Abstract

Canal wall down mastoidectomy (CWD) effectively eradicates cholesteatoma and chronic otitis media but frequently results in a problematic open mastoid cavity. Mastoid obliteration aims to reduce cavity-related morbidity. Bioceramic materials, including hydroxyapatite (HA), tricalcium phosphate (TCP), and bioactive glass (BAG), have been increasingly adopted because of their osteoconductive, biocompatible, and antimicrobial properties. This systematic review evaluates the clinical outcomes and complications of bioceramic mastoid obliteration following CWD. A systematic literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science was conducted for studies published between 2005 and 2025, following PRISMA guidelines. Clinical studies reporting outcomes of bioceramic mastoid obliteration after CWD were included. Thirteen clinical studies were included. HA-, TCP-, and BAG-based materials demonstrated high obliteration success rates (>90% in most series). BAG S53P4 was consistently associated with low infection rates and favorable epithelialization, whereas earlier HA cement formulations were occasionally associated with revision-requiring complications. Bioceramic scaffolds represent safe and effective materials for mastoid obliteration after CWD. BAG offers additional antibacterial advantages, while HA provides predictable volume stability. Further prospective and comparative studies are required to establish material superiority and long-term outcomes.

1. Introduction

Cholesteatoma is a destructive epithelial lesion characterized by keratinizing squamous epithelium within the middle ear and mastoid, capable of progressive bone erosion and severe complications, including hearing loss, vestibular dysfunction, facial nerve paralysis, and intracranial involvement [1,2]. The canal wall down mastoidectomy is commonly used for the eradication of chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma. Unfortunately, even with careful surgical technique, over 10% of patients experience the complication of developing a troublesome mastoid cavity [1,2]. Mastoid obliteration aims to replace the open mastoid cavity with viable material that is devoid of cholesteatoma and infection. The resulting epithelized lateral surface ablates the mucosalized and pneumatized mastoid space while isolating the mucosalized mesotympanic space [3]. The primary goals of obliteration include reducing chronic drainage, preventing cavity-related complications, improving cosmesis, and enabling safer imaging modalities postoperatively. The choice of obliteration material is crucial, as it must support tissue integration, resist infection, and maintain structural volume over time. Traditional obliteration materials include autologous fat, bone pâté, or cartilage [2,3]. Although autologous materials are the greatest choice for reconstructing the posterior ear canal and mastoid obliteration, they have drawbacks such as donor site morbidity, atrophy, resorption, and difficulty in fashioning. Finding enough material is frequently difficult due to the volume of prior operations [4]. Other methods include “allografting,” which uses bone tissue from another individual, and “xenografting,” which uses bone grafts made from animal tissues. However, complications, including tissue incompatibility, increased immunological reactions, and the possibility of disease transfer, could result from these techniques. Allografts also lead to a delayed osseointegration process.

Due to the swift advancements in biomaterials over the past few years, mastoid obliteration can effectively solve these issues. Both biological and synthetic materials may be utilized for the process of mastoid obliteration.

Bioceramic materials—engineered ceramics designed for use in biological environments—have emerged as an ideal class of scaffolds for otologic reconstruction [2]. These materials, including hydroxyapatite (HA), tricalcium phosphate (TCP), and bioactive glass, mimic the mineral phase of bone and are inherently osteoconductive. They have emerged as promising alternatives in mastoid obliteration due to their osteoconductivity, biocompatibility, and long-term stability. Their success in craniofacial and orthopedic applications has led to increased interest in otologic use [5,6]. HA resembles natural bone mineral in structure and composition, allowing for osteoconduction and long-term volumetric stability. One kind of glass–ceramic biomaterial that adheres to bone and promotes tissue regeneration is called bioactive glass. It develops a coating on its surface that resembles hydroxyapatite after implantation, enabling it to fuse with bone cells and eventually be replaced by new bone. It is helpful in dental and orthopedic applications, including bone healing, enamel rebuilding, and implant coatings, because of its biocompatibility and osteogenic potential.

The S53P4 bioactive glass (BAG) variant, in particular, has demonstrated superior antibacterial properties, making it highly suitable for infected mastoid cavities or revision surgery. Clinical studies report decreased bacterial biofilm formation and reduced need for long-term antibiotics when using BAG [7].

This systematic review synthesizes contemporary clinical evidence on the outcomes and complications of bioceramic mastoid obliteration following CWD, with emphasis on material-specific performance and emerging tissue engineering strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guideline.

2.2. Search Strategy

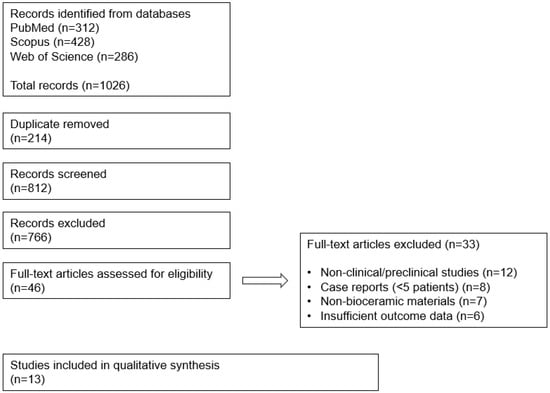

A comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science was performed for articles published between January 2005 and June 2025 (Figure 1). Search terms included “mastoid obliteration,” “bioceramic,” “hydroxyapatite,” “bioactive glass,” “tricalcium phosphate,” and “temporal bone.” Reference lists of included studies were manually screened.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were clinical studies or case series involving at least five patients, use of bioceramic materials for mastoid or epitympanic obliteration following CWD, a minimum follow-up of six months, and reporting of clinical outcomes or complications.

Exclusion criteria included case reports with fewer than five patients, purely preclinical studies, non-English articles, conference abstracts without full text, and studies lacking outcome data specific to bioceramic obliteration.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Extracted data included material type, surgical technique, number of ears, follow-up duration, clinical outcomes, complications, and radiologic findings.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers using the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies. The following domains were evaluated: bias due to confounding, selection of participants, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selective reporting. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Outcomes

The reviewed studies consistently reported favorable outcomes with the use of bioceramic scaffolds in mastoid obliteration (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Across the 13 studies analyzed, obliteration success rates exceeded 90% in most series [8,9,10,11]. Integration of the scaffold into native bone was confirmed through postoperative imaging, such as CT or MRI, in the majority of patients. In particular, hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds exhibited minimal resorption and maintained volume long-term [12,13].

The difference between biological HA and synthetic HA was studied. Whereas synthetic HA is produced chemically, biologic HA is HA that is found in natural sources such as bones. Although they have the same chemical formula (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), synthetic and biological HA are different in terms of composition, structure, and characteristics [14]. Synthetic HA is more homogeneous and pure, while biologic HA has inherent inadequacies and substitutions that affect its bioactivity and rate of degradation. While naturally produced HA can provide improved mechanical performance and particular biofunctions from trace elements, synthetic HA is frequently employed in dental and orthopedic implants because of its biocompatibility and capacity to promote bone formation [14]. In Jang et al.’s preclinical study, after 12 weeks of mastoid obliteration using Sprague–Dawley, neither biological HA nor artificial synthetic HA showed any indications of resorption. Micro-CT and confocal microscopy results, however, showed that the biological HA group’s rapid osteoconductive bone growth was superior to that of the artificial synthetic HA group [15]. After mastoid obliteration using allograft bone and BAG, the postoperative assessment revealed that bone allografts was disappointing in early follow-up, with significant resorption leading to a 40.0% revision surgery rate [16]. Both kinds of HA are widely utilized in dentistry and medicine for orthopedic purposes, dental implants, and bone regeneration. The particular application and required qualities frequently determine which of the biological and synthetic HA is best [17].

Recently, Linderboom et al. performed mastoid obliteration with HA vs. bone pâté in CWD with cholesteatoma and chronic suppurative otitis media [11]. According to an evaluation of mastoid obliteration, bone pâté and HA are safe and efficient obliteration materials that respect the short-term limitation and have high success rates in producing a dry ear, low recidivism rates, and good hearing outcomes. Furthermore, our research indicates that, in contrast to bone pâté, hydroxyapatite causes fewer postoperative wound infections.

BGA is distinguished by its capacity to adhere to teeth and bone. Although the parent bioactive glasses are amorphous, heat treatment is a particular procedure that causes partial crystallization, producing a glass–ceramic material that combines the bioactivity of the glass with the improved mechanical qualities (such as high strength and fracture toughness) of the crystalline phases. It is a composite material that contains two distinct crystalline phases, apatite and beta-wollastonite, as well as a residual amorphous glassy phase [18]. Even when the body was subjected to load-bearing circumstances, it demonstrated bioactivity and a rather high mechanical strength that only gradually declined [19]. The bioactive glasses have the ability to promote the creation of new bone tissue, adhere to the surrounding soft and hard tissues, change into a substance resembling hydroxyapatite both in vitro and in vivo, and release ions that stimulate the expression of osteogenic genes [20]. Although they both aid in bone regeneration, HA and BAG work in different ways. Superior osteoinductive and osteoconductive effects can result from BAG’s faster resorption and ion release, as well as its capacity to customize its composition and properties [21,22]. This makes it a more adaptable and perhaps more useful material for bone regeneration in specific applications. Compared to mastoidectomy alone, obliteration of the mastoid cavity utilizing BAG S53P4 considerably improves the accomplishment of a dry and safe ear in patients with continuously discharging noncholesteatomatous chronic otitis media. Crucially, S53P4 BAG obliteration did not result in any negative outcomes [23].

Several studies evaluated postoperative hearing outcomes [11,24]. Although mastoid obliteration is not primarily aimed at hearing restoration, patients undergoing concurrent tympanoplasty procedures often showed stable or improved air–bone gaps postoperatively. The obliteration also minimized debris accumulation and reduced the frequency of cavity cleaning in canal wall down mastoidectomy cases. Vivicorsi et al. [25] compared the HA between BAG. When evaluating the mid-term viability and stability of biomaterial grafts, postoperative CT scans of mastoid obliteration appear to be a valid method. BHA appears to offer more optimal osseointegration than BAG, with no discernible differences in graft resorption and clinical tolerance.

3.2. Complications

Reported complication rates were low. No scaffold-related infections or long-term foreign-body reactions were reported. Bioactive glass scaffolds demonstrated added benefit by reducing postoperative infection rates, possibly due to their intrinsic antibacterial ion release [26,27].

Recently, Choong et al. reported a systematic review of the complications of mastoid obliteration materials [10]. A total of 2578 ears were taken into consideration. The autologous group experienced 142 (6.8%) serious problems and 165 (7.9%) mild issues overall. The overall rate of complications is 14.8%. Recurrent and lingering disease necessitating revision surgery were the main consequences. The allogenic group experienced three (5.6%) serious problems and ten (18.5%) mild issues. The cumulative complication rate was 24%.

Table 1.

Summary of included clinical studies on mastoid obliteration using bioceramic scaffolds (2005–2025).

Table 1.

Summary of included clinical studies on mastoid obliteration using bioceramic scaffolds (2005–2025).

| Author | Ears | Material and FU Duration | Results and Complications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hashimi S et al. [28] | 26 | HA cement, 1 yr | 1 case explantation. EAC granulation, wound dehiscence. | J Laryngol Otol. 2025;139(6):458–463 |

| Liu M et al. [29] | 56 | HA | achieved complete epithelialization within 60 days post-operation was significantly higher in the CGF/HA group than in the HA group. | Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2025;91(3):101561 |

| Chomarat J et al. [30] | 236 | 108 control, 66 Bone pâté, 62 BAG | Highlights the benefits of bone pâté obliteration versus BAG. | Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2025;282(11):5635–5643 |

| Kroon VJ et al. [31] | 208 | 124 BAG. 84 non-ob 1 year | Continuous discharge: 1, revision: 10 in the non-obliteration group. | Otol Neurotol 2025;46(8):949–955 |

| Zwiez A et al. [32] | 28 | 21 sticky bone, 7 BAG 9 months | No difference between the 2 groups. | J Clin Med 2025;14(5):1681 |

| Kroon VJ et al. [33] | 97 | 97 BAG 3.9 years | Only 1 retroauricular skin defect. Ossiculoplasty: 42, 11.2 dB improvement. | OTO Open 2023;7(4):e96. |

| G Leonard C et al. [34] | 90 | BAG 6.59 months | Recurred cholesteatoma: 2, delayed healing: 12. In all cases, conservative management resulted in complete healing. | J Int Adv Otol 2021;17(3):234–238. |

| Sorour SS et al. [35] | 20 | BAG 1–3 years | No granulation, foreign-body reaction, or extrusion; no displacement of BAG material No recurrent facial palsy or cholesteatoma Significant hearing improvement. | Am J Otolaryngol 2018;39(3):282–285. |

| Sahli-Vivicorsi S et al. [16] | 21 | Biological HA vs. BAG 10.4 months | Biological HA seems to provide a more optimal osseointegration versus BG, with no significant differences in graft resorption and clinical tolerance. | Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2022;279(9):4379–4388 |

| Yung M et al. [36] | 140 revision | HA | Revision mastoidectomy using HA was highly successful in converting troublesome mastoid cavities into dry, water-resistant ears. The cumulative complication rate was 16.6%. | J Laryngol Otol 2011;125(3):221–226 |

| Minoda R et al. [37] | 12 | Beta-TCP | 53.8 months TBCT, no continuous discharge, | Otol Neurotol 2007;28(8):1018–1021 |

| Yanagihara N et al. [38] | 42 | Bone pâté combined with HA for 1 year CWUMT with mastoid obliteration Second-stage ossiculoplasty 1 year after the first-stage operation | No postoperative complications nor residual cholesteatoma were encountered. | Otol Neurotol 2009;30(6):766–770 |

| Vos J et al. [23] | 23 | BAG, 2.4 years (1.1–4.1) CWD or CWU with mastoid obliteration | Safe and not prone to adverse events. The positive effect of BAG is more prominently observed in revision procedures. | Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;274(12):4121–4126. |

3.3. Comparative Outcomes Based on Material Type

HA-based scaffolds were most commonly used and showed consistent obliteration success, long-term volume maintenance, and high biocompatibility. β-TCP scaffolds, while resorbable and osteoconductive, had mixed results in terms of volume preservation. Bioactive glass offered superior infection resistance and epithelialization benefits. Future comparative trials may help determine the superiority of each bioceramic type and composite formulation based on patient-specific factors and surgical indication.

Overall, the included studies demonstrated low to moderate risk of bias (Table 2 and Table 3). The most frequent sources of bias were confounding and participant selection, reflecting the predominantly retrospective and non-randomized study designs. Outcome measurement and reporting bias were generally low, as most studies reported objective clinical and radiologic outcomes. No study was judged to have a critical risk of bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies using the ROBINS-I.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies using the ROBINS-I.

| Study (First Author, Year) | Confounding | Selection of Participants | Classification of Intervention | Deviations from Intended Intervention | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement | Selective Reporting | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hashmi et al., 2025 [28] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Liu et al., 2025 [29] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low–Moderate |

| Chomarat et al., 2025 [30] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Kroon et al., 2025 [31] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low–Moderate |

| Zwierz et al., 2025 [32] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Kroon et al., 2023 [33] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low–Moderate |

| Leonard et al., 2021 [34] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Sorour et al., 2018 [35] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Sahli-Vivicorsi et al., 2022 [16] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low–Moderate |

| Yung et al., 2011 [36] | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate–Serious |

| Minoda et al., 2007 [37] | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate–Serious |

| Yanagihara et al., 2009 [38] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Vos et al., 2017 [23] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Table 3.

Risk of bias summary of included studies assessed using the ROBINS-I tool. Green indicates low risk, yellow indicates moderate risk, and red indicates serious risk of bias.

Table 3.

Risk of bias summary of included studies assessed using the ROBINS-I tool. Green indicates low risk, yellow indicates moderate risk, and red indicates serious risk of bias.

| Bias Domain | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | Serious Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confounding | 0 | 11 | 2 |

| Participant selection | 6 | 7 | 0 |

| Intervention classification | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Deviations from intervention | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing data | 9 | 4 | 0 |

| Outcome measurement | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| Selective reporting | 13 | 0 | 0 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Bioceramic Materials and Limitations

This systematic review highlights a paradigm shift in otologic surgery toward biologically active materials that support tissue regeneration. Compared to autologous materials, bioceramic scaffolds provide consistent structural support and excellent integration, particularly when combined with regenerative agents. HA remains the most widely studied and clinically implemented, with predictable outcomes in both volume preservation and patient tolerance.

Mastoid obliteration using bioceramic materials has evolved from a simple cavity-filling technique to a biologically driven reconstructive strategy. While BAG and HA-based materials provide excellent osteoconductive scaffolding and long-term volume stability, postoperative complications such as delayed epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and material exposure remain clinically relevant. These complications are frequently related to limited vascularization and delayed biological integration of the obliterated mastoid cavity.

The overall methodological quality of the available literature was acceptable, although limited by observational designs. Importantly, no study demonstrated a critical risk of bias, supporting the reliability of the reported safety and efficacy outcomes of bioceramic mastoid obliteration.

Limitations of this review include the predominance of observational studies, heterogeneity in surgical techniques, and inconsistent outcome reporting. Long-term, prospective comparative studies with standardized definitions are required to establish optimal material selection.

4.2. Future Direction

HA-based bioceramics demonstrate slower osteoconductive remodeling compared with BAG, which may contribute to delayed epithelialization. Application of synthetic and natural hydrogel scaffolds for bone tissue engineering that are motivated by the biology and structure of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

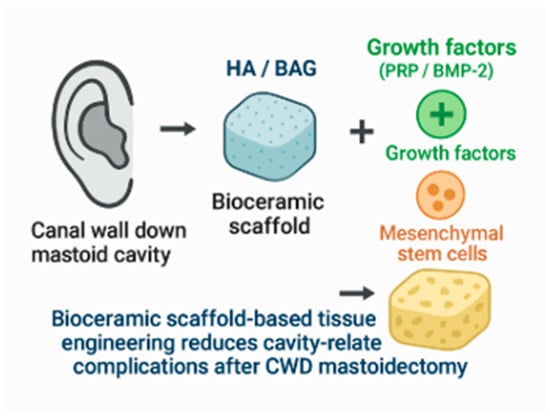

Emerging tissue engineering strategies integrating bioceramic scaffolds with biological adjuncts such as platelet-rich plasma, bone morphogenetic proteins, and mesenchymal stem cells show promise in accelerating osteogenesis and epithelialization. However, these approaches remain largely experimental in otologic surgery. The integration of growth factors and stem cells into scaffold design represents a key advancement. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are widely studied in orthopedic and craniofacial applications for enhancing osteogenesis. When applied to otologic surgery, these agents show promise in accelerating healing and reducing fibrosis within the obliterated cavity [15,39,40] (Table 4, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Table 4.

Tissue engineering strategies for bioceramic mastoid obliteration.

Table 4.

Tissue engineering strategies for bioceramic mastoid obliteration.

| Component | Example | Biological Role | Expected Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold | BAG (S53P4) | Osteoconduction, antibacterial | Volume stability, infection control |

| Growth factor | BMP-2 | Osteoinduction | Accelerated bone regeneration |

| Platelet product | PRP | Angiogenesis, healing | Reduced early complications |

| Cells | MSCs | Osteogenic differentiation | True bone regeneration |

BMP-2: bone morphogenic protein-2, PRP: platelet-rich plasma, MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

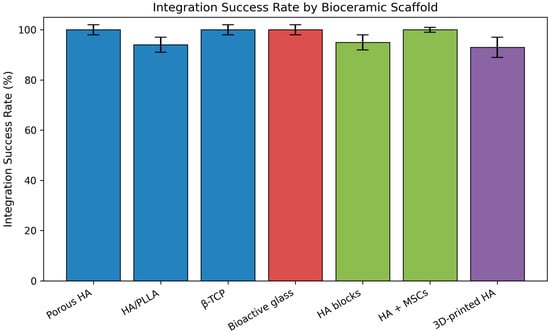

Figure 2.

Integration success rate according to different bioceramic scaffolds used for mastoid obliteration. Calcium phosphate-based materials, bioactive glass, tissue engineering-based scaffolds, and 3D-printed hydroxyapatite are displayed using distinct color groups. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. MSC (mesenchymal stem cell). Figures are schematic representations based on published literature and not derived from pooled quantitative analysis.

Figure 3.

Mastoid obliteration using bioceramics with a tissue engineering approach. Figures are schematic representations based on published literature and not derived from pooled quantitative analysis.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) represents a clinically feasible biological adjunct. As an autologous source of platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor-β, PRP enhances angiogenesis and soft tissue healing. PRP-augmented bioceramic obliteration may therefore reduce early postoperative complications such as persistent otorrhea and granulation tissue formation, which are among the most frequently reported minor adverse events following canal wall down mastoidectomy [41,42].

More advanced regenerative strategies incorporate mesenchymal stem cells seeded onto bioceramic scaffolds. Mesenchymal stem cells actively participate in osteogenesis and matrix remodeling, offering the potential for true biological reconstruction of the mastoid cavity [39,43,44,45,46]. Although these approaches remain largely experimental in otology, they may ultimately reduce long-term foreign-body reactions and improve radiologic interpretability during follow-up [47].

A growing area of interest is the use of custom 3D-printed scaffolds, which allow the material to conform precisely to irregular bone defects [6,40,48,49]. This level of personalization may lead to faster incorporation, lower complication rates, and better cosmetic results. Moreover, future iterations of bioceramic scaffolds may incorporate antibacterial ions, drug-eluting layers, or biosensors to monitor healing in real time. While the findings in this review are promising, most included studies were limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneity in surgical technique. Standardized outcome reporting and imaging protocols would aid in the comparison of future studies. Long-term follow-up studies are also essential to evaluate resorption rates, chronic inflammatory responses, and the durability of the scaffold in the middle ear environment.

Future clinical research should focus on prospective comparative studies evaluating bioceramic mastoid obliteration with and without biological augmentation. Standardized definitions of complications, long-term radiologic surveillance using diffusion-weighted MRI, and patient-reported outcome measures are essential to establish the true clinical value of tissue engineering-enhanced mastoid obliteration.

5. Conclusions

Bioceramic scaffolds, including HA, TCP, and BAG, are safe and effective materials for mastoid obliteration after canal wall down mastoidectomy. HA offers predictable long-term volume stability, whereas BAG provides additional antibacterial advantages. Future randomized controlled trials and standardized outcome reporting are necessary to determine material superiority and validate emerging tissue engineering approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and supervision: C.H.J.; data curation and formal analysis: K.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation: K.H.S.; writing—review and editing: C.H.J.; visualization: C.H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research fund from Chosun University Hospital, 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Poupore, N.S.; Gordis, T.M.; Nguyen, S.A.; Meyer, T.A.; Carroll, W.W.; Lambert, P.R. Tympanoplasty With and Without Mastoidectomy for Chronic Otitis Media Without Cholesteatoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 43, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, J.; Bakundukize, J.; Milinis, K.; Sharma, S.D. Mastoid obliteration versus canal wall down or canal wall up mastoidectomy for cholesteatoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoffer, J.L. Retrograde mastoidectomy. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 39, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, R.D.; Junior, F.C.; de Oliveira Fonseca, A.C.; Bento, R.F. Mastoid obliteration with autologous bone in mastoidectomy canal wall down surgery: A literature overview. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 20, 076–083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.B.G.; Rahimnejad, M.; Oliveira, R.; Sikder, P.; Saavedra, G.; Bhaduri, S.B.; Gawlitta, D.; Malda, J.; Kaigler, D.; Trichês, E.S.; et al. Personalized bioceramic grafts for craniomaxillofacial bone regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.T.; Wei, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhu, J.; Peng, Y.; Abdul Kadir, S.Y.; Zainol, J.; Oglah, Z.; Cheng, L.; Shi, Z. Bone Tissue Engineering through 3D Bioprinting of Bioceramic Scaffolds: A Review and Update. Life 2022, 12, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønseth, T.; Vestby, L.K.; Nesse, L.L.; Von Unge, M.; Silvola, J.T. Bioactive glass S53P4 eradicates Staphylococcus aureus in biofilm/planktonic states in vitro. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2020, 125, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leatherman, B.D.; Dornhoffer, J.L. The use of demineralized bone matrix for mastoid cavity obliteration. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 25, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwiwat, P.; Boonma, A.; Lee, Y.S.; Narayan, R.J. Bioceramics in ossicular replacement prostheses: A review. J. Long-Term Eff. Med. Implant. 2011, 21, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, K.W.K.; Kwok, M.M.K.; Shen, Y.; Gerard, J.M.; Teh, B.M. Materials used for mastoid obliteration and its complications: A systematic review. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeboom, J.J.; van Kempen, P.M.W.; Buwalda, J.; Westerlaken, B.O.; van Zuijlen, D.A.; Bom, S.J.H.; van der Beek, F.B. Mastoid obliteration with hydroxyapatite vs. bone pâté in mastoidectomy surgery performed on patients with cholesteatoma and chronic suppurative otitis media: A retrospective analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoulakis, C.; Koltsidopoulos, P.; Iyer, A.; Kontorinis, G. Mastoid Obliteration with Synthetic Materials: A Review of the Literature. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2019, 15, 400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, N.M.; Stecher, S.; Bächinger, D.; Schuldt, T.; Langner, S.; Zonnur, S.; Mlynski, R.; Schraven, S.P. Open Mastoid Cavity Obliteration with a High-Porosity Hydroxyapatite Ceramic Leads to High Rate of Revision Surgery and Insufficient Cavity Obliteration. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e55–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duta, L.; Oktar, F.N. Synthetic and Biological-Derived Hydroxyapatite Implant Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.H.; Cho, Y.B.; Choi, C.H.; Jang, Y.S.; Jung, W.K.; Lee, J.K. Comparision of osteoconductivity of biologic and artificial synthetic hydroxyapatite in experimental mastoid obliteration. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014, 134, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieux, M.; Tournegros, R.; Hermann, R.; Tringali, S. Allograft bone vs. bioactive glass in rehabilitation of canal wall-down surgery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesissa, M.; Sassoni, E.; Boi, M.; Borciani, G.; Boanini, E.; Graziani, G. Synthetic or Natural (Bio-Based) Hydroxyapatite? A Systematic Comparison between Biomimetic Nanostructured Coatings Produced by Ionized Jet Deposition. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workie, A.B.; Shih, S.J. A study of bioactive glass-ceramic’s mechanical properties, apatite formation, and medical applications. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23143–23152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubo, T. Bioactive glass ceramics: Properties and applications. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Jung, S.; Day, D.; Neidig, K.; Dusevich, V.; Eick, D.; Bonewald, L. Evaluation of bone regeneration, angiogenesis, and hydroxyapatite conversion in critical-sized rat calvarial defects implanted with bioactive glass scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2012, 100, 3267–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellucci, D.; Salvatori, R.; Giannatiempo, J.; Anesi, A.; Bortolini, S.; Cannillo, V. A New Bioactive Glass/Collagen Hybrid Composite for Applications in Dentistry. Materials 2019, 12, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skallevold, H.E.; Rokaya, D.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S. Bioactive Glass Applications in Dentistry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; de Vey Mestdagh, P.; Colnot, D.; Borggreven, P.; Orelio, C.; Quak, J. Bioactive glass obliteration of the mastoid significantly improves surgical outcome in non-cholesteatomatous chronic otitis media patients. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 4121–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellingman, C.A.; Geerse, S.; de Wolf, M.J.F.; Ebbens, F.A.; van Spronsen, E. Canal wall up surgery with mastoid and epitympanic obliteration in acquired cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli-Vivicorsi, S.; Alavi, Z.; Bran, W.; Cadieu, R.; Meriot, P.; Leclere, J.-C.; Marianowski, R. Mid-term outcomes of mastoid obliteration with biological hydroxyapatite versus bioglass: A radiological and clinical study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2022, 279, 4379–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.R.; Ehrenfried, L.M.; Saravanapavan, P.; Hench, L.L. Controlling ion release from bioactive glass foam scaffolds with antibacterial properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006, 17, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, T.; Mesgar, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z. Bioactive Glasses: A Promising Therapeutic Ion Release Strategy for Enhancing Wound Healing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5399–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmi, S.; Hussain, S.Z.M.; Matto, O.; Dewhurst, S.; Qayyum, A. To evaluate the results of mastoid obliteration and reconstruction of posterior meatal wall after canal wall down mastoidectomy using ready-to-use, self-setting hydroxyapatite bone cement. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2025, 139, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, N.; Li, S.; Guo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, M.; Yang, Q. Concentrated growth factors promote epithelization in the mastoid obliteration after canal wall down mastoidectomy. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 91, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomarat, J.; Fabre, C.; Schmerber, S.; Quatre, R. Evaluation of the effectiveness of bone obliteration in cholesteatoma surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 282, 5635–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, V.J.; Colnot, D.R.; Mes, S.W.; Borggreven, P.A.; van de Langenberg, R.; Quak, J.J. Mastoid Obliteration Using S53P4 Bioactive Glass Versus Mastoidectomy Alone for Refractory Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media. Otol. Neurotol. 2025, 46, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwierz, A.; Staszak, M.; Scheich, M.; Domagalski, K.; Hackenberg, S.; Burduk, P. A Comparison of the Sticky Bone Obliteration Technique and Obliteration Using S53P4 Bioactive Glass After Canal Wall Down Ear Surgery: A Preliminary Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, V.J.; Mes, S.W.; Borggreven, P.A.; van de Langenberg, R.; Colnot, D.R.; Quak, J.J. Efficacy of S53P4 Bioactive Glass for the Secondary Obliteration of Chronically Discharging Radical Cavities. OTO Open 2023, 7, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, C.G.; McNally, S.; Adams, M.; Hampton, S.; McNaboe, E.; Reddy, C.E.E.; Bailie, N.A. A Multicenter Retrospective Case Review of Outcomes and Complications of S53P4 Bioactive Glass. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2021, 17, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorour, S.S.; Mohamed, N.N.; Abdel Fattah, M.M.; Elbary, M.E.A.; El-Anwar, M.W. Bioglass reconstruction of posterior meatal wall after canal wall down mastoidectomy. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 39, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, M.; Tassone, P.; Moumoulidis, I.; Vivekanandan, S. Surgical management of troublesome mastoid cavities. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2011, 125, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoda, R.; Hayashida, M.; Masuda, M.; Yumoto, E. Preliminary experience with beta-tricalcium phosphate for use in mastoid cavity obliteration after mastoidectomy. Otol. Neurotol. 2007, 28, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, N.; Komori, M.; Hinohira, Y. Total mastoid obliteration in staged canal-up tympanoplasty for cholesteatoma facilitates tympanic aeration. Otol. Neurotol. 2009, 30, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.H.; Kim, W.; Kim, G. Effects of fibrous collagen/CDHA/hUCS biocomposites on bone tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 176, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Jang, C.H.; Kim, G.H. Highly elastic 3D-printed gelatin/HA/placental-extract scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4051–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, S.M.; Saber, I.M.; Omar, M. Mastoid Reconstruction with Platelet-Rich Plasma and Bone Pate After Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy: A Preliminary Report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, J.H.; Choo, O.S.; Choung, Y.H. Development of Intracorporeal Differentiation of Stem Cells to Induce One-Step Mastoid Bone Reconstruction during Otitis Media Surgeries. Polymers 2022, 14, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Kang, J.; Wang, C.; Lee, H.M.; Oh, S.J.; Pak, K.; Shin, N.; Lee, I.W.; Lee, J.; Kong, S.K. Human Tonsil-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Loaded Hydroxyapatite-Chitosan Patch for Mastoid Obliteration. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.H.; Cho, G.W.; Song, A.J. Effect of Bone Powder/Mesenchymal Stem Cell/BMP2/Fibrin Glue on Osteogenesis in a Mastoid Obliteration Model. In Vivo 2020, 34, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.H.; Park, H.; Cho, Y.B.; Song, C.H. Mastoid obliteration using a hyaluronic acid gel to deliver a mesenchymal stem cells-loaded demineralized bone matrix: An experimental study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jang, C.H.; Kim, G. Bone tissue engineering supported by bioprinted cell constructs with endothelial cell spheroids. Theranostics 2022, 12, 5404–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Fan, X.; Wu, H.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Qian, Y.; Kang, H. Mastoid obliteration and external auditory canal reconstruction using 3D printed bioactive glass S53P4/polycaprolactone scaffold loaded with bone morphogenetic protein-2: A simulation clinical study in rabbits. Regen. Ther. 2022, 21, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Q.; Rao, J.; Bei, H.P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X. 3D Bioprinting Photo-Crosslinkable Hydrogels for Bone and Cartilage Repair. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Singh, Y.P.; Datta, P.; Ozbolat, V.; O’Donnell, A.; Yeo, M.; Ozbolat, I.T. Strategies for 3D bioprinting of spheroids: A comprehensive review. Biomaterials 2022, 291, 121881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.