Abstract

Drip fertigation (DF) is a sustainable agricultural management technique that optimizes water and nutrient usage, enhances crop productivity, and reduces environmental impact. Herein, we compared the effects of DF and conventional fertilization (CF) with a basal fertilizer on yield, soil inorganic nitrogen dynamics, N2O emissions, and nitrogen leaching during facility-grown eggplant cultivation. The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse from September 2023 to May 2024, with treatments arranged in three rows and three replicates. Soil, gas, and water samples were collected and analyzed throughout the growing season. The results revealed that the DF treatment produced yields comparable to those obtained with the CF treatment while significantly reducing nitrogen and phosphorus inputs. DF effectively prevented excessive nitrogen accumulation in the soil and reduced nitrogen loss through leaching and gas emissions. N2O emissions were significantly lower by more than 60% under DF than under CF. Precise nutrient management in DF suppressed nitrification and denitrification processes, mitigating N2O emissions. DF also significantly reduced nitrogen leaching by more than 70% compared with that in CF. These findings demonstrate that DF effectively enhances agricultural sustainability by improving nutrient use efficiency, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and minimizing nitrogen leaching during the cultivation of facility-grown eggplant.

1. Introduction

Drip fertigation (DF) has emerged as an efficient agricultural management technique that helps optimize water and nutrient usage, enhances crop productivity, and reduces environmental impact. The intensification of farming practices in recent decades has led to a significant increase in nitrogen fertilizer use, resulting in relatively high yields, but simultaneously exacerbating environmental issues such as nitrate (NO3) leaching and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions [1,2,3]. N2O, in particular, is a potent greenhouse gas (GHG) with a global warming potential (GWP) approximately 300 times greater than that of carbon dioxide (CO2), making its reduction critical for sustainable agriculture [4,5,6].

Conventional fertilization (CF) methods, including broadcast and surface application, often cause nutrient unevenness, reduce fertilizer use efficiency, and increase nutrient losses through leaching and volatilization [7,8,9]. In contrast, DF precisely helps supply nutrients to the root zone, significantly improving nutrient use efficiency (NUE) and mitigating environmental impacts [10,11,12].

DF is particularly effective in managing soil salinity and enhancing nutrient uptake, especially in saline–alkaline soils typical of arid and semi-arid regions [13,14,15]. Technological advancements, including the use of proximal sensors, unmanned aerial vehicle-based remote sensing, and real-time soil monitoring systems, have further improved the efficiency of DF [16,17,18]. In greenhouse vegetable systems, several studies have shown that appropriately managed DF can maintain high yields while improving water and nitrogen use efficiencies in crops such as cucumber and tomato [19]. Moreover, field- and region-scale analyses in intensive Chinese greenhouse vegetable production have indicated that optimized nitrogen management and DF-based practices can simultaneously enhance NUE and reduce N2O emissions and nitrate leaching [20,21,22].

Moreover, integrating DF with climate-smart irrigation practices has been demonstrated to improve resource use efficiency and enhance resilience to climate variability [16,23,24]. A recent study has reported that integrating DF with organic amendments, such as biochar and manure, significantly improves the soil structure, enhances nutrient retention, and further minimizes environmental pollution risks, thus supporting sustainable agricultural systems [25]. Furthermore, combining DF with nitrification inhibitors and controlled-release fertilizers reduces nitrogen loss and GHG emissions, enhancing both environmental and economic sustainability in agricultural practices [26,27]. However, most of these studies have focused on crops other than eggplant, and research on eggplant has primarily examined the effects of water and nitrogen management on yield, fruit quality, and nitrogen balance rather than explicitly quantifying N2O emissions and nitrate leaching [28].

In the Kochi Prefecture, eggplant greenhouse cultivation typically continues over long periods and involves relatively high nitrogen application rates, which increases the risk of GHG emissions and nutrient leaching, thus posing considerable environmental contamination risks. Eggplant greenhouse cultivation in this prefecture typically involves planting around September and cultivating continuously for approximately 8 months until around May of the following year. Additionally, studies specifically addressing GHG emissions and nutrient leaching in eggplant cultivation are limited, highlighting the need for targeted research to fill these gaps. Despite the prevalence and environmental significance of eggplant cultivation in Kochi, research focusing specifically on the GHG emissions and nutrient leaching associated with eggplant production remains limited. In this study, we address these critical research gaps.

Herein, we performed a comparative analysis of the effects of DF and CF on yield, soil inorganic nitrogen dynamics, N2O emissions, and nitrogen leaching to provide comprehensive insights into the efficiency and environmental sustainability of DF under precise conditions. In this experiment, DF and CF were compared as two practical fertilization regimes representing fertigated and basal-application-based management commonly used in greenhouse vegetable production, rather than as treatments differing only in total nitrogen rate; accordingly, total N inputs also differed between the two treatments. Our findings provide valuable insights regarding the efficacy of DF in improving NUE, reducing GHG emissions, and minimizing nitrogen leaching during facility-grown eggplant cultivation, thereby enhancing agricultural sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

This study was conducted in a greenhouse (eave height 2.0 m, frontage 7.5 m, and depth 24 m) at the Kochi Prefectural Agricultural Technology Center (Hataeda, Nankoku City, Kochi Prefecture: (33°35′27″ N 133°38′39″ E) (Figure 1). A location map showing the position of the experimental greenhouse within Kochi Prefecture is provided immediately below (Figure 1). The study period was from 1 September 2023, to 24 May 2024. Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) was used as the scion, and the ‘Tosataka’ and ‘Daitaro’ varieties were used as the rootstocks. The pH and cation exchange capacity of the test soil were 6.3 and 17 me 100 g−1, respectively, with total carbon content of 12.5 g kg−1, total nitrogen content of 1.27 g kg−1, and a C/N ratio of 9.84.

Figure 1.

Location of the experimental greenhouse at the Kochi Prefectural Agricultural Technology Center (33°35′27″ N 133°38′39″ E).

2.2. Treatments and Fertilizer Management

This study was conducted using two test plots, with one plot subjected to the CF treatment and the other to the DF treatment.

In the CF treatment, a basal fertilizer with chemical fertilizer 7-8-4 (Huruta Sangyo Co., Ltd., Kochi, Japan) was applied on 15 September prior to planting. Additional fertilization with chemical liquid fertilizer 10-4-8 (ZEN-NOU, Tokyo, Japan) began on 22 October, and fertilizer was supplied daily together with irrigation thereafter. This management followed the fertilization guidelines widely used in commercial eggplant production in Kochi Prefecture.

In the drip fertigation (DF) treatment, no basal fertilizer was applied, and chemical liquid fertilizer 10-4-8 (ZEN-NOU, Tokyo, Japan) was supplied from immediately after planting through the drip irrigation system. After the initial application, fertigation was performed daily in the same manner as the topdressing schedule used in the CF treatment, synchronizing nutrient supply with crop demand during the entire cultivation period. The details of the treatments and fertilizer amounts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Amount of fertilizers applied in each treatment.

Both treatments used the same drip irrigation tubes, which had built-in emitters spaced at 20 cm intervals. Irrigation water for both treatments consisted of groundwater with a pH of 6.5, EC of 0.14 dS m−1, NH4-N concentration of 1.4 ppm, and NO3-N concentration of 2.8 ppm.

2.3. Eggplant Cultivation Methods and Yield Surveys

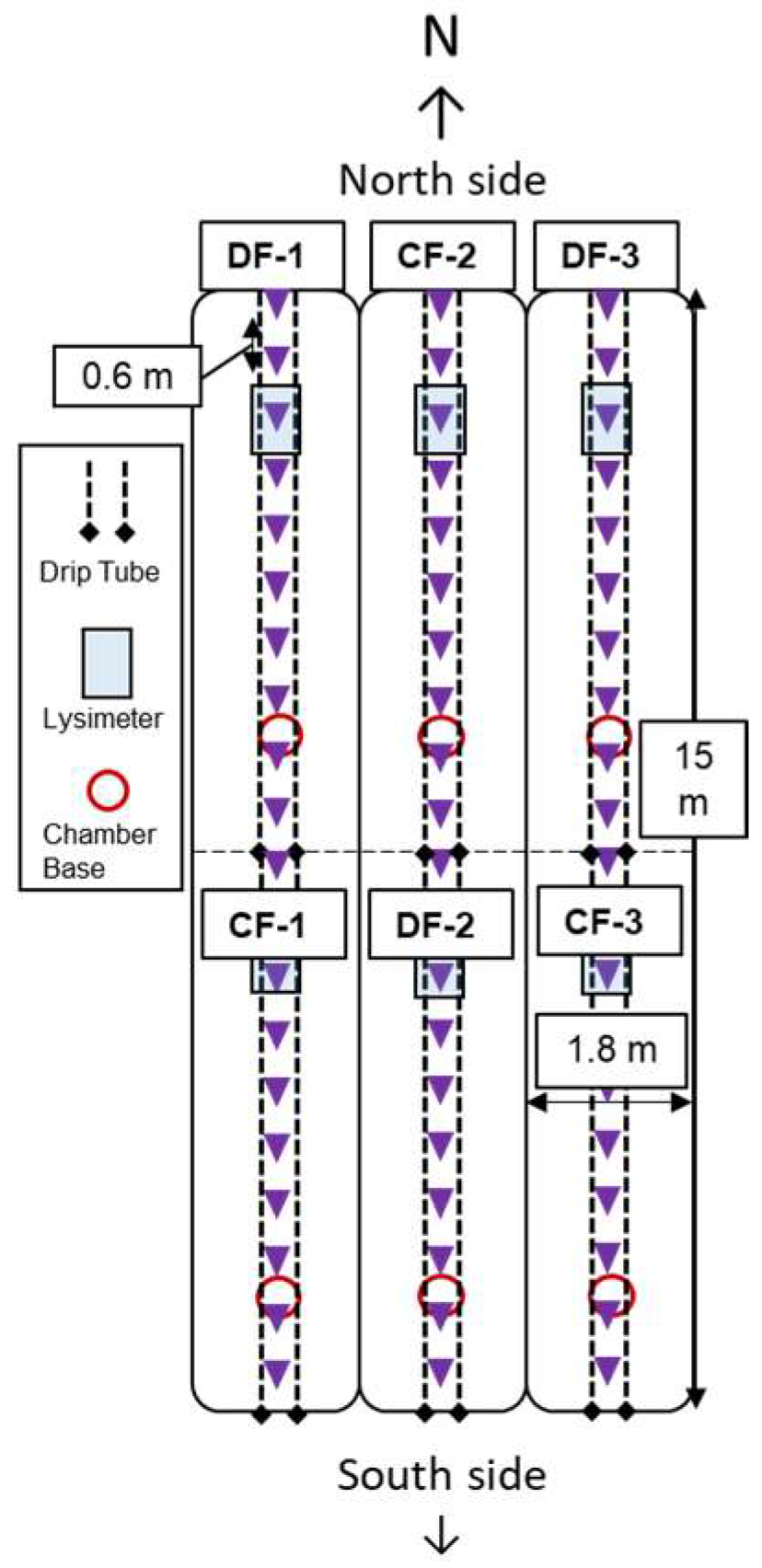

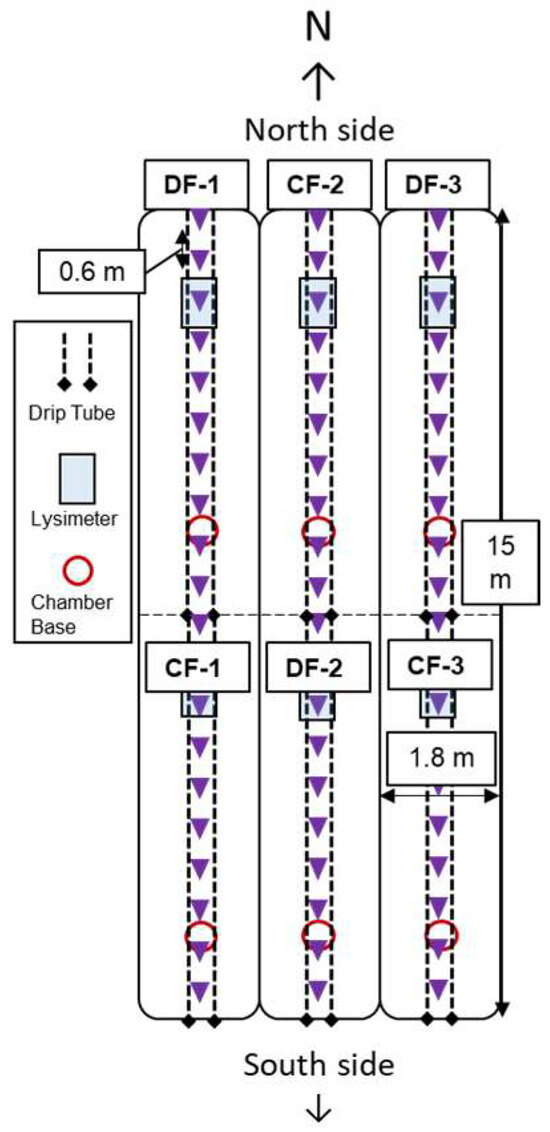

Eggplants were planted on 21 September 2023, at a planting density of 926 plants 10a−1 (swell width 1.8 m × plant spacing 0.6 m), grown on three main branches, and harvested at node 18. Harvesting was conducted from 25 October 2023, to 24 May 2024, and fruits from the main and side branches were collected. The experiment followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three plot blocks, each containing both the CF and DF treatments. Each north–south-oriented bed was divided into two independent subplots, resulting in six experimental units, as shown in Figure 2. Each subplot contained 10 eggplant plants, from which three centrally located plants were selected as yield plants to avoid potential edge effects. Yield surveys were conducted 2–3 times per week to determine the total weight and number of fruits from the three research plants.

Figure 2.

Layout and details of experimental treatments in the test field. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

2.4. Irrigation Regime and Soil Physical Conditions

Irrigation in both treatments was applied through an automated drip irrigation system. From transplanting (21 September) onward, irrigation was scheduled two times per day during the early growth stage, and gradually increased to up to five times per day during periods of high evaporative demand. In addition to drip irrigation, hand-watering (1200 mL plant−1 day−1) was performed from 21 to 29 September to promote root establishment. All irrigation practices were identical between CF and DF.

The total irrigation amount, including both drip irrigation and hand-watering, was 486 mm in the CF treatment and 496 mm in the DF treatment.

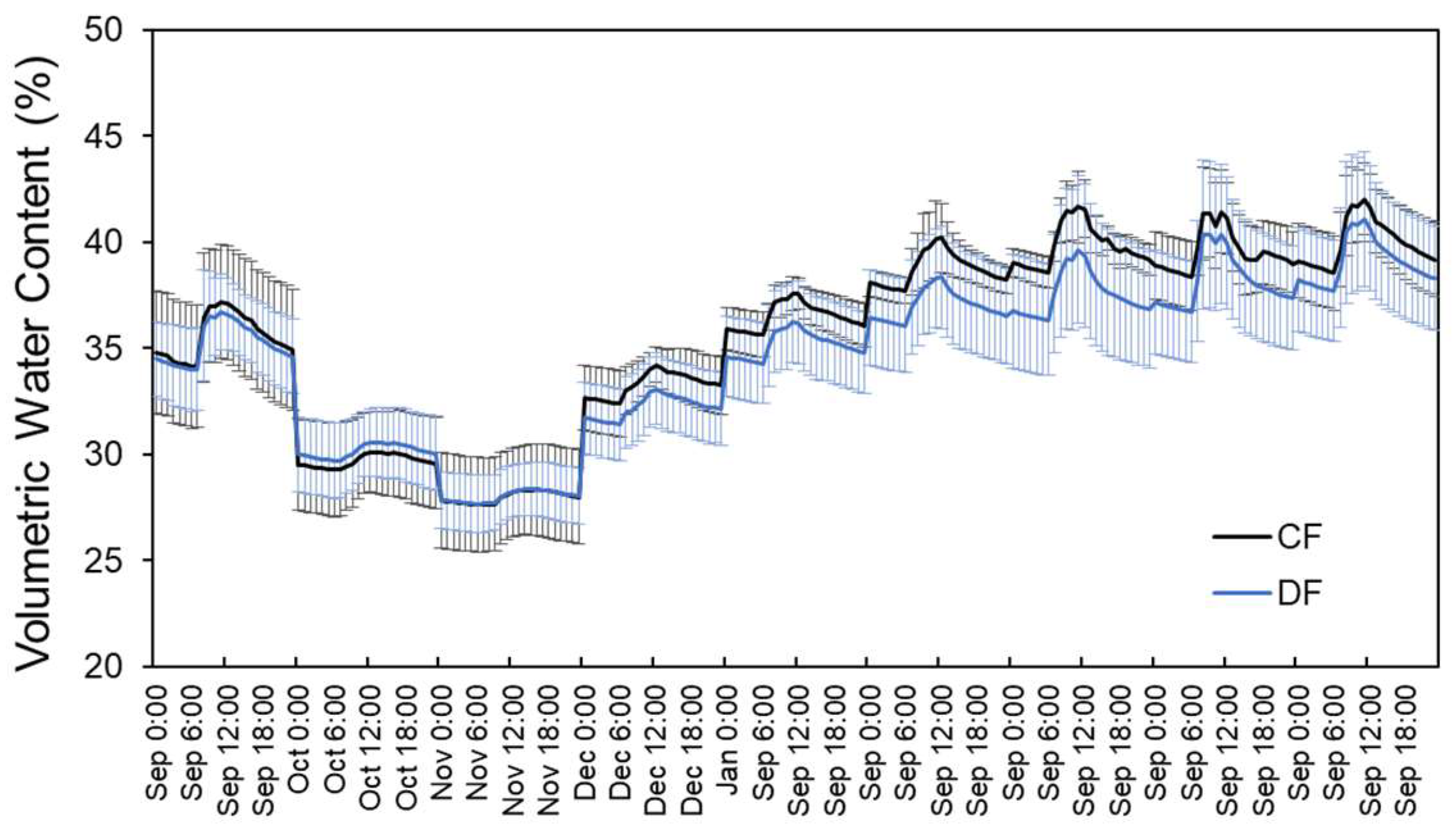

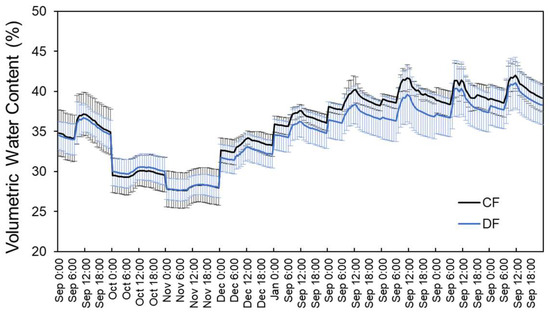

Soil volumetric water content and soil temperature were continuously monitored using a combined soil moisture and temperature sensor (WD-3, ARP Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan) installed at a depth of 15 cm in the central row of each subplot. Measurements were logged hourly and averaged to generate monthly temporal profiles. The sensors recorded values hourly, and these data were summarized as daily means to visualize temporal fluctuations throughout the cultivation period (Figure 3). Across the entire growing season, the average VWC was 36% in the CF plots and 35% in the DF plots, indicating no substantial differences between treatments.

Figure 3.

Temporal changes in soil volumetric water content measured hourly at 15 cm depth under CF and DF treatments. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3).

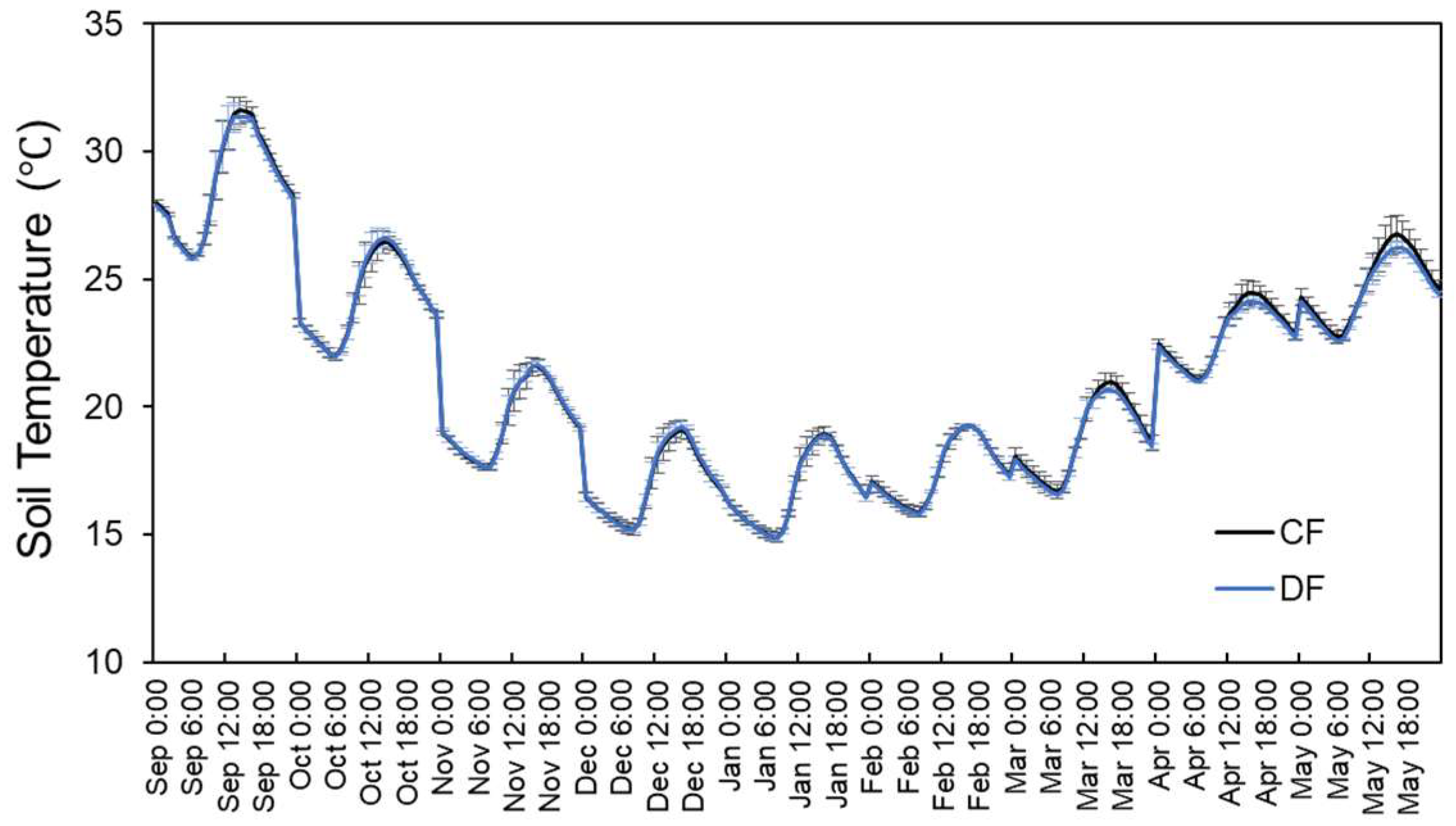

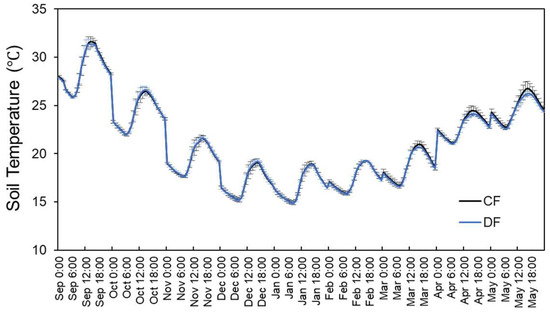

Soil temperature was recorded at the same depth and summarized in the same manner. Daily mean soil temperatures ranged from approximately 27–31 °C in September to 18–21 °C during the mid-winter period (January–February), increasing gradually toward late spring (Figure 4). Similarly to the VWC trends, no consistent difference in soil temperature was observed between CF and DF.

Figure 4.

Temporal changes in soil temperature measured hourly at 15 cm depth under CF and DF treatments. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3).

2.5. Sampling and Analyses

2.5.1. Soil Sampling and Analyses

During the growing season, the 0–15 cm soil layer was sampled every 2–3 weeks. Soil ammonium-nitrogen (NH4+-N) and nitrate-nitrogen (NO3−-N) contents were analyzed using the Bremner distillation method after the soil was extracted with 10% KCl.

2.5.2. Gas Sampling and Analyses

The gases emitted from the soil were collected in situ from September 2023 to May 2024 using the closed-chamber method. In each replicate plot, a circular frame was permanently embedded into the soil up to a depth of 5 cm. The frames were embedded between the plants in the center of the eggplant rows. A circular chamber with a diameter of 38.5 cm and a height of 11 cm was mounted onto the frame, and the groove was filled with water to seal the chamber during gas sampling. The sampling period was once every 2 days from immediately after base fertilizer application until planting and once every 2–3 weeks from planting to the end of cultivation. Gas samples were collected between 0900 and 1000 h. When collecting the gas, the drip tube on the base was removed, and the chamber was covered. At 0, 5, and 10 min after the chamber was covered, gas was collected using a 20 mL syringe and stored in a vial (SVG-10; Nichiden-Rika Glass Co., Ltd., Hyogo, Japan). The collected gases were analyzed for CO2 content using gas chromatography (GC-8A; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), and methane (CH4) and N2O contents were analyzed using gas chromatography with flame ionization detector and electron-capture detector (GC-14A; Shimadzu, Japan). The flux of each gas emitted from the soil after the measurements was determined with reference to the linear regression method on Toma et al. (2011) [29] Equation (1) as follows:

where F is the flux (mg m−2 h−1), ρ represents the density of gas (mg m−3; CH4-C: 0.536, N2O-N: 1.25, and CO2-C: 0.536), V is the air volume in the chamber (m3), A represents the bottom area of the chamber, Δc/Δt is the average acceleration of gas concentration in the chamber (10−6 m3 m−3 h−1), and T represents the average air temperature inside the chamber (K).

F = ρ ∗ V/A ∗Δc/Δt ∗ 273/T,

2.5.3. Water Sampling and Analyses

A lysimeter with 606 mm (width) × 303 mm (depth) × 800 mm (height) dimensions was buried in each replicate, and one eggplant plant was grown inside the lysimeter. The bottom 200 mm of the lysimeter was used as the water collection area, and the dissolved dehydration was periodically collected using a multi-dry pump (MP-30; AS ONE Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Dissolved dewatering was measured using the Bremner distillation method to determine the amount of water and NO3−-N concentration in the dissolved water, and each value was multiplied to determine the amount of dissolved nitrogen.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

One-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s method were used for multiple comparisons. An add-in software, i.e., Statcel5 for Excel, was used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N Contents and Yield

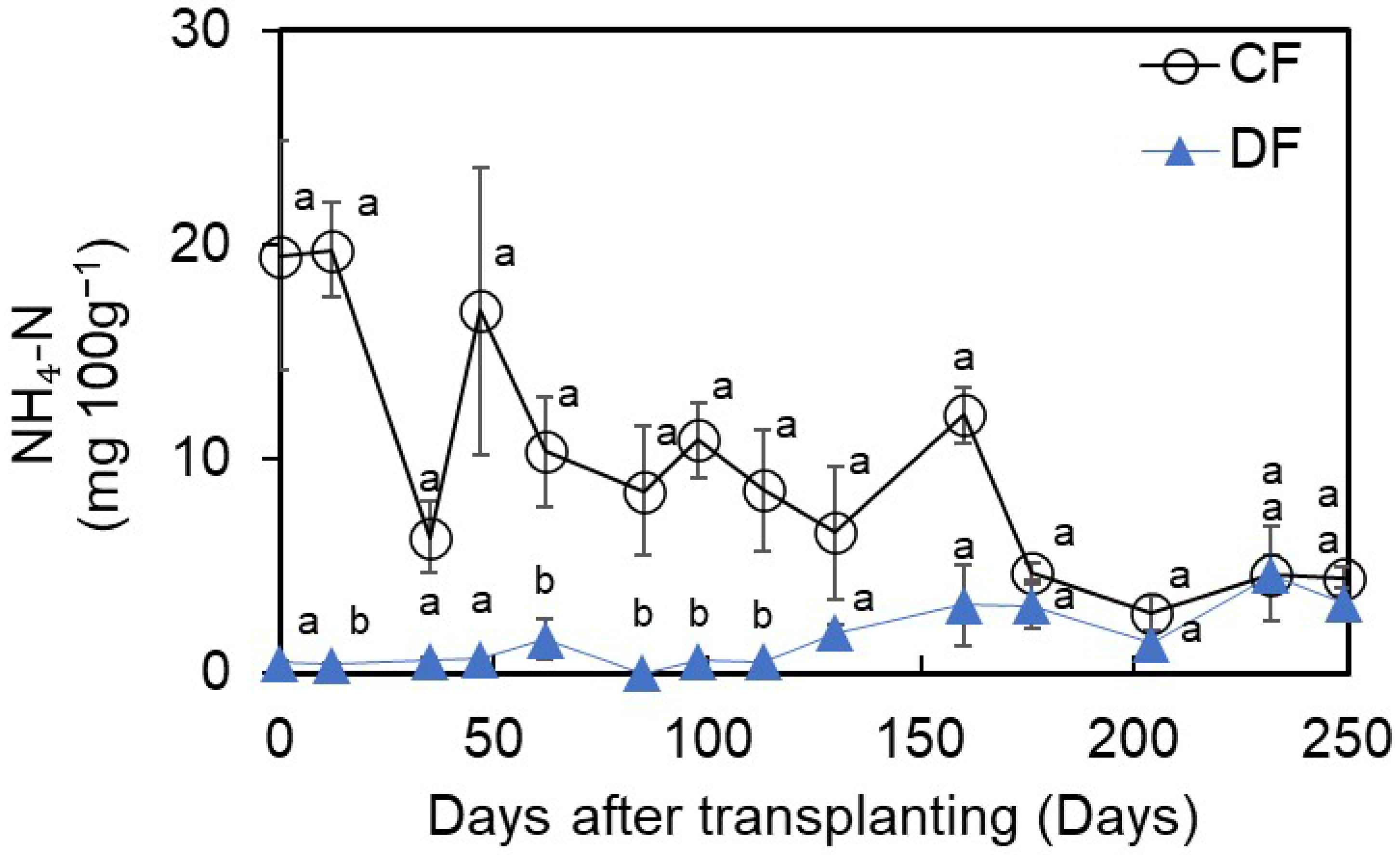

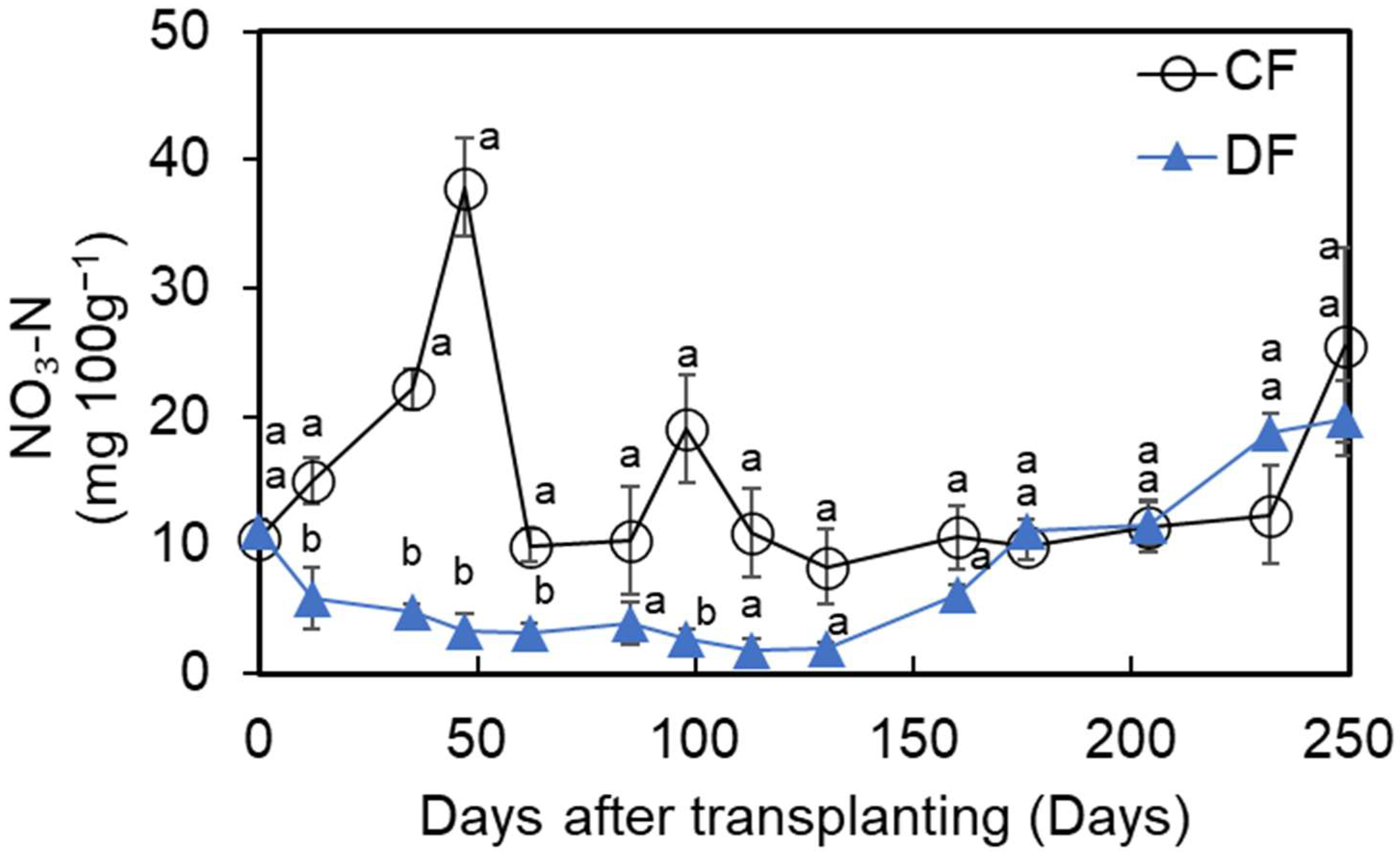

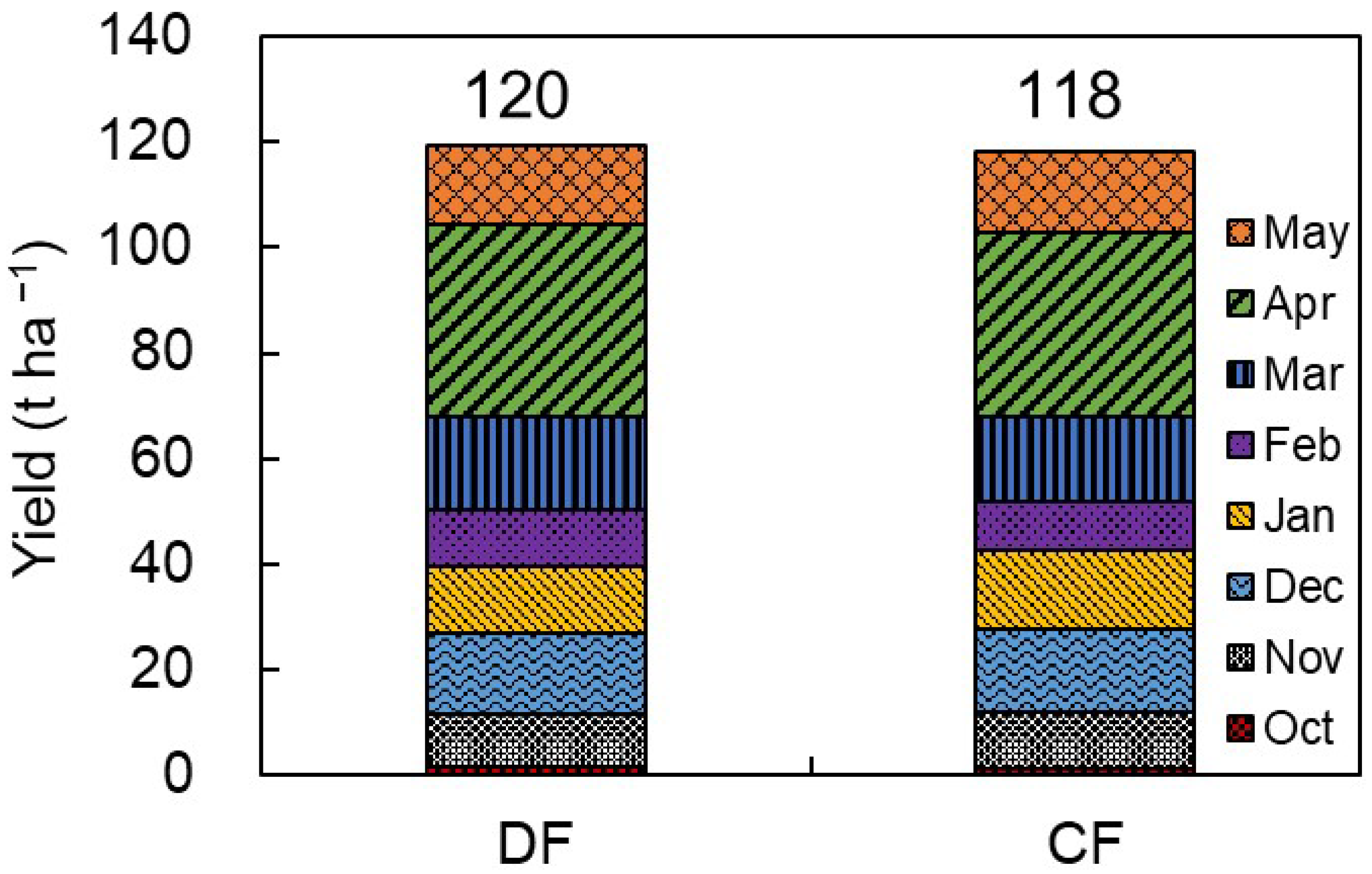

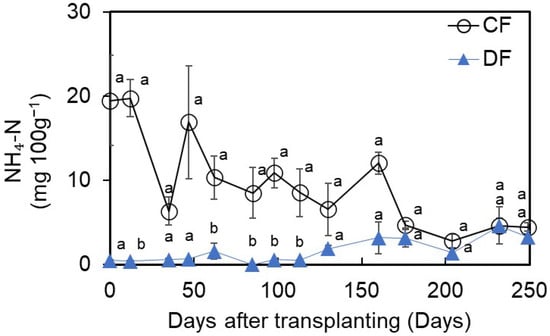

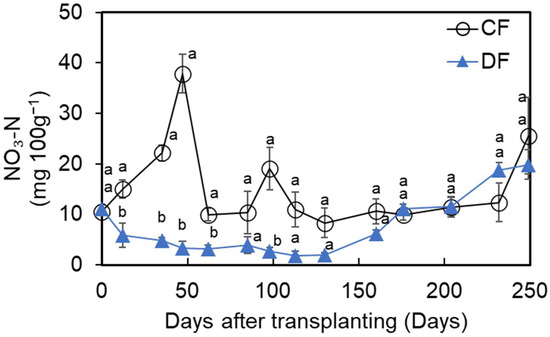

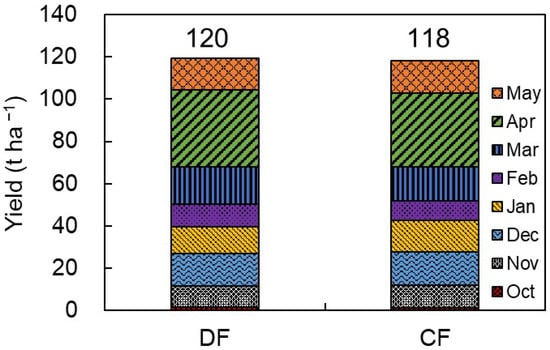

The soil NH4+-N content under the DF treatment remained low throughout the growing season (Figure 5). However, the soil NO3−-N content under the DF treatment was lower than that under the CF treatment until the middle of the growing season but attained levels comparable to those under the CF treatment in the late growing season (Figure 6). Seasonal yield distribution and total marketable yield did not differ substantially between DF and CF (Figure 7). The total yield over the entire cultivation period was 120 t ha−1 for DF and 118 t ha−1 for CF. Monthly yield patterns were also similar between treatments, although DF tended to produce slightly higher yields in several months.

Figure 5.

Changes in ammonium-nitrogen (NH4+-N) content in the soil during eggplant cultivation. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different treatments at the measurement date according to Tukey’s test. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

Figure 6.

Changes in soil nitrate-nitrogen (NO3−-N) content during eggplant cultivation. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different treatments at the measurement date according to Tukey’s test. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

Figure 7.

Monthly and total marketable yield of eggplant. Bars represent the stacked monthly yields for each treatment, with the total seasonal yields shown above the columns. Each bar represents the cumulative yield of three centrally positioned plants per subplot, averaged across three replicates. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

3.2. CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes and Total GHG Emissions

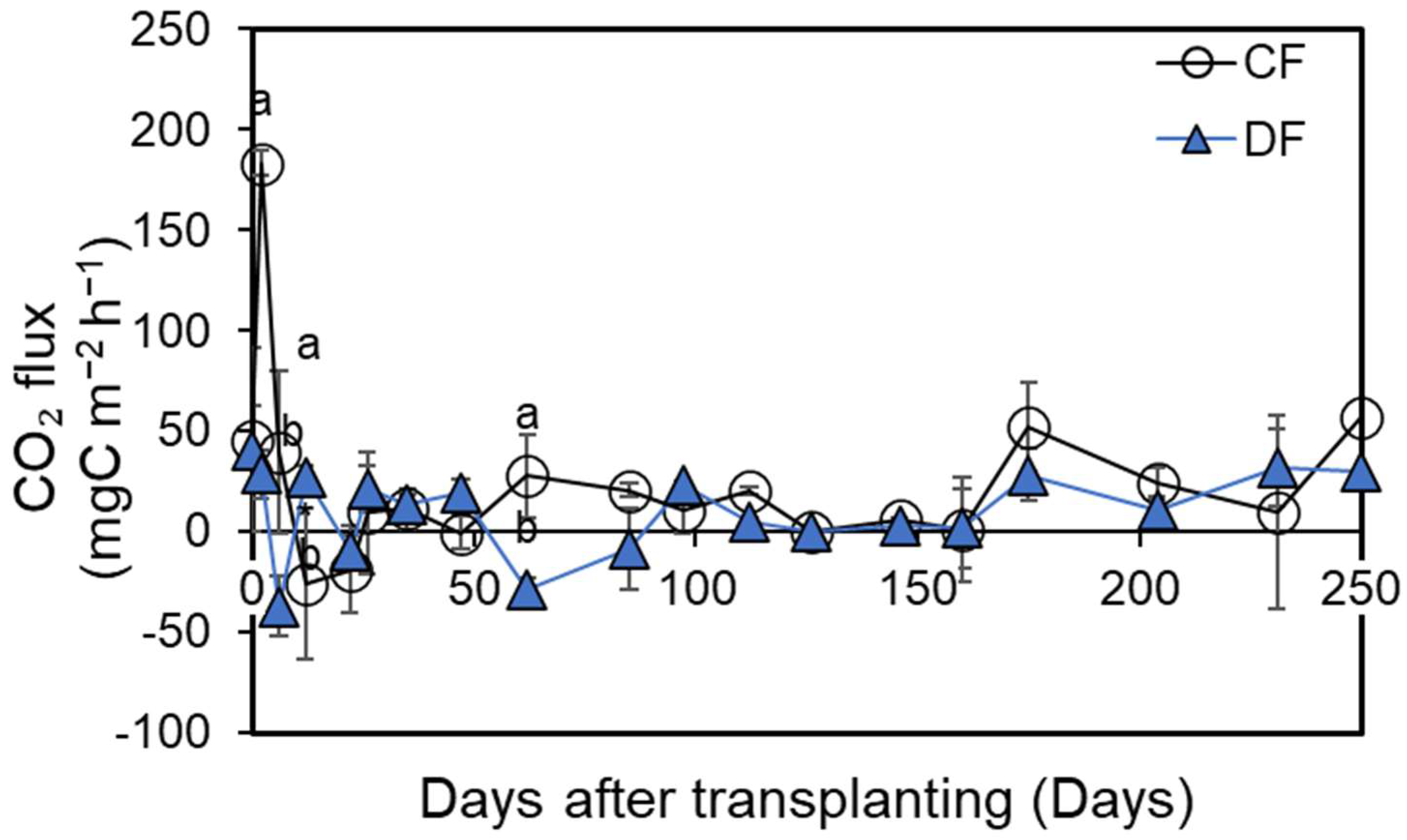

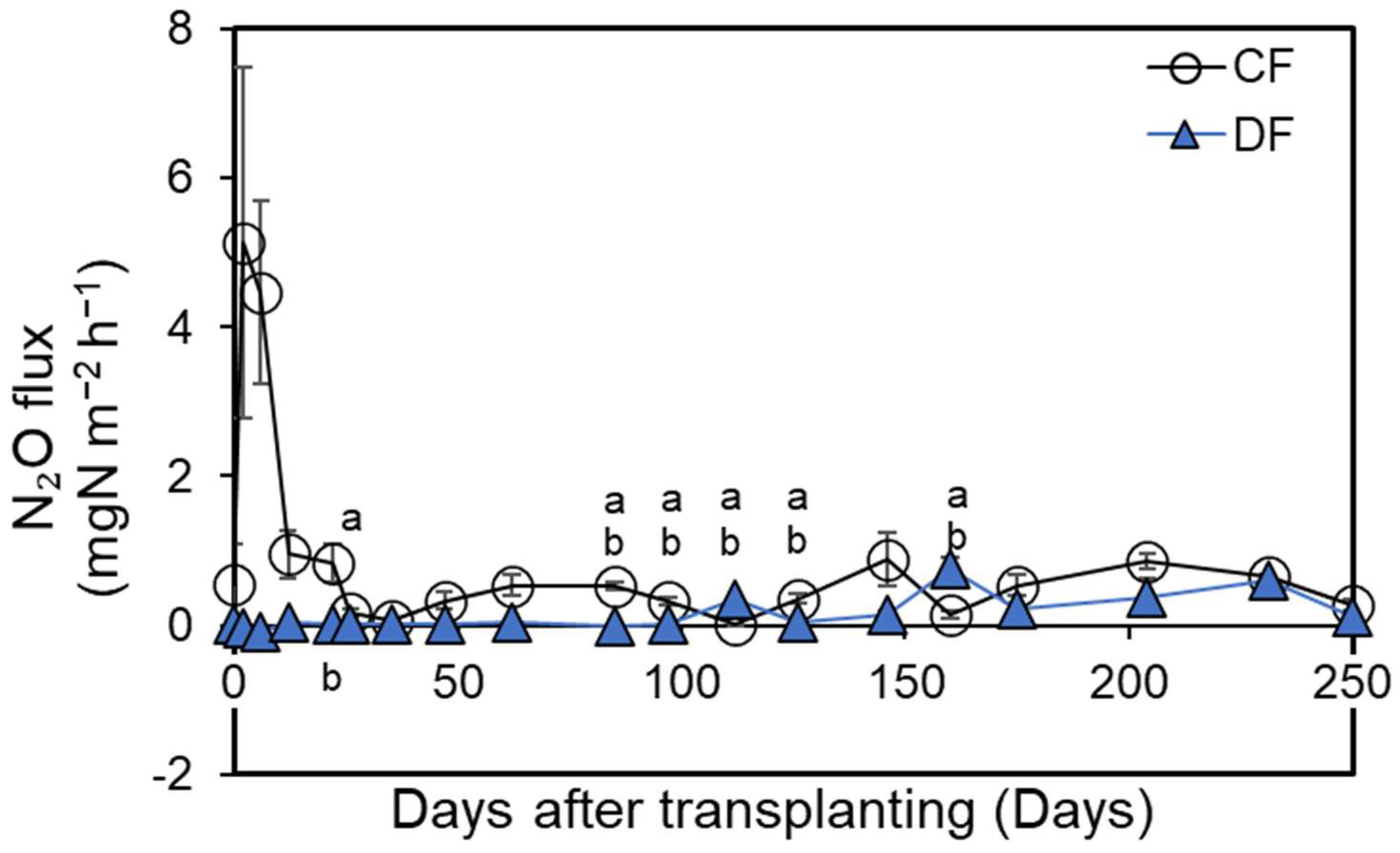

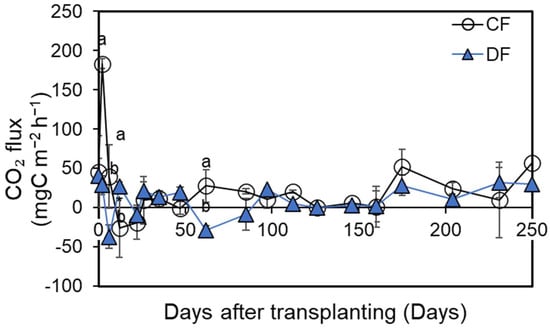

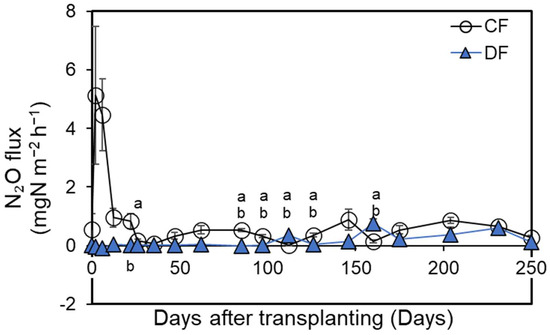

The CO2 gas fluxes are shown in Figure 8, with CF showing a flux peak within a week of planting and the highest value on the second day of planting throughout the growing period. The DF treatment did not show a CO2 flux peak observed in the CF treatment during the first week after planting. Moreover, the CO2 flux remained low throughout the experimental period in the DF treatment. CH4 flux did not show a peak during the growing season in either treatment and remained near zero (data omitted). The N2O fluxes are shown in Figure 9, with CF showing a flux peak within a week of planting and the highest value on the second day of planting, throughout the growing period. The DF treatment did not show an N2O flux peak observed in the CF treatment during the first week after planting. Overall, the N2O flux in the DF treatment remained lower than that in the CF treatment throughout the experimental period.

Figure 8.

Changes in carbon dioxide (CO2) flux during eggplant cultivation. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different treatments at the measurement date according to Tukey’s test. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

Figure 9.

Changes in nitrous oxide (N2O) flux during eggplant cultivation. Values are presented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different treatments at the measurement date according to Tukey’s test. Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

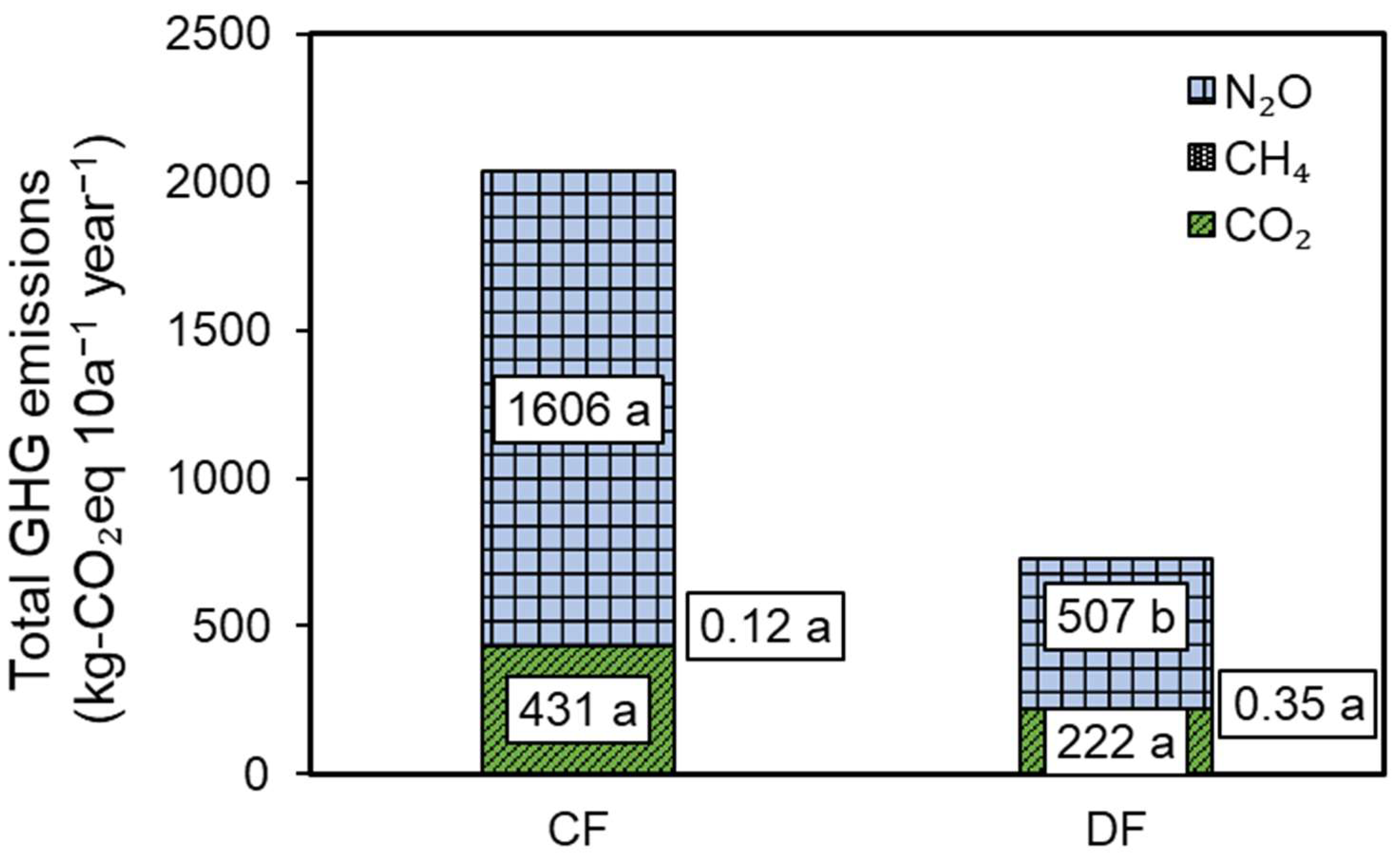

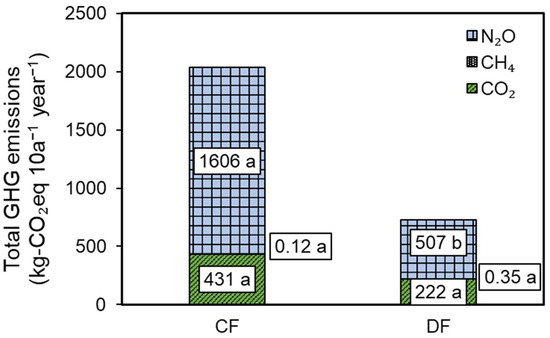

The total GHG emissions obtained by multiplying the total gas emissions, i.e., the sum of the fluxes of each gas during the growing season, and their GWP, are shown in Figure 10. N2O emissions dominated the total GHG emissions throughout the growing season of institutional eggplants in both zones, being 69.6% in DF and 78.9% in CF, followed by CO2 at 30.4% in DF and 21.1% in CF, and CH4 at less than 0.1% in both zones. The total N2O emissions were significantly lower by more than 60% under the DF treatment than under the CF treatment. There were no significant differences in the total CO2 and CH4 emissions between the treatments.

Figure 10.

Total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout the cultivation period (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different treatments according to Tukey’s test.Abbreviations: CF, conventional fertilization; DF, drip fertigation; CO2, carbon dioxide; N2O, nitrous oxide; and CH4, methane.

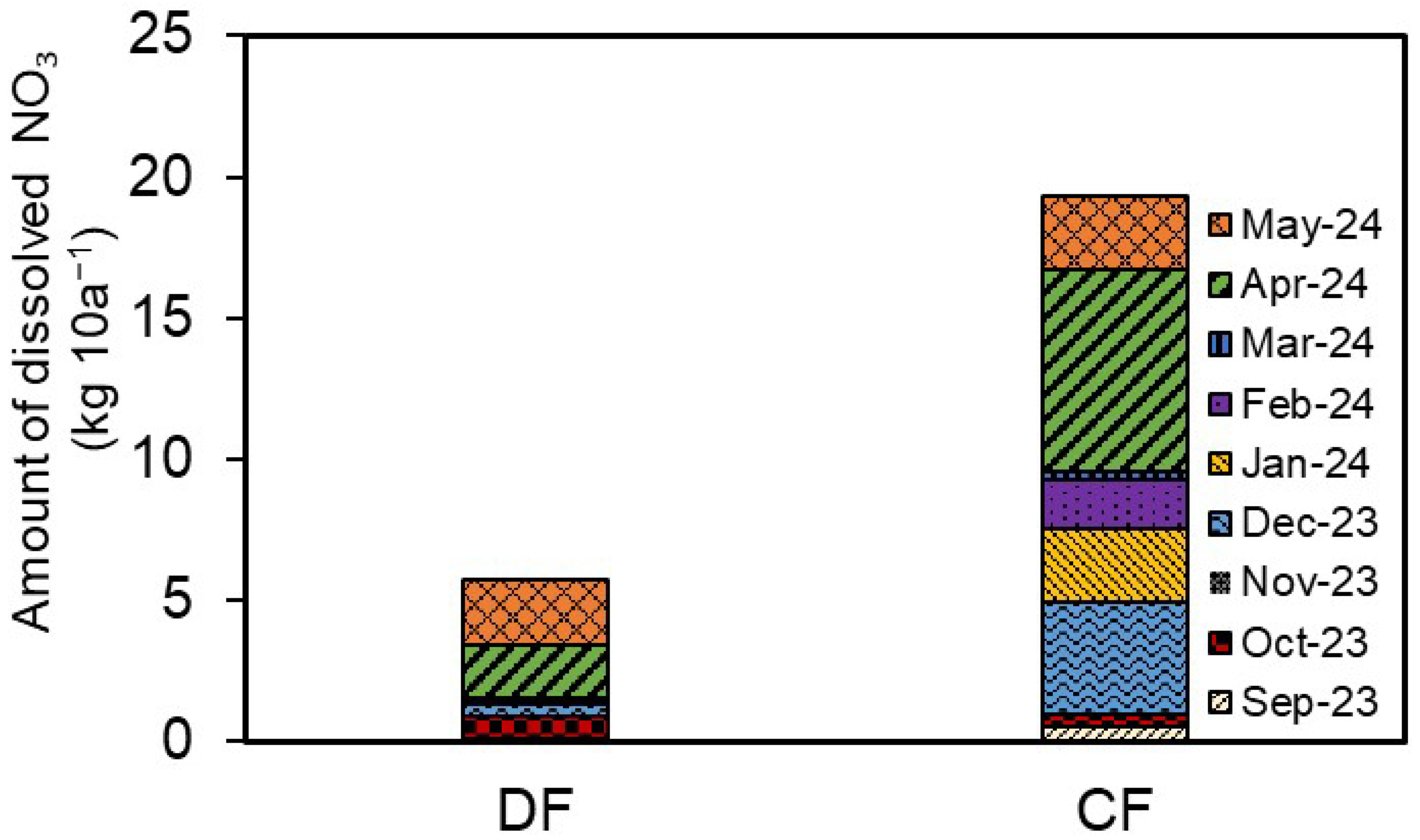

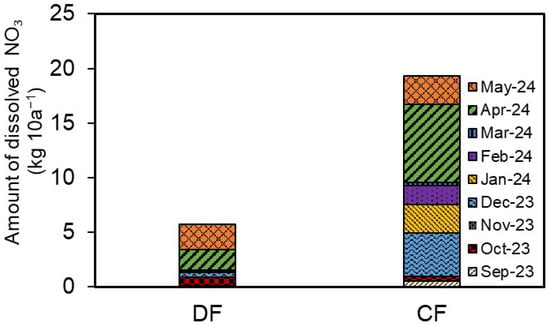

3.3. Dissolved NO3 Content

The amount of dissolved nitrogen under the DF treatment was significantly lower than that under the CF treatment during most periods (Figure 11). The total leached nitrogen was 70% lower than that under CF. The total volume of leached water was 74.2 ± 17.8 L and 108.8 ± 6.0 L for DF and CF, respectively (data omitted), being 32% lower for DF, but not significantly different between the treatments.

Figure 11.

Monthly dissolved nitrate (NO3) amounts (n = 3). Abbreviations: DF, drip fertigation; CF, conventional fertilization.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the DF Treatment on Yield and Soil Inorganic Nitrogen Content in Eggplant Cultivation

The results obtained in this study demonstrated that the DF treatment helped effectively maintain crop yields comparable to those under the CF treatment while significantly reducing nitrogen and phosphorus inputs. Optimized nitrogen fertilization under DF closely matches the nutrient supply to crop demands, enhancing nutrient uptake and reducing residual nitrogen in soils [30,31,32]. Fang et al. (2024) [25] reported significant improvements in yield and NUE with precise DF management over those obtained with traditional methods. Similarly, Liao et al. (2025) [31] reported enhanced cotton yield and NUE when deficit irrigation was combined with precise nitrogen management under DF.

Moreover, consistently low ammonium and NO3 concentrations were observed in the DF-treated soils for approximately 150 days after planting, suggesting that DF effectively prevents excessive nitrogen accumulation, reducing nitrogen loss through leaching and gas emission [11,15,16]. Ren et al. (2025) [32] demonstrated that the use of bio-organic fertilizers under DF significantly reduced residual NO3 and dissolved organic nitrogen concentrations, thus enhancing the nitrogen cycling efficiency.

In addition, the earlier and mid-season differences in soil inorganic N between DF and CF reflect the distinct fertilization regimes applied in this study. Because DF relies solely on liquid fertilizer without a basal application, soil N concentrations remained low and stable, whereas CF began with a large one-time basal N input that contributed to higher soil NO3− levels. This difference represents actual commercial practices in greenhouse eggplant production and aligns with previous findings showing that fertigation-based management reduces soil N accumulation even when total N inputs differ [10,24,25,26].

4.2. Effects of the DF Treatment on GHG Emissions in Eggplant Cultivation

In this study, we found significant differences in N2O emissions between the DF and CF treatments. CF showed a pronounced peak in N2O emissions immediately after fertilization, whereas DF did not exhibit such a peak. The rapid emission peak observed in the CF treatment initially was likely triggered by the abundance of ammonium in the soil and the irrigation of dry soil immediately after planting, thereby activating both nitrification and denitrification microbial processes [11,13,14].

In this experiment, the field was watered for approximately 20 min on 23 August 2023, immediately before tillage. Subsequently, no water was applied until transplanting on September 21, resulting in dry soil conditions with a soil moisture content of 11.2 ± 0.7% at the time of planting. This condition likely intensified the microbial nitrification and denitrification processes, causing the N2O emission peak observed in the CF [25,31].

It was challenging to definitively distinguish whether nitrification or denitrification dominated the N2O emission peak under the CF treatment. However, discrepancies in soil ammonium and NO3 concentrations and the timing of the N2O emission peak suggest that this rapid emission was not owing to a single simple process, but instead involved both microbial processes [15,16,32].

In contrast, the DF plots showed no rapid peaks in N2O emissions. Precise nutrient management in DF consistently maintains low nitrogen concentrations in the soil, effectively suppressing nitrification and denitrification processes, mitigating N2O emissions [33]. Similar suppression effects on N2O emissions were reported by Ni et al. (2022) [11] and Zhang et al. (2023) [34], highlighting the consistent environmental benefits of DF.

Soil moisture and temperature data further support these interpretations. Monthly-averaged volumetric water content and soil temperature remained stable and comparable between treatments, indicating that the observed differences in N2O emissions were primarily caused by fertilization strategy rather than soil physical conditions. This directly addresses previous concerns regarding missing soil moisture and temperature information, providing stronger evidence for the mechanistic validity of the observed treatment effects.

4.3. Effects of the DF Treatment on Nitrogen Leaching in Eggplant Cultivation

The DF treatment significantly reduced nitrogen leaching compared with that under the CF treatment. During the early growth stages from September to November, leaching was minimal in both treatments. However, in December, leaching was observed in all lysimeters, indicating that irrigation exceeded the water requirements of the plants [14,16]. Despite the similar total leaching volumes until December for both treatments, the amount of nitrogen leached was lower in DF than in CF [13,17].

In the CF treatment, the NO3 concentration in the December leachate was much higher than that in the DF treatment, and approximately 20% of the total leaching occurred during this period. In comparison to the results from the DF treatment, it can be inferred that the excessive nitrogen input from the basal fertilizer in the CF treatment remained in the soil and was not absorbed by the plants, and the residual nitrogen leached out owing to excessive irrigation in December [10,30,31].

Fang et al. (2024) [25] reported that reducing the basal fertilizer input in fertigation strategies prevented excessive nitrogen leaching and improved nitrogen use efficiency, consistent with our findings.

The low NO3−–N content in DF soils during most of the growing season also contributed to its reduced leaching losses. Studies in cucumber and tomato greenhouse systems similarly report that DF suppresses NO3− buildup, reducing the risk of deep percolation losses even under conditions of excessive irrigation [24,25,26]. These findings confirm that fertigation-based N supply is effective in minimizing reactive N losses across multiple horticultural systems, including eggplant.

4.4. Comprehensive Implications of the Application of the DF Treatment in Eggplant Cultivation

The DF treatment significantly improved nitrogen use efficiency, reduced GHG emissions, and minimized nitrogen leaching without compromising yield compared with that in the CF treatment. Recent studies have highlighted that integrating DF with sustainable management practices and advanced technologies can enhance environmental and agronomic performance. For instance, incorporating biochar-based fertilizers with DF significantly increases NUE and reduces GHG emissions and NO3 leaching [26]. Additionally, combining DF with nitrification inhibitors and controlled-release fertilizers has resulted in substantial reductions in nitrogen loss and emissions, promoting sustainable agriculture [27].

Moreover, global meta-analyses indicate that optimized DF practices can significantly lower NO3 leaching vulnerability and reactive nitrogen losses, improving agricultural sustainability and reducing environmental pollution [35,36]. The innovative use of organic and biosorbent-based materials derived from agricultural residues, such as eggplant-derived biosorbents, further demonstrates the potential benefits of NO3 removal and water purification within DF systems [37,38].

Integrating these innovative management practices and technologies into DF represents a promising approach to enhancing sustainability in intensive agricultural production systems. Future studies must focus on validating these integrated practices in diverse agricultural settings and quantifying their environmental and economic impact.

In addition, the present findings provide some of the first detailed comparisons of soil nitrogen behavior, N2O emissions, and leaching losses between DF and CF in long-cycle greenhouse eggplant cultivation. Given the limited number of eggplant-specific studies in the international literature, the results contribute valuable new evidence and highlight the importance of expanding research in this crop.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the experiment was conducted over a single cultivation season, and multi-year trials are needed to verify the robustness of the results under varying climatic and soil conditions. Second, because CF and DF were designed to represent practical fertilization regimes actually used in greenhouse eggplant production, the total N inputs were not equal between treatments. This practical but asymmetrical design limits the ability to isolate fertilization method effects from fertilizer amount effects. Third, although three independent subplots per treatment were used under a randomized block layout, the replication number remains modest compared with large field trials. Fourth, soil sampling was restricted to the 0–15 cm layer following conventions in greenhouse studies; however, deeper sampling could help quantify subsoil N accumulation and leaching potential. Finally, while soil moisture and temperature data were included, other factors such as microbial community composition were not analyzed, and these may provide further mechanistic insights.

Author Contributions

W.S., S.N., M.M. and H.U. conceived and designed the experiments; W.S., M.M. and H.U. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; all authors contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Cabinet Office grant in aid “Evolution to Society 5.0 Agriculture Driven by IoP (Internet of Plants)”, Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yo Toma in the Soil Science Laboratory at the Research Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University and Toshiyuki Takase at the Kochi Prefectural Agricultural Research Center, for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DF | Drip fertigation |

| CF | Conventional fertilization |

| N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

References

- Zhang, F.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Xi, Z.; Liu, Z. Mechanisms of N2O emission in drip-irrigated saline soils: Unraveling the role of soil moisture variation in nitrification and denitrification. Agronomy 2024, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Liu, S.; Qu, Z.; Song, H.; Qin, W.; Guo, J.; Chen, Q.; Lin, S.; Wang, J. Contribution and driving mechanism of N2O emission bursts in a Chinese vegetable greenhouse after manure application and irrigation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Yin, M.; Gui, D.; Zeng, F. Soil profile N2O efflux from a cotton field in arid Northwestern China in response to irrigation and nitrogen management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1123423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jha, S.K.; Gao, Y.; Shen, X.; Sun, J.; Duan, A. Mitigated CH4 and N2O emissions and improved irrigation water use efficiency in winter wheat field with surface drip irrigation in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 163, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Meng, F.; Ma, J. Impact of drip irrigation and nitrogen fertilization on soil microbial diversity of spring maize. Plants 2022, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Baggs, E.M.; Dannenmann, M.; Kiese, R.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: How well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Heinen, M.; Ritzema, H.; Hellegers, P.; van Dam, J. Fertigation strategies to improve water and nitrogen use efficiency in surface irrigation system in the North China plain. Agriculture 2022, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, H. Optimizing the nitrogen use efficiency in vegetable crops. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 106–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Research progress on N2O emissions from soil in facility vegetable plot. J. Geosci. Environ. Protect 2018, 6, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wu, Y.; Tian, Z.; Xu, H. Nitrogen use efficiency, crop water productivity and nitrous oxide emissions from Chinese greenhouse vegetables: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Pacholski, A.; Kage, H. Reduced fertilization mitigates N2O emission and drip irrigation has no impact on N2O and NO emissions in plastic-shed vegetable production in northern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 334, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, L. Multiple-year nitrous oxide emissions from a greenhouse vegetable field in China: Effects of nitrogen management. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasim, W.; Wan, L.; Lv, H.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, J.; Meng, F.; Lin, S.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Impact of anaerobic soil disinfestation on seasonal N2O emissions and N leaching in greenhouse vegetable production system depends on amount and quality of organic matter additions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Hao, X.; Carswell, A.; Misselbrook, T.; Ding, R.; Li, S.; Kang, S. Inorganic nitrogen fertilizer and high N application rate promote N2O emission and suppress CH4 uptake in a rotational vegetable system. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 206, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Gu, B.; Wu, Y.; Galloway, J.N. Manure-nitrogen substitution for urea leads to higher yield but increases N2O emission in vegetable production on nitrate-rich soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 354, 108257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, T.; Wang, B.; Wan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Cai, A.; Hassan, W. NH3, N2O, NO and NO2 losses, emission factors and reduction mechanisms under different N managements from greenhouse vegetable soils. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. Simulation of water and nitrogen dynamics as affected by drip fertigation strategies. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 2434–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, M.Á.; Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R. Fertigation to recover nitrate-polluted aquifer and improve a long time eutrophicated lake, Spain. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 288, 108580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhao, Y.; Peacock, C.L.; Lv, H.; Feng, P.; Lin, S.; Hu, K. Mitigating N leaching and N2O emissions by combining drip irrigation and reduced fertilization with straw incorporation in greenhouse tomato systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 321, 109928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Wu, L.; Fang, D.; Zou, H.; Xiang, Y. Optimal drip fertigation management improves yield, quality, water and nitrogen use efficiency of greenhouse cucumber. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Lin, S.; Wang, Y.; Lian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Drip fertigation significantly reduces nitrogen leaching in solar greenhouse vegetable production system. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.A.A.; Wei, Q.; Xu, J.; Hamoud, Y.A.; He, M.; Shaghaleh, H.; Wei’, Q.; Li, X.; Qi, Z. Managing fertigation frequency and level to mitigate N2O and CO2 emissions and NH3 volatilization from subsurface drip-fertigated field in a greenhouse. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Optimizing water-fertilizer integration with drip irrigation management to improve crop yield, water, and nitrogen use efficiency: A meta-analysis study. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callau-Beyer, A.C.; Mburu, M.M.; Weßler, C.F.; Amer, N.; Corbel, A.L.; Wittnebel, M.; Böttcher, J.; Bachmann, J.; Stützel, H. Effect of high frequency subsurface drip fertigation on plant growth and agronomic nitrogen use efficiency of red cabbage. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 297, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhang, G.; Ming, B.; Shen, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Z.; Xue, J.; Xie, R.; et al. Dense planting and nitrogen fertilizer management improve drip-irrigated spring maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency in Northeast China. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Sun, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, F. Effects of reducing nitrogen application and adding straw on N2O emission and soil nitrogen leaching of tomato in greenhouse. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasim, W.; Xia, L.; Lin, S.; Wan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Global greenhouse vegetable production systems are hotspots of soil N2O emissions and nitrogen leaching: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 272, 116372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Chen, X.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Optimizing water and nitrogen management strategies to improve their use efficiency, eggplant yield and fruit quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, Y.; Fernández, F.G.; Sato, S.; Izumi, M.; Hatano, R.; Yamada, T.; Nishiwaki, A.; Bollero, G.; Stewart, J.R. Carbon budget and methane and nitrous oxide emissions over the growing season in a Miscanthus sinensis grassland in Tomakomai, Hokkaido, Japan. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2011, 3, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Niu, M.; Ma, J.; Quan, Z.; Chi, G.; Lu, C.; Huang, B. Cutting nitrogen leaching in greenhouse soil by water-nitrogen partially decoupled drip fertigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 311, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Liu, H.; Tian, Q.; Zhou, B.; Yang, H.; Hou, Z. Deficit drip irrigation combined with nitrogen application improves cotton yield and nitrogen use efficiency by promoting plant 15N uptake and remobilization. Field Crops Res. 2025, 324, 109792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Dong, L.; Liang, G.; Han, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, Q.; Wei, D.; Zou, H.; Zhang, Y. Microbially mediated mechanisms underlie N2O mitigation by bio-organic fertilizer in greenhouse vegetable production system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 211, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bo, Y.; Adalibieke, W.; Winiwarter, W.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Sun, Z.; Tian, H.; Smith, P.; Zhou, F. The global potential for mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from croplands. One Earth 2024, 7, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, W.; Ding, L.; Zhou, C.; Ma, H. Effects of coordinated regulation of water, nitrogen, and biochar on the yield and soil greenhouse gas emission intensity of greenhouse tomatoes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchard, N.; Schirrmann, M.; Cayuela, M.; Kammann, C.; Wrage-Mönnig, N. Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, A.P.; Grutzmacher, P.; Cerri, C.; Ribeirinho, V.S.; Andrade, C.A. Biochar-based nitrogen fertilizers: Greenhouse gas emissions, use efficiency, and maize yield in tropical soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 704, 135375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, K.L.A.; Galagar, T.F.C.; Esmeralda, P.C.A.; Saldo, I.J.P. Efficacy of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) derived biosorbent for nitrate removal in simulated water. Asian J. Phys. Chem. Sci. 2025, 13, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räbiger, T.; Andres, M.; Hegewald, H.; Kesenheimer, K.; Köbke, S. Indirect nitrous oxide emissions from oilseed rape cropping systems by NH3 volatilization and nitrate leaching as affected by nitrogen source, N rate and site conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 116, 126039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).