Abstract

Preeclampsia is one of the illnesses associated with placental dysfunction and pregnancy-induced hypertension, which appears after the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and is marked by proteinuria and hypertension. It can affect pregnant women and limit fetal growth, resulting in low birth weights, a risk factor for neonatal mortality. Approximately 10% of pregnancies worldwide are affected by hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. In this review, we discuss the machine learning and deep learning methods for preeclampsia prediction that were published between 2018 and 2022. Many models have been created using a variety of data types, including demographic and clinical data. We determined the techniques that successfully predicted preeclampsia. The methods that were used the most are random forest, support vector machine, and artificial neural network (ANN). In addition, the prospects and challenges in preeclampsia prediction are discussed to boost the research on artificial intelligence systems, allowing academics and practitioners to improve their methods and advance automated prediction.

1. Introduction

Placental dysfunction-related disorders (PDDs), such as preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction, require that a referral choice be made quickly. Preeclampsia is the world’s most common cause of maternal death and morbidity [1]. It is a hazardous medical condition that can develop about halfway through gestation (after 20 weeks) and is associated with substantial mortality and morbidity for the mother, the fetus, and the newborn [2]. It is a pregnancy complication that affects from 3% to 7% of all pregnant women, whether in their first or subsequent pregnancies, and is identified by new-onset proteinuria and gestational hypertension, usually by the last trimester of pregnancy [3]. The disease impacts mothers and limits fetal growth, resulting in low birth weights, a risk factor for neonatal mortality [4]. The symptoms of preeclampsia include swelling, blurred vision, headaches, high blood pressure, protein in the urine [2], and stress on the mother’s heart and other organs. It also affects the mother’s blood supply to the placenta, weakens kidney and liver functions, causes fluid build-up in the lungs, and causes other serious complications [5].

Preeclampsia occurs in approximately 5.37 out of every 10,000 women in Saudi Arabia [2]. It can result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes, such as neurological consequences for the newborn. The pathogenesis and etiology of preeclampsia are still unknown, and delivery is the only possible treatment for a pregnant woman diagnosed with preeclampsia. However, to avoid difficulties and improve outcomes, it is critical to detect preeclampsia risk before pregnancy [6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the study of concepts that can be used to build machines capable of thinking, judging, and intending in accordance with standard human reactions to stimulation. Systems that integrate powerful software, hardware, knowledge-based processing models, and extensive databases to simulate the characteristics of efficient human decision making are defined as AI. AI is employed in many industries, including scientific research, medical prognosis, robot control, and law [7].

AI in the medical field may be divided into virtual and physical categories. The physical category focuses on assisted surgical robots, intelligent prosthetics for the disabled, and geriatric care. The virtual component includes tools such as a neural network-based treatment decision support and electronic health record systems. It also includes machine learning (ML), which relies on mathematical algorithms that enhance learning via experience [8].

ML is crucial for helping the model learn and adjust based on the input data without being explicitly programmed. It is the concept of providing machines with the capability to learn and understand data, recognize patterns, and make predictions or decisions [9]. Therefore, ML can be trained to identify patterns in the same way that doctors do. It can help diagnose or predict diseases, recognize patient risk factors, and promote the research and development of new drugs. It is beneficial in situations in which the diagnostic data a doctor looks at has already been digitized. Such situations include using computerized tomography scans to detect lung cancer or strokes, analyzing cardiac magnetic resonance images and electrocardiograms to determine the likelihood of sudden cardiac death or other heart conditions, examining eye images for signs of diabetic retinopathy, and classifying skin lesions on the basis of skin imaging data. An example of success in these fields is a study by Bhatia et al. [10], which proposed a method for detecting lung cancer using deep residual networks for feature extraction, achieving an accuracy of 84%.

Data are the basis for ML models, and, when high-quality data are abundant, algorithms can diagnose on par with professionals. The key differences are the algorithms’ ability to make conclusions in a split second and their ability to be readily replicated anywhere around the globe. The aim is that all people, wherever they are, can access affordable and top-quality diagnostic services.

Deep learning (DL) is a form of AI that can tackle complex problems that may be challenging or even impossible for traditional AI techniques to solve. One of the key benefits of DL is its ability to utilize both labeled and unlabeled data during training, which enables it to effectively handle diverse information and learn from it. Additionally, DL is well suited for working with large datasets; therefore, its applications are likely to expand in the future. Many recent studies have demonstrated the capabilities of DL technologies, including the ability to learn from complex data, perform image recognition, and categorize text [11]. In a study by Tahir et al. [12], the researchers aimed to use a neural network (NN) [13] to estimate the probability of preeclampsia and compared its performance to other algorithms such as naïve Bayes (NB) and linear regression. They also tested the NN with one hidden layer and found that using 17 neurons resulted in the lowest error rate. The model was then validated using three different methods and was found to have the best performance, with an accuracy of 96.66%, when validated using the leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation method.

This paper provides an in-depth review of the most recent studies on several preeclampsia prediction methods that use clinical data and employ DL and ML. Twenty-five articles released since 2018 are tabulated, grouped, and analyzed from many angles, including ML and DL models, dataset size, and performance. Key search terms such as “preeclampsia”, “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, and “deep learning” were used to identify relevant studies for inclusion in this review. The primary aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in the realm of automated preeclampsia prediction. Furthermore, this review aims to delve into the challenges and opportunities in the field of preeclampsia research.

The remainder of this work is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the studies that used statistical, ML, and DL methods to predict preeclampsia. Section 3 discusses the most widely used algorithms and data types. Section 4 presents the challenges and opportunities in preeclampsia prediction. Lastly, Section 5 provides the conclusion.

2. Related Study

2.1. Predicting Preeclampsia Using General Approaches

Some studies were performed using general statistical techniques to predict preeclampsia. A study conducted by Rokotyanskaya et al. [6] in Russia in 2020 aimed to create tools for the prediction of the onset of preeclampsia using molecular–genetic and biomedical indicators and individual risk assessments using 12 features from a sample of 457 pregnancies between 22 and 36 weeks of gestation. The LR method and Open Epi system were used to determine risk characteristics after retrospectively analyzing the gestation course and labor outcomes. The study developed a system to predict the preeclampsia that have an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.733.

Additionally, in prospective observational research in 2020, Soongsatitanon et al. [14] assessed the predictive value of uterine artery (UA) Doppler, pulsatility index (PI), and serum placental protein 13 (PP13) levels in the first trimester for preeclampsia. Fifteen characteristics were gathered for the study from a sample of 353 pregnant women at the Faculty of Medicine’s Obstetrics and Gynecology division at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, Thailand. The data from the UA Doppler and PP13 tests were statistically analyzed using the SPSS software program to determine their predictive values. According to the study’s findings, UA, PI, and serum PP13 levels together had the best accuracy in predicting preeclampsia, resulting in a negative predictive value (NPV) of 94.4%, a specificity of 62.9%, a sensitivity of 58.6%, and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 12.4%.

Furthermore, Serra et al. [15] developed a multivariate Gaussian distribution model for the first trimester incorporating biophysical/biochemical data and maternal characteristics to examine the efficacy of screening for early-onset preeclampsia (eoPE) in a routine care low-risk scenario in 2020. The dataset included 13 features from 6893 general population singleton deliveries at the Vall d’Hebron and Dexeus University Hospital in Spain. Three steps were taken to construct the screening model for preeclampsia: multiple of median calculation, prior risk definition, and posterior risk definition. The researchers found that the best detection rate was demonstrated by combining the biophysical parameters, maternal traits, and placental growth factor (PlGF), as this attained a detection rate of 94% for a 10% false-positive rate (FPR) and a detection rate of 59% for a 5% FPR (AUC 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.94–0.98). The detection rate increased from 59% to 94% upon including PlGF in the biophysical indicators.

Moreover, Byonanuwe et al. [16] conducted prospective cohort research in the Cuban teaching hospital Carlos Manuel de Cèspedes in a group of 178 women with preeclampsia while monitoring their chronic hypertension at 12 weeks after delivery. After birth, the women’s placentas were examined for any abnormalities, including villositary infarcts, endarteritis, Tenney–Parker changes, intervillositary thrombus, meconium, chorioamnionitis, decidual necrosis, and hypermaturity. The study’s aim was to use the placentas of patients who had just given birth to determine the histological factors associated with this chronic hypertension. Women with chronic renal illness or those who had preeclampsia or could not follow up were excluded from the study. Therefore, from the original sample of 178 cases, data analysis was accomplished for 162 cases. Following the delivery of the baby, participants had their blood pressure checked again. If it was still high, they were deemed to have chronic hypertension. Cox’s multivariate model analysis detected placental histopathological findings that were associated with chronic hypertension: villositary infarcts, chorioamnionitis, endarteritis, and intervillositary thrombus. For villositary infarcts, the hazard ratio (HR) was 1.657 (95% CI: 1.264–2.848), with a p-value of 0.048. Meanwhile, chorioamnionitis had an HR of 1.697 (95% CI: 1.443–3.416), with a p-value of 0.038, while endarteritis had an HR of 1.242 (95% CI: 1.115–1.804), with a p-value of 0.025. Lastly, the intervillositary thrombus had an HR of 1.529 (95% CI: 1.231–3.197), with a p-value of 0.020.

In addition, Modak et al. [17] conducted a study in the obstetrics and gynecology departments at the RG Kar Medical College, Kolkata, and Burdwan Medical College, Burdwan, West Bengal, India. The study was conducted in a population of 116 expectant women who were chosen according to various inclusion and exclusion criteria; hence, the outliers in the data were excluded. The study goal was to estimate the efficacy of using UA doppler and urine protein creatinine ratio (UPCR) measured at the beginning of pregnancy in predicting the development of preeclampsia and to compare the precision of the two techniques. At the time of enrollment, patients underwent screening for a spot UA Doppler and UPCR. They were also monitored up to delivery by blood pressure monitoring and clinical examination to look for preeclampsia. Spot midstream urine samples were obtained and analyzed in an ERBA semiautomatic biochemistry analyzer using the immunoturbidimetric micro albumin method to estimate protein and a modified Jaffe’s method to measure creatinine. Individuals with a UPCR ratio of 35.5 mg/mmol or greater were deemed to have tested positive. All the data were statistically analyzed, and the effectiveness of the screening test was assessed using the ROC curve, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. Women with preeclampsia had a high median UPCR (44.8 mg/mmol) compared to unaffected women (26.6 mg/mmol). A cutoff of 35.5 mg/mmol was selected as the optimal spot UPCR cutoff value to detect preeclampsia, and, using this cutoff, the test had a specificity of 94.06%, a sensitivity of 80%, an NPV of 96.94%, and a PPV of 66.76%. The AUC for spot UPCR was 0.949 (95% CI: 0.891–1.000). When using a mean UA resistance index of more than 0.7 to identify preeclampsia, the specificity was 97.03%, the sensitivity was 60%, the NPV was 94.23%, and the PPV was 75%. The AUC was 0.856 (95% CI 0.742–0.971). Preeclampsia could be predicted with 92.24% accuracy using a combination of spot UPCR and UA Doppler. Table 1 shows a summary about all related studies using general approaches.

Table 1.

Summary of related studies using general approaches.

2.2. General Approaches for Predicting Preeclampsia

Machine Learning Based Model for Predicting Preeclampsia

Numerous studies have used ML techniques to predict preeclampsia. Marić et al. [18] constructed an ML model for the early prognosis of preeclampsia that automatically chooses the most relevant features out of all the variables. In addition, statistical learning methods were used to analyze routine prenatal visit data to generate a prediction tool that could be made available to all pregnant women and could be used to identify high-risk patients from an initial screening. The dataset was collected from 16,370 deliveries between April 2014 and January 2018 at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in California. The prediction model was built using two statistical learning algorithms: gradient boosting and elastic net. The models took into account 67 factors, including medicine intake, routine, medical records, and prenatal laboratory outcome. The AUC, true positive rate (TPR), and FPR were assessed using cross-validation. The prediction model was created by combining a selection of the most useful features from all variables. The elastic net algorithm attained the optimal results: the AUC was 0.79 (95% CI 0.75–0.83), the FPR was 8.1%, and the sensitivity was 45.2%. The sample also included 98 cases of eoPE (1.9%). The performance metrics for the elastic net prediction model for eoPE were an AUC of 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.95), a TPR of 72.3%, and an FPR of 8.8%.

Furthermore, Jhee et al. [19] used data from hospital electronic medical records for the prediction of late-onset preeclampsia. The dataset was collected from Yonsei University Hospital and included 11,006 pregnant women. Early-second-trimester to 34 week maternal data were gathered from electronic medical records. The prediction models’ parameters were selected using cluster analysis and pattern recognition. The prediction models were developed with LR, the decision tree (DT) model, the random forest (RF) algorithm, stochastic gradient boosting (SGB), support vector machine (SVM), and the NB classification method. To evaluate the models’ performance, C-statistics were used. The C-statistics for the RF algorithm, LR, the DT model, SVM, NB classification, and the SGB method were 0.894, 0.806, 0.857, 0.573, 0.776, and 0.924, respectively. The best performance was achieved by the SGB model, which had an FPR and accuracy of 0.009 and 0.973, respectively.

Additionally, Marin et al. [20] aimed to use ML algorithms to help predict preeclampsia using information about the pregnant woman, such as blood pressure, age, and weight medical data. The researchers used the Viterbi ML algorithm, with which significant links between nodes in several datasets can be discovered; it would be challenging to do so otherwise. In addition, with the medical information given, the algorithm uses a built-in computer program to estimate the probability of developing an illness. Participants in the study wore a smart bracelet containing a sensor, as well as electronic and wireless communication modules (the i-bracelet system). When the user pairs the bracelet with a mobile, the blood pressure readings are sent to the mobile via Bluetooth. The Viterbi algorithm was used to determine whether the pregnant women who wore the bracelets had preeclampsia. The most likely path was chosen using a set of hidden states in a hidden Markov model. A total of 105 individuals participated, and the overall accuracy was 80%, with a specificity of 72% and sensitivity of 92.5%.

Moreover, Liu et al. [21] constructed prediction models for preeclampsia by analyzing all clinical and laboratory information obtained during early pregnancy prenatal screening using ML approaches. The dataset they used contained medical records for 11,152 pregnant women collected from Hospital of Jinan University between December 2015 and September 2019. Among them, 143 had preeclampsia, 95 had gestational hypertension (GH), and 10,914 had neither preeclampsia nor GH. The study used five ML approaches to predict preeclampsia: LR, SVM, deep neural network (DNN), DT, and RF. In addition, 18 variables were contained in the model, including prenatal laboratory results, parental characteristics, ultrasound results, and medical history. Cross-validation was used to evaluate calibration, discrimination, and AUC. The highest accuracy was displayed by the RF model, which had an accuracy of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.74–0.75) and a recall rate of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.41–0.44). The AUC of the RF model was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.80–0.92), the precision was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.79–0.84), and the Brier score was 0.17 (95% CI: 0.17–0.17).

In addition, Li et al. [22] developed a prediction model using five ML algorithms: RF, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), LR, and SVM. The features that contributed most to the prediction model were identified with XGBoost. The performance of the ML model to anticipate pregnancies at risk of preeclampsia was evaluated on the basis of accuracy, F1 score, recall, precision, false negative score, AUC, and Brier score. The study included 3759 pregnant women who received prenatal care at Xinhua Hospital in July 2016 and December 2019. The best prediction performance achieved by the XGBoost model had an AUC of 0.955, an f1_score of 0.571, a recall of 0.789, a precision of 0.447, and an accuracy of 0.920.

Carreno et al. [23] used a comparative strategy to assess the utility of time-series summary methods and feature size reduction methods in preeclampsia prognosis. A public dataset was used in this research, and it was segmented into two cohorts, the Stanford dataset and the Detroit dataset. The data consisted of a large set of features, which made it challenging for ML algorithms. Thus, two algorithms were used to reduce feature size: the imperialist competitive algorithm was used for feature selection, and feature clustering was implemented through the sample progression discovery (SPD) algorithm. Further obstacles faced involved patients being sampled at various nonuniform timepoints. This presented difficulties in cross-patient comparison. However, this issue was solved using two methods, a simple time average summary and a three-point time series. Since the Detroit set was four times larger than the Stanford set, the training procedure employed tenfold cross-validation. Meanwhile, the Stanford set employed fivefold cross-validation. The study used two classifiers mentioned above, RF and SVM. The performances of the four approaches were measured with AUC, which ranged from 85% to 93%. However, the SVM algorithm paired with SPD for feature clustering obtained the highest accuracy, peaking at 93%. A limitation of this research was the sparse dataset, as it was lacking data from at least one trimester for over half of the patients. However, the researchers overcame this with summarizing methods.

Similarly, Martínez-Velasco et al. [24] used common ML algorithms to estimate the occurrence of preeclampsia. These included RF, SVM, Bayesian networks, NN, NB, C4.5-like trees, logistic model trees, C5.0, boosted logistic regression, and multivariate adaptive regression spline. The dataset used in this study included 25 parameters. Missing data were handled by replacing the missing values with the average. Eventually, RF along with the LOO cross-validation method was found to have the highest accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity, which were 0.8530, 0.8614, and 0.6846, respectively. The researchers also aimed to optimize interpretability using RF by extracting the significance of a factor using the MDGI metric and visualizing the most relevant factors through a DT.

Likewise, Bosschieter et al. [25] focused on explainable boosting machines (EBMs) in their study, comparing this method to other black-box ML methods such as RF and XGBoost for different maternal diseases. The OBCOAP of the Foundation for Healthcare Quality provided the dataset, and 2.05% of the patients were diagnosed with preterm preeclampsia. EBMs were used to add interpretability and demonstrate the highest risk contributors, which were body mass index, number of previous stillbirths, and pre-pregnancy hypertension. The training process utilized fivefold cross-validation, and, among all methods, the outcomes showed that EBMs were the most accurate method, with an AUC of 0.770 ± 0.006 for preeclampsia.

Similarly, Schmidt et al. [26] researched developing and training ML models for predicting unfavorable outcomes in patients suspected of having preeclampsia. The dataset included 2472 pregnancies of women treated at the Obstetrics Department at Charité—Universitätsmedizin in Germany between July 2010 and March 2019. The use of novel biomarkers such as soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt1) and other parameters resulted in 114 features. The ML algorithms used were an RF classifier and a gradient-boosted tree (GBTree), and the researchers investigated various techniques to compare the ML model’s outcome with a clinical methodology defined by sFlt1-to-PlGF ratio-derived metrics and standard of care metrics. A 10 × 10-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate the approach’s result. The GBTree had an NPV of 89% ± 3%, a specificity of 97% ± 2%, a PPV of 88% ± 6%, a sensitivity of 66% ± 5%, and an overall accuracy of 89% ± 3%. The RF classifier had the same PPV as the GBTree (88% ± 6%) and a specificity of 97% ± 1%, while it performed marginally worse on the other criteria.

In addition, Sufriyana et al. [27] aimed to develop an ML model of PDD using a sample of 95 women and considering 13 features from a public dataset in the Mendeley Data repository from a study conducted at Ljubljana University Medical Center. The best model was selected either automatically or manually. Weka 3.8.3 was used to develop the automatic selection models. Additionally, the researchers manually picked the top 23 white-box models. From the automatic selection, the optimum model was the RF model, with an accuracy of 92.6%. The white-box models were the models that were manually selected: classification via regression (CVR), NB, simple logistic, logistic model tree, multi-class classifier, and LR. With the RF model automatically selected as the black-box model, the researchers manually selected CVR as the optimum white-box model, which had an accuracy of 90.6%. Furthermore, the validation of the models was repeated using tenfold cross-validation. In conclusion, the model that performed predictably well when categorizing women with PDDs compared to a control group was the CVR model. Moreover, it distinguished women with PDDs from a control group without additional pregnancy-related hypertension subtypes.

Another study [28] developed a model using AI to predict preeclampsia using a dataset from a health insurance company called BPJS Kesehatan in Indonesia. Including all women with one pregnancy, using a nested case–control approach, the BPJS Kesehatan dataset consisting of 95 features was preprocessed to separate 3318 cases of preeclampsia/eclampsia and 19,883 cases of normotensive pregnant women. Six algorithms were tested: SVM, ensemble, ANN, ML-optimized LR, DT, and RF. The AUC was used to compare the algorithms, and the results indicated that the best model had 17 predictors from the RF algorithm. The best AUC was achieved using data from the 9 to 12 months leading up to the event using either temporal split for external validation (0.86, 95% CI: 0.85–0.86) or geographical split for external validation (0.88, 95% CI: 0.88–0.89).

Likewise, in 2022, a study was conducted by Zhang et al. [29] to investigate the relationship between patient blood data features and severe preeclampsia. The sample comprised medical records from 248 patients from Sichuan Second University Hospital in West China, each of which consisted of 10 features. Two bivariate tests were carried out during exploratory data analysis: the Student’s t-test for normal distributions and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normal distributions. Fisher’s exact test was then applied whenever necessary. For multiple comparisons, the significance level was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. Three methods for predictive modeling were constructed: RF, light gradient boosting machines (LightGBM), and DT. By combining maternal features and metrics from standard blood tests in a predictive model, the research produced a new technique for early screening of severe preeclampsia. Lastly, the LightGBM model, which relies on activated partial thromboplastin time ratio, aspartate aminotransferase, and direct bilirubin, had a sensitivity of 88.37%, an AUC of 89.74%, a specificity of 77.27%, and a PPV of 65.96% for predicting severe preeclampsia.

Lin et al. [30] gathered data from eight clinical sites throughout the United States to perform an observational cohort study in which ML was implemented. It aimed to develop bias-free ML classifiers that can aid in early pregnancy screening by combining most of the previously recognized risk variables and indications of preeclampsia with eclampsia (E) and preeclampsia with severe features (sPE). The assessment involved a plethora of information gathered for nulliparous individuals throughout four visits, including a birth visit and three visits that generally corresponded to the first through third trimesters (Vi4 and Vi1–Vi3, respectively). Maternal serum was collected at Vi1 and Vi2 to fully explore the association between a range of adverse pregnancy outcomes and placental analytes. The methods utilized to obtain results were RF, LR, XGBoost, and SVM. The best performance for early sPE compared to late sPE + E RF models yielded an AUC of 0.63 ± 0.11 for Vi1, 0.79 ± 0.11 for Vi2, 0.83 ± 0.08 for Vi3, and 0.84 ± 0.09 for Vi4.

Villalaín et al. [31] aimed to create a model utilizing ML techniques to predict whether a delivery would occur within 7 days of diagnosis (model B) or abruptio placentae (model SA) or the risk of developing hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome. To develop models B and SA, a mono-objective genetic algorithm was implemented. However, during eoPE diagnosis, maternal characteristics and data were gathered, including platelets, creatinine, transaminases, ultrasound data, and angiogenesis biomarkers such as PlGF. Basal models that included patient demographics (B1, SA1), and enhanced models that added data available at eoPE diagnosis (B2, SA2) were created. Several methods were used, including a genetic algorithm, mono-objective, missForest imputation, the K-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm, DT, Gaussian naïve Bayes, and SVM. By applying 13 variables, KNN performed the best at predicting the B1 basal model, with a precision of 0.68 ± 0.09, a specificity of 71.4%, a sensitivity of 63.6%, an NPV of 65.2%, and a PPV of 70%, while, for SA1, the precision was 0.77 ± 0.09, the specificity was 80%, the sensitivity was 60.4%, the NPV was 87.9%, and the PPV was 50%. In addition, SVMs with 18 variables were better able to develop models at diagnosis, with B2 having a precision of 0.79 ± 0.05, 80.1% specificity, 77.3% sensitivity, 76.2% NPV, and 81.5% PPV, and SA2 having a precision of 0.79 ± 0.08, 82.8% specificity, 66.7% sensitivity, 90.3% NPV, and 51.6% PPV. Table 2 shows a summary of all related studies using machine learning.

Table 2.

Summary of related studies using machine learning.

2.3. Deep Learning Based Model for Predicting Preeclampsia

Tahir et al. [32] aimed to implement NN to estimate the probability of preeclampsia on par with other algorithms such as NB and linear regression. The dataset was retrieved from Surabaya Haji General Hospital and consisted of 239 samples, taking 17 risk factors into account. To optimize the results, the researchers tested the neuron model with one hidden layer to determine the number of neurons with the smallest error rate, which was 17 neurons. Lastly, the model was validated and compared using three validation methods. NN had the best performance, with 96.66% accuracy, after being validated using the LOO cross-validation method.

Similarly, Sakinah et al. [33] adopted a variant of recurrent NN, which is long short-term memory (LSTM). The optimum combination of several parameters must be found to obtain an accurate prognosis using this method. Time series patterns count of neurons in the hidden layers, maximum epochs, and the combination of training and testing data were among these parameters. Thus, adaptive moment estimation (ADAM) optimization was utilized in the LSTM network during the process of learning, where it finds the optimum weight values to gain the minimum system error rate. The validation methods used in this study were LOO cross-validation and tenfold cross-validation. The dataset was retrieved from Haji General Hospital in Surabaya. The best accuracy rates were obtained for the training data (96.62%) and the testing data (90.22%). These percentages were attained using a combination of the LOO cross-validation approach, 30 hidden neurons, a maximum number of epochs of 100, and a single parameter series pattern.

Additionally, Tahir et al. [12] aimed to determine how well DL and NN algorithms predicted the risk of preeclampsia in expectant mothers. From December 2017 to February 2018, 17 parameters were gathered from 1077 patient records at two hospitals in Makassar, as well as the Haji General Hospital in Surabaya. The experiment used two data types: the original data using 17 features and the data using the feature selection algorithm Particle swarm optimization (PSO), which uses seven features. The methods used in the study were rule induction, DL, SVM, DT, NN, NB, and KNN. After comparison, DL showed higher accuracy than the other methods for both data types. DL using the original data resulted in 95.12% accuracy, but with PSO data, its accuracy was 95.68%. Therefore, the accuracy of DL with PSO data was better than that of DL with the original data.

Furthermore, in 2021, to identify patients with preeclampsia syndrome and its associated risk factors, Manoochehri et al. [34] proposed developing a data mining-based model as a screening tool. The sample was medical records of 1452 pregnant women, each with nine features, in Hamadan City, Iran, from April 2005 to March 2015. The research involved six data mining techniques: RF, LR, discriminant analysis, KNN, SVM, and C5.0 DT. The results indicated that the most significant risk variables for detecting preeclampsia were the number of pregnancies, age, and the pregnancy season; among the six data mining methods, the highest prediction accuracy was 0.791, which was achieved by the SVM model.

In addition, Han et al. [35] studied medical data from 568 women who received hospital care in the Obstetrics Department at Fujian Maternal and Child Health Hospital. The sample included pregnancies with preeclampsia, normal-term pregnancies, and pregnancies with GH from September 2014 to September 2018. In this sample, 216 women were diagnosed with preeclampsia, 136 women were diagnosed with GH, and 216 women had neither preeclampsia nor GH. The aim was to determine the most reliable indicators of preeclampsia using a backpropagation (BP) NN. The researchers used TensorFlow software to build a three-layer BP NN with 25 features that were considered the input of the network nodes. For the output, there were three sample types to examine the relevant aspects affecting preeclampsia. The weight values (W1) that were related to the input layer neuron nodes were produced after the NN model had been trained, and the correlation of the influencing factors was established in accordance with the magnitude of the weights. In conclusion, the BP NN identified albumin, mean platelet volume, blood urea nitrogen, lactate dehydrogenase, and triglyceride as the strongest preeclampsia predictors. Moreover, the NN showed 78.8% accuracy.

Bennett et al. [36] used huge data resources from the Public Use Data Files (PUDF) for Texas, the Magee Obstetric Medical and Infant (MOMI) database, and the Oklahoma PUDF. This study aimed to achieve early prediction of preeclampsia using ML and the cost-sensitive deep neural network (CSDNN) [13] method. To investigate the efficiency of multiple network architecture, Hyperband, Bayesian optimization, and random search hyperparameter optimization algorithms were used. To estimate CSDNN performance, it was compared with SVM with linear kernel (SVM-Lin), LR, and SVM with radial basis function (SVM-RBF), in addition to cost-sensitive versions of each algorithm. The CSDNN with focal loss (CSDNN-FL) was the best-performing model for the Oklahoma and Texas datasets, with AUCs of 64% and 66%, respectively. For the MOMI dataset, CSDNN-FL and CSDNN with the loss function weighted cross-entropy (CSDNN-WCE) performed better than other approaches, producing an AUC of 76%. Although WSVM-RBF, CSDNNs, and WLR resulted in the highest G-mean values, the AUC for Native Americans in Texas was 57.1% and the AUC for African Americans in Texas was 66.7%. The best results for Oklahoma Native Americans were obtained using DNN and balanced batch, with an AUC of 58%, while the best results for Oklahoma African Americans were achieved using CSDNN-WCE (AUC 62.3%) and the best results for the MOMI African American dataset were obtained using either CSDNN-FL utilizing a balanced batch approach or CSDNN-WCE. Table 3 shows a summary of all related studies using deep learning.

Table 3.

Summary of related studies using deep learning.

3. Discussion

This review assessed the latest research on general methods, ML, and DL for preeclampsia prediction. Our goal was to define the data types and techniques that were employed in preeclampsia prediction, as well as the methods that delivered meaningful outcomes. In this section, the data used for the prediction of preeclampsia, the algorithms used, and the limitations of the reviewed studies are discussed.

Examination of the studies revealed that preeclampsia was predicted using a variety of data sources, including clinical data, questionnaires, and laboratory test data. Most of the studies that predicted preeclampsia with high accuracy used clinical information, such as maternal and gestational age, blood pressure, height, weight, and history of preeclampsia and hypertension. However, the best studies used mean arterial pressure, proteinuria, creatinine, and PI. Jhee et al. [19] used the combination of maternal factors and common antenatal laboratory data from the early second and third trimesters, which helped in effectively predicting late-onset preeclampsia. Modak et al. [17] combined UPCR and a UA Doppler screening test to predict preeclampsia and produced results with high accuracy. Serra et al. [15] combined the maternal characteristics, biophysical parameters, and PlGF for the screening of eoPE. Similarly, Schmidt et al. [26] predicted preeclampsia with high accuracy using the ratio of sFlt1 to PlGF.

Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the studies in this review that had an accuracy above 90% suffer from several limitations. For example, Jhee et al. [19] developed an SGB model for late-onset preeclampsia prediction that achieved an accuracy of 0.973. A model for first-trimester data could not be obtained because most of the pregnant women were only involved in the antenatal evaluation program in the early second trimester. Despite this lack of data in the first trimester, the developed model predictive power was sufficient. Furthermore, the number of preeclampsia incidents was small, as only 474 out of 10,532 cases had preeclampsia, which is a common limitation from which published models suffer.

Tahir et al. [32] implemented NN to estimate the probability of preeclampsia with 96.66% accuracy after being validated using the LOO cross-validation method. The study used a sample of records from 239 women and considered 17 features. The dataset size is considered small; consequently, further research in a large cohort is essential to prove the reliability of the model result and minimize the features needed. In addition, there is no indication of whether the model is used for early or late prediction of preeclampsia. Another study by Tahir et al. [12] implemented a preeclampsia prediction DL model with an accuracy of 95.68% with a PSO feature selection algorithm to reduce the number of features from 17. The dataset was gathered from 1077 patient records at two hospitals in Makassar, as well as Surabaya Haji General Hospital, including records from the same 239 women as were included in the previous study. The PSO feature selection algorithm reduced the number of features from 17 to nine, which enhanced the dataset’s quality and improved the learning process; however, as in the previous study, early- and late-onset preeclampsia were not differentiated.

Furthermore, in Serra et al.’s study [15], despite the high accuracy of the mathematical model, it also suffers from the low number of eoPE events, which comprised only 17 of the 6893 pregnancies, causing an imbalanced database. Correspondingly, the prospective observational study by Modak et al. [17] produced an accuracy of 92.24%, but suffered from dataset-related problems. The study was conducted in a sample of 116 pregnant mothers, which is considered small; thus, to validate the reliability of the method, further study in a large cohort is required.

Carreno et al. [23] used a comparative strategy to assess the utility of time-series summary methods and feature size reduction methods in preeclampsia prognosis. The highest accuracy was achieved with an SVM algorithm paired with SPD for feature clustering, peaking at 93%. However, in this study, preeclampsia referred to both early and late preeclampsia, which makes it difficult to evaluate the proposed method’s performance in further investigations because patients could have early, late, or no preeclampsia.

Additionally, Li et al. [22] developed an XGBoost preeclampsia prediction model with an accuracy of 0.920. However, the performance of the XGBoost model could not be quantified among pregnancies with eoPE because of the rarity of eoPE. Therefore, additional research is needed to build more prediction models for the prediction of eoPE. Another limitation is that the model did not include the features related to pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or PlGF, which have previously been demonstrated to be related to the incidence of preeclampsia [37].

Moreover, research conducted by Sufriyana et al. [27] developed a CVR model for the prediction of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preeclampsia, including a sample of 95 women and considering 13 features. The CVR achieved an accuracy of 90.6%; however, the model has several limitations. The first limitation is that the model does not differentiate between IUGR and preeclampsia; consequently, the model should only be used for a referral decision. Second, the CVR model cannot be used to decide whether to deliver before term, as such a decision must be made based on models that precisely predict severe incidents of IUGR and preterm or early-onset preeclampsia. Third, the study used a small dataset of only 95 pregnancies.

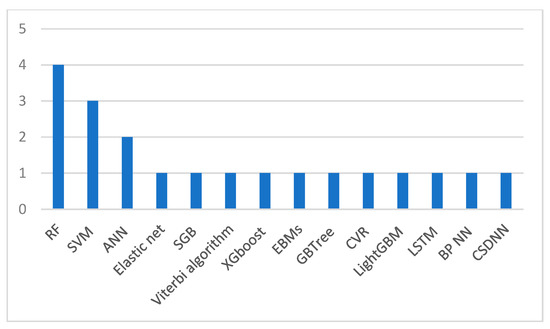

Sakinah et al. [33] built an LSTM model for preeclampsia prediction with an accuracy of 90.22%. However, more information about the study needs to be provided. The first missing information is the dataset size used in the model. The other information that needs to be mentioned is whether the prediction is for early- or late-onset preeclampsia. Figure 1 illustrates the ML and DL algorithms that were most widely implemented in the studies, Figure 2 shows the algorithms that obtained the best results in each study, and Table 4 shows a summary of the previous studies that used clinical data.

Figure 1.

Widely implemented ML and DL algorithms in previous studies.

Figure 2.

ML and DL algorithms that achieved the best results in each study.

Table 4.

Summary of the previous studies that used clinical data.

4. Challenges and Opportunities

4.1. Identifying the Disease

Predicting preeclampsia early and precisely is critical because it influences treatment response and prevents long-term complications in pregnancies. Preeclampsia has a complex disease presentation due to the lack of clear symptoms visible to the patient, and the signs are mostly silent. Choosing the right vital signs for early-stage diagnosis is a significant and challenging step in identifying the disease. Therefore, it is essential to consult doctors to select the right features, test the results, and ensure that the diagnosis is accurate, as inefficient health information systems can contribute to diagnostic errors. For instance, Tahir et al. [12] collected several references of papers which discussed preeclampsia as an initial step for choosing the features, but it resulted in having a diverse set of features. The researchers overcame this challenge by consulting obstetrics and gynecology specialists who assisted in choosing the right attributes and reasoning their choices.

4.2. Patients’ Data Security and Privacy

Patients’ data privacy may limit data sharing, hindering the development of precise ML models in medicine and limiting its progress. As a result, a solution to regulate data sharing in a way that does not impede progress, induce biases against underrepresented populations, or violate any patient privacy laws or regulations must be utilized [38]. A common solution is federated learning, which is a method of training AI models without allowing anyone else to access or touch the data, allowing you to unlock information to feed new AI applications [39]. Implementing robust security measures and protocols is of utmost importance to guarantee the confidentiality and dependability of healthcare systems that gather patient information. Given the sensitive nature of such data, it is imperative to safeguard it against any breaches that could lead to data exposure in further studies [40].

4.3. Reliability of the Models

In a clinical setting, the reliability of ML models includes performance metrics such as sensitivity, accuracy, specificity, precision, and AUC. Sensitivity is crucial to medical studies, since having high sensitivity is necessary to miss as few positive cases as possible [41]. Furthermore, ensuring ethical fairness and relevance for clinical translation is essential to ensure a reliable model and gain the trust and acceptance of health workers and patients. Thus, explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) practices can be used to interpret the black-box models and assist healthcare workers with translation [42].

4.4. Issues Related to the Datasets

Having the proper dataset size is essential to prevent overfitting and underfitting data [43]. Missing values in the dataset can also negatively impact the ML algorithms’ performance and the models’ accuracy [44]. Moreover, in [45], the study included a low prevalence of the disease in the population studied, resulting in an imbalanced dataset. This can cause bias in the results and make it harder for the algorithm to accurately classify the data. Several studies had a considerable drawback of having limited data sizes [46,47,48]. Furthermore, a number of these studies only had access to data from a single center [29,49], which could have resulted in a biased outcome. To improve the accuracy and trustworthiness of diagnostic models, it is advisable to utilize larger and multicenter datasets.

Furthermore, in [31], a small dataset was used in developing the models, which makes it difficult to interpret the results and questions the reliability of the models. To prevent such scenarios, the synthetic minority oversampling technique can be used to avoid an imbalanced dataset [45], and understanding the data’s distribution and handling the missing data based on the distribution minimizes this problem [44].

4.5. Model Interpretation

The ML models are black-box models, which means that the models are so complicated that humans cannot easily read them. The study in [22] highlighted the challenge of implementing ML models in clinical practice due to their complexity, arising from the potential inclusion of a large number of biomarkers, which can make the model more difficult to interpret and use in day-to-day medical decision making. In healthcare, where many decisions are truly life and death, a lack of interpretability in prediction models might weaken trust in those models [46]. XAI is considered a solution to improve the comprehension and interpretation of the predictions made by an ML model [47].

4.6. Human Barriers with AI Adoption in Healthcare

Despite the promising advances in utilizing AI in healthcare, human barriers arise while ensuring quality assurance and accuracy when adopting these technologies. The challenge of assigning liability in this situation is further complicated by the fact that AI technologies are constantly evolving and improving. As such, it is difficult to determine whether the algorithm or the physician should be held liable for any missed findings. Enhancing the human–computer interaction may reduce the cost of this problem, as algorithmic interpretability gives a better understanding in AI’s decisions [48].

4.7. Model Bias

This challenge refers to the risk of ML systems reflecting and amplifying societal biases, leading to unequal accuracy in minority subgroups. This can result in unfair outcomes in areas such as medicine where hospital mortality prediction algorithms may show varying accuracy. To address this issue, it is important to ensure that the data used for training the model are diverse and representative of the target population. Additionally, performance analysis should be conducted by considering subgroups such as age, ethnicity, and location to identify any potential biases in the model. As a result, XAI techniques [47] can be used to make the model’s decision-making process more transparent and explainable, allowing for further examination and adjustment to prevent any biases from being amplified.

5. Conclusions

This review attempted to offer a thorough analysis of the prior achievements made by researchers in the field of preeclampsia prediction. The use of ML algorithms and AI technologies in the medical industry has improved preeclampsia prediction applications. By identifying many ML, DL, and general techniques for preeclampsia prediction, we discovered that the most popular methods were RF, SVM, and LR. In the future, using real datasets, ML and DL algorithms can be utilized to forecast the disease. These datasets can include demographic, clinical, and laboratory information. Moreover, the ensemble method is the creation of a strong collaborative overall model by combining multiple models; this strategy can be utilized to enhance the overall prediction outcomes [49]. Lastly, the evaluation metrics used in the studies to evaluate the model results included AUC, ROC, confusion matrix, accuracy, specificity, recall (also known as sensitivity), F1 score, and precision, and the results were validated using K-fold cross-validation and LOO cross-validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.A.; methodology, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; software, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; validation, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; formal analysis, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; investigation, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; resources, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; data curation, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A., H.S., N.A., I.U.K., D.A.A. and A.A.; visualization, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A., H.S., N.A., I.U.K., D.A.A. and A.A.; supervision, S.S.A.; project administration, S.S.A., N.A., I.U.K., D.A.A. and A.A; funding acquisition, S.S.A., M.A. (Manar Alzahrani), R.A., M.A. (Majd Altukhais), S.A., H.S., N.A., I.U.K., D.A.A. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fabjan-Vodusek, V.; Kumer, K.; Osredkar, J.; Verdenik, I.; Gersak, K.; Premru-Srsen, T. Correlation between Uterine Artery Doppler and the SFlt-1/PlGF Ratio in Different Phenotypes of Placental Dysfunction. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2019, 38, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrowaili, M.M.; Zakari, N.M.A.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Moawed, S. Management of Gestational Hypertension Disorders in Saudi Arabia by Primary Care Nurses. Saudi Crit. Care J. 2020, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Gammill, H.S. Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2005, 46, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelícia, S.M.D.C.; Fekete, S.M.W.; Corrente, J.E.; Rugolo, L.M.S.D.S. Impact of Early-Onset Preeclampsia on Feeding Tolerance and Growth of Very Low Birth Weight Infants during Hospitalization. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2023, 41, e2021203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, S.; Naicker, T. The Contribution of Complement Protein C1q in COVID-19 and HIV Infection Comorbid with Preeclampsia: A Review. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 183, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokotyanskaya, E.A.; Panova, I.A.; Malyshkina, A.I.; Fetisova, I.N.; Fetisov, N.S.; Kharlamova, N.V.; Kuligina, M.V. Technologies for Prediction of Preeclampsia. Sovrem. Tehnol. V Med. 2020, 12, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, T.A.; Zheng, L.; Afifi, A.J.; Ali, A.; Yin, M.; Gao, J. Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Medical Imaging to Combat Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Detailed Review with Direction for Future Research. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamet, P.; Tremblay, J. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Metabolism 2017, 69, S36–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Aggarwal, D. LEARNING-Based Focused WEB Crawler. IETE J. Res. 2021, 67, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, S.; Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, H. Application of Deep Learning in Automated Analysis of Molecular Images in Cancer: A Survey. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2017, 2017, 9512370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakator, M.; Radosav, D. Deep Learning and Medical Diagnosis: A Review of Literature. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Badriyah, T.; Syarif, I. Classification Algorithms of Maternal Risk Detection For Preeclampsia With Hypertension During Pregnancy Using Particle Swarm Optimization. EMITTER Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 6, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodepogu, K.R.; Annam, J.R.; Vipparla, A.; Krishna, B.V.N.V.S.; Kumar, N.; Viswanathan, R.; Gaddala, L.K.; Chandanapalli, S.K. A Novel Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Diagnosis of Skin Disease. Traitement Du Signal 2022, 39, 1873–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soongsatitanon, A.; Phupong, V. Prediction of Preeclampsia Using First Trimester Placental Protein 13 and Uterine Artery Doppler. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 4412–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, B.; Mendoza, M.; Scazzocchio, E.; Meler, E.; Nolla, M.; Sabrià, E.; Rodríguez, I.; Carreras, E. A New Model for Screening for Early-Onset Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, e1–e608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byonanuwe, S.; Fajardo, Y.; Nápoles, D.; Alvarez, A.; Cèspedes, Y.; Ssebuufu, R. Predicting Risk of Chronic Hypertension in Women with Preeclampsia Based on Placenta Histology. A Prospective Cohort Study in Cuba. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-44764/v1 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Modak, R.; Pal, A.; Pal, A.; Ghosh, M.K. Prediction of Preeclampsia by a Combination of Maternal Spot Urinary Protein-Creatinine Ratio and Uterine Artery Doppler. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, I.; Tsur, A.; Aghaeepour, N.; Montanari, A.; Stevenson, D.K.; Shaw, G.M.; Winn, V.D. Early Prediction of Preeclampsia via Machine Learning. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, Y.A.; Kang, S.-W.; Kwon, J.-Y.; Park, J.T. Prediction Model Development of Late-Onset Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning-Based Methods. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, I.; Pavaloiu, B.-I.; Marian, C.-V.; Racovita, V.; Goga, N. Early Detection of Preeclampsia Based on a Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 21–23 November 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; Ding, Y.; Shi, M.; Sun, L.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Yan, R.; et al. Development of a Prediction Model on Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning-Based Method: A Retrospective Cohort Study in China. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 896969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, X.; Yang, C.; Cao, Z.; Du, R.; Yu, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, M. Novel Electronic Health Records Applied for Prediction of Pre-Eclampsia: Machine-Learning Algorithms. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2021, 26, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, J.F.; Qiu, P. Feature Selection Algorithms for Predicting Preeclampsia: A Comparative Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–19 December 2020; pp. 2626–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Velasco, A.; Martínez-Villaseñor, L.; Miralles-Pechuán, L. Machine Learning Approach for Pre-Eclampsia Risk Factors Association. In Proceedings of the 4th EAI International Conference on Smart Objects and Technologies for Social Good—Goodtechs ’18, Bologna, Italy, 28–30 November 2018; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bosschieter, T.M.; Xu, Z.; Lan, H.; Lengerich, B.J.; Nori, H.; Sitcov, K.; Souter, V.; Caruana, R. Using Interpretable Machine Learning to Predict Maternal and Fetal Outcomes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.05322. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L.J.; Rieger, O.; Neznansky, M.; Hackelöer, M.; Dröge, L.A.; Henrich, W.; Higgins, D.; Verlohren, S. A Machine-Learning–Based Algorithm Improves Prediction of Preeclampsia-Associated Adverse Outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, e1–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufriyana, H.; Wu, Y.-W.; Su, E.C.-Y. Prediction of Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Development of Machine Learning Models on a Prospective Cohort. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e15411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufriyana, H.; Wu, Y.-W.; Su, E.C.-Y. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Prediction of Preeclampsia: Development and External Validation of a Nationwide Health Insurance Dataset of the BPJS Kesehatan in Indonesia. EBioMedicine 2020, 54, 102710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Salerno, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, X.; Li, H. Prediction of Severe Preeclampsia in Machine Learning. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2022, 15, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Mallia, D.; Clark-sevilla, A.O.; Catto, A.; Leshchenko, A.; Haas, D.M.; Raja, A.; Salleb-aouissi, A. Preeclampsia Predictor with Machine Learning: A Comprehensive and Bias-Free Machine Learning Pipeline. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalaín, C.; Herraiz, I.; Domínguez-Del Olmo, P.; Angulo, P.; Ayala, J.L.; Galindo, A. Prediction of Delivery Within 7 Days After Diagnosis of Early Onset Preeclampsia Using Machine-Learning Models. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 910701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Badriyah, T.; Syarif, I. Neural Networks Algorithm to Inquire Previous Preeclampsia Factors in Women with Chronic Hypertension During Pregnancy in Childbirth Process. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Electronics Symposium on Knowledge Creation and Intelligent Computing (IES-KCIC), Bali, Indonesia, 29–30 October 2018; pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sakinah, N.; Tahir, M.; Badriyah, T.; Syarif, I. LSTM With Adam Optimization-Powered High Accuracy Preeclampsia Classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Electronics Symposium (IES), Surabaya, Indonesia, 27–28 September 2019; pp. 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Manoochehri, Z.; Manoochehri, S.; Soltani, F.; Tapak, L.; Sadeghifar, M. Predicting Preeclampsia and Related Risk Factors Using Data Mining Approaches: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, W.; Guo, X.D.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.F.; Yu, L.; Yan, J.Y. A New Predicting Model of Preeclampsia Based on Peripheral Blood Test Value. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7222–7229. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.; Mulla, Z.D.; Parikh, P.; Hauspurg, A.; Razzaghi, T. An Imbalance-Aware Deep Neural Network for Early Prediction of Preeclampsia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L.; Hobbins, J.C.; Malone, F.D.; Porter, T.F.; Luthy, D.; Comstock, C.H.; Hankins, G.; Berkowitz, R.L.; Merkatz, I.; Craigo, S.D.; et al. First-Trimester Maternal Serum PAPP-A and Free-Beta Subunit Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Concentrations and Nuchal Translucency Are Associated with Obstetric Complications: A Population-Based Screening Study (The FASTER Trial). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seastedt, K.P.; Schwab, P.; O’Brien, Z.; Wakida, E.; Herrera, K.; Marcelo, P.G.F.; Agha-Mir-Salim, L.; Frigola, X.B.; Ndulue, E.B.; Marcelo, A.; et al. Global Healthcare Fairness: We Should Be Sharing More, Not Less, Data. PLOS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Kang, Y.; Chen, T.; Yu, H. Federated Learning; Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 13, pp. 1–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Y. Opportunities and Challenges of Artificial Intelligence in the Medical Field: Current Application, Emerging Problems, and Problem-Solving Strategies. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 030006052110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.A.; Strümke, I.; Thambawita, V.; Hammou, M.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; Parasa, S. On Evaluation Metrics for Medical Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagurunathan, Y.; Mitchell, R.; El Naqa, I. Requirements and Reliability of AI in the Medical Context. Phys. Med. 2021, 83, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y. Overfitting and Underfitting Analysis for Deep Learning Based End-to-End Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP), Xi’an, China, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Biancolillo, A.; Roger, J.M.; Marini, F.; Rutledge, D.N. New Data Preprocessing Trends Based on Ensemble of Multiple Preprocessing Techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 132, 116045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Keung, J.; Yu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, M. Investigation on the Stability of SMOTE-Based Oversampling Techniques in Software Defect Prediction. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 139, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petch, J.; Di, S.; Nelson, W. Opening the Black Box: The Promise and Limitations of Explainable Machine Learning in Cardiology. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speith, T. A Review of Taxonomies of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–24 June 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2239–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, K.; McParland, A.; Mehta, S.; Ackery, A.D. Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Medicine: Surmountable Barriers with Revolutionary Potential. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 75, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, R.; Al-Mousa, A. Heart Disease Detection Using Machine Learning Majority Voting Ensemble Method. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on new Trends in Computing Sciences (ICTCS), Amman, Jordan, 9–11 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).