Abstract

Freshwater resources are on the verge of depletion due to the rapid increase in population, lifestyle changes, and especially during climate change in Iraq. Therefore, treating domestic wastewater correctly will significantly contribute to keeping the balance of water purity and its usage. To fulfil this, the Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine (SPeARTM) program, which leverages Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis with operational sustainability indicators, is used to compare the relative sustainability performance of the novel Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor by visualising the results of the degree of its sustainability compared to the Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor and the conventional Sequencing Batch Reactor system. Although selecting the most sustainable treatment depends on specific treatment goals, available resources, site conditions, and stakeholder preferences, this study considers the equal weighting of sustainability assessment across environmental, social, and economic indices to inform sustainable decision making. The results show that integrating both conventional treatment plants into the novel modified treatment plant demonstrates a comparatively more balanced and stable sustainability performance under the assessed operational conditions. As at a design capacity of 100 m3·day−1, the MSBR achieved a higher organic and nutrient removal efficiencies relative to the conventional SBR and MBBR systems while operating at an intermediate energy demand (187.7 kWh·day−1) compared with the SBR (121.7 kWh·day−1) and the MBBR (211.8 kWh·day−1). Thus, it can compensate for the weaknesses and combines the strengths of the sustainability indices of the two systems, which supports the Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor as a comparatively favourable option for wastewater treatment within the assessed sustainability framework.

1. Introduction

Water management, particularly wastewater treatment, has increasingly emerged as a vital and pressing priority in contemporary society. It is of utmost importance that human activities do not disrupt essential ecological processes nor inflict any significant harm on human health and well-being. The environmental impact resulting from water pollution is profoundly substantial, leading to severe adverse effects on the overall quality of life for communities that are grappling with insufficiently purified and low-quality water resources [1].

In this critical context, the rational and judicious use of water resources, along with their sustainable management, is undeniably pivotal and imperative for fostering a healthy environment and society [2]. Conversely, selecting the most suitable and effective wastewater treatment technique for achieving robust, sustainable management is a decision of immense importance that significantly influences both environmental protection and broader conservation efforts and initiatives [3]. Several factors and concerns may influence the decision-making process for selecting the optimal wastewater treatment technique, as it has a long life cycle and requires analysis that encompasses various sustainability criteria [4]. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) proves its utility in comprehensive evaluations, and it can serve as a solution to help stakeholders choose the most sustainable wastewater treatment technology, making trade-offs between economic, social, and environmental aspects [5].

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), and PROMETHEE are widely applied in wastewater process selection and optimisation, particularly when ranking alternatives based on technical and economic performance criteria. These methods are effective when clear stakeholder priorities or hierarchical weighting structures are defined. However, their application often focuses on numerical ranking outcomes with limited emphasis on communicating trade-offs across environmental, economic, and social dimensions simultaneously.

In this study, the Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine (SPeARTM) framework was selected because it is specifically designed for integrated sustainability assessment and visualisation across multiple dimensions. Although originally developed for infrastructure appraisal, SPeARTM has been increasingly applied in environmental and engineering contexts where comparative sustainability performance and transparent decision support are required. Its radial visual representation facilitates the interpretation of MCDA results by non-specialist stakeholders and supports a comparative evaluation of process technologies under equal weighting conditions. These features make SPeARTM suitable for the present study, which aims to assess relative sustainability trends among wastewater treatment systems rather than to derive a single optimal ranking based on narrowly defined criteria.

To apply the MCDA Logical Framework, the objective weights were first given to the sustainability indices (SI) (3: Excellent, 2: Good, 1: Adequate, 0: Neutral/Moderate, and −1: Poor). [6] reported that the weights used in the MCDA results vary depending on the stakeholders’ perceptions or types of wastewater collection systems. Thus, this can lead to different profitability, affordability, equity, social, and environmental impact results. Therefore, equal weighting was chosen to apply, so there would not be any preference among the SI (for example, there is no preference between the cost and effluent water quality). The given weight for each SI for this study is derived from the evaluation of the data for each indicator collected from [7], which is an active company for wastewater treatment in Erbil, Iraq. In addition, the effluent quality is tested from July 2024 to June 2025 for the three systems [8]. Regarding the results from the MCDA to be visualised, the SPeARTM program is used, so that the selection of the most sustainable option becomes easier.

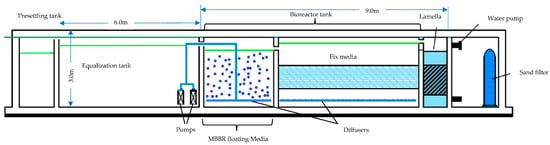

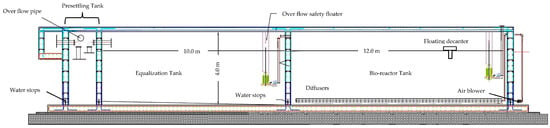

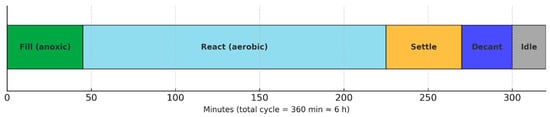

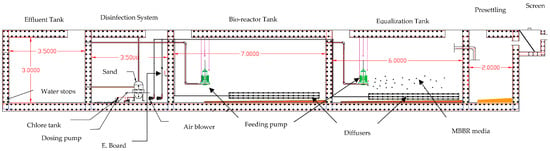

In this study, the SBR is modified by integrating the MBBR’s robust biomass retention (Figure 1) and the SBR’s operational flexibility (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This SBR is modified (MSBR) by incorporating an upstream equalisation tank with the high-density polyethene (HDPE) carriers to enhance the stability and buffering with the addition of diffusers to provide the needed dissolved oxygen and keep the media floating at the same time, unlike the previous modifications, which were made in the same SBR basin as exhibited in Figure 4. Here, the simplicity of cyclic operation is preserved as the SBR basin is unchanged, while the floating media with the optimal amount of dissolved oxygen enhances the partial organic removal and flow equalisation before the influent enters the main SBR basin: all that without a big increase in energy consumption. However, this novel design is not just to propose a new configuration but also to assess its performance compared to conventional SBRs and MBBRs based on effluent quality.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR) with MBBR media, fixed media, and diffusers.

Figure 2.

Schematic of a Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) showing decanter, diffusers, and a blower.

Figure 3.

Six-hour operational cycle of the conventional SBR unit, including phase durations.

Figure 4.

Schematic of a Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor (MSBR) comprising an equalisation tank with media and diffusers, and an SBR tank.

Due to the SBR’s ease of use, effectiveness, and affordability, it is frequently used to treat wastewater in homes [9]. Therefore, to improve energy performance, biomass stability, and nutrient removal, the system’s structure has been modified more recently.

In order to treat low-strength residential wastewater, ref. [10] integrated Aerobic Granular Sludge (AGS) into the SBR system’s operations. In this system, intermittent aeration was administered under an anaerobic–aerobic–anoxic regime within a four-hour SBR cycle. In addition to encouraging the formation of dense, well-settling granules (about 1.8 mm in size), this alteration practically eradicated phosphorus and removed about 90% of the chemical oxygen demand (COD) and 80% of the ammoniacal nitrogen (AN). Furthermore, ref. [11] examined a developed step-feed cycle configuration (SSBR) by contrasting it with a traditional SBR under comparable circumstances. They found that the SSBR maintained the efficiency of phosphorus reduction while removing ammonium (NH4+–N) and total nitrogen (TN) significantly even with lower aeration requirements that lead to lower energy demand. Effluent Quality Improvement in Sequencing Batch Reactor-based Wastewater Treatment Processes Using Advanced Control Strategies (2024) is the publication that contains this study. Additionally, intermittent aeration was investigated as a way to optimise nitrogen removal by changing the dynamics of the microbial community. Continuous-flow aerobic granular sludge (CF-AGS) systems were studied by [12] under various aeration schedules, ranging from three to twelve hours per day, in order to achieve this. They discovered that the microbial groups were encouraged, which improved the granule’s settleability. As a result, this regime has a very balanced effect that may enhance the removal of organic matter and denitrification while maintaining nitrification. Their findings are consistent with the research of [13], who modified the operational cycle by adding the anoxic phase, resulting in a nitrogen removal efficiency of about 80%. Nevertheless, ref. [13] also employed biocarriers such as BioChip 25 at concentrations of 10–20%, which increased the removal by about 20%. To achieve the highest oxygenation efficiency and reduce costs, a static decanter and continuous chamber filling are two more changes. Due to its special design that makes the sedimentation stable under any variations, the Grundfos sequencing batch reactor technology (SBR-GT), created by [14], does not require the sludge to be circulated. In addition to these modifications, the MBBR and SBR were hybridised by [15] and found that the Sequencing Batch Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactors (SBMBBR) could effectively treat wastewater containing cefixime (CFX), achieving a high removal of organic matter and nitrogen at moderate concentrations (≈45 mg/L). At higher CFX levels, microbial activity and treatment efficiency declined, while Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) confirmed CFX breakdown into smaller intermediates and final mineralisation.

Hybrid wastewater treatment systems that combine suspended and attached growth processes, such as Integrated Fixed-Film Activated Sludge (IFAS) and Sequencing Batch Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactors (SBMBBRs), have been widely studied for improving biomass retention, nutrient removal, and resistance to hydraulic and organic load fluctuations [15,16,17]. In most reported hybrid SBR configurations, biofilm carriers are incorporated directly into the main bioreactor, allowing attached and suspended biomass to coexist within the same treatment volume. While these systems often enhance nitrogen removal and process stability, they may also increase operational complexity, aeration demand, and maintenance requirements [11,13].

In contrast, the Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor (MSBR) investigated in this study adopts a different hybridisation approach by placing biofilm carriers within an upstream equalisation tank while retaining an unmodified downstream SBR basin. This configuration enables influent buffering, partial organic removal (Table 1), and biomass stabilisation before batch treatment, thereby reducing load variability entering the SBR without disrupting its cyclic operation or substantially increasing energy demand. As such, the MSBR captures key advantages of hybrid systems while preserving the operational simplicity and flexibility of conventional SBRs.

Table 1.

Illustrates the systems’ efficiency in removing the organic, nutrient, and physicochemical parameters from July 2024 to June 2025 [8].

Despite the widespread application of SBRs and MBBRs, each system exhibits inherent limitations that restrict overall sustainability. Conventional SBRs rely on cyclic operation and suspended biomass, making their performance sensitive to influent flow and load fluctuations and often resulting in elevated sludge production, whereas MBBRs depend on continuous aeration and additional carrier media, leading to increased energy demand and operational costs [16,17,18]. Existing studies have largely evaluated these systems as standalone technologies with limited attention given to hybrid or modified configurations that simultaneously address hydraulic variability, biomass retention, energy efficiency, and sludge minimisation within a single integrated process [19].

Consequently, a clear research gap exists in the development and systematic evaluation of modified SBR configurations that incorporate upstream buffering and enhanced biomass control while preserving the operational simplicity of conventional SBRs. The MSBR proposed in this study was designed to address this gap by integrating an equalisation stage with the SBR process to improve process stability and sustainability under real operational conditions. However, the environmental and operational implications of such configurations, particularly when assessed using combined life cycle assessment and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis frameworks, remain insufficiently explored in the existing literature.

The primary aim of this study is to support the comparative positioning of the MSBR in terms of treatment efficiency and sustainability performance in modern contexts. Furthermore, it aims to propose a SPeARTM program depending on a multi-criteria approach that will assist in tackling the complex selection problem associated with wastewater treatment methods, particularly in the context of newly developed industrial regions where the demand for efficient water management solutions is increasingly high. Thus, it can assist municipal and regional decision-makers in selecting suitable wastewater treatment options. Accordingly, the novelty of this study lies in evaluating the treatment efficiency and sustainability performance of an SBR system incorporating floating biofilm media within the upstream equalisation tank rather than in the equalisation concept itself.

2. Materials and Methods

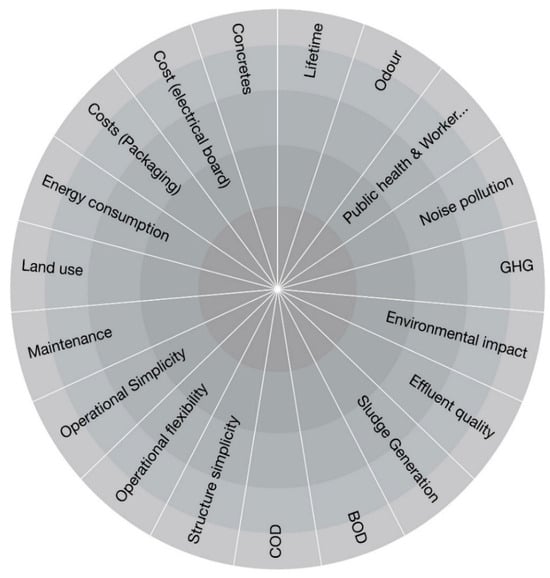

This paper employs Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) techniques to compare the degree of sustainability of the novel MSBR compared to Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR) and Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) systems. Then, it visualises the Sustainability Indices (SIs) using the SPeARTM software program to ease decision making, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Selected SI for the comparison in the SPeARTM software program.

2.1. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Framework

The life cycle component of this study represents a comparative, gate-to-gate operational assessment rather than a full cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment. To complement the multi-criteria sustainability evaluation, a simplified, energy-based operational life cycle assessment was applied in accordance with [20,21] to assess the relative operational environmental performance of the systems under identical treatment conditions.

The functional unit was defined as the treatment of 1 m3 of wastewater to meet applicable discharge standards, which was based on a uniform design capacity of 100 m3·day−1 for all systems. The system boundary was limited to a gate-to-gate operational scope, focusing on electricity consumption associated with aeration, pumping, mixing, and filtration. Construction, decommissioning, and end-of-life stages were excluded due to the absence of detailed material inventories, while chemical consumption was omitted from the quantitative assessment because identical chemicals and dosing regimes were applied across all systems.

Life cycle inventory (LCI) data were derived from measured equipment-level electricity consumption, which was aggregated over a 24 h operating period and normalised to the functional unit. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were estimated by converting electricity demand into carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2-eq) using a literature-based emission factor of 0.64–0.95 kg CO2 per kWh, which reflects the variability of electricity generation mixes in fossil-dominated grids. This energy-based characterisation is widely recognised as an appropriate proxy for operational environmental impacts in biological wastewater treatment systems, where electricity use represents the dominant contribution to life cycle emissions [19].

The resulting LCA outcomes were subsequently integrated into the environmental sustainability indicators within the MCDA framework, ensuring methodological consistency between quantitative operational impacts and the broader sustainability assessment. Accordingly, the LCA applied in this study represents a comparative, operational (gate-to-gate) life cycle assessment, focusing on energy-driven environmental impacts rather than a full cradle-to-grave analysis.

2.2. MCDA Scoring Criteria, Indicator Selection, and Weighting Rationale

The multi-criteria decision analysis in this study was implemented using the Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine (SPeARTM) framework. SPeARTM is an indicator-based MCDA method in which sustainability performance is assessed through a predefined set of environmental, economic, and social indicators. Each indicator is assigned a qualitative score (e.g., −1, 0, +1) based on measured operational data or justified relative comparisons, and then it is normalised to a common scale to ensure comparability. Indicator scores are subsequently aggregated within each sustainability dimension using equal weighting, and the overall performance is interpreted comparatively through graphical and numerical outputs. This approach prioritises transparency and decision support over mathematical optimisation or outranking, making it suitable for an exploratory sustainability assessment of wastewater treatment technologies.

To compare the sustainability performance of the conventional SBR, the MBBR, and the proposed MSBR, an MCDA framework was applied in conjunction with the SPeARTM sustainability assessment tool. A total of 19 key Sustainability Indicators (SIs) were defined to capture environmental, economic, and social dimensions relevant to wastewater treatment performance under real operating conditions.

The environmental dimension comprised six indicators, including overall environmental impact, greenhouse gas emissions, effluent quality (with particular emphasis on total nitrogen (TN) and ammonium–nitrogen (NH4+–N)), organic matter removal efficiency (BOD and COD), and sludge management. The economic dimension included nine indicators: costs related to packaging and electrical boards, structural simplicity, operational flexibility, operational simplicity, maintenance requirements, land use, energy consumption, and civil works. In addition, four social acceptability indicators were considered, namely odour, public health and worker safety, noise pollution, and system lifetime.

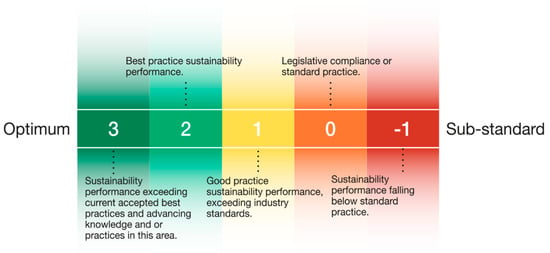

Each sustainability indicator was evaluated using a discrete ordinal scoring scale ranging from −1 (worst performance) to +3 (best performance), which was consistent with the scoring structure embedded within the SPeARTM framework. This scale allows negative scores to represent unsustainable or unfavourable performance, while higher positive scores indicate progressively improved sustainability outcomes. Scores were assigned based on the relative performance of each treatment technology under identical operational conditions rather than absolute benchmark values, as illustrated in Figure 6. In addition to the colour coding, the SPeARTM diagrams reflect the underlying MCDA scores ranging from −1 to +3, such that differences in colour intensity and radial extent indicate relative differences in sustainability magnitude rather than absolute numerical values.

Figure 6.

Colour codes used in the SPeARTM program, depending on the given weights to SI in the MCDA.

The explicit performance criteria and thresholds were defined before scoring; for quantitative indicators, such as energy consumption, sludge production, land requirement, and cost-related metrics, scores were assigned directly based on measured or calculated data with lower environmental or resource burdens receiving higher positive scores. For qualitative and semi-quantitative indicators, including operational simplicity, maintenance, odour, and safety, scoring was informed by documented operational characteristics, engineering judgement, and consistency with established performance trends reported for comparable wastewater treatment technologies.

The data underpinning the MCDA were obtained primarily from [7], which operates industrial–municipal wastewater treatment facilities in Erbil, Iraq. These operational records provided a robust basis for evaluating energy use, sludge handling, costs, and system operation for all three technologies. The effluent quality indicator was supported by laboratory analyses of wastewater samples collected directly from the treatment plants between July 2024 and June 2025 with all samples analysed within 24 h of collection [8]. This combination of full-scale operational data and site-specific analytical measurements ensured that the assigned scores were grounded in measured performance rather than theoretical assumptions.

To avoid bias toward any single sustainability dimension, equal weighting was applied to all sustainability indicators across the three treatment systems. This decision reflects the exploratory and comparative nature of the study and is consistent with MCDA practice, where no clear stakeholder-driven prioritisation is predefined. The assigned weights and their corresponding rationales are summarised in Table 2. Following scoring and weighting, the resulting MCDA values were imported into the SPeARTM software, which visualises sustainability performance using a colour-coded scheme corresponding to the −1 to +3 scoring range, enabling a clear comparison among SBR, MBBR, and MSBR configurations.

2.3. Linkage Between Quantitative Performance Data and MCDA Scores

To ensure internal coherence between the quantitative performance data and the MCDA outcomes, the numerical scores assigned to sustainability indicators in Table 2 were directly informed by the measured values reported in Table 3. For quantitative indicators such as energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, sludge generation, and land requirement, MCDA scores were assigned based on relative ranking among the evaluated systems rather than the proportional scaling of absolute values.

Specifically, the system exhibiting the most favourable quantitative performance for a given indicator received the highest score (+3), while the intermediate and least-performing systems were assigned progressively lower scores (+1, 0, or −1), depending on the magnitude and practical significance of the observed differences. This relative-ranking approach avoids artificial precision and reflects engineering-relevant distinctions rather than minor numerical variations. All scoring decisions were cross-checked against the underlying quantitative data to ensure consistency and internal validity of the comparative assessment.

2.4. Effluent Sampling and Analytical Procedures

Influent and effluent samples were collected monthly from the SBR, MBBR, and MSBR units in Erbil, Iraq, from July 2024 to June 2025. Samples were analysed within 24 h of collection with storage at 4 °C to minimise physicochemical changes. Key parameters, including TN, NH4+–N, TP, COD, and turbidity, were measured with a Lianhua multiparameter analyser (model LH-MUP230 V11S) (Figure 7), and BOD5 was determined with an OxiTop® respirometric system. TSS and SO4 were tested using standard methods [22]. In situ measurements were made for EC, pH, and DO. Quality control involved routine calibration, blank checks, and duplicate analyses to ensure reliability.

Figure 7.

Lianhua multiparameter analyser (model LH-MUP230 V11S).

Table 2.

Illustrates the weighting for MCDA and rationale for the sustainability indicators for the comparison among the systems (MBBR, SBR, and MSBR).

Table 2.

Illustrates the weighting for MCDA and rationale for the sustainability indicators for the comparison among the systems (MBBR, SBR, and MSBR).

| No | Criteria | SI | MCDA | Rational Reasons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBBR | SBR | MSBR | ||||

| 1 | Environmental | Greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) | −1 | 1 | 0 | This is directly correlated with the energy consumption, as shown in Table 3. Thus, the SBR has the least gas emission. About 0.64–0.95 kg CO2 of GHGs is emitted from 1 kW of energy consumption [23]. |

| 2 | Environmental impact | 2 | 1 | 2 | Although the MBBR uses the most energy, it has lower environmental impacts as it is smaller; thus, it destroys fewer environmental habitats. Additionally, it has a high-quality effluent [24]. Regarding the MSBR, it needs smaller basins compared to the SBR, and the effluent quality is higher compared to the MBBR. | |

| 3 | Effluent quality | 2 | 1 | 3 | The MSBR achieved COD and BOD removals above 92%, total nitrogen removal and ammonia nitrogen exceeding 91% and 94%, respectively, and phosphorus elimination of 96%, consistently outperforming both the MBBR (COD/BOD~88%, TN~80%, NH4+–N~94% P~79%) and the SBR (COD/BOD~83%, TN~86%, NH4+–N~89.42, P~90%). | |

| 4 | Sludge generation | 2 | 1 | 3 | Over 6 months for treating 100 m3/day of wastewater (for the same source of wastewater) with the same solid retention time (SRT), the SBR, which features submersible sludge pumps, generates 7 to 8 m3 of sludge, because the biomass is mostly suspended and not subjected to endogenous decay; however, the MBBR generates 4 to 5 m3 due to biofilm effects that lead to higher cell decay. Regarding the MSBR, it creates about 3 to 4 m3. Since this system allows more biomass decay through the attached and the suspended growth, it generates the least sludge. These data are compatible with [25]. | |

| 5 | BOD | 2 | 1 | 3 | The MSBR achieved the most effective reduction of organic matter with BOD and COD removal efficiencies of 92.4% and 92.18%, respectively. In contrast, the MBBR attained 88.68% BOD and 88.48% COD removal, while the SBR exhibited the lowest performance, reaching 82.87% for BOD and 82.63% for COD. These findings confirm the superior pollutant removal capacity of the MSBR compared with the conventional treatment systems. | |

| 6 | COD | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 7 | Economical | Structure simplicity | 1 | 3 | 2 | The SBR has the fewest items, and it is one big basin, while the MBBR has the most items that are divided among three smaller basins. As the MSBR has the structure of the SBR with the floating media, its complexity is more than the SBR and less than the MBBR. |

| 8 | Operational flexibility | 1 | 2 | 2 | The MBBR has moderate (consistent) functioning, while the SBR is more flexible as the cycles can be changed to influence. The MSBR works the same as the SBR. | |

| 9 | Operational simplicity | 2 | 1 | 1 | The MBBR processes continuously; thus, it is simpler to operate. The MSBR works the same as the SBR. | |

| 10 | Maintenance (cleaning) | 0 | 2 | 1 | For the SBR, cleaning is simpler because there is not much equipment in the container, whereas the MBBR has the floating and fixed media, making it more difficult to clean. On the other hand, the MSBR has only the floating media. | |

| 11 | Land use | 2 | 0 | 1 | To treat 100 m3/day of wastewater, for the SBR, bigger equalisation basins are required for processing in batches, because water needs to stay in the system for 8 h, thus the basins should store 35 to 40 m3. However, the MBBR has a compact design, because biofilm carriers and the fixed media increase the surface area, so the water should stay for 3 to 4 h, hence 20 to 30 m3 basins are enough. But due to the Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids (MLSSs) in the MSBR, the requirement for land is less than that for the SBR. Thus, the water needs to stay for 6 h, and the basins need to store 25 to 35 m3. | |

| 12 | Energy consumption | 1 | 3 | 2 | The MBBR needs the most energy, while the SBR need the least, as it is shown in Table 3. | |

| 13 | Costs (packaging) | 0 | 2 | 1 | The MBBR has a higher initial investment cost (for treating 100 m3 of water; the SBR costs 60% of the MBBR, and the MSBR costs 75% of the MBBR). | |

| 14 | Cost (electrical board) | 0 | 2 | 2 | The SBR costs 60% of the MBBR’s board, and the MSBR costs about 65% of the MBBR (almost the same as the SBR). | |

| 15 | Civil works (concretes) | 2 | 0 | 1 | The MBBR needs 70% less concrete compared to the SBR, while it needs 85% less compared to the MSBR systems. | |

| 16 | Social | Odour | 2 | 1 | 2 | The MBBR can reduce odour emission without the need for further chemical or unit treatments if they are operated with the right operational control (thick biofilm, appropriate media surface area, fill fraction, and aeration), while in the SBR, during the non-aerated phase, the odorous compound is released. On the other hand, the MSBR is anticipated to produce less odour than the SBR but slightly more than the MBBR, because of the biofilm carriers that promote organic breakdown and process stability. |

| 17 | Public health and worker safety | 2 | 2 | 2 | They are all safe, but the odour from the SBR might cause a little discomfort. | |

| 18 | Noise pollution | 1 | 2 | 2 | The steady sound produced by ongoing aeration in the MBBR. But because of the intermittent periods, the noise is reduced in the SBR and MSBR. | |

| 19 | Lifetime | 1 | 2 | 2 | The SBR and MSBR will work properly up to 20 years, while the MBBR works up to 15 years. | |

The SBR has four cycles in 24 h. For each cycle, it takes 1 h for the water pump to put the water in the tank, and about 4 h are needed for the blower (it has one blower); then, the system turns off for 1 h, allowing the sludge to settle. Lastly, it takes 1 h for the water pump to remove the water. While the MBBR works continuously during the 24 h, this system needs two water pumps, one of which works at all times to put water into the tank, and two blowers, which also work in turns. On the other hand, the MSBR is a mix between the aforementioned systems, which has an MBBR media and a blower in the equalising tank, as in the MBBR, the blower that is in the equalising tank works for 3 h/1 cycle, while the other blower is in the secondary tank that works for the 4 h/1 cycle, but the same cycles and structure as the SBR. They all need a pumping dose and a sand filter to increase the purity of the water. Based on their structure and the working hours, the energy consumption is calculated as it is illustrated in the table below, depending on Zhinda, which is a profound and active company in Erbil, Iraq. Economic indicators represent relative, order-of-magnitude comparisons based on operational records and standard equipment configurations, and do not constitute a detailed techno-economic analysis (e.g., BoQ or NPV). Qualitative indicators were scored using an ordinal scale based on relative system characteristics and author consensus, as described in Section 2.3; alternative numeric coding would not affect the comparative MCDA outcome.

Table 3.

Energy consumption of SBR, MBBR, and MSBR systems.

Table 3.

Energy consumption of SBR, MBBR, and MSBR systems.

| No | Item | Energy Consumption per Item (kW/h) | SBR (kW/24 h) | MBBR (kW/24 h) | MSBR (kW/24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blowers | 5.5 | 1 (blower) × 5.5 × (4 h/1 cycle × 4 cycles/24 h) 1 × 5.5 × 4 × 4 = 88 | It has two blowers; they operate in bypass mode continuously for 24 h. 5.5 × 24 = 132 | This system has two blowers, which work as below: A. 1 blower × 5.5 × (4 h/1 cycle × 4 cycles) = 88 B. 1 × 5.5 × (3 h/1 cycle × 4 cycles) = 66 C. total = 88 + 66 = 154 |

| 2 | Water pump | 2.2 for SBR and MSBR 1.1 for MBBR as it works continuously | It has two pumps, each works for 4 h. The total h are 8 h. 8 × 2.2 = 17.6 | It has two pumps which work bypass for 24 h 24 × 1.1 = 26.4 | The same as SBR (17.6) |

| 3 | Dosing pump | 0.025 | 0.025 × 4 cycles = 0.1 | 0.025 × 24 h = 0.6 | 0.025 × 4 cycles = 0.1 |

| 4 | Sand filter | 4 for SBR and MSBR 2.2 for MBBR | 4 × 4 cycles = 16 | 2.2 × 24 h = 52.8 | 4 × 4 cycles = 16 |

| 5 | Total | 121.7 kW/24 h | 211.8 kW/24 h | 187.7 kW/24 h |

Energy consumption estimates are based on rated motor power and operational hours under consistent assumptions for comparative purposes, and they do not account for variable load operation, VFD control, oxygen transfer efficiency, or pump curve optimisation.

3. Results

3.1. Effluent Quality and Removal Performance

Over the monitoring period, the MSBR exhibited higher removal efficiencies for organic matter and nutrients compared with the conventional SBR and MBBR systems, as illustrated in Table 1. Mean COD and BOD5 removal efficiencies in the MSBR exceeded 92%, whereas the SBR and MBBR achieved approximately 83–88% removal. For nitrogen species, mean total nitrogen and ammonium removal efficiencies in the MSBR were above 91% and 94%, respectively, while lower and more variable values were observed in the reference systems [8]. These measured influent and effluent concentrations and corresponding removal efficiencies formed the quantitative basis for the effluent quality and environmental indicator scores applied in the MCDA framework.

3.2. MCDA Weighting and the Rational Reasons for MBBR, SBR, and MSBR Treatment Systems

The MCDA weighting approach and the rationale used to score the sustainability indicators for comparing the MBBR, SBR, and MSBR systems. To avoid bias toward any single sustainability dimension and to reflect the comparative nature of this study, equal weighting was applied across all indicators. Weights and scores were assigned based on measured operational data (e.g., energy consumption, land requirement, sludge generation, and effluent performance) and supported, where necessary, by documented process characteristics and engineering judgement for qualitative indicators (e.g., operational simplicity, maintenance, odour, noise, and safety). This transparent weighting and rationale structure ensures that differences among the three systems are interpreted as relative sustainability trends under identical operating conditions (Table 2).

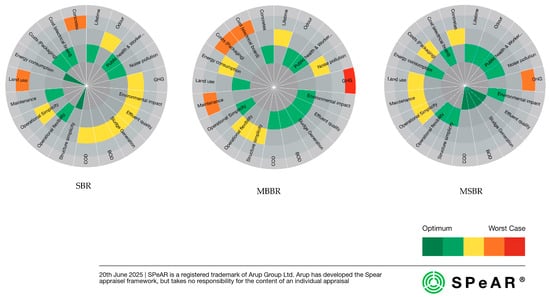

3.3. The SPeARTM Programs’ Outcomes for MBBR, SBR, and MSBR

Figure 8 summarises the SPeAR™ outputs for the SBR, MBBR, and MSBR under equal weighting across the 19 sustainability indicators. Overall, the MSBR exhibits the most balanced performance, with consistently favourable scores across environmental, economic, and social indicators, compared to the standalone systems. The SBR performs well in energy- and noise-related indicators due to intermittent operation, but is constrained by higher land demand and sludge generation, whereas the MBBR benefits from compactness and operational robustness but exhibits less favourable energy- and GHG-related performance due to continuous aeration and pumping.

Figure 8.

The outcomes from the SPeARTM program for MBBR, SBR, and MSBR systems.

4. Discussion

The discussion centres on a comparative sustainability assessment of a novel MSBR with two wastewater treatment technologies: the MBBR and the conventional SBR. The analysis utilises the SPeARTM framework in conjunction with MCDA to evaluate the technologies across 19 important metrics of environmental, economic, and social factors, as shown in Table 2. The visual representation employs radar charts (Figure 5), where green indicates optimal performance, yellow represents a middle ground, and orange and red suggest a worst-case scenario (Figure 6).

Table 2 provides a consolidated overview of the sustainability performance of the SBR, MBBR, and MSBR systems across environmental, economic, and social dimensions. The selected indicators were chosen to capture both regulatory-level outcomes and process-level characteristics commonly reported in wastewater treatment literature. Although certain indicators are interrelated, their inclusion serves different analytical purposes. For example, effluent quality represents an integrated compliance-based indicator reflecting the overall discharge performance, while BOD and COD specifically characterise biodegradable and total organic load removal, respectively, enabling a finer differentiation of treatment efficiency among the systems. Nitrogen removal performance, particularly total nitrogen, is addressed explicitly in the performance analysis and discussion as a key distinguishing factor; however, it was not included as a separate sustainability indicator to avoid any over-representation of nutrient removal within the MCDA structure. Together, the selected indicators provide a balanced and non-redundant basis for comparative sustainability assessment.

From a life cycle perspective, the sustainability differences observed among the treatment systems are primarily driven by operational energy demand and sludge generation, which represent the dominant contributors to environmental impact within the defined system boundary [19]. The conventional SBR exhibited the lowest energy-related greenhouse gas emissions due to its intermittent aeration strategy, whereas the MBBR showed the highest operational footprint as a result of continuous aeration and pumping requirements. The MSBR occupied an intermediate position, reflecting the additional energy input associated with enhanced process stability and upstream buffering.

However, this moderate increase in energy demand for the MSBR was accompanied by a substantial reduction in sludge production, which has important downstream implications that extend beyond the operational boundary considered in this study. Lower sludge volumes reduce the environmental burden associated with sludge handling, transport, and disposal, and therefore represent a compensatory sustainability benefit that is not fully captured by energy-based indicators alone. This trade-off highlights the importance of integrating life cycle thinking with multi-criteria decision analysis, as it allows environmental costs and benefits to be evaluated holistically rather than through isolated performance metrics.

The substantial land use requirements are probably a major topic of disagreement. SBR technology requires a lot more land than MBBR technology, which is a significant factor, especially in places where it is expensive or rare. Additionally, because the MBBR processes continuously rather than in batches as the SBR does, it is preferred for its operational simplicity. However, the MBBR requires a larger initial outlay of funds, but it eventually saves money by requiring less upkeep and maintenance (repairing items). Compared to the MBBR’s continuous aeration, the SBR’s intermittent operation minimises noise pollution, making it superior. In addition, the SBR is better when energy conservation is a top concern because of its intermittent aeration, which makes it more energy-efficient. Overall, because of the MBBR’s reliable performance, ease of use, and capacity to manage load fluctuations, contributing to less sludge production, the MBBR is regarded as appropriate for small installations and circumstances involving fluctuating influent. Despite requiring greater space and careful cycle management, the SBR stands out for its operational flexibility and cost effectiveness.

In addition to these sustainability considerations, the enhanced nitrogen-removal capability of the MSBR further demonstrates its technical advantage. The system consistently achieved strong reductions in total nitrogen and ammonia–nitrogen with removal rates exceeding 91% and 94%, respectively. These outcomes reflect the improved oxygen transfer, stable biofilm activity, and balanced reaction zones that encourage more efficient nitrification–denitrification sequences compared to the standalone MBBR and SBR units. When benchmarked against the MBBR (TN~80%, NH4+–N~94%) and the SBR (TN~86%, NH4+–N~89.42%), the MSBR shows clearer resilience in handling fluctuating nitrogen loads while maintaining performance stability. This consistent gain in nitrogen dynamics indicates that the hybrid configuration supports a more adaptive microbial community, enabling treatment plants to better meet strict nutrient-discharge requirements and limit eutrophication-related impacts.

To maximise the strengths, address the limitations, and minimise the drawbacks of SBR and MBBR treatment systems, the novel MSBR system integrates the batch operation and flexibility of the SBR with the biofilm-based treatment of MBBR. This hybrid system meets important sustainability objectives by combining the best features of the SBR (such as flexibility, low energy consumption and batch control) and the MBBR (for instance, robustness, modularity, and biofilm stability) (Figure 7).

The findings represent site-specific, comparative trends identified through MCDA and should not be interpreted as definitive causal conclusions.

5. Conclusions

The Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor (MSBR) emerged as the most balanced and sustainable option among the evaluated systems. By integrating the operational strengths of both the SBR and MBBR, the MSBR achieves high treatment efficiency while addressing key limitations of the individual technologies. It effectively reduces sludge production, odour, and land requirements, offering stable performance even under variable loading conditions. Although the MBBR provides excellent effluent quality and occupies less space, it is energy-intensive and requires more complex maintenance. Similarly, the SBR is simpler in structure and consumes less energy, but it produces larger volumes of sludge and generally has lower organic removal efficiency. Through hybridisation, the MSBR combines these advantages, uniting compactness, reliability, and environmental efficiency, making it a practical and sustainable choice for modern wastewater treatment, where resource optimisation and environmental performance are priorities.

The identification of the MSBR as a comparatively favourable sustainability option in this study is contingent upon the equal-weighting assumption applied across environmental, economic, and social indicators. Alternative weighting scenarios reflecting different stakeholder priorities could yield different rankings; for example, greater emphasis on cost-related criteria may favour the conventional SBR, whereas an increased weighting of operational stability and effluent performance may further support the MSBR. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as decision-support outcomes illustrating comparative sustainability trends rather than a universal prescription.

While the MSBR exhibited consistently favourable sustainability performance within this assessment, the conclusions should be interpreted in light of the comparative, site-specific nature of the analysis, inherent data uncertainties, and the structured subjectivity associated with MCDA-based scoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.A.M.; methodology, H.A.M.; software, H.A.M.; validation, H.A.M., B.A.O. and G.B.B.; formal analysis, H.A.M.; investigation, H.A.M.; resources, H.A.M.; data curation, H.A.M.; writing: original draft, H.A.M.; writing: review and editing, B.A.O. and G.B.B., who provided guidance and critical feedback throughout the development of the manuscript; visualisation, H.A.M.; supervision, B.A.O. and G.B.B.; project administration, H.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The article processing charge (APC) will be covered personally by the author as a self-funded PhD student.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The datasets generated and analysed during the research can be shared for academic and non-commercial purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. As this research received no external funding, the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| MSBR | Modified Sequencing Batch Reactor |

| MBBR | Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor |

| SBR | Sequencing Batch Reactor System |

| SI | Sustainability Indicators |

| SPeARTM | Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine program |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethene |

| AGS | Aerobic Granular Sludge |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| AN | Ammoniacal Nitrogen |

| SRT | Solid Retention Time |

| MLSS | Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids |

| SSBR | Step-Feed Cycle Sequencing Batch Reactor |

| CF-AGS | Continuous-Flow Aerobic Granular Sludge |

| SBR-GT | Grundfos Sequencing Batch Reactor Technology |

| SBMBBR | Sequencing Batch Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactors |

| CFX | Cefixime |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

References

- Hu, Y.; Cai, X.; Du, R.; Yang, Y.; Rong, C.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y.-Y. A Review on Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors for Enhanced Valorization of Urban Organic Wastes: Achievements, Limitations, Energy Balance and Future Perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jijingi, H.E.; Yazdi, S.K.; Abakr, Y.A.; Etim, E. Evaluation of Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) Technology for Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Its Application in Developing Countries: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katibi, K.K.; Yunos, K.F.; Man, H.C.; Aris, A.Z.; Nor, M.Z.B.M.; Azis, R.S.B. Recent Advances in the Rejection of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds from Water Using Membrane and Membrane Bioreactor Technologies: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Kumar, A.; Pant, S.; Kotecha, K. Wastewater Treatment and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods: A Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143704–143720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.R.; Singh, P.K. Reuse-Focused Selection of Appropriate Technologies for Municipal Wastewater Treatment: A Multi-Criteria Approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 12505–12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attri, S.D.; Singh, S.; Dhar, A.; Powar, S. Multi-Attribute Sustainability Assessment of Wastewater Treatment Technologies Using Combined Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhinda Company. Environmental Services, 2025.

- Muhammad, H.; Othman, B.; Bapeer, G. Development and Performance Assessment of a Novel Integrated MSBR for Sustainable Domestic Wastewater Treatment. ARO 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshgar, S.; Borzooei, S.; Debliek, L.; Van Den Broeck, E.; Cornelissen, R.; De Langhe, P.; Piacezzi, C.; Daza, M.; Duchi, S.; Rehman, U.; et al. A Dynamic Compartmental Model of a Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) for Biological Phosphorus Removal. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N.M.; Aznah, N.A.; Noor, A.S.; Alijah, M.A.; Bee, C.K. Aerobic Sludge Granulation Process in a 4-h Sequencing Batch Reactor for Treating Low Strength Wastewater. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 106, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I.; Ambati, S.R.; Bhos, P.N.; Sonawane, S.; Pilli, S. Effluent Quality Improvement in Sequencing Batch Reactor-Based Wastewater Treatment Processes Using Advanced Control Strategies. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 2661–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svierzoski, N.D.S.; Castellano-Hinojosa, A.; Gallardo-Altamirano, M.J.; Mahler, C.F.; Bassin, J.P.; González-Martínez, A. Evaluating the Effects of Aeration Intermittency on Treatment Performance and the Granule Microbiome in Continuous-Flow Aerobic Granular Sludge Systems. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, T.H.; Gogina, E. Application of Anoxic Phase in SBR Reactor to Increase the Efficiency of Ammonia Removal in Vietnamese Municipal WWTPs. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 97, 01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionkowski, T.; Halecki, W.; Jasiński, P.; Chmielowski, K. Achieving High-Efficiency Wastewater Treatment with Sequencing Batch Reactor Grundfos Technology. Processes 2025, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, A.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Eslami, A.; Rafiee, M. Investigation of Sequencing Batch Moving-Bed Biofilm Reactor to Biodegradation of Cefixime as Emerging Pollutant in Percent of Easily Degradable Co-Substrate. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 2142–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannina, G.; Trapani, D.D.; Viviani, G.; Ødegaard, H. Modelling and Dynamic Simulation of Hybrid Moving Bed Biofilm Reactors: Model Concepts and Application to a Pilot Plant. Biochem. Eng. J. 2011, 56, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusten, B.; Eikebrokk, B.; Ulgenes, Y.; Lygren, E. Design and Operations of the Kaldnes Moving Bed Biofilm Reactors. Aquac. Eng. 2006, 34, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisawa, S.; Shimada, Y.; Yoneda, M. Flow, Stock and Destination of Radioactive Fallout Cs-137 in the Global Environment. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, L.; Foley, J.; Guest, J.S.; Hospido, A.; Larsen, H.F.; Morera, S.; Shaw, A. Life Cycle Assessment Applied to Wastewater Treatment: State of the Art. Water Res. 2013, 47, 5480–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment, Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment, Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Estefan, G.; Sommer, R.; Ryan, J. Methods of Soil, Plant, and Water Analysis: A Manual for the West Asia and North Africa Region, 3rd ed.; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas: Beirut, Lebanon, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Presura, E.; Robescu, L.D. Energy Use and Carbon Footprint for Potable Water and Wastewater Treatment. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2017, 11, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comett, I.; Gonzalez-Martinez, S.; Wilderer, P. Comparison of the Performance of MBBR and SBR Systems for the Treatment of Anaerobic Reactor Biowaste Effluent. Water Sci. Technol. 2003, 47, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirianuntapiboon, S.; Jeeyachok, N.; Larplai, R. Sequencing Batch Reactor Biofilm System for Treatment of Milk Industry Wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 76, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.