Abstract

In recent years, the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults (ages 10–24) in Africa has improved through national and international initiatives. However, major challenges remain in enabling young people to exercise their sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHRs), especially in Côte d’Ivoire. This study aimed to explore the perspectives of stakeholders on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults with regard to SRHRs in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire. We conducted this qualitative descriptive study between September and October 2023. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method. Overall, 137 stakeholders participated in the study: 57 teachers and administrators, 17 community leaders, and 63 parents. Data were collected through interviews and focus groups, using an interview guide. Through a deductive thematic approach, we identified three forms of freedom of choice: conditional, absent, and absolute. The average age of the study participants was 46.1 years. The findings reveal that several factors influence the freedom of choice among adolescents and young adults regarding their SRHRs. These include age, gender, parental involvement, prior education, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Limited freedom was commonly associated with younger age (10–18 years), perceived immaturity, and a lack of autonomy. In contrast, greater freedom was linked to older age (18–24 years) and higher levels of perceived maturity. Stakeholders’ perspectives were shaped by cultural and religious norms, a protective attitude toward youth, and a sense of disengagement from adolescent concerns. This study underscores the importance of interventions aimed at increasing stakeholders’ knowledge and awareness of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights.

1. Introduction

Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity [1]. To achieve and preserve sexual health, every person’s sexual rights must be respected, upheld, and fulfilled [2]. Sexual and reproductive rights include the right and freedom of every individual to control their own sexual and reproductive life. Thus, adolescents (10–19) and young adults (15–24) should have the right to access sexual and reproductive health services and to make autonomous decisions about their sexual and reproductive lives. This freedom is particularly important for this population, as adolescence and early adulthood are critical periods for identity formation, risk exposure, and long-term health outcomes [3]. In many African contexts, adolescents and young adults live within nuclear or extended family structures, where intergenerational cohabitation is socially valued and autonomy is acquired gradually through evolving social roles rather than fixed legal age thresholds [4,5].

According to the WHO, ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHRs) during adolescence helps prevent early pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and harmful practices such as child marriage, while promoting bodily autonomy and informed decision-making [6]. Recent studies further highlight that adolescents, when provided with age-appropriate information and supportive environments, demonstrate an evolving capacity to make informed decisions regarding their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) [6,7,8,9]. Safeguarding their SRH freedom is therefore essential to enhancing their overall well-being and empowering them to exercise autonomy in health-related choices.

Recognizing adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights (ASRHRs), the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development urged countries to address the educational and service requirements of adolescents to allow them to manage their sexuality in a healthy and responsible manner [10]. According to Liang et al. (2019), ASRHRs have advanced significantly in the 25 years since the 1994 conference [11]. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals have also motivated international efforts to enhance the SRHRs of adolescents and young adults [12]. For example, compared to 25 years ago, adolescents are more likely to delay their first sexual experience and to use contraceptives [11]. These improvements in adolescent sexual and reproductive health are particularly evident in Southern and Eastern Africa, where increased access to comprehensive sexuality education and youth-friendly services has contributed to higher contraceptive use and more informed decision-making [13].

While notable progress has been made in ASRHRs in recent years, significant challenges persist, and progress remains uneven across regions. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where higher rates of sexual activity among young adolescents are recorded compared to other regions of the world [11], adolescents continue to face significant barriers that prevent them from fully accessing and exercising their SRHRs. Key challenges include limited access to contraception, poor menstrual health management, insufficient sexual education, high rates of early pregnancy, and restrictive cultural and religious norms that shape attitudes toward adolescent sexuality [12,14]. Millions of girls are dropping out of school as a result of teenage pregnancies [15]. Rural areas are disproportionately affected, with about 30% of girls becoming pregnant before the age of 19 [15]. As Nowshin et al. (2022) highlight, “last mile” adolescents living in remote, underserved, or marginalized communities continue to face significant barriers to SRHR, including limited access to services and information [12]. In Côte d’Ivoire, the number of school pregnancies is high. The National Council for Human Rights recorded over 4000 school pregnancies in 2023–2024, a 15.3% increase from the previous year [16,17], with Haut-Sassandra among the most affected regions [18]. Adolescents face growing risks related to sexually transmitted infections [19], with 2.5% of school health consultations in 2019 attributed to STIs among youth [20]. Sexual violence and limited understanding of consent are also common [19,21]. In certain regions, sociocultural practices such as early marriage, rigid gender roles, levirate, sororate, and persistent taboos surrounding sexuality can be observed and may significantly influence adolescents’ access to SRHRs [22]. These issues are compounded by sociocultural norms and gaps in stakeholder engagement, which hinder access to comprehensive SRHRs services [21,23].

In many contexts, adolescents have limited capacity to exercise their rights with respect to SRH. They also face many unmet needs [24,25,26]. The concept of freedom of choice in sexual and reproductive health remains controversial, particularly in developing countries, where it causes tensions between social, religious, and political actors. Moreover, the realization of these rights remains deeply influenced by social norms, gender dynamics, policy ambiguities, and institutional practices that often limit young people’s decision-making capacity [27,28,29,30]. Despite these challenges, national policies in Côte d’Ivoire affirm a commitment to ensuring adolescents and young adults have free, informed, and responsible access to SRH services [22]. Understanding and supporting these rights is especially crucial for those who influence adolescent development. Supporting these rights is especially critical for those who influence adolescent development. Yet, to date, no study has explored how adolescents and young adults in Haut-Sassandra navigate SRHRs-related decisions. Similarly, little is known about the perspectives of key adult stakeholders, i.e., parents, teachers, religious leaders, and policymakers, who play a central role in shaping access to information, services, and decision-making. These actors influence knowledge dissemination, attitudes toward healthy practices, and resource availability through their authority and social roles. Evidence shows that stakeholder engagement enhances service acceptance and effectiveness, highlighting the need for inclusive, community-based approaches [14,31].

Given the importance of combining adolescent-focused interventions with initiatives to foster acceptance among adult stakeholders [32], this study aimed to explore the perspectives of stakeholders on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire, concerning SRHRs. This study is part of the Projet d’Appui à des Services de Santé Adaptés au Genre et Équitables (PASSAGE) in the Haut-Sassandra region of Côte d’Ivoire. The PASSAGE Project is a multi-sectoral initiative that adopts a comprehensive approach to health promotion. It is implemented by a consortium of Ivorian and Canadian partners. Among other objectives, it aims to promote greater realization and enjoyment of SRH rights among adolescents and young adults in the Haut-Sassandra region of Côte d’Ivoire through targeted interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study used a qualitative descriptive research design to gain a better understanding of the perspectives of stakeholders regarding adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice in matters of SRHRs in the Haut-Sassandra region, Côte d’Ivoire. This approach allowed us to explore participants’ views in their own words and present their perspectives as they were expressed without imposing theoretical interpretation. Qualitative description is particularly suited for capturing stakeholder perceptions in culturally specific settings, making it appropriate for this study [33].

Data were collected in the Haut-Sassandra region, more specifically in Daloa, Gonaté, and Bonoufla. Daloa is the most important town of the Haut-Sassandra region, situated in the center-west of Côte d’Ivoire. Daloa is located 408 km from Abidjan, the country’s economic capital [34]. In 2021, the population of the city of Daloa was estimated at 705,378, with a population density of 184.7/km2 [35]. Gonaté and Bonoufla are located 24 km and 29 km from Daloa, respectively.

2.2. Study Population

Participants were stakeholders from civil society. Here, we refer to actors who play a role or exert an influence in the field of SRHRs in general, or more specifically among adolescents and young adults, as stakeholders. They were grouped into three categories: (1) school and university teachers and administrators; (2) community leaders; and (3) parents.

For the purposes of this study, we adopt the United Nations definition of adolescence and young adults. The United Nations considers adolescents to be individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 and young adults to be individuals between the ages of 15 and 24. Adolescents and young adults are collectively referred to as “youth”, which includes the age range of 10 to 24 [36,37].

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, teachers must regularly teach in an educational institution. To ensure that they are actually in contact with schoolchildren in the age group of interest, only primary school teachers who teach 4th grade and upwards were included in the study. Community leaders must be acknowledged members of the community who use their influence to provide guidance on societal issues. Their leadership must be recognized by community members. They can be political, religious, or cultural leaders. Parents must have at least one teenage or young child. All stakeholders must agree to participate in the study.

2.4. Recruitment

Participants in this study were selected using a purposive sampling method with convenience and snowball techniques [38]. This combination was chosen to ensure good representation of the different stakeholder categories and to facilitate access to participants who were either difficult to identify or more readily available in community settings. As consideration was given to the representation of men and women, as well as to that of inhabitants of different residential areas (urban, rural, semi-urban), we planned to recruit at least 63 teachers, 60 parents, and 20 community leaders until data saturation was reached. The lower number of community leaders ultimately included reflects both their proportionally smaller presence in the intervention areas and their limited availability during the data collection period.

To recruit teachers, we contacted the administration of the target institutions, who in turn relayed the information and invited their members to take part in the study. Teachers who were interested and available on the planned data collection dates participated in the study.

Parents were recruited by the interviewers, who were divided amongst the three data collection localities. They aimed to recruit and interview parents (fathers and mothers) who met the selection criteria. After each interview, they asked the participating parent to suggest other potentially interested parents.

Community leaders were also recruited by the interviewers, based on the detailed mapping of community leaders including traditional leaders, village chiefs and their council of elders, youth leaders (particularly presidents of youth groups and associations). Carried out between April and July 2023, this mapping was conducted in the areas covered by the PASSAGE project, and aimed to identify individuals capable of influencing attitudes, practices, and knowledge related to SRHRs. Interviewers contacted leaders within their assigned zones, relying on this mapping to ensure representation across diverse communities and recruited those who were available and willing to participate in the study.

2.5. Data Collection

The interviewers were community workers with experience in data collection who also attended an information session on the study objectives and data collection procedures.

Data were collected through individual semi-structured face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions using an interview guide. The interview guide was co-constructed by the Canadian and Ivorian partners. The Canadian partners were Fédération des cégeps, Laval University, and the Réseau francophone international pour la promotion de la santé. The Ivorian partners were Association Ivoirienne pour le Bien-être Familial, Association Ivoirienne des Professionnels de la Santé Publique, Institut National de Formation des Agents de Santé, Mission des jeunes pour la Santé, la Solidarité et l’Inclusion, Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale et de l’Alphabétisation, Ministère de la Santé de l’Hygiène Publique et de la Couverture Maladie Universelle, and the Association des infirmiers et infirmières de la Côte d’Ivoire.

The development of the interview guide was informed by a review of the relevant literature, internal consultations among the research partners, and alignment with the conceptual framework for sexual ethics of equal rights and responsibilities [39] to formulate semi-structured interview guide questions. The guide was jointly reviewed by field investigators and research partners. It was then pretested with interviewers prior to data collection to ensure cultural relevance, clarity, and contextual appropriateness. This process allowed for refinement of the semi-structured questions, which focused on stakeholders’ perceptions of adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice regarding SRHRs, both in general and in relation to specific topics such as choosing abstinence, choosing to have sex, choosing a partner, and deciding for oneself to go to a health center.

Individual interview locations were selected according to participants’ preferences. Focus group discussions were conducted at teachers’ workplaces, i.e., in schools and one university. At the beginning of the interview, the interviewer introduced themselves and provided some background information on the project and its objectives. The interviewer then presented the consent form to the participant. After the participant had read (or heard) and signed the consent form, the interviewer collected some socio-demographic information (location; urban, semi-urban, or rural environment; biological sex; title/function; and age) before administering the questions from the interview guide. Interviews lasted approximately 20 to 25 min.

All interviews were conducted in French. Interviews were recorded using an audio recorder following written consent from the participants. All participants consented to the audio recording of the interviews. Recruitment and data collection took place between 1 September and 31 October 2023.

2.6. Data Analysis

Of the interviewers who collected the data, six were chosen to transcribe the interview audios. To take part in data transcription, interviewers had to be experienced and have access to a computer. The transcribers attended a capacity-building session given by a research team member (M.M.N.). Transcriptions were made after the data collection phase. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction.

We carried out a deductive thematic analysis following the six steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) familiarizing oneself with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes and checking their effectiveness; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) writing reports [40]. Data analysis was conducted by four research team members (M.M.N., L.G.K., and T.T.A. under the supervision of M.J.D.) including an Ivorian analyst with the necessary expertise in local terminologies. The analysis was carried out in tables using Word and Excel. Each analyst reviewed one full transcript for each stakeholder category to familiarize themselves with the data. They then proceeded individually to analyze the verbatim responses by stakeholder category. The team met several times to (1) resolve issues of text comprehension related to the local terminologies used by study participants; (2) discuss differences in analysis; (3) pool results by identified theme; and (4) interpret the data. Conflicts were resolved by M.J.D.

To ensure rigor and trustworthiness, we triangulated perspectives across stakeholder categories and the varied disciplinary and cultural profiles of the analysts. This triangulation allowed us to identify both convergences and divergences in stakeholder views, highlighting shared concerns as well as group-specific nuances regarding adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice in SRHR. Researcher reflexivity was maintained throughout the process. Although member checking was not conducted, the collaborative and iterative nature of the analysis contributed to the credibility of the findings.

The results of the analysis are presented by theme. For each theme, we include a specific quote from a participant to support the idea. The quotes have been translated from French into English for publication purposes.

We reported data using verbal counting such as few, some, many, and most [41]. We define “few” as occurring in less than 20% of participants, “some” as occurring between 30 and 50%, “many” as occurring between 50 and 70%, and “most” as occurring for more than 70% of participants. This applies to all participants or to each category of participants.

We reported this study using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups [42].

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The project was approved by the Comité National d’Éthique des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé in Côte d’Ivoire (N/Réf: 114–23/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km) and by the Research Ethics Committee of the CHU de Québec-Université Laval in Canada (Project 2024–7017).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Overall, 137 stakeholders participated in the study: 57 teachers, 17 community leaders, and 63 parents. Five focus group discussions were conducted with 37 school and university teachers and administrators. There were six to nine participants per focus group. One focus group was conducted with five community leaders.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

The overall mean age was 46.1. For stakeholders who participated in individual interviews, the mean age was 41.6 for teachers and administrators, 55.6 for community leaders, and 41.2 years for parents. A third of the stakeholders resided in an urban area (Daloa), another third came from a semi-urban area (Bonoufla), and the rest came from a rural area (Gonaté).

3.2. Main Results

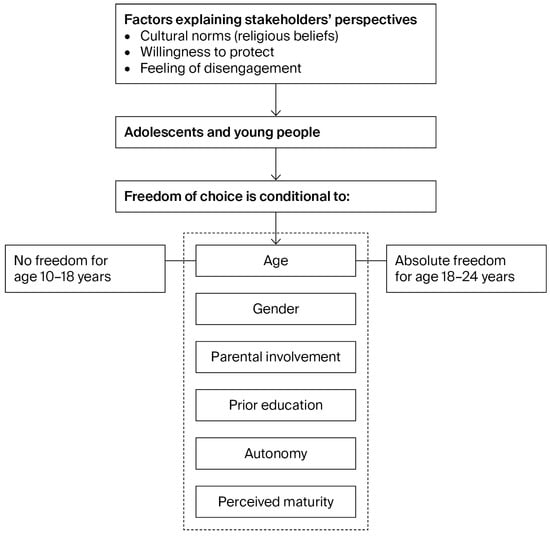

Figure 1 depicts the key dimensions shaping stakeholders’ perspectives of adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice regarding SRHRs, highlighting the distinct forms this freedom may take. First, age emerged as a central determinant, with a clear distinction made between those aged 18 and over and those under 18. Other conditions influencing their freedom included the child’s gender, prior education, parental involvement, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Some stakeholders, however, believed that no conditions should restrict young people’s freedom of choice. Second, the analysis also highlighted contrasting views: some participants expressed reasons why adolescents and young adults do not have freedom of choice, while others justified why they do (See Figure 1). Finally, the data revealed strategies used by parents to guide their children’s SRH decisions.

Figure 1.

Stakeholders’ views on adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom in sexual and reproductive health and rights. We identified three distinct forms of freedom of choice in relation to SRHR: conditional freedom, absence of freedom, and absolute freedom. The degree of freedom is influenced by factors such as the child’s age and gender, parental involvement, prior education, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Younger adolescents (ages 10–18) typically have less freedom. They are often seen as immature and lacking autonomy. In contrast, absolute freedom is more commonly associated with young adults (ages 18–24), who are perceived as mature and autonomous. Stakeholders’ perspectives on this type of freedom are shaped by cultural norms (including religious beliefs), a protective stance, and a sense of disengagement from youth concerns and decision-making.

3.2.1. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Age as a Determinant of Freedom

The study participants’ perceptions around freedom of choice in SRH for adolescents and young adults vary. Age appears to be the main factor determining adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice concerning their SRH. For some stakeholders, age is the condition that determines whether the young person has absolute freedom or an absence of freedom.

Absolute Freedom for Ages 18 and over

Some teachers, one community leader, and a few fathers from the parent sample believe that adolescents and young adults are free to make their own choices about SRH.

“Indeed, given the fact that in Côte d’Ivoire today, children of the age group you’ve just mentioned are already in school and being taught about contraceptive methods, we believe that this is a reality, so we have to give them the freedom to make their choice; otherwise, it will be an infringement of their rights.”High school teacher, participant #19.

This opinion was nuanced by most mothers, who stated that absolute freedom of choice only made sense for young adults aged 18 to 24, adding that not giving them this choice is violating their rights. In addition, from the point of view of some community leaders and teachers, from the age of 18–24, adolescents and young adults can freely make their choice without an intermediary. This opinion is also shared by one father, who thinks that children should have this free choice from puberty onwards, or as soon as they are old enough to get married.

“… Before the age of 18, they are not yet mature enough to talk about sexuality, so parental control is necessary. After the age of 18, they can make their own choices without interference.”University professor, participant #1.

Absolute freedom of choice also applies to the choice of partner for certain stakeholders. For the choice of partner or the choice of having a partner, teachers and fathers believe that everyone should be free to choose their own partner, as forced marriage is not an acceptable practice. Parents should not oppose their children’s choice of partner. A young person over 18 is free to have any partner they choose. One father also points out that, contrary to what is expected, there are certain parents who encourage/pressure their daughters to find a partner.

No Freedom for Adolescents and Young Adults Under 18

A lack of freedom is associated with younger age (mostly young adolescence). Some teachers believe that adolescents and those between the ages of 10 and 18 should not be free to make their own choices about their SRH. The same applies to community leaders, who said that it does not make sense for children to be free to make their own choices when it comes to SRH. As pointed out by one individual, 10 years old is too young to choose. Two fathers were adamant that 10-year-olds are not free to make their own choices and should not even be involved in such matters. As stated by a mother: “A 10-year-old can’t decide anything”. Another mother says she does not support teenagers’ freedom in this respect. In this context, several mothers believe that it is the parent, or the mother specifically, who must decide or make choices for their adolescents in matters of sexual health.

“That’s what I always say, the girl if she’s 14, her parents can decide for her but when she’s 24, she’s a woman and decides for herself.”Parent—mother, participant #54.

When it comes to the choice of abstinence or having sexual relations, some community leaders and parents believe that sexuality must have a well-defined framework. Sexuality concerns married people. Adolescents and young adults must remain abstinent until marriage. Once married, they can take certain liberties. They think adolescents are too young to talk about sex and to start having sex. According to their perception, it is not normal for children to have sex. They must be abstinent until they reach the appropriate age. One mother said that a 10-year-old cannot have sex.

“I think that from the age of 10 to 18, they’re not allowed to talk about sex. At least if you say from 18 to 24, they’re a bit mature on their own and can make their own choices. From 10 to 18, frankly, I don’t agree with that.”Parent—mother, participant #43.

This lack of freedom also applies to the choice regarding consulting a health service, as parents believe they should accompany their children to the health centers—firstly to be present at their side, and secondly to prevent their children from withholding information from them.

“No, she [talking about the teenage girl or young woman] needs to be accompanied, because right now it’s very dangerous. If she makes a choice like that, it’s as if she’s free. No, she must be accompanied. You have to accompany her, or a parent to accompany her is better.”Parent—mother, participant #51.

3.2.2. Other Conditions Pertaining to Freedom

In addition to age, stakeholders grant conditional freedom of choice to adolescents and young adults. Thus, freedom of choice is also conditional on the child’s gender, parental involvement, education, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Conditional freedom of choice also applies to the choice of partner for certain stakeholders.

Gender

Gender norms strongly influence how stakeholders treat adolescents in relation to their freedom of choice in SRH. Many direct their concerns primarily toward girls, imposing stricter supervision. One community leader stated

“No, I can’t accept that [referring to the freedom to date a man while living under his roof]. If I accept that, it means I’ve spoiled my daughter. I can’t accept. She’s at my house, she can’t go out, no, I can’t let her go out.”Community leader, participant #11.

Prior Education and Parental Involvement

Some teachers believe that adolescents and young adults are free to make their choice as long as they are sensitized and educated.

Community leaders, teachers, and mothers highlight the need for the involvement of parents with respect to freedom of choice in general and the choice of their children’s partner. They say adolescents and young adults are free, but there is always a BUT! For instance, community leaders recognize that it is not up to parents to choose their child’s partner, but they believe children should receive advice from their parents regarding their choice of partner. Two fathers expressed that adolescents need parental support and should communicate with their parents and involve them in their choices. This also reflects the position of the mothers. One community leader stated that young girls need their mother’s advice. This perspective was further expanded on by a mother, who explained.

“…it’s your mother who has to accompany you, even to choose, because in any case you have to confide in your mother, even if you love someone, you have to [take him to see your parents]. It’s the old people who know who’s good and who’s not. When you [the parent] talk to the person [the partner], you will find out if he wants to get serious with your child or not. Mothers know. You don’t just get up and throw yourself at him, and say that’s who I want. You can choose him, but you have to talk to the parents. The parents will talk to him and that’s it.”Parent—mother, participant #60.

Parental involvement also applies to the choice of partner. One teacher goes further, stating that free choice is too much, because parents must help a child choose their partner. Another said that parents must approve the chosen partner; otherwise, traditional marriage cannot take place. Moreover, this also applies to the choice of partner for those under 18. According to two mothers, from the age of 15 to 16, children can decide to have a partner. As one mother puts it, “From 16 onwards, my daughter can have a boyfriend, but the boy has to come to the house, because even if you refuse, they’ll do it outside.” In other words, parents’ opposition to adolescent girls having boyfriends can encourage them to be secretive.

“Well… leaving them free to make their choices is a bit of libertarianism. I think that… from the age of 10 to 18, the child can’t choose his or her partner. The child can’t afford to go out at any time without parental consent. But over 18s, as they are said to have come of age, they [the teenagers or young adults] can come home with their partner to introduce them to the family, so that the parents can help them to see if the partner is alright [if the partner is recommendable].”Primary school teacher, participant #20.

Conditional freedom also applies to the choice to use healthcare services. Some community leaders believe that young adults need their parents’ permission to visit a health center.

Autonomy

According to parents, autonomy is another condition for adolescents’ freedom of choice when it comes to SRH. Parents think that adolescents cannot make decisions on their own, as they fall under their responsibility. As one father said, “Whoever has the means/money can make his/her decision”. Thus, adolescents and young adults can decide for themselves when they become independent.

Perceived Maturity

Due to perceived maturity, parents grant a certain type of conditional freedom to adolescents and young adults. Indeed, parents (both fathers and mothers) believe that freedom of choice in this context is conditional and depends on the child’s level of maturity. As they explained, some children are intelligent and mindful of their health, others act independently without seeking guidance, and some struggle to manage their impulses or make informed decisions. Some young people are considered capable of making their own choices, whereas others are viewed as requiring parental advice and supervision.

“It all depends on the child. There are intelligent children, but there are also children who do what they want. Intelligent children know that when there’s health, it’s for themselves. There are also children who don’t listen to anyone; they do what they want.”Parent—father, participant #33.

No Condition

Few teachers expressed progressive views that contrast with those of mothers and community leaders. They emphasized that adolescents should not wait until the age of majority to seek information or consult health services. In their view, young people should be encouraged to visit dedicated health centers at an early age to receive guidance and make informed decisions about their sexuality. Teachers also advocated for adolescents’ freedom to consult health professionals about the risks associated with engaging in sex.

“…It’s true, we say that teenagers, meaning young people, aren’t adults, but nowadays we also talk about sexuality, and whether you like it or not, young people are going to explore it, so they have to make the choice automatically. You [talking about the adolescent or young adult] go to a health center, you approach people who will advise you better, even if you’re 14, even if you’re 13, they’ll tell you: Oh, sweetheart, you have to do this, you have to do that, it’s normal. Even if you’re a teenager, you shouldn’t wait until you’re 18.”Secondary school teacher, focus group #5, participant #2.

3.2.3. Reasons Why Stakeholders Believe Youth Lack SRHRs Freedom

There are many reasons why stakeholders believe that adolescents and young adults aged between 10 and 18 do not have freedom of choice when it comes to their SRH. In the view of these stakeholders, this freedom is synonymous with giving children an neglectful or permissive upbringing, encouraging promiscuity and disengagement from their children’s lives (See Figure 1). At this age, individuals are immature and do not realize the consequences of their actions. They risk making bad decisions that affect them later in life. They also run the risk of being abused. This can lead to unwanted pregnancies.

Additionally, at this age, young people are still under parental control and dependent upon their parents. For other stakeholders, adolescents should not talk about sex or be interested in sexual relationships; the choice they must make is abstinence. They must be advised, guided, and supervised by their parents, who must make decisions for them. Their sexuality must, therefore, be controlled by their parents. Some stakeholders believe that children should be forbidden to have sex until they are mature.

Finally, stakeholders also pointed out that the cultural and religious context imposes certain attitudes on adolescents and young adults. For example, in Islam, young adults are expected to abstain from sex before marriage.

3.2.4. Reasons Why Stakeholders Believe Youth Have SRHRs Freedom

Because they recognize the rights of adolescents and young adults, as well as the importance of health, some stakeholders believe that young people should have freedom of choice regarding their SRH. Other justifications include the fact that the choice is a personal one and that young adults make choices for their own benefit. For this reason, they need to take their choices seriously. Free choice enables them to take charge of their own lives. They can inform themselves through the media and find all kinds of information on sexuality, which allows them to make their own choices. Free choice enables them to go to health centers for information, to opt for a contraceptive method to avoid unwanted pregnancies, and to choose a partner that suits them.

“… you can’t force a child to do something because today… all children have access to the media, so the child is exposed to all kinds of sexual teaching; so, it’s preferable to educate the child and allow him/her, give him/her the freedom, to choose what he should do but at the same time encourage him/her to really follow what can be, will be good for his/her future. There you go. You can’t force something on a child…; the child has the full right to choose his/her sexual education…”Secondary school teacher, focus group #3, participant #3.

3.2.5. Parental Strategies to Limit Adolescents’ Exercise of SRHRs

Parents use a few different strategies to prevent their children from exercising autonomy in SRH-related matters. Firstly, and most importantly, all stakeholders agree that parents need to talk to their children; they should advise them, educate them, raise their awareness of various issues, and encourage them to learn about family planning. Many of parents insist on educating girls.

Some parents advise their children to abstain for religious reasons—in their opinion, abstinence will enable them to concentrate on their studies, extend their education, and avoid sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies. Some parents closely supervise their children to prevent them from engaging in inappropriate behavior. This can take the form of controlling outings and dating, imposing curfews, etc. Other parents may even force their preferences upon their adolescents and young children.

“At a certain age, children do what they want, and it’s us parents who must guide and support our daughters to avoid unintended pregnancies. We have to watch over them to make sure they don’t engage in risky or inappropriate behaviours… Otherwise in my house it’s abstinence or nothing before marriage.”Parent—father, participant #47.

4. Discussion and Interpretation

In this study, we explored the perspectives of stakeholders regarding adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice of with regard to SRHRs in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire. We found that there were many conditions affecting the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults. These conditions shape the extent of freedom granted to them, which is often conditional on age, parental involvement, prior education, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Stakeholders’ perspectives are shaped by cultural norms (religious beliefs), the desire to protect children, and feelings of disengagement. These results lead us to make the following observations.

First, our findings reveal a lack of consistency among stakeholders in how they conceptualize adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice in matters of SHRHs. They largely equate maturity with chronological age, often referencing the legal threshold of 18 years as the point at which adolescents are deemed capable of autonomous decision-making regarding SRH. This perception overlooks the multidimensional nature of maturity, which encompasses emotional, intellectual, moral, social, and biological factors and evolves gradually, so cannot be based on age alone [43]. In many communities, adolescence is not recognized as a distinct life stage; transitions are viewed as binary, from childhood directly to adulthood. As a result, adolescents are often perceived as “sometimes children, sometimes adults”, a fluid categorization that complicates recognition of their capacity to consent in sexual relationships and health decisions [44]. While the results of this study suggest that stakeholders believe that a 10-year-old may not be able to make independent decisions, it is important to acknowledge that the decision-making capacity of adolescents evolves over time. Regardless of age, young people can actively participate in choices related to their SRH when given appropriate guidance and information [45]. These findings echo broader patterns observed in West Africa and other regions, where caregivers and professionals struggle to reconcile legal age with developmental capacity. International guidance emphasizes the importance of assessing adolescents’ evolving capacity rather than relying solely on age-based thresholds [6,46]. Recognizing and supporting this progression is essential to promoting autonomy and ensuring rights-based, age-appropriate interventions.

Second, we found that for most stakeholders, there is always a “BUT” to adolescents’ and young adults’ freedom of choice with regard to SRHRs. While the stakeholders asserted the need for parental input, the limit of this input remains unclear. A priori, it may appear that adolescents and young adults simply inform their parents and receive advice in return, without any formal conditions attached. In that sense, parental input may not be perceived as a strict requirement. However, teachers’ responses suggest that this input can carry significant weight, to the extent that, if their opinion is not considered, it could potentially prevent certain decisions or actions by the adolescent or young adult, such as getting married to the partner of their choice. This is especially true in many African contexts, where parental blessing is often necessary for marriage and other life choices [47]. These findings challenge the notion of absolute freedom for individuals over 18 years old regarding SRHRs. In reality, the freedom of choice granted to adolescents and young adults must be understood within broader trajectories of autonomy that are not strictly tied to legal age. In many African societies, autonomy is acquired progressively and contextually, shaped by cultural, economic, and social factors [48]. Young people often remain in the family home, not due to a lack of ambition but because of social norms that value intergenerational cohabitation and collective well-being [48]. As such, the freedom to make decisions about SRH is embedded in evolving social roles and expectations, rather than based on a fixed legal threshold. This perspective invites a reassessment of how autonomy and rights are conceptualized and exercised in culturally embedded ways. Interventions with stakeholders should focus on their knowledge, buy-in, and awareness of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights, in order to create an enabling environment for young people to lead fulfilling sexual and reproductive lives.

Third, this study highlights several underlying factors the shape stakeholders’ perspectives on adolescents’ and young adults’ SRHRs, including deeply rooted influences such as religious and gender norms. Numerous studies have demonstrated that gender norms shape stakeholders’ perceptions of adolescents’ SRHRs in ways that disproportionately disadvantage girls. While all youth are affected, girls face stricter expectations around sexuality, mobility, and reputation, which limit their autonomy and access to services. These norms are among the most significant barriers to SRHRs education and uptake for adolescent females [49,50,51]. To foster meaningful change, it is essential to move beyond descriptive acknowledgment of these norms and toward a deeper understanding of how they intersect with other factors. For instance, many parents struggle to communicate SRHRs information to their children due to their own lack of exposure to such education, whether at home or in school [52]. Evidence from effective interventions [53] suggests that inclusive, community-based strategies, such as integrating local role models, fostering intergenerational dialog, and engaging community and religious leaders, can help shift attitudes. These approaches must be tailored to local sociocultural realities and grounded in culturally sensitive advocacy to empower adolescents to exercise their rights within supportive environments.

This study has several limitations. First, we considered both the SRHRs of adolescents and young adults, our study therefore encompasses a broad age range. This led some participants to focus on age group that resonated most with their views. Second, a small number of participants had poor literacy skills, which may have affected the clarity of certain responses. We addressed this with support from our Ivorian analyst. Third, our study did not fully explore stakeholders’ socio-demographic factors; these factors may have explained their different perspectives. However, the inclusion of multiple generations allowed cross-generational insights. Finally, the study does not include adolescents’ and young adults’ opinions, which limits our understanding of how they perceive autonomy and freedom of choice regarding SRHRs. Future research should center on their perspectives to ensure that any interventions reflect their lived experiences and evolving capacities.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the perspectives of stakeholders pertaining to the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults regarding SRHRs in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire. The results revealed that this freedom is shaped by multiple conditions that influence the degree of autonomy granted. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to strengthen stakeholders’ knowledge and awareness of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights. More broadly, they call for policy frameworks that recognize adolescents’ evolving decision-making capacity, for community-based efforts that support informed choice, and for context-sensitive approaches that reflect local understandings of adolescence and autonomy.

Author Contributions

Funding acquisition, conceptualization, and methodology: A.A., J.R., S.D., and M.J.D.; Data curation: M.K., and S.D.; Formal analysis: T.T.A., M.M.N., L.G.K., and M.J.D.; Writing—original draft: T.T.A., and M.J.D.; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The PASSAGE project is funded by Global Affairs Canada under approval number P-010344.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by the Comité National d’Éthique des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé in Côte d’Ivoire (N/Réf: 114–23/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km) on 3 July 2023, and by the Research Ethics Committee of the CHU de Québec-Université Laval in Canada (Project 2024–7017), on 8 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all partners, in particular the field team in the Ivory Coast, the interviewers and transcribers, for their contribution to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Global Affairs Canada. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SRH | Sexual and reproductive health |

| SRHRs | Sexual and reproductive health rights |

| ASRHRs | Adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights |

| PASSAGE | Projet d’Appui à des Services de Santé Adaptés au Genre et Équitables |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). Including the Human Reproduction Special Programme (HRP). Defining Sexual Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual Health and Its Linkages To Reproductive Health: An Operational Approach. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924151288 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. Health Sector National Guidelines. 2013. Available online: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/guideline/swz-ad-17-01-guideline-2013-eng-adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive-health---health-sector-na.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Evans, R.; Diop, R.A.; Kébé, F. Familial roles, responsibilities, and solidarity in diverse African societies. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Africa; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanmuoh, E.E.; Dibua, E.C.; Friday, E.C. Implication of extended family culture in African nations on youth development: Evidence from Nigeria. Int. J. Public Adm. Manag. Res. 2024, 10, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Recommendations on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514606 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Silva, S.; Romão, J.; Ferreira, C.B.; Figueiredo, P.; Ramião, E.; Barroso, R. Sources and types of sexual information used by adolescents: A systematic literature review. Healthcare 2014, 12, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleton, P.; Meherali, S.; Memon, Z.; Lassi, Z.S. Understanding the contents and gaps in sexual and reproductive health toolkits designed for adolescence and young adults: A scoping review. Sex. Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, B.A.; Wilkinson, T.A.; Maslowsky, J. Adolescent-Centered Sexual and Reproductive Health Communication. JAMA 2025, 333, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population Development. 20th Anniversary Edition. 2014. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/programme_of_action_Web%20ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Liang, M.; Simelane, S.; Fillo, G.F.; Chalasani, S.; Weny, K.; Canelos, P.S.; Jenkins, L.; Moller, A.-B.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Say, L. The state of adolescent sexual and reproductive health. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowshin, N.; Kapiriri, L.; Davison, C.M.; Harms, S.; Kwagala, B.; Mutabazi, M.G.; Niec, A. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of “last mile” adolescents: A scoping review. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters. 2022, 30, 2077283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Young People Today, Time to Act Now: Why Adolescents and Young People Need Comprehensive Sexuality Education and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Eastern and Southern Africa; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000223447_fre (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Melesse, D.Y.; Mutua, M.K.; Choudhury, A.; Wado, Y.D.; Faye, C.M.; Neal, S.; Boerma, T. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Sub-Saharan Africa: Who is left behind? BMJ. Glob. Health. 2020, 5, e002231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denya, T.S. Teen Pregnancy Hinders Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2024. Available online: https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/186346/teen-pregnancy-in-sub-saharan-africa (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme (CNDH). Rapport Annuel CNDH 2023. 2023. p. 67. Available online: https://cndh.ci/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/RAP-ANNUEL-2023-CNDH.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme (CNDH). Communiqué de Presse Numéro 3. 2024. Available online: https://cndh.ci/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/COMMUNIQUE-DE-PRESSE-N%C2%B003.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Ministère de l’éducation nationale et de l’alphabétisation. Statistiques scolaires de poche, Rapport 2023–2024. MENA/DESPS. Direction des stratégies, de la planification et des statistiques. 2024. Available online: https://mena-desps.org/static/docs/statistics/poche/poche_20232024.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Tisseron, C.; Djaha, J.; Dahourou, D.L.; Kouadio, K.; Nindjin, P.; N’gbeche, M.-S.; Moh, C.; Eboua, F.; Bouah, B.; Kanga, E. Exploring the sexual and reproductive health knowledge, practices and needs of adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV in Côte d’Ivoire: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Côte d’Ivoire. Les Adolescent(e)s et les Jeunes—Analyse de la Situation des Enfants et des Femmes en Côte d’Ivoire. 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/cotedivoire/media/3106/file/Les%20adolescent%28e%29s%20et%20les%20jeunes.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- AGIR. Improving Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights for Young People and Adolescents in Côte d’Ivoire. Available online: https://solthis.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/AGIR-EN.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Ministère de la Santé et de l’Hygiène Publique (MSHP). Politique Nationale de la Santé Sexuelle, Reproductive et Infantile, Côte d’Ivoire. 2020. Available online: https://natlex.ilo.org/dyn/natlex2/natlex2/files/download/111964/CIV-111964.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- N’Dri, M.K.; Konan, E.Y.; Guede, C.M.; Dagnan, S.; Yaya, I. Trends and determinants of risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults in Côte d’Ivoire from 1998 to 2021. Int. J. Epidemiol. Health Sci. 2025, 6, e725382. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Fischer, F. Perceptions of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights: A cross-sectional study in Lahore District, Pakistan. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.F. Human rights and reproductive health: Political realities and pragmatic choices for married adolescent women living in urban slums, Bangladesh. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2011, 11, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remez, L.; Woog, V.; Mhloyi, M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of Adolescents in Zimbabwe. Guttmacher Institute. Series, No. 3. 2014. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/sexual-and-reproductive-health-needs-adolescents-zimbabwe (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Wahyuningsih, S.; Widati, S.; Praveena, S.M.; Azkiya, M.W. Unveiling barriers to reproductive health awareness among rural adolescents: A systematic review. Front. Reprod. Health 2024, 6, 1444111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.J.T.P.; Bijlmakers, L. Autonomy and freedom of choice: A mixed methods analysis of the endorsement of SRHR and its core principles by global agencies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan International France. Causes et Conséquences du Manque D’accès à la Santé Sexuelle et Reproductive. n.d. Available online: https://www.plan-international.fr/nos-combats/sante-sexuelle-et-reproductive/causes-et-consequences-du-manque-dacces-a-la-sante-sexuelle-et-reproductive/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Share-Net International. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Adolescents and Youth: A Narrative Review of Challenges and Opportunities for Achieving SRHR Goals. 2020–2021. Available online: https://share-netinternational.org/archive-v1/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SNI_Narrative-Review_SRHR-for-Adolescents-and-Youth-final.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Denno, D.M.; Hoopes, A.J.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S22–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Svanemyr, J.; Amin, A.; Fogstad, H.; Say, L.; Girard, F.; Temmerman, M. Twenty years after International Conference on Population and Development: Where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE/CSAO. L’économie Locale du Département de Daloa—Synthèse, Écoloc, Gérer L’économie Localement en Afrique: Évaluation et Prospective; Éditions OCDE: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhoff, T. Daloa, Department in Ivory Coast. 2022. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/ivorycoast/admin/haut_sassandra/1011__daloa/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Morris, J.L.; Rushwan, H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 131, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Adolescent and Youth Demographics: A Brief Overview. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/resources/adolescent-and-youth-demographicsa-brief-overview (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Mueller, R.; Germain, A.; Fredrick, B.; Bourne, K. Towards a sexual ethics of rights and responsibilities. Reprod. Health Matters 2009, 17, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 2001, 24, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerke, V.I. Scientific discourse on the categories of “maturity” and “psychological maturity” of personality. Educ. Pedagog. J. 2023, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blibolo, A.D. Cibler les Adolescent·e·s Dans les Politiques Publiques en Matière de Santé Sexuelle et Reproductive et de Lutte Contre les Violences Basées sur le Genre en Côte d’Ivoire. Centre de Recherches Pour le Développement International (CRDI). 2021. Available online: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7da349bb-0517-4650-910f-692cb6609bbe/content (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Assessing and Supporting Adolescents’ Capacity for Autonomous Decision-Making in Health Care Settings: A Tool for Health-Care Providers. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039568 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Plan International. SRHR in Adolescence: Insights from the Real Choices, Real Lives Cohort Study. 2022. Available online: https://plan-international.org/publications/srhr-in-adolescence/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Marcoux, R.; Antoine, P. Le Mariage en Afrique: Pluralité des Formes et des Modèles Matrimoniaux; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://www.odsef.fss.ulaval.ca/sites/odsef.fss.ulaval.ca/files/le_mariage_en_afrique-puq-euro-2014.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Gastineau, B.; Golaz, V. Being young in rural Africa. Afr. Contemp. 2016, 259, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ouahid, H.; Sebbani, M.; Cherkaoui, M.; Amine, M.; Adarmouch, L. The influence of gender norms on women’s sexual and reproductive health outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolundzija, A.; Marcus, R. Annotated Bibliography: Gender Norms and Youth-Friendly Sexual and Reproductive Health Services; ALIGN: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.alignplatform.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/align_annotated_bibliography.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Okeke, C.C.; Mbachu, C.O.; Agu, I.C.; Ezenwaka, U.; Arize, I.; Agu, C.; Obayi, C.; Onwujekwe, O. Stakeholders’ perceptions of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health needs in Southeast Nigeria: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindin, M.J.; Fatusi, A.O. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2009, 35, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Wright, B.; Smith, L.; Roberts, S.; Russell, N. Gendered stereotypes and norms: A systematic review of interventions designed to shift attitudes and behaviour. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).