Abstract

Background/Objectives: Dizziness is a symptom of many disorders across a wide range of etiologies. If dizzy patients are seen for vestibular evaluation with an audiologist and no vestibular reason for the patient’s dizziness is found, the medical referral pathway can become convoluted. This can leave patients feeling discouraged and unable to manage their symptoms. Clinically symptomatic chronic respiratory alkalosis (CSCRA) is an acid–base disorder that typically presents with dizziness but is unfamiliar to practitioners in vestibular and balance care settings. Methods: In a retrospective chart review deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, 74 patients at Mayo Clinic Arizona were included. All had consultations with both Audiology and Aerospace Medicine to assess their dizzy symptoms. Results: After completing vestibular testing, arterial blood gas (ABG) testing, and a functional test developed at Mayo Clinic Arizona called the Capnic Challenge test, 40% of patients were found to have CSCRA contributing to their dizzy symptoms. Many of these patients also had common comorbidities of CSCRA, like postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), migraines, and sleep apnea. Fewer than one-fourth of these patients had measurable vestibulopathies causing their dizziness. Half of the patients referred by the vestibular audiologist to Aerospace Medicine had a diagnosis of CSCRA. Conclusions: Assessment for CSCRA should be considered as a next step for patients presenting with dizziness without a vestibular component. Being aware of the prevalence of CSCRA and its comorbidities may help balance providers offer quality interprofessional referrals and improve patient quality of life.

1. Introduction

Dizziness, including sensations of vertigo, lightheadedness, and unsteadiness, is the primary symptom of vestibular disorders. When reported, a complaint of non-specific dizziness usually leads to a referral to Audiology services for assessment of the vestibular system. In a systematic review of dizziness reports in primary care settings, there were a range of known etiologies for dizzy symptoms (e.g., benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Meniere’s disease, cardiovascular disease), but in up to 80% of cases across the articles reviewed, they were assigned the category “No specific diagnosis possible” [1]. Many patients feel frustrated due to the lack of a known cause and treatment for their dizziness or lightheadedness, resulting in a reduced quality of life. Respiratory changes can cause dizziness, but these mechanisms are not well-appreciated by audiologists and other balance specialists.

Clinically symptomatic chronic respiratory alkalosis (CSCRA) is a state of reduced blood carbon dioxide (CO2) due to altered breathing patterns, resulting in an alkaline blood pH [2,3,4,5]. Chronic alterations in breathing patterns can result from respiratory disorders, like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but are also prevalent amongst people living at high altitudes or those with cardiac, autonomic, and neurological disorders [6]. Appendix A details the physiology of CSCRA. Symptoms of CSCRA include breathlessness, chest tightness, nausea, lightheadedness, presyncope/syncope, headache and disequilibrium, and dizziness [3,5,7,8]. Medical conditions that are commonly associated with CSCRA include autonomic disorders (e.g., postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS]), altitude sickness (as compensatory changes for hypoxemia), migraines, obstructive and central sleep apnea, traumatic brain injury (TBI), concussion, and anxiety [5,9,10,11,12,13]. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the comorbidity of vestibular symptomatology and concomitant CSCRA to promote effective multi-disciplinary diagnosis and care for patients experiencing reduced CO2 levels.

Clinicians in the Aerospace Medicine Program and the Aerospace Medicine and Vestibular Research Laboratory at Mayo Clinic Arizona conducted a retrospective chart review to assess the incidence of CSCRA in patients who underwent both vestibular assessments and acid–base status evaluations using arterial blood gas (ABG) testing and functional symptom provocation (i.e., Capnic Challenge). These patients frequently present with non-localizing dizziness symptoms, and CSCRA can occur alongside various medical conditions that also cause dizziness. As a result, they frequently receive referrals for vestibular assessments. The researchers aimed to retrospectively assess the prevalence of comorbid conditions that present with dizzy symptoms in patients diagnosed with CSCRA. It is important for vestibular specialists to understand the etiology, symptoms, and comorbidities of CSCRA. This knowledge will help them recognize when chronically reduced CO2 might contribute to non-vestibular dizziness or worsen symptoms stemming from an existing vestibular weakness, empowering them to make proper referrals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Patients at Mayo Clinic Arizona were seen by providers in the Aerospace Medicine Program for consultation via referrals from the Division of Audiology and the Departments of Neurology, Internal Medicine, Psychiatry, and Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. The electronic medical charts of 792 patients presenting to the Aerospace Medicine Program between April 2016 to November 2023 were reviewed in the current retrospective study (IRB Exemption ID: 24-000040).

74 participants met the inclusion criteria (51 female, 23 male). Medical record numbers were entered directly into Epic electronic medical records software, May 2025 version (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI, USA), and filters identified applicable documentation. The two primary data abstractors (SEK, HAK) have their Doctorate of Audiology (Au.D.) degrees and completed their vestibular training in the Mayo Clinic Arizona Division of Audiology; they reviewed all the coding of the tertiary data abstractor (NV), a research trainee in the Aerospace Medicine Program [14].

2.2. Procedures

In this chart review, patient records from the Division of Audiology and the Aerospace Medicine Program at Mayo Clinic in Arizona were analyzed. The patients of interest for this review had to have a vestibular evaluation, an ABG assessment, and a functional symptom test called the Capnic Challenge. The results of the ABG test and Capnic Challenge were discussed with the patient in a consultation with the Aerospace Medicine Program. The intent of the Aerospace Medicine consultation is not only to determine acid–base status, but also to identify underlying root causes requiring diagnostic interventions and treatment. At Mayo Clinic Arizona, a vestibular assessment is a comprehensive appointment that tests central and peripheral vestibular function by assessing the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) at low, medium, and high frequencies. Depending on the symptoms reported by the patient and applicable contraindications, the audiologist will decide which tests to conduct, but nearly every patient undergoes a videonystagmography (VNG) battery, including oculomotor and positional testing, Video Head Impulse Testing (vHIT), rotary chair testing, and vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) testing.

The following test battery is used during an Aerospace Medicine consultation to assess the effects of suspected CSCRA and provide a diagnosis: ABG testing, a comprehensive metabolic profile, urinalysis, lactate testing, assessment of diaphragmatic function, and Capnic Challenge testing. ABG testing requires a blood sample from an artery to provide an immediate measurement of blood pH, partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2), partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2), and oxygen saturation [15,16]. The comprehensive metabolic profile is necessary to complete acid–base analysis [17]. The provider interprets the primary acid–base disorder and secondary compensation mechanism based on the Stewart Strong Ion Difference Calculation [18,19]. This calculation determines the expected bicarbonate change to determine acid–base status [18]. Possible diagnoses include respiratory alkalosis, respiratory acidosis, metabolic acidosis, and metabolic alkalosis, or testing could be within normal limits. Many patients present with mixed acid–base disorders [20]. In these cases, blood pH levels can be near-normal due to the opposing effects created by mixed disturbances and compensation, but the effects on organs and intracellular pH can be deleterious [20]. The Capnic Challenge is a functional test to assess frequency of experienced symptoms and provoke hypocapnia symptoms. By actively provoking symptoms that come from driving down CO2 levels through timed hyperventilation, providers can assess symptom severity, normalize carbon dioxide levels with recovery methods, and assess resolution of symptoms [21]. The combination of these assessments provides a novel and multifaceted approach to diagnosing CSCRA.

2.2.1. Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Testing Protocol

During ABG testing, a blood sample is taken from an artery, typically in the arm, to precisely assess oxygenation, hemoglobin saturation, and acid–base status [15,16]. ABG testing is performed on patients in a state of rest without preceding exercise. In the Aerospace Medicine Program, this testing does not take place on the same day as the Capnic Challenge testing or any procedures that could alter acid–base status (e.g., exercise testing, sedation, etc.). The following components are measured from the arterial blood sample: pH, PaCO2, PaO2, total hemoglobin, O2 saturation, carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, calculated O2 content, bicarbonate concentration, and base excess [15,16,18]. Acceptable normal ranges for PaCO2 are between 35–45 mm Hg, and the normal range for blood pH is 7.35–7.45 [15]; in cases of CSCRA, the pH is basic (over 7.45) and PaCO2 tends to be under 35 mm Hg [22,23]. The ABG analyses are carried out by an experienced team of respiratory therapists determine primary and secondary acid–base disorders [18]. While situational stress may induce a component of acute respiratory alkalosis in any individual undergoing a blood draw, mere acute changes would only slightly affect bicarbonate levels, allowing for differentiation from a chronic respiratory alkalosis with substantially lower bicarbonate [15,18]. Determining if respiratory alkalosis is in the acute or chronic stage depends on the degree and level of change in bicarbonate measured from the metabolic profile and ABG analysis. In chronic respiratory alkalosis, the bicarbonate is expected to fall far more than in acute respiratory alkalosis [24].

2.2.2. Capnic Challenge Protocol

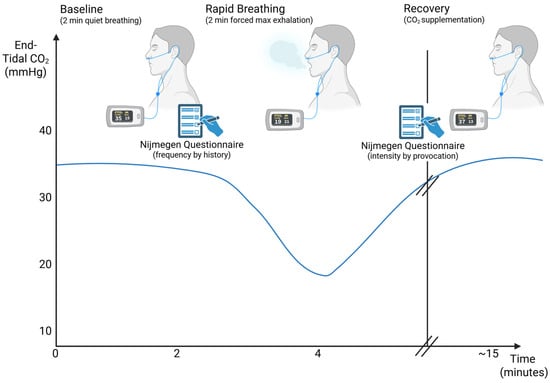

The purpose of the Capnic Challenge is to elicit CSCRA symptoms and quantify those symptoms using the Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ), a screening tool for chronic hyperventilation (Appendix B) [25,26,27]. The NQ was developed in 1983 to assess the hyperventilation syndrome by quantifying symptom load [25,26]. The NQ lists a set of 16 hyperventilation symptoms and asks how frequently a patient experiences the symptoms on a 0–4 scale (0 = Never; 4 = Very Often). The total score can range from 0–64, and scores of 23 and greater are consistent with hyperventilation syndrome-related symptoms. In the Capnic Challenge, patients complete the NQ twice—before and after the guided breathing portion of the test. The first NQ is used to qualify which symptoms they experience and quantify the frequency of those symptoms in the past six months to one year. The second NQ, completed after the Capnic Challenge, is used to quantify the severity of the symptoms that were elicited by the breathing challenge and related desired drop in CO2 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Illustration of Capnic Challenge Test Protocol across time. Created in BioRender (biorender.com, accessed on 29 December 2025). Kingsbury, H. (2025). Modified from Stepanek (2025) [5].

The patient is first instructed to breathe normally and quietly for 2 min without speaking. Then baseline oxygen saturation and expired CO2 levels are measured with a finger pulse oximeter and nasal cannula (sidestream end-tidal CO2). Still breathing as usual, the patient completes a writing sample for fine motor assessment as well as the first NQ. The NQ taken prior to the Capnic Challenge test assesses how frequently the patient has historically experienced hypocapnia/hyperventilation symptoms in their activities of daily living. Then, the patient is instructed to increase his or her breathing rate and depth with guided pacing (~60–100 bpm tempo) for two minutes with measurement of pulse oximetry and ETCO2 [5].

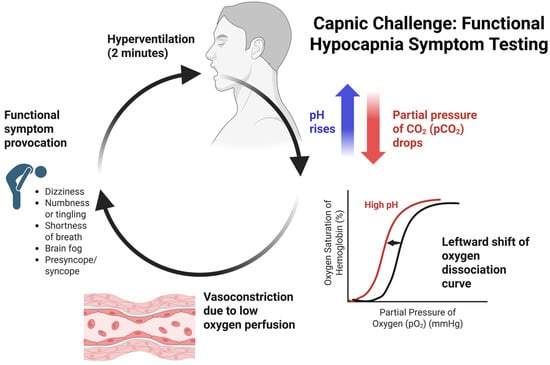

Functionally, excess ventilation lowers the PaCO2 levels, resulting in cerebral vasoconstriction and related symptoms like lightheadedness, altered motor control, and dizziness (see Figure 2) [28]. After the rapid breathing period of two minutes, the writing sample is completed again to reassess the effects of acute hypocapnia on fine motor and neurocognitive function. Then, the patient is provided with CO2 supplementation via oral effervescent tablets [21] or carbogen gas (95% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide) inhalation until subjective symptoms are resolved [21,29]. The NQ is readministered to assess the intensity of the symptoms that were just provoked during the Capnic Challenge, and the writing sample is completed for the final time.

Figure 2.

Capnic Challenge Symptom Provocation flowchart focusing on physiological changes and symptoms. Created in BioRender (biorender.com, accessed on 29 December 2025). Kingsbury, S. (2025).

2.3. Data Analysis

The following patient demographics were recorded in the current chart review: sex, age, referral source for Capnic Challenge testing, Audiology vestibular assessment results, NQ scores, comorbid diagnoses, ABG testing primary diagnosis, and ABG testing secondary diagnosis. Primary data extractors (SEK and HAK) collected data from the electronic medical records for each patient and recorded applicable diagnoses and scores in an Excel spreadsheet. Data analysis was completed in Microsoft Excel software, version 2502 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Referrals

Of the 792 patients who were in the Aerospace Medicine consultation database at the onset of this chart review, 74 patients had completed vestibular assessment appointments, ABG testing, and the Capnic Challenge. Fifty-five patients completed their vestibular assessment prior to their Aerospace Medicine consultation. Fifty-one of these vestibular assessments were completed at Mayo Clinic Arizona, 2 were completed at Mayo Clinic Florida, and 2 were completed with outside vestibular providers. The average time elapsed between the vestibular evaluation to an Aerospace Medicine consultation was 0.80 years (292.54 days). Based on the Interquartile Range method, there were 3 outliers removed, as their time from vestibular evaluation to Aerospace Medicine consultation was greater than 3.69 years (upper bound), indicating that their encounters with both specialties were likely unrelated.

Since audiologists cannot place orders at Mayo Clinic, in the context of this paper, a “referral” means the patient was recommended to follow up with the department mentioned in their clinical note, or back to their referring provider. Most patients had 2–3 referrals, on average. Out of the 51 patients with initial vestibular evaluations performed at Mayo Clinic Arizona, 12 people were referred to Aerospace Medicine by their vestibular assessment provider. Most patients had Neurology referrals, with 4 being referred to Neurology for new consultations and 35 being referred to return for follow-up with their neurologist. Twenty-four were referred to Physical Therapy to start or continue vestibular rehabilitation, and 6 were referred to Otolaryngology medical providers for new or pre-existing ENT medical consultations. Eight were referred to Integrative Medicine, 5 to Psychiatry or Behavioral Medicine, and 1 to Sleep Medicine. For the 12 patients who were referred by the vestibular audiologist to Aerospace Medicine, 6 patients, or half, met the clinical definition for CSCRA.

3.2. Diagnostic Classification

Of the 74 patients seen jointly for vestibular assessment appointments and Aerospace Medicine consultations, 35 had NQ scores from Capnic Challenge testing that were positive by history and provocation. They had high scores (>23) on the NQ measuring symptom intensity based on their historical symptoms and as well as after the paced breathing portion (by provocation), indicating that there is a high likelihood these patients are experiencing symptoms related to alterations in carbon dioxide levels. For the remaining patients, 19 had positive NQ scores by history but negative scores (<23) by provocation; note that not all patients could complete the full 2 min of timed breathing, reducing the sensitivity of the provocation testing. One patient had NQ scores negative by history but positive by provocation, and 19 had NQ scores negative by both history and provocation, constituting a negative Capnic Challenge.

Of the 74 patients, 40 were diagnosed with primary respiratory alkalosis at their initial consultation based on their ABG test results. Twenty-one had a different primary acid–base disorder, with many of them being influenced by medication and hydration levels, and the remaining 13 had ABG results within normal limits. Combining the results of the Capnic Challenge with the ABG testing revealed that 30 patients met the clinical definition for CSCRA by having positive NQ results by history and/or provocation and an ABG diagnosis of respiratory alkalosis. Of note, there were 10 patients with ABG testing indicating primary respiratory alkalosis but were non-symptomatic based on a negative Capnic Challenge result (NQ scores < 23 for both history and provocation).

3.3. Comorbid Diagnoses

Patients presenting with CSCRA symptom loads often had other diagnoses that were causally contributing to their dizziness or chronic dysfunctional breathing patterns (see Table 1). Dysfunctional breathing is a class of breathing disorders characterized by chronic changes in breathing patterns, often as a manifestation of an underlying disease, resulting in shortness of breath [6]. Many patients were diagnosed before, concurrently, or after their Audiology and Aerospace Medicine consultations with the following conditions: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), migraines, sleep apnea, or vestibular pathology. Of the 74 patients meeting the appointment history inclusion criteria, 30 had migraines and 14 had POTS; 11 patients had both POTS and migraines. Eleven patients of the 74 had central or peripheral vestibulopathies when they completed their vestibular assessments, which were ordered based on patient reports of dizziness. Finally, 5 patients had a comorbid diagnosis of sleep apnea, either obstructive or central in nature. Of the 30 patients with CSCRA, 15 had migraines, 7 had POTS, 7 had measurable vestibulopathy, and 2 had sleep apnea. Of the 7 patients who had POTS in the CSCRA sample, 6 of them also were diagnosed with migraines.

Table 1.

Comorbid diagnoses of patients with joint vestibular assessment appointments and Aerospace Medicine consultations and of patients with CSRCA.

4. Discussion

Patients with CSCRA frequently have dizziness as part of their symptom profile, and CSCRA often presents comorbid with other disorders that receive vestibular assessment referrals, like POTS, migraines, sleep apnea, and anxiety. Recognizing the hallmarks of CSCRA, common comorbid diagnoses, and the relationships between dizziness, anxiety, and CSCRA can help vestibular providers respond appropriately, in testing, counseling, documentation, and referrals to facilitate interprofessional care.

Not every patient included in this review who had a positive Capnic Challenge symptom provocation test had an acid–base status altered enough to become respiratory alkalosis, and some individuals had respiratory alkalosis without a positive Capnic Challenge test. The reason that CSCRA is often associated with hypobaric hypoxemia (increasing altitude), pulmonary disorders, tissue hypoxia, central nervous system disorders including TBI, or pain-related/psychological disorders is because all these conditions alter breathing patterns. Thus, the body increases the depth and rate of breathing to maintain arterial O2 levels [3,22,23]. When PaO2 is reduced, increased ventilation is stimulated through chemoreceptor signaling from the carotid and aortic bodies [23]; even though O2 levels are preserved, CO2 is expelled at a higher-than-normal rate, leading to a prolonged deficit that can lead to a higher (more alkaline) blood pH. Sometimes, secondary CSCRA is a compensatory response to metabolic disorders that make the blood more acidic as a natural defense against a decreased pH [30,31].

Ten patients had negative NQ scores by history and provocation on the Capnic Challenge but were identified as having respiratory alkalosis via ABG testing. This could be for several reasons, including symptom type and load, ability to complete the full two minutes of guided breathing, and reporting bias, with patients underreporting symptoms on the NQ. Some individuals test positive for respiratory alkalosis on their ABG test but have a symptom load that is well tolerated. They may also have non-traditional symptoms, like muscle cramps or vision issues [32]. Moreover, for patients with acid–base disturbances, the timed breathing portion of the Capnic Challenge, can be highly stressful or uncomfortable, especially when patients start to aggravate their symptoms. The team member who administers the test (KB) observes that nearly half of all patients who start Capnic Challenge testing self-terminate their deep breathing portion before the two-minute mark, with some only participating for 20–30 s. They still complete the NQ and the writing sample and are provided with recovery CO2 as necessary. Failure to complete the full two minutes of rapid breathing reduces the sensitivity of the test, since ETCO2 may not have been sufficiently lowered to trigger symptom manifestations in all domains of the NQ to qualify as a positive test. Clinical presentation of signs and symptoms is of paramount importance in patient evaluation, and laboratory testing serves to corroborate findings and direct patient care. Therefore, these 10 patients may in fact have CSCRA, but due to their subjective report on the NQ, they do not meet standard expected diagnostic criteria. These patients are still managed by the Aerospace Medicine physicians to identify and treat underlying causes of their acid–base disorders.

The NQ is a questionnaire based on subjective self-report of symptoms and has a limited number of items, so people may not identify their symptoms on the questionnaire but will answer affirmatively when they are asked about having a particular experience consistent with a symptom on the NQ. A weakness of the NQ is that the scale of discrete options used to describe symptom frequency and intensity are not qualified with descriptors. For example, the words “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” and “Very Often” are used instead of measurable counts, like “Once a month,” “Twice a week,” or “Daily.” Over thirty years after creating the NQ, van Dixhoorn and Folgering commented that at the time, it was primarily developed as a screener for hyperventilation syndrome [25,26,27]. Later studies have identified a high correlation between the NQ and ETCO2 when assessing the validity and reliability of the NQ in patients with asthma [27,33]. Despite the inherent subjective limitations of the NQ, to date, it is the most validated instrument to assess patients with altered CO2 levels [27,33].

CSCRA is often comorbid with and exacerbated by autonomic disorders, like POTS, as well as migraines (including vestibular migraines), and sleep apnea [5]. In the current study, 50% of the patients diagnosed with CSCRA (n = 30) had migraines, and 23.3% of the patients had POTS. In a study by Novak and colleagues, there was a 63.6% comorbidity of headaches in their POTS sample [13]. For those patients with POTS and/or migraines, the average historical NQ score (score of 33) was well above the cutoff score of 23 points. For the historical NQ, that means that POTS/migraine patients who also have CSCRA report hyperventilation symptoms more frequently than the average CSCRA patient. For the provocation NQ after Capnic Challenge testing, POTS and migraine patients with CSCRA also report more intense symptoms on average (score of 31) than those with CSCRA alone when provoked. Cohort survey-based analysis and retrospective chart studies suggest at least 64% and potentially up to 90% of all POTS patients have dysfunctional breathing, a rate significantly higher than the general population [34,35]. The dyspnea characteristic of POTS renders it just as much a respiratory disorder as an autonomic one [12]. Recognizing, however, that many of these patients could have concomitant CSCRA means that treating the underlying acid–base disorder can significantly improve the lived experience of those with comorbid conditions.

At Mayo Clinic, strong referral pathways have been established between Neurology and Audiology, due to the high number of vestibular migraine patients treated. For this reason, over half of the patients had repeat or new referrals to Neurology. In interprofessional medical settings, when no neurological, vestibular, or autonomic reason for dizziness can be found, the next specialty patients tend to be referred to is Psychology, typically with a diagnosis of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) [36,37]. In the current study, 13 of the patients with care established in both Neurology and Audiology departments were also referred to services in Psychiatry, Behavioral Medicine, or Integrative Medicine. While Psychology might be the next correct referral, it is crucial that CSCRA be considered a potential confounder in the relationship between dizziness and anxiety, since CSCRA objectively worsens physiological symptoms of anxiety [5,38]. It is incorrect (and potentially psychologically damaging) to conclude that all symptoms related to anxiety are psychosomatic in nature. For instance, a well-known manifestation of anxiety, a panic attack, is colloquially viewed as the result of a fear response driven by conscious thoughts. However, altered breathing patterns (e.g., involuntary breath holding, shallow breathing) are a hallmark of anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [39,40]. This means that even when the person is not actively hyperventilating, their breath cadence can be altered enough where not enough O2 is being inspired and/or too much CO2 is being expired, making hemoglobin more reluctant to release O2 into the bloodstream. The prolonged altered breathing state characteristic of clinical anxiety may initially result in sensations of lightheadedness, dizziness, tingling, and chest tightness, and these symptoms can trigger an autonomic fear response and prompt swift intake of air. The combination of CO2 levels that are being driven down by hyperventilation, reduced cerebral perfusion, and a highly aroused nervous system creates a perfect physiological storm. The literature supports a high prevalence of panic disorder in patients with COPD and other respiratory illnesses, or conditions that impair respiratory function and oxygen transport [41,42]. Many syndromic presentations in patients historically labeled as “functional disorders” provide an opportunity to pursue a diligent evaluation encompassing applicable pathophysiology.

Limitations and Future Directions

Considering CSCRA as a third player in the fraught relationship between anxiety and dizziness allows for appropriate referrals to treat an underlying acid–base disturbance, allowing for reduced symptom loads and improved management of other mental and physical conditions. The nature of this chart review is that the cohort selected has implicit referral bias and access to Aerospace Medicine expertise [5], so prevalence estimates may not be able to be broadly generalized in a dizzy population. However, the importance of balance providers being aware of CSCRA may offer opportunities to uncover underlying subclinical conditions driving dizziness symptoms. Investigating the Capnic Challenge, including its sensitivity and utility in balance research protocols, is of interest for future prospective studies. Increasing research into the relationship between clinical anxiety and imbalance has shed new light onto the phenomenon of abnormal Sensory Organization Test (SOT) results during Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP) balance assessment. The prior literature has long noted the inconsistent pattern of SOT results for patients with anxiety [43,44,45]. In many cases, performance on Conditions 1 (Eyes Open, Stable Surface, Stable Visual Surround) and 4 (Eyes Open, Sway-Referenced, Stable Visual Surround) are worse than Conditions 2 and 5 (Eyes Closed) as well as Conditions 3 and 6 (Sway-Referenced Visual Surround); this result pattern has long been described as “aphysiologic.” While some researchers posit that stiffened muscles or the fear of falling could contribute to poor balance on a stable surface, further investigation should focus on the role of altered breathing patterns in anxiety affecting stability and SOT performance.

5. Conclusions

Dysfunctional breathing patterns and specifically the presence of CSCRA need to be considered as a factor for all dizzy patients at vestibular appointments, especially those with vertiginous symptoms and no measurable vestibulopathy. Greater awareness of CSCRA in Audiology and other balance care specialties could foster improved interprofessional care and improved quality of life for dizzy patients.

There are practical questions that audiologists can ask their patients so that their documentation can help other providers, including:

- “Is your dizziness worse at altitude or when you fly?”

- “Do you have difficulty concentrating or brain fog?” (Morning fatigue could point to a lack of oxygen inspired overnight.)

- “Do you have concerns about your sleep quality?”

- “Do you think fatigue contributes to your balance issues?”

- “Do you suffer from post-exercise malaise or nausea?”

Access to interprofessional care can be affected by many socioeconomic and geographic factors, but increased awareness of CSCRA can improve the quality and type of referrals provided to dizzy patients. Appropriate referrals include cardiology, pulmonology, or sleep medicine; creating positive relationships and referral channels with providers in these specialties will encourage true interprofessional practice. CO2 supplementation, breathing exercises, and the temporary use of prescribed carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can improve dizziness and syncope in patients who have CSCRA without vestibulopathies as well as those with vestibular disorders comorbid to CSCRA, improving quality of care for all patients.

6. Patents

Jan Stepanek, Michael J. Cevette, Gaurav N. Pradhan, Samantha J. Kleindienst, Jamie M. Bogle, Rebecca S. Blue, and Karen K. Breznak. Methods and materials for treating hypocapnia, US Patent 2023/0112453 A1, filed 13 December 2022, and published 13 April 2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.K., & J.S.; Data curation, S.E.K., H.A.K., N.V., & J.S.; Formal analysis, S.E.K., H.A.K., & N.V.; Investigation, S.E.K., H.A.K., G.N.P., N.V., K.B., & J.S.; Methodology, S.E.K., H.A.K., & J.S.; Project administration, S.E.K., H.A.K., & J.S.; Resources, M.J.C., & J.S.; Supervision, S.E.K., G.N.P., M.J.C., K.B., & J.S.; Validation, S.E.K., & G.N.P.; Visualization, S.E.K., H.A.K., & J.S.; Writing—original draft, S.E.K., H.A.K., G.N.P., & J.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.E.K., H.A.K., G.N.P., M.J.C., & J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mayo Clinic internal funding with philanthropic funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study (“Prevalence of Dyscapnia (Abnormal Carbon Dioxide Levels) in Vestibular Referrals”) was exempted from continuing review by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic (IRB protocol # 24-000040 and exempted on 21 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to this study being deemed exempt from continuing review by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Aerospace Medicine Program administrative staff for their diligence in maintaining thorough records of Capnic Challenge patient appointments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSCRA | Clinically Symptomatic Chronic Respiratory Alkalosis |

| BPPV | Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo |

| POTS | Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| TBI | Traumatic Brain Injury |

| VOR | Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex |

| VNG | Videonystagmography |

| vHIT | Video Head Impulse Testing |

| VEMP | Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| ABG | Arterial Blood Gas |

| PaO2 | Arterial Partial Pressure of Oxygen |

| PaCO2 | Arterial Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide |

| NQ | Nijmegen Questionnaire |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| ETCO2 | End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide |

| SOT | Sensory Organization Test |

| CDP | Computerized Dynamic Posturography |

Appendix A. Physiology of CSCRA

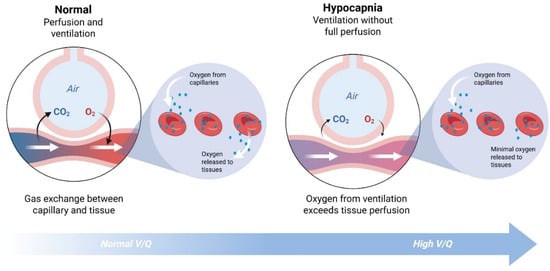

Gas exchange during respiration is commonly understood as that when O2 is inhaled, CO2 is exhaled. While CO2 is widely considered to be a waste gas that is expelled upon exhalation, having a consistent store of CO2 in the body, manifesting as an arterial CO2 tension (PaCO2) between 35–45 mmHg, is essential for regulation of blood pH, breathing, blood flow, and normal tissue oxygen delivery [2,9,22,32,46]. The body’s pH must be tightly maintained between 7.35–7.45 for enzyme, muscle, nerve, and organ function, and it is done so through CO2 dissolving in the blood, forming carbonic acid [4]. Over time, if there is persistently too much CO2, respiratory acidosis occurs, or the blood becomes more acidic; if there is too little CO2, respiratory alkalosis occurs, and the body becomes too basic [32]. Hypoxia receives far more medical attention than hypocapnia due to the distress and danger that acute hypoxia presents to survival. Unlike O2, in which there are only 1.2 to 2 L stored in the body, the body can store large, flexible reserves of CO2. Large reserves of CO2 can be stored because bicarbonate, the byproduct of carbonic acid dissociation, is in solution in the blood and widely stored in the tissues [2,3]. These tissue stores are constantly changing with metabolism and respiration, but prolonged altered respiration patterns will lead to an overall depletion of tissue stores of CO2 and tissue buffering capacity [5].

While not as immediately threatening as low O2, depleted CO2 levels lead to altered, irregular respiration, reduced blood flow (vasospasm), and decreased oxygen delivery to the tissues [47,48]. When CO2 levels are decreased, hemoglobin is more reluctant to release O2, a physiological phenomenon termed the Bohr effect [47,49,50]. Further exacerbating the oxygen supply demand mismatch, hypocapnia increases the demand for O2 at the cellular level, inducing hypoxia. Therefore, a patient experiencing respiratory alkalosis with low PaCO2 levels is also hypoxic at the tissue level. Acute respiratory alkalosis is commonly encountered in cases of mechanical ventilation, asthma, high-altitude pulmonary edema, or lung injury [3,9,51]. Certain medications that stimulate respiratory drive (progesterone, aspirin, beta-2 agonists) can also contribute to CSCRA [22]. Without healthy O2 release to the tissues, patients may present with some symptoms due to poor tissue oxygen delivery and CSCRA, including tingling, lightheadedness, chest tightness, fatigue, and dizziness [52]. Moreover, the reduced blood flow to vascular beds due to vasoconstriction, especially in the cerebral circulation, can detrimentally impact neurologic function [22].

Figure A1.

Illustration of the ventilation-perfusion cycle with reduced blood carbon dioxide. Created in BioRender (biorender.com, accessed on 29 December 2025). Kingsbury, S. (2025).

Appendix B. Nijmegen Questionnaire

The Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ) is administered twice over the course of the Capnic Challenge, first assessing the historical frequency of patient symptoms (Table A1) and then assessing the intensity of the symptoms after the timed breathing portion (Table A2). For the intensity test, the 0–4 scale receives new labels measuring symptom intensity: “None,” “Mild,” “Moderate,” “Severe,” “Very Severe.”

Table A1.

The Standard NQ is used to assess frequency of historical symptoms. The scale is the frequency of symptoms from Never (maximum negative) to Very Often (maximum positive).

Table A1.

The Standard NQ is used to assess frequency of historical symptoms. The scale is the frequency of symptoms from Never (maximum negative) to Very Often (maximum positive).

| Never—0 | Rarely—1 | Sometimes—2 | Often—3 | Very Often—4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest pain | |||||

| Feeling tense | |||||

| Blurred Vision | |||||

| Dizzy Spells | |||||

| Feeling confused | |||||

| Faster/deeper breathing | |||||

| Short of breath | |||||

| Tight feelings in the chest | |||||

| Bloated feeling in the stomach | |||||

| Tingling fingers | |||||

| Unable to breathe deeply | |||||

| Stiff fingers or arms | |||||

| Tight feelings around the mouth | |||||

| Cold hands or feet | |||||

| Palpitations | |||||

| Feelings of anxiety | |||||

| TOTAL SCORE |

Note: Based on van Dixhoorn and Duivenvoorden (1985) [26].

Table A2.

The Modified NQ is used to assess the intensity of symptoms from provocation testing. The scale is the intensity of symptoms from None (maximum negative) to Very Severe (maximum positive).

Table A2.

The Modified NQ is used to assess the intensity of symptoms from provocation testing. The scale is the intensity of symptoms from None (maximum negative) to Very Severe (maximum positive).

| None—0 | Mild—1 | Moderate—2 | Severe—3 | Very Severe—4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest pain | |||||

| Feeling tense | |||||

| Blurred Vision | |||||

| Dizzy Spells | |||||

| Feeling confused | |||||

| Faster/deeper breathing | |||||

| Short of breath | |||||

| Tight feelings in the chest | |||||

| Bloated feeling in the stomach | |||||

| Tingling fingers | |||||

| Unable to breathe deeply | |||||

| Stiff fingers or arms | |||||

| Tight feelings around the mouth | |||||

| Cold hands or feet | |||||

| Palpitations | |||||

| Feelings of anxiety | |||||

| TOTAL SCORE |

Note: Modified from van Dixhoorn and Duivenvoorden (1985) [26].

References

- Bösner, S.; Schwarm, S.; Grevenrath, P.; Schmidt, L.; Hörner, K.; Beidatsch, D.; Bergmann, M.; Viniol, A.; Becker, A.; Haasenritter, J. Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom dizziness in primary care—A systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.; Kandle, P.; Murray, I.; Dhamoon, A. Physiology, Oxyhemoglobin Dissociation Curve. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Laffey, J.; Kavanagh, B. Hypocapnia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippalapalli, J.; Lumb, A. The respiratory system and acid-base disorder. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 23, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanek, J. The Contribution of Aerospace Medicine Specialty Expertise in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache Disorders with Concomitant Clinically Symptomatic Dyscapnia (Respiratory Alkalosis/Acidosis). Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, R.; Stacey, R.; Niven, R.; Fowler, S. Dysfunctional breathing: A review of the literature and proposal for classification. Eur. Resp. Rev. 2016, 25, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, A.; Bell, R. The effect of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on the blood flow through the cerebral cortex. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1963, 26, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.; Goodwin, J. Effect of aging on respiratory system physiology and immunology. Clin. Interv. Aging 2006, 1, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crystal, G. Carbon dioxide and the heart: Physiology and clinical implications. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 121, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, F. Effects of Low and High Oxygen Tensions and Related Respiratory Conditions on Visual Performance: A Literature Review; United States Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory: Columbus, GA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, R.; Hackett, P.; Oelz, O.; Bärtsch, P.; Luks, A.; MacInnis, M.; Baillie, J.; The Lake Louise AMS Score Consensus Committee. The 2018 Lake Louise acute mountain sickness score. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2018, 19, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Pianosi, P. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: A respiratory disorder? Current Res. Physiol. 2021, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Systrom, D.; Witte, A.; Marciano, S. Orthostatic intolerance with tachycardia (postural tachycardia syndrome) and without hypocapnic cerebral hypoperfusion) represent a spectrum of the same disorder. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1476918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassar, M.; Holzmann, M. The retrospective chart review: Important methodological considerations. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, D.; Patil, S.; Zubair, M.; Keenaghan, M. Arterial Blood Gas. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni, L.; Pesenti, A.; Matthay, M. Understanding blood gas analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, E.; Sanvictores, T.; Sharma, S. Physiology, Acid Base Balance. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fencl, V.; Leith, D. Stewart’s quantitative acid-base chemistry: Applications in biology and medicine. Respir. Physiol. 1993, 91, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P. Modern quantitative acid-base chemistry. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1983, 61, 1444–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.; Clegg, D. Mixed acid-base disturbances: Core curriculum 2025. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2025, 86, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanek, J.; Cevette, M.; Pradhan, G.; Kleindienst, S.; Bogle, J.; Blue, R.; Breznak, K. Methods and Materials for Treating Hypocapnia. US Patent US20200121875A1, 20 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, B. Evaluation and treatment of respiratory alkalosis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 60, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.; Clegg, D. Respiratory acidosis and respiratory alkalosis: Core curriculum 2023. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 82, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennari, F.J.; Goldstein, M.B.; Schwartz, W.B. The nature of the renal adaptation to chronic hypocapnia. J. Clin. Investig. 1972, 51, 1722–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, P.; Colla, P.; Folgering, H. Een vragenlijst voor hyperventilatieklachten [A questionnaire for hyperventilation syndrome]. De Psycholoog 1983, 18, 573–577. [Google Scholar]

- van Dixhoorn, J.; Duivenvoorden, H. Efficacy of Nijmegen Questionnaire in recognition of the hyperventilation syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985, 29, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dixhoorn, J.; Folgering, H. The Nijmegen Questionnaire and dysfunctional breathing. ERJ Open Res. 2015, 1, 00001-2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresseleers, J.; Van Diest, I.; De Peuter, S.; Verhamme, P.; Van den Bergh, O. Feeling Lightheaded: The Role of Cerebral Blood Flow. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Iscoe, S.; Fedorko, L.; Duffin, J. Rapid elimination of CO through the lungs: Coming full circle 100 years on. Exp. Physiol. 2011, 96, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanti, A.; Szerlip, H. Acid-base disorders in the critically ill patient. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyukhin, I.; Patschan, S.; Ritter, O.; Patschan, D. Etiology and management of acute metabolic acidosis: An update. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2020, 45, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, G.; Laffey, J.; Kavanagh, B. Bench-to-Bedside Review: Carbon Dioxide. Crit. Care 2010, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatopoulou, E.P.; Skordilis, E.K.; Georgoudis, G.; Haniotou, A.; Evangelodimou, A.; Fildissis, G.; Katsoulas, T.; Kalagiakos, P. Hyperventilation in asthma: A validation study of the Nijmegen Questionnaire—NQ. J. Asthma 2014, 51, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, A.; Morgenshtern, K.; Culbertson, C.; Wang, L.; Depold Hohler, A. A survey-based analysis of symptoms in patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS). Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2015, 28, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, C.; Floyd, S.; Lee, K.; Warwick, G.; James, S.; Gall, N.; Rafferty, G. Breathlessness and dysfunctional breathing in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): The impact of a physiotherapy intervention. Auton. Neurosci. 2020, 223, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Hur, H.; Park, B.; Park, H. Psychosocial factors associated with dizziness and chronic dizziness: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkirov, S.; Stone, J.; Holle-Lee, D. Treatment of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) and related disorders. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2018, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, L.C. The syndrome of habitual chronic hyperventilation. Rec. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 3, 196–229. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, M. The breathing conundrum—Interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.; Millar, T.; Larsen, D.; Kryger, M. Irregular breathing during sleep in patients with panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livermore, N.; Sharpe, L.; McKenzie, D. Panic attacks and panic disorder in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A cognitive behavioral perspective. Respir. Med. 2010, 104, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, A. Panic disorder is closely associated with respiratory obstructive illness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honaker, J. Anxious … and Off Balance: Which comes first? Dizziness and falls? Or the fear of either happening? Anxiety and balance problems can become a feedback loop. ASHA Lead. 2018, 23, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, H.; Wada, M.; Saitoh, J.; Sunaga, N.; Nagai, M. The effect of anxiety on postural control in humans depends on visual information processing. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 364, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevette, M.; Puetz, B.; Marion, M.; Wertz, M.; Muenter, M. Aphysiologic performance on dynamic posturography. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 1995, 112, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Zuccarello, M.; Rapoport, R. pCO2 and pH regulation of cerebral blood flow. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F. Red blood cell p, the Bohr effect, and other oxygenation-linked phenomena in blood O2 and CO2 transport. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2004, 182, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, L.; Rahn, H. Gas stores of the body and the unsteady state. J. Appl. Physiol. 1955, 7, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohr, C.; Hasselbalch, K.; Krogh, A. Ueber einen in biologischer Beziehung wichtigen Einfluss, den die Kohlensäurespannung des Blutes auf dessen Sauerstoffbindung übt. Skand. Arch. Für Physiol. 1904, 16, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaja, M.; Crespi, T.; Guazzi, M.; Vandegriff, K. Oxygen transport in blood at high altitude: Role of the hemoglobin-oxygen affinity and impact of the phenomena related to hemoglobin allosterism and red cell function. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 90, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogossian, E.; Peluso, L.; Creteur, J.; Taccone, F. Hyperventilation in Adult TBI Patients: How to Approach It? Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 580859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raichle, M.; Plum, A. Hyperventilation and Cerebral Blood Flow. Stroke 1972, 3, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.