Abstract

This article presents a hybrid optimization model designed to determine the optimal location and operation of capacitor banks in medium-voltage distribution networks, aiming to reduce energy losses and enhance the system’s economic efficiency. The use of reactive power compensation through fixed-step capacitor banks is highlighted as an effective and cost-efficient solution; however, their optimal placement and sizing pose a mixed-integer nonlinear programming optimization challenge of a combinatorial nature. To address this issue, a multi-objective optimization methodology based on the Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) is proposed to identify the ideal location and capacity of capacitor banks within distribution networks. This model simultaneously focuses on minimizing technical losses while reducing both investment and operational costs, thereby producing a Pareto front that facilitates the analysis of trade-offs between technical performance and economic viability. The methodology is validated through comprehensive testing on the 33- and 69-bus reference systems. The results demonstrate that the proposed SCA-based approach is computationally efficient, easy to implement, and capable of effectively exploring the search space to identify high-quality Pareto-optimal solutions. These characteristics render the approach a valuable tool for the planning and operation of efficient and resilient distribution networks.

1. Introduction

Energy efficiency in electrical distribution networks is critical for ensuring a sustainable and reliable power supply. A primary challenge in achieving this efficiency is the significant technical and economic impact of energy losses, which can account for 5% to 10% of the total energy supplied [1]. These losses, caused mainly by the Joule effect in conductors, are exacerbated by suboptimal voltage profiles, which further degrade system stability and increase operational costs [2,3].

The strategic installation of capacitor banks for reactive power compensation is a well-established method to mitigate these issues. By improving voltage regulation and reducing line losses, capacitor placement enhances the overall performance and capacity of distribution networks [4,5]. However, determining the optimal locations and sizes of these devices is a complex mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem. Its combinatorial and non-convex nature makes finding a globally optimal solution particularly challenging [6].

To address this challenge, numerous metaheuristic approaches have been proposed, including genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and various hybrid methods [7,8]. While these techniques have demonstrated satisfactory results, they often require intricate parameter tuning and incur substantial computational costs, which can limit their practical applicability in real-world planning scenarios [1].

In this context, the SCA has emerged as a promising alternative due to its straightforward implementation, minimal parameter requirements, and effective balance between exploration and exploitation during the search process [9]. Its efficacy has been validated in several power system optimization problems, such as storage integration [10] and loss estimation [11]. However, its application to the multi-objective capacitor placement problem, which necessitates a simultaneous consideration of conflicting technical and economic criteria, remains underexplored.

Multi-objective optimization provides a natural framework for this problem by generating a set of compromise solutions—known as the Pareto front—that allow system planners to analyze trade-offs between loss reduction and investment costs [12,13]. This approach facilitates informed decision-making without relying on predefined weighting schemes.

Motivated by the need for an efficient, robust, and easily implementable planning tool, this paper proposes a Multi-Objective Sine Cosine Algorithm (MOSCA) for the optimal placement and sizing of capacitor banks in distribution networks. The primary contributions of this work are:

- The development of a multi-objective SCA framework tailored for the capacitor placement MINLP problem.

- A comprehensive numerical validation on standard 33- and 69-bus test systems configured in both radial and meshed topologies.

- An analysis of the trade-offs involved in deploying between one and five fixed-step capacitor banks, providing planners with a practical decision-support tool.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 formulates the optimal capacitor placement problem as a MINLP model. Section 3 details the proposed MOSCA methodology. Section 4 describes the test systems and simulation setup. Section 5 presents the numerical validations and resulting Pareto fronts. Section 6 discusses the implications and limitations of the approach. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the key findings and suggests directions for future research.

2. Mathematical Modeling for Fixed-Step Capacitor Allocation

This study centers on the optimal allocation of fixed-step capacitor banks within distribution networks. The problem is formalized through an MINLP model, which establishes a connection between binary installation variables and the continuous, nonlinear, and non-convex variables that are inherent to power flow analysis [8]. Despite the availability of advanced optimization algorithms, this work aims to showcase that a well-structured approach employing the SCA can efficiently yield high-quality, sub-optimal solutions while maintaining low computational complexity and minimal parameter tuning requirements [9].

2.1. Objective Function

The objective of the model is to minimize the total system cost expressed in net present value (NPV), which includes the cost of energy losses in the distribution network as well as the investment and operation/maintenance costs of the installed capacitor banks over a multi-year planning horizon [5]. The total NPV cost, denoted as , is defined as the sum of two components as presented in (1):

where represents the net present value of the annual energy loss costs and the net present value of the total investment and operational cost of the installed capacitors.

The components and of the objective function are defined mathematically in Equations (2) and (3), as follows [5]:

where . The binary variable indicates whether a capacitor of type c is installed at node i. The model uses the following sets: N for all nodes in the network, H for the time periods considered in the analysis, C for the available capacitor types, and Y for the years within the planning horizon, which is implicitly accounted for in the net present value factors and .

The model parameterization includes the energy cost , the economic discount and escalation rates (, , ), and the technical–economic data of the capacitors (, , , ). Additionally, two net present value (NPV) constants, and , are defined to convert future annual costs into present values. Their formulations are given by Equations (4) and (5):

where , defined in (4), aggregates the present value of the energy loss costs over the planning horizon Y, and , defined in (5), represents the present value factor for the recurring operation and maintenance expenditures of the capacitors.

Remark 1.

The MINLP nature of the problem arises from the structure of its components: introduces non-convexity and nonlinearity via voltage bilinear terms and trigonometric functions, while contributes integer variables in a linear cost expression. This specific structure motivates the application of population-based metaheuristics, which are well-suited for navigating such discontinuous and non-convex search landscapes.

2.2. Set of Constraints

The proposed model must satisfy the standard operational constraints of distribution systems to ensure feasible network operation and to impose physical and economic limits on capacitor installations [5]. These constraints are defined as follows.

2.2.1. Power Balance Constraints

The fundamental physical laws governing power flow are enforced through active and reactive power balance equations at every node and time period.

Equation (6) establishes the active power balance at node i during period h, ensuring that the net active power injection () equals the total active power flow into the network branches connected to that node:

Equation (7) enforces the reactive power balance, incorporating the contribution from installed capacitor banks:

here, the term represents the total reactive power injection from a capacitor of type c if installed at node i ().

2.2.2. Operational Limits

Technical limits for safe and reliable system operation are modeled as box constraints.

The active and reactive power output of generators or substations at each node are bounded by their minimum and maximum capacities:

Similarly, nodal voltage magnitudes must remain within statutory or operational limits to ensure power quality and equipment safety:

2.2.3. Capacitor Placement Constraints

Logical and budgetary restrictions on capacitor installation are defined as follows.

The total number of capacitors installed across the network cannot exceed a predefined budgetary or physical limit :

To prevent oversizing and ensure practical installation, at most one type of capacitor can be placed at any given node:

Finally, the installation decision is modeled as a binary variable:

Remark 2.

The model’s structure—integrating non-convex AC power flow constraints with discrete decision variables—defines a mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem that is computationally intractable for exact methods in large-scale networks. The resulting search space exhibits both combinatorial explosion (from the placement choices) and non-convex, multimodal terrain (from the power flow physics). This dual complexity fundamentally necessitates heuristic or metaheuristic search strategies [1,6,7]. The core methodological question addressed in this work is whether the specific balance of exploration and exploitation in the Sine Cosine Algorithm provides a robust and efficient search mechanism for this challenging class of power system optimization problems.

The following section elaborates on the SCA and its implementation. The objective is to assess whether this randomized approach can achieve high-quality solutions without the added complexity of advanced metaheuristic operators [9,10,11].

2.3. Solution Strategy

The multi-objective optimization problem, formalized as an MINLP model, integrates discrete variables related to capacitor bank placement with continuous variables representing reactive power and nodal voltage profiles. This combination leads to a highly nonlinear and non-convex problem structure, which poses significant challenges for traditional deterministic solution methods [14].

To address this complexity, a metaheuristic approach based on the SCA is employed. This algorithm harnesses the harmonic oscillation of sine and cosine functions to effectively navigate the solution space, targeting promising regions that may provide optimal configurations [9,11].

Within this framework, the SCA generates candidate configurations for reactive compensation, which are assessed using a penalized objective function that ensures both operational feasibility and economic efficiency [5]. The non-dominated solutions obtained from this process establish the Pareto front, illustrating the trade-offs between minimizing technical losses and reducing total costs associated with investment and operation [14,15]. This hybrid methodology successfully achieves a balance between global exploration and local exploitation, facilitating the efficient resolution of high-dimensional MINLP problems within electric distribution networks.

The proposed strategy guarantees a thorough exploration of the search space while rigorously adhering to the operational and technical constraints of the problem. Simulation results—validated on IEEE 33-bus and 69-bus distribution networks—demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness in achieving substantial reductions in both technical power losses and annualized investment costs compared to conventional fixed-compensation strategies. Furthermore, the developed solution methodology exhibits robust scalability and practical relevance for real-world distribution system planning, reinforcing its capability to solve complex, high-dimensional MINLP optimization problems in power networks.

3. Multi-Objective Optimization Methodology

The SCA, introduced by Mirjalili in 2016, is a population-based metaheuristic that guides its search process using mathematical models of sine and cosine functions [9]. These trigonometric operators dynamically adjust the movement of candidate solutions, enabling an adaptive transition from broad global exploration to intensive local exploitation throughout the iterative process [6,16]. A key advantage of SCA is its methodological simplicity and minimal parameter dependency, which reduces computational overhead and facilitates straightforward implementation compared to more complex metaheuristics like genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization [13].

3.1. Operating Principle

The SCA operates by updating the positions of candidate solutions based on trigonometric equations involving sine and cosine functions [17]. These mathematical representations determine both the direction and magnitude of movement towards the currently best-known solution [3].

The search process comprises two critical stages [8,10]:

- Exploration: In this phase, solutions undergo large-amplitude movements throughout the search space, allowing for extensive coverage of the solution landscape and helping to avoid premature convergence to local optima.

- Exploitation: During exploitation, the movements become more constrained, enabling a focused refinement of the search around areas identified as promising based on previous evaluations.

The transition between exploration and exploitation is governed by an adaptive parameter that modulates the amplitude of the sine and cosine functions, progressively fine-tuning the search intensity throughout the iterations [2,5,13].

3.2. Multi-Objective Extension

The Multi-Objective Sine Cosine Algorithm (MO-SCA or MOSCA) extends the original single-objective formulation [9] to handle problems with multiple, often conflicting, objectives. In the context of capacitor placement, these objectives typically include the minimization of active energy losses and the total cost of investment, operation, and maintenance [8,10,12].

The core goal of MO-SCA is to identify a set of optimal trade-off solutions, known as the Pareto-optimal front. Each solution in this front is non-dominated, meaning it cannot be improved in one objective without degrading another. By mapping these trade-offs, the algorithm provides system planners with a spectrum of feasible configurations, enabling informed decision-making that balances technical performance against economic expenditure [12].

For distribution network optimization, this multi-objective capability is crucial. It allows for the systematic exploration of how different levels of reactive power compensation affect both grid efficiency (e.g., loss reduction, voltage profile) and capital/operational costs. Consequently, MO-SCA facilitates the identification of practical, cost-effective compensation strategies that are both computationally efficient to obtain and directly applicable in planning scenarios [5,11].

3.3. Population Initialization and Evaluation

The algorithm begins by generating a random initial population of candidate solutions. Each solution (for ) is then evaluated using a penalized objective function . This function simultaneously measures solution quality (objective value) and penalizes constraint violations, thereby integrating feasibility directly into the search process [1,7,8].

The best individual in the population at iteration t, denoted , is identified as the solution with the minimal penalized objective value:

this individual serves as a guiding solution for the subsequent update mechanisms of the algorithm.

3.4. Evolution Rules

The generation of new solutions is accomplished using sine and cosine functions to explore the vicinity of the current best solution, as expressed in the following equation [5,9,10]:

In this formulation, , , , and are random parameters that govern the amplitude, frequency, and direction of the movements of the solutions [11].

3.5. Solution Correction and Feasibility Enforcement

Each candidate solution generated during the search must be validated against the problem’s variable bounds and operational constraints. A dedicated correction step is applied to any solution violating these limits, ensuring that the population remains within the feasible search space throughout the optimization process.

For continuous variables that exceed their prescribed bounds , a simple projection mechanism is applied. The violating variable is relocated to the nearest feasible point within the boundary, offset by a small tolerance to avoid numerical issues associated with exact boundary values:

This projection operator preserves the exploratory intent of the metaheuristic while guaranteeing that all solutions passed to the objective function evaluator are structurally feasible with respect to variable limits.

3.6. Algorithm Implementation

The SCA is a population-based metaheuristic that employs trigonometric functions to navigate complex search spaces, making it well-suited for nonlinear and mixed-integer optimization. Its iterative process updates candidate solutions using sine and cosine transformations, guided by a leader solution. An adaptive amplitude parameter within these transformations automatically balances global exploration and local exploitation throughout the search.

Our multi-objective SCA (MO-SCA) implementation is structured around three core components (see Algorithm 1): (i) modular population initialization, (ii) a penalized objective function that simultaneously evaluates performance and feasibility, and (iii) an elitist, non-dominated sorting mechanism for leader selection. This design ensures robust convergence and numerical stability in non-convex decision spaces.

- Procedure Overview:

- Step 1:

- Initialization: Randomly generate an initial population within the defined variable bounds. Evaluate each solution using the multi-objective functions and perform non-dominated sorting to identify the first Pareto front. Select a leader from this front to guide the initial search.

- Step 2:

- Iterative Search: For each iteration until the maximum is reached:

- (a)

- Position Update: Update candidate positions using sine and cosine operators, referencing the current leader.

- (b)

- Feasibility Enforcement: Apply boundary correction to maintain all solutions within feasible limits.

- (c)

- Evaluation and Ranking: Re-evaluate the updated population and perform non-dominated sorting to reconstruct Pareto fronts.

- (d)

- Leader Selection: Randomly select a new guiding leader from the first non-dominated front.

- Step 3:

- Termination: Upon reaching the maximum number of iterations, output the final set of non-dominated solutions representing the approximate Pareto front.

| Algorithm 1 Sine-Cosine Algorithm |

|

This algorithmic framework facilitates the effective integration of the SCA into multi-objective optimization applications and hybrid architectures requiring complementary solvers. The core mechanism of the algorithm, based on the trigonometric update approach, allows for the dynamic adjustment of both the amplitude and direction of the search. Additionally, its modular implementation in MATLAB Version 2025b simplifies the configuration of diverse population strategies, penalized evaluations, and procedures for determining Pareto dominance. Consequently, this high adaptability not only enhances convergence reliability but also broadens the applicability of the SCA across various engineering optimization challenges, particularly in the domain of power system analysis.

3.7. Visualization and Decision-Making

The application of the SCA in the optimization process results in the generation of a Pareto front, which effectively represents the trade-off between the system’s technical objectives—such as loss reduction—and its economic objectives, notably the total compensation cost. This Pareto front is visualized in a two-dimensional space defined by and , facilitating a clearer interpretation of the balance between energy efficiency and economic viability.

Regions of the front that are continuous and smooth indicate stable configurations and high-quality solutions, whereas abrupt or scattered segments reveal conflicts between competing criteria. This visualization enables decision-makers to incorporate additional selection criteria—such as identifying knee points, assessing the cost-benefit ratio, and ensuring compliance with operational constraints—allowing for the selection of the most relevant solution from both technical and financial perspectives.

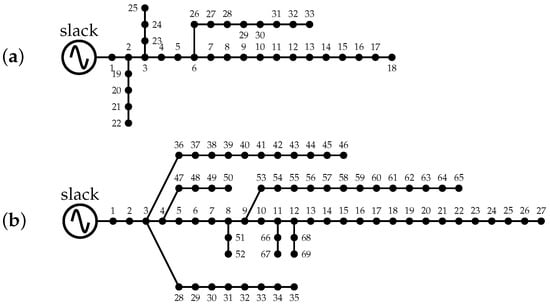

4. Test Systems

The performance evaluation of the proposed methodology was conducted using four standard test systems: two featuring radial topology and two utilizing meshed topology, each consisting of 33 and 69 nodes, respectively [18]. The layout of the feeders is illustrated in Figure 1, while the electrical parameters, including impedances and peak demands, are detailed in Table 1 and Table 2. All networks operate at a nominal line-to-ground voltage of , with voltage limits established between and p.u. [18]. The choice of these test systems, which are commonly employed as benchmark references in the literature, enables a rigorous comparison with previous studies [5,14] and enhances the validation of power flow models and optimization algorithms in distribution networks [19].

Figure 1.

Radial topologies of the test systems: (a) 33-node and (b) 69-node feeders.

Table 1.

Main parameters for the 33-node test system.

Table 2.

Main parameters for the 69-node test system.

4.1. Radial Configurations

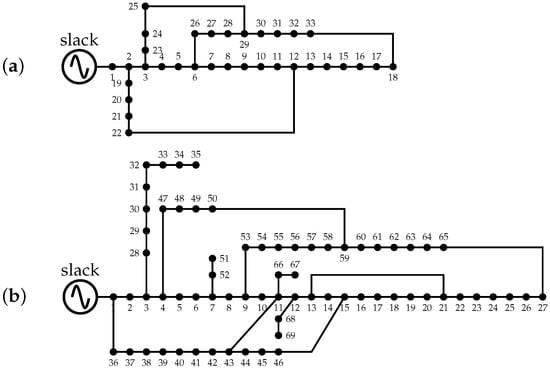

4.2. Meshed Meshed

The meshed versions of the 33- and 69-node feeders were obtained by adding tie-lines to their corresponding radial topologies. The resulting configurations are depicted in Figure 2, respectively, while the electrical parameters of the additional lines are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. The same voltage and power bases were maintained for both radial and meshed configurations.

Figure 2.

Meshed topologies of the test systems: (a) 33-node and (b) 69-node feeders.

Table 3.

Additional lines for the 33-node meshed test system.

Table 4.

Additional lines for the 69-node meshed test system.

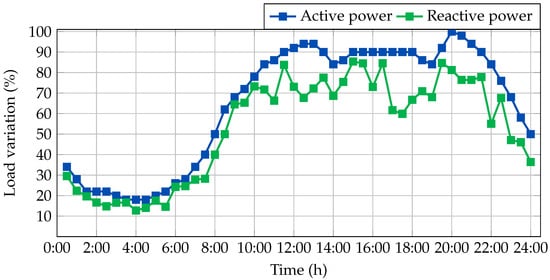

4.3. Time-Varying Load Profile

To evaluate the performance of the proposed methodology, the 33- and 69-node distribution feeders were assessed under a time-varying load profile designed to emulate realistic daily demand variations. The reference power demand at each node, derived from the peak values presented in Table 1 and Table 2, was adjusted over the simulation horizon based on the hourly load variation factors depicted in Figure 3. These scaling factors represent the percentage fluctuations in demand throughout a typical day, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of the operational dynamics within the networks [20]. This approach provides a more accurate evaluation of the effectiveness of fixed-step capacitor banks (FSCs) in mitigating reactive power and enhancing voltage profiles, aligning with the practical challenges faced in modern distribution network operations.

Figure 3.

Daily variations in active and reactive power at the substation terminals, measured in 30 min intervals. (Reprinted from Ref. [21]).

It is worth noting that the y-axis in the figure illustrates the daily variations in active and reactive power, represented as percentage values relative to their respective peak values at the substation terminal. This normalization follows standard practices in power system analysis, facilitating straightforward comparisons across different systems and operational scenarios [5].

To compute the total net present cost (NPC) objective function—which aggregates the present value of energy losses over the planning horizon with the investment, installation, and annual operating costs of fixed-step capacitor banks—the economic and operational parameters listed in Table 5 were employed. These values reflect typical utility planning assumptions and standard economic conditions for mid-term distribution system analysis.

Table 5.

Economic and operational parameters for the net present cost calculation.

5. Simulation Results

For the computational implementation of the proposed optimization framework, MATLAB R2025b was used on a personal computer equipped with an Inter® Core™ i5-8265U (1.6 GHz), 12.0 GB of RAM, and a 64-bit version of Windows 10. The algorithm was implemented using custom scripts.

5.1. Simulation Setup and Algorithm Parameterization

To assess the performance of the proposed Multi-Objective Sine Cosine Algorithm (MOSCA) framework, two core scenarios are defined. All simulations employ the 33- and 69-bus test systems under radial and meshed topologies, the economic parameters in Table 5, and the daily load profile of Figure 3. The available fixed-step capacitor banks (FSCs) offer discrete reactive power ratings from 100 to 1000 kvar in 100 kvar increments, with their associated investment, installation, and operating costs integrated into the objective function.

- Scenario 1—Base case: Network operation without any capacitor banks, establishing the technical and economic baseline for comparison.

- Scenario 2—Optimal placement of banks: For and 5, the MOSCA determines the optimal locations and discrete sizes of the FSCs. This scenario quantifies the marginal impact of increasing reactive compensation on losses, voltage profiles, and annualized costs.

The MOSCA algorithm is implemented with a population size of 10 candidate solutions per iteration, where each solution encodes a feasible configuration of capacitor locations and discrete sizes. The optimization runs for a maximum of 1000 iterations, with two stopping criteria: (i) reaching the maximum iteration count, or (ii) observing no change in the Pareto front for 50 consecutive iterations. The reactive power per capacitor is constrained to the discrete set {100, 200, …, 1000} kvar. Only solutions that satisfy all network operational constraints are retained and ranked via non-dominated sorting. This parameter set is applied consistently across all network topologies and scenarios.

5.2. Base Case Results

The four base-case configurations of the 33- and 69-bus systems, under both radial and meshed topologies, were simulated without capacitor banks to establish the economic reference for the optimization analysis. Table 6 summarizes the annualized operating cost of each configuration.

Table 6.

Base case results for the 33- and 69-bus systems under radial and meshed configurations.

These values serve as the economic benchmark for assessing the benefits of capacitor-bank installation in the subsequent optimization scenarios.

5.3. Multi-Objective Analysis

The analysis under the hourly load profile Figure 3 confirmed that the methodology behaves robustly under time-varying conditions. The ranking of sensitive nodes and the magnitude of loss reductions remained consistent throughout the daily cycle, demonstrating the suitability of MOSCA for realistic operational environments.

5.3.1. Results in the 33-Bus Grid

The results obtained for the 33-node radial system confirm the theory of reactive power compensation: the installation of capacitor banks achieves a significant reduction in technical losses, although this entails an increase in both investment and operating costs.

In the case without compensation, losses are situated near 470 kUSD/year. With compensation, configurations utilizing capacitor banks reduce losses to approximately 375 kUSD/year, as detailed in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11. The exact magnitude of this reduction is dependent on the number and size of the selected capacitors.

Table 7.

Results for the 33-bus radial topology (1 Bank).

Table 8.

Results for the 33-bus radial topology (2 Banks).

Table 9.

Results for the 33-bus radial topology (3 Banks).

Table 10.

Results for the 33-bus radial topology (4 Banks).

Table 11.

Results for the 33-bus radial topology (5 Banks).

In line with well-established principles of distribution network planning, the results confirm that the energy benefits of reactive power compensation are highly sensitive to device placement. In the analyzed system (33-node), node 30 was consistently identified as a location associated with high loss-reduction potential for capacitor bank installation.

Another relevant aspect is the clear presence of the phenomenon of diminishing marginal returns. The installation of a single capacitor bank leads to a considerable decrease in losses. However, the additional benefit gained by adding more devices tends to decrease progressively.

This is evidenced in Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11: while moving from 1 to 2 banks offers loss reductions exceeding , the addition of 4 or 5 banks results in an attenuated marginal benefit, with reductions stabilizing in the 12–14% range. This trend underscores that simply installing more devices doesn’t always equate to better results, thereby supporting the use of multi-objective optimization to find efficient configurations that avoid over-investment.

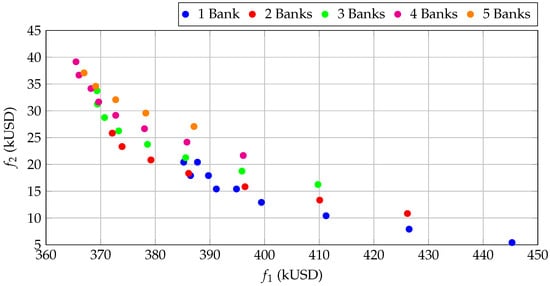

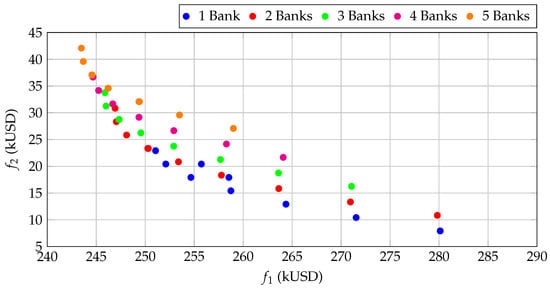

The optimal location of the compensation devices exhibits a clear and consistent trend: nodes such as 30, 14, 13, 32, and 25 repeatedly appear in the best solutions. These points are critical because they are situated far from the slack bus and supply zones with significant loads. This configuration leads to increased currents and, consequently, higher Joule effect losses. The repeated presence of node 30 across almost all Pareto fronts (Figure 4) confirms that it is the most critical node from a power flow perspective, establishing it as the most cost-effective site for installing reactive compensation.

Figure 4.

Optimal Pareto fronts for the 33-bus radial topology.

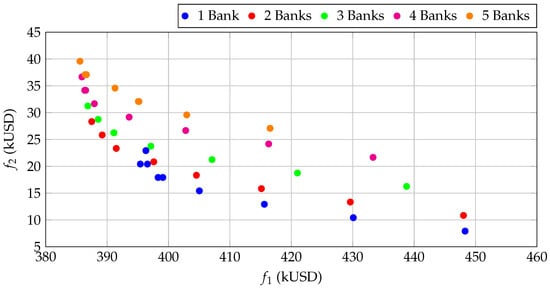

Comparing the results from Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 (radial topology) with those from Table 12, Table 13, Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16 (meshed topology) reveals a significant difference in losses. In the meshed topology, losses are approximately lower (Figure 5 presents the Pareto front for the meshed topology in the 33-bus grid). This improvement stems from the reduction of equivalent impedances and the diversification of power flow paths.

Table 12.

Results for the 33-bus meshed topology (1 Bank).

Table 13.

Results for the 33-bus meshed topology (2 Banks).

Table 14.

Results for the 33-bus meshed topology (3 Banks).

Table 15.

Results for the 33-bus meshed topology (4 Banks).

Table 16.

Results for the 33-bus meshed topology (5 Banks).

Figure 5.

Optimal Pareto fronts for the 33-bus meshed topology.

Consequently, installing capacitors in meshed systems also yields smaller benefits in absolute terms, as the system is already intrinsically more efficient. Nevertheless, node 30 remains the preferred location, emphasizing its structural importance within the network. This analysis confirms that the network architecture directly impacts the benefits of reactive compensation, which are more substantial and relevant in radial systems.

In the different scenarios analyzed, a clear trade-off between the objective functions is observed. Solutions that prioritize (lower losses) tend to utilize larger and more numerous capacitor banks, which inevitably increases (costs). Conversely, solutions that minimize costs reduce the size and quantity of the banks, but allow losses to remain close to baseline values. The Pareto front exhibits a convex behavior, which is typical of problems with strong trade-offs. This confirms that, once a certain investment level is surpassed, the additional loss reduction becomes marginal. This finding is fundamental for decision-making in real-world environments, where the operator must justify the optimal investment level based on this technical–economic balance.

The best practical solutions known as knee points are those configurations where small, additional investments no longer yield significant performance improvements. These solutions are located in the loss ranges of 370–395 kUSD/year, with investment and operation costs ranging between 20–35 kUSD/year.These configurations are particularly attractive for a utility operator because they combine a substantial loss reduction (approximately 12–15%) with moderate investment. The knee point is crucial as it allows for the technical justification of selecting a solution on the Pareto front without incurring unnecessary excess costs.

This behavior clearly highlights the structural difference between radial and meshed networks. In the latter, the existence of multiple current paths reduces the base-case losses by approximately , making the marginal benefit of installing capacitor banks less pronounced. As a consequence, the Pareto fronts of the meshed systems are consistently shifted to lower f1 values, reflecting their intrinsically more efficient operation.

5.3.2. Results in the 69-Bus Grid

The results for the IEEE 69-node system confirm the positive influence of reactive compensation on large and heavily loaded networks. Since this system’s base losses are significantly higher than the 33-node case, it served as an ideal scenario for assessing the real impact of capacitor sizing and placement. Table 17, Table 18, Table 19, Table 20, Table 21, Table 22, Table 23, Table 24, Table 25 and Table 26 demonstrate the effectiveness of the optimization methodology: installing banks at strategic nodes led to loss reductions exceeding in some cases. This validates the method’s capability to find appropriate configurations for long radial systems characterized by multiple load branches.

Table 17.

Results for the 69-bus radial topology (1 Bank).

Table 18.

Results for the 69-bus radial topology (2 Banks).

Table 19.

Results for the 69-bus radial topology (3 Banks).

Table 20.

Results for the 69-bus radial topology (4 Banks).

Table 21.

Results for the 60-bus radial topology (5 Banks).

Table 22.

Results for the 69-bus meshed topology (1 Bank).

Table 23.

Results for the 69-bus meshed topology (2 Banks).

Table 24.

Results for the 69-bus meshed topology (3 Banks).

Table 25.

Results for the 69-bus meshed topology (4 Banks).

Table 26.

Results for the 69-bus meshed topology (5 Banks).

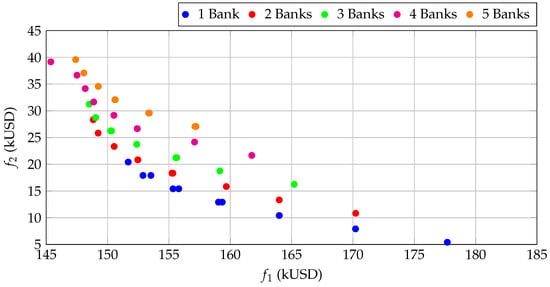

As observed from Table 17, Table 18, Table 19, Table 20 and Table 21, losses are intrinsically higher in the radial network (see the Pareto front in Figure 6). This characteristic allows the placement of capacitors at distant nodes—primarily Node 61—to yield significant reductions of up to . In contrast, the meshed system (observed in the Table 22, Table 23, Table 24, Table 25 and Table 26) exhibits lower initial losses due to the existence of alternative routes for power flow. For this reason, the marginal effect of capacitors is smaller, causing the Pareto Front to shift toward lower values of the objective function (losses), as can be seen in Figure 7. Furthermore, in the meshed network, the need for large compensation capacities decreases, and the predominance of Node 61 is lessened, favoring more diverse configurations with lower investments.

Figure 6.

Optimal Pareto fronts for the 69-bus radial topology.

Figure 7.

Optimal Pareto fronts for the 69-bus meshed topology.

Overall, the meshed topology intrinsically improves system operation, which simplifies the technical–economic trade-off of the problem and reduces the computational effort required by the SCA algorithm to identify efficient solutions.

The results confirm high consistency in optimal placement, similar to the 33-node case. Node 61 is the primary and critical node, appearing in almost all solutions. It is a critical point as it is located at a distant end of the feeder, handles high loads, and experiences considerable currents, making it the site with the strongest direct impact on loss reduction. Nodes 21, 64, 62, and 17 act as secondary nodes, complementing the best multi-bank configurations.

The analysis confirms the phenomenon of diminishing marginal returns when adding more banks. With 1 bank, loss reductions range from to , representing economically attractive solutions, but with still high remaining losses. The use of 2 banks is the knee point, exceeding reduction, with lower total losses and moderate costs (the 61, 21 configuration reaches , offering the best cost-benefit ratio). Finally, adding 3 or more banks yields only a marginal additional gain that does not justify the extra investment. This confirms that two banks represent the most efficient point in technical–economic terms for this network, which is typical for long feeders with extensive laterals.

This front shows a greater dispersion of solution points between losses () and costs (). This variability is a direct consequence of the greater network length, the irregular distribution of loads, and the system’s high sensitivity to the precise placement of compensation devices.

The Pareto Front curve consistently exhibits a convex geometry, a behavior previously observed in the 33-node system. This shape confirms that while initial compensation investments result in significant loss reductions, the additional benefit gained from further investment rapidly becomes marginal. This characteristic is fundamental because it validates that the solutions identified by the algorithm align with the expected physical and economic behavior of the system.

The data clearly allows for the identification of the inflection point (knee point), which indicates the solution that maximizes efficiency. This optimal balance point is located in the loss range of ≈387–399 kUSD/year and costs of ≈20–28 kUSD/year, achieving a total loss reduction of ≈16.3–16.6%. The knee point is of vital practical importance as it offers the solution with the best cost-benefit ratio, allowing the operator to justify the investment without incurring unnecessary overcosts.

The analysis of the optimal solutions on the Pareto Front clearly reveals three distinct investment strategies. The low-cost solutions focus on installing a single capacitor bank (300–500 kvar), typically located at Node 61. Although ideal under tight budgetary constraints, these options offer moderate loss reductions (between and ). Occupying the middle ground are the balance solutions (knee point), which are the most technically and economically efficient. These strategically combine nodes such as 61 and 21 or 61 and 17 to achieve the maximum loss reductions (between and ) with a justifiable investment. Finally, the high-investment solutions include the addition of banks at secondary nodes (such as 64 or 62). These are situated in the flatter region of the Pareto Front, where the cost increase does not translate into a substantial improvement in loss reduction.

6. Discussion and Limitations

The multi-objective MO-SCA algorithm consistently demonstrates its ability to identify efficient reactive power compensation configurations, both in moderate-sized networks (33 nodes) and in more extensive systems (69 nodes). The pattern of solutions is remarkably stable: the SCA converges toward recurrent and technically justifiable nodal locations, which proves the robustness of its exploration-exploitation process.

In the 33-node system, the constant appearance of nodes such as 30, 14, 13, and 32 underscores the SCA’s ability to detect areas where accumulated impedance and demand induce higher losses. The tables confirm the conflicting nature of multi-objective optimization: a progressive reduction in losses () is observed as capacitor capacity or the number of banks increases, although this implies proportional increments in the investment cost ().

Performance remains effective in the 69-node system, where nodes such as 61, 21, 62, and 64 are repeated as optimal solutions, reflecting the SCA’s adaptability to more extensive networks. Loss reductions exceed , even with a single large-sized installation, highlighting the system’s sensitivity to strategically located reactive support. It is relevant that the best configurations tend to concentrate in the final zones of the feeder, aligning with the role of the SCA’s parameter, which controls the transition between broad exploration and refined exploitation in the most promising areas of the search space.

The Pareto Fronts derived from the MO-SCA are continuous and convex curves, confirming that the algorithm generates a variety of physically coherent and well-distributed solutions. The most efficient solutions (with 1 or 2 banks) cluster in the middle region of the front (knee point), while adding more banks shifts the curve toward lower losses, but at the expense of sharper cost increases. This behavior aligns with the SCA’s operating principle, where sinusoidal oscillations facilitate initial broad exploration, and the gradual reduction of the parameter promotes refined exploitation of the best-found solutions. Overall, the results demonstrate that the SCA maintains an adequate balance between population diversity and convergence, enabling efficient exploration of a large number of potential combinations while preserving computational efficiency.

The analysis of the SCA/MO-SCA results in both systems reveals significant limitations related to algorithmic sensitivity and computational cost. The performance of the SCA depends critically on the correct selection of parameters; if the population or the number of iterations are insufficient, the algorithm fails to explore or exploit adequately, potentially leading to a failure in convergence toward optimal solutions. Furthermore, although the SCA finds high-quality solutions, it cannot guarantee the global optimum in large combinatorial spaces (especially when increasing the number of banks), which limits the certainty that the found solutions are the best possible. While the recurrence of critical nodes (such as 30 or 61) is physically coherent, it also suggests a tendency toward intensification that could lead to a loss of diversity and a risk of premature convergence.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presented a multi-objective optimization methodology based on the Sine Cosine Algorithm (MOSCA) for the optimal location and sizing of fixed-step capacitor banks in medium-voltage distribution networks. The proposed approach effectively addresses the mixed-integer, nonlinear, and multi-objective nature of the problem while maintaining algorithmic simplicity and low computational requirements. By balancing technical loss reduction and economic costs, the methodology provides a practical decision-support tool for reactive power compensation planning.

The numerical validation on the IEEE 33- and 69-bus systems, considering both radial and meshed topologies, demonstrated that the proposed approach is robust and consistent under different network configurations and loading conditions. The generated Pareto fronts exhibited good diversity and convergence behavior, allowing network planners to identify compromise solutions with an adequate trade-off between technical performance and investment cost. Moreover, the results highlighted the influence of network topology on the effectiveness of reactive compensation strategies.

Despite these promising results, this study is subject to certain limitations. The analysis was conducted on benchmark distribution systems and relied on deterministic load profiles. Future research will focus on extending the proposed methodology to large-scale and real-world networks, as well as incorporating uncertainty associated with demand variability and distributed generation through robust or stochastic optimization frameworks. Additionally, the integration of dynamic compensation devices and real-time operational constraints represents a relevant direction for further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing (review and editing): L.C.G.-P., B.D.D.-C., O.D.M. and C.A.T.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Thematic Network 723RT0150, i.e., Red para la integración a gran escala de energías renovables en sistemas eléctricos (RIBIERSE-CYTED), funded through the 2022 call for thematic networks of the CYTED (Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development). The third author would like to thank Oficina de Investigaciones at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas for supporting the internal research project with code 33787724, titled “Desarrollo de una metodología de gestión eficiente de potencia reactiva en sistemas de distribución de media tensión empleando modelos de programación no lineal”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of AI-based tools, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT Version 5.1, which supported the refinement of the manuscript’s language, structure, and overall clarity. These tools were utilized exclusively to improve the presentation and readability of the original ideas, formulations, and numerical simulations provided by the authors. Importantly, the AI tools did not contribute to the development of the scientific content, to the formulation, or the validity of the results, for which the authors assume full responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jabr, R.A.; Džafić, I. Sensitivity-Based Discrete Coordinate-Descent for Volt/VAr Control in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 4670–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, M.H.J.; Sannino, A. Voltage control with inverter-based distributed generation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.O.; Kim, E.S.; Moon, S.I. Analysis of the optimal reactive power of distributed generators for improving energy efficiency in distribution networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 52nd International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Heraklion, Greece, 28–31 August 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Kamarposhti, M.; Ghandour, R.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Hafez, M.; Alfiras, M.; Alkhazaleh, S.; Colak, I.; Solyman, A. Optimizing capacitor bank placement in distribution networks using a multi-objective particle swarm optimization approach for energy efficiency and cost reduction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, O.D.; Gil-González, W.; Hernández, J.C. Efficient Integration of Fixed-Step Capacitor Banks and D-STATCOMs in Radial and Meshed Distribution Networks Considering Daily Operation Curves. Energies 2023, 16, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, Z. Improve Distribution System Energy Efficiency with Coordinated Reactive Power Control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha-Feltrin, A.; Rodezno, D.A.Q.; Mantovani, J.R.S. Volt-VAR Multiobjective Optimization to Peak-Load Relief and Energy Efficiency in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2015, 30, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Rivera, J.D.P.; Henao, C.A.O. Efficient Fixed-Step Capacitor Placement Using Random Search Theory. In Proceedings of the IEEE Colombian Caribbean Conference (C3), Santa Marta, Colombia, 17–20 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A Sine Cosine Algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mawgoud, H.; Fathy, A.; Kamel, S. An effective hybrid approach based on arithmetic optimization algorithm and Sine Cosine Algorithm for integrating battery energy storage system into distribution networks. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Sánchez, J.P.; Guerrero-Moreno, J.F. Application of the Sine-Cosine Optimization Algorithm for the Calculation of Loss Coefficients in Transmission Systems. Undergraduate Thesis, Facultad de Ingeniería, Proyecto Curricular de Ingeniería Eléctrica, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K. Multiobjective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms: An Introduction. 2014. Available online: https://www.egr.msu.edu/~kdeb/papers/k2011003.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Premkumar, M.; Hashim, T.J.T.; Ravichandran, S.; Sin, T.C.; Chandran, R.; Alsoud, A.R.; Jangir, P. Optimal operation and control of hybrid power systems with stochastic renewables and FACTS devices: An intelligent multi-objective optimization approach. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 93, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-González, W.; Herrera-Orozco, A.; Molina-Cabrera, A. Stochastic Mixed-Integer Branch Flow Optimization for the Optimal Integration of Fixed-Step Capacitor Banks in Electrical Distribution Grids. Ingeniería 2024, 29, e21340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostovar, F.; Barati, H.; Saeidallah, M.S. Multi-objective Allocation of Distributed Generation Resources and Capacitor Banks Based on a Two-stage Fuzzy Method and E-constrained Optimization. Signal Process. Renew. Energy 2024, 8, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tawhid, M.A.; Savsani, V. Multi-objective sine-cosine algorithm (MO-SCA) for multi-objective engineering design problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2017, 31, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Pan, J.S.; Liu, G.; Fu, M.; Kong, Y.; Hu, P. A Multi-Objective Sine Cosine Algorithm Based on a Competitive Mechanism and Its Application in Engineering Design Problems. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaño, F.E.; Cruz, J.F.; Montoya, O.D.; Chamorro, H.R.; Alvarado-Barrios, L. Reduction of losses and operating costs in distribution networks using a genetic algorithm and mathematical optimization. Electronics 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.E.; Wu, F.F. Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1989, 4, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, C.L.; Torres-Pinzón, C.A. Techno-Economic Assessment of Fixed and Variable Reactive Power Injection Using Thyristor-Switched Capacitors in Distribution Networks. Electricity 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Grisales-Noreña, L.F.; Bolaños, R.I. Optimal Planning and Dynamic Operation of Thyristor-Switched Capacitors in Distribution Networks Using the Atan-Sinc Optimization Algorithm with IPOPT Refinement. Sci 2025, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.