Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed cooperative navigation framework based on LSTM and dynamic model information fusion integrates airflow-angle prediction with the - scheme to suppress inertial drift and enhance navigation robustness under GNSS-denied.

- A consistency-based node optimization strategy identifies high-precision UAV nodes via altitude and wind-speed consistency evaluations together with geometric constraints.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- This work demonstrates that the framework achieves the navigation objective of short-term stability and long-term drift suppression of the leader layer in GNSS-denied.

- The designed node selection strategies improve the cooperative navigation reliability and robustness, confirming the feasibility and effectiveness of the framework.

Abstract

In GNSS-denied environments, achieving accurate and reliable positioning for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) formations remains a major challenge. This paper presents a cooperative navigation framework for UAV formations based on LSTM and dynamic model information fusion to enhance formation navigation performance under GNSS-denial. The framework employs a dual-driven hierarchical architecture that integrates an LSTM-based dynamic state predictor with historical motion features, including velocity, acceleration, airflow angle, or thrust, thereby enhancing the robustness and positioning accuracy of the leader UAV layer. Furthermore, a multi-source optimal selection strategy based on consistency evaluation is developed to dynamically fuse pseudo-GNSS (P-GNSS), barometric altitude (BA), and wind-speed consistency information, optimizing node allocation between the leader and follower layers. In addition, an IMM-based resilient fusion filtering algorithm is introduced for the follower UAV layer, incorporating UWB, wind-speed, and external-force estimations to maintain reliable navigation under UWB outages and leader-node degradation. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly improves positioning accuracy and formation stability, exhibiting strong adaptability in complex GNSS-denied environments.

1. Introduction

Most of the currently employed UAVs are equipped with onboard inertial measurement units (IMUs) as well as position-aware sources such as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) systems [1], motion capture (MoCap) systems [2], radio frequency (RF) signals [3], electromagnetic signals [4], and ultra-wideband (UWB) systems [5]. However, these sensors increase the overall system complexity, leading to higher costs; more importantly, their performance strongly depends on environmental conditions [6]. In particular, interference with and denial of GNSS signals pose a serious threat to flight safety, during large-scale formation flight operations [7].

Compared with external sensors, model information assistance does not require physical sensors, as it originates from the intrinsic model constraints of the platform and can be exploited to update navigation states when external sensors fail or are unavailable. Model-based assistance offers two main advantages over external sensor-based assistance: avoiding additional hardware-related costs and continuous availability. Such information is generally derived from kinematic or dynamic models. Specifically, model-assisted information transforms knowledge of platform motion into pseudo-measurements, which are then fed back into the navigation filter. Its key feature is that prior knowledge of the INS carrier platform or its operating environment can be directly converted into measurement information to support navigation filtering [8]. Typical approaches include zero-velocity updates [9], zero-heading updates [10], and relative position updates, which have been widely applied in mobile robots, pedestrian navigation, and UAVs. On the other hand, dynamic models, containing inherent state information, can be regarded as a unique, embedded virtual sensor suite. Model-assisted INS can be applied in the absence of external sensors, and in terms of aiding navigation, it is fundamentally analogous to actual sensors, exhibiting heterogeneous characteristics. For different UAV platforms, the corresponding dynamic models do not constrain exactly the same states within the navigation system; however, when integrated into the system’s filter fusion framework, their constraint effects are functionally equivalent to those of conventional sensors [11].

In addition to serving as an auxiliary information source, dynamic model information provides powerful physical predictions, primarily manifested in aerodynamic or hydrodynamic effects, which are typically not measurable by conventional sensors [12]. UAV dynamic models have been employed for various purposes, including control, navigation performance enhancement, replacement of other sensors, sensor fault diagnosis, and action selection through learning [13]. Consequently, dynamic models have also been utilized as substitutes for inertial measurement units (IMUs) in GNSS-integrated navigation, enabling attitude determination in the absence of an IMU [14]. In model-assisted approaches, precise INS dynamic models are employed, with Koifman and Bar-Itzhack [15] being notable pioneers in this field. In their work, a comprehensive dynamic model of a fixed-wing UAV was proposed as an alternative to GNSS, wherein errors in the model coefficients and parameters were estimated using an extended Kalman filter (EKF) during flight. In other words, this approach establishes a bidirectional correction mechanism between the inertial navigation system and the dynamic model [16].

A common feature in the current UAV state estimation literature is that dynamics-based estimators can adapt in real-time to rotational and translational drag parameters while providing smooth, lag-free inertial acceleration estimates [17]. Estimators capable of online model parameter estimation, without the need for expensive sensors or additional measurement sources, enable the large-scale deployment of high-performance, low-cost UAVs [18]. Moreover, most mainstream navigation approaches focus on the optimal fusion of onboard proprioceptive sensors and exteroceptive instruments to measure UAV motion and environmental signals.

In practice, a group of flying robots (FRs) exhibits greater robustness than a single flying robot and can accomplish more complex tasks [19]. For cooperative modes of data link systems, numerous studies have been conducted to achieve high-precision kinematic model-assisted navigation for multiple UAVs. Yang et al. proposed a multi-UAV cooperative navigation method based on relative distance and magnetic sensor measurements [20], in which UAV kinematic models were constructed using the outputs of magnetic sensors. For the minimal cooperative unit composed of a navigator UAV with known position and follower UAVs with unknown positions, Zhu et al. [21] proposed a CP algorithm based on the motion vectors of follower UAVs. Zhou et al. [22], within the random finite set (RFS) theoretical framework, presented a multi-agent navigation algorithm based on the probability hypothesis density (PHD) and cardinalized PHD (CPHD) filters. The proposed algorithm redefines virtual potential fields, enabling agents to avoid obstacles according to their relative velocities. Beyond UAV kinematic model assistance, substantial research has also explored model-assisted approaches for underwater vehicles (UVs) [23], marine vehicles (MVs) [24], and land vehicles [25].

However, applications of dynamic model-assisted navigation in the field of cooperative navigation remain limited, primarily because they rely heavily on the platform’s own dynamic information and cannot interact with other UAVs. Relative position updates, in contrast, require sensor redundancy on the UAVs [26]. Integrating additional vehicle dynamic constraints with a state estimation fusion framework can further enhance navigation performance [27], particularly improving robustness in complex environments and operating conditions. According to previous studies, dynamic model-assisted navigation systems can be categorized into two main approaches based on the type of UAV dynamics [28]: thrust-based [17] and aerodynamic-based [29]. While these methods are primarily designed for UAVs, the classification is also applicable to underwater vehicles and land vehicles.

In addition, most studies on dynamic model-assisted navigation focus solely on the data fusion level, unlike visual navigation, which emphasizes feature-level fusion. In fact, some dynamic models cannot be directly set as measurement information; their variation trends often better represent the current state of the UAV. Data-level fusion is regarded as the fundamental fusion strategy, directly fusing raw data from sensors, such as radar and camera measurements [30]. For navigation systems, data-level navigation primarily addresses issues related to information uncertainty [31], data heterogeneity [32], and data correlation [33]. While data-level fused navigation can effectively preserve raw measurements, offering high accuracy, reliability, and low noise, it suffers from large data volumes and poor real-time performance, and is limited to processing homogeneous data. Due to the relatively weak robustness of data-level navigation, appropriate fusion algorithms must be designed.

Therefore, feature-level fusion has been proposed as an approach to extract relevant data features, producing more refined features or higher-level outputs, such as decisions [34]. Feature extraction typically involves information such as position and velocity from radar data, and edge or texture features from images. By combining the advantages of heterogeneous sensors at the feature level, the accuracy and richness of feature extraction can be improved [35]. Additionally, integrating carrier dynamic features in navigation methods to accurately characterize the motion properties of the platform under specific environments, tasks, and scenarios represents an effective multi-source cooperative navigation approach. Yang et al. [36] proposed an adaptive Kalman filtering framework that determines the contributions of dynamic model information and observation model information in the PNT fusion results based on their deviations, thereby achieving multi-source fusion of dynamic features and navigation information [37]. At a finer scale, the sensors embedded within multi-source navigation systems and the dynamics of the system itself exhibit distinct information features during their evolution. Precisely characterizing these sensor and dynamic information features is beneficial for enhancing the perception accuracy of the navigation system. By extracting a more detailed and comprehensive set of features, both similar and heterogeneous information can be effectively processed. Although this approach is suitable for large-scale data scenarios, information loss is inevitably encountered.

Research has been conducted on the self-learning capabilities of carrier multi-source information, focusing on the reliability and completeness of navigation system decision-making [38]. Different scoring metrics are constructed based on the weights and importance of various tasks and are subsequently fused in a weighted manner, ultimately enabling intelligent, reliable decision-making and dynamic iterative optimization in multi-source autonomous navigation systems [39]. In the face of continuously changing scenarios and environments, unpredictable faults and disturbances, and dynamically evolving navigation tasks, deep learning leverages neural networks to perform regression and data fitting based on sensor predictions, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods and inconsistencies in data [40]. To this end, imitation learning can be employed to integrate cooperative navigation information features into a learning framework, whereby navigation databases are collected and neural networks are trained to generalize across other scenarios, thus achieving intelligent decision-making and dynamic iterative optimization for navigation behaviors in complex environments.

To explore the application of dynamic model information in cooperative UAV clusters, this paper proposes a cooperative navigation framework based on LSTM and multi-information fusion. In GNSS-denied scenarios, the historical motion states of UAV clusters, including acceleration and velocity, exhibit consistency. Due to the similar characteristics of their dynamic constraints, these historical dynamic data can be effectively exploited [41]. The specific contributions of this work are as follows:

- This paper proposes an LSTM-based complementary cooperative prediction framework integrating airflow-angle prediction with the - scheme under GNSS-denied. The predicted airflow-angle correction facilitates mitigating drift accumulation and improving the stability of state estimation, while the concurrent use of P-GNSS observations imposes closed-loop constraints on inertial position errors. This dual mechanism effectively suppresses inertial drift, enhances overall navigation accuracy and robustness, and provides a basis for subsequent hierarchical fusion and node selection optimization.

- A consistency-based node optimization strategy is developed for hierarchical architecture and node selection. This strategy introduces a high-level consistency evaluation by constructing statistics of altitude differences of BA/P-GNSS measurement, enabling real-time detection of severe P-GNSS drifts and selecting out high-precision layers. Moreover, through joint wind-speed consistency evaluation and geometric optimization, high-precision nodes with superior prediction reliability are identified as leader nodes for follower-layer navigation.

- Building on the consistency-evaluated hierarchical layers, a modified geometric configuration-based IMM filtering algorithm is proposed to flexibly fuse multi-source node information, integrating leader-node multi-sensor data and dynamic model-assisted information such as UWB, wind speed , or external force estimates . This algorithm enhances system robustness under GNSS-denied conditions when facing various contingencies, including UWB outages and leader-node accuracy degradation, and significantly improves navigation accuracy at the follower node layer.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the proposed framework. Section 3 describes the design and training of the LSTM network using historical dynamic features. Section 4 details the Leader’s filter design with AHRS integration based on the RIEKF. Section 5 introduces the hierarchical cooperative navigation subfilter. Section 6 presents experimental validation and performance evaluation. Finally, Section 7 concludes the article and outlines future research directions.

2. Proposed Framework

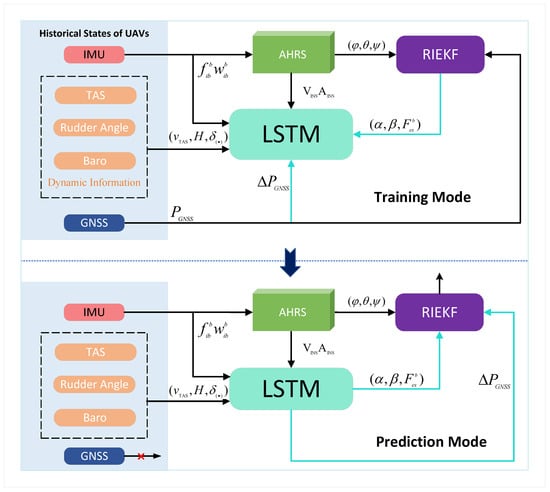

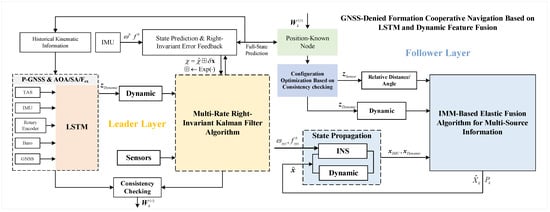

As shown in Figure 1, the core of this framework lies in utilizing the dynamic models embedded in historical data as auxiliary information sources and integrating them into the information fusion process to address challenges in GNSS-denied environments. The overall cooperative framework is primarily divided into leader-node and follower-node layers. Among them, the leader-layer nodes achieve higher prediction accuracy, while the follower-layer nodes rely on the leader-layer information as a reference for assisted navigation correction. The leader-node layer employs an AHRS-based RIEKF full-source navigation algorithm, fully integrating predicted dynamic information under GNSS-denied conditions. The follower-node layer leverages UWB measurements and wind field estimates from the selected leader nodes to perform filtering and fusion of the leader layer’s dynamic information. Unlike the sensor-based fusion methods, this approach emphasizes leveraging the prior knowledge contained in historical dynamic models. When a homogeneous UAV cluster passes through a given region in formation navigation, its dynamic states exhibit consistency. This implies that the dynamic behavior patterns of the UAVs are both predictable and reproducible.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cooperative navigation.

In addition to GNSS position increment prediction, this work employs an LSTM network to learn dynamic models from historical trajectories, leveraging dynamic information to reduce the difficulty of directly predicting coordinates. The original historical dynamic data are utilized either directly or indirectly in current navigation estimation, avoiding complex model identification or environmental modeling processes, and representing an efficient data reuse strategy. To fully exploit multi-source information features, this work distinguishes leader and follower node layers based on P-GNSS/BA consistency evaluations, while proposing an optimization strategy that combines wind speed consistency with geometric configuration characteristics for node selection within the follower layer. To address the elastic fusion of multiple leader-node information, a consistency-based cooperative factor is introduced at the follower-node layer, establishing a modified IMM-based multi-source elastic fusion filtering model.

4. RIEKF-Based Leader Layer’s Positioning with AHRS

4.1. System State

When exploring the auxiliary correction of the dynamic model, it is inseparable from the prediction and estimation of the airflow angle. Due to the estimation iteration of the attitude not meeting the traditional additive rules, it is reflected in the update of the state quantity and covariance. Therefore, it is more appropriate to establish and on the manifold . The process of updating and compensation is more suitable for the use of mature Lie group theory to improve the accuracy and consistency of estimation [29].

By integrating the attitude estimates provided by the AHRS (Attitude and Heading Reference System) based on the magnetometer, IMU accelerometer, and gyroscope with the predictions from LSTM-assisted navigation, a collaborative navigation RIEKF main filter centered on the AHRS is established. The 15-dimensional full-system nominal state variables employed in the design are defined as follows:

where indicates the pose and velocity of the vehicle. represents the tri-axial bias error for the IMU’s gyroscope and accelerometer. is the attitude rotation matrix of the air flow coordinate system relative to the body frame, and indicates the wind speed magnitude.

The sub-model and prediction model adopt the advanced manifold-based Error-State Right-Invariant Extended Kalman Filter algorithm, which is designed to enhance convergence and estimation accuracy in the presence of disturbances. The system state is represented in the error-state form, and the right- (or left-) invariant error is defined as follows:

where , , and represent the invariant errors of attitude, velocity, and position, respectively, while and denote the bias errors of the gyroscope and accelerometer in the body frame , respectively.

Therefore, the error formulation of RIEKF satisfies the following equation:

where

where denotes the right-invariant state of the system.

The continuous-time state propagation model of the system can be expressed by the following equation:

where represents the gravitational acceleration projected in the n-frame, and denotes the skew-symmetric matrix operator.

Although the AHRS provides high-accuracy attitude measurements, slow drift errors still exist. To balance estimation accuracy and computational efficiency, the attitude angle errors from the AHRS are modeled as a first-order Markov process:

where denotes the correlation time of the first-order Markov process for the attitude angle errors, and represents the Gaussian white noise associated with the AHRS attitude errors.

The continuous-time right-invariant dynamics model of the system is given by:

where represents the right-invariant state transition matrix and denotes the right-invariant noise excitation matrix.

Multiplying both sides of (9) by results in the invariant state error component , consistent with the group affine property. This can be expressed as follows, where the bias states that don’t satisfy the group affine property are represented additively:

The system dynamics error model is derived based on the right-invariant error definition (Equation (13)) and the system state update equation (Equation (10)). In previous work [44], detailed derivations of the dynamics and measurement equations for IEKF are presented. The continuous-time transition matrix of the system, , can be expressed as:

where the error state transition matrix is associated with the attitude, velocity, and position, and represents the transition matrix of the error states, where denotes the zero matrix and denotes the identity matrix. Its expression is given as follows:

The matrix representing the relationship between the attitude velocity position (avp) error state and the bias error states is shown in (16).

The following mainly establishes the error dynamics equation of the airframe-body rotation matrix. However, since the iterative estimation of attitude does not meet the traditional additive rules, which is reflected in the update of the state variables and covariance, it is preferable to establish and on the manifold . The process of updating and compensating them is more suitable for using mature Lie group-related theories to improve the accuracy and consistency of estimating and . The error state update matrix for and , denoted as , is expressed as follows:

4.2. Measurement Submodel

4.2.1. Relative Measurement Update

When the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) has access to GNSS signals, the correction of positioning errors can be achieved solely through the INS/GNSS sub-filter. However, in GNSS-denied environments, the UAV relies on communication links established with surrounding nodes to obtain relative ranging information and employs cooperative navigation algorithms to determine its own position. The relative distance and angle between the follower UAV and the leader node can be expressed as:

The error equation of the relative measurements is described as follows:

The linearization process can be obtained by

where

By employing the left-invariant form, it can be directly expressed as:

Considering that the state variable is a group element, the measurement innovation can be defined as follows:

According to the derivation in [29], the GNSS measurement innovation can be further transformed into the following linear equation:

where is trajectory-independent. Since the right-invariant error representation is adopted, needs to be transformed into through the adjoint matrix. According to the derivation of the invariant Kalman filter, one has . Substituting this relation into (24) yields:

Therefore, the following transformation holds:

where

By substituting into (25), we obtain:

4.2.2. Barometer Update

Without loss of generality, the error model of the barometer after temperature compensation is established as Gaussian white noise, as shown in (29).

where represents the absolute altitude.

The barometer measures the altitude information in the frame. Since the barometer and GNSS share the same coordinate system, the measurement is one-dimensional, as expressed by the following equation:

where is the dimensionality reduction matrix.

4.2.3. Airspeed Tube

The airspeed sensor measures the magnitude of airspeed in a-frame, and its error model is established as a Gaussian white noise model.

where v denotes the error of the airspeed sensor measurement, and represents zero-mean Gaussian white noise with variance .

The relationship between true airspeed and ground speed is shown in (32).

Therefore, can be solved for using the altitude, and .

In this study, a dynamics-aided navigation approach based on the leader UAV is adopted, incorporating the predicted and the estimated wind velocity . Because the derived from airspeed is independent of both and , the Jacobian for (33) need not be computed explicitly.

Based on (24), similar results can be obtained. Then, the airspeed update equation can be written as follows:

The matrix is the observation matrix derived from the airspeed update equation.

5. Improved IMM-RIEKF-Based Positioning Method for the Follower Layer

5.1. Dynamic Feature and Consistency Assessment

5.1.1. Maximum Likelihood Estimation Theory

Due to the limited temporal span and numerical range of historical dynamic data, the prediction phase is prone to error accumulation. To improve prediction reliability, this work introduces a dynamic information consistency evaluation method based on maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which assesses the consistency between two types of observations and quantifies the reliability of model predictions. MLE identifies the model parameters most likely to have generated the observed data. First, barometric altitude (BA) and predicted P-GNSS data are evaluated using MLE to assess their consistency weights with predicted values, filtering out the low-accuracy layer. Next, the consistency of wind speed estimates within the high-accuracy layer is assessed to provide weights for the elastic fusion of multi-source information in the low-accuracy layer.

The core assumption of this framework is that if two information sources represent the same physical quantity and their error distributions are known and reasonable, the resulting maximum likelihood solution should be statistically consistent and pass hypothesis testing. The proposed method relies on three key assumptions: (1) the two observations are mutually independent; (2) each observation’s error relative to the true value follows a zero-mean Gaussian distribution; and (3) both observations correspond to the same unknown true value . The following illustrates the maximum likelihood estimation process using barometric altitude (BA) as an example.

where and indicate that the barometric altitude measurement and the prediction based on historical data follow normal distributions with the true altitude as the mean and variances and , respectively. To jointly fuse the two types of altitude information, and , a joint likelihood function parameterized by the true altitude can be constructed:

where the probability density functions of individual observations are given by:

According to (37), the joint likelihood function can be rewritten as:

Solving the above equation gives the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE):

where .

5.1.2. Consistency Assessment

For two uncorrelated observations, the inverse-variance weighted residual represents the overall deviation after fusing the two measurements, defined as

where denotes the overall uncertainty of the height difference between the LSTM estimate and the barometer (BA), reflecting the combined noise effect of the two measurement sources, and is given by

To evaluate the consistency level between the two altitude observations, a normalized height-difference statistic is introduced after the weighted residual (40) computing, defined as:

This statistic normalizes the residual according to the uncertainty weights of the different observation sources, facilitating a comparison of altitude estimate consistency on a unified scale. and are the residuals of the GNSS-LSTM and barometric measurements with respect to the maximum likelihood estimate, defined as

To improve measurement utilization and robustness against sudden noise, an enhanced IGG robust strategy is proposed. A consistency factor is defined to weight the agreement between subfilter predictions and observations, and a hierarchical fusion approach is employed to optimize measurement integration. Separate consistency factors are constructed for the altitude and airspeed channels, denoted (altitude) and (wind speed). The weighting function is then formulated following the IGG segmented strategy as:

where and are the segmented thresholds of the observation weighting function, linked to the current innovation magnitude . The adaptive weight is dynamically adjusted according to this magnitude, serving both as a measure of observation consistency and as a reference to regulate the influence of associated subnodes on the leader node.

5.2. Improved Geometric Configuration Optimization Strategy

Multi-node cooperative localization can be viewed as a state prediction process, with performance evaluated via the prediction error covariance matrix. The Cramér–Rao inequality provides a lower bound on the covariance of any unbiased estimator, whose inverse—the Fisher information—is commonly used to quantify the state information contained in the measurements.

In general, a larger Fisher Information indicates that the system model or measurement process provides richer information, thereby reducing the uncertainty in state prediction and enhancing overall estimation accuracy and robustness. For the state error correction of the assisted UAV, the observation equation can be expressed as

where denotes the measurement vector from cooperative nodes, including relative distance measurements between nodes; represents the UAV state vector; is the measurement matrix; and is the observation noise vector associated with ranging and angular measurements, given by .

To further analyze the system performance, the posterior information matrix is simplified in the horizontal plane as an example. Assuming the measurement noise covariance matrix is constant and negligible in most practical applications, the posterior information matrix can be defined as:

where the observation matrix is defined as:

Then the traditional performance metric for multi-UAV cooperative localization is constructed, defined as the inverse of the trace of the information matrix [45]:

where represents the angular difference between two cooperative UAV nodes at time . A smaller value of indicates lower uncertainty in position estimation and better cooperative observation performance.

Considering measurement errors and potential deviations in leader node performance, for a cooperative system with N nodes—where each subnode communicates with 2 to other nodes—the Fisher information matrix for each subnode can be constructed to evaluate system performance. Specifically, for node n, the Fisher information matrix is defined as:

where denotes the standard deviation of ranging errors between node n and node k, and is a Dirac function that equals 1 if node n is connected to node k, and 0 otherwise. represents the predictive consistency factor of the leader node k from (42), reflecting its reliability, with values ranging from 0 (completely unreliable) to 1 (fully trustworthy).

The node information matrix incorporates geometric relative positions between nodes (via angles ), measurement error levels (via ), and leader node reliability (via ), thereby enhancing robustness and performance evaluation in cooperative localization. According to the Cramér–Rao inequality, the lower bound of the position estimation variance for node n is given by the inverse of its information matrix:

This bound represents the theoretical limit of estimation error and serves as a system performance metric, validating the effectiveness of the multi-node cooperative configuration optimization strategy incorporating the leader node consistency factor .

5.3. IMM Framework for Multi-Source Fusion

To enable effective fusion, a unified framework is developed to integrate heterogeneous sensor measurements from different subsystems and to dynamically allocate submodel fusion weights based on prior sensor performance in previous studies [46]. Building on this framework, a dynamic ATPM scheduling strategy incorporating multi-source credibility information is developed.

5.3.1. Resilient Interactive

Since all submodels are processed synchronously and in parallel, an effective fusion of the common state from their estimation results is required. The IMM algorithm, grounded in Bayesian theory, provides the theoretical basis for this process [47]. According to Bayesian theory, the predicted prior probability of the i-th submodel is expressed as:

where is the probability of the j-th sub-model at the previous step . The likelihood value denotes the probability of observing the current measurement given the model and its predictions. The interactive probability sum for the sub-models is:

Finally, after each sub-model completes its measurement update, the overall system state and covariance matrix are obtained by fusing the interactive weights from all sub-models:

5.3.2. Model Transition Probability

This subsection presents a dynamic adjustment mechanism for the model transition probability matrix in the IMM algorithm, driven by a multi-source information Credibility Performance Index. The proposed method enables flexible switching among multiple models while preserving strong scenario adaptability and ensuring compatibility with the IEKF algorithm [48].

The strategy leverages the robustness of the IMM multi-model framework and the geometric consistency of the IEKF, thereby accelerating convergence and mitigating the effects of accuracy discrepancies or partial sensor failures in heterogeneous multi-source data. The model transition probabilities are calculated as follows:

- (1)

- Computation of Submodel Weights: The cooperative navigation system consists of n leader nodes, each forming a submodel with m sensors. Since the study focuses on optimizing relative-information/dynamics cooperative subfilter configurations, sensor setups are assumed identical across UAV platforms. Specifically, the fusion credibility weight of each submodel can be represented by the leader node consistency. The credibility weight of the j-th leader node in the i-th submodel is obtained by averaging as follows:where denotes the credibility index of the sensor combination in the j-th leader node layer of the i-th submodel. denotes the predictive consistency weight of the leader node layer corresponding to the i-th submodel.This weight not only reflects the performance stability of the leader node but also provides critical support for subsequent IMM model probability updates and state fusion.After the weights of all submodels are obtained, normalization is carried out:

- (2)

- Calculate the self-transition probability :where b represents the baseline probability, which encapsulates the inherent tendency of each model to maintain its current state without external observational influences.

- (3)

- The transition probability between submodels, , is computed as , with the remaining probability uniformly distributed among the other models. This uniform allocation ensures a balanced “competitive” environment among the submodels, especially when precise evaluation of each transition probability is difficult.

6. Experimental Analysis

6.1. Experimental Setup

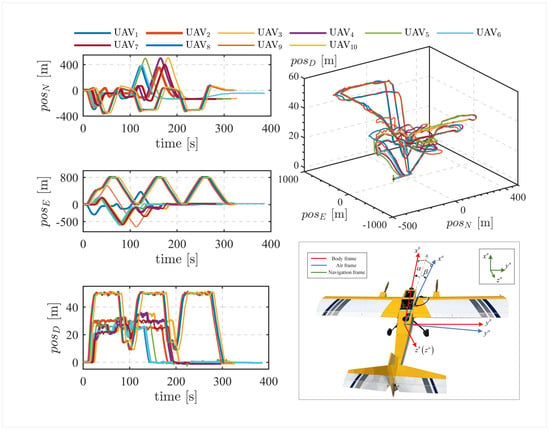

To assess the practical effectiveness of the proposed fusion algorithm, offline validation was performed using flight data collected from fixed-wing UAVs. To further demonstrate the applicability and robustness of the proposed method under realistic operating conditions, a series of cooperative flight experiments was carried out with a fleet of ten UAVs flying at different altitudes and formation trajectories in GNSS-denied environments. The speed characteristics of the UAVs involved in the experiments are consistent. The flight paths and platform configurations are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flight paths of leader and follower UAVs.

Each UAV was equipped with a comprehensive sensor suite. The flight control system incorporated an ADIS16488 Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), operating at a sampling rate of 100 Hz, which integrates a three-axis gyroscope, three-axis accelerometer, three-axis magnetometer, and UWB ranging modules, and a barometer. The GNSS subsystem utilized a NovAtel receiver with a sampling rate of 5 Hz. A wireless communication network links the UAVs, enabling the follower to access the leader data. The detailed specifications and sampling rates of the onboard sensors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specifications of Multisensors on the fix-wing UAVs.

6.2. Navigation Performance Analysis of the Leader Node Layer

6.2.1. Prediction Results of the LSTM Network

To evaluate the proposed formation-consistency-aided navigation algorithm, commonly observed state information from historical trajectory data was first used to train UAV swarms under GNSS-denied conditions. The trained model was then employed to predict AOA and estimate P-GNSS increments, thereby facilitating the assessment of both prediction accuracy and the feasibility of the resulting estimates.

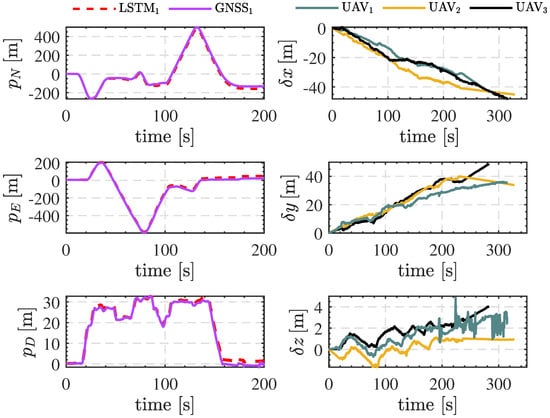

As shown in Figure 4, the integration of P-GNSS incremental information produces the reconstructed P-GNSS results and the corresponding error comparison with RTK measurements. To evaluate generalizability, multiple UAV nodes experienced GNSS denial 30 s after takeoff, at which point predictions were initiated. The results indicate that the overall prediction trends closely follow the RTK reference. In principle, navigation schemes incorporating P-GNSS increments are sufficient to maintain accurate positioning and stable attitude convergence.

Figure 4.

Multi-Node OINS-PGNSS Prediction and Error Curves.

However, as indicated by the error curves on the right-hand side of the figure, the P-GNSS estimates gradually diverge, with divergence rates varying across UAV nodes. This observation confirms the previously noted characteristic of being “effective in the short term but unreliable in the long term.” For different UAV platforms, relying solely on P-GNSS incremental predictions may not satisfy the stringent requirements of practical engineering applications. Therefore, in addition to identifying nodes with short-term reliable P-GNSS predictions, the proposed framework incorporates predicted AOA information to improve long-term navigation reliability.

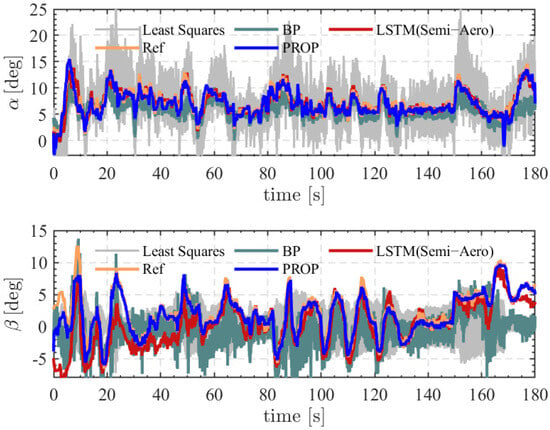

This study leverages readily available historical states to construct a dynamical mapping relationship, thereby avoiding reliance on conventional UAV parameters and enabling online enhancement of airflow angle estimation in terms of both consistency and reliability. As shown in Figure 5, to evaluate the effectiveness of the LSTM network trained on historical flight trajectories, the estimated AOA and SA were compared across LSTM, BP, and LS models. The results indicate that although the BP neural network exhibits a trend similar to that of the proposed LSTM, the latter achieves substantially higher prediction accuracy. Furthermore, compared with the semi-aerodynamic LSTM [44] that relies on ground parameters, the full-aerodynamic LSTM developed in this study demonstrates superior performance in airflow angle prediction. Therefore, integrating the LSTM network with the state estimation system can effectively improve the accuracy of airflow angle estimation.

Figure 5.

Estimated AOA and SA under Different Network Models (LSTM, BP, and LS).

It should be noted that, during certain phases (e.g., the initialization stage), substantial discrepancies occur between the estimated values and the ground-truth measurements. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the limited representativeness of historical trajectory data, which inherently constrains the model’s fitting capability. Moreover, the magnitude and occurrence of such errors vary across UAV platforms and flight conditions. To mitigate this limitation, a consistency evaluation mechanism is subsequently introduced, and adaptive weights are assigned based on the evaluation results to serve as reliability criteria for estimation.

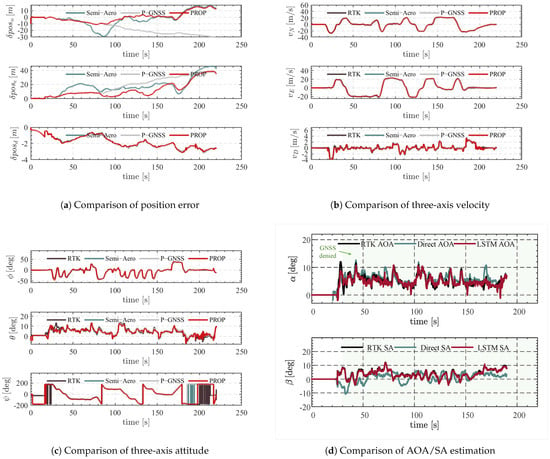

6.2.2. Analysis of RIEKF Filtering Results Based on AHRS

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the proposed LSTM-based historical trajectory training model in supporting navigation under GNSS-denied conditions is evaluated, where complementary fusion is implemented, and navigation accuracy across different states is compared. To ensure consistency, the first 220 s of flight data were used for simulation, with GNSS denial imposed at s. The algorithms compared in this experiment include: (i) RIEKF corrected by the full aerodynamic model (proposed method), (ii) RIEKF corrected by P-GNSS, and (iii) RIEKF corrected by the semi-aerodynamic model. Specifically, the P-GNSS-corrected RIEKF reduces to a P-GNSS/INS-based maneuver-aided correction of pure inertial navigation during the GNSS-denied period, serving as the baseline for comparison. In contrast, the semi-aerodynamic corrected RIEKF relies on barometer and airspeed updates to substitute for GNSS measurements, with aerodynamic angles estimated using the semi-aerodynamic prediction model.

Figure 6b,c present the velocity and attitude estimation results obtained from the full data sequence for the different algorithms, where the black curve represents the RTK-based reference solution, the green curve corresponds to the semi-aerodynamic RIEKF, and the red curve denotes the proposed method. Since the AHRS ensures attitude stability, the differences in attitude estimation accuracy across the compared algorithms are negligible. Regarding velocity accuracy, the proposed method (PROP) outperforms the semi-aerodynamic RIEKF, whereas the Semi-Aero method slightly surpasses the P-GNSS-corrected RIEKF due to its capability for velocity correction.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Leader UAVs’ result analysis of different algorithms.

Figure 6a presents the position trajectories and error comparisons of the three approaches 30 s after GNSS failure. Compared with the P-GNSS baseline, the proposed algorithm demonstrates the dual advantages of “short-term stability and long-term drift suppression”: the position error not only increases more slowly but also remains consistently constrained without significant oscillations throughout the flight.

Specifically, the system conducts an online evaluation of the BA/P-GNSS altitude consistency at approximately 90 s. When the vertical error exceeds a predefined threshold, the corresponding channel is immediately frozen, and the system seamlessly switches to the full aerodynamic model architecture, effectively preventing altitude drift from propagating into the horizontal channels. As summarized in Table 2, under a 190 s GNSS-denied scenario, this strategy reduces the maximum position drift from 70 m to 55 m, lowers the RMSE from 18.24 m to 7.37 m, and decreases the equivalent drift rate by approximately 20%. Additionally, the navigation survival time is extended from 1 min to nearly 2 min, providing a practical transition window for the reactivation of absolute observation sources such as GNSS.

Table 2.

Comparison of precision indexes of three-axis position estimation.

Compared with the semi-aerodynamic (Semi-Aero) scheme, the proposed method (PROP) exhibits only a 1.5 m difference in northward drift and approximately 7.5 m in eastward error. The most notable improvement is observed in the RMSE: PROP demonstrates substantially lower position fluctuations than Semi-Aero, confirming that the P-GNSS plus full aerodynamic fusion framework effectively mitigates the robustness limitations of the semi-aerodynamic model. In addition, the vertical channel remains constrained by the barometer throughout the entire flight, maintaining a steady-state error within 3 m.

Figure 6d presents the comparison of AOA and SA estimations under GNSS-denied conditions. The direct estimation method (Direct AOA/SA) exhibits large errors in both AOA and SA, with a pronounced divergence, particularly in SA estimation. This degradation is primarily attributed to the method’s strong dependence on velocity measurements, which become unreliable in the absence of GNSS, resulting in poor estimation performance.

Specifically, SA is highly sensitive to the lateral velocity component v. Under low-speed or high-maneuvering conditions, velocity errors are amplified through trigonometric relationships, leading to severe fluctuations or even divergence in angle estimates.

In contrast, the proposed LSTM-based full aerodynamic model leverages historical flight data to capture the underlying flight dynamics. Even under GNSS signal loss, it can predict aerodynamic angles with high accuracy. By implicitly modeling the nonlinear relationships among aerodynamic forces, vehicle states, and sensor measurements, while exploiting the consistency in historical trajectories, the proposed method achieves substantially improved AOA and SA estimation performance, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing navigation robustness under GNSS-denied conditions.

6.3. Follower Node Layer Navigation Performance Analysis

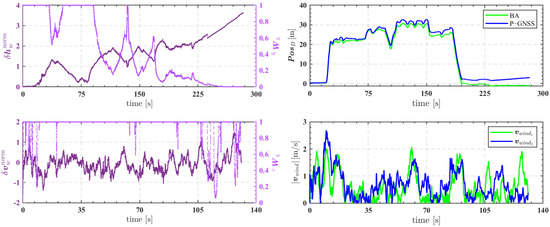

6.3.1. Consistency Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the constructed normalized statistics in assessing observation consistency, the consistency evaluation results for BA/P-GNSS and wind speed estimates from multiple UAVs are compared. Taking wind speed as an example, the consistency evaluation among UAV nodes considers pairwise estimation deviations. For multiple UAV nodes, the absolute deviation and the normalized statistic are computed. Based on the ICG segmentation strategy, a weight representing the consistency of wind speed estimation is derived.

To further analyze the effectiveness of the normalized statistic in reflecting the consistency of P-GNSS predictions, Figure 7 presents the temporal evolution of the normalized statistic (denoted as ) for wind speed and altitude estimation tasks, along with the corresponding consistency weights () derived using the ICG strategy. The right subplots provide a comparison between altitude and wind speed estimation results. As observed, the normalized statistics exhibit substantial temporal fluctuations, with magnitudes closely related to estimation deviations among UAV nodes. When the statistic is highly correlated with deviations (weight approaching 1), it indicates that the statistic reliably reflects consistency; conversely, when the correlation is weak (weight approaching 0), the statistic may fail to capture consistency information and should be reconstructed.

Figure 7.

Consistency Evaluation for Leader Layer BA/P-GNSS and Wind Speed .

Specifically, for altitude estimation, the normalized statistic remains relatively smooth during the initial phase (30–80 s), and the consistency weight largely stays at a high level (near 1), with only minor reductions in certain intervals. This behavior is attributed to the altitude channel providing more reliable observations. The vertical positioning accuracy, influenced by P-GNSS predictions, ensures that altitude estimation deviations remain within a controllable range, offering a reference for preliminary selection of high- and low-precision layers under GNSS-denied conditions. Notably, around 125 s, the consistency weights of two BA/P-GNSS channels simultaneously decrease, reflecting the degradation of altitude consistency after prolonged divergence ().

In contrast, for the wind speed estimation scenario, around 105 s the system experiences an external disturbance, resulting in significant differences in wind speed magnitudes among UAV nodes. The normalized statistic exhibits a distinct peak, indicating increased estimation discrepancies between nodes 1 and 2. The ICG mechanism adjusts the weight to reflect the low consistency of these UAVs’ wind speed estimates. This procedure not only selects a set of high-consistency, high-precision UAVs but also serves as a cooperative factor for elastic fusion at the follower layer.

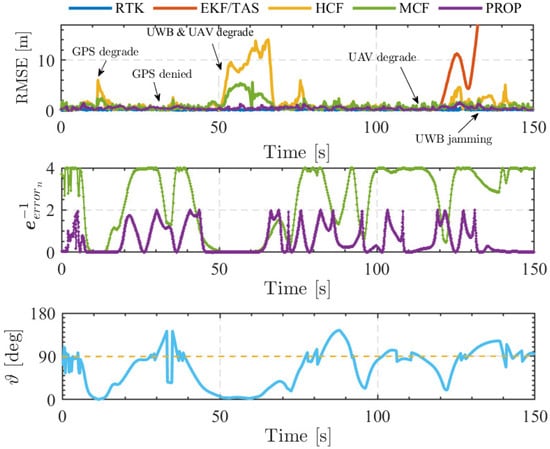

6.3.2. Elastic Analysis of IMM Subfilter with Geometry Configuration Optimization

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed improved geometry configuration optimization-based cooperative algorithm, this study focuses on the elastic fusion of leader nodes, analyzing the combined influence of configuration and reference node performance, and assessing its applicability in a real-world system. As described previously, based on the screening of BA/P-GNSS and wind speed estimation consistency, the formation system is partitioned into two precision layers: a high-accuracy leader layer and a low-accuracy follower layer. The follower layer relies on relative information from the leader layer and auxiliary dynamic information. Navigation and positioning under GNSS-denied conditions are achieved using the elastic fusion algorithm built upon the improved IMM framework.

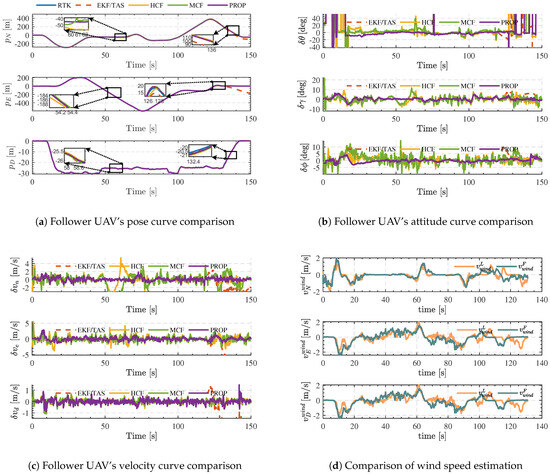

In the experiments, all nodes are initialized with consistent sensor measurements, initial covariance matrices, and measurement noise covariance matrices. During the cruise phase, different levels of perturbations are applied to the leader node signals to simulate dynamic variations in reference node performance and configuration. For the follower layer, Figure 8 and Figure 9a present the RMSE error curves and position/attitude variations under various scenarios, including GNSS degradation (20–30 s) and denial (from 30 s), leader node accuracy degradation (50–80 s and 100–135 s), UWB signal degradation (50–80 s), and UWB outage (135–150 s). As shown in Figure 9d, it can be observed that the wind estimates between the leader and follower nodes reveal a strong consistency, demonstrating the effectiveness of using wind information from the leader UAV as an auxiliary input for cooperative navigation.

Figure 8.

Follower UAVs’ position error and comparsion of the various CL algorithm.

Figure 9.

Follower UAV’s velocity avp and comparison by using different methods.

The proposed elastic IMM fusion algorithm with improved configuration optimization was evaluated by comparison with the EKF/TAS algorithm, the HCF algorithm (random signal source selection), and the MCF algorithm (traditional configuration optimization [45]) to assess its robustness and effectiveness. As shown in Figure 8, the position error curve of UAV Node 1 indicates that, although the traditional HCF algorithm suppresses the follower UAV’s position error to some extent, the MCF method—due to its multi-signal-source selection—achieves superior suppression. However, both methods still underperform compared to the proposed algorithm. Under conditions of the leader node and UWB accuracy degradation, the horizontal channel error is maintained within 1 m during the first 20 s of flight. When only the leader node accuracy degrades after 110 s, the maximum error remains below 2 m. This improvement is attributed to the interaction between the submodel transition probability matrix and the cooperative factor , which enables the submodels to exploit adaptive elastic advantages during interaction.Moreover, although the MCF and the proposed configuration-based method share similar geometric alignment, the inverse error matrix differs. Specifically, during the 50–70 s interval, under perturbations and UWB performance degradation, the weight of the reference leader node approaches zero, causing the information matrix to also approach zero. Similarly, during the 135–150 s UWB outage of Submodel 1, although remains non-zero, is directly set to zero. Previous studies (HCF, MCF) did not consider the impact of reference node performance, often resulting in overestimation of . In the proposed multi-UAV cooperative navigation framework, the follower layer’s multi-source selection mechanism accounts for both the information matrix (related to the relative configuration between nodes) and the intrinsic accuracy of the leader nodes.

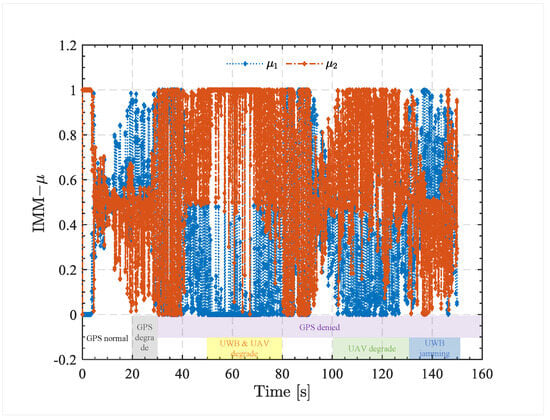

Figure 10 presents the posterior probabilities of the IMM submodels under perturbation injection. It can be observed that, during the 20–30 s interval, the weights of Submodel 1 and Submodel 2 remain near the midline, indicating a complementary state. During 50–80 s, due to perturbations applied to Leader 1 and UWB performance degradation, rapidly approaches zero while becomes dominant. This indicates that Submodel 1 becomes unreliable and its weight decreases, whereas the more reliable Submodel 2 seamlessly takes over, maintaining system stability. Similarly, during the 100–135 s phase, a small perturbation is applied to the leader node, and the weights of Submodel 1 and Submodel 2 differ only slightly. During the 135–150 s UWB outage, Submodel 1 is rendered completely untrustworthy, and the IMM algorithm switches to a new Submodel 1 at 135 s. Figure 9b,c show the attitude and velocity error curves of the UAV nodes. Comparative analysis indicates that attitude and velocity fluctuations are significantly smaller than those of the HCF and MCF algorithms, with no noticeable jumps during model-switching phases. The proposed algorithm consistently exhibits superior robustness and high accuracy in position, attitude, and velocity estimation across all fault-injection scenarios, as summarized in Table 3.

Figure 10.

Switching results of IMM posterior probability .

Table 3.

Comparison of precision indexes of position estimation.

Moreover, its accuracy and stability under GNSS-denied conditions further validate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed system for real-world applications. As shown in Table 3, under injected disturbances, the proposed algorithm is compared with RTK observations and existing methods, including the MCF algorithm and conventional configuration optimization approaches. The results indicate that, while the MCF algorithm can partially suppress the position errors of follower UAVs, the inclusion of the cooperative weight in the proposed method further enhances positioning accuracy. Specifically, the improved IMM algorithm effectively selects appropriate cooperative information to improve follower UAV localization.

Additionally, the experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with a 13th-generation Intel Core i7-13700H processor, and the algorithmic models were implemented in MATLAB 2023a. The total algorithm execution duration was set to 150 s, with a time step of 0.01 s. The proposed algorithm required a total runtime of 68.85 s, corresponding to an average computation time of 4.588 ms per time step, which satisfies the real-time operational requirements of systems.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes a hierarchical cooperative navigation framework based on historical dynamic model information and multi-source sensor data fusion to address the challenges of cluster navigation in GNSS-denied environments. By combining P-GNSS and AOA/SA estimations, the framework achieves the navigation objective of short-term stability and long-term drift suppression, thereby maintaining node-layer navigation accuracy in the absence of GNSS. Node selection strategies constructed from altitude and wind-speed consistency evaluations, together with geometric constraints, improve the collaborative reliability of leader and follower node layers, while a modified IMM filter enables elastic fusion of multi-source information, effectively enhancing the robustness of follower systems in complex environments. Simulations and experiments separately evaluate the navigation performance of the leader and follower node layers under GNSS-denied conditions, fully considering contingencies such as UWB outages and leader-node accuracy degradation. Results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly improves formation cooperative navigation accuracy and stability in GNSS-denied scenarios, confirming the feasibility and effectiveness of the framework in practical applications. Future work will include quadrotor cluster formation simulations to further validate the framework’s applicability under rotorcraft dynamic consistency, as well as exploring dynamic model-assisted navigation for heterogeneous UAV clusters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S. and X.Y.; methodology, F.S. and Q.Z.; software, F.S.; validation, F.S., X.Y. and R.Z.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, F.S.; supervision, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the fifth electronic research institute of MIIT under Grant 25Z05.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

Important Parameters and Abbreviations Used in This Article.

| P-GNSS | Pseudo-GNSS |

| IMM | Interacting Multiple Model |

| AOA | Angle of Attack |

| TAS | Airspeedometer |

| SINS | Strapdown Inertial Navigation System |

| BP | Back Propagation |

| RIEKF | Right Invariant EKF |

| SA | Sideslip Angle |

| Estimate value | |

| Average value |

References

- Gamagedara, K.; Lee, T.; Snyder, M. Quadrotor state estimation with IMU and delayed real-time kinematic GPS. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 2661–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Fu, Q.; Quan, Q.; Yang, K.; Cai, K.Y. Indoor multi-camera-based testbed for 3-D tracking and control of UAVs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 3139–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Han, Z.C.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Xie, L.B.; Yang, X.L.; Zhou, M. UAV detection and localization based on multi-dimensional signal features. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 5150–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wu, M. Dynamic electromagnetic positioning system for accurate close-range navigation of multirotor UAVs. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 20, 4459–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Li, F.; Liao, L.; Huang, M. Data fusion of UWB and IMU based on unscented Kalman filter for indoor localization of quadrotor UAV. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 64971–64981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haljakov, P.; Novk, A.; Ka, J. Monitoring GNSS signal quality at Zilina Airport. In New Trends in Civil Aviation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, A.; Jůn, F.; Škultéty, F.; Novák Sedláčková, A. Experiment demonstrating the possible impact of GNSS interference on instrument approach on RWY 06 LZZI. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 43, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, J.; Skog, I. Fifteen years of progress at zero velocity: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.S. A smoother for attitude and position estimation using inertial sensors with zero velocity intervals. IEEE Sens. J. 2011, 12, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, B. An improved heuristic drift elimination method for indoor pedestrian positioning. Sensors 2018, 18, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobahari, H.; Mohammadkarimi, H. Application of model aided inertial navigation for precise altimetry of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in ground proximity. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocoll, P.; Trommer, G.F. Quadrotor inertial navigation aided by a vehicle dynamics model with in-flight parameter estimation. In Proceedings of the 27th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2014), Tampa, FL, USA, 8–12 September 2014; pp. 1784–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, N.Y.; Choi, I.H.; Song, G.; Youn, W. Three-dimensional dynamic-model-aided navigation of multirotor unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 170715–170732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaghani, M.; Skaloud, J. VDM-based UAV attitude determination in absence of IMU data. In Proceedings of the 2018 European Navigation Conference (ENC), Gothenburg, Sweden, 14–17 May 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Koifman, M.; Bar-Itzhack, I.Y. Inertial navigation system aided by aircraft dynamics. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2002, 7, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkarimi, H.; Nobahari, H. A model aided inertial navigation system for automatic landing of unmanned aerial vehicles. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 2018, 65, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Song, F.; Tang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, Q. GNSS-INS-dynamic fusion with robustness to outliers based on external force state estimation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 015113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamandi, M.; Tognon, M.; Franchi, A. Direct acceleration feedback control of quadrotor aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5335–5341. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A.; Zennaro, M.; Howell, A.; Sengupta, R.; Hedrick, J.K. An overview of emerging results in cooperative UAV control. In Proceedings of the 2004 43rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37601), Nassau, Bahamas, 14–17 December 2004; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 602–607. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Strader, J.; Gu, Y.; Hypes, A.; Canciani, A.; Brink, K. Cooperative UAV navigation using inter-vehicle ranging and magnetic anomaly measurements. In Proceedings of the 2018 AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2018; p. 1595. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Lai, J.; Chen, S. Cooperative Location Method for Leader-Follower UAV Formation Based on Follower UAV’s Moving Vector. Sensors 2022, 22, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Shi, Q.; El Kamel, A. Multi-Agent Navigation Based on PHD and CPHD Filters. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 34999–35007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmozdi, A.; Hashemi, M.; Salarieh, H.; Alasty, A. Implementation of translational motion dynamics for INS data fusion in DVL outage in underwater navigation. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 6652–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimuri, G.; Matusiak, J.; Mikkola, T.; Kujala, P.; Hirdaris, S. A 6-DoF maneuvering model for the rapid estimation of hydrodynamic actions in deep and shallow waters. Ocean Eng. 2020, 218, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijjahalli, S.; Sabatini, R. A high-integrity and low-cost navigation system for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 22, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.B. Multiple IMU integration for vehicular navigation. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2009), Savannah, GA, USA, 22–25 September 2009; pp. 1828–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, P.; Lai, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.H.; Zhang, Q. A thrust model aided fault diagnosis method for the altitude estimation of a quadrotor. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 54, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q. A review of small UAV navigation system based on multisource sensor fusion. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 18926–18948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, Q. Semi-aerodynamic model-aided invariant Kalman filtering for UAV full-state estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 25920–25939. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, Y.; Hou, F.; Wu, J. Review on millimeter-wave radar and camera fusion technology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, B.; Luo, B. MGLNN: Semi-supervised learning via multiple graph cooperative learning neural networks. Neural Netw. 2022, 153, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.T.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Depth estimation from monocular images and sparse radar data. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 10233–10240. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, N.; Challita, G.; Mousset, S.; Bensrhair, A.; Ramaswamy, S. Collaborative positioning and embedded multi-sensors fusion cooperation in advanced driver assistance system. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 29, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Zhao, L. Distributed Elastic Fusion Navigation Method for Vehicle-Borne GNSS/SINS/Odometer. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2024, 53, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, S.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, K.; Feng, Z. Fusing mmWave radar with camera for 3-D detection in autonomous driving. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 20408–20421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, W. An optimal adaptive Kalman filter. J. Geod. 2006, 80, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Meng, F.; Xu, X.; Chu, W.; Wu, Z. Intelligent Multi-Source Autonomous Navigation Method Based on Vehicle Dynamics Features. J. Astronaut. 2024, 45, 550–559. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Z.; Meng, F.; Xu, X.; Wu, S. Research on dependability of multi-source autonomous navigation system. Navigat. Control 2023, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuonzo, D.; Buonanno, A.; D’Urso, M.; Palmieri, F.A. Distributed classification of multiple moving targets with binary wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Information Fusion, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–8 July 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Wang, G.; Luo, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Yu, Z. Multi-source information fusion based on rough set theory: A review. Inf. Fusion 2021, 68, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euston, M.; Coote, P.; Mahony, R.; Kim, J.; Hamel, T. A complementary filter for attitude estimation of a fixed-wing UAV. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Nebula, F.; Morani, G. Failure-proof algorithm for angle of attack estimation. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2023, 36, 04022118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, L. A performance compensation method for GPS/INS integrated navigation system based on CNN–LSTM during GPS outages. Measurement 2022, 188, 110516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, Q. Semi-Aerodynamic Model Aided Invariant Kalman Filtering for UAV Full-State Estimation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.01844. [Google Scholar]

- Song, F.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Ye, X. Double-Stage Filtering Fusion Navigation Algorithm Based on Multisource Optimal Selection. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 24675–24692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Ye, X. RIEKF-based resilient interactive fusion algorithm for cooperative navigation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 076301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Hsu, L.T. Resilient Interactive Sensor-Independent-Update Fusion Navigation Method. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16433–16447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhu, X.; Song, F.; Huang, D.; He, Z. Multisource Interactive Resilient Fusion Algorithm Based on RIEKF. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 24634–24648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.