Abstract

Dunhuang posthumous paper are a huge treasure trove of human civilization, among which the Dunhuang posthumous paper in the Wei-Jin period provides important data for the study of the development of calligraphy’s history. From the perspective of the philosophy of information, the developmental process of a calligraphic style can be interpreted as a holographic relationship. It is not only the hologram of calligraphy art, but also the hologram of a calligraphy aesthetic style, which is also the expression of Chinese culture. This attaches importance to information thinking in calligraphy art. According to the analysis of the stylistic use and aesthetic style of Dunhuang suicide note calligraphy in the Wei-Jin period, the significance of calligraphy can be revealed in its differences and uncertainties.

1. Introduction

In this information age, the emergence and development of the philosophy of information has derived a new information thinking, which enables calligraphy to have a new means of interpretation and direction of development, causing this “ancient” art to glow with a new vitality. Calligraphic art is the most concise materialized form of Chinese traditional culture. The earliest appearance of calligraphy, oracle bones, is the divination of ancient ancestors using animal bones, which is regarded as the mark of heaven transmitting information. The origin of calligraphy is related to information. This is consistent with Pro. Yang Weiguo’s view that “Chinese culture attaches importance to information thinking”.

According to the philosophy of information, serial relation holography means that everything maps and defines information on its own history, present situation and future. This series of holography is reflected in the historical development of Chinese calligraphy.

2. The Historical Causes of Dunhuang Posthumous Paper Calligraphy in the Wei-Jin Period

Buddhism originated from India and was introduced into China during the Western Han Dynasty. In the Wei-Jin period, it was widespread and became the “state religion” for a time [1]. Buddhism in the Han Dynasty opened up a key road of cultural and economic exchanges between China and the West, mainly through the Silk Road and economic exchanges. Northwest China became the first point of contact with western Buddhism and its introduction to the Central Plains, forming an early Buddhist gathering and exchange place in Dunhuang area.

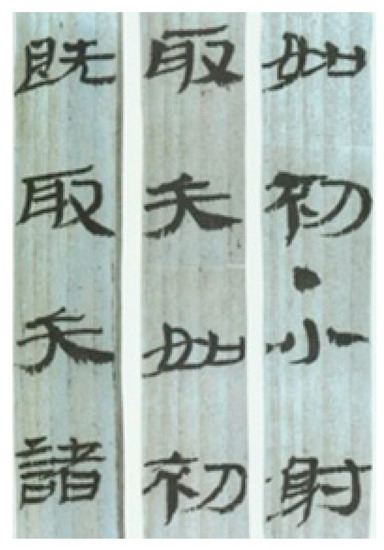

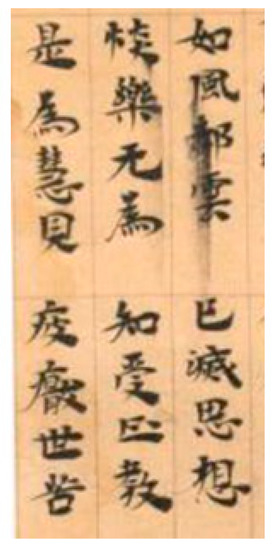

In the Dunhuang posthumous papers, there is a high number of calligraphic works from the Wei-Jin period. From these calligraphic works, we can clearly see that this period of an official script calligraphic style is in a period of transition to a regular script. Bamboo slips from the Han dynasty are shown (Figure 1 Wuwei bamboo slips) and compared to the calligraphy style of the period (Figure 2 The Dhammapada), the similarities lie in the inheritance of history, reflected in the overall layout of chapters and characters, and there are differences between them because of the different styles of The Times.

Figure 1.

Wuwei bamboo slips.

Figure 2.

The Dhammapada.

The faith worships of Buddhism forms the psychological basis of the essence of writing sutra. This mental foundation allows the believer to write with a serious attitude and a devout conviction. Therefore, the aesthetic orientation is plain and forceful. In the early period of copying classics, the brushstroke style of bamboo slips was followed, which gave the Dunhuang handwritten notes of this period their ancient meaning. This led to the preservation of the li script of the Han Dynasty in the process of the evolution of calligraphy, forming a vertical historical holography. The influence of Buddhist thought on the calligraphy at that time was a horizontal hologram [2].

3. A series of Holograms of the Calligraphy Skills of Dunhuang Posthumous Papers in the Wei-Jin Period

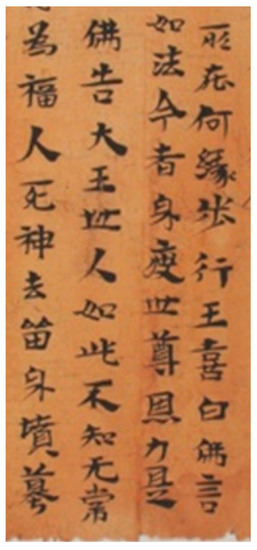

The Dunhuang posthumous papers are mainly regular script volumes. The authors of the Dunhuang posthumous papers typically chose a regular script when copying Buddhist sutras. The existence of the scribe style is the most distinctive feature of Dunhuang posthumous papers; that is, the historical relationship of the pen in the works of Dunhuang posthumous papers in the Wei-Jin period. The process of cursive script with official script gradually evolved into regular script is holographic performance. The fading of the meaning of official script is the concrete performance of the historical holography. The formation of regular script is holographic performance. In the same period, the performance of different styles of calligraphy is the complementary and different performance of horizontal holography. Figure 3 “Pi-Yu Scripture” is a Dunhuang sutra written in the Eastern Jin Dynasty (359 AD), and collected by Japan’s Nakamura Buji. It has the characteristics of an early Li script. The sharp pen is exposed, and the main pen is pressed heavily at the end to highlight the weight of the main pen. The character potential corresponds to the horizontal and vertical trend, which is obviously different from the horizontal trend of the li script.

Figure 3.

Pi-Yu Scripture.

In the mature period of the transformation of Dunhuang classic script in the Wei-Jin period, the works were mainly developed in the vertical direction and tended to be of a square shape, with a heavy finish and obvious scribe meaning. This was obviously different from the official script of the previous dynasties, and the development of calligraphy in this period changed their style of writing from a naive and simple script to a mature script. This is a kind of aesthetic style of the present era.

4. A Series of Holograms of the Aesthetic Style of Calligraphy in the Wei-Jin Period Dunhuang Posthumous Paper

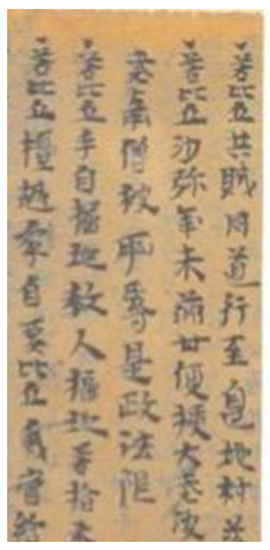

The plain aesthetic style is mainly inherited from the previous style of writing, which manifested as the holography of historical relations in the series of relation holography. The aesthetic features of this kind of brush are pointed into the brush, gradually increasing from thin to thick, with a brush posture of a thin head and thick tail. Most of them have turn over in official script (Figure 4: Ten Chants of Bhikkhu Precepts). These features are inherited from the plain aesthetics of the official script, which is reflected in the holography of historical relations. As a horizontal Dunhuang posthumous paper, it is listed as the aesthetic orientation of the same era as other styles.

Figure 4.

Ten Chants of Bhikkhu Precepts.

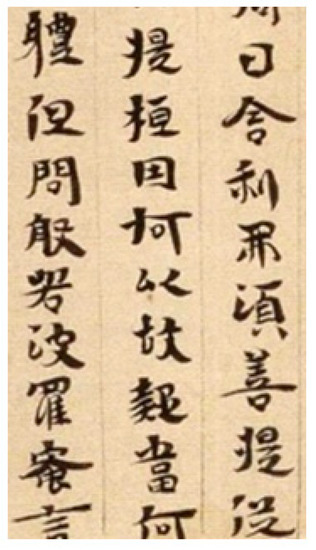

Jinjian’s aesthetic style is mainly the innovation of calligraphic style and the absorption of the new aesthetic of The Times, shown in the expression of the incompleteness of holography in the holographic relationship. There is only a slight hint of the official script, or there is a round brush or a peak on the state, showing the ancient meaning of the lingering charm of the official script. (Figure 5: Great Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom). The explicit bending of wave bars, the lifting and pressing of lines and the opening of glyphs are the changes produced in the natural writing. This evolution also led to the emergence of the later calligraphy style. In the series of relation holography, this manifested as the holography of future relations, which created the future writing style.

Figure 5.

Great Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom.

5. Inheritance Value of Dunhuang Posthumous Paper in Wei-Jin Period

The Wei-Jin Period followed the calligraphic thoughts of the two Han Dynasties, from the height of philosophy and aesthetics to the macro-perspective of “brushwork”, and an in-depth and meticulous discussion of the characteristics of brushwork, formation, dot painting shape. The five styles of calligraphy came into being, as well as calligraphers had a sense of artistic consciousness of the calligraphic aesthetic in Wei-Jin Period. This kind of consciousness of art is the result of the accumulation of artistic perceptions under the action of holography. In this period, the character was in full bloom, and the spirit and temperament of scholars were evaluated by the concept of “character”, which gradually began to influence the field of evaluating books as an aesthetic concept.

Style or taste is the whole embodiment of a person’s aesthetic taste [3]. It has certain social and historical implications for beauty and aesthetic feeling, especially due to the role of Buddhist religious consciousness. People’s aesthetic needs for sutra writings and their respectful and cautious attitude in copying Buddhist sutras are important reasons for the neat and dignified style of writing sutras [4]. Regarding the influence of Buddhist thoughts on the aesthetics of calligraphy, the writing style of Dunhuang posthumous papers in the Wei-Jin period had begun to show the influence of Buddhist thoughts on aesthetics. On the basis of metaphysical ontology, this paper combines “the agreement between god and things” with “no doubt, no change, no change” to form the middle-way consciousness, which is in line with the concept of “qian Qi Qi”. This is the holographic expression of calligraphy aesthetic under the influence of Buddhist thought.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, P.W.; writing—translation, revision and editing, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project of Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province in 2020: Research on Ontology of Philosophy of Information, grant number 2020C004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Y. Calligraphy and Culture in the Six Dynasties; Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2002; Volume 12, p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. Holographic Thinking of Social Culture from the Perspective of Lost Book Compilation. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L. Aesthetic Principle; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2009; Volume 161. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Q. The Study on the Calligraphy of Transcribing Buddhism Scriptures of Dunhuang in the Northern Wei Dynasty; Suzhou University: Suzhou, China, 2002; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).