Abstract

This study focuses on estimating the nine parameters of the three-diode model (3DM) for photovoltaic (PV) cells by integrating the Atan-Sinc Optimization Algorithm (ASOA) with the Newton–Raphson (NR) method. The ASOA, a population-based metaheuristic approach inspired by the behaviors of the Sech and Tanh functions, systematically generates candidate solutions for the complete set of parameters in the 3DM. For each of these solutions, the NR method is employed to solve the transcendental equation governing the solar cell model, facilitating a precise evaluation of the associated objective function. To guide the parameter estimation process, experimental current-voltage (I-V) and voltage-power (V-P) curves are utilized. The robustness of the proposed methodology is validated through studies on both monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells. Computational results reveal that the ASOA effectively navigates the parameter space, while the NR method provides accurate evaluations, resulting in reliable and precise parameter estimations. All numerical validations were conducted using MATLAB software, version 2024b.

1. Introduction

The deployment of photovoltaic (PV) technology is pivotal in the global transition towards sustainable energy systems, addressing the urgent need for renewable energy resources [1,2]. Accurate modeling of PV cells is essential for enhancing energy efficiency, optimizing power electronics designs, and facilitating effective maintenance planning [3]. Among the various modeling approaches, the three-diode model (3DM) distinguishes itself due to its capability to accurately replicate the complex nonlinear behaviors exhibited by PV cells under varying environmental conditions, including low irradiance levels and partial shading scenarios [4]. The model effectively captures intricate recombination mechanisms through the inclusion of multiple exponential terms, while series and shunt resistances add a layer of realism to the electrical characterization of PV devices.

Despite its recognized accuracy, the practical implementation of the 3DM is constrained by the inherent complexity associated with estimating its nine nonlinear parameters that are crucial in the transcendental current equation [5]. Traditional parameter estimation methods—such as curve fitting, analytical rearrangement, or gradient descent—often struggle to reliably converge, particularly when initial estimates are significantly distant from the optimal values [6]. This has spurred a growing interest in the exploration of hybrid optimization strategies designed to tackle the high-dimensional and non-convex challenges posed by the parameter estimation problem [7].

Recent scholarly efforts have investigated various metaheuristic algorithms. For example, the work by [8] proposed a three-diode equivalent circuit model to more accurately describe the I-V behavior of large industrial silicon solar cells, showing that conventional one- and two-diode models were not sufficient to separate the different current components. This work used a particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm to estimate the parameters of both models from illuminated I-V measurements, reporting consistent results across multiple runs and a mean absolute error below 0.18% of .

The work by [9] introduced the genetic algorithm (GA) based on non-uniform mutation to estimate the unknown parameters of single- and double-diode PV models. The proposed GA was validated using experimental I-V and P-V data from several commercial silicon and polycrystalline modules under different temperature conditions, reporting a strong agreement between measurements and simulations. Furthermore, the proposed algorithm was also compared with multiple metaheuristic techniques, showing that the proposed method achieved lower root mean square error (RMSE) values and higher correlation coefficients, confirming its accuracy and robustness for real PV parameter estimation tasks.

The study by [10] introduced the drone squadron optimization (DSO) algorithm to estimate the 15 parameters of a three-diode equivalent model for solar PV systems. The proposed technique simulated the nonlinear relationship between the P-V and I-V curves, reducing the mismatch between experimental measurements and model predictions. In addition, the DSO algorithm was assessed using commercial RTC France and PhotoWatt PV modules under different climatic conditions, showing its superiority by providing more accurate parameter estimates compared to recent methodologies.

The authors by [11] presented an enhanced salp swarm algorithm (SSA) combined with differential evolution to estimate the internal parameters of a three-diode PV model. The proposed strategy incorporated a dynamic crowding-distance mechanism and was validated on a 200 kWp PV generation system across different weather conditions, showing that the three-diode configuration delivered more precise representations than conventional single- and two-diode models. Furthermore, the ESSA approach achieved superior parameter estimation accuracy compared with two benchmark optimization algorithms, highlighting its suitability for handling the increased complexity of three-diode PV modeling.

The work by [12] developed a hybrid differential evolution algorithm, enhanced with an electromagnetism-like mechanism, to improve the identification of parameters in triple-diode PV module models. The proposed differential evolution algorithm was validated using seven experimental datasets and incorporated an integrated mutation-per-iteration strategy, achieving lower root mean square error and mean bias error than several state-of-the-art techniques. Furthermore, the method demonstrated a significantly reduced execution time of 27.69 s, highlighting its efficiency and reliability for advanced PV parameter estimation tasks.

The authors by [13] examined the application of the marine walrus optimization (MWO) for extracting the parameters of single-, double-, and triple-diode PV models. The proposed strategy was evaluated using Newton–Raphson (NR) refinement and walrus-inspired foraging dynamics, enabling faster global exploration and notable RMSE reductions across all diode structures. Furthermore, the findings indicated that MWO algorithm consistently outperformed several state-of-the-art metaheuristic approaches, demonstrating strong robustness under varying irradiance conditions.

The study by [14] investigated a hybrid methodology for electrical parameter estimation in single-, double-, and three-diode PV models, combining the Equilibrium Optimization Algorithm (EOA) with the NR method to solve the underlying implicit equations. The proposed strategy was applied to experimental I-V data from a Kyocera KC200GT module under different irradiance levels and demonstrated a strong balance between computational efficiency and estimation accuracy, with the double-diode model yielding the lowest RMSE value. Furthermore, the results revealed that the hybrid EOA-NR approach effectively captured model-dependent variations in series resistance and ideality factors, confirming its reliability for nonlinear parameter identification in PV systems.

While previous methods have provided notable improvements, they often require extensive parameter tuning or multiple execution trials to achieve consistent performance. Furthermore, there has been a notable lack of research investigating the synergistic combination of global and local optimization methods, aimed at achieving a balanced approach that facilitates both exploration and precision during the fitting process [15]. To our knowledge, no study has previously proposed the integration of the Atan-Sinc Optimization Algorithm (ASOA) with a NR correction phase specifically for the parameter estimation of the 3DM.

The selection of ASOA as the global optimizer is motivated by its specific characteristics that align well with the challenges inherent to the 3DM parameter identification problem. The 3DM’s highly nonlinear, multidimensional, and multi-modal objective function, defined by a normalized quadratic error across current-voltage (I-V) and voltage-power (V-P) curves, presents a significant risk for metaheuristics to converge prematurely to local minima. Compared to other widely used metaheuristics (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization, Sine–Cosine Algorithm and Equilibrium Optimization Algorithm), ASOA offers distinct advantages:

- Inherent trigonometric balancing: ASOA’s core search dynamics, governed by the arctangent and cardinal sine (sinc) functions, inherently balance exploration and exploitation. The atan function smoothly transitions the search phase from global exploration to local refinement, while the sinc function promotes a dense, oscillatory search around promising regions. This intrinsic balance is crucial for navigating the complex 3DM parameter space without requiring excessive external parameter tuning.

- Reduced parameter sensitivity: The algorithm’s performance is less sensitive to its intrinsic control parameters than many population-based alternatives. This robustness minimizes the need for the extensive preliminary tuning often required by other methods to achieve reliable and consistent results for the 3DM.

- Enhanced local refinement capability: The oscillatory nature of the sinc-driven search provides a finer-grained local search mechanism compared to the often disruptive mutation or velocity-based updates of other algorithms. This characteristic makes ASOA particularly well-suited as a precursor to the NR local optimizer, as it can deliver solutions already situated in high-precision regions of the search space.

In this study, we introduce a novel hybrid estimation framework that leverages these complementary strengths. The ASOA functions as the global optimizer, effectively navigating the search space using its trigonometric dynamics. Subsequently, the NR algorithm is applied to deliver precise solutions for the implicit transcendental current equation at each iteration, ensuring mathematical consistency. Our optimization objective is articulated as a normalized quadratic error minimization, employing both experimental I-V and V-P curves to ensure a comprehensive fitting performance across diverse electrical characteristics.

This proposed integration of ASOA’s robust global search with NR’s deterministic local precision represents a targeted strategy to overcome the specific limitations observed in prior 3DM identification studies, promising improved accuracy, consistency, and convergence reliability.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an in-depth overview of the mathematical framework and physical interpretation of the 3DM. Section 3 elaborates on the proposed solution methodology, detailing the leader–follower hybrid optimization scheme. Section 4 outlines the test systems utilized for validation purposes, featuring both monocrystalline and polycrystalline PV cells. Finally, Section 5 presents the numerical results obtained from the study, and Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the findings and suggestions for future research directions.

2. Three-Diode Model for Solar Cells

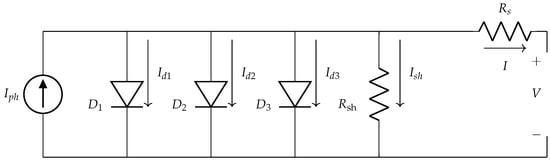

The 3DM serves as an improved electrical equivalent circuit that more accurately depicts the behavior of a solar cell (refer to Figure 1). This model features three diodes (, , and ) that represent distinct recombination processes occurring within the solar cell. Additionally, it includes a photocurrent source (), a shunt resistor () to account for leakage currents, and a series resistor () that signifies internal resistances. By incorporating these components, the 3DM effectively captures the intricate current-voltage characteristics of the solar cell, revealing the influence of various loss mechanisms and facilitating a comprehensive analysis of performance across different operational conditions.

Figure 1.

Equivalent electric circuit for a 3DM.

2.1. PV Cell Modeling

The output current I of a solar cell based on the 3DM is expressed as follows [3]:

where I represents the output current of the photovoltaic cell, is the photocurrent generated, is the current through diode i , V indicates the terminal voltage of the solar cell, is the series resistance, and corresponds to the shunt resistance.

Each diode current in (1) is modeled using the Shockley equation [15], as follows:

where is the reverse saturation current of diode i, signifies the ideality factor of diode i, q represents the electron charge ( C), k is the Boltzmann constant ( J/K), and T represents the cell temperature.

This formulation captures the nonlinear electrical behavior of the PV cell by accounting for multiple recombination pathways through the three diodes, as well as resistive losses. This comprehensive model facilitates a more accurate simulation and analysis of PV performance under varied environmental and operational conditions, which is critical for efficient system design and optimization.

Within the 3DM, each diode is specifically designed to represent a unique nonlinear loss mechanism occurring within the PV cell, enhancing the model’s ability to predict real-world cell behavior with greater fidelity:

- The first diode, , models the diffusion current generated in the quasi-neutral regions of the cell. Under typical conditions, this diode is the most significant and is characterized by an ideality factor close to 1, reflecting an ideal diffusion process.

- The second diode, , captures recombination phenomena occurring within the depletion region of the cell. This component becomes particularly crucial at lower voltages or under partial shading, typically showing an ideality factor around 2, indicating currents driven by recombination processes.

- The third diode, , accounts for more complex or non-ideal effects such as trap-assisted recombination, leakage currents, and interface phenomena like grain boundaries. Including this diode ensures the model remains accurate even under degraded or non-ideal operating conditions, where additional loss mechanisms can occur.

In addition to the diode components, the 3DM integrates resistive elements to emulate the parasitic losses inherent in real PV devices. For example, the series resistance models the ohmic losses accumulated due to contact resistances, metallic interconnections, and the intrinsic resistivity of the semiconductor materials [16]. Elevated values of lead to a decrease in the fill factor and overall power output, particularly under high-current conditions. Additionally, the shunt resistance represents unintended current pathways that bypass the ideal junctions, often due to manufacturing defects or encapsulation issues [5]. Lower values primarily affect low-voltage operation by reducing the open-circuit voltage and diminishing the cell’s efficiency.

This comprehensive modeling approach, combining multiple diode elements with resistive components, allows the 3DM to accurately simulate I-V and P-V characteristics across diverse environmental and operational scenarios [13]. Consequently, the 3DM proves effective for parameter estimation, fault detection, and the simulation of PV system performance in conditions of degradation or uneven irradiance, establishing itself as a valuable tool for advanced PV analysis and design.

2.2. Formulation of the Optimization Problem

To ensure that the error measurement is independent of scale and to facilitate comparability across various measurement conditions, we normalize the objective function using the norm of the measured current and power vectors. This normalization leads to a formulation of relative error that effectively captures the fitting precision of the 3DM across both I-V and P-V characteristics [17].

Let denote the vector containing the model parameters. The normalized objective function is defined as follows:

where is the vector containing the measured current values, corresponds to the vector of calculated current values, means the vector containing the measured power values, and corresponds to the vector of calculated power values.

In this context, the vectors utilized in the objective function (3) are defined as follows:

where ∘ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product.

This normalization ensures that both terms in the objective function represent relative errors relative to the total energy of the measured signals. Consequently, this prevents biases towards any one curve due to differences in scale, particularly when power and current values vary greatly.

The optimization process consists of evaluating the transcendental expression from Equation (1) at each voltage point , typically using the Newton–Raphson method or other root-finding techniques [18]. This model can be effectively addressed through hybrid optimization strategies that integrate global exploration (for instance, the Sech–Tanh Optimization Algorithm, ASOA) with local refinement. Utilizing ASOA reinforces the robustness of the optimization process by enabling an efficient exploration of the solution space and ensuring accurate convergence to optimal parameter estimates.

3. Solution Methodology

The proposed solution methodology utilizes a hybrid approach that integrates the global exploration capabilities of the ASOA with the local accuracy of the NR method [18]. The ASOA navigates the parameter space by generating candidate vectors for the 3DM. For each candidate solution, the NR algorithm resolves the nonlinear transcendental current equation at various voltage levels, allowing for the precise construction of model-predicted I-V and P-V curves [19]. This leader–follower framework promotes effective global optimization while ensuring numerical precision during the model evaluation.

3.1. Leader Stage: Atan-Sinc Optimization Algorithm

The ASOA is a metaheuristic optimization technique inspired by mathematical functions that explores the search space utilizing the Sech and Tanh functions [20]. Initially developed to tackle the optimal power flow problem within power systems, it has been successfully applied to a broad spectrum of nonlinear optimization challenges due to its straightforward implementation, minimal dependency on parameters, and effective balance between exploration and exploitation.

In this study, the ASOA is specifically applied to the parameter estimation problem associated with the 3DM of PV cells. The parameter vector consists of the nine parameters that require estimation. The subsequent subsection details how the ASOA has been adapted for this context.

3.1.1. Parameter Encoding and Initial Population

Each candidate solution generated by the ASOA represents a potential vector of parameters:

where denotes the solution in the population at iteration p. The initial population is created using the following formula:

where denotes a uniformly distributed random number, and and refer to the lower and upper bounds of parameter .

3.1.2. Advancing Rules

After initializing the population, the optimal solution at iteration p, denoted as , is determined as follows [19]:

where represents the objective function defined by the normalized quadratic error between the measured and calculated I-V and P-V curves (see Equation (3)).

Following this, each candidate solution is updated according to the following rule:

In this expression, for all , indicates the candidate solution for the upcoming iteration. where are random parameters dynamically generated in each iteration, and defines an exponential decreasing rule that balances the exploration and exploitation of the solution space. Mathematically, is defined as follows:

The arctangent function in (7) ensures controlled movements within a finite range, ideal for local exploitation, while the sinc function’s oscillatory behavior allows for a broad coverage of the search space, promoting effective global exploration. The parameter is randomly sampled within , ensuring sufficient diversity.

3.1.3. Boundary Correction

Following each parameter update, it is essential to ensure that the solution remains within the feasible region. This is accomplished by projecting the updated variables back to their respective bounds:

This correction mechanism guarantees that each updated parameter complies with the defined constraints, thereby preserving the physical feasibility of the solution.

3.1.4. Replacement Strategy

The new candidate solution will replace the previous solution only if it results in a superior objective function value:

This replacement criterion fosters the continuous improvement of the optimization process, ensuring that only solutions that enhance performance are retained.

3.1.5. Termination Criteria

The optimization algorithm concludes when one of the following conditions is satisfied:

- The maximum iteration limit is reached.

- The objective function displays no improvement over consecutive iterations, with typically set between 10% and 30% of .

These criteria ensure that the optimization process is both efficient and effective, allowing for timely conclusions while minimizing unnecessary computations.

3.1.6. Follower Stage: Newton–Raphson Solution for the 3DM Equation

In the proposed hybrid framework, the ASOA acts as the primary global optimizer, generating candidate parameter vectors . For each candidate, the implicit transcendental equation of the three-diode model must be solved to determine the corresponding current I for every voltage point. This equation, derived from combining (1) and (2), is given by

The NR method serves as a dedicated local solver for this equation, operating as a subordinate procedure to the ASOA [18]. This iterative follower ensures that each candidate solution evaluated by the global optimizer is associated with a numerically precise current value, thereby guaranteeing the consistency and accuracy of the objective function calculation throughout the optimization.

This equation must be solved for each voltage to determine the predicted current . The NR method is particularly effective for this purpose due to its rapid convergence for smooth, differentiable nonlinear equations.

Let represent the left-hand side of Equation (10) rearranged to formulate . The iterative process of the NR method is given by

where denotes the derivative of f with respect to I. The iteration continues until the relative difference between consecutive estimates meets a defined tolerance level, . This process is repeated for all voltage points to compile the vector , which is subsequently utilized to compute the objective function .

This follower stage guarantees that each candidate solution is evaluated with precision, aligning closely with the nonlinear characteristics exhibited by actual photovoltaic cells.

3.2. Implementation Algorithm

The hybrid ASOA-NR algorithm, presented in Algorithm 1, formalizes the leader–follower methodology described in the previous sections. The algorithm begins by initializing the ASOA population within the defined parameter bounds (Lines 3–4). The core optimization loop (Lines 5–24) iteratively executes the leader stage, where each candidate solution is evaluated through the NR follower (Lines 8–9) to calculate the objective function. Following evaluation, the ASOA updates the population using its characteristic advancement rules, applies boundary corrections, and implements the replacement strategy (Lines 12–15). A dual termination criterion monitors both maximum iterations and convergence stagnation (Lines 17–22). The follower stage, encapsulated in the NRsolver procedure (Lines 27–40), operates as a nested subroutine that solves the 3DM’s transcendental equation for each voltage point via Newton–Raphson iteration. This structured implementation ensures efficient global exploration through ASOA while maintaining numerical precision via the NR method, ultimately returning the optimal parameter vector for the three-diode model.

| Algorithm 1 Hybrid ASOA-NR Algorithm for 3DM Parameter Extraction |

| Require: Measured data , parameter bounds , population size , , , NR tolerance Ensure: Optimal parameter vector

|

4. Test Systems

In order to assess the performance and robustness of the proposed parameter estimation methodology, which integrates the ASOA with the Newton–Raphson (NR) method, we selected two prevalent PV technologies: monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells [21]. These technologies were chosen for their commercial significance and contrasting electrical characteristics.

Monocrystalline solar cells are widely recognized for their superior conversion efficiency, typically exceeding 20%, and their highly uniform crystalline structure, which enhances electron mobility and minimizes internal losses. This type of solar cell performs optimally under varying irradiance conditions, making it an ideal choice for high-performance solar energy systems. The reference parameters for the monocrystalline test case are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reference Parameters for the Monocrystalline Solar Cell.

In contrast, polycrystalline solar cells are produced using silicon that incorporates multiple crystalline structures, allowing for a more straightforward and cost-effective manufacturing process. Although these cells typically exhibit lower efficiency, ranging from 15% to 18%, they are favored in large-scale installations due to their affordability and mechanical resilience. The parameters for the polycrystalline test case are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reference Parameters for the Polycrystalline Solar Cell.

Both solar cell models were evaluated under standard ambient temperature conditions, maintaining a thermal voltage of 0.026 V. These configurations serve as reliable benchmarks for validating the accuracy and generalization capabilities of the hybrid optimization approach applied to parameter estimation.

The reference parameters presented in Table 1 and Table 2, used to generate the synthetic I-V and P-V data for validation, are based on typical values reported in the literature for silicon-based solar cells [8,22]. The photocurrent , series resistance , and shunt resistance were selected to represent realistic operating points for monocrystalline and polycrystalline technologies, respectively. The reverse saturation currents were set to a common order of magnitude ( A). A uniform ideality factor of was chosen for all three diodes in the reference models. This value serves as a standardized, intermediate benchmark within the typical reported ranges for silicon PV devices: the first diode (diffusion) often has a value near 1, the second (depletion region recombination) is frequently between 1.5 and 2, and the third (defect-assisted processes) can exceed 2 [22,23]. It is crucial to emphasize that these reference values are not inputs to the optimization algorithm but are used solely to create the “measured” dataset. The proposed ASOA-NR method’s objective is to demonstrate its capability to start from a broad, bounded search space (see Table 3) and converge to accurate parameter estimates without prior knowledge of these reference values, as successfully shown in the result sections.

Table 3.

Parameter variation ranges considered during the optimization process.

5. Numerical Validation

In this study, computational analyses were conducted using the MATLAB environment (version 2024a). The simulations were carried out on a personal computer equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 3700 processor operating at 2.3 GHz, with 16.0 GB of RAM, and running the 64-bit edition of Microsoft Windows 10 Single Language.

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed optimization methodology, experimental current-voltage (I-V) and power-voltage (P-V) curves were generated from measurements taken at intervals of 10 mV across a voltage range of 0 mV to 550 mV. To simulate realistic operating conditions, additive white noise was introduced at each measurement point, with random amplitudes fluctuating between 0% and 4%.

The configuration of the proposed hybrid ASOA-NR algorithm was designed to balance computational efficiency with robust and precise convergence. The ASOA was implemented with a population size of candidate solutions. This value was selected to ensure sufficient diversity for effective global exploration of the 9-dimensional parameter space of the 3DM, while remaining computationally manageable. The algorithm was executed over generations to guarantee thorough exploitation of promising regions and convergence to a stable optimum. To resolve the implicit current equation of the 3DM at each operating voltage, the NR method was applied. A strict convergence tolerance of was enforced to ensure the numerical precision required for accurate current calculation, with a maximum of 100 iterations allowed per NR call to prevent excessive computational overhead in cases of slow convergence. This combined configuration ensures that the global search is both comprehensive and that the local solutions underpinning the objective function evaluation are highly accurate.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed optimization approach, the parameter search space was defined using the variation ranges specified in Table 3. These ranges, which are applicable to monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells, were selected based on typical physical and electrical characteristics reported in the literature for such technologies [8].

5.1. Results for the Monocrystalline Cell

The application of the proposed ASOA produces the estimated parameters reported in Table 4. Note that the objective function value reached a final value of .

Table 4.

Estimated parameters for the monocrystalline solar cell.

The numerical analysis of the estimated parameters obtained through the application of the Adaptive Simulated Optimization Algorithm (ASOA) reveals a significant level of accuracy and alignment with the theoretical values for the monocrystalline solar cell, as illustrated in Table 1 and Table 4.

The estimated photogenerated current () of 4.666835 A closely parallels the theoretical reference value of 4.66 A, indicating a reliable prediction of the solar cell’s ability to convert sunlight into electrical energy. This close match suggests that the optimization approach employed effectively captured the primary characteristics of the solar cell’s performance during simulation.

In contrast, the saturation currents exhibited a notable discrepancy when compared to the theoretical expectations. The estimated value of saturation current ( A) is marginally below the theoretical benchmark of A, whereas saturation currents ( A) and ( A) exceed their theoretical counterparts. These deviations may highlight a more complex behavior of the diode junctions under operational conditions, potentially influenced by factors such as manufacturing variances, material properties, or additional recombination mechanisms not accounted for in the theoretical analysis.

Moreover, the ideality factors for the diodes, estimated at , , and , show a deviation from the typical theoretical value of 1.5. This variation suggests that the diodes may be operating under non-ideal conditions where recombination processes within the junctions influence the diode efficiency, leading to an increase in the ideality factor for and . Such insights could be crucial for future enhancements of the material or architecture of the solar cells.

The series resistance (), measured at 0.050318 , aligns well with the theoretical value of 0.05 , confirming that resistive losses in the circuit have been accurately modeled. Conversely, the shunt resistance () was found to be higher than the theoretical reference of 700.00 , which can be indicative of the cell’s improved leakage characteristics, potentially resulting from advanced manufacturing techniques or refinements in the cell design.

Lastly, the thermal voltage ( V) remained consistent across both experimental and theoretical assessments, affirming that the temperature effects on cell performance were adequately represented in the model. Overall, the results substantiate the effectiveness of the ASOA in accurately estimating critical parameters, although the observed disparities in saturation currents and ideality factors warrant further investigation into the specific mechanisms driving diode performance under varied operating conditions.

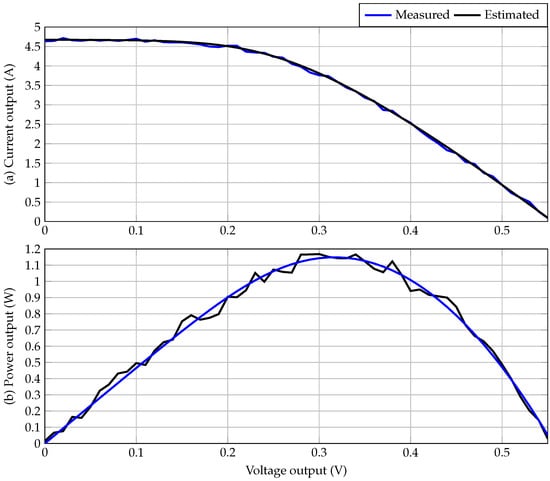

Figure 2 displays a comparative analysis of the measured and estimated current-voltage (I-V) and power-voltage (P-V) curves for the monocrystalline solar cell. In Figure 2a, the estimated current profile is shown to closely replicate the measured data across the full voltage spectrum. This indicates a robust performance of the estimation method, with only slight discrepancies observed in the knee region of the curve, where the transition from low to high current occurs. Such fidelity suggests that the hybrid estimation strategy effectively captures the nonlinear behavior characteristic of solar cell operation.

Figure 2.

Behavior of the measured and estimated I-V and P-V curves: (a) current behavior, (b) power output behavior.

In Figure 2b, the power output behavior is illustrated through the P-V curves. The estimated power profile accurately reflects the maximum power point, confirming the model’s capability to track the cell’s efficiency in converting sunlight into electrical energy. The observed alignment between the measured and estimated curves underscores the success of the proposed methodology in reproducing the electrical characteristics of the photovoltaic device.

However, minor variances in both the low-voltage and high-voltage ranges are noted, which can be attributed to potential measurement noise and the effects of parasitic resistances that naturally complicate precise modeling. Despite these discrepancies, the overall results serve to validate the reliability of the model across different operational scenarios, illustrating its effectiveness in approximating both current output and power delivery features of the solar cell.

5.2. Results on the Polycristalline Cell

The application of the proposed ASOA yielded the estimated parameters reported in Table 5. Note that the objective function value took a final value of .

Table 5.

Estimated parameters for the polycrystalline solar cell.

The estimated parameters for the polycrystalline solar cell, as detailed in Table 5, exhibit notable similarities and differences when compared to the reference parameters presented in Table 2.

The photogenerated current () is estimated at 3.692067 A, which is slightly higher than the reference value of 3.68 A. This close alignment suggests that the optimization approach used is effective in estimating the cell’s capacity to convert solar energy into electrical energy.

When examining the saturation currents, a more pronounced disparity is observed. The estimated saturation current ( A) exceeds the theoretical benchmark of A, indicating potential additional recombination processes within the diode that are not accounted for in the theoretical model. Similarly, the estimated saturation currents for ( A) and ( A) are below the theoretical value of A, suggesting variations in the junction characteristics that may arise from manufacturing differences or operational conditions.

The ideality factors present a diverse picture. The estimated values for (), (), and () deviate from the reference ideality factor of 1.5. This variation indicates that the diodes may be operating under non-ideal circumstances, influenced by factors such as doping levels, junction quality, or other recombination effects that lower the ideality factor.

In terms of resistance, the series resistance () closely matches the reference value of 0.02 , affirming the model’s accuracy in accounting for resistive losses in the circuit. However, the estimated shunt resistance () is somewhat lower than the reference value of 650.00 . This discrepancy may indicate an increased leakage current under specific operating conditions or limitations in the cell’s manufacturing quality.

Finally, the thermal voltage remains consistent at 0.026 V in both cases, confirming that the temperature effects on the solar cell were accurately modeled and the thermal characteristics are well understood in the context of solar energy conversion.

In summary, while the estimated parameters for the polycrystalline solar cell largely align with reference data, the observed deviations in saturation currents and ideality factors highlight the complexities in accurately modeling photovoltaic behavior and the potential effects of various operational and material factors that warrant further investigation.

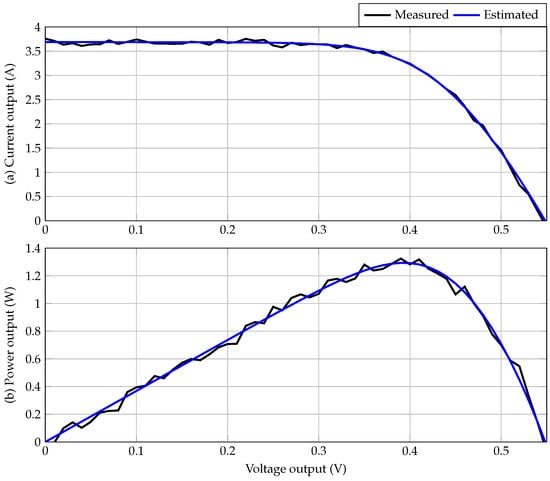

Figure 3 presents a comparative plot between the I-V and P-V curves, i.e., the measured and estimated curves.

Figure 3.

Behavior of the measured and estimated I-V and P-V curves for the polycristalline solar: (a) current behavior, (b) power output behavior.

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the estimated and measured current-voltage (I-V) and power-voltage (P-V) characteristics of the polycrystalline solar cell. In Figure 3a, the I-V curve demonstrates that the estimated current profile closely tracks the measured data across the entire voltage range, particularly exhibiting stability in the flat region where the current output remains nearly constant until reaching the knee voltage. Beyond this threshold, the estimated current demonstrates a consistent underestimation of the measured currents at elevated voltages. This slight deviation suggests that while the modeling accurately captures the operational dynamics of the photovoltaic cell, further refinements may be necessary to account for factors affecting higher voltage behavior, such as increased series resistance or limitations inherent to the diode model being utilized.

Figure 3b illustrates the P-V curve, where there is a strong concordance between the estimated and measured output power profiles. The peak power point is accurately represented in both magnitude and position, confirming that the estimation method effectively reflects the maximum power extraction potential of the solar cell. As the voltage approaches the open-circuit condition, the estimated power smoothly declines in a manner that is consistent with physical expectations, supporting the theory that output power should diminish as voltage increases beyond the operating range. This close alignment reinforces the validity of the proposed estimation methodology, emphasizing its capability to accurately model the electrical performance of polycrystalline solar cells under standard operating conditions. The overall strong agreement between the measured and estimated data underscores the methodology’s reliability for predicting both current regulation and power output, thereby facilitating enhanced understanding and optimization of photovoltaic devices.

5.3. Comparative Analysis

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed ASOA in estimating parameters for solar cells, a comparative analysis is performed against three distinct metaheuristic optimization methods: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [24], Sine–Cosine Algorithm (SCA) [25], and Equilibrium Optimization Algorithm (EOA) [14]. Each of these methods was configured with the same population size and number of iterations as the proposed approach. The evaluation emphasizes the final objective function values obtained for both monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells, as shown in Table 6. The objective function values, represented as , , and , offer valuable insights into the performance and robustness of each method in achieving parameter estimation.

Table 6.

Comparison of Metaheuristic Optimization Methods.

Note that to ensure statistical reliability and assess the algorithm’s robustness, the proposed hybrid ASOA-NR methodology was executed for 100 independent runs for each test case (monocrystalline and polycrystalline cells), each with a unique random seed for population initialization.

The results presented in Table 6 highlight the relative performance of the ASOA compared to other metaheuristic approaches—PSO, SCA, and EOA—in estimating parameters for both monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells. For the monocrystalline solar cell, the ASOA achieved a minimum objective function value of , which, while commendable, was outperformed by both the PSO and SCA methods, which recorded better maximum and mean values. Specifically, the PSO demonstrated a maximum objective function of and a mean of , indicating that these methods may be more effective in certain optimization contexts.

In examining the results for the polycrystalline solar cell, the ASOA recorded a minimum objective function value of , positioning it competitively among the other methods. However, PSO emerged with the highest maximum value of and a mean value of , highlighting its robustness in this scenario as well. Despite ASOA’s effective parameter estimation capabilities, the data suggest opportunities for refinement, particularly in its adaptability to varying types of solar cells. Notably, the consistently lower mean values achieved by the ASOA across both categories imply a potential for enhanced stability and reliability in performance. This consistency is a noteworthy trait; nonetheless, further optimizations and parameter tuning could enhance the ASOA’s performance, leading to even more accurate estimations under diverse operational circumstances.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study has successfully demonstrated that the proposed hybrid ASOA-NR methodology is an effective approach for accurately estimating the nine parameters of the 3DM for PV cells. The integration of the ASOA as a global explorer with the NR method as a local solver enabled a precise and robust fitting of the complex nonlinear current-voltage (I-V) and power-voltage (P-V) characteristics of both monocrystalline and polycrystalline solar cells.

The comparative analysis with well-established metaheuristics—PSO, SCA, and EOA—reveals that ASOA outperforms these methods in three key aspects critical for real-world parameter estimation tasks: Superior Consistency and Lower Average Error, demonstrated by achieving the lowest mean objective function values for both cell types (monocrystalline: ; polycrystalline: ), indicating enhanced reliability across multiple runs; Enhanced Stability and Reduced Variability, evidenced by a narrower error range that highlights intrinsic robustness and lower sensitivity to initial conditions, reducing the need for extensive trial repetitions; and Balanced Exploration–Exploitation, where ASOA’s trigonometric dynamics effectively navigate the 3DM’s high-dimensional search space, avoiding premature convergence and providing high-quality initial solutions for precise Newton-Raphson correction.

The practical implications of the proposed ASOA-NR framework are significant for real-world PV applications, offering valuable tools for Advanced PV Diagnostics and Characterization through precise parameter extraction for performance assessment and quality control; enabling Digital Twin Development by creating highly accurate simulation models for system design and energy forecasting; and facilitating Power Electronics Optimization by providing reliable parameters for the design and tuning of maximum power point tracking (MPPT) controllers to improve overall system efficiency.

Looking ahead, future research will focus on three main directions to advance the proposed methodology. First, the validation will be extended to a wider array of commercial PV modules under diverse, realistic operating conditions, including non-standard scenarios such as high temperatures and partial shading, to thoroughly assess the algorithm’s generalization capability and robustness. Second, adaptive mechanisms for the algorithm’s internal parameters will be investigated to enhance its autonomy and performance across different PV technologies. Finally, the integration of the proposed hybrid framework into embedded systems or dedicated software tools will be explored to enable on-site, rapid PV system characterization and monitoring for practical field applications.

By addressing the specific challenges of 3DM parameter identification with a method that combines robust global search with high numerical precision, this work provides a valuable and practical tool for advancing photovoltaic modeling, system optimization, and the broader adoption of sustainable energy technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing (review and editing): D.F.M.-T., O.D.M., J.C.H., W.G.-G. and L.F.G.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Thematic Network 723RT0150, i.e., Red para la integración a gran escala de energías renovables en sistemas eléctricos (RIBIERSE-CYTED), funded through the 2022 call for thematic networks of the CYTED (Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of AI-based tools, including ChatGPT 5.1 (OpenAI), which assisted in refining the manuscript’s structure, language, and clarity. These tools were used only to improve presentation and did not alter the underlying ideas, analyses, or scientific integrity of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali, A.O.; Elgohr, A.T.; El-Mahdy, M.H.; Zohir, H.M.; Emam, A.Z.; Mostafa, M.G.; Al-Razgan, M.; Kasem, H.M.; Elhadidy, M.S. Advancements in photovoltaic technology: A comprehensive review of recent advances and future prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cang, T. Comprehensive Exploration of Solar Photovoltaic Technology: Enhancing Efficiency, Integrating Energy Storage, and Addressing Environmental and Economic Challenges. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 123, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullampalayam Murugaiyan, N.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Devapitchai, M.M.; Senjyu, T. Parameter Estimation of Three-Diode Photovoltaic Model Using Reinforced Learning-Based Parrot Optimizer with an Adaptive Secant Method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Marghichi, M.; Hilali, A.; Chellakhi, A.; Makhad, M.; Loulijat, A.; El Ouanjli, N.; Essounaini, A.; Kumar Saini, V.; Saad Al-Sumaiti, A. Accurate extraction of electrical parameters in three-diode photovoltaic systems through the enhanced mother tree methodology: A novel approach for parameter estimation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćalasan, M.; Abdel Aleem, S.H.; Zobaa, A.F. A new approach for parameters estimation of double and triple diode models of photovoltaic cells based on iterative Lambert W function. Sol. Energy 2021, 218, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.P.; Aljaidi, M.; Maheshwari, S.; Arpita; Jangir, P.; Jangid, R.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, G.; Rani, R.; Khishe, M. Robust parameter estimation in solid oxide fuel cells using a multi strategy improved crayfish optimization algorithm. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazab, O.S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Alsaidan, I.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Muyeen, S.M. Parameter Estimation of Three Diode Photovoltaic Model Using Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm. Energies 2020, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, V.; Das, B.; Bisht, D.; Vandana; Singh, P. A three diode model for industrial solar cells and estimation of solar cell parameters using PSO algorithm. Renew. Energy 2015, 78, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, D.; Elyaqouti, M.; Assalaou, K.; Ben hmamou, D.; Lidaighbi, S. Parameters optimization of solar PV cell/module using genetic algorithm based on non-uniform mutation. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 12, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.A.; Basha, C.H.H.; Puppala, R.; Fathima, F.; Dhanamjayulu, C.; Chinthaginjala, R.; Mohammad, F.; Khan, B. Application of DSO algorithm for estimating the parameters of triple diode model-based solar PV system. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.M.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, S.J.; Yang, S.P.; Huang, P.Y.; Chiu, C.H. Parameters Estimation of PV Modules for a Three-Diode Model Using an Enhanced Salp Swarm Algorithm. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Bristol, UK, 25–27 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsen, D.H.; Haider, H.T.; Al-Nidawi, Y. Parameter Identification in Triple-Diode Photovoltaic Modules Using Hybrid Optimization Algorithms. Designs 2024, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, A.; Kumar, V.; Pathak, D.; Tummala, A.S.L.V.; Sharma, S.; Kuppan, V.; Kumar, V. Improved Extraction of Parameters of Solar PV Cell Diode Model Using Marine Walrus Inspired Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 181217–181231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Acosta, J.C.; Montoya Giraldo, O.D.; Trujillo Rodríguez, C.L. Electrical parameter estimation in solar cells using single-, double-, and three-diode models. Stat. Optim. Inf. Comput. 2025, 14, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Gil-González, W.J.; López-Lezama, J.M. Vortex Search Algorithm Applied to the Parametric Estimation in PV Cells Considering Manufacturer Datasheet Information. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2021, 19, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, A.S.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Assessment of an Improved Three-Diode against Modified Two-Diode Patterns of MCS Solar Cells Associated with Soft Parameter Estimation Paradigms. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changmai, P.; Deka, S.; Kumar, S.; Babu, T.S.; Aljafari, B.; Nastasi, B. A Critical Review on the Estimation Techniques of the Solar PV Cell’s Unknown Parameters. Energies 2022, 15, 7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlazi, N.J.; Mayengo, M.; Lyakurwa, G.; Kichonge, B. Mathematical modeling and extraction of parameters of solar photovoltaic module based on modified Newton–Raphson method. Results Phys. 2024, 57, 107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Gil-González, W.; Bolaños, R.I.; Muñoz-Torres, D.F.; Hernández, J.C.; Grisales-Noreña, L.F. Effective Power Coordination of BESUs in Distribution Grids via the Sine-Cosine Algorithm. In 2024 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Branson, MO, USA, 17–19 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A Sine Cosine Algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.E.; Kamel, S.; Khurshaid, T.; Oh, S.R.; Rhee, S.B. Parameter Extraction of Three Diode Solar Photovoltaic Model Using Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouder, A.; Silvestre, S.; Sadaoui, N.; Rahmani, L. Modeling and simulation of a grid connected PV system based on the evaluation of main PV module parameters. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2012, 20, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qu, J.; Wu, Z. Mechanical reliability of flexible encapsulation of III-V compound thin film solar cells. Sol. Energy 2021, 214, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrag, A.; Messalti, S. Three, Five and Seven PV Model Parameters Extraction using PSO. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Hernández-Mora, J.A.; Rivera, J.D.P. Parameter Estimation of Solar Cells Based on the Three-Diode Model via the Sine-Cosine Algorithm. In 2025 IEEE Colombian Conference on Applications of Computational Intelligence (ColCACI), Cali, Colombia, 7–9 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.