Abstract

Background: Pituitary neuroendocrine tumours (PitNETs) are clinically and biologically heterogeneous neoplasms that remain challenging to diagnose, prognosticate, and treat. Although recent WHO classifications using transcription-factor-based markers have refined pathological categorisation, histopathology alone still fails to predict tumour behaviour or support individualised therapy. Objective: This systematic review aimed to evaluate how machine learning (ML) and knowledge extraction approaches can complement pathology by integrating multi-dimensional omics datasets to generate predictive and clinically meaningful insights in PitNETs. Methods: The review followed the PRISMA 2020 statement for systematic reviews. Searches were conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar, arXiv, and SciSpace up to June 2025 to identify omics studies applying ML or computational data integration in PitNETs. Eligible studies included original research using genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, or liquid biopsy data. Data extraction covered study design, ML methodology, data accessibility, and clinical annotation. Study quality and validation strategies were also assessed. Results: A total of 726 records were identified. After the reviewing process, 98 studies met inclusion criteria. PitNET research employed unsupervised clustering or regularised regression methods reflecting their suitability for high-dimensional omics datasets and the limited sample sizes. In contrast, deep learning approaches were rarely implemented, primarily due to the scarcity of large, clinically annotated cohorts required to train such models effectively. To support future research and model development, we compiled a comprehensive catalogue of all publicly available PitNET omics resources, facilitating reuse, methodological benchmarking, and integrative analyses. Conclusions: Although omics research in PitNETs is increasing, the lack of standardised, clinically annotated datasets remains a major obstacle to the development and deployment of robust predictive models. Coordinated efforts in data sharing and clinical harmonisation are required to unlock its full potential.

1. Introduction

Pituitary neuroendocrine tumours (PitNETs) are among the most common intracranial neoplasms, representing approximately 10–15% of all primary brain tumours [1]. Despite being histologically benign in most cases, their clinical impact is disproportionately significant due to hormone hypersecretion, hypopituitarism, and invasion and mass effect on critical adjacent structures [2]. Patients may present with diverse endocrine syndromes, such as acromegaly, Cushing’s disease, prolactinomas, or the rare but clinically challenging Nelson’s syndrome following bilateral adrenalectomy [3,4,5,6]. The heterogeneity of these tumours poses a major challenge for clinicians: while some PitNETs remain indolent for decades, others display aggressive behaviour with recurrence after surgery or resistance to conventional therapies [7,8].

Over the past few decades, classification systems have attempted to capture this variability. Traditionally, PitNETs were categorised based on histological staining, immunohistochemical detection of pituitary hormones, and ultrastructural features. However, these classifications often failed to correlate with prognosis or were insufficiently informative for guiding medical therapy, since morphologically similar tumours could behave very differently in terms of growth, invasiveness, and recurrence. In recognition of these shortcomings, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised its framework in 2017 and again in 2020 and 2022, incorporating lineage-specific transcription factors and some molecular markers into diagnostic criteria [9,10,11]. Yet, even with these advances, the WHO classifications remain insufficient in the clinical setting. While they have improved diagnostic accuracy, they do not reliably predict patient outcomes. For example, two tumours of the same molecular subtype may respond very differently to surgery, medical therapy, or radiotherapy. Consequently, clinicians continue to face uncertainty in determining prognosis and optimising therapeutic strategies. Thus, while the WHO classifications represent important milestones, the field is now at a crossroads: descriptive taxonomies must evolve into predictive frameworks [12,13].

This gap underscores the urgent need for integrative approaches that combine histopathology with molecular and clinical data. Advances in genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics have already begun to uncover the molecular drivers of PitNET heterogeneity, providing insights into tumour biology that are not apparent from histology alone [14]. However, these rich datasets remain underutilised in daily clinical practice. Their full potential lies in systematic integration, validation, and clinical interpretation, moving from descriptive findings towards actionable biomarkers.

At the same time, the amount of data generated through high-throughput current multiomic techniques requires computational methods capable of a comprehensive and robust analysis and interpretation extracting clinically meaningful patterns [15]. Machine learning (ML) and AI-based knowledge extraction techniques are uniquely positioned to address this challenge, enabling the discovery of complex signatures across omics layers and their correlation with clinical outcomes. By bridging the gap between large-scale data and patient-level decision-making, ML approaches may ultimately support faster diagnosis, better risk stratification, and more personalised treatment strategies in this very heterogeneous group of tumours [16,17].

This hybrid review will explore the current landscape of ML and knowledge extraction in PitNETs, with a particular focus on omics data, available resources, and the potential for integrative approaches to transform clinical practice in personalised therapy and categorise these datasets according to their accessibility and feasible utilisation for real integrative analyses. The primary motivation for this review is to systematically map and critically evaluate the current landscape of publicly available PitNET omics datasets. By providing a comprehensive overview, this review aims to identify the key limitations that currently hinder the effective clinical translation of these resources, including issues related to data accessibility, annotation, and the methodological rigor in ML applications. Furthermore, this work seeks to highlight promising opportunities for leveraging advanced machine learning techniques and integrative omics approaches, with the ultimate goal of advancing precision medicine in PitNETs. Through this critical assessment, we intend to support the development of robust predictive frameworks and facilitate future research that bridges the gap between large-scale data generation and actionable clinical insights.

2. Materials and Methods

Portions of this manuscript were linguistically refined with the assistance of a generative AI tool (ChatGPT; OpenAI, GPT-5.1 model). The tool was used exclusively to support the organisation and linguistic editing of the text. All scientific content, interpretations, and conclusions were determined by the authors, who independently verified and edited the generated material.

2.1. Articles Search

We performed a systematic review of -omics studies in PitNETs (Registered in PROSPERO: CRD420251139992). Briefly, the primary search was performed in PubMed (Advanced Search) using the following query: (pituitary adenoma OR pituitary neuroendocrine tumor OR PitNET OR somatotropinoma OR corticotroph OR prolactinoma OR TSHoma OR acromegaly OR “Cushing’s disease” OR “null cell adenoma” OR “plurihormonal adenoma”) AND (genomics OR epigenomics OR transcriptomics OR proteomics OR “whole genome sequencing” OR “whole exome sequencing” OR GWAS OR “RNA sequencing” OR “single cell” OR “DNA methylation” OR “bisulfite sequencing” OR “mass spectrometry” OR omics).

Complementary searches were carried out in Google Scholar, SciSpace, and arXiv using adapted queries to maximise sensitivity. Example queries included the following:

- (pituitary adenoma OR somatotropinoma OR prolactinoma OR corticotroph OR corticotropinoma OR acromegaly OR “Cushing’s disease”) AND (genomics OR transcriptomics OR epigenomics OR proteomics OR “whole genome” OR “RNA-seq” OR “DNA methylation” OR omics);

- omics studies in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, somatotropinoma, prolactinoma, corticotroph adenoma, acromegaly, Cushing’s disease;

- all:pituitary AND (all:omics OR all:genomics OR all:transcriptomics OR all:proteomics OR all:adenoma).

In addition, focused searches targeting specific PitNET subtypes and omics approaches were conducted in PubMed, for example,

- (somatotropinoma OR “GH-secreting adenoma” OR acromegaly) AND (transcriptomics OR “RNA sequencing” OR “single cell RNA-seq” OR “bulk RNA-seq” OR “gene expression profiling”);

- (prolactinoma OR “PRL-secreting adenoma”) AND (proteomics OR “mass spectrometry” OR “protein expression” OR “proteomic profiling”);

- (corticotroph tumor OR “ACTH-secreting adenoma” OR “corticotropinoma” OR “Cushing’s disease”) AND (epigenomics OR “DNA methylation” OR “bisulfite sequencing”).

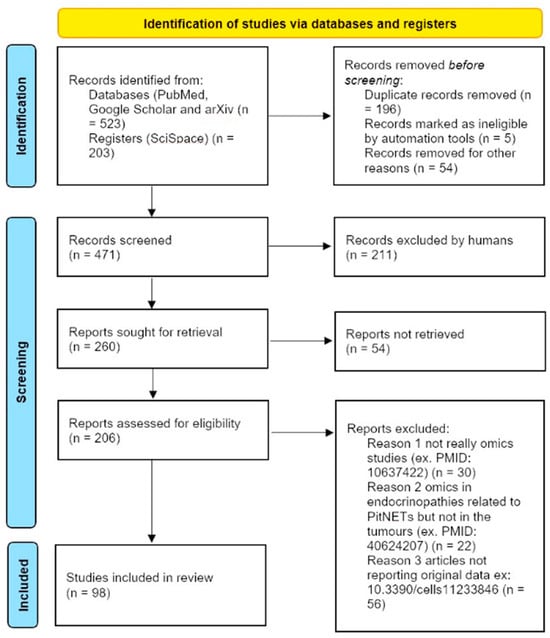

Citation chasing and reference screening were also performed to identify additional relevant studies not retrieved by the primary queries. To facilitate and standardise the search process across databases, automated queries were executed manually and using SciSpace (SciSpace Research). More details are available in PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251139992 accessed on 8 December 2025). The review process is illustrated in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram). The review followed the PRISMA 2020 statement for systematic reviews.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews. Modified from: Page MJ et al. [18]. This slow diagram exemplifies how the papers were selected through the review process.

To facilitate comparison of available resources, all identified studies were classified according to the accessibility and clinical utility of their data. Four categories were defined. Studies coded in red correspond to datasets that are not accessible to the scientific community (RED), either because raw data were not deposited or access is explicitly restricted. Studies marked in orange denote cases where data are only partially available or require contacting the corresponding author, with limited reproducibility potential (ORANGE). Studies coded in green represent datasets in public repositories, providing open access to molecular data but without sufficient clinical annotations beyond basic descriptors such as age, sex, or histological subtype (GREEN). Finally, studies highlighted in blue constitute the highest-value resources, combining deposition in open-access repositories with relatively recent technology platforms and clinically meaningful annotations extending beyond routine histology, thereby enabling linkage between molecular features and patient outcomes (BLUE). These criteria ensured a systematic and transparent evaluation of the real-world utility of each dataset for secondary analysis and clinical validation.

Moreover, to facilitate access to the datasets identified in this review, we provide the corresponding repository URLs in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Datasets hosted in major international repositories such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), ArrayExpress, and the European Genome–Phenome Archive (EGA) are typically available through direct download, without requiring user credentials or prior authorisation. In contrast, several resources generated in Asian research programs, particularly those deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC), require user registration before access is granted. In some instances, users must submit a formal access request, which is routinely approved after institutional verification.

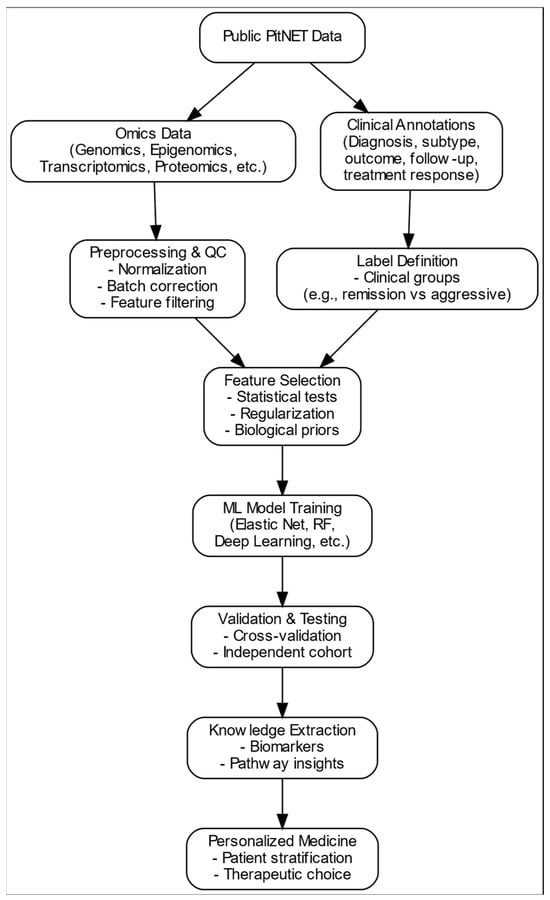

2.2. Machine Learning Pipeline

To facilitate comprehension of the data-driven approach underpinning this review, we provide a schematic overview of the analytical workflow applied in PitNET research (Figure 2). As illustrated, publicly available omics datasets and clinical annotations follow distinct but complementary processing streams. Omics data require extensive preprocessing and quality control, whereas clinical information is used to define outcome labels. Both streams converge during feature selection, which integrates molecular features with clinically relevant endpoints. The selected variables are subsequently used for ML model training, validation, and knowledge extraction, ultimately enabling patient stratification and supporting personalised therapeutic decisions. This framework reflects the logical sequence of steps encountered across the studies reviewed and serves as a conceptual reference for interpreting the examples and methodological discussions presented in later sections.

Figure 2.

Overview of the data-driven framework for personalised medicine PitNETs. Publicly available omics datasets undergo preprocessing and quality control, whereas clinical annotations define patient labels. Both streams converge during feature selection, after which ML models are trained, validated, and interpreted to extract biological knowledge that may support patient stratification and therapeutic choices.

2.3. Machine Learning Example

Illumina methylation array data (.idat files) were obtained from the EMBL-EBI ArrayExpress repository (accession number E-MTAB-7762) and processed using R version 4.5.1. R Project for Statistical Computing, RRID: SCR_001905). After quality control and normalisation with the RnBeads package (RRID:SCR_010958), beta values were extracted and harmonised with clinical annotations. Tumours were grouped according to clinical behaviour and dichotomised into a low-risk (remission) and high-risk (aggressive or resistant) category.

To construct a predictive model, we first performed differential methylation analysis using limma (RRID:SCR_010943) to reduce dimensionality and retain the most informative CpGs. These features (FDR-corrected p-values < 0.25) were subsequently used to train an elastic net classifier implemented via the glmnet package (RRID:SCR_015505). Hyperparameters α (mixing parameter) and λ (penalisation) were optimised through repeated stratified 10-fold cross-validation within the caret framework (RRID:SCR_021138) to prevent model overfitting. The model training process was iteratively repeated with different random seeds and resampling folds until convergence was reached, consistently selecting the same subset of CpGs and yielding comparable performance metrics. Final performance was evaluated in an independent test set using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (pROC R package, Version 1.19.0.1, RRID:SCR_024286), AUC values, confusion matrices, and class-specific metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity). Data visualisation was performed using pheatmap (RRID:SCR_016418) to explore methylation patterns across predicted subgroups.

3. Machine Learning in PitNETs: Why?

Despite decades of refinements, the diagnosis of PitNETs remains heavily reliant on pathological examination. Hematoxylin–eosin staining, immunohistochemistry for pituitary hormones, and more recently transcription factors form the backbone of routine diagnostic practice. While these tools have undoubtedly improved the ability to categorise tumours according to lineage, their role in guiding clinical management remains limited.

One of the main challenges is the subjectivity inherent to pathological evaluation. Even with standardised immunohistochemical panels, inter-observer variability persists and the interpretation of staining intensity or cellular morphology often depends on individual expertise [19]. However, the more fundamental limitation lies in the restricted discriminative power of histology itself: tumours that appear virtually identical under the microscope may nonetheless diverge dramatically in their clinical course, due to differences in molecular factors or tumour microenvironment [13]. From the clinician’s perspective, pathological reports provide descriptive information but rarely answer the most pressing questions: Will this tumour recur? Will the patient benefit from a specific medical therapy? Should we anticipate aggressive behaviour?

A further limitation lies in the difficulty of achieving a truly clear diagnostic definition of tumour subtype and linking this to prognosis and therapeutic implications, which is a challenge increasingly recognised as a theragnostic gap [20]. For instance, corticotroph tumours may present as Cushing’s disease or remain clinically silent, with pathology alone offering little predictive value [21]. Similarly, lactotroph or somatotroph tumours can differ markedly in treatment response, despite identical staining profiles [22]. This diagnostic uncertainty is further compounded by the frequent delay and complexity in recognising endocrine syndromes such as acromegaly or Cushing’s disease. Both conditions are often diagnosed late, after years of nonspecific symptoms, at which point significant comorbidities may have developed [23]. A purely pathological classification, as currently formulated, does little to address this critical gap, leaving patients without timely and effective personalised interventions.

Although several studies have explored digitalised automated immunohistochemical scoring of markers such as SSTR2 or E-cadherin as potential correlates of treatment outcome, these approaches are only the beginning of personalised medicine. There is increasing scientific efforts towards predictive medicine [24,25,26]; however, this disconnection between the current histological description and clinical needs highlights the need to move forward in obtaining and implementing complementary tools capturing tumour heterogeneity beyond strict morphological reports. In practice, clinicians still lack reliable means to personalise treatment or anticipate recurrence based solely on current pathological reports.

This persistent gap provides the rationale for adopting omics-based profiling and, by extension, ML approaches capable of integrating multi-dimensional data. While pathology remains largely descriptive, though gradually incorporating molecular techniques, and is still mostly subject to human interpretation despite the increasing use of digitalisation, computational models offer the possibility of objective, reproducible, and predictive frameworks. By leveraging genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics together with clinical variables, such approaches could transform PitNET classification from a retrospective exercise into a forward-looking tool that informs on prognosis and treatment selection. However, when integrated with multiomic datasets, digital pathology may further enhance predictive modelling, contributing to more accurate stratification and individualised management of PitNETs [27].

4. Machine Learning in PitNETs: How?

While the rationale for applying ML to PitNETs is clear, the methodological landscape remains heterogeneous and, at times, problematic, reflecting both the diversity of available data and the relative scarcity of large, well-annotated cohorts. Approaches can broadly be divided into classical statistical learning methods, modern supervised and unsupervised algorithms, and emerging integrative models that combine omics and clinical information [28].

4.1. Classical Machine Learning Approaches

Early applications of ML to PitNETs focused on regularised regression techniques, such as LASSO or elastic net, which are particularly suited for high-dimensional omics datasets with relatively small sample sizes. These methods are valuable not only for prediction but also for feature selection, highlighting the molecular or clinical variables most strongly associated with tumour subtype, recurrence, or treatment response. Other approaches, including logistic regression, decision trees, and support vector machines (SVMs), have been employed in small studies to classify functional versus non-functional tumours or to predict invasive behaviour [29,30,31]. Classical ML approaches are being increasingly applied in modern clinical research, for example, to predict postoperative outcomes using logistic regression with elastic net regularisation (LR-EN) [32].

4.2. Supervised Learning with High-Dimensional Data

Supervised learning remains the dominant paradigm, especially in imaging and genomics. Algorithms such as random forests, gradient boosting machines, and deep neural networks have been used to predict clinical outcomes or classify tumour subtypes [33,34,35,36]. In imaging, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) show promise in distinguishing tumour margins or correlating radiological features with endocrine function. For example, ML has been used to identify occult acromegaly by analysing facial photographs, detecting subtle changes associated with excess growth hormone years before the clinical diagnosis [37]. In transcriptomic and methylation studies, supervised learning enables the identification of molecular signatures that may stratify patients beyond traditional histology. Importantly, these models can be benchmarked against clinical variables to assess whether molecular profiles provide added predictive value [38].

4.3. Unsupervised Learning for Subgroup Discovery

Given the heterogeneity of PitNETs, unsupervised methods such as hierarchical clustering, k-means, or principal component analysis (PCA) have played an essential role in subtype discovery [39,40,41]. These approaches allow the data to identify novel clusters of patients with shared molecular features [42,43,44]. Although unsupervised approaches are inherently exploratory, they generate hypotheses for clinically meaningful stratification that can subsequently be tested and validated using supervised methods.

4.4. Integrative and Multimodal Models

A major challenge in PitNETs is the integration of diverse data sources: histology, imaging, endocrine profiles, and multiple layers of omics. Emerging methods such as multiomics factor analysis, similarity network fusion, and ensemble learning frameworks (MOFA and DeepMoIC, for example) allow for the combination of heterogeneous data into a single predictive model [45,46,47]. These integrative approaches are particularly relevant for PitNETs, where neither pathology nor single-layer omics provide sufficient resolution to guide treatment alone. By blending data modalities, these models may capture the full biological and clinical heterogeneity of PitNETs.

4.5. Knowledge Extraction and Explainability

A recurring concern in the clinical adoption of ML is the “black-box” nature of many algorithms. In PitNETs, interpretability is not optional but essential, since clinical decisions must be justified to both physicians and patients. Feature importance metrics, SHAPs (Shapley additive explanations), and LIMEs (local interpretable model-agnostic explanations) are increasingly applied to provide transparency in ML-driven predictions [48]. For example, if a classifier predicts risk of recurrence, clinicians must know which molecular or imaging features drive this prediction to trust and apply the result into clinical practice.

4.6. Advantages and Disadvantage of Machine Learning Approaches in PitNETs

Although machine learning methodologies applicable to biomedical research are extensive, their implementation in PitNETs remains comparatively scarce, largely due to the limited availability of datasets in this rare disease. Classical regularised regression models such as LASSO or elastic net are particularly suited to PitNET omics studies because they tolerate high dimensionality and small cohorts while providing interpretable features that support biologically grounded hypothesis generation. Nevertheless, their linear assumptions may overlook nonlinear regulatory interactions relevant to tumour heterogeneity.

Tree-based ensemble methods, including random forests and gradient boosting, help to address these nonlinearities and have shown potential in predicting treatment outcomes or tumour aggressiveness [38]. However, their reduced interpretability and susceptibility to overfitting remain important barriers when sample sizes are limited, which is a frequent constraint in PitNET research.

Deep learning approaches, especially convolutional architectures, have recently been explored in imaging-based PitNET applications. While powerful in theory, they require large harmonised cohorts that are not yet available for most PitNET subtypes. Moreover, their black-box nature continues to raise concerns regarding clinical traceability and acceptance.

Unsupervised learning has historically been the most frequently applied paradigm in PitNET studies. Techniques such as hierarchical clustering, PCA, or more recently UMAP, have enabled subclassification of tumours based on clinical and molecular profiles, offering insights into disease mechanisms and phenotypic variability [39]. Despite their usefulness, these approaches remain exploratory and have never undergone proper validation to support clinical decision-making.

In contrast, integrative multiomics frameworks designed to combine genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and clinical layers have not yet been applied to PitNETs. Given the biological complexity of these tumours, we propose that such approaches represent a promising next step to generate clinically actionable models and move beyond descriptive classification towards predictive personalised medicine.

These methodological choices inherently address the challenge of small sample sizes in PitNET studies, as regularisation techniques, dimensionality reduction, and resampling-based validation strategies are specifically designed to enable reliable model training in high-dimensional datasets where cohort size is limited.

In summary, while a broad methodological landscape exists, the lack of large, standardised, and clinically annotated PitNET datasets limits the full exploitation of advanced ML paradigms. Future progress will likely depend on hybrid strategies that balance interpretability, multi-modal integration, and robust validation to support clinical translation.

4.7. Current Limitations

Despite these methodological advances, progress is slowed by small cohort sizes, variability in data quality, and a lack of standardised pipelines. Many published models remain proof-of-concept rather than clinically validated tools [38]. While validation can be performed internally using different procedures inherent to the ML system itself, it is highly recommended to also use independent external cohorts with similar phenotypic characteristics. Thus, reproducibility is a major challenge and requirement, where models trained in one centre often fail to generalise to external datasets, reflecting the need for multicentre collaborations and harmonised data collection for exploring, e.g., ethnicity specificities and even environmental modulators.

In this context, existing initiatives such as ERCUSYN—which has already collected harmonised clinical data across European centres—represent a valuable foundation for scaling up [49]. Leveraging such infrastructures to incorporate omics data layers (genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, etc.) would enable the development of more robust, generalisable machine learning models. This would mark a critical step forward, integrating molecular signatures with clinical phenotypes in a reproducible and scalable way.

The REMAH project was also an important early step in this direction in the Spanish context, establishing a biobank that linked clinical data with molecular profiles. However, its molecular scope was limited to a predefined gene panel [50]. To fully realise the potential of precision medicine, future efforts must move beyond targeted panels and embrace comprehensive high-throughput omics profiling. This shift would allow for the discovery of novel biomarkers and the development of predictive models that reflect the full biological complexity of PitNETs and their interpretability.

Ultimately, without the support of large-scale national or supranational consortia, it will be difficult to generate the volume and diversity of data required to train clinically useful ML models. Precision medicine in PitNETs will only be achievable through coordinated, well-funded multicentric efforts that combine clinical expertise, molecular science, and advanced computational methods.

Beyond technical and infrastructural challenges, significant barriers to the adoption of ML in clinical practice arise from ethical and regulatory considerations. Algorithmic bias, often stemming from unbalanced, biased, or non-representative training datasets, can exacerbate existing health disparities if not properly addressed. Regulatory frameworks such as the GDPR in Europe and FDA guidance in the U.S. are beginning to tackle these issues, but gaps remain in ensuring fairness, explainability, and legal clarity [51]. Without robust governance mechanisms and ethical oversight, the deployment of ML in healthcare risks undermining trust and widening inequities rather than advancing precision medicine.

5. Machine Learning in PitNETs: Where?

Although there are current limitations in data availability, standardisation, and model generalisability, a significant number of datasets are already available that offer valuable opportunities for validation and exploratory ML studies. Although often underutilised, these resources can serve as a foundation for developing and benchmarking predictive models across different research groups worldwide. Some consist of well-characterised clinical cohorts, while others incorporate molecular multiomics data.

In the tables below, we summarise the main omics-based studies conducted to date in PitNETs. Datasets are organised by omics indicating sample size and public availability of data. Because most omics datasets lack matched clinical outcomes, their utility remains limited to exploratory analyses rather than predictive modelling.

5.1. Transcriptomics

A total of 56 transcriptomics studies were reviewed (Table 1). Among these, 29 studies (51%) provided accessible data repositories. However, the associated clinical data were limited and focused mainly on invasion and aggressive behaviour; no longitudinal clinical data were provided.

Table 1.

Transcriptomic studies in PitNETs.

Table 1.

Transcriptomic studies in PitNETs.

| PMID | Reference | Sample Size | Technology | Main Conclusion | Data Sharing | Data Repository |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15994756 | [52] | 5 PitNET subtypes; 5 normal pituitaries | Expression array | Subtype-specific expression patterns | GREEN | GSE2175 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE2175 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 16288009 | [53] | 11 NFPTs; 8 normal pituitaries | Expression array | Distinct expression patterns in NFPTs | RED | NA |

| 18183490 | [54] | 6 prolactinomas; 8 normal pituitaries | Expression array | Distinct expression patterns in prolactinomas | RED | NA |

| 20228124 | [55] | 40 NFPTs | Expression array | MYO5A overexpression marks invasiveness in NFPTs | ORANGE | E-TABM-899 (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/fire/E-TABM-/899/E-TABM-899/ accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 21251114 | [56] | 13 prolactinomas | Expression array | Chromosome 11 allelic loss drives aggressive and malignant PRL tumours, highlighting candidate genes as progression markers | GREEN | GSE22812 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE22812 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 21810943 | [57] | 14 gonadotroph tumours; 9 normal pituitaries | Expression array | GADD45β suppresses gonadotroph pituitary tumour growth and survival | GREEN | GSE26966 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE26966 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 22635680 | [58] | 4 prolactinomas | Expression array | Characterisation of genes changes induced by oestrogen | GREEN | GSE36314 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE36314 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 26322309 | [59] | 12 prolactinomas | miRNA expression array | miR-183 suppresses proliferation in aggressive prolactinomas | GREEN | GSE46294 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE46294 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 30397197 | [60] | 5 prolactinomas; 4 normal pituitaries | Expression array | H19 inhibits pituitary tumour growth by blocking mTORC1-mediated 4E-BP1 phosphorylation | GREEN | GSE119063 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE119063 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 30504132 | [61] | 35 NFPTs; 7 normal pituitaries | Expression array | MYC, E2F1, CEBPD, and Sp1 drive human and rat prolactinomas | GREEN | GSE77517 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE77517 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 30867568 | [62] | 10 NFPTs; 5 normal pituitaries | Expression array | The invasive phenotype of AIP-mutant tumours is driven by their microenvironment | GREEN | GSE63357 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE63357 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 31883967 | [40] | 134 patients (35 corticotroph, 29 gonadotroph, 23 somatotroph, 16 lactotroph, 8 GH-PRL, 8 null-cell, 6 thyrotroph, 9 plurihormonal PIT1+) | Bulk RNAseq (mRNA and miRNA) | Reference multiomics dataset | BLUE | EGAS00001003642 (https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS00001003642); E-MTAB-7969 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-7969); E-MTAB-7768 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-7768) accessed on 8 December 2025 |

| 33168091 | [63] | 32 lactotroph tumours | Expression array | Genome instability in PitNETs varies by subtype, with high CNVs in lactotroph tumours predicting recurrence | GREEN | GSE120350 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE120350 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 33205234 | [64] | 8 NFPTs | Expression array | Aberrant CNVs, dysregulated DNA methylation, and gene expressions in high-proliferative NFPTs | RED | NA |

| 33472171 | [65] | 172 PitNETs (31 somatotroph, 17 lactotroph, 79 gonadotroph; 45 corticotroph tumours) | Bulk RNAseq | DLK1/MEG3 locus regulates PitNET differentiation, especially in somatotrophs, linking imprinting disorders to tumour behaviours and therapeutic potential | RED | NA |

| 33472173 | [66] | 76 patients. Tumour DNA (28 prolactinomas, 11 somatotropinomas, 37 NFPT) | Expression array | Genomic CNVs, especially in PRL-PAs, drive transcriptomic changes, prolactin overproduction, drug resistance, and tumour progression via amplified genes like BCAT1 | RED | NA |

| 33908609 | [67] | scRNA-seq: “21 PitNETs (6 somatotroph, 5 ACTH, 7 gonadotroph, 2 PIT1+ PPA, 1 lactotroph, and 1 PAwUIC).”; bulk RNAseq: “16 PitNETs (5 somatotroph, 5 gonadotroph, 3 ACTH, 1 prolactinoma, 2 null cell).” | Bulk RNAseq and scRNAseq | Single-cell multiomics revealed PitNET subtype heterogeneity and novel tumour-related genes with potential as biomarkers and targets | GREEN | PRJCA002946 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA002946 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 33986766 | [68] | 73 NFPTs | Bulk RNAseq | Microenvironment-related genes in NFPTs were linked to invasion and recurrence, with 5 key genes showing prognostic and therapeutic potential | GREEN | GSE169498 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE169498 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 34758873 | [69] | 51 PitNETs (14 gonadotroph, 13 corticotroph, 18 somatotroph, 2 somato-lactotroph, 4 lactotroph, 1 thyrotroph, 4 plurihormonal, 1 gonadotroph, 2 null cell) | Bulk RNAseq | PitNETs can be grouped into three molecular subtypes aligned with key transcription factors, revealing new potential tumour-driving genes | ORANGE | NA |

| 35218667 | [70] | 180 PitNETs (38 lactotropinomas, 24 somatotropinomas, 2 mixed GH–PRL, 2 thyrotropinomas, 3 plurihormonal, 40 corticotropinomas, 71 gonadotropinomass, 5 null cell) | Bulk RNAseq | TRIM65-mediated ubiquitination of TPIT inhibited POMC transcription and ACTH production | GREEN | OEP00001353 (https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP00001353 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 35372359 | [71] | 22 NFPTs | Bulk RNAseq | Weighted coexpression network analysis identified the stiffness-related module | GREEN | HRA000954 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA000954 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36001971 | [72] | 34 PitNETs (25 corticotropinomas, 3 NFPTs, 3 somatotropinomas, 3 prolactinomas) | Bulk RNAseq and scRNAseq | Corticotropinomas evade apoptosis via noxa deregulation | RED | NA |

| 36307579 | [73] | 200 PitNETs (101 PIT1-lineage including 21 GH, 23 PRL, 15 TSH, 22 silent PIT1, and 20 plurihormonal; 46 TPIT-lineage including 21 ACTH and 25 silent TPIT; 31 SF1-lineage including 12 gonadotroph, 19 silent SF1, 22 null cell tumours) | Bulk RNAseq | Integrative proteogenomic analysis of 200 PitNETs revealed molecular subtypes, therapeutic targets, and immune pathways, refining classification and guiding potential targeted and immunotherapies | GREEN | OEP003433 (https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP003433 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36359740 | [74] | 12 pituitary organoid (12 functional corticotroph (CD), 3 silent corticotroph, 9 gonadotroph, 8 lactotroph, 3 somatotroph tumours) | scRNAseq | Tumour organoids represent a novel approach in modelling Cushing’s syndrome | RED | NA |

| 36435867 | [75] | 60 somatotropinomas; 45 NFPTs | Bulk RNAseq | GNAS mutations drive somatotroph PitNETs and influence acromegaly features and treatment response via GPCR pathways | BLUE | GSE213527 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE213527 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36504388 | [76] | 65 PitNETs (15 somatotroph, 7 corticotroph, 43 NFPTs) | Bulk RNAseq | Transcriptome profiling reflects their methylome signature | BLUE | GSE209903 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE209903 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36754052 | [77] | 21 PitNETs (3 prolactinomas, 5 somatotroph, 2 mammosomatotroph GH + PRL, 2 thyrotroph, 7 nonfunctioning, and 2 corticotroph) | scRNAseq | Single-cell analysis defined PitNET differentiation states, proposing a new classification that predicts recurrence risk across lineages | GREEN | PRJCA009690 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA009690 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36774501 | [78] | 41 somatotropinomas, 61 NFPT, 37 pituispheres, 9 GH3 cells | Bulk RNAseq | Transcriptomic analysis of GH-producing PitNETs treated with SRLs revealed pathway alterations and treatment effects | BLUE | GSE200175 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200175 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 37418134 | [79] | 210 PitNETs and 8 normal pituitaries | Bulk RNAseq | PIT1-lineage PitNETs show enriched M2 macrophages and PD-L1 expression, linking their immune profile to aggressiveness and suggesting targets for immunotherapy | RED | NA |

| 37662403 | [80] | 7 corticotropinomas | scRNAseq | Spatial transcriptomics of corticotroph tumours uncovered intratumor heterogeneity with therapeutic relevance | ORANGE | NA |

| 37699356 | [81] | 48 somatotropinomas | Bulk RNAseq | NR5A1 and GIPR expression linked to specific methylation patterns | RED | NA |

| 38167466 | [82] | 24 PitNETs and 2 normal pituitaries (6 somatotroph, 3 mammosomatotroph, 3 prolactinomas, 1 mixed somatotroph–lactotroph, 6 corticotroph, 4 gonadotroph, 3 null cell, and 1 thyrotroph) | scRNAseq | Single-cell analysis revealed PitNET heterogeneity, immune features, and a novel aggressive cell subpopulation driven by PBK | GREEN | HRA003483 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA003483 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 38290248 | [83] | 32 PitNETs | Bulk RNAseq | Downregulation of HSPD1 was identified as a key marker linked to mitophagy, tumour invasion, and immune regulation, serving as a predictive indicator of invasive pituitary adenomas | RED | NA |

| 38330165 | [84] | 146 somatotropinomas | Bulk RNAseq | KDM1A haploinsufficiency caused GIPR expression | RED | NA |

| 38505563 | [85] | 77 PitNETs (29 gonadotroph, 19 corticotroph, 22 somatotroph, 3 somato-lactotroph, 4 prolactinomas, 1 thyrotroph, 4 plurihormonal, 1 gonadotroph, 2 null cell) | Bulk RNAseq | Molecular differences in invasive and non-invasive PitNETs | RED | NA |

| 38637883 | [86] | 6 normal pituitaries and 9 PitNETs | Bulk RNAseq | HDAC inhibitors, especially panobinostat, alone or combined with Nrf2 inhibitor ML385, show strong potential for PitNET treatment | GREEN | OEP001353 (https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP001353 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 38643763 | [87] | 5 prolactinomas; 3 normal pituitaries | Bulk RNAseq | Transcriptomic profiling of lactotroph PitNETs revealed distinct gene expression, activated signalling pathways, and key upstream regulators that may serve as therapeutic targets | ORANGE | Partially in the article |

| 38656317 | [88] | 32 patients tumour and organoid DNA (7 gonadotropinomas, 1 lactotroph, 4 plurihormonals, 8 corticotropinomas, 4 somatotropinomas, 1 null cell, 7 NA) | Bulk RNAseq | Pituitary derived organoids retain features of parental tumours, indicating a translational significance in personalised treatment | ORANGE | NA |

| 38658971 | [89] | Bulk: 433 PitNETs (137 lactotroph, 76 somatotroph, 171 gonadotroph, 47 corticotroph, 1 thyrotroph, 19 plurihormonals, 14 null cell tumours); Single cell: 24 PitNETs (9 lactotroph, 7 gonadotroph, 3 plurihormonal-multihormone, 3 plurihormonal PIT-1, 1 somatotroph, 1 corticotroph) | Bulk RNAseq and scRNAseq | Single-cell and spatial analyses revealed distinct PitNET immune microenvironments, with TAM–tumour interactions via INHBA-ACVR1B regulating apoptosis and offering therapeutic targets | GREEN | HRA005096 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA005096 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 38769659 | [90] | 1 somatotropinoma; 2 normal tissues | Bulk RNAseq | Enhanced insulation boundary and a greater number of loops in the TCF7L2 gene region within tumours, accompanied by an expression upregulation | ORANGE | NA |

| 38790160 | [91] | 42 PitNETs (14 gonadotroph NFPT, 3 null cell NFPT, 3 silent corticotroph, 10 GH-secreting, 6 ACTH-secreting, 4 TSH-secreting, 2 prolactinomas) | Expression array | Lineage-specific immune gene expression and immune cell infiltration | GREEN | GSE147786 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE147786 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 38989697 | [92] | 14 PitNETs (11 corticotroph, 2 gonadotroph, 1 plurihormonal, 1 thyrotroph tumour) | Bulk RNAseq | HTR2B is a potential therapeutic target for NFPTs, and its inhibition could improve CAB efficacy | GREEN | HRA005096 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA005096 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39139281 | [93] | 20 somatotropinomas; 6 normal pituitaries | Bulk RNAseq | Sparsely granulated somatotropinomas showed enhancement in JAK–STAT, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and MAPK signalling | RED | NA |

| 39217365 | [94] | 11 patients tumour DNA (8 non-functioning gonadotropinomas, 1 corticotropinoma, 1 somatotropinoma, 1 metastatic corticotropinoma) | Bulk RNAseq | Pituitary tumorigenesis could be driven by transcriptomically heterogeneous clones | ORANGE | NA |

| 39361240 | [95] | 20 somatotropinomas; 6 normal pituitaries | Bulk RNAseq | Spliceosome provides novel insights into GH-secreting tumour pathogenesis | RED | NA |

| 39363281 | [96] | 117 PitNETs | Bulk RNAseq | They identified three molecular subtypes with distinct signalling, metabolic, and immune profiles, correlating with clinical features and prognosis | RED | NA |

| 39548496 | [97] | 7 gonadotropinomas and 3 prolactinomas | scRNAseq | Proliferative lymphocytes, CD8+ T, and NK cells could represent potentially valuable targets in PitNETs | GREEN | GSE244101 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE244101 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39548559 | [98] | 18 somatotropinomas and 6 normal pituitaries | Spatial transcriptomics and scRNAseq | Spatial transcriptomics and single-cell analysis revealed somatotroph PitNET heterogeneity and identified DLK1, RCN1, and TGF-β signaling as key drivers of progression | GREEN | HRA007285 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA007285 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39596626 | [99] | 5 somatotropinomas | LCM-RNAseq | LCM-RNAseq could unlock hidden molecular diversity | ORANGE | NA |

| 39784532 | [100] | 10 somatotropinomas | Spatial transcriptomics and scRNAseq | Somatotropinomas presented rich heterogeneity and diverse cell subtypes | GREEN | PRJNA1137596 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1137596 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39865310 | [101] | 14 PitNETs (11 corticotroph, 2 gonadotroph, 1 plurihormonal, and 1 thyrotroph tumour) | scRNAseq | Study shows that TNF-α+ TAMs drive bone invasion in PitNETs | GREEN | HRA008285 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA008285 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39934142 | [102] | 209 samples bulk RNAseq: (205 PitNETs and 4 normal pituitaries), 77 somatotropinomas, 27 prolactinomas, 56 corticotropinomas, 7 thyrotropinomas, 80 gonadotropinomas, and 3 null cell PitNET. 16 sc-RNAseq: 2 normal pituitaries, 4 somatotropinomas, 2 tiropropinomas, 2 gonadotropinomas, 2 corticotropinomas, 1 plurihormonal, 1 null cell | Bulk RNAseq and scRNAseq | Enhancing the understanding of the PitNET subtyping | ORANGE | HRA006929 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA006929 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 40002253 | [103] | 21 corticotropinomas; 7 normal pituitaries | Bulk RNAseq | Finding new therapeutical targets in tumour causing Cushing’s | GREEN | GSE275374 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE275374 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 40281543 | [104] | 29 prolactinomas | Bulk RNAseq | Cholesterol-activated stress granules reduce the membrane localisation of DRD2 and promote dopamine resistance | ORANGE | NA |

| 40390063 | [105] | 13 patients (somatic DNA DA-resistant lactotrophs) | Spatial transcriptomics and bulk RNAseq | PI3K/AKT pathway may constitute a molecular target at which to aim therapeutic strategies designed to treat aggressive and DA-resistant lactotroph PitNET | RED | NA |

| 40523964 | [106] | 1 mixed GH/PRL | scRNAseq | Whole-genome and single-cell analyses revealed KMT2D-driven PitNETs with tumorigenic pathways, immune changes, and epigenetic alterations like metastatic cancers | ORANGE | NA |

| 40598468 | [107] | 69 NFPTs | Bulk RNAseq | Differential gene expression between invasive and non-invasive NFPTs | ORANGE | HRA011612 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA011612 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

Colour codes indicate data accessibility: red, not accessible; orange, partially available or upon request; green, public repository without extended clinical data; blue, open-access repository with recent technologies and clinically annotated data. Abbreviations: scRNAseq, single-cell RNA sequencing; bulk RNAseq, bulk RNA sequencing; NA, not available. NFPTs: non-functioning pituitary tumours; LCM-RNAseq: laser capture microdissection RNA sequencing.

5.2. Genomics

Regarding genomic studies, we found a total of 39 studies. Among these, only 14 (36%) provided accessible data repositories (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genomic studies in PitNETs.

Table 2.

Genomic studies in PitNETs.

| PMID | Reference | Sample Size | Technology | Main Conclusion | Data Sharing | Data Repository |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21251114 | [56] | 13-prolactinoma tumour DNA | Affymetrix Genome-wide human SNP array 6.0 chip | Loss on chromosome 11 is linked to gene deregulation and may drive the aggressive and malignant behaviour of prolactin tumours | GREEN | GSE22615 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE22615); GSE32191 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE32191) accessed on 8 December 2025 |

| 26280510 | [108] | 20 acromegaly patients (somatic and germline DNA) | WGS and 1kGP HumanOmni2.5–8 Illumina Array | Somatotropinomas showed a low number of somatic genetic alterations | RED | NA |

| 26701869 | [109] | 31 acromegaly patients. Tumour and germline DNA | Custom NGS panel | cAMP pathway calcium signalling might be involved in the pathogenesis | ORANGE | In the paper |

| 27670697 | [110] | 125 patients. Tumour DNA (20 nonfunctioning, 20 prolactinomas, 20 somatotropinomas, 20 corticotropinomas, 20 gonadotropinomas, 10 tirotropinomas, 15 plurihormonal [11 GH + PRL, 2 GH + ACTH, 2 GH + TSH]) | WES | First genome-wide mutational in a large cohort | RED | NA |

| 27707790 | [111] | 42 patients. Tumour and germline DNA (26 null cell adenomas, 5 corticotropinomas, 5 somatotropinomas, 3 gonadotropinomas, 3 prolactinomas) | WES | Arm-level losses were significantly recurrent. No significantly recurrent mutations were identified, suggesting no genes are altered by exonic mutations across large fractions of pituitary macroadenomas | BLUE | EGAS00001001714 (https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS00001001714 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 29474559 | [112] | 44 somatotropinomas tumour and germline DNA | 180K Agilent array | GNAS WT somatotropinomas acquire tumorigenic characteristics through genomic instability | RED | NA |

| 30084836 | [113] | 48 patients. Tumour DNA (17 somatotropinomas, 13 corticotropinomas [including 3 silent], 18 NFPT) | WES | Recurrent somatic mutations were infrequent among the three adenoma subtypes. However, CNA was identified in all three pituitary adenoma subtypes | RED | NA |

| 31473917 | [114] | 12 prolactinoma patients. Tumour and germline DNA | CES | CNV may contribute to prolactinoma formation | RED | NA |

| 31578227 | [115] | 21 acromegaly patients. Tumour DNA | WGS and 1kGP HumanOmni2.5–8 Illumina Array | Aneuploidy through modulated driver pathways may be a causative mechanism for tumorigenesis in Gsp− somatotropinomas, whereas Gsp+ tumours with constitutively activated cAMP synthesis seem to be characterised by DNA-methylation-activated Gα | GREEN | EGAS00001003488 (https://ega-archive.org/search/EGAS00001003488 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 31692290 | [116] | 1 prolactinoma tumour and germline DNA | WGS | Identification of somatic mutations POU6F2 gene in a prolactinoma | GREEN | PRJNA509733 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/insdc/PRJNA509733 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 31883967 | [40] | 134 patients. Tumour DNA (35 corticotroph, 29 gonadotroph, 23 somatotroph, 16 lactotroph, 8 GH-PRL, 8 null-cell, 6 thyrotroph, 9 plurihormonal PIT1+) | WES and Infinium HumanCore-24 v1.0 BeadChip | Reference multiomics dataset | BLUE | EGAS00001003642 (https://ega-archive.org/search/EGAS00001003642 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 33168091 | [63] | 195 patients. Tumour DNA (56 gonadotropinomas, 11 null cell, 56 somatotropinomas, 39 prolactinomas, 33 corticotropinomas) | SurePrint G3 Human genome CGH + SNP Microarray | Genome instability was dependent on PitNET type | GREEN | E-MTAB-9237 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-9237 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 33472173 | [66] | 76 patients. Tumour DNA (28 prolactinomas, 11 somatotropinomas, 37 NFPT) | WGS | Genomic copy number amplifications are associated with worse prognosis | RED | NA |

| 33908609 | [67] | 36 patients. Tumour DNA (1 prolactinoma, 9 somatotropinomas, 7 corticotropinomas, 11 gonadotropinomas, 4 plurihormonals, 2 null cell adenomas) | WGS and single-cell multiomics sequencing. | PitNETs have a relatively uniform pattern of genome with slight heterogeneity in copy number variations | GREEN | PRJCA002946 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA002946 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 34313605 | [117] | 235 Patients. Germline DNA | Custom NGS panel | Screening of AIP and MEN1 variants in young patients and relatives is of clinical value | RED | NA |

| 34400688 | [118] | 30 acromegaly patients. Tumour and germline DNA | WES | 26 recurrent genes were found mutated | RED | NA |

| 35372359 | [71] | 22 NFPTs | WES | Somatic mutations revealed intratumoral heterogeneity and decreased response to immunotherapy in stiff tumours | GREEN | HRA000956 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA000956 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 35563252 | [119] | 10 patients. Tumour DNA (1 corticotropinoma silent, 1 Crooke cell adenoma, 3 somatotroph cell adenomas, 5 ACTH-secreting corticotropinomas causing Cushing’s disease, including 1 post-adrenalectomy Nelson syndrome) | WES | Functioning ACTH adenomas, including ACTH-CA, showed 10q11.22 amplification and higher CNV and SNV burden than nonfunctioning tumours | GREEN | PRJNA806516 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/insdc/PRJNA806516 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36026497 | [120] | 15 patients. Tumour and germline DNA (9 NFPT, 3 somatotropinomas, 2 prolactinomas) | WES | The use of multiple sequencing data analysis pipelines can provide more accurate identification of somatic variants in PitNETs | RED | NA |

| 36161330 | [121] | 111 patients. Tumour DNA (25 corticotroph, 19 somatotroph, 14 lactotroph, 50 gonadotroph, 1 null cell, 2 plurihormonal PIT1+) | Custom NGS panel | Combined genetic–epigenetic analysis, in association with clinico-radiological–pathological data, may be of help in predicting PitNET behaviour | GREEN | In the paper |

| 36307579 | [73] | 200 patients. Tumour DNA (21 somatotropinomas, 23 prolactinomas, 15 tirotropinomas, 22 silent PIT1, 20 plurihormonals, 21 corticotropinomas, 25 silent TPIT; 12 gonadotropinomas, 19 silent SF1, 22 NULL) | WES | GNAS copy number gain can serve as a reliable diagnostic marker for hyperproliferation of the PIT1 lineage | BLUE | Biosino: OEP003433 (https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP003433 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 36359740 | [74] | 12 patients. Tumour and organoid DNA (12 functional corticotroph (CD), 3 silent corticotroph, 9 gonadotroph, 8 lactotroph, and 3 somatotroph tumours) | WES | Tumour organoids represent a novel approach in modelling Cushing’s syndrome | ORANGE | NA |

| 36435867 | [75] | 166 patients. (121 somatotropinomas, 45 NFPT) | Custom NGS panel | The study identifies a biological connection between GNAS mutations and the clinical and biochemical characteristics of acromegaly | BLUE | In the paper |

| 38330165 | [84] | 146 acromegaly patients. Tumour and germline DNA | Custom NGS panel | KDM1A haploinsufficiency caused GIPR expression | RED | NA |

| 38651569 | [122] | 29 patients. Tumour and germline DNA (12 prolactinomas, 10 thyrotropinomas, 7 corticotropinomas) | WES | This study identifies CHEK2 variants in 3% of pituitary adenoma patients, suggesting a contributory role of this breast cancer gene in pituitary tumorigenesis | ORANGE | NA |

| 38656317 | [88] | 32 patients. Tumour and organoid DNA (7 gonadotropinomas, 1 lactotroph, 4 plurihormonals, 8 corticotropinomas, 4 somatotropinomas, 1 null cell, 7 NA) | WES | Pituitary neuroendocrine tumour-derived organoid resumes genomic features of primary tumours | ORANGE | NA |

| 38745824 | [123] | 134 patients. Germline DNA (46 prolactinomas, 17 somatotropinomas, 6 somatolactotroph, 26 nonfunctioning, 24 gonadotropinomas, 13 corticotropinomas, 2 thyrotropinomas) | WES | 6.7% of patients with apparently sporadic PAs carry likely pathogenic variants in PA-associated genes | ORANGE | NA |

| 38758238 | [124] | 92 patients. Tumour DNA (28 corticotropinomas, 13 prolactinomas, 5 somatotropinomas, 33 gonadotropinomas, 8 co-secreting GH/prolactin, 3 co-secreting GH/prolactin/TSH, 2 immunonegative). | MSK-IMPACT targeted sequencing panel | Aggressive, treatment-refractory PitNETs are characterised by significant aneuploidy due to widespread chromosomal LOH | GREEN | dbGaP (phs001783.v1.p1) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs001783.v8.p1 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39217365 | [94] | 11 patients. Tumour DNA (8 non-functioning gonadotropinomas, 1 corticotropinoma, 1 somatotropinoma, 1 metastatic corticotropinoma) | WES | Authors found genomic stability between primary and recurrent tumours | ORANGE | NA |

| 39272130 | [125] | 6 patients and family (X-LAG) | SNP Cytoscan HD platform | Preserved TAD boundaries in GPR101 duplications prevent X-LAG, validating 4C/HiC-seq for clinical use | GREEN | GSE193114 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA794841 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 39441837 | [126] | 61 patients. Tumour DNA (20 prolactinomas, 4 somatotropinomas, 1 thyrotropinoma, 10 corticotropinomas, 20 gonadotropinomas, 2 plurihormonals, 4 others [2 mammosomatotroph, 2 immature PIT1-lineage, 1 acidophil stem cell]) | 1500 SNPs array | Massive chromosomal losses are associated to aggressive tumours | ORANGE | NA |

| 39497133 | [127] | 40 acromegaly patients. Tumour DNA | WGS and CytoSNP-850 K Illumina Array | Somatotroph tumours can be classified into three relevant cytogenetic groups | ORANGE | NA |

| 40064730 | [128] | 134 patients. Germline DNA (38 prolactinomas, 44 somatotropinomas, 23 NFPT, 19 corticotropinomas, 2 gonadotropinomas, 3 tirotropinomas and 5 Plurihormonals) | Custom NGS panel | FGFR1 D129A variant may be associated with pituitary tumorigenesis | ORANGE | NA |

| 40248171 | [129] | 225 patients. Germline DNA (81 prolactinomas, 62 somatotropinomas, 37 NFPT, 16 mixed-secretion tumours, 15 corticotropinomas, 7 gonadotropinomas, 1 tirotropinoma and 6 NA) | WES | Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants were identified in 16 (7.1%) of these young patients | ORANGE | NA |

| 40390063 | [105] | 13 patients. Tumour DNA, DA-resistant lactotrophs | WES | Few genetic alterations found indicating that PitNET tumorigenesis could not be driven by genetic variants | RED | NA |

| 40415137 | [130] | 46 patients. DNA germline acromegaly patients | CES | TME may explain GH-secreting PitNET heterogeneity, but its gene regulation mechanisms remain unclear | RED | NA |

| 40523964 | [106] | 1 acromegaly patient with plurihormonal tumour. Tumour DNA | WGS | Seemingly quiet tumours can share features and epigenetic alterations with metastatic cancers | ORANGE | NA |

| 40544420 | [131] | 1 patient (2 corticotroph tumours and germline DNA) | WES | First genetic profiling of dual corticotroph tumours reveals distinct somatic variants influencing behaviour and a CYP21A1 mutation aiding tumorigenesis | ORANGE | SAMN47584567-9 (unable to find the dataset) |

| 40624119 | [132] | 20 patients (germline DNA from FIPA family) | WES | A novel AIP variant at splice acceptor site [(c.646-1G > C)] causing FIPA found | ORANGE | 10.5281/zenodo.15704233; (https://zenodo.org/records/15697716 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| NA | [133] | 14 acromegaly patients. Tumour DNA | WES | The study identified 30 somatic variants with a recurrent hotspot mutation in GNAS found in four patients | RED | NA |

Colour codes indicate data accessibility: red, not accessible; orange, partially available or upon request; green, public repository without extended clinical data; blue, open-access repository with recent technologies and clinically annotated data. Abbreviations: NA, not available. NGS: next-generation sequencing: NFPTs: non-functioning pituitary tumours: TME: tumour microenvironment. PA: pituitary adenoma, WGS: whole-genome sequencing, WES: whole-exome sequencing, CES: clinical exome sequencing.

5.3. Epigenomics

A total of 24 studies investigating DNA methylation and 1 Hi-C (chromosome conformation capture) study were identified, with 9 studies (38%) providing accessible data repositories (Table 3).

Table 3.

Epigenomic studies in PitNETs.

Table 3.

Epigenomic studies in PitNETs.

| PMID | Reference | Sample Size | Technology | Main Conclusion | Data Sharing | Data Repository | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24781529 | [134] | 24 PitNETs (17 NFPT, 5 somatotropinomas, 1 corticotropinoma, 1 silent corticotropinoma) | Illumina 450k | Hypermethylation of KCNAB2 and downstream ion-channel activity signal pathways may contribute to nonfunctioning status | GREEN | GSE54415 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE54415 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 29410024 | [135] | 34 NFPT and 6 normal pituitaries | Illumina 450k | Aberrant methylation contributes to deregulation of cancer-related pathways in NFPTs | GREEN | GSE115783 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE115783 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 29539639 | [136] | 2081 CNS tumours (9 normal pituitary tissue, 86 PitNETs [8 prolactinomas, 30 somatotropinomas, 18 corticotropinomas, 20 gonadotropinomas, 10 thyrotropinomas]) | Illumina 450k | Reference dataset for DNA methylation in CNS tumours and normal tissues | GREEN | GSE90496 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE90496); GSE109381 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE109381) accessed on 8 December 2025 | |

| 29967940 | [137] | Over 2000 CNS tumours (some PitNETs) | Illumina EPIC and Illumina 450k | Development of a diagnostic algorithm for CNS tumours based on DNA methylation | RED | NA | |

| 30084836 | [113] | 48 patients. Tumour DNA (17 somatotropinomas, 13 corticotropinomas [including 3 silent], 18 NFPT) | Illumina HumanMethylation450k | Recurrent somatic mutations were infrequent among the three adenoma subtypes. However, CNA was identified in all three pituitary adenoma subtypes | RED | NA | |

| 31578227 | [115] | 21 acromegaly patients. Tumour DNA | TBS | Aneuploidy through modulated driver pathways may be a causative mechanism for tumorigenesis in Gsp− somatotropinomas, whereas Gsp+ tumours with constitutively activated cAMP synthesis seem to be characterised by DNA-methylation-activated Gα | GREEN | EGAS00001003488 (https://ega-archive.org/search/EGAS00001003488 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 31883967 | [40] | 134 patients. Tumour DNA (35 corticotroph, 29 gonadotroph, 23 somatotroph, 16 lactotroph, 8 GH-PRL, 8 null-cell, 6 thyrotroph, 9 plurihormonal PIT1+) | Illumina EPIC | Reference multiomics dataset | BLUE | E-MTAB-7762 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/ArrayExpress/studies/E-MTAB-7762?query=E-MTAB-7762 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 33205234 | [64] | 8 NFPTs | Illumina 450k | Aberrant CNVs, dysregulated DNA methylation, and gene expressions in high-proliferative NFPTs | RED | NA | |

| 33631002 | [138] | 20 PitNETs | Illumina EPIC | Authors describe methylation signatures that distinguished PitNETs by distinct adenohypophyseal cell lineages and functional status | RED | NA | |

| 35212383 | [139] | 24 and 13 plasma and serum samples among other CNS tumours and healthy tissue | Illumina EPIC | Potential application of methylation-based liquid biopsy profiling | GREEN | Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/x954653zkr.1 (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/x954653zkr/1 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 35372359 | [71] | 22 NFPTs | Whole genome Bisulfite sequencing | Aberrant DNA methylation plays crucial roles in stiffness | GREEN | HRA000955 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA000955 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 36504388 | [76] | 77 tumours’ DNA (18 somatotropinomas, 13 corticotropinomas and 46 NFPTs) | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Methylation signature defines d groups associated with clinical presentation | BLUE | GSE207937 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE207937 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 37699356 | [81] | 48 somatotropinomas’ tumour DNA | Illumina EPIC methylation array | The authors found three molecular subtypes of somatotroph PitNETs | RED | NA | |

| 38228887 | [140] | 31 somatotropinomas | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Co-expressing PIT1 and SF1 PitNETs are a distinct molecular subtype of tumours | GREEN | GSE246645 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE246645 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 38347267 | [141] | 1 corticotropinoma | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Usefulness of DNA methylation profile for diagnosis | ORANGE | NA | |

| 38769659 | [90] | 3 somatotropinomas and 2 normal pituitaries | HiC | First comprehensive 3D chromatin architecture maps of somatotroph tumours | ORANGE | NA | |

| 38927917 | [142] | 42 PitNETs (29 gonadotropinomas, 5 corticotropinoma, 1 PIT1+, 1 null-cell) | Illumina EPIC methylation array | The DNA methylation profiling of nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas may potentially identify adenomas with increased growth and recurrence potential | ORANGE | NA | |

| 39217365 | [94] | 11 patients. Tumour DNA (8 non-functioning gonadotropinomas, 1 corticotropinoma, 1 somatotropinoma, 1 metastatic corticotropinoma) | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Authors found epigenomic stability between primary and recurrent tumours | ORANGE | NA | |

| 39220243 | [143] | 1709 CNS tumours (16 corticotropinomas, 38 gonadotropinomas, 14 somatotropinomas, 1 TSHoma) | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Molecularly classified brain tumour groups and subgroups show different distributions among the three main racial backgrounds | RED | NA | |

| 39497133 | [127] | 40 somatotropinomas | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Somatotroph tumours can be classified into three relevant cytogenetic groups | GREEN | GSE226764 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE226764 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

| 39580368 | [144] | 12 PitNETs (8 NFGPTs, 2 somatotropinomas and 2 corticotropinomas), 48 aggressive PitNETs and 17 pituitary carcinomas | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Different methylation profiles and CNV in aggressive and metastatic PitNETs | ORANGE | NA | |

| 39876960 | [145] | 2 prolactinomas tissue and 2 matched normal pituitary tissue and blood | Illumina EPIC methylation array | DNA methylation can be used to diagnosed with precision sellar lesions | RED | NA | |

| 40295206 | [146] | 118 PitNETs | Illumina EPIC methylation array | PitNETs’ classification may benefit from DNA methylation | RED | NA | |

| 40523964 | [106] | 14 tumour DNA (7 Pit1+ tumours, 3 corticotrophs, 2 gonadotrophs and 2 unknowns) | Illumina EPIC methylation array | Hypomethylation in the promoter of SPON2 | ORANGE | NA | |

| 40598468 | [107] | 69 NFPTs | RRBS | Differential gene expression between invasive and non-invasive NFPTs | ORANGE | HRA011612 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/search/specific?db=hra&q=HRA011612 accessed on 8 December 2025) | |

Colour codes indicate data accessibility: red, not accessible; orange, partially available or upon request; green, public repository without extended clinical data; blue, open-access repository with recent technologies and clinically annotated data. Abbreviations: NA, not available. NFPTs: non-functioning pituitary tumours; TBS: target region bisulfite sequencing; RRBS: reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, Illumina 450K: Illumina Human Methylation 450k array, Illumina EPIC: Illumina Infinium EPIC methylation array.

5.4. Proteomics

We found only five proteomic studies investigating PitNETs. Moreover, only two studies (40.0%) provided accessible data repositories.

Table 4.

Proteomic studies in PitNETs.

Table 4.

Proteomic studies in PitNETs.

| PMID | Reference | Sample Size | Technology | Main Conclusion | Data Sharing | Data Repository |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36435867 | [75] | 121 somatotropinomas and 45 NFPTs | DDMS | Integrated clinic, genetic, transcriptomics and proteomics analysis in a large acromegaly cohort | BLUE | PXD036604 (https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD036604 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

| 37253344 | [147] | 19 somatotropinomas | DIMS | CTSZ related to invasive transformation and poor prognosis in somatotroph PitNETs | RED | NA |

| 38157275 | [148] | 46 NFPTs | DDMS | Different proteomic profile in NFPTs that progress | ORANGE | NA |

| 39140195 | [149] | 20 NFPTs and 10 normal pituitaries | DDMS and DIMS | NOTCH3 and PTPRJ are upregulated in non-functional PitNETs | ORANGE | In the paper |

| 36307579 | [73] | 200 PitNETs (21 somatotropinomas, 23 prolactinomas, 15 tirotropinomas, 22 silent PIT1, 20 plurihormonals, 21 corticotropinomas, 25 silent TPIT; 12 gonadotropinomas, 19 silent SF1, 22 null cell) | DIMS and phosphoproteomics | The proteogenomic analysis of PitNETs reveals novel molecular subtypes and therapeutic targets, enhancing diagnosis and treatment strategies | BLUE | PXD031467 (https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD031467 accessed on 8 December 2025) |

Colour codes indicate data accessibility: red, not accessible; orange, partially available or upon request; blue, open-access repository with recent technologies and clinically annotated data. Abbreviations: NA, not available. MS: mass spectrometry: NFPTs: non-functioning pituitary tumours, DDMS: data-dependent acquisition MS, DIMS: data-independent acquisition MS.

5.5. Best Databases for Clinical Validation Studies

From the initial screening of almost one hundred studies, only six were ultimately selected as the most suitable resources for clinical validation (Table 5). Selection was based on three main criteria: (i) the data were openly accessible, ensuring transparency and reproducibility; (ii) the datasets were generated using up-to-date and widely accepted technologies, thereby maintaining methodological relevance; and (iii) the studies included clinically annotated information, allowing for linkage between molecular findings and patient outcomes. Notably, among these six studies (marked as blue in the previous tables), only one provided treatment response data that could directly inform therapeutic decision-making. This strikingly limited number of high-quality resources highlights a critical gap in the field: despite the growing availability of omics datasets, very few are accompanied by robust and clinically meaningful annotations. These six datasets therefore represent not only the current state of the art but also the best starting point for future efforts in clinical validation of ML models applied to PitNETs.

Table 5.

Selected omic studies in PitNETs (marked as blue).

5.6. Key Findings and Limitations of the Databases Reviewed

Taken together, the studies summarised in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 demonstrate a heterogeneous methodological landscape in PitNET research. Most investigations have relied on unsupervised clustering or differential analyses to identify tumour subgroups or candidate biomarkers, with only very few incorporating ML approaches for predictive modelling. Despite the diversity of omics layers analysed, key findings converge on the presence of molecular signatures that partially recapitulate clinical phenotypes and endocrine behaviours. However, studies lack external validation cohorts, standardised pipelines, and harmonised clinical annotation, which restricts the comparability of results and the translational potential of reported biomarkers. Moreover, sample sizes remain modest due to the rarity of PitNETs, limiting statistical power and contributing to overfitting risks when high-dimensional data are analysed. These constraints underscore the need for coordinated multicentre efforts, improved data sharing practices, and consensus on clinically relevant endpoints to enable robust, reproducible, and clinically actionable ML applications in this field.

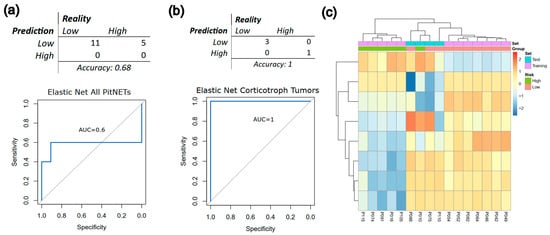

6. Machine Learning in PitNETs: Examples

To illustrate the feasibility of ML applications of publicly available datasets in PitNET research, we developed a supervised elastic net classifier using DNA methylation data from E-MTAB-7762. We analysed the dataset generated by Neou et al. [40] with the aim of distinguishing patients with a non-active disease course (annotated as “Remission” by authors) from those with an unfavourable prognosis (“Resistant” or “Aggressive”). Our analysis specifically focused on DNA methylation array data. The elastic net methodology was selected because it balances the advantages of LASSO (feature selection) and ridge regression (robustness against multicollinearity), which is a particularly appropriate property for high-dimensional methylation data.

A total of 64 PitNETs samples representing all lineages were subjected to elastic net classification (for methodological details, see Methods Section 2.3). Of these, 48 samples were allocated to the training set and 16 to the test set. Differential methylation analysis identified candidate CpGs associated with tumour behaviour. These CpGs formed the input variable set for the elastic net model. The model was trained using repeated stratified 10-fold cross-validation to optimise α and λ parameters and to ensure robustness of feature selection. Multiple iterations with different random partitions were performed; no substantial improvement in predictive performance was observed after the initial tuning stage, demonstrating model convergence and stability.

The final model was evaluated on an unseen test cohort. The resulting model achieved an overall accuracy of 0.68 and an ROC-AUC of 0.60 (Figure 3a). When applying the same methodology restricted to the analysis to corticotroph tumours (n = 16, 12 training set, 4 validation set), classification performance increased markedly, with both accuracy and ROC-AUC equal to 1.0 (Figure 3b). Nevertheless, unsupervised clustering of the CpGs selected by the model for corticotroph tumours demonstrated a clear separation between training and test cohorts (Figure 3c), raising concerns of potential overfitting, which is a major problem inherent with ML analyses when the sample size is limited and the dimensionality is high. Taken together with the limited sample size, these results suggest that while the approach may be useful for identifying candidate predictive markers, validation in larger, independent cohorts is required to ensure robustness and generalisability. However, although the test cohort size was limited—an unavoidable constraint in rare tumour settings—the repeated cross-validation and model convergence support the reliability of the observed predictive behaviour.

Figure 3.

Proof-of-concept application of machine learning (ML) to classify high-risk PitNETs using DNA methylation data from Neou et al. [40]. (a) Confusion matrix and ROC curve derived from an elastic net classifier trained on the entire cohort highlight the limitations imposed by small sample sizes and heterogeneous tumour lineages. (b) Confusion matrix and ROC curve from the same model restricted to corticotroph tumours show improved performance but also indicate susceptibility to overfitting, given the very limited number of cases. (c) Dendrogram and unsupervised hierarchical clustering heatmap generated using the CpGs selected by the corticotroph-specific model, illustrating the underlying methylation patterns captured by the classifier. Collectively, these results illustrate the feasibility of applying ML approaches to PitNET methylation data while underscoring the current constraints posed by scarce, clinically annotated cohorts.

Our study demonstrates that when attempting to validate analyses using other datasets, most lack clinical data. Even when some clinical information is presented, the variables—apart from radiological measures—are often quite heterogeneous between datasets, making it difficult to validate research findings and develop integrative algorithms. Also, we confirm that the heterogeneous biological nature of PitNETs makes it virtually impossible to generate valid classifiers when mixing different tumour histopathologic types. This example should not be interpreted as a definitive predictive model but rather as a proof of concept constrained by the limited availability of clinically annotated PitNET cohorts. The modest performance obtained with the full dataset and the apparent overfitting observed in the corticotroph subset underscore the current limitations of applying ML to rare tumours: insufficient sample sizes, lack of standardised outcomes, and scarcity of independent validation cohorts. These results highlight the urgent need for coordinated data sharing and harmonisation efforts to enable the development of clinically robust models.

However, since all available datasets provide histopathological annotation of the tumour type, a paradigmatic example of their utility is the study by Rymuza et al. [150]. By integrating bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data from multiple public sources, the authors investigated the molecular identity of acromegaly-related PitNETs co-expressing the transcription factors PIT-1 and SF-1. Through analysis of 546 transcriptomic profiles using approaches such as WGCNA (weighted correlation network analysis), regulon inference, pseudotime trajectory analysis, and gene set enrichment, they demonstrated that these double-positive tumours are transcriptionally aligned with the PIT-1 lineage rather than representing true multilineage or gonadotroph origin.

Complementing these results, Dottermusch et al. [140] performed a comprehensive molecular and clinicopathological meta-analysis of 270 somatotroph tumours, integrating both in-house and publicly available datasets. By combining DNA methylation profiling, transcriptomic clustering, and copy number variation analysis, they showed that PIT-1/SF-1-co-expressing tumours represent a distinct subtype within the PIT-1 lineage, rather than a generic “plurihormonal” category. Taken together, these findings complement the current WHO classification and support the development of a refined, next-generation taxonomy for PitNETs, grounded in integrated multiomics evidence.

7. Discussion

The present review highlights that, while considerable effort has been devoted to the molecular characterisation of PitNETs, the transition towards predictive and personalised medicine is still in its early stages. The heterogeneity of tumour behaviours—ranging from indolent to highly aggressive courses—cannot be accurately deciphered using histopathology or single-layer molecular markers alone. This underscores the need for computational approaches capable of synthesising complex, multimodal datasets with huge information into reproducible clinical predictions. Importantly, any clinical diagnostic tool—including ML algorithms—must ultimately comply with regulatory standards to be used in routine practice.