Abstract

This paper presents a numerical technique to approximate the Rayleigh–Stokes model for a generalised Maxwell fluid formulated in the Riemann–Liouville sense. The proposed method consists of two stages. First, the time discretization of the problem is accomplished by using the finite difference. Second, the space discretization is obtained by means of the predictor–corrector method. The unconditional stability result and convergence analysis are analysed theoretically. Numerical examples are provided to verify the feasibility and accuracy of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

Fractional calculus (FC) generalises the classical integer-order calculus [1,2]. In the last decade, FC has received considerable attention in a variety of scientific areas [3,4,5,6]. In most cases, it is difficult to compute an explicit solution to fractional differential equations, which has attracted researchers to look for accurate and efficient numerical approaches for solving these Equations [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

FC has successfully described viscoelastic fluid constitutive relations [15,16,17]. One usually starts the process of modelling viscoelastic fluids via fractional derivatives by modifying a traditional differential equation. This generalisation involves using the Riemann–Liouville (R–L) fractional derivative operator instead of the standard time derivative. Shen et al. [18] derived the Rayleigh–Stokes Equation (RSE) for a generalised fluid of the second grade flowing within a heated edge and over a heated flat plate. The analytic solutions for the temperature and velocity fields were obtained via the fractional Laplace and the Fourier sine transforms. Mainardi [19] provided a comprehensive review of the relationship between FC and viscoelastic models, linear viscoelasticity, and wave propagation. Qi and Xu [20] studied an unsteady flow of fractional Maxwell fluid in a channel. Xue and Nie [21] addressed the RSE to a heated generalised fluid of the second grade with fractional derivative flows inside a porous half-space.

In this paper, we investigate the numerical solution for the time fractional Rayleigh–Stokes Equation (TFRSE) including the time fractional derivative

with initial and boundary conditions (abbreviated as IC and BCs, respectively):

where represent the velocity field, the coefficients , and are positive constants, , is a source term, functions , , , and are prescribed and is the R–L fractional differential derivative of order denoted by

Some numerical techniques have been used to approximate the TFRSE Equation (1). Chen et al. [22] formulated an implicit finite difference (FD) algorithm. Wu [23] presented an implicit numerical approximation scheme. Jiang and Lin [24] proposed a numerical technique based on the method of reproducing kernel. Mohebbi et al. [25] adopted the compact FD method (CFDM) and radial basis function (RBF) meshless method (RMM). Zaky [26] and Shivanian et al. [27] used the Legendre–Tau and the meshless singular boundary methods, respectively. Hafez et al. [28] applied the Jacobi Spectral Galerkin method for the distributed TFRSE. Safari and HongGuang [29] adopted the improved dual reciprocity and singular boundary schemes for the TFRSE, while Golbabai et al. [30] proposed the local meshless RBF. Khan et al. [31] developed the high-order compact scheme, whereas Naz et al. [32] advanced a modified implicit scheme for the TFRSE.

This paper introduces a numerical method for the TFRSE and is organized as follows. Section 2 describes an algorithm to approximate the time fractional derivative of the TFRSE Equation (1). Section 3 accomplishes the space discretization with the help of the predictor–corrector method. Section 4 studies the unconditional stability result and convergence analysis of the proposed strategy by using Fourier analysis. Section 5 reports the numerical examples of the TFRSE and verifies the efficiency of the proposed scheme. Finally, Section 6 provides a concise conclusion.

2. The Time Discretization

Let us define where represents the time step size for We suppose that the solution has a continuous partial derivative for , and that the R–L fractional derivative can be evaluated using the Grünwald–Letnikov (G–L) formulation [33], described as

so that correspond to the coefficients of the generating function

where the coefficients and are the normalized G–L weights. The coefficients can be obtained recursively as:

The have some useful properties, as given by Lemma 1 ([33]).

Lemma 1.

The coefficients introduced in Equation (6) satisfy

Let us consider the following notations:

Now, we can formulate the semi-time discretization scheme for Equation (1) by means of the aforementioned relations

3. The Space Discretization

Let with , so that , represent the space steps in the x and y directions, respectively, and also and denote the total number of space steps in the x and y directions, respectively. Discretizing Equation (1) at the above grid points and by using

where

we obtain the following corrector formula as

such that

with representing the value of function f at The truncation error [22] is obtained as

and the predictor formula is denoted by

with the IC and BCs

respectively. We can adopt the following iterative procedure to approximate Equation (1) with Equations (2)–(4).

P: Predict some value for with

where is a very small number.

E: Evaluate the implicit part in Equation (12) with .

C: Correct to obtain a new for with

E: Evaluate the implicit part in Equation (12) with .

C: Correct with

⋮

The sequence of operations

determines for a sequence of values as

PECECECEC…

4. Theoretical Analysis of the Proposed Method

4.1. Stability Analysis

We now examine the stability of the proposed method Equation (19) by using Fourier analysis. Let and be the exact and the approximated solutions for in Equation (19). Then, the error can be defined as:

We can obtain for corrector formula

Let us introduce the following function:

such that

Then, can be approximated by using the Fourier series as

where

Applying Parseval equality for

Suppose that the difference Equation (20) has the following solution

where and Substituting Equation (22) into Equation (20) and simplifying leads to

such that

Now, we investigate the stability of the method Equation (19).

Theorem 1.

The predictor–corrector method Equation (19) is stable if and only if .

4.2. Convergence Analysis

Let us define the truncation error in the proposed method to satisfy the following form

From Lemma 3 in [25], we have

or

where . Subtracting Equation (12) from Equation (26), we get

where and

Let us consider the following two functions:

and

Then, and can by approximated by the Fourier series

in which

and

Moreover, we can obtain the values of and for as

and

Suppose that and have the following form

where

Substituting Equation (31) into Equation (28) gives

where and are as defined before. By virtue of the relations Equations (27) and (30), we get

Based on [22], it holds that

where .

Proposition 1.

Let denote the solutions of Equation (32). Then, we have

where .

Proof.

The principle of mathematical induction is applied by considering , which leads to

For , we obtain

Let us assume that

Then, based on Lemma in [25], we can conclude that

which completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.

The predictor–corrector method Equation (19) is convergent with the order

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents two numerical examples for illustrating the stability and accuracy of the proposed method with several values of and . For this aim, we compute the following maximum-norm error :

where v and V are the approximate and exact solutions, respectively. In addition, we evaluate the computational order in the time direction for the proposed method as:

where and represent the errors corresponding to time step with sizes and , respectively.

Example 1.

Let us consider the following TFRSE:

The IC and BCs as well as are determined from an exact solution

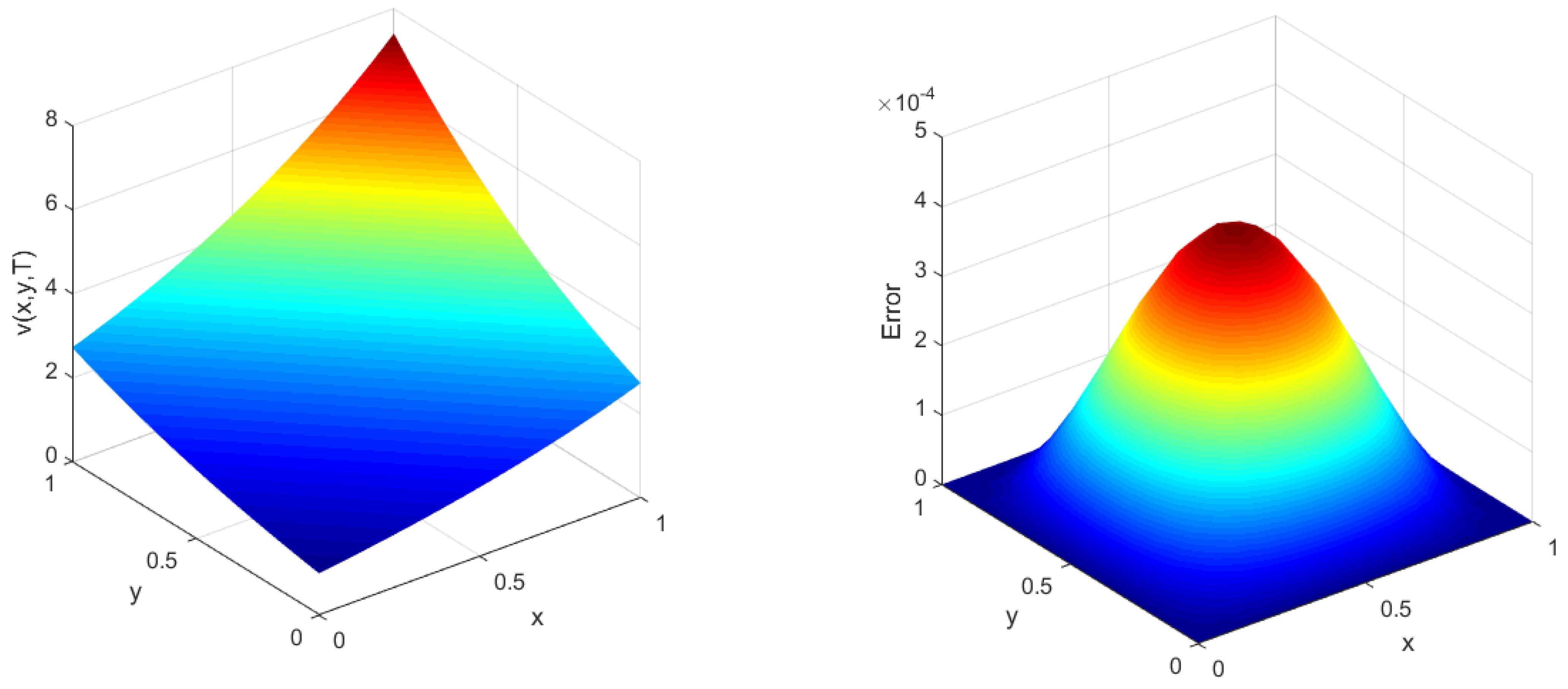

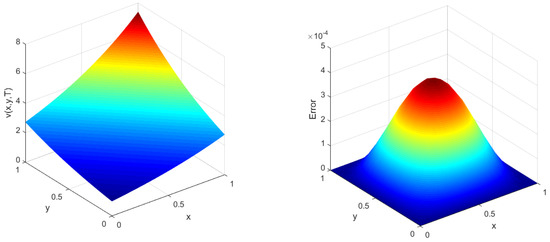

The proposed method is implemented for solving this problem when the total time with various values of and . Table 1 presents the maximum absolute errors , time convergence orders and execution times (in seconds) for , and various values of . We see that the obtained computational orders in time direction are close to the theoretical convergence rate, that is, Table 2 lists the maximum absolute errors in the solution for , and several values of and Table 3 compares the maximum absolute errors in the solution with those resulting from the method described in [25] for , and various values of Table 4 makes the comparison of errors in the solution with those resulting from the method in [25] for different values of , , and Table 5 compares the maximum absolute errors in the solution and execution times (in seconds) with those obtained with other schemes [22,25] for , and different values of . Figure 1 shows the approximate solution and the associated computational error of the proposed method with , , and .

Table 1.

The maximum absolute errors , time convergence orders and execution times (in seconds) of Example 1 for and and different values of .

Table 2.

The maximum absolute errors in the solution of Example 1 for , and different values of and .

Table 3.

The maximum absolute errors of Example 1 for , and different values of .

Table 4.

The maximum absolute errors and execution times (in seconds) of Example 1 for , and different values of and .

Table 5.

The maximum absolute errors of Example 1 for and and different values of .

Figure 1.

Approximate solution and the associated computational error of the proposed method with and and (left and right panels, respectively).

Example 2.

Consider the following TFRSE:

The IC and BCs as well as source term are achieved from an exact solution

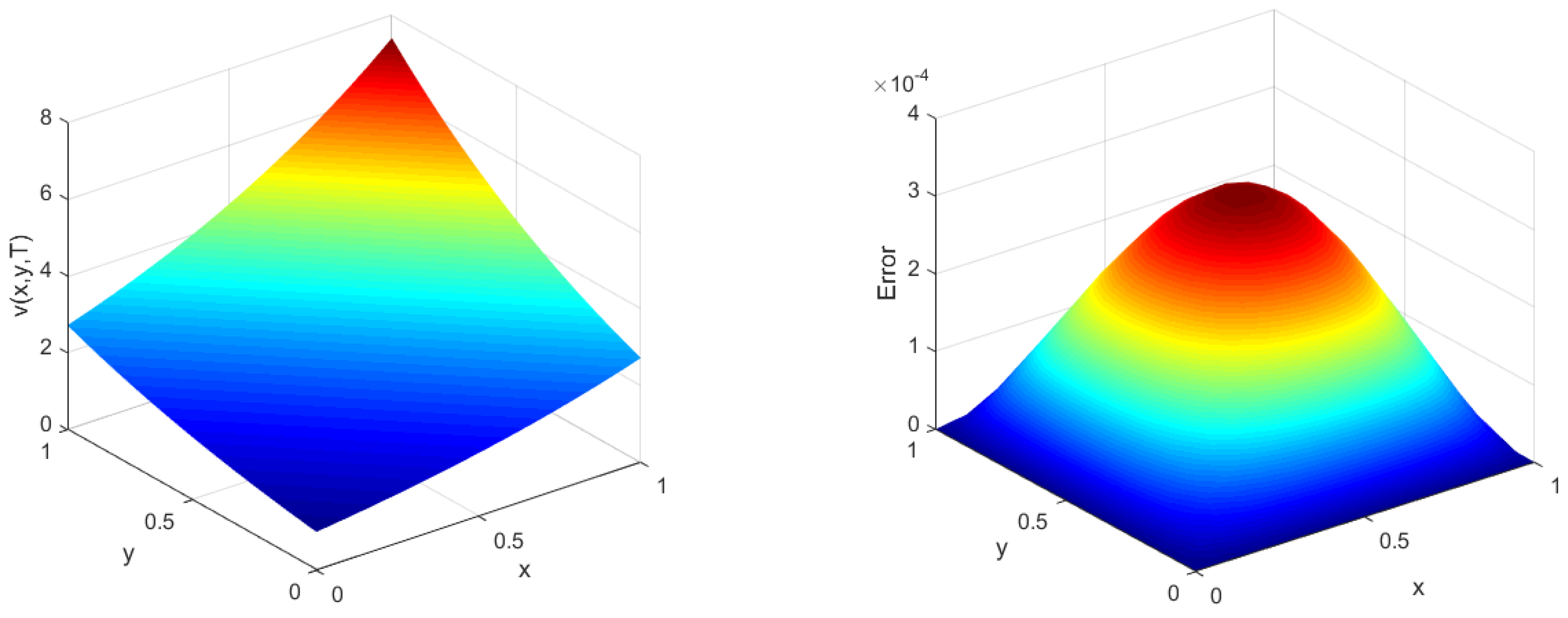

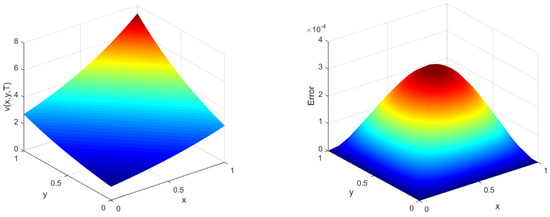

The proposed method is adopted for solving this problem when the total time with various values of and . Table 6 reports the maximum absolute errors and time convergence orders for , and various values of As shown in Table 6, the computational orders agree with the theoretical convergence order. Table 7 compares the maximum absolute errors in the solution for and several values of and Table 8 lists the maximum absolute errors in the solution for and several values of and Table 9 makes the comparison of the maximum absolute errors in the solution and execution times (in seconds) with those obtained with other schemes [22,25] for and and various values of . Figure 2 depicts the approximate solution and the associated computational error of proposed method with , , and .

Table 6.

The maximum absolute errors and time convergence orders of Example 2 for , and different values of .

Table 7.

The maximum absolute errors of Example 2 for and different values of and .

Table 8.

The maximum absolute errors of Example 2 for , and several values of and .

Table 9.

The maximum absolute errors and execution times (in seconds) of Example 2 for and and different values of .

Figure 2.

Approximate solution and the associated computational error of the proposed method with and and (left and right panels, respectively).

6. Concluding Remarks

We adopted the predictor–corrector method for approximating the TFRSE. First, the time discretization of the problem was accomplished by using the finite difference. Second, the space discretization was obtained with the help of the predictor–corrector method. The convergence and unconditional stability properties of the approach were discussed theoretically. Numerical experiments compared the results obtained with the proposed method and those produced using existing alternative schemes. The superiority of the new approach was thus verified and illustrated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.L. and O.N.; data curation, B.M. and L.D.L.; formal analysis, B.M., O.N. and Z.A.; investigation, L.D.L. and O.N.; methodology, B.M., L.D.L. and A.M.L.; software, B.M. and O.N.; supervision, Z.A. and A.M.L.; validation, B.M., O.N. and Z.A.; visualization, B.M. and O.N.; writing–original draft, B.M. and O.N.; writing–review and editing, Z.A. and A.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author Le Dinh Long is supported by Van Lang University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Milici, C.; Drăgănescu, G.; Machado, J.T. Introduction to Fractional Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, K.; Bohannan, G.; Caponetto, R.; Lopes, A.M.; Machado, J.A.T. Fractional-Order Devices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, F.; Qu, J.; Chai, Y.; Chen, L.; Lopes, A.M. Synchronization of incommensurate fractional-order chaotic systems based on linear feedback control. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, R.; Lopes, A.M.; Ge, S. Leader-follower non-fragile consensus of delayed fractional-order nonlinear multi-agent systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 414, 126688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, J.; Agrawal, O.P.; Machado, J.T. Advances in Fractional Calculus; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R.E.; Rosário, J.M.; Tenreiro Machado, J. Fractional order calculus: Basic concepts and engineering applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2010, 2010, 375858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikan, O.; Avazzadeh, Z. Numerical simulation of fractional evolution model arising in viscoelastic mechanics. Appl. Numer. Math. 2021, 169, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Xu, D.; Guo, J.; Zhou, J. A time two-grid algorithm based on finite difference method for the two-dimensional nonlinear time-fractional mobile/immobile transport model. Numer. Algorithms 2020, 85, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Qiu, W.; Guo, J. A compact finite difference scheme for the fourth-order time-fractional integro-differential equation with a weakly singular kernel. Numer. Meth. Part Differ. Equ. 2020, 36, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnam, B.; Esmaeelzade Aghdam, Y.; Nikan, O. Numerical investigation of the two-dimensional space-time fractional diffusion equation in porous media. Math. Sci. 2021, 15, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Xu, D.; Guo, J. The Crank-Nicolson-type Sinc-Galerkin method for the fourth-order partial integro-differential equation with a weakly singular kernel. Appl. Numer. Math. 2021, 159, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, Y.E.; Mesgrani, H.; Javidi, M.; Nikan, O. A computational approach for the space-time fractional advection–diffusion equation arising in contaminant transport through porous media. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 3615–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Xu, D.; Guo, J. Numerical solution of the fourth-order partial integro-differential equation with multi-term kernels by the Sinc-collocation method based on the double exponential transformation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 392, 125693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikan, O.; Avazzadeh, Z.; Machado, J.T. Numerical approach for modeling fractional heat conduction in porous medium with the generalized Cattaneo model. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 100, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenchang, T.; Wenxiao, P.; Mingyu, X. A note on unsteady flows of a viscoelastic fluid with the fractional Maxwell model between two parallel plates. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2003, 38, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Nadeem, S.; Asghar, S. Periodic unidirectional flows of a viscoelastic fluid with the fractional Maxwell model. Appl. Math. Comput. 2004, 151, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, N. Fractional calculus description of non-linear viscoelastic behaviour of polymers. Nonlinear Dyn. 2004, 38, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Tan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Masuoka, T. The Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivative model. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2006, 7, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity: An Introduction to Mathematical Models; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Xu, M. Unsteady flow of viscoelastic fluid with fractional Maxwell model in a channel. Mech. Res. Commun. 2007, 34, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Nie, J. Exact solutions of the Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid in a porous half-space. Appl. Math. Model. 2009, 33, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Liu, F.; Anh, V. Numerical analysis of the Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivatives. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 204, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C. Numerical solution for Stokes’ first problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivative. Appl. Numer. Math. 2009, 59, 2571–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jiang, W. Numerical method for Stokes’ first problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivative. Numer. Methods Partial. Differ. Equations 2011, 27, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A.; Abbaszadeh, M.; Dehghan, M. Compact finite difference scheme and RBF meshless approach for solving 2D Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivatives. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2013, 264, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.A. An improved tau method for the multi-dimensional fractional Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid. Comput. Math. Appl. 2018, 75, 2243–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanian, E.; Jafarabadi, A. Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second grade fluid with fractional derivatives: A stable scheme based on spectral meshless radial point interpolation. Eng. Comput. 2018, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, R.M.; Zaky, M.A.; Abdelkawy, M.A. Jacobi Spectral Galerkin method for Distributed-Order Fractional Rayleigh-Stokes problem for a Generalized Second Grade Fluid. Front. Phys 2020, 7, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, F.; Sun, H. Improved singular boundary method and dual reciprocity method for fractional derivative Rayleigh–Stokes problem. Eng. Comput. 2020, 37, 3151–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikan, O.; Golbabai, A.; Machado, J.T.; Nikazad, T. Numerical solution of the fractional Rayleigh–Stokes model arising in a heated generalized second-grade fluid. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ali, N.H.M. High-order compact scheme for the two-dimensional fractional Rayleigh–Stokes problem for a heated generalized second-grade fluid. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Ali, U.; Elfasakhany, A.; Ismail, K.A.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A. An Implicit Numerical Approach for 2D Rayleigh Stokes Problem for a Heated Generalized Second Grade Fluid with Fractional Derivative. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuste, S.B. Weighted average finite difference methods for fractional diffusion equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2006, 216, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).