Abstract

Drone-aided networking is considered a potential candidate for internet of things (IoT) networking in 5G and beyond, where drones are deployed to serve a large number of devices simultaneously for data collection, surveillance, remote sensing, etc. However, challenges arise due to massive connectivity requests as well as limited power budgets. To this end, this paper focuses on the design of drone-aided IoT networking, where a drone access point serves a large number of devices for efficient data transmission, collection, and remote sensing. Constant envelope signaling such as minimum shift keying (MSK) family is considered to avoid potential significant power inefficiency due to nonlinear distortion. To this end, code-domain non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) is developed and analyzed in terms of achievable sum spectral efficiency. Further, power allocation is derived based on the aforementioned analysis and is demonstrated to offer significantly improved performance in terms of sum spectral efficiency and user load. Simulation results confirm the feasibility of the proposed design and shows that the designed system can attain the promised performance using either simple convolutional code or complex polar code. The proposed system can be used in scenarios such as deep space communications, where MSK family signaling is adopted as well.

1. Introduction

The fifth generation (5G) and beyond is expected to significantly improve the spectral efficiency while supporting billions of devices globally in the near future [1]. This is envisioned as the massive machine type communications (mMTC), a typical internet of things (IoT) scenario that has emerged in smart homes, industrial automation, integrated IoTs, etc. [2], where drone-aided IoT (DIoT) netwoking has recently proved to be a promising technique [3]. However, challenges to deploy DIoT have arisen [4,5]. One such problem is to enable ultra-dense IoT networking based on minimum shift-keying (MSK) signaling, which is widely adopted in IoT standards including IEEE 802.15 series and drone data-link standard [2,6].

One of the prominent enablers is nonorthogonal multiple access (NOMA), where users (devices) are differenated using a signature in power domain or code domain [7]. The choice of signatures gives birth to a variants of renowned NOMAs. For example, in [8,9], the authors demonstrated the optimality of using simple forward error corrections (FECs) such as convolutional codes alone as the signature and suggested dedicating the whole redundancy to coding gain for maximum interference mitigation. However, this gain is harvested using maximum-likelihood detection (MLD), which has prohibitively high costs in practice. Fortunately, the complexity is successfully reduced if interference cancellation applies [10,11]. These results inspired the development of diverse code domain NOMAs for large scale systems, where the signature is typically a concatenation of high rate FEC and repetition (REP) coding (or spreading equivalently) [12]. Though it provides no coding gain, REP is considered indispensable for effective multiuser interference (MUI) mitigation and high user loads [13]. However, such benefits are collected at the expense of extremely low spectral efficiency (SE) of each individual, which is identified as the coding-spreading dilemma in NOMAs that potentially undermines the application of NOMA in 5G and beyond [7,14]. Some recent proposals addressed this issue by designing REP-free schemes [15,16]. Though the individual SE is improved, not to mention the non-scalability of the designs, the user load is reduced drastically. The coding–spreading tradeoff deserves further treatment.

Another issues arises as IoT evolves to integrate arial platforms to offer seamless coverage globally [7]. In such a system, low power consumption is desirable since the platforms have very limited access to sustainable power supplies, such as sensors, drones, satellites etc. [17]. Therefore, standards concerning low power IoT networking favor continuous phase modulation (CPM) over conventional schemes such as phase shift keying (PSK) for improved power efficiency [18,19,20]. As a special case of CPM, minimum shift keying (MSK) has been recognized as one of the major waveforms for low power IoT networking [21,22]. The development of MSK-based NOMA gained extensive attention in the context of frequency division multiple access (FDMA) [23,24,25,26]. As the term FDMA implies, users are allocated to different frequency bands separated by frequency-spacing. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the MUI rapidly becomes irremediable as the frequency spacing approaches zero, i.e., multi channels collapse to a single channel even when the user load barely exceeds two [23]. In this sense, FDMA-CPM can hardly be employed in mMTC.

Though it appears that MSK-based massive IoT networking has not been well established yet, we notice that NOMA and FDMA-CPM are complementary, i.e., the former offers high user load but experiences low individual SE while the latter is exactly the contrary. It is natural to wonder about the possibility of designing a NOMA scheme that has the advantages while avoiding the shortcomings. This motivates the development of nonorthogonal coded modulation (NCM), a potentially massive connectivity enabler for MSK-based low power IoT networking. Some of the research, along with their research focus and limitations, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Related research.

As can be seen from the discussion presented later, the motivation is well fulfilled. More appealingly, the proposed NCM outperforms NOMA and FDMA-CPM due to the following properties:

- High SE. The proposed NCM offers sum SE and individual SE up to 15 bits/s/Hz and 0.5 bits/s/Hz, respectively, while the gap to multiple access channel (MAC) capacity is narrowed down to 2 dB in all cases considered.

- Low latency. Low latency is naturally obtained due to the high code rate and is further enhanced using low complexity FECs such as -CC or -REP to keep the processing delay as short as possible.

- Scalability. The proposed design criteria are put forward in terms of signal shaping, consisting of ideal power allocation (IPA) and phase spacing technique (PST), that is proven to offer near-capacity performance irrespective of the varying user load K.

Though the proposed NCM is exemplified using CC and MSK, the results show that the design can be applied to linear block FECs such as polar code [27] and partial response signaling such as Gaussian MSK (GMSK). It did not came to our attention that similar schemes have been previously addressed. The rest of this paper consists of five sections. In Section 2, we present the system model of NCM. In Section 3, we derive the iterative receiver. In Section 4, we present IPA and PST. In Section 5, we present numerical results, and Section 6, concludes the paper.

2. Nonorthogonal Coded Modulation

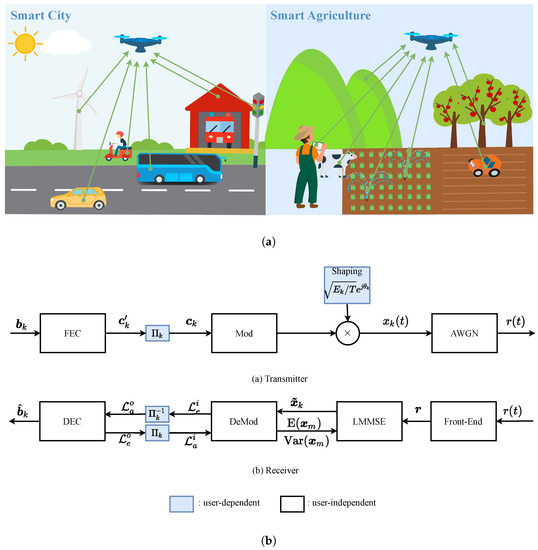

In Figure 1a, two typical DoT networks are demonstrated where a drone is used to collect data or perform remote sensing in smart cities and agriculture based on massively deployed sensors and devices. The equivalent parameterized model is presented in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) Drone-aided IoT networking. (b) Nonorthogonal coded modulation. DIoT scenarios and equivalent models.

2.1. Introduction to NCM

Without loss of generality, the whole process is exemplified using the k-th user as depicted in Figure 1b. On the transmitter side, the L-bits long information is first encoded by a FEC of rate , producing an N-bits long codeword . Then, passes through an interleaver , generating the sequence fed to MSK modulation. The resultant MSK signal is expressed as

where is the energy per transmitted symbol, is the phase offset, T is the symbol duration, and . The collection of all possible is defined as the alphabet .

The information-bearing phase admits a titled-phase expression as [28]

where and . Just as indicated in (2), is partial response, as is . MSK modulation is thus well described by a trellis , whose state-space is . As should be noticed, takes only two possible values: 0 and .

It is worth mentioning that the interleaving and signal shaping—the shaded blocks in Figure 1b—are combined jointly to facilitate the user separation at the receiver side. In this paper, we are more concerned with the shaping technique, while the interleavers are randomly generated with no special design.

2.2. Multiple Access Channel

Assuming user load K, the received signal reads

where is additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) with being the double-sided power spectral density (PSD) and is the multiuser interference experienced by the k-th user. They jointly constitute the interference-plus-noise . With the aid of orthogonal decomposition obtained from principal component analysis (PCA) [28], an equivalent discrete expression is obtained

where , , and are vectors in .

Based on the Gaussian assumption (GA) [29], is interpreted as an AWGN independent of , where the mean and variance, respectively, are easily calculated as

where is used. The achievable sum SE is obtained by solving the following formula [29]

where is the energy per information bit. It turns out that is identical to the single user system and increases linearly in the high signal to noise ratio (SNR) region as

That being said, the sum SE increases by bits/s/Hz asymptotically if increases by 1 dB.

3. LMMSE Aided Interference Cancellation

The achievability of depends on the effective mitigation of MUI at the receiver that can be implemented by coupling LMMSE and successive interference cancellation (SIC) [29,30]. This method is adopted as well in this paper and the LMMSE-SIC receiver is developed in this section accordingly.

3.1. LMMSE Interference Suppression

As shown in Figure 1b, the received signal is filtered to obtain an interference-surpassed estimation expressed as [10,30]

where the LMMSE coefficient is expressed as

where

is due to GA.

The refined signal is per definition, where the mean and variance , respectively, are

As perceived, the calculations above are intricate due to the involved matrix operations. Thanks to PCA and GA, the calculations are made element-wise, as

where . The component mean and variance needed are fed from MSK demodulation, which is addressed latter.

Using this estimation, the resultant mean squared error (MSE) is expressed as [30]

and the minimum squared error (MSE) becomes negligible if reliable a priori information regarding is accessible. The details are presented below in Lemma 1.

Lemma 1.

MSE admits an element-wise expression and approaches 0 as .

Proof of Lemma 1.

See the Appendix A. □

3.2. Iterative Demodulation and Decoding

From the perspective of coding theory, the concatenation of FEC and MSK forms a serially concatenated coded modulation system [31], where MSK demodulation and decoding modules are both a posteriori probability (APP) decoders [32]. Hence, iterative demodulation and decoding are used to generate for near perfect IC.

Again, we take the k-th user as an example. The MSK demodulator, i.e., inner decoder, is a four-port module that performs over the trellis defined in Section 2.1. It accepts and the a priori log-likelihood ratios (LLRs) and outputs the extrinsic LLRs and regarding and , respectively [31,32].

More specifically, concerning is calculated as

where is the probability of state transition from s to driven by . It is calculated using alone as

where and are defined in (13) and (14), respectively. The second line is obtained since is diagonal, and whose i-th eigenvalue is as presented in Appendix A.

Similarly, the LLR regarding is calculated in parallel to as

where is specified for LLR normalization and is calculated using alone as

where a dummy variable is used to simplify the expression.

The quantities and are obtained through the forward and backward recursions, respectively, as

where , which indicates the probability of state transition using information from the channel and outer decoder jointly. Once is obtained, it is fed to the outer decoder, i.e., FEC decoder, to obtain the a priori LLRs of outer code .

The FEC decoder is still a four-port APP decoder, except it only receives a priori information from the MSK demodulator. If the FEC is CC, the whole process is essentially identical to MSK demodulation. With a slight abuse of trellis notation, the extrinsic LLR regarding is calculated as

where the forward and backward recursions are calculated as

and is defined as

where indexes all the coded bits, except for .

For REP, the extrinsic LLR is simply

where indexes all the coded bits, except for . is then sent to MSK demodulation to serve as the a priori LLRs .

The exchange of and iterates for -times to obtain reliable extrinsic LLRs and finally output the mean and variance regarding as

where and if reliable is accessible.

In fact, reliable is obtained even without resorting to advanced FECs. In NCM, two simple FECs are considered: CC and REP. The complexity of the whole process can be roughly estimated from the number of branches processed in each symbol interval, which are eight, four, and two for CCs, REPs and MSK, respectively. Then, the complexity is expressed with respect to the number of transmitted information bits within each block as

It is seen that CC-NCM is twice as complicated as REP-NCM. However, the high complexity is well paid off, seeing the fact that CC-NCM offers extra gains, as shown in Table 2. The results are a straightforward application of the theory in [31,32].

Table 2.

A comparison of CC-NCM and REP-NCM.

However, the feasibility of CC-NCM is questionable since it was repeatedly observed that strong coded modulations offer low user load in contrast to weak coded modultions such as REP-NCM [13,16]. To solve this issue, signal shaping is proposed.

4. Signal Shaping: Design and Performance Analysis

It is seen that MSK demodulation plays an important role in NCM since it is the intermediate block feeding extrinsic information to both the LMMSE filter and the FEC decoder. Therefore, the signal shaping is developed starting with simple error performance analysis of the MSK demodulation. Assuming sequence is transmitted, an error occurs if a different sequence is favored. Using the definitions in (9) and (19), the decision variable is expressed as

where is the LMMSE estimation of and is the priori LLRs fed from the k-th FEC decoder. The decision variable is decomposed into three components: , , and , where the performance is dominated by since the first two are barely affected by MUI. Here, is termed the effective MUI and is interpreted as a disturbance to the decision variable that is quantified through the normalized variance , which leads to the development of ideal power allocation (IPA) and phase spacing technique (PST) in sequel.

4.1. Ideal Power Allocation (IPA)

Lemma 2

(IPA and ). Without using PST, is expressed as

where is the error probability of the m-th user. thus virtually behaves no differently, no matter the power allocation scheme, if is not available.

Proof of Lemma 2.

See Appendix B. □

A typical situation happens when the SIC is just launched. This is the worst case that bottlenecks the performance. However, we do observe that decreases as reduces, which motivates the IPA elaborated in the following explanation.

Assuming the target individual SE is , then for the k-th user, the required minimum SNR using an ideal coded modulation is

where given . It is observed that no power allocation scheme can fulfill (35) for K users simultaneously. However, assuming that SIC perfectly estimates the first users and recalling the GA, the k-th user only experiences MUI coming from the -th to K-th users, and is thus expressed as

where is neglected. A feasible power allocation is setting for , where the optimal ratio is . As long as the SIC cancels MUI in sequence successfully, (35) always holds, and enables gradually reduced as expected.

With regard to NCM, FECs are required to have to offer individual SE of bits/s/Hz since the bandwidth of MSK is 1.2. Hence, FECs in Table 2 are periodically punctured to obtain . We term this as the match of R to IPA. As such, a simple observation is that the total power increases by 3 dB as the sum SE increases by bits/s/Hz whenever the user load K increases by one, i.e.,

which is well aligned to the prediction in (8). Seeing this, we say that this operation is asymptotically optimal as .

There are two cases that deserve further exposition, namely optimal with suboptimal and optimal with suboptimal R, which both incur performance loss in terms of SNR. As to the former, we only need to consider under-power and over-power in general, where and , respectively. It is readily perceived that the under-power system cannot achieve the target SE as indicated in (35), while the over-power system fulfills (35) but incurs SNR penalty in contrast to . This penalty is expressed as

where . The case with is equivalent to equal power allocation (EPA) that will be discussed soon.

As to the latter, SNR penalty is expressed as

where to make sure and to offer the same sum SE.

4.2. Phase-Spacing Technique (PST)

The IPA bypasses the reduction of , which is now formally addressed by PST. PST was previously adopted in [22] and is proved to increase spectral efficiency significantly. In NCM, we are interested in the following simple generation of

An exhaustive search of the optimal was previously presented in [23,26] which is not suitable for large scale systems. In this section, the optimal is derived using the theory presented in [22], as stated in Lemma 3.

Lemma 3

(Optimal phase spacing). Given phase-spacing

where is the error probability of the m-th user and . Using offers gain over the system using IPA alone.

Proof of Lemma 3.

See Appendix B. □

Comments 1.

Applying this approach, i.e., and , to quadrature PSK (QPSK), the result shows that

which simply suggests using PST in QPSK gains no reduction ultimately since . This interesting result implies that PST should be coupled with the eligible modulation format to deliver expected reduction of .

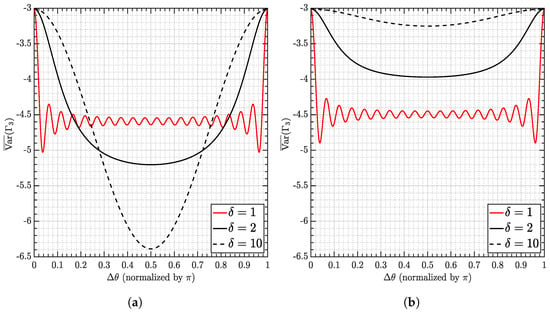

The discussion is exemplified in Figure 2, where versus (in dB) are evaluated assuming . Three systems are considered: , , corresponding to EPA, IPA, and over-power systems, respectively. It is firstly noticed that dB in all three cases without PST (), justifying the claim in Lemma 2. When PST applies, the strongest user obtains significant reduction in all three cases as shown in Figure 2a. This reduction is up to dB in IPA and is at least dB in EPA. As to the weakest user, the reduction is limited. As a matter of fact, EPA outperforms the other two systems with or without PST. This observation justifies the successive detection order . Nevertheless, average reduction can still be obtained as claimed in Lemma 3. From the perspective of iterative decoding, the reduction provides a good start to initiate the whole process that would relax the requirements regarding ideality of NCM.

Figure 2.

(a) . (b) . Performance of a 20−user NCM system in the cases of EPA (), IPA (), and over-power (). Both the strongest () and the weakest () users are evaluated.

The effective noise is also evaluated for small-scale systems. The results are presented in Figure 3 with . It is observed that the performance remains invariable disregarding the increasing . This result suggests that in small-scale systems, PST alone can offer the same reduction of with or without IPA. This conclusion can also be derived from the definition of (41), which is solely determined by . Equivalently, we say that the proposed signal shaping technique consisting of IPA and PST offers asymptotically optimal performance when .

Figure 3.

vs. .

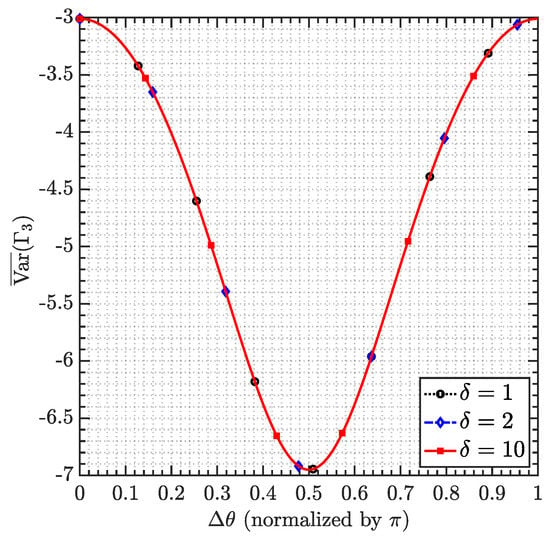

Another concern is that the proposed signal shaping relies on phase spacing. It is thus natural to ponder the robustness of PST against phase misalignment. This situation is considered in Figure 4, where is a suboptimal replacement of . When -, there is no misalignment, and hence, reaches the lowest value. Otherwise, increases. However, the increment is limited to around 1 dB, suggesting that the misalignment does not lead to significant performance loss. This behavior holds disregarding the user load K, implying that robustness against phase alignment may be due to a number of situations such as phase noise, estimation error, etc.

Figure 4.

vs. -.

Comments 2.

The results imply that using IPA or PST alone can hardly deliver the best performance. They should be coupled together. However, this coupling does not pledge performance improvement unless the underlying waveform is properly chosen, just as the comment regarding QPSK. This observation is another reason for the term NCM.

5. Numerical Results

The previous discussion is exemplified in terms of bit error rate (BER) versus , convergence behavior, and achievable SE. In this section, the blocklength in all cases unless stated otherwise. For better validation, some parameters are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation parameters.

5.1. Ideality of CC-NCM and REP-NCM

The discussion begins with examining the ideality since IPA presumes ideal coded modulation. The ideality of coded modulation is measured through BER and convergence behavior in terms of threshold [33].

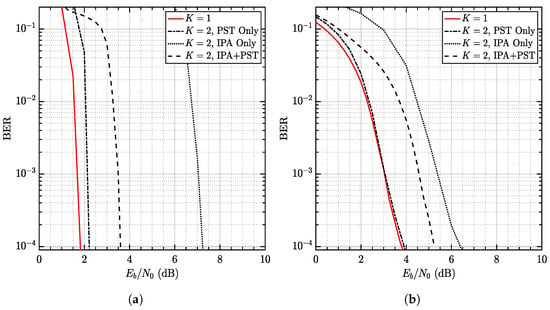

Results concerning two-user systems are presented in Figure 5. It is seen that both CC-NCM and REP-NCM successfully load up to two users. The gap to the single-user system can be reduced to within dB. However, the performance varies, as shown in Figure 5a. More specifically, in CC-NCM, the dB gap is obtained using PST alone while the gap increases to dB and dB when using IPA + PST and IPA alone, respectively. A similar behavior is also observed in REP-NCM, as shown in Figure 5b. While IPA offers performance nearly identical to the single user system, IPA + PST is dB away.

Figure 5.

(a) CC-NCM. (b) REP-NCM. Comparison of CC-NCM and REP-NCM when and .

Though it is evident that IPA and PST are both effective in suppressing MUI, it appears that IPA + PST does not deliver the best performance. The reason is that IPA is developed presuming ; therefore, IPA is not energy-efficient when K is small.

This gap is predictable using a method similar to (38), i.e., the gap of the two-user IPA + PST is approximately dB, which justifies the dB/ dB gap. When comparing CC-NCM with REP-NCM, a gap of 2 dB is observed when IPA + PST applies.

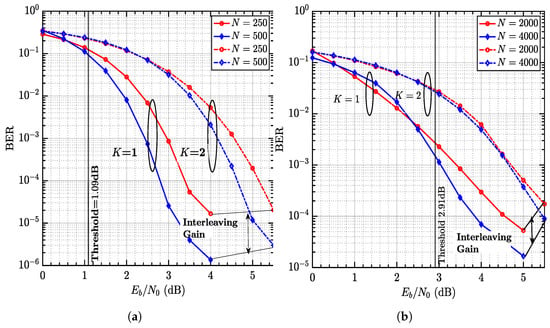

This gap is explained in Figure 6, where the interleaving gains are detailed. The results confirm that REP-NCM does offer interleaving gain, as analyzed in Table 2. The performance obviously underperforms CC-REP since no coding gain is obtained. This result is also confirmed by the convergence threshold [33], which suggests that the threshold of REP-NCM is 2 dB higher than CC-NCM, just as the BER curves imply in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Therefore, we come to the conclusion that CC-NCM is more ideal than REP-NCM and is hence extensively discussed in the sequel.

Figure 6.

(a) CC-NCM. (b) REP-NCM. Comparison of CC-NCM and REP-NCM in terms of interleaving gain and convergence threshold. They both employ IPA + PST and the vertical lines indicate the respective thresholds.

5.2. Match R to IPA

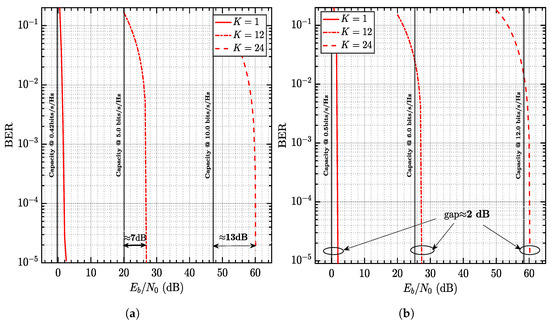

It is pointed out in Section 4 that and should be mutually matched to attain an individual SE of 0.5 bits/s/Hz. Otherwise, significant loss in terms of will be incurred. This is exemplified by the CC-NCMs without (Figure 7a) or with puncturing (Figure 7b). The results are shown in Figure 7. When is used for both systems, the gap to MAC capacity is up to 13 dB without puncturing while the gap narrows down to 2 dB with puncturing. We see a 11 dB difference, which is well predicted by (39).

Figure 7.

(a) CC-NCM without puncturing. (b) CC-NCM with puncturing. Comparison of CC-NCM without or with puncturing. The MAC capacities are indicated by the vertical lines. .

It is worth noticing that the parameters and offer near-capacity performance irrespective of K varying from 1 to 24. The scalability of NCM is confirmed. This is a valuable property seeing that most existing NOMAs are configured on a case-by-case basis. The reason is that both IPA and PST are developed assuming which guarantees the performance for large-scale systems.

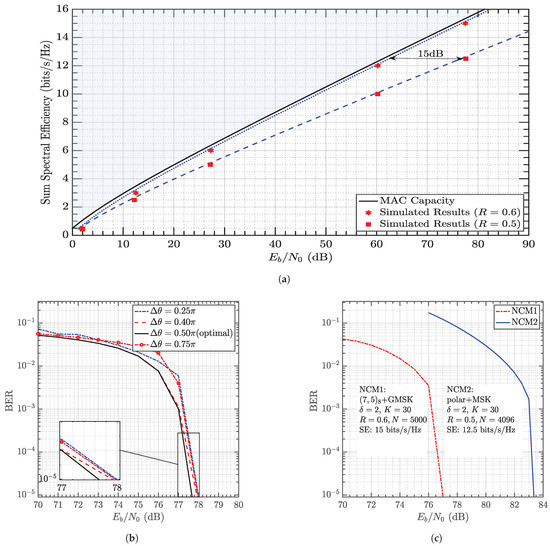

5.3. Achievable Spectral Efficiency

The achievable spectral efficiency of the CC-NCM is examined when BER in Figure 8a for both punctured () and unpunctured () systems. The user load K takes on 1, 6, 12, 24, and 30. It is readily observed that when , NCM well approaches MAC capacity within 2 dB, confirming the observation in Figure 7b and demonstrating both the energy-efficiency and spectrally-efficiency of the proposed design. However, when , a huge gap is observed. This gap is exactly due to the mismatch between R and IPA and is well predicted using (39), which is up to 15 dB when . This gap keeps increasing as .

Figure 8.

(a) The achievable sum SE of CC-based NCMs with () or without () puncturing. (b) The BERs vs. . The sum SE is 15 bits/s/Hz, (c) The BERs of polar and CC coded NCMs. The achievable sum SE of NCMs of different configurations.

Fortunately, such high SE can be obtained as well, even if the phase spacing is configured suboptimially as predicted in Figure 2a and Figure 4, where remains almost constant when . This observation is confirmed in the simulated BERs shown in Figure 8b. Just as in Figure 8a, we consider a CC-based NCM of SE 15 bits/s/Hz (). As expected, the best performance is obtained using while the performance degrades slightly when as predicted in Figure 4. More interestingly, the performance is essentially identical when and , which is also predicted in Figure 2a. These observations naturally lead to the conclusion that NCM is robust against phase errors due to inaccurate estimation, etc., that would be useful in practice.

Further, the proposed NCM can be easily applied to FECs and CPMs beyond CC and MSK. For example, polar code [27] and partial response CPM GMSK are considered in Figure 8c. Thanks to the shaping technique developed, both NCM1 and NCM2 can offer a user load K up to 30 achieving SE of up to 15 bits/s/Hz and bits/s/Hz, respectively. It is readily observed that the proposed technique is versatile given linear block FEC or partial response signaling. However, we still recommend CC for reduced processing complexity since the primary concern is low power consumption.

5.4. Remarks

It is noticed that most existing NOMAs offer a normalized overloading factor that barely exits 10, while NCM can easily reach 18 or perhaps even higher with capacity-approaching performance. Such performance does not require low-rate FECs, which significantly reduces complexity and latency. The numerical results justified our design successfully. However, it is necessary to rethink the idea behind this success since it recommends radically different guidelines. For example, the proposed design is derived from large-scale systems, but is also proven effective for small-scale systems. This is different from the current method, where the optimization starts with low user load and hopes that the resultant configuration will be extendable in large-scale systems—which turns out to not be true in most cases. Another observation is that high-rate strong codes (We emphasis that the code here does not refer to the FEC but the concatenation of FEC and MSK, since it forms a turbo-like coded modulation that is more ideal than FEC alone) are proven to be more useful and able to avoid the coding–spreading tradeoff. This choice is also different from most existing code domain NOMAs, where low-rate weak codes are preferred to strike a good tradeoff between coding and spreading gains [13,14].

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a class of nonorthogonal multiple access scheme, i.e., NCM, for drone-aided IoT networking to potentially enable massive connectivity. The performance of NCM is analyzed in terms of effective multiuser interference, which leads to the discovery of asymptotically optimal power allocation, phase spacing, and rate selection. As a result, a user load K of up to 30 is achieved by the exemplified systems, which justifies our design for enabling massive connectivity using low power IoT. While we resort to routine technique power allocation to obtain such performance, it is further revealed that NCM requires a very high code rate (≤0.6) to enable improved user load. Such a mechanism is preferred even though high-rate coding was recognized to be incompetent for mitigating multiuser interference. Our discussion offers new insights into this recognition and proves that low-rate coding is not indispensable for mitigating severe interference in the context of coded modulation, which turns out to be a solution to avoid the coding–spreading tradeoff. This valuable property not only enables mMTC of low power IoT devices but also offers low latency, which both are desired in 5G and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.; methodology, L.B.; software, L.H.; validation, L.H., Y.G. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, Y.G.; investigation, L.H.; resources, Y.Y.; data curation, L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, L.B.; visualization, L.H.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, L.B.; funding acquisition, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61601346, and the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China under Grant 2018JQ6044, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China under Grant 2021-0162-1-1, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Northwestern Polytechnical University, under Grant 31020180QD089, the Aeronautical Science Foundation of China under Grant 20200043053004 and 20200043053005.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DIoT | drone-aided IoT |

| MSK | minimum shift keying |

| GMSK | Gaussian MSK |

| PSK | phase shift keying |

| CPM | continuous phase modulation |

| SNR | signal to noise ratio |

| SE | spectral efficiency |

| FEC | forward error correction |

| NCM | nonorthogonal coded modulation |

| REP | repetition |

| CC | convolutional code |

| AWGN | white Gaussian noise |

| PSD | power spectral density |

| PCA | nonorthogonal coded modulation |

| GA | Gaussian assumption |

| SIC | interference cancellation |

| MSE | mean squared error |

| APP | a posteriori probability |

| LLR | log-likelihood ratio |

| BER | mean squared error |

Appendix A

In this appendix, we present the proof of Lemma 1 and the results concerning (19). First comes the proof of Lemma 1. As can be seen the the major concern is , which is explicitly expressed as

where if due to the orthonormal expansion in PCA [28].

Therefore,

where .

Since , i.e., MSE reaches minimum when , which is made possible given reliable because

where , which denotes the power projected onto the i-th dimension; is the average probability of error of the m-th user and is a tentative decision rather than . Given , we have

where the function does not admit a closed-form expression in general but monotonically decreases with respect to [33]. As a result, , and thus, when .

Now, MSE is expressed as

It is identified that admits the eigendecomposition with being the i-th eigenvalue. The inverse is simply

where the th eigenvalue of is , which approaches 1 in high SNR region when due to reliable .

Appendix B

In the high SNR region, the AWGN is negligible, and hence [22],

where is used. Considering the fact that and are independent but identically distributed, we have

where we define . Recall the expression of titled-phase (2), we define , and to obtain

Since and , a closed-form expression is obtained as

and it reaches a minimum value when . Otherwise, when .

For large-scale systems, the explicit calculation is intricate. Fortunately, there are two facts that can be used to reduce the complexity, namely, has a period and two cases, i.e., , are needed when according to (40). Therefore [22],

and thus,

Proof of Lemma 2 and Lemma 3.

Since we define

when , it is expressed as

where the following always holds: and (i.e., dB) if is not available, irrespective of the power allocation scheme as stated in Lemma 2. The performance loss over the system with is

as stated in Lemma 3. □

References

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Xiao, M.; Ding, Z.; Lei, X.; Karagiannidis, G.K.; Fan, P. 6G Wireless Networks: Vision, Requirements, Architecture, and Key Technologies. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2019, 14, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promwongsa, N.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Naboulsi, D.; Kianpisheh, S.; Belqasmi, F.; Glitho, R.; Crespi, N.; Alfandi, O. A Comprehensive Survey of the Tactile Internet: State-of-the-art and Research Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2021, 23, 472–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, G.; Iacovelli, G.; Boccadoro, P.; Grieco, L.A. Internet of Drones Simulator: Design, Implementation, and Performance Evaluation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 1476–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, E.T.; Potirakis, S.M.; Kanatas, A.G. AI-Inspired Non-Terrestrial Networks for IIoT: Review on Enabling Technologies and Applications. IoT 2020, 1, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abro, G.E.M.; Zulkifli, S.A.B.M.; Masood, R.J.; Asirvadam, V.S.; Laouti, A. Comprehensive Review of UAV Detection, Security, and Communication Advancements to Prevent Threats. Drones 2022, 6, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAHLSTROM. Introduction To Uav Systems, 4th ed.; WILEY: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ng, D.W.K.; Yu, W.; Larsson, E.G.; Al-Dhahir, N.; Schober, R. Massive Access for 5G and Beyond. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 615–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viterbi, A. Very low rate convolution codes for maximum theoretical performance of spread-spectrum multiple-access channels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1990, 8, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenger, P.; Orten, P.; Ottosson, T. Code-spread CDMA using maximum free distance low-rate convolutional codes. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2000, 48, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Poor, H. Iterative (turbo) soft interference cancellation and decoding for coded CDMA. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1999, 47, 1046–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannstrom, F.; Aulin, T.; Rasmussen, L. Iterative detectors for trellis-code multiple-access. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2002, 50, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkarimi, M.; Raza, M.A.; Dobre, O.A. Signature-Based Nonorthogonal Massive Multiple Access for Future Wireless Networks: Uplink Massive Connectivity for Machine-Type Communications. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2018, 13, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, C.; Burnashev, M.V. The interplay between error control coding and iterative signal cancelation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 3020–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hanzo, L. A Unified Treatment of Superposition Coding Aided Communications: Theory and practice. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2011, 13, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Ping, L. Interleave Division Multiple Access for High Overloading Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 10th International Symposium on Turbo Codes & Iterative Information Processing (ISTC), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, N.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; He, D.; Hong, H.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W. User-Load-Compatible Masking Schemes for Raptor-Like Protograph-Based LDPC Codes in Gaussian Multiple Access Channels. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 7652–7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Y.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Kato, N. Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2018, 20, 2714–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Aulin, T.; Sundberg, C.E. Digital Phase Modulation; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M.K. Bandwidth-Efficient Digital Modulation with Application to Deep Space Communications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elmasry, G.F. Tactical Wireless Communications and Networks: Design Concepts and Challenges; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 802.15.4-2020; IEEE Standard for Low-Rate Wireless Networks. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020.

- Bing, L.; Gu, Y.; Aulin, T.; Wang, J. Design of Auto-Configurable Random Access NOMA for URLLC Industrial IoT Networking. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqvist, P. Multiuser Serially Concatenated Continuous Phase Modulation. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Goteborg, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perotti, A.; Benedetto, S.; Remlein, P. Spectrally Efficient Multiuser Continuous-Phase Modulation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Cape Town, South Africa, 23–27 May 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Noels, N.; Moeneclaey, M. Iterative Multiuser Detection of Spectrally Efficient FDMA CPM. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 5254–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, L.; Aulin, T.; Bai, B.; Zhang, H. Design and Performance Analysis of Multiuser CPM With Single User Detection. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2016, 15, 4032–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E. Channel Polarization: A Method for Constructing Capacity-Achieving Codes for Symmetric Binary-Input Memoryless Channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2009, 55, 3051–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqvist, P.; Aulin, T. Orthogonalization by principal components applied to CPM. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2003, 51, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdu, S.; Shamai, S. Spectral efficiency of CDMA with random spreading. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchler, M.; Koetter, R.; Singer, A. Turbo equalization: Principles and new results. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2002, 50, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqvist, P.; Aulin, T. Serially concatenated continuous phase modulation with iterative decoding. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2001, 49, 1901–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, S.; Divsalar, D.; Montorsi, G.; Pollara, F. Serial concatenation of interleaved codes: Performance analysis, design, and iterative decoding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 44, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brink, S. Convergence behavior of iteratively decoded parallel concatenated codes. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2001, 49, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).