Abstract

In this paper, we present an approach to improve pointing methods and target selection on tactile human–machine interfaces. This approach defines a two-level highlighting technique (TLH) based on the direction of gaze for target selection on a touch screen. The technique uses the orientation of the user’s head to approximate the direction of his gaze and uses this information to preselect the potential targets. An experimental system with a multimodal interface has been prototyped to assess the impact of TLH on target selection on a touch screen and compare its performance with that of traditional methods (mouse and touch). We conducted an experiment to assess the effectiveness of our proposition in terms of the rate of selection errors made and time for completion of the task. We also made a subjective estimation of ease of use, suitability for selection, confidence brought by the TLH, and contribution of TLH to improving the selection of targets. Statistical results show that the proposed TLH significantly reduces the selection error rate and the time to complete tasks.

1. Introduction

Today, we are surrounded by modern touch screens on peripherals of all kinds. However, although touch screens are becoming the central stage of interaction between users and systems, their operation with our fingers creates problems with finger occlusion and imprecision. The situation is worsening with the trend towards miniaturization of devices and enrichment of content, and pointing or selecting small objects on the screen becomes difficult as their number increases [1,2,3]. Since pointing and selecting targets are fundamental and the most executed tasks in graphical user interfaces, improvements in the performance of these tasks can have a significant impact on their usability and on the overall usability of the software [4]. Therefore, improving the quality of Pointing is one major challenge in the area of Human–Machine Interfaces (HMI) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], especially for touch screens where additional problems, such as occlusion, arise during the tactile selection of objects. There, too, numerous works [1,2,3] proposed by researchers testify to the importance of the question of the selection of targets on touch screens.

Our objective is to develop means enabling monitoring maritime situations (such as monitoring of the activity of swarm marine drones) displayed on big touch screens (we consider a screen as a big screen when the user must make large gestures or even must move to reach any point of the screen where the operators must select representations of moving objects on the screens). To make this selection easy for the operators, the systems to be set up must offer possibilities for better human–machine interaction, e.g., by following their gestures and gaze in real time.

The main contribution of this paper is the enhancement of a touch modality for selecting targets by enlightening the target by magnifying it thanks to the gaze of an operator. We show that this enhancement performs as well as the enhancement that can be obtained in the classical case of the use of the mouse.

In Section 2, we will review how multimodal interfaces can improve human–machine interactions for the pointing and selection of targets on screens. Section 3 deals with the technique we propose to enhance target selection and the approach to its implementation, then describe the experimental system designed and presents its prototype. Section 4 describes the experiment carried out with users to evaluate the performance of our proposal, as well as the results obtained from this experiment. Section 5 discusses the relevance of the proposed technique, and Section 6 ends with a conclusion and gives future directions for improving our work.

2. Related Work

In this section, we present some works on multimodal HMIs in general and on targeting and target selection techniques in particular.

2.1. Multimodal Human–Machine Interfaces

To begin with, we are very interested in how multimodal interaction can enhance user interaction with (wide) tactile devices or screens.

In their work presented in [14], Hürst et al. have explored different interaction approaches based on the input of multimodal sensors and aimed at providing a richer, more complex, and more engaging interaction experience. They presented new interaction metaphors for augmented reality on mobile (AR mobile). This work, which has evaluated several multimodal interaction approaches, provides satisfactory and enriching responses in multimodality in HMI. Like these authors, our goal is also to improve multimodal interaction, including tactile interaction and an improvement approach that would use user attention.

As it is not always easy to reach some far parts of wide screens, sometimes head tracking or eye tracking can be used for dome interactions. For example, Pastoor et al. [15] proposed a multimedia system including a 3D multimodal display and an eye-controlled interaction. In this case, eye tracking based on computer vision and head tracking are used in the user interface. The user can interact with the 3D display by simply looking at the object. The head tracker can recognize the movement of the head and open the view of a document at which the user gazed. These works use the gaze to interact with the objects of the interface, which is a great contribution. However, here, eye tracking is carried out by fixed eye trackers, which can limit the size of the screens to be used and reduce the user’s movement possibilities. Likewise, in our situation, it could be interesting to rely on the gaze to improve the selection of targets.

The next step is to assess if gaze tracking can be used alone or should be mixed with other modalities. NaviGaze [16] is a non-intrusive head tracking system for cursor control, associated with blinking recognition to emulate the mouse click. This system makes it possible for a user to continue using a standard mouse and keyboard in addition to the methods mentioned above. These works bring considerable evolution in multimodal interactions, but we are not sure gaze tracking is reliable enough to be used alone in stressful situations where operators have a high workload.

Indeed, the work of Land et al. [17] aims to find out whether the eye movements performed during the performance of a well-learned task are essentially random or are intimately linked to the requirements of the motor task. They offer a system consisting of two video cameras: the first, mounted on the head and responsible for monitoring eye movements; the second, fixed in the room and responsible for recording the user’s activities in said room. Thereafter, the recordings are analyzed image by image. Their conclusion is that the foveal direction was always close to the object to be manipulated, and very few fixings were foreign to the activity concerned (the one being executed). The work carried out has a valuable interest in the study of eye movements when performing a task. However, they make video recordings for a posteriori analysis, which does not meet our expectations for our own context, where gaze tracking must be made at run-time and has not been proven to be as precise as with a posteriori analysis.

After this focus on multimodal interactions and, more specifically, on how gaze tracking can be used to enhance such interactions, the next section is devoted to pointing and target selection.

2.2. Pointing, Cursor and Area, Target Selection

The first step would be to assess if anticipating interaction, thanks to gaze tracking, could limit occlusion during tactile interactions. In [2], Lee dealt with the problem of finger occlusion and printing created by the interaction of fingers with touch screens. This problem worsens with the trend towards the miniaturization of devices and enrichment of content. He proposed a technique that uses an energizing finger probe for selecting objects on the screen and enlarging the display via scaling the visualization to solve occlusion problems. This solution takes into account the fact that an area is created when the finger has contact with the touch screen and that this area is likely to change depending on who uses it and how it is used. He then compared his proposal to a conventional tactile technique using objective and subjective measures. The results showed that the proposed technique had a shorter travel time with small targets and a lower error rate in extreme conditions. This work provides a solution to the thorny problem of occlusion in tactile interactions. It confirms that a good tactile selection technique could benefit from anticipating touch interactions.

On the same topic, Kwon et al. [1] provide a two-mode target selection method (TMTS) that automatically detects the target layout and switches to an appropriate mode using the concept of “activation zone”. An activation zone around the point of contact is created when the user touches the screen. Based on the number of targets within the activation area, TMTS identifies whether the target layout is ambiguous or not and changes its mode to the corresponding ambiguous mode or unambiguous mode. The usability of TMTS has been experimentally compared to that of other methods. The authors explain that during these experiments, TMTS successfully switched to the appropriate mode for a given target layout and showed the shortest task execution time and the least touch input. This work, which gives satisfactory results, takes into account various arrangements resulting from different sizes and densities of the targets on the screen. However, first finger contact with the screen is required to define the area, and then a second touch is required to select the target. It shows that it might be interesting to explore a solution/approach that would have the same effect as the first touch here but without having contact with the screen.

It is also interesting to improve touch performance for selection compared to more classical devices. The studies that Sears and Shneiderman [3] have carried out have compared speed performance, error rates, and user preference scores for three selection devices. The devices tested were a touch screen, a touch screen with stabilization (the stabilization software filters and smooths the raw hardware data), and a mouse. The task was to select rectangular targets of 1, 4, 16, and 32 pixels per side. They proposed a variant of Fitts’ law to predict touch screen pointing times. Touchscreen users were able to point to single-pixel targets, countering widespread expectations of poor touchscreen resolution. The results showed no difference in performance between the mouse and the touch screen for targets ranging from 32 to 4 pixels per side. This work helps to predict the pointing time, which could help to improve touch interactions. Nevertheless, it might be wise to study, in addition to the cases proposed, a situation where the objects would be highlighted.

The Bubble Cursor proposed by Grossman and Balakrishnan [4] aims at enhancing target selection thanks to highlighting targets. It is a new target acquisition technique based on area cursors. The objective of the Bubble Cursor is to improve the zone cursors by dynamically resizing its activation zone according to the proximity of the surrounding targets so that only one target can be selected at a time. Following this proposal, the authors carried out two experiments to evaluate the performance of the Bubble Cursor in the tasks of acquiring 1D and 2D targets in complex situations with several targets and with varying arrangement densities. The results of their work show that the Bubble Cursor considerably exceeds the point cursor and the object pointing technique [8] and that the performance of the Bubble Cursor can be modeled and predicted with precision using Fitts’ law. However, the technique is applied in the case of an interaction with the mouse, and therefore, it would not make it possible to anticipate touch in the case of tactile interaction.

Some works also studied how to enhance the dynamic acquisition of 3D targets. Zhai et al. [12] propose to emphasize the relative effect of specific perceptual cues. The authors have introduced a new technique and have carried out an experiment that evaluates its effectiveness. Their technique has two aspects. First, unlike normal practice, the tracking symbol is a volume rather than a point. Second, the surface of this volume is semi-transparent, thus offering signs of occlusion during the acquisition of the target. Ghost-hunting (GH) [10] proposed by Kuwabara et al. is a new technique that improves pointing performance in a graphical user interface (GUI) by widening the targets to facilitate access. In GH, the goal of the authors is to improve the graphical interface. To do this, they decrease the distance the cursor moves by increasing the size of the targets on the screen. Their technique then shows the guides of the endpoint of the shortest movement trajectory, called ghosts, inside the extended target areas. Users can then optimize their cursor movements by only moving their cursor to ghosts in GH. Unlike other techniques like Bubble Cursor [4], which use the invisible outline of an enlarged target, areas called ghosts are visible to users. This work improves the quality of the interaction, and the authors obtained satisfactory results during an experimental evaluation. On the other hand, this proposal deals with interactions with the mouse only.

Also, considering the dynamic augmentation of the size of the targets, the work carried out by Yin et al. [18] proposes four new techniques for target selection in augmented reality interfaces for portable mobile devices. The goal is to accurately select small targets even when they are occluded. The authors’ main idea is to make a precise occlusive or small selection in augmented reality by selecting a larger and more easily selectable alternative target. An experiment was carried out in which the authors compared the usability, performance, and error rate of the proposed techniques with the existing one, and the results obtained were satisfactory. Yin et al. make a real contribution to the problem of occlusion during tactile interactions. However, instead of having an intermediate target, a contactless approach that would anticipate the selection of the user could improve the quality of the interaction by avoiding, for example, the pre-selection touchdown.

Another 3D pointing facilitation is to rely on Raycasting, such as RayCursor does, proposed by Baloup et al. [19]. They started from the observation that Raycasting is the most common target-pointing technique in virtual reality environments and that this pointing performance on small and distant targets is affected by the accuracy of the pointing device and the user’s motor skills. They proposed improvements to Raycasting, which were obtained by filtering the radius and adding a controllable cursor on this radius to select the targets. Studies have shown that filtering the radius reduces the error rate and that the RayCursor has advantages over Raycasting. RayCursor thus provides an effective solution to the selection of remote objects in 3D environments. However, for use in our context, it might be a good idea to have other additional interaction modalities. Indeed, using Raycasting while being very close to the screen could affect the efficiency of the selection.

PersonalTouch [20] also deals with improving the selection of targets on the touch screen. Customizing accessibility settings improves the usability of the touch screen. They are based on touch screen interactions made by individual users. PersonalTouch collects and analyzes the gestures of these users and recommends personalized and optimal accessibility settings for the touch screen. PersonalTouch significantly improves the success rate of tactile input for users with motor disorders and for users without motor impairments. On the other hand, evaluating the performance of PersonalTouch in the case of an HMI, which would use the highlighting of objects to facilitate their selection, could be a track to explore.

2.3. Synthesis

The work presented in this section has, for some (refs. [14,15,16,17,21,22,23]) contributed to the advances observed in the development of multimodal interactions, as mentioned in the description of the various works and for others (refs. [1,2,3,4,10,18,19,20]) improved the performance of the pointing and the selection of targets, as also explained above. Some of the works have dealt with the problem of head movements [22] and eye movements [15]. On the other hand, it would be interesting to study the possibility of using the head and/or the gaze as input for a new modality or complementing a traditional modality to improve multimodal interactions in general and tactile in particular. This requires the ability to acquire head orientation data in real time. Thus, we are addressing the issue of improving tactile interaction by an approach that would use the user’s attention obtained by tracking his head to obtain an approximate direction of his gaze to anticipate pointing and selection of objects. The questions and objectives that support our study are detailed in the next section.

3. Enhancing Interaction by Anticipating Pointing and Target Selection

This section describes the main principle of the system we propose to enhance selection and pointing, the different interaction modalities used for our proposal, and the system implemented to experiment and evaluate this proposal.

3.1. Anticipating Pointing and Target Selection Using the Orientation of the Head

It is convenient for a touch screen to use an anchor point to represent the location of a touchdown. However, it is a contact area, instead of a point, that forms when the finger touches the screen. The shape of the contact area can also change under various circumstances, as users can use the touch screen with different fingers [24]. Also, with the use of touch screens, there is the occlusion problem [1]. In addition, people of different sexes, ages, or ethnic groups have different finger diameters and different finger sizes, which lead to different target tolerance levels [25]. This justifies work on taking the size of the finger into account in the design of interaction techniques for touch screens. Although the inclusion of finger size in the design of the interaction technique may have untapped potential regarding touch screens, and although several studies have addressed this issue, the problem of occlusion remains and continues to be explored.

According to this state of the art and to the quality that is recognized using the mouse for interactions, three questions arise. First, might it be interesting to define an interaction method based on touch and using a technique allowing the reduction or even elimination of the occlusion problem and which would do as well as the mouse with the same technique? One way would be to add a highlight effect to the touch interaction mode. Second, is it really not possible to do as well with the touch as with the mouse with a highlight effect (for example magnification) on the objects overflown by the cursor? Third, considering that the use of the touch would be done without the presence of a cursor indicating on the screen the place which will be touched (as is the case with the mouse), by what means should we add an effect of highlight for touch? If we would like to see the objects grow, as in the case of the mouse, when we fly over them, we would have to find a way to fly over them for the touch before possibly touching them.

This is why we propose an approach to improve tactile interaction based on anticipating pointing and target selection. The main idea is to use the gaze direction that could be estimated through the head orientation to determine where the attention of the user is and then highlight the objects thus targeted, as using the gaze obtained through an eye tracker is not always so stable and usable [26]. Our work also aims to evaluate the proposed technique using the combination of the mouse and the same highlight effect as a baseline. The goal is to see if adding the highlight to the touch does as well as adding the highlight to the mouse. This assessment will be made on two objective aspects: the rate of errors made and time, and on subjective aspects, such as user preferences.

3.2. Interaction Modalities

To carry out this work, four selection methods are offered to users:

- Mouse: it is used to select objects with a simple click of the left button.

- Touch: a touch screen allows users to select objects by touching them.

- Mouse and Highlight: the selection is made by a simple click on the left mouse button. However, this time, when the mouse cursor rolls over objects, they are magnified to mark their targeting by the user. This notion of highlighting and its operating principle are described in Section 3.3.

- Touch and Highlight: the selection is made by touching the objects. However, this time, the direction of the user’s gaze, given by the orientation of the user’s head, is used to magnify the objects to which the gaze is directed. This is similar to the approach of PowerLens [27], which magnifies the interaction areas on wall-sized displays to reduce the precision required to interact to select data. For this first work, the direction of the gaze is limited to the position on the screen of the central point, which is located between the user’s two eyes. This is retrieved by tracking the position and orientation of the user’s head relative to the screen.

3.3. How Highlighting Works and Its Interest

As proposed in Ghost-Hunting [10], we materialize the highlight by the magnification of the targeted objects. Two levels of highlighting are defined:

- A first level allows the highlighting of objects located within a defined perimeter around the mouse or the orientation of the head (gaze) on the screen. These objects are magnified to have size , being the initial size of the objects.

- A second level allows the highlighting of only one of the previous objects (those located in the perimeter), in this case, the one on which the mouse or the position of the gaze is directed. This object thus pointed is magnified more than the others in the highlighting area. It has a size such that . The objective is to facilitate its selection by the user.

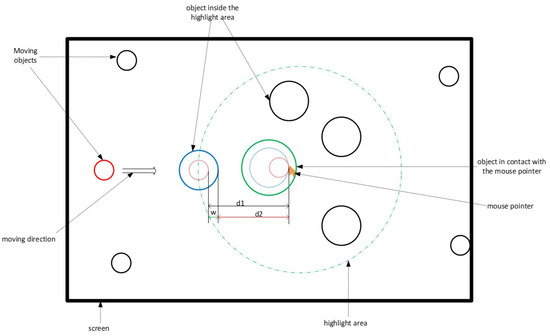

For a first prototype with circles as targets, we choose arbitrarily to double the radius of the target for the first level of magnification, which multiplies by 4 the surface of the target, and to triple it for the second level of magnification, which multiplies by 9 the surface of the target. These values have been chosen arbitrarily and could, of course, be changed. An additional study would be needed to determine which would be the best values for the magnifications. Figure 1 describes how this highlight works.

Figure 1.

Highlight operation mode.

Taking the special case of the red object, when the latter enters the highlighted area, it increases in size (we materialized it by the blue object). Then, when it comes into contact with the mouse (green circle), its size increases again.

The two-level highlighting works as follows:

- First, it preselects a set of potential objects to be treated. This quickly lets the users know whether their mouse or their gaze position is in the correct area (the one where the target object is located). This limits the errors that the user can make, reduces the distance between these objects and the position of the mouse, and thus saves potential time. Based on the diagram of Figure 1, the targeted object here would have had to cross the distance before coming into contact with the mouse if this object had not undergone the highlight effect (red dotted circle). However, with the effect of the highlight (circle in solid blue line), it travels the distance to come into contact with the mouse. There is, therefore, a possible gain in distance , and consequently, in the time taken to select the object since the speed of movement of the object is constant.

- Then, it preselects the only potential object to be treated, distinguishing it from others in the area. This increases the selection area and, therefore, makes the task easier for the user (reduced risk of selection error).

The system and its functioning having been described, we present in the following section its physical structure.

3.4. Description of the Experimental System

The experimentation system is made up of 2 parts: a part that ensures the interaction and a part that takes care of the treatments. The interaction part defines a user activity area in which the user must be for everything to work. This area is delimited by cameras making it possible to locate the user’s position and track the movements of his head using a target that he must carry on his head. There is also a touch screen and a mouse. The processing part consists of a computer on which an application produced with Unity 3D is deployed. This part is responsible for creating, displaying, and managing the movement of objects on the screen, intercepting and interpreting user gestures (click, touch, head orientation), managing the rendering of information according to the actions taken, etc. Figure 2 shows the block diagram of the experimental system. The diagram in Figure 2 gives a general view of the different physical components that make up the system and their interactions and interrelations.

Figure 2.

Physical architecture of the system.

In the diagram in Figure 2, the system is separated into 2 parts, as mentioned above:

- the human–machine interface, consisting of a mouse for selection by click, a touch screen for selection by touch, an HTC Vive virtual reality system for tracking the user’s position, and consisting of 2 lighthouses base stations, 1 headset, 2 controllers, and 1 live tracker target. The lighthouse stations enable the 6 DoF tracking of the headset, controllers, and live tracker target. Here, we use neither the headset nor the controllers for the calibration before the experiment in order to detect the exact size and position of the big screen by selecting each of its 4 corners with a controller. Then, during the experimentation, we use only the live tracker target to track the head and know its position and orientation relative to the big screen). “Lighthouse is a laser-based inside-out positional tracking system developed by Valve for SteamVR and HTC Vive. It accurately tracks the position and orientation of the user’s head-mounted display and controllers in real time. Lighthouse enables the users to move anywhere and re-orient themselves in any position within the range of the SteamVR Base Stations” (https://xinreality.com/wiki/Lighthouse, URL accessed on 8 April 2024). Any other 6DoF 3D tracking system could have been used for our experiment.

- the processing: it is provided by a Unity 3D application.

3.5. Experimental Design and Prototype

To experiment and evaluate the proposed concepts, we used Unity 3D to design a simulator of drones in motion, using the C# programming language for scripting. Drones are represented by 3D objects which move randomly on a flat and delimited surface. At regular time intervals, the system chooses one of the moving objects randomly as the target object. The user is instructed to select this target object each time.

Figure 3 shows the main system interface. We see a set of moving drones, among which one is elected (yellow object) for user selection.

Figure 3.

The main application interface. The drones are visualized as blue cylinders seen from the top, here one is elected (yellow object) for user selection.

We have reviewed the various elements implemented to test our proposal. An experiment was carried out to assess the relevance/impact of the proposal thus made. The following section is devoted to it.

4. Experimentation

We conducted an experiment to evaluate, on the one hand, the performance of the effect of the highlight on the touch and, on the other hand, the performance of the combination (touch, highlight) compared to that of the combination (mouse, highlight). This section deals with this experiment. It is structured in two sub-sections: the first one describes the method used to conduct it, and the second one presents and analyzes the results obtained.

4.1. Method

The chosen method consisted of setting up the experimentation space, defining the task to be accomplished and the procedure, defining the evaluation metrics, and selecting the participants.

4.1.1. Context and Task to Be Accomplished

Adding a highlight effect to the selection using the mouse makes it easier to select objects. The objective of this experiment is to see if, as is the case with the mouse, adding the highlight to the touch improves the selection of objects by touch and if this improvement is similar to what brings the highlight to the mouse. Two measurement criteria are used for this evaluation: the time taken to complete a task and the error rate made during the completion of the task. The scenario defined for conducting this experiment is an observation and supervision activity of drones on a mission. We simulate such a system in which objects representing drones move randomly on a flat surface. In the beginning, all the objects are the same color. At each time step i, defined before the start of the mission, one of the objects is chosen (chosen) randomly by the system and marked with a color, yellow in this case. We call this object the elected or target object. The user must select the chosen object. This object remains available for selection for a period of s (selection time).

Three scenarios arise during the selection:

- the user selects the target object during this time step s: the object changes its color to green for a duration g (good selection time), then returns to the initial color (color at the start of the mission); this is a correct selection.

- the user cannot select the target object during the time step s: the object changes its color to red for a period b (time of bad selection), then returns to the initial color; a selection error is recorded.

- the user selects an unelected object (not the target object): the selected object changes its color to red for a period b, then returns to the initial color; a selection error is also counted.

The total number of objects on the stage, the number of objects to be selected, the selection methods (mouse, touch, etc.), the time between two selections (i), the duration of a selection (s), the duration for which the colors of good (g) or bad selection (b) are maintained, are parameters defined before the beginning of the experiment.

4.1.2. Population

A total of 28 subjects, including 4 women and 24 men, aged from 18 to 40 (18–25: 6, 25–35: 16, 35–40: 6), took part in this experiment. These participants were from 5 different profiles, distributed as follows: 7 undergraduate students, 9 doctoral students, 7 research engineers, 4 post-doctoral researchers, and 1 teacher. They were recruited through an email, which we passed on to the mailing list of our engineering school. Users have not received any reward for this work.

4.1.3. Experiment Settings

Several parameters have been defined: the different methods to be used, the number of objects present on the screen during a passage, the total number of objects that will be selected for a passage, the time available to select an object, the time between a selection and the choice of the next target to be selected, etc. For this experiment, we therefore had:

- 4 methods of selecting objects: mouse, mouse + highlight, touch, touch + highlight (by the orientation of the gaze);

- 3 different densities (total number of objects on the screen) of objects: 10, 30, and 50 objects;

- 10 objects to be selected per mission (passage);

- i = Time between two elections of the target object = 2 s

- s: Hold time of the target object in the “selectable” state by the user = 2 s

- g and b: Respective times of green color after a good selection and red after a selection failure = 1 s.

With this demarcation of the various elements, a mission is limited in time. An example of a mission is defined as follows: its modality (m) = hit, the density of the objects on the screen (d) = 30, the number of objects to select (f) = 10, i = 2 s, s = 2 s, g = b = 1 s. A mission is successful if, before the end of its duration, the user has selected all the f objects. In the example of the previous mission, f is equal to 10.

These durations of 1 s and 2 s have been arbitrarily chosen, and a small pilot with a few colleagues of our research team and from Thales validated that it was putting the experimenters in a high-load but still manageable situation.

4.1.4. Procedure

We established a participant time schedule and a charter that explained the project and the experiment, as well as the rights of the participants. Before starting, each participant was briefed on the purpose of the experiment and the operation of the system to be used for this, then followed by an environmental training phase. During the training, each participant made 4 passages at the rate of one passage for each modality. On each pass, they had 10 objects moving on the screen, among which it was necessary to select 5. This session allowed the participants to familiarize themselves with the environment and especially to understand the purpose of the experiment. During the evaluation session, each participant used the 4 modalities (M: Mouse, MH: Mouse and Highlight, T: Touch, TH: Touch and Highlight), and for each of them, he made 3 passages with 3 different densities of objects: 10, 30 and 50 objects, for a total of 12 passages per participant. Each time, he had to select a total of 10 objects. Questionnaires were also submitted to participants: 1 questionnaire after each modality and 1 final questionnaire on the experiment. For the whole experiment, we had a total number of 28 × 4 × 3, i.e., 336 passages. The order of use of the interaction modalities changed from one participant to another. We have numbered the modalities: 1: M, 2: MH, 3: T, and 4: TH. Then, we built a Latin square with these 4 numbers. The first line of this matrix gives the order of passage M–MH–T–TH.

Based on this principle, we determined 4 passage orders, as shown in Table 1. For these four passages, each modality is used one time at each of the four positions. This order was repeated every four participants; we did 7 repetitions for the 28 participants. Unfortunately, this has only ensured the equitable use of the modalities Touch (with or without Highlight) and Mouse (with and without Highlight) but not of the highlighting and, therefore, not totally reduced the learning effect of the highlight on the results of the experiment. Anyway, as the orders of conditions “with highlight” and “without highlight” are the same for mouse and touch, it does not affect our main objective, which is to compare the enhancement of Touch and Mouse using highlight.

Table 1.

Illustration of the variation of the orders of passage.

At each passage, the mission data were saved in a file for later analysis. In terms of data, we record, among others, the participant’s identifier, the modality used, the density of objects in the environment, the duration of the mission, the state of the mission (success or failure), the number of selections made at total, the number of wrong selections, etc.

4.1.5. Materials and Apparatus

The hardware platform used in this research consisted of:

- a computer running a Windows 7 Enterprise Edition 64-bit operating system; It had an Intel Xeon 3.5 GHz processor, 64 GB of RAM, and an Nvidia Titan XP graphics card;

- a Sony touch screen of size 9/16;

- a mouse;

- a virtual reality system consisting of 1 HTC Vive headset, 2 base stations, 2 controllers, and 1 HTC Vive tracker target.

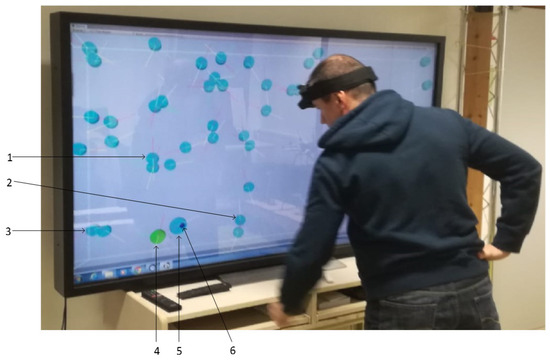

The touch screen was placed vertically on a table so that participants could use touch while standing for the touch modalities. A table and chair were placed in front of the touch screen when the user had to use the mouse modalities. Figure 4 shows a participant during a mission, looking at the target object (yellow color) to select. The direction of his gaze is given by the blue circle on the screen.

Figure 4.

Participant following the object to be selected.

In Figure 5, the user has already selected the object that has turned green. Objects 1, 2, and 3 are outside the highlighted area defined around the position of the gaze. Their size has not changed. On the other hand, object 4, which is the target already selected (green color) and is located in the highlighting area thereof, has a size greater than that of objects 1, 2, and 3 (first level of highlighting). On the other hand, the size of object 4 remains smaller than that of object 5, which now has the gaze direction represented by element 6 (second level of highlighting).

Figure 5.

Target object already selected.

4.1.6. Assessment Metrics

To assess the four interaction modalities, and in particular, to compare the contribution of highlighting with the mouse and the touchscreen, we defined 2 objective criteria (variables of interest): the time taken to complete a mission and the rate of selection errors made during a mission. The various types of selection errors are defined above in Section 4.1.1. We also offered subjective questionnaires to participants.

Completion Time

Mission completion time is a measure of the effectiveness of a modality. Because we consider that performing a task quickly with a modality is a sign of a certain ease of use. Likewise, this means that the modality is well suited to carrying out the task. For each mission, the application records the time taken to complete it for each participant. At the end of a mission, the environment changes color from light gray to dark gray to indicate the end to the participant. The software then ceases to determine the target objects, and therefore, no further selection is possible for the participant.

Selection Error Rate

The rate of errors that occur when selecting objects is also a measure of the effectiveness of the means used for this selection. We consider that the fewer errors made, the less difficulty there is in using this means for the task, and therefore the user is more comfortable. For each mission, the software records each selection or attempted selection made by the participant, distinguishing the good from the bad. More precisely, if we take the case of the mouse, each click made by the participant during a mission is recorded. At the end of the mission, the recording stops. We consider the selection error rate as the number of failed attempts of selections divided by the total number of attempts of selections:

Subjective Questionnaires

Two types of questionnaires were offered to each participant: a questionnaire at the end of each modality to evaluate this modality and an end-of-experimentation questionnaire to compare the modalities and give a general opinion on the experimentation. At the end of the use of a modality, the participant was asked to fill in a questionnaire with a subjective evaluation according to certain criteria, among which are familiarity with the modality, ease of use, self-confidence during use, and tiredness. At the end of the experiment, the participant had to give his opinion on his preferred modality, the least preferred modality, the effect of the highlight on the traditional modalities, etc. Demographic data were also recorded, detailing age, gender, function, and experience with 3D environments.

At the end of the experiments, the data collected were analyzed. The following section presents some results and findings that emerge.

4.2. Results

Using the data collected from the experiment, we carried out a statistical analysis to assess the impact of the factors of selection modality and density of the objects on the scene on our variables of interest, which are the duration of the mission and the rate of mistakes made. Our goal is to compare two modalities (“mouse + highlight” vs. “touch + highlight”) in order to see if the highlight added to the touch allows users to do as well as with the mouse doubtful of a highlight effect. We have conducted ANOVAs. We have 2 interest variables (error rate and completion time) and 2 factors (interaction modality and density of objects) that can influence them. For all our analyses, the risk of the first species chosen is , i.e., a confidence interval of 95%.

4.2.1. Error Rate

Error Rate by Modality

Figure 6 shows the error rate committed according to the interaction modality used.

Figure 6.

Error rate by modality.

The ANOVA carried out shows that the effect of the interaction modality on the rate of errors made during the selection is significant (DF = 3, F = 21.65, p = 7.8 × 10−13). The graph in Figure 6 shows that adding highlighting to the mouse and touch reduces the rate of errors made using these modalities, respectively, for the selection of moving objects. The error rate goes from 27.80% to 10.06% for the mouse and from 38.02% to 24.12% for the touch screen.

The result obtained above gives the general impact of all the conditions on the error rate. To verify that this impact is not the effect of a single modality that dominates all the others, we conducted a Tukey HSD (Tukey multiple comparisons of means) between modalities taken 2 by 2. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detail of the effect of the modalities taken 2 by 2 on the error rate.

As shown in Table 2, by comparing the effects of the interaction methods taken 2 by 2 on the rate of errors made, the impact remains significant. This means that the reductions in the error rate obtained by adding a highlighting effect on the mouse and touch modes, which are observed in the graph in Figure 6, are significant.

Error Rate by Modality and Density

The graph in Figure 7 shows the rate of errors made as a function of the interaction modality and the density of the objects.

Figure 7.

Error rate by modality and by density.

Two observations are made: (i) the error rate increases with density; (ii) although the selection error rate increases with the number of objects present on the scene, adding highlighting to the interaction mode makes it possible to considerably reduce this error rate and therefore improve the quality of selection.

ANOVAs were carried out to judge the relevance of the impact of density on the selection error rates. The 3 of them show that the effect of the interaction modality on the rate of errors made during the selection is significant (p < 0.05). Here again, we conducted Tukey HSDs between modalities taken 2 by 2. Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the results obtained from these analyzes.

Table 3.

Impact of the modalities on the error rate depending on the density.

Table 4.

Detail of the impact of the modalities taken 2 by 2 on the error rate depending on the density.

In Table 3, all p-values are smaller than 0.05. This shows that there is a significant impact between the 2 factors of interaction modality and density of objects on the error rate committed. A comparison of the different modalities gave the results of Table 4.

For a better understanding, we will name the lines by the pairs (Density, comparison case). For example, (10, M/MH) means the results obtained for the comparison between the modalities M and MH for the density 10. Table 4 gives several pieces of information: (i) the line (50, T/M) gives a p-value of . Therefore, from 50 objects on the scene, the difference between the error rate made with the mouse only and the touch alone is not significant; (ii) all the other differences observed in the graphs in Figure 7 are significant. In particular:

- the lines (10, M/MH), (30, M/MH), (50, M/MH) all have p-values less than 0.05. So, regardless of the density of objects in the environment, adding a highlight effect on the mouse significantly decreases the error rate of object selections.

- the lines (10, T/TH), (30, T/TH), (50, T/TH) all have p-values less than 0.05. So, regardless of the density of objects in the environment, the addition of a highlight effect on the touch significantly decreases the error rate of object selections.

4.2.2. Mission Completion Time

We studied the influence of the modality and density factors on the time to complete the mission.

Mission Completion Time by Modality

The graph in Figure 8 shows the variation in the average completion time depending on the modality used.

Figure 8.

Average mission duration by modality.

You can see that adding the highlight to a modality reduces the time taken to complete the mission. We obtain a reduction of 3.60% from 57.44 s to 55.37 s for the mouse and a reduction of 3.20% from 62.62 s to 60.63 s for the touchdown. The ANOVA carried out shows that the effect of the interaction modality on the time duration to complete the mission is significant (DF = 3, F = 95.84, p = 1 × 10−44), so the impact of the interaction modality on the completion time thus observed in the graph in Figure 8 is therefore significant. The result obtained above shows the general impact of all the modalities on completion time. Here again, we conducted a Tukey HSD between modalities taken 2 by 2. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Effect of the modalities taken 2 by 2 on the mission duration.

All the p-values obtained are smaller than 0.05, so we can say that the modality of interaction significantly influences the completion time of a mission, especially when adding highlight to the mouse and touch modes.

Mission Completion Time by Modality and by Density

The graph in Figure 9 shows the average completion times based on terms and densities.

Figure 9.

Average completion time depending on modalities and densities.

We note that although the duration of the mission increases with the density of the objects, adding the highlight to a modality still makes it possible to decrease this duration despite the increase in the number of objects on the scene.

Two other observations are also made: (i) the time to complete a mission increases with density; (ii) although this time increases with the number of objects present in the environment, the addition of the highlighting to the interaction modalities reduces the completion time. ANOVAs were carried out to assess the relevance of this impact of the modality according to the density of the objects. Table 6 summarizes the results obtained from these analyzes.

Table 6.

Impact of modalities on the completion time depending on density.

In Table 6, all p-values are smaller than 0.05. This shows that there is a significant impact of the 2 factors, interaction modality and density of objects, on the mission completion time. The results obtained by comparing the impacts of the modalities taken 2 by 2 for each density are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Impact of the modalities taken 2 by 2 on the completion time depending on the density.

In Table 7, all the comparison cases carried out give a p-value smaller than 0.05. There is, therefore, a significant interaction between the modality and density factors over the completion time, regardless of the density and modality used.

4.2.3. Subjective Questionnaire

As indicated in paragraph Subjective Questionnaires of Section Assessment Metrics, the participants answered a subjective questionnaire at the end of the experiment. The questions contained in the questionnaire made it possible to collect the opinions (ratings) of the participants on various criteria.

The participants first had to give a score between 1 and 5 on the following criteria:

- Ease of use: Would you like to use this modality for the selection of moving objects?

- Suitability for selection: is the modality suitable for the selection of moving objects?

- Complexity: is the selection procedure unnecessarily complicated?

- Size of the objects: is the size proposed for the objects appropriate for their selection?

- Density and difficulty: does the increase in the number of objects in the environment make selection more difficult?

- Self-confidence: what level of confidence did you have when using the modality?

Then, they ended the session by giving their opinion with a score between 1 and 10 on the contribution of the highlight (did the addition of the highlight to the modalities improve/facilitate the selection?). Friedman’s ANOVAs were performed on the questionnaire responses; the observed means and the p-values are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Mean scores and p-values off the subjective data of the experiment.

According to these data, first, the participants found that the highlighted modalities were very easy to use, that they were more suitable for the selection of objects than the traditional modalities, and that they had more self-confidence during the use of highlight. They also found that the size of the objects seemed correct for selection and that the density of the objects in the environment made selection more difficult.

Second, participants found that adding highlighting to a modality greatly improved (average > 8.5 out of 10) the selection of objects. The p-value of this criterion is ; therefore, the difference in sentiment observed in the participants’ response to this question is not significant. In other words, the latter notes that the comfort brought by the addition of highlighting on the mouse and the addition of highlighting on touch for the activity of selecting moving objects is substantially the same in the 2 cases. Finally, when asked which method they preferred, 16 participants, i.e., 57.14%, chose the mouse and the highlight against 12, or 42.86%, for the touch and the highlight.

5. Discussion

In this experiment, the addition of highlighting the traditional mouse and touch modalities brings a clear improvement to the quality of the pointing and the selection of the targets. The error rate made by the participants during the experiment decreased considerably with the addition of highlighting to the touch screen. This rate fell from 38.02% to 24.12% as shown in the diagram in Figure 6, a decrease of 36.56%. This improvement in the quality of the selection brought by the highlighting is significant for both the mouse and the touchscreen. Indeed, the ANOVA on this criterion has given statistically significant results. By observing the distribution of the error rate over the different densities of objects that have been tested, we observe a decrease of 34.64% (from 11.98 to 7.83), 40.73% (from 12.94 to 7.67) and 34.12% (from 13.10 to 8.63), respectively, for the densities 10, 30 and 50 objects, as shown in the graph in the figure ref tab: error-rate-by-modality-detail. So, we can say that in our approach, the quality of the selection seems to be resilient to the increase in the density of objects on the screen. However, for the error rate criterion, the improvement brought by our combination approach (touch, highlight) remains lower than that brought by the combination (mouse, touch), which is 63.81% (decrease from 27.80% to 10.06%). This can be explained by the two main remarks made in the subjective questionnaire by almost all the participants: the touch screen, which did not seem very responsive, and its size, which they found very large. According to the participants, the size of the screen did not allow a large view of the screen when using the touch screen, as was the case when using the mouse (the table was distant from the screen, with a wider angle of view). This undoubtedly justifies the very high error rate with the touchscreen.

The average task completion time has also been improved by adding touch highlighting. We determined the time saved by adding highlighting to a modality, and this was done according to the density of the objects. Table 9 gives details of the differences observed. The data that is expressed in seconds reads as follows: for the cell located in the 2nd row and 2nd column, adding the highlight to the mouse saves 1.73 s for a density of 10 objects.

Table 9.

Comparison of improvement in completion time.

As we can see, we went from 57.44 s to 55.37 s (−2.07 s) for the mouse and from 62.62 s to 60.63 s (−1.99 s) for the touch screen. We, therefore, see that for the completion time criterion, using the direction of the gaze to add a highlight effect makes it possible to do the same as adding the same highlight effect to the mouse.

Statistical analysis of the data collected through the subjective questionnaire shows that the participants felt more comfortable using a modality with highlights than a modality without. Indeed, they found that adding highlighting to a modality made it easier to use and more suitable for selecting objects. For them, the highlight improved the usability of the mouse by 28.28% with an average score increased from 3.57/5 to 4.57/5, and that of the tactile of 38.39% with an average note passing from 3.07/5 to 4.25/5. It also made it possible to make the methods more suitable for the selection of objects, with an improvement of 23.08% for the mouse and 27.73% for the touchscreen. We see that the improvement rate for the two criteria is higher with the touch screen than with the mouse. Participants gained confidence in the performance of their task with the addition of highlighting; they went from an average confidence level of 4/5 to 4.29/5, an improvement of 7.15% for the mouse and from 3.36/5 to 4.14/5, an improvement of 23.41% for touch. This means that the addition of highlighting to the touchscreen seems to triple the users’ confidence in the exercise of their mission with this selection method. Participants found that highlighting as implemented brought them substantially the same level of comfort with the touch as with the mouse. Indeed, the scores assigned, namely 8.93/10 and 8.68/10, respectively, for the mouse and the touchscreen, are not significantly different regarding the results of ANOVA, which gave a p-value of for this criterion. However, participants preferred the use of highlight added to the mouse at 57.14% versus 42.86% for the highlight added to the touch. According to the data extracted from the free comments made by the participants at the end of the experiment, those who preferred the mouse + highlight seemed to justify this unfavorable choice for the touch screen by the quality of the touch screen and its size (size of the interaction interface). It is not so surprising because users are more used to mouse interactions [2], so it is almost normal that the interfaces using the mouse as a mode of interaction are easier to use than with other methods.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we have proposed an approach to improve tactile interaction on big screens based on a two-level highlight, which allows for the anticipation of the pointing and target selection. The approximation of gaze direction obtained by the head orientation is used to determine where the attention of the user is focused on his screen. A perimeter is defined around this position, and all the objects found there are highlighted. If one of the objects thus preselected intercepts the gaze direction, it is differentiated from the others by a second level of highlighting. In this way, we anticipate the user’s action. As detailed in Section 5, the results obtained are satisfactory. The comparative analysis carried out shows that the proposed approach improves tactile interaction in the same way as it improves interaction with the mouse.

Currently, the direction of the gaze is given by the orientation of the head. The use of the actual position of the user’s gaze on the screen could allow greater precision and, therefore, better results in our approach to improving the performance of pointing and target selection. However, note that it is quite difficult to have its gaze fixed in one place by ensuring that the latter does not move. Indeed, the human eye is constantly in motion, and even when we decide to fix a point, it is difficult to stay there. As a result, an object/ray representing the position of the gaze may be unstable on the screen and, therefore, may lack precision in the movements. It could be interesting to compare the performance of a solution using the gaze position with that using the gaze direction to decide. Thus, we intend to use an eye tracker to obtain the position of the gaze and then compare the two approaches. In addition, depending on the results obtained from this first work, eye movements could be envisaged to facilitate pointing tasks and the selection of objects. Finally, to improve our system, we could also develop a contactless interaction based on user gestures.

Author Contributions

V.M.M. contributed to the software, the validation, the investigation, the data curation, and the writing of the original draft. T.D. contributed to the conceptualization, the methodology, the validation, the formal analysis, the resources, the writing (review & editing), the supervision, and the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been funded by a grant from the Brittany region, France, and this work was also supported by French government funding managed by the National Research Agency under the Investments for the Future program (PIA) grant ANR-21-ESRE-0030 (CONTINUUM). We also gratefully acknowledge the support of the NVIDIA Corporation with the donation of the Titan Xp GPU used for this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The code of the prototype used for the experiments and the dataset from the experiment can be found at this address: https://gitlab.imt-atlantique.fr/sos-dm/drone-simulator-head-tracking, URL accessed on 8 April 2024.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in the experiment, without whom this study would not have been carried out, and the beta testers who assessed the quality of the environment and interactions before the launch of the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kwon, S.; Kim, C.; Kim, S.; Han, S.H. Two-mode target selection: Considering target layouts in small touch screen devices. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L. Comparison of the conventional point-based and a proposed finger probe-based touch screen interaction techniques in a target selection task. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, A.; Shneiderman, B. High precision touchscreens: Design strategies and comparisons with a mouse. Int. J.-Man-Mach. Stud. 1991, 34, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, T.; Balakrishnan, R. The bubble cursor: Enhancing target acquisition by dynamic resizing of the cursor’s activation area. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Portland, OR, USA, 2–7 April 2005; pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Baudisch, P.; Cutrell, E.; Czerwinski, M.; Robbins, D.C.; Tandler, P.; Bederson, B.B.; Zierlinger, A. Drag-and-pop and drag-and-pick: Techniques for accessing remote screen content on touch-and pen-operated systems. In Proceedings of the IFIP TC13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Zurich, Switzerland, 1–5 September 2003; Volume 3, pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Blanch, R.; Guiard, Y.; Beaudouin-Lafon, M. Semantic pointing: Improving target acquisition with control-display ratio adaptation. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vienna, Austria, 24–29 April 2004; pp. 519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, A.; Firth, A. Improving the acquisition of small targets. In People and Computers XVII—Designing for Society; Springer: London, UK, 2004; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Guiard, Y.; Blanch, R.; Beaudouin-Lafon, M. Object pointing: A complement to bitmap pointing in GUIs. In Proceedings of the Graphics Interface 2004, Canadian Human-Computer Communications Society, London, ON, Canada, 17–19 May 2004; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kabbash, P.; Buxton, W.A. The “prince” technique: Fitts’ law and selection using area cursors. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 7–11 May1995; pp. 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara, C.; Yamamoto, K.; Kuramoto, I.; Tsujino, Y.; Minakuchi, M. Ghost-hunting: A cursor-based pointing technique with picture guide indication of the shortest path. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2013 International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces Companion, Santa Monica, CA, USA, 19–22 March 2013; pp. 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, A.; Walker, N.; Bharat, K.; Hudson, S. Making computers easier for older adults to use: Area cursors and sticky icons. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta Georgia, GA, USA, 22–27 March 1997; pp. 266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Buxton, W.; Milgram, P. The “Silk Cursor” investigating transparency for 3D target acquisition. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA 24–28 April 1994; pp. 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Conversy, S.; Beaudouin-Lafon, M.; Guiard, Y. Human on-line response to target expansion. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA 5–10 April 2003; pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hürst, W.; Van Wezel, C. Multimodal interaction concepts for mobile augmented reality applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia Modeling, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–7 January 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoor, S.; Liu, J.; Renault, S. An experimental multimedia system allowing 3-D visualization and eye-controlled interaction without user-worn devices. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 1999, 1, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, R.; Cohen, C.J.; Beach, G.; Moody, G. NaviGaze: Enabling access to digital media for the profoundly disabled. In Proceedings of the 33rd Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop (AIPR’04), Washington, DC, USA, 13–15 October 2004; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Land, M.; Mennie, N.; Rusted, J. The roles of vision and eye movements in the control of activities of daily living. Perception 1999, 28, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Fu, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Precise Target Selection Techniques in Handheld Augmented Reality Interfaces. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 17663–17674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloup, M.; Pietrzak, T.; Casiez, G. RayCursor: A 3D pointing facilitation technique based on raycasting. In Proceedings of the the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.H.; Lin, M.T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Ku, P.S.; Taele, P.; Lim, C.G.; Chen, M.Y. PersonalTouch: Improving touchscreen usability by personalizing accessibility settings based on individual user’s touchscreen interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S. A usable real-time 3D hand tracker. In Proceedings of the 1994 28th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 31 October–2 November 1994; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 1257–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Kolsch, M.; Bane, R.; Hollerer, T.; Turk, M. Multimodal interaction with a wearable augmented reality system. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2006, 26, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, K.; Strintzis, M.G.; Tzovaras, D.; Carbini, S.; Bernier, O.; Viallet, J.E.; Raidt, S.; Mancas, M.; Dimiccoli, M.; Yagci, E.; et al. Masterpiece: Physical interaction and 3D content-based search in VR applications. IEEE Multimed. 2006, 13, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, J.; Ryan, N.; Morse, D. Using while moving: HCI issues in fieldwork environments. ACM Trans.-Comput.-Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2000, 7, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.R.; Sheikh, I.H. Finger width corrections in Fitts’ law: Implications for speed-accuracy research. J. Mot. Behav. 1991, 23, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, L.; Ge, L. The applicability of eye-controlled highlighting to the field of visual searching. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, C.; Ruddle, R. Improving Window Manipulation and Content Interaction on High-Resolution, Wall-Sized Displays. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2012, 28, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).