Abstract

In this paper, several optimized design results of the HTGR-based 10 MWth Reaktor Daya Eksperimental (RDE) (Experimental Power Reactor), so far conducted, are reviewed and compared from the neutronics, reactor types, refueling schemes, and fuel cycle points of view. The review covers the multipass and once-through-then-out (OTTO) pebble-bed cores, as well as block/prismatic type cores with several fuel shuffling options. As for the fuel cycle, uranium and thorium fuels are considered. The fuel burnup performance and power distribution are evaluated and compared among other important design parameters. Reactor physics codes, nuclear data libraries, and calculation models and procedures used for the design and analysis are reviewed, and challenges for future improvements are discussed.

Keywords:

optimization; neutronics; design; HTGR; pebble-bed; prismatic/block; multipass; OTTO; uranium; thorium 1. Introduction

In 2014, the Indonesian National Nuclear Energy Agency—known then as BATAN and now integrated into the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN)—initiated a project to construct an experimental power reactor, the Reaktor Daya Eksperimental (RDE). This initiative was planned for the Agency’s principal research facility located within the Puspiptek Complex in Serpong, South Tangerang. The RDE was envisioned as a foundational step toward the eventual deployment of commercial-scale nuclear power plants across Indonesia. The primary aim of the RDE project was to validate the safe and dependable production of electricity and thermal energy using nuclear technology. As outlined in the User Requirement Document (URD) [1] issued by BATAN, the proposed reactor design featured a compact pebble-bed high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) with a thermal capacity of 10 MWth. It was to be fueled by low enriched uranium (LEU) in the form of UO2 TRISO particles, operating under either a multipass or once-through-then-out (OTTO) fueling strategy. While Table 1 summarizes the key specifications of the RDE, many of the detailed design parameters—such as core geometry and fuel characteristics—were presented as value ranges. These parameters were intended to be refined progressively through the conceptual, preliminary, and final design stages.

Table 1.

Main design parameters and constraints provided by URD [1].

Several neutronics design efforts based on and beyond the URD requirements were conducted and reported in detail in References [2,3,4,5,6]. The RDE site license was obtained in 2018, but at present (2025) there is unfortunately no clear decision to continue the plan and to build the reactor. Nevertheless, the design efforts and experiences are considered to be a valuable research and development activity, and a milestone for the Agency and the related stakeholders.

In this paper, several RDE design results, so far conducted, are compared and reviewed from neutronics, refueling scheme, and fuel cycle points of view. The calculation models, codes, and libraries used in the design were also briefly discussed. In addition, since the analytical work needed for the above-mentioned design efforts, especially during parametric survey and optimization is enormous, we also proposed and developed a new method to reduce the design work [7].

2. Neutronics Design

Determining the optimal fuel composition is a critical aspect of HTGR operation, as it has direct implications for fuel economics, storage requirements for both fresh and spent fuel, and the overall environmental impact of the fuel cycle. Preliminary investigations were carried out to explore key fuel parameters—specifically, the heavy metal (HM) content per fuel pebble or block and the level of uranium enrichment or fissile content. The primary objective of the studies referenced in [2,3,4,5,6] was to identify suitable ranges for HM loading and enrichment/fissile content levels tailored to the RDE configuration. The HM hereafter is defined as the U-235 and U-238 for uranium fuel cycle, and the Th-232 and U-233 for thorium fuel cycle. The amount of HM per fuel unit significantly influences neutron moderation characteristics, thereby shaping the core’s neutron energy spectrum. Meanwhile, uranium enrichment or fissile content is closely linked to the reactor’s achievable discharge burnup. A central performance metric for evaluating fuel composition is the minimization of fissile material required per unit of energy produced—expressed as the lowest possible kilograms of fissile material per gigawatt-day (GWd) under equilibrium core conditions.

2.1. Design Parameters, Constraints, and Optimization

In the URD shown in Table 1, the main design parameters and constraints of the RDE are listed. The reactor type, thermal output, discharge burnup and the coolant inlet/outlet temperature and pressure are already fixed and treated as the design constraints. As for the core dimension, three design constraints are imposed, that is, the maximum core diameter, minimum height/diameter ratio, and average core power density. On the other hand, as for the fuel composition, only the maximum uranium enrichment (17 wt. %) and maximum HM loading (20 g/pebble) are imposed.

Based on the above-mentioned URD, the RDE design parameters shown in Table 2 and Table 3 were adopted for the pebble-bed [2,3,4] and block/prismatic [5,6] type RDE, respectively. Table 2 [2,3,4] shows the pebble-bed type RDE design parameters adopted for the scoping study. The TRISO detailed specification is provided in [2,3,4]. The core diameter was set to 1.8 m (derived from the Chinese 10 MWth HTR-10 [8]) while the core height/diameter ratio and average power density were set to their minimum values, i.e., 1.1 and 2 W/cm3, respectively, to obtain good neutron economics. Setting the core height/diameter ratio to 1.1 provides the minimal neutron leakage for a cylindrical core geometry while setting the power density to its minimal value (2 W/cm3) yields a larger core dimension, i.e., smaller neutron leakage.

Table 2.

Design parameters of the pebble-bed type RDE [2,3,4].

Table 3.

Design parameters of the block/prismatic type RDE [5,6].

A void space positioned at the top of the pebble-bed reactor core was deemed essential, with its height specified to be around 40 cm [8]. Regarding the initial fuel configuration, a scoping analysis was performed to evaluate uranium enrichment levels between 10 and 20 weight percent, alongside heavy metal (HM) loading values ranging from 4 to 10 g per fuel pebble. Although the design limit for uranium enrichment was set at 17 wt. %, scenarios exceeding this threshold were also examined to ensure comprehensive coverage, given that low enriched uranium (LEU) can reach up to 20 wt. %. Fuel configurations with HM loading below 4 g/pebble or above 10 g/pebble were excluded based on preliminary screening results.

In the case of the thorium-based fuel cycle, no strict upper limit has been formally defined for fissile content. Consequently, a justification was developed to set a reasonable maximum for U-233 concentration. Since U-233 serves as the primary fissile isotope in thorium fuel and exhibits significantly higher reactivity than U-235 in thermal-spectrum reactors, it was proposed that an equivalent upper bound would be approximately 11 wt. %. This figure is based on a comparative assessment with the 20 wt. % enrichment limit typically applied to low enriched uranium (LEU) containing U-235. For the scoping study, we limited the U-233 fissile content up to 12.5 wt. %. Hence, for the fresh fuel composition of thorium fuel cycle, the U-233 fissile content of 5 to 12.5 wt. % and the HM loading of 5 to 25 g/pebble were investigated. Similarly to the uranium fuel cycle, the analysis with the range of HM loading less than 10 or greater than 22 g/pebble were not included via the preliminary calculations (mostly for subcriticality reasons).

The URD permits the RDE to operate using either a multipass or an OTTO (once-through-then-out) fueling strategy. For the multipass configuration, the number of fuel recirculation was set to five, following the precedent established by China’s 10 MWth HTR-10 reactor [8]. In this context, the design assumed a uniform distribution of fissile material without radial zoning.

Due to the absence of finalized specifications for fuel composition, core-reflector geometry, and structural details at the time, several assumptions were made: the fuel was considered free of boron or equivalent neutron-absorbing impurities, and the graphite reflectors were modeled with radial and axial thicknesses of 50 cm and 100 cm, respectively, using a graphite density of 1.75 g/cm3.

In later stages of the RDE development, an option toward a block or prismatic-type reactor design was also proposed. This consideration was driven by the geographical reality that both the RDE site and Indonesia as a whole lie within the seismically active Ring of Fire (Circum-Pacific Belt). The inherent structural stability of prismatic-type HTGRs—where fuel elements are fixed and less prone to displacement during seismic events—makes them particularly suitable for such regions. Additionally, this design facilitates the integration of control and safety rods directly into the reactor core by incorporating dedicated channels within the graphite blocks, thereby ensuring sub-criticality during abnormal conditions.

Table 3 [5,6] outlines the design parameters used in the scoping analysis for the prismatic-type RDE. These specifications and design choices were derived from or adapted based on the URD [1]. Only the uranium fuel cycle was considered.

The specifications for the fuel blocks and TRISO fuel—excluding the TRISO kernel composition—were primarily based on those of Japan’s 10 MWth High Temperature Engineering Test Reactor (HTTR) [9], with several minor adjustments. The HTTR employs two types of fuel blocks: one containing 31 fuel pins and another with 33. For the RDE design, only the 33-pin variant was selected to allow for slightly higher fuel loading per block. Additionally, while the HTTR design does not utilize all available burnable poison (BP) rod positions, necessitating attention to block orientation during loading and refueling, the RDE configuration employs all three BP holes. This standardization—using a consistent number of fuel pins and BP rods per block—is intended to streamline both fuel fabrication and the refueling or shuffling process.

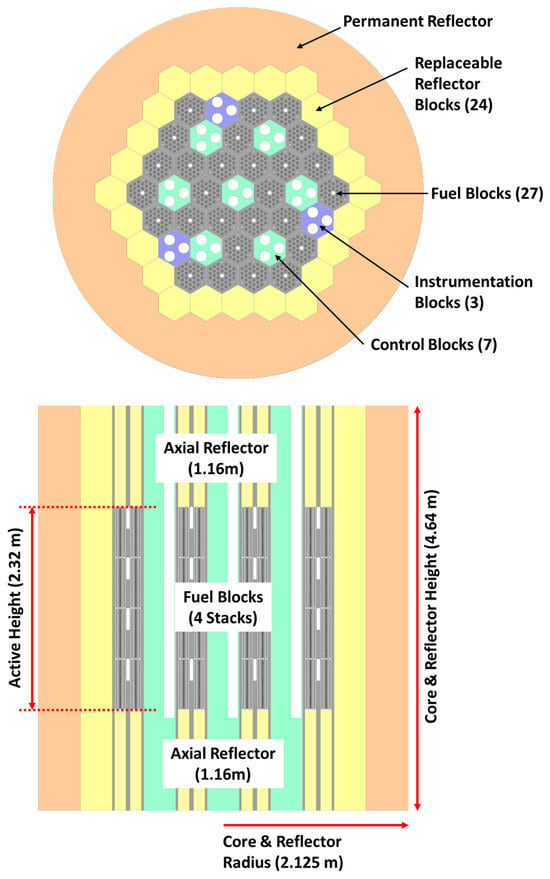

To determine the optimal core geometry, three key parameters from the URD were considered: a core diameter of 2.31 m, a height-to-diameter ratio of 1.0, and an average power density of 1.4 W/cm3. While the core height-to-diameter ratio slightly exceeded the specified value (approaching 1.1), the deviation was deemed acceptable, as it would not significantly impact neutron leakage. It is important to note that the average power density listed in Table 3 pertains solely to the fuel blocks.

Unlike the pebble-bed configuration, the block-type core does not require a void cavity at the top. Instead, this space can be occupied by axial graphite reflector blocks, which effectively reduce axial neutron leakage.

In the original pebble-bed RDE design, constraints included a maximum uranium enrichment of 17 wt. % and a heavy metal (HM) loading limit of 20 g per pebble. For the block-type configuration, the scoping study adhered to the LEU threshold of less than 20 wt. %, but HM loading was defined per fuel block rather than per pebble. This performance metric is influenced by the TRISO particle packing fraction within the fuel compact and the atomic number density ratio of carbon to heavy metal (N_C/N_HM).

Given the lack of detailed specifications for fuel and reflector structures in the block-type RDE, the HTTR design was used as a reference. The radial reflector consists of both movable and permanent graphite blocks, a configuration directly adopted from the HTTR. Similarly, two layers of axial graphite reflector blocks are placed at both the top and bottom of the core, mirroring the HTTR arrangement.

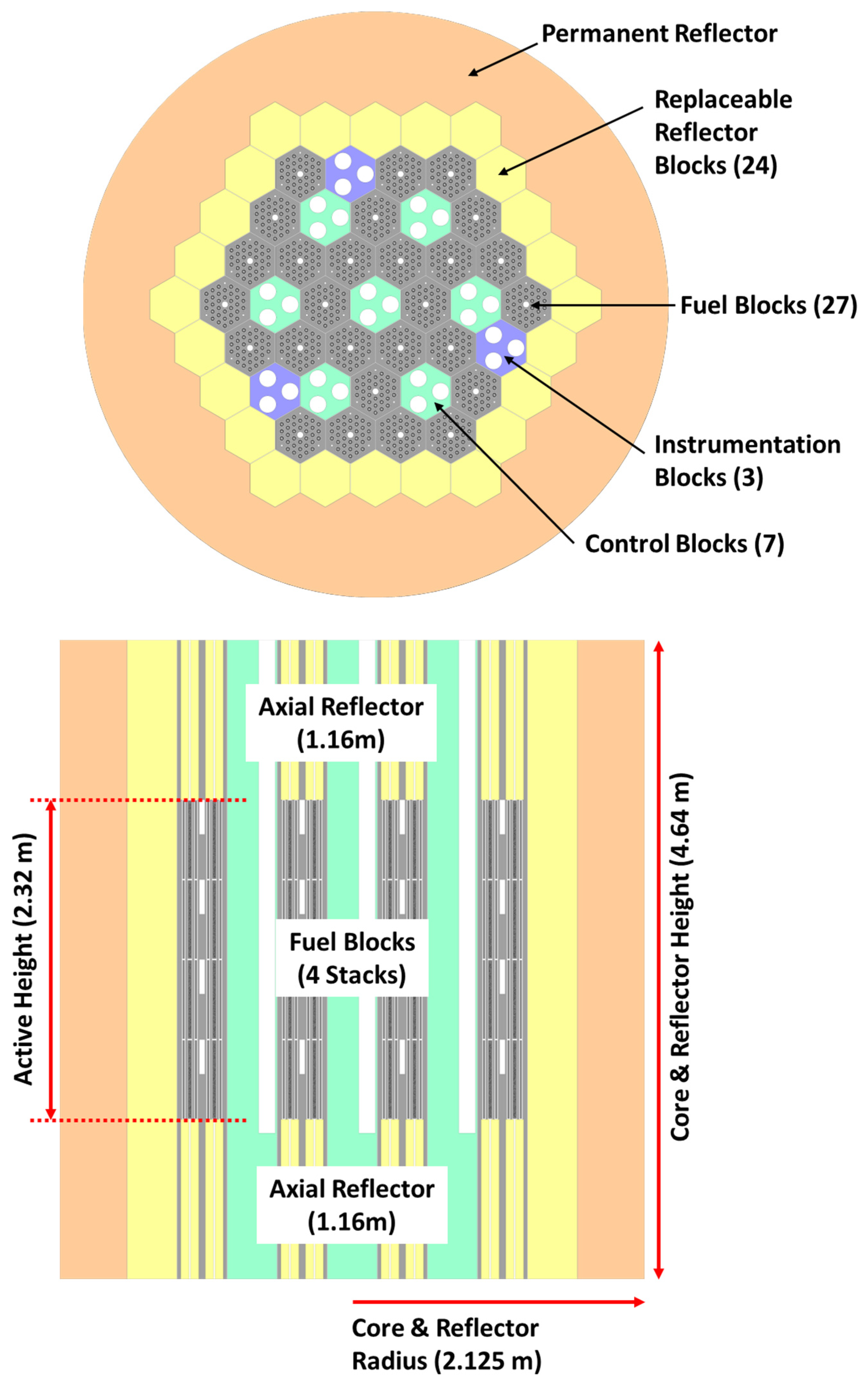

The overall core layout for the block-type RDE was developed with reference to the HTTR but scaled down to match the RDE’s lower thermal output of 10 MWth—one-third that of the HTTR’s 30 MWth. To meet the RDE’s design goal of achieving an average discharge burnup of 80 GWd/t (compared to 33 GWd/t for the HTTR), the core was simplified by reducing the number of columns and the core height. The radial and axial configurations are illustrated in Figure 1. The core comprises 27 columns, each containing four axially stacked fuel blocks, totaling 108 fuel blocks. Seven control blocks are distributed throughout the core, and three instrumentation blocks—identical in size to the control blocks—are positioned along the periphery. Surrounding the fuel region is a ring of replaceable reflector blocks, with two additional reflector blocks placed above and below the fuel stack. The entire assembly is enclosed by a thick layer of permanent reflector material.

Figure 1.

Radial (upper) and axial (lower) core layouts of block/prismatic type RDE. Adapted from ref [6]. Copyright Elsevier.

To enhance discharge burnup in the block-type RDE, several fueling strategies were assessed, including single-batch (as used in the HTTR), 2-batch, and 4-batch schemes. In all cases, fuel shuffling was limited to axial movement within the core.

2.2. Calculation Models and Approximations

For the pebble-bed variant of the RDE, deterministic reactor physics tools were utilized to support the design process. Calculations involving pebble motion, reactor criticality, fuel burnup, and core equilibrium were carried out using an enhanced version of the BATAN-MPASS code [10], specifically adapted for pebble-bed HTGR applications. BATAN-MPASS is an in-core fuel management system built on a multigroup, multidimensional neutron diffusion framework. It includes features for automated equilibrium and criticality searches, as well as integrated thermal-hydraulic modeling capabilities. The code also permits the assignment of varying fissile enrichment/content levels across different radial zones of the pebble flow paths. Details of the thermal-hydraulic modeling approach implemented in BATAN-MPASS were documented by Liem and Sekimoto [11]. To validate the computational framework, benchmark analyses were conducted using the German HTR-Module design (200 MWth), and the outcomes were subsequently compared with results from other reactor simulation codes [12]. The equilibrium search function ensures that all modeled scenarios converge to a core configuration with an effective multiplication factor of 1.0.

Microscopic cross-sections for a four-group neutron energy structure, along with temperature- and composition-dependent self-shielding factors, were generated using the V.S.O.P. code system [13]. For the void cavity located at the top of the reactor core, group constants were derived using the methodology introduced by Gerwin and Scherer [14].

The reactor core was segmented radially into ten distinct flow channels, each characterized by a unique fuel pebble velocity profile. These radial velocity distributions were based on experimental data obtained by KFA Jülich [15], which demonstrated a parabolic trend—maximum flow rates occurring near the core center and gradually decreasing toward the outer regions.

It should be noted that nuclear data library used by the V.S.O.P. code was considerably old (compiled around the 1990s, i.e., ENDF/B-V and JEF-1) and newer nuclear data library may to some extent improve the accuracy of the design analysis results. In addition, the group constants were prepared using only a 4-group structure which might also be improved. Another improvement which may be considered is to replace the neutron diffusion approximation in the BATAN-MPASS code with a higher-order method such as the SN neutron transport approximation. Adopting the neutron transport approximation is expected to improve the criticality and burnup calculation accuracy, particularly for directly treating the upper core void and very small cores with large leakages.

For the prismatic-block configuration of the RDE, reactor physics simulations were conducted using the continuous-energy Monte Carlo code Serpent 2 [16], coupled with the ENDF/B-VIII.0 nuclear data library [17]. A key capability of Serpent 2 is its ability to explicitly model the stochastic spatial distribution of TRISO fuel particles within the fuel compact. To enhance the accuracy of burnup calculations across the full reactor core, fuel blocks were segmented into multiple burnup zones. Similarly, burnable poison (BP) rods were subdivided into five concentric radial layers to enable precise modeling of BP depletion behavior. The simulations also incorporated the thermal scattering law S(α,β) for graphite and applied Doppler Broadening Rejection Correction (DBRC) for U-238 in both lattice-level and core-wide calculations. The Serpent 2 calculation models as well as the ENDF/B-VIII.0 nuclear data library are considered to be state-of-the-art and accurate, but it demands huge computation resources as well as long computation times. Conducting a survey parametric/scoping study using a Monte Carlo code may be prohibitive, and a methodology to reduce the computation burden should be developed such as that which is reported in Reference [7].

3. RDE Optimization Design Results and Discussion

3.1. Pebble-Bed Type RDE Design

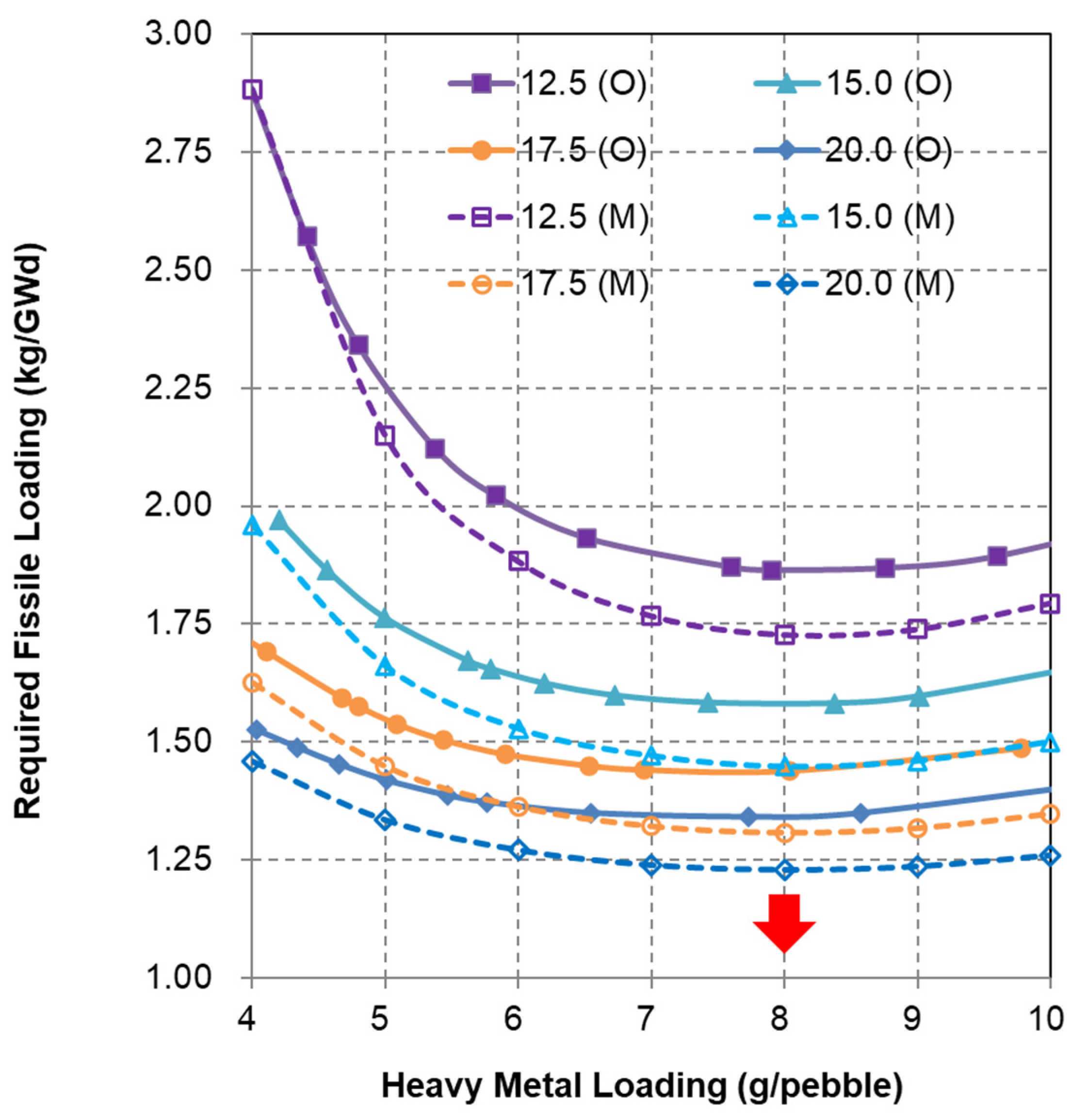

Table 4 presents the optimization outcomes for the pebble-bed RDE configuration, while Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the scoping study results used to determine the most suitable fuel compositions. The analysis begins with a comparison of the two fueling strategies considered for the RDE: once-through-then-out (OTTO) and multipass.

Table 4.

Main optimization design results of the pebble-bed type RDE [2,3,4].

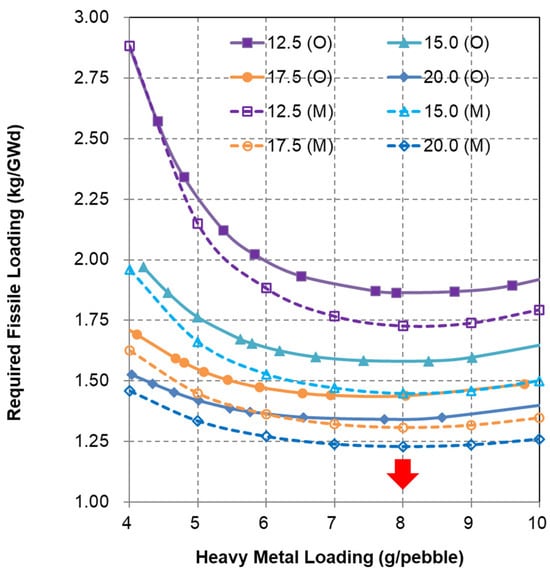

Figure 2.

Fissile loading requirement for uranium fuel cycle (O = OTTO, M = Multipass; Figures of legend show the U-235 enrichment; Red arrow indicates the optimal HM loading).

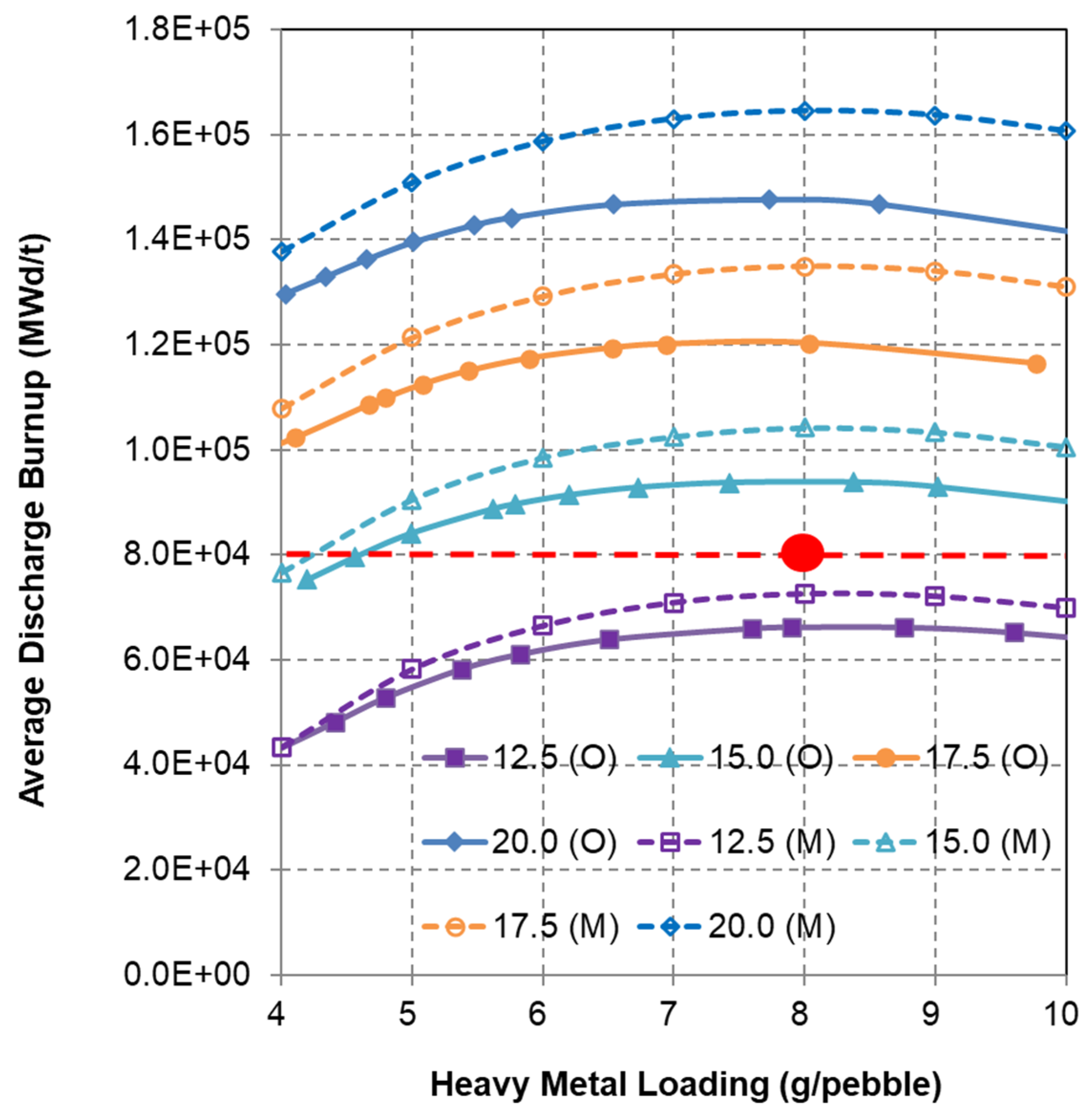

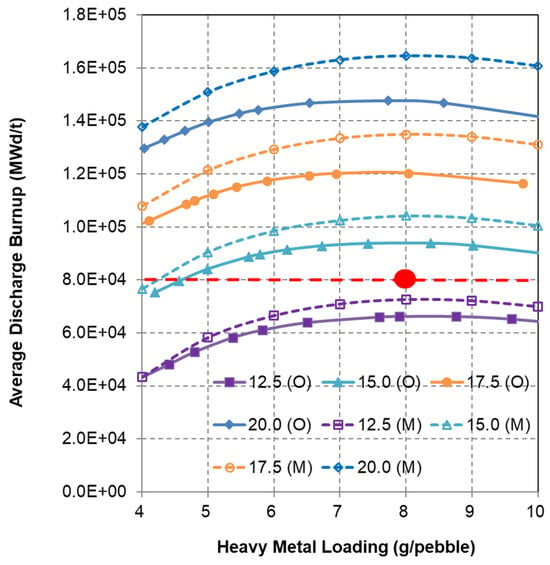

Figure 3.

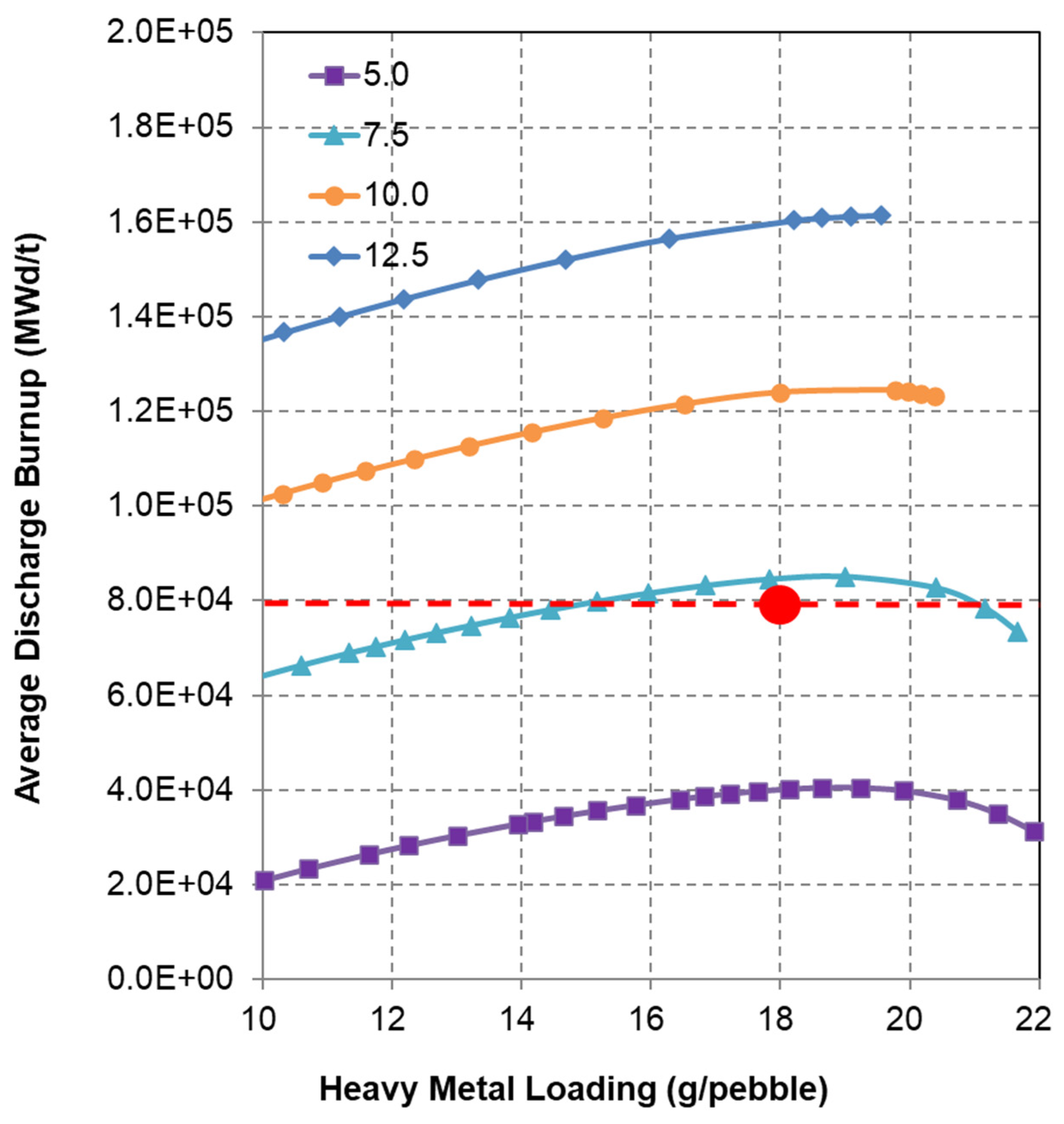

Average discharge burnup for uranium fuel cycle (O = OTTO, M = Multipass; Figures of legend show the U-235 enrichment; Red dot indicates the optimal HM loading).

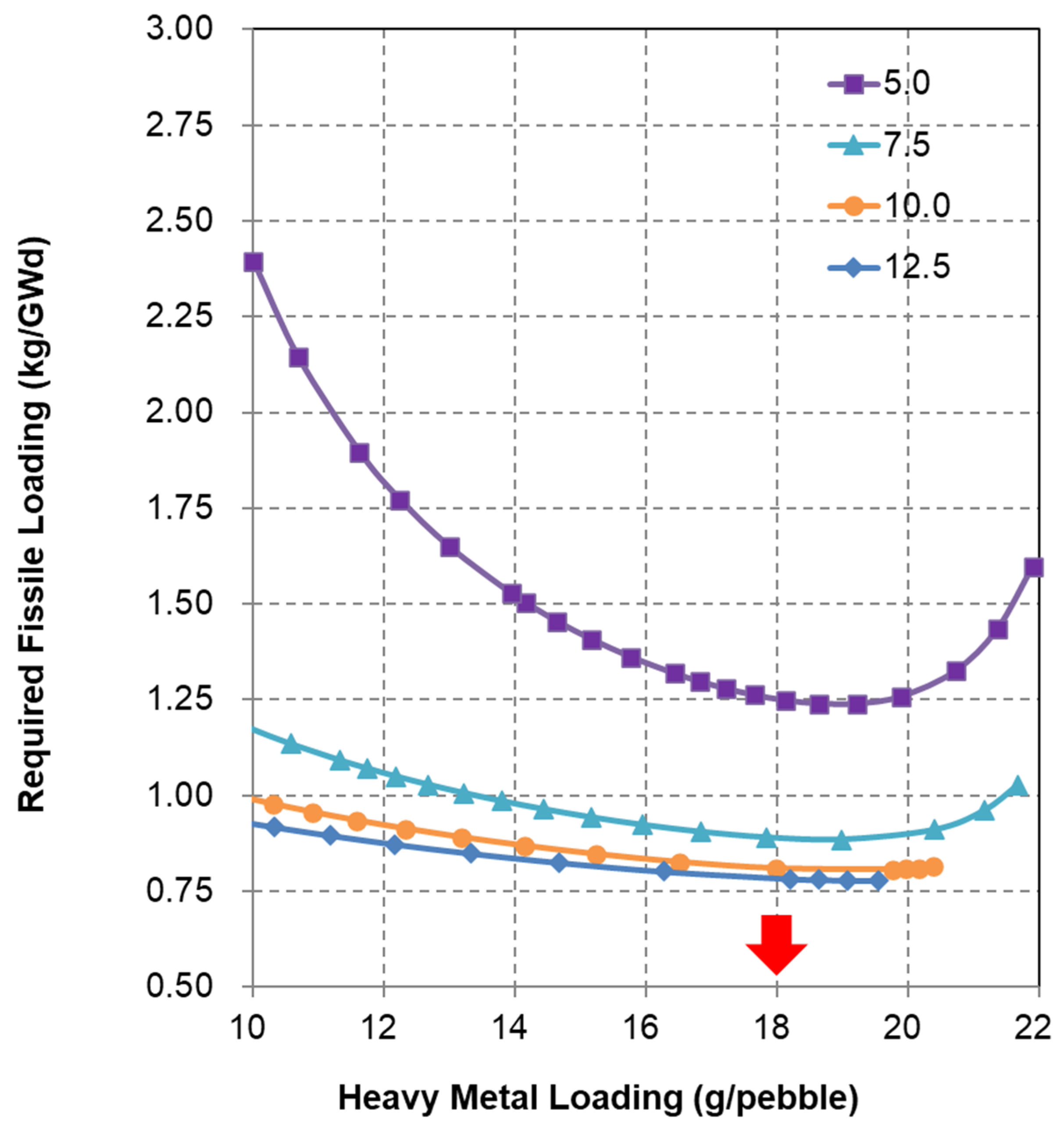

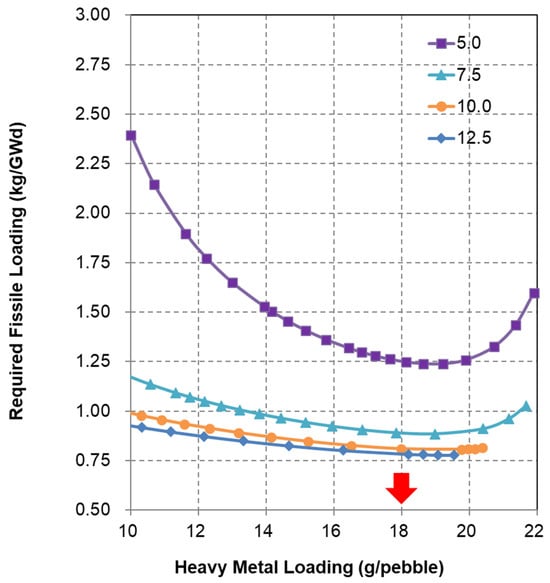

Figure 4.

Fissile loading requirement for thorium fuel cycle (OTTO; Figures of legend show the U-233 fissile content; Red arrow indicates the optimal HM loading).

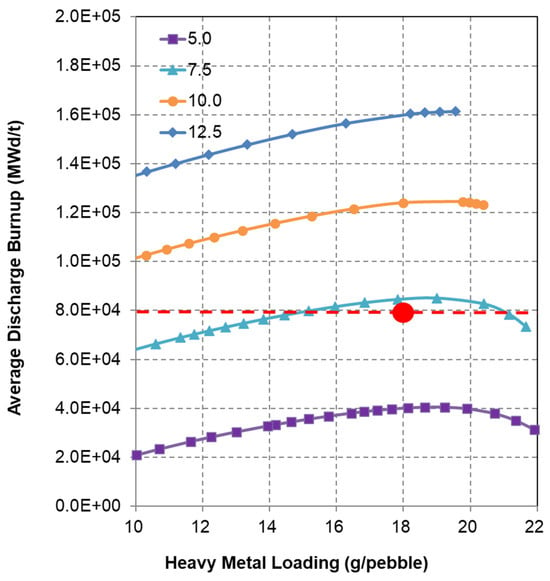

Figure 5.

Average discharge burnup for thorium fuel cycle (OTTO; Figures of legend show the U-233 fissile content; Red dot indicates the optimal HM loading).

Figure 2 and Figure 3 display the evaluation results for both fueling schemes under the uranium fuel cycle. In Figure 2, the relationship between fissile material requirements and heavy metal (HM) loading is shown for four uranium enrichment levels: 12.5, 15, 17.5, and 20 wt. %. Across both fueling approaches, the fissile material needed per unit of energy output decreases as enrichment increases. An optimal HM loading of approximately 8 g per pebble emerges consistently across all enrichment levels and both fueling schemes, as indicated by the red arrow in Figure 2.

Figure 3 illustrates how the average discharge burnup of fuel pebbles varies with HM loading for the same enrichment values. The results suggest a near-linear correlation between enrichment and burnup for both OTTO and multipass configurations.

This trend confirms that an HM loading of 8 g/pebble remains optimal across all uranium enrichment scenarios. Selecting this HM loading alongside a target discharge burnup of 80 GWd/t (highlighted by the red line) yields uranium enrichment values of 13.7 wt. % for OTTO and 13.1 wt. % for multipass (marked by red dots). These combinations correspond to minimum fissile material requirements of 1.73 and 1.66 kg/GWd, respectively, indicating that the multipass scheme offers slightly improved burnup performance and a marginally higher conversion ratio. The estimated residence times for fuel pebbles in the core are 4.6 years for OTTO and 4.7 years for multipass operation. The OTTO fueling strategy tends to yield a more pronounced axial power peak compared to multipass configurations. However, for the optimized fuel composition identified for the OTTO scheme, the peak axial power density remains below 3 W/cm3—well within the acceptable threshold of 0.65 kW per pebble.

Considering the refueling mechanisms needed for multipass and OTTO fuel schemes, it is obvious that compared to the multipass, the OTTO requires a simpler mechanism since one does not need to measure the burnup of the discharged pebbles and to send back the discharged pebbles to the core.

Next, the evaluation on the RDE fuel cycle (uranium vs. thorium) is discussed for the OTTO loading scheme. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the fissile loading requirement and averaged discharged burnup for thorium fuel cycle which are compared with the uranium shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. From Figure 4, the optimum value of the thorium fuel cycle is around 18 g/pebble which is significantly higher than the one of the uranium. This implies that the moderation ratio in the thorium core is lower, i.e., a harder neutron spectrum, and it enhances the conversion ratio in the thorium core.

Figure 5 illustrates how the average discharge burnup of fuel pebbles varies with heavy metal (HM) loading per pebble across four different U-233 fissile content levels. When targeting an average discharge burnup of 80 GWd/t, the optimal fuel configuration for the thorium-based cycle corresponds to an HM loading of 18.2 g per pebble and a U-233 fissile content of 7.2 wt. %, as indicated by the red marker. The optimum composition corresponds to minimal fissile requirement of 0.91 kg/GWd, which shows the superior burnup performance of thorium cycle. However, to start a thorium fueled reactor, enough U-233 fissile material must be prepared, which may not be practical at the present state. Although the average discharge burnup shown in Table 4 is 80 GWd/t, the discharge burnup of individual pebble flow varies from around 60 to 100 GWd/t [4].

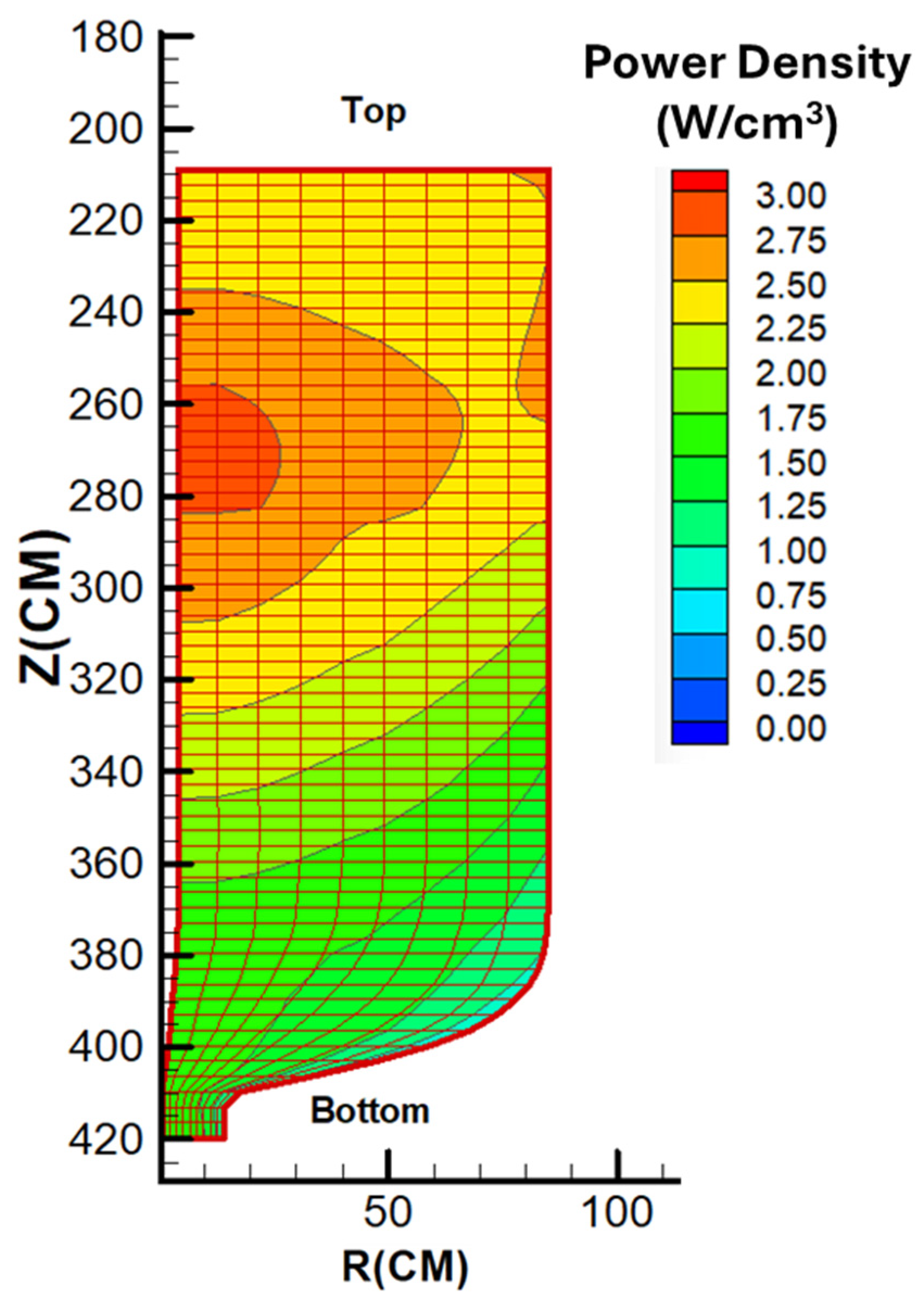

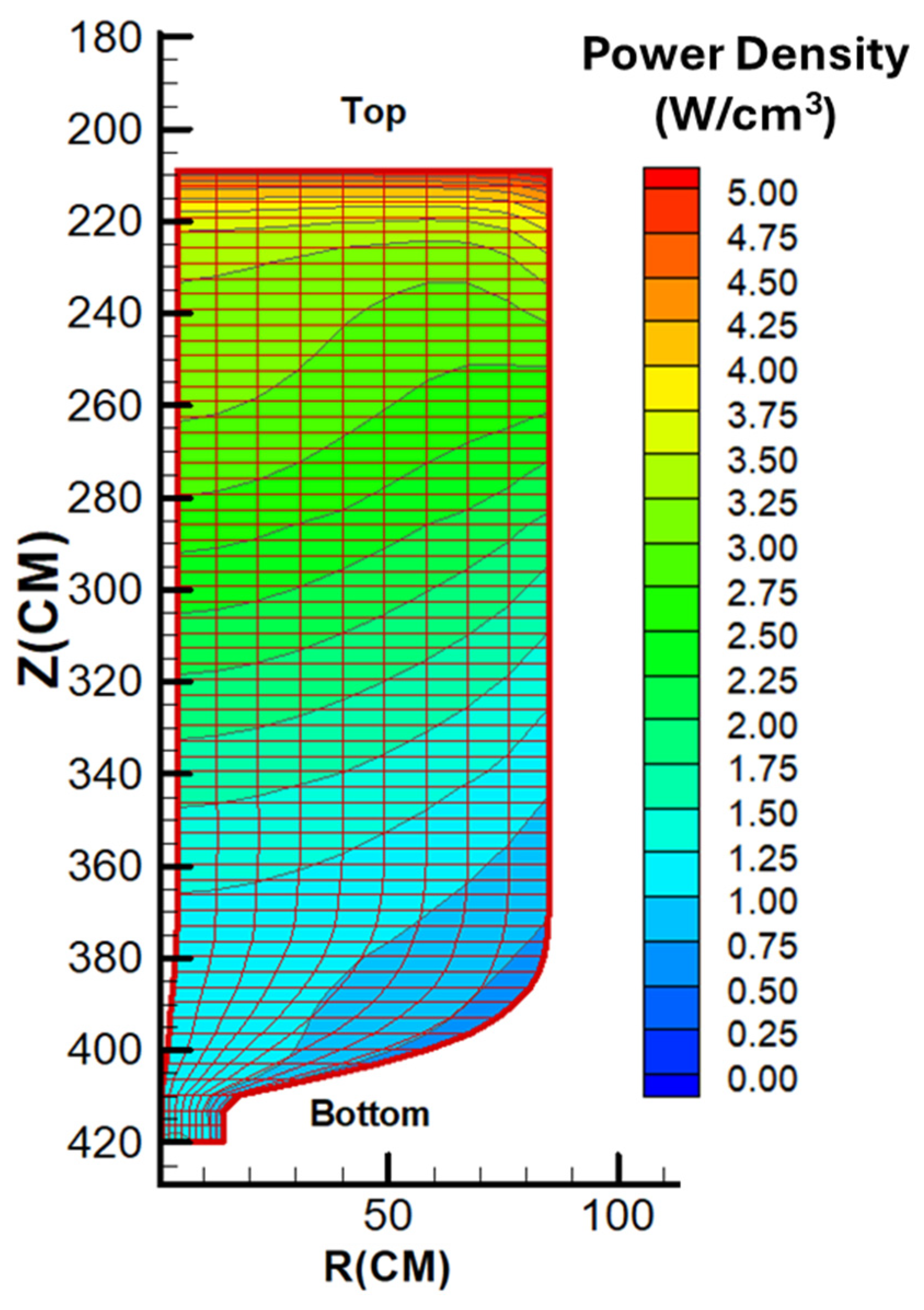

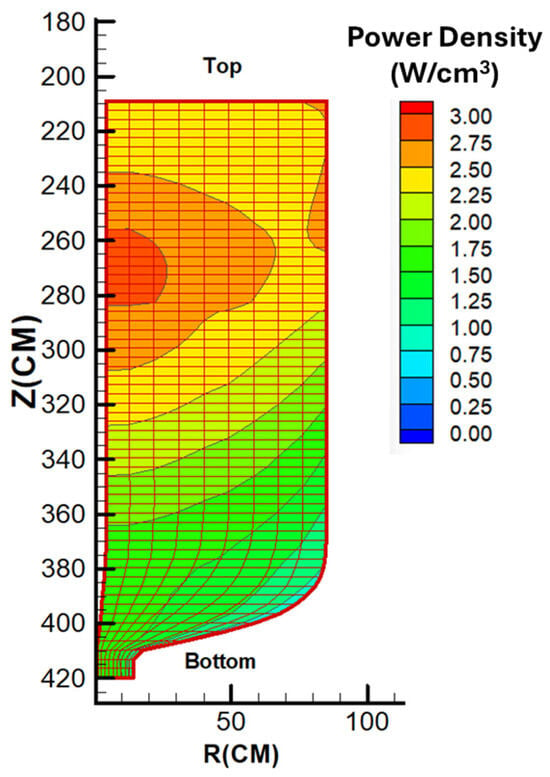

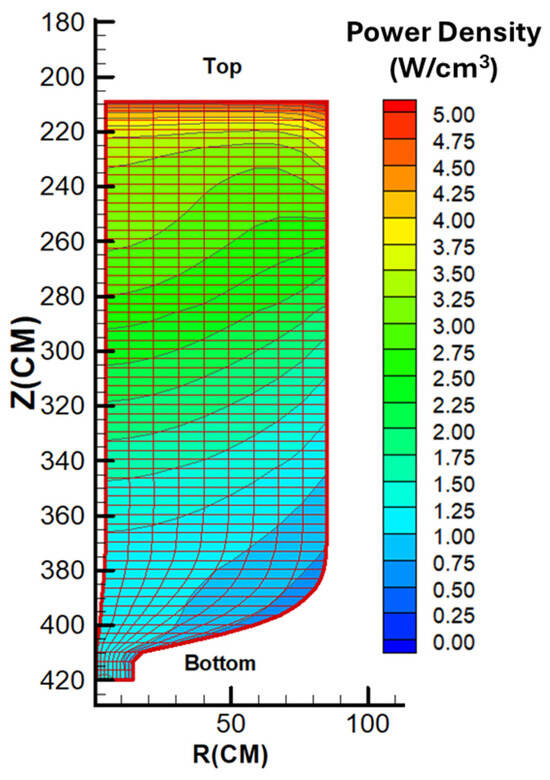

Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the axial power density profiles for the uranium and thorium fuel cycles, respectively. As observed in the figures, the peak power density for the uranium-fueled core is located near the central axial position, approximately at z = 270 cm. In contrast, the thorium-fueled configuration exhibits its power peak closer to the upper region of the core. This upward shift in the power peak for the thorium cycle is primarily attributed to the reduced pebble flow velocity, which results in an extended residence time of the fuel within the core.

Figure 6.

Power density distribution along the pebble flow paths for the optimum fuel composition (uranium fuel cycle, OTTO).

Figure 7.

Power density distribution along the pebble flow paths for the optimum fuel composition (thorium fuel cycle, OTTO).

The above-mentioned RDE’s OTTO uranium fuel cycle with the optimal fuel composition is compared to the Chinese HTR-10 (a 10 MWth pebble-bed reactor). Since the Indonesian RDE is conceptually based on the Chinese HTR-10, their core fuel designs are nearly identical. However, extensive scoping studies have been conducted to optimize the RDE’s fuel composition specifically for Indonesia’s operational goals—namely, a simpler fuel cycle with similar burnup targets. The following key differences and rationales are worth mentioning:

Heavy metal (HM) loading (5 g/pebble vs. 8 g/pebble): HTR-10 uses 5 g of HM per pebble. This is a standard design point for small-scale experimental HTGRs to ensure stable criticality with a multipass system. Optimization studies by Liem et al. [2,3,4] found that increasing the HM loading to 8 g per pebble is more efficient for the Indonesian context. Higher HM loading allows the fuel to reside in the core longer, improving the conversion of fertile isotopes to fissile ones and providing more fuel per volume.

Uranium enrichment (17 wt. % vs. 13.7 wt. %): HTR-10 uses a higher enrichment of 17 wt. %. Because the RDE design targets a higher HM loading (8 g), the results indicate that the enrichment could be lowered to 13.7 wt. % while still achieving the target discharge burnup of 80 GWd/t. This is economically beneficial as it reduces the cost of fuel enrichment.

Fueling scheme (Multipass vs. OTTO): HTR-10 operates on a multipass scheme where pebbles are circulated through the core five times before being discarded. While the RDE can support multipass, the optimization results advocated for the OTTO scheme. This simplifies operations because it removes the need for complex burnup measurement devices and mechanical systems to re-insert pebbles into the core.

3.2. Block/Prismatic Type RDE Design

The detailed results of the lattice optimization for obtaining the optimal fuel composition prior to the whole core calculations can be found in References [5,6]. The whole core calculation results of the block/prismatic design with optimal fuel composition are summarized in Table 5. The results represent the equilibrium core conditions after several reshuffling operations were conducted. For example, for 2-batch core, the equilibrium core conditions are assumed to be achieved after being reshuffled four times, while for 4-batch they were assumed to be achieved after being reshuffled 8 times.

Table 5.

Main optimization design results of the block/prismatic type RDE [5,6].

The initial heavy metal loading, fissile content and packing fractions are uniform across the core, while the fissile loading requirement was calculated from the averaged values of the discharge fuel blocks. The thermal feedback was not considered in the Serpent calculations, instead representative temperatures were adopted for the core and reflector regions. Furthermore, to decrease the Serpent computation time, the critical control rod positions were not searched during burnup calculations. These approximations would affect the axial power distributions to some extent, and would also eventually affect the axial burnup distributions. However, for the present stage of design and comparative study, these approximations are not critical. Hereafter, the 2-batch is selected for further discussion.

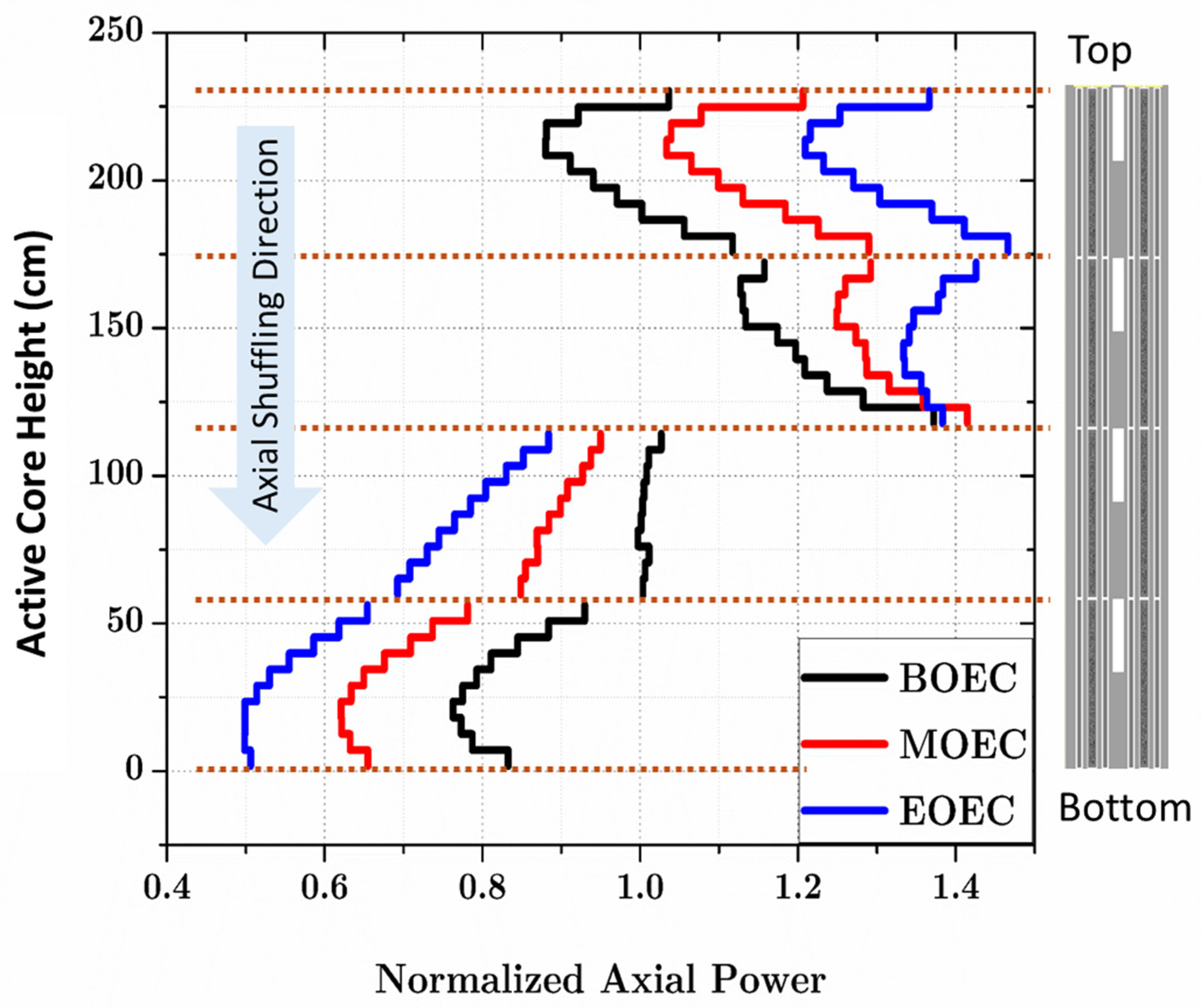

In the 2-batch core configuration, each fuel cycle achieves an average burnup of 40 GWd/t per fuel block. Refueling is conducted axially: two stacks of irradiated fuel blocks are removed from the bottom of the core, while two stacks of partially burned blocks from the top are shifted downward, and two stacks of fresh fuel blocks are inserted at the top. A refueling outage duration of 30 days was assumed for this scenario.

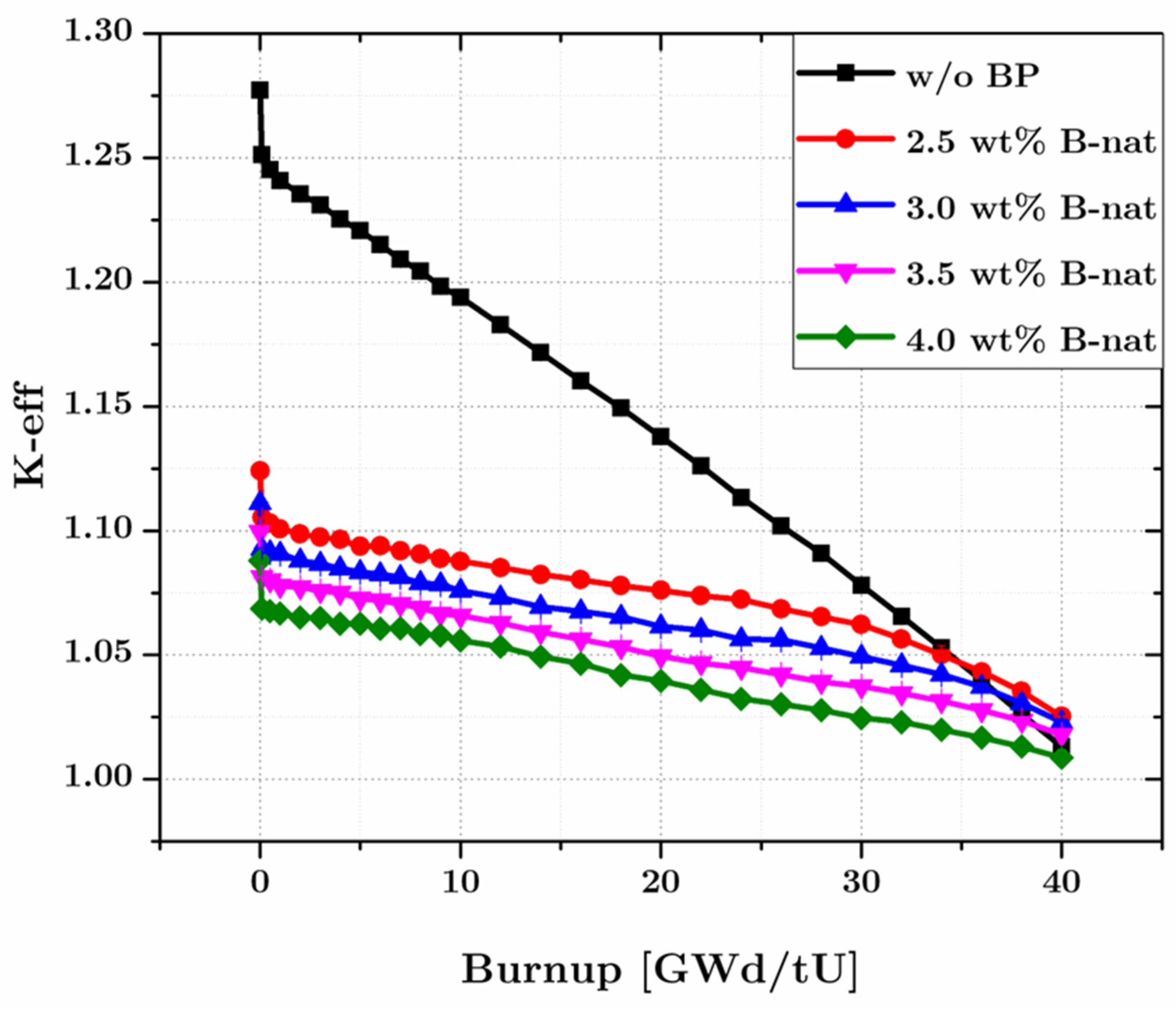

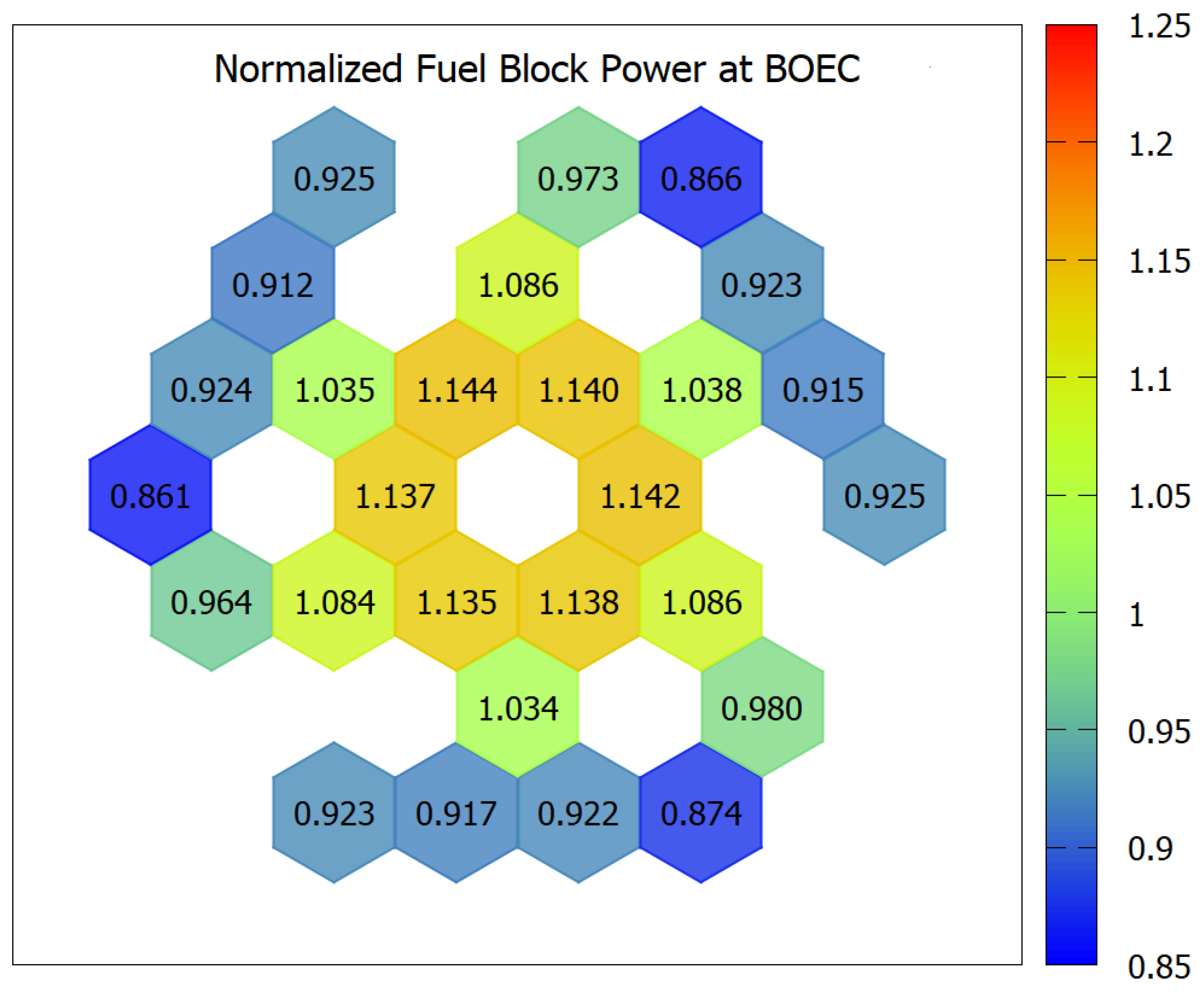

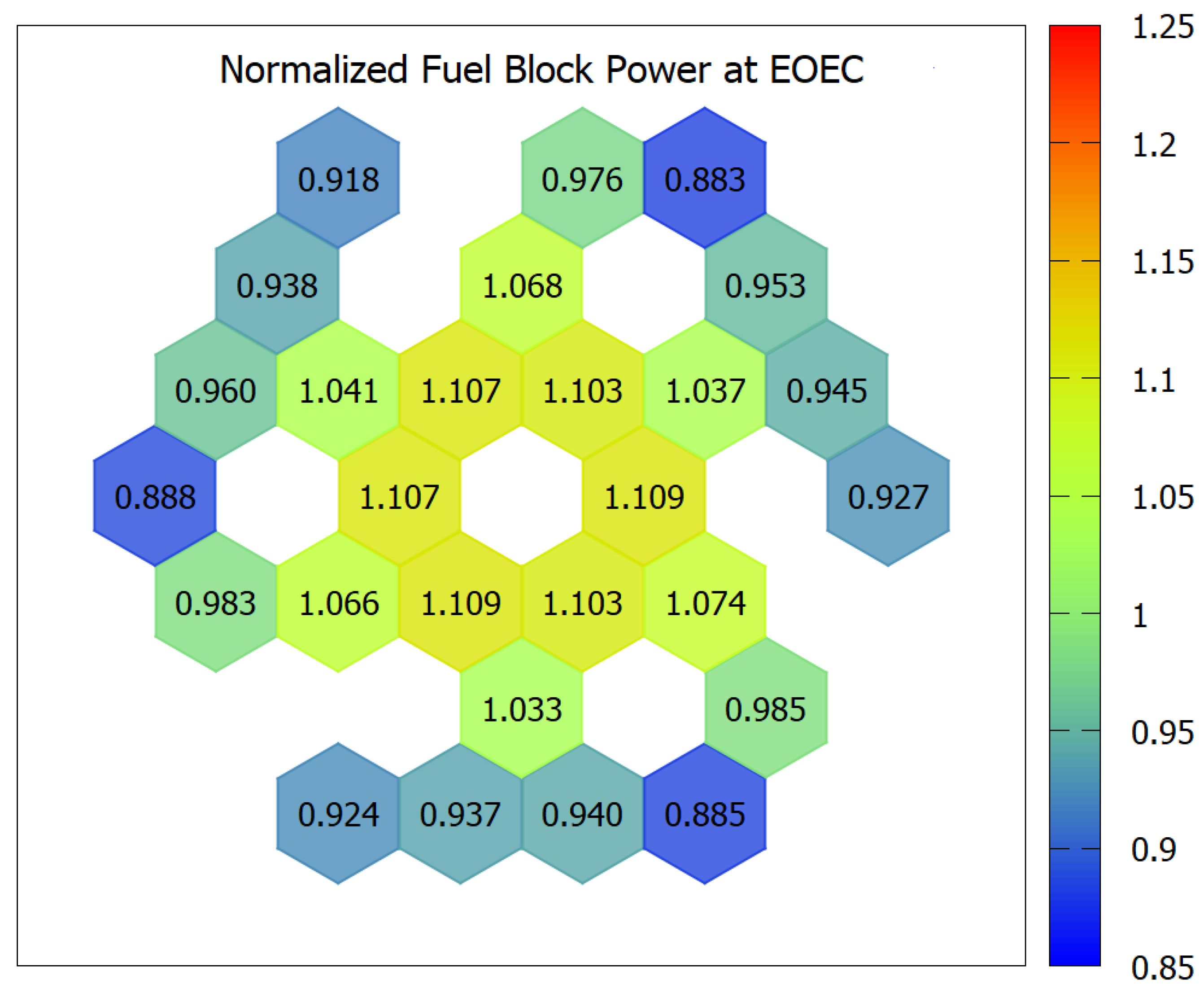

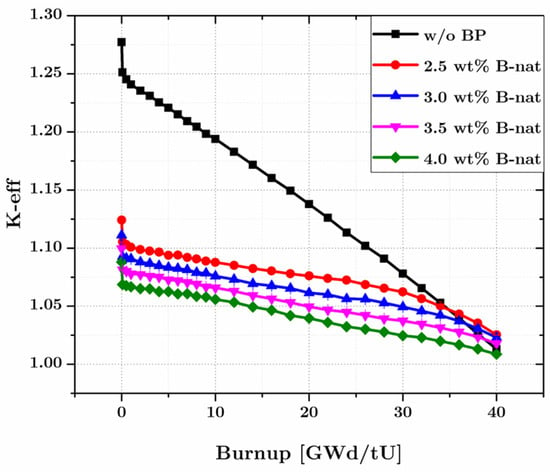

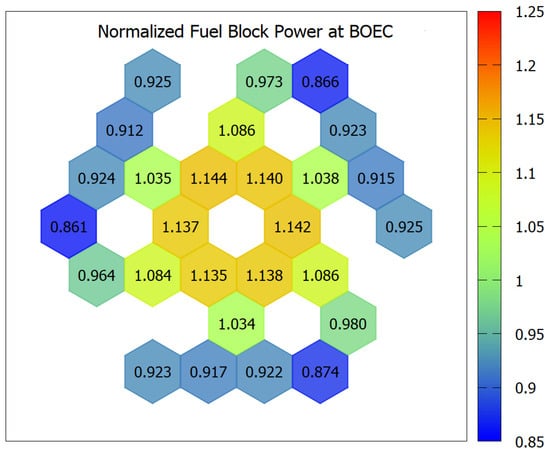

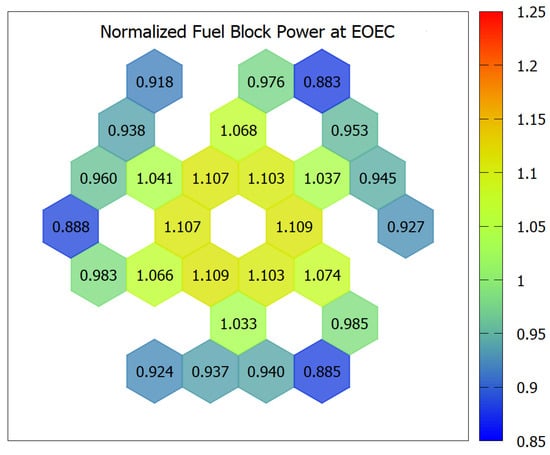

To achieve a target effective multiplication factor (k-eff) of 1.01 at the end of the equilibrium cycle (EOEC), calculations were performed using effective fuel compositions corresponding to various neutron leakage reactivity values (during lattice parametric survey). As shown in Figure 8, this target can be met when the neutron leakage reactivity is approximately 20%. The whole core burnup calculations are then conducted by also considering the BP (B-nat) concentration. Burnable poison (BP) rods were incorporated in the same manner as in the single-batch configuration, effectively suppressing excess reactivity at the beginning of the equilibrium cycle (BOEC). The optimal boron concentration in the BP material was found to be around 3.5 wt. % (The concentration is considered high enough to suppress the initial excess reactivity but low enough so that almost all BP is fully depleted at EOC). Interestingly, the k-eff at EOEC for the configuration with BP rods is slightly higher than that without BP, which is attributed to the moderating effect of graphite formed in the irradiated B4C pins. Additional results for this core design, including radial and axial power distributions at both BOEC and EOEC, are provided in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. Since there is no radial distribution of the enrichment, then the radial power distributions show higher values at the center parts of the core.

Figure 8.

Evolution of k-eff in 2-batch RDE with and without burnable poison.

Figure 9.

Relative radial power distribution of optimum 2-batch RDE with burnable poison (BOEC). Adapted from ref. [6]. Copyright Elsevier.

Figure 10.

Relative radial power distribution of optimum 2-batch RDE with burnable poison (EOEC). Adapted from ref. [6]. Copyright Elsevier.

Figure 11.

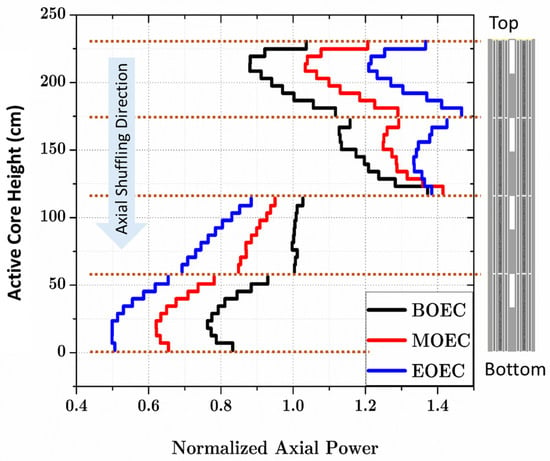

Axial power distribution of optimum 2-batch RDE with burnable poison (dotted lines show the fuel stack boundaries). Adapted from ref. [6]. Copyright Elsevier.

A distinct axial power gradient is observed between the upper and lower regions of the core, which arises from the characteristics of the refueling strategy. At the beginning of the equilibrium cycle (BOEC), fission activity remains evident in the lower portion of the core. However, as the cycle progresses toward its end (EOEC), the upper region exhibits increased fission power due to the depletion of fissile material in the lower region.

One can also observe a significant difference at the boundary between the second and third blocks. This discrepancy is thought to originate from the combination of the burnable poison (BP) depletion effect and the large burnup accumulation in the second blocks prior to axial shuffling. When the first blocks are shuffled downward after one core cycle, their BPs are already depleted; consequently, in the second block positions, the thermal neutron flux and power generation reach their peak. As a result, the burnup addition of the second fuel blocks is also the highest, meaning the third blocks subsequently have large burnup values and lower power production.

Considering the radial and axial peaking factor, the values of RDE with different refueling scenarios are comparable to the values of HTTR. As reported, the HTTR design has maximum radial and axial powers of 1.1 and 1.7, respectively [18].

It is evident that adopting a higher number of fuel batches offers multiple benefits. These include a reduction in the necessary uranium enrichment, a decrease in the amount of fissile material required per unit of energy produced, improved control over excess reactivity, and an extension of the fuel’s residence time within the core. However, increasing the number of fuel batches also shortens the core cycle length as well as requires frequent fuel shuffling and increasing the reactor outage, which should be considered in the final stage of the design.

Compared to the pebble-bed type core with the online refueling capability, the block/prismatic type core suffers from off-line refueling and fuel shuffling work.

The above-mentioned block-type RDE 2-batch uranium fuel cycle was compared to the Japanese HTTR (a 30 MWth, block-type reactor). One can readily observe that the use of a single enrichment, a fixed number of fuel pins per block, and standardized BP arrangement and concentration—as well as a much higher discharge burnup (80 GWd/t vs. 33 GWd/t for the HTTR)—significantly simplify fuel preparation and reduce fuel costs. The RDE’s fuel design is possible since the design does not aim for a very high helium outlet temperature (700 °C vs. 950 °C for the HTTR), and the reactor power is only one-third that of the HTTR. In addition, the core cycle of the RDE is 5 years, which is much longer than that of the HTTR (less than two years, i.e., 660 days). However, since the RDE adopts a 2-batch scheme with axial shuffling, the refueling work needed for each core cycle is estimated to be greater than for the single-batch HTTR.

4. Concluding Remarks and Expectation

Pebble-bed and block/prismatic type 10 MWth RDE with optimal fuel compositions have been reviewed for both uranium and thorium fuel cycles. To start a thorium fueled reactor, a sufficient amount of U-233 fissile material must be prepared which may not be practical at the present state, therefore the uranium fuel cycle should be selected.

For the pebble-bed type RDE, although multipass fueling scheme show a slightly better burnup performance, OTTO fueling scheme is considered a good option if one considers the much simpler mechanism needed for OTTO fueling scheme.

For the block-type RDE configuration, the 2-batch fueling strategy offers the most balanced solution when considering key operational and economic factors. These include minimizing fissile material consumption per unit of energy to reduce fuel costs, maintaining a practical core cycle duration, managing refueling outages, and limiting the frequency of fuel reshuffling. Under this scheme, a core cycle of five years prior to reshuffling and a total fuel residence time of ten years can be achieved while meeting the target discharge burnup of 80 GWd/t.

As stated in the Introduction, at present there is no clear decision to proceed with the RDE plan and build the reactor, although the site license was already obtained. However, in recent years, a larger scale pebble-bed type HTGR design is being pursued by BRIN, i.e., abbreviated as PeLUIt reactor (Pembangkit Listrik dan Uap Panas Industri; Electric Power and Industrial Hot Steam Plant) [19,20]. The BRIN design effort of the PeLUIt reactor is being supported by the Chinese government, via the establishment of the China-Indonesia Joint Laboratory on HTGR. The laboratory staff from the Chinese side are mainly from the Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology (INET), Tsinghua University [21]. It is expected that through this collaboration, the RDE and PeLUIt design coverage and quality would be improved.

Meanwhile in Japan, based on the recent 7th Strategic Energy Plan [22], HTGRs together with fast breeder reactors and advanced light water reactors are again being considered as important key elements in national nuclear energy development. This opens the opportunity to enhance the existing Indonesia (BRIN) and Japan cooperation and collaboration in the HTGR field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The RDE design efforts reported here (References [2,3,4,5,6]) were conducted by the authors and several other persons from several institutions. The author acknowledges their hard work and contributions; special gratitude is addressed to the following persons: (1) Tagor Malem Sembiring of PT ThorCon Power Indonesia (previously worked for BATAN, Indonesia), (2) Hoai-Nam Tran of Phenikaa University, Vietnam (previously worked for Duy Tan University, Vietnam), (3) Bakri Arbie and Iyos Subki of PT MOTAB Technology, Indonesia (previously worked for BATAN, Indonesia). Tables and graphs were prepared carefully by Suzuko Ikegami.

Conflicts of Interest

Peng Hong Liem was employed by Nippon Advanced Information Service (NAIS Co., Inc.).

References

- BATAN. User Requirement Document—Reaktor Daya Eksperimental; BATAN: Tangerang Banten, Indonesia, 2014.

- Liem, P.H.; Sembiring, T.M.; Arbie, B.; Subki, I. Analysis of the Optimum Fuel Composition for the Indonesian Experimental Power Reactor (10 MWth Pebble-bed HTGR). Kerntechnik 2017, 82, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, P.H.; Tran, H.-N.; Sembiring, T.M.; Arbie, B.; Subki, I. Alternative Fueling Scheme for the Indonesian Experimental Power Reactor (10 MWth Pebble-bed HTGR). Energy Procedia 2017, 131, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, P.H.; Sembiring, T.M.; Tran, H.-N. Evaluation on Fuel Cycle and Loading Scheme of the Indonesian Experimental Power Reactor (RDE) Design. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2018, 340, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, P.H.; Hartanto, D.; Tran, H.-N. Lattice Physics Study of a Block/Prismatic-Type HTGR Design Option for the Indonesian Experimental Power Reactor (RDE). In Proceedings of the HTR-2021, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2–4 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hartanto, D.; Liem, P.H. Physics Study of Block/Prismatic-type HTGR Design Option for the Indonesian Experimental Power Reactor (RDE). Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 368, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, D.; Liem, P.H. Neutron Importance-Based Lattice-to-Core Projection Technique and its Application for HTGR Design Using Monte Carlo Method. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 381, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zuo, K. Overview of the 10 MW High Temperature Gas Cooled Reactor—Test Module Project. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2002, 218, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bess, D.; Fujimoto, N. Evaluation of the Start-up Core Physics Tests at Japan’s High Temperature Engineering Test Reactor (Fully-loaded Core), HTTR-GCRRESR-001, Rev. 1. In International Handbook of Evaluated Reactor Physics Benchmark Experiments; NEA/NSC/DOC (2006)1; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development/Nuclear Energy Agency: Boulogne-Billancourt, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, P.H. BATAN-MPASS: A General Fuel Management Code for Pebble-Bed High-Temperature Reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 1994, 21, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, P.H.; Sekimoto, H. Neutronic and Thermal Hydraulic Design of the Graphite Moderated Helium-Cooled High Flux Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1993, 139, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, W.; Gougar, H.; Ougouag, A. Direct Deterministic Method for Neutronics Analysis and Computation of Asymptotic Burnup Distribution in a Recirculating Pebble-Bed Reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2002, 29, 1345–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuchert, E.; Haas, K.A.; Rütten, H.J.; Brockmann, H.; Gerwin, H.; Ohlig, U.; Scherer, W. V.S.O.P. (’94)—Computer Code System for Reactor Physics and Fuel Cycle Simulation; Jul-2897; International Nuclear Information System: Vienna, Austria, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gerwin, H.; Scherer, W. Treatment of the Upper Cavity in a Pebble-Bed High Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor by Diffusion Theory. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 1987, 97, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuchert, E.; et al. Private Communication, 1987.

- Leppänen, J.; Pusa, M.; Viitanen, T.; Valtavirta, V.; Kaltiaisenaho, T. The Serpent Monte Carlo Code: Status, Development and Applications in 2013. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2015, 82, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Chadwick, M.; Capote, R.; Kahler, A.; Trkov, A.; Herman, M.; Sonzogni, A.; Danon, Y.; Carlson, A.; Dunn, M.; et al. ENDF/B-VIII.0: The 8th Major Release of the Nuclear Reaction Data Library with CIELO-project Cross Sections, New Standards and Thermal Scattering Data. Nucl. Data Sheets 2018, 148, 1–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Tanaka, T.; Sudo, Y. Design of High Temperature Engineering Test Reactor (HTTR); JAERI 1332; Japan Atomic Energy Research Inst.: Tokyo, Japan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trianti, N.; Widiawati, N.; Wulandari, C.; Miftasani, F.; Rohanda, A.; Khakim, A.; Setiadipura, T. Optimum Power Determination and Comparison of Multi-pass and OTTO Fuel Management Schemes of HTGR-based PeLUIt Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2023, 415, 112696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, R.F.S.; Ariyanto, S.; Salimy, D.H.; Nurmayady, D.; Amitayani, E.S.; Nuryanti; Anzhar, K.; Nurulhuda, E.; Nurlaila. Scaling Law Method for Cost Estimation of Indonesia’s First HTGR (PeLUIt-40) and its Implementation Strategy. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 423, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Sui, Z.; Yan, H.; Qi, W.; Ren, X.; Sun, Y.; Setiadipura, T.; Bakhri, S.; et al. Progress of Establishing the China-Indonesia Joint Laboratory on HTGR. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 397, 111959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economic, Trade and Industry. Strategic Energy Plan. Available online: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan (accessed on 26 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.