Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We introduce a behaviour-aware Unreal Engine 5 pipeline (BEHAVE-UAV) that jointly models animal group dynamics, UAV flight geometry and camera readout to generate detector- and tracker-ready synthetic wildlife imagery.

- High-resolution synthetic pre-training at 1280 px, followed by fine-tuning on only half of the real Rucervus UAV images, recovers nearly all detection performance of a model trained on the fully labelled real dataset.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Behaviour-aware synthetic data can substantially reduce manual annotation effort in UAV wildlife monitoring by enabling sample-efficient training from high-altitude imagery.

- The results provide practical guidance for configuring resolution, synthetic pre-training and fractional real fine-tuning when designing object detectors for long-range ecological UAV applications.

Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly used to monitor wildlife, but training robust detectors still requires large, consistently annotated datasets collected across seasons, habitats and flight altitudes. In practice, such data are scarce and expensive to label, especially when animals occupy only a few pixels in high-altitude imagery. We present a behaviour-aware synthetic data pipeline, implemented in Unreal Engine 5, that combines parameterised animal agents, procedurally varied environments and UAV-accurate camera trajectories to generate large volumes of labelled UAV imagery without manual annotation. Each frame is exported with instance masks, YOLO-format bounding boxes and tracking metadata, enabling both object detection and downstream behavioural analysis. Using this pipeline, we study YOLOv8s trained under six regimes that vary by data source (synthetic versus real) and input resolution, including a fractional fine-tuning sweep on a public deer dataset. High-resolution synthetic pre-training at 1280 px substantially improves small-object detection and, after fine-tuning on only 50% of the real images, recovers nearly all performance achieved with the fully labelled real set. At lower resolution (640 px), synthetic initialisation matches real-only training after fine-tuning, indicating that synthetic data do not harm and can accelerate convergence. These results show that behaviour-aware synthetic data can make UAV wildlife monitoring more sample-efficient while reducing annotation cost.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Advances in deep learning have had a significant impact on ecological monitoring with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), enabling increasingly sophisticated analytical and predictive capabilities [1]. However, the effectiveness of these models depends heavily on the availability of large, high-quality, and consistently annotated datasets. In ecological settings, collecting such datasets is notoriously difficult due to seasonal variability, diverse environmental conditions, animal mobility, and the high labour cost of field acquisition and manual labelling. These constraints hinder the development and deployment of robust UAV-based perception models.

To mitigate data scarcity, synthetic data generation has emerged as a promising strategy. In this work, we use synthetic data to mean data generated algorithmically rather than collected in the field, with the goal of approximating key distributions and structures present in real observations [2]. Such data can supplement or partially replace scarce field imagery. Compared with traditional collection, synthetic pipelines offer controlled diversity (e.g., time of day, weather, sensor effects) and repeatability, which can improve training and fair evaluation across operating regimes [3]. Recent studies in agriculture and ecology have demonstrated tangible benefits: patch-level synthesis improves semantic segmentation in natural agricultural scenes [3]; under controlled conditions, synthetic data can effectively train modern architectures such as Vision Transformers for fine-grained semantic tasks [4,5]; and scalable strategies for object detection combine a small set of target objects with large background pools to boost generalisation [6,7]. Collectively, these results support broader, data-centric training practices in which curated synthetic corpora play a first-class role alongside real imagery [5,8].

Within this broader trend, object detection for UAV imagery typically relies on two main families of architectures: convolutional neural networks (CNNs), including one-stage and two-stage detectors, and more recent transformer-based models that couple attention mechanisms with dense prediction. In this work, we focus on a widely adopted CNN-based one-stage detector, YOLOv8s [9], because it offers a favourable trade-off between accuracy and real-time performance on resource-constrained UAV platforms, and because its open-source implementation and COCO-pretrained weights [10] make it a practical baseline for ecological monitoring.

Despite recent progress, important limitations persist in prior work. Many synthetic-data pipelines focus on static scenes or narrow object taxonomies; they provide limited ecological realism (e.g., simplified behaviours) or they lack explicit modelling of UAV flight geometry and onboard camera effects [11,12,13,14]. As a result, models pre-trained on such data may struggle with dynamic, multi-species scenes and aerial viewpoints typical of field deployments.

To address these limitations, we develop a unified, behaviour-aware pipeline for synthetic dataset generation tailored to UAV-based ecological applications. We construct a parameterized, photorealistic 3D environment comprising forests, clearings, and edge habitats, populated by interacting animal agents that exhibit biologically inspired group behaviours. A virtual drone navigates the scene at user-specified altitudes and viewing angles to capture multi-perspective aerial imagery. For each frame, we export automatic annotations in widely used YOLO formats, including bounding boxes (and optionally segmentation masks) as well as tracking metadata, thereby producing a ready-to-train dataset without manual effort.

1.2. Related Works

1.2.1. Synthetic Data for Computer Vision and Ecology

Synthetic datasets are now widely used in computer vision to train and evaluate models under settings where both scene diversity and experimental control can be explicitly managed [11,12]. By decoupling data generation from costly field campaigns, synthetic pipelines can expose models to combinations of lighting, backgrounds, and object poses that would be difficult to obtain otherwise. For generic detection and segmentation, prior studies show that mixing real and synthetic images can improve robustness and reduce labelling effort, particularly when domain randomization is used to vary imaging parameters, object appearance, and overall scene composition [15].

In agricultural and ecological applications, synthetic pipelines have been used to enrich training corpora with additional plant, weed, or animal instances, often by compositing 3D assets or partial patches into realistic backgrounds [3,4,5,6,7,14]. These approaches generally demonstrate that, when synthetic data are sufficiently diverse and physically plausible, models trained on mixed real–synthetic corpora can match or exceed the performance of models trained on real data alone, while requiring fewer manually labelled examples [3,4,5,6,7,16,17]. However, many of these pipelines target ground-based imagery or close-range laboratory setups and have not been instantiated for long-range aerial wildlife monitoring, where animals occupy only a few pixels and appearance changes rapidly with altitude and viewpoint [16,17].

1.2.2. Behaviour Modelling and Animal Movement

A crucial element for ecology-oriented synthetic data is the realism of animal behaviour. Classic work on flocking and crowd simulation showed that realistic collective motion can emerge from local interaction rules, exemplified by Reynolds’ boids framework and later social-force type models [18]. Subsequent variants capture a range of collective behaviours (such as schooling, flocking, and herding) by tuning parameters that govern how fast agents move, how far they sense neighbours, how they avoid collisions, and how strongly they align their directions of travel.

In ecology, agent-based models have been used for ungulates and other large herbivores to investigate how animals distribute themselves in space, move seasonally, and organise into groups under varying environmental conditions [19]. These models typically encode attraction to conspecifics, avoidance of barriers, and preferences related to habitat features (e.g., edges, water), leading to emergent patterns of group formation, fission, and fusion. For computer vision, this body of work is relevant because it suggests how to parameterize movement and interaction rules for synthetic agents so that emergent densities, occlusions, and trajectories resemble those observed in the field.

Despite this, many vision-oriented synthetic pipelines still rely on simplistic motion patterns (for example, independent random walks, scripted loops, or static placements) that fail to capture the temporal and spatial structure of real animal groups [14]. This limits their utility for evaluating detection and tracking algorithms that must operate under strong occlusions, partial visibility, and highly dynamic backgrounds, especially from moving UAV platforms. There remains a need for synthetic generators that integrate behaviourally informed group dynamics directly into the scene, rather than treating animals as independent, static assets.

1.2.3. UAV Datasets for Object Detection and Long-Range Monitoring

The last decade has seen a proliferation of UAV datasets for surveillance, traffic analysis, and environmental monitoring. Many of these resources focus on urban or peri-urban scenarios, providing annotated videos for tasks such as pedestrian or vehicle detection, tracking, and activity recognition [20,21]. Recent resources such as DetReIDx illustrate this trend: they contain multiple recording sessions of many individual subjects captured from UAV platforms across a wide range of altitudes, along with annotations that support detection, tracking, and person re-identification tasks [20]. These datasets are valuable for studying extreme viewpoint, scale and appearance variations in human-centric surveillance.

Other datasets, including RCSD-UAV, emphasise object detection in challenging UAV scenes by labelling a wide range of categories (vehicles, built structures, and pedestrians) across different heights, viewing angles, and environmental contexts [21]. Such datasets highlight the challenges of cluttered scenes, strong background variation, and small object sizes. However, their taxonomies and collection protocols are usually optimised for generic UAV applications rather than wildlife ecology: target classes are human-made or human-related objects, habitats are often urban or semi-urban, and flight plans are designed for coverage of infrastructure rather than long-range observation of wild animals.

For wildlife monitoring specifically, existing UAV datasets often concentrate on a single species or habitat, are limited in scale, or lack the altitude range and label detail needed to explore long-distance detection from high-flying platforms [16,22]. Moreover, many real datasets are too small to support extensive ablations on resolution, training regime, and label fraction without overfitting. This motivates complementary synthetic approaches that can simulate both the imaging geometry and the behaviour of targets across a broader range of conditions than is practical to acquire in the field.

1.2.4. Research Gaps in Existing Synthetic Pipelines

Several synthetic data generators are particularly relevant to animal-focused computer vision. For instance, the replicAnt [13] framework is built on Unreal Engine and renders articulated 3D animal assets within procedurally generated scenes, producing large image collections with ground-truth labels suitable for tasks such as detection, tracking, pose estimation, and segmentation. Similarly, Unity Perception offers a configurable platform for creating synthetic datasets for many computer vision tasks. It supports extensive randomization of scene properties and can automatically export several forms of ground-truth, including bounding boxes and semantic or instance segmentation masks [12].

However, these tools are primarily designed as flexible, general-purpose engines rather than UAV-specific pipelines. While replicAnt emphasises complex backgrounds and high-fidelity animal models, its default setups typically assume ground-based or close-range viewpoints and do not explicitly model UAV flight trajectories, gimbal motion, or altitude-dependent scale distributions [13]. Unity Perception, in turn, offers extensive randomization and labelling capabilities but leaves the specification of multi-agent behaviour, camera geometry, and task-specific scene logic largely to the user [12]. Both frameworks can, in principle, be configured for UAV wildlife applications, but performing so requires substantial custom engineering and does not directly address questions about transfer from high-altitude synthetic pre-training to independent real UAV datasets [11,12,14].

Taken together, the literature reveals three gaps. First, there is a lack of end-to-end pipelines that jointly model behaviourally realistic animal groups, UAV flight geometry and camera readout, and that are tuned for the extreme scale variation and occlusions encountered in long-range aerial wildlife imagery [11,12,13,14]. Second, while existing toolkits can generate high-quality annotations, they rarely provide detector- and tracker-ready labels (e.g., consistent track identifiers, scale- and altitude-aware statistics) tailored to ecological monitoring and downstream behaviour-sensitive analyses [12,13,23]. Third, few studies have systematically quantified how synthetic pre-training at realistic UAV altitudes transfers to independent real datasets collected under different acquisition protocols, resolutions and label budgets [8,24].

These gaps motivate the development of specialised pipelines that integrate behaviour-aware agent simulation with UAV-accurate imaging and automatic label export, and that are explicitly designed to support controlled transfer studies between synthetic and real UAV wildlife data.

1.3. Research Questions and Contributions

This study is organised around the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent can behaviour-aware synthetic data, generated at high UAV altitudes, support wildlife detection compared with training solely on real imagery?

RQ2: How does input resolution (e.g., 640 px versus 1280 px) influence the transfer of models pre-trained on synthetic data to real UAV images?

RQ3: How much real data is required after synthetic pre-training to recover most of the performance attainable with a fully labelled real dataset?

Within this scope, our work makes the following contributions:

- We introduce a behaviour-aware UE5 pipeline that jointly models animal group dynamics, UAV flight geometry, and camera readout, and exports detector-ready YOLO annotations together with instance masks and tracking metadata, bridging the gap between visual realism, behavioural realism, and UAV-accurate imaging;

- We instantiate this pipeline for high-altitude deer monitoring and generate a synthetic UAV dataset with automatically produced labels, enabling reproducible experiments in long-range wildlife detection and releasing the data for public use.

- We conduct a controlled evaluation of YOLOv8s under six training regimes and two image resolutions on both synthetic and real deer imagery, quantifying the effect of synthetic pre-training and scale on transfer performance.

- Based on these experiments, we derive practical guidelines for sample-efficient UAV wildlife detection, showing that high-resolution synthetic pre-training followed by fine-tuning on only a fraction of the real data can approach the accuracy of fully supervised training while substantially reducing manual annotation effort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. BEHAVE-UAV Synthetic Pipeline

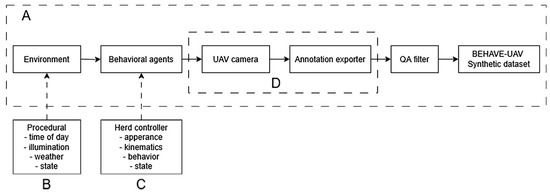

We build on Unreal Engine 5 (UE5 [25]) to construct a behaviour-aware synthetic data pipeline, which we refer to as BEHAVE-UAV. The main components of BEHAVE-UAV are summarised in Figure 1A–D. Figure 1A shows the high-level data flow from procedurally generated environments and behavioural animal agents through UAV flights and automatic annotation export to a QA-filtered synthetic dataset. Figure 1B–D detail the three core subsystems of the pipeline: the procedurally varied environment with domain randomisation (Figure 1B), the behavioural deer agents governed by a ground herd controller (Figure 1C), and the UAV platform with its camera and annotation exporter (Figure 1D). Finally, Figure 1 illustrates the quality-assurance filter that removes empty, degenerate or uninformative frames before constructing the final BEHAVE-UAV corpus. Section 2.1.1, Section 2.1.2, Section 2.1.3, Section 2.1.4 and Section 2.1.5 describe each of these components in more detail.

Figure 1.

Overview of the BEHAVE-UAV behaviour-aware synthetic data pipeline. (A) Overall data flow from procedurally generated environments and behavioural animal agents through UAV flights and automatic annotation export to a QA-filtered synthetic UAV dataset. (B) Procedural environment and domain randomisation. (C) Behavioural deer agents with a ground herd controller. (D) UAV platform and automatic export of RGB images and detector-ready annotations.

2.1.1. Overall Pipeline

Each simulation run follows the same high-level sequence. First, we instantiate a virtual environment from a set of terrain and vegetation templates, sampling configuration parameters for season, ground cover and lighting. Second, we populate the scene with a variable number of animal agents whose initial positions and internal states are drawn from prior distributions. Third, we initialise a virtual UAV at a prescribed altitude and execute a flight trajectory over the scene while a gimballed camera captures RGB frames at fixed temporal intervals. Finally, for every simulation step we export a multimodal annotation packet comprising RGB images, instance-level masks, 2D bounding boxes and per-object metadata. This packet is then converted into YOLO-format training labels and used to train and evaluate downstream detectors.

2.1.2. Environment and Domain Randomization

We instantiate a digital terrain mesh mapped to a height- and texture-coded landscape consisting of forest patches, clearings, and edge habitats. Vegetation assets (trees, shrubs, grass) are placed procedurally using blueprints that control species mix, density, and spatial clustering. To promote robustness and reduce overfitting to specific backgrounds, we apply domain randomization across several factors:

- time of day (e.g., morning, midday, evening);

- illumination conditions (direct sun, overcast, low sun angle);

- atmospheric effects (haze intensity, aerial perspective);

- ground moisture and vegetation state (dry and wet soil, green and brown foliage).

Global illumination and reflections are handled by the UE5 real-time pipeline [25]. These parameters are drawn independently for each simulation tile, yielding diverse backgrounds and lighting despite a fixed asset library. This follows standard domain randomization practice for visual transfer from simulation to real scenes [12,15] and is particularly important for long-range UAV imagery where background texture may dominate the frame.

2.1.3. Biological Agents and Behaviours

We model a forest ungulate class (deer) aligned with the downstream Rucervus dataset [22]. Each animal agent is represented by a template that exposes tunable properties in four groups:

- Appearance: a set of 3D mesh variants with different antler configurations, materials and texture sets.

- Kinematics: base speed, perception radius and maximum acceleration that govern physical motion.

- Social behaviour: interaction rules between nearby agents that approximate herd dynamics.

- High-level states: a finite state machine with states such as idle, walk and run, and context-dependent transitions.

Low-level motion is driven by a ground herd controller that coordinates up to 15 agents per group. It combines social-force-style interactions and short-horizon path planning on a navigation mesh, ensuring collision avoidance, coherent group motion and a realistic range of local densities and occlusions, in line with classic distributed behavioural models of flocks and herds [18]. Agents can enter and leave the camera frustum, partially occlude each other and interact with vegetation, producing motion patterns better aligned with behaviour-sensitive detection and tracking tasks.

2.1.4. UAV Platform and Automatic Annotation

To support aerial viewpoints, we integrate an autonomous UAV agent into UE5 (optionally via a Microsoft AirSim v1.8.1 autopilot interface [26]) to emulate realistic flight dynamics and camera readout. The UAV flies along spline-based trajectories whose control points are resampled for each simulation tile to vary flight direction, speed and path curvature. Our experiments focus on long-range wildlife monitoring at high altitude, so we emphasise nadir and near-nadir views.

We mount a single virtual RGB camera on a 3-axis gimbal. The camera has a 90° field of view and is oriented downwards towards the ground with small random perturbations in roll, pitch and yaw to mimic stabilisation imperfections. The capture loop samples frames at fixed simulation time intervals, typically every 100 ms, until the UAV has traversed the tile. For each captured frame, we export a multimodal annotation packet comprising:

- an RGB image at 1920 × 1080 resolution (16-bit colour);

- a per-pixel instance segmentation mask for all animal agents;

- per-object metadata (3D position and orientation in the global coordinate system, instantaneous velocity, agent identifier);

- YOLO-format bounding boxes, defined by normalised centre coordinates and box width and height.

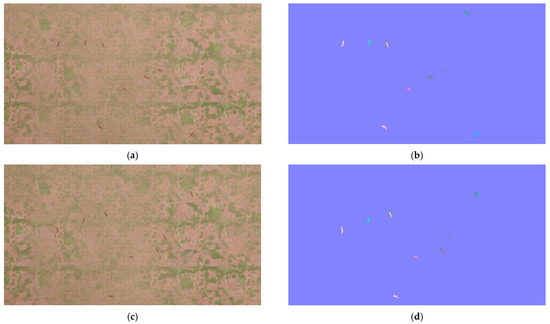

The instance masks are rasterised from agent meshes and projected into the image plane using the UAV camera calibration. YOLO bounding boxes are obtained by taking tight axis-aligned bounding boxes around each foreground mask. This ensures that labels accurately reflect visible extents, including partial occlusions and truncations at image boundaries. An example of RGB frames and their instance masks is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Synthetic UAV images (a,c) and corresponding instance segmentation masks (b,d) produced by the BEHAVE-UAV pipeline. From top to bottom: frame t and t + 2. These masks are exported together with persistent IDs and are used to produce tight YOLO bounding boxes and sequence-level labels. Different colors denote different deer instances (unique instance IDs).

In addition to frame-wise labels, the exporter writes per-object track metadata by enforcing a unique track ID per agent and monotonic timestamps. These attributes support multi-object tracking benchmarks and trajectory-level statistics; they can be evaluated with modern multi-object trackers such as ByteTrack and OC-SORT [27,28] and multi-object tracking metrics including HOTA and IDF1 [29,30].

2.1.5. Quality-Assurance Filtering

Before using the synthetic data for training and evaluation, we apply a simple quality-assurance (QA) filter to the exported frames. The purpose is to remove simulation failures and frames that are not informative for detection because all animals are either fully occluded or too small.

Concretely, we discard any frame that satisfies one of the following conditions:

- no valid animal instances are visible in the camera frustum;

- all bounding boxes are degenerate (zero or negative extent after projection);

- all visible animals are truncated at image borders such that their bounding boxes cover only a minimal number of pixels;

- the median bounding-box area across all instances in the frame falls below a small threshold relative to the full image area, i.e., < τ ⋯ W ⋯ H, where W and H are the image width and height.

In our implementation, we set τ = 10−3, so that frames in which all animals occupy less than 0.1% of the image area are discarded as being unlikely to provide stable gradients for training. These operations are implemented as inexpensive checks on the exported YOLO labels and can be run as a post-processing step on large simulation batches. The QA filter reduces annotation noise and ensures that the final synthetic corpus emphasises realistic, detectable targets at the resolutions of interest.

2.2. Synthetic Dataset

Applying the BEHAVE-UAV pipeline with the above configuration, we generate a synthetic UAV dataset for long-range deer monitoring. Each simulation tile produces a short video sequence and a set of QA-filtered frames with corresponding labels and metadata. Across all runs we obtain 2810 RGB frames at 1920 × 1080 resolution. The dataset is split into disjoint subsets for training, validation and an internal synthetic test set at the level of simulation tiles, so that validation and test tiles do not share trajectories or initial agent configurations with the training subset.

The synthetic dataset exhibits substantial variation in:

- animal count per frame (from isolated individuals to dense herds);

- viewing geometry (altitude, off-nadir angle, UAV heading);

- illumination and background (combinations of season, time of day and vegetation density).

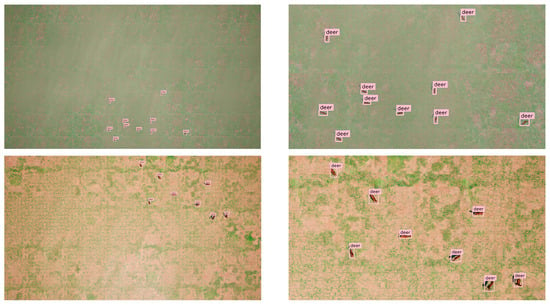

Examples of synthetic frames under different environmental conditions and viewing geometries are illustrated in Figure 3. For each frame we retain the outputs described in Section 2.1.4 (RGB image, YOLO-format bounding boxes, instance masks and per-object 3D metadata), enabling both standard 2D detection training and more specialised analyses such as scale distributions, trajectory-level behaviour and transfer across altitudes.

Figure 3.

Examples of synthetic UAV imagery and automatically generated YOLO bounding boxes under different environmental conditions (FOV 90°, altitude 70–100 m): (a) full rendered RGB 1920 × 1080 px frame with automatically generated YOLO bounding boxes (class = deer); (b) the same frame when zooming in on the area of the herd. Boxes originate from instance segmentation masks to minimise background leakage.

2.3. Real Dataset

To assess transfer from synthetic to real data, we use the publicly available Rucervus (swamp deer) dataset as our real-world reference [22]. It comprises 8210 annotated images in total, of which 6765 images were captured from UAVs and 1445 from handheld cameras across natural habitats, covering a range of backgrounds, flight heights and illumination conditions. Each image includes axis-aligned bounding boxes marking visible swamp deer.

We adopt the official data partition defined in the original Rucervus study [22] and used for YOLOv8s [9], YOLO11n [31] and RT-DETR-L [32] experiments: 6198 images for training, 1325 for validation and 687 for testing. In our experiments, the training split is used either to train detectors from scratch or to fine-tune models pre-trained on synthetic data; the validation split is used for early stopping and model selection; and the held-out test split is used exclusively for reporting final performance metrics. The UAV imagery in Rucervus was collected using DJI Mavic 2 Zoom, DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise and DJI Mavic Pro platforms (DJI, SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd.; Shenzhen, China), which introduce variation in sensor properties and operating altitudes. Further qualitative examples from the Rucervus dataset are shown in Section 3.4 to illustrate typical viewpoints, occlusions and label noise.

2.4. COCO-Pretrained Baseline

All our experiments use the same detector architecture, YOLOv8s, implemented via the Ultralytics framework. This small one-stage model offers a good compromise between accuracy and computational cost on resource-constrained UAV platforms, and its open-source implementation facilitates reproducibility.

As a transfer-learning baseline, we use YOLOv8s weights pretrained on MS COCO [10], as released by Ultralytics. The COCO corpus covers diverse object categories and scene types and is widely used as a generic pretraining dataset for object detection models. In our experimental regimes, models are either:

- initialised from COCO-pretrained weights and trained directly on real Rucervus images (real-only regimes), or

- initialised from COCO-pretrained weights, trained on synthetic BEHAVE-UAV data, and then fine-tuned on real Rucervus images (synthetic-pretrained regimes).

This design allows us to isolate the effect of synthetic pre-training while controlling for architecture and optimisation hyperparameters.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate detection performance using standard metrics derived from the Ultralytics implementation. Unless stated otherwise, we evaluate detections by matching predictions to ground-truth boxes using the Intersection-over-Union (IoU) criterion with a threshold of 0.5. From these matches we report:

- Precision (P) and recall (R) at IoU = 0.5, where a detection is counted as correct if its IoU with a ground-truth box is greater than 0.5;

- Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 (AP@0.5), defined as the area under the precision–recall curve obtained by varying the detection confidence threshold at IoU = 0.5;

- Mean Average Precision (mAP) computed as the mean of AP over classes (single class in our case) and, where relevant, over multiple IoU thresholds.

To study scale effects, we group ground-truth boxes by their image-plane area into three bins (small, medium, large). Let each YOLO label provide normalised width and height (wn, hn) ∈ (0, 1]. We define the normalised box area as follows:

A = w × h = (wnhn),

We then partition the ground-truth instances into three disjoint sets according to A:

Ssmall = {A|0 ≤ A < 0.02},

Smedium = {A|0.02 ≤ A < 0.10},

Slarge = {A|0.10 ≤ A ≤ 1.0}.

Smedium = {A|0.02 ≤ A < 0.10},

Slarge = {A|0.10 ≤ A ≤ 1.0}.

These thresholds play a role analogous to the COCO small, medium and large split, but are defined in terms of normalised area rather than absolute pixel size, which is more natural for our multi-resolution experiments (640 px and 1280 px). For each subset we compute an average precision value, yielding APsmall, APmedium, APlarge, precision and recall, which are reported on the real test set in Section 3.3.

2.6. Training Regimes and Experimental Design

Our experiments are designed to address the research questions in Section 1.3 by varying two key factors: (i) the data source and initialization strategy (synthetic vs. real, COCO-pretrained vs. synthetic-pretrained) and (ii) the input resolution. Across all regimes we keep the detector architecture, optimisation procedure and evaluation protocol fixed, so that differences in performance can be attributed to these factors rather than to changes in model capacity or training settings.

Detector and implementation. All experiments use the YOLOv8s detector implemented via the Ultralytics framework (see Section 2.4 for details on the COCO-pretrained baseline). We rely on the default Ultralytics YOLOv8s training settings for the optimizer, learning-rate schedule, regularisation, batch size and data augmentation. The complete configuration files are included in our public code repository to enable exact replication of our experiments. During training we resize inputs to either 640 × 640 px or 1280 × 1280 px, depending on the regime, while preserving the aspect ratio by letterboxing.

Data splits. For synthetic data we use the tile-level splits described in Section 2.2 (disjoint training, validation and internal synthetic test subsets). For the real Rucervus dataset we use the official train/validation/test partition reported in Section 2.3. All hyperparameter tuning and early stopping decisions are based on the corresponding validation split, and the real test split is used only for reporting final metrics.

Optimisation and stopping criteria. We train each model for up to 50 epochs and apply early stopping using the validation mAP@[0.5:0.95] (Section 2.5) as the criterion. If this metric fails to improve for 20 successive epochs (patience = 20), training is halted and the checkpoint with the best validation mAP@[0.5:0.95] is retained for final testing. Throughout, we report Precision, Recall, AP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] on the real test set, and where relevant, we additionally compute APsmall, APmedium and APlarge according to the scale-aware protocol in Section 2.5.

Augmentation settings. In all regimes we apply a consistent set of data augmentations: random horizontal flipping, HSV-space colour perturbations and moderate resizing and translation. Mosaic augmentation is activated with probability 0.5, and we enable multi-scale training in the specified high-resolution settings. Using an identical augmentation setup across regimes ensures that performance differences stem from the data source, initialization and input size rather than changes in augmentation strength.

Training regimes. We compare six training regimes that differ only in data source, initialization and input size:

- Synthetic-only @640 px. The model is initialised from COCO-pretrained YOLOv8s weights and trained on the BEHAVE-UAV training split using 640 × 640 px inputs. Validation and test evaluation are performed on the internal synthetic splits to verify that the synthetic pipeline and label export are functional.

- Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @640 px. The model is initialised from the same COCO-pretrained weights and trained solely on the Rucervus training split at 640 × 640 px. This regime represents the standard “real-only” baseline for the real dataset.

- Synthetic-pretrained + real fine-tuning (100%) @640 px. We first train the detector on the synthetic training split as in regime (1), then fine-tune the resulting weights on 100% of the Rucervus training split at 640 × 640 px. This regime isolates the effect of synthetic pre-training when the amount of real supervision is fixed.

- Synthetic-only @1280 px. As in regime (1), but with 1280 × 1280 px inputs. This configuration probes how much synthetic-only performance can be improved by increasing the input resolution, keeping the data source and optimisation settings fixed.

- Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @1280 px. As in regime (2), but with 1280 × 1280 px inputs. Together with regime (4), this regime quantifies the effect of higher input resolution on real-only training.

- Synthetic-pretrained + real fine-tuning with fractional real data @1280 px. We first train on synthetic data at 1280 × 1280 px as in regime (4), then fine-tune the resulting model on different fractions f of the Rucervus training split, with f ∈ {10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100}%. For each fraction f we draw a random subset of the training images of the corresponding size using a fixed random seed and keep the validation and test splits unchanged. Each fraction is trained once under the same optimisation settings and early-stopping rule. This design allows us to quantify how performance on the real test set grows with additional real supervision after synthetic pre-training, and to identify the point at which adding more real images yields diminishing returns.

Controlled comparisons. At 640 px, regimes (1)–(3) compare synthetic-only, real-only and synthetic-pretrained + full real training under identical architecture, optimizer and resolution, thereby isolating the role of the pre-training source. At 1280 px, regimes (4)–(6) examine how resolution and fractional real fine-tuning affect transfer: regimes (4) and (5) compare synthetic-only versus real-only training at high resolution, while regime (6) traces the sample-efficiency curve of synthetic-pretrained models as the amount of real data increases. In all cases, the evaluation metrics and test protocol are shared, enabling direct comparison across regimes.

Training hyper-parameters. For all detector architectures we keep the optimisation setup as consistent as possible, so that differences in performance can be attributed to the data source, initialization, input resolution and backbone type rather than to ad hoc tuning. Table 1 summarises the core training hyper-parameters used for YOLOv8s, YOLO11n and RT-DETR-L in our experiments, including optimizer type, base learning rate, batch size, learning-rate schedule, number of epochs, patience for early stopping and data-augmentation settings. Unless otherwise stated, these values are reused across all training regimes described above.

Table 1.

Training hyper-parameters for detector architectures.

These shared settings ensure that all detectors are trained under comparable computational budgets and regularisation strength, which is important for a fair comparison in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

2.7. Use of Generative AI

Generative AI tools were not used to generate or modify data, code, or results in this work. A large-language-model assistant (ChatGPT, OpenAI; model: GPT-5.2; accessed December 2025) was used solely to help with language editing and minor stylistic refinements under the authors’ supervision. The authors are fully responsible for the scientific content and conclusions presented in this work.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Detection Performance Across Training Regimes

We first compare the six main training regimes described in Section 2.6. Table 2 summarises the baseline detection performance on the Rucervus test set in terms of mAP@[0.5:0.95], precision and recall at the best validation epoch for each run.

Table 2.

Baseline detection performance across training regimes and input resolutions (YOLOv8s): mAP@[0.5:0.95], precision, and recall on the real test set at the best epoch.

At 640 × 640 px, the synthetic-only model trained on BEHAVE-UAV achieves a mAP of 0.54 with high precision (0.91) and recall (0.80), indicating that the behaviour-aware synthetic data alone already supports reasonably strong generalisation to the real test set. The real-only baseline, initialised from COCO and trained solely on Rucervus at the same resolution, obtains a lower mAP of 0.42 (precision 0.79, recall 0.66). Fine-tuning the synthetic-only model on 100% of the real training split at 640 px leads to a mAP of 0.40 (precision 0.76, recall 0.66), i.e., performance comparable to the real-only baseline. Overall, at this lower resolution, synthetic pre-training does not substantially change the final test performance once all real images are available for fine-tuning.

Increasing the input resolution to 1280 × 1280 px has a much stronger impact. The synthetic-only model trained on BEHAVE-UAV at 1280 px reaches a mAP of 0.79 with precision 0.97 and recall 0.97 on the Rucervus test set, substantially higher than all 640 px regimes. The real-only baseline at 1280 px improves over its 640 px counterpart (mAP 0.46, precision 0.78, recall 0.71) but still lags far behind the high-resolution synthetic-only model. These trends confirm that (i) resolution is critical for long-range deer detection from UAVs, and (ii) behaviour-aware synthetic training at high resolution can yield strong zero-shot transfer to the real test distribution.

Beyond the single-architecture baselines above, we additionally benchmarked one more convolutional detector, YOLO11n, and a transformer-based detector, RT-DETR-L, under the same 1280 × 1280 px training regimes. Table 3 summarises the resulting detection performance on the Rucervus test set. This comparison allows us to check whether the benefits of high-resolution training and synthetic pre-training are specific to YOLOv8s or hold across different backbone families.

Table 3.

Detection performance of convolutional and transformer-based detectors on the Rucervus test set (1280 × 1280 px).

Beyond the single-architecture baselines in Table 2, Table 3 benchmarks a second convolutional detector (YOLO11n) and a transformer-based detector (RT-DETR-L) under the same 1280 × 1280 px training regimes. Overall, YOLOv8s with real-only training remains the strongest configuration in terms of absolute mAP@[0.5:0.95] (0.46), while the smaller YOLO11n predictably underperforms its larger counterpart (0.42 mAP for real-only training). This difference is consistent with the reduced capacity of the YOLO11n backbone and indicates that, on a relatively small and specialised dataset such as Rucervus, model size still matters more than architectural novelty.

For both convolutional architectures, synthetic pre-training followed by fine-tuning on 50% of the real data yields performance that is close to the corresponding real-only baselines. For YOLOv8s, the mAP@[0.5:0.95] decreases from 0.46 to 0.41, but this loss is accompanied by a slight gain in precision (from 0.78 to 0.81) and only a modest drop in recall (from 0.71 to 0.69). A similar pattern is observed for YOLO11n, where synthetic pre-training keeps the mAP within 2 percentage points of the real-only model (0.42 vs. 0.41), again trading a small amount of recall for slightly higher precision. These results suggest that, for convolutional detectors, behaviour-aware synthetic pre-training largely preserves overall detection quality while allowing the real annotation budget to be reduced by half, and may even bias the models towards more conservative, high-precision predictions.

The effect of synthetic pre-training is substantially stronger for the transformer-based RT-DETR-L. When trained only on the full real Rucervus dataset, RT-DETR-L reaches just 0.11 mAP@[0.5:0.95], with low precision (0.35) and recall (0.45). In contrast, when initialised on BEHAVE-UAV synthetic data and fine-tuned on only 50% of the real images, RT-DETR-L attains 0.31 mAP@[0.5:0.95]—almost a three-fold improvement—alongside much higher precision (0.73) and recall (0.63). Interestingly, the best epoch for RT-DETR-L also shifts slightly earlier (43 vs. 49), indicating that synthetic pre-training not only improves final performance but also stabilises optimisation. Taken together, these cross-architecture results indicate that behaviour-aware synthetic data are particularly beneficial for data-hungry transformer-based detectors, while still providing competitive, sample-efficient performance for more mature convolutional families.

3.2. Effect of Real-Data Fraction After Synthetic Pre-Training

To quantify how much real supervision is required after synthetic pre-training, we analyse regime 6 (Section 2.6), in which a model trained on BEHAVE-UAV at 1280 × 1280 px is fine-tuned on varying fractions of the Rucervus training split. Table 4 reports the resulting mAP, precision and recall on the real test set for fractions of the training data ranging from 10% to 100% in steps of 10%.

Table 4.

Effect of real-data proportion during fine-tuning (synthetic-initialised YOLOv8s @1280 px): mAP@[0.5:0.95], precision, and recall on the real test set at the best epoch.

When only a small portion of the real training images is available (around 10–30%), performance remains modest: mAP stays below 0.35 and recall is limited, despite reasonably high precision (Table 4). The most substantial gains occur as the fraction increases from roughly one-third to one-half of the real training set. At 40% real data, the mAP rises to 0.37, and at 50% it reaches 0.41 with a precision of 0.81 and a recall of 0.69. Beyond this point, the curve flattens: between 60% and 80% real data mAP remains in a narrow band around 0.41–0.42, and even using the full training set (100%) does not yield a noticeable further increase (mAP 0.41, precision 0.77, recall 0.69).

Compared with the real-only baseline at 1280 px (mAP 0.46, precision 0.78, recall 0.71), the synthetic-pretrained model fine-tuned on only half of the labelled Rucervus images recovers most of the detection performance while using substantially fewer annotations. Additional real labels beyond roughly 60–80% of the training set bring only marginal improvements under the current training setup. This pattern suggests that high-resolution synthetic pre-training can make UAV wildlife detection considerably more sample-efficient: once a synthetic-pretrained model has been adapted using about half of the available real data, further manual labelling has diminishing returns.

3.3. Scale-Aware Behaviour and Distribution Shift

To investigate how object scale affects transfer, we adopt the COCO-style partition of ground-truth boxes by area (Section 2.5) and compute APsmall, APmedium and APlarge on the Rucervus test set. Using these thresholds, we obtain APsmall = 0.79, APmedium = 0.42 and APlarge = 0.26 for the best-performing high-resolution configuration. Thus, detection performance declines markedly as deer occupy larger fractions of the image, even though larger objects are usually easier to detect in conventional settings.

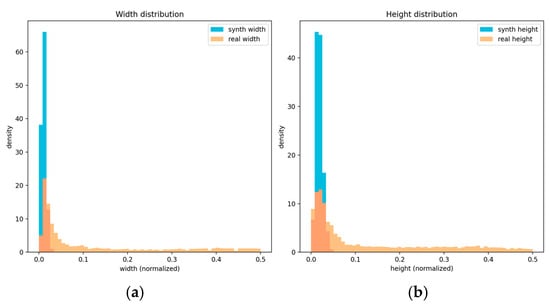

Figure 4 shows the histogram densities of normalised width and height for the synthetic and Rucervus datasets. Label statistics reveal a substantial box-size shift: synthetic BEHAVE-UAV images are dominated by small, high-altitude deer instances, whereas the real Rucervus test set contains a broader mix of small, medium and large deer, including closer-range views and partial crops at image borders. This distribution shift explains the observed asymmetry in AP: models trained predominantly on long-range synthetic imagery are particularly strong on small, distant targets (APsmall), but less calibrated on medium and large deer, where pose, texture and background differ more strongly from the synthetic training domain.

Figure 4.

Distributions of normalised bounding-box width and height for the BEHAVE-UAV synthetic dataset and the real Rucervus dataset: (a) width distribution (synthetic vs. real); (b) height distribution (synthetic vs. real).

These results support the qualitative finding that domain shift in this task is dominated by scale rather than by gross semantic differences. They also highlight the importance of matching altitude and effective pixel footprint when designing synthetic corpora for transfer to specific UAV deployment scenarios.

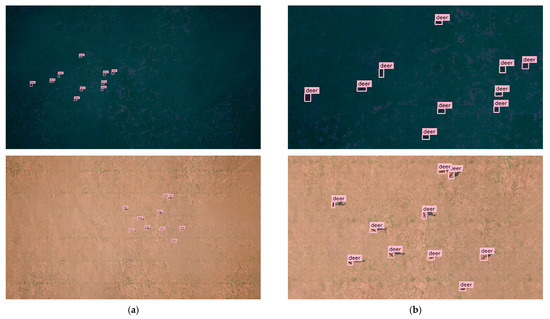

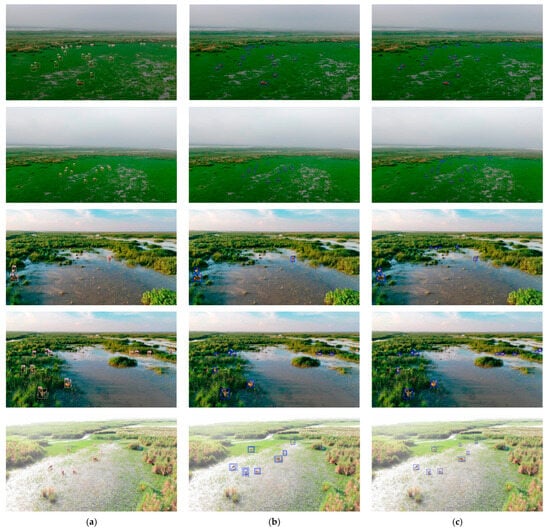

3.4. Qualitative Analysis on Real UAV Images

Finally, we qualitatively compare detections from a real-only model and a synthetic-pretrained model on real UAV imagery. Figure 5 illustrates representative examples: panel (Figure 5a) shows ground-truth boxes and predictions from a YOLOv8s model trained only on the Rucervus training split at 1280 px, while panel (Figure 5b) overlays predictions from a model pre-trained on BEHAVE-UAV high-altitude data and fine-tuned with 50% of the real training images.

Figure 5.

Qualitative detection examples on Rucervus UAV images for real-only and synthetic-pretrained YOLOv8s models at 1280 px: (a) Ground-truth bounding boxes (GT). (b) Predictions of the Real-only model trained from COCO-pretrained weights on the real dataset. (c) Predictions of the “Fine-tune on 50% real data” model initialised on synthetic high-altitude data and fine-tuned with 50% of the real training set. Pink boxes denote GT annotations and blue boxes denote model predictions.

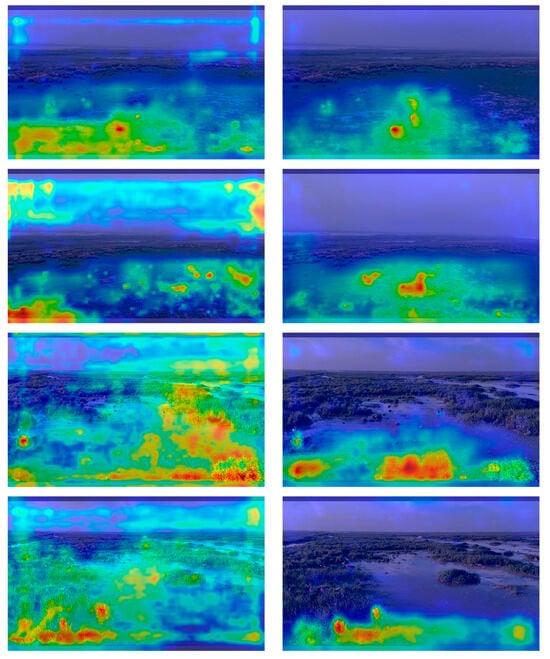

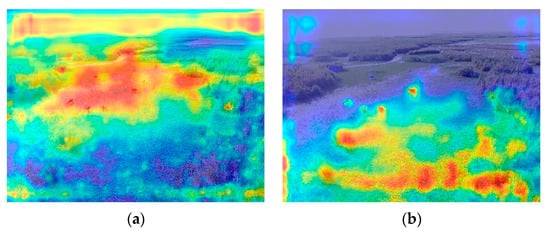

To better understand what visual evidence the detectors rely on, we generate Grad-CAM heatmaps for selected real UAV frames using the Ultralytics explain interface. For each image, we compare the real-only YOLOv8s model and the synthetic-pretrained + 50% real fine-tuned model. As shown in Figure 6, the real-only model often spreads its attention over large patches of grass or background structures, whereas the synthetic-initialised model concentrates energy on the animal silhouettes, especially for small and distant deer. This behaviour qualitatively supports the quantitative improvements in APsmall reported in Section 3.2.

Figure 6.

Grad-CAM visualisations on real UAV frames. Rows show different image examples. Columns compare detectors: (a) YOLOv8s real-only, (b) YOLOv8s synthetic-pretrained + 50% real fine-tuning. Warmer colours indicate regions that contribute most to the deer detection confidence. Synthetic-pretrained models place stronger attention on small and distant deer and are less distracted by background clutter.

Across typical scenes, we observe the following patterns:

- Small and distant animals. In frames where deer occupy only a few dozen pixels, the synthetic-pretrained model tends to detect more true positives than the real-only model, producing fewer missed small objects at similar precision. This aligns with the quantitative behaviour in Section 3.3, where improvements are concentrated in the APsmall regime.

- Moderate scale and partial occlusion. For medium-sized deer under partial occlusion by vegetation or other animals, the synthetic-pretrained model often recovers occluded individuals that the real-only model misses, resulting in higher recall at comparable precision.

- Close-up animals. When deer are large in the frame, both models perform well in most cases. Occasional failures are typically due to annotation issues (e.g., ambiguous or incomplete labels) or boundary truncation at image edges rather than systematic detector errors.

- Background confounders. False positives, though infrequent, tend to arise from background structures, such as logs, rocks or high-contrast vegetation patches, that resemble deer in shape or texture at long range. Both models can be affected, indicating that these errors stem from scene-appearance ambiguity rather than from the specific training regime.

During the qualitative review, we repeatedly observed confident detections on animals that appear to be unlabelled or under-labelled in the Rucervus ground truth, particularly at long range. This suggests that the reported quantitative metrics are conservative: if some true objects are missing from the annotations, precision and recall on small, distant targets are underestimated relative to the detector’s effective field performance. At the same time, the qualitative examples confirm that synthetic pre-training does not introduce obvious artefacts on real UAV imagery and can improve robustness to the small, partially occluded animals that are most challenging in long-range wildlife monitoring.

4. Discussion

Next, we discuss and summarise the main conclusions from our experiments with behaviour-aware synthetic data of dynamic animals recorded from high altitudes:

- High-resolution input is essential for the target use case. In the simulated high-altitude regime, increasing the input size from 640 px to 1280 px substantially boosts mAP@[0.5:0.95] (from 0.54 to 0.79 in our setting) and nearly saturates the precision–recall curves. This confirms that providing more pixels per deer is critical for small-object detection in wide-area UAV imagery and that low-resolution configurations under-exploit the available information.

- Synthetic pre-training followed by fractional real fine-tuning is sample-efficient. At 1280 px, fine-tuning on 50% of the real Rucervus data achieves around 95% of the best average precision obtained with the full real training set, and the performance curve plateaus around 0.42 mAP@[0.5:0.95] as the fraction of real data grows. This suggests a practical workflow for ecological UAV monitoring: generate synthetic data at the correct altitude and scale, then annotate and fine-tune on only half of the real corpus while retaining most of the achievable accuracy. These findings are consistent with prior studies on synthetic-to-real transfer and domain randomization for robotics and autonomous driving, where synthetic pre-training plus limited real fine-tuning yields strong downstream performance [11,15,24].

- Domain shift is dominated by scale. Deer appear substantially larger in real frames than in our synthetic distribution, especially when UAVs fly at lower altitudes or orbit closer to the animals. Without explicit scale-aware augmentation, models remain biased toward tiny objects and underperform on close-ups, consistent with the scale-specific AP breakdown: improvements on synthetic-like small targets do not fully transfer to large, near-field animals.

- Synthetic initialisation behaves differently for convolutional and transformer-based detectors. For convolutional models (YOLOv8s and YOLO11n), synthetic pre-training followed by fine-tuning on 50% of the real data yields mAP@[0.5:0.95] that is within 1–2 percentage points of the full real-only baselines (0.46 vs. 0.41–0.42), while slightly increasing precision and incurring only modest recall loss. This indicates that behaviour-aware synthetic pre-training preserves most detection quality while halving the real annotation budget, and tends to bias the models towards more conservative, high-precision predictions. In contrast, the transformer-based RT-DETR-L benefits much more strongly: its real-only training reaches only 0.11 mAP, whereas synthetic pre-training plus fine-tuning on 50% of the real data raises mAP to 0.31 and markedly improves both precision and recall. Synthetic pre-training also shifts the best epoch earlier in training, suggesting more stable optimisation. Together, these cross-architecture results indicate that our synthetic pipeline is particularly helpful for data-hungry transformer-based detectors, while still providing competitive, sample-efficient performance for more mature convolutional families.

In terms of practical implications, our findings suggest several directions that would likely improve performance further:

- Keep the effective input size around 1280 px and enable multi-scale training or inference to better cover the range of UAV altitudes encountered in practice;

- Use tile-based inference for scenes with very small deer in very wide fields-of-view, so that each tile preserves sufficient resolution per animal without exceeding memory constraints;

- Add scale-mix augmentations (for example, random crops and resizes that keep animals large within the crop) to better cover the real close-up distribution and explicitly address the observed scale mismatch;

- Expand or rebalance the real training split with additional empty frames and a small set of deliberately hard examples (occlusions, shadows, cluttered backgrounds), and revisit label noise, because our qualitative analysis indicate false negatives when deer are heavily clustered or partially occluded.

Compared to existing UE-based synthetic pipelines such as replicAnt [13] and Unity Perception [12], our simulator focuses on behaviour-aware agents and UAV-accurate camera geometry rather than static asset placement alone. By encoding collective motion, occlusions, and temporal artefacts (motion blur, rolling shutter) at realistic altitudes and fields-of-view, BEHAVE-UAV narrows both the appearance and dynamics gaps to field deployments, which in turn improves small-object and partially occluded wildlife detection.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. (a) The biodiversity breadth is currently restricted to deer-like ungulates, and our findings may not immediately transfer to species with radically different morphology or behaviour (e.g., birds, arboreal mammals). (b) Rendering is RGB-only; we do not yet model thermal or multispectral channels, which are important for nocturnal monitoring and dense canopy. (c) Extreme weather, seasonal changes and canopy density are approximated via style randomisation rather than explicit physical modelling. (d) Despite behaviour-aware agents, synthetic animals still cannot fully reproduce natural gait, fine-scale fur reflectance, or rare edge cases such as interactions with infrastructure. We partially mitigate these limitations via diverse style randomisation and independent real tests, but we expect new regions or species to still require short fine-tuning on local data. Overall, for pasture and forest-edge monitoring, the proposed pipeline offers a rapid bootstrap with minimal manual labels and incremental updates via style variation and a modest real subset; on edge devices, standard quantisation and input scaling provide viable frame rates when latency is critical.

5. Conclusions

We presented a behaviour-aware, UAV-accurate synthetic data pipeline for wildlife detection and demonstrated that it transfers effectively to a real UAV dataset with moderate fine-tuning. The key ingredients—agent dynamics, camera geometry, domain randomisation and end-to-end auto-labelling—jointly improve robustness to illumination, weather, altitude and motion blur while reducing annotation cost. In contrast to prior UE-based synthetic platforms that primarily randomise static layouts [12,13], BEHAVE-UAV explicitly models animal–animal and animal–camera interactions over time, which is important for ecological monitoring at high altitudes.

On the real Rucervus test set, fine-tuning from synthetic pre-training improves steadily with more real data and plateaus around 60–80% of the available training set, indicating good sample efficiency. Across multiple detectors, behaviour-aware synthetic pre-training largely preserves performance for convolutional architectures (YOLOv8s, YOLO11n) while reducing the required number of real labels by roughly half, and it substantially improves the performance of the transformer-based RT-DETR-L compared to real-only training. Scale mismatch between synthetic and real imagery emerges as the dominant source of domain shift; high-resolution training and scale-aware augmentation are therefore crucial for successful transfer. For UAV wildlife monitoring at 70–100 m above ground level, a practical recommendation is to train synthetic data at 1280 px and then fine-tune on approximately 50% of the real dataset. This configuration yields strong accuracy with moderate annotation effort and provides a reproducible pipeline for deployment and benchmarking in ecological UAV applications.

Future Work

The current implementation covers only the RGB modality and a limited set of animal taxa. In future work, we plan to broaden the class set beyond deer to include additional herbivores and potentially avian species, and to add thermal or multispectral rendering for low-light and canopy-occluded scenarios. Also, our agents could be endowed with more complex decision-making and task-driven behaviours, closer in spirit to the virtual laboratories used in comparative cognition research, such as the Animal-AI Environment [33,34]. On the methodological side, we intend to explore more explicit scale-normalisation mechanisms (for example, tile-based training, adaptive cropping, and scale-mix augmentations), as well as ablations between static and behaviour-driven scenes to better quantify the contribution of agent dynamics. Finally, we aim to investigate semi-supervised and active-learning pipelines that exploit synthetic pre-training and pseudo-labelling of real UAV data to further reduce manual annotation effort while maintaining or improving detection performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and project administration, L.T.; methodology and data curation, L.T.; software and virtualization, L.T. and K.V.; validation and formal analysis, L.T., L.A. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T. and K.V.; writing—review and editing, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation (agreement identifier 000000C313925P3U0002, grant No 139-15-2025-003 dated 16 April 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. The synthetic dataset used in the experiments is available at https://github.com/by-LZ-for/Synthetic-Dataset-Generation-for-Object-Detection-in-UAV-Ecological-Applications.git, accessed on 6 November 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thatikonda, M.; PK, M.K.; Amsaad, F. A Novel Dynamic Confidence Threshold Estimation AI Algorithm for Enhanced Object Detection. In Proceedings of the NAECON 2024—IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, Dayton, OH, USA, 15–18 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, A.D.; Jarin, A.; Yaniasih, Y.; Afra, D.I.N.; Nurfadhilah, E.; Pebiana, S. Latest Research in Data Augmentation for Low Resource Language Text Translation: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and Its Applications (IC3INA), Bandung, Indonesia, 9–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Burridge, J.; Blok, P.M.; Guo, W. A Patch-Level Data Synthesis Pipeline Enhances Species-Level Crop and Weed Segmentation in Natural Agricultural Scenes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadesmaeilketabforoosh, K.; Parfitt, J.; Nikan, S.; Pearce, J.M. From blender to farm: Transforming controlled environment agriculture with synthetic data and SwinUNet for precision crop monitoring. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, B.B.; Popescu, S.; Rajan, N.; Leon, R.G.; Reberg-Horton, C.; Mirsky, S.; Bagavathiannan, M.V. Use of synthetic images for training a deep learning model for weed detection and biomass estimation in cotton. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumoglou, N.; Pechlivani, E.M.; Tzovaras, D. Generate-Paste-Blend-Detect: Synthetic dataset for object detection in the agriculture domain. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 5, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H. ObjectDetection in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pavlick, E. Does Training on Synthetic Data Make Models Less Robust? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.07164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. YOLO by Ultralytics, Version 8.0.0. Computer Software. Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.; Chahl, J. A Review of Synthetic Image Data and Its Use in Computer Vision. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkman, S.; Crespi, A.; Dhakad, S.; Ganguly, S.; Hogins, J. Unity Perception: Generate Synthetic Data for Computer Vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.04259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plum, F.; Bulla, R.; Beck, H.K. replicAnt: A pipeline for generating annotated images of animals in complex environments using Unreal Engine. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, I.; Qiu, W.; Hager, G.; Yuille, A. Learning from Synthetic Animals. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.08265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J.; Fong, R.; Ray, A.; Schneider, J.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Domain Randomization for Transferring Deep Neural Networks from Simulation to the Real World. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xu, D.; Xu, F.; Chen, F. Wildlife Real-Time Detection in Complex Forest Scenes Based on YOLOv5s Deep Learning Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klukowski, D.; Lubczonek, J.; Adamski, P. A Method of Simplified Synthetic Objects Creation for Detection of Underwater Objects from Remote Sensing Data Using YOLO Networks. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.W. Flocks, Herds, and Schools: A Distributed Behavioural Model. In ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 21, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koger, B.; Deshpande, A.; Kerby, J.T.; Graving, J.M.; Costelloe, B.R.; Couzin, I.D. Quantifying the movement, behaviour and environmental context of group-living animals using drones and computer vision. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DetReIDx Dataset Page. Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/detreidxv1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Geng, W.; Yi, J.; Li, N.; Ji, C.; Cong, Y.; Cheng, L. RCSD-UAV: An object detection dataset for unmanned aerial vehicles in realistic complex scenarios. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucervus, D. Duvaucelii (Barasingha) UAV Dataset. Mendeley Data (Version 1). Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/53nvjhh5pg/1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Romero, A.; Carvalho, P.; Côrte-Real, L.; Pereira, A. Synthesizing Human Activity for Data Generation. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Gupta, A.; Kaveti, P.; Singh, H.; Ostadabbas, S. Bridging the Domain Gap between Synthetic and Real-World Data for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epic Games. UE5 Lumen Global Illumination and Reflections—Technical Documentation. Available online: https://docs.unrealengine.com/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Shah, S.; Dey, D.; Lovett, C.; Kapoor, A. AirSim: High-Fidelity Visual and Physical Simulation for Autonomous Vehicles. In Field and Service Robotics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. ByteTrack: Multi-Object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Pang, J.; Weng, X.; Khirodkar, R.; Kitani, K. Observation-Centric SORT: Rethinking SORT for Robust Multi-Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 9686–9696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. HOTA: A Higher Order Metric for Evaluating Multi-Object Tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristani, E.; Tomasi, C. Features for Multi-Target Multi-Camera Tracking and Identification. In CVPR Workshops 2016; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.J.; Patel, P.; Tesch, J.; Yang, J. BEDLAM: A Synthetic Dataset of Bodies Exhibiting Detailed Lifelike Animated Motion. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudouris, K.; Slater, B.; Cheke, L.G.; Schellaert, W.; Hernández-Orallo, J.; Halina, M.; Patel, M.; Alhas, I.; Mecattaf, M.G.; Burden, J.; et al. The Animal-AI Environment: A virtual laboratory for comparative cognition and artificial intelligence research. Behav. Res. 2025, 57, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.