Abstract

Cybersecurity has become one of the top priorities in Saudi Arabia, playing a key role in achieving Vision 2030 and advancing the kingdom’s position in digital transformation. This study investigates how cybersecurity knowledge, attitudes, and awareness influence user behaviours in health applications within Saudi Arabia. An online cross-sectional survey was distributed between March and April 2025 among Saudi Arabian residents. The collected data (n = 629) were analyzed using Smart PLS Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to assess the relationships among the study constructs. The majority of the participants (61.4%) were between the age of 18 and 24, and 87.6% reported using health applications such as Sehhaty or Labayh to manage their health information. Results demonstrated that all three constructs significantly predicted cybersecurity behaviours: knowledge showed the strongest influence (β = 0.372), followed by attitude (β = 0.343) and awareness (β = 0.199), with all paths being statistically significant (p < 0.05). The model explained substantial variance in cybersecurity behaviours. Knowledge, attitude, and awareness significantly predict cybersecurity practices in healthcare application contexts. Findings highlight the critical need for targeted educational interventions focusing on cybersecurity knowledge enhancement and awareness programmes to promote safer digital health behaviours and strengthen patient data protection in Saudi Arabia’s healthcare system.

1. Introduction

The healthcare sector accounts for a significant portion of global data breaches, with over 24% of breaches originating in healthcare and 80–85% of worldwide breaches affecting this sector [1]. These breaches carry severe consequences including financial losses, legal implications, and loss of patient trust in healthcare systems [2]. Human error represents a major contributing factor, with studies indicating that 11% of incidents stem primarily from users’ mistakes and over 70% of breaches are linked to human-related events. Analysis of breach incidents reveals that technology vulnerabilities, when combined with inadequate security policies and human error, create critical exposure points for healthcare organizations [3]. Furthermore, legacy systems, network-connected devices, and rapid digitalization, coupled with underinvestment in cybersecurity (21%) [4], substantially increase the vulnerability of healthcare organizations to cyber-attacks [5,6,7]. The proliferation of network-connected medical devices introduces additional attack surfaces, as these devices often lack adequate security controls and require specialized approaches to risk management [8]. In the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, this threat has become particularly acute as the healthcare sector undergoes rapid digital transformation aligned with Vision 2030. These attacks pose multifaceted threats: the loss of valuable information, erosion of stakeholder confidence, and critically, the compromise of healthcare service delivery effectiveness and sector reliability [9,10]. The economic impact of healthcare data breaches extends beyond immediate remediation costs to include regulatory fines, litigation expenses, and long-term reputational damage affecting organizational sustainability [11]. The vulnerability of healthcare systems stems not merely from technological gaps but predominantly from the human element—users’ insufficient cybersecurity knowledge, attitudes, and awareness [12]. Addressing these multifaceted threats requires a holistic information security management approach that integrates technical, organizational, and human factors [13]. Consequently, designing comprehensive training programmes that raise awareness of these threats and risks has become a strategic imperative for the kingdom’s healthcare sector; the ethical implications of health data management and the duty to protect patient information have become central concerns in the digital health era [14].

Recognizing these challenges, cybersecurity has emerged as a top priority in Saudi Arabia, directly supporting the kingdom’s Vision 2030 objectives and its advancement among technologically developed nations. The establishment of robust regulatory frameworks, beginning with the Communications Law in 2001, has strengthened security infrastructure considerably. These initiatives encompass monitoring network activity, regulating the telecommunications industry, and providing organizations with comprehensive measures to combat cybercrimes [15]. However, despite these significant policy advancements and infrastructure improvements in healthcare cybersecurity, a critical gap persists in understanding how individual users—particularly patients and mobile health (mHealth) application users—influence security through their behaviours. Research indicates that usability challenges, privacy concerns, and limited user awareness substantially affect both adoption and safe usage patterns [16], underscoring the necessity of addressing user behaviour alongside technical and policy interventions. This disconnect between awareness and practice is particularly evident in the Saudi context, where despite high awareness of mobile mental health applications (68.9%), actual usage remains notably low (20%), revealing a substantial gap between knowledge and behavioural implementation. As the use of health applications continues to grow, understanding users’ cybersecurity awareness has become increasingly important, as studies on Saudi university students show variations in knowledge and behaviour across different factors, highlighting the need for awareness programmes [17]. Adoption patterns are primarily influenced by perceived usefulness, emphasizing the critical need to comprehend user attitudes and foster engagement to ensure effective digital health interventions aligned with Saudi Vision 2030 and necessitating ethical frameworks for digital health technologies [18,19].

This study investigates how cybersecurity knowledge, attitudes, and awareness influence cybersecurity behaviours, which are in turn reflected in the protection of patient data in the kingdom. Knowledge refers to the users’ understanding of key cybersecurity concepts, such as network security, threat detection, and data protection [20,21]. Attitude encompasses users’ motivation and willingness to engage in secure behaviours when using health applications, reflecting their evaluative beliefs about the importance of cybersecurity practices and their readiness to prioritize data protection [22,23]. Awareness involves users’ recognition of the importance of protecting their health-related data, and their attentiveness to security-related features, such as noticing privacy policies or the presence of security certifications in health applications [24,25]. Behaviour examines the actual cybersecurity-related actions users take, distinguishing it from awareness or knowledge. While awareness represents recognition of security importance and knowledge encompasses understanding of security concepts, behaviour reflects the observable actions users perform including adherence to security protocols, identification of threats, proactive cybersecurity practices, and consistent implementation of proactive measures when using health applications. This distinction is critical: users may be aware of risks and possess relevant knowledge yet fail to translate this into protective behaviours, creating the attitude–behaviour gap that this study seeks to understand. By exploring these factors, the study aims to contribute to improving cybersecurity practices within this vital sector. It is therefore hypothesized that cybersecurity knowledge, awareness, and attitudes play a significant role in shaping the cybersecurity behaviours of health application users.

Insufficient cybersecurity knowledge can have serious repercussions in the healthcare sector because of the possibility of operational technology (OT) system breaches. This highlights the necessity of training programmes that provide personnel with the skills and knowledge to identify, stop, and effectively respond to cyber-attacks by addressing the unique security concerns in this industry [21]. Evaluating training effectiveness through a systematic case study approach ensures that awareness programmes achieve their intended behavioural outcomes [25]. As Shen et al. [26] demonstrated, cybersecurity fatigue—driven by frequent security alerts and complex protocols—significantly predicts burnout, reduced productivity, and mental health decline among employees. The study highlights the moderating role of mental health support and job context in mitigating negative outcomes. In contrast, Donalds & Osei-Bryson [23] examined how personal decision-making styles, security awareness, and contextual factors influence users’ cybersecurity compliance, and the authors highlighted the importance of aligning interventions with individual cognitive profiles.

Another related study investigated the impact of cybersecurity policy awareness on employees’ cybersecurity behaviours. While the original context focused on organizational settings, the findings offer insights applicable to user behaviours in digital health applications. For example, Li et al. [21] demonstrated that policy awareness, threat appraisal, and working conditions (like time pressure and autonomy) are significant antecedents of secure and insecure behaviours among employees. According to the Annual Cybersecurity Attitudes and Behaviours Report (2024), which was published through the cooperation of CybSafe and the National Cybersecurity Alliance, a global survey of over 7000 employees revealed key behavioural trends related to digital safety. Although the report is centred on organizational cybersecurity, the insights shed light on broader patterns relevant to user behaviour in health applications, such as the impact of AI use, attitudes toward security training, and the psychological barriers to secure behaviour. The annual report identified factors like intimidation by security protocols, overconfidence, and the prevalence of risky data-sharing with AI tools as major determinants of cybersecurity behaviour.

Parsons et al. [25] determined employee awareness using the Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q), where the authors introduced and validated the HAIS-Q as a tool for measuring employee security awareness, linking awareness levels to behavioural outcomes and identifying knowledge gaps that can be addressed through training. Complementing traditional awareness assessments, integrated strategies that evaluate both attitudes and behaviours in educational contexts provide comprehensive insights into cybersecurity preparedness across different populations [27]. Aschwanden et al. [28] identified psychological biases and employee personas that increase cyber risk, advocating for tailored behavioural interventions in organizational settings. Wang [20] pointed out that the end users of IT do not always have the proper understanding of the cybersecurity measures including anti-tracking, anti-phishing, and data encryption, thus making them easy prey for the cyber-attacks. It is crucial for people to gain knowledge and skills in cyber and human resources since knowledge, skills, and experience are crucial in decision-making and security implementation.

The role of organizational culture and management support in shaping security behaviour has been well-documented. Nasir et al. [29] analyzed the dimensions of information security culture, emphasizing the need for holistic approaches that integrate technical and human factors. Humaidi and Balakrishnan [30] demonstrated the indirect effect of management support on users’ compliance behaviour towards information security policies in healthcare settings, highlighting the importance of leadership commitment in fostering security-conscious organizational environments. Based on the insights provided by Maalem Lahcen et al. [22], as there is sensitive data that needs to be protected, it is crucial to assess cybersecurity knowledge, attitudes, awareness, and behaviours in the healthcare industries. Comprehensive reviews of information security behaviour in health information systems identify multiple antecedent factors spanning individual, organizational, and technological dimensions that collectively shape security practices [31]. Knowledge is important as it helps the patients to recognize the possible dangers and the steps that need to be taken in order to avoid them. The following are characteristics of a positive attitude towards cybersecurity among health application users, meaning that users are likely to practice safe practices and be alert. A health application security posture is directly affected by actions including following the right procedures, avoiding risky behaviours, and effectively handling risks. Awareness training programmes tailored specifically for healthcare contexts must address sector-specific threats and regulatory requirements while ensuring knowledge transfer to actual workplace behaviours [32]. Lastly, training and awareness act as a bridge by giving users the essential skills and reaffirming safe procedures to counteract changing threats. Developing robust metrics to assess cybersecurity awareness programme effectiveness enables organizations to measure behavioural changes and refine training interventions based on evidence [33].

Together, these elements highlight how critical it is to close knowledge gaps, raise awareness, encourage positive attitudes, and promote safe cybersecurity behaviour tailored to the unique requirements of the healthcare sector. This is consistent with the proposed research model, which investigates how these elements interact to improve cybersecurity behaviour in healthcare [20,25,28]. Albediwi & Sadaf [34] demonstrated that many Saudi citizens engage in risky cybersecurity practices including using weak passwords, with over half of the participants (56%) forgetting to update them often. Although 66% recognize the need for data backups, just 25% really use them, highlighting the gap between awareness and behaviour. A lack of knowledge about social engineering also makes many vulnerable to manipulation. These findings underscore the importance of customized instruction in sectors including digital healthcare, where enhancing cybersecurity awareness and practices is crucial to protecting sensitive data [34,35]. This study extends cybersecurity behaviour theory in three ways. First, it adapts the Knowledge–Attitude–Awareness–Behaviour framework to voluntary health contexts. Previous studies examined organizational employees with mandatory security policies. This research studies personal health app users who make independent security decisions. This shift is theoretically significant. Second, the study addresses a gap in mobile health cybersecurity research. Existing frameworks were developed for desktop computers and organizational IT systems. We adapt these models to mobile health applications where users control sensitive medical data through personal devices. Third, this research provides empirical evidence within Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 digital transformation. Testing established constructs in this context contributes to understanding how cybersecurity behaviours operate across different cultural and institutional settings. These contributions demonstrate that organizational cybersecurity models require modification for personal health technology contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Framework and Design

The study employs a quantitative approach to collect data using a cross-sectional survey design to examine the relationships between knowledge, attitude, and awareness in the context of cybersecurity behaviours and how these determinants ultimately shape cybersecurity behaviour among health application users. The study aims to test the proposed hypotheses derived from the conceptual framework of Fattah et al. [36], which originally asserts that cybersecurity training positively impacts users’ knowledge, attitudes, and awareness, thereby enhancing overall cybersecurity behaviour.

2.2. Participants and Setting

A total of 629 responses were collected from participants across various regions of Saudi Arabia. Participants were recruited through an online survey distributed via social media platforms. Inclusion criteria required participants to be 18 years or older and to provide consent to participate in the study. Respondents who reported not using health applications (n = 78, 12.4%) were excluded from the SEM analysis.

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

The questionnaire was adopted from the 20-item Enhanced Security Behaviour Scale (ESBS), which was created by Sawaya et al. [37], who confirmed its reliability and validity across different samples. In this study, 17 items (85%) from the original scale were chosen for the current study to align with the study objectives.

This selective adaptation was guided by several methodological and theoretical considerations. Items were systematically selected based on their direct correspondence to the four primary constructs under investigation: knowledge, attitude, awareness, and behaviour. This ensured each item contributed meaningfully to measuring these dimensions within the healthcare application context, thereby enhancing construct validity. Additionally, items were selected based on their applicability to mobile health applications such as Sehhaty and Labayh. Items addressing general computing contexts (e.g., desktop computers and securing emails) were excluded as less relevant to the mobile-centric nature of contemporary healthcare applications, improving the scale’s relevance for the target population. The adapted scale maintained an acceptable reliability (average Cronbach’s α = 0.66 across constructs; 97.5% CI in SEM path estimations) which fell below the commonly cited threshold of 0.70. However, this level is considered acceptable in the present context, as cybersecurity behaviour is inherently heterogeneous, covering multiple domains that naturally reduce inter-item correlations [38]. Moreover, given that the study employs PLS-SEM, greater emphasis is placed on composite reliability over Cronbach’s alpha alone, reducing concerns associated with a lower alpha value [39]. Importantly, all structural path coefficients were statistically significant, and prior studies in the cybersecurity context report comparable reliability levels. Construct-level reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho_A, as detailed in the Section 3, while maintaining an appropriate sample size-to-item ratio (n = 629) for reliable SEM analysis and preserving the original instrument’s validated structure. The selected items were rearranged and grouped into the four main constructs. Five demographic questions were also included to gather background data from the participants. An over-claiming question was included to distinguish participants who may respond in socially desirable ways, following the approach outlined by McCormac et al. [40]. While maintaining the conceptual integrity of the original scale, minor changes were made to the item phrasing to better suit the research context.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted between March and April 2025 among residents of Saudi Arabia. The questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and distributed through various social media platforms, with participants encouraged to share the link with their peers. The survey was self-administered, allowing participants to complete it independently.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using Smart PLS Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) Version 3 (SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany). The analysis assessed path coefficients and had 97.5% confidence intervals for proposed relationships. Construct reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho_A. Regarding common method bias, additional statistical tests such as Harman’s single-factor test were not conducted, as these tests are more appropriate for covariance-based approaches using software such as SPSS. Hypothesis testing was conducted using both t-values and p-values to determine the statistical significance of the structural relationships.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Analysis

A total of 629 responses were collected from participants across various regions of Saudi Arabia. Most of the participants (61.4%) were between the age of 18 and 24, indicating a predominantly young sample. Other age groups included 13.5% aged 35–44, 12.4% aged 25–34, 10.5% aged 45–54, and only 2.2% aged 55 and above. Regarding educational background, most participants held a bachelor’s degree (62.3%), followed by high school education (31%), and a smaller percentage held a master’s degree (5.1%). Only around 1% held a doctoral degree. Although educational level was not a primary focus of this study, the predominance of bachelor’s degree holders suggests a generally well-educated sample. Geographically, participants were primarily from the western region of the kingdom (70.4%), followed by the central region (13%), the eastern region (10%), the southern region (3.2%), and the remaining from the northern region. Finally, when asked whether they use health applications such as Sehhaty or Labayh to manage their health information, 87.6% of participants reported that they do, while 12.4% indicated that they do not use such applications. This high usage rate suggests strong engagement with digital health platforms among the surveyed population.

3.2. Theoretical Framework and Model Specification

Figure 1 shows the research model which illustrates the hypothesized impact of three key constructs—knowledge, attitude, and awareness—on the behavioural cybersecurity practices of users of healthcare applications. These latent variables are significant cognitive and psychological elements that may significantly influence how people behave regarding cybersecurity in the context of medical technology.

Figure 1.

The proposed theoretical framework of this study.

3.3. Model Reliability and Validity

The estimated confidence intervals for the proposed relationships in the structural model are shown in Table 1. The reliability of the model’s path estimations is strongly supported by the high degree of statistical precision reflected in the 97.5% confidence level, which leaves only 2.5% uncertainty. Cronbach’s alpha was used to show the internal consistency reliability of the measured constructs. Construct-level reliability was assessed using multiple metrics. Table 2 presents Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho_A for each construct. Composite reliability values ranged from 0.72 to 0.78, all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating adequate internal consistency. Rho_A values ranged from 0.68 to 0.75, further confirming construct reliability. While Cronbach’s alpha values for some constructs fell below 0.70 (ranging from 0.63 to 0.70), this is acceptable given that cybersecurity behaviour is inherently heterogeneous and PLS-SEM emphasizes composite reliability over Cronbach’s alpha. Some items showed low factor loading (e.g., Q15 = −0.227 and Q11 = 0.064). These indicators were retained because they represent conceptually important aspects of cybersecurity behaviour that may not be strongly correlated with the other indicators due to the multifaceted nature of the construct. Retaining these indicators support content validity by ensuring broader theoretical coverage of cybersecurity behaviours. Despite the presence of low loadings, the structural model demonstrated robust and statistically significant relationships among all hypothesized constructs, indicating that the measurement approach adequately captured the theoretical framework of the study.

Table 1.

Confidence intervals and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Construct reliability and internal consistency assessment.

3.4. Measurement Model Analysis

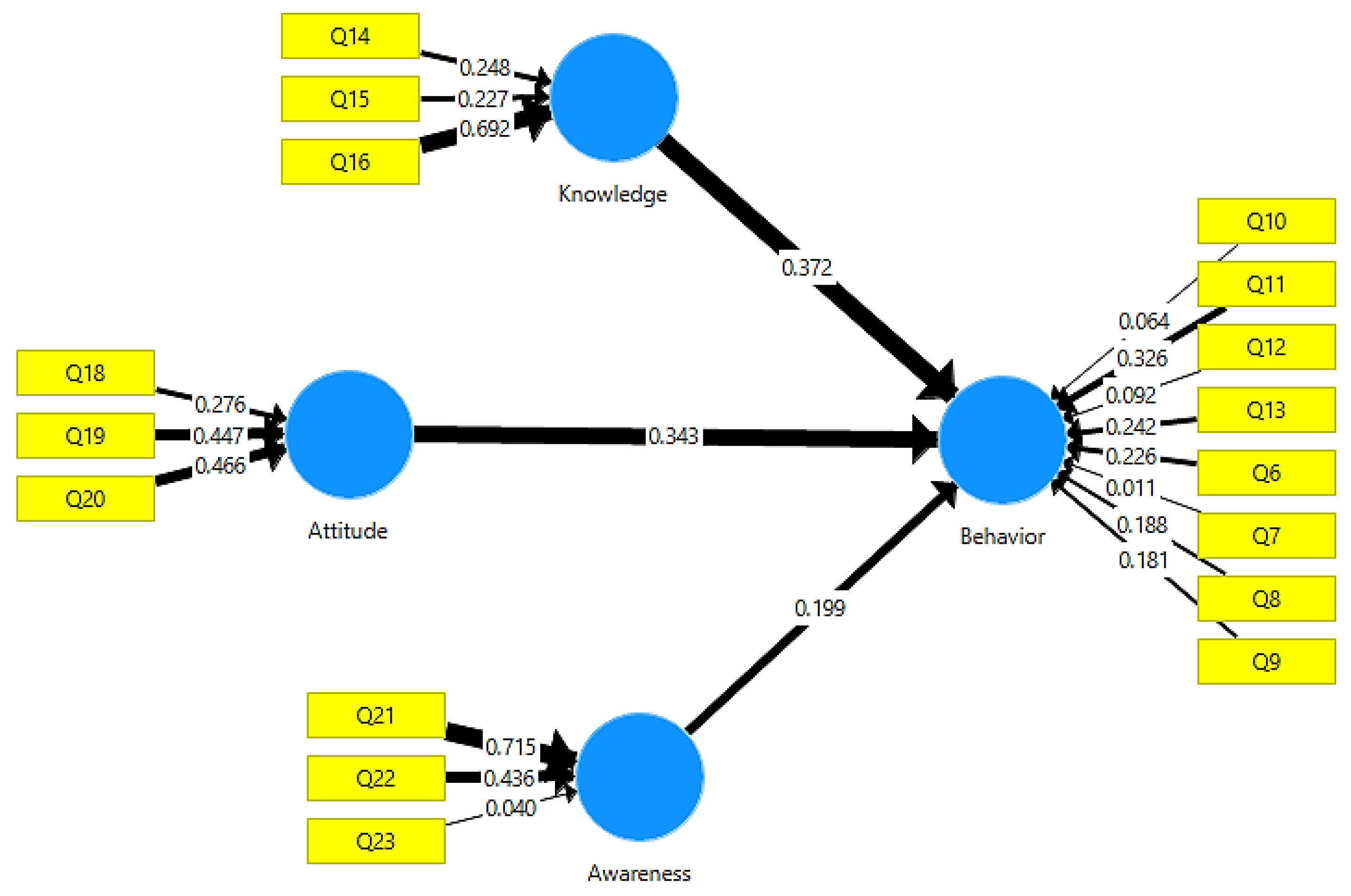

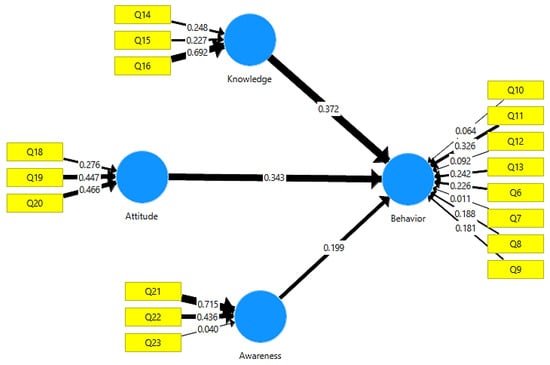

Figure 2 shows the reflective measurement of each independent variable using three identified indicators. To capture users’ knowledge of cybersecurity in healthcare settings, three items (Q14, Q15, and Q16) were chosen for the knowledge construct and converted into reflecting indicators. The attitude construct is also expressed using three reflecting indicators (Q18, Q19, and Q20) that represent users’ motivational orientation and evaluative beliefs regarding cybersecurity practices. The awareness construct is measured using three reflective indicators (Q21, Q22, and Q23). These indicators assess participants’ recognition and attentiveness to cybersecurity features and the importance of data protection when utilizing health apps.

Figure 2.

Reflective measurement model with indicators for knowledge, attitude, and awareness constructs in healthcare cybersecurity.

3.5. Structural Model Results and Path Analysis

Table 3 illustrates the total effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable, in addition to the strength of association between individual indicators and their respective latent constructs. These coefficients provide insightful information about the relative significance of factors influencing healthcare application users’ behavioural cybersecurity.

Table 3.

Influence of factors and indicator strengths on cybersecurity behaviour.

Knowledge → Behaviour: With a path coefficient of 0.372, which denotes a moderate-to-strong effect, the knowledge construct had the greatest impact on cybersecurity behaviour. Q16, which measures how much users review permanent health privacy policies in order to understand how their data is handled, had the highest loading (0.692) among its indications. This item’s descriptive statistics showed a skewness of −0.805, excess kurtosis of −0.480, a mean of 3.914, and a standard deviation of 1.194.

Attitude → Behaviour: With a path coefficient of 0.343, attitude, the second independent variable, significantly influenced behaviour. In this construct, Q20 produced the highest factor loading (0.466), reflecting users’ willingness to engage with healthcare professionals about privacy and cybersecurity concerns related to digital health services, with a mean of 3.639, standard deviation of 1.217, excess kurtosis of −0.884, and skewness of −0.472.

Awareness → Behaviour: With a path coefficient of 0.199, awareness, the third construct, had a smaller but still significant impact on behaviour. In addition, Q21 showed the highest indicator loading (0.715), capturing users’ attentiveness to security certifications in health applications. Although this item’s wording involves action-oriented language (noticing and recognizing security features), it primarily measures cognitive awareness rather than the execution of protective behaviours. The item assesses whether users pay attention to security certifications, not whether they actively verify or implement them. With a mean of 4.215, standard deviation of 0.954, excess kurtosis of 0.931, and skewness of −1.179, this item showed a distribution that is more peaked and heavily left-skewed than the normal distribution. Behavioural Indicator Strength: With a factor loading of 0.326, Q11 emerged as the most significant indicator among the items assessing the dependent variable (behavioural cybersecurity). The tendency of users to check attachments for viruses before downloading or opening them is reflected in this item. The mean response was 3.908, with a standard deviation of 1.191, excess kurtosis of −0.579, and skewness of −0.766.

3.6. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing was conducted using both t-values and p-values to evaluate the structural relationships between the independent variables (knowledge, attitude, and awareness) and the dependent variable (behavioural cybersecurity). The results presented in Table 4 serve as the basis for determining the statistical significance of each proposed path.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of hypothesis testing.

H1:

There is no significant relationship between knowledge and behavioural cybersecurity. A statistically significant relationship was indicated by the p-value for this hypothesis being less than the standard significance level of 0.05. As a result, the alternative hypothesis is accepted and the null hypothesis is rejected, demonstrating that knowledge positively impacts users’ behavioural cybersecurity practices in healthcare applications.

H2:

There is no significant relationship between attitude and behavioural cybersecurity. The alternative hypothesis is supported and the null hypothesis is thereby rejected since the p-value for this path was likewise less than the level of 0.05. According to the findings here, users’ attitudes significantly and positively influence how they behave in cybersecurity-related contexts.

H3:

There is no significant relationship between awareness and behavioural cybersecurity. The null hypothesis was rejected, and the alternative was accepted after the analysis showed a p-value for this relationship that was less than 0.05. This demonstrates that the behavioural cybersecurity of users of healthcare applications’ is influenced by awareness. All of these findings show that awareness, attitude, and knowledge are critical factors that influence cybersecurity behaviours. This supports the conceptual model directly and justifies more research into these concepts in the context of healthcare digital security.

4. Discussion

This study examined how knowledge, attitude, and awareness shape cybersecurity behaviours among Saudi Arabian health application users. The results provide robust support for all three hypotheses. H1, positing that knowledge positively influences cybersecurity behaviour, was strongly supported (β = 0.372, p < 0.001). H2, predicting attitude’s positive effect on behaviour, was confirmed (β = 0.343, p < 0.001). H3, proposing awareness positively affects behaviour, was also supported (β = 0.199, p < 0.05). Collectively, the model explained 48.7% of variance in cybersecurity behaviours, with knowledge demonstrating the strongest influence, followed by attitude and awareness.

4.1. Knowledge as the Primary Behavioural Driver

Knowledge emerged as the strongest predictor (β = 0.372), supporting H1 and extending findings by Wang [20]. This dominance suggests that understanding privacy policies (Q16: highest loading λ = 0.692) directly enables users to implement protective measures. In personal health apps lacking organizational enforcement, users must independently recognize threats and implement protection capabilities directly dependent on cybersecurity literacy. Vision 2030’s digital literacy initiatives have systematically raised cybersecurity knowledge among young Saudis through educational programmes and public awareness campaigns. This institutional knowledge-building creates a foundation for users to interpret complex privacy policies and make informed security decisions. Saudi cultural values emphasizing privacy and confidentiality further amplify knowledge’s impact. When users understand security mechanisms, these cultural norms provide additional motivation to protect sensitive health data. However, knowledge alone is insufficient without digital self-efficacy to translate understanding into action. The predominantly young sample (61.4% aged 18–24) demonstrates characteristically higher digital self-efficacy, enabling them to translate knowledge into protective behaviours more readily than older adults. This age factor likely amplifies knowledge’s observed behavioural impact and suggests older users may require different intervention approaches emphasizing hands-on training beyond information provision. While the results suggest that age may influence the translation of cybersecurity knowledge into behaviour, this study did not conduct formal moderation or multi-group analysis; therefore, these observations are presented as speculative and should be interpreted with caution.

4.2. Attitude’s Motivational Contribution

Attitude demonstrated nearly equivalent influence to knowledge (β = 0.343), confirming H2, which states that favourable security attitudes independently motivate protective behaviours. The highest-loading attitude indicator (Q20: λ = 0.466, M = 3.639) reflects users’ willingness to discuss privacy and cybersecurity concerns with healthcare professionals. This motivational orientation suggests users who value security actively seek information and engage in dialogue about data protection. This finding aligns with Donalds & Osei-Bryson [23], who emphasized personal decision-making styles and motivational factors.

In voluntary health app contexts, where no organizational policies mandate compliance, personal attitudes toward data protection become critical determinants of whether users invest effort in security measures. Health data breaches affect users personally and directly, unlike organizational breaches that primarily impact employers. This personal stake in health privacy elevates the importance of security attitudes as drivers of sustained protective effort. Vision 2030’s cybersecurity campaigns have actively promoted data protection as a national priority, framing security as both a personal responsibility and civic duty. These government initiatives shape user attitudes by legitimizing security concerns and normalizing verification behaviours such as checking app certifications.

4.3. Awareness’s Limited Direct Effect

Awareness showed the smallest yet significant effect (β = 0.199), supporting H3 despite its modest magnitude. This modest contribution diverges from Parsons et al.’s [24] organizational findings where awareness was the dominant predictor. Several explanations warrant consideration: First, personal health app contexts differ fundamentally from organizational environments. Organizations actively promote security awareness through mandatory training and constant reminders, keeping threats salient. Personal app users receive sporadic, passive exposure to security information, potentially diminishing awareness’s behavioural impact. Second, awareness may operate primarily through knowledge and attitude rather than directly influencing behaviours. Users may notice security features (high awareness) but require knowledge to interpret their significance and the attitude to prioritize them. Third, the three awareness items showed conceptual overlap with behavioural indicators (e.g., Q21 “checking certifications” could represent awareness or behaviours), potentially attenuating observed effects. Although its wording may appear action-oriented, it measures cognitive awareness of security features rather than the actual execution of protective behaviours. Fourth, Saudi users place substantial trust in government-endorsed health applications like Sehhaty, which carry official Ministry of Health approval. This institutional trust may reduce perceived need for constant personal vigilance, as users assume government oversight ensures baseline security adequacy. When institutional trust is high, awareness becomes less critical as a direct behavioural driver. Despite its modest direct effect, awareness likely serves as an entry point—users must first notice security features before seeking knowledge about them or developing attitudes toward their importance.

4.4. Saudi Context and Baseline Security Postures

The high mean scores across knowledge (M = 4.22), attitude (M = 3.92), and awareness (M = 4.07) suggest Saudi health app users possess generally positive cybersecurity orientations. This may reflect several contextual factors: Vision 2030’s digital health initiatives, widespread Sehhaty adoption (87.6%), predominantly young demographics (61.4% aged 18–24) with higher digital literacy, and cultural emphasis on privacy values.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

This study offers several strengths that enhance its contribution to understanding cybersecurity behaviours among Saudi health app users. First, the large sample size (N = 629) exceeds PLS-SEM requirements, supporting robust statistical analyses. Additionally, the study employed validated instrumentation from Sawaya et al. [38] with over-claiming detection of response bias. The analytical approach was comprehensive, encompassing both measurement validation and structural path analysis, while the study’s practical relevance aligns closely with Saudi Vision 2030’s digital health objectives. Limitations should be considered, though. First, the sample’s demographic composition limits generalizability. The predominance of young participants (61.4% aged 18–24) and highly educated respondents (62.3% bachelor’s degree holders) does not represent the broader Saudi population, particularly older adults and those with a lower educational background. Younger, more educated individuals typically demonstrate higher digital literacy and more readily translate cybersecurity knowledge into proactive behaviours. This demographic skew inflates observed relationships and overestimates the general population’s capacity to adopt secure practices. Future research should employ stratified sampling across age groups and educational levels to examine how demographics moderate these relationships. Additionally, the geographic concentration of participants in the western region (70.4%) limits generalizability to other regions of Saudi Arabia. The western region includes major urban centres (Jeddah, Makkah, and Madinah). Findings may not apply to populations in less urbanized regions with different levels of digital access and health technology familiarity. Third, while the results only offer an overview of the users’ cybersecurity behaviours, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw cause-and-effect conclusions, as the findings only provide a snapshot of the users’ cybersecurity behaviours. Despite the inclusion of an over-claiming question to address this issue, the use of self-reported questionnaires may result in biassed over-reporting. Finally, while closed-ended survey questions make it convenient to collect quantitative data, they could limit the ability to gain greater insight into users’ personal experiences and data security challenges. To complement these findings, qualitative methodologies might be useful in future research. Future research should employ probability sampling for representativeness, implement longitudinal designs to establish causality, integrate objective behavioural measures from app usage logs, and test interventions experimentally to identify most effective approaches.

4.6. Practical Implications

The findings highlight specific actionable strategies for strengthening cybersecurity in Saudi Arabia’s digital health ecosystem. For Policymakers including the National Cybersecurity Authority and Saudi Health Council, three key interventions are recommended. First, mandate brief interactive security modules within health applications before users access sensitive features. Second, develop age-appropriate training programmes recognizing that knowledge effects diminish among older users, providing hands-on workshops through senior community centres. Third, standardize government-endorsed security certification badges to facilitate user verification.

For App Developers of platforms, three approaches are recommended. First, implement just-in-time contextual prompts when users attempt risky actions, directing them to secure alternatives. Second, simplify privacy policies using three-layered notices ranging from plain language summaries to comprehensive legal details. Third, create personalized security dashboards showing users their security scores with actionable improvement recommendations. The richness of training experiences significantly influences technology acceptance, suggesting that interactive, hands-on training methods may prove more effective than traditional information-delivery approaches [41].

For Healthcare Providers, two strategies are recommended. First, integrate security into clinical workflows by updating intake forms and training staff to address patient security questions. Second, incorporate privacy discussions during consultations to legitimize security as a health concern and provide practical device protection advice. These targeted interventions address the knowledge gaps, attitude formation needs, and awareness deficits identified in this study while accounting for age-based implementation barriers. Successful cybersecurity awareness, education, and training initiatives must address multiple contributing factors including organizational culture, resource availability, and learner engagement to achieve sustainable behavioural change [42,43].

5. Conclusions

Saudi Arabia’s expanding reliance on digital health apps has made cybersecurity a top priority in order to safeguard sensitive patient data. The significance of investigating the behavioural and cognitive elements that influence users’ involvement in cybersecurity activities is highlighted by this study. Designing successful programmes that encourage the safe and ethical use of health technology requires an understanding of these variables. Increasing awareness, promoting good attitudes, and fostering knowledge are important strategies for assisting users in engaging in secure behaviours. Healthcare companies may improve users’ capacity to identify threats, adopt safe practices, and comfortably navigate digital platforms by addressing these areas through focused training, awareness campaigns, and policy advice. These findings illustrate the necessity of organized interventions, especially considering the growing dependence on digital health applications and the sensitive nature of personal health data. By improving users’ knowledge and attitudes, policy support, awareness campaigns, and training initiatives, cybersecurity practices for the entire sector can be improved. In the end, addressing these behavioural factors will help ensure the safe and effective provision of digital health services throughout the kingdom, safeguard patient data, and foster confidence in healthcare technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and T.A.; methodology, A.A.; software, H.M.; validation, H.M.; formal analysis, H.M. and A.A.; investigation, A.A. and M.A.; resources, H.M.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and H.M.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, H.M., M.A. and T.A.; project administration, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU250476].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Faisal University (protocol code KFU-REC-2025-MAR-ETHICS3144 and date of approval 6 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained electronically from all subjects involved in the study prior to survey completion. Participants were required to review the study information and actively confirm their consent before accessing the survey questions.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and confidentiality restrictions, as the dataset contains sensitive participant information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jalali, M.S.; Razak, S.; Gordon, W.; Perakslis, E.; Madnick, S. Health care and cybersecurity: Bibliometric analysis of the literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seh, A.H.; Zarour, M.; Alenezi, M.; Sarkar, A.K.; Agrawal, A.; Kumar, R.; Ahmad Khan, R. Healthcare data breaches: Insights and implications. Healthcare 2020, 8, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikina, S.B. What caused the breach? An examination of use of information technology and health data breaches. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2014, 11, 1h. [Google Scholar]

- Zarour, M.; Alenezi, M.; Ansari, M.T.; Pandey, A.K.; Ahmad, M.; Agrawal, A.; Kumar, R.; Khan, R.A. Ensuring data integrity of healthcare information in the era of digital health. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ewoh, P.; Vartiainen, T. Vulnerability to cyberattacks and sociotechnical solutions for health care systems: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.B.; Fu, K. Cybersecurity concerns and medical devices: Lessons from a pacemaker advisory. JAMA 2017, 318, 2077–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeibagha, F.; Win, K.T.; Susilo, W. A systematic literature review on security and privacy of electronic health record systems: Technical perspectives. Health Inf. Manag. J. 2015, 44, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.; Blum, J. Controlling for cybersecurity risks of medical device software. Commun. ACM 2013, 56, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsemairi, S.S. The reality of cybersecurity and its challenges in Saudi Arabia. Sci. J. King Faisal Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 23, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, A. Measuring the level of cyber-security awareness for cybercrime in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V. Economic consequences of healthcare data breaches: Explore the direct and indirect economic consequences of data breaches in healthcare organizations. Int. J. Core Eng. Manag. 2020, 6, 55–65. Available online: https://ijcem.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/ECONOMIC-CONSEQUENCES-OF-HEALTHCARE-DATA-BREACHES.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Aljedaani, B.; Ahmad, A.; Zahedi, M.; Babar, M.A. Security awareness of end users of mobile health applications: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the 17th EAI International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems, Darmstadt, Germany, 7–9 December 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, Z.A.; Shah, M.H.; Ahmed, J. Information security management needs a more holistic approach: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsdam Mann, S.; Savulescu, J.; Sahakian, B.J. Facilitating the ethical use of health data for the benefit of society: Electronic health records, consent and the duty of easy rescue. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20160130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T.; Tassaddiq, A. Assessment of cybersecurity awareness among students of Majmaah University. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghaibi, H. Barriers to the utilization of mHealth applications in Saudi Arabia: Insights from patients with chronic diseases. Healthcare 2025, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohni, W.; Elfadil, N.; Jarajreh, M.; Gasmelsied, M. Cybersecurity awareness level: The case of Saudi Arabia university students. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaet, D.; Clearfield, R.; Sabin, J.E.; Skimming, K. Ethical practice in telehealth and telemedicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, J.V. Digital technologies and data science as health enablers: An outline of appealing promises and compelling ethical, legal, and social challenges. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 647897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.A. Assessment of cybersecurity knowledge and behavior: An anti-phishing scenario. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Internet Monitoring and Protection, Rome, Italy, 23–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; He, W.; Xu, L.; Ash, I.; Anwar, M.; Yuan, X. Investigating the impact of cybersecurity policy awareness on employees’ cybersecurity behavior. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalem Lahcen, R.A.; Caulkins, B.; Mohapatra, R.; Kumar, M. Review and insight on the behavioral aspects of cybersecurity. Cybersecurity 2020, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donalds, C.; Osei-Bryson, K.M. Cybersecurity compliance behavior: Exploring the influences of individual decision style and other antecedents. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M.; Jerram, C. Determining employee awareness using the Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q). Comput. Secur. 2014, 42, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borate, N.; Gopalkrishna, D.; Shiva Prasad, H.C.; Borate, S. A case study approach for evaluation of employee training effectiveness and development program. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Lythreatis, S.; Singh, S.K.; Cooke, F.L. A meta-analysis of knowledge hiding behavior in organizations: Antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 114963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Silva, C.; Marques, F. An integrated cybernetic awareness strategy to assess cybersecurity attitudes and behaviors in school context. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, R.; Messner, C.; Höchli, B.; Holenweger, G. Employee behavior: The psychological gateway for cyberattacks. Organ. Cybersecur. J. Pract. Process People 2024, 4, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Arshah, R.A.; Ab Hamid, M.R.; Fahmy, S. An analysis on the dimensions of information security culture concept: A review. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 45, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaidi, N.; Balakrishnan, V. Indirect effect of management support on users’ compliance behaviour towards information security policies. Health Inf. Manag. J. 2017, 47, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, P.K.; Handayani, P.W.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Yazid, S.; Aji, R.F. Information security behavior in health information systems: A review of research trends and antecedent factors. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazvini, A.; Shukur, Z. Awareness training transfer and information security content development for healthcare industry. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Gkioulos, V.; Katsikas, S. Developing metrics to assess the effectiveness of cybersecurity awareness program. J. Cybersecur. 2022, 8, tyac006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albediwi, M.R.; Sadaf, K. A Framework for Cybersecurity Awareness in Saudi Arabia. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, T.S.; Anbar, M.; Ebad, S.A.; Karuppayah, S.; Al-Ani, H.A. Theory-based model and prediction analysis of information security compliance behavior in the Saudi healthcare sector. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, A.; Wagimin, W.; Nurlia, N. Enhancing cybersecurity awareness among university students: A study on the relationship between knowledge, attitude, behavior, and training. JSI J. Sist. Inf. (E-J.) 2023, 15, 3139–3149. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya, Y.; Lu, S.; Isohara, T.; Sharif, M. A high coverage cybersecurity scale predictive of user behavior. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 5503–5520. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity24/presentation/sawaya (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Bognár, L.; Bottyán, L. Evaluating Online Security Behavior: Development and Validation of a Personal Cybersecurity Awareness Scale for University Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, L. Predicting Cybersecurity Incidents via Self-Reported Behavioral and Psychological Indicators: A Stratified Logistic Regression Approach. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormac, A.; Zwaans, T.; Parsons, K.; Calic, D.; Butavicius, M.; Pattinson, M. Individual differences and information security awareness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luse, A.; Mennecke, B.E.; Townsend, A. Experience richness: Effects of training method on individual technology acceptance. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaqueu, P.; Mawela, T. Factors contributing to cybersecurity awareness, education, and training. EPIC Ser. Educ. Sci. 2023, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.J. Do hospital data breaches affect health information technology investment? Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076231224164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.