Highlights

- What are the main findings?

- Proposed S-HSFL, a game-theoretic enhanced secure hybrid split-federated learning framework for 6G UAV networks, achieving over 99% defense success rate against model tampering and maintaining 97% accuracy even with 30% adversarial UAVs.

- Developed the MAB-GT device selection strategy, which mitigates non-IID data impacts and reduces free-riding behavior while controlling communication overhead increase to 10–30%.

- What are the implications of the main findings?

- Addresses critical gaps in 6G UAV networks and provides the first solution resisting collusion attacks among malicious UAVs.

Abstract

Hybrid Split Federated Learning (HSFL for short) in emerging 6G-enabled UAV networks faces persistent challenges in data protection, device trust management, and long-term participation incentives. To address these issues, this study introduces S-HSFL, a security-enhanced framework that embeds verifiable federated learning mechanisms into HSFL and incorporates digital-signature-based authentication throughout the device selection process. This design effectively prevents model tampering and forgery attacks, achieving a defense success rate above 99%. To further strengthen collaborative training, we develop a MAB-GT device selection strategy that integrates multi-armed bandit exploration with multi-stage game-theoretic decision models, spanning non-cooperative, coalition, and repeated games, to encourage high-quality UAV nodes to provide reliable data and sustained computation. Experiments on the Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) dataset under both Independent and Identically Distributed (IID) and non-IID conditions demonstrate that S-HSFL maintains approximately 97% accuracy even in the presence of 30% adversarial UAVs. The MAB-GT strategy significantly improves convergence behavior and final model performance, while incurring only a 10–30% increase in communication overhead. The proposed S-HSFL framework establishes a secure, trustworthy, and efficient foundation for distributed intelligence in next-generation 6G UAV networks.

1. Introduction

The vision of sixth-generation mobile communication systems emphasizes highly intelligent, seamlessly connected space–air–ground integrated networks [1]. As pivotal airborne nodes, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) play an essential role in large-scale sensing, emergency communications, precision agriculture, and smart-city monitoring, benefiting from flexible deployment and reliable line-of-sight links. These UAV platforms continuously generate and process substantial volumes of edge data, creating a pressing demand for distributed learning frameworks capable of supporting real-time decision-making, situational awareness, and network optimization. Centralized learning is increasingly unsuitable for such environments due to privacy exposure risks, bandwidth limitations, and pronounced heterogeneity in UAV computing resources. Federated Learning therefore has received considerable attention in UAV-assisted wireless networks for its inherent privacy-preserving characteristics; however, standard FL remains limited when tasks are computation-intensive or latency-critical [2].

Recent studies have further validated the potential of split federated learning in UAV networks for low-altitude economy services. Specifically, the reference [3] proposes a split federated learning scheme for energy-efficient mobile traffic prediction over UAVs, demonstrating that split learning can effectively reduce the computational burden on UAVs while maintaining prediction accuracy, which reinforces the practical motivation for hybrid split learning in dynamic aerial environments. The reference [4] explores the deployment of large AI models in low-altitude economy applications, highlighting key challenges such as resource mismatch between LAIMs and UAV platforms, and the need for scalable split-learning pipelines with trust and verification support—an objective that S-HSFL directly addresses by integrating verifiable mechanisms and incentive-aware device selection. These works contextualize the development of secure and efficient distributed learning frameworks for UAV networks, underscoring the timeliness and practical value of our proposed S-HSFL.

Hybrid Split Federated Learning has emerged as a promising evolution of FL. By combining split learning for forward propagation on UAVs with federated aggregation at edge servers, HSFL reduces computational load on airborne devices and adapts well to resource-constrained UAV networks [5]. Despite these advantages, existing HSFL solutions still face several obstacles in progressing toward dependable deployment in 6G UAV systems.

- Security and model integrity vulnerabilities: Existing hybrid split federated learning schemes lack robust verification mechanisms for model uploads, rendering the framework vulnerable to adversarial manipulations such as model tampering and forgery during the transmission and aggregation phases [6].

- Insufficient device trust and incentive mechanisms: Unmanned aerial vehicles act as rational agents with heterogeneous resource commitments. Current device selection strategies are often optimized solely for short-term performance, failing to guarantee sustained collaborative participation. In the absence of effective incentive mechanisms, UAVs may reduce their engagement intensity, withdraw from the collaboration, or engage in free-riding behaviors, which ultimately leads to unstable and inefficient training processes [7].

- Accuracy and robustness constraints: Under scenarios involving malicious interference, intermittent UAV connectivity, or highly non-independent and identically distributed data distributions, HSFL still struggles to maintain fast convergence speed, satisfactory model accuracy, and strong robustness against data heterogeneity [8].

To address these issues, this paper presents S-HSFL, a security-enhanced and incentive-aware hybrid split federated learning framework for 6G UAV networks. The proposed system advances HSFL in the following dimensions:

- We integrate verifiable federated learning techniques into the HSFL pipeline and employ digital-signature–based authentication during device selection and model submission [9]. This design provides strong protection against model tampering and forgery, ensuring the authenticity and integrity of contributions from participating UAVs.

- Incentive-optimized device selection: We develop a Multi-Armed Bandit and Game-Theory–driven(MAB-GT) strategy that combines adaptive exploration with multi-stage strategic interactions. This mechanism accounts for both instantaneous performance and long-term cooperative behavior, effectively incentivizing high-quality UAVs to participate consistently [10].

- Comprehensive experiments using the MNIST dataset under IID and Non-IID distributions demonstrate the advantages of S-HSFL in defense robustness, convergence behavior, long-term participation incentives, and communication-efficiency trade-offs.

The S-HSFL framework and its core components, such as the verifiable learning mechanism and MAB-GT strategy, offer a practical foundation for secure, trustworthy, and efficient distributed intelligence in next-generation 6G UAV networks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related background work, including comparisons of distributed learning technologies and the current research status of device selection mechanisms. Section 3 provides an in-depth introduction to the game-theoretic model and algorithm of the MAB-GT device selection strategy. Section 4 details the design and implementation of the proposed S-HSFL framework. Section 5 conducts security analysis. Section 6 presents experimental settings, result analysis, and key findings. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Comparison of Distributed Learning Paradigms: From FL to HSFL to S-HSFL

Federated Learning enables distributed model training while retaining data on local devices, thus offering intrinsic privacy protection [11]. Classical approaches such as FedAvg have been widely applied in various domains [7]. Nonetheless, conventional FL depends on end devices to perform full forward and backward propagation, which places considerable computational pressure on resource-limited platforms such as UAVs.

Hybrid Split Federated Learning has been introduced to mitigate these limitations by combining Split Learning with FL. In HSFL, UAVs execute only the initial model layers and transmit intermediate activations to edge servers for subsequent computation and aggregation [12]. This design reduces onboard processing and enhances communication efficiency, making it well suited to heterogeneous and dynamically changing UAV environments. However, existing HSFL schemes still face two critical challenges in practical deployment: the lack of robust verification and source authentication mechanisms, leaving the system vulnerable to model tampering and forgery; and the absence of incentive-aware device selection, which limits long-term participation stability and undermines overall learning robustness.

To address these issues, the proposed S-HSFL framework integrates verifiable federated learning and digital-signature-based authentication into the HSFL pipeline, strengthening model integrity and device trustworthiness. Additionally, the framework employs a game-theoretic, multi-armed-bandit device selection strategy to balance immediate performance with sustained participation incentives, thereby supporting a more secure and stable collaborative learning process in 6G UAV networks.

2.2. Verifiable Federated Learning and Model Security Protection

As federated learning continues to be deployed in increasingly diverse applications, ensuring the security and integrity of uploaded models has become a critical concern. Existing approaches, for example, homomorphic encryption, Merkle-tree-based proofs, and blockchain-assisted verification, offer varying degrees of integrity protection. However, these techniques typically introduce substantial computational or storage overhead, making them difficult to deploy on UAV platforms with limited onboard resources. Moreover, many of these methods lack fine-grained device identity authentication, leaving the system exposed to impersonation and model forgery attacks [13].

To address these limitations, this work incorporates verifiable federated learning into the HSFL framework to ensure model legitimacy and integrity. The verifiable mechanism adopted in S-HSFL provides two key advantages. First, it is tailored to the HSFL structure, allowing verification to be embedded directly within the split-training workflow. Second, it operates in concert with the device selection strategy, enabling the system to proactively exclude suspicious or malicious devices from contributing to model updates.

2.3. MultiArmed Bandit and Evolution of Device Selection Mechanisms

Device selection plays a central role in determining both the efficiency and robustness of federated learning systems [14]. In UAV-assisted FL, this process is challenged by heterogeneous computational and communication resources, varying participation willingness, and fluctuations in model performance across devices. Existing studies on device selection can be broadly categorized into three groups.

The first category relies on static performance-based selection, prioritizing devices with strong computation capability or favorable channel conditions. While straightforward, such approaches adapt poorly to dynamic UAV environments and offer limited support for incentivizing sustained participation. The second category adopts multi-armed bandit-based methods, such as MAB-BC-BN2 [5], which utilize probabilistic selection and reward mechanisms driven by historical performance. These methods respond better to environmental variability but emphasize short-term feedback and overlook long-term contribution value or strategic behavioral patterns among devices. A third line of work explores game-theoretic tools, applying concepts such as Shapley value or Nash equilibrium to analyze cooperation and resource allocation. However, these formulations are often treated as auxiliary analyses and are not tightly integrated into the device selection process itself.

To clarify the practical deployment path of integrating game-theoretic tools into device selection, we elaborate a concrete workflow tailored for UAV networks. Each UAV is pre-configured with a PKI certificate during flight-controller initialization, which binds the device’s identity to its cryptographic keys.The ground base station or multi-access edge computing server distributes split-model segments to selected UAVs; UAVs execute local computations and upload intermediate activations back to the server. Challenge-based verification is triggered periodically during the training process. The BS maintains a real-time trust score for each UAV, which is updated after each training round based on the UAV’s contribution quality, signature validity and communication stability.

To address these limitations, this paper introduces the MAB-GT device selection strategy, offering a unified and more comprehensive solution. The strategy models UAV behavior through three game-theoretic frameworks, non-cooperative games, cooperative coalition games, and repeated games, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation for selection decisions.

Each UAV in a non-cooperative game independently chooses local update strategies to minimize its cost, acting as a self-interested player. Cooperative coalition games dynamically group UAVs into coalitions via Shapley-value-based contribution evaluation, where members collaborate to maximize the global model’s performance. Repeated games extend the interaction across training rounds, with UAVs’ past behaviors recorded in trust profiles to incentivize long-term cooperative behavior.

It integrates the exploration–exploitation balance of MAB methods [15], where exploitation favors UAVs with demonstrated high contributions to capitalize on known gains, and exploration engages untested UAVs to uncover potential high-performing devices while also ensuring long term incentive compatibility. Dynamic coalition formation encourages continuous contributions from high-quality devices, here defined as UAV nodes with stable signal to noise ratio reflecting reliable communication with the base station, consistent gradient norms indicating aligned local model updates with the global model direction, valid digital signatures verifying identity authenticity and update integrity, and accuracy improving local model updates that enhance the global model’s performance on the shared test set and effectively suppresses free-riding behavior, which refers to UAVs engaging in non-cooperative actions such as uploading trivial or stale updates like reusing outdated local gradients or submitting low information updates, or benefiting from the global model by downloading and using the aggregated model without performing local computation to avoid resource costs of training. Furthermore, digital signatures are embedded into the selection workflow [16], providing essential identity authenticity and enhancing the overall security of the training process.

Although prior research has made progress in FL security and device incentive mechanisms, challenges remain in balancing security with efficiency, and in designing strategies that promote persistent device engagement. The S-HSFL framework proposed in this work achieves advances through the combined introduction of verifiable learning, game-theoretic modeling and digital signature based authentication.

- The proposed unified MAB-GT structure enhances device selection by improving adaptability and promoting fairness.

- The incorporation of digital signatures into the authentication process helps to mitigate risks of identity forgery and opportunistic participation.

- The proposed verifiable closed-loop training framework effectively enhances robustness, fortifies network security, and boosts the final model performance in UAV-enabled 6G systems.

3. Our Construction

3.1. System Model and Notations

We consider a 6G-enabled UAV-assisted wireless network consisting of one edge server (base station, BS) and a set of UAV nodes . Each UAV holds a local dataset with non-IID data distribution, and communicates with the BS via dynamic wireless channels. Key notations used throughout the problem formulation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Notations.

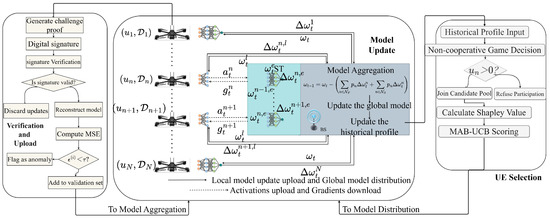

The overall architecture of the proposed S-HSFL system model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture of S-HSFL Framework.

Assumptions of the system model are defined as follows.

- UAVs are resource-constrained (limited computing power and battery capacity) and exhibit high mobility, leading to time-varying channel conditions ( fluctuates dynamically).

- Local datasets are non-IID, i.e., for , and follow heterogeneous distributions.

- Malicious UAVs (up to 30% of ) may launch attacks such as model tampering, forgery, or free-riding (uploading invalid updates without local training).

- UAVs act as rational agents, seeking to maximize their own utility (trade-off between participation benefits and energy costs).

3.2. The S-HSFL Scheme

The S-HSFL Scheme integrates game-theoretic principles with Multi-Armed Bandit learning to address the complexity of device selection in federated learning through distributed decision-making and adaptive incentive mechanisms. The primary goal is to reconcile individual device utility with overall system efficiency while accounting for channel variability, energy constraints, and heterogeneous model contributions [17]. The pseudocode of the proposed MAB-GT algorithm is provided in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 MAB-GT for user equipment Selection |

| Input: K, β, λl, λc, α, βg, γshapley, δhistorical Output: Kt with game-theoretic and security enhancements

|

To address the query on real-world criteria for device clustering and the value function in Shapley value computation, we provide detailed clarifications below, noting that energy consumption is not the sole criterion but part of a multi-dimensional practical framework. Device clustering aims to group UAVs with coherent performance and task relevance to ensure efficient coalition cooperation, implemented via K-means algorithm with four key real-world similarity metrics: communication stability quantified by the variance of SNR () over the most recent 5 training rounds, gradient alignment measured by the cosine similarity between the local update and the global gradient direction, energy status evaluated by the remaining battery percentage of each UAV to avoid clustering UAVs with extremely low energy, and task relevance which for UAV application scenarios is defined as the overlap ratio of sensing regions. The Shapley value φn quantifies each UAV’s marginal contribution to the coalition’s overall performance, with a multi-objective value function v(C) designed for real-world UAV federated learning:

where ΔAcc(C) is the global model’s accuracy improvement on the shared test set (e.g., object detection accuracy gain for UAV surveillance tasks) after integrating updates from coalition C, is the average communication loss of coalition C calculated as the weighted sum of packet drop rate (30% weight) and transmission latency (70% weight), is the average energy consumption of coalition C reflecting resource cost, and the weight coefficients are set as ωacc = 0.5, ωcomm = 0.3, ωenergy = 0.2 (balance resource cost), these weights are adjustable based on specific scenarios. The Shapley value is then computed as follows.

where v(C) − v(C{n}) represents the marginal contribution of UAV n to coalition C, and the combinatorial term accounts for the fair average over all possible coalition subsets.

3.3. Non-Cooperative Game Model Design

The non-cooperative game layer forms the theoretical basis for individual device decision-making. In the federated learning framework, each device acts as a rational agent, seeking to maximize utility during training participation. We propose a distributed game-theoretic mechanism that enables autonomous decision-making by devices.

3.3.1. Utility Function Design

The utility function unifies technical indicators such as SNR, learning value in terms of model updates, and economic costs reflected by energy consumption into quantifiable benefit values, guiding devices to actively join training when participation benefits > costs.

The utility function for each device un is defined as:

where SNRn (Signal-to-Noise Ratio) represents channel quality; represents the device’s contribution intensity to the global model, indicating the L2 norm of local model updates—the larger the norm, the more significant the contribution; Cn = α · Energyn represents participation cost, primarily considering energy consumption factors. β ∈ [0, 1] is a system-tunable parameter used to balance the weights of channel conditions and model contributions, where β → 1 indicates the system prefers high-channel-quality devices, and β → 0 indicates that the system prefers high-contribution devices.

3.3.2. Nash Equilibrium Implementation

Devices reach a stable equilibrium state through distributed decision processes with no unilateral deviation incentive [18]:

- (1)

- Before each training round, devices receive the global model ωt and current channel states {SNRn};

- (2)

- Device un independently calculates the expected utility Un for participating in training;

- (3)

- Participates when , otherwise refuses;

- (4)

- The base station collects participation decisions to form candidate device pool Kcandidate.

Autonomous device decision-making significantly reduces communication overhead, avoids central node computational bottlenecks, and naturally filters low-utility devices.

The candidate device pool Kcandidate serves as prior knowledge input to the MAB selector, achieving multi-faceted collaborative optimization. Using Kcandidate, the MAB selector only needs to explore within this candidate pool [19], significantly reducing computational complexity from the original device-set-based O(N) to O(Kcandidate), substantially shrinking the exploration space and reducing computational burden. This collaborative mechanism also supports dynamic adjustment of the β parameter: the system increases β values when channel conditions dominate and decreases β values when model contributions dominate. Ultimately, this synergy optimizes resource allocation, effectively guiding devices to make autonomous trade-off decisions between their energy budget constraints and expected task execution rewards. By focusing on the critical information provided by Kcandidate, this mechanism significantly enhances the operational efficiency and strategic adaptability of the MAB selector in communication environments.

3.4. Cooperative Game and Coalition Formation

To address resource heterogeneity among devices, we introduce a dynamic coalition mechanism as follows.

3.4.1. Coalition Construction Strategy

- (1)

- Initialization: Perform K-means clustering based on device feature vectors [SNRn, ‖Δωn‖2] to form initial coalitions.

- (2)

- Update: Re-evaluate coalition structure every T rounds: After every T rounds of updates, merge high-contribution devices with Shapley value Top-K to form super-coalitions and share channel resources; conversely, when intra-coalition contribution differences measured by Shapley value variance exceed the threshold, i.e., Var(φn) > θsplit, split coalitions and reorganize by contribution tiers [20].

- (3)

- Scaling Control: Limit coalition members to the [minsize, maxsize] interval to prevent overfitting or communication bottlenecks.

3.4.2. Contribution Quantification

The marginal contribution of device un in coalition S:

where the coalition value function is:

Two key assumptions underpin the validity of the Shapley value derivation in Equation (4). First, coalition subset independence, meaning the value v(S) (defined in Equation (5)) depends only on the devices in S. Second, coalition value additivity, as the value function v(S) is defined as the sum of individual device values.

Monte Carlo approximation is used for efficient computation, significantly reducing computational complexity to O(M|K|), where M is the number of samples. Shapley values ensure that contribution allocation satisfies efficiency, symmetry, and additivity axioms, avoiding “free-riding” behavior.

3.4.3. Deep Integration with MAB

Shapley values act as dynamic weighting factors within the UCB-based selection process, modulating the balance between historical rewards and exploration uncertainty.

where γ denotes the Shapley-value weighting factor, which embeds coalition-level contributions into the exploration strategy. Coalition structures directly influence exploration behavior: devices within the same coalition may share channel state information to reduce exploration overhead, whereas devices in different coalitions apply distinct exploration coefficients. The reward allocation mechanism is further aligned with coalition contributions through Rewardn ∝ φn, thereby forming a closed-loop feedback system that reinforces contribution aware exploration and incentivization [21].

3.5. Repeated Games and Long-Term Strategies

We design a history-driven, long-term incentive mechanism tailored to the multi-round nature of federated learning, leveraging accumulated behavioral records to assess device reliability and overcome the inherent myopia of single-round interactions.

3.5.1. Multi-Dimensional Historical Profiles

Dynamic profiles are maintained for each device, encompassing historical SNR fluctuation patterns, model update contributions, participation decisions, and coalition cooperation stability. SNR patterns reflect channel stability, distinguishing between mobile and fixed devices. Contribution trends track devices with declining input, potentially indicating issues like low battery or withdrawal. Participation records capture coalition-switching frequency, while cooperation stability evaluates willingness to remain engaged in collaborative efforts [22].

3.5.2. Reputation Mechanism Design

To maintain system security and incentive mechanisms, we design a reputation mechanism encompassing both punishment and reward aspects.

Punishment Strategies: Refusal to participate triggers device trust value decay:

reducing subsequent selection probability; meanwhile, when accumulated abnormal behavior, e.g., gradient forgery reaches a preset threshold, it triggers coalition exclusion of the device, depriving it of collaborative qualifications within the coalition.

Reward Strategies: Devices continuously participating in training receive trust value improvements with trust gradually converging to the maximum value of 1, specifically expressed as:

High contribution devices with contribution measured by Shapley value φn are assigned higher selection priority, with selection probability Pr(un) ∝ pnφn. To promote collaborative efficiency, devices that sustain stable coalition memberships over time are rewarded with additional computational resources.

3.5.3. Historical Contribution Integration

Time-decayed historical contribution terms are introduced in UCB scoring

where δ is the historical term coefficient and Hn is the weighted historical contribution.

ω controls the weight between historical SNR and contributions.

3.6. A PKI-Based Full-Lifecycle Certificate Management

To safeguard communication identity and data integrity, this work establishes a PKI-based full-lifecycle certificate management scheme together with a hierarchical key architecture. The full lifecycle mechanism covers the entire key usage process, incorporating counter-triggered automatic key rotation, real-time Certificate Revocation List updates for prompt removal of invalid or suspicious certificates, and strict signature-verification procedures to ensure message authenticity and reliable identity binding.

The hierarchical key system provides differentiated key configurations across layers: the device layer employs short-lived operational keys to support frequent and transient security operations. The coalition layer assigns shared verification keys to coalition members for efficient intra group message authentication and the system layer governed by the root Certificate Authority maintains the root trust anchor for issuing and managing top-level credentials [23].

3.6.1. Behavioral Security Profiles

Three-dimensional behavioral feature vectors are constructed:

Anomaly detection based on Mahalanobis distance:

When DM > θanomaly, where anomaly θanomaly is determined and μ is the normal device mean vector.

3.6.2. Trust Score Integration

Dynamic trust calculation: The logarithmic term penalizes low-frequency high-failure-rate devices.

UCB security correction: Devices with revoked certificates experience exponential score decay.

To explicitly clarify the core components of the proposed MAB-GT device selection model and their design rationales tailored for UAV scenarios, the state space, action space, reward function, and update rules are formally defined as follows:

- State space consists of the signal-to-noise ratio of UAV node n at round t, the norm of gradient update , trust score, coalition index, and the device’s historical contribution trajectory (see Equation (7)). These state dimensions comprehensively characterize UAV mobility, data quality, and operational reliability.

- Action space is defined as the decision-making process of selecting K UAVs from the candidate pool to participate in the current training round, based on the Upper Confidence Bound score in Equation (15).

- Reward function is composed of weighted model improvement, channel quality, and coalition contribution, which organically unifies the short-term rewards of the multi-armed bandit algorithm with the long-term strategic contributions under the game-theoretic framework.

- Update rules include the following core mechanisms: dynamic adjustment of UCB score with trust correction (Equation (15)), Shapley-value-driven reinforcement update of contribution, time-decayed calculation of historical contribution, and coalition restructuring strategy executed every T rounds.

3.7. UAV-Specific Characteristics Adaptation

UAV-assisted wireless networks exhibit distinct dynamic properties, including high mobility, altitude-dependent channel conditions, and strict energy constraints. These characteristics are integrated into the S-HSFL framework to ensure practical applicability in real-world UAV scenarios in the following.

3.7.1. Mobility-Aware Channel Modeling

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNRn) is adopted as a core metric in both the utility function and reward mechanism, capturing the time-varying nature of UAV communication links. As UAVs adjust their flight altitude or change positions, the channel switches dynamically between Line-of-Sight and Non-Line-of-Sight conditions, leading to fluctuations in SNRn. This dynamic SNRn directly modulates the device’s utility value, determining its eligibility for the candidate pool Kcandidate. Additionally, SNRn serves as a key input to the Upper Confidence Bound exploration weight calculation, ensuring the MAB-GT strategy adapts to mobility-induced channel variations.

3.7.2. Energy-Constrained Participation

UAVs rely on onboard batteries with limited capacity, making energy efficiency a critical concern. The cost term Cn = α · Energyn in the utility function quantifies the energy consumption of each UAV during training. As the battery level declines, Energyn increases, reducing the utility Un of the UAV. When Un < 0, the UAV autonomously opts out of training, aligning the framework with the energy constraints of UAV platforms.

4. Verifiable Hybrid Split Federated Learning Algorithm

4.1. Hybrid Split Federated Learning

HSFL is a hybrid framework combining FL and SL, designed to balance communication overhead and user equipment computational capabilities [5]. In HSFL, the server divides the global model into two parts: User Equipment sub-model and Server sub-model. Meanwhile, training modes are dynamically allocated based on user device computational capabilities: for users with strong computational capabilities, the traditional federated learning mode is adopted, where users download the complete model and train locally; for users with weaker computational capabilities, the split learning mode is employed, where users hold only the UE sub-model and are responsible for its training.

Specifically, let the global model be M, divided into Mue (user-side model) and Mserver (server-side model), satisfying:

where x is the input data.

In round t training, the server first randomly selects a subset of users St from all users, then divides St into two subsets based on the preset split ratio ρ:

- Federated learning user subset:

- Split learning user subset:

For each user i, if , they download the complete global model M (containing parameters of both Mue and Mserver) locally, perform E rounds of training on local dataset Di, obtain updated local model M(i), and upload the updated complete model parameters to the server. If , they only download Mue parameters. During training, users are responsible for forward propagation to the split point and send intermediate features to the server; the server completes the remaining forward propagation, calculates loss and backpropagates to the split point, returning gradients to users; users continue to complete local model backpropagation and parameter updates. After training completion, users only upload updated Mue parameters.

4.2. Verifiable Mechanism Design

In distributed environments, malicious users or unreliable devices may upload contaminated model parameters, leading to model performance degradation or destruction. To ensure the validity of user-uploaded model parameters, we design a challenge-based verifiable mechanism. Algorithm 2 presents the pseudocode for the entire HSVFL algorithm.

| Algorithm 2 HSVFL Algorithm |

Input: T, η, K, Dchal, global model ωt, UE-side model , BS-side model

|

4.2.1. Data Preparation

The server maintains a small challenge dataset Dchal, constructed by randomly selecting m samples from the test set with their labels pre-computed. Following global model initialization, the server generates initial prediction outputs for these challenge samples.

where M0 is the initialized global model.

4.2.2. Proof Generation

After completing local training, user i evaluates its local model on the challenge dataset Dchal to generate the prediction output , which serves as the verification proof [24]:

4.2.3. Verification Process

Upon receiving the uploaded model parameters and the proof from user i, the server performs the following verification procedures:

- (1)

- Model Reconstruction: For federated learning users, reconstruct model as M(i); for split learning users, reconstruct model as , where (user upload), (server part in current round global model).Prediction Output Computation:The server applies the reconstructed model to the challenge dataset Dchal to obtain the predicted outputs:

- (2)

- Mean Squared Error (MSE, Mean Squared Error) Calculation:where is the prediction vector for the j-th challenge sample provided by user i, and is the corresponding prediction vector computed by the server using the reconstructed model. If ϵ(i) < τ (a predefined threshold, e.g., 10−4), the user’s upload is accepted; otherwise, it is rejected.

4.2.4. Dynamic Challenge Updates

To prevent malicious users from overfitting or adapting to a fixed challenge set, the server refreshes the challenge dataset Dchal every C rounds by re-sampling mm instances from the test set. The server then updates the stored challenge samples and their corresponding prediction outputs under the current global model.

4.3. Aggregation Strategy

After completing the verification process, the server obtains two categories of validated parameter updates:

- (1)

- Valid model parameter updates by federated learning participants .

- (2)

- Valid user-side model parameter sets from split learning users: .

Subsequently, the server employs a dual-track aggregation strategy, separating the parameters into the UE-side parameters and the server-side parameters for independent updates [9].

For the UE-side parameters, the server aggregates the corresponding parameters contributed by federated learning users extracted from their full model uploads together with the UE-side parameters provided by split learning users.

where represents the verified UE parameter set from federated learning users, and Vsplit represents the verified UE parameter set from split learning users.

For the server-side parameters, aggregation is performed exclusively using the verified server-side updates contributed by federated learning users.

where is the verified server parameter set from federated learning users. The derivation of this server-side parameter aggregation equation relies on two core assumptions: parameter homogeneity meaning all conform to the same parameter space and update granularity; and verification validity, where the parameter set , has passed the digital signature based authentication scheme.

5. Formal SecurityAnalysis

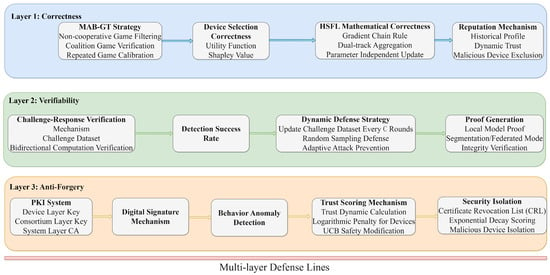

This section presents the security analysis of the proposed S-HSFL framework and compares it with existing approaches. The MAB-GT strategy integrates non-cooperative game theory to model competitive interactions among devices for preliminary screening, applies coalition-formation game mechanisms to promote device collaboration and form more stable participation groups, and incorporates repeated-game dynamics to account for long-term device incentives and ensure a sustainable motivation mechanism. Moreover, the adoption of verifiable federated learning and digital signatures further strengthens the system’s security. Figure 2 illustrates the security model of the S-HSFL framework.

Figure 2.

The security model diagram of the S-HSFL framework.

5.1. Correctness

The correctness guarantee of the S-HSFL framework is reflected in the authenticity of the training process and the reliability of its resulting model updates. Within the MAB-GT strategy, correctness is ensured through a multilayer game-theoretic mechanism that jointly validates device selection and training consistency.

Theorem 1

(Correctness Guarantee of Device Selection). Under the MAB-GT strategy, the system selects genuinely high-quality devices for participation with probability at least 1 − δ, where δ denotes the system’s fault-tolerance threshold [18].

The correctness result follows from the synergistic operation of the three layer game framework.

- Non-cooperative game screening. Each device engages in autonomous decision-making through its utility function Un, joining the training process only when its expected payoff satisfies . This rule effectively filters out low-utility or unreliable devices, thereby preventing unnecessary consumption of computational resources.

- Coalition-formation verification. In the subsequent cooperative-game phase, device contributions are quantified using the Shapley value φn. This metric strictly satisfies the axioms of efficiency, symmetry, and additivity from cooperative game theory, ensuring mathematically sound and interpretable contribution evaluation.

- Repeated-game correction. A repeated game mechanism maintains a historical performance profile Profilen for each device [20]. Together with a dynamic trust metric Trustn updated in real time according to device behavior, the system can reliably identify and exclude devices demonstrating inconsistent or adversarial patterns over time.

Beyond device selection, correctness in the hybrid split-learning component is guaranteed through formal verification of both the forward-propagation and backpropagation procedures. In particular, the gradient computation across the split boundary adheres strictly to the chain rule, ensuring that partial gradients exchanged between the UE-side and server-side components remain consistent with end-to-end training semantics.

The above equation ensures the mathematical soundness of the parameter updates. Moreover, the dual-track aggregation strategy performs independent updates for the UE-side and server-side parameters, preventing biases that could arise from combining heterogeneous parameter types and thereby maintaining the overall rigor of the training process.

5.2. Verifiability

Verifiability forms a key security safeguard in the S-HSFL framework against malicious interference. The authenticity of the parameters uploaded by devices is ensured through a challenge-based verification mechanism that enables effective and reliable validation.

Theorem 2

(Completeness of Verification Mechanism). For any forged parameter uploaded by a malicious device i, the verification mechanism can detect the forgery with a probability of at least 1 − ϵ, where ϵ is the upper bound of the false detection rate [24].

Our verification mechanism is designed around a challenge dataset Dchal maintained by the server, which contains m samples randomly selected from the test set. The verification process employs a dual-calculation mode: the client side must compute the prediction output on the challenge dataset using its locally trained model as verification proof; the server side, using the user-uploaded parameters to reconstruct the model, independently computes the prediction result for the same challenge data. The two prediction results are compared using the MSE ϵ(i). Parameters are accepted if the error is below a preset threshold τ; otherwise, they are rejected.

Security analysis of this verification mechanism indicates that when a malicious device attempts to submit forged parameters deviating from the genuine training result by Δ, a detection success rate approaching 100% is achieved if . To prevent malicious devices from learning the fixed challenge data and launching targeted attacks, we implement a dynamic defense strategy that automatically updates the challenge dataset Dchal every C training rounds, ensuring attackers cannot predict and adapt to the verification pattern. The computational complexity of the entire verification process is O(m · d), where d is the model output dimension. By setting the number of challenge samples m appropriately, we can effectively control computational overhead while maintaining security.

5.3. Unforgeability

Unforgeability protects both data integrity and device identity authenticity through a dual-layer mechanism that combines cryptographic guarantees with behavioral assessment.

Theorem 3

(Unforgeability). Under the Computational Diffie–Hellman assumption, the probability that an adversary can forge a valid digital signature in polynomial time is negligible.

To provide strong resistance against forgery, a hierarchical PKI architecture is adopted [23]. The system includes three layers: at the device layer, short-lived operational keys are employed to support frequent key rotation and improve forward secrecy; at the coalition layer, shared verification keys are issued based on intra-coalition trust relations, thereby reducing verification overhead among collaborating devices; at the system layer, a root CA maintains global trust consistency and serves as the ultimate trust anchor. In the signature verification process, each device signs both the message and the associated model parameters using its private key SKi.

The server verifies via the public key

to confirm the message integrity and source authenticity. Simultaneously, certificate chain verification ensures the correct binding relationship between the public key PKi and the device identity IDi.

To further enhance system security, an anomaly detection mechanism based on behavioral analysis is incorporated. For each device, the system constructs a three-dimensional behavioral feature vector and anomalous patterns are identified by computing the Mahalanobis distance DM. When the deviation exceeds the threshold, i.e., DM > θanomaly,the system issues an alert and updates the device’s trust score Trustn in real time. The trust evaluation not only reflects the device’s verification success rate but also introduces a logarithmic penalty for devices exhibiting infrequent yet high-failure behavior, thereby limiting the ability of malicious nodes to evade detection through sporadic attacks.

Furthermore, in Equation (13), a security factor is incorporated into the UCB scoring rule to construct a security-aware selection strategy. This design ensures that devices with revoked certificates or low trust values face an exponentially reduced probability of being selected, effectively isolating potential threats during the training process. The overall anti-forgery design provides layered protection: key rotation preserves forward secrecy by preventing exposure of past communications; timestamp and sequence-number checks thwart replay attempts; end-to-end encryption combined with certificate validation ensures peer authenticity and defends against man-in-the-middle attacks. Even under an adversarial setting where up to α = 0.3 of devices behave maliciously, the system maintains stable and reliable security performance.

5.4. Security Comparison

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the security of different schemes, including FL, Aggregation-Verifiable Federated Learning [25], Efficient Verifiable and Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Scheme [26], HSFL, S-HSFL. As reflected in the comparison, our S-HSFL exhibits clear strengths and notable innovations in its overall security design.

Table 2.

Comparison of FL Schemes.

As shown in Table 2, all compared schemes provide basic privacy protection due to the distributed nature of federated learning, which keeps raw data on local devices. However, their privacy-preserving mechanisms differ considerably. Traditional FL relies primarily on the implicit protection brought by parameter aggregation; VeriFL enhances privacy through zero-knowledge proofs; EPPS employs differential privacy in combination with homomorphic encryption; and HSFL benefits from its split-learning architecture. Building on HSFL, S-HSFL further incorporates a verifiability mechanism, achieving a balanced design that strengthens both privacy and validation reliability.

Regarding client-side availability, most schemes support offline computation and local processing. Traditional FL requires persistent online participation, which is impractical in UAV networks with intermittent connectivity. In contrast, VeriFL enables offline training and proof generation using pre-distributed challenge data; EPPS integrates an offline privacy-preserving computation module; and HSFL naturally supports asynchronous processing through its split structure. S-HSFL offers the highest flexibility: high-capability UAVs can complete training and verification entirely offline, while low-capability devices reduce real-time communication reliance through intermediate-feature caching and prediction.

A key differentiating factor lies in aggregation verifiability. Only VeriFL and S-HSFL can validate the correctness and integrity of aggregation results, ensuring that the global model is produced from legitimate, verifiable contributions. FL, EPPS, and HSFL lack such capabilities, leaving them vulnerable to model tampering and parameter manipulation.

The capacity to resist collusion attacks marks the most critical distinction. FL, VeriFL, EPPS, and HSFL do not include dedicated defenses against coordinated malicious behavior. Colluding clients can synchronize attack strategies and inject correlated malicious updates, significantly degrading the global model. S-HSFL uniquely mitigates such threats by combining a game-theoretic MAB-GT device selection strategy with digital-signature-based authenticity checks, enabling the system to identify and suppress coordinated adversarial behavior.

6. Performance Analysis

In this section, we present the learning performance of our proposed S-HSFL framework, comparing it with the original HSFL algorithm by simulating a learning task for image recognition within a wireless UAV network using the classic MNIST dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset (accessed on 22 December 2025)). We evaluate the performance of the MAB-GT strategy for selecting UEs to participate in model training under both IID and non-IID data distributions within the S-HSFL framework. Additionally, security tests for verifiable federated learning and digital signatures were conducted.

6.1. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted on a laptop equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU, where the programming code for both the BS and the UEs was executed. Two deep neural network models, Net and AlexNet, were trained on the MNIST dataset, and their architectures are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Network architectures.

For all experiments involving the S-HSFL framework and the HSFL algorithm, the DNN models were partitioned at the second layer, immediately after the first conv1 layer. The number of UAVs was fixed at 100, and the total number of training rounds was set to 100. To evaluate the learning performance of the proposed HSFL framework, we simulated a wireless UAV network consisting of a base station positioned at the cell center and multiple UAVs uniformly distributed within the coverage area. The cell radius was 500 m, the BS antenna height was 20 m, and the UAV flight altitude ranged from 20 m to 80 m. The detailed parameters of the UAV network simulation are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

UAV Network Simulation Parameters.

These parameters correspond to the 6G UAV-to-edge server communication channel model in the S-HSFL framework. a and b are environmental parameters (S-curve fitting coefficients) that characterize the LoS/NLoS link probability in the urban deployment scenario of UAVs, derived from the ITU-based channel model (relating to building density and height distribution).LOS/NLOS path loss index are exponents in the path loss model (PL = PL0 + 10nlog10(d/d0)), where n = 2.8 (LoS) and n = 4.0 (NLOS) represent the rate of signal attenuation with distance under line-of-sight and non-line-of-sight propagation conditions, respectively. LOS/NLOS additional loss are fixed attenuation values (beyond free-space path loss) introduced by LoS and NLOS propagation.

6.2. Performance Comparison

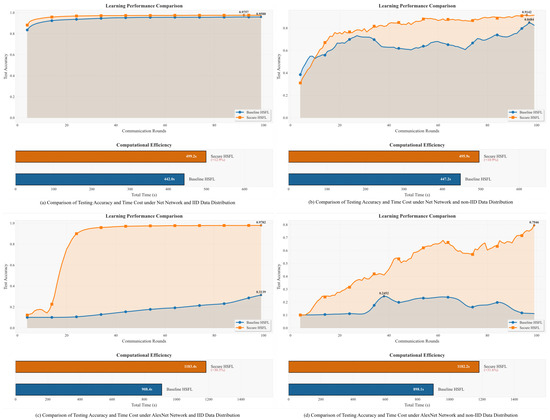

This section compares the learning performance of our proposed S-HSFL framework against the original HSFL in terms of test accuracy and communication overhead. We employed the MAB-GT selection scheme to choose K = 10 UEs from N = 100 UEs for training in each round, setting Ks = Kf = 5 for the HSFL algorithm. IID and non-IID data distributions followed the same settings as in [5]. The local training epochs τ and batch size were set to 5 and 32 respectively. Experimental results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Testing Accuracy and Time Cost.

The accuracy results in the four subfigures consistently demonstrate the performance superiority of Secure HSFL over Baseline HSFL across all experimental settings. Under IID conditions with the Net architecture (Figure 3a), Secure HSFL converges rapidly and stabilizes at 95.88%, whereas the Baseline reaches 95.57% but converges more slowly and exhibits pronounced fluctuations. The impact of data heterogeneity is evident in Figure 3b: Secure HSFL maintains an accuracy of 94.04%, while the Baseline drops significantly to 84.24%, highlighting its vulnerability to non-IID distributions. The performance gap widens further in the AlexNet experiments. Under IID data (Figure 3c), Secure HSFL attains 97.63% accuracy, whereas the Baseline collapses to 31.39%, failing to form an effective model. A similar pattern appears under non-IID conditions (Figure 3d), secure HSFL maintains effective learning at 79.46% accuracy despite strong data heterogeneity, whereas Baseline HSFL fails catastrophically (24.52%), highlighting its inability to handle non-IID data in deeper models. indicating its inability to support reliable learning in heterogeneous environments.

These results show that the Secure HSFL framework achieves stable and high-accuracy performance under diverse network structures and varying degrees of data heterogeneity. This robustness is attributed to the integration of verifiable federated learning protocols and the MAB-GT–based device selection mechanism. The framework remains resilient in complex topologies and in scenarios where participant data distributions differ substantially. The MAB-GT strategy combines the adaptive exploration capability of multi-armed bandit algorithms with multi-stage game-theoretic decision processes, allowing the system to identify and prioritize devices that provide higher-quality data and more dependable computational resources. Its embedded incentive mechanism further supports honest participation and long-term engagement. In non-IID settings, this selection strategy effectively mitigates the adverse effects of data imbalance, thereby preserving both the accuracy and stability of the global model.

Time Overhead Analysis

From a computational efficiency perspective, the security mechanisms and optimization strategies introduced by Secure HSFL do incur additional time overhead. However, the magnitude of this overhead varies across scenarios and remains acceptable. In the Net network IID experiment shown in Figure 3a, Secure HSFL required 499.2 s, representing an increase of 57.2 s or 12.9% compared to Baseline HSFL’s 442.0 s: this panel’s overlapping blue (Baseline) and orange (Secure HSFL) learning curves indicate matching accuracy, while the bar plot confirms minimal overhead (12.9%), reflecting low additional cost for lightweight models under homogeneous data. The Net network non-IID experiment in Figure 3b shows similar efficiency: Secure HSFL took 495.9 s versus Baseline HSFL’s 447.2 s (an increase of 48.7 s or 10.9%), and here the orange curve outperforms the blue curve in accuracy demonstrating robustness to heterogeneous data with negligible extra cost.

However, time overhead increases for the more complex AlexNet network. Under IID conditions in Figure 3c, Secure HSFL required 1103.4 s, which is an increase of 195 s or 21.5% over Baseline HSFL’s 908.4 s: the orange curve maintains stable high accuracy (while the baseline stagnates), justifying the moderate overhead (21.5%) via performance gains. The overhead was most significant under non-IID conditions as seen in Figure 3d, where Secure HSFL took 1182.2 s (an increase of 284.1 s or 31.6% compared to Baseline HSFL’s 898.1 s): critically, the baseline’s flat blue curve indicates near-total convergence failure, while the orange curve achieves and sustains high accuracy—making this peak overhead (31.6%) essential for practical utility in complex, heterogeneous scenarios.

Regarding the observation that Secure HSFL’s performance continues increasing, while Baseline HSFL’s performance decreases (in Figure 3d. This divergence stems from two core advantages of Secure HSFL’s design: First, Secure HSFL integrates the MAB-GT device selection strategy, which dynamically prioritizes reliable, high-contribution devices throughout training. After 70 rounds, Baseline HSFL which uses random device selection accumulates noise from low-quality/malicious local updates, causing its model to overfit to heterogeneous data, hence the performance decline. In contrast, Secure HSFL’s device selection filters out such unreliable updates, enabling continuous learning from high-value local models. Second, Secure HSFL’s secure parameter aggregation via Shapley-value weighted fusion reduces the impact of outlier updates. Baseline HSFL’s uniform aggregation amplifies the negative effects of data heterogeneity over time, while Secure HSFL’s weighted fusion adapts to the distribution shift—supporting sustained performance improvement even in late training rounds.This trend directly validates Secure HSFL’s robustness to data heterogeneity and malicious interference, which is unattainable with Baseline HSFL’s naive device selection and aggregation.

While the MAB-GT device selection strategy enhances model quality and convergence speed, its dynamic evaluation and game-theoretic analysis processes consume additional computational resources. This time investment is valuable, as it provides security guarantees and improves final model performance through superior device selection and parameter aggregation strategies. The resulting gains in robustness and accuracy against malicious attacks and data heterogeneity challenges are unattainable with traditional methods [10]. Therefore, despite the increased time overhead for complex architectures, the substantial improvements in accuracy offered by Secure HSFL, particularly considering the near-total failure of Baseline HSFL in the AlexNet experiments (Figure 3c,d), justify the additional time cost. This demonstrates a favorable balance between security, accuracy, and efficiency across diverse real-world scenarios.

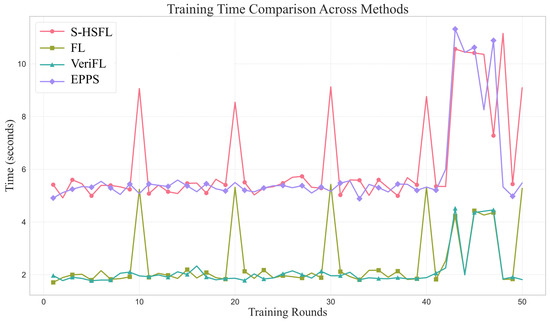

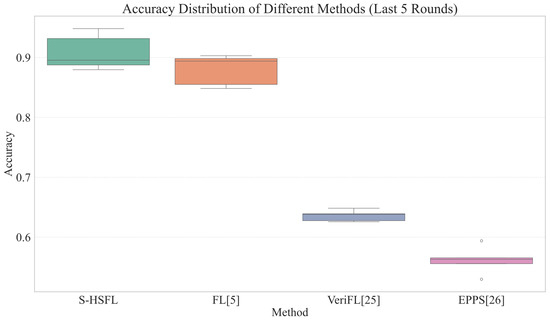

We will compare the four algorithms mentioned above from three aspects: accuracy, time cost, and the distribution box line of the last 5 rounds of accuracy. The experimental results are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Accuracy of Four Algorithms.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Time Cost of Four Algorithms.

Figure 6.

Box Plot of Accuracy Distribution for the Last 5 Rounds [5,25,26].

The accuracy evolution curves in Figure 4 demonstrate that the proposed S-HSFL algorithm exhibits significant performance advantages throughout the entire training process. During the initial training phase within the first 10 rounds, S-HSFL demonstrates rapid convergence characteristics, with accuracy swiftly increasing from approximately 0.2 to above 0.8. This rapid convergence capability is primarily attributed to the effectiveness of the dynamic device selection mechanism and coalition formation strategy within the MAB-GT approach. The mechanism quantifies device contributions through Shapley values and prioritizes high-quality devices for training participation, thereby obtaining high-quality model updates even in the early training stages.

In the mid-to-late training phases, the S-HSFL algorithm consistently maintains high accuracy levels above 0.9, demonstrating excellent stability and robustness. Particularly noteworthy is that during the convergence phase from rounds 30–50, S-HSFL exhibits significantly smaller accuracy fluctuations compared to other baseline algorithms, indicating that the introduction of verifiable mechanisms and digital signature technologies effectively mitigates the negative impact of malicious attacks on model performance. In contrast, traditional federated learning algorithms show pronounced performance oscillations in later stages, with accuracy fluctuating between 0.85–0.95, reflecting the system’s vulnerability when lacking security verification mechanisms.

Although the VeriFL algorithm [25] possesses verification capabilities, its final accuracy only stabilizes around 0.65, markedly lower than S-HSFL’s performance. This difference primarily stems from VeriFL’s lack of game-theoretic enhanced intelligent device selection strategies, failing to fully exploit the collaborative potential among devices. The EPPS [26] algorithm demonstrates the poorest performance, with accuracy persistently hovering in the 0.5–0.6 range, further validating the importance of security mechanisms for federated learning system performance.

The training time comparison results in Figure 5 reveal that the S-HSFL algorithm successfully controls the growth of time overhead while ensuring high accuracy. Throughout most training rounds, S-HSFL maintains single-round training times within a reasonable range of 5–6 s, representing only approximately 150–200% time overhead increase compared to traditional FL algorithms 2 s [5]. This moderate time increase primarily originates from three computational cost aspects: digital signature generation and verification processes, proof computation within the verifiable mechanism, and dynamic coalition management in the MAB-GT strategy.

It is worth emphasizing that the time peaks observed in S-HSFL during specific rounds primarily correspond to periodic operations of coalition reconstruction and Shapley value computation. According to the algorithm design, the system re-evaluates coalition structures every T rounds. While this process generates additional computational overhead, its frequency is controllable and has limited impact on overall training efficiency. Compared to the extremely high time overhead exhibited by the EPPS algorithm in later stages, S-HSFL demonstrates superior scalability and practicality.

More importantly, when comprehensively considering accuracy and time efficiency, the S-HSFL algorithm exhibits excellent performance trade-off characteristics. Although single-round training time increases, the faster convergence speed and higher final accuracy enable S-HSFL to achieve target performance within fewer total training rounds, thereby optimizing time efficiency across the entire training cycle.

The accuracy distribution box plots in Figure 6 clearly illustrate the exceptional stability of the S-HSFL algorithm. S-HSFL’s accuracy distribution is primarily concentrated within the 0.89–0.94 range, with a median close to 0.92 and a small interquartile range, indicating that the algorithm maintains consistent high performance under different experimental conditions. This stability benefits from the synergistic effects of multiple security mechanisms: the verifiable federated learning mechanism ensures the validity of model updates, digital signature technology guarantees communication security, while the game-theoretic enhanced device selection strategy optimizes the quality of participating devices.

In comparison, traditional FL algorithms exhibit wider accuracy distribution ranges from 0.84 to 0.90, reflecting performance instability when facing different network conditions and device heterogeneity [5]. Although the VeriFL algorithm possesses certain verification capabilities, its accuracy distribution concentrates at the relatively low level of 0.62–0.65, with obvious outliers, indicating limited effectiveness of its verification mechanism [25]. The EPPS algorithm demonstrates the most unstable performance, with accuracy distribution spanning from 0.53 to 0.59, further confirming the system’s vulnerability when lacking effective security mechanisms [26].

The hybrid split architecture offloads a large number of computational tasks to edge servers, a feature that makes S-HSFL naturally suitable for deeper and more complex models. The time complexity of the challenge-based verification mechanism is linearly related to the model output dimension, while the computational overhead of the MAB-GT device selection strategy mainly depends on the number of drone nodes and is not significantly related to model depth. Future experiments will introduce drone-specific datasets to further verify the model’s applicability in real flight scenarios [27].

6.3. Other Security Analysis

6.3.1. Security Verification

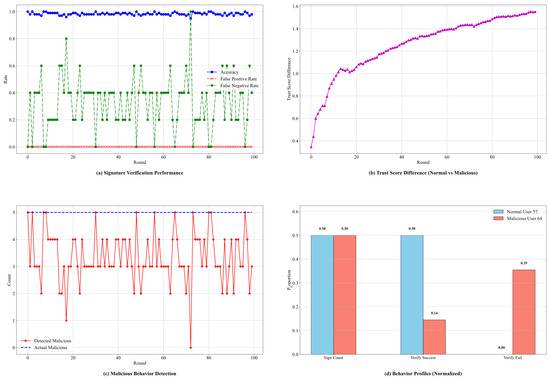

The experiment assessed the system’s capability for message integrity and source authentication through a basic signature verification mechanism. Signatures submitted by all users in each test round underwent strict verification to identify attacks involving message tampering or signature forgery by malicious users. Secondly, the security of the dynamic key rotation mechanism was validated; key pairs were automatically updated when a user’s signature count reached a predefined threshold. At the behavioral analysis level, a multi-dimensional user profiling system was constructed to continuously track metrics such as the number of signature requests, verification success rate, and verification failure rate. The malicious user ratio was set to 5%. Experimental results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Security verification results of digital signatures.

Signature Verification Performance in Figure 7a shows that the digital signature mechanism of the S-HSFL framework exhibits excellent security detection capabilities. Throughout the 100 communication rounds, the system’s accuracy consistently remained near 1.0 with minimal fluctuation, indicating stable and reliable operation of the signature verification mechanism. Crucially, the false positive rate remained near zero throughout the experiment, meaning the system almost never misclassifies legitimate signatures as malicious, preventing the erroneous exclusion of benign participants. While the false negative rate exhibited some fluctuation, reaching 0.6–0.8 in certain rounds, this primarily reflects the system’s sensitivity adjustment when detecting complex attack patterns, rather than a system flaw. Overall, the false negative rate mostly stayed within a reasonable range of 0.2–0.4, indicating effective identification of most malicious behavior [23].

The evolution of trust score differences in Figure 7b clearly demonstrates the S-HSFL framework’s ability to distinguish normal from malicious users. Starting from the initial training phase, the system progressively built awareness of different user behavior patterns. The trust score difference rapidly increased from a low initial level, reaching a significant difference exceeding 1.0 after approximately 20 rounds, and continued growing to a high level of around 1.6 in subsequent training. This distinct divergence in trust scores indicates that the MAB-GT device selection strategy, combined with game-theoretic mechanisms, effectively adjusts trust levels dynamically based on devices’ historical behavior and current performance, thereby incentivizing high-quality devices and penalizing malicious ones.

The Malicious Behavior Detection Results in Figure 7c show a high correlation between the number of detected malicious behaviors and the actual number of malicious behaviors. This consistency demonstrates the system’s excellent capability for identifying malicious activities. Detection results matched the ground truth completely in most communication rounds; even in rounds with minor deviations, the differences were within acceptable limits.

The Normalized Behavioral Feature Comparison in Figure 7d provides quantifiable differences between normal and malicious users across dimensions. In the Signature Count dimension, both normal and malicious users showed the same level of 0.50, indicating no significant difference in participation frequency; malicious users did not evade detection by reducing participation. In the Verification Success dimension, normal users maintained a high success rate of 0.50, while malicious users achieved only 0.14. This stark difference clearly reflects the effectiveness of the digital signature verification mechanism in identifying malicious users who fail to provide valid signatures. The most significant difference is seen in the Verification Fail dimension, where malicious users exhibited a high failure rate of 0.35, compared to 0.00 for normal users. This contrast vividly illustrates the precision of the S-HSFL framework in distinguishing normal from malicious behavior.

6.3.2. Attack Methods Analysis

For attack simulation, malicious users were randomly selected according to preset ratios to perform model replacement attacks: these attackers saved genuine model weights for subsequent analysis while injecting random weights into the server, deliberately simulating destructive weight tampering and model poisoning behaviors. System robustness under varying attack intensities was tested by changing the proportion of malicious users.

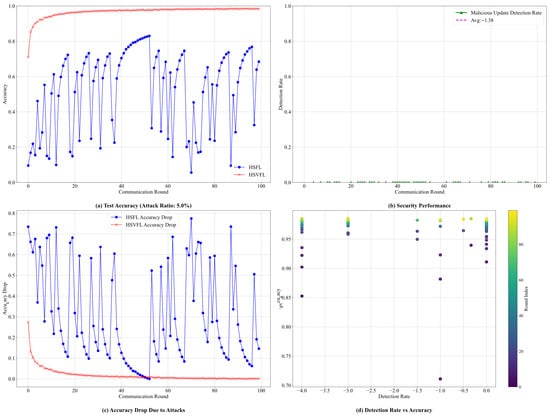

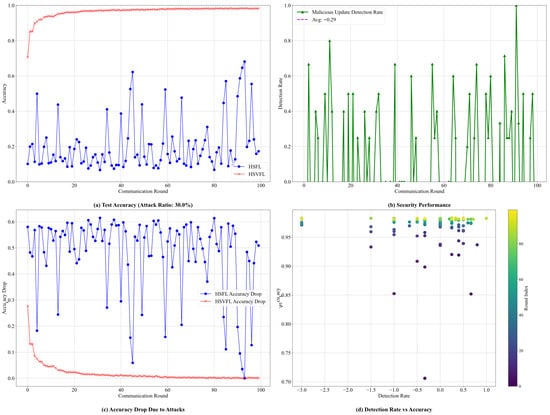

Regarding defense mechanisms, HSVFL employs a three-tiered defense system: clients generate cryptographic proofs-of-work during the training phase, containing specific leading zeros. The server verifies the match between submitted weights and proofs in real-time. Only verified legitimate updates enter the aggregation pool. The protection system continuously quantifies security metrics, calculating precise detection rates per round and tracking their evolution [24]. We specifically examined scenarios with malicious user ratios of 5.0% and 30.0%; results are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively.

Figure 8.

Verifiable Federated Learning Security Verification (Attack Ratio: 5.0%).

Figure 9.

Verifiable Federated Learning Security Verification (Attack Ratio: 30.0%).

In the scenario with 5.0% malicious users, Figure 8a shows that the HSFL system exhibits relatively stable but periodically fluctuating test accuracy, generally oscillating between 0.1 and 0.8. These variations reflect the intermittent influence of malicious updates. In contrast, HSVFL demonstrates markedly higher stability: its accuracy increases rapidly and remains close to 1.0, indicating that the verifiable mechanism is highly effective under low-intensity attacks. This observation is further supported by the security performance results in Figure 8b, where the malicious update detection rate remains near zero, with an average value of −1.38, suggesting that the system reliably identifies and filters out adversarial behavior in mild attack environments.

When the malicious user ratio increases to 30.0% (Figure 9), the elevated attack intensity presents a considerably more challenging setting. Under this high-threat scenario, Figure 9a illustrates that HSFL experiences pronounced and irregular accuracy fluctuations, ranging from 0.0 to 0.7, reflecting the susceptibility of traditional federated learning to large-scale coordinated attacks. In contrast, HSVFL maintains strong resilience: although the initial convergence is slower, its accuracy eventually stabilizes above 0.95. Importantly, Figure 9b shows that the malicious update detection mechanism becomes significantly more active under high-intensity attacks, with the average detection rate increasing from −1.38 to −0.29 and with noticeably higher detection frequency and intensity. This demonstrates the adaptiveness of the verifiable federated learning mechanism, which strengthens its defensive behavior as the threat level rises.

The accuracy degradation analysis in Figure 9c highlights a key conclusion: the accuracy drop of HSVFL rapidly converges to near zero under both attack intensities, whereas the performance degradation of HSFL increases proportionally with the malicious user ratio. This contrast underscores the combined effectiveness of digital signatures and verifiable mechanisms in delivering consistent security guarantees across varying adversarial conditions. The scatter-plot analysis in Figure 9d further confirms this finding, showing a clear and favorable relationship between detection rate and accuracy. Together, these results verify the robustness and practical applicability of the S-HSFL framework in complex and dynamic attack environments.

6.3.3. Robustness on Complex Datasets and Large-Scale Models

While the experiments in this work are conducted on the MNIST dataset with Net and AlexNet architectures to isolate the effects of adversarial behaviors and verification mechanisms, the S-HSFL framework inherently exhibits strong scalability to complex datasets and large-scale models. This robustness stems from three key characteristics:

The complexity of the challenge-based verification mechanism scales linearly with the output dimension O(m · d), where m is the number of challenge samples and d is the model output dimension. This linear scalability ensures that the verification overhead does not explode even for high-dimensional outputs of complex models. The MAB-GT device selection strategy’s computational complexity is primarily determined by the number of UAVs and coalition update frequency, rather than the model size or dataset complexity. The core operations are decoupled from model depth or input data dimension, making the strategy adaptable to large-scale models.The hybrid split structure of S-HSFL is particularly suitable for large models. By offloading the heavy computational burden of deep model layers to edge servers, S-HSFL alleviates the onboard resource constraints of UAVs, enabling the deployment of complex models in resource-limited aerial environments.

As part of future work, we plan to extend our experiments to more complex datasets (e.g., CIFAR-10, Tiny-ImageNet) and large-scale split models (e.g., ResNet-50, YOLOv8-tiny) to validate the framework’s practical applicability in real-world UAV tasks such as aerial object detection and scene classification.

6.4. Application Case

In the security monitoring project of a core business district in a first-tier city, a distributed monitoring network composed of multi-rotor UAVs has been deployed. It is required to realize real-time crowd density monitoring, abnormal behavior recognition (such as fighting and climbing), and suspicious object detection. In this scenario, UAVs need to collaboratively train models in a complex electromagnetic environment, and the data exhibits significant non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) characteristics, there are considerable differences in the types of data collected by UAVs in different areas (for example, data collected at shopping mall entrances is mainly about crowd flow, while that in green belts is dominated by static scenes). At the same time, there are problems such as unstable communication links, and abnormal data may be generated by some UAVs due to battery aging or malicious hijacking.

After the project operated for a period of time, the model achieved stable accuracy in abnormal behavior recognition, showing obvious improvement compared with the traditional HSFL. When a certain proportion of UAVs experienced communication interruptions, the model’s convergence speed only decreased slightly, which was significantly better than the obvious decline of the traditional scheme. The average participation duration of UAVs in the core coalition was greatly extended compared with the initial stage, which effectively solved the problem of high device withdrawal rate.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents a security-enhanced, game-theoretic HSFL framework tailored for 6G UAV networks, addressing key vulnerabilities in distributed intelligence systems. By integrating verifiable learning mechanisms with an incentive-aware device selection strategy, the proposed framework effectively strengthens security, improves aggregation trustworthiness, and enhances learning reliability under heterogeneous and adversarial conditions. These contributions offer both theoretical foundations and practical design insights for constructing secure, trustworthy, efficient, and sustainable air–space–ground integrated intelligent networks. Future work will focus on further reducing system overhead, extending the framework to more complex learning models and large-scale deployment scenarios, exploring collaborative learning across multiple UAV swarms, developing defenses against emerging attack vectors, and improving system robustness in highly dynamic and resource-constrained environments. Specifically, we will explore integrating collective behavior designs beyond nearest neighbor rules [27,28,29] with switching topology-aware collaboration to enhance UAV swarm coordination adaptability, and incorporate novel agent interaction mechanisms alongside distributed collision avoidance strategies to ensure physical safety in dense deployments. Additionally, we will investigate the application of fixed-time consensus algorithms in multi-agent systems to optimize the convergence speed of distributed model aggregation, reducing latency for time-sensitive 6G UAV missions such as real-time security monitoring and emergency response. These extensions aim to bridge the gap between federated learning optimization and multi-robot collective intelligence, promoting the practical deployment of large-scale wireless robotic networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G., X.Z. and J.L.; methodology, Q.G. and X.Z.; software, X.Z.; validation, J.L., Q.G. and X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, G.D.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.G.; supervision, B.T., G.D. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship Plan (KJZD20230923114906013), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62272389), and the Shenzhen Basic Research Program (20210317191843003).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/Echolic/HFSL (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Challita, U.; Saad, W.; Bettstetter, C. Interference management for cellular-connected UAVs: A deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 2125–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenvi Nadkarni, V.B.; Joshi, S.; Lakshmi, L.R. An efficient federated transfer learning approach for multi-UAV systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 National Conference on Communications, New Delhi, India, 6–9 March 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Solat, F.; Lee, J.; Niyato, D. Split Federated Learning-Empowered Energy-Efficient Mobile Traffic Prediction Over UAVs. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 3064–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Du, H.; Xu, J.; Huang, K.; Kim, D.I. Empowering Intelligent Low-altitude Economy with Large AI Model Deployment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.22343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Mahmoodi, T. Wireless distributed learning: A new hybrid split and federated learning approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 2650–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]