Abstract

In the production of clad rolled plates from asymmetric sandwich-type slab for pipeline applications, achieving both target mechanical properties and high geometric flatness remains a critical challenge due to differential thermal stresses between the dissimilar steel layers during accelerated cooling. This study aims to develop an optimal cooling schedule for a 25 mm thick clad plate, comprising a X70-grade steel base layer and an AISI 316L cladding, to ensure required strength and minimal bending. A comprehensive approach was employed, integrating a 3D finite element model (Ansys) for simulating thermoelastic stresses with a CatBoost machine learning model trained on industrial data to predict heat transfer coefficients accurately. A parametric analysis of cooling strategies was conducted. Results showed that a standard cooling strategy caused unacceptable bending of plate after cooling exceeding 130 mm. An optimized strategy featuring delayed activation of the lower cooling headers (on the cladding side) created a compensating thermoelastic moment, successfully reducing bending to approximately 20 mm while maintaining the base layer’s requisite mechanical properties. The findings validate the efficacy of the combined FEM-machine learning methodology and propose a viable, industrially implementable cooling strategy for high-quality clad plate production.

1. Introduction

Modern requirements for pipe products for main gas and oil pipelines mandate high strength, cold resistance, and operational reliability. Rolled products made of X70 strength class pipe steel, as the primary material for manufacturing such pipes, must combine the required set of mechanical properties with high geometric accuracy, particularly flatness [1,2,3,4,5]. This task becomes especially critical in the production of clad rolled products, where during accelerated cooling after controlled rolling it is necessary to simultaneously achieve two objectives: forming the specified microstructure of the base layer, which ensures mechanical properties (strength, toughness), and minimizing residual stresses leading to flatness defects.

The relevance of solving the problem of simultaneously achieving the required mechanical properties and high flatness for clad rolled products is driven by several factors. Firstly, the processes occurring during the accelerated cooling stage after controlled rolling are decisive for forming the final structure and properties of the steel. Secondly, it is precisely during cooling that significant thermal stresses arise, which, upon relaxation, lead to various forms of plate bending. For clad rolled products, this problem is exacerbated by the presence of layers with different thermophysical and mechanical characteristics, creating additional preconditions for the development of residual stresses and deformations.

The main difficulty in designing cooling schedules lies in the need to simultaneously achieve contradictory goals: on one hand, it is necessary to ensure the required kinetics of phase transformations to obtain an optimal structural state guaranteeing the mechanical properties of the base layer corresponding to strength class X70, and on the other hand, to minimize temperature gradients and the resulting thermoelastic stresses that lead to flatness defects.

Traditional approaches to solving this problem are generally based on the empirical selection of cooling schedules and their subsequent adjustment based on industrial trial results. However, this path is resource-intensive, time-consuming, and does not always lead to a global optimum. Mathematical modeling of cooling processes represents a powerful tool, allowing for the virtual analysis of many scenarios and the identification of optimal control parameters.

Contemporary work in modeling thermomechanical processing of rolled products can be conditionally divided into several directions: Studies [1,2] have investigated in detail the influence of cooling rate and finishing rolling temperature on the structure formation of low-alloy pipe steels. It has been shown that achieving X70-grade properties relies on a carefully engineered, fine-grained multi-phase microstructure. This is typically a matrix of fine polygonal or acicular ferrite, strengthened by a dispersion of bainite and minor phases like pearlite or M-A constituents or a predominantly bainitic microstructure. The fine grain size provides high toughness, while the bainite and carbonitride precipitates contribute to the required strength. Research [6,7] is dedicated to analyzing the origin of residual stresses during cooling of rolled products. The authors demonstrate that non-uniform cooling across the plate width and length is the primary cause of flatness defects such as crescent shape and waviness. Work [8] presents a model linking the kinetics of phase transformations with the generation of thermal and structural stresses. The authors emphasize the significant contribution of volumetric changes during phase transformations (especially during the decomposition of austenite into ferrite and bainite) to the overall stress field. In [9,10,11,12,13], an approach is proposed for optimizing cooling schedules considering both properties and plate shape, but for non-clad rolled products.

The primary cause of bending in clad plates during cooling is the difference in Thermal Expansion Coefficient (TEC) between the constituent materials. During cooling from the rolling temperature, each layer attempts to contract according to its own TEC, but the metallurgical bond forces them to contract together. This constraint generates internal stress that, if unbalanced, causes bending.

For example, stainless steel cladding typically has a higher TEC than carbon steel backing. During cooling, the stainless layer attempts to contract more than the carbon steel. However, the bond between them constrains this differential contraction, placing the stainless layer in residual tension and the carbon steel in residual compression. This stress imbalance creates a bending moment that curves the plate toward the higher-TEC material (the cladding). This mismatch strain can be expressed as below:

where

= CTE of materials 1 and 2 [1/°C]

= plate temperature [°C]

= room temperature [°C]

Assuming elastic behavior and plane sections of plate, force equilibrium will be expressed as

where (width × thickness)

Stress in each layer:

Simplified expression for radius of curvature for thin cladding (considering t1 ≪ t2):

where

= Radius of curvature [mm]

= Thickness of layers 1 and 2

= Young’s modulus

The above formulas give a general principle of clad plates bending due to difference in TEC.

Despite significant progress in the field of mathematical modeling, the issue of the comprehensive calculation of cooling schedules for clad rolled products with a base layer of X70 class pipe steels remains insufficiently studied. During the literature review, only one work [14] dedicated to cooling clad rolled products was found.

The aim of this work is to develop an optimal cooling schedule for clad rolled products that ensures the required mechanical properties of the base layer and satisfactory flatness of the finished product.

To achieve this aim, the following tasks are addressed in this work:

- Development of a 3D FEM model of the accelerated cooling process for a clad plate.

- Validation of the developed model based on comparing calculation results with industrial data.

- Conducting a parametric analysis to identify key technological parameters (water flow by zones, transportation speed, start cooling temperature) that have the greatest influence on flatness and mechanical properties.

- Formulation, based on the analysis of calculated data, of recommendations for optimal cooling schedules for clad rolled products ensuring compliance with standard requirements for mechanical properties at minimal bending.

2. Materials and Methods

The material of the base layer is a pipeline steel grade API 5l X70, and the material of the cladding layer is steel grade AISI 316L. The chemical composition of the steels was measured on an optical emission spectrometer “ARL-4460” (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ecublens, Switzerland) using atomic emission spectral analysis and is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the studied steel grades (-*—not defined strictly in standard).

An asymmetric gas-filled sandwich slab was used as the initial workpiece, in which the stainless steel was welded to the base layer on one side only (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An example of sandwich slab used for production of clad plates.

The Ansys 2021 R1 software suite was used as a simulation environment based on the finite element method. The model was adapted based on data from an industrial 5000 heavy plate mill.

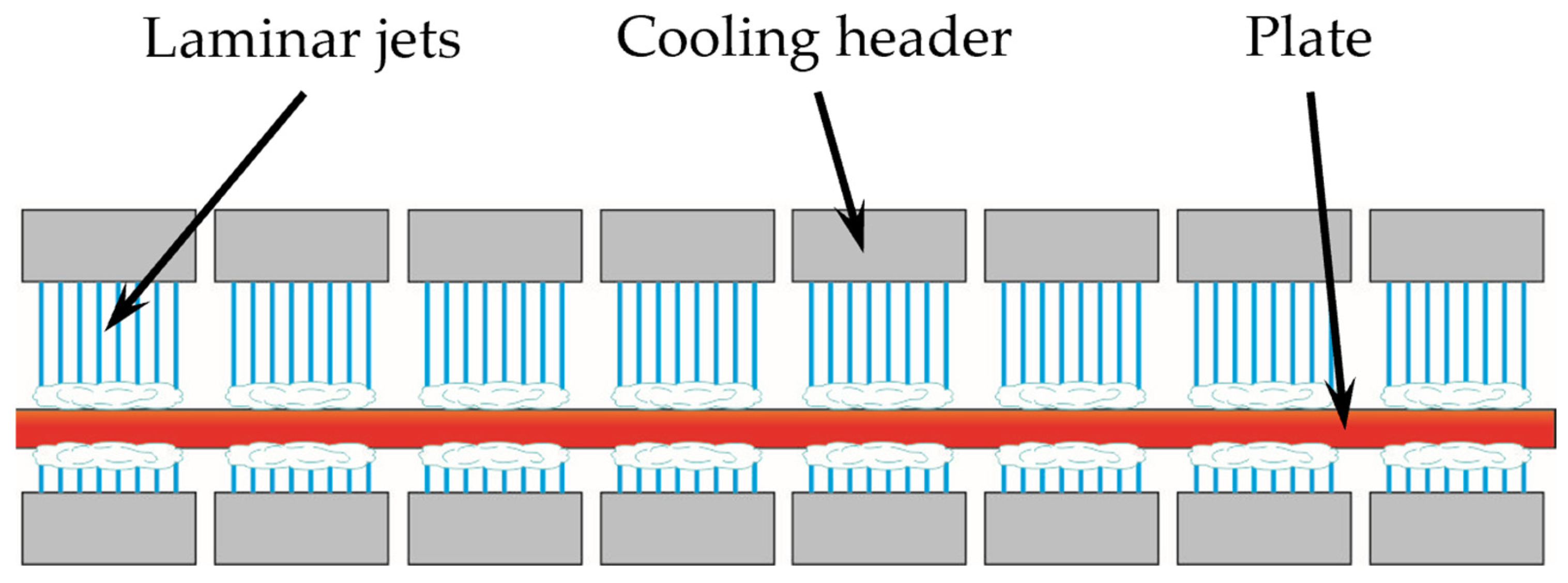

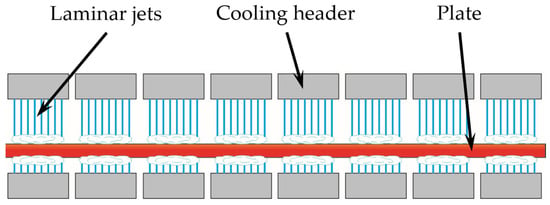

The plate cooling process is carried out in an accelerated cooling unit (ACU), which consists of 72 headers arranged above and below (36 each, respectively). The unit is schematically shown in Figure 2. A header is a plate with over 1000 holes drilled in it.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the cooling unit.

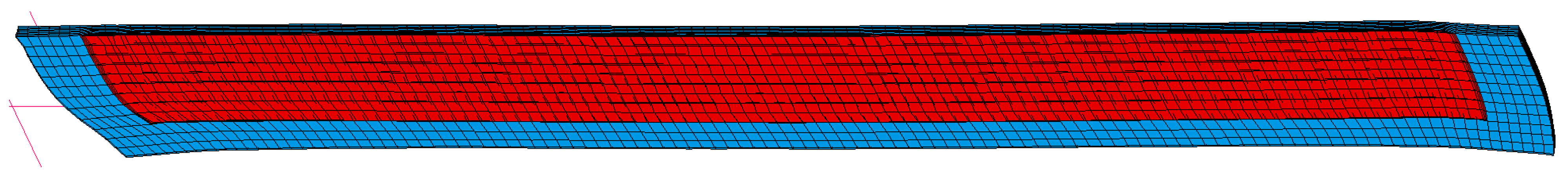

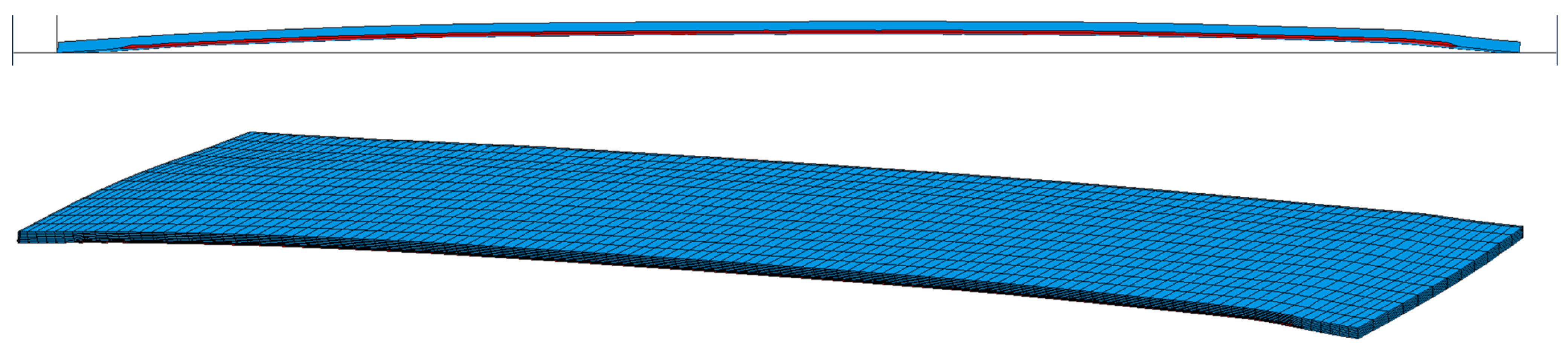

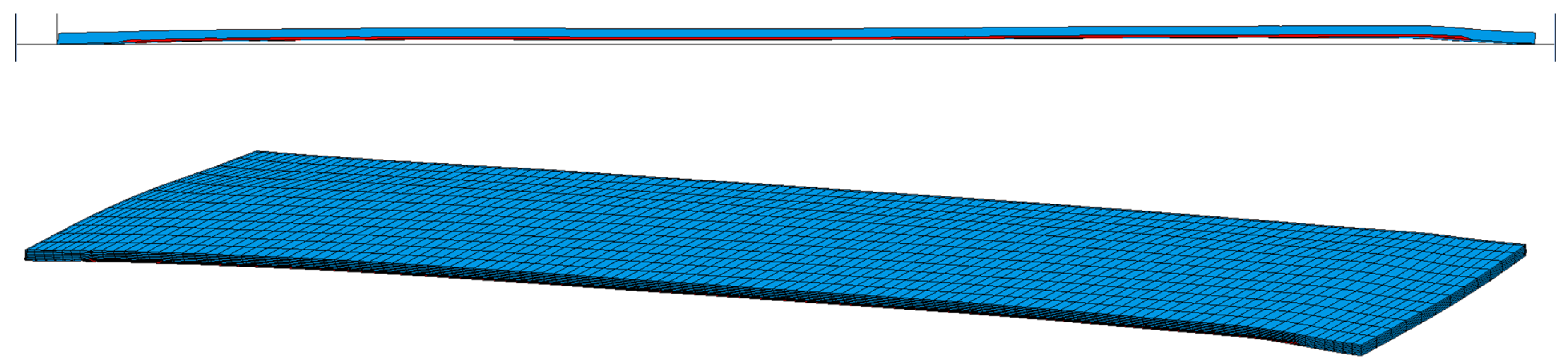

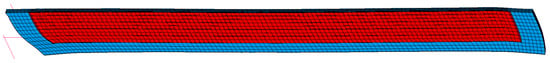

The initial state of the modeled body (plate clad rolled product) was obtained based on other work by the authors [15], where the process of rolling clad plates was modeled. The plate is positioned on a plane simulating the roller table. The base layer was divided into 11,300 eight-node elements, and the cladding layer into 2800. The material model is elastic–plastic. Longitudinal symmetry was used; the general view of the model from the cladding layer side is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

General view of the FEM model. Red color—clad layer, blue color—base layer.

Cooling schedules for a 25 mm thick rolled product with a 3 mm thick cladding layer, 14 m long and 3 m wide, were investigated. The plastic properties of the steel were specified based on tests conducted on a Gleeble unit (Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA), also reported in works [7,15]. The thermophysical properties of the steels (heat capacity, thermal conductivity, density, expansion coefficient, elastic modulus) were specified in accordance with [16,17,18].

Boundary conditions of the third kind were used (6).

where is the thermal conductivity coefficient, ρ is the density, c is the heat capacity of the metal, t is time, is temperature, is the ambient temperature, is the heat transfer coefficient, and G is the boundary of the considered object.

To accurately predict the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) during accelerated cooling, a hybrid approach was employed, combining a specialized 2D Finite Element Method (FEM) model (detailed description can be found in [19]) with a CatBoost gradient boosting machine learning model.

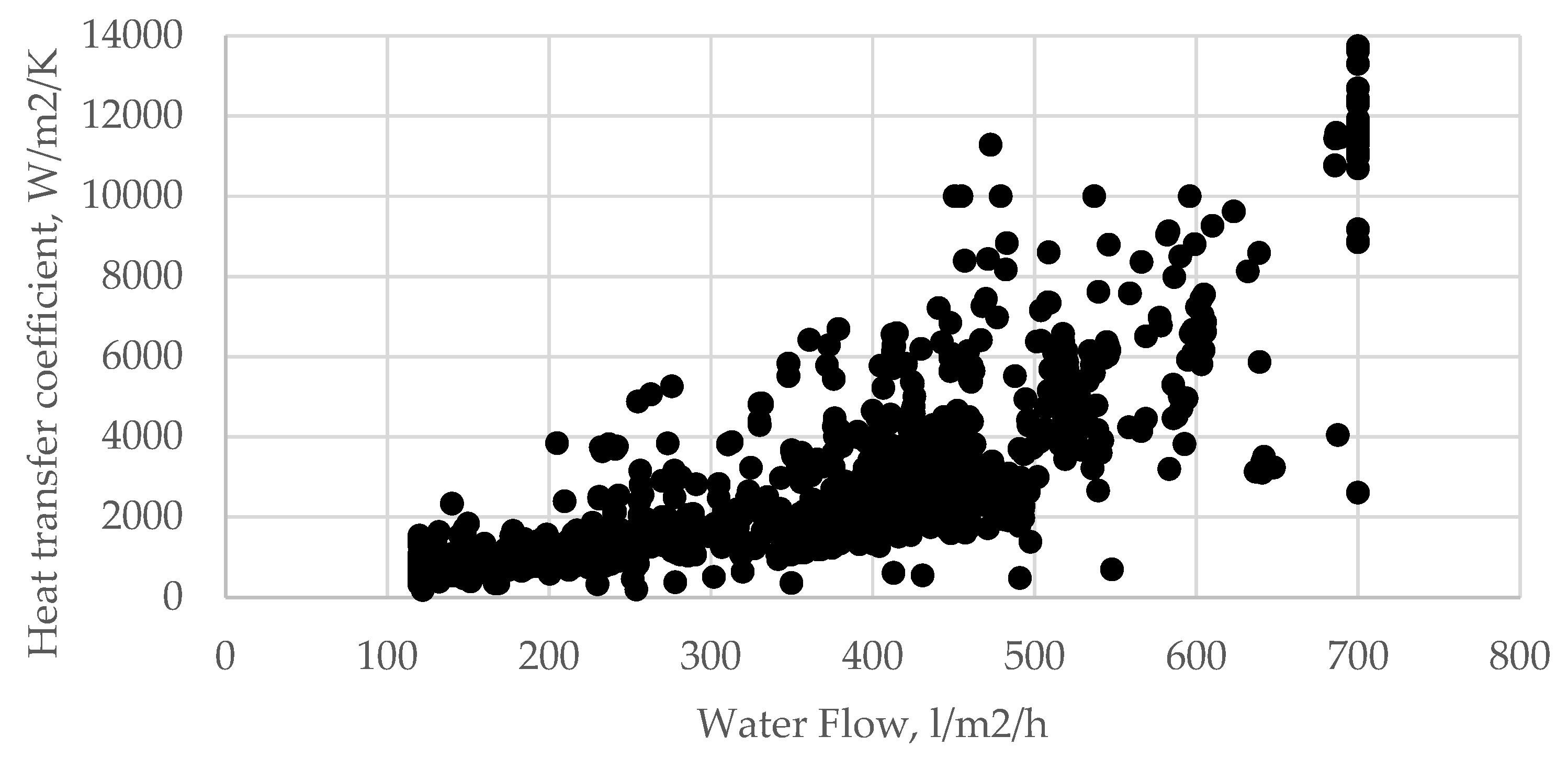

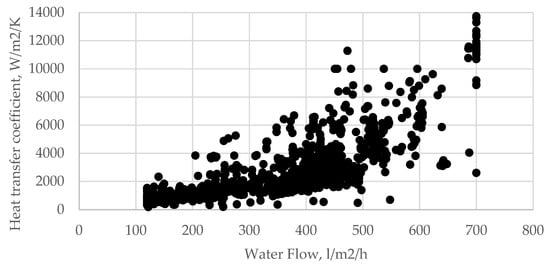

First, a dataset of effective HTC values was constructed. Using historical industrial records for over 10,000 rolled plates (comprising various steel grades), the 2D FEM model was applied inversely. For each production run, the model—initialized with the recorded geometric parameters, initial temperature, and cooling unit settings—was run iteratively. The HTC was adjusted as a boundary condition until the model’s predicted final plate temperature converged with the measured industrial value (dependence of HTC vs. cooling unit flow rate can be seen on Figure 4). This process yielded a dataset where each record paired a set of process parameters (e.g., water flow, plate dimensions, transportation speed, chemical composition) with a corresponding, model-calibrated HTC value. After data cleaning and balancing (e.g., removing pyrometer errors), the final dataset contained 1849 records, with separate subsets for plates below and above 30 mm in thickness. This dataset was independent of the specific clad plate cases analyzed in the present study.

Figure 4.

Dependence of the heat transfer coefficient on flow rate.

Dataset covers following plate dimensions:

- Plate thickness: 10–110 mm;

- Width: up to 3 m;

- Length: up to 14 m;

- Various steel grades (steels for construction, petrochemical and shipbuilding industries, heavy machinery, API grades, stainless steels, and others).

Subsequently, this dataset was used to train and select an ML model for HTC prediction. Several algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, CatBoost, LightGBM, XGBoost) were evaluated using an 80/20 train/test split. Hyperparameter optimization was performed via GridSearchCV. The CatBoost model achieved the best performance, with optimal parameters: ‘loss_function’: ‘RMSE’, ‘l2_leaf_reg’: 10, ‘depth’: 6, ‘learning_rate’: 0.1, ‘max_leaves’: 64}. Feature importance analysis identified plate thickness, finishing cooling temperature, water flow rate, length, and transportation speed as the most significant predictors. The final model demonstrated high accuracy, with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.89 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 100.1 W/m2·K for plates under 30 mm thickness. When deployed within the FEM framework, this ML-predicted HTC enabled temperature predictions where 98% of test cases fell within ±35 °C of the target value (92% within ±20 °C).

Standard HTC estimation techniques (constant HTC, semi-empirical correlations, or calibrated tables) are inherently limited because they reduce the prediction to a single value per waterflow rate. Figure 4 demonstrates that in practice, HTC varies considerably for a given flow rate due to the combined effects of plate geometry (especially flatness), surface condition, thermal history, transportation speed, and steel chemistry. The ML model overcomes this limitation by explicitly accounting for these additional factors, resulting in a prediction accuracy that surpasses that of traditional flow-rate-based approaches.

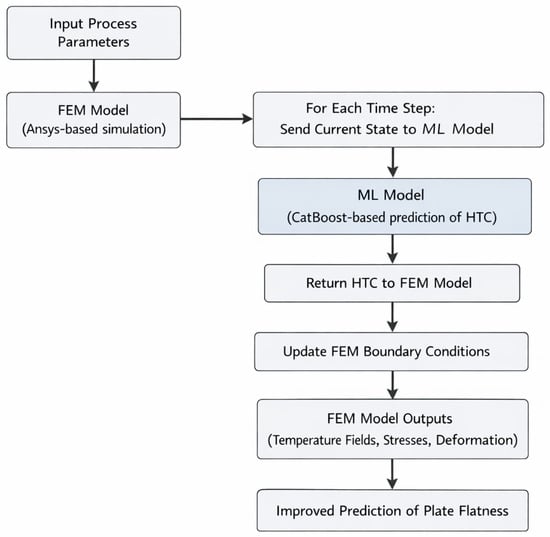

The integrated FEM-ML modeling framework operates as follows (Figure 5):

FEM Model Role (Ansys based):

- The FEM model simulates the thermo-mechanical behavior of the clad plate during accelerated cooling.

- It solves the transient heat conduction equation with temperature-dependent material properties and boundary conditions.

- The FEM model outputs temperature fields, thermal stresses, and plate deformation.

ML Model Role (CatBoost-based):

- The ML model predicts the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) at the plate surface during water cooling.

- HTC is highly nonlinear and depends on multiple factors: water flow rate, plate surface temperature, plate thickness, transportation speed, and steel grade.

- The ML model was trained on industrial datasets (>10,000 plates) to learn the relationship between process parameters and HTC.

Integration Mechanism:

- The FEM model uses tables to calculate the ML-predicted HTC at each time step based on current surface temperature and cooling parameters.

- This dynamic HTC is used in the FEM boundary conditions, replacing constant or simplified empirical HTC values.

- The updated HTC improves the accuracy of temperature and stress predictions, which in turn enhances the prediction of plate flatness.

Figure 5.

Models’ logic flowchart.

Figure 5.

Models’ logic flowchart.

To simulate the movement of the plate through the cooling unit, a pusher in the form of a plane with a linear speed corresponding to the industrial case was used. Boundary conditions were described as a function of the X coordinate. For air, the heat transfer coefficient was assumed to be 20 W/m2·K. Boundary conditions for radiative heat exchange with an emissivity coefficient of 0.8 were also set.

The initial plate temperature was set at 850 °C. According to industrial data, the final cooling temperature should be approximately 400 °C.

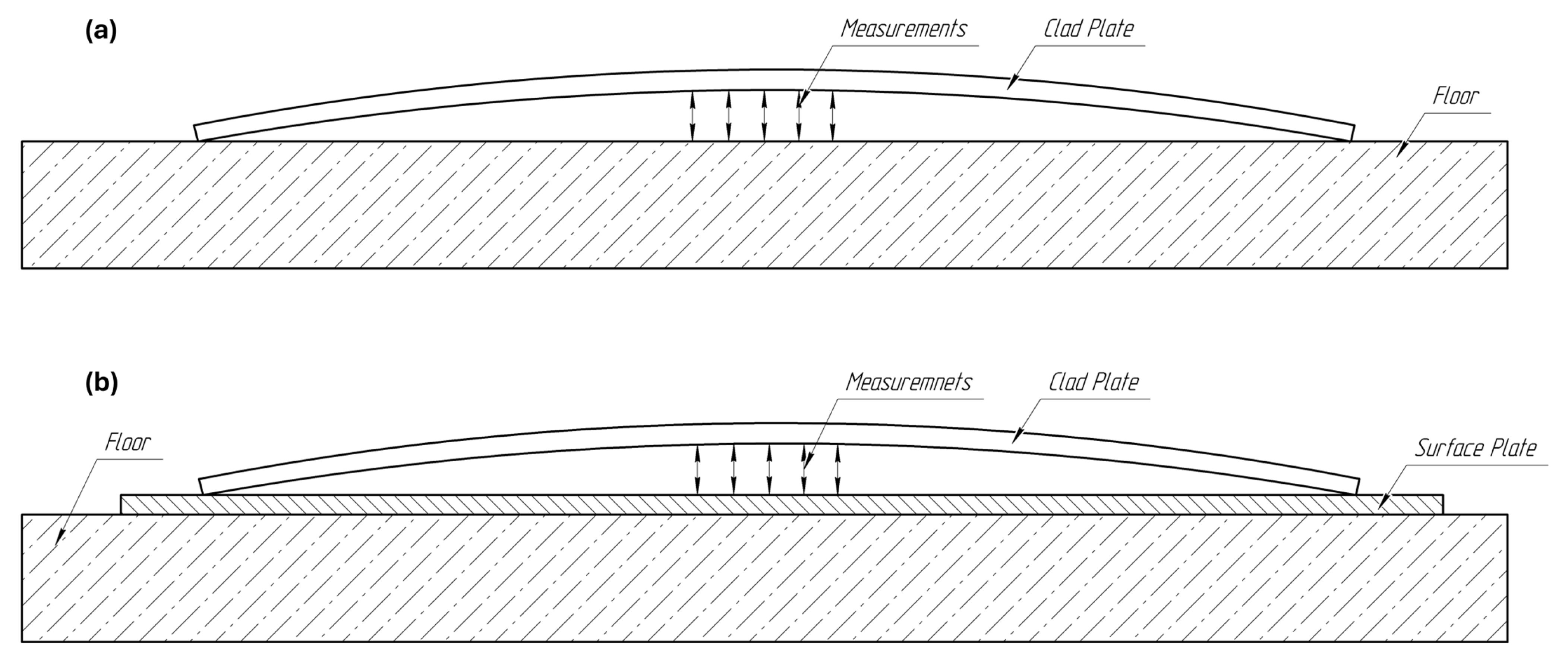

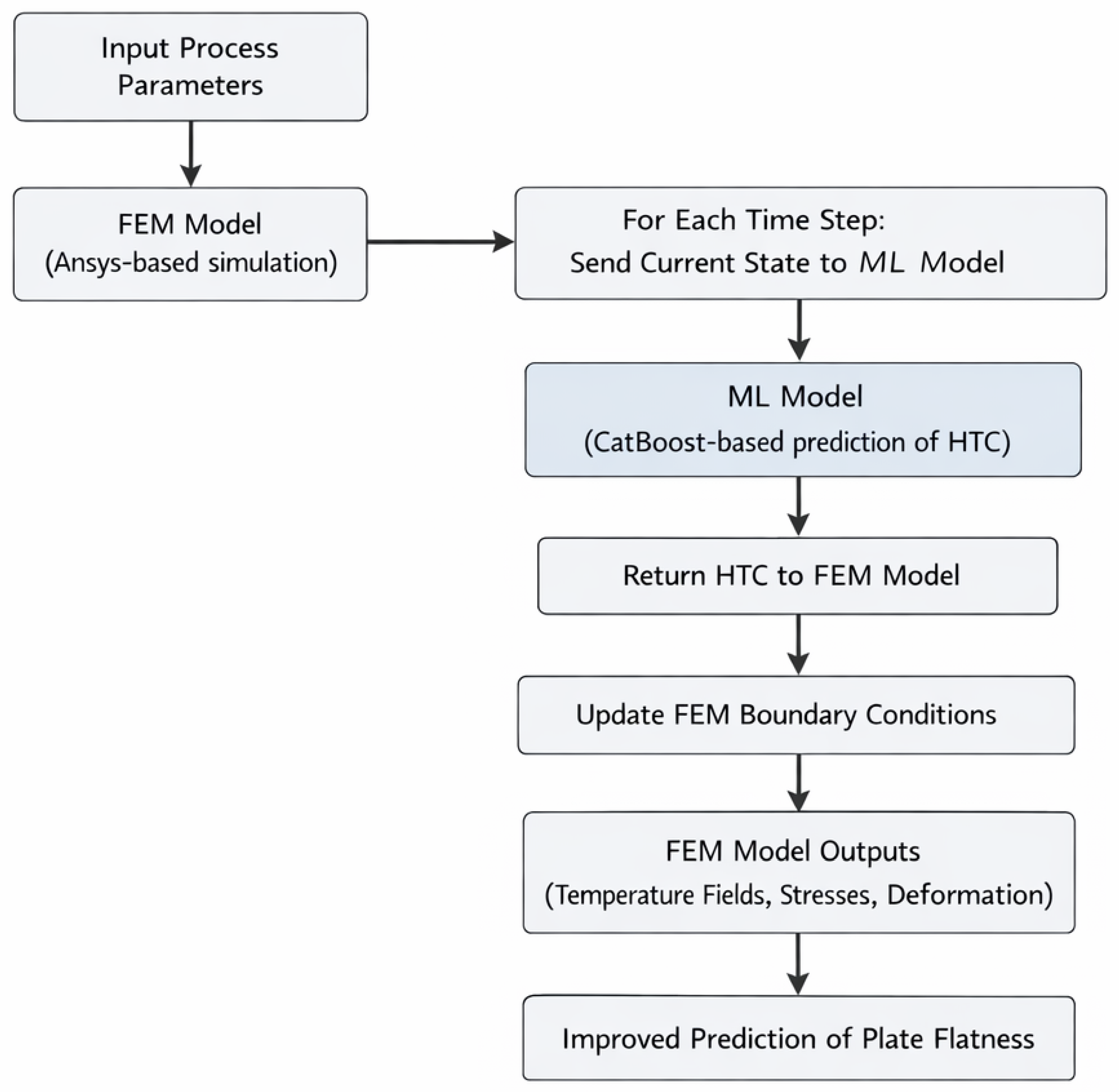

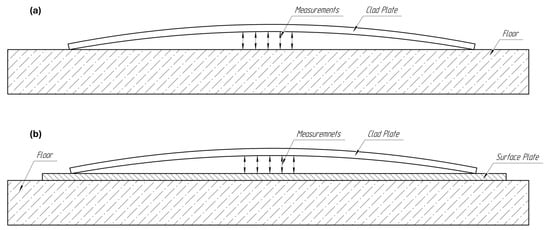

In both laboratory (Figure 6a) and industrial (Figure 6b) experiments, plate bending measurements were conducted using a ruler with a 90-degree angle side to measure the gap between the plate surface and the reference plane. For the laboratory experiment, the plate was placed on a concrete floor, and multiple measurements were taken at different locations to determine the maximum bending value. In the industrial case, a more precise surface plate was used as the reference plane to ensure greater accuracy, with measurements performed similarly to identify the maximum deflection. Measurement tolerances were estimated based on the reference surface flatness. For the laboratory case, where the plate was placed directly on the uneven concrete floor, the measurement tolerance is estimated at ±1 mm due to potential surface irregularities. For the industrial case, where a precision surface plate was used, the tolerance is significantly tighter, but the additional deflection across width yields estimated tolerance ±10 mm (estimated according to results obtained by modeling of industrial case).

Figure 6.

Plate bending measurement methods, (a)—laboratory case, (b)—industrial case.

3. Results

3.1. Model Verification

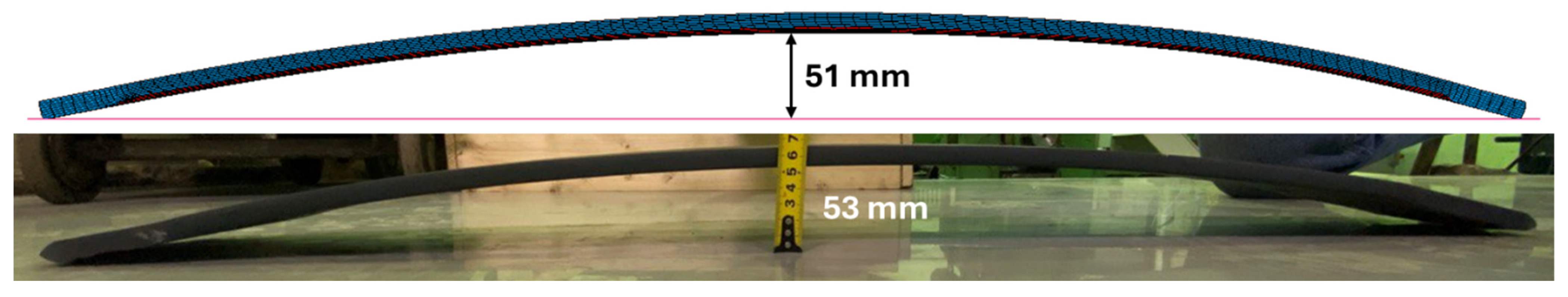

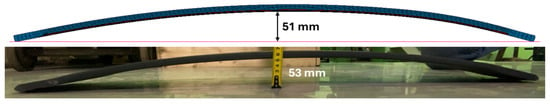

The model was validated against the results of laboratory experiments on strips 1000 mm long, 120 mm wide, and 12 mm thick with a 2 mm cladding layer, as well as an industrial case of rolling a 2 m wide plate 6 m long, and 110 mm thick with a 5 mm cladding layer. The material properties and model parameters were the same as those described earlier in the article. The laboratory sample was rolled from an initial thickness of 80 mm to a final thickness of 12 mm in 10 passes, followed by accelerated cooling to a temperature of approximately 500 °C, after which the strips were air-cooled. The final bending was 53 mm (Figure 7). The simulation results showed a deflection of 51 mm.

Figure 7.

Comparison of simulation results with industrial results. Simulation results on top, laboratory sample below.

The industrial plate was produced from a 350 mm thick slab using a two-stage rolling schedule and accelerated cooling using a standard schedule to a temperature of approximately 400 °C. High convergence was obtained for the maximum bending value—212 mm compared to ~230 mm in the industrial case. The simulation results and a photograph of the industrial plate on the roller table are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of simulation results with industrial results.

The results obtained allow us to conclude the adequacy of the selected material properties and the determined heat transfer coefficients.

3.2. Modeling Results

In the production of a 25 mm thick plate made of X70 strength class steel, a cooling strategy is used in which the plate is transported at a speed of 1 m/s with water flow rates in the headers of approximately 400 L/m2·h. This, considering Figure 4 and the calculation results of the heat transfer coefficient determination model, yields a value of 2900 W/m2·K. The following variants of cooling strategies were simulated:

- Standard strategy, as described above.

- Strategy with alternating header activation (activating every other header), which may reduce the resulting flatness deviation by equalizing temperature between headers.

- Strategy with delayed activation of the lower headers (on the cladding layer side).This will create a temperature gradient and, consequently, additional stresses in the plate that will restrain it from significant bending.

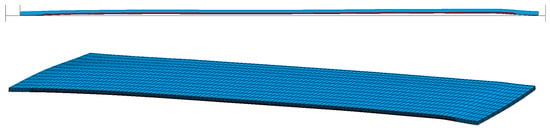

The heat transfer coefficient was adjusted for each case such that the final average plate temperature remained the same. The initial shape of the plate in the middle section is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Initial state of the plate before cooling.

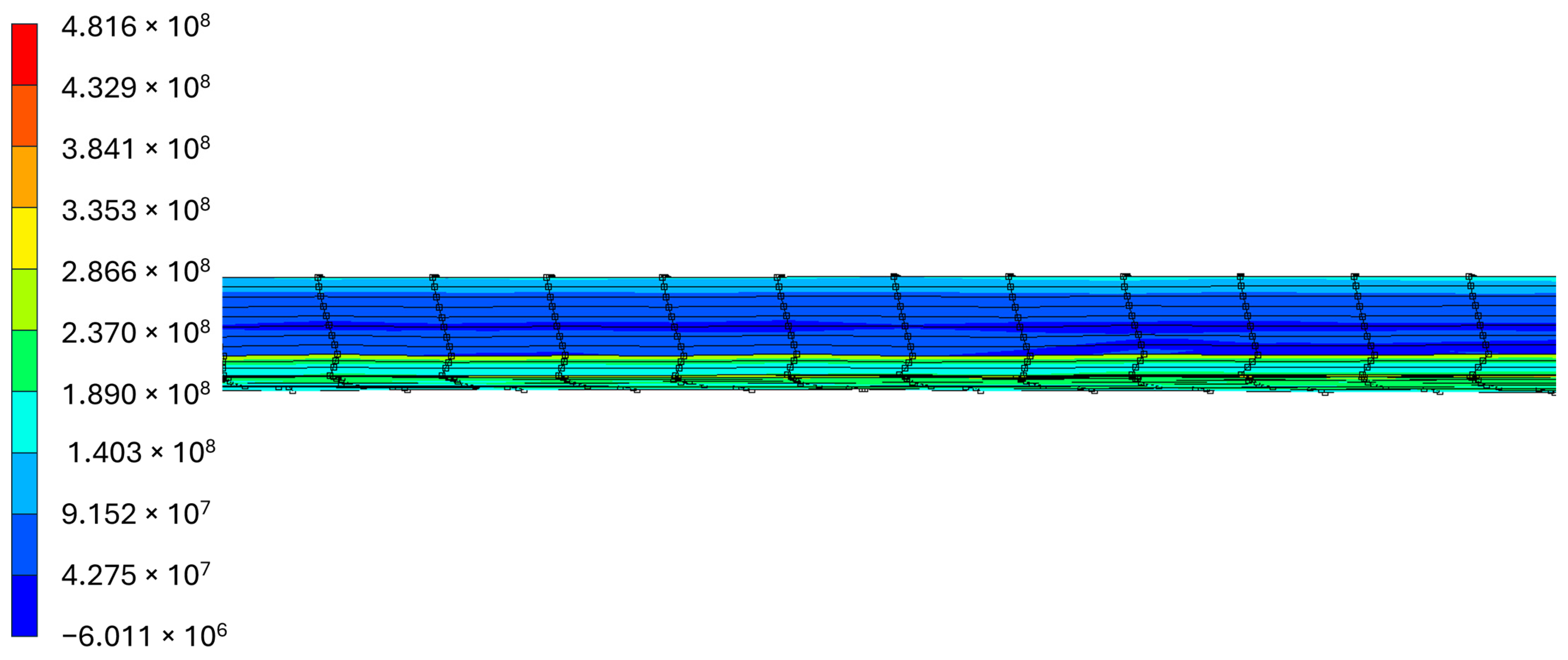

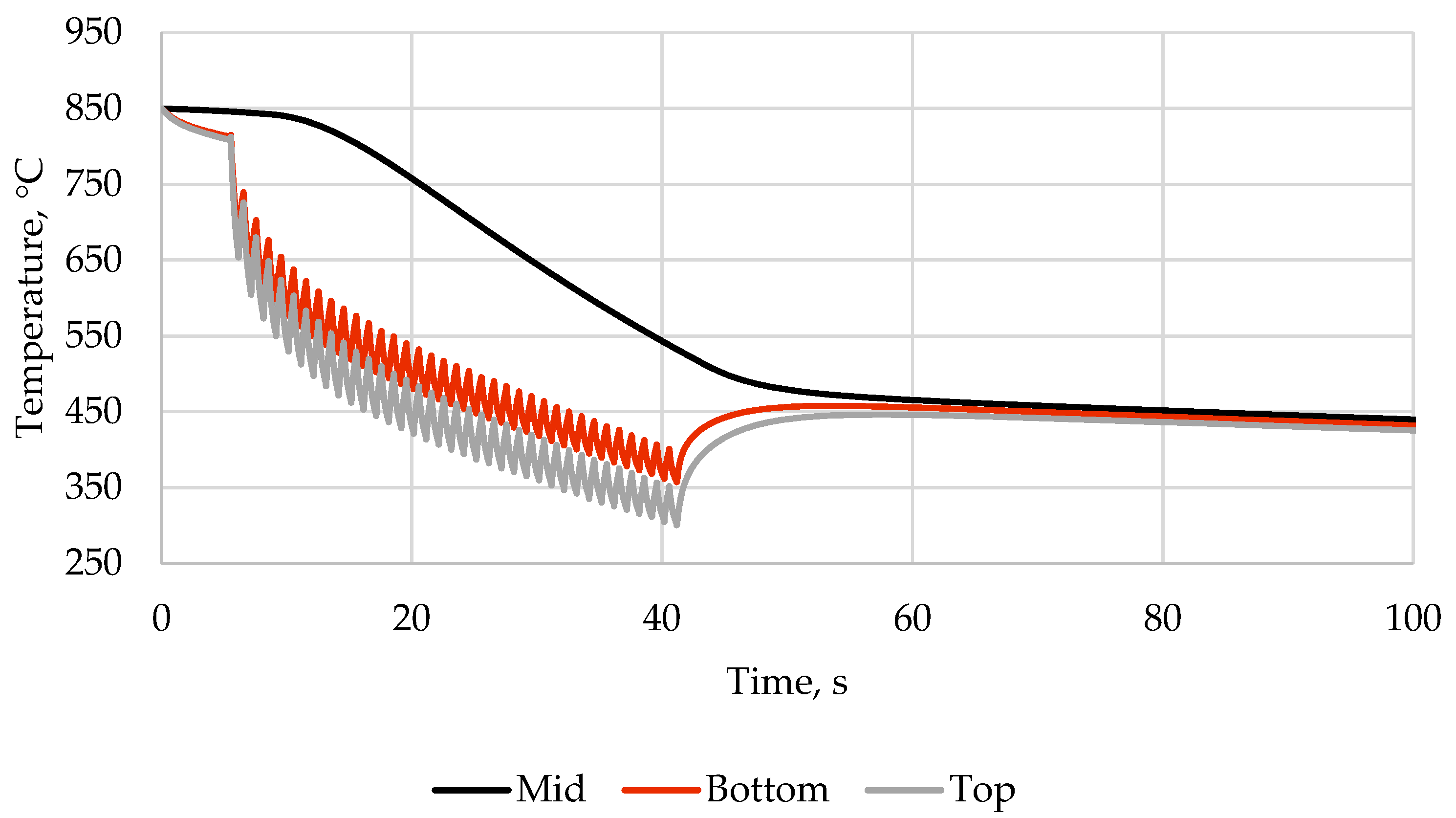

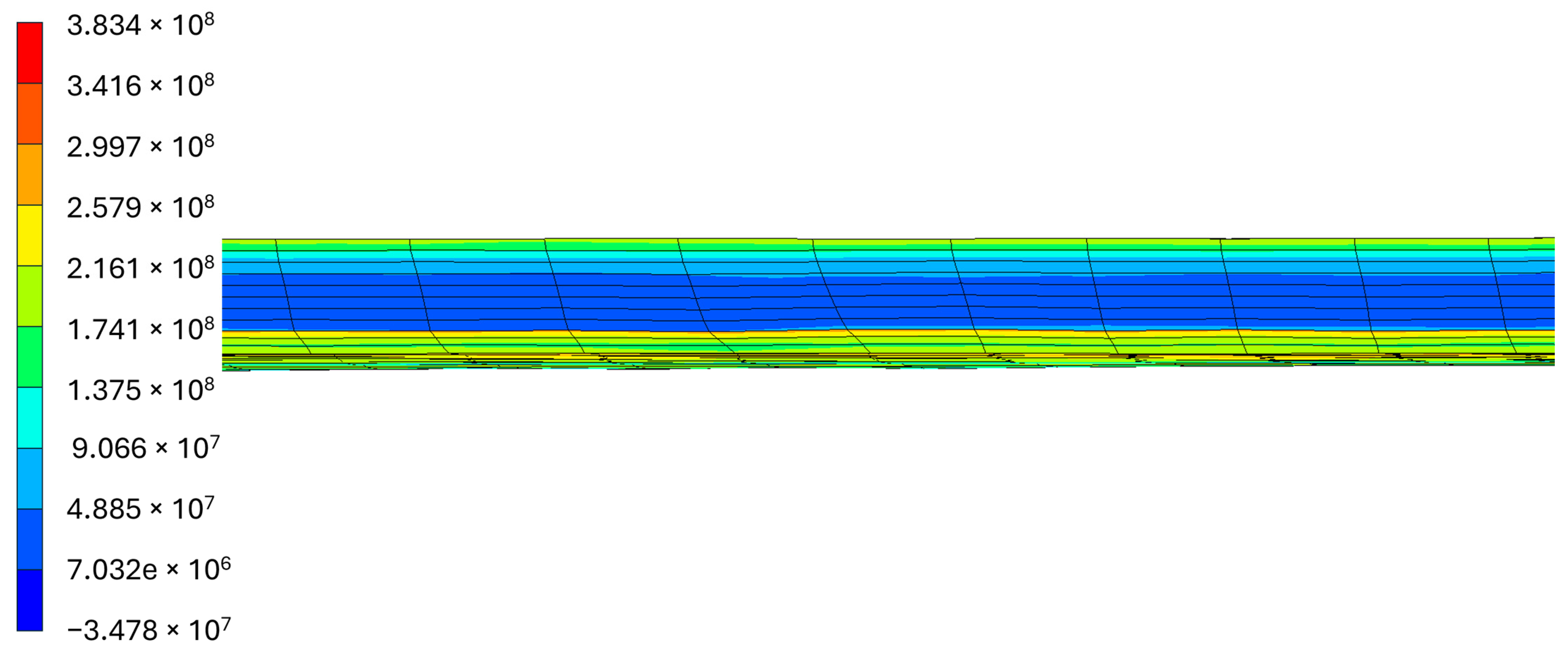

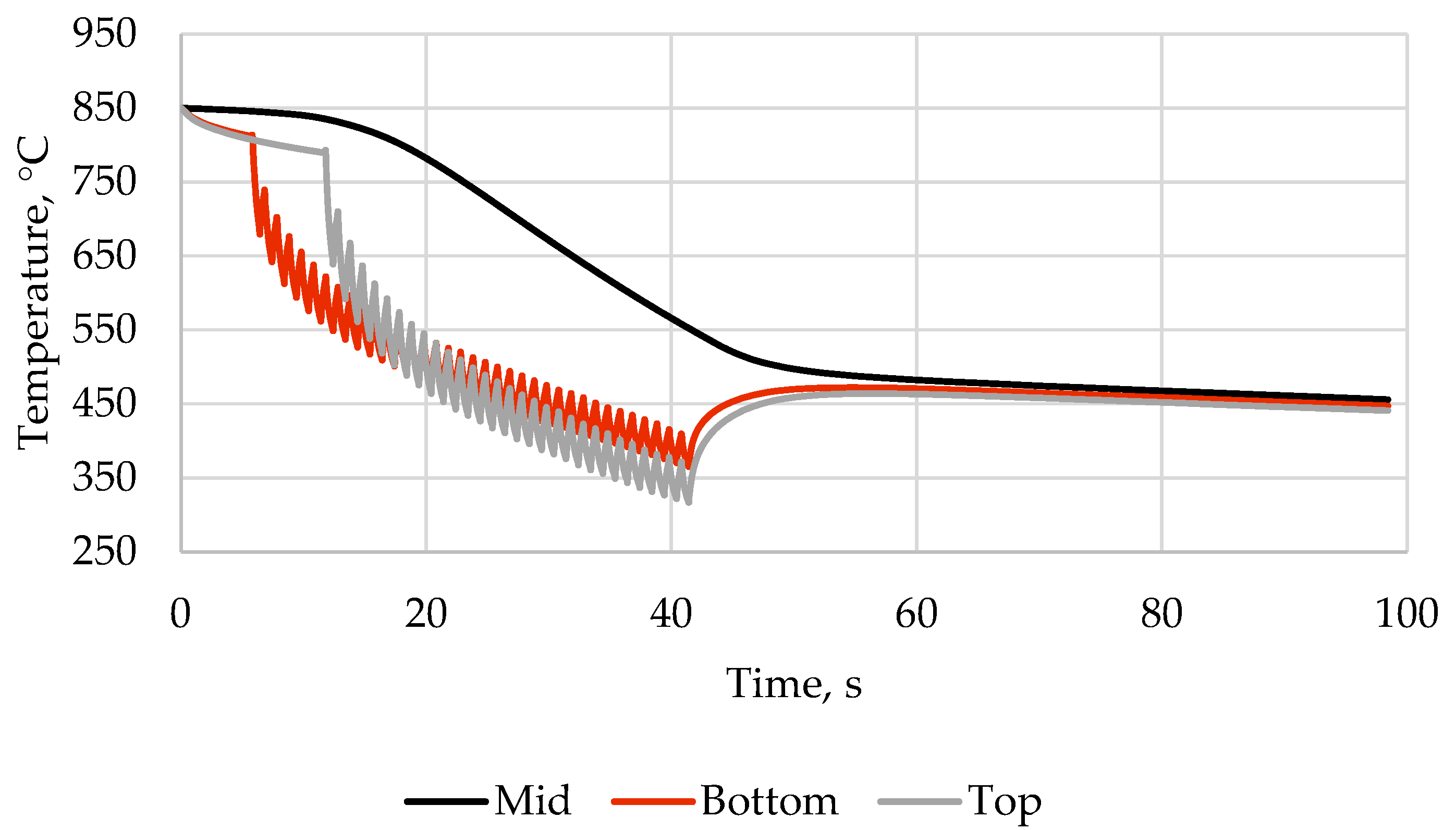

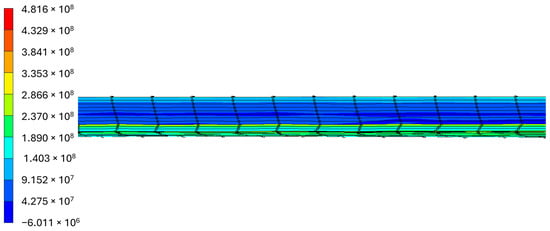

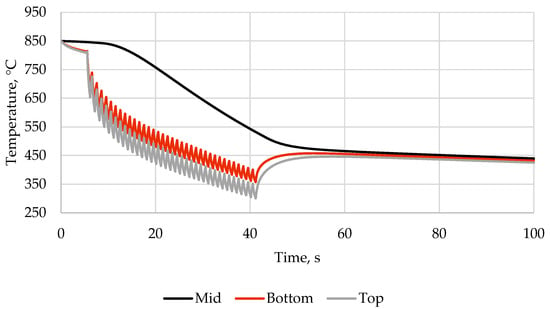

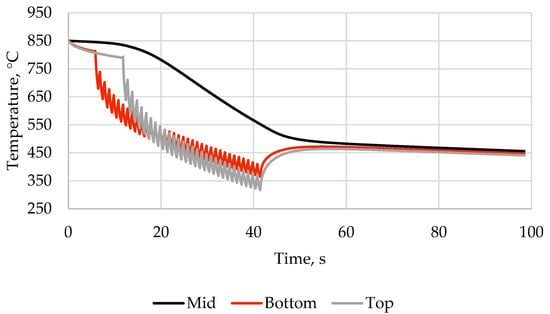

After cooling according to the standard strategy, the plate exhibits unsatisfactory flatness (Figure 10), which is caused by the difference in the thermal expansion coefficients of the materials in the clad plate. The maximum plate bending value exceeds 134 mm, making it impossible to transport the plate on the roller table. The equivalent von Mises stresses within the plate are shown in Figure 11. The graph of temperature versus cooling time is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 10.

Final shape of the plate after cooling according to standard schedule.

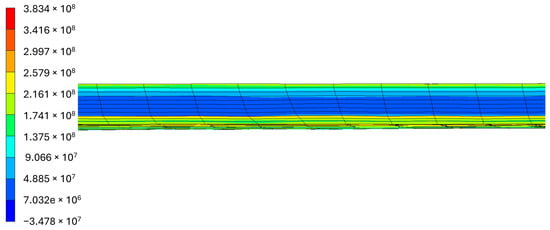

Figure 11.

Von Mises stress (MPa) distribution in plates middle section along length direction.

Figure 12.

The graph of temperature versus cooling time for standard schedule.

The maximum stresses in the central cross-section of the plate exceed 210 MPa, with stresses in the cladding layer being 90 MPa higher than those on the top surface.

Cooling using the second strategy, with alternating header activation, did not lead to significant improvement in flatness. The maximum bending value was 107 mm.

Cooling using the third strategy, with delayed activation of the lower headers (on the cladding layer side), yielded a positive result. A series of experiments was conducted to select a schedule that would provide the necessary cooling rate and flatness. Upon reaching an acceptable bending value, further increasing the activation time difference between the lower and upper headers is not advisable, as asymmetrical conditions for structure formation are inherently not a positive factor. The best result was shown by the strategy with the first six lower headers deactivated. All simulated cases are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of simulated cases.

The resulting plate shape is presented in Figure 13, the stresses in the central cross-section are shown in Figure 14, and the temperature–time graphs are in Figure 15. The stress distribution pattern in the plate is similar to those described above; however, the difference between the upper and lower surfaces of the plate has decreased to 40 MPa. The maximum plate bending value is 22 mm, which allows for transportation on the roller table.

Figure 13.

Final shape of the plate after cooling according to schedule with 6 headers delayed activation.

Figure 14.

Von Mises stress (MPa) distribution in plates middle section along length direction for schedule with 6 headers delayed activation.

Figure 15.

The graph of temperature versus cooling time for schedule with 6 headers delayed activation.

Based on the developed cooling schedule, a trial batch of clad plates was produced, with investigation of the properties of the base layer and the bonding zone. Structural analysis was performed on metallographic specimens prepared in the transverse direction relative to the workpiece.

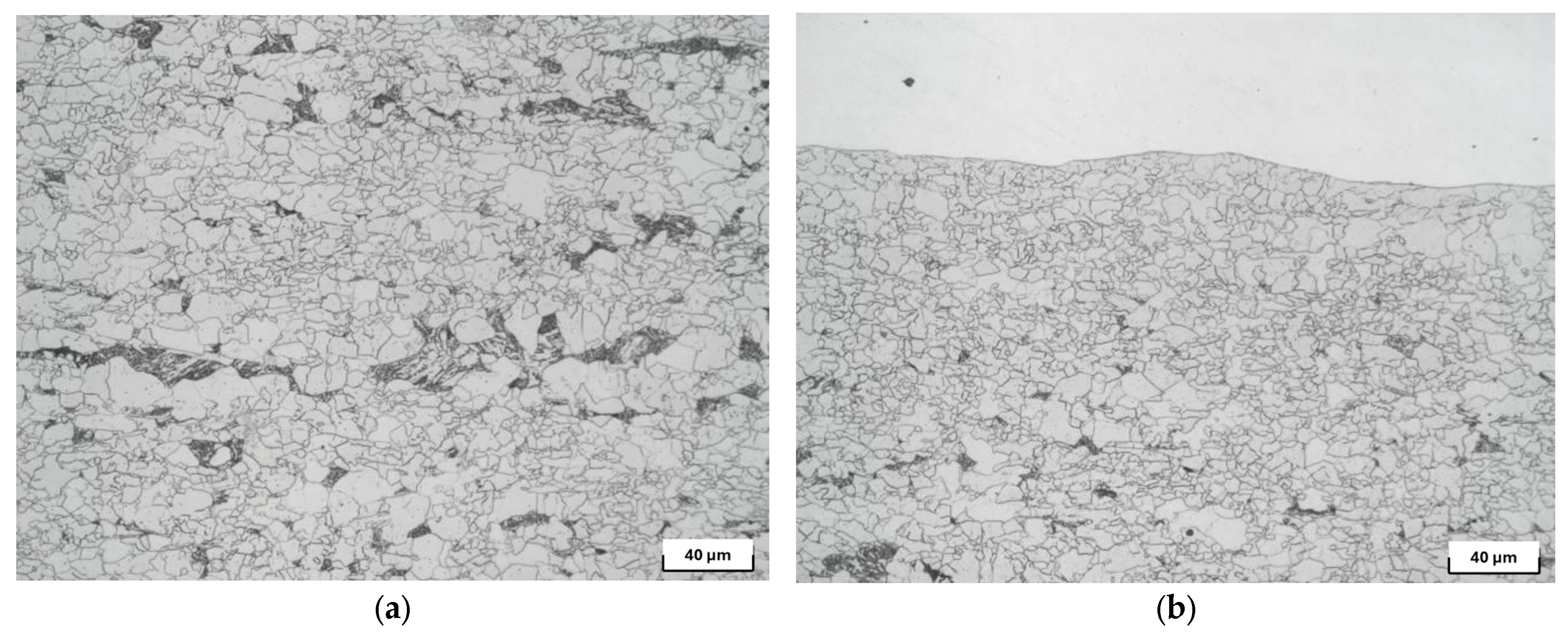

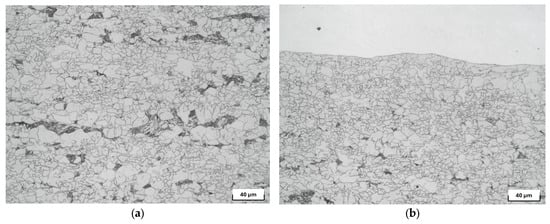

3.3. Mechanical Properties Achieved Using Developed Cooling Schedule

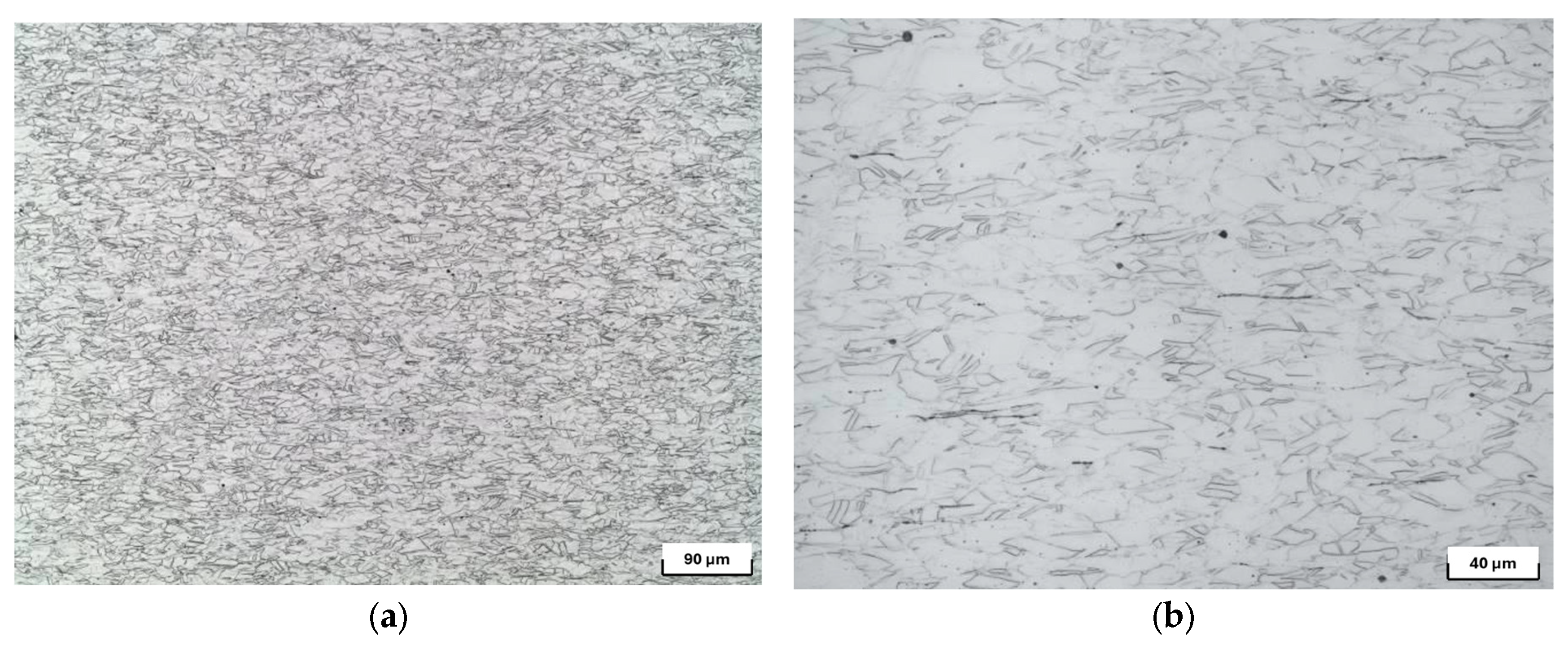

The base X70 steel exhibits a microstructure of polygonal ferrite (70%, ASTM 10-13, ~8–14 µm), bainite (20%), and pearlite (10%) (Figure 16a). This combination together with fine grain provides the requisite high strength and toughness. Adjacent to the interface with the overlaid layer, a shallow decarburization zone ≤ 40 µm wide is observed, consisting of carbon-depleted ferrite (Figure 16b). While locally altering properties, this zone does not compromise the bulk material performance.

Figure 16.

(a) Microstructure at ¼ thickness, (b) microstructure near the transition zone.

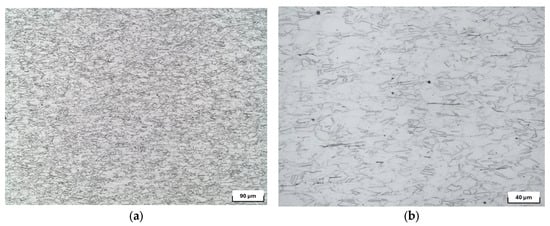

The cladding layer, made of austenitic stainless steel 316L, consists of deformed austenite grains and a small amount of residual high-temperature ferrite (δ-ferrite) (Figure 17a,b). Twins are clearly visible within the austenite grains.

Figure 17.

Microstructure of the clad layer (316L). (a) 20× magnification, (b) 50× magnification.

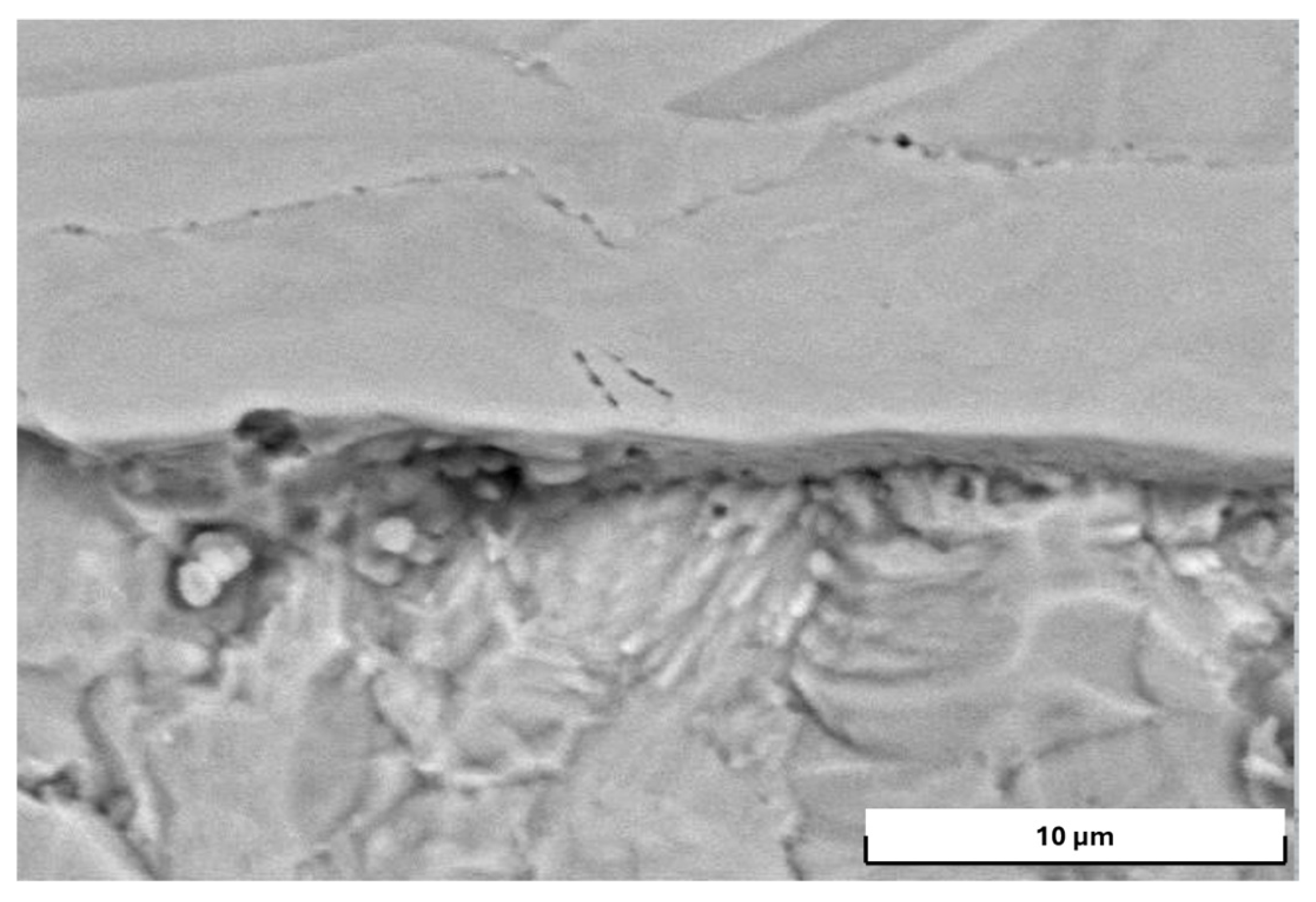

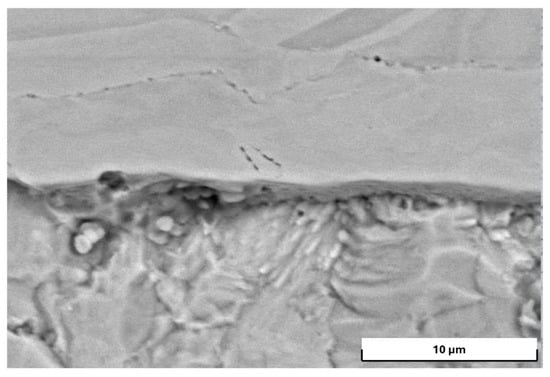

The fusion boundary between the two layers on both sides of the contact surfaces is almost imperceptible and appears as a dark band with a width of 5 to 10 µm (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Fusion boundary between the base and cladding layers (specimen from plates’ head).

The properties of the base layer are presented in Table 3 and meet the requirements for steels of X70 class.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of base layer.

The shear strength assessed during shear tests according to ASTM A264 [20], remained at a high level (350–420 MPa), which significantly exceeds normative requirements. Full section bend tests with tension on both the inner and outer surfaces were completed without ruptures or tears.

Tests for resistance to intergranular corrosion according to ASTM A262 (Practice E) [21] were successfully passed by the cladding metal.

Thus, the developed cooling technology ensures not only the required flatness but also the required properties demanded for clad rolled products.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that a combined finite element and machine learning approach can successfully address the significant technological challenge of achieving both target mechanical properties and high geometric flatness in asymmetrically clad hot-rolled plates. The core of the problem lies in the inherent conflict between the need for rapid cooling to form the required bainitic-ferritic microstructure in the high-strength base steel (X70) and the thermoelastic stresses induced by the differential thermal contraction between the dissimilar X70 base and AISI 316L cladding layers.

The standard, symmetric cooling schedule resulted in severe bending (>130 mm), confirming the dominant influence of the cladding layer. The cladding’s lower thermal conductivity and higher coefficient of thermal expansion compared to the base steel create a non-uniform through-thickness temperature field during cooling. The cladding side cools and contracts more slowly, placing the hotter, more rapidly contracting base layer under tension. This generates a significant thermoelastic bending moment that deforms the plate. This mechanism aligns with the foundational work on residual stresses in rolled products [6,7], but is critically exacerbated by the bimetallic nature of the clad plate, a factor insufficiently addressed in the previous literature for non-clad products [9,10,11,12,13].

The proposed optimized strategy—delaying the activation of the first six lower headers (on the cladding side)—functions by creating a compensating thermal gradient. By initially cooling only the top surface (base layer side), an inverse bending moment is created. This moment counteracts the natural bending tendency induced by the material properties difference. The study demonstrates that six-header delay reduces plate bending to a manageable 22 mm. Crucially, this was achieved without compromising the average cooling rate (6.5 °C/s), which remained within the range necessary for the austenite-to-bainite transformation in X70 steel, as established in prior research [1,2].

The successful validation of the model against both laboratory-scale and industrial-scale trials confirms the robustness of the integrated methodology. The use of a CatBoost ML model to predict heat transfer coefficient (HTC) was instrumental in moving beyond constant or simplified HTC assumptions, a common limitation in purely physics-based FEM simulations. This data-informed approach significantly enhanced the predictive accuracy of the thermal and stress fields, as evidenced by the close match with experimental bending values.

The mechanical tests of the trial batch are demonstrated. The formation of a fine-grained ferrite-bainite microstructure with the required mechanical properties (σt = 608 MPa, σf = 560 MPa, KCV-60 = 334 J/cm2) confirms that the asymmetric cooling strategy did not adversely affect the phase transformation kinetics in the base layer. The minimal decarburization zone (~30–40 µm) and the strong metallurgical bond (shear strength 400 MPa) at the interface indicate that the thermal cycle was also compatible with maintaining the integrity of the clad joint. The preservation of the cladding’s corrosion resistance further underscores the process’s suitability.

However, several implications and limitations warrant consideration. First, the optimal delay strategy is specific to this material combination (X70/316L), thickness ratio (25 mm/3 mm), and the specific geometry of the cooling unit. For different clad systems (e.g., different steel grades or cladding thicknesses), the magnitude and timing of the required compensating moment would need recalculation. With some approximation and acceptable loss of accuracy, obtained results could be used for material combinations like S355 + AISI 321, S500 + AISI 316L/317L/904L, as their mechanical properties ratio and thermal properties are similar.

A cladding thickness of 3 mm is widely used across various applications, so the main variable thickness would be base layer thickness. Considering that transportation on the roller table remains possible with a deflection of about 40–50 mm, it can be assumed that the developed cooling strategy could be applied to rolled plates with thicknesses in the range of 20–35 mm. With further increase in plate thickness, the limiting factor may become the cooling rate, while for thinner plates, the magnitude of compensating stresses might be insufficient.

Second, while the model accounts for thermoelastic stress, it does not explicitly incorporate transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and the associated volumetric changes during phase transformations, which can contribute to the final stress state [8]. Integrating a coupled thermomechanical–metallurgical model could further refine predictions, though at a substantial computational cost.

The proposed strategy is readily implementable on existing accelerated cooling units with zone control, requiring only a modification of the control logic for header activation sequences. It offers a systematic, model-driven alternative to costly and time-consuming trial-and-error methods.

Future research should focus on expanding the operational window of the model. This includes developing a broader database for the ML-HTC predictor to cover a wider range of plate dimensions, steel grades, and cooling unit designs. Furthermore, investigating dynamic schedule control, where header activation is adjusted in real-time based on incoming plate temperature profiles, could lead to even more robust flatness control.

In conclusion, this work validates that a strategically induced, controlled thermal asymmetry is an effective tool for counteracting the bending of clad plates after cooling. It establishes a framework for the design and optimization of cooling processes for asymmetric clad plate production, successfully balancing the often-contradictory demands of mechanical properties and geometry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.Z. and A.V.M.; methodology, A.G.Z. and A.V.M.; software, A.G.Z. and N.R.B.; validation, A.G.Z., A.V.M. and N.R.B.; formal analysis, A.G.Z. and A.P.S.; investigation, A.G.Z. and A.V.M.; data curation, N.R.B. and M.O.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.Z. and A.V.M.; writing—review and editing, A.G.Z., A.V.M. and A.P.S.; visualization, A.G.Z. and N.R.B.; supervision, A.G.Z. and A.V.M.; project administration, A.G.Z. and A.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Efron, L.I. Metallovedenie v “Bol’shoi” Metallurgii. Trubnye Stali (Metallurgy in “Big” Industry. Pipe Steels); Metallurgizdat: Moscow, Russia, 2012; p. 696. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pogozhelsky, V.I.; Litvinenko, D.A.; Matrosov, Y.I.; Ivanitsky, A.V. Kontroliruemaya Prokatka (Controlled Rolling); Metallurgiya: Moscow, Russia, 1979; p. 184. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lettner, J.; Klöwer, J.; Behrens, R. Clad Plates and Pipes in Oil and Gas Production: Applications—Fabrication—Welding. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2002, Denver, CO, USA, 7–12 April 2002; AMPP: Houston, TX, USA; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, A.; Noor, M.Z.Z.; Karrech, A. CRA clad pipes: Do their benefits justify sole selection? J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2025, 5, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qin, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, S.; Geng, P. Microstructures and mechanical properties of stainless steel clad plate joint with diverse filler metals. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2522–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, J.S.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, S.; Kang, Y.T. Heat transfer performance assessment for precise accelerated control cooling of the hot heavy clad plate. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 45, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, A.; Zhao, Z.; Xue, R. Effect of Residual Stress on the Continuous Cooling Transformation of High-Strength Low-Alloy Hot-Rolled Strip. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.G.; Han, H.N.; Lee, J.K. A Finite Element Model for the Prediction of Thermal and Metallurgical Behavior of Strip on Run-out-table in Hot Rolling. ISIJ Int. 2002, 42, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, K.; Dong, J. Modeling and Monitoring for Laminar Cooling Process of Hot Steel Strip Rolling with Time–Space Nature. Processes 2022, 10, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Hu, X.; Cui, J.; Xing, Z. Kinetic Model for the Phase Transformation of High-Strength Steel Under Arbitrary Cooling Conditions. Met. Mater. Int. 2019, 25, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Kumar, A. Coupled Temperature-Microstructure Model for Predicting Temperature Distribution and Phase Transformation in Steel for Arbitrary Cooling Curves. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2021, 13, 041008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Fei, A. Multi-Objective Optimization of Low-Alloy Hot-Rolled Strip Cooling Process Based on Gray Correlation Analysis. Metals 2024, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinyagin, A.G.; Muntin, A.V.; Ilinsky, V.I.; Nikitin, G.S. Mathematical modeling of the process of accelerated cooling of a sheet on a 5000 mill. Probl. Chernoy Metall. I Materialoved. (Probl. Ferr. Metall. Mater. Sci.) 2013, 1, 9–15. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Sun, J.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Ma, L. Effect of hot rolling and cooling process on microstructure and properties of 2205/Q235 clad plate. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2018, 25, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinyagin, A.G.; Muntin, A.V.; Stepanov, A.P.; Borisenko, N.R. Study of the features of clad sheet deformation during hot rolling. Chernye Met. (Ferr. Met.) 2023, 12, 49–55. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Iron and Steel Research Association. Physical Constants of Some Commercial Steels at Elevated Temperatures (Based on Measurements Made at the National Physical Laboratory, Teddington); Butterworths Scientific Publications: London, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, F.; Malenock, P.; Smith, G.V. The Influence of Temperature on the Elastic Constants of Some Commercial Steels. JOM 1952, 4, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, P. Properties of Steel at Elevated Temperatures. In Advanced Analysis and Design for Fire Safety of Steel Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinyagin, A.G. Use of machine learning methods for determination of the boundary conditions coefficients in a FEM task for the case of accelerated cooling of hot-rolled sheet metal. CIS Iron Steel Rev. 2023, 25, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM A264; Standard Specification for Stainless Chromium-Nickel Steel-Clad Plate, Sheet, and Strip. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM A262; Standard Practices for Detecting Susceptibility to Intergranular Attack in Austenitic Stainless Steels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.