Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore the spatial impact of short-term rental activity on house prices in the city of Athens, Greece. It is well established that the increasing number of short-term rentals has a number of consequences on the functions and living standards in several cities around the world. An aspect that is not studied very often is the effect of short-term rentals on house prices and, especially, the spatial distribution of this effect. In this paper, spatial regression models are presented, incorporating several of the commonly employed house characteristics, such as structural and locational characteristics, with the addition of the short-term rentals as an explanatory factor. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) models, in particular, produce the geographic distribution of regression coefficients, allowing for the study of the short-term rentals’ influence on house prices at the local level. Furthermore, spatial regression models are compared to global linear models. Although global models indicate that short-term rentals have an overall positive contribution on house prices, Geographically Weighted Regression, through the local regression coefficients, reveals spatial patterns with mixed effects, both positive and negative. The greater positive impact is observed in the area around the historical center of the city where short-term rentals’ presence is intense.

1. Introduction

Short-term rentals constitute a very important component of the tourist industry in a great number of cities around the world [1]. The number of these rentals has increased rapidly over the last two decades, and several aspects of this activity have been explored in the relevant literature. One very important finding is the increase in long-term rents for residents, while other important effects, positive or negative, concern the social and economic impact on the neighborhoods that host short-term rentals, as well as the competition with the hotel sector [2,3,4,5]. The increase in house prices related to short-term rentals is also a consequence of this activity. Both the overall influence and the geographic differentiation of the impact on house prices has been explored in a limited number of studies [6,7,8,9,10].

Short-term rentals in Greece appeared around 2010, with only 132 listings in Greece, and almost half of them were around Athens, the capital of Greece. In subsequent years, the number of short-term rentals rapidly increased, especially after 2013, following a significant increase in tourist activity. Currently, only in Athens, the number of offers well exceeds 10,000 [11], while the type of short-term rental activity has shifted from small property owners to companies with a great number of rentals and professional management.

On the other hand, after a period of decreasing prices, house prices, as well as rents, are currently increasing rapidly. There are several factors that can account for this increase, among which a favorable economic environment and, particularly in Athens, short-term rental activity are considered to be important factors for increasing house prices [12].

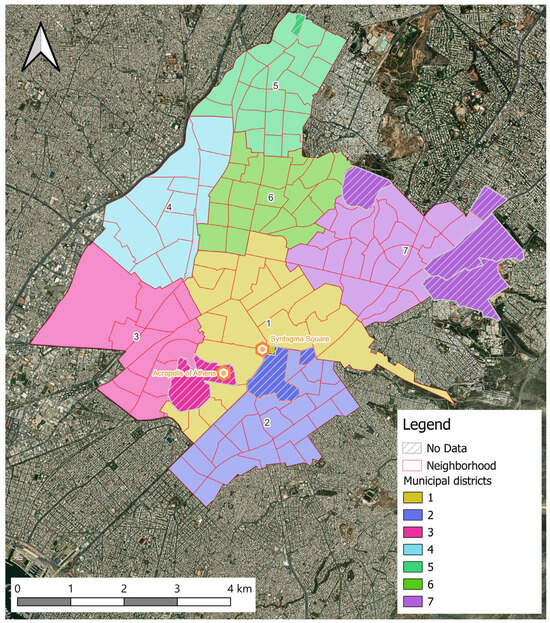

In order to address, among other issues, the shortage of affordable housing, the Greek government has recently adopted several measures, including suspension of new licenses in regions with very intense short-term rentals activity. In Athens, these restrictions are applied since the beginning of 2025 for some parts of the city (municipal districts 1, 2, and 3 in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study region.

Although short-term rentals appear to influence house prices, this issue has not been adequately explored in a global context. Relevant studies for several cities around the world indicate an overall positive effect on house prices, which, however, can be negative in certain parts of the study region. The methods that are employed in order to measure this effect are mostly regression models, which are usually called hedonic models. Hedonic models are several forms of regression models in which property price is the dependent variable and several explanatory factors are the independent variables. Common variables in hedonic models are structural characteristics of the property, as well as locational and neighborhood characteristics [13,14,15,16,17]. In the studies concerning the influence of short-term rentals on house prices, a variable representing the presence of rentals in a region is included as an independent variable. Linear regression models can be transformed in a variety of ways, and they often capture the geographic differentiation of the regression coefficients. Spatial regression models explicitly involve location in the calculation of the regression parameters and are also used as hedonic models for property valuation. Data for short-term rentals are derived from platforms that post listings, mostly the Airbnbplatform.

For example, Thackway et al. [7] presented both linear regression and spatial regression models that indicated that Airbnb’s overall effect was positive for Sydney. The model incorporated Airbnb density at the postcode level, which was combined with a dataset including structural, locational, and neighborhood characteristics of individual residential properties. The authors report that a 1% increase in Airbnb density is associated with a 2.01% increase in property prices. However, spatial regression results indicated that the Airbnb effect on house prices is uneven within the study region, considering that it is negative in certain areas and positive in others. Other forms of regression in some studies also indicate a geographic differentiation of the impact of short-term rentals on prices. For example, Todd et al. [6], in a study of inner London, employed a longitudinal panel dataset, on which a fixed- and random-effects regression was conducted. They used Airbnb and house prices data aggregated in small areal units. House data included structural as well as energy efficiency characteristics. The results indicate that there is a significant and modest positive association between the frequency of Airbnb and the house price per square meter in the study region. More specifically, a unit increase in the number of Airbnb property listings yielded an increase in the house price by £11.59 per m2. However, there is large variability in terms of Airbnb’s impact on house prices, while a negative impact is observed in several parts of the study region. Franco and Santos [8] in a study for Portugal indicated a positive impact of Airbnb on house prices, employing aggregated data for house prices, while the short-term rental variable was the share of Airbnb listings over the total number of dwellings in each areal unit. Using different regression models, it was found that for each unit of increase in the Airbnb share, house prices would increase by approximately 3%. In terms of the spatial differentiation of the Airbnb impact, the authors suggested that strong effects are localized in the historical centers and areas attractive to tourists. Lee and Kim [18], in a study of New York City, examined the economic impact of Airbnb, including rents, housing values, and gentrification. The study used Airbnb characteristics as independent variables in a spatial panel econometric model, which incorporated spatial and temporal effects. The authors concluded that Airbnb has different impacts on local housing markets according to the characteristics of the short-term rentals. It was found that entire home listings by multi-unit hosts have the most significant positive effects on house values, whereas listings by single-unit hosts had an insignificant effect. In addition, room listings by single-unit hosts had a negative relationship with housing value. Garcia-López et al. [9] in a study for Barcelona used Airbnb count and density data at the neighborhood level and, applying several econometric approaches, suggested that there is an increase in transaction prices by 4.6%, while the increase is much higher (17%) in neighborhoods with intense Airbnb activity.

In the city of Athens, the factors affecting housing prices have not been adequately examined in general. There is a limited number of studies, most of which concern the Greater Athens Region, indicating a variety of factors contributing to house prices [19,20,21,22,23]. However, the influence of short-term rentals on house prices has not been estimated, especially in terms of the spatial distribution. The identification of the possible spatial impact of short-term rentals on house prices is useful for all interested parties in the real estate market, especially those concerned with property appraisal, but also for policy making since general restrictions might not be appropriate in all areas. In some areas of Athens, short-term rentals can be favorable for local economies [24].

In the present study, the spatial differentiation of the short-term rentals on house prices is approached through spatial regression models and especially through the spatial distribution of regression coefficients. The overall impact is estimated through Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models, while the spatial distribution is derived through spatial regression models, Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) in particular. These methods are explained in detail in Section 2.3. The research hypothesis is that the presence of short-term rentals has an overall positive effect on house prices, which, however, is spatially differentiated. OLS models support the hypothesis concerning the overall impact, while GWR models indicate that short-term rental activity has both a positive and negative impact on prices in different parts of the study region. Six regression models (three GWR and three OLS) are presented, with different measurements of short-term rental activity (count or density) and logarithmic transformations in four of them. According to the method applied, the magnitude of this impact is represented in different ways, and although it is positive overall, there are negative and positive effects within the study region, which can be quite strong. This study is a contribution to the limited literature concerning the impact of short-term rentals on house prices and its spatial variability, especially for the city of Athens. The results can be important for real estate agents and state institutions regulating this economic activity. Furthermore, a similar methodology can be applied for other cities as well.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Region

The study region is the municipality of Athens, which is the capital of Greece. According to the 2021 Population Census by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (Athens, Greece), there were 637,798 inhabitants, while there was a population decrease in the period 2011–2021. The municipality of Athens is divided into seven municipal districts, which are used for administrative purposes. In addition, some more detailed divisions of the city of Athens are available, which are more appropriate for purposes of statistical analysis. In this study, the division of Athens into 144 neighborhoods is used. However, nine of the designated neighborhoods concern public spaces (parks, archeological sites, and public buildings), and there are no houses in them. Therefore, these neighborhoods do not have any short-term rentals and are not used in the analysis. In Figure 1, the municipal districts, as well as the neighborhoods of Athens, are presented.

2.2. Data

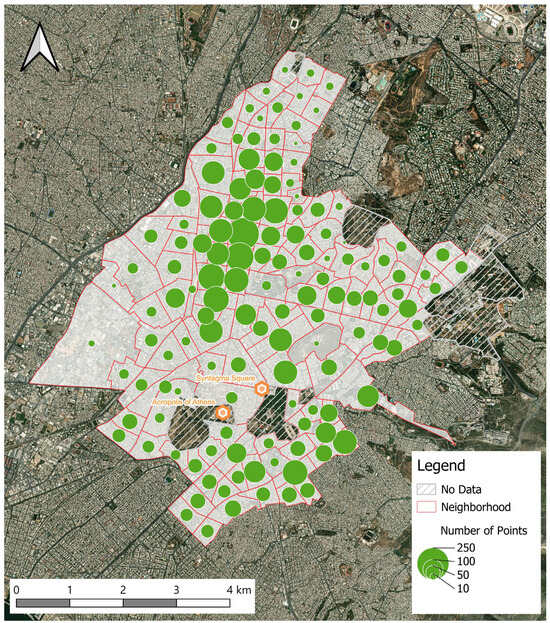

Data on house prices concern asking prices and were obtained from real estate webpages in April 2024. The dataset includes information on price, the type of the property (apartment, terraced houses, and single-family houses), size, year of construction, bedrooms, floor, type and means of heating, a classification as to the energy efficiency, geographic coordinates, and a description of the property in text format. Several of the variables were in text format; thus, data transformations were necessary. Furthermore, additional information concerning missing values—for example, for the floor, as well as new variables, i.e., parking and furnished property—was extracted from the text describing the property. Since the data were large and hard to use manually, an automatization of the process of data extraction was developed, by implementing programming techniques. More specifically, a Python script (ver. 3) was written and executed in order to extract the examined variables and produce an appropriate output in Excel format. Also, two new variables were created using GIS operations (ArcGIS Pro v.3.5.4), regarding the locational attributes of properties, i.e., distances from the city center and the subway stations. Not all the variables were included in regression analysis, mostly because of a large number of missing values or variables with questionable reliability. The initial dataset included 11,460 houses of all types for sale. However, it was necessary to clean the data since a great number of duplicate listings were identified, while several listings concerned non-residential property and were deleted. In addition, listings with obviously wrong values, as well as listings referring to furnished dwellings or listed buildings, were also excluded. In order to have a homogenous dataset, only apartments and terraced houses within residential buildings were retained, while single-family houses were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, a great number of missing values significantly reduced the number of observations. The visualization of the data in a GIS environment indicated many houses either with wrong coordinates, resulting in points out of the study area or within public space, as well as observations with missing coordinates. Therefore, the final dataset for the regression analysis included 8005 houses for sale. In Figure 2, the number of houses for each neighborhood is presented, together with two POIs: the city center (Syntagma square) and the Acropolis archeological site.

Figure 2.

Visualization of number of houses for sale in the neighborhoods of Athens using proportional point symbols.

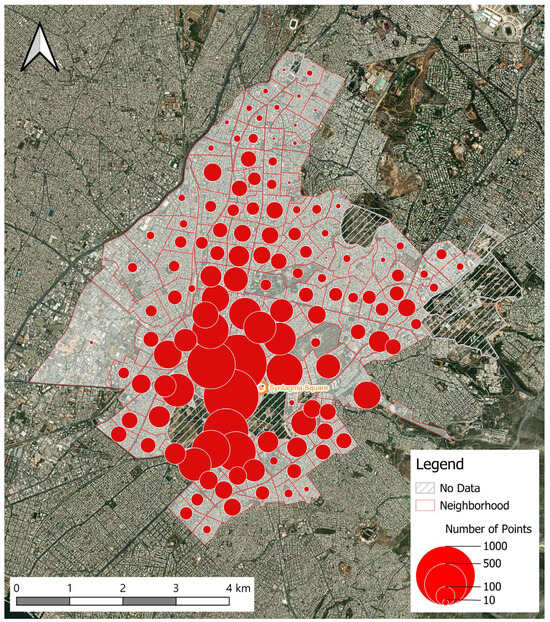

Data on short-term rentals concern listings on the Airbnb platform. Airbnb was the first platform for short-term rentals in Greece, and despite the fact that other platforms, such as Booking and Vrbo, have entered the short-term-rental market in recent years, the largest share of listings is on the Airbnb platform [25]. Data on Airbnb listings are available at insideairbnb.com (accessed on 26 May 2025) for specific dates. In order to compare the Airbnb data with the house dataset, the date closest to April 2024 was selected, i.e., 26 June 2024. There are two files available at insideairbnb.com, a file named “summary information” and a detailed file including more information. For the purpose of this study, the number of listings is needed; therefore, the data provided in the “summary information” file are adequate. The total number of listings was 13,273, and after some corrections for coordinates outside the study area, the final number was 13,257. In addition, the density of listings per hectare (ha) in the neighborhoods of Athens was calculated. In Figure 3, the number of Airbnb listings in the neighborhoods of Athens is presented.

Figure 3.

Visualization of Airbnb listings in the neighborhoods of Athens using proportional point symbols.

Since both datasets (house prices and Airbnb listings) concern individual properties, it is necessary to combine the information in a new dataset. For that purpose, the Airbnb listings were aggregated within the neighborhoods of Athens using GIS operations and a map of the neighborhoods, including Airbnb count and density, was produced. The house map was superimposed over the neighborhood’s map, and two new values were assigned to each house, representing the number and the density of Airbnb listings in the neighboring area, using GIS operations as well.

2.3. Hedonic Regression Models

Hedonic regression models are used in order to predict property prices according to a number of explanatory factors. The results are regression coefficients, which can measure the impact of each characteristic on house prices.

In order to construct a hedonic regression model, it is necessary to describe the variables involved and the relationships among them. Therefore, the variables are described, employing measures of descriptive statistics, such as frequency distributions, the mean, minimum, and maximum.

In terms of the relationship among variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient between house prices and the quantitative variables used as explanatory factors was calculated. In this study (Table 1), the explanatory factors are structural characteristics (size, year of construction, bathrooms, floor, and parking), distances from POIs, as well as the frequency of Airbnb listings (count or density). All the variables are quantitative, with the exception of parking, which is a binary variable, with values “yes” and “no”.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

The most basic hedonic regression model is linear regression, where the dependent variable is a linear function of the independent variables. The model is defined by the constant of the equation and the regression coefficients. The regression coefficient for an independent variable measures the change in the value of the dependent variable for a unit of change in the independent variable. The difference between the value of the dependent variable that is calculated by the model (predicted) and the value in the original dataset (observed) for each observation is the error term (residual). The least squares method is used for the calculation of the linear model, minimizing the sum of the squared residuals for all observations, hence the name Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) [26].

One important assumption for linear regression analysis is that the dependent variable follows the normal distribution. In the case of data expressing property values, it is often observed that the distribution of the dependent variable is right-skewed, because of the existence of extreme values, i.e., houses with extremely high prices. In that case, it is common to apply a logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable [6,16,27,28,29]. This is the case of a log-linear model, in which the regression coefficients are interpreted as percentage changes in the dependent variable for a unit of change in an independent variable. If an independent variable is also skewed, it can be transformed in the same way, resulting in a log-log model, in which the coefficients correspond to percentage changes as well [30].

The results of linear regression analysis include the predicted values and the error term for each observation (residuals), the coefficients defining the equation, as well as diagnostics evaluating the goodness of fit of the model. In multiple regression, the standardized regression coefficients (beta coefficients) are used to compare the importance of independent variables. In terms of evaluating the goodness of fit of the regression analysis, an important measure is the coefficient of determination or R square (R2), which is the squared Pearson correlation coefficient. The coefficient of determination is the ratio of the explained variance over the unexplained variance of the dependent variable. The values of R2 are between 0 and 1 and values close to 1 suggest a small percentage of unexplained variance. The adjusted R2 considers the number of independent variables, and it is used for the comparison of different regression models. In order to obtain statistically significant regression coefficients, multicollinearity issues are considered, avoiding independent variables with strong correlations among them. For that purpose, certain methods have been developed for selecting the variables to be included in the analysis, such as the backward, forward, and stepwise methods [26].

Property data usually include some information about their location. In linear regression, it is possible to incorporate in the analysis the location of houses, usually when data are aggregated in small districts [6,7,8,9]. If the location, in terms of geographic coordinates, is known, other types of regression can be applied, i.e., spatial regression models [31,32,33,34,35]. In spatial regression, location is explicitly incorporated in the calculation of the regression parameters, through the consideration of variable values in neighboring locations, in a GIS environment. Due to spatial autocorrelation, neighboring locations are expected to have similar values, for example, property price, size, and age. According to the type of a spatial regression model, the regression coefficients can be the same for all the study region or vary across it [26,36,37]. Spatial regression models usually result to a better fit, since property values are spatial data and location is an important variable for the calculation of a regression model.

When regression analysis is used for spatial data, such as houses, the observations are certain geographic entities or features, mostly points (the location of each house) or polygons (areal units with several houses). In that context, the linear regression model is often called global, because the regression equation applies to the study region as a whole, while the data for all features have been used for the calculation of the parameters. The residuals are mapped, and they are analyzed to determine whether they follow some pattern, for example, if they are spatially clustered. If the residuals are clustered in space, they are not independent from one another, and this is a violation of an important assumption of regression analysis, i.e., that the residuals are independent. Often, in the analysis of spatial data, the residuals are not independent because of spatial autocorrelation, meaning that their values are similar in neighboring locations. For example, house prices are expected to be similar in neighboring locations, and the residuals might be similar as well. In that case, the OLS regression model is considered as mis-specified, and, in order to obtain accurate results, it is more appropriate to apply spatial regression models that analyze spatial data in a GIS environment. Spatial autocorrelation is measured through the construction of a spatial weights matrix that defines the neighboring locations for each target location, according to contiguity or distance criteria. Measures of spatial autocorrelation, such as the Moran’s I, can be used in order to detect the spatial dependency of the residuals [36].

There are different spatial regression models, and all of them take into consideration spatial autocorrelation for the estimation of the parameters. For example, a new independent variable can be created, which is calculated using the values of the dependent variable for all the neighboring features of each geographic entity. This new variable is a spatially lagged variable and, according to the model, it can be a weighted sum or a weighted average of the neighboring values [36].

Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) is a different spatial regression model that produces different regression equations for each feature. GWR is based on the idea that, in the case of spatially autocorrelated data, the global model does not produce accurate results for all the features engaged in the regression analysis. Therefore, GWR coefficients are not the same in the whole study region, and they are different for each location [37]. Each regression equation engages the observations falling within a bandwidth, which includes the neighboring locations. Moreover, the values of the dependent variable for the observations within the bandwidth are weighted according to their distance from the target location. The spatial differentiation of the regression coefficients in GWR is an expression of the importance of each independent variable in different locations. The maps of the regression coefficients describe the spatial variation in the impact of each variable. In addition, the values of the regression coefficients for each house can produce, through interpolation, raster surfaces to extract the regression coefficients at any location within the study region. Therefore, the value of the dependent variable can be predicted at any location, if the values for the independent variables are known.

In this study, OLS is used as the first step of exploring the relationships of data and the spatial clustering of residuals before the construction of a GWR model. Three OLS models are calculated by setting as dependent variable the house price and as independent variables structural and locational characteristics of the houses as well as the frequency of Airbnb listings. One of the models uses the initial data with no logarithmic transformations, introducing house price as the dependent variable and the number of Airbnb listings in the neighborhood (Airbnb count) as an independent variable. Two OLS models use the logarithmic transformation of two variables: house price and size. In one of them, the Airbnb count was introduced; in the other, the density of Airbnb listings in each neighborhood was entered as an independent variable. In terms of the selection of variables, the backward method is used in OLS, which initially enters into the model all the available independent variables and excludes at subsequent steps each variable with no significant contribution to the coefficient of determination (R2). After testing the OLS residuals for spatial autocorrelation, in all three models the residuals are spatially clustered. Consequently, three GWR models are calculated for the same dependent and independent variables, as in OLS. The results of all models are compared in terms of the explanatory power and the coefficient for the Airbnb frequency. Since the GWR model takes into consideration the inherent spatial dimension of house data, the results are more accurate, as several studies have indicated [20,25,35]. Finally, the regression coefficients from GWR are mapped in order to examine the spatial impact of Airbnb on house prices.

In Section 3, one solution was selected for a more detailed presentation. This is the model with logarithmic transformation of variables and the Airbnb count as an independent variable, since it provides more straightforward interpretation together with good model diagnostics. A statistical analysis was carried out, employing SPSS (PS IMAGE PRO 10 v.29), while ArcGIS Pro v.3.5.4 was used for GIS operations and spatial analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Data Description

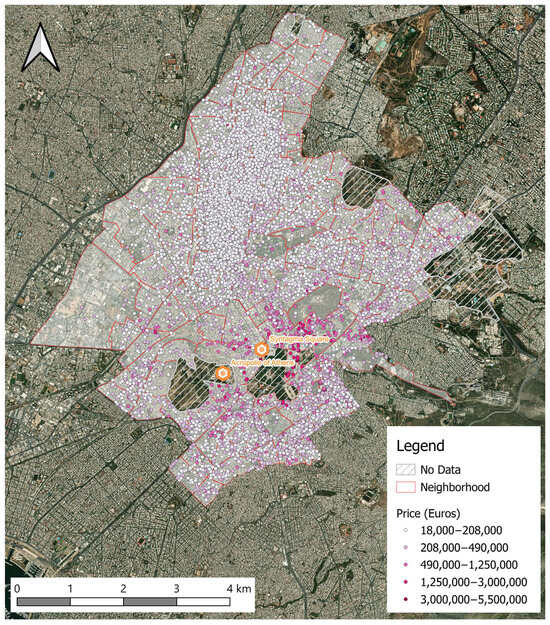

In Figure 4, the distribution of house prices in the study region is presented.

Figure 4.

Visualization of house prices (in Euros) classified into five classes using Natural Breaks (Jenks) method.

In Table 1, the descriptive statistics for all the quantitative variables included in the regression analysis are presented. In addition, one binary variable is included in the analysis as well, the existence of parking space. The results indicate that only 12.6% of the houses have this amenity.

3.2. Correlation and Regression Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients between the house price and all the quantitative variables included in the analysis are presented in Table 2. The correlation coefficients for the rest of the pairs of variables are rather low with the exception of a quite strong negative coefficient between the Airbnb variables and the distance from the city center (−0.596 for the Airbnb count and −0.577 for the Airbnb density). In addition, the correlation between size and bathrooms is rather moderate (+0.474).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients with “price”.

In Table 3, the results of the selected OLS model are presented, with the logarithm of price as the dependent variable and the Airbnb count as an independent variable. After studying the possible transformations for all variables with skewed distributions, the variables “Price” and “Size” were log-transformed. Out of the three trials of regression analysis, this model is considered reliable and more appropriate for interpretation; therefore, detailed results are presented. The coefficient of Airbnb count indicates an increase in house prices of 0,1% for each unit of Airbnb added in the neighborhood.

Table 3.

Regression analysis (OLS).

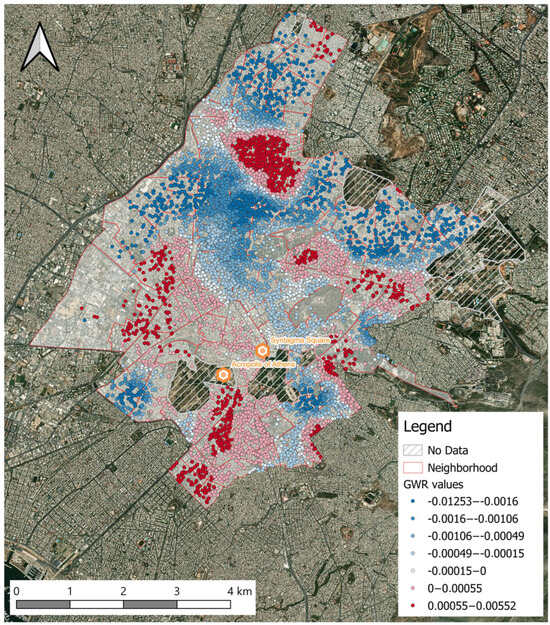

Since the house price is a variable depending on location, the linear regression presented in Table 3 was carried out in a GIS environment as well, in order to produce diagnostics for possible spatial autocorrelation of residuals. The calculation of the coefficient Moran’s I indicated that the OLS residuals are spatially clustered with a p-value < 0.0000001. Consequently, a GWR model was created using the same variables as in OLS. The coefficient of determination (adj. R2) is 0.758. The local regression coefficients for the variable representing the Airbnb count in the neighborhoods are both positive and negative. The positive coefficients are up to 0.006, while the negative ones are up to −0.013, for each unit of Airbnb added in the neighborhood (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Visualization of regression coefficients (GWR) for the Airbnb count classified into seven classes using Equal Interval (Quantile) method.

The second trial of OLS and GWR is performed using Airbnb density as an independent variable (instead of Airbnb count). In that case, the subway distance was excluded from the OLS model, and the coefficient of determination (adj. R2) was 0.596, while the regression coefficient for the Airbnb density was 0.003. The corresponding GWR model showed improvement (adj. R2 = 0.760), while the Airbnb density regression coefficients were both positive and negative, the positive ones up to 0.108 and the negative ones up to −0.362.

Furthermore, OLS and GWR were tested with the original data, with no transformation. The coefficient of determination for the OLS model is R2 = 0.487, and the regression coefficient for the Airbnb count is 187.52 (euros). The coefficient of determination for GWR is much higher (adj. R2 = 0.786), while the Airbnb regression coefficients are both positive and negative. The positive coefficients are up to 2505 euros, and the negative ones are up to −2498 euros for each unit of Airbnb added in the neighborhood.

The results of these regression models are presented in Table 4. The Akaike information criterion is included in this table in order to compare the fit of the models [38].

Table 4.

Comparison of regression models.

In Figure 5, the regression coefficients of the GWR model with dependent variable the logarithm of price and independent variable the Airbnb count are presented. However, the spatial patterns of the coefficients derived from all three models are quite similar.

4. Discussion

The geographical distribution of the houses for sale, as presented in Figure 2, shows a concentration towards the northern and central parts of the city, while prices are higher around the city center (Figure 4). The spatial distribution of the Airbnb rentals is rather different, indicating that most of the rentals are concentrated around the archeological area of Acropolis and in the historical center.

Descriptive statistics suggest great variability in several variables. The mean house price is 222,555 euros, ranging from 18,000 to 5,500,000 euros. The mean size is 83.22 m2, ranging from 9 to 405 m2. The mean number of listings per neighborhood is 119, and the range is between zero and 974, while Airbnb density ranges from zero to 29.7 listings per ha.

The correlation analysis indicated that “Price” has moderate positive correlations with the variables “Size” and “Bathrooms”, i.e., the variables related to the size of the houses. Weaker positive correlations are observed with “Floor” and “Airbnb count”, while a weak positive correlation is found for “Year” and “Airbnb density”. The variables representing distances from POIs have weak correlations, since after some critical distance, for example, a walking distance, the effect is not expected to be proportional to distance.

The OLS model in Table 3 includes eight independent variables, and the fit is quite good (R2 = 0.60). The unstandardized regression coefficients indicate that an added unit of Airbnb facility results in an increase of around 0.1% in house prices, or if 10 Airbnb units are added in a neighborhood, prices will go up by 1%. If Airbnb density is used instead (Table 4), a one-unit increase per hectare leads to a 0.3% increase in prices. Finally, if the original data are used, a one-unit increase in the number of Airbnb results in an increase in prices by 187 euros. Compared to other studies, for example, of Spanish cities [8,9], the percent increase seems lower. However, the level of data aggregation has to be considered. In this study, the Airbnb variable is incorporated into a hedonic regression model, together with size and other structural characteristics which are more important price determinants, as shown in several studies [13]. In addition, after the COVID pandemic, the short-term rentals’ market is probably approaching a peak in terms of offers. Therefore, in earlier years of Airbnb penetration, the impact on house prices might be more obvious.

The results of OLS regression in a GIS environment suggested that the residuals of the model are strongly clustered; therefore, GWR models were constructed. The GWR models greatly improved the model fit, increasing the coefficient of determination in all trials by 16–30%. In addition, the Akaike Information Criterion was reduced in all pairs of OLS and GWR models, supporting the above conclusion.

The spatial distribution of the regression coefficients for the Airbnb count indicate areas with positive and negative regression coefficients. The spatial pattern in Figure 5 was tested, calculating the Moran’s I index, and it was found to be highly clustered, with a p-value < 0.0000001. Positive coefficients mainly form three clusters in all trials of GWR. The largest cluster in terms of area is around the archeological site of Acropolis and the historical center. This result is consistent with the findings for Portugal [8]. A second cluster with large positive coefficients is in the northern part of the study region. This area is characterized by a large number of houses for sale and a low number of Airbnb rentals. It is a densely populated residential area with low house prices (Figure 4) where Airbnb activity seems to be attractive. The third cluster is at the eastern part of the study region, also a residential area with some public facilities and quite low house prices. In both areas a new subway line is under construction, which probably encourages short-term rentals’ activity. In order to obtain a better perspective on the influence of Airbnb in these neighborhoods, a temporal study would be useful, indicating the level of Airbnb penetration over time. Most of the positive coefficients are below 0.1%, but there are several positive coefficients up to 0.6%. Low negative coefficients (less than 0.2%) are observed in some areas with a relatively high concentration of Airbnb units and higher house prices. This finding may reflect the negative social effect that the operation of short-term rentals has on these neighborhoods. On the other hand, the high negative impact, up to 1.3%, is associated with low penetration of Airbnb, mostly in residential areas at the periphery of the municipality. In terms of the magnitude of the coefficients, the GWR model with Airbnb density, instead of count, as an independent variable yields much higher positive and negative coefficients. For each added unit of Airbnb per ha, house prices increase by up to 11% and decrease by up to 36%, respectively. In both log-transformed models, the large negative coefficients are higher than the large positive ones.

According to the level of aggregation of the data and the way Airbnb listings are introduced as an independent variable, the results in terms of estimating the effect of Airbnb on house prices are different. It can be measured in euros or as a percentage increase in property price. Also, if the count of listings or the density is used in the regression model, the results are also different. In all cases, the logarithmic model yields a better fit, when OLS is performed, while the GWR model yields more accurate results when compared to the corresponding OLS models. Moreover, the GWR model produces the spatial variation in Airbnb coefficients, and it is interesting that although the OLS models result in a positive coefficient, the GWR models suggest both positive and negative coefficients. This conclusion agrees with similar studies in other cities [6,7].

The spatial differentiation of the Airbnb impact on house prices is a very useful finding for policy making and suggests that blanket restrictions of short-term rental activity might probably be examined in more detail in the light of the different socioeconomic conditions in the neighborhoods of Athens. Such restrictions for the city of Athens have already been imposed. New permits for three municipal districts around the center of Athens have been suspended for the year 2025, and this measure is expected to be extended to 2026. The results of this analysis, however, indicate that there is a substantial spatial differentiation in the Airbnb impact on house prices; therefore, a more detailed approach might be more useful, since there are neighborhoods that still have the capacity to accommodate this activity.

Future research might further explore the positive and negative effects of the short-term rentals on house prices. In that respect, the Airbnb dataset could be examined not only in terms of the number or the density of the rentals but also in terms of the type of the dwellings and the number of listings per host. Previous research [18] concluded that entire home listings by multi-unit hosts were found to exhibit the greatest impact on rent, housing value, and gentrification. Multi-unit hosts treat property as an investment, while hosts with fewer units may use their property for their personal needs and rent it occasionally. The distinction between areas with multi-unit hosts and those with fewer units, mostly residential areas, could further explain the differences in the Airbnb impact on house prices. In predominantly residential areas, it is more likely for short-term rentals to create social problems in the buildings and the neighborhood. Finally, it would be useful to incorporate some temporal data in the analysis, especially for Airbnb listings, so that the magnitude of the Airbnb coefficients could be estimated according to the history of short-term rental penetration in each neighborhood. Temporal effects, in general, are subject to data limitations in Greece, since relevant data are not provided by an official source in a regular, uniform, and reliable configuration.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study is to estimate the spatial effect of short-term rentals on house prices in the city of Athens. The methodology adopted is the construction of a spatial regression model, with a measure of Airbnb activity as an independent variable. Several trials of linear regression resulted in a log-transformed linear model with quite good explanatory power. Since houses are spatial data, a spatial regression model improved the model fit, while it produced spatially varying regression coefficients for the Airbnb variable. While the overall effect of Airbnb on house prices is positive, GWR indicated areas with positive and negative coefficients, which, according to the measurement of Airbnb, count or density, can be quite large. Moreover, according to the way short-term rental activity is measured, the level of data aggregation, and the model employed, the results will be different, and it is difficult for this study to be compared with similar studies for other cities. Further research might concentrate on explaining the differences among the parts of the city and in this way identify areas with no more capacity for short-term rentals and others that might benefit from this economic activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.I.; data curation, P.I., V.K. and K.K.; formal analysis, P.I.; investigation, K.K.; methodology, P.I.; software, V.K. and K.K.; visualization, V.K.; writing—original draft, P.I.; writing—review and editing, P.I. and V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Open data used in this study are extracted from the websites: http://insideairbnb.com/ (accessed on 26 May 2025), https://www.data.gov.gr/ (accessed on 31 August 2025) and https://www.statistics.gr (accessed on 30 July 2025). The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author at piliop@uniwa.gr.

Acknowledgments

We thank Konstantinos Lykostratis (University of West Attica and Savills, Greece), for his valuable insights during the discussion of our results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression |

| ha | hectare |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| POIs | Points of Interest |

References

- Adamiak, C. Current state and development of Airbnb accommodation offer in 167 countries. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 25, 3131–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayouba, K.; Breuillé, M.-L.; Grivault, C.; Le Gallo, J. Does Airbnb Disrupt the Private Rental Market? An Empirical Analysis for French Cities. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2019, 43, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Yeung, T.Y. Understanding AirBnB in Fourteen European Cities. In Proceedings of the Tenth IDEI-TSE-IAST Conference on The Economics of Intellectual Property, Software and the Internet, Toulouse, France, 12–13 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Ye, Q.; Law, R. Effect of sharing economy on tourism industry employment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J. The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Musah, A.; Cheshire, J. Assessing the impacts of Airbnb listings on London house prices. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 49, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackway, W.T.; Ng, M.K.M.; Lee, C.-L.; Shi, V.; Pettit, C.J. Spatial Variability of the ‘Airbnb Effect’: A Spatially Explicit Analysis of Airbnb’s Impact on Housing Prices in Sydney. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.F.; Santos, C.D. The impact of Airbnb on residential property values and rents: Evidence from Portugal. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 88, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.; Jofre-Monseny, J.; Martínez-Mazza, R.; Segú, M. Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 119, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B.; Tussyadiah, I. What Airbnb does to the housing market. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inside Airbnb. Available online: http://insideairbnb.com/get-the-data (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Bank of Greece. Financial Stability Review. October 2025. Available online: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/ekdoseis-ereyna/ekdoseis/anazhthsh-ekdosewn (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Khoshnoud, M.; Sirmans, G.S.; Zietz, E.N. The Evolution of Hedonic Pricing Models. J. Real Estate Lit. 2023, 31, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmans, S.; Macpherson, D.; Zietz, E. The Composition of Hedonic Pricing Models. J. Real Estate Lit. 2005, 13, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranzini, A.; Ramirez, J.; Schaerer, C.; Thalmann, P. Hedonic Methods in Housing Markets: Pricing Environmental Amenities and Segregation; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmans, G.S.; MacDonald, L.; Macpherson, D.A.; Zietz, E.N. The Value of Housing Characteristics: A Meta Analysis. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2006, 33, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Webster, C. Urban Morphology and Housing Market; Springer Geography; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H. Four shades of Airbnb and its impact on locals: A spatiotemporal analysis of Airbnb, rent, housing prices, and gentrification. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, D.; Antoniou, C. How Do Transport Infrastructure and Policies Affect House Prices and Rents? Evidence from Athens, Greece. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2013, 52, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, P.; Feloni, E. Spatial Modelling and Geovisualization of House Prices in the Greater Athens Region, Greece. Geographies 2022, 2, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, P.; Stratakis, P. Spatial analysis of housing prices in the Athens Region, Greece. Int. J. Real Estate Land Plan. 2018, 1, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimis, A.; Rovolis, A.; Stamou, M. Property Valuation with Artificial Neural Network: The Case of Athens. J. Prop. Res. 2013, 30, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, M.; Mimis, A.; Rovolis, A. House Price Determinants in Athens: A Spatial Econometric Approach. J. Prop. Res. 2017, 34, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balampanidis, D.; Maloutas, T.; Papatzani, E.; Pettas, D. Informal urban regeneration as a way out of the crisis? Airbnb in Athens and its effects on space and society. Urban Res. Pract. 2021, 14, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, P.; Krassanakis, V.; Misthos, L.-M.; Theodoridi, C. A Spatial Regression Model for Predicting Prices of Short-Term Rentals in Athens, Greece. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, P.A. Statistical Methods for Geography, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. Improving your data transformations: Applying the Box-Cox transformation. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.T.; West, S.E. Open Space, Residential Property Values, and Spatial Context. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2006, 36, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Nicolau, J.L. Price determinants of sharing economy based accommodation rental: A study of listings from 33 cities on Airbnb.com. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 62, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, J.; Wong, O.; Wong, A. Data Transformations for Inference with Linear Regression: Clarifications and Recommendations. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2019, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Crespo, R.; Yao, J. Exploring, Modelling and Predicting Spatiotemporal Variations in House Prices. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2015, 54, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, K.; Van Hove, J. Explaining the Spatial Variation in Housing Prices: An Economic Geography Approach. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Castro, E.; Marques, J. Spatial Interactions in Hedonic Pricing Models: The Urban Housing Market of Aveiro, Portugal. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2012, 7, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica-Olmo, J.; Cano-Guervos, R.; Chica-Rivas, M. Estimation of Housing Price Variations Using Spatio-Temporal Data. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, R.J.C.; Han, L.D.; Yang, L. Key Factors Affecting the Price of Airbnb Listings: A Geographically Weighted Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Rey, S.J. Modern Spatial Econometrics in Practice: A Guide to GeoDa, GeoDaSpace and PySAL; GeoDa Press LLC: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Portet, S. A Primer on Model Selection Using the Akaike Information Criterion. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).