Abstract

In-vehicle voice assistants face usability challenges due to limitations in delivering feedback within the constraints of the driving environment. The presented study explores the potential of Rich Visual Feedback (RVF) on Head-Up Displays (HUDs) as a multimodal solution to enhance system usability. A user study with 32 participants evaluated three HUD User Interface (UI) designs: the AR Fusion UI, which integrates augmented reality elements for layered, dynamic information presentation; the Baseline UI, which displays only essential keywords; and the Flat Fusion UI, which uses conventional vertical scrolling. To explore HUD interface principles and inform future HUD design without relying on specific hardware, a simulated near-field overlay was used. Usability was measured using the System Usability Scale (SUS), and distraction was assessed with a penalty point method. Results show that RVF on the HUD significantly influences usability, with both content quantity and presentation style affecting outcomes. The minimal Baseline UI achieved the highest overall usability. However, among the two Fusion designs, the AR-based layered information mechanism outperformed the flat scrolling method. Distraction effects were not statistically significant, indicating the need for further research. These findings suggest RVF-enabled HUDs can enhance in-vehicle voice assistant usability, potentially contributing to safer, more efficient driving.

1. Introduction

Voice User Interfaces (VUIs) provide an effective means of interacting with systems, particularly in driving environments, where hands-free operation is essential. VUIs play a crucial role in facilitating in-vehicle interaction while driving. However, unimodal in-vehicle VUIs often fail to fully adhere, either partially or entirely, to key usability heuristics, including visibility of system status and user control and freedom [1,2,3]. Additionally, VUIs exhibit several limitations, such as insufficient feedback, which can impede user comprehension and error recognition [4]. Although in-vehicle VUIs are designed to reduce driver distraction, their lack of adherence to usability heuristics and inherent limitations may discourage users from relying on them. As a result, users may revert to interacting with the Graphical User Interface (GUI) via touch, ultimately reintroducing the original issue of distraction. Therefore, enhancing VUI usability and mitigating drawbacks help to promotes not only safety but also user experience. From another perspective, advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have significantly improved the capabilities of voice assistants, enabling them to provide more sophisticated and context-aware feedback. These interactions now extend beyond simple responses to basic commands, requiring more effective means of delivering Rich Visual Feedback (RVF). Furthermore, auditory feedback proved insufficient for advanced tasks like dialing phone numbers and setting destinations; consequently, integrating visual feedback for in-vehicle voice interaction was recommended [5]. While RVF can be easily displayed on devices such as smartphones and personal computers, presenting RVF within a vehicle demands special consideration due to the constraints of the driving environment. Therefore, RVF not only addresses the limitations of unimodal VUIs and enhances their usability, but also supports the growing functional complexity of in-vehicle voice assistants.

Several studies in the literature have attempted to improve the usability of voice interaction in vehicles through different modalities. Some approaches leverage non-visual feedback, such as haptic interaction, to support voice commands while minimizing visual distraction [6]. Others employ visual feedback via the infotainment display to complement auditory input, despite the associated risks of visual distraction [7,8]. Additionally, a growing body of research has explored the use of visual feedback on Head-Up Displays (HUDs), focusing on general interaction with the infotainment system, for example, managing secondary tasks such as climate control [9,10,11]. However, it remains unclear whether presenting RVF on a HUD can effectively enhance the usability of voice interaction. Indeed, comprehensive reviews that are starting to formulate general Human-Machine Interface (HMI) guidelines also underscore the limitations of the existing literature, necessitating further empirical studies on the impact of specific interface designs on driver performance [12]. Furthermore, there is limited research addressing human-centered design considerations for HUD-based visual feedback, particularly in relation to the type and quantity of information that can be meaningfully and safely conveyed to drivers [13].

In this paper, we investigate methods to improve usability and overall user experience by integrating auditory and visual modalities within the vehicle’s HUD. While minimalist UI designs serve as a safe benchmark, the growing complexity of voice assistants necessitates effective methods for presenting richer information without overwhelming the driver. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to directly compare two distinct information-reveal paradigms for displaying RVFs on the HUD. We formulate two research questions to guide our study. RQ1: How do the amount and presentation style of RVF on a HUD affect usability and distraction during in-vehicle voice assistant interactions? RQ2: Does the AR Fusion UI yield significantly higher usability scores than the Flat Fusion UI in a HUD-based environment? In previous research, we proposed three UI designs for RVF on the HUD and conducted an early usability expert evaluation to reduce distraction [14]. In the study presented in this paper, we refine these UIs and conduct a user study to further assess their usability and the distraction they cause to the driver.

To evaluate the usability and distraction of the three RVF UIs, we assessed usability using the System Usability Scale (SUS) and distraction using a penalty point method [15]. We hypothesize that the RVF UI designs will significantly affect both usability and distraction levels. Regarding usability, we formulate the following hypotheses: () there will be no significant difference in SUS scores between the three UI designs; () at least one UI design will exhibit a significant difference in SUS scores compared to the others. Similarly, for distraction, we hypothesize: () there will be no significant difference in distraction penalty points between the three UI designs; () at least one UI design will exhibit a significant difference in distraction penalty points compared to the others. It should be noted that this study used a simulated near-field overlay rather than a physical HUD device. This approach enabled a systematic, controlled exploration of interface principles like visual load and placement, independent of confounding effects from specific optical hardware. This paper aims to provide insights into the usability and distraction of different RVF UI designs to enhance the usability and user experience of voice assistants in vehicles.

To address key gaps in existing research, this paper makes the following novel contributions:

- A novel comparative analysis of HUD-based RVF presentation styles. While prior work has explored visual feedback, this study is the first to directly compare three distinct strategies varying in information density and presentation style: a minimalist keyword-based design, a conventional vertically scrolling list, and a novel Augmented Reality (AR) layered approach.

- An analysis of the effects of different RVF strategies on system usability and driver distraction. This work provides a holistic evaluation by correlating subjective usability ratings, measured via the SUS, with objective driving performance metrics.

2. Related Work

Unimodal in-vehicle VUIs often provide insufficient feedback [16,17], rely heavily on users’ short-term memory [18], suffer from inefficient sequential list navigation [19], and create uncertainty about system comprehension [4], all of which contribute to a suboptimal user experience and reduced effectiveness in complex information delivery. It is important to note that the challenges and limitations of voice-only interaction extend beyond those discussed here, highlighting the need for enhanced multimodal approaches to improve user experience and system usability.

Several studies have explored the usability challenges and limitations of VUIs. One notable and innovative approach to addressing these issues is the integration of tactile modality with auditory modality, enhancing user interaction and feedback mechanisms. Jung et al. introduced a system called Voice+Tactile, which integrates tactile feedback and multi-touch sensing through a device known as the PinPad [6]. This device is capable of delivering high-speed, high-resolution tactile feedback and enables users to fine-tune voice commands or edit inputs. Additionally, the system utilizes tactile cues to indicate its status, such as whether it is actively listening or processing a command. Through the PinPad, users can perform gestures to skip items within long lists, enhancing navigation efficiency. In their study, the authors relied solely on auditory and tactile feedback, deliberately excluding visual feedback to evaluate the effectiveness of this multimodal interaction approach. A comparative user study was conducted between voice-only interaction and the Voice+Tactile system, with findings indicating that the latter significantly reduced distraction and cognitive workload while improving the efficiency of voice interactions. Although this approach represents an innovative and effective method for enhancing the usability and user experience of in-vehicle voice assistants, a notable limitation in human-driven vehicles is the requirement for drivers to keep one hand on the PinPad during interaction, which may impact safety. Moreover, while the system allows users to skip items in long lists, it does not fully mitigate reliance on short-term memory, a key challenge of unimodal voice interfaces. However, this method shows significant potential for application in autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles, where manual control requirements are reduced.

Another approach to enhancing the usability and user experience of voice assistants is the integration of the visual modality. Some studies have implemented a full GUI to complement the VUI, while others have focused specifically on providing visual feedback to support voice interactions. Regarding the full GUI approach, Schneeberger et al. introduced and examined a system called GetHomeSafe (GHS), designed to provide drivers with access to various services while driving [20]. With a minimally designed and intuitive GUI, GHS allows users to browse news, make hotel reservations, and interact with social media platforms like Facebook. The system integrates a speech dialog interface alongside a GUI displayed on an infotainment screen, which is mounted on the vehicle’s center stack. Assessing usability, the researchers compared GHS with a traditional tablet system mounted in the vehicle. The results showed that GHS received more favorable usability ratings than the tablet-based system. Notably, the visual feedback of GHS did not contribute to significant visual distraction, likely due to its carefully designed GUI, which effectively complements voice interaction in driving scenarios. This study demonstrates that a well-structured GUI, specifically optimized for in-vehicle use, can expand the availability of digital services, improve usability, and maintain a low cognitive workload for drivers.

In terms of the visual feedback approach, to which this paper’s research contributes, Braun et al. investigated three methods for visualizing natural language interactions [7]. The first approach involved displaying the full-text transcript of the conversation between the user and the system. The other two methods focused on presenting keywords and icons as visual representations of the interaction. This study utilized an infotainment screen as the display medium. In another paper, Jakus et al. conducted a user study comparing auditory, visual, and audio-visual interactions within vehicles [21]. Their study utilized a conventional hierarchical interface projected onto a HUD for visual feedback. However, the HUD GUI was limited to small, colored text, lacking a dedicated design for HUD environments. Furthermore, Li et al. also investigated in-car interaction, evaluating three systems: handheld iPhone interaction with Siri, steering wheel button activation with Siri voice commands, and steering wheel button activation with Siri visual feedback displayed on the HUD [22]. Furthering the investigation to address usability challenges related to voice interaction, Hofmann et al. explored the use of visual feedback on the infotainment display [8]. This approach aimed to mitigate the short-term memory limitations associated with voice commands by displaying prompts for necessary vocal input, such as driving destinations, thereby assisting users in effectively utilizing voice interaction. In a recent study, Zou et al. investigated the influence of auditory versus audio-visual ADAS feedback on driver behavior and emotional response via a HUD [23]. The experiment compared two conditions: one involving auditory-only reminders (e.g., for over-speeding) and another featuring combined audio-visual reminders. The visual component consisted of an AI-generated avatar whose animations were lip-synced to the spoken audio. Although the audio-visual feedback elicited more positive emotional responses from participants, it offered no informational content beyond that provided by the auditory channel alone. The findings revealed a slight preference for the auditory-only condition, which Zou et al. hypothesized might be attributed to an increased cognitive workload imposed by the redundant visual feedback. While auditory feedback may be adequate for basic alerts, thoughtfully designed visual feedback becomes essential to mitigate the usability drawbacks of voice interaction, particularly when communicating complex data.

The aforementioned studies have explored methods to address the usability and user experience challenges associated with in-vehicle voice interaction by integrating tactile and visual modalities alongside auditory interaction. While the tactile modality has been shown to resolve many usability issues, it still requires the driver to maintain one hand on the tactile PinPad to operate the system, potentially impacting driving safety [6]. Other studies have incorporated the visual modality with varying objectives. Some aimed to provide a comprehensive service by integrating a full GUI [20], while others focused on enhancing usability by presenting visual feedback to support voice interaction [7,8,21,22,23]. Additionally, these studies utilized different display mediums, with some employing infotainment screens as the primary interface and others leveraging the HUD. However, studies that utilized HUD-based displays often failed to incorporate dedicated, human-centered UI designs optimized for HUDs, instead relying on small text, lengthy content, or hierarchical interfaces, which may not be ideal for in-vehicle interaction. It is evident that a dedicated, human-centered approach to designing rich visual feedback on HUDs remains an under-investigated research domain, particularly in the context of improving voice-based interaction in vehicles.

In the following section, we outline the methodology used to conduct the user study, including the evaluation tools, data collection methods, and analysis techniques employed in this research.

3. Methodology

To evaluate the usability and distraction levels of the three RVF UI designs, a user study was conducted in a simulator laboratory at our university (see Figure 1). The entire study, including data collection, was carried out under controlled laboratory conditions. Further details are presented in the subsequent sections.

Figure 1.

The driving simulator utilized for the user study presented in this paper. Button 1 toggles the voice interaction activation state. Buttons 2 and 3 are used to scroll and reveal information. Additionally, the rendered HUD UIs appear on the monitor in front of the driver.

3.1. Interaction and UI Design

Each of the three UI designs was developed with specific goals for information hierarchy and user interaction:

- Baseline UI: A minimalistic, static interface that requires no additional user interaction. This UI provides only minimal visual cues to serve as a benchmark for comparing the performance and usability of other designs (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The three RVF UI designs for the weather query task: Baseline (left), Flat Fusion (middle), and AR Fusion (right).

Figure 2. The three RVF UI designs for the weather query task: Baseline (left), Flat Fusion (middle), and AR Fusion (right). - Flat Fusion UI: An RVF interface design that employs conventional vertical scrolling to reveal additional information that cannot fit within the limited space of the HUD display (see Figure 2).

- AR Fusion UI: An alternative RVF interface design that presents the same information as the Flat Fusion UI but introduces a novel delivery method by leveraging Augmented Reality (AR) to integrate content directly into the driving environment. Instead of displaying information on a single flat plane with traditional scrolling, this UI presents data on layered rectangular planes along the Z-axis from the driver’s perspective, enhancing depth perception and accessibility (see Figure 2).

The Baseline UI was designed in accordance with recommendations from an in-vehicle UI design study, emphasizing minimalist information and layout [8]. In contrast, the two Fusion UIs were developed to examine the feasibility of presenting additional content on the HUD and to explore how richer information could be effectively conveyed through this modality. When the driver inquires about the weather for the day, the voice assistant provides a brief spoken summary. At the same time, more detailed information such as the hourly forecast is displayed on the Fusion UIs (Flat Fusion and AR Fusion). This multimodal approach provides enriched visual feedback, allowing the driver to access additional information at a glance without needing to process a longer auditory response. Although this example illustrates a single type of request, the Fusion UIs are generally designed to present essential information in a concise and accessible manner. This reduces the driver’s reliance on short-term memory and promotes safer, more efficient interaction. It is important to note that both Fusion UIs display the same content. The comparison between them focuses solely on the mechanism used to reveal additional information, with Flat Fusion employing conventional vertical scrolling and AR Fusion utilizing Z-axis scrolling. The Fusion UI designs emphasize human-centered principles to support the evolving capabilities of intelligent in-vehicle voice assistants.

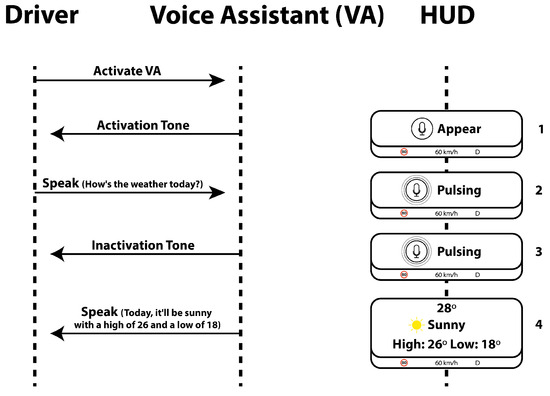

To provide a comprehensive understanding of how our visual feedback integrates with voice interaction, Figure 3 illustrates the interaction procedure step by step.

Figure 3.

The interaction process between the driver and the voice assistant, as well as the information displayed on the HUD during the interaction.

User interaction with the HUD was conducted via buttons on the simulator’s steering wheel (see Figure 1). Button 1 toggled the voice assistant’s activation state. In the fusion UI designs, Buttons 2 and 3 were used to scroll through and reveal additional information. The system was designed with an input timeout; if a participant activated the assistant but provided no voice input for several seconds, the system would automatically deactivate the listening state. This was communicated by hiding the visuals (HUD No. 1 in Figure 3) and issuing the auditory prompt, “Sorry, I didn’t understand, please try again.” Finally, the visual response (HUD No. 4) remained on-screen until the participant manually dismissed it by pressing the activation button again. (Note: A future implementation would ideally include an automatic timeout for this display).

3.2. Simulation and HUD Design

To evaluate the usability of the three designed RVF UIs on the HUD, a driving simulator was developed. Besides usability, distraction while interacting with the voice assistant system was also evaluated. The software used to develop the simulator was Unreal Engine 5 [24]. The driving environment was created to allow participants to interact freely with the infotainment system. For this user study, a three-lane highway populated with several Non-Player Characters (NPCs) was developed. The highway incorporated curves, inclines, and declines to ensure it was not a completely straight route. The NPCs were placed on the right and middle lanes only, which indicates that the left lane is empty all the time. All participants were instructed to drive exclusively in the left lane while performing the preassigned tasks. This approach is motivated by the understanding that, when users are required to perform non-primary tasks (i.e., infotainment interactions), they tend to initiate these actions when the driving situation permits [25]. Therefore, ensuring a suitable driving context for infotainment interaction allows users the autonomy to choose when to engage, without imposing additional extraneous cognitive load. This is particularly important given that the present study focuses on evaluating the usability and distraction levels of the UI designs, rather than measuring cognitive workload directly.

The driving simulator approximated the visual experience of a HUD by rendering the user interfaces as a graphical near-field overlay on the forward-facing monitor (see Figure 1). It should be noted that a true far-focus HUD was not used in this study, as this initial phase aimed to establish a controlled comparison of the UI paradigms themselves, prior to more complex on-road evaluations. Thus, the findings from this simulated environment may not be directly generalizable to real-world driving conditions.

3.3. Data Collection

A quantitative approach was employed to collect usability and driving distraction data. The SUS was used to assess the usability of each UI design. After completing a trial with each UI, participants were provided with a tablet to complete the SUS survey. Driving distraction was evaluated using an ad-hoc penalty point system designed to quantify observable, physical driving errors. The behavioral criteria of this system, such as lane departure and erratic vehicle control, are widely recognized in the literature as valid indicators of driving distraction [5,21,26]. Point values were selected to reflect the relative severity of each type of distraction event on driving safety. For example, high-risk events (e.g., crashes or full lane departures) were assigned the highest penalty (5 points) for complete or near-complete loss of control, while medium-risk events (e.g., abrupt braking or lane marker touches) were assigned intermediate penalties (3 points). While this specific weighting was not empirically derived, the chosen events and their corresponding penalties, detailed in Table 1, represent critical safety-related behaviors. To isolate the effects of the interface, penalty points were recorded exclusively during periods when an RVF was active. Each session was screen-recorded to facilitate this post-session analysis. The limitations of this ad-hoc approach are discussed further in Section 5.10. In addition to this quantitative metric, qualitative data on user preferences were collected through a concluding verbal discussion and documented in writing.

Table 1.

Penalty points assigned for different driving events.

3.4. Participants

A total of thirty-seven participants () were recruited to experience and evaluate the three UI designs. However, five participants were excluded from the analysis as they did not possess a valid driving license. Consequently, the results and analysis presented in this paper are based on data from thirty-two participants (20 male, 12 female), all of whom held a valid driving license and were either students or postdoctoral researchers at our university. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 55 years, with the majority () falling within the 18 to 35-year age group. Some participants had prior experience with in-vehicle HUDs (), while the remaining 23 had no previous experience with HUDs. Although the participant pool consisted primarily of students from a single university, their diverse nationalities encompassed a broad range of driving experiences, cultural backgrounds, and familiarity with in-vehicle technologies. This demographic diversity strengthens the generalizability of our findings, suggesting they are not limited to a specific cultural or user group.

3.5. Procedure and Data Collection

Each user study session was conducted in five distinct phases. The session began with a welcome and demonstration phase, where participants received an overview of the study’s objectives. They were then seated in the driving simulator to familiarize themselves with the controls during a test drive of up to five minutes. Instructions were provided on how to interact with the voice assistant and control the RVF on the HUD. The study then proceeded through three UI evaluation phases. For each UI, participants were instructed to drive in the left lane while completing three predefined tasks at their discretion: checking the weather (see Figure 2), playing music (see Figure A2), and making a phone call (see Figure A1). Upon completing the tasks for one UI, they filled out the SUS questionnaire on a tablet before proceeding to the next interface. The final phase consisted of a short demographic questionnaire and an open discussion, where participants shared their preferences and reasoning regarding the different UI designs. To analyze distraction, each entire session was screen-recorded for a post-hoc analysis based on predefined penalty point criteria.

To prevent bias toward a specific UI, we randomized the order in which participants experienced the three UI designs. The Baseline UI was assigned the number 1, Flat Fusion the number 2, and AR Fusion the number 3. The presentation order followed a rotating sequence:

- The first participant experienced the UIs in the order 1 → 2 → 3.

- The second participant followed the order 2 → 3 → 1.

- The third participant started with 3 → 1 → 2.

- The fourth participant followed the same order as the first (1 → 2 → 3), and this pattern continued for subsequent participants.

This approach ensured a balanced distribution and minimized any potential order effects in the study.

3.6. Analysis Method

In this study, usability and distraction serve as the dependent variables, while the three UI designs function as the independent variables. Given that the study includes three independent variables and each participant evaluated all three UI designs, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA would typically be the appropriate statistical test. However, as the usability and distraction scores violated the normality assumption, a non-parametric alternative, specifically the Friedman test, was employed to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in usability and distraction across the UI designs. Additionally, post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to determine which UI designs differed significantly.

4. Results

The primary factors examined in this user study are usability and distraction. However, additional qualitative data were also collected, including participants’ preferred UI design and their reasons for preference.

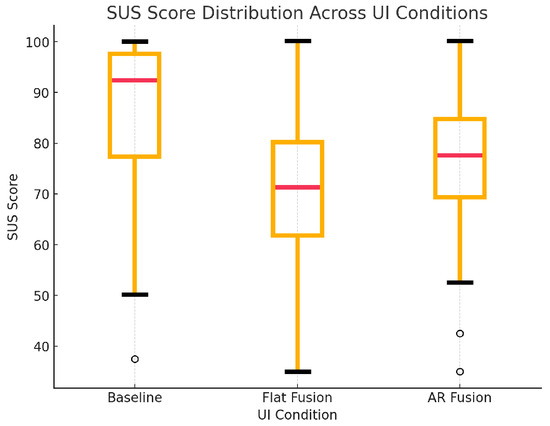

4.1. Usability Assessment

After analyzing the SUS scores from 32 participants () across the three UI designs, the Baseline UI achieved the highest usability rating, followed by the AR Fusion UI, with the Flat Fusion UI ranking the lowest. Based on Jeff Sauro’s interpretation of SUS scores, the Baseline UI achieved an “excellent” usability rating (SUS = 85.7) [27,28]. The AR Fusion UI ranked second, receiving a “good” usability rating, which is considered “acceptable” usability (SUS = 76.64). Meanwhile, the Flat Fusion UI scored the lowest, receiving an “OK” rating, which falls under ‘marginal’ usability (SUS = 69.22).

The SUS scores for the three UI designs violated the normality assumption, as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test (see Table 2). Consequently, a non-parametric alternative to the one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, namely the Friedman test, was employed, with usability as the dependent variable and UI design as the independent variable. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in SUS scores among the three interfaces . Accordingly, the null hypothesis () was rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis (), indicating that at least one UI design exhibited a significant difference in usability. To further examine which UI design contributed most to these differences, post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted. The results showed significant pairwise differences between all three UI designs:

Table 2.

Shapiro–Wilk Normality Tests on Paired Differences of SUS Scores.

- Baseline vs. Flat Fusion

- Baseline vs. AR Fusion

- Flat Fusion vs. AR Fusion

Since all comparisons yielded p-values below the conventional significance threshold (p < 0.05), the results confirm that each UI design differed significantly in perceived usability. To understand the practical magnitude of these differences, an analysis of effect sizes was conducted. The results revealed a medium effect size for the difference between both the Baseline and Flat Fusion UIs () and the Flat Fusion and AR Fusion UIs (), indicating these usability differences are practically meaningful. In contrast, the comparison between the Baseline and AR Fusion UIs yielded only a small effect size (), suggesting that while statistically significant, the actual difference in perceived usability is minor. These findings are supported by the descriptive statistics, with the Baseline UI showing the highest usability (), followed by AR Fusion (), and Flat Fusion showing the lowest (). Figure 4 provides a visual representation of these results.

Figure 4.

SUS scores for the three UIs revealed that the Baseline interface received the highest usability rating, followed by the AR Fusion UI, with the Flat Fusion UI scoring the lowest.

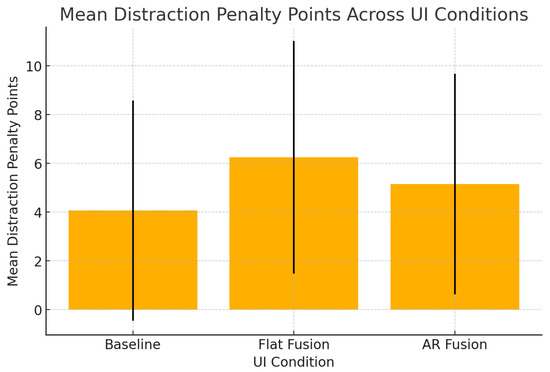

4.2. Distraction Analysis

Driving distraction penalty points were recorded based on the events outlined in Table 1. Among the three UI designs, the Baseline UI exhibited the lowest distraction levels (), followed by the AR Fusion UI (). The Flat Fusion UI was the most distracting, with the highest penalty point average (). Figure 5 presents the overall results for all three UI designs. Additionally, 13 out of 32 participants received zero distraction penalty points in the Baseline UI, compared to 8 participants in the AR Fusion UI and 6 participants in the Flat Fusion UI.

Figure 5.

Distraction penalty points across the three UIs indicate that the Flat Fusion UI accumulated the most penalties, the Baseline UI the least, and the AR Fusion UI scored intermediate values.

Similar to the usability scores, the distraction penalty points violated the normality assumption, as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test, with results indicating non-normality for all conditions: Baseline (, ), Flat Fusion (, ), and AR Fusion (, ). Consequently, the Friedman test was again conducted, with distraction as the dependent variable and UI design as the independent variable. The results indicated no statistically significant difference in distraction levels among the three UI designs . Since the p-value exceeds the conventional significance threshold (p < 0.05), we fail to reject the null hypothesis (), suggesting that UI design did not have a significant effect on distraction penalty points. In conclusion, considering the sample size, the distraction penalty point method appears insufficient to draw definitive conclusions regarding which UI design was more distracting than the others.

4.3. Qualitative Insights

Based on the qualitative data collected at the end of each session, obtained through a short discussion in which participants were asked to indicate their preferred UI design and explain their reasoning, the majority () favored the Baseline UI over the other designs. In contrast, only two participants () preferred the Flat Fusion UI, while seven participants () selected the AR Fusion UI as their preferred choice. The simplicity of the Baseline UI, both in terms of design and information presentation, was cited as the primary reason for its preference. Additionally, participants reported difficulty locating the control buttons necessary for interacting with the Flat Fusion and AR Fusion UIs. This usability challenge likely explains the preference for the Baseline UI, as it required interaction with only a single button (i.e., the voice assistant activation button). This desire for simplicity was clearly articulated by one participant, who described the interface as “clear, not distracting, easy to use”. For the seven participants () who preferred the AR Fusion UI, the primary appeal was its use of progressive information display. This feature allowed them to access additional details on demand, a preference encapsulated by one participant who stated, “It’s simple but also gives more information” (see Figure 6). Additionally, these participants described the Baseline UI as “boring”, expressing a preference for the AR Fusion UI due to its three-dimensional appearance and enhanced visual depth. Overall, the Flat Fusion UI received the most negative feedback. Participants used terms such as “confusing”, “unacceptable”, and “the most distracting”, while some explicitly stated, “I did not like it at all”.

Figure 6.

Visualization of the AR Fusion UI plane transition. Plane 1 presents a primary packet of information, while Plane 2 is subtly hinted at behind it, indicating additional content. When the user chooses to reveal Plane 2, Plane 3 appears in the background to preview further information. The same pattern applies when revealing Plane 3, which brings Plane 4 into the background.

5. Discussion and Future Work

This section interprets this study’s findings, situates them in the context of existing literature, and discusses this study’s limitations and implications for future research and design.

5.1. Usability and Distraction Score Findings

Regarding usability, the statistical analysis of the SUS results confirms that the observed differences are statistically significant and not due to random chance. Therefore, the interpretation of the SUS scores can be considered reliable, following the guidelines established by Sauro and Lewis [27,28]. According to their interpretation, a SUS score of 71.1 or above is considered acceptable, with varying grade levels depending on the score. Scores between 51.7 and 71.0 are considered marginal, while scores below 51.7 are deemed unacceptable. Based on these thresholds, the results of this study indicate that the Baseline UI demonstrated excellent usability (SUS = 85.7), followed by the AR Fusion UI with good usability (SUS = 76.64), and the Flat Fusion UI with marginal usability (SUS = 69.22). These findings support our initial hypothesis stated in the introduction, suggesting that the different RVF UI designs significantly influenced usability. However, as the distraction results did not reach statistical significance, future research is needed to further investigate the distraction levels associated with the three UI designs and to determine how they differ from one another. A larger sample size or the use of alternative evaluation methods, such as measuring cognitive workload, is recommended for more robust findings.

5.2. Safety Implications of RVF Design

Although the analysis of distraction penalty points did not yield statistically significant differences, this metric primarily quantifies physical, rather than cognitive, distraction. An analysis of the interaction paradigms suggests that the three UI designs likely imposed different levels of cognitive workload. The Baseline UI’s minimalist design may have represented the lowest cognitive demand. Furthermore, a key distinction emerged between the two fusion designs: the AR Fusion UI required a simple, discrete action (a single button press) to reveal information, whereas the Flat Fusion UI necessitated a continuous, attention-demanding task (monitoring a scrolling list). This requirement for sustained attention in the Flat Fusion UI may have imposed a higher cognitive load, a factor not fully captured by the penalty point metric.

Displaying RVFs on the HUD offers a distinct safety advantage over traditional infotainment systems by keeping the driver’s gaze directed toward the road. However, a critical safety threshold exists where the potential usability benefits of RVFs are outweighed by the hazardous distraction of information overload. The superior performance of the AR Fusion UI compared to the Flat Fusion UI underscores this point. It suggests that the method of information presentation (in this case, a layered, contextual approach) is as critical to safety as the quantity of information itself.

5.3. Addressing Usability Limitations of In-Vehicle Voice Assistants

Drawing from the literature, this paper highlights several usability limitations commonly associated with unimodal in-vehicle voice assistants [4,16,17,18,19]. One major issue is the lack of sufficient feedback, which makes it difficult for users to determine whether the system is actively listening or processing their input [16,17]. This ambiguity contributes to user uncertainty regarding system comprehension [4]. Such insufficient feedback violates a fundamental usability heuristic “visibility of system status” as defined by Nielsen [2]. Secondly, in-vehicle voice assistants often place a high cognitive load on users’ short-term memory. For example, presenting lengthy lists through voice alone is problematic: it is time-consuming to vocalize, and users struggle to recall or track all listed items [18]. Additionally, the process of navigating and selecting from these lists poses a further usability challenge [19].

This study presents promising solutions that address key usability challenges and enhance the overall effectiveness of in-vehicle voice assistants. By integrating visual elements with auditory interaction (a multimodal approach), the proposed UIs provide graphical feedback on the vehicle’s HUD to indicate system status (see Figure 3). This enables users to discern whether the system is actively listening or processing their input, thereby improving transparency and user trust. Additionally, the RVF UIs present a textual visualization of the interpreted voice command, reducing user uncertainty regarding system comprehension. The visual feedback also alleviates the cognitive burden associated with relying solely on short-term memory. Users can refer back to the information displayed on the HUD, which remains visible for a short duration, supporting user recall during high cognitive load driving situations. Moreover, the multimodal interface effectively addresses the limitations of verbal-only communication when handling lengthy lists. For instance, in scenarios where multiple contacts share the same name, a unimodal voice assistant would have to read out each name sequentially. In contrast, the multimodal approach enables the assistant to verbally prompt the user (e.g., ‘Which contact would you like to call?’) while simultaneously displaying all matching contacts on the HUD. This allows the user to quickly glance at the screen and make a decision without waiting for each option to be spoken aloud. Furthermore, a significant challenge that remains under-explored in the literature is the design of mechanisms for displaying rich information on HUDs without inducing visual clutter. The proposed AR Fusion UI addresses this gap by implementing a progressive disclosure mechanism. By default, the interface presents information in a simplified, abbreviated format. However, it allows the driver to access more detailed information on demand, effectively keeping complex data readily accessible without overwhelming the user’s visual field. It is important to note that the RVF designs do not eliminate auditory interaction; users retain the ability to respond verbally if preferred. For example, in the contact selection scenario, the user may still choose to speak their response rather than interact visually. In this way, the RVF UIs enhance the usability of in-vehicle voice assistants through multimodal support without replacing the core voice functionality.

5.4. Comparison and Research Focus

Compared to prior work in the literature, our multimodal RVF approach integrates the strengths of prior work while avoiding their primary limitations. Current state-of-the-art solutions either rely solely on non-visual feedback that often necessitates manual input, or present custom user interfaces on the infotainment display, which forces the driver to look away from the road [6,7,8,20]. In cases where the HUD is used, the designs are typically not optimized for HUD presentation or are adapted from non-HUD-specific layouts, which reduces their effectiveness [21,22]. However, our approach also presents a significant concern: the potential for cognitive capture and extended task completion times, which may increase visual distraction. Therefore, the current study aims to investigate how the quantity and presentation style of RVF on the HUD affect usability and driver distraction. It also examines which information-revealing mechanism is more effective on a HUD: vertical scrolling or AR layered scrolling.

5.5. The Effect of the Amount and Presentation Style of RVF on Usability and Distraction

The first research question in this study aimed to determine how the amount and presentation style of RVF on a HUD affect usability and distraction during in-vehicle voice assistant interactions. The findings clearly indicate that both the quantity and presentation style of RVF significantly influence the usability of such interactions. This study employed the keyword-icon method in the visual feedback design, following recommendations from previous research [7], which contributed to maintaining acceptable usability scores across all three UIs. Another factor influencing usability was the information-revealing mechanism used, specifically flat vertical scrolling versus AR layered scrolling. This represents a major finding of the study. Although both Fusion UIs contained the same amount of information, the AR Fusion UI achieved higher usability scores than the Flat Fusion UI. This result underscores the impact of presentation style on HUD usability. The Flat Fusion UI presents information in a long, scrollable format, similar to a webpage, where the content exceeds the visible area of the display. In contrast, the AR Fusion UI organizes information into separate stacked layers, each containing a limited but complete message. This structure allows users to access essential content without needing to scroll, unlike the Flat Fusion UI, which may require continuous scrolling to view the full message. This difference in presentation style may also have psychological implications. In everyday contexts, users often scroll through webpages due to varying screen sizes and resolutions, which can result in inconsistent access to complete information. In contrast, the AR Fusion UI ensures that each message fits within a single layer, delivering the key content clearly and consistently. From a development perspective, this method also establishes a uniform visual style across different HUD sizes. Furthermore, in the Flat Fusion scrolling scenario, the responsibility of determining when to stop scrolling falls on the user, potentially increasing cognitive workload and demanding greater visual attention. In comparison, the AR Fusion scrolling scenario requires only a single button press, after which the UI transitions to the next layer containing a complete message. This approach eliminates decision-making and minimizes the visual attention required to access information. Moreover, the AR Fusion UI provides a subtle preview of the next layer by displaying a partially visible line behind the currently revealed layer (see Figure 6). Users then have the option to reveal additional information if needed, which may enhance perceived control and reduce cognitive effort.

Regarding distraction, as the penalty point data did not reach statistical significance, this study cannot fully answer this research question. The findings cannot confirm or deny whether the amount and style of RVF on the HUD influence distraction. However, the large standard deviation (see Figure 5) indicates high variation among participants, with some being very distracted while others experienced little to no distraction. Another possible answer to the statistical insignificance of the distraction penalty points data is that this method primarily measures overt physical driving errors (e.g., lane deviations) and may lack the sensitivity to capture the subtle cognitive distraction imposed by different UI designs. Therefore, further investigation is required to evaluate the distraction side of the three RVF designs on the HUD. An effective objective method for measuring distraction is eye-tracking, through which cognitive workload can be inferred by analyzing fixation and saccade patterns. In parallel, subjective distraction can be measured using questionnaires like the DALI (Driving Activity Load Index), a version of the NASA-TLX tailored for driving environments.

5.6. Usability: AR Fusion vs. Flat Fusion

The second research question in this study aimed to determine whether the AR Fusion UI yields significantly higher usability scores than the Flat Fusion UI in a HUD-based environment. The findings indicate that the AR Fusion UI achieved a higher SUS score (76.64) compared to the Flat Fusion UI (69.22). While the difference may seem modest, these scores place the AR Fusion UI in a higher usability category (“good”) than the Flat Fusion UI (“marginal”), based on the SUS interpretation by Jeff Sauro [27,28]. The observed difference was both statistically significant and practically relevant, confirmed by a medium effect size in a post-hoc analysis. This finding underscores a key conclusion of this study: for information-rich HUDs, the method of information revelation is a critical factor for the user experience, a point further elaborated in Section 5.5.

5.7. Participants Feedback

In addition to the quantitative results on usability and distraction, post-experiment discussions provided valuable qualitative insights. Most participants initially preferred the Baseline UI due to its simplicity. However, when asked which UI they would prefer if more information needed to be displayed, many shifted their preference to the AR Fusion UI, appreciating its layered design that maintained a simple interface while offering access to additional information when needed. A few participants preferred the AR Fusion UI outright, highlighting its visual appeal and seamless integration with the environment. In contrast, the Flat Fusion UI received the least favorable feedback, consistent with its low usability score. Only two participants preferred it, with one citing the familiarity of the scrolling mechanism.

Participants also emphasized the role of steering wheel controls in user interaction. Although these were intended to support hands-on-wheel operation, several participants reported needing to glance at the controls to navigate the Fusion UIs, an issue not present with the Baseline UI, which relied solely on voice commands. This suggests a usability and safety advantage for the Baseline design.

Regular use of the same steering wheel controls in daily driving is likely to lead to the development of muscle memory, enabling drivers to operate them without visual attention. This skill acquisition process is comparable to how users gradually become proficient with a keyboard through repeated use. Additionally, a more intuitive scrolling input method, such as a scroll wheel, could influence usability outcomes. Allowing participants more time to practice or become familiar with the system than the brief trial period provided in this study may also impact the results.

5.8. Visual Simplicity vs. Interaction Workload

A critical analysis of the usability results suggests that the Baseline UI’s success cannot be attributed solely to its visual minimalism. A significant confounding factor appears to be the interaction complexity inherent in the Fusion UI designs. While all interactions began with a voice command, the Fusion UIs mandated an additional physical action, a button press to scroll and reveal information. This extra step introduced a tangible point of friction. Based on observational notes and post-study feedback, participants frequently broke visual contact with the driving scene to locate the scrolling buttons on the complex steering wheel layout (Figure 1). This action, driven by the unfamiliarity of the controls, demonstrably increased the cognitive workload. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the observed usability gap was caused by the simplicity of the Baseline UI’s visual feedback or the complexity of the Fusion UIs’ interaction model. Future work must first decouple these two variables, potentially by using a simplified or more familiar steering wheel interface, to accurately isolate the impact of the HUD design itself.

5.9. Regulatory Considerations and User-Initiated Interaction

A critical consideration for our proposed RVF designs is their relationship with regulatory guidelines, such as UNECE R125 FVA, which restrict non-driving-related visuals in the driver’s primary field of view. To address these safety considerations, our system is built on a transient and user-initiated interaction paradigm. The RVF is designed to be displayed only when the driver actively initiates an interaction with the voice assistant, a model analogous to features in production vehicles where infotainment details are temporarily displayed upon user request. This on-demand approach also respects the natural tendency of drivers to initiate secondary tasks only when the driving situation is perceived as safe [25]. It is crucial to note that the designs evaluated in this simulator study are not intended for immediate implementation; further investigation and validation are required to fully assess their safety and efficiency.

5.10. Summary, Future Work, and Limitations

In conclusion, the findings of this study offer promising insights for the development of voice assistants in vehicles, indicating that rich visual feedback on the HUD is not only feasible but effective from a usability perspective. Based on our results, we recommend offering users the flexibility to choose and switch between the Baseline UI and the AR Fusion UI. The Baseline UI, while simple and easy to use, is limited in terms of the information it can display and does not support additional user actions. As users become more experienced with a system, they often seek or become more capable of managing advanced features. Therefore, incorporating an alternative design variant, such as the AR Fusion design, which supports extended functionality, is essential to accommodate expert users and evolving user needs. This could be implemented as part of the vehicle’s UI customization, similar to how some cars now allow the user to choose between displaying only the speed on the HUD or including more visual information, such as the adaptive cruise control distance. Based on our expert evaluation, SUS usability results, and participant feedback, we suggest that the Flat Fusion UI with its traditional vertical scrolling mechanism may be excluded from future work. However, we acknowledge that it still warrants further evaluation, particularly in comparison to the AR Fusion UI regarding distraction, cognitive workload, and task completion time. As such, our future work will focus on refining all three designs, with particular emphasis on improving distraction management, usability, and user control.

While this study presents encouraging findings for the future of in-vehicle voice assistants, several limitations warrant further investigation. Methodologically, a key limitation of this study is its reliance on an ad-hoc penalty point system to assess driver distraction. The non-significant results suggest that the chosen distraction metric may lack the sensitivity to capture the nuanced differences in cognitive and visual load imposed by the UI designs. Furthermore, the objectivity of these findings is constrained, as the weighting of penalty points was not empirically derived and inter-rater reliability was not assessed. Therefore, future work will employ a multi-faceted approach using standardized measures. This will include objective metrics such as the ISO 17488 [29] Detection Response Task (DRT) and eye-tracking to analyze off-road glance duration and frequency, alongside validated subjective questionnaires like the DALI (Driving Activity Load Index). Adopting these robust methods will allow for a more nuanced and reliable evaluation of driver distraction.

The use of a controlled simulation environment means that on-road evaluations are essential for validating the findings. Real-world driving conditions differ from a simulated environment in that they present a wider range of unpredictable events and environmental stimuli (e.g., adverse weather, pedestrians), which could significantly alter how participants perceive the usability and distraction of a HUD interface. A significant limitation of this study stems from its simulation design. The “near-field HUD” was rendered as a graphical overlay on the same monitor as the forward-facing driving scene (as noted in Section 3.2). Consequently, both the simulated road and the HUD were presented at an identical, fixed focal distance (i.e., the monitor surface). This design, therefore, created an environment requiring effectively zero accommodative shift (re-focusing) from the participant. This represents a critical deviation from real-world driving; a true commercial HUD projects a virtual image at an intermediate distance (e.g., 2–4 m), which requires an accommodative shift between the HUD and the road. This shift introduces a source of visual and cognitive workload that was entirely absent in the simulation.

The scope of this study also presents limitations. Although the sample size was adequate for usability analysis, the participant demographic was skewed toward the 18–35 age group, which may limit the applicability of the results to older user populations. Moreover, the driving simulation took place in a highway setting, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Highway driving demands a lower cognitive workload than urban driving due to the frequent task-switching required in city environments. An interface that is usable and non-distracting in the former context could prove overwhelming or even unsafe in the latter. Therefore, future work is essential to evaluate this study’s designs under the more demanding conditions of urban driving. Lastly, the study focused on three user request types: making calls, media control, and information inquiry. Future research should examine additional voice assistant functionalities, such as calendar scheduling or navigation tasks, which may yield different usability and distraction outcomes.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the feasibility of presenting RVF on a vehicle’s HUD as a means to improve the usability of in-vehicle voice assistants and address existing usability challenges. Three RVF user interfaces were evaluated through a user study conducted in a controlled laboratory environment: the Baseline UI, representing the simplest design; the Flat Fusion UI, which employed a conventional scrolling method to reveal additional information; and the AR Fusion UI, which utilized an innovative augmented reality approach to display additional information through layered, rectangular planes.

A quantitative evaluation was carried out to assess the usability of each UI using SUS, and distraction was measured using a penalty point method. In addition to the quantitative data, brief post-experiment discussions were conducted to gather qualitative insights from participants.

Aligned with the research questions, the key findings indicate that both the amount and presentation style of RVF on the HUD influence usability. The mechanism for revealing additional information also has an impact, with differences observed between a traditional vertical scrolling approach and an innovative AR stacked-layer scrolling method. Usability results, measured through the SUS, reached statistical significance, identifying the Baseline UI as the most usable of the three interfaces. The AR Fusion UI ranked second, while the Flat Fusion UI received the lowest scores. This finding also addresses the second research question, indicating that the innovative AR Fusion UI achieved higher usability ratings than the conventional Flat Fusion UI. Qualitative feedback corroborated these results, with most participants preferring the Baseline design, favoring the AR Fusion UI over the Flat Fusion UI when richer feedback was desired, and expressing clear dislike for the Flat Fusion UI. With respect to distraction, the user study results did not reach statistical significance, preventing a definitive conclusion regarding the influence of RVF amount or presentation style. This finding suggests that further research is necessary to evaluate the potential impact of RVF on driver distraction when displayed on the HUD.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of research on multimodal interaction and in-vehicle human-computer interfaces by demonstrating the feasibility and usability benefits of RVF on HUDs. It should be noted, however, that these findings from a simulated environment (discussed in Section 3.2 and Section 5.10) are not to be generalized to real-world driving scenarios without further validation. The dedicated, human-centered design of the three user interfaces, specifically tailored for HUD environments, plays a significant role in the usability of such visual feedback systems. Based on the findings presented in this paper, future research should prioritize the further development and refinement of the three UI designs. Additionally, further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of RVF on driver distraction, employing alternative methodologies, as well as to assess cognitive workload following design enhancements informed by the insights of this study. Future work may also explore how these design principles can be extended to other automotive display contexts or adapted to different user groups and driving environments, supporting more inclusive and adaptive voice interaction systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and A.E.; methodology, M.B.; software, D.S.-Z.; validation, M.B. and D.S.-Z.; formal analysis, D.S.-Z. and M.B.; investigation, D.S.-Z. and M.B.; data curation, M.B. and D.S.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, M.B. and D.S.-Z.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The SUS scores and distraction penalty points collected during the user study are presented in the Appendices Appendix A and Appendix B of this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by the generous financial support of a scholarship from King Abdulaziz University, to whom the authors extend their sincere gratitude. The authors also wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Simon Eggers and Nikhilraj Chamakkalayil Anilkumar in the development of the simulator virtual environment. The HUD UI design incorporates visual resources from flaticon.com, used in accordance with their licensing terms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| GHS | GetHomeSafe |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| HUD | Head-Up Display |

| NPC | Non-Player Character |

| RVF | Rich Visual Feedback |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| VUI | Voice User Interface |

Appendix A

This appendix illustrates the additional music and calling tasks that participants were asked to perform during the user study, supplementing the weather query task shown previously.

Figure A1.

The three RVF UI designs for the calling task: Baseline (left), Flat Fusion (middle), and AR Fusion (right).

Figure A2.

The three RVF UI designs for the music task: Baseline (left), Flat Fusion (middle), and AR Fusion (right).

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

This appendix presents the SUS scores for each participant in the user study reported in this paper.

Table A1.

The SUS scores for each participan.

Table A1.

The SUS scores for each participan.

| Participant | Baseline | Flat Fusion | AR Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77.5 | 80.0 | 77.5 |

| 2 | 92.5 | 60.0 | 92.5 |

| 3 | 67.5 | 37.5 | 65.0 |

| 4 | 77.5 | 55.0 | 85.0 |

| 5 | 100.0 | 62.5 | 100.0 |

| 6 | 85.0 | 62.5 | 65.0 |

| 7 | 100.0 | 35.0 | 77.5 |

| 8 | 95.0 | 85.0 | 80.0 |

| 9 | 67.5 | 70.0 | 70.0 |

| 10 | 50.0 | 72.5 | 42.5 |

| 11 | 97.5 | 100.0 | 97.5 |

| 12 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 82.5 |

| 13 | 77.5 | 70.0 | 52.5 |

| 14 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 80.0 |

| 16 | 97.5 | 92.5 | 97.5 |

| 19 | 92.5 | 90.0 | 35.0 |

| 20 | 95.0 | 77.5 | 77.5 |

| 21 | 80.0 | 55.0 | 65.0 |

| 22 | 97.5 | 72.5 | 92.5 |

| 24 | 95.0 | 80.0 | 82.5 |

| 25 | 87.5 | 82.5 | 85.0 |

| 26 | 95.0 | 37.5 | 67.5 |

| 27 | 77.5 | 52.5 | 80.0 |

| 28 | 95.0 | 82.5 | 90.0 |

| 29 | 82.5 | 52.5 | 77.5 |

| 30 | 100.0 | 90.0 | 85.0 |

| 31 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 55.0 |

| 32 | 65.0 | 65.0 | 70.0 |

| 34 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 92.5 |

| 35 | 97.5 | 62.5 | 77.5 |

| 36 | 95.0 | 67.5 | 77.5 |

| 37 | 85.0 | 72.5 | 77.5 |

Appendix B.2

This part presents the distraction penalty points for each participant in the user study reported in this paper.

Table A2.

The distraction penalty points for each participant.

Table A2.

The distraction penalty points for each participant.

| Participant | Baseline | Flat Fusion | AR Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 10 | 6 | 9 | 6 |

| 11 | 0 | 10 | 6 |

| 12 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| 13 | 15 | 12 | 15 |

| 14 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 16 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| 19 | 12 | 19 | 15 |

| 20 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| 21 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 22 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 24 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 27 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| 28 | 13 | 6 | 10 |

| 29 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 30 | 10 | 0 | 6 |

| 31 | 6 | 12 | 6 |

| 32 | 0 | 13 | 3 |

| 34 | 3 | 8 | 13 |

| 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 37 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

References

- International Organization for Standardization. Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 110: Interaction Principles. 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Nielsen, J. Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 April 1994; CHI ’94. pp. 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B.; Plaisant, C.; Cohen, M.; Jacobs, S.M.; Elmqvist, N. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Begany, G.M.; Sa, N.; Yuan, X. Factors Affecting User Perception of a Spoken Language vs. Textual Search Interface: A Content Analysis. Interact. Comput. 2016, 28, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, J.; Gong, Z. Evaluation of driver distraction from in-vehicle information systems: A simulator study of interaction modes and secondary tasks classes on eight production cars. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2022, 92, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, S.; Hong, J.; Youn, E.; Lee, G. Voice+Tactile: Augmenting In-vehicle Voice User Interface with Tactile Touchpad Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; CHI ’20. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Broy, N.; Pfleging, B.; Alt, F. Visualizing natural language interaction for conversational in-vehicle information systems to minimize driver distraction. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2019, 13, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Tobisch, V.; Ehrlich, U.; Berton, A.; Mahr, A. Comparison of speech-based in-car HMI concepts in a driving simulation study. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Haifa, Israel, 24–27 February 2014; IUI ’14. pp. 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoon, S.O. User interface for in-vehicle systems with on-wheel finger spreading gestures and head-up displays. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 700–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Ping, S.; Wang, J.; Liang, H.N.; Xu, X.; Yan, Y. AdaptiveVoice: Cognitively Adaptive Voice Interface for Driving Assistance. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; CHI ’24. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X.; Gu, Z. Dora: An AR-HUD interactive system that combines gesture recognition and eye-tracking. In Human Factors in Virtual Environments and Game Design; AHFE Open Acces: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 50, ISSN 27710718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, P.A.R.; Park, J.; Kim, H.K. In-vehicle human-machine interface guidelines for augmented reality head-up displays: A review, guideline formulation, and future research directions. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 104, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Ebert, A. Approaching Intelligent In-vehicle Infotainment Systems through Fusion Visual-Speech Multimodal Interaction: A State-of-the-Art Review. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics 2024, Paris, France, 8–11 October 2024; ECCE ’24. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Ebert, A. Human-Centric Design for Next-Generation Infotainment Systems. In HCI in Mobility, Transport, and Automotive Systems; Krömker, H., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K. (Ed.) VUI Design Principles and Techniques. In Voice Enabling Web Applications: VoiceXML and Beyond; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankelovich, N.; Levow, G.A.; Marx, M. Designing SpeechActs: Issues in speech user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’95, Denver, CO, USA, 7–11 May 1995; pp. 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylett, M.P.; Kristensson, P.O.; Whittaker, S.; Vazquez-Alvarez, Y. None of a CHInd: Relationship counselling for HCI and speech technology. In Proceedings of the CHI ’14 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; CHI EA ’14. pp. 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arons, B. Hyperspeech: Navigating in speech-only hypermedia. In Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Conference on Hypertext—HYPERTEXT ’91, San Antonio, TX, USA, 15–18 December 1991; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeberger, T.; von Massow, S.; Moniri, M.M.; Castronovo, A.; Müller, C.; Macek, J. Tailoring mobile apps for safe on-road usage: How an interaction concept enables safe interaction with hotel booking, news, Wolfram Alpha and Facebook. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Nottingham, UK, 1–3 September 2015; AutomotiveUI ’15. pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakus, G.; Dicke, C.; Sodnik, J. A user study of auditory, head-up and multi-modal displays in vehicles. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 46, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; He, S.; Qu, X. Evaluation of Three In-Vehicle Interactions from Drivers’ Driving Performance and Eye Movement behavior. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 2086–2091, ISSN 2153-0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Khan, A.; Lwin, M.; Alnajjar, F.; Mubin, O. Investigating the impacts of auditory and visual feedback in advanced driver assistance systems: A pilot study on driver behavior and emotional response. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 1499165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epic Games. Unreal Engine 5. Version 5.x. 2021. Available online: https://www.unrealengine.com/unreal-engine-5 (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Braun, M.; Li, J.; Weber, F.; Pfleging, B.; Butz, A.; Alt, F. What If Your Car Would Care? Exploring Use Cases For Affective Automotive User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Oldenburg, Germany, 5–8 October 2020; MobileHCI ’20. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodnik, J.; Dicke, C.; Tomažič, S.; Billinghurst, M. A user study of auditory versus visual interfaces for use while driving. Int. J.-Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J.R. Quantifying the User Experience: Practical Statistics for User Research; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J. 5 Ways to Interpret a SUS Score; MeasuringU: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO Standard No. 17488:2016; Road Vehicles—Transport Information and Control Systems—Detection-Response Task (DRT) for Assessing Attentional Effects of Cognitive Load in Driving. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).