Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Analyzed 82 studies. Suggested that truck–drone systems can reduce costs by 10% to 50% and time by 15% to 40% through GIS optimization of routing and launch-site placement.

- Identified seven interconnected research domains that collectively define the technological and policy landscape. Smart Agriculture Integration (28 studies), GIS Analytics (21 studies), and Truck–Drone Coordination (15 studies) were most developed. Sustainability assessment (5 studies) and strategic network design (8 studies) remained underexplored.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Addressing regional challenges such as cold-weather performance, low delivery density, connectivity gaps, and regulatory constraints is essential to realize practical deployment in rural states like North Dakota, USA.

- GIS-guided truck–drone systems can serve as a scalable model for sustainable, data-driven logistics that strengthen agricultural productivity and rural resilience in cold-climate regions.

Abstract

Efficient last-mile delivery remains a critical challenge for rural agricultural logistics, globally, particularly in cold-climate regions with dispersed agricultural operations. Truck–drone hybrids can reduce delivery times but face payload limits, cold-weather battery loss, and beyond-visual-line-of-sight regulations. This review evaluates the potential of GIS-enabled truck–drone hybrid systems to overcome infrastructural, environmental, and operational barriers in such settings. This study uses the state of North Dakota (USA) as a representative case because of its cold climate, low density, and weak connectivity. These conditions require different routing and system assumptions than typical regions. The study conducts a systematic review of 81 high-quality publications. It identifies seven interconnected research domains: GIS analytics, truck–drone coordination, smart agriculture integration, rural implementation, sustainability assessment, strategic design, and data security. The findings stipulate that GIS enhances hybrid logistics through route optimization, launch site planning, and real-time monitoring. Additionally, this study emphasizes the rural, low-density context and identifies specific gaps related to cold-weather performance, restrictions to line-of-sight operations, and economic feasibility in ultra-low-density delivery networks. The study concludes with a roadmap for research and policy development to enable practical deployment in cold-climate agricultural regions.

1. Introduction

Last-mile delivery is the most expensive and complex stage of agricultural logistics. The challenge is especially severe in vast rural areas. In particular, northern U.S. states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming experience these challenges. Farms in these states are widely dispersed. For example, in North Dakota (ND), farmland covers 38.5 million acres, with an average farm size of more than 1500 acres and about 26,800 farms in total. South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming have average farm sizes of 1495, 2412 and 2743 acres, respectively. In these regions, long distances separate production sites from supply centers. Hence, reliance on trucks alone increases costs, extends delivery times, and raises emissions, particularly during critical planting and harvest windows [1].

The key problem is the inefficiency of serving remote, dispersed farms with truck-only logistics. Farm remoteness and fragmented delivery routes create operational challenges that single-mode transport cannot address. Hybrid truck–drone systems offer a promising alternative. Trucks provide long-haul capacity, while drones handle fast, short-range deliveries directly to farms. This division of roles reduces delivery times and expands service reach [2]. Drones provide flexible payload capacity from a few pounds to several thousand pounds, depending on their size [3]. Yet their deployment remains constrained by regulations and operational limitations in inclement weather [4]. Restrictions on beyond-visual-line-of-sight (BVLOS) operations by government agencies, combined with ND’s harsh winter conditions, require new strategies to ensure operational reliability.

Geographic information systems (GIS) are central to these strategies. GIS enables route optimization, strategic network design, and real-time monitoring by integrating maps of farm locations, road networks, and field boundaries. GIS identifies suitable launch and landing sites, designs recharge infrastructure, and fuses environmental data into dynamic delivery planning [5]. In agriculture, GIS demonstrates its versatility through the support of soil and crop suitability mapping, irrigation planning, and precision farming [6].

The convergence of drones and GIS extends this potential. Smart farming platforms, based on Internet-of-Things (IoT) technologies, now integrate sensors, cloud analytics, and autonomous machinery to monitor conditions and automate inputs [7]. When combined with drones and GIS, these systems support truck–drone logistics by informing coordination, scheduling, and delivery prioritization decisions based on real-time farm demand. Such integration improves hybrid truck–drone efficiency by reducing idle time, failed dispatches, and suboptimal truck–drone synchronization [8]. In addition, AI-based large language models (LLMs) have also shown significant potential for optimizing UAV operations in low-altitude economic applications. For instance, Zhou et al. (2025) proposed an LLM-enhanced Q-learning framework that accelerates multi-drone scheduling by up to 1.35 times through adaptive path planning and resource allocation, demonstrating how large language models can guide coordination and scheduling decisions in multi-UAV systems under dynamic operational constraints [9]. Complementing this algorithmic advance, recent work on large-model deployment for the low-altitude economy emphasizes AI-driven system architectures that integrate edge intelligence, aerial platforms, and communication networks to support scalable coordination, real-time decision-making, and resilient scheduling across distributed drone operations [10]. Together, these approaches indicate a methodological shift toward AI-assisted coordination and scheduling architectures that are directly applicable to truck–drone hybrid logistics, where real-time dispatch, resource allocation, and system-level orchestration are critical.

Previous reviews examined GIS applications and drone logistics separately, without the integration in hybrid truck–drone systems for regions experiencing extreme winter cold, sparse population, and agriculture-dependent economies. Through tier-based classification, this paper identified research maturity gaps. The study revealed that 84% of the studies were at conceptual or simulation stages while only 16% achieved field validation. Prior reviews did not provide this quantitative assessment. This study established explicit connections between technological requirements (cold-weather batteries, heavy-payload designs), regulatory priorities (agricultural BVLOS pathways), infrastructure needs (low-connectivity frameworks), and security safeguards. Previous reviews identified challenges but did not provide integrated implementation strategies for cold-climate agricultural contexts.

The goal of this study is to examine how GIS-enabled truck–drone hybrid systems can enhance agricultural last-mile delivery in regions characterized by dispersed farms and extreme environmental conditions. The study uses ND as a representative region because of its extreme winter temperatures, low population density, large farms, and limited connectivity. Truck–drone models must be adapted through cold-aware energy models, low-density routing formulations, wind-adjusted flight planning, and coordination architectures that tolerate intermittent connectivity. Drone batteries lose energy faster in the cold, requiring temperature-dependent energy consumption models and conservative scheduling constraints within truck–drone coordination algorithms. This reduces flight time and require conservative endurance limits. Sparse delivery points demand single trips and long repositioning. Weak networks require offline or intermittent communication. Seasonal road closures and heavy agricultural payloads also affect routing and energy assumptions. The review evaluates the role of GIS in supporting routing, scheduling, monitoring, and spatial network design. It integrates insights from seven interrelated domains: GIS analytics, smart agriculture integration, truck–drone coordination, rural implementation, sustainability assessment, strategic network design, and data security. It further identifies key technological, operational, and regulatory challenges, assesses economic and environmental outcomes, and explores how these systems can strengthen rural resilience and long-term agricultural sustainability. This includes support from robust cybersecurity and policy frameworks [11].

To address these objectives, the study integrates insights from multidisciplinary research at the intersection of geospatial analytics, intelligent transportation systems, and precision agriculture. It emphasizes how emerging technologies collectively shape the development of resilient hybrid logistics networks. These technologies include IoT connectivity, AI-driven routing algorithms, edge computing, and data security frameworks. The analysis draws on both global literature and regional considerations to identify opportunities and barriers relevant to cold-climate rural contexts such as ND. Accordingly, the study is guided by three central questions:

- How can GIS specifically enhance coordination, routing, and strategic network design in truck–drone hybrid systems for rural agriculture?

- What technological, regulatory, and environmental constraints impact the deployment of such systems in cold-climate and low-density regions like ND?

- What specific sustainable benefits have been demonstrated for truck–drone hybrid systems in cold-climate agricultural settings?

The remainder of the study presents the methodology for the review (Section 2), synthesizes findings in the results (Section 3), extrapolates implications in the discussion (Section 4), concludes the study (Section 5) with policy and practice recommendations, and finally outlines research priorities (Section 6).

2. Methodology

This study employed a systematic and multidisciplinary literature review, combined with a thematic analysis, to synthesize knowledge at the intersection of geoinformatics, intelligent transportation systems, precision agriculture, and rural logistics. The primary objective was to assess how geospatial technologies enable coordination, scheduling, and routing in hybrid truck–drone delivery systems operating in rural agricultural contexts.

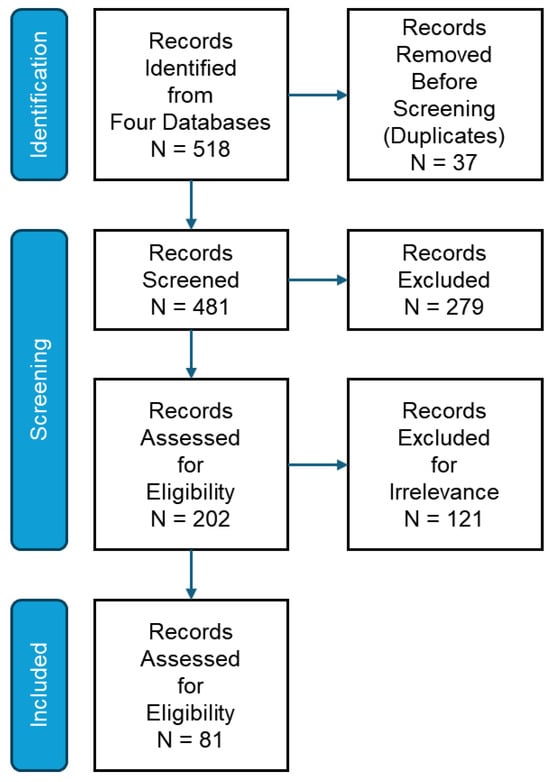

The structured bibliographic search strategy illustrated in Figure 1 guided the review process. It follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, widely recognized by scholars for its transparency, rigor, and replicability [12]. The search queried four major academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. The query command utilized a Boolean search with the following logic:

where the wild-card character “*” represents any alternative ending. To capture recent developments, the review focused on peer-reviewed English language publications from the last decade.(“truck–drone*” OR “UAV” OR “GIS” OR “geographic information systems” OR “IoT”) AND (“last mile” OR “logistics” OR “delivery”) AND “agricult*” AND “rural”

Figure 1.

Article filtering following the PRISMA guidelines.

The initial search retrieved 519 records: 372 from Web-of-Science, 99 from Scopus, and 48 from ScienceDirect and SpringerLink combined. The search excluded studies (exclusion criteria) that were not written in English and documents that was not peer-reviewed. The duplicate removal process then reduced those to 482 unique studies. A two-stage screening process followed. The first stage applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts. The process retained studies (inclusion criteria) if they addressed two core themes from among the following: (1) GIS applications in agriculture, (2) hybrid truck–drone logistics, (3) spatial data analysis for route optimization, or (4) integration of digital agriculture technologies in rural delivery systems. This step produced a refined set of 203 articles.

The second stage applied a quality appraisal protocol (QAP) to evaluate methodological rigor and relevance. The QAP employed eight assessment criteria, as summarized in Table 1. These criteria were GIS integration, hybrid truck–drone technology, last-mile delivery to support agriculture, spatial optimization, use of empirical or quantitative methods, rural contexts, sustainability metrics, and integration of IoT or digital agriculture tools. Two reviewers independently screened all records and resolved disagreements through consensus. The reviewers retained studies that scored at least 5 out of 8 across the criteria. This step retained 81 high-quality publications for full-text reviews.

Table 1.

Quality appraisal protocol to guide article selection.

The reviewers score each document as 1 for meeting the criteria and 0 otherwise. The threshold of 5 out of 8 ensured methodological rigor while retaining studies relevant to multiple core domains. For example, study by Dai et al. (2024) [1] scored 6/8 because it addressed hybrid technology (1), last-mile agriculture (1), spatial optimization (1), empirical methods (1), rural context (1), and GIS integration (1), but not sustainability metrics (0) or IoT integration (0). That is, the study directly addressed truck–drone coordination in rural agricultural delivery. Studies below 5 lacked depth across domains.

The reviewers adopted a thematic coding framework, combining inductive and deductive approaches, to classify the studies into the five thematic domains, as summarized in Table 2. These were (1) GIS applications and spatial analytics, (2) truck–drone system coordination, (3) smart agriculture technology integration, (4) rural infrastructure and implementation, and (5) sustainability and economic impact assessment. This framework enabled structured synthesis and facilitated cross-comparison of strategies, models, and outcomes across different regions and technological ecosystems.

Table 2.

Thematic classification of the studies.

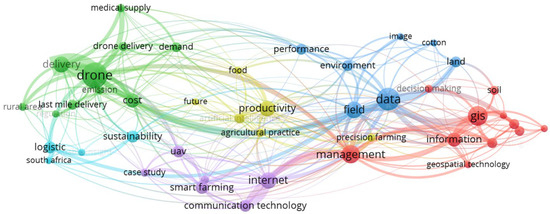

To complement the review, this study conducted a term co-occurrence analysis using the tool VOSviewer version 1.6.20 [13]. The tool extracted key terms from titles and abstracts of the selected publications and mapped their relationships based on frequency and co-occurrence strength. The resulting network visualization organized terms into color-coded clusters. The size of each node in the network reflects term frequency, and the thickness of lines connecting nodes indicates the strength of association. This network visualization highlights dominant themes and shows how they interconnect across disciplinary boundaries. By identifying thematic clusters and cross-linkages, the co-occurrence analysis provided insights into the intellectual structure of research on GIS-enabled truck–drone hybrid systems and highlighted the areas where technological, environmental, and operational considerations converge in agricultural logistics.

3. Results

The approach of combining systematic search protocols, multi-criteria evaluation, and thematic categorization, including a term co-occurrence network and clustering, ensured a rigorous review process with multidisciplinary contexts. The outcome was a comprehensive foundation that distilled both strategic insights and technical considerations relevant to researchers, policymakers, and agricultural practitioners seeking to advance GIS-enabled truck–drone logistics. The review identified truck–drone coordination and scheduling as the central operational domain, supported by six enabling domains summarized in Table 3. They were GIS analytics, smart agriculture integration, truck–drone coordination, rural implementation, sustainability assessment, strategic network design, and data security. These domains collectively define the research landscape of hybrid truck–drone delivery systems. Across these domains, the findings reveal how geospatial technologies enhance route optimization, system coordination, and strategic network design while exposing persistent challenges related to cold-weather performance, regulatory constraints, and data security. The following subsections synthesize these insights to establish the technical and contextual foundation for the subsequent discussion.

Table 3.

Literature categorization by domain identified.

Figure 2 complements the topic categorization by showing a term co-occurrence network that highlights the main research themes linking GIS, drones, and agricultural logistics. The network shows 44 terms that had at least five co-occurrences across the corpus, forming six clusters. The green cluster centers on the term “drone” with occurrences in 54 articles and 26 links to central terms such as delivery, last-mile delivery, emission, cost, demand, and medical supply. These connections reflect operational and environmental aspects of drone-based logistics. The red cluster centers on the term “GIS” with occurrences in 33 articles and 24 links to terms including “geospatial technology,” “information,” “management,” “soil,” and “decision making.” This cluster highlights the role of spatial analysis and data-driven planning. The dark blue cluster focuses on the term “data” with occurrences in 44 articles and links to 38 terms such as “field,” “environment,” “land,” and “performance.” These indicate strong connections between geospatial datasets, environmental monitoring, and precision farming. The purple cluster centers on the term “internet” with occurrences in 24 articles and 25 links to terms including “smart farming,” “communication technology,” and “UAV.”

Figure 2.

Term co-occurrence and thematic clustering.

These relationships highlight the integration of IoT and connectivity tools with drone applications. The yellow cluster centers on the term “productivity” with occurrences in 22 articles and 32 links to terms such as “agricultural practice,” “future,” “food,” “artificial intelligence,” and “precision farming.” These relationships reflect how current and emerging technologies are influencing farm productivity and resource use. The light blue cluster focuses on the term “sustainability” with a strong connection to the term “logistic” as well as cross-links to terms in other clusters such as “field,” “data,” “internet,” and “management.” These cross-connections highlight the leading role of sustainability as a concept bridging operational logistics, technological integration, and data-driven strategic network design. Together, the clusters reveal that research converges on combining drones, GIS, and smart technologies to improve sustainability, efficiency, and strategic network design in agricultural logistics. The subsections that follow provide further insights into the main topics of the categorized literature.

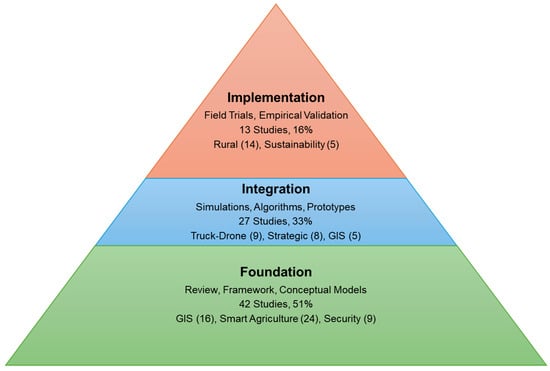

Beyond domain classification as shown in Table 3, the research team reviewed the literature by contribution maturity to track research progress. The team placed studies into three tiers based on the methods used. Foundation-tier studies highlighted concepts and baseline frameworks. Integration-tier studies combined technologies through simulations, algorithms, or prototypes. Implementation-tier studies validated systems through field tests, pilot programs, or data collection. The review revealed that 84% of the studies were still at the concept or simulation stage. Only 16% had been validated in real operations, as shown in Figure 3. Implementation-tier work was mostly focused on rural healthcare logistics [77], sustainability lifecycle assessments [71,72,73,74], and smart agriculture pilots. No implementation-tier study combined GIS-based agricultural coordination, cold-climate operation below 20 °C, and ultra-low-density delivery conditions. This triple-constraint gap defines the main research opportunity in agriculture logistics for regions with similar demographics to ND.

Figure 3.

Research progression pyramid.

3.1. GIS Application and Spatial Analystics

Relevant GIS capabilities for hybrid logistics include route optimization, launch-site suitability, and dynamic spatial modeling to support agricultural delivery. GIS has evolved from basic land mapping to advanced spatial modeling [5,6,24,27], including digital-twin systems and smart transportation networks [5,6,24,27]. The reviewed literature covering agriculture highlights that GIS supports crop mapping, soil suitability analysis, irrigation design, and water quality monitoring [14,16,17,21,23,32]. Studies have also validated its effectiveness in emergency logistics and transportation safety analytics [16,22].

Three core capabilities make GIS particularly valuable for hybrid delivery systems. First, site suitability analysis identifies optimal locations for infrastructure, such as vertiports located at existing airports and hospital heliports [15]. Second, network optimization enhances route efficiency and facility placement across dispersed networks [5,23,32]. Third, dynamic spatial modeling enables real-time operational adjustments through digital-twin systems that incorporate cold-dependent battery limits, wind fields, seasonal road closures, and moving-truck launch constraints [5,6,24,27].

Despite these advancements, a critical research gap persists. That is, GIS applications for truck–drone coordination in rural agricultural settings remain underexplored, particularly under challenging operational constraints. In cold-climate regions, hybrid delivery systems face unique challenges such as extreme temperatures, seasonal road closures, limited connectivity, and dynamic infrastructure availability. While GIS could significantly reduce productivity losses, improve delivery efficiency, and enable rapid route adjustments during disruptions, few studies examine how these systems perform under such conditions year-round. This gap limits current understanding of operational reliability and real-time spatial decision-making capabilities in agricultural regions where these constraints are most acute.

3.2. Smart Agriculture Technology Integration

Studies report rapid convergence of IoT sensors, edge computing, and machine learning as inputs to truck–drone coordination, scheduling, and dispatch decisions rather than as standalone farm management systems. The convergence of such technologies enables real-time monitoring, automated irrigation, yield estimation, and spatial variability analysis. The studies emphasize how the systems reduce input waste and improve timing of farm operations. Another key insight is that these technologies primarily increase readiness for autonomous truck–drone workflows through improved coordination, timing, and routing analytics.

Analysis of 28 studies pertaining to smart agriculture integration confirmed rapid growth of data-driven farming systems. Technology maturity varied significantly across applications. IoT and machine learning improved irrigation, fertilization, and crop monitoring [35,36,38,39,40,44,51]. For instance, AI-based precision agriculture techniques reduced chemical use by approximately 20% in controlled studies in India, primarily through targeted application of fertilizers and pesticides based on real-time crop monitoring and soil analysis [50]. However, these results were obtained under specific experimental conditions and may vary with farm size, crop type, and technology adoption levels.

Studies examined IoT, AI, and ML integration across farming systems [53]. Three distinct technology maturity levels emerged from the reviewed literature. The first is recording technologies for crop and soil scouting. These are commercially deployed with higher adoption readiness. The second is actuation systems for precision applications. These are transitioning from research to commercial products. The third is robotics and fully autonomous workflows. However, these remain primarily in research and experimental stages due to regulatory and safety barriers [37,40,44].

Critical research gaps constrain deployment in cold-weather regions. However, all implementations assumed reliable broadband connectivity. Only three studies addressed low-connectivity scenarios. This highlights the need for edge-based truck–drone coordination architectures that support delayed synchronization rather than continuous cloud connectivity. These studies focused on delayed data uploads rather than real-time decisions under intermittent network access [54,62]. None of the studies quantified cold-weather sensor reliability or provided winterization protocols. Several UAV technical studies mentioned weather dependency. This included battery life limitations, payload constraints, reduced flight range, and weather sensitivity. However, the studies did not provide details such as temperature thresholds, cancellation rates, or performance curves for extreme conditions. No study examined how seasonal connectivity breaks affect machine learning accuracy or winter dormancy data storage policies.

Five major adoption barriers remain. First, sensor data formats are incompatible, and the absence of standardized protocols forces custom integration. Second, farmers lack training to interpret system outputs and resolve technical issues, while extension services lag behind technological development. Third, high initial costs and uncertain economic feasibility exclude many smallholder farmers despite the long-term benefits. Fourth, unclear data-ownership rules and weak privacy protections discourage the data sharing needed for regional optimization. Fifth, policies governing autonomous systems, data rights, and airspace remain fragmented. These barriers are especially severe in cold-climate agricultural regions, where limited connectivity and extreme temperatures create fundamental operational challenges.

3.3. Truck–Drone Hybrid System Coordination

Hybrid truck–drone systems reduce delivery times by assigning long hauls to trucks and final legs to drones. This approach expands service reach in low-density and hard-to-access rural areas [1,57,58]. The literature review identified four major delivery tracks. These were synchronized delivery where truck and drone coordinate closely, parallel delivery with independent operations, truck-assisted delivery where trucks support drone operations, and drone-assisted delivery which emerged recently [61]. Nearly all studies focused on underlying decision and optimization problems with goals to reduce delivery times or costs compared to truck-only or drone-only systems [61]. One study investigated wind impact on drone-based delivery [60]. It proposed a minimum-energy drone-trajectory problem that optimized round-trip trajectories from trucks by adapting drone paths to exploit tailwinds between truck routes and delivery points. The study evaluated this wind-aware trajectory using synthetic and real data with flight simulations in BlueSky simulator.

Routes, drone flights, and battery limits are coordinated using optimization algorithms that must be extended to include temperature-dependent endurance, sparse-delivery repositioning costs, and wind-aware flight feasibility constraints. For instance, one study applied Mixed-Integer Linear Programming based on authentic Amazon logistics data. The study demonstrated observable decreases in delivery time and cost [64]. Sensitivity analysis revealed how adjustments to important factors such as volume of consumers, number of trucks, and drone usage affect delivery system effectiveness.

One study categorized policy challenges for coordinated drone–truck delivery into six areas: airspace safety and security, zone planning and integration, liability and risk assessment, interoperability and standards, societal challenges and equity, and environment and sustainability [61]. Studies relating to policy challenges emphasized the need for policymakers, operators, and researchers to work in orchestrated manner to achieve sustainable combined drone–truck delivery. In agriculture, drones assist with monitoring, spraying, and crop management by providing real-time high-resolution data collection to enable informed decisions on irrigation, fertilization, and pest management [62,66,68]. Drones offer precision spraying and application of agricultural inputs to minimize chemical wastage and optimize resource utilization. Drones also provide access to areas difficult to reach [66]. This capability reduces manual labor and increases operational efficiency. Therefore, the literature suggests that drones can enhance efficiency across rural landscapes.

However, operational reliability under adverse conditions represents a critical constraint. Wind conditions directly affect flight stability and energy consumption [68]. Aerodynamic planning reduces energy expenditure when wind patterns are incorporated [60]. Temperature extremes influence battery discharge and internal resistance [68]. Path planning algorithms must account for environmental factors [78]. Structural resilience testing under combined cold, wind, and precipitation remains absent from agricultural studies. This gap limits assessment of year-round reliability in cold-climate regions. Although several studies propose aerodynamic optimization [60], multimodal coordination [65], and heavy-lift drone designs [66], these advancements are discussed here primarily to contextualize their relevance to rural agricultural delivery rather than as engineering solutions.

3.4. Rural Infrastructure and Implementation

Studies emphasize benefits in rural geographies with long distances, variable roads, and harsh climates [1,57,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. Direct aerial paths mitigate poor road access and seasonal closures. GIS-guided site selection improves launch, landing, and recharge placement. These studies suggest that multimodal coordination improves reliability under environmental uncertainty. Case studies in rural healthcare logistics and humanitarian operations demonstrated relevance to sparse networks.

3.5. Sustainability and Ecnomic Impact Assessment

Five studies showed that hybrid truck–drone systems reduce emissions, energy use, and delivery costs [60,71,72,74,75]. Life cycle assessments confirmed about 20% lower carbon emissions and up to 30% cost savings when routes and payloads were optimized. Wind-aware planning and proper drone sizing further improved efficiency [60,71]. One study reported that large drones have lower emissions than diesel trucks for deliveries in rural areas. However, drones do not compete effectively with electric trucks due to high energy demand required for take-off and landing for each delivery [71]. Nevertheless, electric drones are economically more cost-effective than road-bound transport modes due to a high degree of automation and faster delivery times [71]. In addition, electric drones produce less emissions than diesel trucks, especially in rural areas [72]. Empirical testing of 188 quadcopter flights combined with first-principles analysis showed that electric quadcopter drone with 0.5-kg package consumes approximately 0.08 megajoules per kilometer [75]. This resulted in 70 g of carbon dioxide equivalent per package in the United States. Energy per package delivered by drones of 0.33 megajoules can be up to 94 percent lower than conventional transportation modes [75]. Only electric cargo bicycles provide lower greenhouse gas emissions per package. For emission-friendly operations, it is necessary to determine the optimal drone size, particularly for urban use cases [72]. This avoids exceptionally low landings for deliveries and prioritizes home deliveries instead of pick-up points.

A structured review of 59 academic articles examined environmental implications of drone-based delivery systems [74]. Sustainability strategies for small-scale farmers incorporated IoT devices for real-time tracking and machine learning algorithms for green compliance [73]. Overall, studies suggest that these systems support cleaner, faster, and more cost-efficient logistics. They can cut truck trips and strengthen sustainability in rural transport networks. In states such as ND, reducing the number of truck trips and promoting safe, efficient last-mile delivery through drones can significantly reduce overall emissions and enhance sustainability in the region.

3.6. Strategic Network Design

Network designs for hybrid truck–drone systems are enhanced through the use of GIS layers, remote sensing, and digital twins. Research emphasized design factors such as moving-hub trucks, in-route resupply, battery swapping, and multi-drone coordination [57,60,63,64,65,67,75,78]. Efficient routing and scheduling have been achieved using optimization algorithms that reduce delivery time and cost [57,63]. Policy-oriented studies addressed coordination and regulatory challenges for safe deployment of truck–drone systems [60,64].

In agriculture, UAVs enable precision spraying, crop monitoring, and mapping [65]. These applications improve input efficiency and sustainability [67]. AI-based systems enhance route optimization and real-time tracking. They support secure and faster deliver [75]. Advanced path-planning techniques further improve energy efficiency and operational safety [78]. These technologies can modernize the agricultural supply chain, making it faster, cost-effective, and resilient.

3.7. Data Security

Data security is a core requirement for GIS-enabled truck–drone logistics because coordination, scheduling, and routing decisions directly depend on the integrity of shared spatial and operational data. The reviewed studies show that smart-farm and UAV ecosystems face vulnerabilities in communication links, command-and-control channels, edge devices, and cloud platforms [8,54,78,80,81,82,84,85]. These weaknesses directly affect routing, monitoring, and strategic network design in hybrid systems. Several unresolved challenges apply specifically to GIS-based applications. First, data provenance remains difficult to guarantee because spatial layers originate from heterogeneous sources, including drones, trucks, satellites, and IoT sensors. Prior work highlights this challenge across smart-farm architectures that lack end-to-end verification mechanisms [8,54,84]. Without secure provenance controls, adversaries can inject falsified coordinates or altered layers into routing workflows. Second, location privacy is vulnerable across agricultural contexts. Studies emphasize that smart-farm data streams reveal operational patterns, asset locations, and production activities [8,84]. Continuous geolocation data enable inference of field conditions, inventory levels, and delivery schedules. This increases exposure to surveillance and targeted disruption. Third, GIS workflows remain susceptible to linkage attacks. Smart-farm and IoT reviews note that attackers can cross-reference publicly available imagery, environmental datasets, and sensor metadata to reconstruct sensitive operational details even when identifiers are removed [48,83,84].

More advanced threats include model inversion and adversarial manipulation of spatial layers. Research on UAV security and control-system vulnerabilities shows that attackers can reconstruct sensitive information from machine-learning outputs or alter inputs to mislead system behavior [81,82]. These findings extend directly to GIS-driven hybrid logistics, where adversarial modification of digital elevation models (DEMs), land-use layers, or road-network data could distort route optimization, altitude planning, and launch-site selection.

The potential impact of these threats is significant. UAV cybersecurity reviews show that adversarial control or spoofed coordinates can destabilize flight paths and compromise safety [81,82]. Smart-farm studies report that corrupted data streams can disrupt irrigation, sensing, and automated decision-making [8,54,85]. In GIS-enabled truck–drone logistics, similar attacks could misdirect drones into restricted airspace, route trucks onto unsafe roads, or cause incorrect energy estimates during challenging cold-weather operations [68,77].

Mitigation strategies described in the literature include secure communication protocols, authentication frameworks, privacy-by-design approaches, and local edge processing to minimize exposure to external threats [8,78,80,82,85]. Additional measures needed for GIS-based hybrid logistics include cryptographic tagging of spatial layers, anomaly detection for routing outputs, segmentation of command-and-control networks, and governance frameworks for data ownership and auditability. Without these safeguards, hybrid systems remain exposed to operational disruption, safety hazards, and regulatory risk.

In the context of North Dakota, these vulnerabilities could have serious consequences. Misrouted deliveries could result in chemicals being applied to the wrong fields, harming crops or the environment. Intentional manipulation of GIS data could cause drones to enter restricted airspace or trucks to take unsafe routes. Persistent exposure of location data could also allow targeted theft or disruption of farm operations. These risks highlight the critical need for strong security and privacy safeguards in ND hybrid truck–drone logistics.

3.8. International BVLOS Rules

The regulatory landscape for BVLOS operations varies by country. The USA currently does not have a formal BVLOS rule but approves them through waivers and exemptions. Visual observers are often required, and approvals are still granted case by case. In Canada, new BVLOS regulations became effective in March 2025, with four complexity levels defined with specific certificate and observer requirements. Cold-weather guidance also includes battery and thermal management measures. Australia adopted standardized BVLOS approvals earlier. Overall, Canada uses a performance-based system, while the United States depends on waiver-based approvals that remain restrictive and operator-specific.

3.9. Regional Research Gaps and Priorities

Systematic comparison of studied contexts with ND requirements reveals substantial research gaps. Hybrid truck–drone studies concentrated on urban and suburban last-mile delivery [56,63,64]. This is in contrast to ND’s dispersed agricultural landscape. Climate modeling addressed typical weather conditions [67], omitting extreme cold (−40 °F to −10 °F) affecting winter operations. Payload optimization focused on small parcels [42,71,74]. In contrast, agricultural inputs such as seed bags, chemicals, and equipment parts require heavier capacity [65]. Connectivity assumptions presumed cellular or broadband availability [33,37]. This ignores infrastructure limitations in rural areas [53].

These gaps result in three consequences. First, energy consumption models developed for moderate climates substantially underestimate cold-weather battery degradation [59,78]. This renders economic feasibility analysis unreliable for winter operations [77]. Furthermore, prior work in ND showed that sparse-network delivery inflates cost per drop due to long repositioning distances and limited aggregation opportunities [86]. These relationships indicate that hybrid systems become viable only when routing compresses repositioning mileage or when time-critical value offsets higher unit costs. Second, routing algorithms [1,57] optimized for concentrated delivery areas fail to address the cost structure of dispersed rural operations where individual farm deliveries span greater distances. Third, regulatory frameworks [60,64] emphasize urban airspace management rather operations across agricultural landscapes where BVLOS restrictions prohibit practical implementation. Overall, existing studies provided foundational concepts but did not evolve routing models, scheduling algorithms, or coordination architectures to operate under the combined constraints of extreme cold, ultra-low density, heavy payloads, and limited connectivity. This review identifies these gaps and establishes research priorities to enable practical deployment in cold-climate agricultural regions.

Table 4 links these region-specific challenges to findings in the literature, potential benefits of truck–drone systems, and remaining research gaps. Table 5 ranks the most urgent research priorities by their potential impact. Table 6 summarizes the technology gap assessment relative to coverage in the reviewed literature and ND requirements. The authors determined the priority levels in Table 5 based on an integrated assessment of the severity of the operational barrier in ND’s context (e.g., cold temperatures for nearly half the year), the degree that the current literature did not address this issue, and the potential impact on system feasibility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness. The authors scored each factor qualitatively during cross-comparison of the 81 peer-reviewed sources and aligned with stakeholder needs such as yield protection, delivery continuity, and system resilience.

Table 4.

ND context: Challenges and GIS-enabled truck–drone solutions.

Table 5.

Critical research priorities ranked by impact to ND.

Table 6.

Technology gap assessment.

Few studies address economic feasibility through cost–benefit analysis, multi-hub networks, or mobile launch strategies [1,15,70]. Heavy-payload drone development (10–50 kg) remains limited. This capability is essential for transporting inputs such as seed bags, fertilizers, and machinery components [43,66,69]. Additional constraints include harsh winters, road closures, high winds [22,60], and poor broadband access. The lack of cellular coverage necessitates alternative satellite-based communications [7]. Focused research in these areas is essential to enable practical and resilient drone delivery systems suited to ND’s climate and geography.

Most drone technologies to date have been designed for mild climates, light payloads, and high-density urban or suburban delivery. Consequently, they fall short in addressing cold-weather endurance, heavy-lift logistics, rural connectivity, and large-scale agricultural deployment. The severity of these challenges ranges from critical—such as battery efficiency and thermal management—to moderate issues like wind resistance and farm-scale routing. Accordingly, the top research priorities for drone delivery in ND include cold-weather battery performance, low-density delivery economics, regulatory approval for BVLOS operations, heavy-payload capability, connectivity solutions, and wind-adaptive flight planning. Reliable cold-weather batteries are fundamental to year-round operations. Economic modeling is needed to assess profitability in sparsely populated regions. Expanding flight permissions will be crucial to serve wide farm areas. Redundant communication networks will ensure safe remote operations. Finally, automatic routing adaptation that accounts for strong prairie winds in the region can improve both safety and efficiency. This will advance the practical adoption of drone-based logistics in ND’s agricultural landscape.

Although there are limited empirical cost data available specifically for ND, current research often highlights common themes when assessing economic efficiency. Studies show that hybrid truck–drone systems can optimize delivery for last-mile routes in low-density areas. However, this benefit should be weighed against capital and operational costs, including UAV acquisition, maintenance, charging infrastructure, and regulatory compliance. Life-cycle analysis models suggested that cost parity with truck-only models may be achieved when delivery frequency is low, but timeliness is critical (e.g., during planting season). Future modeling should account for delivery density (<2 per square kilometer), drone lifespan, energy cost, and potential time-based yield increase to determine break-even points for rural agricultural systems.

Table 7 shows a comprehensive review of studies on drone-supported agricultural logistics. It includes truck–drone coordination, rural delivery, smart agriculture, GIS, sustainability, and data security. Several studies show that hybrid truck–drone systems reduce cost and delivery time, especially in rural and sparsely populated areas. They reveal that GIS and spatial analysis are used for farm mapping, site planning, and resource management. Studies discuss how Drones, IoT, and AI support crop monitoring, irrigation, and efficient resources improve productivity. Sustainability studies show reductions in emissions and energy use when drones are combined with trucks. Data security and trust issues are critical for adoption. The literature provides guidance for infrastructure planning, delivery optimization, and policy design. For states with low population density and agriculture-based economies, such as ND, this review shows that farm efficiency can be improved, operational costs can be reduced, sustainability can be enhanced, and rural development can be supported. Hence, this study provides a foundation for future research on drone-assisted agricultural logistics.

Table 7.

A unified framework for drone-based agricultural logistics.

4. Discussion

While many prior works emphasized drone routing in urban environments, few addressed the operational challenges in ultra-low-density regions [67,76,77]. This review integrates insights into technological, regulatory, and environmental domains to produce a multidisciplinary perspective on hybrid agricultural logistics. The findings confirm that GIS plays a pivotal role in enabling truck–drone hybrid systems by providing the spatial intelligence needed for routing, launch site selection, and monitoring. These capabilities are particularly valuable for states such as ND, where long travel distances, low population density, and severe winters challenge conventional truck-based logistics. Studies in this review consistently show that hybrid systems shorten delivery times, extend service coverage, and improve operational flexibility compared with truck-only methods.

Integrating IoT, AI, and edge computing with GIS strengthens truck–drone coordination by enabling adaptive scheduling, synchronized dispatch, and real-time route replanning. Real-time sensing and predictive analytics allow delivery routes to adjust dynamically to weather, road closures, and farm demands. These technologies also support precise timing of input deliveries during critical planting and harvest windows. This reduces waste and increases productivity. GIS-enabled positioning for drone launch and recharge infrastructure ensures continuity of operations even under harsh environmental conditions.

From an economic perspective, hybrid systems demonstrate measurable advantages. Evidence from life cycle and operational studies in this review shows that drones can reduce fuel consumption and emissions for small, urgent deliveries while enhancing the efficiency of truck operations. Faster and more predictable delivery during peak agricultural seasons translates into higher yields and cost savings. This validates the potential of truck–drone systems to improve both sustainability and profitability in rural logistics. Moreover, life cycle assessments reviewed suggest that hybrid truck–drone systems can reduce delivery times by 25–40% and fuel consumption by up to 30% for short-range, high-priority deliveries [69,71,74]. These gains are especially relevant during peak agricultural seasons when timely input delivery affects yield outcomes and operational scheduling. Studies emphasize that drones are particularly effective for time-sensitive deliveries where quick access is critical and road conditions may impede traditional truck routes [58,77].

The review also highlights persistent technical, regulatory, and security challenges. Coordinating drones with moving trucks requires precise path planning and robust communication links. Federal restrictions on BVLOS operations remain a major barrier to scaling such systems in the United States. Additionally, battery limitations, payload constraints, and cold-weather performance issues reduce operational reliability. Cybersecurity risks, particularly those affecting communication networks and data exchange, could compromise both safety and farmer trust if not mitigated through secure and transparent governance frameworks.

Beyond their technical and operational dimensions, GIS-enabled truck–drone systems offer broader societal value. Use cases in humanitarian aid and healthcare logistics demonstrate their potential to strengthen rural resilience and emergency response. Integration with smart farming platforms aligns agricultural logistics with broader sustainability goals. This bridges data-driven strategic network design and environmental stewardship. Collectively, these insights position truck–drone systems as a foundation for next-generation precision logistics that combine efficiency, sustainability, and equity in service delivery.

Although GIS-enabled truck–drone systems demonstrate potential, significant negative impacts persist that constrain full-scale deployment. First, cold-weather degradation of drone batteries limits operability during almost half of the year in ND. This not only undermines delivery reliability but also leads to revenue loss during peak demand periods. Similarly, regulatory barriers such as BVLOS restrictions prevent efficient route design. This often forces suboptimal launch site placements and reduces delivery radius. Economically, the ultra-low-density delivery environment increases cost per delivery. This challenges the economic viability of systems designed for higher density use cases. Furthermore, the lack of reliable broadband impedes real-time GIS data updates and drone telemetry. This poses risks to both safety and efficiency. These challenges should be addressed in tandem through coordinated regulatory reform, hardware innovation, and rural connectivity initiatives. Emerging alternatives such as autonomous ground vehicles and electric trucks offer efficiency gains but remain limited by terrain accessibility and infrastructure needs. In contrast, hybrid truck–drone systems overcome these barriers through aerial flexibility.

5. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that GIS-enabled truck–drone hybrid systems can improve agricultural last-mile logistics in dispersed and cold-climate regions such as ND. By combining the long-haul efficiency of trucks with the flexibility of drones, these systems can shorten delivery times, lower costs, and extend service reach. GIS provides the spatial intelligence for routing, launch-site selection, and real-time monitoring. Furthermore, integrating GIS with IoT and AI supports predictive scheduling and data-driven strategic network design.

Despite these advances, several unresolved gaps constrain practical deployment. Current drones remain limited by cold-weather battery degradation, heavy-payload capacity, and BVLOS regulatory barriers. Insufficient broadband coverage and evolving cybersecurity requirements further challenge operational reliability. Addressing these deficiencies will require coordinated efforts among technology developers, policymakers, and researchers to design resilient platforms and adequate infrastructure.

The next research directions expand on the needs for field validation of cold-weather drone endurance, GIS-enabled optimization of hub and charging-station networks, evaluation of cost-benefit trade-offs under low-density delivery conditions, and the development of secure, adaptive communication frameworks. Pursuing these priorities will advance safe, efficient, and sustainable hybrid logistics that strengthen agricultural productivity and rural resilience in cold-climate environments.

6. Future Research

ND’s vast and sparsely populated agricultural landscape creates complex logistical challenges that conventional truck-based delivery systems struggle to address. Although GIS-enabled truck–drone hybrid systems present a promising solution, several research directions must be pursued to overcome existing technical, regulatory, and environmental limitations.

The highest priority is obtaining regulatory approval for BVLOS operations. ND’s low population density and limited airspace congestion make it an ideal testbed for agricultural BVLOS frameworks. Future studies should develop and evaluate operational protocols tailored to rural environments through collaborative pilot programs involving federal government agencies, state agencies, and research institutions.

A second major focus should be cold-weather resilience. Extreme winter temperatures between −40 °F and −10 °F require in-depth studies on battery chemistry, thermal management, and weather-adaptive flight planning. Field experiments across multiple seasons are needed to validate drone endurance and reliability in sub-zero conditions. Partnerships among universities, manufacturers, and national laboratories can accelerate advances in cold-tolerant power systems and components.

Third, GIS-enabled infrastructure optimization will be crucial to guide the placement of launch sites, mobile hubs, and charging stations. Spatial analyses should integrate road access, terrain, and seasonal constraints to design cost-effective and energy-efficient networks. Agricultural vehicles could serve as mobile drone hubs. These should be supported by renewable energy sources such as solar or wind power to improve autonomy and reduce operational costs. With these foundational elements established, future research should extend into four cross-cutting domains:

- Integration with precision agriculture: Research should link drone logistics with IoT-based soil, crop, and weather monitoring systems. The aim is to synchronize deliveries of inputs such as seed, fertilizer, and spare parts with field conditions in real time. Studies should also address heavy-payload capacity and battery recharging strategies to ensure reliable, year-round drone operations in cold climates.

- Cybersecurity and data governance: Studies must develop secure communication protocols and privacy-preserving data frameworks to build farmer confidence and protect sensitive operational data.

- Economic and financial modeling: Economic analyses are needed to assess system viability under low delivery densities. The analysis should evaluate cost savings, productivity gains, and potential business models across farm sizes.

- Environmental assessment: Life cycle analyses should quantify emissions reduction, energy savings, and road-use benefits compared with conventional transport to substantiate sustainability claims.

Collectively, these research priorities define a roadmap for implementing resilient, economically viable, and environmentally sustainable truck–drone systems in cold-climate agricultural regions. Through interdisciplinary collaboration and data-driven experimentation, ND can serve as a national model for advancing hybrid logistics in rural America.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; methodology, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; software, R.B.; validation, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; formal analysis, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; investigation, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; resources, R.B.; data curation, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; writing—review and editing, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; visualization, I.B., R.B. and E.A.T.; supervision, R.B.; project administration, R.B.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This article includes the data presented in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dai, D.; Cai, H.; Ye, L.; Shao, W. Two-Stage Delivery System for Last Mile Logistics in Rural Areas: Truck–Drone Approach. Systems 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guebsi, R.; Mami, S.; Chokmani, K. Drones in Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Applications, Technologies, and Challenges. Drones 2024, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgelall, R.; Askarzadeh, T.; Tolliver, D.D. Introducing an efficiency index to evaluate eVTOL designs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 191, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverhed, E.; Hellgren, S.; Isaksson, H.; Olsson, L.; Palmqvist, H.; Flodén, J. Autonomous Last-Mile Delivery Robots: A Literature Review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.P.O. Geospatial Technologies in Land Resources Mapping, Monitoring, and Management: An Overview. In Geospatial Technologies in Land Resources Mapping; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jebur, A.K. Uses and Applications of Geographic Information Systems. Saudi J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liang, Q.; Li, H.; Pang, Y. Application of Internet-of-Things Wireless Communication Technology in Agricultural Irrigation Management: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzai, W.K.; Abood, B.S.Z.; Al-Jawahry, H.M.; Obaid, M.K. Precision Farming: The Power of AI and IoT Technologies. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 3, 04006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, Y. LLM-QL: A LLM-Enhanced Q-Learning Approach for Scheduling Multiple Parallel Drones. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 5393–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Du, H.; Xu, J.; Huang, K.; Kim, D.I. Empowering Intelligent Low-altitude Economy with Large AI Model Deployment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.22343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Khorsandroo, S.; Mittal, S. Security and Privacy in Smart Farming: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, N.J.V.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual. 31 October 2023. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.20.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kurniadi, D.; Mulyani, A.; Septiana, Y.; Akbar, G.G. Geographic Information System for Mapping Public Service Location. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1402, 022073. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, M.; Wang, N. Precision Agriculture—A Worldwide Overview. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2002, 36, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Khattak, A.J.; Clarke, D. Non-Crossing Rail-Trespassing Crashes in the Past Decade: A Spatial Approach to Analyzing Injury Severity. Saf. Sci. 2016, 82, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Qin, T. Research on the Construction of Highway Traffic Digital Twin System Based on 3D GIS Technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1802, 042045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoulali, M. Utilizing Decision Support Systems for Strategic Public Policy Planning. In Public Policy and Administration; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nur, W.H.; Kumoro, Y.; Susilowati, Y. GIS and Geodatabase Disaster Risk for Spatial Planning. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 118, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E.; Jitprasithsiri, S.; Lee, H. Geographic Information System Technology and Its Applications in Civil Engineering. Civ. Eng. Syst. 1995, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Player, R.S.V. Geotechnical Use of GIS in Transportation Projects. In Geotechnical Engineering for Transportation Projects; American Society of Civil Engineers: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R.; Spiegel, P.B.; Henderson, A.K.; Gerber, M.L. The Application of Geographic Information Systems and Global Positioning Systems in Humanitarian Emergencies: Lessons Learned, Programme Implications and Future Research. Disasters 2003, 27, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.E. GIS and Remote Sensing Applications in Modern Water Resources Engineering. In Modern Water Resources Engineering; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 373–410. [Google Scholar]

- Depeweg, H.; Urquieta, E.R. GIS Tools and the Design of Irrigation Canals. Irrig. Drain. 2004, 53, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A. Applications of Geospatial Technologies for Practitioners: An Emerging Perspective of Geospatial Education. In Emerging Informatics—Innovative Concepts and Applications; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, M.; Jiang, H.; Luo, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Xie, T.; Zhang, Q.; Jahangir, Z. Cotton Cultivated Area Extraction Based on Multi-Feature Combination and CSSDI Under Spatial Constraint. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikusemoran, M.; Hajjatu, T. Site Suitability for Yam, Rice and Cotton Production in Adamawa State of Nigeria: A Geographic Information System (GIS) Approach. FUTY J. Environ. 2010, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayim, C.; Kassahun, A.; Addison, C.; Tekinerdogan, B. Adoption of ICT Innovations in the Agriculture Sector in Africa: A Review of the Literature. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Mohiuddin, A.S.M.; Ahmed, S.U.; Rahman, M.K.; Karim, M.A.; Saha, A.K. Suitability Assessment of Soils of Panchagarh and Thakurgaon for Tea (Camellia Sinensis L.) and Orange (Citrus Aurantium L.) Cultivation. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2020, 49, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cui, S.; Torrion, J.; Rajan, N. Data-Driven Precision Agriculture: Opportunities and Challenges. In Soil-Specific Farming; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 368–387. [Google Scholar]

- Usali, N.; Ismail, M.H. Use of Remote Sensing and GIS in Monitoring Water Quality. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 3, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, M.; Steduto, P. A GIS for Irrigation Management. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2003, 28, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.; Skvortsov, E.; Sharapova, V. The Study of the Advantages and Limitations, Risks and Possibilities of Applying Precision Farming Technologies. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 949, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, X. Precision Agriculture and Water Conservation Strategies for Sustainable Crop Production in Arid Regions. Plants 2024, 13, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanishree, K.; Nagaraja, G.S. Emerging Line of Research Approach in Precision Agriculture: An Insight Study. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, E.E.K.; Anggraini, L.; Kumi, J.A.; Karolina, L.B.; Akansah, E.; Sulyman, H.A.; Mendonça, I.; Aritsugi, M. IoT Solutions with Artificial Intelligence Technologies for Precision Agriculture: Definitions, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Electronics 2024, 13, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.A.; Short, N.M., Jr.; Roberts, D.P.; Vandenberg, B. Big Data Analysis for Sustainable Agriculture on A Geospatial Cloud Framework. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ammad-Uddin, M.; Sharif, Z.; Mansour, A.; Aggoune, E.-H.M. Internet-of-Things (IoT)-Based Smart Agriculture: Toward Making the Fields Talk. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 129551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, R.; Prabadevi, B.; Velvizhi, G.; Muthuraja, S.; Kathiravan, S.; Biswajita, M.; Madhumathi, A. Internet of Things and Machine Learning Applications for Smart Precision Agriculture. In IoT Applications Computing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; pp. 135–163. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D.; Stoican, F.; Stamatescu, G.; Ichim, L.; Dragana, C. Advanced UAV–WSN System for Intelligent Monitoring in Precision Agriculture. Sensors 2020, 20, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretto, A.; Aravecchia, S.; Burgard, W.; Chebrolu, N.; Dornhege, C.; Falck, T.; Fleckenstein, F.; Fontenla, A.; Imperoli, M.; Khanna, R.; et al. Building An Aerial–Ground Robotics System for Precision Farming: An Adaptable Solution. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2021, 28, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.; Ross, C.M.; Liu, B. A Review of Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Applications for Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2015 ASABE International Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–29 July 2015; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2015; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cerro, J.D.; Ulloa, C.C.; Barrientos, A.; Rivas, J.D.L. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Agriculture: A Survey. Agronomy 2021, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintus, M.; Colucci, F.; Maggio, F. Emerging Developments in Real-Time Edge AIoT for Agricultural Image Classification. IoT 2025, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balafoutis, A.T.; Evert, F.K.V.; Fountas, S. Smart Farming Technology Trends: Economic and Environmental Effects, Labor Impact, and Adoption Readiness. Agronomy 2020, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokov, R.S.; Lepekhin, P.P. Methods for Processing Data for Monitoring Condition and Use of Agricultural Areas. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 867, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, X. Improved Field Obstacle Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhafaji, M.A.; Ramadan, G.M.; Jaffer, Z.; Jasim, L. Revolutionizing agriculture: The impact of AI and IoT. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 491, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersink, A.; Fraser, E.; Pannell, D.; Duncan, E.; Rotz, S. Opportunities and Challenges for Big Data in Agricultural and Environmental Analysis. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, R.K.; Chandra, M.S.; Vivek, S.; Charankumar, G.R.; Chaitanya, J.; Alam, M.S.; Singh, P.K.; Ahlawat, P. The Prospect of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Precision Agriculture for Farming Systems Productivity in Sub-Tropical India: A Review. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.B.M.; Le, A.T.; Heo, S.; Chung, Y.S.; Mansoor, S. The Path to Smart Farming: Innovations and Opportunities in Precision Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Subasinghe, S.; Gamage, J.; Guruge, C.; Senaratne, S.; Randika, T.; Rathnayake, C.; Hameed, Z.; Madhujith, T.; et al. Advancing Sustainability: The Impact of Emerging Technologies in Agriculture. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 40, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimakopoulos, F.; Vassilakis, C.; Margaris, D.; Kotis, K.; Spiliotopoulos, D. AI and Related Technologies in the Fields of Smart Agriculture: A Review. Information 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Rashid, M.M.; Pasandideh, F.; Ray, B.; Moore, S.; Kadel, R. A Review of Applications and Communication Technologies for Internet of Things (IoT) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Based Sustainable Smart Farming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Singh, L.P.; Gupta, A.; Lohan, S.K. Advancements in Smart Farming: A Comprehensive Review of IoT, Wireless Communication, Sensors, and Hardware for Agricultural Automation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 362, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Finger, R.; Huber, R.; Buchmann, N. Smart Farming Is Key to Developing Sustainable Agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, B.; Ndiaye, M. Hybrid Truck-Drone Delivery Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 92854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayarian, I.; Savelsbergh, M.; Clarke, J.-P. Same-Day Delivery with Drone Resupply. Transp. Sci. 2020, 54, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, A.; Takawira, B.; Mbhele, T.P. Resilience in the Last Mile: A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainable Logistics in South Africa. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbelli, F.B.; Corò, F.; Palazzetti, L.; Pinotti, C.M.; Rigoni, G. How the Wind Can Be Leveraged for Saving Energy in A Truck-Drone Delivery System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, C.; Wandelt, S. Policy Challenges for Coordinated Delivery of Trucks and Drones. J. Air Transp. Stud. 2024, 2, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karar, M.E.; Alotaibi, F.; Rasheed, A.A.; Reyad, O. A Pilot Study of Smart Agricultural Irrigation Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and IoT-Based Cloud System. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2021, 10, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, H.S.; Mahieddine, F.; Sheriff, R.E. Technology Impact on Agricultural Productivity: A Review of Precision Agriculture Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In International Conference on Wireless and Satellite Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tausif, I. Last Mile Delivery Optimisation Model for Drone-Enabled Vehicle Routing Problem. Emerg. Minds J. Stud. Res. 2023, 1, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Jung, H. Drone-Assisted Multimodal Logistics: Trends and Research Issues. Drones 2024, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.C. Employing Drones in Agriculture: An Exploration of Various Drone Types and Key Advantages. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.04037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezei, J.F.; Freitas, C.R.D.; Neto, A.L.; Rodrigues, P.C.C.; Luche, J.R.D. Strategic Analysis for A Truck-Drone Hybrid Model in Last Mile Delivery. Int. Contemp. Manag. Rev. 2024, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavarpour, N.; Koparan, C.; Nowatzki, J.; Bajwa, S.; Sun, X. A Technical Study on UAV Characteristics for Precision Agriculture Applications and Associated Practical Challenges. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tupayachi, J.; Sharmin, A.; Ferguson, M.M. Drone-Aided Delivery Methods, Challenge, and the Future: A Methodological Review. Drones 2023, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgelall, R. Spatial Analysis of Advanced Air Mobility in Rural Healthcare Logistics. Information 2024, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; Chu, J. The Future of Last-Mile Delivery: Lifecycle Environmental and Economic Impacts of Drone-Truck Parallel Systems. Drones 2025, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunatha, A.; Lindkvist, E.; Thollander, P.; Hansson, E.; Jonsson, G. Critical Assessment of Emissions, Costs, and Time for Last-Mile Goods Delivery By Drones Versus Trucks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, M.; Karimi, F.; Khalilpour, K. Green Logistics for Fresh Produce Farming: Barrier Analysis and Opportunity Mapping for Retail Markets. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prybutok, V.; Sangana, V.K.R. Environmental Implications of Drone-Based Delivery Systems: A Structured Literature Review. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Patrikar, J.; Oliveira, N.L.; Matthews, H.S.; Scherer, S.; Samaras, C. Drone Flight Data Reveal Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Savings for Very Small Package Delivery. Patterns 2022, 3, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, M.; Shrivastav, U. Optimizing Delivery Logistics: Enhancing Speed and Safety with Drone Technology. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.17253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Gupta, P.; Mahajan, N.; Balaji, S.; Singh, K.J.; Bhargava, B.; Panda, S. Implementation of Drone Based Delivery of Medical Supplies in North-East India: Experiences, Challenges and Adopted Strategies. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1128886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugan, G.; Haque, A. Path Planning for Autonomous Drones: Challenges and Future Directions. Drones 2023, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, J.I.; Tu, C.; Owolawi, P.A.; Du, S.; Plessis, D.D. Review of Animal Remote Managing and Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, Osaka, Japan, 17–19 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Matero, C.A.; Jumawan-Matero, M.J. Smart Farming Innovations for Philippines: Strategies and Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Accounting, Management and Entrepreneurship, Cirebon, Indonesia, 26 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi, A.; Pinkley, S.N.; Mes, M. A Markov Decision Process Approach for Managing Medical Drone Deliveries. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tychola, K.A.; Rantos, K. Cyberthreats and Security Measures in Drone-Assisted Agriculture. Electronics 2025, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Taylor, B.; Fleming, A.; Mason, C.; Fielke, S.; Sounness, C.; Thorburn, P. “If They Don’t Tell Us What They Do with It, Why Would We Trust Them?” Trust, Transparency and Benefit-sharing in Smart Farming. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90, 100285. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno, M. An Extensive Survey of Smart Agriculture Technologies: Current Security Posture. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 18, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pappachan, P.; Gupta, B.B.; Hsu, C.-H. Privacy-centric AI and IoT Solutions for Smart Rural Farm Monitoring and Control. Sensors 2024, 24, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgelall, R. Spatial Analysis of Middle-Mile Transport for Advanced Air Mobility: A Case Study of Rural North Dakota. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, S.; Li, Z. Research on Collaborative Delivery Path Planning for Trucks and Drones in Parcel Delivery. Sensors 2025, 25, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).