results of the survey are presented in the figures below. The figures collect responses from the designated research areas. The first thematic area concerned the evaluation of the experience of volunteer firefighters. The results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results of questions that assessed the experience of respondents.

The above figure shows the results of the sub-questions used to assess the experience of a TSO rescue firefighter. In total, 159 firefighters (43.56%) participated in rescue operations > 100 times, 114 (31.23%) participated 50–100 times, 52 (14.25%) participated 10–50 times, and 40 (10.96%) < 10 times. The largest groups of rescue firefighters serving in TSO units were as follows: those with between 5 and 10 years of service amounted to 160 firefighters (43.84%); those with <5 years of service amounted to 84 (23.01%); and 101 (27.67%) had a length of service of 10–20 years or 20 (5.48%) > 20 years. The figure also shows the additional and specialist training (after basic training) and courses completed by the rescue firefighters. The qualified first aid course was completed by 275 firefighters, or 75.34%, and 35 firefighters (9.59%) did not complete any additional training.

Technical rescue training was completed by 163 firefighters (44.66%), chiefs’ training by 92 (25.21%), driver and maintenance training by 107 (29.31%), health and safety training for trainees by 23 (6.46%), air ambulance training by 6 (1.64%), and volunteer water rescue training by 6 (1.64%). Training as a chainsaw operator or to operate hydraulic jacks also appeared in single responses (representing less than 0.3%). These are not included in the figure. The largest group of drivers qualified to drive crisis vehicles consisted of those in category B (cars up to 3.5 t), namely 313 (85.75%). Drivers in category C (cars greater than 3.5 t) accounted for 182 or 49.86% of the respondents. The group of drivers who were licensed to drive category D vehicles (coaches) consisted of 22 firefighters (6.03%). Category E (motorbikes) consisted of 74 (20.27%). It should be noted that one driver may have driving privileges in more than one license category.

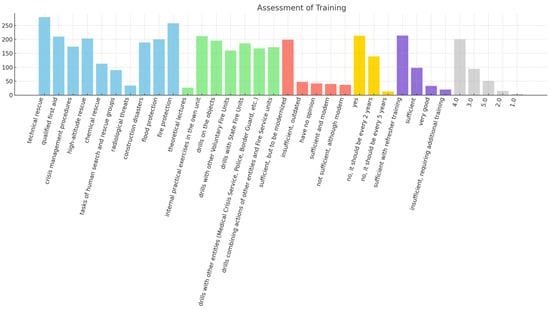

The second area of research was the evaluation of volunteer firefighters’ own task training. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Firefighters’ assessments of training.

Technical rescue (280 people, 76.71%), fire protection (258 people, 70.68%), and qualified first aid (210 people, 57.53%) were considered the most important training courses. More than half of the respondents also indicated height rescue (203 people, 55.62%) and flood protection (200 people, 54.79%). A smaller number of respondents indicated construction disaster management (189, 51.78%) and crisis management procedures (174, 47.67%). Chemical rescue (113, 30.96%), search and rescue group tasks (90, 24.66%), and radiological hazard management were indicated by 34 respondents (9.32%) and were considered the lowest-priority areas. Practical in-house training at the home unit was considered the most effective form of training (212 people, 58.08%). Training in facilities (buildings) (196 persons, 53.7%) and training with units of the State Fire Service (186 persons, 50.96%) were highly rated. Combined training with other entities and units of the State Fire Service (172 persons, 47.12%), as well as training with other entities, such as the ambulance service, the police, and the border guard (168 persons, 46.02%), was also desirable. Theoretical lectures were considered to be the least effective, being indicated by 27 people (7.4%). The evaluation of technical equipment in the volunteer fire brigade showed that most considered their equipment to be sufficient but in need of modernization (199 people, 54.52%). A smaller group considered the equipment insufficient and outdated (47 people, 12.88%), while others considered it sufficient and modern (40 people, 10.96%). Meanwhile, 37 people (10.14%) described their equipment as insufficient but modern, and 42 people (11.51%) did not express an opinion. Regarding the frequency of recertification for QFA courses, the majority of the respondents (213 people, 58.36%) believed that the current three-year period was appropriate. However, a significant proportion of the respondents (139, 38.08%) suggested reducing this period to two years. Thirteen people (3.56%) supported extending the period to five years. The preparation of firefighters was rated mainly as sufficient, with the possibility of introducing refresher training (214 people, 58.63%). A significant number of respondents also rated it as sufficient (98 people, 26.85%), while a smaller group considered it very good (33 people, 9.04%). Only 20 respondents (5.48%) considered the preparation insufficient, requiring additional training and exercises. The quality of the training and courses received the following ratings: it was scored 4.0 (good) by 201 people, or 55.07%; 3.0 (fair) was selected by 94 people (25.75%); and a rating of 5.0 (excellent) was given by 51 people (13.97%). Lower ratings were rare: a score of 2.0 (poor) was given by 15 people (4.11%) and 1.0 (very poor) by only four respondents (1.1%).

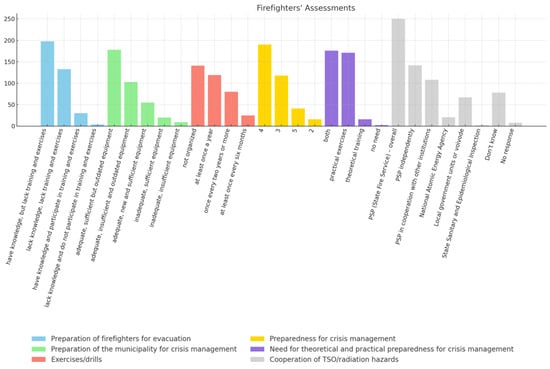

The third area of research was the evaluation of crisis management exercises by volunteer firefighters. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Firefighters’ assessments of exercises.

The above figure shows the firefighters’ evaluations of the crisis management exercises. In total, 198 (54.25% of the respondents) believe that firefighters have the necessary knowledge but lack sufficient drills to carry out second-level evacuations. Meanwhile, 133 respondents (36.44%) indicated a lack of both knowledge and exercises; 30 (8.22%) had the knowledge and had participated in exercises; and four (1.1%) had no knowledge but had participated in drills. When asked about the preparedness of the municipality (crisis management coordination unit for TSOs), 178 (48.77%) indicated that the number of TSO units was adequate and the equipment was adequate but outdated. Meanwhile, 103 (28.22%) stated that the number of TSO units was adequate, but the equipment was outdated and insufficient, and 55 (15.07%) stated that both the number of units and the quantity of equipment were adequate. Twenty (5.48%) stated that the number of TSO units was too high, but the equipment was sufficient. Nine (2.47%) stated that there were too few units and not enough equipment. When asked if there were exercises organized in the municipality where the TSO unit was located, 141 (38.63%) indicated that there were not; 119 (32.6%) stated that they took place once a year; 80 (21.92%) stated once every two years or more; and 25 (6.85%) stated at least once every six months. When asked to assess the readiness of their unit for crisis management tasks, 190 (52.05%) gave a rating of “4” (good); 118 (32.33%) gave “3” (adequate); 41 (11.23%) gave “5” (very good); and 16 (4.38%) gave “2” (poor). When asked to assess their training needs, 176 (48.22%) responded that both theoretical training and practical exercises were necessary; 171 (46.85%) highlighted practical exercises; 16 (4.38%) pointed to the need for theoretical training; and two (0.55%) stated that there was no need for either theoretical training or exercises. Regarding the indication of entities cooperating with the TSO during radiation hazards, 250 (68.49%) indicated the State Fire Service, of which 108 (29.59%) were also in cooperation with other institutions. Meanwhile, 21 (5.75%) indicated the cooperation of CSOs with the National Atomic Energy Agency and 67 (18.36%) with local government units or voivodeships; and 78 (21.37%) replied that they did not know.

4. Discussion

The first part of the questionnaire served to verify the hypothesis that there may be a lack of experience among TSO firefighters in terms of training and exercises that is statistically significant. Based on the results obtained, the question about the possession of a license to drive crisis vehicles could be considered irrelevant in verifying this hypothesis. In this study, the insignificance of the responses regarding the possession of driving privileges was revealed. The comparison of those who had completed maintenance driver training (107 people) with those with category B and C driving privileges indicated that they had obtained their driving privileges outside the TSO training system. This is due to the fact that a volunteer firefighter can provide professional services in various security institutions. Thus, the results regarding the length of service, the number of rescues carried out, and the amount of additional training and exercises undertaken were taken into account. Those who had participated in rescue operations less than 10 times amounted to 40 (10.96%). Service experience of less than 5 years was declared by 84 (23.01%). No additional training was indicated by 35 (9.59%). Meanwhile, 21 (5.75%) people indicated all three responses at the same time. This group’s answers (due to low experience) could have distorted the results of the evaluation and the recommendations. Their answers related to five questions. Statistical verification, however, indicated a lack of significant effects on the survey results (i.e., the chi-squared test and Cramér’s V for these five questions). Thus, this hypothesis was disproven. The results of the verification are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlations between the lack of experience of volunteer firefighters and the evaluation of training and exercises.

Taking into account the coefficients, the minimum sample size, and the chi-squared test and Cramér’s V for the responses of firefighters with low experience, it can be concluded that the results of this research are representative and, at the same time, relevant to the problem of evaluating and recommending changes for the TSO training system.

The second area of research was the analysis of training evaluations from volunteer firefighters. It was confirmed that there was a significant relationship between the evaluation of the quality and usefulness of training and the evaluation of the TSO’s preparedness for its own tasks. To statistically verify this hypothesis, the relationship between the answers to the training questions and those to the question on the TSO’s preparedness for its own tasks was tested. The study showed a lack of a significant relationship only with the answers to the question on the need to obtain recertification for the qualified first aid course. There was a statistically significant relationship between the firefighters’ assessments of their preparedness and their assessments of the technical equipment of the TSO units; their preferences regarding the most effective forms of training; their preferences for mandatory drills; and their assessments of the levels of training and courses conducted. This means that this hypothesis was confirmed. The results of the calculations are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results regarding the relationship between training evaluations and the assessment of a TSO’s preparedness for its own tasks.

In addition, the responses to the question regarding which training and exercises should be compulsory at least once every 2 years may indicate the usefulness of the training, while their juxtaposition with the results regarding the training that firefighters undertake indicates a preference for possible knowledge enhancement. The most useful training was found to be in technical rescue, highlighted by 280 (76.71%); fire protection, highlighted by 258 (70.68%); qualified first aid, highlighted by 210 (57.53%); high-altitude rescue, highlighted by 203 (55.62%); flood protection, highlighted by 200 (54.79%); construction disasters, highlighted by 189 (51.78%); and crisis management procedures, highlighted by 174 (47.67%). High-altitude rescue and technical rescue training were considered the most desirable.

According to the respondents, the form of training that has the greatest impact is practical training. Theoretical forms were considered irrelevant (only 7.4% of the respondents indicated that they were appropriate). Training in the home unit of the TSO, noted by 212 (58.08%), was considered the most desirable, as well as exercises in facilities, noted by 196 (53.7%), and together with units of the State Fire Service, highlighted by 186 (50.96%). Exercises combining the activities of other entities and State Fire Service units, in the form of crisis management exercises, were indicated as less needed. However, there were no significant deviations from the main preferences. The results of the deviation survey are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of the statistical Student’s t-test for questions on forms of training.

The results of the question on the preparedness of TSOs to carry out their own tasks show the possible need for the introduction of so-called refresher training, as noted by 214 respondents (58.63%). This result is in line with the findings regarding the need for recertification in qualified first aid training, mentioned by 213 (58.36%). The quality of training to date was rated as good or “4.0” by 201 (55.07%) or sufficient or “3.0” by 94 (25.75%), indicating room for improvement. Most firefighters rated the technical facilities as sufficient, although 199 stated that they needed to be upgraded (54.52%).

The third part of the survey concerned exercises. It served to verify the hypothesis that there would be a significant relationship between the knowledge of crisis management procedures and the evaluations of exercises and TSOs’ readiness for crisis management tasks. Statistical verification showed a significant relationship between assessments of the range of entities cooperating during radiation contamination, knowledge of evacuation procedures, the municipality’s preparedness for crisis management, and participation in training and the assessment of TSOs’ preparedness to perform crisis management tasks. The verification indicated that there was no significant relationship between the assessment of the TSO’s preparedness for crisis management and the opinion regarding training needs. Thus, this hypothesis was disproven. The results of the verification are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results regarding the relevance of the relationship between exercise evaluations and the assessment of TSO’s preparedness for crisis management.

The results indicate that the members of the TSOs believe that they are familiar with crisis management procedures (radiation, evacuation), which translates into a good assessment of the units’ preparedness in this respect. In addition, the indication of the lack of joint exercises, due to the belief in the knowledge of the procedures, influenced their opinions regarding the evaluation of the preparation of the TSOs for crisis management. At the same time, it should be noted that opinions on the preparation of TSOs were significantly related to the assessment of the municipality’s preparedness for crisis management. Therefore, it can be assumed that, according to the respondents, the readiness of the municipality translates into the operational readiness of the TSO unit.

5. Conclusions

Applied sciences contribute to improving various aspects of the civil protection system and crisis management, as demonstrated through the example of fire protection. Consequently, this can translate into the increased efficiency of emergency services and the strengthening of society’s resilience to emerging threats. From this work, conclusions can be drawn and applied in the basic training program for specialized and additional training and in crisis management exercises.

For the basic training program, firstly, the provision of 65% of the training blocks as practical hours (fire protection training 49 h, including 30 h practical) and technical rescue training (31 h, including 22 practical) should be viewed positively. However, taking into account the firefighters’ responses to the demand for training forms, it should be noted that practical exercises were desired by almost the entire survey sample. In particular, 347 (95.07%) indicated the need for practical training, including 176 respondents (48.22%) requesting this in combination with a theoretical form. Thus, the application of practical techniques should be recommended for both training and exercises. This finding is consistent with the assessments obtained in the expert interviews, in which the commanders mostly pointed to the low didactic effectiveness of remote teaching methods. Secondly, according to the results on the desired training, technical rescue, noted by 280 respondents (76.71%), and fire protection, noted by 258 (70.68%), were mostly desired, which reflects the basic training program. Both subject blocks cover 60.15% of the program. However, it should be noted that, according to the survey results, an increase in flood protection hours should be applied to the program. In total, 200 (54.79%) respondents indicated the usefulness of this training, while the basic program devotes only 4.51% of the program hours to it. Despite the fact that the Cracow Poviat may have greater flood risks than some other poviats in Poland, this disparity should still be considered significant. Thirdly, the change in OSH training should be viewed positively. During the study period, fatal accidents occurred in the municipality of Czernikowo (2021), where two firefighters from the Czernikowo TSO died, and in the village of Małkowo (2023), where another two firefighters from the Żukowo TSO died [92]. Therefore, it should be considered necessary to apply and develop training in OSH. Fourthly, according to the findings of the expert interviews, it is recommended to reduce the number of people to be trained per instructor (practical classes)—the group size should be 8–10 people.

Regarding additional and specialized training, firstly, by juxtaposing the results regarding completed training with those of the evaluation of the usefulness of training, it is possible to identify the training deficiencies of the TSOs. Qualified first aid (210 (57.53%)), high-altitude rescue (203 (55.62%)), construction disasters (189 (51.78%)), and crisis management procedures (174 (47.67%)) were indicated as useful. Qualified first aid courses (275 (75.34%)), operational command training (232 (63.56%)), technical rescue training (163 (44.66%)), TSO chiefs’ training (92 (25.21%)), and driver–operator training (107 (29.31%)) were indicated as the most frequently completed additional training courses (after basic training). Thus, training beyond the content stipulated in additional and specialized training programs should be considered to be the most desirable for application. More than half of all firefighters find high-altitude rescue training useful; therefore, it is recommended that it be introduced and applied within the scope of specialized training, especially since the expert interviews indicated the increasing prevalence of hazards requiring work at height. Secondly, the results of the survey indicate the need for the continuous recertification of existing qualifications. Firefighters are aware that their authorizations could become obsolete regardless of the extent of their practical experience (chi-squared: 11.44, p-value: 0.247 for the question on the length of service). The results of the evaluation of TSOs’ preparation for their own tasks indicate a possible need for the introduction of so-called refresher training, highlighted by 214 respondents (58.63%). This result is in line with the findings on the need for recertification in qualified first aid training (213 (58.36%)), which could indicate the need to prioritize the recertification of existing credentials, rather than a need to expand the qualifications. This should be interpreted as a desire to adapt to dynamic changes in the TSO environment (legal, social, and technical). The expert interviews also indicated the need to adapt training to current hazards, where, according to the respondents, there are fewer fires, while there are more incidents such as “isolated medical incidents, incidents with photovoltaics, electric cars”. Thus, regarding training, priority should be given to systematizing recertification cycles, while, at a later stage, work should be undertaken regarding the introduction of new training programs. Thirdly, there was no consensus in the expert interviews on the issue of responsibility for the organization of training. The majority of the respondents pointed to the need to require training to be organized and applied only by provincial State Fire Service training centers and not by local government units. Placing these findings in a broader context, the Law on Civil Protection and Civil Defense, which came into effect on January 1, 2025, requires municipalities to organize civil defense training for TSOs. The legal act that regulates the content of the training is still in development, but the scope of additional training is expected to expand. In the context of the study’s results, a practical, facility-based form of this type of training should be recommended for application.

As a result of the analysis of the collected material, it is confirmed that training plays an important role for TSO rescue firefighters. This is evidenced by the number of additional and specialized training courses attended by firefighters. For example, 275 completed the QFA course, which is the most common training and is indicated as necessary for the service due to the presence of injured persons during incidents. At the specialized level, the most frequently completed training was that of TSO commanders (232 firefighters). A correlation was noted between the completed training and the indicated need for training and exercises related to expanding basic knowledge. Technical rescue training is the most desirable. This need may be linked to changes in the types of local threats. Expanding the scope of incidents beyond fire protection requires specialized training in technical rescue. Rescue firefighters, moreover, point to drills as the most effective form for improvements in skills, where workshops held at the home unit are still the most important. In this sense, the need for the joint training of emergency services and public authorities in crisis management is indicated as a recommendation, especially considering asymmetric threats [93,94].

Regarding exercises in crisis management, firstly, despite the positive verification of Hypothesis 3, doubts must be noted about the knowledge of crisis management procedures among TSO firefighters. Knowledge of crisis management procedures was checked by asking the question of which institutions the TSO should cooperate with in the event of radiation contamination. The answers indicated a lack of knowledge of these procedures (despite the confidence in their knowledge). According to the procedure, in the event of radiation contamination, the unit supervising all activities is the State Sanitary and Epidemiological Inspectorate, together with the voivode. On the other hand, depending on the type of contamination (accidents in the transport of radioactive material, the detection of contamination in the air, etc.), the TSO engages in cooperation with specialist units of the State Fire Service, the local government, the Emergency Medical Service, or the National Atomic Energy Agency [95]. Only one answer among 365 responses (0.274%) indicated the full correct scope of cooperation. Meanwhile, 142 (39.88%) responses, provided by the largest percentage of respondents, indicated only cooperation with the State Fire Service; 115 (31.51%) responses indicated the State Fire Service and another entity or entities (including one response highlighting the State Sanitary and Epidemiological Inspectorate, 67 highlighting the local government or voivode, and 18 highlighting the National Atomic Energy Agency). The institutions mentioned most frequently as cooperating with the State Fire Service or independently cooperating with the volunteer fire service were the police, at 75 (22.39%); the army, at 33 (9.04%); or the territorial defense forces. Meanwhile, 78 (21.37%) respondents indicated the answer “I don’t know”. The responses to the question about knowledge of evacuation procedures also indicate deficiencies in the scope of exercises. Specifically, 331 (90.68%) indicated that there was a lack of exercises in this area, and 198 (54.25%) declared that they knew about this type of procedure. There were no statistically significant differences in the general responses of those who reported the correct answer and the other respondents (p-value: 0.201 [not significant]). Moreover, the responses of firefighters with low experience showed no statistically significant deviations (Tebele 7). Therefore it should be concluded that the confidence of firefighters about their crisis management knowledge is independent of their experience. The reason for such poor knowledge of emergency management procedures may be that the volunteer fire department is a supporting, but not a leading, entity in them. Nevertheless, the lack of knowledge of such procedures, as well as the statement about the lack of field exercises, indicates the need to apply greater effort in training for crisis management. Secondly, this conclusion was confirmed by the answers to the question about whether exercises were organized in the municipality where the respondent’s TSO operated. The results indicated that 119 (32.6%) respondents had undertaken training in the last year. However, training should be considered as a rare practice, because the generalized results indicated that 221 (60.55%) had not undertaken any within the past two years or not at all. When comparing this result with the findings of the expert interviews, it is recommended to carry out crisis management exercises at least once a year. This conclusion is strengthened by the fact that, in accordance with the verification of H3, volunteer firefighters are confident in their own knowledge of crisis management procedures, which is line with the results of the assessment of the volunteer fire department’s preparation in this area (a need for theoretical and practical preparedness for crisis management, 12.18; p-value: 0.2 [not significant]). According to the findings, based on the indirect questions, this may be an unjustified conclusion, resulting in an erroneous assessment of the TSO’s preparation for crisis situations. Thirdly, convergence was observed between the assessments of the preparation of the municipality for crisis management and the assessment of the volunteer fire department’s preparation for the implementation of tasks in this area. The question about the municipality’s preparation resulted from the fact that the tasks in the scope of crisis management carried out by the volunteer fire department are always carried out in cooperation with the municipality as a leading or supporting entity. The assessment of the preparation of the municipality indicated the adequate preparation of the units and sufficient but outdated equipment, as highlighted by 178 (48.77%). Moreover, 55 (15.07%) considered the equipment adequate or new, and 233 (63.83%) positively evaluated the preparation of the municipality for crisis management. This result is in line with the responses to the question about the preparation of the volunteer fire department’s own unit for crisis management. This was assessed as good, or “4”, or very good, or “5”, by 231 people (63.29%), which, in combination with the statistical verification, indicates that the volunteer fire department’s preparation for crisis management is linked to the municipality’s preparations in this area. This conclusion is related to the fact that, in the municipalities, the technical facilities are transferred to the use of the volunteer fire department. Additionally, the municipality prepares and organizes exercises within the scope of crisis management. In such a case, improving the effectiveness of the local government’s preparation in organizing crisis management exercises should also be considered a key element in preparing the volunteer fire department.

In the expert interviews, a recommendation was obtained in regard to both training and exercises. It was indicated that it is necessary to perform inspections of the combat readiness of the volunteer fire department by the State Fire Service or the Municipal Fire Protection Commander. However, attention was drawn to the lack of an appropriate legislative solution at the level of regulations or guidelines for the Chief Commander of the State Fire Service in this regard. Therefore, it is recommended to fill this legal gap, apply the mandatory frequency of inspections, and define their form.

Finally, limitations should be noted. Firstly, this article is based on publications indexed in the Scopus and Web of Science databases. However, there may have been publications that were not included in these databases. Nonetheless, considering the relevance of these databases, it should be assumed that all relevant papers were used in this study. Secondly, only publications in English were included in the analysis. This approach also seems to be an appropriate step, since contemporary scientific discourse takes place in this language. In any case, future research could focus on analyzing publications in other languages. Thirdly, the survey was based on random selection. The survey results indicated that 217 (59.45%) respondents were firefighters from units not included in the NRFS, while 148 (49.55%) were volunteer firefighters from units included in the NRFS. Taking into account the proportion of volunteer fire department units in the Cracow Poviat included in the NRFS from which the respondents came (45 out of 171, 26.32%), doubts could be expressed as to the representativeness of the research in this context. However, when checking the differences in the responses of volunteer firefighters from units in the NRFS with the responses of firefighters from units not included in the NRFS, no significant impact on the results of the remaining survey questions was observed (chi-squared: 4.02, p-value: 0.403, Cramér’s V: 0.105). Fourthly, this research was conducted in a representative manner for the Cracow Poviat. More research is required to verify whether there are significant deviations from the results at a national scale. Fifth, the conclusions and recommendations refer to changes in the Polish system of training and exercises for volunteer fire departments. The applicability of the conclusions to the training systems of other countries requires additional comparison. Sixth, this study examined volunteer firefighters’ self-assessments of the exercises and training that they received. This was considered valuable, since the results of the study indicated the expectations and needs of the target group; in addition, the results were based on the opinions of people with experience. However, an evaluation of the effectiveness of training requires further research, especially considering the use of objective tests of competence in real or simulated conditions. Finally, another methodological limitation is the need for further research into the phenomenon of volunteer firefighters overestimating their crisis management skills. The study of the Dunning–Kruger effect among firefighters should be considered as a further research direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H., G.W.-J. and J.W.-J.; methodology, R.H., G.W.-J. and J.W.-J.; software, R.H.; validation, R.H. and A.K.; formal analysis, J.W.-J. and R.H.; investigation, R.H., A.S. and W.Ś.; resources, R.H. and A.S.; data curation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H., G.W.-J. and J.W.-J.; final writing—review and editing, R.H., G.W.-J., A.K., W.Ś. and J.W.-J.; visualization, A.K., A.S. and W.Ś.; supervision, R.H., G.W.-J. and J.W.-J.; project administration, R.H., G.W.-J. and J.W.-J.; funding acquisition, J.W.-J. and G.W.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TSO | Volunteer Fire Brigade |

| NRFS | National Rescue and Firefighting System |

| OAA | Training in Operating an Air Ambulance |

| QFA | Qualified First Aid |

| HRO | Head Rescue Operations Officer |

References

- Koklu, M.; Taspinar, Y.S. Determining the extinguishing status of fuel flames with sound wave by machine learning methods. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Stankov, S.; Wilk-Jakubowski, J.; Stawczyk, P. The using of Deep Neural Networks and acoustic waves modulated by triangular waveform for extinguishing fires. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on New Approaches for Multidimensional Signal Processing ’20, Sofia, Bulgaria, 9–11 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celen, V.B.; Demirci, M.F. Fire detection in different color models. In Proceedings of the 2012 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WorldComp), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 16–19 July 2012; pp. 1–7. Available online: http://worldcomp-proceedings.com/proc/p2012/IPC8008.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Wilk-Jakubowski, J.L.; Loboichenko, V.; Divizinyuk, M.; Wilk-Jakubowski, G.; Shevchenko, R.; Ivanov, S.; Strelets, V. Acoustic Waves and Their Application in Modern Fire Detection Using Artificial Vision Systems: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D.; O’Reilly, R. An Evaluation of Convolutional Neural Network Models for Object Detection in Images on Low-End Devices. In Proceedings of the 26th AIAI Irish Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science, Dublin, Ireland, 6–7 December 2018; Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2259/aics_32.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Wilk-Jakubowski, J.; Stawczyk, P.; Ivanov, S.; Stankov, S. High-power acoustic fire extinguisher with artificial intelligence platform. Int. J. Comput. Vis. Robot. 2022, 12, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, R.G.; Baylon, Z.A.P.; Garcia, C.A.D.; Huevos, J.R.G.; Ilagan, J.L.S.; Rocha, M.J.T. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches for Sound Wave Flame Extinction System Towards Environmental Friendly Fire Suppression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON 2023), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 October–3 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Stankov, S. Acoustic Extinguishing of Flames Detected by Deep Neural Networks in Embedded Systems. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, XLVI-4/W5-2021, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Jakubowski, J.; Stawczyk, P.; Ivanov, S.; Stankov, S. Control of acoustic extinguisher with Deep Neural Networks for fire detection. Elektron. Elektrotechnika 2022, 28, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavassori, A.; Carrion, D.; Zaragozi, B.; Migliaccio, F. VGI and Satellite Imagery Integration for Crisis Mapping of Flood Events. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Jakubowski, J.; Stawczyk, P.; Ivanov, S.; Stankov, S. The using of Deep Neural Networks and natural mechanisms of acoustic waves propagation for extinguishing flames. Int. J. Comput. Vis. Robot. 2022, 12, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.; Nowell, B. Networks and Crisis Management. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1650 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Wilk-Jakubowski, G. Normative Dimension of Crisis Management System in the Third Republic of Poland in an International Context. Organizational and Economic Aspects; Wydawnictwo Społecznej Akademii Nauk: Łódź-Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk-Jakubowski, G.; Harabin, R.; Skoczek, T.; Wilk-Jakubowski, J. Preparation of the Police in the Field of Counter-terrorism in Opinions of the Independent Counter-terrorist Sub-division of the Regional Police Headquarters in Cracow. Slovak J. Political Sci. 2022, 22, 174–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z Dnia 5 Grudnia 2024 r. o Ochronie Ludności i Obronie Cywilnej. Available online: https://orka.sejm.gov.pl/proc10.nsf/ustawy/664_u.htm (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Wyrok Trybunału Konstytucyjnego z Dnia 3 Lipca 2012 r. Sygn. Akt K 22/09. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20120000799 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Ustawa z Dnia 26 Kwietnia 2007 r. o Zarządzaniu Kryzysowym, Dz.U. z 2017 r. Poz. 209, 1566. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20070890590 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Harabin, R. Functional-Pragmatic Theory of Crisis Management: Organizational and Financial Aspects: Polish Casus in Territorial Implementation; Społeczna Akademia Nauk: Łódź -Warszawa, Poland, 2021; pp. 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ochotnicze Straże Pożarne—Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji—Portal Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/mswia/ochotnicze-straze-pozarne (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Komendant Główny PSP z Dniem 11 listopada 2024 r. Włączył do Krajowego Systemu Ratowniczo-Gaśniczego 236 Jednostek Ochrony Przeciwpożarowej—Komenda Główna Państwowej Straży Pożarnej—Portal Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kgpsp/komendant-glowny-psp-z-dniem-11-listopada-2024-r-wlaczyl-do-krajowego-systemu-ratowniczo-gasniczego-236-jednostki-osp (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Wilk-Jakubowski, G.; Harabin, R.; Ivanov, S. Robotics in Crisis Management: A Review. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Petersen, A.; Abbiss, C.R.; Netto, K.; Payne, W.; Nichols, D.; Aisbett, B. Pack Hike Test Finishing Time for Australian Firefighters: Pass Rates and Correlates of Performance. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Jahnke, S.; Haddock, C.; Kaipust, C.; Jitnarin, N.; Poston, W. Occupationally Tailored, Web-Based, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program for Firefighters: Cluster Randomized Trial and Weight Outcome. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzale, L. Motivational Implications Leading to the Continued Commitment of Volunteer Firefighters. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2019, 8, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, D.; Moore, D.; Stewart, I. Age and Physical Activity Status of Australian Volunteer Firefighters: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 33, WF23146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannigan, F.L. Hazard Clues: Old but Valid. Fire Eng. 2005, 158, 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, F.; George; Diene, L.; Kinnel, M.; Levy, J.; Jacquemin, L. Case 2. In Clinical Cases in Cardiac Electrophysiology: Ventricular Arrhythmias; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.; Snow, R.; Williams-Bell, M.; Aisbett, B. Simulated Firefighting Task Performance and Physiology Under Very Hot Conditions. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, A.; Varnai, V.M.; Petrinec, B.; Macan, J. Response to Thermal and Physical Strain during Flashover Training in Croatian Firefighters. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Poh, P.Y.S.; Greenlee, T.A.; Goldstein, E.; Horn, G.P.; Smith, D.L. Physiological, Perceptual and Psychological Responses of Career versus Volunteer Firefighters to Live-Fire Training Drills. Stress Health 2016, 32, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savall, A.; Charles, R.; Binazet, J.; Frey, F.; Trombert, B.; Fontana, L.; Barthélémy, J.-C.; Pelissier, C. Volunteer and Career French Firefighters With High Cardiovascular Risk: Epidemiology and Exercise Tests. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, S.; Horie, S.; Kawanami, S.; Inoue, D.; Morizane, S.; Inoue, J.; Nagano, C.; Sakurai, M.; Serizawa, R.; Hamada, K. Efficacy of Ice Slurry and Carbohydrate–Electrolyte Solutions for Firefighters. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, 12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, K.; Nickelson, J. Predicting Intention to Be Physically Active among Volunteer Firefighters. Am. J. Health Educ. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, A. Exploring Critical Incidents and Postexposure Management in a Volunteer Fire Service. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2017, 26, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farioli, A.; Yang, J.; Teehan, D.; Baur, D.; Smith, D.; Kales, S. Duty-Related Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death among Young US Firefighters. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, M.; Walter, A. Motivations and Expectations of German Volunteer Firefighters. J. Civ. Soc. 2024, 20, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gähwiler, R.; Templin, C.; Lüscher, T.F.; Ghadri, J.-R. A Heart Without Overspeed Trip Unit. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/en/tech-docs/paper/439795 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hwang, J.; Taylor, R.; Macy, G.; Cann, C.M.; Golla, V. Comparison of Use, Storage, and Cleaning Practices for Personal Protective Equipment Between Career and Volunteer Firefighters in Northwestern Kenkucky in the United States. J. Environ. Health 2019, 82, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, M.G. Pesticide Chemical Runaway Reaction Pressure Vessel Explosion: (Two Killed, Eight Injured). In Proceedings of the 3rd CCPS Latin American Process Safety Conference and Expo 2011, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 8–10 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saoji, S.; Tam, W.C.; Brunner, W.; Carey, M. The Effect of Mandatory Fitness Requirements on Cardiovascular Events: A State-by-State Analysis Using a National Database. Workplace Health Saf. 2024, 72, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Palmieri, T.; Greenhalgh, D. Cardiac Fatalities in Firefighters: An Analysis of the U.S. Fire Administration Database. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefko, M. Reflections on (Non)Functioning Compensation for Volunteer Firefighters. Pravnik 2022, 161, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, G.; Ridgers, N.; Ferguson, S.; Aisbett, B. Associations between Firefighters’ Physical Activity across Multiple Shifts of Wildfire Suppression. Ergonomics 2015, 59, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, Z.; Horton, D.K.; Kaye, W.E. Hazardous substances releases causing fatalities and/or people transported to hospitals: Rural/Agricultural vs. Other Areas. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2004, 19, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowlishaw, S.; Birch, A.; McLennan, J.; Hayes, P. Antecedents and Outcomes of Volunteer Work–Family Conflict and Facilitation in Australia. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.C.; Sowa, J.E. Retaining Critical Human Capital: Volunteer Firefighters in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Voluntas 2018, 29, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruskova, M.; Kavan, Š.; Mráčková, P.; Bublíková, V. Physical, motoric and cardiovascular status in selected groups of firefighters in Czech republic—Case study. Mil. Med. Sci. Lett. 2021, 90, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.K.; Jensen, J.; Youngs, G. Volunteer Fire Chiefs’ Perceptions of Retention and Recruitment Challenges in Rural Fire Departments: The Case of North Dakota, USA. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2014, 11, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr-Pries, N.J.; Killip, S.C.; MacDermid, J.C. Scoping Review of the Occurrence and Characteristics of Firefighter Exercise and Training Injuries. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIOSH. Line-of-Duty Death Report: Volunteer Firefighter/Rescue Diver Dies in a Training Incident at a Pennsylvania Quarry. Fire Rescue Mag. 2007, 25, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Volunteer Advice. Fire Prev. Fire Eng. J. 2003, 63, 54–55.

- Volunteer Information. Fire Prev. Fire Eng. J. 2007.

- Pillsworth, T. Paid Two-Week Training Spurs Retention and Recruitment. Fire Eng. 2007, 160, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rascon, N. A Communication Complex Approach to Autism Awareness Training Within First Response Systems in Indiana. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 610012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.C.; Poi, W.R.; Panzarini, S.R.; Sonoda, C.K.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Manfrin, T.M. Knowledge of Firefighters with Special Paramedic Training of the Emergency Management of Avulsed Teeth. Dent. Traumatol. 2009, 25, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, G.B.; Hwang, J.; Taylor, R.; Golla, V.; Cann, C.; Gates, B. Examining Behaviors Related to Retirement, Cleaning, and Storage of Turnout Gear Among Rural Firefighters. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.S.; Yoos, J.L. Health Promotion in Volunteer Firefighters: Assessing Knowledge of Risk for Developing Cardiovascular Disease. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexis, T.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. Interactive Mobile Application, Web Technologies and Fire Simulations in the Service of Forest Fire Volunteers. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Telecommunications and Multimedia (TEMU), Heraklion, Greece, 28–30 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wener, R.; Panindre, P.; Kumar, S.; Feygina, I.; Smith, E.; Dalton, J.; Seal, U. Assessment of Web-Based Interactive Game System Methodology for Dissemination and Diffusion to Improve Firefighter Safety and Wellness. Fire Saf. J. 2015, 72, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derella, C.; Aichele, K.; Oakman, J.; Cromwell, C.; Hill, J.; Chavis, L.; Perez, A.; Getty, A.; Tia, R.; Feairheller, D. Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Responses to Gear Weight Under a Controlled Workload. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feairheller, D. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Responses in Volunteer Firefighters While Wearing Personal Protective Equipment. Blood Press. Monit. 2015, 20, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getty, A.K.; Wisdo, T.R.; Chavis, L.N.; Derella, C.C.; McLaughlin, K.C.; Perez, A.N.; DiCiurcio, W.T.; Corbin, M.; Feairheller, D.L. Effects of Circuit Exercise Training on Vascular Health and Blood Pressure. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, R.L.; Heath, E.M. Comparison of Aerobic Capacity in Annually Certified and Uncertified Volunteer Firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latosinski, F.; Cuesta, A.; Alvear, D.; Fernández, D. Determinants of Stair Climbing Speeds in Volunteer Firefighters. Saf. Sci. 2024, 171, 106398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel-Millet, P.; Cassirame, J.; Eon, P.; Williams-Bell, F.M.; Gimenez, P.; Grosprêtre, S. Physiological Demands and Physical Performance Determinants of a New Firefighting Simulation Test. Ergonomics 2023, 66, 2012–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-W.; Bang, C.-H.; Lee, G.; Lee, J.-K.; Kwan, J.-S.; Huh, Y.-S. Changes of Oxidative/Antioxidative Parameters and DNA Damage in Firefighters Wearing Personal Protective Equipment during Treadmill Walking Training. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 3173–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, M.; Cadoni, G.; Leban, B.; Loi, A. A Comparative Study of Static Balance before and after a Simulated Firefighting Drill in Career and Volunteer Italian Firefighters. In Advances in Physical Ergonomics and Safety; Routledge & CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schlader, Z.J.; Colburn, D.; Hostler, D. Heat Strain Is Exacerbated on the Second of Consecutive Days of Fire Suppression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Bell, F.M.; Aisbett, B.; Murphy, B.A.; Larsen, B. The Effects of Simulated Wildland Firefighting Tasks on Core Temperature and Cognitive Function under Very Hot Conditions. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Sowa, J. Creating Cohesive Volunteer Groups: The Role of Group Identification in Volunteer Fire Services. Public Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.F.; Smith, D.L.; Petruzzello; Bone, B.G. Heat Stress in the Training Environment. Fire Eng. 1998, 151, 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Paletta, L.; Schneeberger, M.; Reim, L.; Kallus, W.; Peer, A.; Schönauer, C.; Pszeida, M.; Dini, A.; Ladstätter, S.; Weber, A. Work-in-Progress—Digital Human Factors Measurements in First Responder Virtual Reality-Based Skill Training. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network, Vienna, Austria, 30 May–4 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkhyour, M.A. Evaluation of Full-Facepiece Respirator Fit on Fire Fighters in the Municipality of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvirn, M.A.; Dorrian, J.; Smith, B.P.; Jay, S.M.; Vincent, G.E.; Ferguson, S.A. The Sleep Architecture of Australian Volunteer Firefighters during a Multi-Day Simulated Wildfire Suppression: Impact of Sleep Restriction and Temperature. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 99, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheaff, A.K.; Bennett, A.; Hanson, E.D.; Kim, Y.-S.; Hsu, J.; Shim, J.K.; Edwards, S.T.; Hurley, B.F. Physiological Determinants of the Candidate Physical Ability Test in Firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 3112–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.A.; Landreville, P.G. Volunteer Firefighter as Initial Incident Commander. Fire Eng. 2007, 160, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Odpowiedź Na Pismo z Dnia 14 Marca 2024 r. KM PSP w Cracowie, Sygn. Akt MR.077.69.2024 2024.

- Zasady Przygotowania Strażaków Ratowników Ochotniczych Straży Pożarnych do Udziału w Działaniach Ratowniczych—Komenda Główna Państwowej Straży Pożarnej—Portal Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kgpsp/zasady-przygotowania-strazakow-ratownikow-ochotniczych-strazy-pozarnych-do-udzialu-w-dzialaniach-ratowniczych (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Programy Szkolenia OSP—2015. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kmpsp-bialystok/programy-szkolen-osp (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Programy Szkolenia OSP—2022. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kmpsp-bialystok/programy-szkolenia-osp---2022-obowiazujace-od-lutego-2022-r (accessed on 18 January 2025).